Abstract

Recent discoveries of the molecular identity of mitochondrial Ca2+ influx/efflux mechanisms have placed mitochondrial Ca2+ transport at center stage in views of cellular regulation in various cell-types/tissues. Indeed, mitochondria in cardiac muscles also possess the molecular components for efficient uptake and extraction of Ca2+. Over the last several years, multiple groups have taken advantage of newly available molecular information about these proteins and applied genetic tools to delineate the precise mechanisms for mitochondrial Ca2+ handling in cardiomyocytes and its contribution to excitation-contraction/metabolism coupling in the heart. Though mitochondrial Ca2+ has been proposed as one of the most crucial secondary messengers in controlling a cardiomyocyte’s life and death, the detailed mechanisms of how mitochondrial Ca2+ regulates physiological mitochondrial and cellular functions in cardiac muscles, and how disorders of this mechanism lead to cardiac diseases remain unclear. In this review, we summarize the current controversies and discrepancies regarding cardiac mitochondrial Ca2+ signaling that remain in the field to provide a platform for future discussions and experiments to help close this gap.

1. Introduction

Over the past ten years, we have witnessed a monumental shift in our understanding of the roles of calcium-ion (Ca2+) handling by mitochondria under both physiological and pathophysiological conditions in mammalian cells (see reviews [1–5]). Though mitochondria were originally discovered as the cellular “powerhouses” responsible for generating adenosine triphosphate (ATP) in the beginning of the 20th century, the organelle’s capacity to accumulate Ca2+ has also been documented since the 1960s [6, 7]. While the physiological and pathophysiological significance of this pathway has been long-debated, recent discoveries (within the past 10 years) regarding the molecular identity of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake/release mechanisms have finally placed mitochondrial Ca2+ transport at center stage of cellular Ca2+ homeostasis [1–5].

It is now clear that mitochondrial Ca2+ handling machinery is ubiquitous in every cell system, including cardiac muscles (i.e., cardiomyocytes), though each cell-type may exhibit variations in the spatiotemporal tuning and kinetics of its mitochondrial Ca2+ handling systems [8]. These variations are possibly due to differences in the stoichiometry and set-up of mitochondrial Ca2+ channels/transporters, the types of Ca2+ releasing sites at the endoplasmic and sarcoplasmic reticulum (ER/SR) (i.e., inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate [IP3] receptors vs. ryanodine receptors [RyRs]), and the frequency and gain of cytosolic Ca2+ oscillations. Indeed, over past several years, multiple groups have taken advantage of newly available molecular information, applying genetic tools in situ and in vivo to delineate the precise mechanisms for the regulation of mitochondrial Ca2+ handling in cardiomyocytes and the heart [9–17]. For instance, rapid progress was made in characterizing the role of the mitochondrial Ca2+-uniporter (MCU) complex at the inner mitochondrial membrane in cardiomyocytes by genetically knocking out each component of the MCU complex both in situ and in vivo [9–14]. Given the centrality of Ca2+ signaling in cardiac excitation-contraction coupling and the spatial occupation of mitochondria within cardiac muscles (>30%) [18], it seems inevitable that mitochondrial Ca2+ handling contributes to the kinetics of cytosolic Ca2+ cycling and enhancing the rate of ATP synthesis. Though the alteration of mitochondrial Ca2+ is frequently observed in cardiac diseases that involve disrupted energy metabolism, the detailed mechanisms of how mitochondrial Ca2+ regulates physiological mitochondrial and cellular functions in cardiac muscles, and how disorders of this mechanism lead to cardiac diseases remain unclear. This review provides an overview of existing controversies related to mitochondrial Ca2+ handling, with a focus on the difference between non-cardiac cells and cardiac muscles. Specifically, this review examines the reports that have come out after the discovery of the molecular identities of major mitochondrial Ca2+ influx (i.e., components of MCU complex) and efflux (i.e., mitochondrial Na+/Ca2+ exchanger: NCLX) mechanisms and attempts to contextualize them within our understanding of the roles of mitochondrial Ca2+ in cardiac Ca2+ signaling as well as in the pathophysiology underlying a range of major cardiac diseases. We will also summarize the current controversies and discrepancies regarding cardiac mitochondrial Ca2+ signaling that remain in the field to provide a platform for future discussions and experiments to help close this gap.

2. Overview of Mitochondrial Ca2+ Handling in Cardiac Excitation–Contraction/ Metabolism Coupling

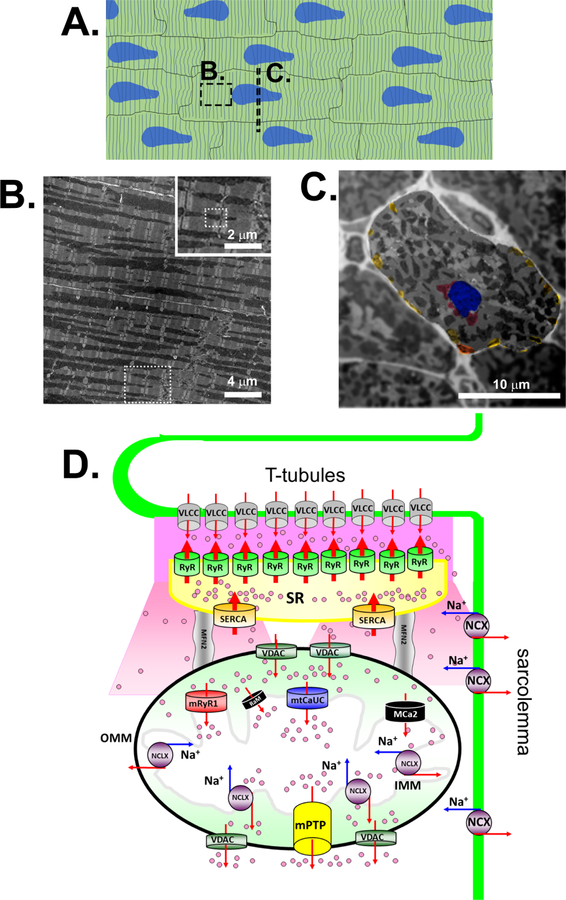

Ca2+ plays a central role in excitation-contraction coupling of cardiac muscles (see review [19]). Ca2+ influx from the extracellular space to the cytosol via the voltage-gated L-type Ca2+ channel triggers the opening of RyR type 2 (RyR2) at the SR facing the transverse tubules (T-tubules), which promotes Ca2+ release from the SR (i.e., Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release) (Fig. 1A, B, and D). This transient rise of cytosolic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]c), termed the “Ca2+ transient” (Fig. 2, upper panel), triggers cardiac contraction as Ca2+ binds to troponin C. Elevated [Ca2+]c is then removed by the SR Ca2+ pump (SR Ca2+-ATPase [SERCA]) and taken back up into the SR lumen or extruded from the cell by the plasma membrane (i.e., sarcolemma)-localized Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX) (Fig.1D). When the amplitude and/or frequency of the Ca2+ transient becomes larger, cardiac work increases independent of the Frank-Starling mechanism [20]. Therefore, increased Ca2+ cycling is correlated with increased ATP consumption. Accumulating evidence indicates that cardiac mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake during excitation-contraction coupling in response to Ca2+ transient and increased Ca2+ concentration at the mitochondrial matrix ([Ca2+]m) may serve as a regulatory signal to ensure the balance of energy supply and demand [21] (i.e. excitation–metabolism coupling) (see section 6). However, the kinetics of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake/release (see section 5), the significance of mitochondrial Ca2+ buffering capacity (see section 5), and the detailed molecular mechanisms for [Ca2+]m-mediated ATP and (see section 6) reactive oxygen species (ROS) production (see section 7) are still a matter of debate. Adult ventricular myocytes have highly organized and static mitochondria, that can be categorized into three distinct subpopulations depending on their subcellular location [22] (Fig. 1A-C); 1) interfibrillar mitochondria, the main subpopulation among three, which are aligned adjacent to myofibrils, with one or two mitochondria lying along each sarcomere (Fig. 1B); 2) subsarcolemmal mitochondria, which line up just beneath the sarcolemma (Fig. 1C); and 3) perinuclear mitochondria which form clusters around the nucleus (Fig. 1C). Specifically, using the isolated mitochondria from heart tissues, it has been well described that interfibrillar and subsarcolemmal mitochondria have significant differences in their 1) protein and lipid compositions, 2) respiration, 3) Ca2+ capacity, and 4) sensitivity to stress [23, 24]. For instance, there is no difference in the mitochondrial Ca2+ content between isolated interfibrillar and subsarcolemmal mitochondria, but the maximum Ca2+ capacity is higher in interfibrillar mitochondria compared to that in subsarcolemmal mitochondria [25]. However, the molecular mechanism of this heterogeneity of Ca2+ handling in these two different mitochondrial subpopulations is still unclear. Currently, there is no report regarding the mitochondrial Ca2+ handling of isolated perinuclear mitochondria from adult hearts, possibly due to the difficulty of isolation of these mitochondria by different centrifugations. However, recent observations using three-dimensional electron microscopy showed that all mitochondria are interconnected in cardiomyocytes [26]. Thus, further studies are required to test whether these functional differences observed in the different subpopulations of isolated mitochondria also exist in the intact cardiomyocytes. Importantly, Morad’s group applied confocal microscopy to live intact adult ventricular myocytes and showed that caffeine puff-induced rapid increase in [Ca2+]c promotes mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake by the interfibrillar mitochondria, but perinuclear mitochondria oppositely release Ca2+ possibly via NCLX [27, 28]. Moreover, they also found the heterogeneous Ca2+ uptake profile in single subsarcolemmal mitochondrion in response to [Ca2+]c elevation using total internal refraction (TIRF) microscopy [28], which is similar to the results that Bers’s group previously reported using confocal microscopy [29]. Thus, heterogeneous activity of mitochondrial Ca2+ handling does exist across mitochondrial subpopulations (and/or within subsarcolemmal mitochondria), but its physiological relevance to mitochondrial and cellular function in cardiomyocytes is still under debate.

