Abstract

Objective:

Multiple pharmacotherapies for treating anxiety exist, including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), the recommended first-line pharmacotherapy for pediatric anxiety. We sought to describe initial anti-anxiety medication use in children and estimate how long anti-anxiety medications were continued.

Methods:

In a large commercial claims database, we identified children (3–17 years) initiating prescription anti-anxiety medication from 2004–2014 with a recent anxiety diagnosis (ICD-9-CM = 293.84, 300.0x, 300.2x, 300.3x, 309.21, 309.81, 313.23). We estimated the proportion of children initiating each medication class across the study period and used multivariable regression to evaluate factors associated with initiation with an SSRI. We evaluated treatment length for each initial medication class.

Results:

Of 84,500 children initiating anti-anxiety medication, 70% initiated with an SSRI (63% [95%CI:62–63%] SSRI alone, 7% [95%CI:7–7%] SSRI+another anti-anxiety medication). Non-SSRI medications initiated included benzodiazepines (8%), non-SSRI antidepressants (7%), hydroxyzine (4%), and atypical antipsychotics (3%). Anxiety disorder, age, provider type, and co-morbid diagnoses were associated with initial medication class. The proportion of children refilling their initial medication ranged from 19% (95%CI:18–20%) of hydroxyzine and 25% (95%CI:24–26%) of benzodiazepine initiators to 81% (95%CI:80–81%) of SSRI initiators. Over half (55%, 95%CI:55–56%) of SSRI initiators continued SSRI treatment for 6 months.

Conclusion:

SSRIs are the most commonly used first-line medication for pediatric anxiety, with about half of SSRI initiators continuing treatment for 6 months. Still, a third began therapy on a non-SSRI medication, for which there is limited evidence of effectiveness for pediatric anxiety, and a notable proportion of children initiated with two anti-anxiety medication classes.

INTRODUCTION

Anxiety disorders are one of the most common mental illnesses in children in the United States (US),1 with lifetime prevalence of pediatric anxiety around 15–20%.2 Children with anxiety disorders have an increased risk for future additional anxiety disorders, depression, and substance use and experience academic impairments.3–8 Pediatric anxiety disorders are likely to occur in association with somatic symptoms, including headaches, nausea, and trouble sleeping.9 In 2010, anxiety disorders were the fifth leading contributor to years lived with disability in the US,10 demonstrating the sustained impact of unmanaged anxiety. Early diagnosis and effective treatment of anxiety disorders are essential to manage symptoms and improve quality of life and can reduce the persistence of anxiety into young adulthood and beyond.8,11

The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) practice parameters recommend psychotherapy as the first-line treatment for anxiety of mild severity.8,12,13 AACAP recommends pharmacological treatment when moderate to severe symptoms or comorbid psychiatric disorders are present, or when children are unable/unwilling to participate in or have a partial response to psychotherapy.8,12,13 While there are a variety of pharmacological approaches to treat anxiety, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are considered the first-line pharmacotherapy for pediatric anxiety.8,12,13 Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) showed efficacy of SSRIs over placebo in children with anxiety.14,15 SSRIs are generally well tolerated and have a mild side effect profile compared to other drugs, and there is minimal empirical evidence to support use of other medications to treat pediatric anxiety.8,12,13,16–18 However, since October 2004, antidepressants, including SSRIs, carry a black-box warning for an increased risk of suicidality in children19 and, while select SSRIs are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), SSRIs are not approved for pediatric non-OCD anxiety. These factors may lead caregivers or providers to prefer non-SSRI medications for children beginning pharmacotherapy for anxiety.

Evidence on long-term efficacy and safety of anti-anxiety medications for children is limited, raising concern over the potential harms of routine pharmacological anxiety treatment.16,20 The 2007 AACAP guidelines caution that while RCTs have established the safety and efficacy of short-term SSRI treatment for pediatric anxiety, the benefits and risks of long-term SSRI use have not been studied.8 Post-trial follow-up data have provided important evidence of continued SSRI response up to 36 weeks.21,22 Benzodiazepines, another common anti-anxiety medication, are usually recommended for only short-term treatment given dependency concerns.16

There is little understanding of how often SSRIs and other pharmacotherapies are used and their duration of use when treating pediatric anxiety. Understanding treatment utilization can detail what, if any, changes in clinical practice are needed to improve treatment for pediatric anxiety. Therefore, this study sought to estimate the initial medication class received by children diagnosed with anxiety beginning anti-anxiety medication, determine whether this varied across the study period and by patient characteristics, and estimate treatment continuation of the initial anti-anxiety medication.

METHODS

We used Truven Health Analytics’ MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters database, containing individuals covered by employer-sponsored private health insurance across the US. We utilized data from enrollment files, inpatient and outpatient services, and outpatient drug claims for reimbursed, dispensed prescriptions. We included children 3–17 years with an anxiety diagnosis who initiated an anti-anxiety medication between 2004 and 2014. An anxiety diagnosis was defined as an inpatient or outpatient ICD-9-CM code (293.84, 300.0x, 300.2x, 300.3x, 309.21, 309.81, 313.23). These codes roughly correspond to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, DSM-5 anxiety disorders23 and additionally include post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and OCD, as they share similar treatment recommendations and were previously classified under anxiety disorders.24

To identify initiators of anti-anxiety medications we selected the initial anti-anxiety prescription based on records of dispensed prescriptions, defined as having no anti-anxiety prescription in the prior year. Children were required to have continuous insurance enrollment with prescription and mental health services coverage the year before medication initiation. We defined anti-anxiety medications as medications with trial evidence of effectiveness in treating anxiety in adult or pediatric populations and also medications suggested as potential effective treatments for anxiety (Table 1, grouped into medication classes).17,18,25,26 Children could have initiated anti-anxiety pharmacotherapy with two medication classes (e.g. SSRI+benzodiazepine); children initiating with >2 classes were excluded (0.3%). As these therapies have multiple indications, we required ≥1 anxiety diagnosis within 30 days prior to or on the date of the initial anti-anxiety prescription (Supplementary eFigure 1).

