Abstract

The 1,2,3-triazole has been successfully utilized as an amide bioisostere in multiple therapeutic contexts. Based on this precedent, triazole analogs derived from VX-809 and VX-770, prominent amide-containing modulators of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR), were synthesized and evaluated for CFTR modulation. Triazole 11, derived from VX-809, displayed markedly reduced efficacy in F508del-CFTR correction in cellular TECC assays in comparison to VX-809. Surprisingly, triazole analogs derived from potentiator VX-770 displayed no potentiation of F508del, G551D, or WT-CFTR in cellular Ussing chamber assays. However, patch clamp analysis revealed that triazole 60 potentiates WT-CFTR similarly to VX-770. The efficacy of 60 in the cell-free patch clamp experiment suggests that the loss of activity in the cellular assay could be due to the inability of VX-770 triazole derivatives to reach the CFTR binding site. Moreover, in addition to the negative impact on biological activity, triazoles in both structural classes displayed decreased metabolic stability in human microsomes relative to the analogous amides. In contrast to the many studies that demonstrate the advantages of using the 1,2,3-triazole, these findings highlight the negative impacts that can arise from replacement of the amide with the triazole and suggest that caution is warranted when considering use of the 1,2,3-triazole as an amide bioisostere.

Keywords: triazole, bioisostere, CFTR, corrector, potentiator

Graphical Abstract

Trying out the triazole as an amide bioisostere in CFTR modulators VX-809 and VX-770 revealed that triazole derivatives of VX-809 and VX-770 displayed significantly decreased efficacy or inactivity in cellular assays. In addition, triazole derivatives displayed decreased metabolic stability in hepatic microsomal assays. These findings represent an important counterpoint to the many successful uses of the triazole as an amide bioisostere.

Introduction

Since the development of efficient synthetic methodologies to prepare 1,2,3-triazoles in the early 2000’s,[1] the use of the 1,2,3-triazole as an amide bioisostere has proven to be a widely successful strategy in medicinal chemistry.[2–5] As shown in Figure 1, the basis of the effective bioisosteric relationship is due to the similar topological and electronic characteristics of the 1,4-disubstituted 1,2,3-triazole and the trans-amide. Substituents located at the 1-and 4-positions of the triazole are separated by ~5.0 to 5.1 Å, which is close to the ~3.8 to 3.9 Å distance between the amide substituents.[3] The triazole also exhibits similar H-bonding capabilities to the amide, with the triazole N3 serving as an H-bond acceptor in an analogous spatial location to the amide carbonyl.[6] Furthermore, due to the substantial dipole moment of the triazole ring calculated to be ~5 Debye,[5] the C5 hydrogen atom of the triazole has been demonstrated to be capable of functioning as an H-bond donor that occupies a comparable position to the amide hydrogen atom.[7]

Figure 1.

Bioisosteric relationship of 1,4-disubstituted 1,2,3-triazoles and trans-amides. A) Similar R1-R2 distance and arrangement of H-bond donor and acceptor groups in the trans-amide and 1,2,3-triazole. Adapted from references [3] and [4]. B) Overlay of trans-N-methylacetamide and 1,4-dimethyl-1H-1,2,3-triazole in which the amide carbonyl carbon and nitrogen atom are aligned with C4 and C5 of the 1,2,3-triazole.

Impressively, numerous successful applications of the 1,2,3-triazole as an amide bioisostere have been reported as recently reviewed by Passarella and coauthors.[2] These examples span diverse therapeutic contexts including antiviral agents,[8] chemotherapeutics,[9–11] antibiofilm agents,[12] anti-nociceptives,[13] and antipsychotics.[14] Advantageously, use of the 1,2,3-triazole in place of the amide often affords increased biological activity, as demonstrated for viral infectivity factor (Vif) inhibitors 1 and 2 (Figure 2).[8] In this example, the potency of amide 1 (IC50 = 6 μM) was improved substantially in triazole 2 (IC50 = 1.2 μM). Furthermore, the discovery that the triazole could be substituted for the amide enabled use of the Cu-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC) reaction to rapidly discover highly potent triazole-containing inhibitor 3 (IC50 = 10 nM).[8] In addition to CuAAC, the triazole linkage also opens the door to the use of target-guided in situ click chemistry (isCC)[15] to probe protein binding sites and discover new chemical scaffolds. For example, the discovery that the amide in imatinib (4) could be substituted with the 1,2,3-triazole[9] led to further studies demonstrating that the Abl protein could assemble triazole inhibitor 5 from click fragments 6 and 7 in situ, making possible the use of the isCC strategy for the discovery of new classes of Abl inhibitors.[10] Finally, in addition to enabling rapid analog exploration using CuAAC or isCC, substitution with the 1,2,3-triazole has also been demonstrated to improve physiochemical properties such as aqueous solubility[13] and metabolic stability.[14]

Figure 2.

Use of the 1,2,3-triazole as an amide bioisostere allows use of CuAAC or isCC to optimize and/or discover new chemical scaffolds.

Due to the widespread success of the 1,2,3-triazole as an amide bioisostere, we sought to evaluate the utility of this bioisosteric replacement within amide-containing small molecule modulators of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) protein. CFTR is a member of the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter superfamily and is comprised of two membrane spanning domains (MSD1, MSD2), two nucleotide binding domains (NBD1, NBD2), and a regulatory domain that controls protein function via PKA-dependent phosphorylation.[16] CFTR functions as a Cl− and HCO3− ion channel and plays an essential role in fluid homeostasis across epithelial cells in the lungs, pancreas, intestines, reproductive tract, and sweat glands.[17] Mutations to the CFTR ion channel are the causative factor for the devastating disease Cystic Fibrosis (CF).[18,19]

While ~2,000 CFTR mutations have been identified,[20] deletion of phenylalanine 508 (F508del) from NBD1 is the most prominent CFTR mutation, with ~90% of CF patients carrying at least one F508del-CFTR allele.[21] The F508del mutation has especially severe consequences for protein stability and function. First, deletion of phenylalanine 508 destabilizes the NBD1 domain and disrupts key domain-domain interactions between NBD1 and intracellular loop 4 (ICL4) of MSD2.[22] This combination of structural defects impairs F508del-CFTR folding, leading to significant ubiquitin-proteasomal degradation and low levels of F508del-CFTR expression in the apical membrane of epithelial cells.[23] Exacerbating the problem, F508del-CFTR also exhibits a decreased half-life at the plasma membrane[24] and a gating defect in which Cl− transport is impaired due to a decreased open probability (Po) of the channel.[24–26] These combined deficiencies result in CFTR mediated Cl− secretion in human bronchial epithelial (HBE) cells derived from patients homozygous for F508del-CFTR that is only ~3–4% of that observed in non-CF epithelia.[24,27] Diminished Cl− transport in CF patients results in dehydration of the airway surfaces, which concurrently leads to decreases in ciliary beat frequency and mucociliary clearance causing the buildup of thick mucus within the lungs.[28] This mucus harbors harmful bacterial pathogens, leading to chronic lung infection and hyperinflammation that severely damage the lungs and ultimately causes lung failure, the primary cause of death in CF patients.

