Abstract

Objective:

This study was aimed at assessing socio-demographic and economic factors associated with nutritional status of adolescent school girls in Lay Guyint Woreda, Northwest Ethiopia.

Methods:

The school-based cross-sectional study comprising 362 adolescent girls aged 10–19 years was included in the study. Simple random sampling technique with proportional allocation to size was used to select the participants. An interviewer-administered questionnaire and anthropometric measurement were used to collect the data. An anthropometric measurement was converted to the indices of nutritional status using World Health Organization Anthro Plus software.

Result:

The overall prevalence of stunting and thinness among adolescent girls were 16.3% and 29%, respectively. Adolescents aged 14–15 years (AOR = 3.65; 95% confidence interval: 1.87, 7.11), adolescents living in rural areas (AOR = 1.34; 95% confidence interval: 1.24, 2.33), and adolescents who did not have snack (AOR = 11.39; 95% confidence interval: 1.47, 17.8) were positively associated with stunting. Whereas mother’s occupation was negatively associated with stunting (AOR = 0.12; 95% confidence interval: 0.17, 0.87). Similarly, being a rural resident (AOR = 2.40; 95% confidence interval: 1.13, 5.08) and adolescents aged 14–15 years (AOR = 6.05; 95% confidence interval: 2.15, 17.04) were positively associated with thinness. Educational status of adolescent girls was negatively associated with thinness (AOR = 0.13; 95% confidence interval: 0.05, 0.35).

Conclusion:

Stunting and thinness are prevalent among adolescent girls. The age of adolescents, place of residence, having a snack, and mother’s occupation was significantly associated with stunting and thinness. Having at least a one-time snack in addition to the usual diet is strongly recommended.

Keywords: Nutritional status, adolescents, girls, stunting, thinness, Ethiopia

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines adolescents as young people aged 10–19 years. Adolescence is a journey from the world of the child to the world of the adult.1 Adolescence can be divided into three stages. Early adolescence (10–13 years) is characterized by a spurt of growth and the beginnings of sexual maturation. In mid-adolescence (14–15 years), the main physical changes are completed, while the individual develops a stronger sense of identity. In later adolescence (16–19 years), the body fills out and takes its adult form.1 Adolescence is the only time following infancy when the rate of physical growth actually increases. For this to happen, there is a greater demand for calories and nutrients. Thus, it is a time of increased nutritional requirements.2 Poor nutrition can have lasting consequences on an adolescent’s cognitive development, resulting in decreased learning ability, poor concentration, and impaired school performance.3,4

Malnutrition in adolescence encompasses undernutrition as well as overnutrition.5 Undernutrition implies being underweight for one’s age, too short for one’s age (stunted), or deficient in vitamins and minerals.6 Long-term undernutrition is an important cause of stunting or short height-for-age.7 Many boys and girls in developing countries enter adolescence undernourished, making them more vulnerable to disease and early death. Girls constitute a more vulnerable group, especially in developing countries where they traditionally marry at an early age and are exposed to greater risk of reproductive morbidity and mortality.8 Studies show that many children in low- and middle-income countries enter adolescence stunted and thin. Many are also anemic, and there are also a wide variety of other micronutrient deficiencies.9

Nutrition-related deficiencies in Eastern African countries including Ethiopia are on par with Asian countries.10 The prevalence of wasting (thinness) among adolescent girls was 26% and 49.7% in two Bangladeshi studies,11,12 and 53.8% in India,13 respectively. Another study carried out in India showed that prevalence of underweight, stunting, and thinness among adolescent girls was found to be 32.8%, 19.5%, and 26.7%, respectively.14 In Turkey, the rates of being stunted, underweight, and overweight/obese were 4.4%, 5.0%, and 16.8%, respectively.15 Ethiopia has one of the highest rates of malnutrition in Sub-Saharan Africa and faces acute and chronic malnutrition and micronutrient deficiencies.16 Nutrition deficiencies at different childhood growth and developmental stages including adolescences are common in Ethiopia.17 Girls are vulnerable to stunting and wasting during adolescence because this period is characterized by a growth spurt including sexual development, maturation, and the onset of menarche. All of these factors cause an increased demand for nutrients and make girls vulnerable to malnutrition and are compounded by socio-demographic and economic factors.17,18

In Ethiopia, adolescent girls age 15–19 years (29%) are most likely to be thin (body mass index (BMI) below 18.5 kg/m2). Rural areas have a higher percentage of thin girls (25%) than in urban areas (15%). Conversely, the percentage of overweight or obese women is higher in urban areas (21%) than in rural areas (4%).19 Studies conducted in different regions of Ethiopia reveal that the overall prevalence of stunting among the adolescent girls is 15.5%,20 20.2%,21 12.2%,22 and 15%23 in Tehuledere, Arsi, Adwa, and Babli districts, respectively. Likewise, the prevalence of thinness varies across different regions of Ethiopia. The prevalence of thinness among adolescent girls was 21.6%, 28%, 21.4%, and 14.8% in studies conducted in Babille district,23 Bedlle,24 Adwa,22 and Arsi zone.21

