Diabetic Retinopathy Telehealth Practice Recommendations Working Group

Second Edition

Editorial Committee:

Helen K. Li, MD (Chair), Mark Horton, OD, MD (Co-chair), Sven-Erik Bursell, PhD, Jerry Cavallerano, OD, PhD, Ingrid Zimmer-Galler, MD, Mathew Tennant, MD

Writing Committees:

Clinical: Jerry Cavallerano, OD, PhD (Chair), Ingrid Zimmer-Galler, MD

Technology: Sven-Erik Bursell, PhD (Chair), Michael Abramoff, MD, PhD, Edward Chaum, MD, PhD, Debra Cabrera DeBuc, PhD

Operations: Mark Horton, OD, MD (Chair), Helen K. Li, MD, Tom Leonard-Martin, PhD, MPH, Mathew Tennant, MD, Marc Winchester, BA

Other Contributors:

Reviewers [R], ATA Standard and Guidelines Committee Members [SG], ATA Staff [S]

Nina Antoniotti, RN, MBA, PhD [Chair, SG]

Jordana Bernard, MBA [S]

David Brennan, MSBE [SG]

Anne Burdick, MD, MPH [SG]

Jerry Cavallerano, OD, PhD [SG]

Brian Grady, MD [SG]

Tom Hirota, DO [SG]

Elizabeth Krupinski, PhD [Vice Chair, SG]

Cindy K. Leenknecht, MS, APRN-CS, CCRP [SG]

Jonathan Linkous, MPA [S]

Lou Theurer [SG]

Jill Winters, PhD, RN [SG]

First Edition

American Telemedicine Association, Ocular Telehealth Special Interest Group, and the National Institute of Standards and Technology Working Group

American Telemedicine Association Executive Committee:

Jonathan D. Linkous, Richard Bakalar, MD, Adam Darkins, MD, Col. Ronald K. Poropatich, MD

American Telemedicine Association Ocular Telehealth Special Interest Group:

Jerry Cavallerano, OD, PhD (Chair), Mary G. Lawrence, MD, M.P.H. (Vice Chair)

Editorial Committee:

Helen K. Li, MD (Co-chair), Mathew Tennant, MD (Co-chair), Sven Bursell, PhD, Jerry Cavallerano, OD, PhD, Mark Horton, OD, MD, Richard Bakalar, MD

Writing Committees:

Clinical: Jerry Cavallerano, OD, PhD (Chair), Mary G. Lawrence, MD, MPH, Ingrid Zimmer-Galler, MD, COL Wendall Bauman, MD

Technology: Sven Bursell, PhD (Chair), W. Kelly Gardner

Operations: Mark Horton, OD, MD (Chair), Lloyd Hildebrand, MD, Jay Federman, MD

National Institute of Standards and Technology:

Lisa Carnahan

Veterans Administration:

Peter Kuzmak, John M. Peters, Adam Darkins, MD

At Large Group Participants:

Jehanara Ahmed, MD, Lloyd M. Aiello, MD, Lloyd P. Aiello, MD, PhD, Gary Buck, Ying Ling Chen, PhD, Denise Cunningham, CRA, RBP, M.Ed., Eric Goodall, Ned Hope, Eugene Huang, PhD, Larry Hubbard, MAT, Mark Janczewski, MD, J.W.L. Lewis, PhD, Hiro Matsuzaki, COL Francis L. McVeigh, OD, Jordana Motzno, Diane Parker-Taillon, Robert Read, Peter Soliz, PhD, Bernard Szirth, PhD, COL Robert A. Vigersky, MD, COL Thomas Ward, MD

American Telemedicine Association Administrative Contributor:

Catherine Diver

Table of Contents

-

REFERENCES

2. Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) Metadata

ABBREVIATIONS

GLOSSARY

1. Preamble

The American Telemedicine Association (ATA), with members from throughout the United States and the world, is the principal organization bringing together telemedicine practitioners, healthcare institutions, vendors, and others involved in providing remote healthcare using telecommunications. The ATA is a nonprofit organization that seeks to bring together diverse groups from traditional medicine, academia, technology and telecommunications companies, e-health, allied professional and nursing associations, medical societies, government, and others to overcome barriers to the advancement of telemedicine through the professional, ethical, and equitable improvement in healthcare delivery.

ATA has embarked on an effort to establish practice guidelines and technical standards for telemedicine to help advance the science and to assure uniform quality of service to patients. Guidelines and standards are developed by panels that include experts from the field and other strategic stakeholders. The guidelines are designed to serve as an operational reference and educational tools to aid providing appropriate care for patients. The guidelines and standards generated by ATA undergo a thorough consensus and rigorous review, with final approval by the ATA Board of Directors. Recommendations will be reviewed and updated periodically.

The practice of medicine is an integration of the science and art of preventing, diagnosing, and treating diseases. Adherence to these guidelines and standards will not guarantee accurate diagnoses or successful outcomes. The purpose of these guidelines and standards is to assist practitioners in pursuing a sound course of action to provide effective and safe medical care founded on current information and evidence-based medicine, available resources, and patient needs. ATA recognizes that safe and effective practice requires specific training, skills, and techniques as described in this document.

The goal of Telehealth Practice Recommendations for Diabetic Retinopathy is to support telehealth programs to improve clinical outcomes and promote reasonable and informed patient and care provider expectations. Recommendations are based on reviews of current evidence, medical literature, and clinical practice. The recommendations are not intended as strict requirements. They may need to be adapted for patient care or situations where more or less stringent interventions are necessary. Recommendations are also not intended to serve as legal advice or as a substitute for legal counsel. This document does not replace sound medical judgment or clinical decision making. Additional information and examples are included in the appendix.

This document is property of ATA. Any reproduction or modification of the published practice guideline and technical standards must receive prior approval by ATA.

2. Introduction

Telemedicine is the use of medical information exchanged from one site to another via electronic communications. Closely associated with telemedicine is the term telehealth, often used to encompass a broader definition of remote healthcare other than clinical service.1 Telehealth holds the promise of increased adherence to evidenced-based medicine, improved consistency of care, and reduced cost. Goals for an ocular telehealth program include preserving vision, reducing vision loss, and providing better access to medical care.

This article presents recommendations for designing, implementing, and sustaining an ocular telehealthcare program. It also addresses current diabetic retinopathy (DR) telehealth clinical, technical, and administrative issues that form the basis for evaluating DR telehealth techniques and technologies. These recommendations are consistent with recent federal legislation and industry best practices that emphasize interoperable health information exchange. This document will be reviewed periodically and revised to reflect evolving technologies, regulations, and clinical guidelines.

3. Background

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a leading cause of death, disability, and blindness in the United States.2,3 It afflicts as much as 8% of the American population4 and the prevalence and incidence of DM is increasing in the United States and worldwide.5–8 The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that there are currently more than 285 million people worldwide with DM and predicts 439 million people with DM by 2030.9 The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that 18 million Americans have diagnosed DM and an additional 6.4 million have the disease but have not yet been diagnosed.5

DR is a microvascular complication of both type 1 and type 2 DM and develops in nearly all persons with DM. For the past 20 years, DR has remained the most common cause of blindness in working age adult populations in the United States and other developed countries. DR is the most frequently occurring microvascular complication of diabetes, affecting nearly all persons with 15 or more years of diabetes.10,11 The WHO estimates that after 15 years of DM, approximately 2% of people with DM become blind, whereas 10% develop severe visual handicap.12 In the Wisconsin Epidemiologic Study of Diabetic Retinopathy (WESDR), 13% of the study population with DM duration less than 5 years and 90% with duration of DM 10–15 years had some level of DR when onset of DM was before age 30 years (presumed to have type 1 DM). For those with onset at age 30 years or older (presumed to have type 2 DM), 40% taking insulin and 24% not taking insulin had some level of DR when the duration of DM was less than 5 years. Eighty-four percent taking insulin and 53% not taking insulin had some level of DR when duration of DM was 15–20 years.13,14 In the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS), which enrolled subjects at the time of diagnosis of DM, nearly 40% of participants had some level of DR at diagnosis.15

DR affects more than 5.3 million Americans over the age of 18 (2.5% of the U.S. population).16 Diabetic macular edema (DME) is a manifestation of DR that may occur in any stage of DR and leads to loss of central vision.17–19 The natural course of DME is characterized by chronic retinal vascular leakage and retinal thickening, often with intraretinal lipid deposition.6 Over a 10-year period in the WESDR, DME was present in 24% of patients. Visually threatening clinically significant macular edema (CSME) was present in 10% of patients. DME is more common in type 2 diabetes patients on insulin than in type 1 diabetes patients, and prevalence increases in both types as the duration of diabetes increases.

