Abstract

Many approaches to elastography incorporate shear waves; in some systems these are produced by acoustic radiation force push pulses. Understanding the shape and decay of propagating shear waves in lossy tissues is key to obtaining accurate estimates of tissue properties, and so analytical models have been proposed. In this paper, we reconsider a previous analytical model with the goal of obtaining a computationally straightforward and efficient equation for the propagation of shear waves from a focal push pulse. Next, this model is compared with an experimental optical coherence tomography system and with finite element models, in two viscoelastic materials that mimic tissue. We find that the three different cases - analytical model, finite element model, and experimental results - demonstrate reasonable agreement within the subtle differences present in their respective conditions. These results support the use of an efficient form of the Hankel transform for both lossless (elastic) and lossy (viscoelastic) media, and for both short (impulsive) and longer (extended) push pulses that can model a range of experimental conditions.

Keywords: shear wave propagation, axisymmetric Gaussian force, attenuation, dispersion, viscoelastic models, tissues, elastography, OCT, acoustic radiation force

1. Introduction

Within the broad field of elastography (Parker et al. 2011, Ophir et al. 2011), one approach to generating shear waves in tissues utilizes a push pulse of acoustic radiation force (ARF) from a focused ultrasound transducer (Sarvazyan et al. 1998). The resulting disturbance can be tracked using motion detection techniques implemented in different imaging systems, such as ultrasound and optical coherence tomography (OCT), and, from these waveforms, parameters including shear wave speed are extracted. Accurate analytical models can be helpful in understanding the phenomenon of how the shear waves evolve over space and time in tissues. A number of analytical models have been proposed (Bercoff et al. 2004, Fahey et al. 2005, Kazemirad et al. 2016, Leartprapun et al. 2017, Nenadic at al. 2017, Nightingale et al. 1999, Parker and Baddour 2014, Sarvazyan et al. 1998, Schmitt et al. 2010, Vappou et al. 2009, Wijesinghe et al. 2015) to capture the evolution of shear waves from a push pulse, under a range of conditions and assumptions relevant to clinical elastography.

Herein, we focus on the specific case of a rotationally symmetric push pulse that is long in the axial direction, leading to solutions in cylindrical coordinates. A prior set of derivations was proposed by Parker and Baddour (2014) with additional experimental and theoretical developments (Zvietcovich et al 2017a, Baddour 2018, Parker et al. 2018) published more recently. However, a number of issues remain and are the subject of this paper. First, within the possible uses of Baddour’s Integral Theorems (Baddour 2011), we examine which strategy leads to the more straightforward solutions including numerical solutions. In this case, we choose a path that avoids the singularities and other issues associated with the complex Hankel functions in favor of a path leading to a simpler Bessel function integrand, commensurate with Hankel transform interpretation. Second, we apply these techniques to two phantom materials with lower and higher viscoelastic loss parameters to predict the propagating shear wave pulses from an applied push pulse. These predictions are compared with experimental OCT data and with finite element analysis results. The three approaches produce similar results and confirm the utility of our analytical model within reasonable experimental parameters.

The paper is organized as follows: first, in Section 2, we review the theory of axisymmetric propagating shear wave pulses in elastic and then in viscoelastic materials. Subsequently, in Section 3, we describe the methodology for selecting phantom materials mimicking lossless and lossy conditions and the viscoelastic characterization using mechanical testing analysis. This section also includes: the description of wave propagation experiments in those phantoms using an OCT system and an ARF ultrasonic transducer all implemented in an integrated setup; details on the simulation of wave propagation under the same material properties and boundary conditions using finite elements; and the predictions of our proposed model in the same context. In Section 4, results are shown and compared for the following cases: OCT experiments, finite element models, and our model predictions. The utility of our model, its extension under the assumptions made, and limitations are discussed in Section 5. Finally, conclusions of the entire work are summarized in Section 6.

2. Theory

2.1. Cylindrical shear wave equation produced by a body force excitation

The governing equation describing the motion produced by a propagating shear horizontal wave in a homogeneous, isotropic and elastic material, using the notation from Graff (1975) in cylindrical coordinates, is given as

| (1) |

where ∇2 is the Laplacian operator in cylindrical coordinates, uz(r, θ, z; t) is the displacement of the shear wave in the z-direction, c is the velocity of the wave; Fz(r, θ, z) is the distribution of the applied body force in the z-direction, and g(t) is the temporal application of the force. We assume that, given the direction of the applied force, the produced shear wave will propagate cylindrically outwards from the source origin, parallel to the -plane. Therefore, the displacement is polarized in the z-direction, and any derivates of uz with respect to θ or z are zero.

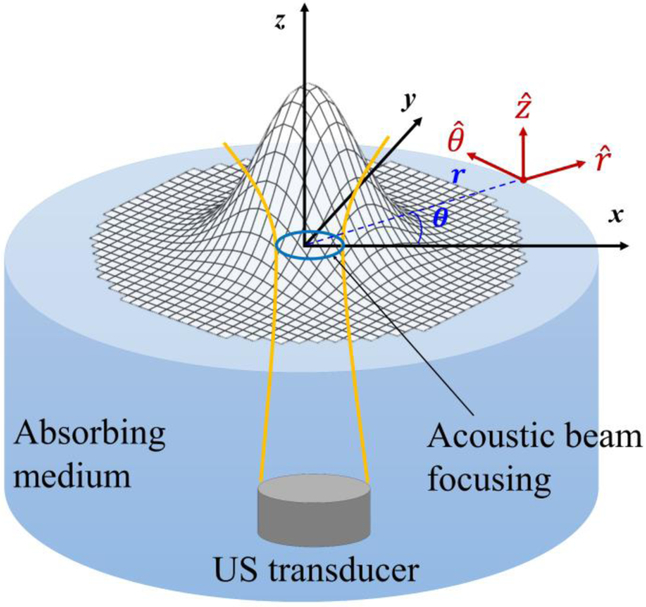

The force source Fz(r, θ, z) is assumed to be axisymmetric and extended uniformly in the z-direction, similar to most of the ultrasound (US)-based ARF excitation beams. Figure 1 shows a Gaussian-shaped force produced by a spherically focused US transducer located at the origin of a polar coordinate system, and described as

| (2) |

where σ2 is the half variance of the pulse shape, and A0 is the force intensity.