Recently, socio-demographic factors and economic factors including adolescent’s age, mother’s age, eating habits, place of residence, income, parents’ occupation, literacy level, and cultural factors are associated with the nutritional status of adolescents.25–27 This is mainly due to nutrition, epidemiologic, and socio-demographic transition across the world.28,29 Socio-economic status was found to be associated with nutritional status of US adolescents.30 In a study conducted in Kenya, the level of maternal education was found to be associated with the nutritional status of children. This implies that the ability of mothers to care for their children is high among literate mothers.31 Nutritional status of the adolescent was low in both urban and rural adolescents, but severe thinness was higher among rural (39.3%) compared to urban (37.5%) adolescents in a study conducted in Babille district, Eastern Ethiopia.23

A significant association between malnutrition and socio-economic parameters was observed in a study conducted in Bangladesh. In this study, socio-economic status, maternal working status, family type, and family size were important determinants of nutritional status of adolescents.32 The prevalence of thinness was also 37.8% and 58.3% in a study conducted in the rural community of Tigray and Mekelle city.32,33 A study conducted in India, South Ethiopia, Ambo, Tigray, and Northwest Ethiopia revealed that age is independently associated with nutritional status of adolescent girls.13,24,34–36 Family size was also found to be another predictor of nutritional status of adolescents in a study conducted in Bangladesh and Southwest Ethiopia.12,24

In developing countries like Ethiopia, community culture is also associated with the nutritional status of girls.37 For example, girls in some societies are expected to feed last and feed least which increases nutritional needs during the adolescent stages yet again.38

Adolescent nutrition is given less attention to nutrition policies, strategies, and programs in low-income countries. Improved nutrition is the second of the Sustainable Development Goals. Moreover, targeting adolescent girls only when they are pregnant is often too late to break the intergenerational cycle of malnutrition.39 Despite the fact that the health sector (including the Ethiopian Ministry of Health) has increased its efforts to enhance good nutritional practices through health education, treatment of extremely malnourished children, and provision of micronutrients for mothers and children, malnutrition is still a challenge in the area.40

Lay Guyint is a woreda in the South Gondar Zone, Amhara Region, Ethiopia. The altitude of this woreda varies from 1500 to 3100 m above sea level. The main staple foods are potatoes, beans, peas, and barley. The annual rainfall is erratically distributed and varies from 400 to 1100 mm.30,41 In response to this, the purpose of this study was to explore the relationship between socio-demographic and/or economic factors and nutritional status of adolescent girls in high schools and preparatory schools in Lay Guyint Woreda, Northwest Ethiopia.

Materials and methods

Study area and period

The study was conducted in secondary and preparatory schools in Lay Guyint Woreda from 15 November to 15 December 2015. Lay Guyint Woreda is found at a distance of 711 km from the capital city of Ethiopia, Addis Ababa, and 175 km from the capital town of Amhara region, Bahir Dar city.

Ethical considerations

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Debre Tabor University. Following the approval, an official letter of cooperation was given to the school’s directors and homeroom teachers. Permission was obtained from the school’s directors prior to the study. The purpose and importance of the study were explained to the study participants and homeroom teachers (legally authorized representatives of the study participants). Overall data were collected only after fully written informed consent was sought from the homeroom teachers and verbal consent was obtained from study participants. All findings were kept confidential. The names and address of the participants were not recorded on the questionnaire.

Study design and participants

The institutional-based cross-sectional design was employed. The participants of the study were female adolescents in secondary and preparatory school who were randomly selected from all female adolescents (10–19 years old) in the Lay Guyint secondary and preparatory schools. From the selected participants, adolescent girls aged 10–19 years and available at the time of data collection were included in the study, and adolescent girls who had deformed anthropometric appearances and were seriously ill at the time of data collection were excluded from the study.

Sample size determination and sampling technique

The single proportion formula was used to determine the sample size by using a proportion of malnutrition in adolescent girls 31.5%36 and a confidence level of 95% with a 5% margin of error ((n = (Zα/2)2 p(1 – p)/d2); where, n = sample size, Zα / 2(1.96) = significance level at α = 0.05); p = expected prevalence or proportion of malnutrition in adolescents = 0.315, d = margin of error (5%) = 0.05 with a 10% non-response rate, the final sample size was 362. Simple random sampling technique with proportional allocation to size was employed to select the study participants. All secondary and preparatory schools in Lay Guyint Woreda were taken for this study. According to the Woreda Education Bureau report, the woreda has three secondary and one preparatory school with a total of 7285 students. Among them, 3727 are girls. There are 1958, 373, 568, and 828 girls in Nefasmewucha Secondary School, Zagot Secondary School, Sali Secondary School, and Nefasmewucha Preparatory School, respectively. So, when the 362 sample adolescent girls were divided proportionally, 190, 36, 55, and 81 girls were taken from Nefasmewucha, Zagot, and Sali Secondary Schools, and Nefasmewucha preparatory School, respectively.

Measurements and data collection techniques

A structured questionnaire was adapted from similar literature11,20–22 and modified to suit the local context and was used to collect data on socio-demographic characteristics, meal patterns, meal skipping, and frequency of meals. Nutritional status of study subjects was assessed by performing the anthropometric assessment. Two2 diploma nurses and two2 BSc nurses served as data collectors and supervisors, respectively. After the participants were selected by the inclusion criteria, the data were collected by face-to-face interviews and through conducting the anthropometric assessment.

