Abstract

Elucidation of the role played by cells of the innate immune system, particularly the dendritic cell (DC) populations, has led to a precipitous growth in our understanding of immunity to pathogens and foreign antigens. Much of this information has been derived from studies using mouse model systems. However, mice and human DCs differ drastically in the relative distribution of the toll-like receptors (TLRs) critical for immune activation. This is particularly true for the plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs), which are activated almost exclusively through TLR signaling. Variation in this DC subpopulation has been implicated in a number of pathological syndromes; therefore, a thorough understanding of their steady state and activation profiles in human patients is essential. A number of factors, including the relatively low numbers of these cells in blood, have precluded careful analysis in clinical trials. To overcome these limitations, we have developed a technique for studying the steady state and activation profile of pDCs collected from small amounts of human blood. This technique can be performed with 10,000 cells to obtain the immune transcriptome of the pDCs analyzed by quantitative PCR using amplified RNA. In addition, we have used multiplex enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays to measure secreted proteins. We demonstrate the validity of this technique and document its potential for use with blood from human study populations.

Introduction

During the past decade, great progress has been made in understanding how the immune system identifies microbial invaders and initiates an immune response appropriate to the pathogen. Much of the progress has resulted from a renewed appreciation for the role played by the innate immune response. Innate immunity is responsible for two major functions: it represents a major barrier to prevent the establishment of infection and if breached, signals and directs the activation of adaptive immune cells. Dendritic cell (DC) populations are integrally involved in both functions (Banchereau and others 2000). There are two major subtypes of DCs, conventional DCs (cDCs) and plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs). The two DC subtypes have different functional, physical, and material properties. cDCs function as professional antigen-presenting cells (APCs) that prime naïve T cells efficiently after undergoing a maturational change triggered by diverse microbial stimuli (Banchereau and Steinman 1998). In contrast, pDCs are the principal type I interferon (IFN) producing cells of the immune system and their function as APC has not yet been demonstrated conclusively. Two families of pattern recognition receptors have been identified on DC subpopulations and have been shown to be involved in sensing the presence of a virus infection: toll-like receptors (TLRs) and RIG-I-like receptors (RLRs) (Lee and Kim 2007). Using mouse models for virus infection, much has been learned about the role of these families of receptors in the activation of innate and adaptive immunity. However, there are major differences between mouse and human DC populations with regard to the distribution of the TLRs responsive to viruses found on the respective DC subpopulations. In humans, pDCs express TLR7, 8, and 9 while cDCs express TLR3 (Kawai and Akira 2006). In contrast, mice express the receptors more promiscuously on both cell types. Therefore, in light of the importance of these cells in virtually all immune responses whether beneficial or detrimental, studies of these two cell populations in human cells must be undertaken. cDCs are easily isolated in reasonable numbers from human blood samples as monocyte precursors that can be efficiently converted to cDCs by growth in granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and interleukin-4 (IL-4). However, human pDCs have been much more difficult to study because of their scarcity in blood, reduced viability after collection, and the small cell size. Although it is complicated to obtain enough cells from buffy coats or leukophoresis to study their characteristics, it is currently almost impossible to comprehensively evaluate pDCs in a clinical patient–based study. Since aberrant levels of pDCs have been implicated in clinical syndromes associated with coronary heart disease, asthma, autoimmune psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis, and lupus erythematosus, it is essential to develop techniques that overcome these limitations.

Previously, we have successfully studied the activation of human cDCs by viral stimuli and the impact of the IFN antagonist from influenza virus using quantitative PCR (qPCR) and multiplex enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) technologies (Colonna and others 2004). However, to overcome the difficulties associated with the study of pDCs, we have now established a novel approach to analyze their steady state and activation profiles by analyzing mRNA expression levels using qPCR of amplified RNA and the release of cytokines and chemokines using multiplex ELISA technology. These techniques can be used in the study of pDCs without constraint and allow for broader testing and/or studies in patient population that were restricted previously.