Fig. 1. Cardiac mitochondria and mitochondrial Ca2+ influx/efflux mechanisms in adult ventricular myocytes.

A. Schematic diagram of adult ventricle muscle in longitudinal section. Dot window indicates the location of image B. Dot line indicates the location of the cross section shown in panel C. Striated lines indicates the locations of T-tubules and Z-line. Blue areas indicate the location of nucleus. B. Transmitted electron microscopic image of the longitudinal section of a papillary muscle obtained from rat ventricle. Dot window in the low magnification area indicates the location of inserted image. Dot window in the inserted image indicates the location of the schematic diagram shown in panel D. C. Transmitted electron microscopic image of the short axis of a papillary muscle obtained from rat ventricle. The area of a single ventricular myocyte is highlighted by applying the Gaussian filter to the background area. Blue area indicates the location of nucleus. Red areas indicate perinuclear mitochondria. Yellow areas indicate subsarcolemmal mitochondria. D. Schematic diagram of mitochondrial Ca2+ channels/transporters for influx and efflux mechanisms at interfibrillar mitochondrion in adult ventricular myocytes. The channels/transporters which molecular identities are still unknown are shown as black. Red arrows show Ca2+ movements and blue arrows show Na+ ion movements. VLCC, voltage-gated L-type Ca2+ channel; OMM, outer mitochondrial membrane; IMM, inner mitochondrial membrane; mtCaUC, MCU complex. Modified from © Jin O-Uchi et al., 2012. Originally published in the Journal of General Physiology. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201210795.

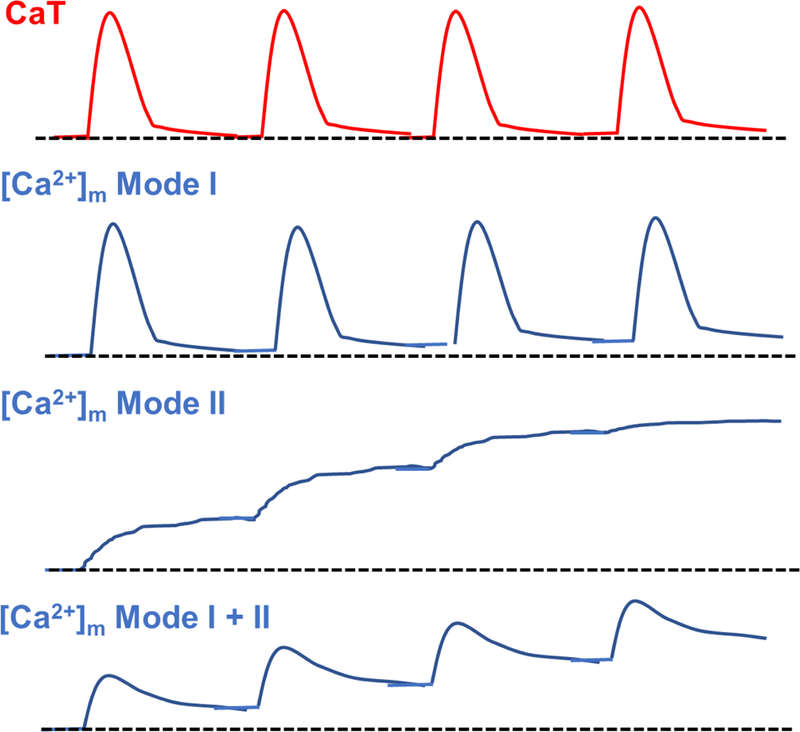

Fig. 2. Kinetics of mitochondrial Ca2+ concentration during excitation-contraction coupling.

The models of [Ca2+]m oscillation in response to Ca2+ transient on a beat-to-beat basis in adult ventricular myocytes under physiological conditions. Red and blue lines show Ca2+ transient and the changes in [Ca2+]m, respectively. Dot lines show indicate initial [Ca2+] in quiescent adult ventricular myocytes. CaT, Ca2+ transient.

In non-cardiac cells, a Ca2+-release channel IP3 receptor is generally involved in Ca2+-mediated crosstalk between ER and mitochondria [30]. In adult ventricular myocytes, Ca2+ release from the SR is exclusively through the RyR2, not the IP3 receptor [19] (Fig.1D). However, Ca2+ release from the IP3 receptor also partly contributes to Ca2+ signaling and cellular contraction in adult atrial myocytes and neonatal cardiomyocytes [31]. The main location of RyR2 expression is along the T-tubule side of the SR near the voltage-gated L-type Ca2+ channels, which tightly controls Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release in adult ventricular myocytes during every heartbeat [19]. Therefore, it is reasonable to believe that high local concentrations of Ca2+ at the T-tubule-SR subspace after Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release can diffuse to nearby mitochondria, especially to interfibrillar mitochondria (Fig.1D), which supports the idea that the mitochondrial network and its close proximity to the ER are a critical determinants for mitochondrial Ca2+ response in non-cardiac cells [32, 33]. Another possibility is that a smaller number of RyR2 is located in the distal end of the SR-facing mitochondria. There is also the possibility of functional coupling of RyR2 and voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC) isoform 2 at the SR-mitochondria contact site as shown in cultured HL-1 atrial muscle cell lines [34]. Although this report is interesting, interaction of VDAC1 (the main VDAC isoform in the heart) and RyR2 was not tested. Moreover, since HL-1 cells are from atrial muscle and do not possess T-Tubule structures like adult ventricular myocytes, it is still unclear whether this molecular architecture is applicable to adult ventricular myocytes. Indeed, the composition and structure of Ca2+ microdomains between SR and mitochondria in adult ventricular myocytes are still under debate. The Bers group showed a relatively uniform distribution of an MCU complex pore-forming protein MCU throughout the mitochondrion using an immunofluorescence assay in rabbit adult ventricular myocytes [35], and thus the part of mitochondrion nearest to the SR Ca2+ release sites mainly works for Ca2+ uptake assessed by confocal line scanning in live cells. On the other hand, using the sub-mitochondrial membrane fraction or isolated mitochondria from mouse and rat hearts, the Csordas and Sheu group recently reported that SR-mitochondrial contact sites contain high amounts of MCU complex components and thus exhibit significantly higher Ca2+ uptake compared to non-contacted mitochondrial membrane [36] (Fig. 1D). The model proposed by the Csordas and Sheu’s group is intriguing, but several issues still need to be addressed. This includes 1) reliability of immunostaining with commercial antibodies against MCU; 2) the structural alteration of contact sites in isolated mitochondria; 3) possibility of species difference (i.e., rodents vs. large animals including human); and lastly 4) unclearness of the molecular mechanism of how the MCU complex is trafficked and retained specifically at SR-mitochondria contact sites. Future experiments need to address 1) whether we can reexamine mitochondrial Ca2+ influx, specifically at interfibrillar mitochondria in intact adult ventricular myocytes to provide quantitative information separated by the distance from T-tubules, and 2) whether we can develop computational models of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake in adult ventricular myocytes that take sub-mitochondrial distribution of MCU complex (i.e., close to SR or other location) into consideration. Lastly, neonatal cardiomyocytes and adult atrial myocytes may exhibit characteristics between non-cardiac cells and adult ventricular myocytes, since these cells have an immature T-tubule structure and smaller gain of Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release compared to adult ventricular myocytes and possess both IP3-receptor and RyR2-based SR Ca2+ releasing mechanisms (though RyR2 is the major releasing site in SR) [31, 37]. Therefore, mitochondrial Ca2+ handling profiles and their contribution to mitochondrial and cellular functions between these three types of cardiomyocytes (neonatal cardiomyocytes, adult atrial myocytes, and adult ventricular myocyte) may be different and require separate investigations. In the following sections, we mainly focus our discussion on adult ventricular myocytes rather than neonatal cardiomyocytes and adult atrial myocytes, based on the major interest in this field.

3. Mitochondrial Ca2+ Channels/Transporters Regulating Mitochondrial Ca2+ Influx in Cardiomyocytes

3.1. Pore-Forming Subunits of Mitochondrial Ca2+ Uniporter Protein Complex

Several channels and transporters have been proposed as molecular mechanisms of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake in cardiomyocytes (see reviews [3]). However, the current consensus is that the main mechanism of Ca2+ entry into the mitochondrial matrix in all cell/tissue types, including cardiomyocytes/heart, is likely via the MCU complex [1, 2, 4, 5] (Fig. 1D). Composed of the MCU pore-forming subunits along with several auxiliary proteins, the MCU complex is an important regulator of [Ca2+]m which is crucial to many cellular processes.

Discovered in 2011 and first reported in two separate seminal studies, the MCU gene (originally known as CCDC109A) encodes a 40-kDa MCU protein with a mitochondrial target sequence at the N-terminus that is cleaved upon the protein’s insertion into the inner mitochondrial membrane [38, 39]. Importantly, this gene is highly conserved across all eukaryotic species [38, 39]. The MCU protein contains two coiled-coil domains and two transmembrane domains [40]. Between the transmembrane domains runs a short motif of amino acids, which contributes to the formation of the Ca2+ channel pore. Though MCU topology was initially debated, it is now widely accepted that the N- and C-termini of MCU are both exposed to the mitochondrial matrix, while the amino acid motif of the pore-forming region faces the intermembrane space [39]. As MCU subunits only contain two transmembrane domains each, it is reasonable to believe that MCU proteins must oligomerize in order to form Ca2+ channels. The initial study using computational models suggests that MCUs oligomerize and form a tetramer [41]. Later, a study using nuclear magnetic resonance proposed a pentameric homo-oligomer [42], but recent studies using cryo-EM a tetramer [43–45] or dimer-of-dimer architecture [46].

