Abstract

Over the last 2 decades, novel therapies targeting several immune pathways have been developed for the treatment of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Although anti–tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) agents remain the firstline treatment for moderate to severe Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, many patients will require alternative agents, due to nonresponse, loss of response, or intolerance of anti-TNFs. Furthermore, patients may request newer therapies due to improved safety profiles or improved administration (ie, less frequent injection, oral therapy). This review will focus on new and emerging therapies for the treatment of IBD, with a special focus on their adverse effects. Although many of the agents included in this paper have been approved for use in IBD, a few are still in development but have been shown to be effective in phase II clinical trials.

Keywords: inflammatory bowel disease, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, biological therapy, stem cells, safety

INTRODUCTION

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs) are chronic conditions that primarily affect the gastrointestinal tract and result in significant morbidity and health care expenditure.1 Inflammatory bowel disease is comprised of Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), and because of its progressive natural history, management is complex, multidisciplinary, and often life-long. The last 2 decades have seen many advances in the therapeutic landscape for IBD, with mainstream use of anti–tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) agents for treatment arguably being the most notable. Anti-TNFs have become the cornerstone of treatment for moderate to severe UC and CD, resulting in improved health outcomes and a decreased need for surgical intervention.2, 3 Additionally, anti-TNFs have also been shown to be efficacious in treating the perianal and extra-intestinal manifestations of IBD.4, 5 However, treatment failure is seen in a significant proportion of patients treated with anti-TNFs. Approximately 30% of patients will not respond to initial treatment (primary nonresponders), and 40% of those who initially respond will lose response at some point in the disease course (secondary nonresponders).6, 7 Additionally, the utility of anti-TNFs is tempered by the risk of uncommon and rare but serious adverse effects. Anti-TNFs are associated with an increased risk of serious infection, paradoxical autoimmune reactions, and a small but increased risk of malignancy.8–11

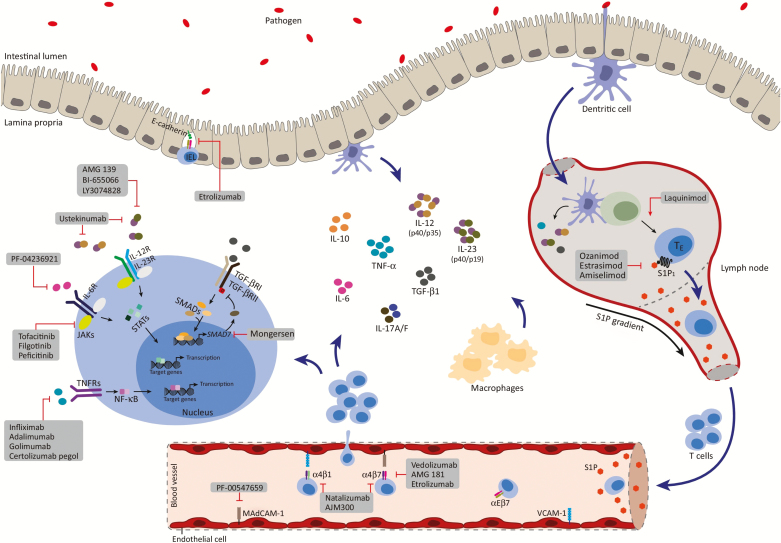

In the current landscape, there is a need for additional safe and effective therapeutic options to address unmet treatment needs in patients with IBD. Multiple new drugs with mechanistic effects at different points in the pathophysiology of IBD have been developed to meet this need, and 1 older agent has reemerged in the treatment space for this purpose (Fig. 1). This article will review the emerging and existing medications of therapeutic relevance in the treatment of IBD. In this paper, we will discuss the characteristics and efficacy of these agents and, in particular, examine their safety profile (Table 1).

FIGURE 1.

Novel therapy targets in the treatment of IBD.

Reprinted from Trends in Pharmacological Sciences, Volume 38 (2), Mehmet Coskun, Severine Vermeire, Ole Haagen Nielsen, Novel Targeted Therapies for Inflammatory Bowel Disease, Pages 127–142, 2017, with permission from Elsevier.

TABLE 1.

SUMMARY OF FREQUENCY OF ADVERSE EVENTS OF IBD THERAPIES IN COMPARISON WITH PLACEBO

| Drug | Route | Mechanism of Action | Serious Infection | Malignancy | Neurologic Reactions | Immunogenicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-adhesion agents | ||||||

| Natalizumab | IV | α4β7 and α4β1 integrin inhibitor | + | - | + | + |

| Vedolizumab | IV | α4β7 integrin inhibitor | + | - | - | + |

| Ertolizumab | SC | α4β7 and αEβ7 integrin inhibitor | - | - | + | a |

| AJM 300 | PO | α4β7 and α4β1 integrin inhibitor | - | - | - | a |

| PF-00547659 | SC | MAdCAM-1 inhibitor | - | - | + | + |

| Anti-interleukin inhibitors | ||||||

| Ustekinumab | IV, SC | IL12/23 inhibitor | + | - | - | + |

| Risankizumab | IV | IL12 inhibitor | - | - | - | + |

| JAK/STAT inhibitors | ||||||

| Tofacitinib | PO | JAK1/3 inhibitor | + | + | - | NI |

| Filgotinib | PO | JAK1 inhibitor | + | - | - | NI |

| S1P receptor modulator | ||||||

| Ozanimod | PO | S1P1/5 inhibitor | - | - | - | NI |

| Stem cell therapy | SC | Adipose-derived stem cells | + | - | - | a |

+ increased; - decreased.

Abbreviations: NI, not immunogenic; PO, per oral; SC, subcutaneous.

aNot reported in clinical studies.

METHODS

In addition to medications that have been approved for use in IBD, we included agents in development that have shown promise in phase II and III clinical trials. The immune pathways of the agents that have been included in this review include anti-adhesion agents, anti-interleukin inhibitors, Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK/STAT) inhibitors, sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor modulator, and stem cell therapy for perianal disease. On review of the safety profile of specific therapies, only the most frequent and clinically relevant adverse events are highlighted, and comparisons are made between the treatment and placebo groups. Adverse events were considered “common” if they were present in at least 5% to 10% of any study group, depending on the trial. Some serious and rare adverse events have been included in this review because of their influence on clinical practice, especially in regards to screening and prevention practices.

ANTI-ADHESION AGENTS

The pathogenesis of chronic inflammation in the intestinal mucosa is characterized by a multistep process that leads to the migration of lymphocytes from the blood stream into the gut mucosa.12 This trafficking of T lymphocytes from lymphoid organs to the site of gut inflammation is mediated by chemokines and selectins and leads to the adhesion of integrins on the surface of T cells to ligands on the cell surface of endothelial cells, and then uptake into the intestinal tissue.13, 14 New pharmacologic agents have been developed for the treatment of IBD that prevent lymphocyte infiltration of the intestines by selectively targeting the adhesion molecules involved in this homing process.