Materials and Methods

Isolation and culture of human DC

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated by Ficoll density gradient centrifugation (Histopaque; Sigma-Aldrich) from either buffy coats or 50 mL of whole blood from healthy human donors (Mount Sinai Blood Donor Center, New York Blood Center and Mount Sinai Hospital, NY). Whole blood donation samples were obtained following protocol approved by Mount Sinai Medical Center Institutional Review Board. CD14+ cells were immunomagnetically purified using antihuman CD14 antibody-labeled magnetic beads and BDCA4+ cells were immunomagnetically purified using antihuman BDCA4 (CD304)+ antibody-labeled magnetic beads and iron-based Midimacs LS columns (Miltenyi Biotec). After elution from the columns, CD14+ cells were plated (0.7 × 106 cells/mL) in DC medium (RPMI [Invitrogen], 10% fetal calf serum [HyClone] or 4% human serum [Cambrex], 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin [Invitrogen]) supplemented with 500 U/mL human GM-CSF (Peprotech) and 1000 U/mL human IL-4 (Peprotech), and incubated for 5–6 days at 37°C. BDCA4 (CD304)+ cells were treated immediately following elution.

Flow cytometry

BDCA4+ cells were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate–linked CD123 and phycoerythrin-linked BDCA2 (CD303), according to the manufacturer's instructions (Miltenyi Biotec), and the expression of each marker was determined by flow cytometry using an FC500 flow cytometer from Beckman Coulter. Data were analyzed using Flowjo software. The average purity of BDCA4+ cells from buffy coats was 91.00 ± 5.11%, defined as a double positive for CD123 and BDCA2 (CD303).

Infection and treatment of DCs

Immediately after the isolation of BDCA4+ cells, DCs were left either untreated, infected with influenza PR8 virus or Newcastle Disease Virus (NDV) at a multiplicity of infection 0.5, or treated with 500 ng/mL lipopolysaccharide (LPS; Sigma-Aldrich) or 6 μg/mL CpG (Coley Pharmaceutical Group). Cells were treated in DC medium at 1 × 106 cells/mL for different time periods, depending on the experiment.

Luminex ELISAs

Capture ELISAs for IFN-α, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), IL-6, IL-8, RANTES, and MIP1-β (Upstate) were performed as part of a multiplex assay following the manufacturer's protocol. Plates were read in a Luminex plate reader and data were analyzed using software from Applied Cytometry Systems.

RNA extraction and generation of cDNAs from human DCs

DC samples treated according to the experimental protocol were pelleted, and RNAs were isolated and treated with DNase by using an Absolutely RNA RT-PCR micro prep kit (Stratagene). RNAs were quantified using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (Nanodrop Technologies).

Amplification

An aliquot of 50 ng total RNA was amplified using the WT-Ovation™ RNA Amplification System (NuGEN, San Carlos, CA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. DNA Clean and Concentrator-25 kit (Zymo Research, Orange, CA) was used for cDNA purification. Amplification generated between 5 and 10 μg of cDNA.

PCR

Platinum Taq DNA Polymerase and SYBR Green from Invitrogen were used for real-time PCR. An aliquot of 2 ng amplified DNA and cDNA generated from 5 ng total RNA was used for each reaction in an ABI Prism 7900 HT (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) in 20 mM Tris, pH 8.4, 50 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 200 μΜ dNTPs, 0.5X SYBR Green I (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), 200 nM each primer, and 0.5 U Platinum Taq (Invitrogen). Reaction specificity was confirmed by melting curve analysis. The primer sequences used in this study are presented in supplementary Table 1 (supplementary table is available online at http://www.liebertpub.com/jir).

