Abstract

This work aims to provide an overview of producing value‐added products affordably and sustainably from greenhouse gases (GHGs). Methanol (MeOH) is one such product, and is one of the most widely used chemicals, employed as a feedstock for ≈30% of industrial chemicals. The starting materials are analogous to those feeding natural processes: water, CO2, and light. Innovative technologies from this effort have global significance, as they allow GHG recycling, while providing society with a renewable carbon feedstock. Light, in the form of solar energy, assists the production process in some capacity. Various solar strategies of continually increasing technology readiness levels are compared to the commercial MeOH process, which uses a syngas feed derived from natural gas. These strategies include several key technologies, including solar‐thermochemical, photochemical, and photovoltaic–electrochemical. Other solar‐assisted technologies that are not yet commercial‐ready are also discussed. The commercial‐ready technologies are compared using a technoeconomic analysis, and the scalability of solar reactors is also discussed in the context of light‐incorporating catalyst architectures and designs. Finally, how MeOH compares against other prospective products is briefly discussed, as well as the viability of the most promising solar MeOH strategy in an international context.

Keywords: commercial methanol production, solar‐assisted processes, solar methanol, solar reactor design and engineering, technoeconomic analysis

1. Methanol: Then and Now

Methanol (MeOH) has a long and fascinating history. Following its first recorded use in Ancient Egypt for embalming rituals, it remained unisolated in its pure form until the necessary experiments were performed by Sir Robert Boyle in 1661. It was first produced at the industrial scale in 1923 from synthesis gas or “syngas,” a mixture of carbon monoxide (CO) and hydrogen (H2) derived from coal, thanks to the work of Alwin Mittasch and Mathias Pier at BASF.1 These inventors filed the first patent on the synthesis of MeOH from syngas in 1913.1 Today, more than 90 production plants are in operation worldwide, with a combined production capacity of around 110 million metric tonnes per year (MMTA), while providing upward of 90 000 jobs and creating roughly US$55 billion in economic activity.2

Major demands for MeOH originate from its growing use as both a chemical feedstock and a petroleum fuel substitute. As an important feedstock for the chemical industry, it is used in the production of as much as 30% of global industrial chemicals.3, 4 It can be used to produce olefins, formaldehyde, acetic acid, and diverse products such as building materials, pharmaceuticals, resins, adhesives, paints, plastics, and foams.5, 6 The development of renewable, environmentally friendlier fuels is also the focus of many researchers worldwide. As urban populations continue to experience deteriorating air quality, there has been increasing pressure on governments and the transportation sector to find drop‐in, cleaner‐burning fuels to replace fossil fuels. To this end, dimethyl ether (DME) and its less volatile higher homologues, polyoxymethylene dimethyl ethers (PODEs), have attracted increasing attention for their ability to produce less soot when burned in a standard diesel engine. Both of these compounds can be produced, in part, from MeOH. Furthermore, MeOH has been shown to improve internal combustion engine efficiency and performance via its use as a gasoline additive or as a neat fuel.7 As will be shown later, MeOH can be produced as efficiently as DME from “solar‐accessible” syngas, and is more appealing due to its many commercial applications. Furthermore, MeOH can be used in fuel cells as an alternative to H2, due to its higher volumetric energy density, and also serves as a medium for the safe storage of H2 (i.e., as a H2 “shuttle”), since each MeOH molecule can fixate four H atoms. Both of these efforts have resulted in an increased focus on the pursuit for sustainable MeOH.8

The current dominant industrial feedstock for MeOH synthesis is syngas from natural gas (NG) representing 75% of the market (other sources include coal, biomass, and CO2).9 The syngas, besides containing a mixture of CO and H2, also contains a small quantity of added CO2. The original BASF process involved the gas‐phase heterogeneous catalytic conversion of syngas to MeOH at high temperatures and pressures of 360–380 °C and 25–30 MPa, respectively, using a chromium and manganese oxide–based catalyst.10 This process afforded a relatively low yield of just 10 mol% MeOH.10 Today, the preferred catalysts for manufacturing MeOH are mainly copper–zinc oxide hetero‐nanostructures supported on aluminum oxide (CZA); these catalysts function more productively, but are able to do so under much milder conditions of temperature and pressure, typically 200–300 °C and 5–10 MPa, respectively.

The commercial CZA catalyst in use today is the result of six decades of continuous improvement and optimization. Originally patented by John Thomas Gallagher and John Mitchell Kidd of Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI) in 1965,11 the technology was acquired by Johnson Matthey through the purchase of ICI's Synetix catalyst business. Synetix specialized in delivering catalysts to the MeOH, ammonia, oil and gas, chemicals, fine chemicals, and oleochemical industries, among others.12 The original catalyst patent is still the basis of the KATALCO 51‐series catalyst sold by Johnson Matthey today and is the basis of the kinetics model used here to predict the CZA catalyst MeOH productivity from a standard CO‐rich feed (as described in Section 2.3) and from increasingly CO2‐rich feeds (as described in Section 4.3.1). It is envisioned that this catalyst will find continued use due to its low cost, high activity, and stability when used in conjunction with CO‐rich feeds.

Due in part to rising concern about anthropogenic CO2 emissions and the unsustainable sourcing of syngas from NG, there has recently been increasing emphasis on using CO2 and H2O (water) in place of NG as the major feedstocks for MeOH production. This would allow CO2, the most abundant greenhouse gas (GHG), to be recycled into useful chemicals and products, thereby helping to “close” the carbon cycle. Low‐temperature, highly active, economical, and water‐stable catalysts are currently being sought due to the more favorable equilibrium yields with CO2‐rich feeds at low temperatures. Alternatively, harnessing the already productive CZA catalyst by adding a quantity of renewably CO2‐derived CO to the feed could be more economically feasible near term with minimal investment.

Nobel laureate George Olah has been a strong proponent of the vision of the “MeOH economy,”1 which is exemplified in the form of a renewable MeOH production plant in Reykjavik, Iceland (Figure 1 ). This industrial facility commissioned in 2007, and named in his honor, annually produces 4000 metric tonnes of MeOH (MTMeOH) made from CO2 and H2. This corresponds to 5500 MTCO2 recycled per year. The location of the facility allows it to utilize geothermal steam from the 75 MWel (0.18 MTCO2 MWh−1) HS Orka's Svartsengi power station (shown in background of figure) to provide heat (for distillation) and electricity (5 MWel) without burning fossil fuels. It uses ≈10% of the total CO2 emission of the power station. This electricity is used for high pressure (≈3 MPa) alkaline water electrolysis to produce H2, which in turn reduces CO2 to MeOH in the presence of a CZA catalyst, in a process operating at 250 °C and 5–10 MPa.13

Figure 1.

Carbon recycling international CO2‐to‐MeOH plant, Reykjavik, Iceland. (Image courtesy of CRI).

1.1. Solar MeOH

An innovative trend becoming increasingly evident in the scientific literature is the use of light to drive or assist chemical reactions and processes. A solar‐assisted process is defined as one where a portion of the total energy required for the process is replaced by solar energy. The prospect of using solar energy and feedstocks CO2 and water to synthesize MeOH could lead to an economically viable technology capable of replacing the fossil fuel‐heavy industry with a renewably sourced alternative. One prospect is that solar energy could help unlock favorable lower‐temperature equilibrium regimes. Otherwise, it provides a vast source (energy intercepted by the Earth in 1 h > annual world consumption) of clean energy that can be harnessed in various ways to produce light‐assisted chemical products.14

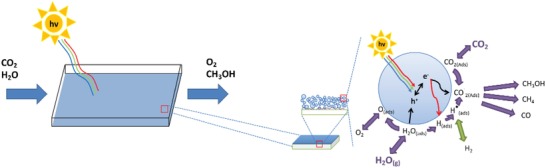

Depicted in Figure 2 are the various current pathways to solar MeOH. Ideally, light can be used directly in the process to convert feedstocks CO2 and water through solar thermochemistry, photochemistry, or photoelectrochemistry. Light energy can also be incorporated indirectly by first converting it to electricity, using photovoltaic (PV) materials, or heat, via photothermal materials; this electricity and heat could then be used to drive CO2 conversion through electrochemistry, photothermochemistry, or traditional thermal catalysts. Direct and indirect biological approaches also exist that could enable the incorporation of light into MeOH synthesis, primarily involving genetically modified organisms and hybrid bioinorganic systems, respectively. However, these remain at the lab scale. Refs. 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20 are recommended for more information. Given the various approaches, the viability of each traditional and solar MeOH technology strategy will be evaluated and compared from a technoeconomic analysis (TEA) perspective. The TEA plant capacities are for a production rate of 1 kgMeOH s−1. Comparison will focus on energy efficiency and process economics performance metrics that are resulting from the activity, selectivity, yield, energy efficiency, scalability, and relative cost of each process. The most promising strategy based on the TEA will also be compared to the traditional commercial‐scale thermochemical (TCST) MeOH synthesis process from an environmental perspective.

Figure 2.