Groundbreaking work by Vertex Pharmaceuticals and others has identified small molecule modulation of mutant forms of CFTR as a revolutionary strategy to combat CF.[16,18,19,29] CFTR modulators are grouped into two categories—potentiators and correctors. Potentiators increase Cl− ion transport by counteracting the gating defect in the mutant protein while correctors counteract folding deficiencies to increase expression of the protein. Modulators in both classes have gained FDA approval.[19, 29] Potentiator VX-770 (Ivacaftor, Figure 3) has been approved for a number of gating mutations, and the combination of VX-770 with VX-809 (Lumacaftor, Figure 3) is approved to treat the F508del mutation that disrupts protein folding and channel gating. Recently, the combination of Ivacaftor with the second-generation corrector VX-661 (Tezacaftor, Figure 3), which exhibits an improved safety profile over VX-809, was also approved to treat patients with the F508del mutation.

Figure 3.

Structures of potentiator VX-770 and correctors VX-809 and VX-661.

Despite the recent breakthroughs in CF therapy, the search for improved CFTR modulators remains a priority.[19] Given the presence of the amide linkage in both VX-809 and VX-770, the detailed pharmacological characterization of these modulators reported in the primary literature,[24,27] and the promise of the triazole as an amide bioisostere, we investigated the suitability of the 1,2,3-triazole bioisosteric replacement within the VX-809 and VX-770 structural classes. Importantly, demonstration that the triazole substitution is tolerated in these molecular scaffolds would provide a starting point for future studies aimed at generating improved classes of modulators using CuAAC or isCC strategies. Herein, we report the synthesis and biological evaluation of 1,2,3-triazole analogs of CFTR modulators within the VX-809 and VX-770 structural classes.

Results and Discussion

Design of 1,2,3-Triazole Analogs in the VX-809 Structural Class

Among F508del-CFTR correctors, the benzo[d][1,3]dioxole cyclopropane carboxamide moiety has been maintained as an essential structural feature across otherwise diverse chemical scaffolds, suggesting that this moiety is a key pharmacophore for corrector efficacy. As seen in the comparison of VX-809, VX-661, corrector 8 reported by AbbVie Pharmaceuticals (Figure 4A),[30] and the widely employed tool compound C18 (VRT-534, Figure 4A),[31,32] considerable structurally variability is tolerated within the amide nitrogen substituent provided that the benzo[d][1,3]dioxole cyclopropane carboxamide moiety is present. On the basis of this observation, we hypothesized that CuAAC or isCC methods using 2,2-difluorobenzo[d][1,3]dioxole cyclopropane alkyne 9 (Figure 4B) have strong potential to develop a new class of correctors, if the 2,2-difluorobenzo[d][1,3]dioxole cyclopropane 1,2,3-triazole can serve as a suitable pharmacophore for F508del-CFTR correction. To investigate this question, we targeted the synthesis of 1,2,3-triazole containing corrector 11 shown in Figure 4B, which is a close structural analog of amide-containing VX-809.

Figure 4.

A) Structure of corrector 8[30] and C18 (VRT-534)[31,32] bearing the benzo[d][1,3]dioxole cyclopropane carboxamide pharmacophore. B) Targeted alkyne 9 and azide 10 to explore the viability of the 2,2-difluorobenzo[d][1,3]dioxole cyclopropane 1,2,3-triazole pharmacophore. C) 2-azidopyridine and tetrazole tautomers. D) Targeted alkyne 12 to investigate the importance of the 2,2-difluorobenzo[d][1,3]dioxole moiety for corrector efficacy.

In addition to the 1,2,3-triazole substitution, 11 differs from VX-809 in that it contains a central phenyl ring in contrast to the pyridine found in VX-809. This modification was made to prevent challenges associated with the use of 2-azidopyridines in azide-alkyne cycloaddition reactions due to the unfavorable equilibrium between 2-azidopyridines and the corresponding tetrazole tautomer (Figure 4C).[33] In addition to alkyne 9 we also targeted the synthesis of alkyne 12 containing the 4-methoxyphenyl group in order to gain insight into the importance of the 2,2-difluorobenzo[d][1,3]dioxole moiety for corrector efficacy. The 4-methoxyphenyl moiety was selected from the VX-809 patent literature as it appeared to display efficacy in F508del-CFTR correction[34] and was readily accessible synthetically. We hypothesized that 12 might also be a useful building block for CuAAC or isCC medicinal chemistry efforts.

Synthesis of 1,2,3-Triazole Analogs in the VX-809 Structural Class

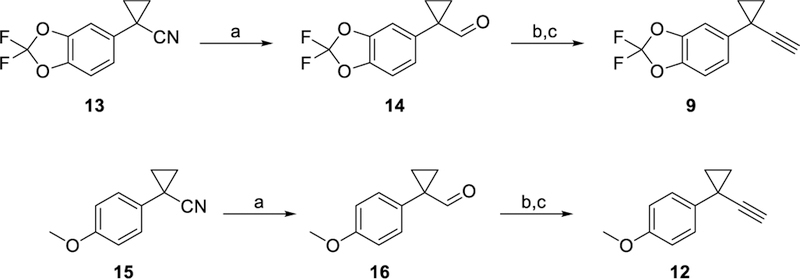

Alkynes 9 and 12 were prepared from the corresponding nitriles as shown in Scheme 1. Treatment of nitrile 13 with DIBALH at −78 °C followed by quenching with 3 M HCl produced aldehyde 14 in 89% yield. Corey-Fuchs alkynylation using CBr4 and Ph3P, followed by treatment of the dibromoolefin intermediate with nBuLi produced targeted alkyne 9 in 60% yield over two steps. Preparation of alkyne 12 from nitrile 15 was accomplished in the same manner, with the Corey-Fuchs reaction proving more efficient for this substrate as 12 was produced in 81% yield over two steps.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of Alkynes 9 and 12. Reagents and conditions: a) (i) DIBALH, toluene, −78 °C, 3 h; (ii) HCl, 0 °C, 15 min, 14: 89%, 16: 88%; b) CBr4, PPh3, CH2Cl2, 0 °C, 1 h; c) nBuLi (2.2 equiv) THF, −78 °C, 1.5 h, 9: 60% over 2 steps, 12: 81% over 2 steps.

Synthesis of the azide 10 was also accomplished in a straightforward manner as shown in Scheme 2. Suzuki coupling of 3-bromo-4-methylaniline with boronic acid 18 produced biaryl 19 in 98% yield. TFA-mediated deprotection of tert-butyl ester 19, followed by diazotization with sodium nitrite and substitution of the aryl diazonium intermediate with sodium azide, produced azide 10 in 92% yield over the two-step sequence. With the targeted alkyne and azide intermediates in hand we then performed the Cu-mediated azide-alkyne cycloaddition using standard reaction conditions to produce triazoles 11 and 20 in quantitative yield.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of Azide 10 and 1,2,3-Triazole-Containing Correctors 11 and 20. Reagents and conditions: (a) Pd(dppf)Cl2•CH2Cl2, K2CO3, toluene/H2O (3:1), reflux, 20 h, 98%; (b) TFA, CH2Cl2, 0 °C to rt, 2 h; (c) (i) EtOAc, HCl, 0 °C, 5 min; (ii) NaNO2, H2O, 0 °C, 1 h; (iii) NaN3, H2O, 0 °C to rt, 3 h; 92% over 2 steps; (d) 9 or 12, CuSO4•5H2O, sodium ascorbate, CH2Cl2/tBuOH/H2O (1:2:2), rt, 24 h, 11: 100%, 20: 100%.