Figure 1.

Schematic of a Gaussian-shaped force pulse produced in a viscoelastic medium by an ultrasound ARF transducer. The center of the pulse is the origin of the coordinate systems, with r and θ as the radial and angular components in the cylindrical coordinate system, and x, y, and z as the Cartesian axes.

Introducing the displacement and source constraints, and assuming displacement and particle velocity are set to zero everywhere as initial conditions, Eqn 1 can be rewritten as

| (3) |

The shear speed c in Eqn 3 is related to the shear modulus μ of an elastic, homogenous, and incompressible medium with a density ρ as . However, in a viscoelastic medium, the shear modulus is a complex and frequency-dependent quantity , where μs(ω) and μl(ω) are called the shear storage and loss moduli, respectively (Carstensen et al. 2014). Then, , and the wave equation is better represented in the Fourier domain.

Taking the temporal Fourier transform of Eqn 3, yields

| (4) |

where , is the complex wave number , , and ω is the angular frequency with respect to time.

2.2. Cylindrical coordinate solution: Green’s function in an elastic medium

The Laplacian operator in Eqn 3 for cylindrical coordinates leads naturally to the Hankel transform (Graff, 1975). Thus, applying the zeroth order Hankel transform in space to Eqn 4 in cylindrical coordinates yields:

| (5) |

where , ε is the spatial frequency, , , and where we assume convergence of the transform integrals under well-behaved and realizable functions. Applying the inverse Hankel transform to , we obtain:

| (6) |

Alternatively, if we apply the inverse Fourier transform to , we obtain:

| (7) |

where G(ω) is the temporal Fourier transform of any arbitrary shape of g(t). Thus,

| (8) |

for ε ≥ 0. Now, applying Baddour’s Theorem 5 of Baddour (2011):

| (9) |

for ε ≥ 0, and t > 0. Then, assuming g(t) is real, so G(–cε) = G*(cε), and evaluating particle velocity:

| (10) |

for ε ≥ 0, and t > 0. Now, taking the inverse Hankel transform

| (11) |

for ε ≥ 0, r ≥ 0, and t > 0. Assuming g(t) = δ(t) is a temporal impulse, then G*(ω) = 1. Furthermore, from a real intensity pattern Fz(r), we have as a real function. Then, we select the real part of Eqn 11 as the physical component of the wave for r ≥ 0 and t > 0, yielding

| (12) |

for ε ≥ 0, r ≥ 0, and t > 0. Let us assume, for instance, that Fz(r) is a Gaussian-shaped force given by Eqn 2, then . Then, following Chapter 5 of Graff (1975), the constant A0 is scaled by 2c2 and we obtain:

| (13) |

Comparing Eqn 13 with results from Eqn 31 in Parker and Baddour (2014) for the same situation:

| (14) |

which appears identical with the substitution of ε for ω/c. This route of derivation (Eqn 5 – Eqn 14) places simpler interpretations on the functions without the complexities of applying Hermitian properties and causality to the complex Green’s function , a complex Hankel function of the second kind, which contains a singularity at the origin.

Since we used g(t) = δ(t), Eqn 13 is then the temporal impulse response of the system for a Gaussian-shaped beam pattern. Then, the time domain response for an extended push pulse g(t)can be obtained simply by the time domain convolution equation:

| (15) |

for r ≥ 0 and t > 0, νe represents the response to an extended push and νi the impulse response obtained from Eqn 13.

2.3. Green’s function in a lossy medium

In this case, we examine the conventional approach where the complex wave number is defined as:

| (16) |

where cp(ω) is the phase velocity, α(ω) the attenuation, and the frequency dependence of both is dispersive and linked by the Kramers-Kronig equations (Szabo 1995). Assuming small dispersion such that cp(ω) ≅ c0, where c0 is a constant real speed value with dimensionality of m/s, and using the first order Taylor approximation of attenuation such that α(ω) ≅ ωα1, where α1 dimensionality is in (Np/m)/(rad/s), Eqn 16 becomes

| (17) |

Following the notation of Eqn 4, the complex wave number in a viscoelastic medium is defined as , where is the complex speed. Then, using Eqn 17, we find

| (18) |

Taking the Hankel transform of Eqn 4 for the viscoelastic case, we obtain:

| (19) |

where , ε is the spatial frequency, and .

Applying the inverse Fourier Transform to Eqn 19, we obtain:

| (20) |

From Baddour’s Theorem 6 (Baddour 2011) for complex wave number with positive real part, and solving for t > 0, we have

| (21) |

Applying the temporal derivative to Eqn 21 in order to calculate particle velocity, and replacing with Eqn 18, we obtain

| (22) |

Defining Fz(r) as a Gaussian-shaped force given by Eqn 2, and g(t) = δ(t) as a temporal impulse, then . After applying the inverse Hankel transform on the real part of Eqn 22, we obtain:

| (23) |

which is an attenuated version of Eqn 13, under small dispersion, and weak attenuation assumptions. We note as well that Eqn 23 is consistent with Eqn 45 of Parker and Baddour (2014), under the weak dispersion assumption, despite the different approach taken therein to the solution. That comparison is made in more detail in Appendix 1.