Traditional and solar methanol production technologies. Technologies can be used with feedstocks shown in gray. All technologies discussed in this review are shown, including the applicable feedstocks derived from the raw materials that can be used as feed. The two traditional strategies are for thermochemical conversion of natural gas and biomass to MeOH. The strategies listed as A–F utilize solar energy in some capacity either via solar‐thermochemical, photochemical, photothermal, and photoelectrochemical processes or electricity derived from light, the definitions of which are provided in Section 1.2. The strategies will be expanded upon in Section 1.4.

1.2. Definition of Technologies

In order to improve accessibility to a broad readership, it is helpful here to clarify some commonly used terminology. In this review, we use the following terms to describe the various routes by which feedstocks CO2, water, and light (or NG/biomass and water for the traditional strategies) can be converted into MeOH:

“Thermochemistry” refers to a technology where the primary activation energy to drive the reaction is a result of thermal (heat) energy input into the process. This can also include “solar thermochemistry” in which solar heat is used to provide the heat of reaction for conversion of CO2 and water into syngas.

“Photochemistry” refers to a technology in which light is absorbed by a photocatalyst to generate excited electronic states and activate the desired reaction. In the case of a semiconductor photocatalyst, the incident photon must have energy greater than the bandgap of the material.

“Photothermochemistry” refers to a technology in which absorbed light generates heat (typically generated via nonradiative electronic relaxations) locally on the surface of the catalyst, whereupon the reaction is activated thermally.

“Electrochemistry” or “PV–electrochemistry” refers to a technology where the reactants are activated by the application of an electric field, including one produced by PVs.

“Photoelectrochemistry” refers to a technology whereby an electric field is used to promote charge separation of electrons and holes generated through photochemistry. Again, this electric field could also be sourced from PVs.

1.3. Outline

The remainder of this review covers the present and future of the MeOH industry. It begins by reviewing the TCST MeOH process using a CO‐rich syngas feed made via conventional syngas production methods. Following this section, the prospect of various solar‐assisted MeOH synthesis processes using feedstocks CO2 and water is investigated. The feed gas preparation methods using these raw materials are discussed, including water electrolysis to produce H2, the reverse water‐gas shift (RWGS) for producing CO, and solar‐thermochemical methods for producing CO and H2 from CO2 and water. The principle effects of switching from the commercial feed to one containing greater amounts of CO2 are also explored. In later sections, the state‐of‐the‐art technologies for solar MeOH production, including photochemical, photothermal, PV–electrochemical, and photoelectrochemical (PEC), are presented. These technologies are then evaluated in a comparative TEA in Section 7, which is a system‐level analysis investigating the viability of a commercial‐scale solar MeOH process. Following this, the major challenges associated with scaling up such a solar‐assisted process will be addressed. This includes the design and engineering of both catalysts and solar reactors. Next, the prospect of harnessing existing PV technology to meet the energy needs of thermochemical MeOH processes will be discussed. Finally, a brief comparison of the CO2 utilization to produce MeOH versus DME will be examined, followed by an assessment of the viability of the most promising TEA solar strategy in an international context.

1.4. Definition of Technologies for TEA

The TEA strategies utilize the best available catalysts and technologies for the purposes of comparison. Individual strategies titled as traditional strategy, biomass strategy, and prospective solar strategies A–F are summarized in Table 1 . Strategies A and B adopt a syngas production process for MeOH synthesis, but unlike the TCST process, where syngas is produced through steam methane reforming (SMR), in strategy A, H2 is produced via water electrolysis and CO is produced via RWGS, while in strategy B, syngas is produced by solar‐thermochemically splitting both CO2 and water. In strategies C and D, H2 is produced from water electrolysis and MeOH is synthesized from direct hydrogenation of CO2, through conventional thermochemical and photochemical technologies, respectively. In strategies E and F, CO2 and water are directly converted to MeOH in a single pass, through photochemical and PV–electrochemical technologies, respectively. The six strategies produce solar MeOH from starting feedstocks CO2 and water.

Table 1.

Listing of the technologies used in TEA strategies including the catalyst and feed SN to the MeOH reactor

| Strategya) | Section in this review | Technologies | MeOH catalyst | Feed information to MeOH reactor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional commercial strategy | 2 | TCb) MeOH synthesis, TC syngas from NG | CZA |

Syngas 29.00:2.85:68.15 mol% CO:CO2:H2, SN = 2.05 |

| Traditional biomass strategy | 3 | TC MeOH synthesis, TC syngas from O2 biomass gasifier | CZA |

Syngas 29.00:2.85:68.15 mol% CO:CO2:H2, SN = 2.05 |

| A | 4 | PV–TC MeOH synthesis, PV–ECc) water splitting, solar‐TC RWGS | CZA |

Syngas 29.00:2.85:68.15 mol% CO:CO2:H2, SN = 2.05 |

| B | 4 | PV–TC MeOH synthesis, solar‐TC water splitting, solar‐TC CO2 splitting | CZA |

Syngas 29.00:2.85:68.15 mol% CO:CO2:H2, SN = 2.05 |

| C | 4 | PV–TC MeOH synthesis, PV–EC water splitting | CZA |

CO2 + H2

3.00:22.43:74.57 mol% CO:CO2:H2 in feed, maximum feed CO2 conversion, SN = 2.05 CO produced in situ |

| D | 5 | PCd) MeOH synthesis, PV–EC water splitting, | In2O3− x(OH)y |

CO2 + H2

3.00:22.43:74.57 mol% CO:CO2:H2 in feed, SN = 2.05 CO produced in situ |

| E | 5 | PC MeOH synthesis | Cu@TiO2 |

CO2 + water ≈1:1 CO2:water |

| F | 6 | PV–EC MeOH synthesis | Mo–Bi |

CO2 + water ≈1:6 CO2:water |

| Technoeconomic analysis | 7 | Summary and results for all strategies | ||

All feeds to each strategy are CO2 + water, except traditional case NG (natural gas) or biomass + water

TC, thermochemical

EC, electrochemical

PC, photochemical.

Detailed analysis of each technology is presented in Section 7.

2. The TCST MeOH Process: Traditional Commercial Strategy

In this section, we review the TCST MeOH process that uses a CO‐rich syngas as feed and the commercial CZA catalyst. First, we will discuss the conventional routes to obtain syngas from NG. Thereafter, the thermodynamics followed by the reaction kinetics of the TCST process are discussed. Finally, a brief discussion of the commercial CZA reaction mechanism will follow.

2.1. Conventional Syngas Preparation from NG and Commercial CZA Catalyst Description

The predominant method for current commercial‐scale MeOH production is via thermochemical production from a CO‐rich syngas feed. A typical commercial (empirically optimized) CO‐rich syngas feed composition has a CO:CO2 ratio of about 10:1 and a H2:COx ratio of 2.14. This is on the order of where Klier et al. found their maximum MeOH synthesis rate at 14:1 CO:CO2 and H2:COx of 2.33.21 This is also in the region of maximum MeOH production as shown later in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Ternary diagram for optimal CO:CO2:H2 composition (red ellipse) for the maximum MeOH production at conditions of 5 MPa and 250 °C. The overlayered circles in red, yellow, and green indicate different syngas production technologies that when combined achieve the optimal syngas composition. Adapted with permission.22 Copyright 2017, MDPI.

2.1.1. Production of Syngas Feed from NG

The syngas used in MeOH production is a mixture of CO, CO2, and H2 gases, produced from methane primarily sourced from reforming NG. Its manufacture is a major part of the TCST process and can account for 50–70% of operating costs and 60% of the capital investment.22, 23, 24

Syngas is generally characterized by its stoichiometric number (SN), which is a measure of the reduction potential of the gas mixture. At the commercial scale, an SN of 2.05 has been found to be optimal and maintains the Cu in the CZA catalyst in a redox state.25, 26 The SN is defined in Equation (1)

| (1) |

There are three basic processes for syngas production, shown in Table 2 :

steam methane reforming,

CO2 and methane, or “dry” methane reforming (DMR), and

partial oxidation of methane (POX).

Table 2.

Three processes for the production of syngas from methane

| Process | Reaction | H2/CO ratio | ΔH 1173 K [kJ mol−1] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Steam reforming | CH4 + H2O ⇌ CO + 3H2 | 3:1 | +225.7 |

| Dry reforming | CH4 + CO2 ⇌ 2CO + 2H2 | 1:1 | +258.8 |

| Partial oxidation | CH4 + ½O2 ⇌ CO + 2H2 | 2:1 | −23.1 |

In general, SMR is the most common process of syngas production. DMR is most interesting from a carbon sequestration standpoint as it consumes both GHGs CO2 and methane, and also offers a lower operating cost than SMR and POX. However, since its initial proposal by Fischer and Tropsch in 1928, it has seen limited commercial application as the process suffers from rapid catalyst deactivation through carbon deposition.23, 27 POX is the most promising from an energy efficiency standpoint;23 however, it uses NG exclusively as a carbon feedstock and does not provide the opportunity to valorize any low‐value GHGs like CO2.

So‐called “autothermal” reforming or ATR, takes advantage of the varying heats of reaction for these three processes by combining them into one system in which the exothermicity of the POX process complements the endothermicity of the SMR and DMR processes to create a self‐sustaining reaction system. Typically oxygen (O2) is fed into the upper stage to combust some of the hydrocarbons, and in the lower stage the generated heat is used in a catalytic bed, driving endothermic reactions cooling the reformed gas as it passes through.