The medical, social, and economic ramifications of DR are substantial. Evidence-based treatments in clinical studies spanning 40 years demonstrate ways to virtually eliminate the risk of severe vision loss from proliferative DR. Treatments are also available to significantly reduce the risk of legal blindness and moderate vision loss. For a variety of reasons, effective treatments such as laser surgery are underutilized.

Clearly defined clinical standards for evaluating and treating DR have been established. Major multicenter clinical trials in the United States and United Kingdom provide the science behind DR clinical management.

a. The Diabetic Retinopathy Study

The Diabetic Retinopathy Study (DRS) (1971–1975) demonstrated conclusively that scatter (panretinal) laser photocoagulation reduces the risk of severe vision loss from proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) by as much as 60%.20–22

b. Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study

The Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) (1979–1990) demonstrated that scatter laser photocoagulation could reduce a person's risk of severe vision loss (best corrected vision of 5/200 or worse) to less than 2%. It also demonstrated that focal laser photocoagulation can reduce the risk of moderate vision loss (a doubling of the visual angle) from DME by 50%. There was no adverse effect on progression of DR or risk of vitreous hemorrhage for patients with DM who take up to 650 mg of aspirin per day.23–27

c. Diabetes Control and Complications Trial/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications

The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) (1983–1993) compared conventional blood glucose control to intensive blood glucose control in patients with type 1 DM and little or no DR. The DCCT conclusively demonstrated that for persons with type 1 DM, intensive control of blood glucose as reflected in measurements of glycosylated hemoglobin A1c:

• Reduces the risk of a three-step progression of DR by 54%

• Reduces the risk of developing severe nonproliferative DR (NPDR) or PDR by 47%

• Reduces the need for laser surgery by 56%

Significantly, the Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications (EDIC) study showed that at 10 years after the completion of the DCCT, subjects in the intensive control group continued to show a substantial decrease in risk of progression of DR compared to the conventional control group, despite a near convergence of hemoglobin A1c levels in both groups.35,36

d. The United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study

The UKPDS (1977–1999) demonstrated similar findings to the DCCT for persons with type 2 DM.37,38 As in the DCCT/EDIC studies, a legacy effect was noted, with subjects with intensive control continuing to have a lower risk of microvascular complications despite convergence of A1c levels in the intensive and conventional control groups.39

e. The Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network

The Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research (DRCR) network is a collaborative network funded by the National Eye Institute in the United States to facilitate multicenter clinical research of DR, DME, and associated conditions. The study involves more than 200 centers and 109 active sites nationwide in the United States.40,41 Current and completed studies conducted by the DRCR network are available on the networks Web site.

Because DR is often asymptomatic in its early stages, many people do not seek annual retinal examination as recommended by the American Diabetes Association, the American Academy of Ophthalmology, the American Optometric Association, and other professional societies. Others may lack care due to socioeconomic factors, geographic or travel restrictions, or ignorance of the need for regular retinal examination for DR. It is estimated that 40%–50% of adults with DM in the United States do not receive recommended eye care to diagnose and treat DR.42 Studies also show no major improvement in examination rates over the previous 5 years.

Approximately 26% of patients with type 1 DM and 36 percent with type 2 DM have never had their eyes examined.43 These patients tend to be older, less educated, and more recently diagnosed than those receiving regular eye care.43 They are also likely to live in rural areas and receive healthcare from a family or general practitioner.43 Alarmingly, in one study, 32% of patients with DM at high risk for vision loss had never received an eye examination.44 Upon examination, however, almost 61% exhibit DR, cataract, glaucoma, or other ocular manifestations of DM.

The prevalence of DR is high and the incidence is growing in step with worldwide increases in DM. Loss of vision due to DR has a considerable impact on personal and societal resources. In the United States, approximately 24,000 persons become blind from DM each year. It is estimated that programs to identify and treat DR could annually save the U.S. healthcare budget nearly $400 million.45,46

DR is readily diagnosed by appropriate examination. Film-based retinal imaging has been a mainstay of DR clinical care and research for many years. Digital retinal imagery is a relatively new tool for assessing patients with DR. Seven standard field photography with digital images has been accepted as the standard for the DRCR network. Digital retinal imagery as part of a telehealth program has the potential to increase DR diagnoses, resulting in timely treatment and preservation of vision.

DM and its eye complications provide an ideal model for telehealth initiatives. DR care has a firm foundation in evidenced-based medicine. DR is classified by specific retinal lesions, exacts a significant personal and socioeconomic toll, and is a treatable disease. According to the WHO, telehealth programs are “designed to integrate telecommunications systems into the practice of protecting and promoting health,” whereas “telemedicine programs are designed to integrate telecommunications into diagnostic and therapeutic intervention for the practice of curative medicine.”47 Ocular telehealth and telemedicine have the potential of delivering eye care to those without access. They can also provide enhanced care to those with readily available ocular care. Telehealth programs can establish and enforce quality of care by linking to national clinical trial scientific data; offer education modules to healthcare professionals, patients, and communities; and facilitate recruitment for clinical trials. The American Diabetes Association recognized the value of fundus imaging in its 2010 Clinical Practice Recommendations for DR when they noted:

“High-quality fundus photographs can detect most clinically significant DR. Interpretation of images should be performed by a trained eye care provider. Although retinal photography may serve as a screening tool for retinopathy, it is not a substitute for a comprehensive eye exam, which should be performed at least initially and at intervals thereafter as recommended by an eye care professional.”48

4. Principles of a Telehealth DR Program

Private individuals, public and private institutes, national and international agencies, and individual governments on multiple levels may undertake telemedicine programs for DM and DR. Designing, building, implementing, and sustaining an ocular telehealth DR program requires a clearly defined mission, vision, goals, and guiding principles. The following statements are a guide for leadership and staff in developing and sustaining appropriate and effective programs.

a. Mission

Increase access and adherence to demonstrated standards of care among individuals with DM.

b. Vision

Ocular telehealth can be an integral component of primary care for patients with DM. Ocular telehealth has the potential to expand access to diabetic retinal examinations for individuals with DM consistent with evidence-based recommendations for diabetic eye care (i.e., ETDRS, DCCT-EDIC, UKPDS, and DRCR). Ocular telehealth also has the ability to extend access to diabetes eye care, offer alternative methods for receiving appropriate eye care, and integrate diabetes eye care into patients' total healthcare.

c. Goals

• Reduce the incidence of vision loss due to DR

• Improve access to diagnosis and management of DR

• Decrease the cost of identifying patients with DR

• Promote telehealth to enhance the efficiency and clinical effectiveness of evaluation, diagnosis and management of DR

• Promote telehealth to enhance the availability, quality, efficiency, and cost-effectiveness of remote evaluation for DR

d. Guiding Principles

Although ocular telehealth programs offer new opportunities to improve access and quality of care for people with DR, programs should be developed for deployment in a safe and effective manner. Program outcomes should be closely monitored to meet or exceed current standards of care for retinal examination.

DM adversely affects most parts of the eye and has a diverse influence on visual function. As a component of informed consent, patients should be aware that a validated teleophthalmology examination of the retina might substitute for a traditional onsite dilated retinal evaluation for DR, but it is not a replacement for a comprehensive eye examination. Until telemedicine programs are developed to include all necessary components of a comprehensive eye examination, a periodic, in-person comprehensive eye examination by a qualified provider continues to be essential.

5. Ethics

Regardless of the program, the care of the patient should not be compromised. This responsibility encompasses a broad range of issues including, but not limited to, confidentiality, image quality, data integrity, clinical accuracy, and reliability.

6. Clinical Validation

Multicenter, national clinical trials provide evidence-based criteria for clinical guidelines in diagnosing and treating DR. Telehealth programs for DR should define program goals and performance in relationship to accepted clinical standards. In general, the selection of an ocular telehealth system for evaluating DR should be based on the unique needs of the healthcare setting.