Natalizumab

Natalizumab is the first anti-adhesion agent that was used in CD patients and was initially approved in the United States for the treatment of multiple sclerosis (MS) in 2004.15, 16 It is a recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody approved for the treatment of moderate to severe CD, and it acts by blocking the α4 integrin on lymphocytes.17 Specifically, it blocks the α4β7 and α4β1 integrins on T cells from binding with mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule–1 (MAdCAM-1) and vascular cell adhesion molecule–1 (VCAM-1), respectively, thereby preventing T-cell migration into tissues and mitigating the inflammatory process.18, 19 In comparison with placebo, natalizumab has been shown to be more effective in the induction and maintenance of remission in patients with CD. In the ENCORE trial, natalizumab was compared with placebo in a randomized trial of 509 patients with moderately to severely active CD and elevated C-reactive protein levels.20 Patients received 300 mg of intravenous natalizumab or placebo at weeks 0, 4, and 8, and the primary end point was induction of response at week 8 sustained through week 12. This was significantly higher in the natalizumab group (48% vs 32%; P < 0.001), and sustained remission was also higher in natalizumab-treated patients (26% vs 16%; P = 0.002).

Natalizumab’s use has been drastically limited by its association with the life-threatening central nervous system infection progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML). This severe adverse event is caused by reactivation of the John Cunningham virus (JCV) and is thought to be due to blockade of the adhesion of α4β1 integrins to VCAM-1, leading to a paucity of migration of T cells to provide immunity against viral activity in the central nervous system.21 In a study of natalizumab-treated patients, the incidence of PML was reported to be 2.1 cases per 1000 patients, and nearly one-quarter (22%) of affected patients died.22 Upon stratification of the study population, those with the highest risk of PML had an incidence of 11.1 cases per 1000 patients. Factors associated with an elevated risk of PML included the presence of positive anti-JCV antibodies, prior immunosuppressant therapy, and increased duration of natalizumab treatment. In 2005, natalizumab was withdrawn from the US market because of the high risk of PML.23 However, it was reintroduced for restricted use and was approved in 2008 for use in CD patients who were not on concurrent immunosuppressant therapy and who had not responded to conventional therapy. Available data suggest that the risk of PML would be reduced in patients who do not have anti-JCV antibodies and who are treated for no more than 8 months.24 Minor adverse events have also been reported with the use of natalizumab, and these include infusion reactions, headaches, nausea, and the development of drug antibodies.20

Vedolizumab

Vedolizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody that works by targeting the α4β7 integrin on T cells and prevents it from binding with the ligand MAdCAM-1 on endothelial cells.14 The α4β7 integrin is only present on intestinal T cells, and as such, vedolizumab selectivity prevents lymphocyte infiltration and improves chronic inflammation exclusively in the gut. Because of its gut specificity, vedolizumab does not block the infiltration of immune cells in the central nervous system because it does not interact with the α4β1 integrins. This offers an advantage over natalizumab, as it has not been associated with the occurrence of PML.

Vedolizumab is approved for the treatment of both UC and CD that is refractory to conventional therapy, and it has been shown to be effective in the induction and maintenance of remission in IBD. The GEMINI I, II, and III studies are randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trials that were conducted to assess the efficacy of vedolizumab in inducing and maintaining remission in the following: moderate to severe UC, moderate to severe active CD, and moderate to severe active CD where a majority of patients had failed anti-TNF therapy, respectively.25–27 In GEMINI 1, UC patients who received vedolizumab had significantly higher clinical response rates when compared with placebo at week 6 (47.1% vs 25.5%; P < 0.001). At week 52, clinical remission was higher in those who continued to receive vedolizumab every 4 weeks (44.8%) or 8 weeks (41.8%), in comparison with the placebo (15.9%) group (P < 0.001 for the 2 treatment arms of vedolizumab compared with placebo). In the GEMINI II trial, vedolizumab resulted in better outcomes overall. However, clinical remission rates at 6 weeks were similar in the vedolizumab and placebo groups among the subset of patients who had previously failed anti-TNF therapy (13.3% vs 9.7%; P = 0.157). Subsequently, the primary analysis in the GEMINI III trial included CD patients who had previously failed anti-TNF therapy. The researchers found that only 15.2% of those in the vedolizumab group and 12.1% of those in the placebo group were in remission at week 6 (P = 0.433). A beneficial effect in inducing clinical remission was only observed at week 10 in GEMINI III, suggesting a slower time to full therapeutic efficacy for vedolizumab in patients with CD.

Vedolizumab has an excellent safety profile. The most frequently reported adverse events are minor and include headaches, fever, arthralgias, and nausea.25–27 Nasopharyngitis and upper respiratory tract infections have also been reported. In a post hoc analysis of the safety of vedolizumab in the GEMINI I and II trials, the rates of adverse events were generally comparable across all age groups.28 Serious infections and drug-related adverse events are rare with vedolizumab use, and malignancies have rarely been reported. In a multicenter, retrospective study of 212 patients followed over 160 patient-years by the US Vedolizumab for Health OuTComes in InflammatORY Bowel Diseases (VICTORY) consortium, vedolizumab was found to be well tolerated, and the rate of infusion reactions was low (3.5 per 1000 infusions).29 In an analysis of the safety data on vedolizumab, less than 1% (n = 18) of the 2830 drug-exposed patients across 6 clinical trials were diagnosed with a malignancy over 4811 person-years.30 Additionally, although neurological symptoms have been reported in association with vedolizumab use, there have been no confirmed cases of PML. In the aforementioned study, Colombel et al. estimated that a total of 4232 patients had been exposed to vedolizumab across all clinical studies, with about one-quarter being exposed for longer than 24 months. None of these patients developed PML.30 Screening for anti-JCV antibodies before the initiation of vedolizumab is thus unnecessary, as there have not been any associated cases of PML.

Reports of tuberculosis (TB) have been rare in vedolizumab-exposed patients. In clinical trials, pulmonary TB was reported in 3 patients. They were all from countries with high rates of TB.29 Screening for TB before initiation of vedolizumab is common in many practices in the United States and in other developed countries with a low incidence of TB. However, there are currently no consensus recommendations to guide this practice, and the utility and cost-effectiveness of this TB screening before therapy has not been demonstrated. Notably, a postmarketing case series of >66,390 patient-years of vedolizumab therapy reported TB in 5 patients.31 They were all from low-incidence countries, including the United States. In the absence of robust practice guidelines, we suggest that the clinicians’ decision to screen persons in nonendemic areas should be informed by the patients’ risk profile. Place of birth, travel history, and prior or concurrent immunosuppressant therapy are some variables that may be relevant in individual TB risk stratification in low-incidence practice settings.