Anthropometric measurement

Height and weight were measured using a stadiometer and Seca digital scale (Seca Germany). Weight was measured using a portable standing scale, which has the ability to measure weight from 0 to 150 kg. The weight was recorded to the nearest 0.1 kg. It was regularly calibrated against a known weight. During the procedure, the subjects wore light clothes and took off their shoes. Height was measured in cm using a portable stadiometer. All girls were measured against the wall without footwear and with heels together and their heads positioned and eyes looking straight ahead (Frankfurt plane) so that the line of sight was perpendicular to the body. The height was recorded to the nearest 0.1 cm. The same measurer was employed for a given anthropometric measurement to avoid variability. Stunting was defined as adolescent girls with height-for-age Z-score < –2 SD from the median value of WHO’s 2006 reference data.42 Thinness (wasting) was defined as adolescents with weight-for-height Z-score < –2 SD from the median value of WHO’s 2006 reference data.42

Data quality assurance and management

The data collectors and supervisors were trained intensively for 2 days about the purpose of the study, the sampling procedure, anthropometric measurement skills, and general approaches to the participants. Prior to data collection, the principal investigators shared ethical issues and ways of addressing contingency management skills. The English version of the questionnaire was translated by English linguistics to Amharic and again to English to ensure consistency. Anonymous data were checked for completeness every day by the supervisors and the principal investigators. All completed questionnaires were checked for completeness and cleaned manually.

Data processing and analysis

The questionnaires were coded and entered into EPI info version 3.5.3 statistical software and then exported to SPSS version 20 for Windows for further analysis. Data were summarized and presented using descriptive statistics. An anthropometric measurement was converted to the indices of nutritional status (the Z-scores of heights for age and BMI for age) using WHO Anthro Plus version 1.0.3 software.43 The anthropometric analysis determined the proportion of adolescents who were stunted (height-for-age Z-scores ⩽ –2 SD) and thin (BMI for age Z-score < –2 SD).43 The outcome variables were coded as “1” for having thinness or stunting whereas “0” for not having these problems. The association between the outcome variables (i.e. stunting and thinness) and independent variables were first analyzed using a bivariate logistic regression model. Covariates having a p-value < 0.25 were retained and entered into the multivariable logistic regression analysis using forward stepwise approach methods.44 The results are presented as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). A p-value < 0.05 was considered as a cut-off point for an independent variable to be significantly associated with the outcome.

Result

Socio-demographic characteristics of the study subjects

A total of 362 participants were interviewed yielding a response rate of 100%. The mean (SD) ages were 14.8 (±1.34) years. Of the participating adolescents, 281 (77.6%) were living in rural areas. Nearly all (98.1%) of the participants were Amhara by ethnicity, and 93.6% of them were Orthodox by religion. Concerning the educational status of the adolescent girls, most (62.7%) were in grades 11 and 12 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of adolescent girls in high schools and preparatory school of Lay Guyint Woreda, Northwest Ethiopia (n = 362), 2015.

| Variable | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Age of the adolescents (years) | ||

| 10–13 | 14 | 3.9 |

| 14–15 | 155 | 42.8 |

| 16–19 | 193 | 53.8 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 346 | 95.6 |

| Married | 16 | 4.4 |

| Religion | ||

| Orthodox | 340 | 93.6 |

| Muslim | 22 | 6.1 |

| Place of residence | ||

| Urban | 81 | 22.4 |

| Rural | 281 | 77.6 |

| Educational status of girls (grade) | ||

| 9–10 | 135 | 37.3 |

| 11–11 | 227 | 62.7 |

| Family monthly income (ETB) | ||

| <1000 | 224 | 61.9 |

| 1000–2000 | 54 | 14.9 |

| 2001–3000 | 67 | 18.5 |

| >3000 | 17 | 4.7 |

| Mother’s occupational status | ||

| Farmer | 279 | 77.1 |

| Government employee | 51 | 14.1 |

| Othera | 32 | 8.8 |

Merchant, student, daily laborer.

Dietary habit and food items consumed

Nearly all participants (97%) ate cereal-based foods for at least 5 days per week, while 9.7% ate vegetables for less than 5 days per week. Correspondingly, the majority (98%) of the participants had snacks. Two hundred sixty-four (72.9%) ate three times per day (Table 2).

Table 2.

Dietary habit and food items consumed by female adolescent girls in high school and preparatory schools of Lay Guyint Woreda, Northwest Ethiopia (n = 362), 2015.

| Variable | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Eating cereals | ||