ETDRS 30°, stereo seven-standard field, color, 35 mm slides are an accepted standard for evaluating DR. Although no standard criteria have been widely accepted as performance measurements of digital imagery used for DR evaluation, current clinical trials sponsored by the National Eye Institute have transitioned to digital images for DR assessment. Telehealth programs for DR should demonstrate an ability to compare favorably with ETDRS film or digital photography as reflected in kappa values for agreement of diagnosis, false-positive and false-negative readings, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and sensitivity and specificity of diagnosing levels of retinopathy and macular edema.49–51 Inability to obtain or read images should be considered a positive finding and patients with unobtainable or unreadable images should be promptly re-imaged or referred for evaluation by an eye care specialist. One program reported the majority of patients referred due to unreadable images actually had ocular disease that would have resulted in referral if adequate images had been obtained.52

It is recognized that severity levels of DR other than those defined by the ETDRS are used for grading DR (see Table 1 for comparisons between ETDRS levels of DR and the International Clinical Diabetic Retinopathy Disease Severity Scale, and Table 2 for comparisons between ETDRS DME and the International Clinical Diabetic Retinopathy Disease Severity Scale).53 Protocols should state the reference standard used for validation and relevant datasets used for comparison.

Table 1.

International Clinical Diabetic Retinopathy Scale Compared to Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study Levels of Diabetic Retinopathy

| INTERNATIONAL CLASSIFICATION LEVEL OF DR | ETDRS LEVEL OF DR |

|---|---|

| No apparent retinopathy | Levels 10, 14, 15; DR absent |

| Mild NPDR | Level 20; very mild NPDR |

| Moderate NPDR | Levels 35, 43, 47; moderate NPDR |

| Severe NPDR | Levels 53A-E; severe NPDR, very severe NPDR |

| PDR | Levels 61,65,71,75,81,85; PDR, high-risk PDR, very severe, or advanced PDR |

DR, diabetic retinopathy; NPDR, nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy; PDR, proliferative diabetic retinopathy; ETDRS, Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study.

Table 2.

International Clinical Diabetic Macular Edema Scale Compared to Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study Where Noted

| DISEASE SEVERITY LEVEL | FINDINGS | DME SCALE |

|---|---|---|

| DME apparently absent | No apparent retinal thickening or hard exudates (HE) in posterior pole | |

| DME apparently present | Some apparent retinal thickening or HE in posterior pole | Mild DME: some retinal thickening or HE in posterior pole but distant from center of the macula (ETDRS: DME but not CSME) |

| Moderate DME: retinal thickening or HE approaching the center but not involving the center (ETDRS: CSME) | ||

| Severe DME: retinal thickening or HE involving the center of the macula (ETDRS: CSME) |

DME, diabetic macular edema; HE, hard exudates; CSME, clinically significant macular edema.

Telehealth Practice Recommendations for Diabetic Retinopathy recognizes four categories of validation for DR telehealth programs using ETDRS 30°, stereo seven-standard field, color, 35 mm slides as a reference standard. Validation category signifies a program's overall clinical performance and goal. Information about the program's validation performance should be available to users.

a. Category 1

Category 1 validation indicates a system can separate patients into two categories: (1) those who have no or very mild NPDR (ETDRS level 20 or below), and (2) those with levels of DR more severe than ETDRS level 20. Functionally, Category 1 validation allows identification of patients who have no or minimal DR and those who have more than minimal DR.

b. Category 2

Category 2 validation indicates a system can accurately determine if sight-threatening DR is present or not present as evidenced by any level of DME, severe or worse levels of NPDR (ETDRS level 53 or worse), or proliferative DR (ETDRS level 61 or worse).25 Category 2 validation allows identification of patients who do not have sight-threatening DR and those who have potentially sight-threatening DR. Patients with sight-threatening DR generally require prompt referral for management.

c. Category 3

Category 3 validation indicates a system can identify ETDRS defined levels of NPDR (mild, moderate, or severe), proliferative DR (early, high-risk), and DME with accuracy sufficient to determine appropriate follow-up and treatment strategies. Category 3 validation allows patient management to match clinical recommendations based on clinical retinal examination through dilated pupils.

d. Category 4

Category 4 validation indicates a system matches or exceeds the ability of ETDRS photos to identify lesions of DR to determine levels of DR and DME. Functionally, Category 4 validation indicates a program can replace ETDRS photos in any clinical or research program.

A telehealth program's validation category impacts clinical, business, and operational features. The category influences hardware and software technology, staffing and support, clinical workflow and outcomes, quality assurance, and business plan. Equipment cost, technical difficulty, and training requirements are likely higher in categories that allow patient management to match clinical recommendations based on clinical retinal examination through dilated pupils.

A telehealth program's goals and desired performance may influence choice of technology and protocol. Some programs use pupil dilation. Others perform imaging with nonmydriatic cameras and undilated pupils. A higher rate of unreadable photographs has been reported through undilated versus dilated pupils.54,55 Diabetic persons often have smaller pupils and a greater incidence of cataracts, which may limit image quality if performed through an undilated pupil. Pupil dilation is associated with a very small risk of angle-closure glaucoma. Although the risk of inducing angle-closure glaucoma with dilation using 0.5% tropicamide is minimal with no reported cases in a large meta-analysis,56 programs using pupil dilation should have a defined protocol to recognize and address this potential complication.

Depending on the telehealth program, images may or may not be acquired and reviewed stereoscopically. There has been concern that macular edema may not always be detectable through nonstereo imaging modalities.57 One approach without stereoscopic evaluation relies on hard exudates in the central macular field or within one disc diameter of the center of the macula as a surrogate marker for macular edema.58 CSME is often accompanied by other DR lesions that may also independently trigger referral. It is, therefore, possible that a program without stereoscopic capabilities may be validated to identify macular edema with acceptable sensitivity.

7. Communication

Communication is the foundation of ocular telehealth.59 Communication should be coordinated and reliable between originating and distant sites, telehealth providers and patients, and telehealth providers and other members of the patient's healthcare team. Providers interpreting retinal telehealth images should render reports in accordance with relevant jurisdictions and community standards.

8. Personnel Qualifications

Telehealth programs for DR depend upon a variety of functions. Distinct individuals may assume these responsibilities or a person may assume several roles.

a. Medical Care Supervision

An ophthalmologist with expertise in evaluation and management of DR usually assumes ultimate responsibility for the program and is responsible for oversight of image interpretation and patient well-being. Responsibilities include recommendations for appropriate care management and providing feedback to the imager and program to ensure images are of appropriate quality.

b. Patient Care Coordinator

The patient care coordinator ensures that each patient receives DR education and complete and appropriate follow-up, especially for those meeting criteria for referral.

c. Image Acquisition

Image acquisition personnel (“imagers”) are responsible for acquiring retinal images. A licensed eye care professional may not be physically available at all times during a telehealth session. Imagers should possess knowledge and skills for independent imaging or with assistance and consultation by telephone, including

• Understanding basic ocular telehealth technology and principles

• Demonstrated qualifications for obtaining appropriate image fields of diagnostic quality

• Understanding the clinical appearance of common retinal diseases requiring immediate evaluation

• Communication skills for patient informed consent and education

• Understanding of angle closure glaucoma if pupil dilation is performed, including entry-level skills in screening for shallow anterior chamber and recognition of angle closure signs and symptoms

d. Image Review and Evaluation

Image review and evaluation specialists are responsible for timely grading of images for retinal lesions and determining levels of DR. Only qualified readers should perform retinal image grading and interpretation. Qualification should include academic and clinical training. If a reader is not a licensed eye care provider, specific training is required. Grading skills should be appropriate to technology used in the ocular telehealth program. A licensed, qualified eye care provider with expertise in DR and familiarity with program technology should supervise readers. An adjudicating reader may resolve ambiguous or controversial interpretation. In most cases, an adjudicating reader will be an ophthalmologist with special qualifications in DR by training or experience.

e. Information Systems

An information systems specialist is responsible for connectivity, data integrity, availability of stored images, and disaster recovery.60,61 The specialist should be available in case of system malfunction to solve problems, initiate repairs, and coordinate system-wide maintenance.