3. Methods

3.1. Sample preparation and mechanical measurements

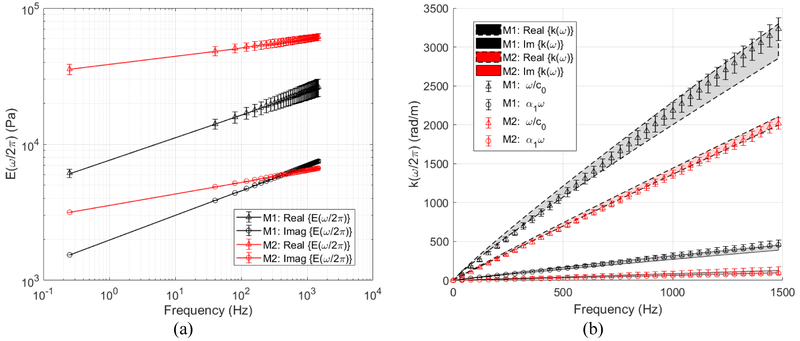

For the analysis, two tissue-mimicking phantoms were selected and used in experiments. A lossy viscoelastic phantom material M1 (model no. 16410001, CIRS, Inc., Norfolk, VA, USA), and a lossless aqueous viscoelastic phantom material M2 (Aquaflex US del pad, Parker Laboratories Inc., Fairfield, NJ, USA). The frequency-dependent Young’s modulus of each phantom was measured using a stress-relaxation by compression test. The measurement was conducted using a MTS Q-Test/5 Universal Testing Machine (MTS, Eden Prairie, MN, USA) with a 5 N load cell using a compression rate of 0.5 mm/s, a strain value of 5%, and total measurement time of 600 s. The stress-time plots obtained by the machine were fitted to a three parameter Kelvin-Voigt fractional derivative (KVFD) model (Zhang et al. 2008) for the calculation of frequency-dependent complex Young’s modulus given as

| (24) |

where E0 is the relaxed elastic constant, η is the viscous parameter, and τ is the order of fractional derivative. has the same form as , and , where Es(ω) and El(ω) are called the Young’s storage and loss moduli, respectively. Measurements were conducted in three samples of each phantom type in order to calculate the mean and standard deviation (error) for each predicted frequency-dependent result. Estimations of the three parameters of the KVFD model for phantom materials M1 and M2 (Table 1) are used to calculate the real and imaginary part of Eqn 24, plotted versus frequency in Figure 2a. Then, for a nearly incompressible (Poisson’s ratio close to 0.5), homogeneous, and isotropic medium, the complex velocity of the shear wave for each phantom with a material density of ρ can be calculated (Parker et al. 2011) as , and the complex wave number of Eqn 16 can be expressed as

| (25) |

where (see Appendix 2 for details of the derivation). For both phantom materials, ρ = 1 g/cm3. The complex wave number from Eqn 25 is plotted in Figure 2. Herein, c0 and α1 are estimated by fitting Real to ω/c0, and to ωα1, respectively, over a frequency range from 0 Hz to 1500 Hz. Both components, ω/c0 and ωα1, come from the Taylor approximation of described in Eqn 17 and are estimated for both phantom materials M1 and M2 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Mechanical testing results in phantom materials M1 and M2. Kelvin-Voigt fractional derivative parameters (left col.) and complex wave number parameters (right col.) are shown for both materials. For all cases, ρ = 1 g/cm3 and incompressibility was assumed. All experiments were performed at room temperature (25 °C).

| Stress relaxation test: Kelvin-Voigt fractional derivative model parameters |

Complex wave number: |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E0 (kPa) | η (kPa sα) | τ | c0 (m/s) | ||

| M1 | 0.711 ± 0.481 | 5.203 ± 0.852 | 0.178 ± 0.028 | 2.88 ± 0.03 | 0.049 ± 0.001 |

| M2 | 9.969 ± 9.661 | 24.928 ± 12.217 | 0.086 ± 0.025 | 4.61 ± 0.02 | 0.009 ± 0.002 |

Figure 2.

Log-log of frequency-dependent complex Young’s modulus (a) and complex wave number (b) for both phantom materials M1 and M2, obtained from mechanical measurements using a stress relaxation by compression test. ω = 2πf, and f = frequency. Frequency-dependent results are predictions of the Kelvin-Voigt fractional derivative model and do not represent independent measurements over the frequency range.

3.2. Numerical integration

Given Eqn 23, calculations of space-time representations of particle velocity νz(x, t) for a Gaussian-shape force (σ = 0.338 mm) and g(t)= δ(t) are performed using numerical integration in MATLAB (The MathWorks, Inc. Natick, MA, USA). Radial spatial (r) and temporal (t) variables are set to range [−4.5; 4.5] mm (200 samples), and [0; 5] ms (400 samples), respectively. c0 and α1 are chosen from Table 1 for M1, and M2, accordingly. Then, Eqn 15 is used to convolve results provided by Eqn 23 (impulse response) with g(t), for the following cases: (1) phantom material M1, temporal rectangular pulse , with τM1 = 1 ms, and (2) phantom material M2, temporal rectangular pulse of τM2 = 0.1 ms.