Since the elucidation of MCU’s molecular identity, investigations utilizing novel genetic tools to alter MCU expression and/or activity in non-cardiac cells have revealed that changes in MCU expression level alone have no impact on basal mitochondrial membrane potential, O2 consumption, ATP production, and/or mitochondrial morphology (see reviews [1]). However, mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake in both in vitro and in situ systems is significantly abrogated following knockdown of MCU, while MCU overexpression counteracts this effect in knockdown cells. From these findings, it has been concluded that MCU is predominantly responsible for Ca2+ entry into the mitochondrial matrix in non-cardiac cells. The first attempt to genetically manipulate MCU complex activity in primary cardiomyocytes was by the Pozzan’s group, which showed that MCU overexpression or knockdown modulates both cytosolic and mitochondrial Ca2+ handing in rat neonatal cardiomyocytes during spontaneous oscillations [14]. Further investigations were carried out by several groups using adult ventricular myocytes isolated from transgenic mouse lines of MCU knockout [9, 11, 12] or overexpression of dominant-negative MCU (MCU-DN) [15, 16]. These studies clearly confirmed that MCU complex is the major mechanism for mitochondrial Ca2+ influx in adult ventricular myocytes, though it is still controversial whether the modulation of mitochondrial Ca2+ handling can influence cytosolic Ca2+ handling in adult ventricular myocytes (see also section 5).

In addition to MCU, MCUb encoded by CCDC109B, a related gene of CCDC109A, was reported as an endogenous dominant-negative pore forming subunit of MCU complex [41]. Like MCU, MCUb has a mitochondrial target sequence at N-terminus and two predicted transmembrane domains that can target it to the mitochondria and sort it into the inner mitochondrial membrane [41, 47]. However, MCUb has only 50% similarity to the MCU sequence, with key amino acid substitutions (R251W, E256V) in the pore forming region [41]. Thus, the binding of MCUb to MCU may reduce the Ca2+ permeability of MCU complex. Indeed, MCU and MCUb can form hetero-oligomers in mammalian cells [41, 47] and a change in the MCUb:MCU ratio by MCUb overexpression (knockdown) in mammalian cells dramatically decreases (increases) mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake in response to [Ca2+]c elevation [41, 48]. It is worth noting that the ratio of MCU and MCUb mRNA expression varies in different tissues [41], which may correlate to the size of mitochondrial Ca2+-selective currents recorded from mitoplasts from various tissues [49]. In the heart, MCUb expression is significantly higher compared to that in other excitable (e.g., brain and skeletal muscle) and non-excitable tissues (e.g., liver which is widely used in the field of mitochondrial Ca2+ research) [41]. Accordingly, the MCU current measured in whole mitoplasts from mouse hearts was significantly smaller than those from skeletal muscle and liver [49]. Since there are still no reports investigating the role of MCUb in the cardiomyocytes/heart, future directions will involve testing genetic manipulations of the MCUb expression in primary cardiomyocytes or in vivo.

3.2. Auxiliary Subunits of Mitochondrial Ca2+ Uniporter Protein Complex

Mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake was initially thought to be mediated by a single protein, the MCU pore-forming subunit. In fact, in vitro studies by the Rizzuto group demonstrated that recombinant MCU alone in planar lipid bilayers can confer a Ca2+ conductance of 6–7 pS [38, 41]. However, mitoplast patch-clamping revealed that the endogenous channel has a much higher conductance (≅14.3 pS) [50]. While some speculate that this discrepancy is due to the complex natural environment of the inner mitochondrial membrane that is not adequately reflected in the simple planar lipid bilayers, other contributors are the auxiliary subunits endogenously associated with the MCU pore subunits in the inner mitochondrial membrane that allow for higher conductance. Since the discovery of the molecular identities of pore-forming subunit of MCU, several auxiliary subunits were discovered, and their functional roles have been proposed. They include mitochondrial Ca2+-uptake 1 protein (MICU1) [51], MICU2 [52], MICU3 [52, 53], essential MCU regulator (EMRE) [47], and MCU-regulator 1 (MCUR1) [54].

The first regulator of the MCU pore-forming subunit to be discovered was the accessory protein, MICU1. As originally reported by the Mootha lab, the MICU1 gene (initially known as CBARA1/EFHA3) encodes a 54-kDa protein that exhibits two highly conserved EF-hand Ca2+ binding motifs [51]. MICU1 is a soluble membrane-associated protein, but there have been conflicting evidence regarding its sub-mitochondrial localization (see also review [4]). Though some have suggested that MICU1 may reside in the matrix [55, 56], more recent proteome and interactome analyses bolster the reports that MICU1 exists in the intermembrane space [48, 57–59]. Early investigations of MICU1’s regulatory function have revealed its role as a gatekeeper within the MCU complex; that is, MICU1 keeps the MCU pore closed under basal conditions. This conclusion is derived from observations that MICU1 knockdown increases basal [Ca2+]m [60, 61] and MICU1 silencing causes constitutive [Ca2+]m overload even under low [Ca2+]c [54, 55]. MICU1 is also recognized to be a positive regulator of the MCU pore, as MICU1 knockdown has been shown to inhibit mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake in response to [Ca2+]c increase [51, 62]. MICU1 promotes the cooperative activation of the channel under high [Ca2+]c, as reflected by the sigmoidal relationship between [Ca2+]m and [Ca2+]c elevation which is lost in cells with MICU1 knockdown [57].

In the mouse heart, MICU1 mRNA and proteins are detectable [8, 52, 53], but their expression is significantly lower than in other excitable (e.g., brain and skeletal muscle) and non-excitable tissues (e.g., liver) [8, 52, 53]. Indeed, recent clinical reports showed that individuals who possess a homozygous deletion of exon 1 of MICU1 or loss-of-function mutations of MICU1 exhibited phenotypes of skeletal muscle or combined skeletal muscle and neurological disorders [63–65]. Cardiac disorders were not documented in these patients. Moreover, the fibroblasts from these patients clearly exhibited abnormal mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake profiles [63, 64, 66]. In line with these clinical reports, Finkel and Murphy`s group generated MICU1 knockout mice by CRISPR-mediated methods [67]. Deletion of MICU1 in this mouse line resulted in increased resting [Ca2+]m levels, altered mitochondrial morphology, and reduced ATP, concomitant with an in-vivo phenotype of ataxia and muscle weakness [67]. MICU1 deletion also showed increased perinatal mortality, but a cardiac phenotype was not observed in this mouse line [67]. These reports are consistent with the idea that MICU1 is the gatekeeper of mitochondrial Ca2+-uptake and that the observed clinical phenotypes may correlate with the MICU1 expression pattern in each organ/tissue. In addition, Paillard and her colleagues proposed that the low MICU1:MCU ratio in the heart lowered the [Ca2+] threshold for Ca2+ uptake and activation of oxidative metabolism, but decreased the cooperativity of uniporter activation compared to organs with higher MICU1 expression and MICU1:MCU ratio (e.g., liver) [8]. Finally, MICU1 overexpression in the cardiomyocytes, which subsequently increases MICU1:MCU ratio, promotes cardiomyocytes to exhibit liver-like mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake and cardiac dysfunction in vivo. Thus, the lower expression of MICU1 in cardiomyocytes dictates the proportion of MICU1-free and MICU1-associated MCU, which forms cardiac-specific MCU complex biophysical characteristics distinct from other organs and controls downstream oxidative metabolism in the heart. However, the currently available MICU1 knockout mouse lines are all conventional knockouts [67, 68] and may have compensational adaptation of cellular Ca2+ handling similar to the case of conventional MCU knockout mice [12]. Thus, cardiomyocyte-specific and inducible MICU1 knockout strategy in vivo or simply transient knockout of MICU1 in cultured adult cardiomyocyte system may provide more precise information regarding the role of MICU1 in adult cardiomyocytes.

In addition to MICU1, two isoforms of MICU1, MICU2 and MICU3 (encoded by EFHA1 and EFHA2, respectively), were discovered by the Moothàs group [52]. MICU2 and MICU3 share 25% sequence homology with MICU1 and similarly possess an N-terminal mitochondrial target sequence and two EF-hands [52, 53]. However, the three isoforms have varying expression profiles in different tissue types, as MICU1 and MICU2 are ubiquitously expressed including in the heart while MICU3 is only found in the central nervous system and, to a lesser extent, skeletal muscle [52, 53] and is almost undetectable in the heart [53]. Like MICU1, MICU2 is thought to act as a gatekeeper, but there still remain opposing views regarding whether MICU1 or MICU2 plays the predominant role in gatekeeping (see review [1, 69]). The investigation of the role of MICU3 has just begun with the De Stefani group showing that MICU3 acts as an enhancer of MCU complex-dependent mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake similar to MICU1 in neurons [53]. Since MICU2 and MICU3 do not form a disulfide bond-mediated heterodimer, but MICU1 is capable of forming one with MICU2 or MICU3, MICU1 is proposed to serve as a docking site for the other family members that retains them within MCU complex [53, 60].