Table 1.

Anti-anxiety medications included grouped by medication class

| Medication class | Generic names included |

|---|---|

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors | Citalopram, escitalopram, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine, sertraline, vilazodone |

| Serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors | Desvenlafaxine, duloxetine, levomilnacipran, milnacipran, venlafaxine |

| Tricyclic antidepressants | Amitriptyline, clomipramine, desipramine, doxepin, imipramine, maprotiline, nortriptyline, protriptyline, trimipramine, amoxapine* |

| Bupropion | − |

| Other antidepressants | Atomoxetine, isocarboxazid, mirtazapine, nefazodone, phenelzine, selegiline transdermal, tranylcypromine, trazodone, vortioxetine |

| Benzodiazepines | Alprazolam, chlordiazepoxide, clobazam, clonazepam, clorazepate, diazepam, halazepam, lorazepam, oxazepam, prazepam |

| Buspirone | − |

| Anticonvulsants | Carbamazepine, gabapentin, lamotrigine, levetiracetam, pregabalin, tiagabine, topiramate, valporic acid |

| Atypical antipsychotics | Aripiprazole, lurasidone, olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, ziprasidone |

| Hydroxyzine | − |

| Beta-blockers | Acebutolol, atenolol, atenolol/chlorthalidone, bendroflumethiazide/nadolol, betaxolol, bisoprolol fumarate, carteolol, carvedilol, esmolol, metoprolol succinate, metoprolol tartrate, nadolol, nebivolol, penbutolol sulfate, pindolol, propranolol, sotalol, timolol maleate |

| Other | Clonidine, D-cycloserine, guanfacine, memantine, prazosin, riluzole |

Dibenzoxazepinederivative tricyclic antidepressant

Each initial anti-anxiety prescription was grouped into one of twelve medication classes but children were also broadly classified as initiating 1) SSRI with no other anti-anxiety medication (SSRI alone), 2) SSRI+another anti-anxiety medication, and 3) non-SSRI anti-anxiety medication. These mutually exclusive categories represented three treatment strategies.

Following initiation, treatment length per initial medication class was evaluated. A child was considered to have discontinued treatment in that medication class when there was no record of a dispensed prescription 30 days after the previous prescription’s days supply ran out. Switching agents within a medication class was regarded as continuing that medication class. The primary measures for treatment continuation were 1) refilling a prescription in the initial medication class before discontinuation and 2) remaining on treatment for 6 months.

Patient characteristics were collected in the year prior to and on the date of medication initiation to describe the study cohort and identify factors associated with initial medication choice. Characteristics included age, sex, anxiety diagnosis details, anxiety-related symptoms, psychiatric co-morbidities, non-psychiatric co-morbidities, healthcare utilization, region, and year of medication initiation. The anxiety diagnosis most prior to or on the date of anti-anxiety medication initiation (index diagnosis) was grouped into mutually exclusive categories. Patients with an unspecified and a specific anxiety diagnosis were assigned to the specific diagnosis; patients with ≥1 specific diagnosis were grouped under ‘multiple’. The provider type of the index diagnosis was categorized as psychiatry, family practice, pediatrics, psychologist/therapist, all other types, and unknown/multiple providers. For common psychiatric co-morbidities (depression, adjustment disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder [ADHD]) we created indicators for a recent diagnosis (within 30 days) or only a prior diagnosis (31–365 days prior). Any recent psychiatric diagnosis was defined as an ICD-9-CM code=290–319 (excluding anxiety diagnoses).

Statistical analyses

We determined the number and proportion of children initiating each anti-anxiety medication class overall and stratified by anxiety disorder and by year of initiation and age. As the proportion of children diagnosed with co-morbid depression and co-morbid ADHD increased across the study period, trends identified were examined in children without depression and without ADHD. We used multivariable Poisson regression with robust variance to estimate fully adjusted risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) to identify factors independently associated with initiating 1) SSRI+another anti-anxiety medication vs. SSRI alone, 2) non-SSRI anti-anxiety medication vs. SSRI alone, and 3) SSRI+another anti-anxiety medication vs. non-SSRI anti-anxiety medication. We used Kaplan-Meier (KM) estimator to examine treatment continuation for each initial medication class up to 2 years, with censoring at insurance disenrollment and end of data (12/31/2014). The proportion of children refilling their initial medication class was evaluated in children with ≥60 days of insurance enrollment after medication initiation. In an exploratory analysis, we estimated the proportion of children initiating with a non-SSRI anti-anxiety medication who subsequently filled an SSRI prescription within three months in children with ≥3 months of insurance enrollment.

Additional sensitivity analyses were completed. Given the multiple indications for anti-anxiety medications, we examined the proportion of children initiating each medication class in restricted cohorts: 1) children initiating anti-anxiety medication the same day as an anxiety diagnosis and 2) children with ≥2 anxiety diagnoses and no recent co-morbid psychiatric diagnosis. We considered an interaction term between anxiety disorder and provider type in our multivariable model. When examining treatment continuation, analyses were repeated using 15-and 60-day grace periods to define discontinuation and stratified by 1 vs. ≥2 prior anxiety diagnoses. The University of North Carolina Institutional Review Board approved this study.

RESULTS

We identified 84,500 children with diagnoses for anxiety who initiated anti-anxiety pharmacotherapy. The cohort had more girls (58%), few children aged 3–5 years (2%), with the majority 14–17 years (58%), and 50% had an index anxiety diagnosis of unspecified anxiety (Table 2; Supplementary eTable 1). Approximately 24% were diagnosed with anxiety by a psychiatrist 29% by a pediatrician or family practitioner. Fifty-seven percent of children had an anxiety diagnosis on the day of medication initiation, resulting in a median number of days between the index anxiety diagnosis and anti-anxiety medication initiation of 0 (interquartile range=0–3).

Table 2.