3.3. Finite element simulation

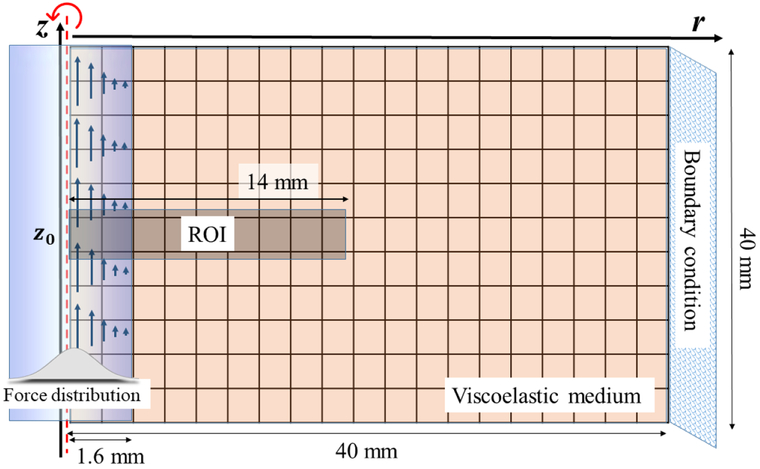

Numerical simulations of shear wave propagation under an axisymmetric Gaussian force were conducted using finite elements in Abaqus/CAE version 6.14-1 (Dassault Systems, Vélizy-Villacoublay, France). A 2D axisymmetric deformable part was created and subjected to a Gaussian distribution body force with σ = 0.338 mm along the symmetry line (see Figure 3). The outer vertical border was subjected to encastre boundary conditions (zero displacement and rotation). The model was meshed using approximately 13280 hybrid, linear and quadrilateral-dominant elements (CAX4RH). Time domain viscoelastic material properties were chosen to characterize phantom materials M1 and M2, which are shown in Table 2 together with the selected density and Poisson’s ratio. Frequency-dependent Young’s modulus extracted from mechanical measurements in Section 3.1 (Figure 2a) for M1 and M2 were provided as tabular data: ωR(h*) = El/E∞, and ωI(h*) = 1 – Es/E∞, as function of f = ω/2π, where E∞ is the long-term Young’s modulus, also known as the quasi-static Young’s modulus Es(ω ≈ 0). For the analysis, E∞ is considered E0 (Table 1). The details on ωR(h*) and ωI(h*) parameters required by Abaqus/CAE for the viscoelastic material definition are explained in Appendix 3.

Figure 3.

Schematic of a 2D finite element axisymmetric deformable part subjected to a Gaussian-shaped pulse in Abaqus/CAE version 6.14-1. Space-time representations of particle velocity νZ0 (r, t) were calculated in the region of interest (ROI).

Table 2.

Viscoelastic material parameters of phantom materials M1 and M2 in Abaqus/CAE version 6.14-1. The frequency-dependent parameters for each material were provided as tabular data: ωR(h*) = El/E∞, and ωI(h*) = 1 – Es/E∞, as function of f = ω/2π, where E∞ is the long-term Young’s modulus.

| Density, ρ (kg/m3) |

Poisson’s ratio, ν |

Long-term Young’s modulus, |

Frequency-dependent tabular parameters |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E∞ (kPa) | ωR{h*} | ωI{h*} | |||

| M | 998 | 0.499 | 0.711 | El/E∞ | 1 – Es/E∞ |

| M2 | 998 | 0.499 | 9.969 | ||

The type of simulation was selected to be dynamic-implicit for a time range of 15 ms in order to let the shear waves propagate along the medium without producing reflections from the outer boundaries. Similarly, as in Section 3.2, two sets of simulation were conducted: (1) phantom material M1, temporal rectangular pulse , with τM1 = 1ms, and (2) phantom material M2, temporal rectangular pulse of τM2 = 0.1ms. For both cases, the body force distribution was set to be , with σ = 0.338 mm. Space-time representations of particle velocity νZ0(r, t) were calculated in both cases at depth z0 crossing through the middle of the medium along the xy-plane.

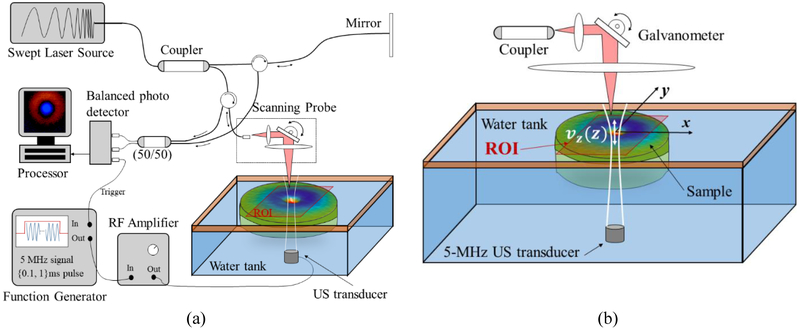

3.4. Experimental setup and acquisition

The experimental setup is shown in Figure 4a. A 5 MHz confocal ultrasonic transducer (PIM7550-2inchFL, Dakota Ultrasonics, Scotts Valley, CA, USA) with 5.01 cm of focal length was excited with a τ = {0.1, 1} ms sinusoidal tone of 5 MHz provided by a function generator (AFG320, Tektronix, Beaverton, OR, USA), representing shorter and longer acoustic push pulses. The generator was connected to a RF power amplifier (25A250, Amplifier Research, Souderton, PA, USA) in order to produce an approximate Gaussian, radially symmetric (σ = 0.338 mm) focused ARF push within the phantom up to the air-solid surface interface of the phantom. The ultrasonic transducer was coupled to the sample with saline water as shown in Figure 3b. A phase-sensitive optical coherence tomography (PhS-OCT) system implemented with a swept source laser (HSL-2100-WR, Santec, Aichi, Japan) with a center wavelength of 1318 nm was used to acquire 3D motion (particle velocity) frames of the sample within a region of interest (ROI) of 9 × 9 mm in the xy-plane, at a depth z0 = 2 mm in the z-plane. The OCT acquisition and the excitation of the 5 MHz transducer were triggered by the computer controlling the entire process. Details of the OCT system are provided in Appendix 4.

Figure 4.

Experimental setup. (a) PhS-OCT system implemented with a swept-source laser for motion detection. (b) Placement of the phantom in a water tank, ARF US-transducer, and region of interest (ROI). Motion is produced close to the surface of the sample.

The ARF push was focused at a certain (x0, y0) position in the sample’s surface (Figure 4b), and it produced a localized out-of-plane vertical displacement that generated a cylindrically-shaped Rayleigh wave propagating within the ROI (Zvietcovich et al. 2016). The relationship between shear wave and Rayleigh wave phase speed in a linear isotropic medium for a Poisson’s ratio ν ≈ 0.5 is given by (Viktorov 2013)

| (26) |

For all cases, we used Eqn 26 to correct Rayleigh wave speed to shear wave speed.

