Abstract

Aims: The nuclear receptor liver X receptor-α (LXRα) stimulates lipogenesis, leading to steatosis. Nuclear factor erythroid-2-related factor-2 (Nrf2) contributes to cellular defense mechanism by upregulating antioxidant genes, and may protect the liver from injury inflicted by fat accumulation. However, whether Nrf2 affects LXRα activity is unknown. This study investigated the inhibitory role of Nrf2 in hepatic LXRα activity and the molecular basis. Results: A deficiency of Nrf2 enhanced the ability of LXRα agonist to promote hepatic steatosis, as mediated by lipogenic gene induction. In hepatocytes, Nrf2 overexpression repressed gene transactivation by LXR-binding site activation. Consistently, treatment of mice with sulforaphane (an Nrf2 activator) suppressed T0901317-induced lipogenesis, as confirmed by the experiments using hepatocytes. Nrf2 activation promoted deacetylation of farnesoid X receptor (FXR) by competing for p300, leading to FXR-dependent induction of small heterodimer partner (SHP), which was responsible for the repression of LXRα-dependent gene transcription. In human steatotic samples, the transcript levels of LXRα and SREBP-1 inversely correlated with those of Nrf2, FXR, and SHP. Innovation: Our findings offer the mechanism to explain how decrease in Nrf2 activity in hepatic steatosis could contribute to the progression of NAFLD, providing the use of Nrf2 as a molecular biomarker to diagnose NAFLD. As certain antioxidants have the abilities to activate Nrf2, clinicians might utilize the activators of Nrf2 as a new therapeutic approach to prevent and/or treat NAFLD. Conclusion: Nrf2 activation inhibits LXRα activity and LXRα-dependent liver steatosis by competing with FXR for p300, causing FXR activation and FXR-mediated SHP induction. Our findings provide important information on a strategy to prevent and/or treat steatosis. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 15, 2135–2146.

Introduction

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is one of the most common causes of abnormal liver function, and is characterized by accumulation of triglycerides in hepatocytes. Lipid homeostasis is regulated by a family of transcription factors including the nuclear hormone receptor liver X receptor-α (LXRα). LXRα induces the expression of lipogenic genes that regulates the synthesis and uptake of cholesterol, fatty acids, triglycerides, and phospholipids directly or via transcriptional control of sterol regulatory element binding protein-1c (SREBP-1c). Since LXRα stimulates lipogenesis through the activation of SREBP-1c, lipogenic target gene expression associated with SREBP-1c can be reduced by inhibiting endogenous LXR ligand synthesis (11, 35).

Understanding the mechanisms underlying LXRα regulation is crucial for identifying potential targets in the treatment of NAFLD and for the development of therapeutic approaches. LXRα forms a heterodimer with retinoid X receptor-α (RXRα), which binds to the LXR response element (LXRE), and consequently promotes target gene induction (1). Small heterodimer partner (SHP), an atypical orphan nuclear receptor that lacks a conventional DNA binding domain, may suppress transcriptional activity of LXRα/RXRα heterodimer by competing with RXRα, and this suppression by SHP, in turn, inhibits LXRα target gene transcription (e.g., CYP7A1) (7).

Chronic oxidative stress is important in the pathogenesis of NAFLD due to a close link between dysregulated lipid homeostasis and free radical stress; free radical stress induced by fat or proinflammatory cytokines causes the development of chronic liver disease. The results of animal studies indicated higher free radical activity in NAFLD, as evidenced by increased mitochondrial superoxide and H2O2 production (39, 42). Nuclear factor erythroid-2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) contributes to cellular defense mechanisms through the induction of antioxidant genes, phase II metabolizing enzymes, and transporters (5, 26, 29): this transcription factor activates target genes through its binding to the antioxidant response elements (ARE) comprised in the promoter regions of detoxifying or antioxidant genes. Since Nrf2 combats cellular oxidative stress (27), it may protect the liver from injury inflicted by fat accumulation. Kim et al. reported that long-term feeding of high-fat diet (HFD) increased the mRNA level of Nrf2 (22). However, another group claimed a decrease in Nrf2 content after high-fat diet feeding (38). Although there is a controversy on the relationship between high-fat diet feeding and Nrf2 expression, the action of Nrf2 may be linked to the activities of nuclear receptors by diverse pathways.

Despite the finding that Nrf2 knockout exacerbated SREBP-1c induction by HFD feeding (38), it remains to be established whether Nrf2 affects hepatic LXRα activity, and if so, what the molecular basis is. This study investigated the potential inhibitory role of Nrf2 in LXRα activity and LXRα-dependent lipogenesis in gene-knockout animal and hepatocyte models, identifying the novel regulatory mechanism of Nrf2 in the activation of farnesoid X receptor (FXR). We also examined the ability of Nrf2 overexpression or its chemical activator to induce SHP as an inhibitory partner of LXRα downstream of FXR. Moreover, in patients with hepatic steatosis, an inverse correlation between hepatic LXRα and SREBP-1c transcripts and those of Nrf2, FXR and SHP was found. Here, we report that activated Nrf2 inhibits LXRα-dependent lipogenesis and thereby protects the liver from injury inflicted by excess fat accumulation. Our findings offer the possibility of a new therapeutic intervention in NAFLD.

Results

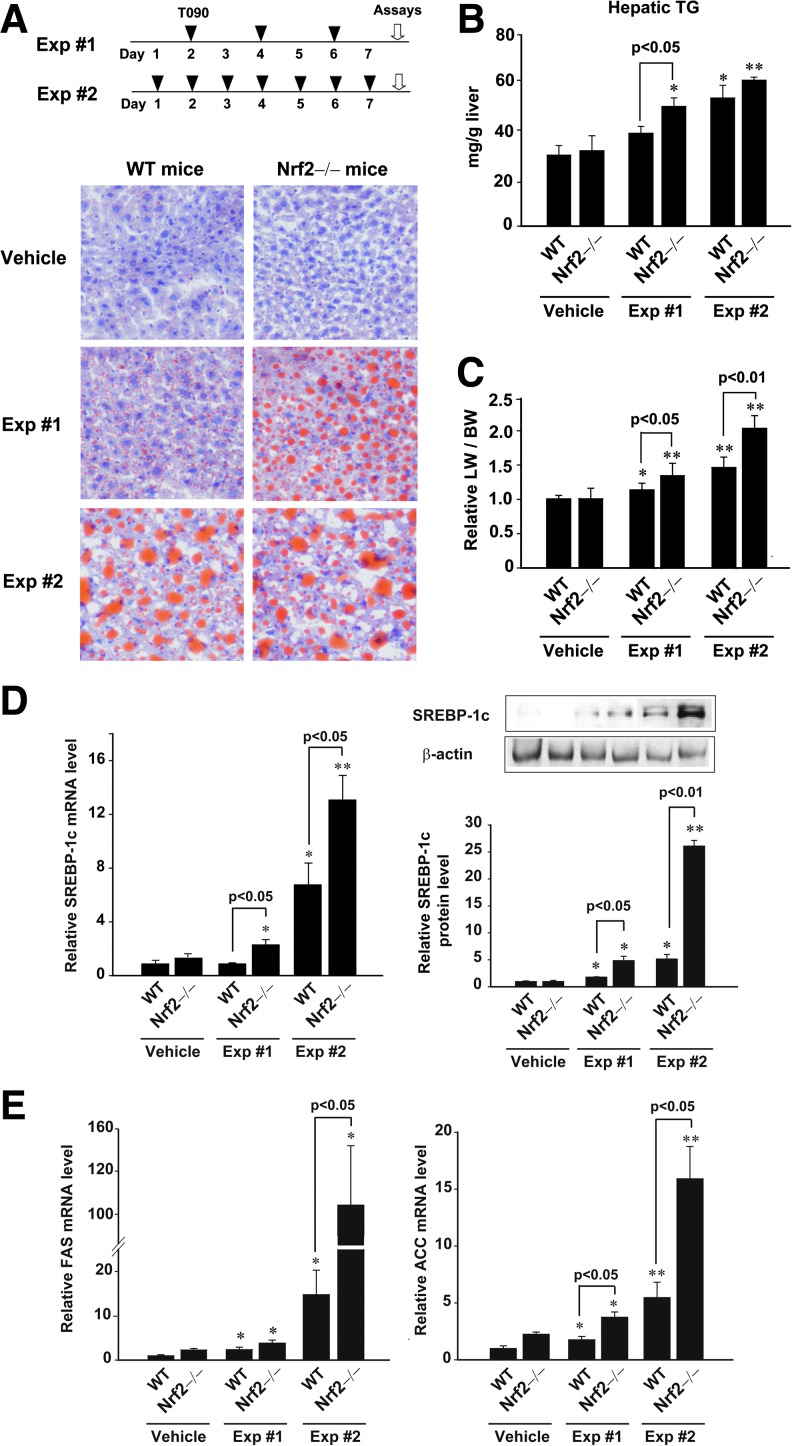

Enhancement of LXRα agonist-induced lipogenesis by Nrf2 deficiency

To determine whether Nrf2 plays a role in LXRα-mediated lipid accumulation, we first monitored the livers of wild-type (WT) and Nrf2 knockout mice after treatment with LXRα agonist (T0901317) three times per week (Exp #1). In another set of experiments, T0901317 was administered to mice everyday for a week (Exp #2). Nrf2 knockout mice showed no difference in hepatic fat accumulation or liver weight to body weight ratio compared to WT mice. As expected, mice administered with T0901317 for a week exhibited hepatic fat accumulation: Oil red O staining showed a successful increase in fat accumulation particularly in Exp #2 (Fig. 1A). Analyses of TG contents confirmed liver steatosis after daily treatment of T0901317 for a week (Fig. 1B). Of note, a deficiency of Nrf2 significantly enhanced fat accumulation in the liver in both experiments, verifying a bona fide increase in steatotic effect, which supports the hypothesis that Nrf2 antagonizes LXRα-dependent lipogenesis (Figs. 1A and 1B). In both sets, treatment of WT animals with T0901317 resulted in significant increases in the liver weight to body weight ratio (Fig. 1C). Consistently, liver weight gains were increased by T0901317 to a greater extent in Nrf2 knockout mice.