To enable the direct comparison of triazoles 11 and 20 to their analogous amides, amides 23 and 26 were prepared as shown in Scheme 3. HATU-mediated coupling of carboxylic acids 21 and 24 with aniline 19 produced the corresponding amides in excellent yield. Removal of the tert-butyl ester with TFA quantitatively produced amide analogs 23 and 26.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of Amide-Containing Correctors 23 and 26. Reagents and conditions: (a) 19, HATU, Et3N, DMF, rt, 24 h, 22: 99%, 25: 96%; (b) TFA, CH2Cl2, 0 °C to rt, 2 h, 23: 100%, 26: 99%.

Finally, in order to fully understand the effect of the replacement of the pyridyl ring in the VX-809 scaffold with the phenyl ring in amides 23/26 and 1,2,3-triazoles 11/20, we prepared pyridyl-containing corrector 33 as shown in Scheme 4. Following the synthetic procedure reported for this class of correctors in the patent literature,[35] Suzuki coupling of 2-bromo-3-methylpyridine with boronic acid 18 first produced 28 in high yield which was then quantitatively converted to N-oxide 29 via treatment with mCPBA. Amination via reaction with Ms2O and pyridine in MeCN at 70 °C for 1.5 h, followed by treatment with ethanolamine yielded 2-aminopyridine 30 in 53% yield. Preparation of acid chloride 31 from carboxylic acid 24 using SOCl2, and reaction with amine 30 produced amide 32 which contained the pyridyl core. Finally, hydrolysis of the tert-butyl ester using TFA afforded 33, the 4-methoxyphenyl analog of VX-809, in 77% yield.

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of Corrector 33. Reagents and conditions: (a) 18, Pd(dppf)Cl2•CH2Cl2, K2CO3, toluene/H2O, reflux, 18 h, 92%; (b) mCPBA, CH2Cl2, rt, 24 h, 99%; (c) (i) Ms2O, pyridine, MeCN, 70 °C, 1.5 h; (ii) ethanolamine, rt, 2 h, 53% (d) SOCl2, toluene, 60 °C, 2 h. (e) iPr2EtN, DMAP, CH2Cl2, rt, 18 h, 56%; (f) TFA, CH2Cl2, 0 °C to rt, 2 h, 77%.

In vitro Evaluation of 1,2,3-Triazole Analogs in the VX-809 Structural Class

1,2,3-triazole-containing correctors 11 and 20, amide-containing correctors 23 and 26 containing the central phenyl ring, and the amide-containing corrector 33 bearing the central pyridine were evaluated in transepithelial chloride conductance (TECC) assays using F508del CFBE41o− monolayers. The F508del CFBE41o− cell line is an immortalized cell line derived from bronchial epithelial cells of a CF patient homozygous for the F508del CFTR mutation with complementary stable F508del-CFTR transgene expression,[36] and has been shown to be clinically relevant in characterizing small molecule CFTR modulators.[37,38] Prior to TECC experiments, F508del CFBE41o− monolayers were incubated (24 h) with varying concentrations of corrector compound to increase functional F508del-CFTR present at the apical membrane as a result of corrector-assisted protein folding. Increased CFTR-mediated Cl− ion passage (due to increased F508del-CFTR protein) was characterized via measurement of changes in equivalent current (ΔIeq). Since CFTR-mediated Cl− ion passage and therefore ΔIeq is slightly variable between cell cultures, a 3 μM dose of VX-809 was used as a positive control in all experiments. Data are presented as normalized area under the curve values following stimulation with the cAMP agonist forskolin (10 μM) and VX-770 (1 μM), followed by inhibition with the CFTR inhibitor CFTRInh-172 (20 μM).

As shown in Table 1 and Figure 5, several trends were observed regarding the importance of the 2,2-difluorobenzo[d][1,3]dioxole moiety for corrector efficacy, the impact of substituting the central pyridyl ring with the phenyl ring, and the suitability of the 1,2,3-triazole as an amide bioisostere in the VX-809 chemical series. First, the 4-methoxyphenyl moiety in amide 33 displayed greatly reduced corrector efficacy, highlighting the importance of the 2,2-difluorobenzo[d][1,3]dioxole functionality for F508del-CFTR correction. Secondly, substitution of the pyridyl ring in VX-809 with the phenyl ring in corrector 23 resulted in minimal loss of potency and efficacy, as 23 displayed similar dose response activity to VX-809. The minimal impact of the phenyl substitution on corrector efficacy is also seen in comparison of the 4-methoxyphenyl amide-containing analogs (pyridyl-containing 33 and phenyl-containing 26).

Table 1.

In Vitro Potency and Efficacy Data of Amide and Triazole-Containing Correctors in the VX-809 Chemical Series in F508del CFBE41o-Cells.

| compd | EC50 (μM)[a] | Maximal Response[b] |

|---|---|---|

| 11 | 0.660 ± 0.287 | 48.1% |

| 20 | inactive | -- |

| 23 | 1.960 ± 0.754 | 120.1% |

| 26 | 2.971 ± 0.900 | 54.1% |

| 33 | 0.427 ± 0.514 | 49.9% |

Mean and standard deviation values from at least three determinations are reported.

Maximal response is reported as % activity of the 3 μM VX-809 response.

Figure 5.

Dose response effects of triazole and amide-containing correctors on Cl− conductance in F508del CFBE41o− monolayers using the TECC assay. Current was measured by calculating area under the curve (AUC) after stimulation with forskolin (10 μM) + VX-770 (1 μM), followed by inhibition with CFTRInh-172 (20 μM). A 3 μM dose of VX-809 was used as a positive control in all experiments. Relative corrector efficacy was determined by calculating the percentage of the analog’s response against the 3 μM VX-809 response. Asterisks indicate significant (p<0.05, Two-way ANOVA, Tukey’s post-hoc test) increases in AUC against the vehicle (DMSO) response, n = 3 – 5.

Importantly, as shown in Table 1 and Figure 5, triazole-containing corrector 11 displayed statistically significant correction of F508del-CFTR above the DMSO response, with an EC50 = 0.660 ± 0.287 μM and a maximal efficacy of 48% compared to the 3 μM VX-809 response. This demonstrates that the 2,2-difluorobenzo[d][1,3]dioxole cyclopropane 1,2,3-triazole can serve as a pharmacophore for F508del-CFTR correction, albeit with significantly reduced efficacy in comparison to the analogous amide 23. However, it is possible that optimization of the triazole N1 substituent via the CuAAC reaction of alkyne 9 with structurally diverse azides could result in correctors with improved efficacy.

In contrast, corrector 20 containing the 4-methoxyphenyl cyclopropane 1,2,3-triazole pharmacophore was inactive. As the directly analogous 4-methoxyphenyl amide-containing corrector 26 was significantly less efficacious than 23, the inactivity of triazole 20 is consistent with the loss in efficacy observed upon substitution of the amide with the triazole in this chemical series. In total, these findings demonstrate that while the triazole can be used to replace the amide in the VX-809 structural class when the 2,2-difluorobenzo[d][1,3]dioxole moiety is retained, use of the triazole results in lowered efficacy and is not a suitable replacement for less efficacious amide-containing correctors.