As mentioned above, MICU1 expression is relatively low in the heart. On the contrary, MICU2 expression levels in the heart are higher than (or comparable to) other organs such as skeletal muscle, brain, and liver [8, 53], suggesting that MICU2 may play a more important role in cardiac function under physiological and pathological conditions compared to MICU1. Indeed, Sideman’s group tested conventional MICU2 knockout in vivo and found that MICU2 deletion showed prolonged Ca2+ removal and relaxation time in cardiomyocytes and mild diastolic dysfunction in vivo [13], which was not reported in conventional MICU2 knockout mice [67]. However, the mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake profile in cardiac mitochondria was not assessed in this mouse line, and MICU2 deletion caused subsequent loss of MCU, possibly due to destabilization of MCU complex. Further studies are needed to more precisely assess whether the phenotypes observed in this mouse line are direct or indirect effect of the loss of MICU2 protein function. Similar to the case of MICU1 research in the heart (see above), a cardiomyocyte-specific and inducible MICU2 knockout strategy in vivo or transient knockout of MICU2 in cultured adult cardiomyocyte system may be required for understanding the role of MICU2 in adult cardiomyocytes. Finally, a recent clinical report of individuals who possess a MICU2 mutation that causes the deletion of full length MICU2 showed that those with mutation exhibited a neurodevelopmental disorder, but no cardiac phenotype [70]. However, these observations in patients do not preclude a significant role of MICU2 in cardiomyocytes. Compensatory pathways induced by MICU2 deletion during development may allow the normal cardiac function in the patient, which is similar to the case of conventional MCU knockout mice [12].

Another important auxiliary subunit in the MCU complex is the EMRE, also first reported by the Mootha lab [47]. The EMRE gene (initially known as C22ORF32) encodes a 10-kDa protein with a mitochondrial target sequence at the N-terminus and an aspartate-rich C-terminus. Located at the inner mitochondrial membrane, the EMRE protein is comprised of a single transmembrane domain. With regard to its topology, substantial evidence supports a C-terminal region exposed to the inner mitochondrial membrane and N-terminal region facing the matrix [10, 71], although electrophysiological studies by Foskett group may suggest the opposite topology [61]. EMRE appears to be an essential accessory protein for activating MCU complex in situ, as MCU overexpression cannot recover uniporter activity in EMRE knockdown cells [61]. This idea was further supported by the electrophysiological studies from several groups [61, 72]. In addition, EMRE is proposed to serve as a bridge between MCU and MICU½, which transmits changes in [Ca2+]c to the MCU complex, activating mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake in situ [47, 59]. Finally, Foskett group proposed that EMRE itself serves as a [Ca2+] sensor of the matrix side, but further investigation is needed to confirm EMRE topology (see above).

Based on these reports showing the critical importance of EMRE for MCU complex activity in cell system, global EMRE deletion in vivo is likely to increase lethality and/or cause in vivo pathological phenotypes since EMRE is ubiquitously expressed in all organs, including in the heart [47]. Nevertheless, the proposed bridge function of EMRE is still controversial since MCU alone is sufficient to form a Ca2+ channel and MICU1 is capable of activating this MCU channel in the absence of EMRE in planar lipid bilayers [38, 60]. Currently, EMRE knockdown has not been tested in the cultured cardiomyocyte systems. Finkel and Murphy’s group generated an EMRE knockout mouse line via CRISPR-mediated methods, but the cellular function of cardiomyocytes from this mouse line was not investigated in this report [67]. Importantly, this reported EMRE-deletion mouse line did not show any changes in motility and body growth. However, a different mouse line generated by an independent consortium results in complete embryo lethality (see http://www.mousephenotype.org/data/genes/MGI:1916279). These differences may be due to the different genetic backgrounds of mice used, but conventional deletion of EMRE may not provide any further information regarding the role of EMRE in adult cardiomyocytes, due to their compensation during development as seen in conventional knockout mouse lines of MCU [12], MICU1 [67, 68] and MICU2 [13]. Further studies such as transient knockout of EMRE in cultured adult cardiomyocyte system or cardiomyocyte-specific and inducible EMRE knockout strategy in vivo will be required.

Apart from the MCU complex components listed above, several proteins are proposed to serve as regulatory proteins for MCU complex. These include MCUR1 (encoded by CCDC90A) [10, 54], SLC25A23 [73], uncoupling proteins 2/3 (UCP2/3) [74, 75], Miro1 [76] and ERp57 [77]. Importantly, all these proteins are expressed in cardiomyocytes [10, 73, 78–80], but it is still controversial whether these proteins modulate MCU complex activity directly or indirectly due to the limited number of reports from only a few laboratories. For instance, Madesh’s group reported that MCUR1 serves as a scaffold for the entire MCU complex and is required for normal cellular bioenergetics and function in cultured cell lines [10, 54]. They also generated cardiac-specific MCUR1 knockout mice and confirmed the role of MCUR1 in MCU complex activity in the adult ventricular myocytes [10]. On the other hand, Shoubridge and his colleagues proposed that MCUR1 knockdown causes the inhibition of the activity of electron transport chain via a decrease of cytochrome c oxidase (complex IV) assembly and activity, indicating that the impact of knockdown MCUR1 on MCU activity may be an indirect effect due to the changes in the mitochondrial membrane potential. To confirm the involvement of changes in the mitochondrial membrane potential with or without MCUR1, Foskett’s group measured MCU-complex activity by mitoplast patch clamp isolated from MCUR1 knockout and control cell lines, where the mitochondrial membrane potential was precisely controlled [81]. Through this experiment, they reported that MCUR1 is a regulator of MCU complex independent of mitochondrial membrane potential. However, an important question still remains whether MCUR1 directly binds to MCU (or the MCU complex) to serve as a direct regulatory protein or its function to MCU complex is indirect. Use of planar lipid bilayers may be capable of answering this questions similar to the case of MICU1 and MCU interactions [38, 60].

3.3. Other Mitochondrial Ca2+ Influx Mechanisms

As described in the prior section, ground-breaking studies have uncovered the molecular identities of the components of the MCU complex, which serves as a major mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake mechanism in various cell types/tissues, including adult ventricular myocytes /hearts. For instance, Kwong and her colleagues generated cardiomyocyte-specific inducible MCU knockout mice, isolated cardiomyocytes from this mouse line, and observed mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake in the permeabilized adult ventricular myocytes [9]. In this mouse line, MCU protein expression in the cardiac mitochondria was reduced to 20% of that in control animals. In MCU knockout adult ventricular myocytes, mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake was almost completely abolished (10–20% of that in control adult ventricular myocytes). Importantly, the treatment of a conventional MCU inhibitor Ru360 did not confer additional inhibition of residual mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake in MCU knockout adult ventricular myocytes. This observation indicates that MCU may not be the sole mechanism for transducing the changes of [Ca2+]c into changes of [Ca2+]m in cardiomyocytes. Indeed, before the discovery of the molecular identity of MCU complex, several different types of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake mechanisms were functionally identified via multiple experimental approaches. These mechanisms include 1) Rapid Uptake Mode (RaM) [82, 83], 2) mitochondrial RyR type1 (RyR1) [84–87], and 3) Ca2+-selective conductance (mCa1 and mCa2) [75, 88, 89] (Fig.1D). Of these proposed mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake mechanisms, mitochondrial RyR1 is the only one whose molecular identity has been investgated using RyR isoform specific antibodies, but the genetic manipulations of RyR1 in cardiomcyotes were not yet tested. To date, the molecular identities of RaM, mCa1 and mCa2 have not yet been invetigated. Studies have also indicated that the mCa1 may possibly be the current via MCU complex activity since mCa1 has the classical features of an MCU current [75, 88, 89] (i.e., its sensitivity to a ruthenium red inhibition [90]), similar to the case of IMiCa [50, 91]. Conversely, mCa2 is insensitive to ruthenium red [88]. Importantly, ruthenium red, a classic MCU inhibitor, can also inhibit RaM at higher concentrations, but oppositely activates RaM at lower concentrations [92]. Thus, the observations of these pharmacological characteristcs have resulted in the conclusion that mCa2, RaM and mitochondrial RyR1 in cardiac mitochondria likely mediate mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake through an MCU-independent pathway that may involve different molecular mechanisms. Importanlty, Hajnoczky’s group also showed that MICU1 interaction with MCU controls MCU’s sensitivity to Ru360 [93], indicating that MCU complexes with or without MICU1 exhibit diffent sensitivities to conventional MCU inhibitors. Thus, we need to revisit the molecular identities of mCa2, RaM and mitochondrial RyR1 using genetic manipulations of MCU complex components including MCU and MICU1 to test whether these pathways are exculsively MCU-complex independent since most of these reports are from the pre-MCU era (i.e., before 2011).

4. Mitochondrial Ca2+ Channels/Transporters Regulating Mitochondrial Ca2+ Efflux in Cardiomyocytes

4.1. Mitochondrial Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCLX)

Historically, multiple Ca2+ efflux mechanisms including NCX and and/or H+/Ca2+ exchangers have been proposed from pharmacological and physiological experiments using isolated mitochondria from various organs (see reviews [3, 94]). Using isolated cardiac mitochondria, Carafoli and his colleagues firstly reported that efflux of Ca2+ from the mitochondrial matrix is dependent on the extra-mitochondrial Na+ concentration ([Na+]) [95]. This observation was confirmed by other groups using isolated mitochondria from various tissues [96, 97]. Activity of H+/Ca2+ exchanger is also found in non-excitable cells including liver cells, suggesting that tissue-specific mitochondrial Ca2+-efflux mechanisms might exist. Subsequently, Garlid group purified a ≅110-Da protein from bovine cardiac mitochondria, and this protein was capable of catalyzing Na+/Ca2+, and Na+/Li+ exchange after reconstitution in the liposome [98]. Finally, Palty and his colleagues reported that the molecular identity of a mitochondria-localized NCX is NCLX [99] (Fig. 1D), a recently cloned member of the NCX superfamily [100, 101]. They found that 1) brain and heart mitochondria contain 100-kDa proteins that correspond to an NCLX dimer; 2) mitochondrial NCLX is expressed in the inner mitochondrial membrane; 3) NCLX knockdown (overexpression) significantly reduces (increases) mitochondrial Ca2+ efflux [99]. However, several questions and controversies surrounding NCLX functions remain; 1) What is the stoichiometry of Na+/Ca2+ exchange in cardiac mitochondria (Na+:Ca2+ = 1:2 [102] or 1:3 [103, 104])?; 2) Why can only NCLX traffic to the mitochondria in addition to the sarcolemma among the NCX superfamily?; 3) How does NCLX dynamically contribute to Ca2+ transport during excitation-contraction coupling in cardiomyocytes (see review [94])? Nevertheless, Luongo and his colleagues showed that a cardiac-specific and inducible knockout of NCLX promotes inhibition of mitochondrial Ca2+ efflux rate, mitochondrial Ca2+ overload, increased necrotic cell death, and increased sudden death of the animal, confirming that NCLX is critical in controlling [Ca2+]m [17]. This report is consistent with previous observations from Maack and his colleagues that the primary mitochondrial Ca2+ efflux mechanism in cardiac mitochondria is indeed cytosolic [Na+] ([Na+]c)-dependent [105].