FIG. 1.

Increase in T090-induced lipogenesis by Nrf2 deficiency. (A) Treatment schedules of LXRα agonist (T090). WT or Nrf2 knockout mice were treated with T090 (50 mg/kg/day) for either 3 times per week (Exp #1) or 7 times per week (Exp #2). Oil Red O staining. (B) Hepatic TG contents. (C) Liver weight to body weight ratio. (D) Real-time PCR assays and immunoblottings for SREBP-1c. SREBP-1c levels were assessed in the livers of WT or Nrf2 knockout mice treated with T090. (E) Real-time PCR assays for FAS and ACC mRNAs. Data represent the mean±S.E. of 7 mice per each group; the statistical significance of differences between each knockout treatment group and the respective WT treatment group (*p<0.05, **p<0.01) were determined.

To confirm the effect of Nrf2 deficiency on SREBP-1c expression as a downstream protein of LXRα, we measured the mRNA and protein levels in the livers of mice exposed to T0901317. Real-time PCR analysis revealed that a deficiency of Nrf2 enhanced the ability of T0901317 to increase SREBP-1c mRNA levels (Fig. 1D, left). Also, SREBP-1c protein levels were comparably changed in the liver (Fig. 1D, right). Since SREBP-1c is an important downstream regulator of lipogenic enzyme gene induction, the effects of Nrf2 knockout on LXRα-dependent increases in fatty acid synthase (FAS) or acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) mRNA were studied. As expected, FAS or ACC mRNA levels were greatly increased by the absence of Nrf2 (Fig. 1E). Enhancement of hepatic steatosis parameters as well as lipogenic gene induction by Nrf2 deficiency paralleled the greater TG accumulation.

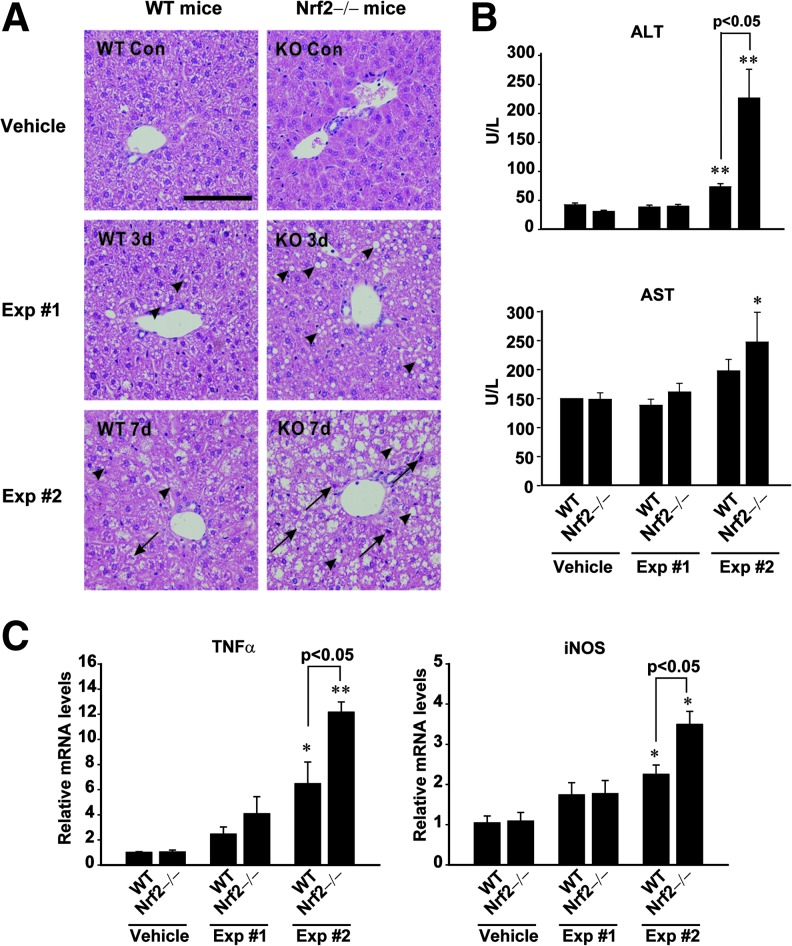

Enhancement of LXRα agonist-induced steatohepatitis by Nrf2 deficiency

In an effort to assess the effect of Nrf2 deficiency on hepatocyte damage, we compared the degrees of T0901317-induced liver injury in WT and Nrf2 knockout mice. In the histopathological assessment of liver, T0901317 treatments induced not only the formation of large cytoplasmic lipid droplets, but also hepatocyte death and infiltration of inflammatory cells, which was further promoted by a deficiency of Nrf2 (Fig. 2A). Histological activity indexes (HAI) of the samples were 0.9±0.2 (WT-vehicle), 2.0±0.4 (WT-Exp #1), 2.4±0.5 (WT-Exp #2), 1.0±0.4 (KO-vehicle), 2.6±0.4 (KO-Exp #1), and 3.2±0.3 (KO-Exp #2). Moreover, our findings indicate that the absence of Nrf2 enhanced the ability of T0901317 to increase plasma ALT activity in Exp #2 (Fig. 2B, upper). Plasma AST activity was also elevated in Nrf2 knockout mice treated with T0901317 everyday, as compared with control (Fig. 2B, lower). Consistently, TNFα and iNOS, inflammatory biomarkers, were both induced to a greater extent in the liver (Fig. 2C).

FIG. 2.

Increase in T090-induced steatohepatitis by Nrf2 deficiency. (A) Histopathology of hepatic central and portal areas. The liver sections of WT or Nrf2 knockout mice treated as described in Figure 1A were subjected to H&E staining. Microphotographs show views of the liver sections: arrows and arrowheads indicate necrosis and vacuole formation, respectively. (B) Blood biochemical parameters. Plasma transaminase activities were monitored in WT or Nrf2 knockout mice treated with T090. (C) Real-time PCR assays for TNFα and iNOS mRNAs. Data represent the mean±S.E. of 7 mice per each group; the statistical significance of differences between each knockout treatment group and the respective WT treatment group (*p<0.05, **p<0.01) were determined.