9. Equipment Specifications

Telehealth systems used in the United States should conform to Federal Drug Administration regulations. Telehealth systems used inside and/or outside the United States should meet applicable international, American, and local statues, regulations, and accepted standards. Elements include

• Image acquisition hardware (computers, cameras and other peripherals)

• Image transmission, storage and retrieval systems

• Image analysis and clinical workflow management (scheduling follow-up examinations, clinical communication management, and decision support tools)

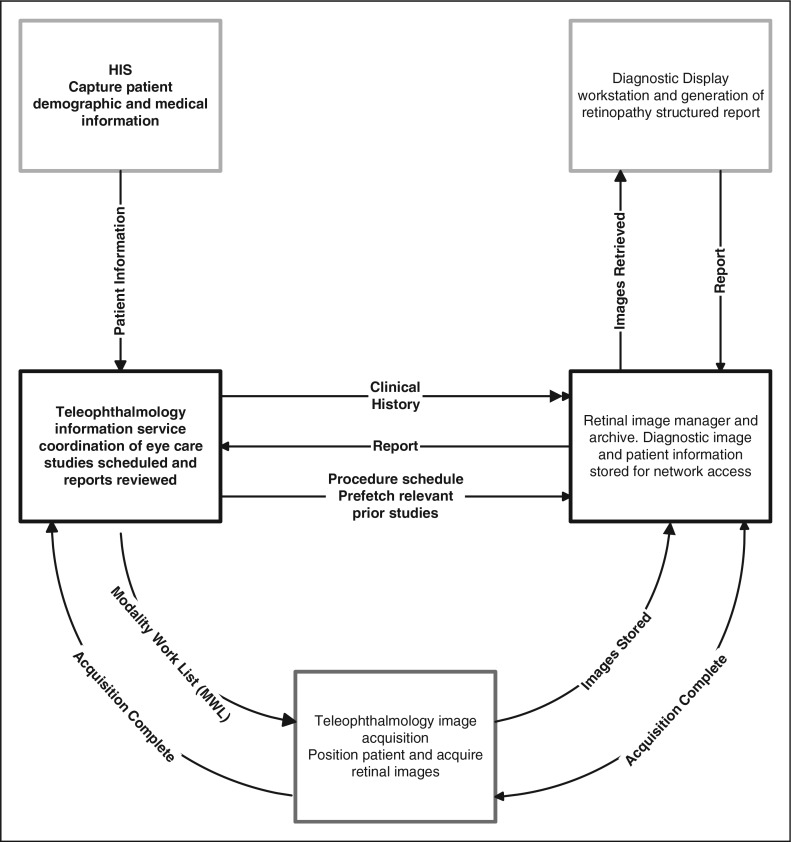

Equipment specifications will vary with program needs and available technology (Fig. 1). Equipment should provide image quality and availability appropriate for clinical needs and guidelines. The diagnostic accuracy of any imaging system should be validated before incorporation into a telehealth system.49–51,62,63

Fig. 1.

Example of a workflow diagram of an ocular telehealth system based on Integrating the Healthcare Enterprise (IHE) infrastructure for radiology. Despite variations between equipment, communications, and information systems, a generalized workflow diagram is possible for any ocular telehealth system. HIS, hospital information system.

Technologies should be Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM; An international standard for distributing, storing, and viewing medical images) and Health Level 7 (HL 7; An international framework for the electronic exchange of clinical, financial, and administrative information among computer systems in hospitals, clinical laboratories, pharmacies, etc.) standards compliant. New equipment and periodic upgrades to incorporate expanded DICOM standards should be part of an ongoing quality-control program. DICOM Supplement 91 (Ophthalmic Photography), which addresses ophthalmic digital images, was released in 2004 and updated in 2009.64

a. Interoperability

An integrated digital healthcare system is increasingly an expectation of patients, providers, and regulators. Integration occurs on several levels, leading to more than one definition of interoperability. The U.S. Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH; Legislation designed to promote the adoption and meaningful use of health information technology) Act mandates specific measures of interoperability for electronic health records (EHR). HITECH includes personal health records in broad scale health information exchange.

Interoperability also impacts the ability to interconnect devices and computer applications with EHR and practice management systems. Terminology, hardware, software, and communication standards are required. Harmonization of these standards is needed to allow information exchange between systems and interoperable use of data by devices and software from different vendors. Conformance to standards is increasingly driven by federal regulations and market influences. DR ocular telehealth systems should include nonproprietary interoperability by using components that conform to

• DICOM™65

• HL766

• Integrating the Healthcare Enterprise (IHE; A global initiative by healthcare professionals and industry to improve computer sharing of healthcare information through coordinated use of established standards such as DICOM and HL7) Eye Care67,68

• Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine (SNOMED-CT™; A system of clinical healthcare terminology covering diseases, findings, procedures, microorganisms, pharmaceuticals, etc.)69

• Health Information Technology Standards Panel (HITSP; A public and private sector partnership working toward interoperability between clinical and business health information systems. HITSP is coordinated through the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services' Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONCHIT))70

Conformance to standards does not ensure interoperability. Also, interoperability of electronic medical records, EHR, and personal health records may not always be possible or practical. Exchange of DR images and reports can also be accomplished through physical media as provided by HITSP Interoperability Specification, IS 05-Consumer Empowerment and Access to Clinical Information via Media.70 Additional information about interoperability is available in Appendix 1.

b. Image Acquisition

Retinal image datasets should adhere to DICOM standards. Patient information, eye and retina characteristics, image type, and other data should be linked to image files as metadata.64 Retinal evaluation data defining type of retinal examination and the retinal image set should be included and linked to image files as metadata. Additional information such as medical and surgical history and laboratory values may be included as metadata with an image set (Appendix 2).

c. Compression

Data compression may facilitate transmission and storage of retinal images. Compression may be used if algorithms have undergone clinical validation. DICOM recognizes Joint Photographic Experts Group (JPEG) and JPEG2000 for lossy compression of medical images in Supplement 91, Ophthalmic Photography SOP Classes.64,71 Compression types and ratios should be periodically reviewed to ensure appropriate clinical image quality and diagnostic accuracy. Eye care providers overseeing image grading are responsible for diagnostic accuracy.

d. Data Communication and Transmission

A variety of technologies are available for data communication and transfer. Ocular telehealth programs should determine specifications for transmission technologies best suited to their program. Transmission systems should have robust error checking to ensure no loss of clinical information.72 Data communications should be compliant with DICOM standards. Ocular telehealth system equipment manufacturers should supply DICOM conformance statements.

If ocular telehealth applications are integrated with existing health information systems, interoperability should incorporate DICOM conformance, interface with HL7 standards, and establish appropriate routing for patient scheduling and report transmission.73

e. Computer Display

Monitors and settings should be validated for clinical diagnostic accuracy. Any validated monitor technology can be used (e.g., cathode ray tube, liquid crystal display, and gas plasma panel). Retinal images used for diagnosis should be displayed on high-quality monitors of appropriate size and resolution. Displays should be calibrated regularly to ensure fidelity with original validation display conditions. Re-validation should be performed if settings are changed. Ambient light level, reflections and other artifacts should be controlled to ensure standardized viewing.

f. Archiving and Retrieval

Ocular telehealth systems should provide storage capacities in compliance with facility, state, and federal medical record retention regulations. Images may be stored at imaging or reading sites, or offsite, and must satisfy all jurisdiction requirements. Past images and reports should be available.

Each facility should have digital image archiving policies and procedures equivalent to existing policies for protecting other data and hardcopy records. Telehealth programs should also address Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) security requirements for data archive and disaster recovery.

g. Security

Ocular telehealth systems should have network and software security protocols to protect patient confidentiality and identification of image data. Measures should be taken to safeguard and ensure data integrity against intentional or unintentional data corruption. Privacy should be ensured through a minimum 128-bit encryption and two-factor authentication technology. Digital signatures may be used at image acquisition sites. Transmission of retinal imaging studies and study results should conform to HIPAA requirements.

h. Reliability and Redundancy

Written policies and procedures should be in place to ensure continuity of care at levels similar to using hardcopy retinal imaging studies and medical records. Policies and procedures should include internal redundancy systems, backup telecommunications, and a disaster plan. Digital retinal images and reports should be retained as part of patient medical records to meet regulatory, facility, and medical staff clinical needs.

i. Documentation

Readers rendering reports on DR level or other ocular abnormalities should comply with standardized diagnostic and management guidelines as established by the American Academy of Ophthalmology74,75 or the American Optometric Association.76 Reports should be based on HL7 and DICOM standards software forms and meets interoperability standards. Forms should allow ocular findings be recorded to accepted standards of defined DR levels. Medical nomenclature should conform to SNOMED CT® standards. Transmission of reports should conform to HIPAA privacy and security requirements.

j. Image Analysis

Computer algorithms to enhance digital retinal image quality or provide automated identification of retinal pathology are emerging technologies. Image analysis tools for enhancing image quality (i.e., histogram equalization, edge sharpening, and image deconvolution) or identifying lesions such as hemorrhages or hard exudates can be used to aid retinopathy assessment. Image processing algorithms should undergo rigorous clinical validation. Appendix 3 summarizes computer-aided detection of DR research and development.