4.2. Mitochondrial Permeability Transition Pore (mPTP)

Mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) is a large, non-specific pore that opens through the inner mitochondrial membrane to the outer mitochondrial membrane and causes the release of proapoptotic proteins from the mitochondria, subsequently leading to cell death under pathophysiological conditions such as mitochondrial Ca2+ overload and elevated oxidative stress in various cell types including cardiomyocytes [106–108] (Fig. 1D and3). Though the molecular identity of mPTP has been long-debated, recent studies in non-cardiac cells strongly suggest that mitochondrial ATP synthase (F0F1 ATP synthase) is a critical component of the mPTP and/or the c-subunit of mitochondrial ATP synthase serves as a pore-forming subunit of mPTP [109, 110]. Due to the pore size (approximately 3 nm), mPTP opening also promotes equilibration of cofactors and ions across the inner mitochondrial membrane, including Ca2+, which leads to the disruption of the mitochondrial membrane potential and ATP production, followed by mitochondrial swelling until the outer mitochondrial membrane eventually ruptures. Therefore, it is also now widely recognized that mPTP is a major cause of cardiac reperfusion injury and serves as an effective target for cardioprotection [106].

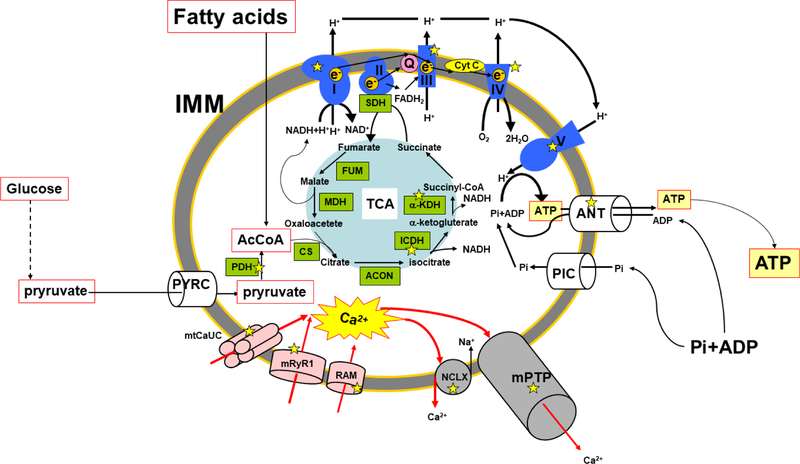

Fig. 3. Mitochondrial Ca2+ and the regulation of ATP synthesis in the inner mitochondrial membrane of cardiac mitochondria.

Ca2+-dependent ion channels/ transporters and enzymes are indicated with yellow stars. Pink, blue, and grey structures are mitochondrial Ca2+ influx mechanisms, electron transport chain, mitochondrial Ca2+ efflux mechanisms, respectively. Green boxes are enzymes involved in TCA cycle at the matrix. Red allows are the movements of Ca2+ ion. The outer mitochondrial membrane is not shown in this scheme. PYRC, pyruvate carrier; AcCoA, Acetyl-CoA; PIC, Pi carrier; SDH, Succinate dehydrogenase; FUM, Fumarase; MDH, Malate dehydrogenase; ACON, aconitase; CS, Citrate synthase; ANT, adenine nucleotide translocator; IMM, inner mitochondrial membrane; mtCaUC, MCU complex.

Through electrophysiological measurements, several groups reported the existence of a large-channel activity called the mitochondrial mega channel (which was believed to be the mPTP) in reconstituted proteins obtained from the inner mitochondrial membrane. It was determined that this channel can open and close transiently (“flicker”) at its low conductance state (see review [111]). Therefore, mPTP is also proposed as one of the Ca2+ efflux mechanisms in both physiological and pathophysiological conditions (Fig.1D). Indeed, the Stienen group recently reported in rabbit adult ventricular myocytes that pharmacological inhibition of NCLX results in increased basal [Ca2+]m, but also accelerates matrix Ca2+ release under physiological Ca2+ transient [112], indicating that NCLX is not the sole mechanism for matrix Ca2+ efflux in cardiac mitochondria. Saotome and his colleagues showed in rat adult ventricular myocytes that mPTP allows Ca2+ ions to pass under the dissipation of mitochondrial membrane potential [113]. In addition, the Morkentin group used a mouse line lacking cyclophilin D, a known regulator of mPTP, to show that mPTP behaves like a Ca2+ valve that limits excessive [Ca2+]m elevation in cardiac mitochondria [114]. These reports suggest that mPTP may serve as an additional mitochondrial Ca2+ efflux mechanism in cardiac mitochondria under pathological conditions. Moreover, Wang’s lab reported using rat adult ventricular myocytes with mitochondria-targeted circular permuted yellow florescence protein (mt-cpYFP) that mitochondrial Ca2+ accumulation during physiological excitation-contraction coupling can stimulate transient mPTP opening, which contributes to a matrix Ca2+ efflux mechanism in addition to NCLX [115]. On the other hand, the Pinton group genetically modulated the expression level of the c subunit of F0F1 ATP synthesis in HeLa cells and concluded that mPTP is not likely to participate in mitochondrial Ca2+ handling under physiological conditions [116]. Current issues in studying mPTP and mitochondrial Ca2+ in the cardiomyocytes are as follows: 1) limited information regarding the origin of the changes in mt-cpYFP fluoresce (“mitochondrial flashes”) [117]; 2) limited tools to directly detect mPTP opening events in cardiac mitochondria in a beat-to-beat manner other than mt-cpYFP; and 3) the intrinsic challenge of knocking down of F0F1 ATP synthesis (or its parts).

5. Mitochondrial Ca2+ Homeostasis and the Regulation of Cytosolic Ca2+ Handling in Cardiomyocytes

As described in the prior sections 3 and 4, cardiac mitochondria possess all the molecular components for Ca2+ uptake and release. Indeed, recent studies using the adult ventricular myocytes from conditional and cardiomyocyte-specific MCU or NCLX knockout mice clearly confirmed that MCU and NCLX are the main mechanisms for transducing changes in [Ca2+]c into changes in [Ca2+]m [9, 11, 17]. However, a large question remains regarding the kinetics of [Ca2+]m homeostasis (uptake and release) in adult ventricular myocytes during excitation-contraction coupling. Moreover, it is also highly controversial whether cardiac mitochondria can take up and release Ca2+ in each heart beat (an oscillator) (Model I) or act as an integrator by taking up Ca2+ gradually resulting in steady-state [Ca2+]m increase (Model II) (see also review [118]) (Fig.2). This appears to be species-dependent based on observations from prior studies utilizing Ca2+-sensitive dyes loaded into the mitochondria of intact adult ventricular myocytes: Small animals (e.g., mice and rats) do not show beat-to-beat oscillation, relatively larger animals (e.g., guinea pigs and rabbits) have mitochondrial Ca2+ oscillations in response to Ca2+ transient [118, 119]. These observations have been revisited by applying recently developed mitochondria matrix-targeted biosensors in adult ventricular myocytes. These studies found that mitochondrial Ca2+ oscillations in response to Ca2+ transient are detectable in various species including mice, rats, and rabbits [11, 17, 112, 120, 121]. More importantly, occurrence of mitochondrial Ca2+ oscillations in response to Ca2+ transient observed by the genetic biosensors is dependent on the pacing frequency: mitochondrial Ca2+ oscillations are detectable at low frequency pacing (e.g., 0.1 Hz) (Mode I + II in Fig. 2), and higher frequency pacing (e.g., ≥ 0.5 Hz) increases basal [Ca2+]m time-dependently and rather exhibit a tonic increase of [Ca2+]m [112, 120, 121] (Mode II in Fig. 2). Thus, the existence of beat-to-beat based mitochondrial Ca2+ oscillation and its physiological relevance still need further investigation and discussion. Nevertheless, these reports strongly suggest that [Ca2+]m in cardiomyocytes is determined by the dynamic balance of influx and efflux rate. Thus, physiological heart rate maintains [Ca2+]m slightly higher than diastolic [Ca2+]c (≅ 100 nM) while more rapid heart rates, such as in “fight-or-flight” responses, increase tonic [Ca2+]m. Indeed, Boyman and his colleagues developed a mathematical model of adult ventricular myocytes that includes a single influx (MCU) and efflux (NCLX) mechanism and showed that 0.5-Hz pacing causes [Ca2+]m to reach the higher steady-state condition (from 200 nM in quiescent cells to 300–900 nM after pacing) [94] (Mode II in Fig. 2). Wust and his colleagues’ model also showed that higher pacing increases basal [Ca2+]m to 200–600 nM [112]. Finally, it should be mentioned that these mathematical models did not include the existence of heterogenetic Ca2+ handing among subpopulations of mitochondria as well as the mitochondrial networks (see section 2) since most of the estimates are from prior studies using isolated mitochondria.