Design of 1,2,3-Triazole Analogs in the VX-770 Structural Class

We next investigated use of the 1,2,3-triazole as an amide bioisostere in the VX-770 potentiator series. As shown in Figure 6, tautomer 34 of VX-770, in which the amide carbonyl oxygen forms an intramolecular H-bond with the quinolinol hydroxyl group, has been proposed to be the bioactive structural isomer.[39] Supporting this hypothesis, attempts to substitute the amide in the VX-770 series with ester, sulfonamide, or reverse amide linkers essentially abolished potentiator efficacy.[39] We hypothesized that triazole containing tautomer 35 could form a similar intramolecular H-bonding interaction to stabilize the bioactive tautomer and would be a suitable linker replacement. Additionally, on the basis of the considerable structure activity relationship (SAR) data published for the amide nitrogen substituent in the VX-770 series, we also targeted triazole analogs of potentiators 36 and 37 reported by Hadida and coworkers during the discovery of VX-770.[39] Amide 36 was selected as it was reported to be the most potent analog characterized in F508del-CFTR HBE cells, and 37 was chosen to explore the indole moiety that was also determined to be highly effective for F508del-CFTR potentiation.[39]

Figure 6.

A) Proposed bioactive tautomer of VX-770[39] and triazole containing analog. B) Structures of highly potent compounds within the VX-770 structural class.[39]

Synthesis of 1,2,3-Triazole Analogs in the VX-770 Structural Class

In contrast to the straightforward synthesis of 1,2,3-triazole analogs within the VX-809 structural class, the synthesis of triazole derivatives in the VX-770 chemical series proved more challenging. We first focused on the synthesis of 3-ethynylquinolin-4(1H)-one 43 that would serve as a key CuAAC precursor as shown in Scheme 5. Iodination of quinolin-4(1H)-one with I2 and Na2CO3 allowed facile synthesis of 3-iodoquinolin-4(1H)-one 39[40] which was subjected to Sonogoshira reaction conditions as reported by Corelli and coworkers.[41] Disappointingly while Corelli and coworkers were able to use microwave irradiation for similar substrates to achieve Sonogoshira coupling without conversion to furo[3,2-c]quinoline derivatives such as 41,[42] reaction of 39 with thermal heating (reflux) under Corelli’s reaction conditions afforded undesired furo[3,2-c]quinoline 41, which was unambiguously identified by conversion to known compound 42.[43] The cyclization likely proceeds through the mechanism shown in Scheme 5 involving coordination of the acetylene by copper and deprotonation of the acidic proton on the quinolinone nitrogen atom.[42] This suggests that use of 43 would lead to a similar cyclization reaction under the copper-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition reaction conditions (see Scheme 5), and this was found to be the case (see Supporting Information).

Scheme 5.

Unsuccessful Synthesis of 43 and Incompatiblity of 43 with CuAAC Due to Cyclization of 3-Ethynylquinolin-4(1H)-ones to Furo[3,2-c]quinolines. Reagents and conditions: (a) I2, Na2CO3, THF, rt, 24 h, 82%; (b) trimethylsilylacetylene, Pd(PPh3)2Cl2, CuI, DIPEA, THF, rt, 18 h, 64%; (c) K2CO3, MeOH, rt, 24 h, 67%.

As a methyl substituent on the quinolin-4(1H)-one nitrogen prevents the cyclization reaction during the Sonogoshira coupling,[42] we began to investigate suitable nitrogen protecting groups. As shown in Supplementary Schemes 1 and 2, use of the methyl and tert-butyl carbamate protecting groups proved ineffective (see Supporting Information). In contrast, use of the benzyl protecting group, which has been successfully used in the synthesis of VX-770,[44] was effective. Benzyl protection of 39 via deprotonation with NaH and reaction with benzyl bromide produced 44.[45] Sonogoshira coupling of 44 with trimethylsilyl acetylene, and TMS deprotection using K2CO3 in MeOH produced terminal alkyne 45 in 57% total yield over the three step sequence as shown in Scheme 6. Pleasingly, use of 45 in the CuAAC reaction with test substrate 4-tert-butylphenyl azide produced the desired click product 46 in moderate yield (66%), and the benzyl group could be removed by refluxing 46 with ammonium formate and Pearlman’s catalyst in DMF. Following these test reactions, the synthesis of 45 was readily scaled up to produce gram quantities of 45.

Scheme 6.

Synthesis of Benzyl Protected 3-ethynylquinolin-4(1H)-one 45 and Compatibility with CuAAC. Reagents and conditions: (a) (i) NaH, THF, 0 °C, 30 min; (ii) benzyl bromide, 0 °C to rt, 19 h, 77%; (b) trimethylsilylacetylene, Pd(PPh3)2Cl2, CuI, DIPEA, THF, rt, 18 h, 86%; (c) K2CO3, MeOH, rt, 24 h, 86%. (d) 4-tert-butylphenyl azide, CuSO4•5H2O, sodium ascorbate, CH2Cl2/tBuOH/H2O (1:2:2), rt, 24 h, 66%.

In parallel with the synthesis of alkyne 45, we also pursued the synthesis of azides 48, 50, and 53 as shown in Scheme 7. Precursor amines 47, 49, and 51 were prepared according to the synthetic procedures reported by Hadida and coworkers (see Supporting Information, Supplementary Scheme 3).[39] The synthesis of azides 48 and 50 was readily accomplished in good yield by treatment of the precursor amine with NaNO2 followed by NaN3. Surprisingly, use of these reaction conditions with aniline 51 could not produce the desired azide, as vigorous gas evolution was observed after the addition of NaNO2 to 51. Fortunately, use of Zhang and Moses’ method for azide formation using tBuONO and TMSN3 in MeCN[46] proved effective, although significant formation of trimethylsilyl protected phenol 52 was produced (73%) in addition to isolation of the desired azide 53 (20%). This did not prove to be problematic as the TMS group could be readily removed by treatment with TBAF to produce 53 in quantitative yield. Notably aniline 51 is not a bench stable solid, and must be transformed to the azide immediately after preparation to prevent decomposition to quinone 54.[47]

Scheme 7.

Synthesis of Azides 48, 50, and 53. Reagents and conditions: (a) (i) EtOAc, HCl, 0 °C, 5 min; (ii) NaNO2, H2O, 0 °C, 30 min; (iii) NaN3, H2O, 0 °C to rt, 2 h, 48: 81%; 50: 75%; 53: 0%; (b) TMSN3, tBuONO, MeCN, rt, 18 h, 52: 73%, 53: 20%; (c) TBAF, THF, 0 °C to rt, 2 h, 100%.

With azides 48, 50, and 53 and alkyne 45 in hand we completed the synthesis of the 1,2,3-triazole containing potentiators as shown in Scheme 8. While CuAAC could be achieved with azides 48 and 50 at rt, no product formation was observed for reaction of alkyne 45 with sterically hindered azide 53 at rt. Fortunately, heating to 60 °C for 24 h produced the desired product 60 in modest yield (45%), but attempts to improve yield by extending the reaction time (up to 3 days) were unsuccessful. Finally, removal of the benzyl protection group using ammonium formate and Pearlman’s catalyst in refluxing DMF afforded the desired 1,2,3-triazole analogs in good yield. Additionally, in order to directly compare the potentiator ability of the triazole derivatives to their parent amides 36 and 37, these compounds were also prepared. As shown in Scheme 9, HATU-mediated amide bond formation afforded the desired compounds in improved yields over the published reaction procedures.[39]

Scheme 8.

Synthesis of 1,2,3-Triazole Containing Potentatiors 56, 58, and 60. Reagents and conditions: (a) CuSO4•5H2O, sodium ascorbate, CH2Cl2/tBuOH/H2O (1:2:2), rt, 24 h, 55: 69%, 57: 71%, 59: 0% (b) Pd(OH)2, ammonium formate, DMF, 80 °C, 56: 10 h, 74%, 58: 8 h, 88%, 60: 8.5 h, 87%; (c) CuSO4•5H2O, sodium ascorbate, CH2Cl2/tBuOH/H2O (1:2:2), 60 °C, 24 h, 45%.