Standard commercial syngas production for a process with capacity of 2500–5000 metric tonnes of MeOH per day (MTPDMeOH) usually involves two‐step reforming that consists of an SMR reactor followed by a POX reformer.22 Since SMR typically produces more H2 than desired for a syngas SN of 2.05, a POX reformer is able to compensate as it typically produces syngas with high CO:CO2 ratio, with small amounts of H2.

Some key parameters are shown for different syngas technologies in Figure 3 . The figure shows each technology compared in terms of CO:CO2 ratio, H2:CO ratio, and SN (shown as S module) of the product gas. POX and DMR produce high ratios of CO:CO2, while ATR and DMR produce syngas with a H2:CO ratio near the stoichiometric target of 2:1 H2:CO. Of note, however, is that no single technology produces the optimal SN of 2.05.

Figure 3.

Range of syngas compositions resulting from different reforming technologies. Reproduced with permission.22 Copyright 2017, MDPI.

Figure 4 shows the optimal syngas composition (red ellipse or lighter area of the ternary diagram) to maximize the MeOH yield (mol% at the reactor outlet), for a reaction taking place at 250 °C and 5 MPa with the CZA catalyst.22 As shown, a combination of processes is required, and particular technology adoption is dependent generally on the process economics and local markets.

In terms of process economics, the lowest production cost of MeOH can be achieved by maximizing the process exergetic efficiency (ηexergy), that is, ensuring that the process is maximizing the available energy to do work based on the energy input. As a trade‐off, higher ηexergy often results in higher NG consumption per unit of MeOH produced, also referred to as the “NG intensity.” NG intensity is defined as kgNG,consumed kgMeOH,produced −1.

An analysis by Blumberg et al. indicated that a combined SMR + ATR syngas system gave the best ηexergy of 55.6%, while SMR + DMR and SMR alone produced ηexergy of 41% and 28.2%, respectively.22 The NG intensities of these three processes follow the same trend of 0.81, 0.78, and 0.53 kgNG kgMeOH −1 for SMR + ATR, SMR + DMR, and SMR, respectively. Unfortunately, the most efficient processes correlated with NG consumed, making syngas generation less renewable as efficiency increases.

In another study, Luu et al. proposed a combined DMR + H2 process, in which H2 derived from a renewable source is added to the product of a DMR to achieve the correct SN syngas feed for MeOH synthesis.9 They estimated the NG intensity of SMR to be 22% higher than the Blumberg analysis. By scaling the SMR NG intensity to be equivalent to those used in the Blumberg study, after correction, it is shown that the DMR + H2 process improves the NG intensity to 0.41 kgNG kgMeOH −1 (ηexergy not given although likely comparable to or higher than SMR + DMR). Furthermore, the DMR + H2 process was shown to emit 12.7% less CO2 on average than all other reforming systems considered (DMR, SMR + DMR, SMR, ATR). The emission reduction is less than expected, however, because the more CO2 in the reformer feed, the less calorific value the gas has, requiring more thermal energy input in the form of NG.

The TCST MeOH process has been extensively optimized for production from NG. Another way to quantify how optimized a process is, besides the ηexergy, is via an efficiency measuring the so‐called carbon efficiency (ηcarbon). As the name implies, this efficiency is a measure of how much feed NG carbon ultimately results as carbon in the MeOH product. The current highest ηcarbon uses another type of reforming combination known as gas heating reforming (GHR) and ATR discussed earlier. The GHR uses the hot exhaust gas of the ATR to assist the steam reforming first step lowering its steam requirement and hence the NG intensity.28 Please refer to ref. 7 for a recent discussion of NG reforming technologies. The ηcarbon for this combination is greater than 90%.7

2.1.2. Description of the Commercial CZA catalyst

There are three main components of the commercial CZA catalyst: Cu metal nanoparticles, ZnO nanoparticles, and the bulk alumina support. It consists of a high Cu‐to‐Zn ratio of approximately spherical Cu nanoparticles of a size around 10 nm, and similarly sized ZnO nanoparticles. They are arranged such that ZnO acts as a Cu spacer forming porous aggregates in the activated state.10, 29 Effective interaction of Cu with ZnO is thought to prevent Cu sintering, and maintain Cu/ZnO interfacial strain shown to be correlated with catalytic activity.29 Furthermore, these two components exhibit what is called a strong metal–support interaction (SMSI) through electronic and morphological changes upon reduction. For the former, electrons are transferred from the partially reduced metal oxide support to the metal via the interface, and for the latter the oxide becomes mobile and with an increased wetting affinity migrates over the Cu particles.30 The other supporting material, alumina, is understood to act as a structural promoter.31, 32 The commercial catalyst aggregates expose a large Cu surface area typically 40 m2 g−1.10 Transmission electron microscopy images of this catalyst are shown in Figure 5 .

Figure 5.

Left: Scanning transmission electron microscopy high‐angle annular dark‐field imaging and energy‐dispersive X‐ray spectroscopy. Cu:Zn atomic ratio is 63:37. Average Cu particle size 7.4 ± 2.1 nm. Reproduced under the terms of the Creative Commons 4.0 license.36 Copyright 2016, Springer Nature Publishing AG. Right: High‐resolution transmission electron microscopy images of a Cu/ZnO catalyst obtained from a copper zinc hydroxycarbonate precipitate aged for 120 min. Reproduced with permission.37 Copyright 2005, John Wiley and Sons.

The atomic Cu:Zn ratio (and molar ratio) is generally greater than 2.5:1, with a Süd‐Chemie patented example between 2.8:1 and 3.8:1, as defined in US Patent 4535071.33 A typical unreduced commercial MK‐121 CZA catalyst composition from Haldor Topsøe contains a minimum of 55 wt% CuO, 21–25 wt% ZnO, and 8–10 wt% Al2O3 (Cu:Zn molar ratio of 2.3–2.7).10 A CZA catalyst from the chemical supplier Alfa Aesar contains 63.5 wt% CuO, 25 wt% ZnO, 10 wt% Al2O3, and 1.5 wt% MgO (Cu:Zn molar ratio of 2.6).34 The ICI catalyst, originally developed in the mid‐1960s, is expected to be of similar composition, and as of 2009 contributes to 60% of TCST MeOH production, while other major processes like Lurgi, MGC, and Kellogg make up the bulk of the remainder 27%, 8%, and 3%, respectively.1 The pellet sizes are roughly 5 mm × 5 mm and bulk densities of unreduced catalyst are 1200–1300 kg m−3.10

Commercial CZA catalysts have a productive lifetime of roughly 4–5 years at commercial operating conditions.35 Catalyst deactivation becomes important when a significant amount of water is present in the system typically from higher CO2 in the feed, a topic that will be discussed in Section 4.3.2.

An overview of commercial catalyst compositions, as well as conversion rates and space–time yields (STYs), are shown in Table 3 .10 The last row of the table shows how our model using fresh catalyst (the results of which will be discussed later) compares to other STYs using commercial CZA catalyst systems.

Table 3.

Commercial CZA catalyst compositions and activities (adapted from ref. 10)

| Process | Catalyst composition [wt%] | Conditions: Temperature [°C] Pressure [MPa] Space velocity [h−1] | Rate [kgMeOH kgcat −1 h−1] | STY [kgMeOH Lcat −1 h−1] | Yield MeOH [mol%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shell International Research38 | Cu–Zn–Ma) 40:18:4 |

300 5.3 10 900 |

– | 1.01 | – |

| Ammonia Casale39 | Cu–Zn–Cr–Al 30:50:16:3 |

250 10 12 500 |

– | 1.00 | – |

| Süd‐Chemie AG40 | Cu–Zn–Al 65.2:23.8:11 |

300 10 4000 |

– | 0.82 | – |

| Süd‐Chemie AG41 | Cu–Zn–Al 63:27:10 |

250 6 22 000 |

1.144 | 1.19 | – |

| Lonza AG42 | Cu–Zn–Zr 40:20:40 |

250 5 8000 L kg−1 h−1 |

0.54 | – | 12.7 |

| AIST, RITE43 | Cu–Zn–Al–Zr–Si 45.2:27.1:4.5:22.6:0.6 |

250 5 10 000 |

– | 0.72 | – |

| YYK Corp44 | Cu–Zn–Al 76.3:11:12.7 |

250 5 1.7 g h−1 mol−1 |

1.548 | – | – |

| Kinetics model (this review)45 |

ICI 51‐2 Cu–ZnO–Al2O3 (fresh catalyst) |

250 8 9900 |

2.14 | 2.83 | 33.5 |

M is a metal.

2.2. Thermodynamics of the TCST MeOH Process

In the TCST process, there exist a number of chemical reactions occurring in parallel. While input syngas contains a large portion of CO, MeOH is produced primarily from CO2 in an exothermic reaction (Equation (2))

| (2) |

The water‐gas shift (WGS) reaction also occurs as a side reaction (Equation (3))

| (3) |

The presence of these two reactions results in the overall reaction equation from syngas (Equation (4))

| (4) |

The WGS reaction occurring in parallel sets up a feedback loop wherein water is consumed, producing additional reactants for the MeOH synthesis reactions (Equations (2) and (4)), driving the equilibrium to favor higher MeOH yields.