Etrolizumab

Etrolizumab is an anti-adhesion agent that has been found to be effective in the induction and maintenance of remission in UC in phase II clinical trials. It is a humanized monoclonal antibody that disrupts leukocyte migration into intestinal tissue by selectively binding to the β7 subunit of the heterodimeric integrins α4β7 and αEβ7, thus preventing their interaction with MAdCAM-1 and E-cadherin, respectively.32, 33 The inhibition of α4β7 integrin prevents lymphocyte migration to the intestinal mucosa, as is seen with vedolizumab.34 However, the additional inhibition of αEβ7 blocks the retention of lymphocytes in the intraepithelial compartment of the intestinal mucosa.35, 36

The efficacy of etrolizumab as an induction treatment was recently evaluated in 124 patients with moderately to severely active UC in a randomized, placebo-controlled, phase II clinical trial.37 Patients were randomized in a 1:1:1 fashion to receive subcutaneous administration of placebo or 100 mg or 300 mg of etrolizumab. At week 10, none of the patients in the placebo group were in clinical remission, but 21% of those in the 100-mg group (P = 0.004) and 10% in the 300-mg group (P = 0.048) had attained remission. Etrolizumab has not yet been approved for the treatment of UC, but multiple large-sized phase III clinical trials are currently underway to investigate its utility in the treatment of moderate to severe UC (ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers: NCT02118584, NCT02100696, NCT02136069, NCT02165215, NCT02171429, NCT02163759) and CD (ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers: NCT02403323, NCT02394028).

Etrolizumab has been shown to have a good safety profile in the available published studies. It is well tolerated, and adverse effects have been reported in a comparable proportion of subjects receiving drug vs placebo in phase I and II studies. Vermeire et al. found a higher rate of arthralgias, influenza-like illness, and rash in the group receiving 100 mg of etrolizumab, which were all of mild to moderate severity.37 There were no serious infections reported in this study, and serious adverse events were rare. A preceding phase I trial also found few serious adverse events.38

AJM300

AJM300 is an orally active, small molecule with a mechanism of action similar to natalizumab. It is an antagonist of the α4 integrin subunit and acts by preventing the binding of α4β7 and α4β1 integrins on T cells to MAdCAM-1 and VCAM-1, respectively. This results in inhibition of the trafficking of lymphocytes into the gut.39 AJM300 has been shown to be more efficacious than placebo in clinical studies. In a double-blind phase IIa study of 102 patients with moderately active UC, AJM300 (960 mg 3 times daily) was shown to result in higher rates of clinical response (62.7% vs 25.5; P = 0.0002), clinical remission (23.5% vs 3.9%; P = 0.0099), and mucosal healing (58.8% vs 29.4%; P = 0.0014) at week 8 compared with placebo.40 No serious adverse events were observed with AJM300 in this study, and the incidence rates of adverse events were comparable between the placebo and active treatment groups. The most common adverse effects reported were nasopharyngitis, exacerbation of UC, and abdominal pain. Like natalizumab, AJM300 can theoretically result in an increased risk of PML as its nonspecific activity against the α4 integrin subunit could lead to a reduction in lymphocyte trafficking to the brain. There have not been any cases of PML reported with the use of AJM300. However, available studies have been small, have been of short duration, and have sometimes included subjects who were screened to ensure a reduced risk of PML. A phase III trial to evaluate the safety and efficacy of AJM300 in active UC is set to begin patient recruitment in 2018 (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03531892).

PF-00547659

PF-00547659 is a monoclonal IgG2 antibody that has activity against the intestinal epithelial adhesion molecule MAdCAM-1, thus preventing leukocyte migration into sites of inflammation in the gut.41, 42 PF-00547659 has been shown to be efficacious and well tolerated in patients with UC in preliminary studies.43, 44 In a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase II clinical trial in 357 patients with moderate to severe UC, those in the active treatment groups received subcutaneous injections of 7.5 mg, 22.5 mg, 75 mg, or 225 mg of PF-00547659 at baseline and every 4 weeks thereafter.43 The primary end point was remission at week 12, which was found to be significantly greater in the 7.5-mg (11.3%; P = 0.04), 22.5-mg (16.7%; P = 0.009), and 75-mg (15.5%; P = 0.01) treatment groups when compared with the placebo group (2.7%). PF-00547659 was found to be well tolerated, and adverse events were comparable between the treatment and placebo groups. Headaches, abdominal pain, and nausea were the most frequently reported adverse events. The most common serious adverse event was exacerbation of UC, which was mostly seen in the 7.5-mg treatment group (n = 6). The occurrence of adverse events did not correlate with dose in the treatment groups. Phase III trials are currently recruiting participants with moderate to severe CD to evaluate the safety profile and efficacy of PF-00547659 (ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers: NCT03559517, NCT03566823).

ANTI-INTERLEUKIN INHIBITORS

Interleukin-12 (IL-12), a heterodimer of p40 and p35, and interleukin-23 (IL-23), a heterodimer of the same p40 and p19, induce differentiation of naïve CD4+ T cells into T-helper 1 and T-helper 17 cells, respectively, and are important in the pathogenesis of IBD. The downstream effects lead to upregulation of inflammatory cytokines and mediation of cellular immunity.45–47

Ustekinumab

Ustekinumab is a fully human IgG1 monoclonal antibody that targets the IL-12/23 shared p40 subunit, blocking the receptors for these pro-inflammatory cytokines on cells.48 It was first approved in 2009 for the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis and was approved in 2016 for the treatment of moderate to severe CD.49

The UNITI-1 trial enrolled 741 patients between 2011 and 2016 with moderate to severe CD who had failed or were intolerant to anti-TNF therapy, whereas UNITI-2 enrolled 628 patients who had either achieved a prior response to anti-TNFs or were naïve to anti-TNF treatment.50 In a randomized fashion, patients in both trials received either a single dose of intravenous ustekinumab (130 mg), a weight-based dose of ustekinumab (approximately 6 mg/kg), or placebo. The primary end point was clinical response at week 6, and in UNITI-1, this was reached by 21.5% of subjects in the placebo arm, 34.3% in the 130-mg arm (P = 0.002 vs placebo), and 33.7% in the weight-based arm (P = 0.003 vs placebo). In UNITI-2, clinical response at week 6 was also significantly higher in both treatment arms in comparison with placebo: 51.7% for the 130-mg arm, 55.5% for the weight-based arm, and 28.7% for the placebo arm (P < 0.001 for both treatment doses compared with placebo). Patients who responded to induction therapy at week 8 in UNITI-1 and UNITI-2 were enrolled in the IM-UNITI maintenance trial and were randomly assigned (n = 397) to receive subcutaneous injections of ustekinumab 90 mg, either every 8 or 12 weeks, or to placebo. Clinical remission was evaluated at week 44, and although this was attained in 35.9% of those receiving placebo, it was observed in 53.1% (P = 0.005) of patients receiving ustekinumab every 8 weeks and in 48.8% (P = 0.04) of those receiving it every 12 weeks.50

In UNITI-1 and UNITI-2, the rates of adverse events (AEs) were not statistically different between the treatment and placebo groups. Common adverse events, present in 5% or more in any study group, included arthralgia, headache, nausea, pyrexia, nasopharyngitis, abdominal pain, CD event, and fatigue. Serious adverse events (SAEs) occurred in 4.7%, 7.2%, and 6.1% of patients receiving ustekinumab 130 mg, weight-based dosing, and placebo, respectively, in UNITI-1. In UNITI-2 and IM-UNITI, the rates of SAEs were comparable in the treatment and placebo groups. Similarly, serious infections occurred at a similar rate in the treatment and placebo groups in the UNITI-1, UNITI-2, and IM-UNITI trials. One case of active pulmonary tuberculosis occurred 10 months after the patient received a single dose of ustekinumab 130 mg. Five patients across all 3 trials developed nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC); 2 patients had received placebo, and 3 received ustekinumab. No deaths or cases of reversible posterior leukoencephalopahy syndrome developed during 1 year of therapy.50 No relationship between the dose of ustekinumab and its safety has been demonstrated, and there is also no cumulative dose effect.50–52 Of the CD patients who developed nonmelanoma skin cancer during the study period, 3 of the 5 patients were currently using or had been on immunosuppressants in the past. In an analysis of >12,000 patients followed for a median of 4.17 years in the Psoriasis Longitudinal Assessment and Registry (PSOLAR), there was no association between ustekinumab use and the development of malignancy.53 Although there is a theoretically increased risk of certain types of infection, including Salmonella, non-TB Mycobacterium, and TB Mycobacterium, as patients with inherited defects in IL-12 and IL-23 demonstrate, this was not borne out in either short-term or long-term studies of ustekinumab.50–52, 54, 55 Phase III studies of ustekinumab in UC are ongoing, and results are anticipated in 2021 (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02407236).