As described in sections 3.1 and 3.2, the MCU complex has been widely recognized as the main mechanism for mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake in various cell types/tissues including cardiomyocytes. Indeed, prior studies using non-cardiac cells with genetic MCU knockout (or inhibition) and overexpression showed that the changes in the kinetics of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake are capable of manipulating the magnitude of transient [Ca2+]c elevations evoked by physiological ER Ca2+ releases by IP3 or ER Ca2+ leak [38, 41, 48], indicating that mitochondria have relatively high Ca2+ buffering capacity and can remove large amounts of cytosolic Ca2+ comparable to that removed by SERCA at the ER. Recently, Pozzan group showed that MCU overexpression or knockdown can modulate the size of Ca2+ transient in rat neonatal cardiomyocytes during spontaneous oscillations [14], which is consistent with the idea that mitochondria serve as a dynamic buffer of [Ca2+]c in non-cardiac cells. Although mitochondria occupy 35% of the cytosolic space in adult ventricular myocytes and are capable of uptaking Ca2+ (see also section 2 and 3), it is unlikely to see a large amount of net Ca2+ fluxes during Ca2+ transient under physiological conditions. Bers and his colleagues showed in their early studies that a majority of the Ca2+ forming Ca2+ transient (≅ 99%), which comes from the extracellular space via voltage-gated L-type Ca2+ channels and from the SR via RyR2, is removed by sarcolemma-localized NCX and SERCA at the SR; the remaining amount of Ca2+ is removed by the mitochondria and the sarcolemmal Ca2+-ATPase pump [122–124]. This suggests that mitochondrial Ca2+ handling has little to no influence on cytosolic Ca2+ handling on a beat-to-beat basis in adult ventricular myocytes under physiological conditions. Indeed, recent studies with mitochondria matrix-targeted Ca2+ biosensors showed that acute inhibition of MCU complex function by pharmacological (Ru360 treatment) [35] or genetic (cardiomyocyte-specific and inducible MCU knockout) [11] approaches does not change the magnitude and kinetics of Ca2+ transient in adult ventricular myocytes. However, chronic inhibition of MCU by cardiac-specific overexpression of MCU-DN promotes increased systolic and diastolic [Ca2+]c [15] in adult ventricular myocytes, suggesting that chronic modification of MCU complex activation may time-dependently impact cytosolic Ca2+ handing such as under pathological conditions (see section 7). Finally, it is worth mentioning that mitochondria may serve as a significant dynamic buffer of [Ca2+]c under physiological conditions on a beat-to-beat basis in other types of cardiomyocytes such as neonatal cardiomyocytes [14], although the MCU complex is not likely to be involved in cytosolic Ca2+ handling in adult ventricular myocytes. Since neonatal cardiomyocytes, adult atrial myocytes, and cardiomyocytes derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells have fewer T-tubules and smaller gain of Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release compared to adult ventricular myocytes, the MCU complex and/or NCLX may have a larger contribution to cytosolic Ca2+ handling [14, 28, 125, 126]. Indeed, using genetically engineered mitochondria-targeted Ca2+ biosensors, several groups clearly showed that spontaneous beating promotes beat-to-beat mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake in neonatal cardiomyocytes [14, 28]. Moreover, Morad’s group also showed that mitochondrial Ca2+ buffering influences the activity of voltage-gated L-type Ca2+ channel at the plasma membrane in neonatal cardiomyocytes [127]. Quantitative and simultaneous measurements of cytosolic Ca2+ and mitochondrial Ca2+ kinetics combined with appropriate genetic modification of MCU complex activity will help elucidate the contribution of mitochondrial Ca2+ handing to the formation of Ca2+ transient in each type of cardiomyocytes.

6. Mitochondrial Ca2+ Homeostasis and the Regulation of ATP Synthesis in Cardiomyocytes

Under physiological conditions, fatty acids are the main substrate (~60–90%) utilized for energy in cardiac muscles [128, 129] (Fig. 3). The heart generates the majority of ATP (≅ 95%) from oxidative phosphorylation in the mitochondria and the remaining portion of ATP is derived from glycolysis at the cytosol and the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle at the mitochondrial matrix [128, 129] (Fig.3). ATP generated by these processes supplies the fuel for cardiac muscle contraction as well as ion-pump activity (e.g., SERCA) during excitation-contraction coupling.

Several early studies elucidated the Ca2+ sensitivities of key rate-limiting enzymes in the TCA cycle, which include membrane bound glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GPDH), isocitrate dehydrogenase (ICDH), α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase (KDH), and pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) (see also reviews [21, 130]) (Fig. 3): GPDH is activated by Ca2+ binding [131]; Ca2+ directly binds to and increases the affinity of ICDH for isocitrate and KDH for α-ketoglutarate [132, 133]; and Ca2+-dependent dephosphorylation activates PDH [134]. Thus, these initial reports suggest that increased [Ca2+]m may stimulate the TCA cycle to produce more substrates (e.g., reduced cofactors and electrons) that drive the electron transport chain for ATP synthesis [132], though this idea was mostly based on the results of in vitro enzyme studies.

In addition to the TCA cycle, the most prominent contribution of the mitochondria to cellular metabolism is their capacity to generate ATP via oxidative phosphorylation at the electron transport chain, a concerted series of redox reactions catalyzed by four multi-subunit enzymes embedded in the inner mitochondrial membrane (Complex I-IV) and two soluble factors, cytochrome c and coenzyme Q10, that function as electron shuttles within the inner mitochondrial membrane. The major substrates for oxidative phosphorylation, a reduced form of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) and a hydroquinone form of flavin adenine dinucleotide (FADH2), are supplied via beta-oxidation of fatty acids, but this mechanism is less regulated by Ca2+ compared to glycolysis, TCA cycle, or oxidative phosphorylation [135]. F1F0 ATP synthase (Complex V) in heart mitochondria is known to be directly or indirectly regulated by [Ca2+]m [136, 137], but a recent report from Baraban group using skeletal muscle mitochondria suggests that the activity of the proton pumps in the electron transport chain (Complex I, III and IV) may also have Ca2+-dependent regulation [138] (Fig. 3). In addition to its impact on the TCA cycle and electron transport chain, [Ca2+]m indirectly activates the adenine nucleotide translocator in heart mitochondria, which transports adenosine diphosphate (ADP) into the mitochondrial matrix, thereby indirectly stimulating ATP synthase in the matrix [139] (Fig. 3). Taken together, these initial reports suggest that mitochondrial Ca2+ may regulate 1) Ca2+-dependent dehydrogenases at the mitochondrial matrix, which supply electrons to the electron transport chain; 2) the activity of the components of electron transport chain; and 3) the activity of adenine nucleotide translocator, which stimulates ATP production in the mitochondria.

As described in section 3, the discovery of the molecular identity of MCU complex, the mechanism responsible for the main mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake in mammalian cells, opened up exciting opportunities for precisely investigating the role of mitochondrial Ca2+ in modulating mitochondrial bioenergetics with genetic approaches, such as knockdown or silencing of the pore-forming subunit MCU. Although there are almost no reports of genetic inhibition or activation of the MCU complex in cultured adult cardiomyocyte systems, various transgenic mouse lines that were generated to assess the role of MCU complex in mitochondrial Ca2+ handling and cellular bioenergetics in adult ventricular myocytes [9, 11, 12, 15, 16, 140]. Therefore, here we mainly discuss the results from the cardiomyocyte-specific and inducible MCU knockout mice [9, 11], since chronic inhibition of MCU in vivo [12, 15, 140] may cause the adaptation/compensation in cellular Ca2+ handling or bioenergetics as well as activate MCU (or mitochondrial Ca2+)-independent pathway [141]. Adult ventricular myocytes from cardiomyocyte-specific and inducible MCU knockout mice displayed almost complete ablation of their mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake function, but no changes in their basal [Ca2+]m [9, 11]. Moreover, these MCU knockout mice displayed no changes in their basal energy metabolism levels or their cardiac performance compared to wild-type animals, although decreases in oxygen consumption rate were detected after β- adrenergic stimulation [9, 11]. These results indicate that 1) basal [Ca2+]m is maintained by an MCU complex-independent mechanism; 2) basal [Ca2+]m is sufficient to activate ATP production in the cardiac mitochondria to supply basal energy for maintaining physiological heartbeat; 3) mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake via MCU complex is required for matching the energy production to acute increases in workload. Basal [Ca2+]m is sufficient for the maintenance of the dehydrogenase activity in the mitochondrial matrix, and the amount of NADH and FADH2 needed to supply electron transport chain may not change significantly in response to alterations in [Ca2+]m due to the lower Ca2+-sensitivity of this mechanism. Thus, MCU-KO mice do not exhibit energy crisis at basal conditions. This also suggests that basal [Ca2+]m is maintained by MCU complex-independent mechanisms, possibly involving NCLX (see section 4.1) or other mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake mechanisms (see section 3.3). Collectively, these results indicate that increases in [Ca2+]m may at least play a significant role in boosting ATP production during acute additional energy demands – such as “fight-or-flight” responses – in the heart. However, further investigations are required to clarify the role of basal [Ca2+]m in mitochondrial ATP synthesis, which is important for maintaining life. It should be noted that basal [Ca2+]m, kinetics of mitochondrial Ca2+ flux, and the speed of [Ca2+]m-mediated ATP production during heartbeats may differ between small animals commonly used in the experiments and large animals including humans, because their heart rates (and possibly the rates of ATP consumption) are completely different. Finally, it should also be noted that this idea of the basal [Ca2+]m formation and [Ca2+]m-mediated ATP production may not be directly applicable to other cardiomyocytes (e.g., adult atrial myocytes and neonatal cardiomyocytes) or to the other cytosolic Ca2+ oscillation conditions (e.g., spontaneous beating). Approaches such as simultaneous measurements of mitochondrial Ca2+ flux and mitochondrial ATP levels on a beat-to-beat-basis in adult ventricular myocytes from both small and large animals using a recently-invented ATP biosensor [142] may provide further information for resolving this question in the future.