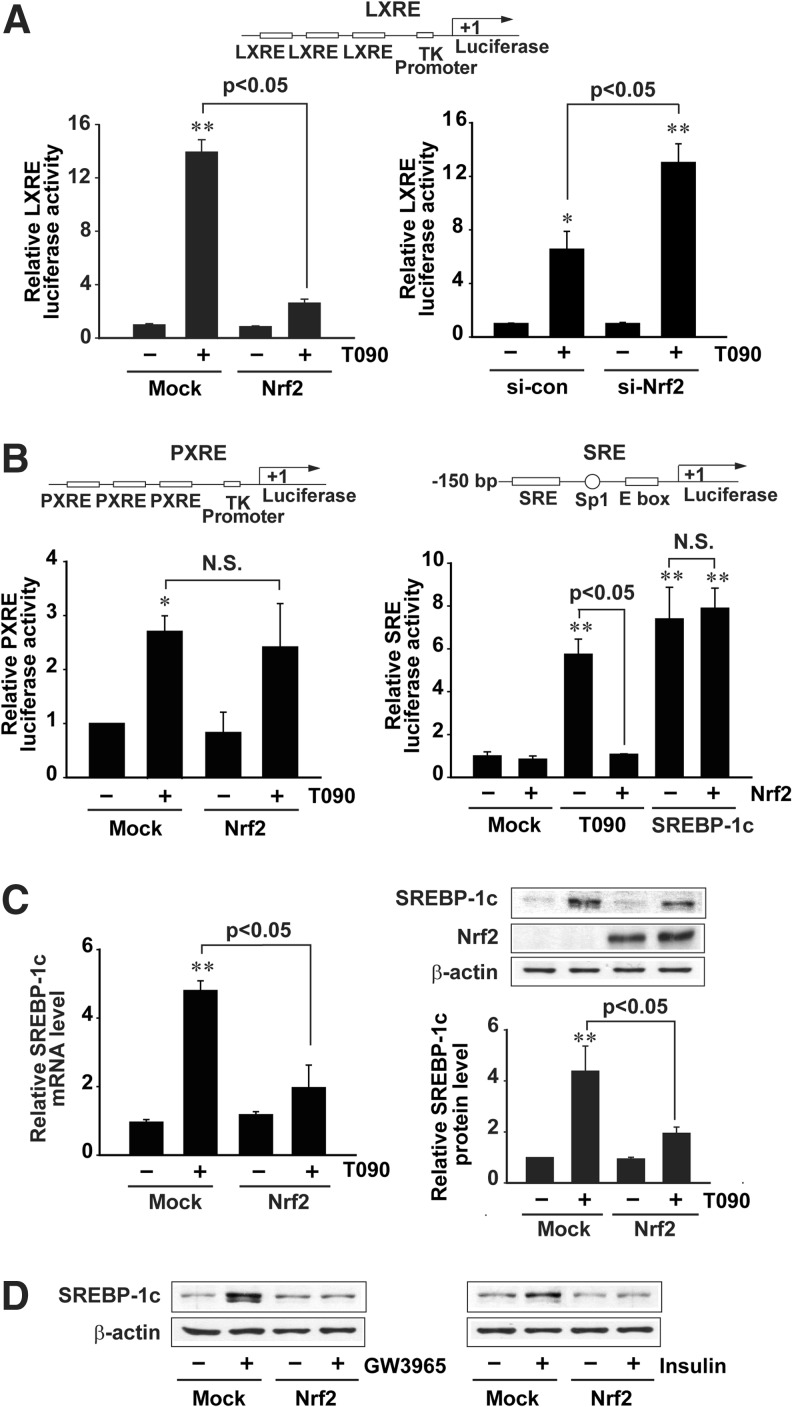

Specific inhibition of LXRE reporter activity by Nrf2 overexpression

To assess the molecular mechanisms responsible for the increased lipogenesis by Nrf2 deficiency in detail, the effect of enforced Nrf2 expression on LXRα-driven gene transactivation was monitored in HepG2 cells. As expected, Nrf2 overexpression prevented the ability of T0901317 to induce LXRE luciferase activity (Fig. 3A, left). Moreover, T0901317-induced LXRE luciferase activity was further increased by knockdown of Nrf2 (Fig. 3A, right). T0901317 may be a dual agonist for LXR and pregnane X receptor (PXR) (30). Since PXR may stimulate hepatic lipogenesis, we excluded its possible involvement in the anti-lipogenic effect of Nrf2. Nrf2 overexpression did not inhibit T0901317-induced PXR response elements (PXRE) reporter activity (Fig. 3B, left). To differentially understand the possible involvement of direct SREBP-1c modulation in the inhibition of LXRα-SREBP-1c system by Nrf2, we also examined the effect of Nrf2 on the transactivation of pGL-FAS luciferase gene that contains SREBP-1c response elements (SRE), but not LXRE. Nrf2 overexpression inhibited T0901317-induced luciferase activity, but unchanged an increase in luciferase expression from the SRE reporter construct by SREBP-1c overexpression (Fig. 3B, right). Our data showed that anti-lipogenesis of Nrf2 resulted from an alteration in the gene transcription driven by LXRE, but not PXR or SREBP-1c binding site. As a continuing effort, the effect of Nrf2 on LXRα target gene was monitored in HepG2 cells. Enforced expression of Nrf2 almost completely prevented the ability of T0901317 to induce SREBP-1c, as shown by lack of increases in its mRNA and protein (Fig. 3C). Moreover, Nrf2 abrogated the abilities of other LXR agonists, GW3965 (a synthetic LXRα agonist) and insulin, to induce SREBP-1c (Fig. 3D). Our results demonstrate that Nrf2 has an antagonistic effect on hepatic fat accumulation by inhibiting LXRα-dependent lipogenic gene induction.

FIG. 3.

Nrf2 repression of LXRE-mediated gene induction. (A) LXRE luciferase activities. The relative luciferase activities were measured on the lysates of HepG2 cells treated with 3 μM T090 for 24 h following transfection with TK-LXREx3 luciferase construct and Nrf2 plasmids. (B) PXRE and SRE luciferase activities. The relative luciferase activities were measured on the lysates of HepG2 cells treated with 3 μM T090 for 24 h following transfection with TK-PXREx3 luciferase construct and Nrf2 plasmids. To measure SRE luciferase activity, HepG2 cells were treated with 3 μM T090 for 24 h after transfection with pGL-FAS luciferase construct, Nrf2 and/or SREBP-1c. (C) Real-time PCR assays and immunoblottings for SREBP-1c. HepG2 cells were treated with T090 for 12 h after Nrf2 transfection. (D) Immunoblottings for SREBP-1c. Cells were treated with 10 μM GW3965 or 100 nM insulin for 12 h after Nrf2 transfection. Data represent the mean ± S.E. of 4 separate experiments; the statistical significance of differences between each treatment group and the control (**p < 0.01) or T090 alone were determined.

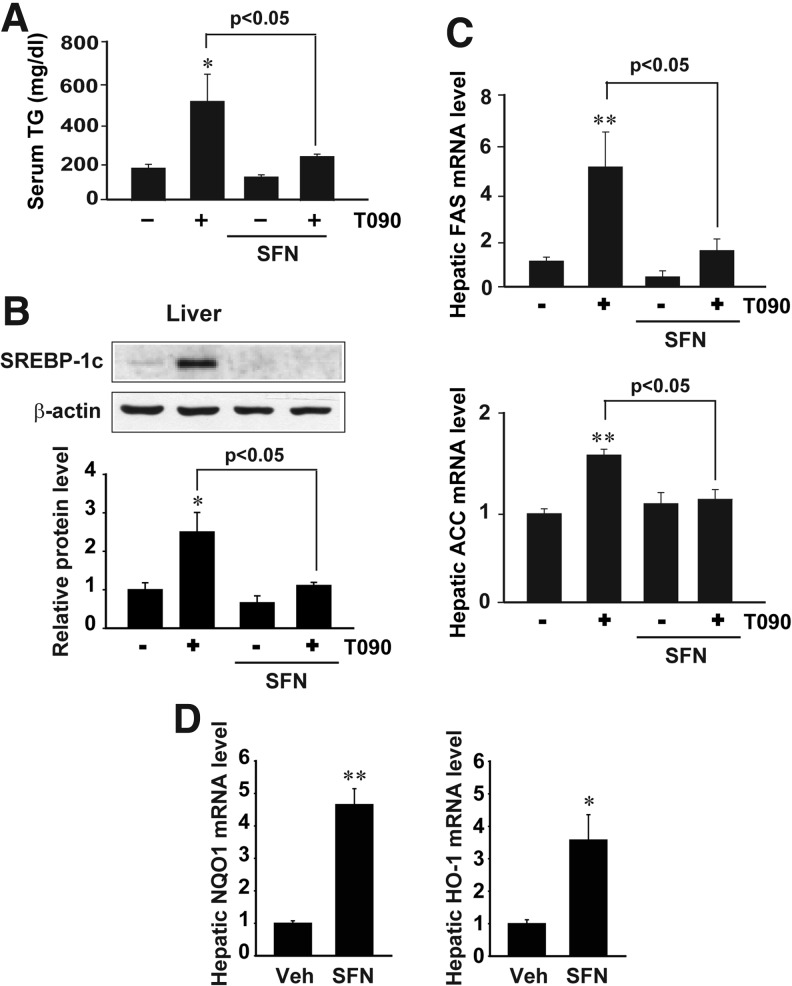

Inhibition by sulforaphane of LXRα-dependent induction of lipogenic genes

In subsequent experiments, sulforaphane was used as a representative Nrf2 activator to verify the inhibitory effect of Nrf2 on LXRα activity. Mice were treated with sulforaphane at the dose of 90 mg/kg/day for 2 days prior to T0901317 administration. Sulforaphane treatment suppressed T0901317-induced lipogenesis, as shown by a decrease in serum TG content (Fig. 4A). Similarly, the expressions of lipogenic genes (i.e., SREBP-1c, FAS, and ACC) were inhibited (Figs. 4B and 4C). Increases in the levels of NQO1 and HO-1 mRNA (Nrf2 target gene transcripts) by sulforaphane verified Nrf2 activation (Fig. 4D). Our results confirmed that sulforaphane diminished LXRα-induced hepatic lipogenesis, presumably as a consequence of Nrf2 activation.

FIG. 4.

Inhibition by sulforaphane of T090-mediated lipogenesis in vivo. (A) Serum TG contents. Mice were exposed to a single dose of 50 mg/kg T090 after sulforaphane (SFN) treatment (90 mg/kg/day, for 2 days). (B) Immunoblottings for hepatic SREBP-1c. Immunoblottings were performed 24 h after T090 treatment. (C) Real-time PCR assays for hepatic lipogenic gene transcripts. (D) Real-time PCR assays for hepatic NQO1 and HO-1 transcripts. Data represent the mean±S.E. of 5 mice per each treatment group; the statistical significance of differences between each treatment group and the vehicle-treated control (*p<0.05, **p<0.01) or T090 alone were determined.

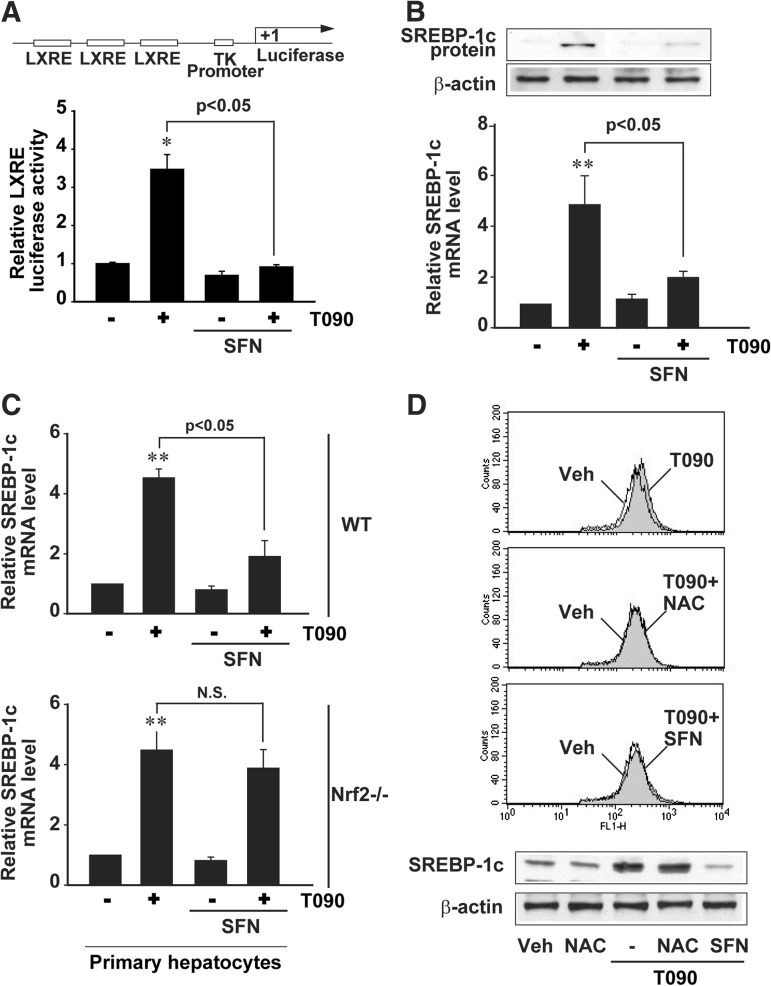

To understand the effect of sulforaphane on LXRα activity more precisely, anti-lipogenic effect was monitored in hepatocyte models. In HepG2 cells, sulforaphane (10 μM) completely inhibited LXRE reporter gene induction by T0901317 (Fig. 5A). Consistently, the ability of T0901317 to increase SREBP-1c mRNA and protein was antagonized by the Nrf2 activator (Fig. 5B). By the same token, sulforaphane had an inhibitory effect on the increase in SREBP-1c mRNA in primary hepatocytes (Fig. 5C). Nrf2 knockout eliminated the beneficial effect. N-acetylcysteine prevented T0901317-induced hydrogen peroxide production (i.e., dichlorofluorescein oxidation), as did sulforaphane. However, N-acetylcysteine failed to inhibit T0901317-induced SREBP-1c induction (Fig. 5D), indicating that antioxidant effect alone may not be sufficient to inhibit LXRα activity. Collectively, these findings demonstrate that chemical activation of Nrf2 abrogates the transcriptional activity of LXRα in the liver, causing repression of SREBP-1c and lipogenic genes.