Risankizumab

Risankizumab is a humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody that selectively binds with high affinity to the IL-23 p19 subunit, and it is currently being studied for use in patients with IBD. By specifically targeting the IL-23-mediated inflammatory pathway without disrupting the IL-12-dependent T-cell pathway, which is thought to be important for infection and cancer immunity, risankizumab theoretically may confer fewer side effects in comparison with ustekinumab.56 The results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase II study that took place between 2014 and 2016 in patients with moderate to severe CD who were treated with risankizumab was recently published.57 In this study, 121 patients were randomized in a 1:1:1 fashion to receive risankizumab 200 mg, risankizumab 600 mg, or placebo by intravenous infusion at 0, 4, and 8 weeks; the majority of patients had previously used an anti-TNF agent. They were followed through week 12, with a primary end point of clinical remission defined as a CD Activity Index score <150. The differences between the risankizumab 200-mg and 600-mg arms vs the placebo arm were 9.0% (P = 0.31) and 20.9% (P = 0.025), respectively. Those receiving risankizumab 600 mg also attained significantly higher rates of clinical response, endoscopic remission, endoscopic response, and deep remission. C-reactive protein (CRP) was also significantly decreased in both risankizumab arms compared with placebo.

Risankizumab was well tolerated, and the most common AEs, reported in at least 10% of any study group, included nausea, worsening CD, abdominal pain, arthralgia, anemia, headache, and vomiting. The rates of AEs were not different among the 3 treatment groups and did not appear to be dose related.57 The use of risankizumab led to serious adverse events in the 12 patients treated with either 200 mg or 600 mg of risankizumab compared with the 12 patients in the placebo arm. There were no deaths in this trial. Serious infections were observed, including pneumonia in 1 patient in the 200-mg arm and osteomyelitis and anal abscess in 2 patients in the 600-mg arm. Three patients in the placebo arm experienced serious infection (abdominal, anal, and rectal abscesses and pneumonia). Ten patients in the placebo arm had an adverse event requiring hospitalization, compared with 10 patients in the risankizumab arms combined.57 Although the safety profile of risankizumab seems favorable in IBD, available studies are limited by their small sample size and short-term nature. Phase III studies of risankizumab, which may elucidate a more comprehensive safety profile, are currently ongoing (ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers: NCT03398135, NCT03105128).

JAK/STAT INHIBITORS

In the pathogenesis of IBD, cytokines play a crucial role in the multistep process that ultimately results in the activation and potentiation of inflammation. Cytokines mediate intracellular signaling by inducing the JAK/STAT signaling pathway.58 JAKs are a family of intracellular tyrosine protein kinases comprised of 4 members—JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, and tyrosine kinase 2 (TYK2).59 Cytokines bind to specific receptors on JAK proteins, which in turn leads to the phosphorylation and migration of dimerized STAT factors into the cell nucleus, resulting in gene transcription.60 Several pro-inflammatory cytokines act as ligands on the cytokine receptors of JAKs and, through several pathways, lead to the inflammatory process that is characteristic of IBD. Inhibition of the JAK/STAT signaling pathway is a major area of interest in the development of novel IBD therapies and has also been explored for other inflammatory conditions.61 Tofacitinib and filgotinib are discussed in this section. Upadacitinib is another JAK/STAT inhibitor that is being studied for use in IBD. We have not included it in this review because robust data from a recently completed phase II study are not yet publicly available.

Tofacitinib

Tofacitinib is an oral small molecule that potently inhibits JAK1 and JAK3, and to a lesser degree JAK2. It is currently approved for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and psoriatic arthritis, and recent findings are promising for its use in UC—more so than in CD.62–64 In 3 phase III randomized trials, investigators evaluated the use of tofacitinib as induction and maintenance therapy for patients with moderately to severely active UC. The Oral Clinical Trials for tofAcitinib in ulcerative colitis (OCTAVE) Induction 1 and 2 trials included patients with active UC and with previous conventional IBD therapy or anti-TNF treatment, respectively. In a double-blinded fashion, 598 and 541 patients in OCTAVE 1 and 2, respectively, were randomized to receive placebo or tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily. The primary end point was clinical remission at week 8, which was achieved in 18.5% of patients receiving tofacitinib vs 8.2% in the placebo group (P = 0.007) in OCTAVE 1, and in 16.6% of the tofacitinib group vs 3.6% of the placebo group (P < 0.001) in OCTAVE 2. In the subsequent 52-week OCTAVE Sustain trial, patients with a clinical response to induction therapy in OCTAVE 1 and 2 were randomized to receive placebo or tofacitinib (5 mg or 10 mg twice daily). The primary end point, clinical remission at week 52, was achieved in 11.1% of patients receiving placebo, 34.3% of patients receiving tofacitinib 5 mg (P < 0.001), and 40.6% of those receiving tofacitinib 10 mg (P < 0.001). Of note, mucosal healing at 52 weeks occurred at a significantly higher rate in the 2 active drug groups, in comparison with the placebo group (P < 0.001).64

In a separate randomized, double-blind phase IIb trial, 280 patients with moderate to severe CD received placebo or tofacitinib (5 mg or 10 mg) twice daily for 8 weeks as induction treatment.63 Those who achieved remission or clinical response (defined as a decrease in CDAI of at least 100 points from baseline) continued to the maintenance treatment phase of the trial and were re-randomized to receive placebo or tofacitinib (5 mg or 10 mg) twice daily for 26 weeks. The primary end point of the induction study was clinical remission at week 8 (defined as a CDAI score <150), which was achieved by 36.7% of those in the placebo group, compared with 43.5% in the 5-mg group (P = 0.325) and 43.0% in the 10-mg group (P = 0.392). Although there was no significant difference in rates of clinical remission between the study arms, the 2 treatment groups had greater improvement from their baseline CDAI score when compared with the placebo group, and this was statistically significant in the group that received 5 mg of tofacitinib (P < 0.05). In the maintenance phase of the study, the proportion of patients meeting the primary end point of remission or clinical response was not significantly different between the groups. However, a numerically greater proportion of patients achieved the primary end point in the tofacitinib 10-mg group compared with the placebo group (55.8% vs 38.1%).