The M-B mode acquisition approach, as described in Zvietcovich et al. (2017b), is used for generating x-axis space-time representations of particle velocity νZ0 (x, t) at the given depth z0 = 2 mm crossing the center of the ARF excitation (x0, y0). Then, νZ0 (x, t) is equivalent to νZ0 (r, t) in cylindrical coordinates due to the axisymmetric shape of the force. Each space-time representation spans 200 locations in the x-axis (9 mm), and M = 100 time samples (5 ms). To reduce noise, experimental results for both M1 and M2 cases were subjected to a local regression filtering approach using weighted linear least squares and a 1st degree polynomial model with a kernel size of 10% of the time signal size. Two cases are analyzed using the proposed experimental setup: (1) phantom material M1, temporal rectangular pulse , with τM1 = 1 ms, and (2) phantom material M2, temporal rectangular pulse of τM2 = 0.1 ms.

4. Results

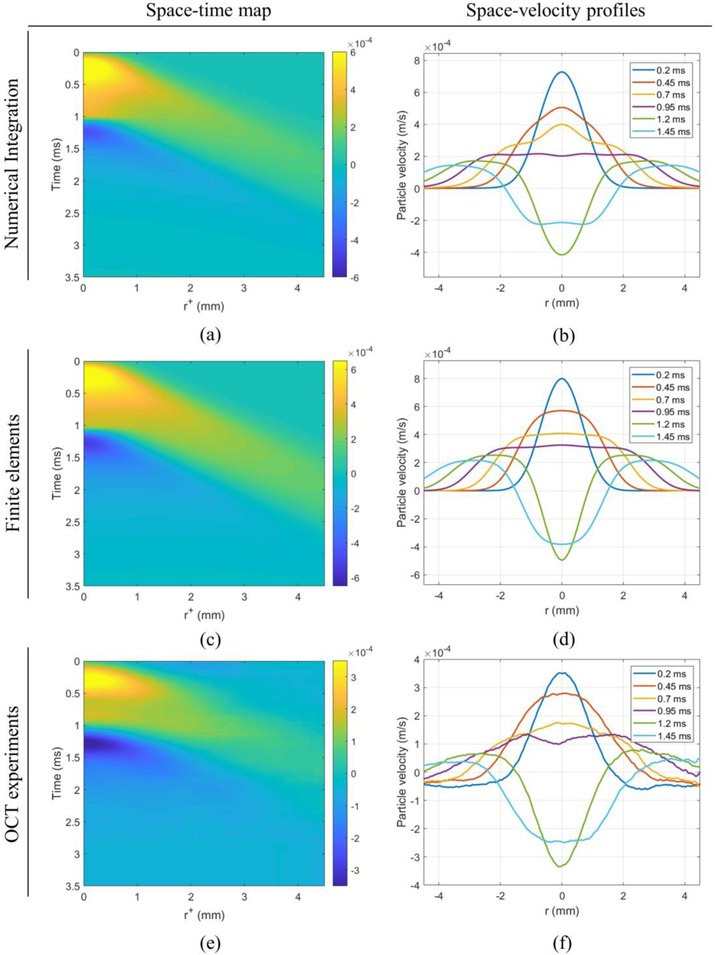

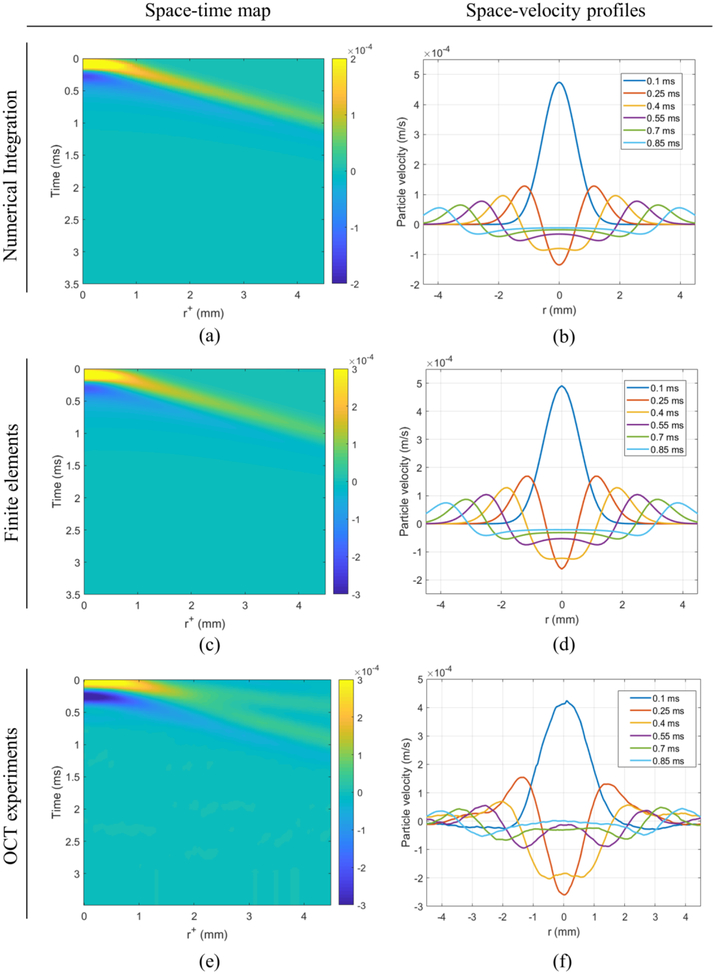

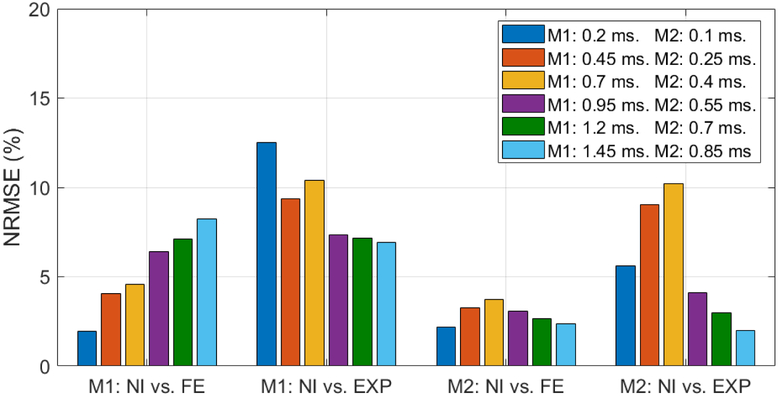

Wave propagation results were evaluated using parameters provided in Table 1 for the proposed material M1 and M2 in three cases: (1) numerical integration using the proposed forward model, (2) simulations using finite elements in Abaqus/CAE, and (3) experiments in phantoms using an OCT imaging system. Particle velocity νz(r, t) is displayed in the form of space-time maps (left column), and space-velocity profiles for various time instants (right column) in Figure 5 and Figure 6 for material M1, and M2, respectively. In all cases, the applied body force has a Gaussian shape described in Eqn 2 with a fixed σ = 0.338 mm. The time application of the body force is set to be a rect function starting at t = 0 s and a duration of τM1 = 1 ms for M1 (Figure 5), and τM2 = 0.1 ms for M2 (Figure 6). Normalized root-mean-square error (NRMSE), expressed as a percentage, is computed in curves provided by simulations and experiments, taking curves obtained using numerical integration as reference, for each phantom material case for further comparison as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 5.

Shear wave propagation in a medium material M1 in the form of space-time maps (left column), and space-velocity profiles for various time instants (right column). Motion is shown as particle velocity νz(r, t) for an input Gaussian body force of σ = 0.338 mm applied for a time duration of τM1 = 1ms. Color bars represent particle velocity in m/s. Legends in all plots (right column) correspond to time snapshot at six uniformly separated time instants.

Figure 6.

Shear wave propagation in a medium material M2 in the form of space-time maps (left column), and space-velocity profiles for various time instants (right column). Motion is shown as particle velocity νz (r, t) for a input Gaussian body force of σ = 0.338 mm applied for a time duration of τM1 = 0.1 ms. Color bars represent particle velocity in m/s. Legends in all plots (right column) correspond to time snapshot at six uniformly separated time instants.

Figure 7.

Quantitative comparison of numerical integration (NI) curves versus finite elements (FE) and OCT experiments (EXP) for each time instant and phantom material M1 and M2. Normalized root-mean-square error, shown as percentage, is used for the analysis of discrepancies between curves.

5. Discussion