FIG. 5.

Inhibition by sulforaphane of T090-mediated induction of SREBP-1c and lipogenic genes in hepatocytes. (A) LXRE reporter activity. Luciferase expression from TK-LXREx3 luciferase construct was measured on the lysates of HepG2 cells that had been treated with 10 μM SFN for 1 h and continuously exposed to 3 μM T090 for 24 h. (B) Effect of SFN on SREBP-1c expression. The levels of SREBP-1c mRNA and protein were measured in HepG2 cells treated as described in (A). (C) Real-time PCR assays for SREBP-1c mRNA. Primary hepatocytes were treated as described above. (D) Effects of NAC and SFN on DCFH oxidation and SREBP-1c induction. HepG2 cells were treated with 1 mM NAC or 10 μM SFN for 1 h and continuously exposed to T090 for 12 h. For DCFH oxidation assay, 10 μM of T090 was used to increase hydrogen peroxide generation. Data represent the mean±S.E. of four separate experiments. The statistical significance of differences between each treatment group and the control (*p<0.05, **p<0.01) or T090 alone were determined. DCFH, dichlorofluorescein; NAC, N-acetylcysteine; N.S., not significant; SFN, sulforaphane.

Nrf2 activation of FXR that represses LXRα activity

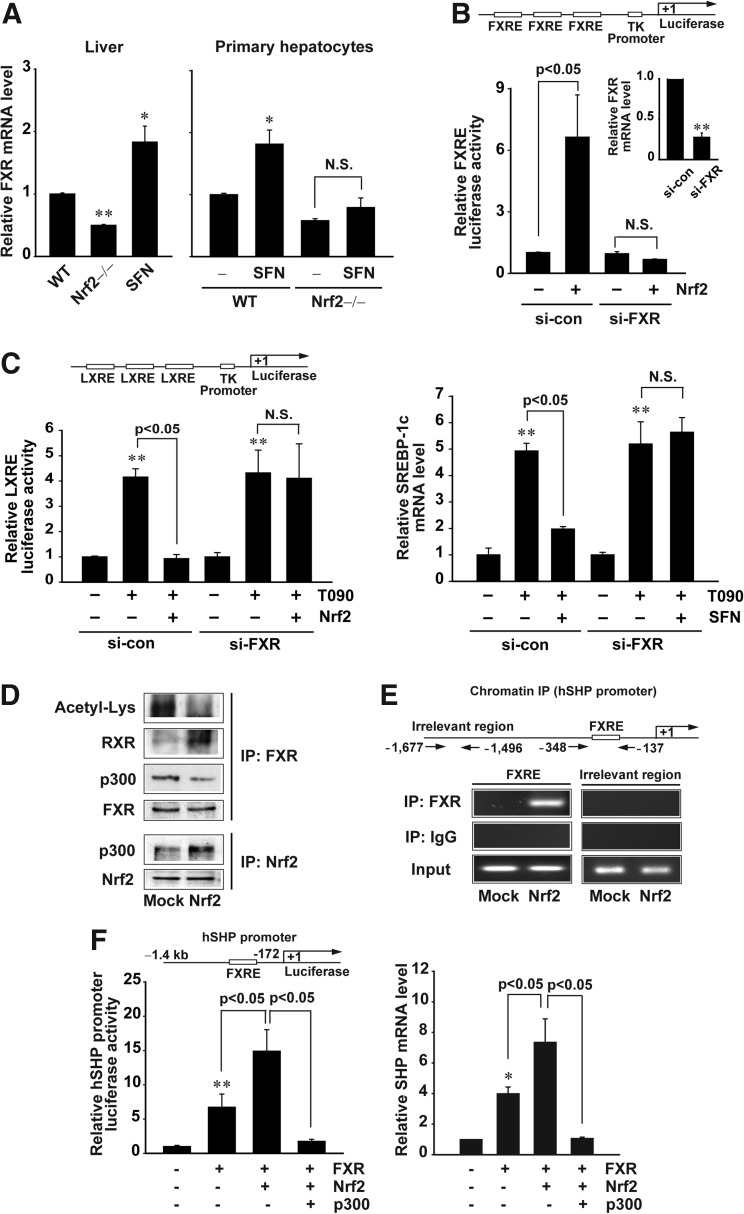

Nrf2 regulates the expression of certain FXR target genes, including bsep and mrp1 genes (18, 41). Since FXR plays a role in the homeostasis of hepatic fatty acid and lipid, we investigated whether Nrf2 activates FXR. Intriguingly, Nrf2 knockout mice exhibited a decrease in basal hepatic FXR mRNA, whereas sulforaphane treatment increased its expression (Fig. 6A, left). Similar results were obtained in the experiments using primary hepatocytes from WT or Nrf2-null mice (Fig. 6A, right). Consistently, FXR knockdown abolished the induction of FXR response element (FXRE) reporter activity by Nrf2 (Fig. 6B). In addition, FXR knockdown reversed the ability of Nrf2 to repress LXRE reporter activity and SREBP-1c mRNA increase (Fig. 6C). Our results demonstrate that FXR activation by Nrf2 has an inhibitory effect on LXRα.

FIG. 6.

Effects of Nrf2 on FXR deacetylation and FXR-dependent SHP induction. (A) Real-time PCR assays for FXR mRNA. The mRNA levels were determined in the livers of WT or Nrf2 knockout mice treated with vehicle or SFN (left), or in primary hepatocytes treated with vehicle or 10 μM SFN for 12 h (right). (B) FXRE reporter gene induction by Nrf2. The luciferase reporter gene activity was measured in cells transfected with Mock or Nrf2 plasmid after siRNA knockdown of FXR. (C) Reversal by FXR knockdown of Nrf2′s repression of LXRE reporter activity (left) or SREBP-1c mRNA increase (right). Luciferase expression from TK-LXREx3 construct was measured on the lysates of cells treated with T090 for 12 h after transfection with the plasmid of Nrf2, and/or control siRNA (nontargeting) or FXR siRNA. SREBP-1c mRNA was assessed by real-time PCR assays. (D) Decrease in FXR acetylation by the binding of Nrf2 with p300. Immunoblottings for acetylated lysine, RXRα, or p300 were performed on FXR immunoprecipitates prepared from HepG2 cells transfected with Nrf2. Nrf2 immunoprecipitate was immunoblotted with anti-p300 antibody. (E) ChIP assays. DNA–protein complexes were precipitated with anti-FXR antibody, and were subjected to PCR amplifications using the flanking primers for the FXRE or an irrelevant region. One tenth of cross-linked lysates served as the input control. (F) Reversal by p300 transfection of FXR- and/or Nrf2-induced FXRE reporter activity (left) or SHP mRNA increase (right). Luciferase expression from human SHP promoter was determined on the lysates of cells following different transfection combinations of FXR, Nrf2, and p300. SHP mRNA was assessed by real-time PCR assays. Data represent the mean±S.E. of four separate experiments; the statistical significance of differences between each treatment group and the control (*p<0.05, **p<0.01) were determined. N.S., not significant.

Deacetylation of FXR increases FXR/RXRα heterodimerization and DNA complex formation for gene transactivation (21). FXR acetylation as mediated by p300 is enhanced in metabolic disease (12, 21). In an attempt to identify the molecular basis of FXR activation by Nrf2, we examined the effect of Nrf2 on the status of FXR acetylation. Enforced expression of Nrf2 decreased FXR acetylation with an increase in FXR interaction with RXRα (Fig. 6D, upper). This event was not reversed by sirtinol, an inhibitor of the sirtuin class of deacetylases (data not shown), suggesting that deacetylation of FXR elicited by Nrf2 might not result from an increase in deacetylase activity. Nrf2 is also acetylated by p300 for activation (37). So, we wondered if Nrf2 competes with FXR for p300 binding. As expected, Nrf2 overexpression increased its association with p300, but prevented FXR interaction with p300 (Fig. 6D, lower). In chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays, Nrf2 promoted FXR binding to the FXRE for SHP gene transcription (Fig. 6E). Moreover, the promoter reporter activity and SHP mRNA transcription were both increased by FXR transfection, to a greater extent by FXR plus Nrf2 transfection, which was completely antagonized by p300 overexpression (Fig. 6F). Collectively, our results demonstrate that Nrf2 has the ability to promote deacetylation of FXR by recruiting p300, which leads to FXR activation through deacetylation.