| <5 days | 11 | 3.0 |

| ⩾5 days | 351 | 97.0 |

| Eating vegetables | ||

| <5 days | 327 | 90.3 |

| ⩾5 days | 35 | 9.7 |

| Eating fruits | ||

| <5 days | 353 | 97.5 |

| ⩾5 days | 9 | 2.5 |

| Eating animal-based foods | ||

| <5 days | 336 | 92.8 |

| ⩾5 days | 26 | 7.2 |

| Number of meals per day | ||

| 3 times | 264 | 72.9 |

| ⩾4 times | 98 | 7.2 |

| Having a snack | ||

| Yes | 356 | 98.3 |

| No | 6 | 1.7 |

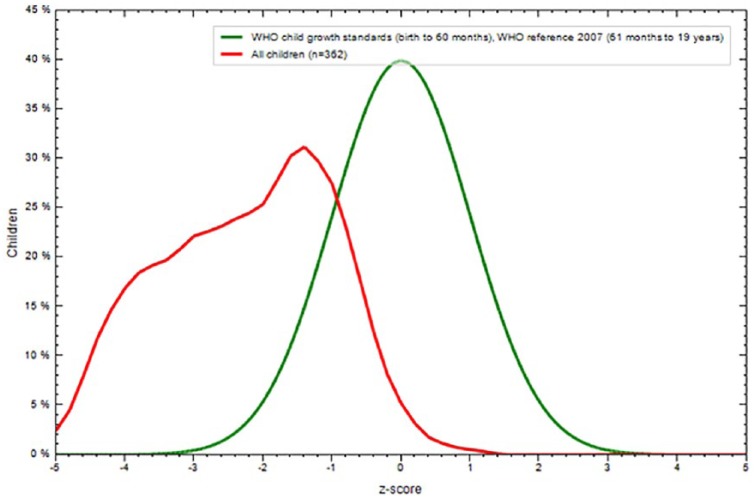

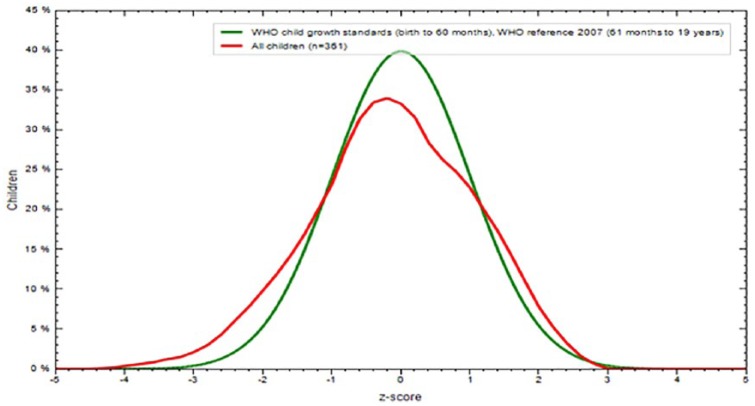

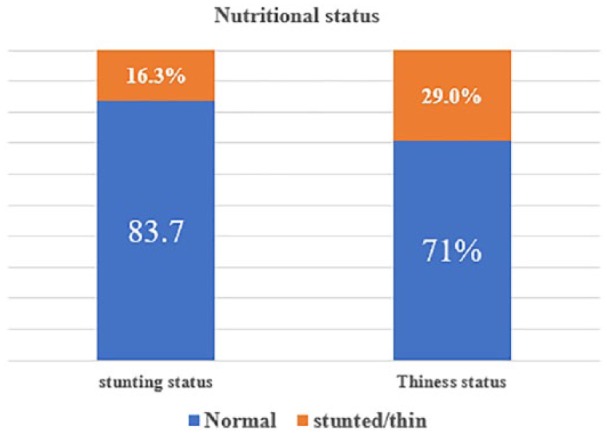

Prevalence of stunting and thinness

The overall prevalence of stunting and thinness were 16.3% (95% CI: 12.5%, 20.1%) and 29.0% (95% CI: 24.4%, 33.6%), respectively. The mean ± SD of the overall height of the participants was 156.46 ± 10.07 cm (95% CI: 146.5, 148.8) and weight was 44.01 ± 8.90 kg (95% CI: 36.2, 38.2). Height-for-age Z-scores and BMI for age Z-score of the participants were −0.95 (± 0.1.108) Z-score, and −0.10 (± 1.176), respectively, (Figures 1–3).

Figure 1.

Nutritional status of adolescent girls in high school and preparatory schools of Lay Guyint Woreda, Northwest Ethiopia (n = 362), 2015.

Figure 2.

Height for age Z-score comparison of WHO reference and adolescent school girls Northwest Ethiopia (n = 362), 2015.

Figure 3.

BMI for age Z-score comparison of WHO reference and adolescent school girls Northwest Ethiopia (n = 362), 2015.

Factors associated with the nutritional status of adolescent girls

In the multiple logistic regression, the age of adolescent girls, place of residence, having snacks, and mother’s occupational status were independently associated with stunting. Adolescents aged 14–15 years were 3.65 times more likely to be stunted (AOR = 3.65; 95% CI: 1.87, 7.11). Adolescents living in rural areas were 1.34 times more likely to be stunted (AOR = 1.34. 95% CI: 1.24, 2.33). Adolescents who did not have a snack were 11.39 times more likely to be stunted (AOR = 11.39; 95% CI: 1.47, 17.8). Mother’s occupation was negatively associated with stunting. The proportion of stunting was 88% less among adolescents whose mother’s occupation was merchant, student, or daily laborer (AOR = 0.12; 95% CI: 0.17, 0.87) (Table 3).

Table 3.

The association between stunting and its determinants among adolescent girls in secondary and preparatory school of Lay Guyint Woreda, Northwest Ethiopia (n = 362), 2015.

| Variables | Stunting status |

OR (95% CI) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | Stunted | COR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | |

| Age of the adolescents (years) | ||||

| 10–13 | 10 | 4 | 3.66 (1.047, 12.8) | 6.29 (1.59, 24.85) |

| 14–15 | 119 | 36 | 2.77 (1.51, 5.06) | 3.65 (1.87, 7.11)a |

| 16–19 | 174 | 19 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Place of residence | ||||

| Urban | 63 | 18 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Rural | 240 | 41 | 1.94 (1.28, 2.93) | 1.34 (1.24, 2.33)a |

| Occupational status of the mother | ||||

| Farmer | 225 | 54 | 0.67 (0.52, 1.71) | 0.34 (0.19, 2.71) |

| Government employee | 49 | 2 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Otherb | 29 | 3 | 0.46 (0.243, 0.88) | 0.120 (0.17, 0.87)a |

| Eating animal source foods | ||||

| <5 days | 287 | 49 | 0.27 (0.12, 0.63) | 0.25 (0.101, 0.66) |

| ⩾5 days | 16 | 10 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Number of meals per day | ||||

| 3 times | 218 | 46 | 1.38 (0.71, 2.68) | 0.23 (0.12, 1.22) |

| ⩾4 times | 85 | 13 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Having a snack | ||||

| Yes | 258 | 58 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| No | 41 | 5 | 9.07 (1.22, 24.67) | 11.39 (1.47, 17.1)a |

OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; COR: crude odds ratio; AOR: adjusted odds ratio.