A good agreement in wave propagation profiles between numerical integration of the proposed forward model, simulations using finite elements, and experiments in phantoms demonstrate the validity of our approach for two types of viscoelastic material excited by the same Gaussian-shaped force applied at two different duration times. However, a perfect match between the three cases is not expected for a number of reasons (see Figure 7). First, the proposed forward model assumes negligible dispersion: cp(ω) ≅ c0, and a first order Taylor approximation of attenuation α(ω) = α1ω which constrains our model to a frequency band that satisfies those conditions. In addition, simulations using finite elements are conducted using frequency-dependent material properties provided by mechanical testing and a rheological model. Although the appropriateness of using a Kelvin-Voigt fractional derivative model to describe the material behavior of M1 and M2 has been demonstrated by the higher fitting quality (0.999) compared with other rheological models (Voigt, Kelvin-Voigt, Zennerm Standard Linear Solid, and Standard Linear Solid Fractional Derivative), the standard error of the measurements during mechanical testing can be relevant for the comparison at higher frequencies (see Figure 2b). Finally, when experimental results are compared to our approach, a scaling factor of ½ is found between Figure 5f and 5b for the M1 case, and a scale factor of 7/8 is found between Figure 6f and 6b for M2. Particle velocity data in phantoms using an OCT imaging system are obtained only a few millimeters below the surface of the phantom. Although we applied the Rayleigh-to-shear speed correction (Eqn 26), other surface wave properties such as non-zero particle velocity in the r-direction can be pointed to as an experimental source of disagreement.

Other limitations of this study include the imprecise knowledge of the experimental parameters related to the beam pattern and the viscoelastic materials, and the limited number of cases in the study. A larger range of beam widths and viscoelastic materials will be required to more carefully determine the limits of applicability of the model. Furthermore, the theory applies to homogeneous and isotropic materials. Strongly anisotropic tissues such as muscle will require additional analyses.

6. Conclusion

The proposed forward model, under axisymmetric source conditions and the other negligible dispersion assumptions, offers a convenient compromise between simplicity and accuracy by avoiding the complex Hankel function with a singularity at the origin, by using two material parameters to characterize viscoelastic media and performing one numerical integration of a simple function. Summarizing our findings, for an axisymmetric intensity force source Fz(r) applied during an impulsive time, the shear wave particle velocity pattern can be expressed as either a spatial or a temporal transform.

| (27) |

or

| (28) |

for an elastic medium. For a viscoelastic and weakly attenuating medium with negligible dispersion, the shear wave particle velocity pattern is expressed as

| (29) |

or

| (30) |

Furthermore, the form of the key Eqns (12) and (23) can be interpreted as the inverse Hankel transform of zeroth order of a modulated source term. As such, there are a number of efficient algorithms associated with the discrete Hankel transform that can be applied (Johnson 1987). Therefore, the proposed model can be efficiently implemented without the need for treating singularities of the Green’s function, or excluding the source region. As such, these are useful for inverse-fitting problems in order to estimate c0 and α1 of a selected material based on the particle velocity space-time propagation plots. In addition, the model can be tailored to any other force application time g(t)by performing the simple convolution described in Eqn 15. Future work will concentrate on extending this model for non-axisymmetric conditions, and validating it for the study of skin conditions, liver fibrosis, and corneal keratoconus.