10. Legal Requirements

Legal and regulatory issues relating to the practice of ocular telehealth are generally the same as other telemedicine modalities and carry the risk management considerations of conventional medical practice.59,77,78 A DR telehealth program should use the same safeguards to mitigate risk.

Some hospital telehealth programs fall within regulatory jurisdictions of the Joint Commission (JC) (formerly Joint Commission for the Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations) and/or Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.66 The JC and Accreditation Association for Ambulatory Health Care (AAAHC) accredit ambulatory healthcare.66 Previous and current JC standards indicate accrediting bodies cover telemedicine activities, making regulatory compliance a mandatory component for most hospital based telehealth programs. There are specific references to telemedicine in JC Environment of Care and Medical Staff sections. CMS and AAAHC requirements occur indirectly through related activities, for example, standards for contract care.

a. Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act

Ocular telehealth programs should obtain professional consultation for HIPAA compliance specific to their program. Telehealth programs should consider HIPAA privacy79 and security80 regulations in clinical, administrative, and technical operation plans. Privacy and security issues are detailed in Appendix 4.

b. Privileging and Credentialing

Telehealth providers may require formal privileging and credentialing. Providers responsible for interpretation of retinal telehealth images should be credentialed and obtain privileges at originating and distant sites if required by applicable statues, regulations, and facility bylaws.81,82 See Appendix 5 for alternatives per JC guidelines.

c. Stark Act and Self-Referrals

Some telemedicine risks are more problematic than others (e.g., anti-trust, fraud and abuse, kickbacks, and self-referrals). Self-referrals occur when physicians refer patients to medical facilities in which they have a financial interest. For example, an ophthalmologist places a retinal imaging workstation in a primary care provider's office at deep discount or gratis and reads images at little or no charge. The anti-kickback Stark statute may have been violated if patients needing laser treatment are referred to the ophthalmologist. This may be prevented by charging the primary care provider full market value for equipment and services and offering the patient a choice of referral ophthalmologists for treatment.

d. State Medical Practice Acts/Licensure

Many telehealth legal issues assume telemedicine is the practice of medicine. These issues are addressed variably by state medical practice acts, but even in the absence of specific statutory or regulatory definitions, telehealth legal claims would be difficult to defend against.59 All states require licensure for rendering medical care to patients located in the state. It could be argued that, with telemedicine, the remote patient visits the physician in the physician's state. However, for practical purposes, a physician is considered subject also to the medical practice laws and regulations where the patient is located.83

Some states are permissive regarding telemedicine service from physicians residing outside the state, whereas other states provide a special telemedicine license. Many states are amending medical practice acts to specifically address telemedicine. More than half require full and unrestricted licensure to render care by telemedicine to a patient residing in the state.

DR telehealth providers should carefully examine telemedicine rules in the states of intended practice. Licensure summaries are provided by the American Medical Association and the Office for the Advancement of Telehealth.83,84 A comprehensive review of licensure is available at the American Telemedicine Association State Telemedicine Policy Center Web site.66

e. Tort Liability

Telehealth providers should consult with their professional liability carrier to ensure coverage in both originating and distant sites. Telemedicine may reduce liability risks through improved access and quality of care. However, telemedicine can also complicate traditional tort liability. Issues include which entity or physician owes a duty to the patient, standards of care, jurisdiction, and choice of law.59 Although telemedicine providers should consult an attorney familiar with telemedicine law, the fundamental aspects of tort law are fairly uniform across jurisdictions:

• A physician has a duty to a patient to act within the accepted standards of care

• Standards of care were violated

• A patient suffered an injury due to the violation of standard of care

f. Duty

A physician's duty arises from the physician–patient relationship.85 Telemedicine alters the traditional context of this relationship, but a telemedicine encounter is sufficient to establish the relationship.86

g. Standards of Care

The telemedicine community is in early stages of establishing standards. The American Medical Association believes medical specialty societies should develop and implement telemedicine practice parameters, defined as educational tools and patient management strategies, to assist physicians' clinical decision making.87 Because telemedicine standards of care are not well established, questions could arise regarding appropriateness of a telemedicine DR evaluation, whether appropriate technology was selected (e.g., Validation Category 1, 2, 3, or 4), or whether the outcome was sufficient. An example of a controversial outcome is failure to diagnose non-DR pathology evident in images (e.g., venous occlusion and choroidal neovascular membrane), or not evident in images (choroidal melanoma anterior to the equator and peripheral retinal tear).

h. Consent

Ocular telehealth is considered part of a treatment or procedure.88 Patients have the right to autonomous, informed participation in healthcare decisions.89 Informed consent is required for clinical treatments and procedures, including those delivered via telemedicine. When treatments or procedures delivered through ocular telehealth are considered low risk and within commonly accepted standards of practice, signature consent may not be required.81 Ocular telehealth services for DR may satisfy these criteria. Patients should be informed that they have a choice of telehealth and nontelehealth ocular treatments or procedures. Practitioners should provide patients information about the ocular telehealth program they would reasonably want to know, including

• Whether the services is novel or experimental

• Differences between care delivered using ocular telehealth and face-to-face

• Benefits and risks of using ocular telehealth in the patient's situation

• Description of what is to be done at the patient's site and the remote site

11. Quality Control

Regardless of an image's origin, providers should ensure the quality of medical images meet specified standards. Policies should be in place to assure patient care and safety,77,90,91 including addressing non-DR eye diseases and findings not specifically related to DM. Telehealth programs should also develop protocols that include policies and procedures for monitoring and evaluating performance.81 Corrective action of undesired trends and continuing education should be included. Evaluation should be tailored to and include all components, such as image acquisition, transmission, and reading. Image acquisition and reading quality assessment and performance improvement are similar to clinical settings. Quality assessment should measure staff performance, data quality, and workflow. Reviews of telehealth program outcomes are fundamental to sustained quality care and ongoing performance improvement. Quality assurance should employ peer-review of outcome and identification of fallout cases to guide corrective interventions.92,93 Training and education standards should be developed. An example of performance categories, training, and quality assurance method is included in Appendix 6.

12. Operations

A DR operations manual contains key instructions and operational information. It can also describe quality assurance and staff training procedures. A comprehensive manual enables normal operations during leadership absence. Manuals should be dynamic documents that grow and evolve ever more tailored to the telehealth program. Appendix 7 describes suggested manual components.

13. Customer Support

DR telehealth programs use advanced technology in a range of settings, operated by diverse staff with varying expertise. Support should be tailored to internal and external customers. Support can be categorized by:

a. Originating Site

• Imager—imaging process, software, recurrent training, recertification

• Imaging device—image acquisition, device faults, preventive maintenance

• Provider/clinical contact—report interpretation, billing

b. Transmission

• Connectivity

• Data loss/recovery

c. Distant Site

• Reader adjudication, recurrent training, recertification

• Diagnostic display equipment and software

Originating and distant sites may be in the same facility with data transmission contained within a single local area network. Support for such systems will be simpler than geographically distributed programs. Technical support can be divided into levels, or tiers, depending on difficulty or urgency. Tiered help desks are common and a convenient way to accommodate program needs. A DR telehealth program should establish standards for addressing customer support needs. Appendix 8 provides examples of levels and support priority.