Significantly associated with stunting.

Merchant, student, daily laborer.

Likewise, place of residence, age, mother’s occupational status, and educational status of adolescent girls were significantly associated with adolescent thinness on multivariable logistic regression. Rural residents had 2.40 times higher odds of being thin (AOR = 2.40; 95% CI: 1.13, 5.08) than urban adolescents. Adolescents aged 14–15 years were 6.05 times more likely to be thin (AOR = 6.05; 95% CI: 2.15, 17.04). The mother’s job was positively associated with thinness. An adolescent whose mother is a farmer has 5.27 times higher odds of being thin (AOR = 5.27; 95% CI: 5.41, 19.92). On the contrary, the educational status of adolescent girls was negatively associated with thinness. The proportion of thinness was 87% less among adolescents who were in grades 9 and 10 (AOR = 0.13; 95% CI: 0.05, 0.35) (Table 4).

Table 4.

The association between thinness and its determinants among adolescent girls in secondary and preparatory schools in Lay Guyint Woreda, Northwest Ethiopia (n = 362), 2015.

| Variables | Thinness status |

OR (95% CI) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | Thin | COR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | |

| Age of adolescent | ||||

| 10–13 | 5 | 9 | 6.09 (1.94, 19.13) | |

| 14–15 | 103 | 52 | 1.71 (1.06, 2.74) | 6.05 (2.14, 17.04)a |

| 16–19 | 149 | 44 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Place of residence | ||||

| Urban | 61 | 20 | 1.00 | |

| Rural | 196 | 85 | 1.32 (0.75, 2.32) | 2.402 (1.13, 5.08)a |

| Educational status of girls | ||||

| 9–10 | 106 | 29 | 0.54 (0.31, 0.89) | 0.132 (0.049, 0.355)a |

| 11–12 | 151 | 76 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Occupational status of mothers | ||||

| Farmer | 185 | 94 | 3.53 (1.20, 10.38) | 5.29 (1.406, 19.92)a |

| Government employee | 44 | 7 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Othersb | 28 | 4 | 1.14 (0.30, 4.25) | |

| Eating animal source foods | ||||

| >5 days | 241 | 95 | 0.63 (0.27, 1.43) | 1.09 (0.60, 1.99) |

| ⩾5 days | 16 | 10 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Number of meals per day | ||||

| 3 times | 183 | 81 | 1.36 (0.80, 2.31) | 0.92 (0.24, 3.52) |

| ⩾4 times | 74 | 24 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Having a snack | ||||

| Yes | 237 | 83 | 0.31 (0.165, 0.61) | 0.32 (0.54, 1.91) |

| No | 20 | 22 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

OR: odds ratios; CI: confidence interval; COR: crude odds ratio; AOR: adjusted odds ratio.

significantly associated with thinness.

merchant, student, daily laborer.

Discussion

The findings from this study show that 16.3% (95% CI: 12.5%, 20.1%) of adolescent girls were stunted. This finding is in line with a study conducted in Bible district, Eastern Ethiopia (15%),23 Tehuledere district (15.5%),20 and the Bangladeshi study (15.5%).11 But it is higher than the findings from Turkey (4.4%),15 Addis Ababa (7.2%),45 and Mozambique (2.3%).26 This is probably due to the difference in the socio-economic and socio-demographic characteristics since people in Turkey and Addis Ababa are higher than those in our study area in terms of socio-economic status. Nevertheless, it was lower than studies conducted in India (19.5%),46 Bangladesh (32%),12 two northern Ethiopia studies (28.5%)47 and (31.5%),36 and in Tigray (26.5%).35 This might be due to the variation in sample size, which increases the proportion of stunting.

Correspondingly, the findings from this study show that 29% (95% CI: 24.4%, 33.6%) of adolescent girls were thin. This finding is consistent with a study conducted in Bangladesh (26%),12 India (26.7%),48 and Northern Ethiopia (26.1%).47 However, the study is higher than studies conducted in Bible district, Eastern Ethiopia (21.6%);23 Benue State, Nigeria (11.5%);27 Adwa town (21.4%);22 Northwest Ethiopian study (13.6%);36 and low-income countries (6.3%).49 This might be due to the fact that there is a difference in barriers to undernutrition such as cultural differences and other socio-demographic characteristics. Still, it was lower than studies conducted in Tigray (37.8%);35 Kano, Northwestern Nigeria (60.6%);50 and Kashmir Valley (35%).51 This is possibly due to the difference in the study area and sample size. The study of Kano and Northern Ethiopia, and Kashmir Valley used a small sample size, which may have led to an increased estimation of the proportion of thinness. On the contrary, the Indian study was hospital-based which may have increased the prevalence of thinness (wasting) due to illness. Again, the study in Tigray was conducted in a rural area, which is predisposed to a high prevalence of thinness among adolescents.

