Abstract

Introduction:

Tradeoffs exist between efforts to increase influenza vaccine uptake, including early season vaccination, and potential decreased vaccine effectiveness if protection wanes during influenza season. U.S. older adults increasingly receive vaccination before October. Influenza illness peaks vary from December to April.

Methods:

A Markov model compared influenza likelihood in older adults with: (1) status quo vaccination (August–May) to maximize vaccine uptake, or (2) vaccination compressed to October–May (to decrease waning vaccine effectiveness impact). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data were used for influenza incidence and vaccination parameters. Prior analyses showed absolute vaccine effectiveness decreased by 6%–11% per month, favoring later season vaccination. However, compressed vaccination could decrease overall vaccine uptake. Influenza incidence was based on average monthly incidence with earlier and later peaks also examined. Influenza strain distributions from two seasons were modeled in separate scenarios. Sensitivity analyses were performed to test result robustness. Data were collected and analyzed in 2018.

Results:

Compressed vaccination would avert ≥11,400 influenza cases in older adults during a typical season if it does not decrease vaccine uptake. However, if compressed vaccination decreases vaccine uptake or there is an early season influenza peak, more influenza can result. In probabilistic sensitivity analyses, compressed vaccination was never favored if it decreased absolute vaccine uptake by >5.5% in any scenario; when influenza peaked early, status quo vaccination was favored.

Conclusions:

Compressed vaccination could decrease waning vaccine effectiveness and decrease influenza cases in older adults. However, this positive effect is negated when early season influenza peaks occur and diminished by decreased vaccine uptake that could occur with shortening the vaccination season.

INTRODUCTION

Until 2007, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommended that the optimal time to receive influenza vaccination was in October or November to ensure sufficient immune response and protection from infection among older and high-risk adults, the primary targets of vaccination at that time.1 This recommendation was justifiable, because: (1) influenza virus circulation does not typically occur before the first of the year, (2) influenza virus may circulate in May or June, and (3) immunity could wane toward the end of the season, especially among those with compromised immune systems. However, references to optimal vaccination timing were removed from CDC influenza vaccination recommendations in 2007.2 At that point, CDC stated that an optimal vaccination time could not be determined and that influenza vaccination should be offered soon after the vaccine becomes available to avoid missed opportunities for vaccination during routine healthcare visits or hospitalizations.2 Since 2007, recommended groups for vaccination expanded and, in 2010,3 influenza vaccination was universally recommended for all individuals aged more than 6 months. These changes dramatically increased the number of individuals needing to be vaccinated before influenza circulation, “highlighting the importance of making influenza vaccination readily accessible”3 to all those seeking it. Early vaccination is one means to this goal.

A published CDC analysis, examining the 2011–2012 through 2014–2015 influenza seasons, estimated that absolute influenza vaccine effectiveness (VE) may decrease up to 11% per month, with variation based on influenza strain.4 This waning of VE could put individuals vaccinated early in influenza seasons at greater risk of illness, especially in years when influenza peaks late. Thus, tradeoffs exist between efforts to increase influenza vaccine uptake through early season vaccination and potential decreased VE because of waning protection over an influenza season. This situation is likely to be most threatening for older adults and those with high-risk conditions. In recent years, the percentage of older Americans aged 65 years or older who received the influenza vaccine before October has steadily increased, reaching 13.5% (or 20.7% of people vaccinated in this age group) during the 2016–2017 influenza vaccination season,5 which is greater than early vaccination rates seen in younger age groups.

This analysis examines, in individuals aged 65 years or more, tradeoffs between mitigating possible waning through a compressed vaccination schedule, where no vaccine is received before October, and possible decreased population vaccine uptake that could occur if the vaccination season is shortened.