14. Financial Factors

Telehealth program sustainability depends on a well-developed business plan. Reimbursement, remuneration, and cost are complex issues. Diagnostic and procedural coding, coverage, and reimbursed amounts are important considerations. Because of differences between regions, payers, and clinical settings, each program should tailor billing protocols with Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurance intermediaries.

a. Reimbursement

Billing code and coverage are pivotal components for reimbursement. Both are needed for effective compensation. Before 2011, many DR telehealth programs used the 92250 (Fundus Photography with interpretation and report) Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code. Billing is usually divided into technical or image capture, and professional or interpretation components. Some programs used CPT 92499 (Unlisted Ophthalmic Service or Procedure), which requires negotiated use with the fiscal intermediary or carrier. The Center of Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) approved two new codes specific for remote retinal imaging in the fall of 2010. CPT 92227 and 92228 became effective January 1, 2011. See Appendix 9 for additional information.

b. Grants

Grants have been used to establish telemedicine programs for defined circumstances and duration. Although an important method for proof of concept, grants are usually not viable for sustained clinical operation. DR telehealth programs should have business plans that ensure revenue for sustainability, usually through reimbursement for services via Medicare, Medicaid, or private insurance carriers.

c. Federal Programs

There are several large telemedicine programs that reside within federal agencies and are funded by recurring federal appropriations. Examples include the Indian Health Service and the Veterans Health Administration.

d. Other Financial Factors

Nonrevenue producing benefits of a DR telehealth program may include cost savings and improved operational efficiencies over traditional care delivery; however, benefits may not be realized by the entity creating them. For example, patients and third-party payers may realize financial savings produced by a DR telehealth program operated by a physician, whereas physicians funding the program realize no savings. Under current reimbursement policy, DR telehealth may be a better business model in closed systems, such as managed care, where costs and return on investment are realized by the same entity. Government pay-for-performance incentive programs may change the relationship between program funding and reimbursement in the future. Appendix 9 contains information on logistic efficiencies, disease prevention, and resource utilization.

e. Equipment Cost

With the decreasing cost of computing and telecommunications, a retinal camera may be the largest capital investment for a DR telehealth program. Imaging costs depends on many factors. Devices range from $3,500 to over $65,000, including fundus camera, camera back, lenses, computer, software, and network hardware. Costs can be amortized over several years. Specialty imaging devices are in development with the potential to reduce cost further.

15. Summary

Ocular telemedicine and telehealth have the potential to decrease vision loss from DR. Planning, execution, and follow-up are key factors for success. Telemedicine is complex, requiring the services of expert teams working collaboratively to provide care matching the quality of conventional clinical settings. Improving access and outcomes, however, makes telemedicine a valuable tool for our diabetic patients. Programs that focus on patient needs, consider available resources, define clear goals, promote informed expectations, appropriately train personnel, and adhere to regulatory and statutory requirements have the highest chance of achieving success.

Appendix

1. Appendix 1: Interoperability

Interoperability should reduce errors from duplicate manual data entry and aid clinical decision support systems and alerting. In 2004, President Bush signed an executive order creating the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC). ONC provides leadership for developing nationwide interoperable health information technology infrastructures and processes. The goal is widespread adoption of electronic health records (EHR) by 2014. In 2009, President Obama signed the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA). ARRA includes the Title XIII-Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act. HITECH Act mandates interoperability of EHR systems to allow broad health data exchange for timely and accurate access to patient health information.

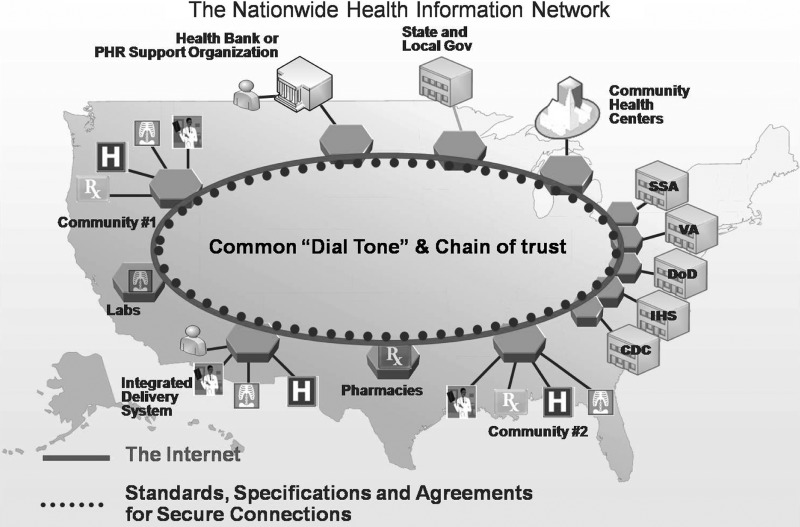

Consequently, there is increasing focus on interoperability and health information exchange at the national level, especially for meaningful use of EHR. To help achieve the goals of the HITECH Act, the Nationwide Health Information Network (NHIN; An initiative for improving the quality and efficiency of healthcare through the secure exchange of health information) and the CONNECT NHIN Health Information Exchange (NHIE) Gateway Community Portal are developing technologies to facilitate data exchange.66 The NHIE Gateway is part of the larger NHIN CONNECT Initiative and will enable federal healthcare agencies and healthcare providers to share patient information efficiently. CONNECT has broad participation including the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), Veterans Administration (VA), Department of Defense (DoD), and the Indian Health Service. CONNECT's first user was the Social Security Administration (SSA). Although CONNECT was developed to create an NHIE, its long-term goal is becoming NHIN's backbone. CONNECT was first released in December 2008. A schematic describing NHIN and CONNECT is illustrated in Figure A1.66

Fig. A1.

Diagram of Nationwide Health Information Network (NHIN) and CONNECT.

Key NHIN development activities are the Data Use and Reciprocal Support Agreement (DURSA) and other legal agreements for data exchange. These documents will describe information shared, accessed, used, disclosed, and privacy and security. The CONNECT NHIN consortium's November 2009 DURSA addressed many aspects of data exchange and use including consent, obligations, permitted use of data, and data ownership.

Key components include the following:

• Extension of Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) to all participants of NHIN

• HIPAA is the floor for all activities on NHIN but local and state laws that go beyond HIPAA are not preempted

• Limited permitted uses of data (e.g., neither use for research or legal/enforcement is allowed)

All participants must respond to a data request from an NHIN member. Sharing data is not required, but the request for data must be acknowledged. Once data are transferred to a recipient, data are owned by the recipient and can be shared/exchanged in conformance to policies.

2. Appendix 2: Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) Metadata

DICOM files contain metadata with information about image data. Parenthetical codes refer to DICOM header metadata.

Demographics

• Patient name (0010, 0010)

• Medical ID number (0010, 0020)

• Patient birth date (0010, 0030)

• Gender (0010, 0040)

• Date and time of examination (0008, 0020) and (0008, 0030)

• Name of facility or institution of acquisition (0008, 0080)

• Accession number (0008, 0050)

• Modality or source equipment that produced the ophthalmic photography series (0008, 0060)

• Referring physician's name (0009, 0090)

• Manufacturer (0008, 0070)

• Manufacturer model name (0008, 1090)

• Software version (0018, 1020)

• Station name (0008, 1010)

Examination information

• Image type or image identification characteristics (0008, 0008)

• Instance number or image identification number (0020, 0013)

• Mydriatic (pupil dilation) or nonmydriatic (no pupil dilation) imaging. Pupil dilated Yes/No (0022, 000D), dilating agent (0022, 001C)

• Size of field or horizontal field of view in degrees (i.e., 20°, 30°, 45°, 50°, 60°, and 200°) (0022, 000B)

• Identification of single retinal field images, simultaneous or nonsimultaneous stereo pairs

• Identification of stereo pairs. Left image sequence (0022, 0021), right image sequence (0122, 0022)

• Monochrome gray scale or color bit depth, ophthalmic photography 8-bit images (0028, 0100, 0028, 0101), 16-bit images (0028, 0102)

• Laterality of eye, right, left, or both eyes; OD, OS, or OU (0020, 0062)

• Retinal region such as Diabetic Retinopathy Study fields 1 to 7 (0008, 0104).

• Ratio and type (i.e., wavelet or Joint Photographic Experts Group [JPEG]) of compression, if used. Lossy compression Yes/No (0028, 2112), lossy compression ratio (0028, 2112), lossy compression method (0028, 2114)

• Detector type, CCD or CMOS (0018, 7004)

• Spatial resolution of the image (i.e., 640×480, 1000×1000, etc.)

• Free text field for retinal imager study comments (i.e., presence of media opacities, poor fixation, poor compliance, etc.)