Selecteda characteristics of children initiating anti-anxiety medication and factors associated with initiating with SSRI+another anti-anxiety medication vs. SSRI alone and with non-SSRI anti-anxiety medication vs. SSRI alone

| Initial anti-anxiety treatment group |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children initiating anti- anxiety medication (N=84,500) No.(%) |

SSRI alone (N=53,009) No.(%) |

SSRI + another anti-anxiety medication (N=5,863) |

Non-SSRI anti-anxiety medication (N=25,628) |

|||

| Patient characteristic | No.(%) | Vs. SSRI alone Multivariable RR(95% CI)a |

No.(%) | Vs. SSRI alone Multivariable RR(95% CI)a |

||

| Female | 49,255 (58) | 31,688 (60) | 3,771 (64) | REF | 13,796 (54) | REF |

| Male | 35,245 (42) | 21,321 (40) | 2,092 (36) | 1.0(0.9-1.0) | 11,832 (46) | 1.1(1.1-1.1) |

| Age, median(IQR) | 14 (11-16) | 14 (11-16) | 15 (13-16) | 14 (10-16) | ||

| 3-5 years | 1,449 (2) | 696 (1) | 25 (<1) | 0.4(0.2-0.5) | 728 (3) | 1.4(1.3-1.5) |

| 6-9 years | 12,377 (15) | 7,782 (15) | 332 (6) | 0.4(0.4-0.5) | 4,263 (17) | 1.0(1.0-1.1) |

| 10-13 years | 21,997 (26) | 14,525 (27) | 1,269 (22) | 0.8(0.7-0.8) | 6,203 (24) | 0.9(0.9-1.0) |

| 14-17 years | 48,677 (58) | 30,006 (57) | 4,237 (72) | REF | 14,434 (56) | REF |

| Anxiety disorder, index diagnosis | ||||||

| Unspecified | 42,652 (50) | 26,037 (49) | 2,417 (41) | REF | 14,198 (55) | REF |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 20,508 (24) | 13,812 (26) | 1,417 (24) | 1.1(1.0-1.2) | 5,279 (21) | 0.8(0.8-0.8) |

| OCD | 6,194 (7) | 4,773 (9) | 353 (6) | 0.9(0.8-1.0) | 1,068 (4) | 0.5(0.5-0.6) |

| Panic disorder | 4,294 (5) | 1,967 (4) | 507 (9) | 2.0(1.9-2.2) | 1,820 (7) | 1.3(1.3-1.4) |

| PTSD | 3,531 (4) | 1,683 (3) | 492 (8) | 1.5(1.4-1.7) | 1,356 (5) | 1.2(1.1-1.2) |

| Social phobia | 1,972 (2) | 1,465 (3) | 156 (3) | 1.0(0.9-1.2) | 351 (1) | 0.6(0.6-0.7) |

| Otherc | 3,530 (4) | 1,993 (4) | 279 (5) | 1.6(1.4-1.7) | 1,258 (5) | 1.1(1.0-1.1) |

| Multiple | 1,819 (2) | 1,279 (2) | 242 (4) | 1.6(1.5-1.9) | 298 (1) | 0.6(0.6-0.7) |

| Provider type, index anxiety diagnosis | ||||||

| Psychiatry | 20,514 (24) | 14,114 (27) | 1,674 (29) | REF | 4,726 (18) | REF |

| Psychologist; Therapist | 10,124 (12) | 5,761 (11) | 444 (8) | 0.7(0.7-0.8) | 3,919 (15) | 1.6(1.6-1.7) |

| Family practice | 11,136 (13) | 7,004 (13) | 788 (13) | 0.9(0.8-0.9) | 3,344 (13) | 1.0(1.0-1.1) |

| Pediatrics | 13,565 (16) | 9,574 (18) | 502 (9) | 0.5(0.5-0.6) | 3,489 (14) | 0.9(0.8-0.9) |

| Other | 20,980 (25) | 12,109 (23) | 1,768 (30) | 1.0(0.9-1.0) | 7,103 (28) | 1.3(1.2-1.3) |

| Unknown | 8,181 (10) | 4,447 (8) | 687 (12) | 1.0(0.9-1.1) | 3,047 (12) | 1.3(1.3-1.4) |

| Psychiatric co-morbidity detailsd | ||||||

| Any recent non-anxiety psychiatric diagnosisb | 38,363 (45) | 23,841 (45) | 3,188 (54) | − | 11,334 (44) | − |

| Depression diagnosis (REF=no diagnosis)b | ||||||

| Recent diagnosis | 18,875 (22) | 13,163 (25) | 2,231 (38) | 1.1(1.0-1.2) | 3,481 (14) | 0.6(0.6-0.6) |

| Prior diagnosis, no recent diagnosis | 3,275 (4) | 2,017 (4) | 201 (3) | 0.9(0.8-1.1) | 1,057 (4) | 0.9(0.9-1.0) |

| Attention deficit disorder (REF=no diagnosis)b | ||||||

| Recent diagnosis | 10,191 (12) | 5,139 (10) | 428 (7) | 1.0(0.9-1.2) | 4,624 (18) | 1.5(1.5-1.6) |

| Prior diagnosis, no recent diagnosis | 4,877 (6) | 2,911 (5) | 236 (4) | 1.1(0.9-1.2) | 1,730 (7) | 1.2(1.1-1.2) |

| Other episodic mood disorder | 4,073 (5) | 2,036 (4) | 455 (8) | 1.2(1.1-1.3) | 1,582 (6) | 1.3(1.2-1.3) |

| Bipolar disorder | 1,479 (2) | 466 (1) | 164 (3) | 1.6(1.4-1.8) | 849 (3) | 1.8(1.7-1.9) |

| Index anxiety diagnosis in inpatient setting | 4,313 (5) | 1,981 (4) | 938 (16) | 2.1(1.9-2.3) | 1,394 (5) | 1.2(1.1-1.2) |

| Mental health diagnostic/evaluation visit | 45,051 (53) | 29,917 (56) | 3,294 (56) | 1.1(1.0-1.1) | 11,840 (46) | 0.8(0.8-0.8) |