In this study, an adolescent from rural areas was about 1.34 times more likely to be stunted. A study conducted in India,13 Ambo,34 and Babille district23 showed similar findings. This might be due to the low socio-economic/demographic characteristics of the rural residents as compared to urban dwellers. The findings also showed that adolescent age was significantly associated with stunting. Those adolescents aged 14–15 years were about four times more likely to be stunted as compared to early adolescents (10–13 years) and those aged 16–19 years. This finding is supported in studies conducted in Bangladesh,11 Tehuledere,20 two Northern Ethiopian studies,36,47 Mozambique,26 Ambo,34 South Ethiopian study,24 and Tigray.24 This could be due to the fact that this age group is characterized by a spurt of growth in which there is rapid physical, emotional, social, sexual, and psychological development, and maturation. About 20% of the total growth in stature and 50% of adult bone mass are achieved during the adolescent period. Consequently, the nutrient requirements are significantly increased as compared to those in childhood years. So, if the requirements and supply are not balanced, the adolescent girls may be exposed to stunting.52 Having a snack is also positively associated with stunting in adolescent girls. Those adolescents who did not have snack were about 11 times more likely to be stunted. This is probably due to the high requirement of nutrient needs during the adolescent period, which demands additional meal frequency in addition to the usual diet of breakfast, lunch, and dinner.53 However, mother’s occupation was negatively associated with stunting. The proportion of stunting was 88% less among adolescents whose mother’s job was merchant, student, or daily laborer. This might be due to the fact that mothers who are merchants, students, or daily laborers are always busy because of the nature of their job. Besides, such kinds of occupation may be predisposed to childhood stunting. As a result, adolescent height is also affected by pre-existing childhood stunting.54

Concerning the factors associated with thinness among adolescent girls, adolescents aged 14–15 years were about six times more likely to be thin as compared to other age groups. This might be due to the fact that adolescents in this age group are taking on adult roles, especially in developing countries like Ethiopia. Eating disorders are also common during the adolescent period, and this may predispose acute malnutrition such as stunting. Moreover, this age group is undergoing a growth spurt, so the physiological demand for macronutrients and micronutrients is high. Adolescent girls gain 20% of adult height and 50% of adult weight during the growth spurt leading to an increased BMI. But if they cannot get adequate food at this age, their BMI tends to decrease and they become thin.55

In this study, rural residents had about two times higher odds of being thin than urban adolescents. It could be surmised that rural areas are more prone to hygiene-related diseases; for example, poor sources of water may lead to malnutrition (thinness). Moreover, rural adolescents and their parents may have poor knowledge of dietary diversity.56 The mother’s occupational status was also significantly associated with thinness. Adolescents whose mothers were farmers had five times higher odds of being thin as compared to the other occupational status, such as government employer, merchant, student, and daily laborer. This could be due to the fact that a lack of knowledge about diet and social factors such as food taboos are common among the Ethiopian farmers, and mothers are also part of this community. Besides, most of the farmers in the Ethiopian communities have food insecurity, inadequate social and care environment, and inadequate access to health services and environmental factors, such as poor water and sanitation facilities. All these are the underlying causes of malnutrition across different age groups of childhood and adolescents.57 On the contrary, the educational status of adolescent girls was negatively associated with thinness. The proportion of thinness was 87% less among adolescents who were in grades 9 and 10 as compared to those who were in grades 11 and 12. This could be explained by the idea that the nutrition-related knowledge and attitude in the school needs emphasis as part of adolescent care.1

However, the present study does have some inherent limitations. Due to the lack of available food list by considering seasonal variation, the detailed dietary assessment as a complement of anthropometric measurements was not included. It also lacks a laboratory nutritional assessment of adolescents due to financial constraints. Furthermore, the direction of the association between socio-demographic and/or economic factors varies from location to location. Therefore, extrapolating these results to other rural populations in Ethiopia may be difficult.

Conclusion

The study suggested that stunting and thinness are prevalent among adolescent girls in secondary and preparatory schools in Lay Guyint Woreda. The age of adolescents, place of residence, and having a snack was positively associated with stunting. Likewise, the age of adolescents, place of residence, and mother’s job was positively associated with the thinness of adolescent girls. Girls may be at significantly higher risk of malnutrition due to different socio-demographic and economic factors. As girls are future mothers, this may have a negative effect that perpetuates the intergenerational cycle of malnutrition. Therefore, more attention should be given to those adolescents aged 14–15 years during this adolescent growth spurt period. Having a snack at least one time in addition to the usual diet is strongly recommended. For researchers, carefully designed longitudinal studies are needed to identify the reasons for poor growth throughout the period of adolescence in this population.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our heartfelt gratitude to Debre Tabor University, College of Health Sciences, for giving us this chance through nonfinancial support. We would like to extend our deepest gratitude to the study participants and the data collectors. Our gratitude also goes to Lay Guyint Woreda Education Office for their provision of information about the study area.

Footnotes

Author contributions: G.A. designed the study, performed the statistical analysis, and drafted the manuscript. M.A. and T.W. participated in the study design and statistical analysis. T.W. and M.A. drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed their intellectual inputs, and read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: Ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Debre Tabor University (ref. no. DTU/RP/188/15). Following the approval, an official letter of cooperation was given to the school’s directors and homeroom teachers.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The authors receive financial support from Debre Tabor University, College of Health Sciences, for the research and authorship but not for publication of the article.