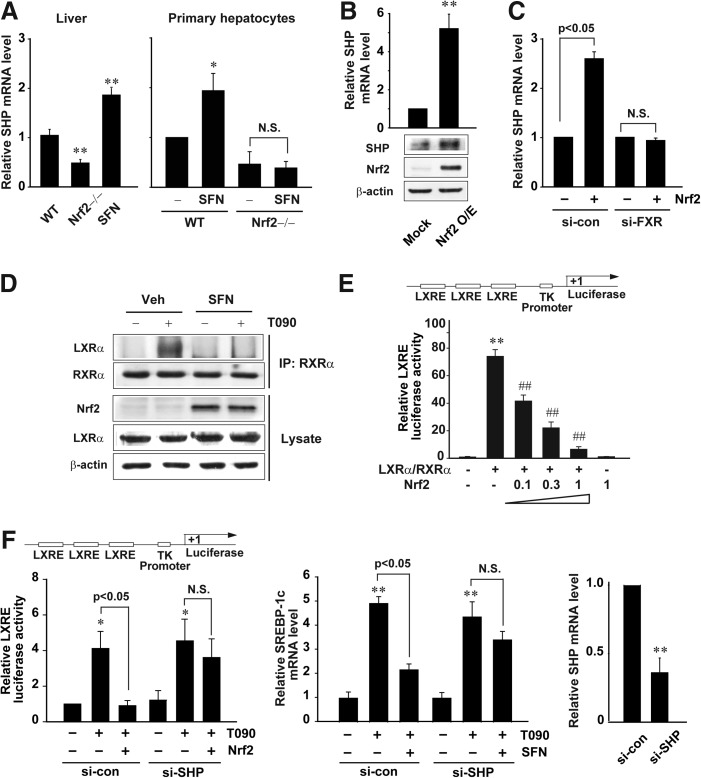

Nrf2 induction of SHP, a negative regulator of LXRα

SHP, a target gene of FXR, negatively regulates transcriptional activity of LXRα (7). So, we next explored the effect of Nrf2 on SHP expression. Nrf2 knockout mice exhibited a decrease in basal SHP transcript level in the liver. Moreover, sulforaphane treatment increased the mRNA level (Fig. 7A, left). Similar results were obtained in the experiments using primary hepatocytes from WT or Nrf2-null mice (Fig. 7A, right). Nrf2 overexpression elevated SHP mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 7B). Consistently, FXR knockdown abolished an increase in SHP mRNA by Nrf2 (Fig. 7C), suggesting that Nrf2 induces SHP via FXR activation.

FIG. 7.

SHP-dependent inhibition of LXRα activation by Nrf2. (A) Real-time PCR assays for SHP mRNA. The mRNA levels were determined on the livers of WT or Nrf2 knockout mice treated with vehicle or SFN (left), or in primary hepatocytes treated with vehicle or 10 μM SFN for 12 h (right). (B) The induction of SHP by Nrf2. SHP mRNA and protein levels were assessed in HepG2 cells transfected with Mock or the plasmid encoding Nrf2 for 24 h. (C) FXR-mediated SHP induction by Nrf2. SHP mRNA levels were measured in cells transfected with Mock or Nrf2 after FXR knockdown. (D) Inhibition of the interaction between LXRα and RXRα by SFN. Cells were treated with 10 μM SFN for 1 h and continuously exposed to T090 for 12 h. (E) LXRE reporter activity. Luciferase activity was measured on the lysates of HepG2 cells transfected with LXRE reporter construct following different transfection combinations with LXRα/RXRα and Nrf2 plasmids for 24 h. The statistical significance of differences between each treatment group and the control (**p<0.01) or LXRα/RXRα (##p<0.01) were determined. (F) Reversal by SHP knockdown of Nrf2's repression of LXRE reporter activity (left) or SREBP-1c mRNA increase (right). Luciferase expression from TK-LXREx3 construct was measured on the lysates of cells treated with T090 for 12 h after transfection with Nrf2 and/or control (nontargeting) or SHP siRNA. SREBP-1c mRNA was assessed by real-time PCR assays. Data represent the mean±S.E. of four separate experiments; the statistical significance of differences between each treatment group and the control (*p<0.05, **p<0.01) were determined.

Next, we determined whether SHP induced by Nrf2 inhibits the interaction between LXRα and RXRα. Nrf2 induction by sulforaphane caused a decrease in the binding of LXRα with RXRα in cells treated with T0901317 (Fig. 7D). Since SHP binds to LXRα and represses the transcription driven by LXRα/RXRα heterodimer, we explored the effect of Nrf2 on the LXRE reporter activity. Transfection with increasing concentrations of Nrf2 plasmid gradually inhibited the LXRE reporter gene induction by LXRα/RXRα (Fig. 7E). SHP knockdown reversed the repression of LXRα-dependent gene transcription by Nrf2 (Fig. 7F, left), corroborating the role of SHP in the inhibition of LXRα. Similarly, SHP knockdown abrogated the inhibitory effect of sulforaphane on the SREBP-1c induction (Fig. 7F, right). Overall, our results indicate that Nrf2′s repression of LXRα-dependent gene transcription may rely on FXR-mediated SHP induction.

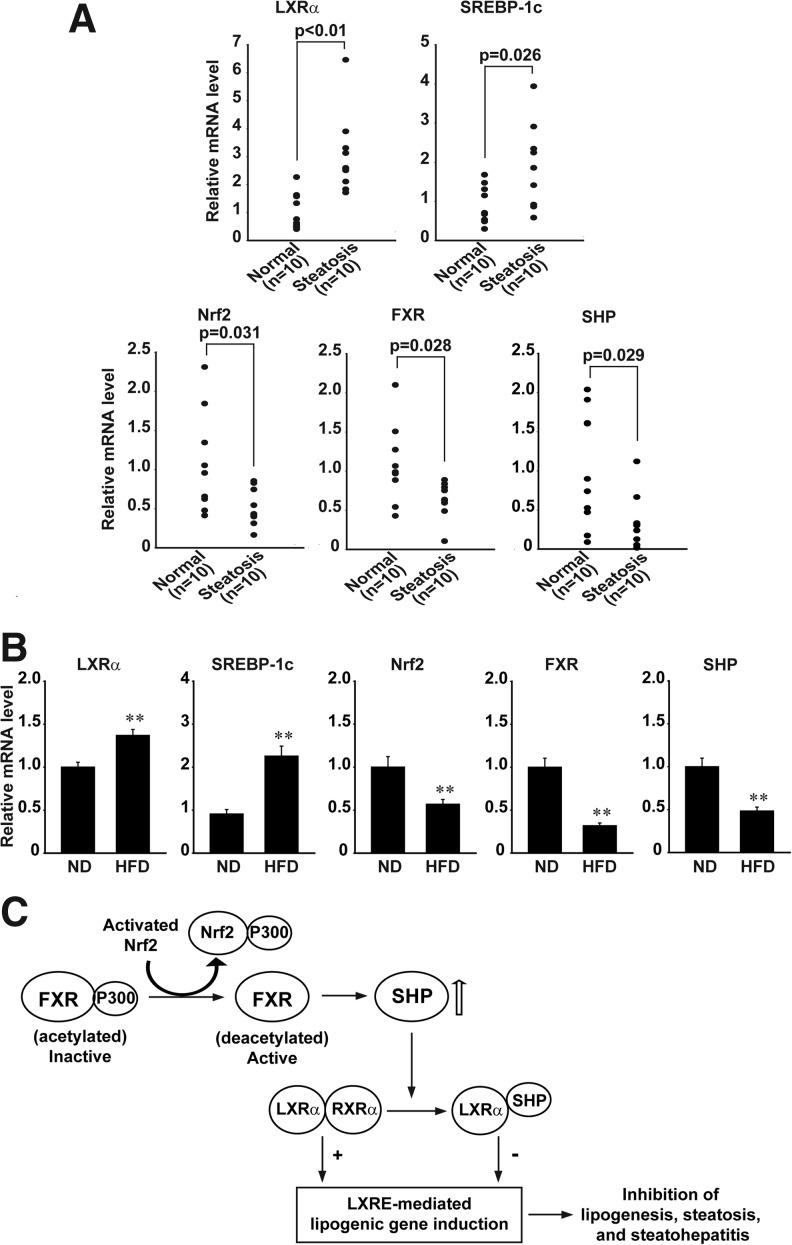

Decreases in Nrf2, FXR, and SHP transcripts in human samples with steatosis

Given the finding that the inhibition of LXRα by Nrf2 results from FXR-mediated SHP induction, we finally compared Nrf2, FXR, and SHP mRNA levels in normal subjects and steatotic patients. The levels of hepatic LXRα and SREBP-1c transcripts were significantly higher in patients with hepatic steatosis than normal individuals (n=10 each) (Fig. 8A, upper). However, those of Nrf2, FXR, and SHP mRNA were all significantly lower in the steatotic samples compared with normal ones (Fig. 8A, lower). No significant statistical differences were found in gender, race, age, BM1, and alcohol intake (Table 1). As expected, the repression of Nrf2, FXR, and SHP was also observed in mice fed on HFD (n=10 each; Fig. 8B). Our results demonstrate that Nrf2 repression as accompanied by decreased expression of FXR and SHP contributes to steatosis in the human liver, supporting the conclusion that Nrf2 negatively regulates hepatic LXRα activity through FXR-mediated SHP induction.

FIG. 8.