Scheme 9.

Synthesis of Amide Containing Potentiators 36 and 37. Reagents and conditions: (a) 47 or 49, HATU, Et3N, CH2Cl2, 70 °C, 16 h, 36: 87%; 37: 64%.

In vitro Evaluation of 1,2,3-Triazole Analogs in the VX-770 Structural Class

1,2,3-triazole containing potentiators 56, 58, and 60 were evaluated for potentiator activity and compared to amide potentiators 36, 37, and VX-770 in Ussing Chamber experiments. VX-770 is known to potentiate WT-CFTR (that does not exhibit a gating defect) and F508del-CFTR and G551D-CFTR (that do display the gating defect) with varying levels of potency and efficacy.[27,48] Accordingly, we evaluated our amide and triazole-containing potentiators in CFBE41o− monolayers with complementary WT CFTR expression (WT CFBE41o−), F508del CFBE41o− monolayers after 24 h treatment with VX-809 (3 μM) to rescue mutant F508del-CFTR to the cell surface, and CFBE41o− monolayers with complementary G551D-CFTR expression (G551D CFBE41o−).[49] In addition, we also utilized Fischer Rat Thyroid (FRT) cells expressing G551D as this cell line is commonly used to characterize potentiator compounds and exhibits elevated Cl− ion conductance compared to CFBE cells.[50] We reasoned the higher Cl− ion conductance might allow the detection of weak potentiators and differentiate the response between potentiators to a greater extent than the CFBE41o− cell line.

The effect of the potentiator compounds was quantified via measurement of changes in short circuit current (∆Isc) due to increased CFTR-mediated Cl− ion secretion. The response was measured as the cumulative ΔIsc observed with serial addition of each test agent after stimulation with forskolin, either 100 nM (the EC50) in WT monolayers or 10 μM in mutant (F508del, G551D) monolayers. As Cl− ion transport and increases in ∆Isc can be variable between cell cultures, VX-770 was used as a positive control in all experiments and relative potentiator efficacy was determined by calculating the percentage of each analog’s response against the VX-770 response as shown in Table 2 and Figure 7. Potency was quantified by determining EC50 values and is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

In Vitro Potency and Efficacy Data of Amide and Triazole-Containing Potentiators in the VX-770 Chemical Series in CFBE41o− and FRT Cells.[a]

| EC50 (nM)[b] | Maximal Response[c] | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compd | WT CFBE | F508del CFBE | G551D CFBE | G551D FRT | WT CFBE | F508del CFBE | G551D CFBE | G551D FRT |

| VX-770 | 36.5 ± 21.3 | 1889 ± 1388 | 77.7 ± 27.2 | 428.5 ± 167.3 | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% |

| 36 | -- | -- | 26.7± 79.4 | -- | Inactived | Inactived | 63.5% | Inactived |

| 37 | 21.8 ± 41.2 | 37.1 ± 48.2 | 18.5 ± 23.4 | 81.45 ± 102.8 | 47.5% | 36.3% | 72.0% | 36.7% |

| 56 | Inactive across all cell and CFTR typesd | |||||||

| 58 | Inactive across all cell and CFTR typesd | |||||||

| 60 | Inactive across all cell and CFTR typesd | |||||||

CFBE41o− abbreviated as CFBE.

Mean and standard deviation values from at least three determinations are reported.

Maximal response is reported as % activity of the VX-770 response.

No statistically significant response above DMSO vehicle.

Figure 7.

Dose response effects of triazole and amide-containing potentiators on Cl− conductance in WT CFBE41o−, F508del CFBE41o− following 24 h exposure to VX-809 (3 μM), G551D CFBE41o−, and G551D FRT cell lines. Current was measured after stimulation with forskolin (100 nM in WT and 10 μM in mutants F508del and G551D). Inhibition with CFTRInh-172 (10 μM) demonstrated that increased current was due to a CFTR-mediated mechanism. Relative potentiator efficacy was determined by calculating the percentage of the analog’s response against the VX-770 response. Data are normalized according to vehicle (DMSO) response. Asterisks indicate significant (p<0.05, Two-way ANOVA, Tukey’s post-hoc test) increases in Isc against the vehicle (DMSO) response, n = 3 – 5.

Disappointingly, as shown in Table 2 and Figure 7, none of the 1,2,3-triazoles (56, 58, 60) achieved statistically significant increases in ∆Isc above the DMSO response in any of the CFTR variants or cell types tested. These findings demonstrate that use of the 1,2,3-triazole moiety significantly alters the VX-770 chemical scaffold such that potentiation is abolished in the in vitro cellular assay. Among the active amide-containing potentiators, VX-770 consistently displayed the highest efficacy by 1.5 to 3-fold (Table 2), a finding that to our knowledge has not previously been reported in the primary literature as Hadida and coworkers did not report a measurement of efficacy for 36 and 37.[39] Interestingly, 36 (which varies structurally from VX-770 only in the deletion of one tert-butyl group) did not produce statistically significant potentiation above the DMSO response except in the G551D CFBE41o− cell line. In contrast, indole 37 displayed more robust efficacy across all cell lines, although it was less efficacious than VX-770. However, 37 did display improved potency over VX-770 in our experiments. In total, these results demonstrate the essential nature of the amide linker in the VX-770 series as substitution with the triazole resulted in inactivity in the cellular assay. These studies also highlight the important impact of the amide substituent on in vitro efficacy.

X-Ray Crystal Structures and Natural Bond Orbital Calculations for VX-770 and 1,2,3-Triazole Analog 60

Following our disappointing findings that 1,2,3-triazole containing potentiators in the VX-770 structural class were inactive in the cellular Ussing Chamber assays, we verified that we correctly synthesized the targeted 1,4-substituted 1,2,3-triazoles by obtaining the crystal structure of triazole 60 as shown in Figure 8A. With the X-ray structure providing conclusive proof that we synthesized the targeted triazole analog, we also obtained the crystal structure of VX-770 as shown in Figure 8B. We then compared the two structures in order to gain insight into the structural differences in the solid-state (an overlay of the structures is shown in Figure 8C). In line with previous studies comparing the R1-R2 distance in amide and 1,2,3-triazole analogs,[3] the C8-C12 distance across the triazole in 60 was determined to be 4.99 Å. In comparison the C7-C11 distance (i.e. the analogous R1-R2 distance) across the amide in VX-770 was 3.76 Å, representing a 1.23 Å lengthening of the linker between the quinolin-4(1H)-one core and the phenol substituent upon replacement of the amide with the triazole. Additionally, the orientation angle between the quinolin-4(1H)-one and phenol substituents as defined in Figure 8D was increased upon substitution of the amide (143.4°) with the triazole (161.5°). We wondered if the increased linker length and/or the slight change in orientation angle could be responsible for an unfavorable steric interaction between potentiator 60 and the binding pocket.

Figure 8.