Data analysis

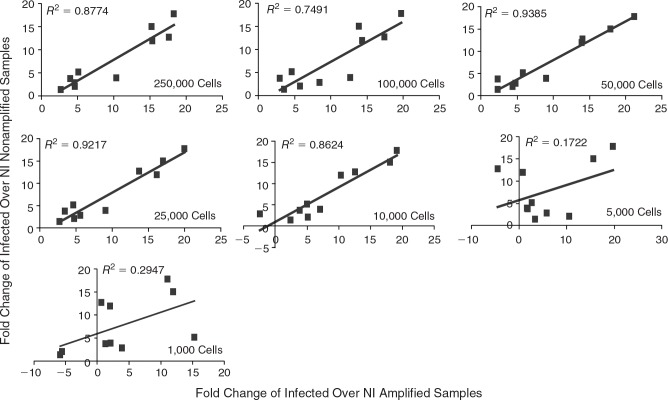

A linear regression was conducted for each comparison in Figs 2 and 3. In each linear regression, the qRT-PCR measurement (fold change or normalized ΔCt) from nonamplified RNA of the 250,000 pDCs is the predictor variable x, and the response variable y is from amplified RNA for the indicated number of pDCs. The R2 in each linear regression (the square of the Pearson's correlation coefficient, r) explains the proportion of variance in the response variable y, which can be explained by using the predictor variable x. Applying a Fisher's z-transformation to the correlation coefficient, z = 1/2log(1 + r)/(1 − r), a threshold of R2 can be computed to establish a correlation coefficient r between the amplified RNA and nonamplified RNA experiments that is not statistically significantly smaller than between two non-amplified RNA experiments. This threshold was applied to each linear regression to indicate whether an amplified RNA experiment has statistically significant difference. All of the statistical computations were performed using the statistical programming language R.

FIG. 2.

RNA isolation and amplification method does not alter gene profile down to 5000 pDCs. The expression of 10 genes related to pDCs maturation was compared from amplified RNA from the indicated number of pDCs to the RNA from 250,000 pDCs nonamplified. Data are expressed as normalized fold change of ct values from infected cells over NI cells. pDCs were infected with NDV (moi = 0.5) or left untreated for 8 h. After infection, cells were separated into samples containing 1000–250,000 cells for RNA isolation and qRT-PCR. See data analysis section for a detailed description. R2 > 0.91 indicates that there is no statistically significant difference.

FIG. 3.

Individual infections and amplification does not alter gene profile down to 10,000 pDCs. The expression of 10 genes related to pDCs maturation is compared from amplified RNA from the indicated number of pDCs to 250,000 pDCs nonamplified. Data are expressed as normalized fold change of ct values from infected cells over NI cells. Between 1000 and 250,000 pDCs were infected with NDV (moi = 0.5) or left untreated for 8 h, before RNA isolation and qRT-PCR. See Data analysis section for a detailed description. R2 > 0.47 indicates that there is no statistically significant difference.

Results

Difficulty in obtaining sufficient numbers of pDCs to study using conventional techniques

Originally, activation of DCs was characterized by changes in surface molecules (CD80, CD86, MHC class II) and the release of cytokines such as IL-12, IL-6, and TNF-α. A number of laboratories including ours developed extensive qRT-PCR and multiplex ELISAs to more comprehensively analyze changes induced by microbes during DC activation (Fernandez-Sesma and others 2006). These innovations led to the realization that DC activation was not an all or nothing response but actually showed pathogen-specific responses. It also allowed investigations into the manipulations of the activation process by microbial immune antagonists. We have used these techniques to investigate the activation of cDCs and pDCs. The work with pDCs has been difficult even when using buffy coats from blood banks containing approximately 500 mL of donation. pDCs and cDCs differ in their size, shape, and the percentage of each found in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). cDCs are typically cultured from CD14+ cells which comprise approximately 15% of PBMCs (Syme and others 2002; Yang and others 2002). In contrast, pDCs are directly isolated from blood and consist of less than 1% of the circulating PBMCs in healthy individuals (Narbutt and others 2006). They are also much smaller than cDCs (10 μm vs. 20 μm), which reduces the per cell RNA yield (Greenberg and others 2005; Hoene and others 2006). To examine the difference in RNA yields from the two DC subsets, RNA was isolated and quantified. Decreasing amounts of cells were used for isolation to determine the lower limits of DC numbers for use with the RNA isolation protocol. At the highest quantity of cells, over four times the amount of RNA was isolated from cDCs as from pDCs (Fig. 1). Using 50,000 pDCs, the amount of RNA obtained was at the lowest detection levels for quantification using standard PCR. pDCs contained significantly less RNA than cDCs at all amounts tested (Fig. 1). Thus, it is very difficult to envisage large-scale patient studies of pDCs by using the current technology.