Thermodynamic equilibrium analysis was conducted using Aspen Plus V9 software, using a Gibbs reactor block with the Peng–Robinson equation of state. The Gibbs reactor considers all possible reactions capable of producing the inputted products (H2, water, CO, CO2, MeOH) from reactants (CO, CO2, H2). The Peng–Robinson property package is applicable to equilibrium systems containing MeOH.46 The equilibrium yield of MeOH is shown in Figure 6 , left, and indicates that it increases with decreasing temperature and increasing pressure. At 200 °C and 8 MPa constant pressure, the yield is 58.8 mol%. When the temperature is increased to 250 °C, the yield decreases to 36.6 mol%.

Figure 6.

Left: Equilibrium yields of MeOH and CO in the standard CO‐rich TCST MeOH synthesis process. Feed syngas utilized was 29:3:68 mol% CO:CO2:H2. CO is consumed by the WGS side reaction. This plot shows that MeOH yield increases with decreasing temperature and increasing pressure. The WGS reaction is more prevalent at lower temperatures and higher pressures. Right: Free energy diagram at various pressures for the main MeOH synthesis reaction and side reactions WGS and RWGS for CO‐rich syngas feed.

Further, the thermodynamic analysis shows that the equilibrium conversion of CO increases with increasing pressure and decreasing temperature, and by being consumed it improves the equilibrium conversion of MeOH. The Gibbs free energy diagram for Equations (2)–(4) is shown in Figure 6, right. It shows that the WGS is favorable at all temperatures up to ≈1000 °C, but becomes less so as T increases; alternatively, the RWGS becomes more favorable as temperature increases. For the main MeOH synthesis reaction (Equation (2)), the Gibbs free energies equate to fractional equilibrium constants, K's, at temperatures above 100 °C.

2.3. Reaction Kinetics of the TCST MeOH Process

The TCST MeOH process using the CZA catalyst has been optimized from over 60 years of process experience. Adding a small quantity of CO2 to the syngas achieves the optimal SN and has been empirically determined to augment the MeOH synthesis reaction (primarily Equation (2)). The reason for this augmentation has been determined experimentally, by noting that as the small quantity of CO2 produces water via MeOH synthesis and RWGS reactions, the water then acts to have an autocatalytic effect on these same reactions and possibly the WGS as well.10, 47 By adding a small amount of CO2 into the syngas feed, the water can be produced in situ.

To illustrate the rates and selectivity of the commercial CZA catalyst using a CO‐rich feed, reaction kinetics modeling was conducted using E‐Z Solve by Intellipro, Inc., a numerical ODE integration software. The model is 1D plug flow, isothermal (250 °C), in the reaction regime (no transport limitations), isobaric (0.8, 3, 5, 8 MPa), with pressure drop neglected and 9900 h−1 contact velocity. The integration method used for the model is backward differentiation formula order 1–5, step size 0.01 g of CZA catalyst up to 1 g basis. This reaction kinetics model adapted from ref. 45 is valid over the experimental range of Klier et al.21 for P CO:P CO2 ratios of 0.5–10. This model was validated against %COx (the sum of CO + CO2 mol%) conversion data from ref. 21 at their maximum experimental conversion at 250 °C, 7.5 MPa, and 28:2:70 mol% CO:CO2:H2.

For synthesis from a CO‐rich syngas, the syngas feed used in the model had a composition of 29.00:2.85:68.15 mol% CO:CO2:H2 (SN = 2.05). This composition also satisfies the additional commercial practice of maintaining a high CO:CO2 ratio to increase the reaction rate and %COx conversion to MeOH.48

The results for the %COx conversion to MeOH (Equations (2) and (4)) and %CO conversion to CO2 (Equation (3)) are shown in Figure 7 . The figure shows there is a synergistic effect of water consumption by the WGS reaction on promoting the total carbon conversion toward MeOH.

Figure 7.

The percent conversion of carbon sources in the system (CO + CO2 or feed %COx) that goes toward both the main MeOH synthesis reactions, and those that go toward the WGS side reaction for the TCST MeOH process from a CO‐rich syngas feed. Each bar represents a pressure starting at 0.8 MPa to 3, 5, and 8 all at 250 °C and SV 9900 h−1. The mol% H2O resulting in the product stream is also shown.

Percent feed %COx conversion becomes as high as 63% at commercial conditions of 8 MPa, 250 °C, CO‐rich feed, and space velocity (SV) of 9900 h−1 (space velocity is discussed further below). This indicates that with significant CO in the feed, at high pressure, the system consumes excess water, driving conversion to ≈92% of the theoretical equilibrium conversion, as per the Le Châtelier principle.

The SV, mentioned earlier, is a parameter that indicates the reactant gas–catalyst contact time in a flow reactor system. It is defined as the flow of feed gas, q (m3 h−1) at standard conditions (STP, 0 °C and 0.1 MPa) per bed volume of catalyst, V cat (m3), calculated using the apparent density of the material. This results in units of inverse time (h−1). In the model, a typical SV of near 10 000 h−1 (9900 h−1) is used, calculated with an apparent catalyst density of 1320 kg m−3 for as‐purchased CZA (Alfa Aesar).

Efficient operation of the TCST process is a balance of a number of parameters. They are yield, water production or consumption, cooling requirements, and throughput. The typical yield of the TCST process is 14–20 mol% MeOH (partially deactivated CZA) usually achieved with a SV near 10 000 h−1. With the high CO content in the commercial feed, the water content in the product gas is limited to ≈0.2 mol% (see Figure 7). Longer contact times generally result in higher %COx conversion and therefore water in the catalyst bed. This higher conversion would be at the expense of catalyst lifetime, due to water‐induced deactivation (to be discussed) as the CO concentration decreases along the bed. Furthermore, a lower yield is chosen in order to maintain manageable cooling requirements due to the exothermicity of both the MeOH (Equation (2)) and WGS (Equation (3)) reactions. Longer contact times also have the effect of reducing reactor throughput, and necessitate the construction of additional reactors to compensate.

2.3.1. Fundamental Reaction Mechanism for MeOH Synthesis on a Commercial CZA Catalyst

To begin, it has been observed experimentally that the carbon atom incorporated into the MeOH molecule can originate from either CO or CO2 depending on the reaction temperature.47 At lower temperatures (below 240 °C), the carbon contained in the MeOH was demonstrated to originate predominantly from CO rather than CO2 via 13C labeling. As the temperature is increased above 240 °C, in the same experiment it was similarly shown that the CO2 carbon becomes the dominant reactant.47 At the commercially relevant temperature of 250 °C, 80% of the carbon in the MeOH produced is from CO2 at 0.6 MPa pressure.47

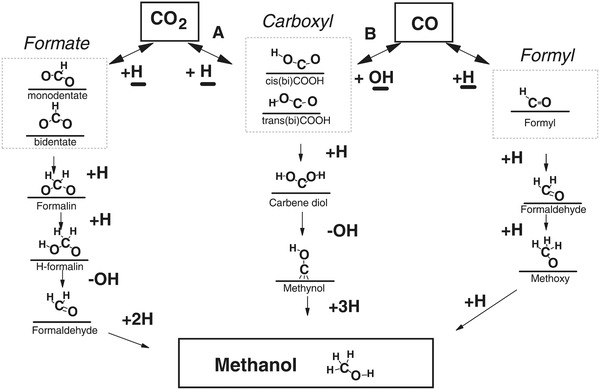

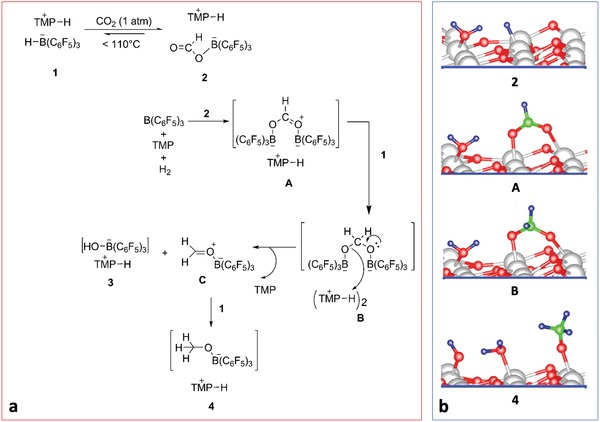

There has been debate in the field over the predominant reaction pathways responsible for MeOH synthesis. A key point of contention is the identity of the main intermediate species. One pathway involves the formation of the formate intermediary at the catalyst surface, whereas the alternative proposal claims a carboxyl intermediate. Both of these pathways will be discussed herein.

The main challenge has been to identify, under realistic temperatures and pressures, which of the possible surface intermediates (carbonyl (CO), formyl (HCO), carboxyl (COOH), or formate (HCOO)) participates in the dominant reaction pathway. This is shown in Figure 8 .

Figure 8.