Acknowledgements

The instrumentation engineering development of this research benefited from support of the II-VI Foundation. This work was supported by the Hajim School of Engineering and Applied Sciences at the University of Rochester. Fernando Zvietcovich is supported by Fondo para la Innovacion, la Ciencia y la Tecnologia FINCyT 097-FINCyT-BDE-2014 (Peruvian Government). Prof. Baddour was supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (RGPIN-2016-04190).

Appendix 1

Here we demonstrate the dual nature of the attenuated integral formulas from this derivation and an earlier approach by Parker and Baddour (2014). In this earlier work, under the assumption of first order dispersion (i.e. c ≅ c0 + c1ω) and some approximate simplifications of the Hankel function of complex arguments, their Eqn 43 is re-written here for a Gaussian function as

| (A1.1) |

Now, if we apply the small dispersion assumption, then c ≅ c0, and c1 = 0, and calculate particle velocity νz(r, ω) = iωuz(r, ω), we find:

| (A1.2) |

Using the general constraint for real and causal functions in the inverse Fourier transform (Eqn 23 from Parker and Baddour 2014), expanding the function into its Y0 and J0 components, and then identifying the J0 function as the real part of this Fourier integrand, we find:

| (A1.3) |

which appears identical to Eqn 23 when substituting ε for ω/c0, the constant A0 is scaled by 2c2, and the attenuation term is replaced by e−α1∣ω∣r in Eqn 23. This duality has been described before by Blackstock (2000) where the attenuation of propagating waves can alternatively and equivalently be assigned either as a function of space or time.

Appendix 2

As explained in Section 3.1, the derivation of Eqn 25 is conducted by assuming a complex Young’s modulus , and a nearly incompressible (Poisson’s ratio close to 0.5), homogeneous, and isotropic medium, where the complex velocity of the shear wave is described as . Then, the complex wave number can be expressed as:

| (A2.1) |

where is the complex conjugate of , and ∣∣ is the modulus of . Then, using identity 3.7.27 (Abramowitz and Stegun 1965), can be represented as

| (A2.2) |

Substituting Eqn A2.2 into Eqn A2.1 we have:

which is equivalent to Eqn 25 in the manuscript.

Appendix 3

In Abaqus/CAE, the viscoelastic behavior of material can be defined in tabular form by giving real and imaginary parts of ωg*(ω). As defined in the 22.7.2 section of the Abaqus user manual (ABAQUS/CAE 6.14 User's Manual, Online Documentation Help: Dassault Systèmes), g(ω) is the Fourier transform of the non-dimensional shear relaxation function , where GR(t) is the time-dependent shear relaxation modulus, and ω = 2πf is the angular frequency. Then, ωR(g*) = Gl/G∞, and ωI(g*) = 1 – Gs/G∞, where R(·) and I(·) are the real and imaginary part operators, respectively, and the complex shear modulus is defined as . Subscripts s and l refer to the storage and loss moduli, respectively. Since we are assuming a nearly incompressible material, , and we can redefine the tabular parameters as ωR(h*) = El/E∞ and ωI(h*) = 1 – Es/E∞, where the complex Young’s modulus is defined as . We have changed the notation from g* to h* to stress the change to Young’s modulus and avoid confusion with the previously defined g(t) in the manuscript as the temporal application of force. Finally, the tabular form ωR(h*) and ωI(h*) parameters can be provided to Abaqus as a function of f = ω/2π, since Es, El, and E∞ are already obtained from mechanical measurements (Section 3.1).

Appendix 4

The PhS-OCT characteristics include a full-width half-maximum (FWHM) bandwidth of 125 nm, and a light source frequency sweep rate of 20 kHz. The source power that entered the OCT interferometer was split by a 10/90 fiber coupler into the reference and sample arms, respectively. In the reference arm, a custom Fourier domain optical delay line was used for dispersion compensation. In the sample arm, a collimated light beam diameter of 6.7 mm at 1/e2 was directed onto a test phantom by a focusing imaging lens (LSM05, Thorlabs Inc., Newton, NJ, USA), coupled with a galvanometer scanning mirror placed at the front focal plane of the imaging lens to achieve telecentric scanning. The back-scattered light from the sample was recombined with the light reflected from the reference mirror with a 50/50 fiber coupler. The time-encoded spectral interference signal was detected by a balanced photo-detector (1817-FC, New Focus, CA, USA), and then digitized with a 500 Msamples/s, 12-bit-resolution analog-to-digital converter (ATS9350, AlazarTech, Pointe-Claire, QC, Canada). The maximum sensitivity of the system was measured to be 112 dB (Yao et al. 2015). The imaging depth of the system was measured to be 5 mm in air (−10 dB sensitive fall-off). The optical lateral resolution was approximately 30 μm, and the FWHM of the axial point spread function after dispersion compensation was 10 μm. The synchronized control of the galvanometer and the OCT data acquisition was conducted through a LabVIEW platform (National Instruments, Austin, TX, USA) connected to a workstation. The phase stability of the system was calculated as the standard deviation of the temporal fluctuations of the Doppler phase-shift (Δϕerr) while imaging a static structure (Meemon et al. 2010). Results show Δϕerr = 4.6 mrad when using the Loupas’ algorithm (Loupas et al. 1995). The displacement sensitivity is measured as the minimum detectable axial particle displacement (uz,min). We found uz,min = 0.358 nm. Finally, the maximum axial displacement supported by the system without unwrapping the phase-shift signal (Δϕmax = π) is uz,max = 0.24 μm.