7. Mitochondrial Ca2+ Homeostasis and Cardiac Pathophysiology

Dysregulation of cytosolic Ca2+ cycling in cardiomyocytes is frequently observed under pathophysiological conditions and well established as an important mediator of cardiovascular diseases including heart failure and cardiac arrythmia [143, 144]. Although mitochondrial dysfunction is frequently associated with cardiac pathological conditions, it is still controversial whether dysregulation of mitochondrial Ca2+ handling contributes to cardiac disease formation and progression due to the limited information regarding mitochondrial Ca2+ handling from clinical samples [17, 88, 145]: Luongo and his colleagues showed that mRNA levels of NCLX and MICU1 (but not MCU) are increased in ischemic hearts compared to non-failing hearts [17]; Zaglia and her colleagues showed that MCU protein expression in the heart is higher in patients with aortic stenosis [145]; and Hoppe’s group used mitoplasts from human failing heart to demonstrate that mitochondrial Ca2+ currents, mCa1 and 2, are smaller than those in non-failing hearts [88]. Nevertheless, changes in mitochondrial Ca2+ handling and [Ca2+]m (increase or decrease) concomitant with mitochondrial and cardiomyocyte dysfunction have been well reported in various animal models of cardiac diseases and transgenic mice that have genetic modifications of mitochondrial Ca2+ handling proteins (see also reviews [2, 5, 146]). Therefore, we separately discuss here the possible molecular mechanisms of how increased or decreased [Ca2+]m cause cardiac dysfunction.

7.1. Mitochondrial Ca2+ Overload and Cardiac Pathology

It is well-documented that a dramatically increased mitochondrial Ca2+ level (i.e., mitochondrial Ca2+ overload) causes cardiac dysfunction, mainly via cardiomyocyte death in various animal disease models [9, 11, 147–149]. There are at least two key mechanisms by which elevated [Ca2+]m promotes cardiomyocyte dysfunction and/or death: 1) mitochondrial ROS generation and 2) mPTP opening.

The electron transport chain within the inner mitochondrial membrane is a primary source of ROS in excitable cells including cardiomyocytes, as the slippage of electrons from the electron transport chain to molecular O2 during oxidative phosphorylation causes the formation of oxygen free radicals called superoxide [150]. As mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake slowly increases the rate of energy metabolism, the increased activity of the TCA cycle via prolonged increase in [Ca2+]m results in increased electron leakage and thus superoxide formation at the electron transport chain. Furthermore, mitochondrial Ca2+ overload reduces mitochondrial ROS scavenging capacity, as Ca2+ directly inhibits glutathione reductase, a prominent antioxidant in the matrix [151]. Though ROS are important signaling molecules in several cellular processes under physiological conditions, mitochondrial Ca2+-mediated ROS overproduction provides post-translational modifications to cytosolic Ca2+-handling proteins (e.g., RyR2), followed by cytosolic Ca2+-handling dysfunction and mPTP opening, which results in cardiomyocyte apoptosis [147]. Interestingly, while mitochondrial ROS elevation can lead to mPTP opening, in some cases, transient mPTP opening can also result in burst production of superoxide (i.e., mitochondrial flashes) and acute increases of mitochondrial ROS levels [152]. Thus, there may exist a bidirectional relationship between mPTP opening and mitochondrial ROS accumulation.

Another well-documented mechanism underlying mitochondrial Ca2+ overload-mediated cardiomyocyte death is [Ca2+]m-dependent mPTP activation, which is frequently observed under ischemic/reperfusion injury [109]. Indeed, a cardiomyocyte-specific and inducible MCU knockout model and NCLX-overexpression model are protected against ischemic/reperfusion injury [9, 11, 17], indicating that mitochondrial Ca2+ overload is the key mediator of acute cardiac dysfunction such as in ischemic/reperfusion injury via mitochondrial ROS generation and mPTP activation. On the other hand, chronic cardiac dysfunction such as pressure overload-induced heart failure also causes the dysfunction of cytosolic Ca2+ handling and [Ca2+]c overload, but the involvement of [Ca2+]m overload in the progression of heart failure is still controversial compared to that in ischemic/reperfusion injury as described above. For instance, cardiomyocyte-specific and inducible MCU deletion did not exhibit protective effects against surgical transverse aortic constriction [9, 11], while pharmacological inhibition of MCU does provide some cardioprotective effects [153]. Xie and his colleagues used a non-ischemic heart failure model induced by hypertension resulting from unilateral nephrectomy, deoxycorticosterone acetate (DOCA) treatment, and addition of salt to drinking water and showed that cardiac mitochondria from this animal model has mitochondrial Ca2+ overload and that pharmacological MCU inhibition or genetic MCU deletion protects the heart from early afterdepolarizations promoted by heart failure remodeling [148], though they used conventional MCU knockout mouse line [12] in this report. Elrod’s group also showed that cardiomyocyte-specific and inducible NCLX deletion causes acute myocardial dysfunction and fulminant heart failure with a high incidence of sudden cardiac death [17]. However, since these animal models also showed severe bradycardia and long QT before death, it is still not clear whether this heart failure is solely mediated via ventricular myocyte dysfunction or whether dysregulation of other specific cardiomyocytes such as pacemaker cells and/or His-Purkinjie system also play a role. Future experiments are needed to precisely assess the role of mitochondrial Ca2+ in the progression of chronic cardiac dysfunction by measuring [Ca2+]m and mitochondrial functions at different time points.

Although the main cause of increased [Ca2+]m may be [Ca2+]c elevation under pathophysiological conditions, several other mechanisms that promote MCU-complex activation have also been proposed. Zaglia and her colleagues found that MCU expression in cardiomyocytes is regulated by microRNA-1 and MCU expression increases under pressure overload due to decreased microRNA-1, which promotes increased mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake [145]. Our group reported that a post-translational modification of MCU by tyrosine phosphorylation activates MCU complex under Gq protein-coupled receptor (GqPCR) stimulation [48], and Xie and his colleagues found that tyrosine phosphorylation of MCU in the heart is significantly elevated in a non-ischemic heart failure animal model. Ca2+/calmodulin--dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII)-dependent serine phosphorylation of MCU in adult ventricular myocytes was also proposed to increase MCU complex activity under pathophysiological conditions, such as ischemic/reperfusion injury, myocardial infarction, and neurohumoral injury [154]. However, serine phosphorylation levels of MCU were not detected in this study. In addition, the Kirichok’s group re-evaluated CaMKII-mediated regulation of MCU by performing mitoplast-patch experiments, but they were unable to reproduce the same results [155]. Therefore, it is still unclear whether CaMKII is capable of regulating MCU via direct phosphorylation. Lastly, the Madesh group showed that MCU can receive another type of posttranslational modification namely S-glutathionylation which activates the MCU-complex [156], but the existence of this post-translational modification and its role in cardiomyocytes have not yet been investigated.

7.2. Decreased mitochondrial Ca2+ and Cardiac Pathology

In addition to mitochondrial Ca2+ overload, several groups have proposed that decreased [Ca2+]m may also lead to oxidative stress and cell damage in the heart under pathological conditions. Growing evidences have shown increased [Na+]c in failing human hearts [157]. Similarly, failing guinea-pig hearts showed higher [Na+]c compared to non-failing hearts, and [Ca2+]m in failing hearts is reduced due to elevated [Na+]c that promotes the acceleration of Ca2+ efflux via NCLX [105, 158, 159]. Moreover, pharmacological inhibition of NCLX restored mitochondrial Ca2+ handling and decreased cellular oxidation in adult ventricular myocytes. In a type-1 diabetic mouse model, MCU expression, mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake induced by packing, and mitochondrial Ca2+ content were significantly reduced in adult ventricular myocytes [160, 161]. In addition, re-expression of MCU in diabetic hearts improves both impaired mitochondrial Ca2+ handling and metabolism. Possible mechanisms of how decreased [Ca2+]m promotes bioenergetic dysfunction and ROS elevation include: 1) inhibition of TCA activity followed by the decrease in the generation of the reduced form of Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) (see also section 6); and 2) impaired antioxidant capacity in the mitochondrial matrix due to the decreased NADPH [162] (Fig. 3).

8. Summary and Concluding Remarks

Recent discoveries regarding the molecular identity of mitochondrial Ca2+ influx/efflux mechanisms have placed mitochondrial Ca2+ transport at center stage in studies of cellular regulation. Over the last several years, multiple groups have taken advantage of newly available molecular information about these proteins and have applied genetic tools to delineate the precise mechanisms for regulating mitochondrial Ca2+ handling and its contribution to cellular Ca2+ homeostasis (i.e., excitation-contraction coupling) and energy metabolism (i.e., excitation-metabolism coupling) in the normal heart. In addition, mitochondrial Ca2+ has been proposed as one of the most crucial secondary messengers in controlling a cardiomyocyte’s life and death. As summarized in this review, there has been substantial progress in understanding the detailed molecular mechanisms of how altered mitochondrial Ca2+ handling promotes cardiac dysfunction, thanks to recent studies using transgenic mice and cardiac disease animal models. However, in human hearts, it is still unclear whether altered expressions of the components of the MCU complex and impaired mitochondrial Ca2+ handling are a reflection of the overall impairment of mitochondrial function at the end stage of the disease, or its pathogenesis. Quantitative measurements of the basal [Ca2+]m, kinetics of mitochondrial Ca2+ flux, and mitochondrial ATP production on a beat-to-beat-basis in adult ventricular myocytes from large animals, human adult ventricular myocytes and/or human induced pluripotent stem cells-derived cardiomyocytes may help resolve the questions that remain.