Possible reaction pathways that a CO2 species can take for conversion to MeOH. Identification of the predominant mechanism remains of considerable debate. Adapted with permission.49 Copyright 2018, Wiley‐VCH.

An additional challenge has been to comprehend the synergistic role of the Cu and metal oxide support in the catalyst, as a result of metal–support interactions. In this regard, a particularly elegant and deeply analytical recent study by Larmier et al. of MeOH synthesis uses ZrO2 supported Cu nanoparticles of around 2 nm in size.50

This study used a combination of in situ Fourier‐transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) and ex situ magic‐angle spinning NMR together with 2D and 13C isotope labeling to show that hydrogenation of the surface reaction intermediate, formate, was the dominant reaction pathway. Their experimental findings were corroborated through the use of density functional theory (DFT) computational modeling.

DFT calculations on this system have concluded that a metal–support interaction occurs via charge transfer from the Cu nanoparticles to CO2 adsorbed on the ZrO2 (opposite charge direction to the partially reduced metal oxide SMSI mentioned earlier). This accumulation of negative charge on the C of surface‐bound CO2 activates the CO2 on the surface of the ZrO2 toward reaction with H species that have spilled over onto the ZrO2 support from dissociation of H2 on the Cu surface. This reaction results in a surface‐bound formate species, thought to be located at the interface between the Cu and ZrO2.50

The favored reaction scheme is depicted in Figure 9 , for the transformation of this surface‐bound formate intermediate to a surface methoxy, determined from combined IR–NMR spectroscopic measurements. Through use of kinetic isotope labeling, an interpretation of the isotope labeling results indicates that the observed H–D exchange of the formate C—H bond to form DCOO is faster than its hydrogenation to surface methoxide (OCHD2), verifying the DFT prediction.

Figure 9.

Proposed reaction mechanism determined via DFT modeling for MeOH synthesis from syngas, on a Cu/ZrO2 catalyst. Reproduced with permission.50 Copyright 2017, John Wiley and Sons.

To complement, the DFT calculations showed that there exists a small activation energy barrier for interconversion between formate and acetal species, implying they exist in equilibrium, thereby enabling the observed H–D exchange of D2 with the HCOO intermediate. The reaction of the acetal that follows involves a concerted transfer of H from the Cu to the acetal C, which results in the formation of surface methoxy and hydroxyl groups. They can react further with H spilled over from the Cu to form MeOH and water that desorb from the ZrO2 to complete the catalytic cycle, with desorption energies determined through DFT modeling.

Conversely, there are recent studies that suggest an alternative to the formate pathway. Yang et al.47 attempted to titrate surface formate species on Cu and on supported Cu/SiO2 present under reaction conditions (0.6 MPa, <200 °C) with H2, but failed to produce MeOH, possibly ruling out a hydrogenation pathway via formate in the synthesis mechanism. However, they remarked that this pathway may be more favorable at higher surface coverages of formate (e.g., through use of higher P).

The times to initiate the reaction, or the induction times, of both MeOH synthesis and RWGS reactions were found in this study to be influenced by the amount of water in the feed.47 However, the presence of water did not affect the formate coverage, indicating that this species is likely a spectator decoupled from the two main reaction paths, a conclusion of ref. 51 also for an industrially relevant CZA catalyst. This suggests that water did not have an autocatalytic effect on a hypothetical active formate intermediate.

Based on the Yang et al.'s study, water is thought to contribute to the creation of active intermediates that may function catalytically with regard to the hydrogenation steps in both CO and CO2.47 The above assumption suggests a common intermediate in both the MeOH synthesis and RWGS reactions. A carboxyl intermediate instead of the usual formate (for CO2) and formyl (for CO) is thought to answer the question related to the influence of water on the induction time.

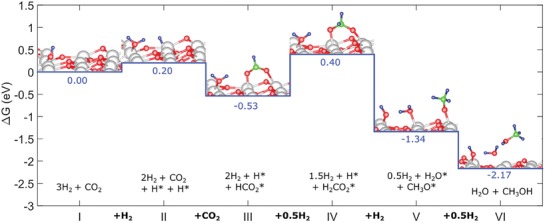

They continued investigating using DFT studies, showing that the presence of water was found to greatly assist the hydrogenation of CO2 to form carboxyl species. The hydrogenation barrier was 1.08 eV for the carboxyl pathway versus 1.8 eV for the formate pathway with water. The effect of water was hypothesized to assist the CO hydrogenation, as the OH groups from the water are necessary to form the carboxyl intermediate. Corroborating DFT data failed to find a water‐assisted step for the reaction pathway involving a formate intermediate, further supporting the evidence of a water‐assisted shared carboxyl intermediate species in the reaction pathway. Although the carboxyl intermediate species had not yet been observed experimentally, there is growing evidence for this water‐assisted intermediate that is shared between the CO and CO2 reaction pathways. The mechanistic details are illustrated in Figure 10 .

Figure 10.

Postulated reaction mechanisms for MeOH synthesis from a CO and CO2 syngas on a Cu/SiO2 catalyst. Reproduced with permission.47 Copyright 2013, Elsevier.

Recently, a study by Chernyshova et al. using surface‐enhanced Raman spectroscopy identified that CO2 activates as a carboxyl intermediate on a 0.5 mm thick Cu foil surface.52 This was confirmed by DFT simulations. This evidence of a carboxyl species lends credence to Yang et al.'s proposed mechanism of a dual pathway consisting of both formate and carboxyl intermediates. This result also implies a direction of electron charge transfer via SMSI from a partially reduced metal oxide to activating CO2 on Cu particles.30 H2 for hydrogenation of CO2 can originate from spillover of H+ from ZnO,53, 54 as it was found through experimental observation that absorbed H coverage on metallic Cu hinders more dissociative H2 adsorption, but not CO2.55 Oxidized Cu has been found to provide more H spillover to ZnO than metallic Cu (where C oxygenates are proposed to reside) lending empirical understanding of the redox SN of the syngas.54

3. Thermochemical MeOH Production from Biomass: Traditional Biomass Strategy

The modern production of syngas from gasified biomass remains the sole means of commercial‐scale MeOH production that incorporates both sunlight and biological processes, with overall biomass‐to‐MeOH mass conversions reaching as high as 45%.56 Though respectable, this represents only about one‐fourth of the mass conversion expected when producing MeOH from NG (based on stoichiometric calculation and assuming a methane‐to‐MeOH ηcarbon of 90%). The term “biomass” refers to any carbonaceous plant or animal material, including that derived from wood, agricultural crops, municipal and animal waste, aquatic plants, and algae.1 While conversion of biomass to fuel is theoretically carbon‐neutral, it is not highly efficient in terms of the amount of initially captured solar energy that remains available in the final chemical product. Losses occur at several steps of the process, including those due to low photosynthetic efficiency (1–2% for plants57 and up to 3% for microalgae,58 as opposed to up to 13% for hybrid systems consisting of microorganisms coupled to PVs59), biomass processing, and fermentation steps. Depending on the source of material, large‐scale production of biomass may also compete with the availability of arable land for food production.

3.1. Syngas Production from Biomass

Using a thermochemical process called “gasification,” biomass can be converted into syngas, which is in turn used in catalytic MeOH synthesis. As a result, the combination of these two processes can be considered an applicable use of solar energy in MeOH production.

The gasification of biomass may be accomplished via single‐step or two‐step processes. In both cases, the biomass is first dried to reduce its moisture content to between 15 and 20 wt%.1 In a one‐step process, the dry biomass is pressurized in an O2/water mixture and then partially combusted to provide the heating required to drive the reaction.1 While such a simple process is very appealing, a more involved, two‐step process typically achieves more complete conversion to products.1 In the first of the two steps, the biomass is pyrolyzed at between 400 and 600 °C in an O2‐deficient atmosphere to form both charcoal (weighing 10–25% of the initial mass) and a gaseous mixture of small molecules that includes H2, methane, water, CO, CO2, and volatile tars.1 The charcoal product is then gasified at 1300–1500 °C in a process called “char conversion,” effecting its conversion into CO.1 For both of these processes, the major disadvantage and challenge facing the gasification of biomass is the proper recovery of heavier tar compounds that can condense and clog various components of the chemical reactor; proper planning and control of reaction conditions are required in order to avoid production of these compounds.1