IQR: Interquartile range, REF: Referent category

Multivariable RRs are from the full model that includes all variables in supplemental eTable 1; the multivariable RRs (95% CI) for the comparison between SSRI + another anti-anxiety medication vs. non-SSRI anti-anxiety medication are available in supplemental eTable 1; ‘Any recent non-anxiety psychiatric diagnosis’ was not entered into the full multivariable model as specific indicators for psychiatric disorders were used instead

Recent=0–30 days before anti-anxiety medication initiation, prior=31–365 days before anti-anxiety medication initiation

Anxiety disorders with <1000 children: other anxiety, separation anxiety, selective mutism, anxiety due to medical condition, agoraphobia, other/specific phobia

Definitions: depression (ICD-9: 296.2x, 296.3x, 300.4x, 309.1x, 311.x), attention deficit disorder (ICD-9: 314.0x), other episodic mood disorder (ICD-9: 296.9x), bipolar disorder/cyclothymic (ICD-9: 296.0x, 296.4x, 296.5x, 296.6x, 296.7x, 296.8x, 301.13)

Overall, 63% of children initiated with an SSRI alone and an additional 7% initiated an SSRI+another anti-anxiety medication (Table 3). Benzodiazepines were the most commonly used non-SSRI medication (8%=benzodiazepine alone, 3%=SSRI+benzodiazepine), with the majority of use in children 14–17 years. Eight-percent initiated with a non-SSRI antidepressant and a small proportion initiated with an atypical antipsychotic, hydroxyzine, or clonidine/guanfacine. In sensitivity analyses with restricted cohorts, there was a slightly higher use of SSRIs alone, but overall findings were consistent (Table 3).

Table 3.

Initial anti-anxiety medication class in children with diagnosed anxiety beginning anti-anxiety pharmacotherapy

| Primary analysis: Full cohort (N=84,500) |

Anxiety diagnosis same day as initial anti- anxiety prescription (N=47,973) |

2+ Anxiety diagnoses, no recent comorbid psychiatric diagnosisa (N=20,249) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % (95% CI) | No. | % (95% CI) | No. | % (95% CI) | |

| SSRI alone | 53,009 | 63% (62–63) | 32,044 | 67% (66–67) | 13,492 | 67% (66–67) |

| SSRI+another anti-anxiety medicationb | 5,863 | 7% (7–7) | 3,664 | 8% (7–8) | 1,147 | 6% (5–6) |

| SSRI+benzodiazepine | 2,528 | 3% | 1,890 | 4% | 652 | 3% |

| SSRI+other antidepressant | 926 | 1% | 475 | 1% | 113 | 1% |

| SSRI+atypical antipsychotic | 894 | 1% | 299 | 1% | 104 | 1% |

| SSRI+hydroxyzine | 761 | 1% | 511 | 1% | 132 | 1% |

| Non-SSRI anti-anxiety medication | 25,628 | 30% (30–31) | 12,265 | 26% (25–26) | 5,610 | 28% (27–28) |

| Benzodiazepine | 7,125 | 8% | 4,038 | 8% | 1,735 | 9% |

| Hydroxyzine | 3,244 | 4% | 1,937 | 4% | 750 | 4% |

| Other antidepressant | 2,987 | 4% | 1,051 | 2% | 658 | 3% |

| Other anti-anxietyc | 2,967 | 4% | 1,090 | 2% | 519 | 3% |

| Atypical antipsychotic | 2,264 | 3% | 732 | 2% | 343 | 2% |

| Bupropion | 1,251 | 1% | 592 | 1% | 211 | 1% |

| Buspirone | 1,226 | 1% | 876 | 2% | 253 | 1% |

| TCA | 1,157 | 1% | 497 | 1% | 382 | 2% |

| Anticonvulsant | 988 | 1% | 289 | 1% | 294 | 1% |

| SNRI | 761 | 1% | 345 | 1% | 165 | 1% |

| Beta-blocker | 705 | 1% | 391 | 1% | 176 | 1% |

| Non-SSRI + Non-SSRI | 953 | 1% | 427 | 1% | 124 | 1% |

| 84,500 | 100% | 47,973 | 100% | 20,249 | 100% | |

At least two anxiety diagnoses in the prior year and no comorbid psychiatric diagnosis in the 30 days before anti-anxiety medication initiation

Primary analysis: SSRI+other anxiety (n=355), SSRI+buspirone (n=133), SSRI+beta-blocker (n=110), SSRI+anticonvulsant (n=83), SSRI+TCA (n=55), SSRI+bupropion (n=17), SSRI+SNRI (not reported due to small sample)

98% of prescriptions were clonidine or guanfacine

Across the study period initiation with an SSRI remained fairly stable in children 3–13 years but increased in children 14–17 years (2004=55%, 2014=66%, Supplementary eFigure 2). The proportion of children 14–17 years initiating with a benzodiazepine decreased across the study period (2004=20%, 2014=10%) and approached the lower levels of use in younger children (Supplementary eFigure 3). This trend remained in children without a recent co-morbid depression diagnosis. While few children 3–5 years with anxiety initiated an anti-anxiety medication (n=1,449), the proportion that did so on guanfacine or clonidine increased, from 11% in 2007 to 18% in 2009 and further to 27% by 2014. The increase remained but stabilized (2007 = 8%, 2009 = 15%, 2014 = 18%) when restricted to children without a co-morbid ADHD diagnosis.