Funding & Acknowledgements

J.L.C. and S.M.A. were supported by the Brown University Karen T. Romer Undergraduate Teaching and Research Awards (UTRA). B.S.J was supported by NIH/NIGMS U54GM115677 and American Heart Association (AHA) 18CDA34110091. J.O-U. was supported by NIH/NHLBI R01HL136757, NIH/NIGMS P30GM1114750, AHA 16SDG27260248, Rhode Island Foundation No. 20164376 Medical Research Grant, American Physiological Society (APS) 2017 Shih-Chun Wang Young Investigator Award.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Kamer KJ and Mootha VK, Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 16 (2015) 545–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Mammucari C, Raffaello A, Vecellio Reane D, Gherardi G, De Mario A, Rizzuto R, Pflugers Arch (2018) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [3].Dedkova EN and Blatter LA, J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol 58 (2013) 125–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Foskett JK and Philipson B, J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol 78 (2015) 3–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Liu JC, Parks RJ, Liu J, Stares J, Rovira II, Murphy E, Finkel T, Adv. Exp. Med. Biol 982 (2017) 49–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].DELUCA HF and ENGSTROM GW, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 47 (1961) 1744–1750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].VASINGTON FD and MURPHY JV, J. Biol. Chem 237 (1962) 2670–2677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Paillard M, Csordas G, Szanda G, Golenar T, Debattisti V, Bartok A, Wang N, Moffat C, Seifert EL, Spat A, Hajnoczky G, Cell. Rep 18 (2017) 2291–2300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Kwong JQ, Lu X, Correll RN, Schwanekamp JA, Vagnozzi RJ, Sargent MA, York AJ, Zhang J, Bers DM, Molkentin JD, Cell. Rep 12 (2015) 15–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Tomar D, Dong Z, Shanmughapriya S, Koch DA, Thomas T, Hoffman NE, Timbalia SA, Goldman SJ, Breves SL, Corbally DP, Nemani N, Fairweather JP, Cutri AR, Zhang X, Song J, Jana F, Huang J, Barrero C, Rabinowitz JE, Luongo TS, Schumacher SM, Rockman ME, Dietrich A, Merali S, Caplan J, Stathopulos P, Ahima RS, Cheung JY, Houser SR, Koch WJ, Patel V, Gohil VM, Elrod JW, Rajan S, Madesh M, Cell. Rep 15 (2016) 1673–1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Luongo TS, Lambert JP, Yuan A, Zhang X, Gross P, Song J, Shanmughapriya S, Gao E, Jain M, Houser SR, Koch WJ, Cheung JY, Madesh M, Elrod JW, Cell. Rep 12 (2015) 23–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Pan X, Liu J, Nguyen T, Liu C, Sun J, Teng Y, Fergusson MM, Rovira II, Allen M, Springer DA, Aponte AM, Gucek M, Balaban RS, Murphy E, Finkel T, Nat. Cell Biol 15 (2013) 1464–1472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Bick AG, Wakimoto H, Kamer KJ, Sancak Y, Goldberger O, Axelsson A, DeLaughter DM, Gorham JM, Mootha VK, Seidman JG, Seidman CE, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 114 (2017) E9096–E9104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Drago I, De Stefani D, Rizzuto R, Pozzan T, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 109 (2012) 12986–12991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Rasmussen TP, Wu Y, Joiner ML, Koval OM, Wilson NR, Luczak ED, Wang Q, Chen B, Gao Z, Zhu Z, Wagner BA, Soto J, McCormick ML, Kutschke W, Weiss RM, Yu L, Boudreau RL, Abel ED, Zhan F, Spitz DR, Buettner GR, Song LS, Zingman LV, Anderson ME, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 112 (2015) 9129–9134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Wu Y, Rasmussen TP, Koval OM, Joiner ML, Hall DD, Chen B, Luczak ED, Wang Q, Rokita AG, Wehrens XH, Song LS, Anderson ME, Nat. Commun 6 (2015) 6081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Luongo TS, Lambert JP, Gross P, Nwokedi M, Lombardi AA, Shanmughapriya S, Carpenter AC, Kolmetzky D, Gao E, van Berlo JH, Tsai EJ, Molkentin JD, Chen X, Madesh M, Houser SR, Elrod JW, Nature 545 (2017) 93–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Yu SB and Pekkurnaz G, J. Mol. Biol 430 (2018) 3922–3941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Bers DM, Nature 415 (2002) 198–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Shiels HA and White E, J. Exp. Biol 211 (2008) 2005–2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Williams GS, Boyman L, Lederer WJ, J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol 78 (2015) 35–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Ong SB, Hall AR, Hausenloy DJ, Antioxid. Redox Signal 19 (2013) 400–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Lesnefsky EJ, Moghaddas S, Tandler B, Kerner J, Hoppel CL, J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol 33 (2001) 1065–1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Hollander JM, Thapa D, Shepherd DL, Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol 307 (2014) H1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Holmuhamedov EL, Oberlin A, Short K, Terzic A, Jahangir A, PLoS One 7 (2012) e44667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Glancy B, Hartnell LM, Combs CA, Femnou A, Sun J, Murphy E, Subramaniam S, Balaban RS, Cell. Rep 19 (2017) 487–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Belmonte S and Morad M, J. Physiol 586 (2008) 1379–1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Haviland S, Cleemann L, Kettlewell S, Smith GL, Morad M, Cell Calcium 56 (2014) 133–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Andrienko TN, Picht E, Bers DM, J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol 46 (2009) 1027–1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Mikoshiba K, Biochem. Soc. Symp (74):9–22. doi (2007) 9–22. [DOI] [PubMed]

- [31].Poindexter BJ, Smith JR, Buja LM, Bick RJ, Cell Calcium 30 (2001) 373–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Rizzuto R, Pinton P, Carrington W, Fay FS, Fogarty KE, Lifshitz LM, Tuft RA, Pozzan T, Science 280 (1998) 1763–1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Szabadkai G, Simoni AM, Chami M, Wieckowski MR, Youle RJ, Rizzuto R, Mol. Cell 16 (2004) 59–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Subedi KP, Kim JC, Kang M, Son MJ, Kim YS, Woo SH, Cell Calcium 49 (2011) 136–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Lu X, Ginsburg KS, Kettlewell S, Bossuyt J, Smith GL, Bers DM, Circ. Res (2012) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [36].De La Fuente S, Fernandez-Sanz C, Vail C, Agra EJ, Holmstrom K, Sun J, Mishra J, Williams D, Finkel T, Murphy E, Joseph SK, Sheu SS, Csordas G, J. Biol. Chem 291 (2016) 23343–23362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Blatter LA, J. Gen. Physiol 149 (2017) 857–865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].De Stefani D, Raffaello A, Teardo E, Szabo I, Rizzuto R, Nature 476 (2011) 336–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Baughman JM, Perocchi F, Girgis HS, Plovanich M, Belcher-Timme CA, Sancak Y, Bao XR, Strittmatter L, Goldberger O, Bogorad RL, Koteliansky V, Mootha VK, Nature 476 (2011) 341–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Lee SK, Shanmughapriya S, Mok MCY, Dong Z, Tomar D, Carvalho E, Rajan S, Junop MS, Madesh M, Stathopulos PB, Cell. Chem. Biol 23 (2016) 1157–1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Raffaello A, De Stefani D, Sabbadin D, Teardo E, Merli G, Picard A, Checchetto V, Moro S, Szabo I, Rizzuto R, EMBO J 32 (2013) 2362–2376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Oxenoid K, Dong Y, Cao C, Cui T, Sancak Y, Markhard AL, Grabarek Z, Kong L, Liu Z, Ouyang B, Cong Y, Mootha VK, Chou JJ, Nature 533 (2016) 269–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Baradaran R, Wang C, Siliciano AF, Long SB, Nature 559 (2018) 580–584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Nguyen NX, Armache JP, Lee C, Yang Y, Zeng W, Mootha VK, Cheng Y, Bai XC, Jiang Y, Nature 559 (2018) 570–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Yoo J, Wu M, Yin Y, Herzik MA Jr, Lander GC, Lee SY, Science 361 (2018) 506–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Fan C, Fan M, Orlando BJ, Fastman NM, Zhang J, Xu Y, Chambers MG, Xu X, Perry K, Liao M, Feng L, Nature 559 (2018) 575–579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Sancak Y, Markhard AL, Kitami T, Kovacs-Bogdan E, Kamer KJ, Udeshi ND, Carr SA, Chaudhuri D, Clapham DE, Li AA, Calvo SE, Goldberger O, Mootha VK, Science 342 (2013) 1379–1382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].O-Uchi J, Jhun BS, Xu S, Hurst S, Raffaello A, Liu X, Yi B, Zhang H, Gross P, Mishra J, Ainbinder A, Kettlewell S, Smith GL, Dirksen RT, Wang W, Rizzuto R, Sheu SS, Antioxid. Redox Signal 21 (2014) 863–879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Fieni F and Kirichok Y, J. Gen. Physiol (2011) 56A. [Google Scholar]

- [50].Kirichok Y, Krapivinsky G, Clapham DE, Nature 427 (2004) 360–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Perocchi F, Gohil VM, Girgis HS, Bao XR, McCombs JE, Palmer AE, Mootha VK, Nature 467 (2010) 291–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Plovanich M, Bogorad RL, Sancak Y, Kamer KJ, Strittmatter L, Li AA, Girgis HS, Kuchimanchi S, De Groot J, Speciner L, Taneja N, Oshea J, Koteliansky V, Mootha VK, PLoS One 8 (2013) e55785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Patron M, Granatiero V, Espino J, Rizzuto R, De Stefani D, Cell Death Differ (2018) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [54].Mallilankaraman K, Cardenas C, Doonan PJ, Chandramoorthy HC, Irrinki KM, Golenar T, Csordas G, Madireddi P, Yang J, Muller M, Miller R, Kolesar JE, Molgo J, Kaufman B, Hajnoczky G, Foskett JK, Madesh M, Nat. Cell Biol 14 (2012) 1336–1343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]