Repression of Nrf2, FXR, and SHP by hepatic steatosis. (A) Real-time PCR assays. The mRNA levels were determined on the livers of normal subjects and patients with hepatic steatosis (n=10 each). (B) Nrf2, SHP, and FXR mRNA levels in the liver of mice fed on either a normal diet (ND) or 60% high-fat diet (HFD) for 11 weeks. (C) A scheme illustrating the signaling pathway by which Nrf2 negatively regulates the activity of LXRα in the liver.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics

| Characteristics | Normal (n=10) | Steatosis (n=10) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| male | 4 | 5 |

| female | 4 | 5 |

| unknown | 2 | – |

| Race | ||

| CaucasianAsian | 6 | 8 |

| Asian | – | 1 |

| African-American | 1 | – |

| Unknown | 3 | 1 |

| Age (years) | 53.8±4.9 | 48.5±6.2a |

| BMI | 35.0±0.9b | 28.7±4.0a |

| Alcohol intake | ||

| No | 4 | 8 |

| Yes | – | – |

| unknown | 6 | 2 |

two unknown patients.

six unknown patients.

Discussion

NAFLD has emerged as the most common form of liver disease in association with the increasing incidence of obesity. Hepatic steatosis that results from the overproduction and accumulation of TG can progress to steatohepatitis and more severely to fibrosis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma (4, 10, 13). Despite the high morbidity and potential progression to severe liver disease, the molecular mechanisms underlying NAFLD remain poorly understood. Currently, no other treatment but lifestyle modification is recommended for NAFLD patients. Several transcription factors, including LXRα, SREBP-1c, and FXR, regulate de novo fatty acid synthesis. Especially, LXRα is a key regulator of TG synthesis, not only directly through the transcriptional activation of lipogenic genes (e.g., ACC and FAS), but also indirectly through the insulin-mediated transcription of SREBP-1c (6, 9). Since LXRα is a master regulator of lipid homeostasis, a better knowledge of the components that control the activity of LXRα may lead to development of new therapeutic approaches for NAFLD.

Nrf2 is a key transcription factor that combats cellular oxidative stress. However, whether Nrf2 interferes with hepatic lipotoxicity is still uncertain. Moreover, the molecular mechanism responsible for the regulation of lipid accumulation by Nrf2 remained elusive. Nrf2-null mice exhibited higher lipid accumulation, elevated hepatic fatty acid levels, and oxidative stress after feeding a HFD (38). Also, livers of Nrf2 knockout mice on the methionine- and choline-deficient diets suffered more oxidative stress and heightened inflammation, suggesting that impairment of Nrf2 activity might be a risk factor for NAFLD (8, 36, 43). Although using these animal models is a powerful in vivo approach that mimics metabolic syndromes, the experimental results from them provide no direct evidence about LXRα activity regulation and molecular basis.

Previously, we reported that several Nrf2 activators such as isoliquiritigenin, liquiritigenin, ajoene, and sauchinone inhibit LXRα-mediated lipogenesis (17, 23–25). Treatment with each of these agents decreased HFD-induced body and liver weight gains, fasting blood glucose content, and plasma free fatty acid levels, strengthening the role of Nrf2 in the treatment of hepatic steatosis. In an effort to determine the regulatory effect of Nrf2 on LXRα-mediated steatosis, two different approaches were employed: a) an in vivo model involving mice treated with LXRα agonist, and b) an in vitro model using treatments of LXRα agonists on hepatocytes. Our results demonstrate for the first time that Nrf2 inhibits LXRα activity through SHP induction downstream of FXR activation with deacetylation, and thereby suppresses LXRα-dependent hepatic lipogenesis. Specific activation of LXRα in this event was supported by our results obtained with GW3965 or insulin, as well as by the lack of PXRE or SRE reporter activation by T0901317. In our in vivo model, mice treated with T0901317 showed greater TG accumulation as the dosing frequency was increased. Moreover, exacerbated lipogenesis was apparent in Nrf2-null mice, as indicated by increases in lipid accumulation, hepatic TG, and lipogenic gene induction. In parallel, the levels of plasma TG were elevated due to SREBP-1c upregulation and lipogenic gene induction (40).

The results shown here demonstrate that Nrf2 upregulates FXR, providing the molecular basis for the repression of LXRα activity by Nrf2. The functional role of FXR induction by Nrf2 was verified by our results that FXR knockdown reversed the ability of Nrf2 to repress LXRα-mediated LXRE reporter activity and SREBP-1c induction. Since bile acids are physiological ligands of FXR, FXR activation by bile acids may also be responsible for this effect. In fact, bile acids prevent hepatic TG accumulation by repressing SREBP-1c and its lipogenic target genes (40).

As an effort to elucidate the mechanism(s) of FXR activation, we wondered whether Nrf2 can directly stimulate transcription of the FXR gene via AREs because two putative AREs are present in the proximal promoter region (−1740 ∼ −1731 bp; 5′-TGCAGAGTGC-3′ and −1724 ∼ −1715 bp; 5′-TGTCAGTGCA-3`). The putative ARE sequences have similarity with those of functional AREs in other genes (e.g., phase II enzyme genes). However, enforced expression of Nrf2 failed to enhance FXR luciferase activity that contains −2.0 kb human FXR promoter region, indicating that the putative AREs might be inactive (Supplementary Fig. S1; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertonline.com/ars). Increase in the luciferase activity by HNF4α overexpression confirmed the proper transcription activity of the construct.

In the present study, we observed that the level of acetylated FXR was distinctly high in normal hepatocytes. An important finding of this study is the identification of the ability of Nrf2 to facilitate FXR deacetylation that promotes FXR/RXRα heterodimerization, protein DNA complex formation, and target gene induction (21). Failure of Sirtinol treatment in reversing FXR deacetylation by Nrf2 suggests that this event may be independent of Sirt1 activity. The acetylation of Nrf2 is catalyzed by p300 and CREB-binding protein (37). Our findings demonstrate that Nrf2 binds with p300 in hepatocytes. The inhibitory effect of Nrf2 on FXR acetylation may result from its competition for binding with p300, a protein normally required for the acetylation of FXR (12). In contrast to a decrease in FXR activity by acetylation, the activity of Nrf2 is increased by acetylation (37). Collectively, Nrf2 may make complex formation with p300, thereby dissociating it from an FXR complex (21). This was confirmed by our result of FXRE ChIP assay. The hypothesis was further strengthened by the functional assay showing the ability of p300 to reverse FXR- and/or Nrf2-dependent SHP gene induction.

SHP binds to several nuclear receptors, and this interaction represses their transcriptional activities (2, 7). Specifically, SHP binds LXRα and represses LXRα (or liver receptor homologue-1) (2). SHP also regulates hepatic cholesterol homeostasis by inhibiting the induction of CYP7A (16). Therefore, mutations in the gene lead to early-onset obesity that may cause metabolic disorders (32). FXR upregulates SHP, mainly in the liver (16, 28). Another key finding of our study is that the ability of Nrf2 to inhibit LXRα-dependent transcriptional activity relies on SHP induction by FXR. The important role of SHP in Nrf2′s repression of LXRα was verified by our knockdown experiment. In the gel shift assays, Nrf2 activation by SFN inhibited LXRα/RXRα binding to the LXRE, verifying the repressive effect of SHP on LXRα activity (Supplementary Fig. S2). Identification of the Nrf2–FXR–SHP cascade for LXRα inhibition may explain previous reports linking oxidative stress to lipogenesis and TG accumulation (3, 14). Moreover, this information provides insight into the mechanisms of metabolic conditions and may help find new approaches in treating liver steatosis.

The mitochondrion in hepatocytes is a critical metabolic organelle whose dysfunction may facilitate the pathogenesis of NAFLD. For example, manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD) is a key antioxidant enzyme that converts superoxide radicals in the mitochondrial matrix (34). Therefore, polymorphisms of MnSOD caused less transport of MnSOD to the mitochondria (31), supporting the role of MnSOD in determining susceptibility of steatohepatitis. Moreover, hepatocytes silenced for MnSOD exhibited downregulation of Nrf2 (33), suggesting the link between MnSOD and Nrf2 in patients with steatohepatitis.

Collectively, our results demonstrate that Nrf2 is capable of inhibiting LXRα activity, exerting an anti-lipogenic effect, as mediated by SHP induction as a downstream effect of FXR upregulation. We also report that the transcript levels of hepatic LXRα and SREBP-1c increased by steatosis in humans, inversely correlated with those of Nrf2, FXR and SHP, corroborating our conclusion that Nrf2 inhibits LXRα by inducing FXR and SHP. So, Nrf2 may be a novel target for the prevention and treatment of LXRα-dependent lipogenesis: chemical means of Nrf2 activation have high potential in treating hepatic steatosis and inhibiting lipid-mediated oxidative stress. Also, Nrf2 attenuates inflammatory responses that occur with oxidative stress and tissue injury. Moreover, the induction of antioxidant genes prevents, inhibits, or reverses the process of carcinogenesis and protects cells from chemical challenges (15). All of these additional effects add value to the application of Nrf2 activators for the prevention and/or treatment of LXRα-mediated steatosis. Our findings offer the mechanism to explain how a decrease in Nrf2 activity in hepatic steatosis could promote the progression of NAFLD, providing the potential use of Nrf2 activators for the treatment of NAFLD.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Antibodies directed against Nrf2, RXRα, SHP, p300 and SREBP-1c were supplied by Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Anti-LXRα antibody was purchased from Thermo Scientific Pierce Antibodies (Rockford, IL). Anti-acetyl-Lys antibody was supplied from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA), and anti-FXR antibody was purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit and goat anti-mouse IgGs were obtained from Zymed Laboratories (San Francisco, CA). Anti-β-actin antibody and other reagents were provided from Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Animals

Animal experiments were conducted under the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee at Seoul National University. Nrf2 knockout (Nrf2-/-) mice (19) supplied by RIKEN BioResource Center (Tsukuba, Japan) were bred and maintained. Nrf2 knockout C57/BL6 mice were backcrossed with wild-type (WT) C57/BL6 mice for 6 months, and only male mice were used for experiments. T0901317 (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI) or sulforaphane (LKT laboratories, St. Paul, MN), as dissolved in 10% polyethyleneglycol 400 and 0.5% methylcellulose, was orally administered to mice. Control mice received polyethyleneglycol 400 and methylcellulose only. WT or Nrf2 knockout mice were treated with 50 mg/kg/day T0901317 for 3 times per week (Exp #1) or 7 times per week (Exp #2) for 1 week (n=7, each group). In another set of experiments, mice were exposed to a single dose of 50 mg/kg T0901317 after 90 mg/kg/day sulforaphane treatment for 2 days (n=5, each group). For HFD experiments, the mice were started on either a normal diet (ND) or a HFD (60% of kcal as fat, Product #D12492, Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ) for 11 weeks. Mice were sacrificed 24 h after the last treatment and tissue samples were collected. The animals were fasted for 12 h prior to assays.