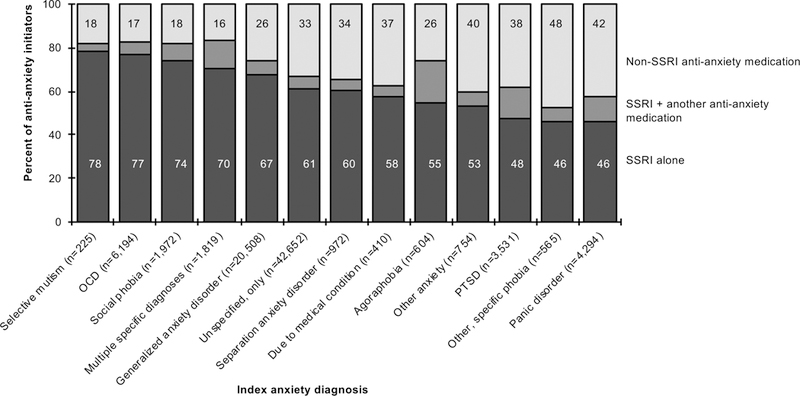

The initial medication prescribed varied by anxiety disorder (Figure 1). Children with OCD (77%) and selective mutism (78%) were most likely to initiate with an SSRI alone and children with panic disorder (46%), other/specific phobia (46%), and PTSD (48%) were least likely. In children with panic disorder 24% initiated with a benzodiazepine alone and 8% with an SSRI+benzodiazepine (full cohort=8% and 3%, respectively). In children with PTSD, 9% initiated with an atypical antipsychotic alone (19%, n=66 in those with a recent co-morbid disturbance of conduct or oppositional defiant disorder diagnosis vs. 8%, n=268 without this diagnosis) and 5% with an SSRI+atypical antipsychotic (full cohort=3% and 1%, respectively).

Figure 1.

The proportion of children initiating anti-anxiety pharmacotherapy with SSRI alone, SSRI+another anti-anxiety medication, or non-SSRI anti-anxiety medication by index anxiety diagnosisa aDisplayed by the anxiety disorder with the highest proportion of children initiating with an SSRI alone to the lowest proportion of children initiating with an SSRI alone

The initial anti-anxiety medication also varied by age, provider type, co-morbid psychiatric diagnoses, and other patient factors (Table 2; Supplementary eTable 1). Children with a recent depression diagnosis were less likely (PR:0.57, 95%CI:0.56–0.59) and children with a recent ADHD diagnosis were more likely (PR:1.53, 95%CI:1.48–1.59) to initiate a non-SSRI medication than SSRI alone. Children 3–13 years were less likely to initiate with an SSRI+another anti-anxiety medication vs. SSRI alone, as were children diagnosed with anxiety by a pediatrician (PR:0.53, 95%CI:0.48–0.59) compared to a psychiatrist. Inferences were limited for the interaction between anxiety disorder and provider type given sample size. However, the primary variation was with social phobia where family practice providers were more likely to prescribe an SSRI+another anti-anxiety medication and panic disorder where pediatrics and family practice more likely to prescribe a non-SSRI than psychiatry.

SSRI prescriptions were most likely to be refilled (81%), followed by atypical antipsychotics (71%) and bupropion (69%) (Table 4). Over half (55%) of children initiating with an SSRI continued SSRI treatment for 6 months, 34% for 1 year, and 17% for 2 years. Benzodiazepine and hydroxyzine initiators were least likely to refill (25% and 19%, respectively) and continue treatment for 6 months (5% and 3%, respectively). Children initiating a benzodiazepine or hydroxyzine were more likely to receive a shorter days supply: 54% of initial benzodiazepine prescriptions and 42% of hydroxyzine prescriptions were for ≤10 days compared with only 6% of initial SSRI prescriptions with a days supply <30 days. We observed similar patterns when varying the grace period to define treatment continuation and when stratified by ≥2 prior anxiety diagnoses, with higher continuation in children with ≥2 prior diagnoses (Supplementary eTable 3).

Table 4.

The proportion of children refilling their initial anti-anxiety medication class and continuing that medication class for six months

| Initial medication classa | Total No. |

Refilled initial prescriptionb % (95% CI) |

Continued medication for 6 months % (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SSRI | 58,872 | 81 (80–81) | 55 (55–56) |

| Benzodiazepine | 10,005 | 25 (24–26) | 5 (4–7) |

| Hydroxyzine | 4,165 | 19 (18–20) | 3 (1–7) |

| Other antidepressant | 4,151 | 58 (56–59) | 28 (26–31) |

| Atypical antipsychotic | 3,501 | 71 (69–72) | 41 (38–43) |

| Other anti-anxietyc | 3,424 | 64 (62–66) | 38 (35–40) |

| Buspirone | 1,474 | 49 (46–51) | 19 (15–23) |

| Bupropion | 1,459 | 69 (66–71) | 37 (33–40) |

| TCA | 1,279 | 55 (52–57) | 27 (23–32) |

| Anticonvulsant | 1,218 | 64 (61–66) | 35 (30–39) |

| Beta-blocker | 887 | 32 (29–35) | 14 (9–20) |

| SNRI | 881 | 66 (63–69) | 38 (33–43) |

Each medication class evaluated separately for patients initiating two classes

Calculated from the 93% of children with ≥60 days of continuous insurance in follow-up

98% of prescriptions were clonidine or guanfacine

Eighteen percent (n=4,121) of children initiating with a non-SSRI anti-anxiety medication subsequently filled an SSRI prescription within 3 months. This varied by medication class including 24% of benzodiazepine initiators and 20% of atypical antipsychotic initiators later filling an SSRI prescription (Supplementary eTable 4).

DISCUSSION

Concordant with the majority of evidence and recommendations, SSRIs were the most commonly used first-line anti-anxiety medication in children with anxiety diagnoses. By 2007 there was convincing evidence that SSRIs were effective in treating pediatric anxiety, summarized in a meta-analysis of RCTs14 with findings upheld in an updated meta-analysis.15 There are appropriate reasons for a child to initiate with a non-SSRI medication; however, those reasons likely do not account for the third of children who began pharmacotherapy with an anti-anxiety medication with limited evidence of effectiveness, or no trial evidence.