References

- Abramowitz M, & Stegun IA (1965). Handbook of Mathematical Functions: With Formulas, Graphs, and Mathematical Tables: Dover Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Baddour N (2011). Multidimensional wave field signal theory: Mathematical foundations. AIP Advances, 1(2), 022120. [Google Scholar]

- Baddour N (2018). Addendum to foundations of multidimensional wave field signal theory: Gaussian source function. AIP Advances, 8(2), 025313. [Google Scholar]

- Bercoff J, Tanter M, & Fink M (2004). Supersonic shear imaging: a new technique for soft tissue elasticity mapping. IEEE Transactions on Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics, and Frequency Control, 51(4), 396–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackstock DT (2000). Fundamentals of Physical Acoustics: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen EL, & Parker KJ (2014). Physical Models of Tissue in Shear Fields. Ultrasound in medicine & biology, 40(4), 655–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahey BJ, Nightingale KR, McAleavey SA, Palmeri ML, Wolf PD, & Trahey GE (2005). Acoustic radiation force impulse imaging of myocardial radiofrequency ablation: initial in vivo results. IEEE Transactions on Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics, and Frequency Control, 52(4), 631–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graff KF (1975). Wave motion in elastic solids. London: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson HF (1987). An improved method for computing a discrete Hankel transform. Computer Physics Communications, 43(2), 181–202. [Google Scholar]

- Kazemirad S, Bernard S, Hybois S, Tang A, & Cloutier G (2016). Ultrasound Shear Wave Viscoelastography: Model-Independent Quantification of the Complex Shear Modulus. IEEE Transactions on Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics, and Frequency Control, 63(9), 1399–1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leartprapun N, Iyer R, & Adie SG (2017). Model-independent quantification of soft tissue viscoelasticity with dynamic optical coherence elastography. Paper presented at the SPIE BiOS. [Google Scholar]

- Loupas T, Peterson RB, & Gill RW (1995). Experimental evaluation of velocity and power estimation for ultrasound blood flow imaging, by means of a two-dimensional autocorrelation approach. IEEE Transactions on Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics, and Frequency Control, 42(4), 689–699. [Google Scholar]

- Meemon P, Lee K-S, & Rolland JP (2010). Doppler imaging with dual-detection full-range frequency domain optical coherence tomography. Biomedical Optics Express, 1(2), 537–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nenadic IZ, Qiang B, Urban MW, Zhao H, Sanchez W, Greenleaf JF, & Chen S (2017). Attenuation measuring ultrasound shearwave elastography and in vivo application in post-transplant liver patients. Physics in Medicine & Biology, 62(2), 484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nightingale K, Nightingale R, Palmeri M, & Trahey G (1999). Finite element analysis of radiation force induced tissue motion with experimental validation. Paper presented at the 1999 IEEE Ultrasonics Symposium Proceedings. International Symposium (Cat. No.99CH37027). [Google Scholar]

- Ophir J, Srinivasan S, Righetti R, & ThittaiKumar A (2011). Elastography: A decade of progress. Current Medical Imaging Reviews, 7(4), 292–312. [Google Scholar]

- Parker KJ, Doyley MM, & Rubens DJ (2011). Imaging the elastic properties of tissue: the 20 year perspective. Physics in Medicine & Biology, 56(1), R1–R29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker KJ, & Baddour N (2014). The Gaussian Shear Wave in a Dispersive Medium. Ultrasound in medicine & biology, 40(4), 675–684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker KJ, Ormachea J, Will S, & Hah Z (2018). Analysis of Transient Shear Wave in Lossy Media. Ultrasound in medicine & biology, 44(7), 1504–1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarvazyan AP, Rudenko OV, Swanson SD, Fowlkes JB, & Emelianov SY (1998). Shear wave elasticity imaging: a new ultrasonic technology of medical diagnostics. Ultrasound in medicine & biology, 24(9), 1419–1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt C, Hadj Henni A, & Cloutier G (2010). Ultrasound Dynamic Micro-Elastography Applied to the Viscoelastic Characterization of Soft Tissues and Arterial Walls. Ultrasound in medicine & biology, 36(9), 1492–1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo TL (1995). Causal theories and data for acoustic attenuation obeying a frequency power law. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 97(1), 14–24. [Google Scholar]

- Vappou J, Maleke C, & Konofagou EE (2009). Quantitative viscoelastic parameters measured by harmonic motion imaging. Physics in Medicine & Biology, 54(11), 3579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viktorov IA (2013). Rayleigh and Lamb Waves: Physical Theory and Applications: Springer; US. [Google Scholar]

- Wijesinghe P, McLaughlin RA, Sampson DD, & Kennedy BF (2015). Parametric imaging of viscoelasticity using optical coherence elastography. Physics in Medicine & Biology, 60(6), 2293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao J, Meemon P, Ponting M, & Rolland JP (2015). Angular scan optical coherence tomography imaging and metrology of spherical gradient refractive index preforms. Optics Express, 23(5), 6428–6443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M, Nigwekar P, Castaneda B, Hoyt K, Joseph JV, di Sant'Agnese A, Parker KJ (2008). Quantitative Characterization of Viscoelastic Properties of Human Prostate Correlated with Histology. Ultrasound in medicine & biology, 34(7), 1033–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zvietcovich F, Yao J, Rolland JP, & Parker KJ (2016). Experimental classification of surface waves in optical coherence elastography. Paper presented at the SPIE BiOS. [Google Scholar]

- Zvietcovich F, Rolland JP, & Parker KJ (2017). An approach to viscoelastic characterization of dispersive media by inversion of a general wave propagation model. Journal of Innovative Optical Health Sciences, 10(06), 1742008. [Google Scholar]

- Zvietcovich F, Rolland JP, Yao J, Meemon P, & Parker KJ (2017). Comparative study of shear wave-based elastography techniques in optical coherence tomography. Journal of Biomedical Optics, 22(3), 035010–035010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]