Human samples

cDNAs of 20 human liver samples from normal subjects (n=10) or patients with hepatic steatosis (n=10) were supplied from the University of Kansas Liver Center tissue bank (Kansas City, KS).

Oil red O or hematoxylin & eosin stainings

Oil Red O staining was used to visualize neutral triglyceride (TG) and lipids, and hematoxylin & eosin (H&E) staining was used to assess hepatocyte damage. The left lateral lobe of the liver was sliced, and 4-μm sections were cut from frozen optimal-cutting-temperature samples, affixed to microscope slides, and allowed to air-dry overnight at room temperature. The liver sections were stained in fresh Oil red O for 10 min and rinsed in water. For H&E staining, tissue slices were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin for 6 h. Fixed tissue slices were processed and embedded in a paraplast automatic tissue processor, Citadel 2000 (Shandon Scientific, Cheshire, UK). These liver slices were stained with H&E. Hepatic morphology was assessed by light microscopy. A certified pathologist scored samples in a blinded fashion. An arbitrary scope was given to each microscopic field viewed at a magnification of 100X, 200X, or 400X. A minimum of 10 fields was scored per liver slice to obtain the mean value. Extents of central necrosis, central hepatocyte degeneration, midzonal hepatocyte degeneration, peripheral hepatocyte degeneration, and portal inflammation were graded as 0=negative findings; 1=evidence of pathologic changes; 2=mild pathologic changes; 3=moderate pathologic changes; and 4=marked pathologic changes.

Hepatic TG measurement

Samples of mouse liver (0.3 g) were homogenized in 0.1 M Tris–acetate buffer (pH 7.4) containing 0.1 M KCl and 1 mM EDTA. Six volumes of chloroform:methanol (2:1) were then added. After vigorous stirring, the mixtures were incubated on ice for 1 h and then centrifuged at 800 g for 3 min. The resulting lower phase was aspirated. The TG content was determined using Sigma Diagnostic triglyceride reagents.

Blood chemistry

Plasma alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and TG were analyzed using Spectrum, an automatic blood chemistry analyzer (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL).

Real-time PCR assays

Total RNA was extracted using Trizol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and was reverse-transcribed. The resulting cDNA was amplified by PCR. Real-time PCR was performed with the Light Cycler 1.5 (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) using a Light Cycler DNA master SYBR green-I kit. Detailed descriptions of procedures are contained in the Supplementary Methods.

Cell culture

HepG2 cells, a human hepatocyte-derived cell line, were obtained from ATCC (Rockville, MD). Primary hepatocytes were isolated from wild-type or Nrf2-/- male C57/BL6 mice according to a previously published method (20). Livers of mice were perfused with Ca2+-free Hank's balanced saline solution at 37°C for 5 min, and subsequently with 0.05% collagenase buffer (collagenase from Clostridium histolyticum, type IV, Sigma Aldrich) for 20 min at a flow rate of 10 ml/min. After perfusion, the livers were minced gently and suspended with sterilized PBS. The cell suspension was filtered through sterilized gauze and centrifuged at 500 g for 10 min to separate parenchymal and nonparenchymal cells. The pellet was resuspended in PBS and further centrifuged at 50 g for 5 min. Cells were collected from the pellet and cultured on plastic dishes. The cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Invitrogen) containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 50 kU/L penicillin, and 50 mg/L streptomycin at 37°C in humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. The cells were plated at a density of 5×106 cells/10 cm diameter dish and preincubated for 24 h at 37°C. They were then treated with LXRα agonist (T0901317 at least up to 10 μM was nontoxic to hepatocytes).

Transient transfection and reporter gene assays

Cells were plated in six-well plates overnight, serum-starved for 3 h, and transiently transfected with plasmids encoding for Nrf2, LXRα, FXR, p300, or RXRα in the presence of FuGENE HD Reagent (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). Transfected cells were then incubated in Eagle's minimum essential medium containing 1% fetal bovine serum for 18 h. For reporter gene assays, cells were transfected with pGL3-TK-LXRE, pGL3-TK-PXRE, pGL2-FAS-SRE, pGL3-TK-FXRE, pGL3-hFXR, or pGL3-hSHP for 3 h in the presence of FuGENE HD reagent, and the activity of luciferase was measured by adding luciferase assay reagent (Promega, Madison, WI).

In this assay, pGL3-hFXR reporter construct was generated by PCR amplification of the 5′-flanking region of human FXR gene (approx. 2.0 kb) using genomic DNA of HepG2 cells as a template (forward primer 5′-GGGGTACCACAGCTTGTAAGTGGCAGAGCTG-3′; and reverse primer 5′-CCCAAGCTTCCTTGGATTGTTTTGGGTCAGAGAT-3′ containing a KpnI or HindIII restriction site at 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively). The amplified product was digested with KpnI and HindIII, and the DNA was cloned into pGL3 basic vector.

siRNA knockdown

To knockdown SHP or FXR, cells were transfected with siRNA directed against SHP (ON-TARGETplus SMARTpool L-003410-00, Dharmacon Inc., Lafayette, CO), FXR (ON-TARGETplus SMARTpool L-003414-00, Dharmacon Inc.), or a nontargeting control siRNA (100 pmol/ml) using Dharmafect (Dharmacon Inc.).

Measurement of hydrogen peroxide production

DCFH-DA is a cell-permeable nonfluorescent probe that is cleaved by intracellular esterases and turns into a fluorescent dichlorofluorescein upon reaction with H2O2. HepG2 cells were treated with the agent of interest and stained with 10 μmol/L DCFH-DA for 30 min at 37°C. The fluorescence intensity was measured using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ). In each analysis, 10,000 events were recorded.

Immunoblot and immunoprecipitation assays

Immunoblotting and immunoprecipitation procedures are described in the Supplementary Methods.

ChIP assay

Cells were transfected with the plasmid encoding Nrf2 for 24 h, and then formaldehyde was added to the cells to a final concentration of 1% for the cross-linking of chromatin. The chromatin immunoprecipitation assay was performed according to the ChIP assay kit protocol (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY). PCR was performed using the specific primers flanking the FXRE region of the human SHP gene promoter (sense, 5′-TGATAAGGCACTTCCAGGTTG-3′; and antisense, 5′-GCTGCCCCTTATCAGATGACT-3′, 212 bp). An irrelevant region of the gene was PCR-amplified as a negative control (sense, 5′-GACAGGATCTTGCTCTGTTGC-3′; and antisense, 5′- GGGATCATTTGAGGTCAGGAG-3′, 224 bp).

Data analysis

One-way analysis of variance was used to assess significant differences among treatment groups. For each significant effect of treatment, the Newman–Keuls test was used for comparisons of multiple group means. The criterion for statistical significance was set at p<0.05 or 0.01.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations Used