There is evidence demonstrating efficacy of SNRIs for some anxiety disorders,14 and duloxetine was recently approved for pediatric generalized anxiety disorder.27 SNRIs are not recommended first-line therapy and were rarely used as the initial anti-anxiety medication in our study. Benzodiazepines, while used much less frequently than SSRIs, were the second most commonly used initial anti-anxiety medication. Conversely, in US adults with anxiety, where benzodiazepines are approved for several anxiety disorders, SSRIs and benzodiazepines are used at more comparable frequencies.28,29 While the proportion of children initiating with an atypical antipsychotic remained low across the study period, given the potential harms of antipsychotics, they should not be considered as first-line treatment for anxiety.30 Our finding that 18% of non-SSRI initiators filled an SSRI prescription in the following months highlights that some children could have avoided being exposed to potential side effects from medications lacking evidence of effectiveness.

In adult guidelines for panic disorder, SSRIs, SNRIs, tricyclic antidepressants, and benzodiazepines are said to be roughly comparable in efficacy,31 possibly explaining the higher observed benzodiazepine use in children with panic disorder. Relatedly, while SSRIs are approved to treat PTSD in adults,12 there is less evidence supporting SSRIs for pediatric PTSD, likely explaining the lower proportion of children with PTSD initiating with an SSRI alone.12,26 The variation observed in initial medication class by co-morbid psychiatric diagnoses was expected and potentially appropriate as medication selection should consider co-morbidities.8 Still, almost a third of children with no recent co-morbid psychiatric diagnosis initiated with a non-SSRI anti-anxiety medication. Variation in initial medication class by provider type is likely influenced by familiarity with treatment guidelines and clinical experience or potentially due to unmeasured differences in anxiety and co-morbidity severity between providers.

The large increase in the proportion of young children initiating anti-anxiety pharmacotherapy with guanfacine or clonidine occurred following the medications’ FDA approval for pediatric ADHD. In the US, guanfacine and clonidine use increased from 11% of children receiving any psychotropic medication in 2009 to 14% in 2011, with the majority of use for ADHD.32 The trend we observed with guanfacine and clonidine could be related to caregiver preferences for selecting treatment with pediatric FDA approval.33 Relatedly, caregivers may prefer initiating a child on a non-antidepressant given the antidepressant black-box warning. In a small chart-review of children with anxiety who were offered a trial of antidepressants, the percentage of caregivers refusing antidepressant treatment increased after the black-box warning.34

AACAP practice parameters state that prescribers should have a clear rationale for prescribing medication combinations.35 In our cohort 7% initiated with an SSRI+another anti-anxiety medication. Half of those children initiated an SSRI+benzodiazepine, which is sometimes done to achieve rapid reduction in severe anxiety symptoms.8 The practice of concurrent anti-anxiety medication initiation was less common in younger children and children diagnosed by a provider outside psychiatry, but occurred across provider types, similar to findings from broader psychotropic polypharmacy in children.36 Despite some exceptions, beginning pharmacotherapy with an SSRI+another anti-anxiety medication raises concern given limited data on psychotropic polypharmacy in regards to effectiveness and possible increased adverse event burden, especially for treatment naïve children.37

Pediatric OCD guidelines state that treatment should typically be continued for 6–12 months then gradually withdrawn.13 For non-OCD anxiety a medication free period has been recommended in children who experienced anxiety symptom reduction for a year,38 but there are no formal guidelines on recommended SSRI treatment length.8,12 In our study just over half of commercially insured children with anxiety continued SSRI treatment for 6 months. This was similar to 6-month SSRI estimates in children with major depressive disorder (46%),39 where guidelines are more specific, recommending ≥6 months of continued medication.4

The previously described gap between the amount of provider contact required by evidence-based treatments and the amount received in children with anxiety40 could influence early medication discontinuation. Medication discontinuation may be appropriate, including if the child responded to concurrent cognitive behavioral therapy. As such, we cannot discern whether medication was discontinued due to nonresponse, side effects, or other reasons, and whether a clinician advised discontinuation. In certain instances the initial anti-anxiety medication was likely intended for short-term use (i.e. benzodiazepine and hydroxyzine with short initial days supply values). It is reassuring that the recommended medication class with the most evidence of efficacy for pediatric anxiety had the highest continuation and that benzodiazepines were used primarily for short-term treatment.16

Around 44% of children with severe mental health impairment receive outpatient mental health services41 and 31% of children with anxiety report receiving treatment, 9% receive medication.42 These estimates highlight that our findings apply to a subset of children with anxiety, children who were diagnosed and initiated an anti-anxiety pharmacotherapy. With our additional requirements of continuous private insurance coverage, our results are likely not generalizable to all US children. Future research could explore whether the initial prescription anti-anxiety medication differs in children covered by Medicaid given prior research on differences in psychotropic and antipsychotic use in children on public and private insurance.43,44

Almost half of children in our population had an unspecified anxiety diagnosis given most prior to, or on, the data of anti-anxiety medication initiation. The use of unspecified anxiety diagnoses has increased in youth, rising from 45% (1999–2002) to 58% (2007–2010) of anxiety diagnoses in ambulatory settings.45 Children classified as having an unspecified anxiety diagnosis prior to medication initiation likely include children with a more specific anxiety disorder diagnosis that was not evaluated or not recorded, resulting in misclassification. However, in some cases, children with an unspecified anxiety diagnosis may represent those with sub-threshold anxiety that do not meet the criteria for a specific anxiety disorder. These factors limit our ability to interpret the associations between unspecified anxiety and treatment choice.