Informed consent: After the approval of the study by the Institutional Review Board, permission was obtained from the school’s directors prior to the study. The purpose and importance of the study were explained to the study participants and homeroom teachers (can act as legally authorized representatives of the students in the school). Meanwhile, there are no handy list of substitutes that can be relied on with certitude. Overall data were collected only after fully written informed consent was sought from the homeroom teachers and verbal consent was obtained from study participants without pressure from the homeroom teachers or investigators. All findings were kept confidential. The names and address of the participants were not recorded on the questionnaire.

ORCID iD: Teshager Worku  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6153-7819

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6153-7819

References

- 1. World Health Organization (WHO). Adolescent friendly health services: an agenda for change. Geneva: WHO, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 2. United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). The state of the World’s children 2011: adolescence—an age of opportunity. New York: UNICEF, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shelomenseff D, Andreoni J. California nutrition and physical activity guidelines for adolescents, 2000, https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/CFH/DMCAH/CDPH%20Document%20Library/NUPA/NUPA-Guidelines-Adolescents.pdf

- 4. Abahussain NA. Was there a change in the body mass index of Saudi adolescent girls in Al-Khobar between 1997 and 2007? J Family Community Med 2011; 18(2): 49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Black RE, Victora CG, Walker SP, et al. Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 2013; 382(9890): 427–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cole TJ. Weight-stature indices to measure underweight, overweight, and obesity. In:Himes JH. (ed.) Anthropometric assessment of nutritional status. New York: Wiley, 1991, pp. 83–111. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Coly AN, Milet J, Diallo A, et al. Preschool stunting, adolescent migration, catch-up growth, and adult height in young Senegalese men and women of rural origin. J Nutr 2006; 136(9): 2412–2420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bhattacharyya H, Barua A. Nutritional status and factors affecting nutrition among adolescent girls in urban slums of Dibrugarh, Assam. Natl J Community Med 2013; 4(1): 35–39. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Thurnham DI. Nutrition of adolescent girls in low-and-middle-income countries. Sight Life 2013; 27(3): 26–37. [Google Scholar]

- 10. World Health Organization (WHO). Adolescent nutrition: a review of the situation in selected South-East Asian countries. Geneva: WHO, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hossain G, Sarwar MT, Rahman MH, et al. A study on the nutritional status of the adolescent girls at Khagrachhari district in Chittagong hill tracts, Bangladesh. Am J Life Sci 2013; 1(6): 278–282. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Alam N, Roy SK, Ahmed T, et al. Nutritional status, dietary intake, and relevant knowledge of adolescent girls in rural Bangladesh. J Health Popul Nutr 2010; 28(1): 86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Deshmukh P, Gupta S, Bharambe M, et al. Nutritional status of adolescents in rural Wardha. Indian J Pediatr 2006; 73(2): 139–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Singh J, Kariwal P, Gupta S, et al. Assessment of nutritional status among adolescents: a hospital-based cross-sectional study. Int J Res Med Sci 2017; 2(2): 620–624. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Özgüven I, Ersoy B, Özguven AA, et al. Evaluation of nutritional status in Turkish adolescents as related to gender and socioeconomic status. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol 2010; 2(3): 111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ethiopia Mini Demographic and Health Survey (EMDHS). Ethiopia mini demographic and health survey. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Central Statistical Agency, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Salam RA, Das JK, Lassi ZS, et al. Adolescent health and well-being: background and methodology for review of potential interventions. J Adolesc Health 2016; 59(Suppl. 4): S4–S10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Delisle H. Nutrition in adolescence: issues and challenges for the health sector: issues in adolescent health and development. Geneva: WHO, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Federal Ministry of Health (FMoH). Ethiopia demographic and health survey 2016. 2016, https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR328/FR328.pdf