A) Crystal structure of 60 showing representation of the thermal ellipsoids. B) Crystal structure of VX-770 showing representation of the thermal ellipsoids. H-bonding interaction is shown in red. C) Overlay of crystal structures of 60 and VX-770. D) Calculation of orientation angle between quinolin-4(1H)-one and phenol substituents using Olex2.[51] For VX-770 lines were generated from C7-C10, C10-C11, and C7-C11 to define a triangle. The C7-C10-C11 angle was measured to be 143.4°. For 60 lines were generated from C8-C10, C10-C12, and C8-C12 and the C8-C10-C12 angle was measured to be 161.5°.

More relevant than comparison of the solid-state structures was a structural comparison of the proposed bioactive tautomeric isomer and quantification of whether the triazole nitrogen atom could participate in H-bonding with the quinolinol hydroxyl to stabilize the tautomer as we had hypothesized (see Figure 6). To this end, we first performed a computational geometry optimization on the solid-state crystal structures of VX-770 and 60 at the M06–2X/6–31 + G(d) level of theory using the experimentally-derived X-ray structures as the input geometries. We then modeled the quinolinol tautomer for both molecules by tautomerizing the CO bond and rotating the amide or triazole moiety so that it could participate in an intramolecular H-bonding interaction (as shown in Figure 9). These geometries were then optimized computationally. Additionally, Natural Bond Orbital (NBO) analysis was performed on both of the resulting optimized geometries to quantify the degree of intramolecular H-bonding that stabilizes the tautomeric form. Stabilization afforded to the molecule by hydrogen bonding of the quinolinol O-H bond with the triazole nitrogen atom’s lone pair was estimated to be 27.02 kcal/mol (as determined from 2nd order perturbation theory within the NBO analysis). This confirmed that a substantial intramolecular H-bonding interaction can exist with the triazole ring as a donor as shown in Figure 9B which displays the relevant orbital interactions of the H-bond as provided by NBO analysis. In comparison, stabilization afforded by hydrogen bonding of the quinolinol O-H bond with the amide group’s carbonyl oxygen lone pairs was estimated to be 38.30 kcal/mol (see Figure 9A and Supporting Information). This analysis confirmed that the 1,2,3-triazole ring in 60 can participate in a H-bonding interaction with the quinolinol hydroxyl group to stabilize the bioactive tautomer similarly to the amide carbonyl within VX-770.

Figure 9.

Optimized geometries for tautomeric isomers 34 and 35 at the M06-2X/6-31 + G(d) level of theory. The resulting hydrogen bonds between the tautomeric OH bond and the lone-pair donor atom in each molecule are illustrated by the relevant orbital interactions as provided by NBO analysis. A second, weaker, lone pair donation from the CO bond of 34 to the OH bond (see Supporting Information) is not shown for the sake of clarity.

We also quantified the difference in energies (including zero-point energy corrections) between the optimized non-tautomeric and tautomeric conformations. This calculation allows comparison of the energetic cost of assuming the bioactive conformation. Interestingly, assuming bioactive conformation 34 from the optimized geometry of VX-770 requires 8.4 kcal/mol in energy, while the energetic cost to access 35 from 60 was significantly less at 3.8 kcal/mol. This analysis suggests that 60 is not energetically hindered from achieving the bioactive tautomeric form, as evidenced by the lower energetic cost required to assume the quinolinol tautomeric form in comparison to VX-770.

The lower energetic barrier in the conversion of 60 to 35 is likely due to the fact that an intramolecular H-bond already exists between the amide and quinolinone carbonyl in VX-770 (red dotted line in Figure 8B). Converting to tautomeric conformation 34, therefore, involves trading one hydrogen bond in VX-770 (20.46 kcal/mol) for another, stronger hydrogen bond in the tautomeric form (38.30 kcal/mol). The net stabilization of 17.84 kcal/mol from the new hydrogen bonding interaction partially offsets the energetic cost of assuming the tautomeric form. In contrast, no H-bonding interaction is present in the non-tautomeric form of triazole analog 60 (Figure 8A) and so the energy required to populate tautomeric form 35 from 60 is offset to a greater degree by the formation of the new H-bond interaction in 35 for a net stabilization of 27.02 kcal/mol.

Finally, we quantified the R1-R2 distance between the amide and triazole substituents and angle of orientation between the R1 and R2 substituents in the energy optimized tautomeric forms as we did for the solid state crystal structures. Interestingly, the C8-C12 distance across the triazole in 35 was determined to be 4.99 Å and the C7-C11 distance across the amide in 34 was 3.78 Å, both of which were very similar to the solid state measurements. The orientation angles were also comparable between the tautomeric forms and the solid state as the orientation angle (as defined in Figure 8D) of the amide was found to be 145.6° and the orientation angle of the triazole was determined to be 163.7°.

In summary, the NBO calculations suggest that triazole 60 should be able to assume the bioactive conformation 35. Comparison of the energy optimized structures and X-ray crystal structures highlight the lengthened R1-R2 distance and increased angle of orientation that would position the triazole substituents in a slightly different position in the CFTR binding pocket relative to the amide substituents.

Patch Clamp Analysis of VX-770 and 1,2,3-Triazole Analog 60

Given the computational evidence that the 1,2,3-triazole isomers should be able to assume the bioactive tautomeric conformation, we investigated the potentiator ability of 60 using patch clamp analysis in order to study the interaction of our triazole potentiators directly with the CFTR protein. We hypothesized that this experiment would eliminate potential cellular factors that may be responsible for the inactivity of 60 in vitro and provide insight into whether structural changes arising from incorporation of the 1,2,3-triazole prevent interaction of the potentiator with the binding site of CFTR. Macroscopic currents for WT-CFTR were recorded in the excised inside-out patch as shown in Figure 10. Interestingly, we observed that triazole-containing potentiator 60 robustly stimulated WT-CFTR currents in a dose dependent manner. The potency and efficacy of triazole 60 was similar to VX-770, as 60 exhibited an EC50 of 5.5 ±0.9 nM in comparison to an EC50 of 1.3 ±0.3 nM for VX-770, and 60 increased the percent of the PKI control to a slightly greater extent than VX-770. These findings demonstrate that under the cell-free condition, the 1,2,3-triazole substitution within the VX-770 chemical series is tolerated and that triazole-containing analogs can directly interact with CFTR and potentiate the channel activity. Moreover, they raise the question as to the cause of inactivity in the cellular assay.

Figure 10.

Dose response analysis for VX-770 and 60 by patch clamp analysis. A/B) VX-770 and 60 titrations for representative patches. Protein kinase A inhibitor (PKI) was applied to prevent further phosphorylation. C) Mean titration data fit to Y = Bmax*X/(K1 + X), EC50 =1.3 ±0.3 (n=5) for VX-770 and 5.5 ±0.9 (n=6) for 60. Data were normalized to the peak current at 100–200 nM. The results are reported as means ±S.E. The lowest dose tested was 0.2 nM, which increased the current by ~12% for VX-770 and ~7% for 60. D) Mean data % of maximal stimulation (efficacy) by VX-770 and 60.

Comparison of the Metabolic Stability of 1,2,3-Triazole and Amide-Containing CFTR Modulators

Having uncovered some drawbacks in the use of the 1,2,3-triazole as an amide bioisostere in the VX-809 and VX-770 structural classes, we investigated whether the incorporation of the triazole would afford beneficial pharmacokinetic properties as has been demonstrated in some instances[14] and is widely perceived to be the case.[2–5] To this end, the metabolic stability of five triazoles and the analogous amides was evaluated in human hepatic microsomes.