Additional limitations should be considered. While we aimed to describe anti-anxiety medication utilization in children with anxiety, including children with co-morbid conditions, we cannot be certain that medications were initiated to treat anxiety. It is possible that when an anxiety diagnosis was recorded on the same day as medication initiation the two events were unrelated. Additionally, little is known about the validity of ICD-9-CM anxiety diagnostic codes for children in administrative data and ICD-9 codes for anxiety disorders do not perfectly correspond with DSM diagnoses. Selected symptoms that may guide anti-anxiety medication selection are not available in our datasource. The study design excluded children with baseline anti-anxiety medication use and, given the multiple indications of these medications, we thereby excluded children with an array of previously treated conditions. We do not have information on if and when dispensed medications were taken, including if medications filled the same day were taken concurrently, and whether adequate dosing was achieved. Treatment length estimates rely on correct days supply values for dispensed prescriptions. We lack details on whether anti-anxiety medications were intended for short-term or as-needed use and on prescriptions provided in-hospital or obtained outside insurance (i.e. paid out-of-pocket, free samples), which could result in misclassification of anti-anxiety medication initiation or continuation.

While the majority of children with anxiety initiated anti-anxiety pharmacotherapy with an SSRI, as recommended by current guidelines, a third of children initiated with a non-SSRI anti-anxiety medication and a notable proportion of children initiated with two anti-anxiety medication classes. By describing the initial anti-anxiety pharmacotherapy utilized in children with anxiety, our study can inform efforts to better tailor medication use in pediatric anxiety.

Supplementary Material

Clinical points.

There are many potential prescription medications for treating anxiety and it was unclear what anti-anxiety medications are used as first-line pharmacotherapy in pediatric anxiety.

The majority initiated with an SSRI, the recommended first-line medication for pediatric anxiety, though a third of children began pharmacotherapy with a non-SSRI anti-anxiety medication and a notable proportion of children initiated with two anti-anxiety medication classes.

Acknowledgments

Sources of financial and material support: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (Bethesda, MD) under Award Number F31MH107085 (G. Bushnell). This content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The database infrastructure was funded by the Department of Epidemiology, UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health, the Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research, UNC, the CER Strategic Initiative of UNC’s Clinical Translational Science Award (UL1TR001111), and the UNC School of Medicine (Chapel Hill, NC). Copyright ©2015 Truven Health Analytics Inc. All Rights Reserved.

Role of the sponsor: The funding agencies had no role in the design and conduct of the study, collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data, and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Ms. Bushnell receives support from the National Institute of Mental Health as a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award (NRSA) Individual Predoctoral Fellow (F31MH107085). Ms. Bushnell previously held a graduate research assistantship with GlaxoSmithKline and was the Merck fellow for the Center for Pharmacoepidemiology (both ended 12/2015).

Dr. Brookhart receives investigator-initiated research funding from the National Institutes of Health and through contracts with the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s DEcIDE program and the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute. Within the past three years, he has received research support from Amgen and AstraZeneca and has served as a scientific advisor for Amgen, Merck, and GlaxoSmithKline (honoraria/payment received by the institution). He has received consulting fees from RxAnte, Inc. and World Health Information Consultants.

Dr. Stürmer receives investigator-initiated research funding from the National Institutes of Health (Principal Investigator, R01 AG023178; Co-Investigator: R01 CA174453, R01 HL118255, R21-HD080214). He also receives salary support as Director of the Comparative Effectiveness Research Strategic Initiative, NC TraCS Institute, UNC Clinical and Translational Science Award (UL1TR001111) and as Director of the Center for Pharmacoepidemiology, Department of Epidemiology UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health (current members: GlaxoSmithKline, UCB BioSciences, Merck) and research support from pharmaceutical companies (Amgen, AstraZeneca) to the Department of Epidemiology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Stürmer does not accept personal compensation of any kind from any pharmaceutical company. He owns stock in Novartis, Roche, BASF, AstraZeneca, and Novo Nordisk.

Dr. Compton receives research support from the National Institute of Mental Health, NC GlaxoSmithKline Foundation, Mursion, Inc. and has been a consultant for Shire, received honoraria from the Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, Nordic Long-Term OCD Treatment Study Research Group, and The Centre for Child and Adolescent Mental Health, Eastern and Southern Norway, and given expert testimony for Duke University.

Dr. Walkup has past research support for federally funded studies including free drug and placebo from Pfizer’s pharmaceuticals in 2007 to support the Child Adolescent Anxiety Multimodal study; free medication from Abbott pharmaceuticals in 2005 for the Treatment of the Early Age Media study; free drug and placebo from Eli Lilly in 2003 for the Treatment of Adolescents with Depression study. He currently receives research support from the Tourette’s Association of America and the Hartwell Foundation. He also receives royalties from Guilford Press and Oxford Press for multi-author books published about Tourette syndrome.

Dr. Rynn has received grant support from Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and National Institute of Mental Health, research support from Eli Lilly and Company, National Institute of Mental Health, and Shire, and royalties from the American Psychiatric Association Publishing, Oxford University Press, and UpToDate.

Footnotes

Additional Information: MarketScan® Commercial Claims and Encounters Database is owned by Truven Health Analytics™ an IBM Company. Information on acquiring access to the database can be found at http://truvenhealth.com/

Previous presentation: Parts of this study were presented as an abstract at the American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology Annual Meeting, Scottsdale, AZ, May 30-June 3, 2016, the 10th Annual Chapel Hill Pharmaceutical Sciences Conferences, May 12–13, 2016, Chapel Hill, NC, and the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry’s 63rd Annual Meeting, October 24–29, 2016, New York, NY.