Tofacitinib is well tolerated in IBD treatment, and the most commonly reported adverse events, present in at least 5% of any study group, in patients with CD were headache, nausea, abdominal pain, CD flare, and arthralgia. Observed infections were rare and included nasopharyngitis and urinary tract infection.63 In the OCTAVE 1 and 2 induction trials in patients with UC, AEs occurred in 59.8% and 52.7% of placebo patients and 56.5% and 54.1% of treatment patients, respectively. The most frequent AEs were worsening UC, nasopharyngitis, arthralgia, and headache; the percentages of these AEs were not reported. These findings were also noted in the 52-week maintenance study; there was no difference in the occurrence of adverse events between the treatment and placebo groups.64 Larger increases in serum total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein, and high-density lipoprotein were seen in patients receiving tofacitinib compared with placebo, although this effect plateaued at 4 weeks in UC patients.63, 64 Serious infections including pneumonia, urinary tract infection, cellulitis, and cases of single and multidermatomal herpes zoster infection have been reported with tofacitinib; in OCTAVE Sustain, reported cases of herpes zoster infection were as high as 5.1% in patients receiving tofacitinib 10 mg.61, 63–65 In patients with IBD, herpes zoster infection was not serious and did not require drug discontinuation.63, 64

The American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) recommends that all IBD patients over the age of 50 years be immunized against herpes zoster.66 Previously, the only option for immunization against herpes zoster was the live zoster vaccine (Zostavax, Merck). As it is a live vaccine, it could only be administered to immunocompetent individuals and in patients on low-dose immunosuppression. In October 2017, an inactivated recombinant herpes zoster vaccine with a potent adjuvant was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA; Shingrix) for immunocompetent patients. The 2018 Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) guidelines recommend 2 doses of Shingrix given 8 weeks apart, including in patients who had previously received the live attenuated vaccine.67 Shingrix was recommended over Zostavax in immunocompetent patients who had not received Zostavax. The efficacy of Shingrix has been shown to be greater than 90% in the general population. Research is needed to assess the safety and efficacy of Shingrix in patients younger than 50 years of age and in immunocompromised patients.68

Across all OCTAVE studies, 1 patient suffered a colonic perforation in the setting of recent Cytomegalovirus colitis and concomitant steroid use.64 Tofacitinib was approved in May of 2018 for use in patients with moderate to severe UC in the United States.69 It is the first oral medication and JAK/STAT inhibitor to be approved for use in IBD by the FDA. The FDA’s Gastrointestinal Drugs Advisory Committee supported an induction regimen of tofacitinib 10 mg (2 times a day) for 8 weeks, with the option of extending this to 16 weeks in those with poor response.70 Maintenance therapy is with twice-daily dosing of tofacitinib 5 mg or 10 mg. Of note, the FDA recommends against the use of tofacitinib in combination with biologic therapies or immunosuppressants, such as cyclosporine and azathioprine.69

Filgotinib

Filgotinib is a once-daily, orally available agent that is a highly selective inhibitor of JAK1.71 Unlike tofacitinib, which demonstrated poor efficacy in phase IIb trials in CD patients, filgotinib has preliminarily been shown to be effective in CD and may be particularly useful in those with previous anti-TNF exposure. In the phase II FITZROY study, 174 patients with moderate to severe CD confirmed by centrally read endoscopy—with or without previous anti-TNF exposure—were randomized in a 3:1 fashion to receive a once-daily dose of 200 mg of filgotinib or placebo for 10 weeks.72 Clinical remission at week 10 (CDAI of <150) was attained by 47% of patients in the filgotinib group, compared with 23% in the placebo group (difference 24%; P = 0.0077). CDAI-100 response at week 10 was also higher in those who received filgotinib (59% vs 41%; P = 0.0453). A greater degree of improvement in biomarkers, endoscopic findings, and histology was also seen in the filgotinib-treated group. Sixty percent of anti-TNF-naïve patients who received the active drug achieved clinical remission, compared with 37% who were anti-TNF experienced.

In part 2 of the FITZROY study, maintenance of response was observed over an additional 10 weeks, and patients were assigned to receive once-daily filgotinib (100 mg or 200 mg) or placebo. Although this aspect of the study was not adequately powered to measure efficacy, some of its observations are noteworthy. In those who failed to respond to placebo at week 10 and then received filgotinib 100 mg in the maintenance phase, 32% achieved clinical remission and 59% showed clinical response at week 20. A safety analysis was conducted for the entire 20-week period of the FITZROY study, and filgotinib was found to be generally well tolerated, with a similar proportion of patients in the active treatment and placebo groups having at least 1 treatment-related adverse event (75% vs 67%). Serious adverse events and serious infections were rare and comparable between the groups, but discontinuation due to adverse events was seen in a higher proportion of patients in the filgotinib group (18% vs 9%). Some of the infections observed in this study include nasopharyngitis, oral candidiasis, and urinary tract infections. Four cases of oral candidiasis and 1 case of herpes zoster were seen, all in patients who received filgotinib. Phase III trials are currently underway to investigate the efficacy and safety of filgotinib in patients with CD (ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers: NCT02914600, NCT02914561) and UC (ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers: NCT02914535, NCT02914522).

SPHINGOSINE-1-PHOSPHATE RECEPTOR MODULATOR

Ozanimodh

Ozanimod is an orally administered small molecule with agonist activity for the sphingosine-1-phosphate 1 and 5 (S1P1 and S1P5) receptors. The sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor is comprised of 5 subtypes and plays an important role in cell proliferation and migration, intercellular communication, and the maintenance of vascular tone and other cardiovascular effects.73–75 The S1P1 receptor is found on the cell surface of lymphocytes and is crucial in their migration from secondary lymphoid organs to the blood and tissues. As an agonist of the S1P1 and S1P5 receptors, ozanimod induces receptor internalization and degradation, thus preventing the migration of lymphocytes along a chemotactic gradient from lymphoid organs into the circulation, and to the gut.76 The selective immunomodulatory action of ozanimod on only S1P1 and S1P5 is particularly important and is an improvement over fingolimod—another drug with a similar mechanism of action. Fingolimod is a nonselective S1P1 receptor that also binds to the S1P3, S1P4, and S1P5 receptors and is approved for the treatment of relapsing multiple sclerosis. Due to its nonselectivity, it is associated with significant cardiac, vascular, ocular, and gastrointestinal adverse effects and is not recommended for the treatment of IBD.77, 78

Ozanimod has been shown to be effective in the treatment of UC. In a double-blind, placebo-controlled phase II trial, 197 patients with moderate to severe UC were randomized to received placebo or ozanimod at a daily dose of either 0.5 mg or 1 mg for up to 32 weeks.79 Clinical remission at week 8 was significantly greater in those who received a daily dose of 1 mg in comparison with placebo (16% vs 6%; P = 0.048). At week 8, clinical response and mucosal healing were significantly higher in both ozanimod arms compared with placebo. At week 32, significantly higher rates of clinical remission, clinical response, mucosal healing, and histologic remission were noted in those receiving 1 mg of ozanimod compared with placebo.