Intrinsic clearance (CLINT) and calculated human hepatic clearance (CLHEP) are shown in Table 3 (triazole and amide pairs are listed side-by-side). Surprisingly, in all but one instance (20 vs. 26) the triazole derivatives showed reduced microsomal stability (i.e., increased CLINT) in comparison to the analogous amide. In particular, triazole corrector 11 displayed substantially increased CLINT in comparison to amide 23, and all triazole potentiators (56, 58, 60) showed a modest increase in microsomal clearance. In contrast to the common perception that the triazole affords increased metabolic stability (due to elimination of amide hydrolysis), the decreased stability of the triazole analogs studied here demonstrates that the triazole may also have a negative effect on hepatic clearance in certain applications. This impact on hepatic clearance must also be taken into account when considering the overall impact of the triazole substitution on metabolic stability.

Table 3.

Intrinsic Clearance (CLINT) in Human Microsomes and Predicted Hepatic Clearance (CLHEP) of Analogous Triazole and Amide-Containing CFTR Modulators.

| 1,2,3-triazole | amide | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cmpd | CLINT[a] (mL min−1 kg −1) | CLHEP[b] (mL min−1 kg −1) | cmpd | CLINT[a] (mL min−1 kg −1) | CLHEP[b] (mL min−1 kg −1) |

| 11 | 11.8 | 7.55 | 23 | 2.49 | 2.23 |

| 20 | 23.2 | 11.0 | 26 | 36.1 | 13.3 |

| 56 | 16.3 | 9.19 | 36 | 12.5 | 7.84 |

| 58 | 19.3 | 10.1 | 37 | 9.35 | 6.47 |

| 60 | 56.2 | 15.3 | VX-770 | 45.6 | 14.4 |

Intrinsic clearance in human hepatic microsomes.

Predicted hepatic clearance, human.

Conclusions

In conclusion, despite the widespread success of the 1,2,3-triazole as an amide bioisostere, our results demonstrate that use of the triazole is not effective in all medicinal chemistry contexts and highlight several negative impacts that can arise from this substitution. First, in the context of the VX-809 chemical series, while the 2,2-difluorobenzo[d][1,3]-dioxole cyclopropane 1,2,3-triazole was found to be a suitable pharmacophore for F508del-CFTR correction, the triazole derivative displayed significantly reduced corrector efficacy as 11 increased Cl− ion transport in F508del CFBE41o− cells to only 48% of the 3 μM VX-809 response. Additionally, triazole corrector 20, containing the 4-methoxyphenyl group, was inactive in contrast to the analogous amide 26 which displayed modest F508del-CFTR correction (54% of the 3 μM VX-809 response). These findings highlight that the triazole, while tolerated in the VX-809 chemical series when the 2,2-difluorobenzo[d][1,3]-dioxole cyclopropane moiety is maintained, is not widely applicable across less efficacious correctors in this series.

Secondly, in the VX-770 chemical series, the use of the triazole substitution completely abolished potentiator activity in the cellular assays. These findings point to a significant structural change to the VX-770 scaffold resulting from the triazole substitution. On the basis of Natural Bond Orbital calculations performed on triazole 60, this structural change is not likely to be disruption of the proposed bioactive tautomeric form as the triazole was found to be able to participate in the necessary intramolecular H-bonding interaction that stabilizes the tautomer. Furthermore, quantification of the difference in energy between the optimized non-tautomeric and tautomeric conformations provided evidence that 60 is not energetically hindered from achieving the bioactive conformation. The conclusions drawn from these calculations were supported by the similar potency and efficacy of 60 in comparison to VX-770 in the cell-free patch clamp experiment. The patch clamp results suggest that the inactivity of triazole potentiators 56, 58, and 60 in the cellular assay could be due to the inability of these compounds to access the CFTR binding site under cellular conditions, either due to poor membrane permeability or active transport out of the cell. These findings highlight the considerable impact the triazole substitution can have on crucial physiochemical properties that impact target engagement.

Thirdly, comparison of the solid-state structures of 60 and VX-770 and comparison of the energy optimized tautomeric forms 34 and 35 highlight the structural differences resulting from the triazole substitution. The distance across the amide substituents increases by ~1.2 Å in the triazole derivative, and the angle of orientation between the amide substituents is increased by ~18.1° in the triazole. While these structural changes can be tolerated in many instances without negative consequences on biological activity and/or physiochemical properties,2−5 this did not prove to be the case in the VX-809 and VX-770 chemical series.

Finally, despite the widespread perception that use of the 1,2,3-triazole can provide increased metabolic stability, in two distinct chemical series 1,2,3-triazole derivatives largely displayed similar or increased metabolic clearance in human hepatic microsomal assays. In the case of triazole 11 (CLINT = 11.8) the increase in intrinsic clearance was substantial (~5x) in comparison to the analogous amide 23 (CLINT = 2.49). In total, these findings represent an important contrast to the many successful uses of the 1,2,3-triazole as an amide bioisostere in medicinal chemistry.

Experimental Section

Complete experimental procedures and Supplementary Schemes and Figures are provided in the Supporting Information. Chemistry: Supplementary Schemes and Figures, synthetic experimental procedures, compound characterization data, copies of 1H and 13C NMR spectra, X-ray crystallography data, and details on computational studies are provided. Biology: Experimental procedures for cell culture, TECC assay, Ussing Chamber recordings, patch clamp analysis, and intrinsic clearance assays are provided.