FIG. 1.

Differences in RNA yield between cDCs and pDCs. cDCs and pDCs of indicated numbers were lysed and total RNA was isolated. Quantification was performed using Nanodrop spectrophotometer. Each group represents between 5 and 130 individual isolations. *p < 0.05, **p < 3 × 10−5, as determined using a two-tailed student's t-test.

Determination of the lower limit of cell numbers for use in RNA amplification

To overcome the limitations imposed by the scarcity and low RNA yield from the pDCs, we attempted to develop an assay that would allow us to look at pDC activation using small numbers of cells. The readout for activation is gene transcription using samples following RNA amplification. pDCs were analyzed following activation with the avian parainfluenza virus, Newcastle disease virus (NDV). To ensure that amplification was not biasing mRNA transcription patterns, the transcription profile of mRNA collected from amplified NDV-infected pDCs was compared with the profile of nonamplified NDV-infected pDCs. To determine the lower capabilities of amplification, RNA was isolated from between 1000 and 250,000 pDCs and compared with the expression pattern of RNA collected from 250,000 pDCs without amplification. Cells were infected together in a single tube to eliminate any experimental differences, the cells were then separated after infection and the RNA was isolated from the indicated number of cells. In determining the mRNA expression profiles, the cycle threshold (ct) values for each gene were normalized to the ct values of three housekeeping genes, β-actin, α-tubulin, and ribosomal protein S11. These normalized expression values were then used to determine the fold change of infected samples over noninfected (NI). Determining fold change over NI samples is critical for establishing which treatments are altering the activation state of pDCs. Figure 2 depicts the comparison between the fold changes of amplified to nonamplified pDCs for 10 representative genes (NDV NP, NDV HN, IFN-α, IFN-β, MIP1β, RIG-I, MXA, IP-10, TNF-α, IL-6). No significant differences were seen in the mRNA profiles of cells amplified compared with cells nonamplified if 5000 or more cells were used. If 1000 cells were used excessive variability based on the R2 value (R2 = 0.78) was observed (Fig. 2). In conclusion, RNA amplification does not bias the transcriptional readout of pDC activation when at least 5000 cells are used.

Determination of the effect of low cell numbers on infection

The RNA amplification protocol was not biasing the pDC expression profiles when cells were infected together. However, in experiments using patient samples it might be necessary to infect small cell numbers before the collection and amplification of the RNA. Therefore, we measure the impact of separating the cells into tubes containing between 1000 and 250,000 cells before infection. In scaling down the number of cells in an infection, there are two possible sources for variation, the physical limitations of manipulating small volumes and cell numbers and the experimental differences of each infection. To determine the lower limit of the method, between 1000 and 250,000 pDCs were infected individually, mRNA isolated and amplified and the profiles were compared to the profile from mRNA collected from 250,000 pDCs without amplification. Fold changes were determined for the 10 representative genes (Fig. 3). No significant differences were seen in the mRNA profiles of amplified compared to nonamplified pDCs until 5000 cells (Fig. 3). Overall, a reliable mRNA expression profile can be achieved when 10,000 pDCs are used.

Stimuli-specific RNA expression patterns from small numbers of pDCs

Amplification of RNA allows for studying smaller amounts of pDCs, permitting a decrease in the amount of blood needed for isolation or an increase in the number of treatments in an experiment. To demonstrate the validity of the method, pDCs were isolated from the blood of a healthy human donor and five separate treatments, each done in triplicate, for a total of 15 individual samples were examined. Each sample contained only 25,000 pDCs. The pDCs were left untreated, treated with CpG or LPS to activate through TLRs, or infected with NDV or influenza virus (PR8) that can activate through TLRs and/or RLRs. All treatments were stopped after 6 h. RNA was isolated and amplification was use to determine log2 fold change in gene expression over NI samples. Figure 4 shows the results from a panel of genes.