Adverse events were rare in this study, and they were not differentially distributed in the ozanimod drug and placebo groups. The most frequently reported adverse events included exacerbation of UC, anemia, headaches, and elevation of serum liver enzymes. A patient with preexisting bradycardia in the 0.5-mg ozanimod group was removed from further participation in the study because of the development of asymptomatic first-degree atrio-ventricular block. Squamous cell carcinoma occurred in a patient in the 1-mg ozanimod group, but this patient had been previously exposed to mercaptopurine. Overall, although ozanimod was found to be well tolerated, this study was not of sufficient size and duration to effectively evaluate its long-term safety outcomes. On review of the other clinical uses of ozanimod, safety data from the treatment of MS have also shown it to be safe.80 In a phase II randomized, placebo-controlled trial of 258 participants with relapsing MS, patients in the active drug groups received 0.5 mg and 1 mg of ozanimod daily, and there were no major cardiovascular, infectious pulmonary, or cancer-related adverse events reported. A phase III study on the use of ozanimod for induction and maintenance therapy is currently underway in UC patients (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02435992), and it is also being evaluated in a phase II trial as induction therapy in patients with moderate to severe CD (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02531113).

STEM CELL THERAPY FOR PERIANAL CD

Local injection of mesenchymal stem cell therapy has recently been found to be effective in the management of perianal CD. Perianal fistulas are a common complication of CD, and within 20 years of diagnosis, about one-third of patients will have developed these.81, 82 They deeply impact the quality of life of affected patients and are associated with significant morbidity.83 Perianal fistulas are poorly responsive to treatment, and current biologic therapy only produces durable fistula closure in less than one-quarter of affected patients.84, 85 Surgical options are also limited in their likelihood of producing long-term fistula closure, and they carry the additional risk of incontinence. For these reasons, effective treatments for perianal fistula with favorable side effect profiles have been sought, and mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are a frontrunner in this regard. The mechanism of action of MSCs in fistula healing is not well understood, but it is thought to be due to the immunomodulatory and growth-promoting effects, ultimately leading to a reduction in inflammation and healing.86, 87 Cx601 (consisting of allogeneic expanded adipose-derived stem cells) was approved by the European Commission for the treatment of complex perianal fistulas in those with inadequate response to previous biologic therapy in March of 2018, and was recently designated an orphan drug by the FDA in the United States.88, 89

In several clinical trials, MSC therapy has been shown to be effective and safe in promoting the healing of perianal fistulas. Using Cx601, Panes et al. conducted a multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase III study among 212 CD patients with treatment-refractory and complex perianal fistulas.90, 91 In addition to standard of care, patients received a 1-time injection of 120 million Cx601 cells or placebo into their perianal fistulas. The study’s primary end point was combined remission at week 24, as defined by clinical and radiologic criteria. This was met by 51.5% of those in the Cx601 group compared with 35.6% in the control group (P = 0.021). At week 52, combined remission (P = 0.010) and clinical remission (P = 0.013) remained higher in the treatment group.

Over the 52-week study period, Cx601 was found to be well tolerated, and there were comparable treatment-emergent adverse events in the drug and placebo groups. The most frequent adverse events were anal abscesses and fistulas, proctalgia, diarrhea, and nasopharyngitis. A greater proportion of patients in the placebo group (26.5%) experienced treatment-related adverse events, and the commonly reported ones in this group were proctalgia and anal abscess/fistula. Three subjects (all controls) had an exacerbation of CD. A systematic review and meta-analysis including 11 studies has similarly found MSCs to be safe in the treatment of perianal fistula in CD.92 A multicenter phase III study is currently recruiting CD patients with complex perianal fistulas to evaluate the efficacy and safety of Cx601. In this placebo-controlled trial, combined remission will be measured at 24 weeks, with a follow-up period of up to 52 weeks (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03279081).

CONCLUSIONS

The introduction of anti-TNFs to the therapeutic landscape of IBD has resulted in improved patient outcomes on multiple fronts. However, a significant proportion of patients will have nonresponse, loss of response, or intolerance to this class of drugs, and there is a need for safe and effective alternatives for disease management. In this paper, we have reviewed the new and emerging therapies for the treatment of IBD, with a special emphasis on their safety profile (Table 1).

A few of these agents, like natalizumab, have been available for several years, and others are new and offer unique advantages—such as the oral route of administration with the JAK/STAT inhibitors and the local application of stem cell therapy for perianal CD. Although the availability of these therapies has greatly improved the outlook for IBD management, it is important to remember that many of these agents are new or still in the development pipeline, and a balance of efficacy and safety should be actively pursued when making treatment decisions. Of note, the increased risk of PML has significantly limited the use of natalizumab, and it is rarely used in clinical practice. Vedolizumab is the recommended anti-adhesion agent for IBD, as robust safety studies have shown it to be well tolerated. For moderate to severe CD, ustekinumab should be considered in patients who are naïve or unresponsive to biologic therapy. Although its safety data is limited in IBD, long-term studies in patients treated for other conditions with ustekinumab have revealed good tolerability. The oral availability of the recently approved JAK/STAT inhibitor tofacitinib is a major advantage, and, coupled with its nonimmunogenicity, it could significantly impact the future management of moderately to severely active UC. The risk of herpes zoster is considerable with tofacitinib, and real-world experience is needed for a complete evaluation of its clinical suitability and safety.

The future of IBD therapeutics is promising, as novel drug mechanisms such as phosphodiesterase 4 inhibition are being explored. These developments are exciting and have resulted in many treatment options for IBD patients. Priorities for future drug development should necessarily emphasize a balance of efficacy, safety, and ease of administration and should focus on new immune pathways.

Conflicts of interest: R.K.C. has research grants with Abbvie and participates in consulting and advisory boards for Abbvie, Janssen, and Pfizer. F.A.F. participates in consulting and advisory boards for Braintree labs, Ferring, Janssen, Merck, Pfizer, and Takeda, is a member of the data safety monitoring board for Lilly, Protagonist, and Theravance, and is a stock holder for Innovation Pharmaceuticals. K.O.C.O. and K.E.C. have no conflicts to report.