While all biomass is capable of being gasified, not all sources achieve the same biomass production rates or final conversion to MeOH.1 Although industrial facilities have been proposed for the production of biomass using algae,60 their high water content makes them less appealing for gasification.1 These organisms also tend to be rich in oils that are better suited for conversion into biodiesel,61 and so less effort has been directed toward their use in MeOH production.1 As is reflected by their prevalence in the literature, dry wood and stalk plants (switchgrass, rice, corn straw, etc.) are typically better suited to gasification and subsequent incorporation into the process.56, 62, 63 Crops such as switchgrass are also an attractive option for generating biomass in countries with arable land, but run the risk of competing with food crops for land use.1 As such, the farming of fast‐growing trees is a promising approach to biomass generation for subsequent gasification; however, there is considerable variability in the growth of different sources of biomass, with each MTdry wood biomass requiring 0.025–0.1 hectares of land (250–1000 m2).1 To feed a hypothetical 24 MTPDMeOH reactor for an entire year would require ≈48 MTbiomass to be processed, necessitating the farming of ≈220–880 hectares of land.1 On a commercial scale, syngas production from biomass is impaired by its relatively low energy density (in terms of the products it generates), making its harvesting and transport over long distances less economical.1 The development of novel technologies such as “fast pyrolysis,” which can convert biomass into a higher‐density “biocrude” oil prior to transport, could help offset this disadvantage, but will require significant further research in order to transition from the laboratory to the commercial scale.64 The bioliq process spearheaded by the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology in partnership with company Air Liquide was fully commissioned in 2013. The process concentrates dry biomass by converting it into a “biosyncrude,” increasing its energy density by an order of magnitude (≈2 to ≈25 GJ m−3). The biosyncrude is collected and transported to a centralized facility that then converts it into diesel and gasoline‐type fuels (≈36 GJ m−3). This is another route to liquid chemicals being pursued in Germany.65, 66

The syngas produced from biomass is similar to that obtained from NG in that both typically have low concentrations of impurities (such as sulfur and heavy metals) relative to syngas derived from coal.1 As mentioned previously, an SN slightly greater than 2 is optimal for the production of MeOH from syngas, which is greater than the ratio of that obtained from biomass.56 The value of SN can be increased through either the addition of H2 (which can also be derived from biomass via fermentation and other reactions)67, 68, 69 or the utilization of the WGS to convert some of the excess water to H2.56

Methods of using solar energy for the gasification of biomass have also been proposed, further contributing to the coupling of solar energy with MeOH production.70 In this process, biomass is heated either directly, through the use of a transparent (e.g., quartz) reactor, or indirectly, by heat transfer through the exterior walls of an opaque reactor.70 Each approach offers advantages and disadvantages: a transparent reactor must be diligently cleaned to enable the transmission of light, whereas an opaque reactor must contend with limitations of heat transfer from the exterior of the reactor to the biomass inside.70 Using solar concentrators in conjunction with complementary focusing elements intensifies the sunlight incident on the biomass gasification reactor. The temperatures thereby achieved should be sufficient to effect biomass gasification (i.e., up to 850 °C) without the need for external heating.70 It is proposed that 3 MW of solar energy would need to be harnessed by the solar concentrators in order to process 24 MTPDbiomass of dry (i.e., 15–20 wt% moisture) pulverized biomass.70 Assuming a near‐equatorial location and full utilization of the available solar spectrum,71 this would require (at first approximation) a minimum area of ≈1.7 hectares, corresponding to a 146 m diameter circular array of solar concentrators.

In recent years, systems have also been designed in which biomass is further converted from syngas to MeOH, within the same facility.60, 62, 72, 73 The theoretical maximum energy efficiency of photosynthesis (light to biomass) is estimated to be 4.6–6.0%.57 Here a 5% photosynthetic efficiency is assumed. It should be noted, however, that syngas produced via the gasification of biomass is significantly enriched in CO2, relative to the optimal CO:CO2:H2 compositions used in the TCST process. This discrepancy can be quite large, with CO:CO2:H2 compositions of ≈20:30:50 mol% (SN of 0.4) being produced from a variety of waste biomass from various grasses, trees, and crops.72

Thus, syngas produced from biomass contains excess CO2 and insufficient H2. Fortunately, the relative ratios of the three constituent gases can be modified to more closely match those of the ideal feed case via various processes; these include the removal of excess CO2 using membranes or amine scrubbing, conversion of excess CO2 to CO using the RWGS reaction, and addition of H2 produced by other processes.60, 62, 72 In order to achieve maximum yields, such an approach was used in the “traditional biomass strategy” discussed in this section, wherein removal of excess CO2 was used to obtain an optimal syngas composition for MeOH production.72 These extra steps do contribute to the energetic and capital costs of the overall synthesis process, however, and would ideally be avoided, thereby allowing CO2‐rich syngas (such as that produced via biomass gasification) to be used directly and without further modification. For this reason, there exists considerable interest in incorporating such syngas into more traditional MeOH production systems.

4. Thermochemical MeOH Production Using a CO2‐Rich Feed: Strategies A–C

Incorporation of more CO2 into the thermochemical process and other useful chemical processes using novel catalysts or process designs is an aspirational goal, to close the carbon cycle in which fuels are recycled from the atmosphere instead of derived from nonrenewable fossil resources. However, replacing CO in the thermochemical process syngas feed with CO2 has implications for the TCST process. In this section, we review the less conventional routes to obtaining syngas from CO2 and water, which feeds a thermochemical MeOH synthesis process using the commercial CZA catalyst. First, we will introduce light‐assisted syngas production technologies (RWGS, water electrolysis, photoelectrochemical water electrolysis, and solar‐thermal), and discuss the fundamental basis and materials underlying the processes (photothermal, electrochemical, photochemical, and solar‐thermochemical). We will then discuss the thermodynamic and reaction kinetic consequences of increasing the CO2 feed concentration on the thermochemical process. Thereafter, the effects of increased water production (due to CO2‐rich feed) and the advantages of tuning selectivity for a solar‐assisted reaction will be discussed. Finally, a description of a novel type of low‐temperature thermochemical catalyst will be discussed.

4.1. Solar‐Assisted Syngas Production: From CO2 and Water to CO and H2

4.1.1. Photothermal CO Production via the RWGS Reaction: Utilized in Strategy A

Syngas is the main feedstock for current MeOH production, and CO represents a major component thereof. Due to the high cost of building and operating the syngas producing process in the TCST process, it is worthwhile exploring various technologies that could supplant this step for less overall capital expenditure and operating costs. The RWGS reaction is a key candidate for making solar syngas to valorize CO2.

The RWGS reaction was first observed by Carl Bosch and Wilhelm Wild in 1914, when they attempted to produce H2 from steam and CO on an iron oxide catalyst.74 It is currently utilized at the pilot plant scale in the production of syngas for producing “blue crude,” a CO2‐derived crude oil similar to fossil crude oil in carmaker Audi's e‐diesel process.75

The RWGS reaction is equilibrium limited and favored at high temperatures, due to the endothermic nature of the reaction. Thermodynamic evaluations at atmospheric pressure showed that CO2 conversion is enhanced when excess H2 is added (92% versus 62% CO2 conversion for 3:1 H2:CO2 versus 1:1 at 1200 °C) and the reactor temperature is high.76 The equilibrium concentrations for 1:1 H2:CO2 and 3:1 H2:CO2 on a dry basis (product water removed) are shown in Figure 11 .

Figure 11.

RWGS equilibrium product syngas composition on a dry basis (Aspen Plus V9) at two different feed compositions and varying temperature

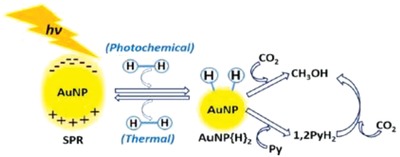

It is possible to drive traditional thermochemical reactions with solar energy through the use of photothermal catalysts. In photothermally catalyzed reactions, incident photons are absorbed by the photocatalyst and converted to heat. This results in a temperature spike localized to the catalytic sites on the surface of the catalyst. The generation of high local temperatures at the surface of the catalyst can result from localized surface plasmons, recombining electron/hole pairs, and relaxing interband and/or intraband transitions. Nanoscale thermal transport also plays an important role in either localizing or distributing the generated heat to catalytic sites and/or nanoscale thermal transport effects.

The extent of the photothermal effect depends on the structure and composition of the photothermal catalysts. A composite material hybrid configuration offers several advantages by drawing on the electronic, optical, catalytic, structural, and chemical properties of two materials, rather than one. Generally, a strongly absorbing material is coupled with a (photo)catalyst. Both of these materials can act as either the catalyst or the catalyst support. An ideal photothermal catalyst should be a strong light absorber across the whole spectral range from ultraviolet to infrared. At the same time, it should efficiently convert this radiation into thermal energy and catalyze the desired surface reaction at high rate and selectivity for the desired product.

When a photothermal catalyst absorbs light, a local temperature spike is observed. Hence, the temperature experienced at the active site increases, which leads to increased reaction rates. At the same time, photochemical surface reactions are initiated as a result of illumination of the catalyst.

The synergistic effects of photo‐ and thermochemical processes experienced during photothermal catalysis can lead to increased rates of reaction, thereby contributing to enabling higher CO2 conversion, and lower demand for high‐grade, high‐temperature heat.