Potential conflicts of interest. Authors Dr. Bradley Gaynes and Dr. Stacie Dusetzina report no financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Merikangas KR, He J, Burstein M, et al. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in US adolescents: Results from the national comorbidity study-adolescent supplement (NCS-A). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49(10):980–989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beesdo K, Knappe S, Pine DS. Anxiety and anxiety disorders in children and adolescents: Developmental issues and implications for DSM-V. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2009;32(3):483–524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pine DS, Cohen P, Gurley D, Brook J, Ma Y. The risk for early-adulthood anxiety and depressive disorders in adolescents with anxiety and depressive disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55(1):56–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Birmaher B, Brent D, AACAP Work Group on Quality Issues, et al. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with depressive disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46(11):1503–1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zimmermann P, Wittchen HU, Höfler M, Pfister H, Kessler RC, Lieb R. Primary anxiety disorders and the development of subsequent alcohol use disorders: a 4-year community study of adolescents and young adults. Psychol Med. 2003;33(7):1211–1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dahne J, Banducci AN, Kurdziel G, MacPherson L. Early adolescent symptoms of social phobia prospectively predict alcohol use. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2014;75(6):929–936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Ameringen M, Mancini C, Farvolden P. The impact of anxiety disorders on educational achievement. J Anxiety Disord. 2003;17(5):561–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Connolly SD, Bernstein GA, Work Group on Quality Issues. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with anxiety disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46(2):267–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramsawh HJ, Chavira DA, Stein MB. Burden of anxiety disorders in pediatric medical settings: prevalence, phenomenology, and a research agenda. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164(10):965–972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.U.S. Burden of Disease Collaborators. The state of US health, 1990–2010: burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors. JAMA. 2013;310(6):591–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katzman MA. Aripiprazole: A clinical review of its use for the treatment of anxiety disorders and anxiety as a comorbidity in mental illness. J Affect Disord. 2011;128(Suppl 1):S11–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen JA, Bukstein O, Walter H, et al. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49(4):414–430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geller DA, March J, AACAP Committee on Quality Issues. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51(1):98–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bridge JA, Iyengar S, Salary CB, et al. Clinical response and risk for reported suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in pediatric antidepressant treatment: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2007;297(15):1683–1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strawn JR, Welge JA, Wehry AM, Keeshin B, Rynn MA. Efficacy and tolerability of antidepressants in pediatric anxiety disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Depress Anxiety. 2015;32(3):149–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ipser JC, Stein DJ, Hawkridge S, Hoppe L. Pharmacotherapy for anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009(3). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wehry AM, Beesdo-Baum K, Hennelly MM, Connolly SD, Strawn JR. Assessment and treatment of anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2015;17(7):52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rynn M, Puliafico A, Heleniak C, Rikhi P, Ghalib K, Vidair H. Advances in pharmacotherapy for pediatric anxiety disorders. Depress Anxiety. 2011;28(1):76–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leslie LK, Newman TB, Chesney PJ, Perrin JM. The Food and Drug Administration’s deliberations on antidepressant use in pediatric patients. Pediatrics. 2005;116(1):195–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Creswell C, Waite P, Cooper PJ. Assessment and management of anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. Arch Dis Child. 2014;99(7):674–678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walkup J, Labellarte M, Riddle MA, et al. Treatment of pediatric anxiety disorders: an open-label extension of the research units on pediatric psychopharmacology anxiety study. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2002;12(3):175–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Piacentini J, Bennett S, Compton SN, et al. 24- and 36-Week Outcomes for the Child/Adolescent Anxiety Multimodal Study (CAMS). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53(3):297–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC 2013.

- 24.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington DC 2000.

- 25.Bandelow B, Reitt M, Röver C, Michaelis S, Görlich Y, Wedekind D. Efficacy of treatments for anxiety disorders: a meta-analysis. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2015;30(4):183–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peters TE, Connolly S. Psychopharmacologic treatment for pediatric anxiety disorders. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2012;21(4):789–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Strawn JR, Prakash A, Zhang Q, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled study of duloxetine for the treatment of children and adolescents with generalized anxiety disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;54(4):283–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu CH, Wang CC, Katz AJ, Farley J. National trends of psychotropic medication use among patients diagnosed with anxiety disorders: Results from medical expenditure panel survey 2004–2009. J Anxiety Disord. 2013;27(2):163–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weisberg RB, Beard C, Moitra E, Dyck I, Keller MB. Adequacy of treatment received by primary care patients with anxiety disorders. Depress Anxiety. 2014;31(5):443–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Daviss WB, Barnett E, Neubacher K, Drake RE. Use of antipsychotic medications for nonpsychotic children: Risks and implications for mental health services. Psychiatr Serv. 2016;67(3):339–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with panic disorder, Second Edition. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fiks AG, Mayne SL, Song L, et al. Changing patterns of alpha agonist medication use in children and adolescents 2009–2011. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2015;25(4):362–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yoon EY, Clark SJ, Butchart A, Singer D, Davis MM. Parental preferences for FDA-approved medications prescribed for their children. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2011;50(3):208–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Singh T, Prakash A, Rais T, Kumari N. Decreased use of antidepressants in youth after US Food and Drug Administration black box warning. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2009;6(10):30–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Practice parameter on the use of psychotropic medication in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48(9):961–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Comer JS, Olfson M, Mojtabai R. National trends in child and adolescent psychotropic polypharmacy in office-based practice, 1996–2007. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49(10):1001–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Díaz-Caneja CM, Espliego A, Parellada M, Arango C, Moreno C. Polypharmacy with antidepressants in children and adolescents. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;17(7):1063–1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pine DS. Treating children and adolescents with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: how long is appropriate? J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2002;12(3):189–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bushnell GA, Stürmer T, White A, et al. Predicting persistence to antidepressant treatment in administrative claims data: Considering the influence of refill delays and prior persistence on other medications. J Affect Disord. 2016;196:138–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Whiteside SP, Ale CM, Young B, et al. The length of child anxiety treatment in a regional health system. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2016;47(6):985–992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Olfson M, Druss BG, Marcus SC. Trends in mental health care among children and adolescents. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(21):2029–2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chavira DA, Stein MB, Bailey K, Stein MT. Child anxiety in primary care: prevalent but untreated. Depress Anxiety. 2004;20(4):155–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Olfson M, Blanco C, Liu L, Moreno C, Laje G. National trends in the outpatient treatment of children and adolescents with antipsychotic drugs. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(6):679–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chirdkiatgumchai V, Xiao H, Fredstrom BK, et al. National trends in psychotropic medication use in young children: 1994–2009. Pediatrics. 2013;132(4):615–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Safer DJ, Rajakannan T, Burcu M, Zito JM. Trends in subthreshold psychiatric diagnoses for youth in community treatment. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(1):75–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.