Supported by: K.O.C.O. is supported by a T32 Research Grant (DK067872-11) from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

REFERENCES

- 1. Kappelman MD, Rifas-Shiman SL, Porter CQ, et al. Direct health care costs of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in US children and adults. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1907–1913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kim NH, Jung YS, Moon CM, et al. Long-term clinical outcomes of Korean patient with Crohn’s disease following early use of infliximab. Intest Res. 2014;12:281–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sokol H, Seksik P, Cosnes J. Complications and surgery in the inflammatory bowel diseases biological era. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2014;30:378–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Generini S, Giacomelli R, Fedi R, et al. Infliximab in spondyloarthropathy associated with Crohn’s disease: an open study on the efficacy of inducing and maintaining remission of musculoskeletal and gut manifestations. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63:1664–1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Colombel JF, Schwartz DA, Sandborn WJ, et al. Adalimumab for the treatment of fistulas in patients with Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2009;58:940–948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yanai H, Hanauer SB. Assessing response and loss of response to biological therapies in IBD. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:685–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ben-Horin S, Chowers Y. Review article: loss of response to anti-TNF treatments in Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:987–995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Siegel CA, Marden SM, Persing SM, et al. Risk of lymphoma associated with combination anti-tumor necrosis factor and immunomodulator therapy for the treatment of Crohn’s disease: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:874–881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Targownik LE, Bernstein CN. Infectious and malignant complications of TNF inhibitor therapy in IBD. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1835–42, quiz 1843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lichtenstein GR, Feagan BG, Cohen RD, et al. Serious infection and mortality in patients with Crohn’s disease: more than 5 years of follow-up in the TREAT™ registry. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1409–1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Keane J, Gershon S, Wise RP, et al. Tuberculosis associated with infliximab, a tumor necrosis factor alpha-neutralizing agent. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1098–1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ley K, Laudanna C, Cybulsky MI, et al. Getting to the site of inflammation: the leukocyte adhesion cascade updated. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:678–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zundler S, Becker E, Weidinger C, et al. Anti-adhesion therapies in inflammatory bowel disease-molecular and clinical aspects. Front Immunol. 2017;8:891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fiorino G, Correale C, Fries W, et al. Leukocyte traffic control: a novel therapeutic strategy for inflammatory bowel disease. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2010;6:567–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lobatón T, Vermeire S, Van Assche G, et al. Review article: anti-adhesion therapies for inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39: 579–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ghosh S, Goldin E, Gordon FH, et al. ; Natalizumab Pan-European Study Group Natalizumab for active Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:24–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rogler G. Where are we heading to in pharmacological IBD therapy?Pharmacol Res. 2015;100:220–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Armuzzi A, Felice C. Natalizumab in Crohn’s disease: past and future areas of applicability. Ann Gastroenterol. 2013;26:189–190. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Villablanca EJ, Cassani B, von Andrian UH, et al. Blocking lymphocyte localization to the gastrointestinal mucosa as a therapeutic strategy for inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1776–1784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Targan SR, Feagan BG, Fedorak RN, et al. ; International Efficacy of Natalizumab in Crohn’s Disease Response and Remission (ENCORE) Trial Group Natalizumab for the treatment of active Crohn’s disease: results of the ENCORE trial. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:1672–1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yednock TA, Cannon C, Fritz LC, et al. Prevention of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by antibodies against alpha 4 beta 1 integrin. Nature. 1992;356:63–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bloomgren G, Richman S, Hotermans C, et al. Risk of natalizumab-associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1870–1880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Honey K. The comeback kid: TYSABRI now FDA approved for Crohn disease. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:825–826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chalkley JJ, Berger JR. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in multiple sclerosis. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2013;13:408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Rutgeerts P, et al. GEMINI 2 Study Group Vedolizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:711–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Feagan BG, Rutgeerts P, Sands BE, et al. GEMINI 1 Study Group Vedolizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:699–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sands BE, Feagan BG, Rutgeerts P, et al. Effects of vedolizumab induction therapy for patients with Crohn’s disease in whom tumor necrosis factor antagonist treatment failed. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:618–627.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yajnik V, Khan N, Dubinsky M, et al. Efficacy and safety of vedolizumab in ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease patients stratified by age. Adv Ther. 2017;34:542–559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dulai PS, Singh S, Jiang X, et al. The real-world effectiveness and safety of vedolizumab for moderate-severe Crohn’s disease: results from the US VICTORY consortium. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:1147–1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Colombel JF, Sands BE, Rutgeerts P, et al. The safety of vedolizumab for ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2017;66:839–851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zeronico M, Blake A, Rana-Khan Q, et al. Tuberculosis in patients treated with vedolizumab: clinical trial and post-marketing case series. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11:S410–S411. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Löwenberg M, D’Haens G. Next-generation therapeutics for IBD. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2015;17:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lin KK, Mahadevan U. Etrolizumab: anti-β7-a novel therapy for ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:307–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schön MP, Arya A, Murphy EA, et al. Mucosal T lymphocyte numbers are selectively reduced in integrin alpha E (CD103)-deficient mice. J Immunol. 1999;162:6641–6649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cepek KL, Parker CM, Madara JL, et al. Integrin alpha E beta 7 mediates adhesion of T lymphocytes to epithelial cells. J Immunol. 1993;150:3459–3470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Karecla PI, Bowden SJ, Green SJ, et al. Recognition of E-cadherin on epithelial cells by the mucosal T cell integrin alpha M290 beta 7 (alpha E beta 7). Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:852–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Vermeire S, O’Byrne S, Keir M, et al. Etrolizumab as induction therapy for ulcerative colitis: a randomised, controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2014;384:309–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rutgeerts PJ, Fedorak RN, Hommes DW, et al. A randomised phase I study of etrolizumab (rhuMAb β7) in moderate to severe ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2013;62:1122–1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sugiura T, Kageyama S, Andou A, et al. Oral treatment with a novel small molecule alpha 4 integrin antagonist, AJM300, prevents the development of experimental colitis in mice. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:e533–e542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Yoshimura N, Watanabe M, Motoya S, et al. AJM300 Study Group Safety and efficacy of AJM300, an oral antagonist of α4 integrin, in induction therapy for patients with active ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:1775–1783.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Farkas S, Hornung M, Sattler C, et al. Blocking MAdCAM-1 in vivo reduces leukocyte extravasation and reverses chronic inflammation in experimental colitis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2006;21:71–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ghosh S, Panaccione R. Anti-adhesion molecule therapy for inflammatory bowel disease. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2010;3:239–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Vermeire S, Sandborn WJ, Danese S, et al. Anti-MAdCAM antibody (PF-00547659) for ulcerative colitis (TURANDOT): a phase 2, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;390:135–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Vermeire S, Ghosh S, Panes J, et al. The mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule antibody PF-00547,659 in ulcerative colitis: a randomised study. Gut. 2011;60:1068–1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Fedorak RN, et al. Ustekinumab Crohn’s Disease Study Group A randomized trial of ustekinumab, a human interleukin-12/23 monoclonal antibody, in patients with moderate-to-severe Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1130–1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Trinchieri G. Interleukin-12 and the regulation of innate resistance and adaptive immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:133–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Iwakura Y, Ishigame H. The IL-23/IL-17 axis in inflammation. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1218–1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Benson JM, Peritt D, Scallon BJ, et al. Discovery and mechanism of ustekinumab: a human monoclonal antibody targeting interleukin-12 and interleukin-23 for treatment of immune-mediated disorders. MAbs. 2011;3:535–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zaghi D, Krueger GG, Callis Duffin K. Ustekinumab: a review in the treatment of plaque psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:160–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Feagan BG, Sandborn WJ, Gasink C, et al. UNITI–IM-UNITI Study Group Ustekinumab as induction and maintenance therapy for Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1946–1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Langley RG, Lebwohl M, Krueger GG, et al. PHOENIX 2 Investigators Long-term efficacy and safety of ustekinumab, with and without dosing adjustment, in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis: results from the PHOENIX 2 study through 5 years of follow-up. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:1371–1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kimball AB, Papp KA, Wasfi Y, et al. PHOENIX 1 Investigators Long-term efficacy of ustekinumab in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis treated for up to 5 years in the PHOENIX 1 study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1535–1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Fiorentino D, Ho V, Lebwohl MG, et al. Risk of malignancy with systemic psoriasis treatment in the psoriasis longitudinal assessment registry. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:845–854.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Gordon KB, Papp KA, Langley RG, et al. Long-term safety experience of ustekinumab in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis (part II of II): results from analyses of infections and malignancy from pooled phase II and III clinical trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:742–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kalb RE, Fiorentino DF, Lebwohl MG, et al. Risk of serious infection with biologic and systemic treatment of psoriasis: results from the Psoriasis Longitudinal Assessment and Registry (PSOLAR). JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:961–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Teng MW, Bowman EP, McElwee JJ, et al. IL-12 and IL-23 cytokines: from discovery to targeted therapies for immune-mediated inflammatory diseases. Nat Med. 2015;21:719–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Feagan BG, Sandborn WJ, D’Haens G, et al. Induction therapy with the selective interleukin-23 inhibitor risankizumab in patients with moderate-to-severe Crohn’s disease: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 study. Lancet. 2017;389:1699–1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Roskoski R., Jr Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors in the treatment of inflammatory and neoplastic diseases. Pharmacol Res. 2016;111:784–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Coskun M, Salem M, Pedersen J, et al. Involvement of JAK/STAT signaling in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Pharmacol Res. 2013;76:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Flamant M, Rigaill J, Paul S, et al. Advances in the development of Janus kinase inhibitors in inflammatory bowel disease: future prospects. Drugs. 2017;77:1057–1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Gladman D, Rigby W, Azevedo VF, et al. Tofacitinib for psoriatic arthritis in patients with an inadequate response to TNF inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1525–1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Danese S, Grisham M, Hodge J, et al. JAK inhibition using tofacitinib for inflammatory bowel disease treatment: a hub for multiple inflammatory cytokines. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2016;310:G155–G162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Panés J, Sandborn WJ, Schreiber S, et al. Tofacitinib for induction and maintenance therapy of Crohn’s disease: results of two phase IIb randomised placebo-controlled trials. Gut. 2017;66:1049–1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Sandborn WJ, Su C, Sands BE, et al. OCTAVE Induction 1, OCTAVE Induction 2, and OCTAVE Sustain Investigators Tofacitinib as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1723–1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Cohen SB, Tanaka Y, Mariette X, et al. Long-term safety of tofacitinib for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis up to 8.5 years: integrated analysis of data from the global clinical trials. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:1253–1262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Farraye FA, Melmed GY, Lichtenstein GR, et al. ACG clinical guideline: preventive care in inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:241–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Dooling KL, Guo A, Patel M, et al. Recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices for use of herpes zoster vaccines. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:103–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Colombel JF. Herpes zoster in patients receiving JAK inhibitors for ulcerative colitis: mechanism, epidemiology, management, and prevention. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24:2173–2182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approved new treatment for moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis 2018. https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm609225.htm. Accessed May 30, 2018.