- ACC

acetyl-CoA carboxylase

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- ARE

antioxidant response element

- AST

aspartate aminotransferase

- FAS

fatty acid synthase

- FXR

farnesoid X receptor

- FXRE

FXR response element

- HFD

high fat diet

- LXRα

liver X receptor-α

- LXRE

LXR response elements

- NAFLD

nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- Nrf2

nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor-2

- PXR

pregnane X receptor

- PXRE

PXR response elements

- RXRα

retinoid X receptor-α

- SHP

small heterodimer partner

- SRE

SREBP-1c response elements

- SREBP-1c

sterol regulatory element binding protein-1c

- TG

triglyceride

- WT

wild-type

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MEST) (No. 20100001706). We thank Dr. M. Yamamoto (Tohoku University, Japan) for kind donation of Nrf2 knockout mice and Dr. B. Staels (Institut Pasteur de Lille, France) for generous donation of the pGL3-TK-FXRE plasmid.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Apfel R. Benbrook D. Lernhardt E. Ortiz MA. Salbert G. Pfahl M. A novel orphan receptor specific for a subset of thyroid hormone-responsive elements and its interaction with the retinoid/thyroid hormone receptor subfamily. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:7025–7035. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.10.7025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brendel C. Schoonjans K. Botrugno OA. Treuter E. Auwerx J. The small heterodimer partner interacts with the liver X receptor alpha and represses its transcriptional activity. Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16:2065–2076. doi: 10.1210/me.2001-0194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Browning JD. Horton JD. Molecular mediators of hepatic steatosis and liver injury. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:147–152. doi: 10.1172/JCI22422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carmiel-Haggai M. Cederbaum AI. Nieto N. A high-fat diet leads to the progression of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in obese rats. FASEB J. 2005;19:136–138. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2291fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan K. Han XD. Kan YW. An important function of Nrf2 in combating oxidative stress: Detoxification of acetaminophen. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:4611–4616. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081082098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen G. Liang G. Ou J. Goldstein JL. Brown MS. Central role for liver X receptor in insulin-mediated activation of Srebp-1c transcription and stimulation of fatty acid synthesis in liver. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:11245–11250. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404297101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen W. Owsley E. Yang Y. Stroup D. Chiang JY. Nuclear receptor-mediated repression of human cholesterol 7alpha-hydroxylase gene transcription by bile acids. J Lipid Res. 2001;42:1402–1412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chowdhry S. Nazmy MH. Meakin PJ. Dinkova-Kostova AT. Walsh SV. Tsujita T. Dillon JF. Ashford ML. Hayes JD. Loss of Nrf2 markedly exacerbates nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;48:357–371. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chu K. Miyazaki M. Man WC. Ntambi JM. Stearoyl-coenzyme A desaturase 1 deficiency protects against hypertriglyceridemia and increases plasma high-density lipoprotein cholesterol induced by liver X receptor activation. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:6786–6798. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00077-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Day CP. James OF. Steatohepatitis: A tale of two “hits”? Gastroenterology. 1998;114:842–845. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70599-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeBose-Boyd RA. Ou J. Goldstein JL. Brown MS. Expression of sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1c mRNA in rat hepatoma cells requires endogenous LXR ligands. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:1477–1482. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.4.1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fang S. Tsang S. Jones R. Ponugoti B. Yoon H. Wu SY. Chiang CM. Willson TM. Kemper JK. The p300 acetylase is critical for ligand-activated farnesoid X receptor (FXR) induction of SHP. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:35086–35095. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803531200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farrell GC. Larter CZ. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: From steatosis to cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2006;43:S99–S112. doi: 10.1002/hep.20973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Furukawa S. Fujita T. Shimabukuro M. Iwaki M. Yamada Y. Nakajima Y. Nakayama O. Makishima M. Matsuda M. Shimomura I. Increased oxidative stress in obesity and its impact on metabolic syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1752–1761. doi: 10.1172/JCI21625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garg R. Gupta S. Maru GB. Dietary curcumin modulates transcriptional regulators of phase I and phase II enzymes in benzo[a]pyrene-treated mice: mechanism of its anti-initiating action. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:1022–1032. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goodwin B. Jones SA. Price RR. Watson MA. McKee DD. Moore LB. Galardi C. Wilson JG. Lewis MC. Roth ME. Maloney PR. Willson TM. Kliewer SA. A regulatory cascade of the nuclear receptors FXR, SHP-1, and LRH-1 represses bile acid biosynthesis. Mol Cell. 2000;6:517–526. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00051-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Han CY. Ki SH. Kim YW. Noh K. Lee da Y. Kang B. Ryu JH. Jeon R. Kim EH. Hwang SJ. Kim SG. Ajoene, a stable garlic by-product, inhibits high fat diet-induced hepatic steatosis and oxidative injury through LKB1-dependent AMPK activation. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;14:187–202. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hayashi A. Suzuki H. Itoh K. Yamamoto M. Sugiyama Y. Transcription factor Nrf2 is required for the constitutive and inducible expression of multidrug resistance-associated protein 1 in mouse embryo fibroblasts. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;310:824–829. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.09.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Itoh K. Chiba T. Takahashi S. Ishii T. Igarashi K. Katoh Y. Oyake T. Hayashi N. Satoh K. Hatayama I. Yamamoto M. Nabeshima Y. An Nrf2/small Maf heterodimer mediates the induction of phase II detoxifying enzyme genes through antioxidant response elements. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;236:313–322. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kay HY. Won Yang J. Kim TH. Lee da Y. Kang B. Ryu JH. Jeon R. Kim SG. Ajoene, a stable garlic by-product, has an antioxidant effect through Nrf2-mediated glutamate-cysteine ligase induction in HepG2 cells and primary hepatocytes. J Nutr. 2010;140:1211–1219. doi: 10.3945/jn.110.121277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kemper JK. Xiao Z. Ponugoti B. Miao J. Fang S. Kanamaluru D. Tsang S. Wu SY. Chiang CM. Veenstra TD. FXR acetylation is normally dynamically regulated by p300 and SIRT1 but constitutively elevated in metabolic disease states. Cell Metab. 2009;10:392–404. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim S. Sohn I. Ahn JI. Lee KH. Lee YS. Lee YS. Hepatic gene expression profiles in a long-term high-fat diet-induced obesity mouse model. Gene. 2004;340:99–109. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim YM. Kim TH. Kim YW. Yang YM. Ryu da H. Hwang SJ. Lee JR. Kim SC. Kim SG. Inhibition of liver X receptor-α-dependent hepatic steatosis by isoliquiritigenin, a licorice antioxidant flavonoid, as mediated by JNK1 inhibition. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;49:1722–1734. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim YW. Kim YM. Yang YM. Kay HY. Kim WD. Lee JW. Hwang SJ. Kim SG. Inhibition of LXRα-dependent steatosis and oxidative injury by liquiritigenin, a licorice flavonoid, as mediated with Nrf2 activation. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;14:733–745. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim YW. Kim YM. Yang YM. Kim TH. Hwang SJ. Lee JR. Kim SC. Kim SG. Inhibition of SREBP-1c-mediated hepatic steatosis and oxidative stress by sauchinone, an AMPK-activating lignan in Saururus chinensis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;48:567–578. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lamlé J. Marhenke S. Borlak J. von Wasielewski R. Eriksson CJ. Geffers R. Manns MP. Yamamoto M. Vogel A. Nuclear factor-eythroid 2-related factor 2 prevents alcohol-induced fulminant liver injury. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1159–1168. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee JM. Li J. Johnson DA. Stein TD. Kraft AD. Calkins MJ. Jakel RJ. Johnson JA. Nrf2, a multi-organ protector? FASEB J. 2005;19:1061–1066. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2591hyp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu TT. Makishima M. Repa JJ. Schoonjans K. Kerr TA. Auwerx J. Mangelsdorf DJ. Molecular basis for feedback regulation of bile acid synthesis by nuclear receptors. Mol Cell. 2000;6:507–515. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00050-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maher JM. Dieter MZ. Aleksunes LM. Slitt AL. Guo G. Tanaka Y. Scheffer GL. Chan JY. Manautou JE. Chen Y. Dalton TP. Yamamoto M. Klaassen CD. Oxidative and electrophilic stress induces multidrug resistance-associated protein transporters via the nuclear factor-E2-related factor-2 transcriptional pathway. Hepatology. 2007;46:1597–1610. doi: 10.1002/hep.21831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mitro N. Vargas L. Romeo R. Koder A. Saez E. T0901317 is a potent PXR ligand: Implications for the biology ascribed to LXR. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:1721–1726. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.03.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Namikawa C. Shu-Ping Z. Vyselaar JR. Nozaki Y. Nemoto Y. Ono M. Akisawa N. Saibara T. Hiroi M. Enzan H. Onishi S. Polymorphisms of microsomal triglyceride transfer protein gene and manganese superoxide dismutase gene in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. J Hepatol. 2004;40:781–786. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nishigori H. Tomura H. Tonooka N. Kanamori M. Yamada S. Sho K. Inoue I. Kikuchi N. Onigata K. Kojima I. Kohama T. Yamagata K. Yang Q. Matsuzawa Y. Miki T. Seino S. Kim MY. Choi HS. Lee YK. Moore DD. Takeda J. Mutations in the small heterodimer partner gene are associated with mild obesity in Japanese subjects. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:575–580. doi: 10.1073/pnas.021544398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pardo M. Tirosh O. Protective signalling effect of manganese superoxide dismutase in hypoxia-reoxygenation of hepatocytes. Free Radic Res. 2009;43:1225–1239. doi: 10.3109/10715760903271256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pitkanen S. Robinson BH. Mitochondrial complex I deficiency leads to increased production of superoxide radicals and induction of superoxide dismutase. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:345–351. doi: 10.1172/JCI118798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Repa JJ. Liang G. Ou J. Bashmakov Y. Lobaccaro JM. Shimomura I. Shan B. Brown MS. Goldstein JL. Mangelsdorf DJ. Regulation of mouse sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c gene by oxysterol receptors, LXRalpha and LXRbeta. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2819–2830. doi: 10.1101/gad.844900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sugimoto H. Okada K. Shoda J. Warabi E. Ishige K. Ueda T. Taguchi K. Yanagawa T. Nakahara A. Hyodo I. Ishii T. Yamamoto M. Deletion of nuclear factor-E2-related factor-2 leads to rapid onset and progression of nutritional steatohepatitis in mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2010;298:G283–G294. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00296.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sun Z. Chin YE. Zhang DD. Acetylation of Nrf2 by p300/CBP augments promoter-specific DNA binding of Nrf2 during the antioxidant response. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:2658–2672. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01639-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tanaka Y. Aleksunes LM. Yeager RL. Gyamfi MA. Esterly N. Guo GL. Klaassen CD. NF-E2-related factor 2 inhibits lipid accumulation and oxidative stress in mice fed a high-fat diet. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;325:655–664. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.135822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Videla LA. Rodrigo R. Orellana M. Fernandez V. Tapia G. Quiñones L. Varela N. Contreras J. Lazarte R. Csendes A. Rojas J. Maluenda F. Burdiles P. Diaz JC. Smok G. Thielemann L. Poniachik J. Oxidative stress-related parameters in the liver of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease patients. Clin Sci (Lond) 2004;106:261–268. doi: 10.1042/CS20030285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Watanabe M. Houten SM. Wang L. Moschetta A. Mangelsdorf DJ. Heyman RA. Moore DD. Auwerx J. Bile acids lower triglyceride levels via a pathway involving FXR, SHP, and SREBP-1c. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1408–1418. doi: 10.1172/JCI21025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weerachayaphorn J. Cai SY. Soroka CJ. Boyer JL. Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 is a positive regulator of human bile salt export pump expression. Hepatology. 2009;50:1588–1596. doi: 10.1002/hep.23151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang S. Zhu H. Li Y. Lin H. Gabrielson K. Trush MA. Diehl AM. Mitochondrial adaptations to obesity-related oxidant stress. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2000;378:259–268. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2000.1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang YK. Yeager RL. Tanaka Y. Klaassen CD. Enhanced expression of Nrf2 in mice attenuates the fatty liver produced by a methionine- and choline-deficient diet. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2010;245:326–334. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2010.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.