CCDC data 1879006 (VX-770) and 1879007 (60) contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data are provided free of charge by The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the following sources of funding: J.E.D. thanks the Richards Scholar Program for financial support. S.G.A. acknowledges funding by the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (ALLER16P0 and ALLER16G0). S.M.R. acknowledges funding from the NIH (P30 DK072482 and R35 HL135816) and the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (R464-CR11). The authors gratefully thank Prof. Craig Lindsley of Vanderbilt University for access to microsomal stability analysis, compound purity analysis, and HRMS analysis. The authors thank Dr. John Bacsa at the X-ray Crystallography Center at Emory University for X-ray data collection.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is given via a link at the end of the document.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- [1].Hein JE, Fokin VV, Chem. Soc. Rev 2010, 39, 1302–1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Bonandi E, Christodoulou MS, Fumagalli G, Perdicchia D, Rastelli G, Passarella D, Drug Discov. Today 2017, 22, 1572–1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Hou J, Liu X, Shen J, Zhao G, Wang PG, Expert Opin. Drug Discov 2012, 7, 489–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Tron GC, Pirali T, Billington RA, Canonico PL, Sorba G, Genazzani AA, Med. Res. Rev 2008, 28, 278–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Kolb HC, Sharpless KB, Drug Discov. Today 2003, 8, 1128–1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Chrysina ED, Bokor É, Alexacou K-M, Charavgi M-D, Oikonomakos GN, Zographos SE, Leonidas DD, Oikonomakos NG, Somsák L, Tetrahedron Asymmetry 2009, 20, 733–740. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Horne WS, Yadav MK, Stout CD, Ghadiri MR, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2004, 126, 15366–15367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Mohammed I, Kummetha IR, Singh G, Sharova N, Lichinchi G, Dang J, Stevenson M, Rana TM, J. Med. Chem 2016, 59, 7677–7682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Arioli F, Borrelli S, Colombo F, Falchi F, Filippi I, Crespan E, Naldini A, Scalia G, Silvani A, Maga G, Carraro F, Botta M, Passarella D, ChemMedChem 2011, 6, 2009–2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Peruzzotti C, Borrelli S, Ventura M, Pantano R, Fumagalli G, Christodoulou MS, Monticelli D, Luzzani M, Fallacara AL, Tintori C, Botta M, Passarella D, ACS Med. Chem. Lett 2013, 4, 274–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Christodoulou MS, Mori M, Pantano R, Alfonsi R, Infante P, Botta M, Damia G, Ricci F, Sotiropoulou PA, Liekens S, Botta B, Passarella D, ChemPlusChem 2015, 80, 938–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ballard TE, Richards JJ, Wolfe AL, Melander C, Chem. – Eur. J 2008, 14, 10745–10761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Mugnaini C, Nocerino S, Pedani V, Pasquini S, Tafi A, De Chiaro M, Bellucci L, Valoti M, Guida F, Luongo L, Dragoni S, Ligresti A, Rosenberg A, Bolognini D, Cascio MG, Pertwee RG, Moaddel R, Maione S, Di Marzo V, Corelli F, ChemMedChem 2012, 7, 920–934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Keck TM, Banala AK, Slack RD, Burzynski C, Bonifazi A, Okunola-Bakare OM, Moore M, Deschamps JR, Rais R, Slusher BS, Newman AH, Bioorg. Med. Chem 2015, 23, 4000–4012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Mamidyala SK, Finn MG, Chem. Soc. Rev 2010, 39, 1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Hwang T-C, Yeh J-T, Zhang J, Yu Y-C, Yeh H-I, Destefano S, J. Gen. Physiol 2018, jgp.201711946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [17].Sheppard DN, Welsh MJ, Physiol. Rev 1999, 79, S23–S45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Sloane PA, Rowe SM, Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med 2010, 16, 591–597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Jennings MT, Flume PA, Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc 2018, 15, 897–902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Sosnay PR, Raraigh KS, Gibson RL, Pediatr. Clin. North Am 2016, 63, 585–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Bobadilla JL, Macek M Jr., Fine JP, Farrell PM, Hum. Mutat 2002, 19, 575–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Serohijos AWR, Hegedus T, Aleksandrov AA, He L, Cui L, Dokholyan NV, Riordan JR, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2008, 105, 3256–3261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Penque D, Mendes F, Beck S, Farinha C, Pacheco P, Nogueira P, Lavinha J, Malhó R, Amaral MD, Lab. Invest 2000, 80, 857–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Van Goor F, Hadida S, Grootenhuis PDJ, Burton B, Stack JH, Straley KS, Decker CJ, Miller M, McCartney J, Olson ER, Wine JJ, Frizzell RA, Ashlock M, Negulescu PA, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2011, 108, 18843–18848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Wang W, Li G, Clancy JP, Kirk KL, J. Biol. Chem 2005, 280, 23622–23630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Miki H, Zhou Z, Li M, Hwang T-C, Bompadre SG, J. Biol. Chem 2010, 285, 19967–19975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Goor FV, Hadida S, Grootenhuis PDJ, Burton B, Cao D, Neuberger T, Turnbull A, Singh A, Joubran J, Hazlewood A, Zhou J, McCartney J, Arumugam V, Decker C, Yang J, Young C, Olson ER, Wine JJ, Frizzell RA, Ashlock M, Negulescu P, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2009, 106, 18825–18830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Matsui H, Grubb BR, Tarran R, Randell SH, Gatzy JT, Davis CW, Boucher RC, Cell 1998, 95, 1005–1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Kym PR, Wang X, Pizzonero M, Van der Plas SE, in Prog. Med. Chem (Eds.: Witty DR, Cox B), Elsevier, 2018, pp. 235–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Wang X, Liu B, Searle X, Yeung C, Bogdan A, Greszler S, Singh A, Fan Y, Swensen AM, Vortherms T, Balut C, Jia Y, Desino K, Gao W, Yong H, Tse C, Kym P, J. Med. Chem 2018, 61, 1436–1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Okiyoneda T, Veit G, Dekkers JF, Bagdany M, Soya N, Xu H, Roldan A, Verkman AS, Kurth M, Simon A, Hegedus T, Beekman JM, Lukacs GL, Nat. Chem. Biol 2013, 9, 444–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Eckford PD, Ramjeesingh M, Molinski S, Pasyk S, Dekkers JF, Li C, Ahmadi S, Ip W, Chung TE, Du K, Yeger H, Beekman J, Gonska T, Bear CE, Chem. Biol 2014, 21, 666–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Bolje A, Urankar D, Košmrlj J, Eur. J. Org. Chem 2014, 8167–8181.

- [34].Hadida R, Grootenhuis PDJ, Zhou J, Bear B, Miller M, McCartney J, Pyridine Compounds as Modulators of CFTR and Their Preparation and Use in the Treatment of Diseases WO 2008/141119, November 20, 2008.

- [35].Siesel D, Processes for Producing Cycloalkylcarboxamido-Pyridine Benzoic Acids US 8,124,781 B2, February 28, 2012.

- [36].Goncz KK, Kunzelmann K, Xu Z, Gruenert DC, Hum. Mol. Genet 1998, 7, 1913–1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Ehrhardt C, Collnot E-M, Baldes C, Becker U, Laue M, Kim K-J, Lehr C-M, Cell Tissue Res 2006, 323, 405–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Phuan P-W, Veit G, Tan J, Roldan A, Finkbeiner WE, Lukacs GL, Verkman AS, Mol. Pharmacol 2014, 86, 42–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Hadida S, Van Goor F, Zhou J, Arumugam V, McCartney J, Hazlewood A, Decker C, Negulescu P, Grootenhuis PDJ, J. Med. Chem 2014, 57, 9776–9795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Almeida A, Silva A, Cavaleiro J, Synlett 2010, 2010, 462–466. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Mugnaini C, Falciani C, De Rosa M, Brizzi A, Pasquini S, Corelli F, Tetrahedron 2011, 67, 5776–5783. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Venkataraman S, Barange DK, Pal M, Tetrahedron Lett 2006, 47, 7317–7322. [Google Scholar]

- [43].Beydoun K, Doucet H, Eur. J. Org. Chem 2012, 2012, 6745–6751. [Google Scholar]

- [44].Thatipally S, Reddy VK, Dammalapati VLNR, Chava S, Processes for the Preparation of Ivacaftor WO 2017/037672 A1, March 9, 2017.

- [45].Audisio D, Messaoudi S, Peyrat J-F, Brion J-D, Alami M, J. Org. Chem 2011, 76, 4995–5005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Zhang F, Moses JE, Org. Lett 2009, 11, 1587–1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Thatipally S, Reddy VK, Dammalapati VLNR, Gorantla SRA, Chava S, An Improved Process for the Preparation of 5-Amino-2,4,-Di-Tert-Butylphenol or an Acid Additional Salt Thereof WO 2016/075703 A2, May 19, 2016.

- [48].Jih K-Y, Hwang T-C, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2013, 110, 4404–4409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Gottschalk LB, Vecchio-Pagan B, Sharma N, Han ST, Franca A, Wohler ES, Batista DAS, Goff LA, Cutting GR, J. Cyst. Fibros 2016, 15, 285–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Yu H, Burton B, Huang C-J, Worley J, Cao D, Johnson JP, Urrutia A, Joubran J, Seepersaud S, Sussky K, Hoffman BJ, Van Goor F, J. Cyst. Fibros 2012, 11, 237–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Dolomanov OV, Bourhis LJ, Gildea RJ, Howard JAK, Puschmann H, J. Appl. Crystallogr 2009, 42, 339–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.