- 70. Medscape. FDA panel backs proposed tofacitinib dosing for ulcerative colitis 2018. https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/893704-vp_1. Accessed May 20 2018.

- 71. Van Rompaey L, Galien R, van der Aar EM, et al. Preclinical characterization of GLPG0634, a selective inhibitor of JAK1, for the treatment of inflammatory diseases. J Immunol. 2013;191:3568–3577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Vermeire S, Schreiber S, Petryka R, et al. Clinical remission in patients with moderate-to-severe Crohn’s disease treated with filgotinib (the FITZROY study): results from a phase 2, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;389:266–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. O’Sullivan S, Dev KK. Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor therapies: advances in clinical trials for CNS-related diseases. Neuropharmacology. 2017;113:597–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Rosen H, Gonzalez-Cabrera PJ, Sanna MG, et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor signaling. Annu Rev Biochem. 2009;78:743–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Marsolais D, Rosen H. Chemical modulators of sphingosine-1-phosphate receptors as barrier-oriented therapeutic molecules. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8:297–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Mandala S, Hajdu R, Bergstrom J, et al. Alteration of lymphocyte trafficking by sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor agonists. Science. 2002;296:346–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Kappos L, Antel J, Comi G, et al. FTY720 D2201 Study Group Oral fingolimod (FTY720) for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1124–1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Jain N, Bhatti MT. Fingolimod-associated macular edema: incidence, detection, and management. Neurology. 2012;78:672–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Wolf DC, et al. TOUCHSTONE Study Group Ozanimod induction and maintenance treatment for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1754–1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Cohen JA, Arnold DL, Comi G, et al. RADIANCE Study Group Safety and efficacy of the selective sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor modulator ozanimod in relapsing multiple sclerosis (RADIANCE): a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15:373–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Ardizzone S, Porro GB. Perianal Crohn’s disease: overview. Dig Liver Dis. 2007;39:957–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Schwartz DA, Loftus EV Jr, Tremaine WJ, et al. The natural history of fistulizing Crohn’s disease in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:875–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Aguilera-Castro L, Ferre-Aracil C, Garcia-Garcia-de-Paredes A, et al. Management of complex perianal Crohn’s disease. Ann Gastroenterol. 2017;30:33–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Present DH, Rutgeerts P, Targan S, et al. Infliximab for the treatment of fistulas in patients with Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1398–1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Sands BE, Anderson FH, Bernstein CN, et al. Infliximab maintenance therapy for fistulizing Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:876–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Qiu Y, Li MY, Feng T, et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the efficacy and safety of stem cell therapy for Crohn’s disease. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2017;8:136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Chapel A, Bertho JM, Bensidhoum M, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells home to injured tissues when co-infused with hematopoietic cells to treat a radiation-induced multi-organ failure syndrome. J Gene Med. 2003;5:1028–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Healio. Stem cell therapy approved in Europe to treat fistulizing Crohn’s disease 2018. https://www.healio.com/gastroenterology/inflammatory-bowel-disease/news/ online/%7B3d74e894-207e-41d0-8437-058d37f302c4%7D/stem-cell-therapy- approved-in-europe-to-treat-fistulizing-crohns-disease. Accessed May 15 2018.

- 89. Globenewswire. TiGenix granted orphan drug designation from the U.S. FDA for Cx601 2017. https://globenewswire.com/news-release/2017/10/23/1151148/0/en/TiGenix-granted-Orphan-Drug-Designation-from-the-U-S-FDA-for-Cx601.html. Accessed May 12, 2018.

- 90. Panés J, García-Olmo D, Van Assche G, et al. ADMIRE CD Study Group Collaborators Expanded allogeneic adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (Cx601) for complex perianal fistulas in Crohn’s disease: a phase 3 randomised, double-blind controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;388:1281–1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Panés J, García-Olmo D, Van Assche G, et al. ADMIRE CD Study Group Collaborators Long-term efficacy and safety of stem cell therapy (Cx601) for complex perianal fistulas in patients with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:1334–1342.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Lightner AL, Wang Z, Zubair AC, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of mesenchymal stem cell injections for the treatment of perianal Crohn’s disease: progress made and future directions. Dis Colon Rectum. 2018;61:629–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]