FIG. 4.

mRNA expression profiles from various stimuli established for limited numbers of pDCs. In triplicate, 25,000 pDCs were treated for 6 h with media, LPS, CpG, NDV, or PR8. RNA was isolated from each sample for RNA amplification followed by qRT-PCR. Data are expressed as log2 normalized fold change of ct values from infected cells over NI cells with mean of triplicate indicated and standard error bars.

Differences in protein secretion patterns from small numbers of cells treated with various stimuli

In addition to the reproducible mRNA expression profiling, this method can be used to generate a broad profile of secreted proteins using the Luminex multiplex system. From the same samples used for mRNA expression profiling (25,000 pDCs), supernatants were collected following 6 h of treatment. Figure 5 depicts the concentration of several cytokines and chemokines from each of the treatments, with the average and standard error of the triplicates represented. Clearly, this technology allows not only for detailed analysis of mRNA expression but also thorough investigation of protein secretion patterns.

FIG. 5.

Secreted protein profiles determined from different stimuli from limited numbers of pDCs. In triplicate, 25,000 pDCs were treated for 6 h with media, LPS, CpG, NDV, or PR8. Supernatants were harvested and analyzed using Luminex multiplex system. Data are the mean of triplicate samples from duplicate wells with standard error bars expressed in nanograms/milliliter.

pDCs collected from single patients are sufficient for detailed experimentation

To demonstrate that these experiments are feasible from patient populations, we provide the average yield of PBMC and pDCs from 39 patients when only 50 mL of blood was collected for study. The average recovery of pDCs was 4.9 × 105 with a purity of 89%. On average, enough pDCs are isolated from 50 mL of blood for over 19 treatments of 25,000 cells (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient Results from Small Volume Blood Donations

| Blood volume (mL) | No. of PBMCs × 106 | No. of pDCs × 106 | Purity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average n = 39 | 50.53 | 117.57 | 0.49 | 89.58 |

| Standard deviation | 3.79 | 34.88 | 0.19 | 3.22 |

Summary of pDC isolations from approximately 50 mL of blood from a healthy human donor.

Discussion

Research on pDCs has been dramatically hindered due to the small percentage of pDCs found in blood. Further limiting experimentation, pDCs yield a small amount of RNA as compared with cDCs (Fig. 1). Elevated or reduced levels of pDCs have been implicated as a possible contributing factor in coronary heart disease (Shi and others 2007), asthma (Matsuda and others 2002), psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis (Jongbloed and others 2006), and lupus erythematosus (Ronnblom and others 2003; Barrat and others 2005; Means and others 2005). With regard to the autoimmune manifestations, it is believed that aberrant activation of pDCs may lead to excessive type I IFN release that can have major ramifications on immunity. In lupus, this activation is believed to be triggered by immune complexes of self-reactive antibodies and self nucleic acids and depend on TLR signaling (Ronnblom and others 2003; Barrat and others 2005; Means and others 2005). A recent and extremely important study has shown that pDC activation by a complex of the human cathelicidin LL37 with self DNA through TLR9 and may be an important factor in psoriasis through excessive IFN production (Lande and others 2007). Therefore, it is crucial that we develop reliable techniques that allow evaluation of pDC steady state and activation from individual patients. Standard methods, such as those using very sensitive qPCR, demand a minimum of 250,000 cells per determination. Since the average yield of pDCs from 50 mL of blood is 500,000 cells, it is difficult to do any sophisticated analysis on samples in a typical clinical study. The amplification method provides a reliable protocol for use, having established that neither the procedure nor the manipulation of small numbers of cells alters the expression profiles in pDCs (Figs 2–4).

With this new method, pDC experimentation can now occur in novel areas overcoming the limitations imposed by the small volumes of blood that can be obtained from many patient populations. This method can now be used for studying pDCs in children, pregnant woman, the elderly, or any persons with disease limiting their ability to provide enough blood. In addition, using this technology it is now possible to run detailed time courses, dose responses, and multiple treatments while allowing the use of the replicates needed to gain statistical significance. By defining the limits of this method with pDCs, the same technology can be applied to other cells found at limited numbers in blood.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the NIH/NIAID award No. U19 AI062623 and award No. HHSN266200500021C and from the NIAID award No. R01 AI41111.