Photothermal RWGS catalysts oftentimes consist of metal or metal oxide catalysts, which exhibit strong optical absorption across the full spectral range, and semiconductor supports. The metal/metal oxide catalysts have a dual purpose: they act as efficient light absorbers, and at the same time catalyze the reaction. The semiconductor support can also act as light absorber, or it can provide active surface sites for the adsorption of reactants and reaction intermediates. Metals such as Fe,77, 78 Co,78 Pd,78, 79, 80, 81 Ni,78, 82 and Rh83 have been reported as efficient photothermal catalysts for the RWGS reaction. Supports, which have been studied, include Al2O3,78 Nb2O5,80, 84 Si nanowires,85 TiO2,78 and WO3.79 Photothermal RWGS over the aforementioned photochemical catalyst In2O3− x(OH)y deposited on Si nanowires will be discussed in more detail. To expand, In2O3− x(OH)y has been discovered recently to efficiently photocatalyze the RWGS reaction.86, 87, 88, 89 The optical bandgap of In2O3− x(OH)y is 2.9 eV.86 It has been shown through a combination of experimental and theoretical work that the absorption of ultraviolet and visible radiation with an energy above the optical bandgap of In2O3− x(OH)y elevates the photocatalyst into an excited state. This causes a reduction in kinetic barriers for the RWGS reaction, which manifests itself in higher observed catalytic rates.87, 90 Appreciable rates in the range of µmol CO gcat −1 h−1 have been observed only when the photocatalyst temperature is elevated to above 100 °C. Experimentally, temperature elevation is achieved through bringing the reactor to the desired temperature through auxiliary heating. The desired working temperature can also be achieved through dispersing the In2O3− x(OH)y catalyst on Si nanowires. The Si nanowires efficiently absorb broadband light across the whole spectral range, which causes temperature elevation. Hence, the temperature needed to achieve appreciable rates can be achieved through light‐induced heating of the Si nanowire support, as illustrated in Figure 12 .85 This photothermal effect increases the efficiency of the light‐induced RWGS catalytic reaction.

Figure 12.

Schematic representation of photothermal catalysis using In2O3− x(OH)y photocatalyst supported on Si nanowires. The yellow shading represents the photons of energy greater than the bandgap of In2O3− x(OH)y photocatalyst. The red shading represents the photons of energy below the bandgap of In2O3− x(OH)y. Photons of energy above the bandgap of the In2O3− x(OH)y are absorbed and generate electron/hole pairs, while the photons of energy below the bandgap of In2O3− x(OH)y are absorbed by the Si nanowire support to generate heat. Reproduced with permission.85 Copyright 2016, American Chemical Society.

The yellow and red shading in the figure illustrates the different light harvesting processes for photons with energy greater and less than the bandgap of In2O3− x(OH)y, respectively. The yellow shading is the creation of an electron–hole pair within the nanocrystals and enables the solar‐powered RWGS reaction, whereas the red‐shaded components are absorbed and, via the photothermal effect, converted into heat within the SiNW support. These studies showed that the hybrid In2O3− x(OH)y@SiNW made more efficient use of the solar spectrum than In2O3− x(OH)y alone. Collectively these effects enhanced the photocatalytic reduction rate of CO2 relative to nonuniform coatings and unsupported In2O3− x(OH)y.

The champion photothermal RWGS rate of 18.8 mol CO gcat −1 h−1 has been achieved using Pd‐decorated Nb2O5 catalysts.84 In this study, a library of Pd@Nb2O5 catalysts of various Pd loadings was prepared. The selectivity between the CO RWGS reaction and the CH4 Sabatier reaction can be tuned by varying the Pd loading between 0.1 and 15 wt% Pd. At low Pd loading of 0.1 wt%, the RWGS is catalyzed at a rate as high as 18.8 mol CO gcat −1 h−1 and at selectivity of greater than 99%. If the loading is increased, the selectivity shifts toward CH4 formation. At a Pd loading of 10 wt%, CH4 is formed at a rate of 0.11 mol gcat −1 h−1 and at a selectivity of 13%. This effect has been rationalized through a combination of electronic and size effects. As the loading increases, the average Pd nanoparticle size increases. This effects stronger electronic interaction between the Pd nanocrystals and the Nb2O5 support, which causes the Pd nanocrystal surface to be more positively charged than for smaller Pd nanocrystals (lower loadings). The binding energy between CO and Pd increases for a larger Pd particle size, which causes the CO molecule to be more strongly adsorbed to the Pd surface. It is hence further reduced to CH4.84

Photothermal catalysis is still in its relative infancy. Considerable research and development efforts are still necessary to generate knowledge about the relationships between catalyst composition, size, shape, electronic structure and support with the observed catalytic rates, product selectivity, photon utilization, thermal transport properties, and quantum yield. Additional difficulties arise to accurately measure the local temperature of the catalytic sites, due to various parameters that govern the temperature evolution and distribution within the catalyst bed, including photon penetration, thermal properties of the gas and catalyst, and the thermal energy released or consumed by the chemical reaction (heat is consumed (endothermic) or produced (exothermic) during reactions, respectively, which can influence the local temperature at the active site). Integrating photothermal heterogeneous catalysts successfully into photoreactors will require further research, enabling photons to be efficiently brought into contact with photothermal catalysts while minimizing heat losses.

It should be noted (as will be discussed in Section 4.2) that direct hydrogenation of CO2 is thermodynamically less favorable as compared to CO‐rich syngas hydrogenation. The incorporation of a separate RWGS reaction step into the process furthermore represents an additional reaction step including reactor and peripheral components, which requires higher investment cost than direct CO2 hydrogenation.

However, the so‐called “CAMERE” (CO2 hydrogenation to form MeOH via RWGS reaction) process revealed a relative 20% higher yield when CO2 was converted to CO (through RWGS) in a first step, due to the CO feedback effect resulting in improved yields.25 Hence, the integration of the RWGS reaction step producing even moderate quantities of CO is beneficial to improve the CO2‐to‐MeOH product yield.

High CO2 conversion using the RWGS reaction can be achieved at high temperatures, higher than 500 °C. Process waste heat of such high temperature is generally not readily available in common commercial processes (the temperature level of the MeOH synthesis reaction is 250 °C).

The are other strategies being explored to reduce the energy demand of the RWGS reaction step. One such approach is the so‐called sorbent‐enhanced RWGS (SERWGS), a process in which a sorbent is added that can selectively remove water from the reactor. This drives the equilibrium toward CO production, and as high as 100% CO can be achieved at temperatures as low as 250 °C.91 It is certain that redundancy is needed due to sorbing/desorbing alternation required for this type of a system. Notwithstanding, the authors estimated that with a SERWGS efficiency of 90%, a high‐pressure water electrolysis step supplying H2 efficiency of 85% and a PV efficiency of 19%, a solar energy to liquid fuel efficiency of 8.2% is possible. With a CO2 capture energy penalty of 150 kJ mol−1, the efficiency becomes 7.7%.

4.1.2. Water Electrolysis: Utilized in Strategies A, C, and D

Investigations of MeOH synthesis from CO2 and H2 are much more common that direct use of water as the H2 source. However, this approach requires one to consider the source of H2 gas. Currently, most H2 gas is produced by SMR discussed earlier. While this process can be combined with recycled CO2, it is counterproductive in terms of GHG emissions, as the H2 is primarily fossil‐derived. Therefore, the ideal solar synthesis process should incorporate the use of renewable H2 through electrolysis, whereby water is dissociated into H2 and O2 using electrical energy (Equation (5))

| (5) |

Of course, using this pathway to produce MeOH is not without its own challenges. While the overall reaction of CO2 and water to MeOH is endothermic, the synthesis reaction from CO2 and H2 is exothermic. Therefore, the electrolysis reaction takes over for steam reforming as the most energetically intensive part of the overall process. The working principles and state of the art of the various types of electrolysis have been reported in refs. 92, 93, 94.

The respective half reactions occurring during the evolution of H2 and O2 are listed in Equations (6) and (7)

Oxygen evolution reaction (OER)—acidic conditions

| (6) |

H2 evolution reaction (HER)—acidic conditions

| (7) |

where the standard reduction potentials are with respect to the reversible H2 electrode. The above reactions assume acidic conditions; under basic conditions, the half reactions are listed in Equations (8) and (9).

OER—basic conditions

| (8) |

HER—basic conditions

| (9) |

4.1.3. Solar‐Assisted Water Electrolysis for the Production of H2 Gas

Here we present a brief summary of light‐assisted or photoelectrochemical water electrolysis processes forming H2.

Photoelectrochemical Water Electrolysis: PEC water electrolysis has been a popular research topic since Honda and Fujishima demonstrated the reaction over TiO2 in 1972.95 Since then, the mechanisms of the process have been investigated thoroughly.

Semiconductors used to collect light and drive the OER/HER (Equations (6)–(9)) must have valence and conduction band edges that correctly align with the half‐reaction potentials. That is, the conduction band edge of the semiconductor should be more positive than the potential of the OER, and/or the valence band edge must be more negative than the reduction potential of the HER. Figure 13 shows the band alignment of several commonly studied semiconductor photocatalysts, relative to the standard reduction potentials of the HER and OER. Photocatalysts for water electrolysis have been reviewed recently.96, 97, 98, 99, 100, 101, 102, 103

Figure 13.

Band alignment of several water splitting catalysts, relative to the reduction potential of the water splitting half reactions. Reproduced with permission.104 Copyright 2016, Royal Society of Chemistry.