• Description of any image postprocessing

• Measurement data and/or pixel spacing (0028, 0030)

3. Appendix 3: Computer-Aided Detection

Different computer-based methods to assist detecting retinopathy have been developed. Most efforts rely on traditional image analysis tools such as region growing, edge detection, and segmentation algorithms to identify features such as the optic disc, retinal vascular tree, and vessel crossover. Computers require mathematically exact data definitions to characterize retinal lesions of interest for analysis. Feature extraction is a fundamental step in this process. Algorithms have been developed to segment retinal images,94–101 assess venous beading102–104 and retinal thickness,105–108 quantify lesions103,109–120 and maculopathy,121–123 and detect retinopathy.103,110,124–127 Microaneurysm counting has also shown clinical value as a predictor of retinopathy development. Retinal image analysis to detect and count microaneurysms has relied on morphological, thresholding, and segmentation techniques.94,126,128–134

Lesion detection algorithms generally perform five steps: preprocessing, localization and segmentation of the optic disk, segmentation of the retinal vasculature, localization of the macula and fovea, and localization and segmentation of retinopathy. A variety of outcome measures have been used to validate algorithms.

The use of neural networks to teach systems to recognize patterns has shown initial promise but has yet to achieve consistent sensitivity and specificity to be clinically acceptable.135–137 Results of automated grading to diagnose retinopathy have also been mixed, although some approaches have produced encouraging results.138–141 Risks in adopting computer-aided retinopathy detection include unknown algorithm lesion sensitivity and specificity, the possibility of false negatives, and/or missed referable cases.142

Change analysis assessment is a computer-based approach fundamentally different from feature detection. Instead of identifying specific lesions, change analysis highlights differences between retinal images over time for use in primary and secondary care.143 This approach leaves decision making to the readers and avoids ethical issues of software-based misdiagnosis.141

Content-based image retrieval has recently been applied to computer retinal image analysis.144,145 The concept is based on retrieving related images from a large database of adjudicated retinal images and using pictorial content to provide correct assessment of clinical diagnosis. Resulting content feature lists provide indices for storage, search, and retrieval of related images. The probabilistic nature of content-based image retrieval allows statistically appropriate predictions of presence, severity, and manifestations of common retinal diseases such as diabetic retinopathy (DR). This approach is attractive, but, given the diversity of characteristics and spatial locations of retinal lesions, it may suffer performance issues as image libraries grow. The use of fuzzy logic algorithms is being studied.146

Computer-assisted retinal image analysis is also being applied to abnormal retinal vasculature and vascular changes such as vessel diameter, tortuosity, angle, and retinal vasculature fractal dimension. Retinal image quantitative measures have demonstrated predictive value in DR and cardiovascular disease.147–149

When computer-assisted lesion identification or retinopathy diagnosis decision support is used, the following should be included in the free text field of DICOM headers:

• Algorithm used

• Algorithm functionality

• Algorithm's validated sensitivity and specificity

4. Appendix 4: Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act

Privacy elements include the following:

• Covered entity—any organization, person or business associate thereof that transmits protected health information in electronic or paper form150

• Covered information—individually identifiable health information in any form or medium used or disclosed by a covered entity

• Voluntary consent—covered entities may obtain a patient's consent before using or disclosing his or her health information

Electronic protected health information security includes the following:

• Confidentiality—requires authentication and role-based access to data (must have a need to know)

• Integrity—requires methods for assuring no unauthorized altering or destruction of data

• Availability—requires methods for disaster recovery, backup, and access to data under all conditions

5. Appendix 5: Privileging and Credentialing

Many healthcare facilities use the Joint Commission's (JC) (formerly Joint Commission for the Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations) Elements of Performance for privileging and credentialing providers, even when not strictly required. At one time, Elements of Performance allowed privileging and credentialing telemedicine providers by proxy under specific conditions. This policy allowed the originating site to import privileging and credentialing materials from the distant site if certain criteria were met (i.e., the distant site was JC accredited), staff were privileged for the activity at the distant site, and peer review was conducted and reported to the originating site with other quality information. CMS had planned to require JC to conform to more restrictive criteria effective July 15, 2010, eliminating privileging and credentialing by proxy as described by JC MS.13.01.01. CMS reversed its position in May 2010, however, with a proposed rule defining conditions for a proxy method of privileging and credentialing telemedicine providers.151 As of October 2010, this decision is still under review.

MS.13.01.01, EP 1—Licensed independent practitioners responsible for patient care, treatment, and services via telemedicine are credentialed and privileged at the originating site according to standards MS.06.01.03 through MS.06.01.16. Standards allow medical staff to use information another hospital gathers for physician credentialing provided the other hospital is a Medicare-participating hospital. Data include

• Licensure

• Training

• Board certification verifications

• National Practitioner Data Bank queries

• Sanction queries

• References

• Other information gathered during the credentialing process

6. Appendix 6: Quality Control

The following are major categories of performance to be evaluated; evaluation of all categories below may not be applicable to some programs:

-

• Originating site

-

○ Administrative

▪ Primary care provider and nursing surveys

▪ Patient surveys

▪ DR surveillance rate for catchment area of the program

▪ Successful patient enrollment rate (sustained vs. initial)

▪ Successful referral completion rate

-

○ Imager

-

▪ Ungradeable study rate

• Field definition

• Focus

• Stereo

▪ Imaging time

▪ Continuous Quality Improvement (CQI)

▪ Continuing education (CE)

-

-

○ Equipment

▪ Preventative maintenance schedule

▪ Out of service rate

-

-

• Reading Center

-

○ Administrative

▪ Average acquisition to reading center time

▪ Average time to read standard study

▪ Average time to read stat study

▪ Average acquisition to report delivered time

▪ Exception rate and time

○ Technical—network, servers, software, etc.

-

○ Reader

▪ Average time per read

-

▪ Assessment program of peer review or over-reads at appropriate levels of detail, and including ungradable and exception rates

• Interobserver agreement, if multiple readers are used

• Intraobserver agreement

• External review

• Test set performance

▪ Agreement with live exam, if appropriate

▪ Assessment fallout/outlier review and evaluation

▪ CQI

▪ CE

-

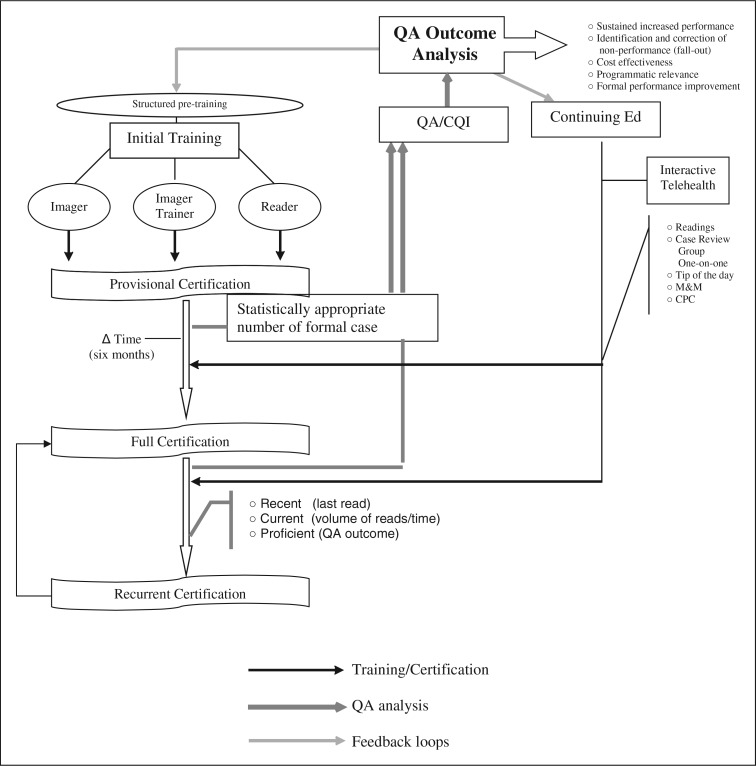

Multiple feedback loops allow CE programs to adapt to changing conditions. Reviews allow CE performance and cost effectiveness to be continuously enhanced (Fig. A2). The following are examples of training and quality assurance method:

Fig. A2.

Example of a quality assurance and Continuous Quality Improvement (CQI) flow diagram.