References

- Banchereau J, Steinman RM. 1998. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature 392(6673):245–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banchereau J, Briere F, Caux C, Davoust J, Lebecque S, Liu YJ, Pulendran B, Palucka K. 2000. Immunobiology of dendritic cells. Annu Rev Immunol 18:767–811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrat FJ, Meeker T, Gregorio J, Chan JH, Uematsu S, Akira S, Chang B, Duramad O, Coffman RL. 2005. Nucleic acids of mammalian origin can act as endogenous ligands for toll-like receptors and may promote systemic lupus erythematosus. J Exp Med 202(8):1131–1139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colonna M, Trinchieri G, Liu YJ. 2004. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells in immunity. Nat Immunol 5(12):1219–1226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Sesma A, Marukian S, Ebersole BJ, Kaminski D, Park MS, Yuen T, Sealfon SC, Garcia-Sastre A, Moran TM. 2006. Influenza virus evades innate and adaptive immunity via the NS1 protein. J Virol 80(13):6295–6304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg SA, Pinkus JL, Pinkus GS, Burleson T, Sanoudou D, Tawil R, Barohn RJ, Saperstein DS, Briemberg HR, Ericsson M and others. 2005. Interferon-alpha/beta-mediated innate immune mechanisms in dermatomyositis. Ann Neurol 57(5):664–678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoene V, Peiser M, Wanner R. 2006. Human monocyte-derived dendritic cells express TLR9 and react directly to the CpG-A oligonucleotide D19. J Leukoc Biol 80(6):1328–1336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jongbloed SL, Lebre MC, Fraser AR, Gracie JA, Sturrock RD, Tak PP, McInnes IB. 2006. Enumeration and phenotypical analysis of distinct dendritic cell subsets in psoriatic arthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 8(1):R15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai T, Akira S. 2006. Innate immune recognition of viral infection. Nat Immunol 7(2):131–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lande R, Gregorio J, Facchinetti V, Chatterjee B, Wang YH, Homey B, Cao W, Wang YH, Su B, Nestle FO. and others. 2007. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells sense self-DNA coupled with antimicrobial peptide. Nature 449(7162):564–569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MS, Kim YJ. 2007. Pattern-recognition receptor signaling initiated from extracellular, membrane, and cytoplasmic space. Mol Cells 23(1):1–10 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda H, Suda T, Hashizume H, Yokomura K, Asada K, Suzuki K, Chida K, Nakamura H. 2002. Alteration of balance between myeloid dendritic cells and plasmacytoid dendritic cells in peripheral blood of patients with asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 166(8):1050–1054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Means TK, Latz E, Hayashi F, Murali MR, Golenbock DT, Luster AD. 2005. Human lupus autoantibody-DNA complexes activate DCs through cooperation of CD32 and TLR9. J Clin Invest 115(2):407–417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narbutt J, Lesiak A, Sysa-Jedrzejowska A, Smolewski P, Robak T, Zalewska A. 2006. The number and distribution of blood dendritic cells in the epidermis and dermis of healthy human subjects. Folia Histochem Cytobiol 44(1):61–63 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronnblom L, Eloranta ML, Alm GV. 2003. Role of natural interferon-alpha producing cells (plasmacytoid dendritic cells) in autoimmunity. Autoimmunity 36(8):463–472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi H, Ge J, Fang W, Yao K, Sun A, Huang R, Jia Q, Wang K, Zou Y, Cao X. 2007. Peripheral-blood dendritic cells in men with coronary heart disease. Am J Cardiol 100(4):593–597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syme R, Callaghan D, Duggan P, Bitner S, Kelly M, Wolff J, Stewart D, Gluck S. 2002. Storage of blood for in vitro generation of dendritic cells. Cytotherapy 4(3):271–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Scott PG, Giuffre J, Shankowsky HA, Ghahary A, Tredget EE. 2002. Peripheral blood fibrocytes from burn patients: identification and quantification of fibrocytes in adherent cells cultured from peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Lab Invest 82(9):1183–1192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]