- 20. Woday A, Menber Y, Tsegaye D. Prevalence of and associated factors of stunting among adolescents in Tehuledere District, North East Ethiopia, 2017. J Clin Cell Immunol 2018; 9(2): 546. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yemaneh Y, Girma A, Nigussie W, et al. Undernutrition and its associated factors among adolescent girls in the rural community of Aseko district, Eastern Arsi Zone, Oromia region, Eastern Ethiopia, 2017. INT J CLIN Obstet Gynaecol 2017; 1(2): 17–26. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gebregyorgis T, Tadesse T, Atenafu A. Prevalence of thinness and stunting and associated factors among adolescent schoolgirls in Adwa Town, North Ethiopia. Int J Food Sci 2016; 2016: 8323982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Teji K, Dessie Y, Assebe T, et al. Anaemia and nutritional status of adolescent girls in Babile District, Eastern Ethiopia. Pan Afr Med J 2016; 24: 62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wolde T, Mekonnin WAD, Yitayin F, et al. Nutritional status of adolescent girls living in Southwest of Ethiopia. Food Sci Qual Manag 2014; 34: 58–64. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Maiti S, Chatterjee K, Ali KM, et al. Assessment of nutritional status of rural early adolescent school girls in Dantan-II Block, Paschim Medinipur District, West Bengal. Natl J Community Med 2011; 2(115): 14–18. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Prista A, Maia JAR, Damasceno A, et al. Anthropometric indicators of nutritional status: implications for fitness, activity, and health in school-age children and adolescents from Maputo, Mozambique. Am J Clin Nutr 2003; 77(4): 952–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Musa DI, Toriola AL, Monyeki MA, et al. Prevalence of childhood and adolescent overweight and obesity in Benue State, Nigeria. Trop Med Int Health 2012; 17(11): 1369–1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lee R. The demographic transition: three centuries of fundamental change. J Econ Perspect 2003; 17(4): 167–190. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Amuna P, Zotor FB. Epidemiological and nutrition transition in developing countries: impact on human health and development. P Nutr Soc 2008; 67(1): 82–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Goodman E. The role of socioeconomic status gradients in explaining differences in US adolescents’ health. Am J Public Health 1999; 89(10): 1522–1528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kabubo-Mariara J, Ndenge GK, Mwabu DK. Determinants of children’s nutritional status in Kenya: evidence from demographic and health surveys. J Afr Econ 2008; 18(3): 363–387. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tamanna S, Rana MM, Ferdoushi A, et al. Assessment of nutritional status among adolescent Garo in Sherpur District, Bangladesh. Bangladesh J Med Sci 2013; 12(3): 269–275. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gebremariam H, Seid O, Assefa H. Assessment of nutritional status and associated factors among school-going adolescents of Mekelle City, Northern Ethiopia. Int J Food Sci Nutr 2015; 4: 118–124. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Alemayehu T, Haidar J, Habte D. Adolescents’ undernutrition and its determinants among in-school communities of Ambo Town, West Oromia, Ethiopia. East Afr J Public Health 2010; 7(3): 263–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mulugeta A, Hagos F, Stoecker B, et al. Nutritional status of adolescent girls from rural communities of Tigray, Northern Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev 2009; 23(1): 5–11. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wassie MM, Gete AA, Yesuf ME, et al. Predictors of nutritional status of Ethiopian adolescent girls: a community-based cross-sectional study. BMC Nutr 2015; 1(1): 20. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sujoldžić A, De Lucia A. A cross-cultural study of adolescents—BMI, body image and psychological well-being. Coll Antropol 2007; 31(1): 123–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Black RE, Allen LH, Bhutta ZA, et al. Maternal and child undernutrition: global and regional exposures and health consequences. Lancet 2008; 371(9608): 243–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. United Nations Administrative Committee on Coordination, Subcommittee on Nutrition (UNACC/SCN) and International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI). 4th report on the world nutrition situation: nutrition throughout the life cycle. Geneva: UNACC/SCN, 2000, https://www.unscn.org/web/archives_resources/files/rwns4.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kennedy E, Tessema M, Hailu T, et al. Multisector nutrition program governance and implementation in Ethiopia: opportunities and challenges. Food Nutr Bull 2015; 36(4): 534–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wikipedia. Lay Guyint (Amharic “Upper Guyint”) demographics, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lay_Gayint

- 42. WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group (WMGRS) and de Onis M. WHO Child Growth Standards based on length/height, weight, and age. Acta Paediatr Suppl 2006; 95(Suppl. 450): 76–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. World Health Organization (WHO). WHO AnthroPlus for personal computers manual: software for assessing the growth of the world’s children and adolescents. Geneva: WHO, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hosmer D. Exact methods for logistic regression models. In: Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. (eds) Applied logistic regression. New York: Wiley, 2000, pp. 330–338. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gebreyohannes Y, Shiferaw S, Demtsu B, et al. Nutritional status of adolescents in selected government and private secondary schools of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Adolescence 2014; 10: 11. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Anand K, Kant S, Kapoor S. Nutritional status of adolescent school children in rural north India. Indian Pediatr 1999; 36: 810–816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Melaku YA, Zello GA, Gill TK, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with stunting and thinness among adolescent students in Northern Ethiopia: a comparison to World Health Organization standards. Arch Public Health 2015; 73: 44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Venkaiah K, Damayanti K, Nayak M, et al. Diet and nutritional status of rural adolescents in India. Eur J Clin Nutr 2002; 56(11): 1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Candler T, Costa S, Heys M, et al. Prevalence of thinness in adolescent girls in low-and-middle-income countries and associations with wealth, food security, and inequality. J Adolesc Health 2017; 60(4): 447–454.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Mijinyawa MS, Yusuf SM, Gezawa ID, et al. Prevalence of thinness among adolescents in Kano, Northwestern Nigeria. Niger J Basic Clin Sci 2014; 11(1): 24. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ali D, Shah RJ, Fazili AB, et al. A study on the prevalence of thinness and obesity in school going adolescent girls of Kashmir Valley. Int J Community Med Public Health 2016; 3(7): 1884–1893. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Golden NH, Abrams SA. Optimizing bone health in children and adolescents. Pediatrics 2014; 134: e1229–e1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Neumark-Sztainer D, Hannan PJ, Story M, et al. Family meal patterns: associations with sociodemographic characteristics and improved dietary intake among adolescents. J Am Diet Assoc 2003; 103(3): 317–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ukwuani FA, Suchindran CM. Implications of women’s work for child nutritional status in sub-Saharan Africa: a case study of Nigeria. Soc Sci Med 2003; 56(10): 2109–2121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Alberga A, Sigal R, Goldfield G, et al. Overweight and obese teenagers: why is adolescence a critical period? Pediatr Obes 2012; 7(4): 261–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Story M, Resnick MD. Adolescents’ views on food and nutrition. J Nutr Educ 1986; 18(4): 188–192. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Petrou S, Kupek E. Poverty and childhood undernutrition in developing countries: a multi-national cohort study. Soc Sci Med 2010; 71(7): 1366–1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]