Standardized training for imager, imager trainers, readers, and reader trainers.152

• Structured, self-study, pretraining of imager and reader to provide minimum background knowledge.

• Structured curriculum training with defined endpoints to assure knowledge and skills proficiency.

• Provisional certification followed by full certification based on experience with a minimum number of patients over a minimum period of time. Experience should demonstrate required levels of proficiency documented by formal quality assurance (QA) review of a fixed number of cases.

• Time-limited certification of imagers and readers. Recertification should be based on the period since last clinical encounter, number of clinical encounters over a period of time, and proficiency as documented by formal QA review. Ocular telehealth programs should create certification methods that are formally defined and relevant to the program.

Ongoing sampling of imager and reader performance by formal criteria based on QA review should be performed. A review of trends in fallout from outcome analyses can be used to assess:

• Proficiency

• Opportunities for program improvement

• Need for changes in initial or recurring training

• Need for additional training of an imager or reader

CE is an important component of any QA/CQI program and a fundamental method of ensuring current competency153. CE should be dynamic and sensitive to patient and staff's changing needs. The following are considerations:

• Adjust CE content by end-to-end program testing through data sampling and outcome analysis

• Adjust CE program to maintain temporal relevance to aggregate and individual clinical populations

• Deliver CE in formats to achieve desired outcome with maximum efficiency and effectiveness. Format examples include periodic self-study curriculum with pre and poststudy testing, newsletters, and e-mail “Tips of the Day.” A variety of interactive CE sessions using telehealth technology are available such as group-based or one-on-one case reviews, morbidity and mortality conferences, and conferences patterned on Clinical Pathological Conference concepts.

Similar guidance comes from broadly distributed programs outside the United States. The U.K. National Screening Committee adopted digital photography in 2000 for a systematic national risk reduction program.154 Their model incorporates trained professionals, recorded outcomes, targets and standards, quality assurance, and promotion to increase screening rates. Criteria and minimal/achievable standards were proposed for each quality assurance objective.155 Other ongoing quality assurance programs are publishing measures and outcomes. For example, a U.K. diabetes center re-graded a percentage of images to determine appropriateness of referrals for clinic examination.156 Other programs have reported outcomes measuring image quality, intragrader reliability, and percentage of grader-generated reports within 48 h of grading images.157

7. Appendix 7: Operational Specifications

Possible components of an ocular telehealth operations manual include

• Company overview & history

• Organization chart

• Mission statement

• Opening procedures

• Closing procedures

• Cash handling

• Daily tasks

• Alarm system operations

• Safe opening and closing procedures

• Contact numbers for emergencies or information

• Employee shift coverage

• Web site procedures

• Customer service procedures

• Marketing

• Sales procedures

• Sales quotas

• Commission payments

• Order processing

• Special orders

• Shipping & receiving

• Equipment handling

• Imaging site deployment

• Reading center operations

• Quality assurance

• Privileging and credentialing (originating and distant site)

• Equipment maintenance (office, clinical, it, etc.)

• Security procedures

• Emergency procedures

• Services pricing and discounts

Additional details and examples that may not be applicable to all programs:

-

• Prospect engagement

○ Sales representative receives prospect information from sales/marketing representative

○ Contacts prospect via telephone, e-mail, letter, etc.

○ Documents contact in CRM software (Customer Relationship Management)

○ Update status of prospect after each contact

○ Prospect closes and becomes client

-

• Contract

○ Send approved contract and lease agreement to prospect

○ Customer returns agreement with signature and deposit check or signature and lease document

○ Submit lease document to leasing company

○ Receive notification of lease approval or equipment paid in full

-

• Setup new customer

○ Complete the Customer Deployment Prerequisite Datasheet

○ Identify static external IP address (may require IT liaison)

○ Identify internal DNS server, Default Gateway, and Subnet Mask

○ Identify user details. Assign new unique clinician identifier for each clinician. Assign a new locally unique user id for that user

○ Identify primary care clinician information. Assign new unique clinician identifier for each clinician

-

• Stage equipment

○ Receive application update CD and shipment checklist and installation checklist from Hosted Solution Management Team

○ Notify admin of expected ship date

○ Admin notifies customer of expected ship date

-

○ Assemble equipment

▪ Camera back

▪ Fundus camera

▪ Table

▪ PC

▪ Desktop reference book

○ Apply the software image to the PC

○ Apply the application update to the PC

○ Run a local photography test using the customer photography instructions

○ Disassemble and repackage for shipment

-

• Customer installation & test

○ Validate training personnel and room availability prerequisites & installation date with customer

○ Validate static IP prerequisites

○ Complete relevant parts of installation checklist Carry out install as per installation document)

○ Schedule/conduct deployment test

○ Complete relevant parts of installation checklist

○ Store in appropriate customer folder

-

• Imager training

○ Ensure that all staff due for training are present

○ Provide introduction to fundus camera—startup, calibration, configuration, imaging, shutdown.

○ Provide introduction to imaging software- logon, configuration, patient registration, image storage and transmission, shutdown, logoff

○ Step through photography process using training scripts, tests and real patients.

○ Obtain sign-off from all trained staff. Complete relevant parts of installation checklist and store in appropriate customer folder

-

• Photography

-

○ Administrator

▪ Diabetic patient presents at front desk

▪ Verify that the patient has not had retinal photographs within 12 months by checking records

▪ Add retinal photography to their routing slip for the day

-

○ Photographer

▪ Diabetic patient presents for photography

▪ Drop the patient in to today's clinic according to the instructions

-

○ Monitor messaging

▪ Run the “Daily Report” for all locations

▪ Inspect the report to validate it conforms to the business rules (see exceptions)

-

○ Monitor message resend

▪ Examine message queue for timed-out message send

▪ Resend any outstanding messages, log the ids of the messages that have required a resend

-

○ Reader

▪ Grade according to the protocol

-

○ Monitor grading throughput

▪ Run the “Remote Grading Report” for all locations

▪ Inspect for outstanding grading

▪ Inspect for disagreements

-

○ Quality control grading

▪ Log on to the application

▪ Check the Secondary grading queue for available grading, click the “Grade” button to start grading

▪ Conduct secondary Grading according to the protocol

-

○ Monitor service status

▪ Verify service status

▪ Verify bandwidth usage

▪ Verify nightly logs

▪ Verify/action outstanding ticket log

-

○ Monitor nightly backups

▪ Open backup log – verify that there were no errors, and that backup files exist

-

8. Appendix 8: Customer Support

Some programs may find it appropriate to consolidate the following example of an ocular telehealth program three-level help desk.

Level 1

This is the entry point for most/all initial support requests. Support staff can satisfy image acquisition issues and entry level troubleshooting of software and data transmission. If the request for support is determined to be outside Level 1 scope, the call is triaged to the Level 2 or Level 3 Help Desk.

Level 2

For more complex software and data transmission issues a second level support is needed to provide solutions that are more technical in nature.

Level 3

A third level support is needed for troubleshooting and resolving proprietary technology. Typically, this concerns the imaging device and associated equipment, for example, camera backs, relay lenses, and software applications.

Configuration may be arranged as to priority:

| IMPACT LEVEL | DEFINITION | TARGET CALL BACK TIME | TARGET RESOLUTION TIME |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

Critical: Critical System Software is entirely unavailable or severely degraded to the point of un-usability and there is no workaround/alternative |

15 min | 4 h |

| 2 |

Major: Noncritical System Software is entirely unavailable or; Critical System Software is entirely unavailable or severely degraded to the point of un-usability and there is a workaround/alternative |

1 h | 8 h |

| 3 |

Minor: Part of a System is unavailable |

Not applicable | 14 working days |

| 4 |

Nonurgent user interface issues: System has failed to meet its specification or; Request for information about how to use the System |

Not applicable | 21 working days |

| 5 |

Good Will: Anything else, e.g. State changes Letter changes Patient merges Resetting grading Correcting observations |

Not applicable | approximately 180 days |

9. Appendix 9: Reimbursement

Medicare

Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) 92227: remote imaging for detection of retinal disease (e.g., retinopathy in a patient with diabetes) with analysis and report under physician supervision, unilateral, or bilateral.

CPT 92228: remote imaging for monitoring and management of active retinal disease (e.g., DR) with physician review, interpretation and report, unilateral, or bilateral.