Bolton et al.105 classified single‐bandgap and dual‐bandgap water electrolysis systems into type S and type D systems, respectively, and determined efficiency limits on ideal PEC water electrolysis systems. Single‐bandgap systems use either a HER or OER photocatalyst, most often coupled to a nonabsorbing counter electrode, which offers simplicity in design compared to type D (also called Z‐scheme) systems, which use two photocatalysts with complementary bandgaps. The maximum achievable solar‐to‐H2 (STH) efficiency is 30.7% for a type S system, and 42.6% for a Z‐scheme system.105, 106 Additional semiconductor junctions do not improve the theoretical efficiency.107

Real PEC systems suffer additional losses from resistances in electronic and ionic conductivity, charge transfer losses, nonideal band alignments of semiconductors, and electron–hole pair recombination. Recombination is particularly challenging to overcome, and remains the focus of a number of studies.96, 108, 109, 110, 111 Improved charge separation has been achieved through the use of nanostructured catalyst surfaces,96, 112, 113, 114 as well as direct contact between reduction and oxidation sites through cocatalysts.109, 115, 116 Electrolyte resistance is also a significant challenge. Nafion is the best solid‐state electrolyte at room temperature, but requires the use of acidic pH, which limits the choice of catalyst material significantly.102 Anion‐exchange membranes are used under basic conditions, which allows the use of materials that would degrade at low pH, but generally have lower conductivity.117 Vargas‐Barbosa et al. have explored the use of bipolar membranes, which combine Nafion with an anion exchange.118 The offered improvements to the system's lifetime are enabled by allowing the use of favorable pH conditions for each electrode.

For comparison, some existing commercial water electrolysis systems have reached ≈44 kWh kg−1 of H2 produced, representing ≈81% efficiency in the conversion of electrical energy to H2. The most efficient solar panels commercially available at present reach values of ≈22.5%. Therefore, combining the two currently available systems results in an overall STH efficiency of ≈18%. The National Renewable Energy Laboratory maintains the record STH efficiency for a PEC device under controlled conditions at 16%,119 indicating that PEC water splitting has the potential to be a feasible option for H2 production at scale.

4.1.4. Solar‐Thermochemical CO2 and Water Splitting: Utilized in Strategy B

Solar‐thermochemical water splitting utilizes high temperatures generated by concentrated sunlight to drive the thermochemical splitting of water into H2 and O2 (Equation (5)). Temperatures in excess of 3000 °C are necessary to overcome the thermodynamic barrier to dissociate water directly, which results in the need for high light intensities and hence significant solar concentration ratios, and the associated prohibitively high thermal losses.120, 121 This makes direct thermally driven water dissociation less favorable as compared to other PV–electrochemical or photoelectrochemical methods. Multistep redox cycles have been shown to be a thermodynamically more favorable method to utilize solar heat for splitting water, as the cycles lower the temperature requirements significantly.120, 122 Conceptually, high‐temperature water electrolysis is similar to thermochemical CO2 splitting and syngas production.

Endothermic reactions can be driven by high‐temperature heat using focused sunlight.123 The thermochemical splitting of CO2 and water via two‐step metal oxide redox reactions operates at high temperatures and utilizes the entire solar spectrum, and thus has been identified as a thermodynamically favorable path to solar fuel production.124, 125, 126, 127

The thermochemical redox cycle for the production of solar CO, H2, or syngas is represented by Equations (10)–(12)

High‐temperature reduction of a metal oxide

| (10) |

Low‐temperature oxidation with water

| (11) |

Low‐temperature oxidation with CO2

| (12) |

where δ represents the nonstoichiometry in the metal oxides and therefore denotes the reduction extent.

A full thermochemical redox cycle consists of two separate half cycles. The first high‐temperature solar endothermic reduction step occurs at 1450–1600 °C. During this step, O2 is evolved, and the metal oxide is partially reduced to a nonstoichiometric or metallic state. Subsequently, the temperature is lowered to 700–1200 °C, and the reduced metal oxide is brought into contact with water and/or CO2 to generate H2 and/or CO, respectively. This event, during which the metal is reoxidized, is an exothermic process. Solar fuel such as H2 or CO can be produced by periodically alternating between the high‐temperature reduction and low‐temperature oxidation steps.

Although isothermal processes have been studied,128 most redox cycles operate in a temperature cycling mode. High‐temperature redox cycles have the benefit of inherently separating the product gases, preventing the formation of explosive H2/O2 mixtures and eliminating the need to separate the products, but are challenged by some level of efficiency loss due to additional process steps.120

Another approach that utilizes high‐temperature redox cycles is a method to improve the RWGS reaction described in Section 4.1.1. Wenzel looked at the solar‐thermal cycling of iron and iron oxide,129 however, with the reductant being H2 rather than simply solar heat. They called this process RWGS chemical looping. The three key reactions are shown in Equations (13)–(15)

RWGS

| (13) |

Oxidation

| (14) |

Reduction

| (15) |

As shown in Figure 14 , the idea here is that higher CO2‐to‐CO conversion is possible, which can result in high CO:CO2 ratios, together, however, with a lower reduction H2‐to‐water efficacy than the standard RWGS. Nevertheless, because H2–water separation is easier than CO–CO2, achieving higher yields of CO in the former is better from an overall efficiency standpoint, as it eliminates the costly CO–CO2 separation step.

Figure 14.

Equilibrium constants (K eq) for three main reactions, Equations (13)–(15). Reproduced with permission.129 Copyright 2016, John Wiley and Sons.

Materials for Thermochemical Redox Cycles: Several redox‐active metal oxides have been studied for thermochemical CO and/or H2 production. These include iron oxide, zinc oxide, cerium oxide, and perovskites. Iron oxide has already been demonstrated for thermochemical cycles in the 1970s.130 For the case of iron, the oxidation and reduction reactions between Fe2+ and Fe3+ of FeO, Fe2O3, and Fe3O4 are typically used.130, 131 For zinc oxide, the high‐temperature reduction of Zn2+ in ZnO to metallic zinc showed promising results, and besides basic research,120, 132 the system was also studied up to pilot scale.133 However, several challenges exist such as the high‐temperature range, phase transition, and the reactivity of metal vapors. For those reasons, other metal oxides, which remain solid and in the same phase during the whole thermochemical cycle, have been receiving increasing attention.

Cerium oxide fulfills these requirements as a reactor material, as both the oxidized and reduced forms of CeO2− δ have the same crystal structure. Numerous studies were published on ceria‐based systems on efficiency,124, 126, 127 doping,134, 135, 136, 137 structural design,138 and different reactor designs.139, 140 To date, ceria and its solid solutions represent the state of the art for thermochemical redox cycles and set the benchmark for new material developments for this application. This is due to the high efficiency and high chemical and thermal stability of ceria and its solid solutions.141

Perovskite oxides have only recently prompted research interests for thermochemical solar‐to‐fuel cycles. Due to the energetically very stable perovskite structure, which is versatile to structurally accommodate a large variety of elements from the periodic table, these materials exhibit potential advantages as compared to binary metal oxides. Due to their structural and compositional versatility, it is possible to design perovskite oxides with tunable nonstoichiometry, and catalytic and photo‐ and electrochemical properties.141, 142 First studies on solar‐to‐fuel conversion for perovskites were performed on manganite‐based perovskite compositions143, 144, 145, 146 and Y–Fe‐based systems.147 Further research is necessary to identify perovskite compositions that exhibit thermodynamic and reaction kinetic properties suitable for thermochemical cycles. The large number of possible compositions and versatility of the perovskite structure make these materials promising for thermochemical redox cycles.

4.2. Thermodynamic Implications of Using a CO2‐Rich Feed for Thermochemical MeOH Production

An Aspen Plus V9 equilibrium analysis similar to that in Section 2 was conducted for a CO2‐rich feed of 3:1 H2:CO2, resulting in an SN of 2. The results, shown in Figure 15 , indicate that the MeOH synthesis process with this feed favors higher equilibrium yields at low temperatures (becoming comparable to TCST production at ≈150 °C) and high pressures, similar to the CO‐rich case. Notice, however, that the yields for the CO2‐rich feed are lower in magnitude compared to the commercial feed case. This is primarily due to the presence of the RWGS reaction occurring in parallel, rather than the forward WGS.

Figure 15.

Equilibrium yields of MeOH and CO for a process using CO2‐rich feed; in this case, a 3:1 ratio of H2 to CO2 in the feed. Obtained using Aspen Plus V9 equilibrium analysis.

Unlike the WGS reaction (Equation (3)), which consumes the water produced by the CO2‐to‐MeOH synthesis reaction (Equation (2)), the RWGS (Equation (13)) produces water and therefore limits the equilibrium yield rather than providing the complementary feedback effect. At 200 °C and a constant pressure of 8 MPa, the yield from the commercial CO‐rich feed case is 58.8 mol%, while at the same conditions using CO2‐rich feed, the yield is only 13.2 mol%, declining to 7.6 mol% at 250 °C. Due to the endothermic nature of the RWGS reaction, its propensity only intensifies as the temperature of the process in increased.

Two general strategies exist for increasing the yield in the CO2‐rich feed case. First, adding CO to the feed can help facilitate the WGS reaction. Second, the yield can be increased by physically removing water from the system in situ through the use of a membrane reactor.148 A similar approach to removing water to drive the reaction forward is combining MeOH synthesis with its dehydration reaction, via the use of a bifunctional catalyst producing DME.