METHODS

Study Sample

A CDC analysis, examining intra-season waning of influenza vaccine protection from the 2011– 2012 through 2014–2015 influenza seasons, found that absolute VE decreased by 6%–11% per month, with variation based on strain; no differences in waning were detected across age groups.4 Other studies report similar intra-season influenza vaccination waning effects, but with greater effects in the older adults and less waning in younger adults.6–8 In this analysis, strain-specific waning values from the CDC analysis were used,4 varying those values over ranges observed in all studies (Table 1). In the model, these strain-specific waning effects were separately applied to overall season influenza strain distributions from two U.S. influenza seasons, 2013–2014, during which the predominant A strain was A/H1N1 (relative likelihood among all U.S. influenza cases: A/H1N1 57.1%, A/H3N2 13.7%, B 29.2%), and 2014–2015 during which the predominant A strain was A/H3N2 (A/H1N1 0.2%, A/H3N2 83.2%, B 16.6%). Older adults could receive either standard dose trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine or high dose trivalent vaccine, based on the observed relative likelihood of receiving each vaccine during the 2016–2017 season (personal communication, David Greenberg, 2018).

Table 1.

Model Parameter Values

| Variable | Range | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base, % | Low, % | High, % | Reference | |

| Maximum vaccine effectiveness (VE) vs | ||||

| A/H1N1 | 80 | 55 | 95 | 4 |

| A/H3N2 | 35 | 5 | 55 | 4 |

| B | 59 | 20 | 80 | 4 |

| Absolute decrease in VE per month | ||||

| A/H1N1 | 8.5 | 6 | 11 | 4 |

| A/H3N2 | 7 | 2 | 16 | 4 |

| B | 7 | 2 | 16 | 4 |

| Seasonal likelihood of vaccination | 65.3 | 60 | 70 | 5 |

| Relative likelihood of high dose vaccine receipt | 60 | 30 | 90 | Estimatea |

| Absolute decrease in seasonal vaccination with compressed vaccination | 0 | 0 | 7 | Estimate |

| Seasonal likelihood of influenza | 5.9 | 4 | 9 | 10 |

| Influenza illness | ||||

| Case-hospitalization | 4.2 | 1.9 | 7.3 | 10 |

| Case-fatality | 1.17 | 0.04 | 2.08 | 10 |

Personal communication, David Greenberg, 2018.

Measures

For those receiving the high dose influenza vaccine, it was assumed that the clinical trial observed relative increase in VE with this vaccine, 24.2% (95% CI=9.7%, 36.5%),9 applied to all influenza strains. The degree of waning that may occur with high dose vaccine is unclear. To account for this uncertainty, differing waning scenarios were modeled where high dose VE declined based on either absolute or relative strain-specific declines in VE observed with standard dose vaccines from the CDC analysis.

In all scenarios, the seasonal influenza attack rate was assumed to be 5.9%.10 For each seasonal influenza strain distribution and high dose vaccine waning scenario (a total of four scenarios), monthly attack rate distributions (Appendix Table 2) were examined based on: an average influenza case peak occurring in February (base case), an early peak in December, and a late peak in April. In the base case analysis, it was assumed that compressed vaccination did not decrease overall vaccination uptake in older adults, which was 65.3% in 2016–2017.5 Overall uptake was varied in sensitivity analyses. For each scenario, results were obtained using the base case values for parameters listed in Table 1. Probabilistic sensitivity analyses, simultaneously varying parameters over distributions 5,000 times, were then run for each scenario. Beta distributions were used for all probabilities and likelihoods, fitted to approximate the listed ranges. In separate sensitivity analyses, Northern Hemisphere influenza seasonal peak likelihoods weighted to produce an average influenza incidence distribution was examined, as was the effect of altering influenza incidence curve distributions, with higher than average influenza circulation earlier in the season while retaining a February peak (Appendix Table 2, fourth column).

Statistical Analysis

A Markov decision analysis model was used to compare the likelihood of influenza and influenza-related outcomes (incidence, hospitalization, and death) in two influenza vaccination strategies: (1) status quo, where vaccination occurs in adults aged ≥65 years (termed older adults hereafter) based on monthly uptake observed during the 2016–2017 influenza season (to maximize vaccine uptake), and (2) vaccination compressed to October through May (to decrease the impact of waning VE; Appendix Table 1). The Markov cycle length was 1 month over a 10-month time horizon (a single influenza season). Monthly vaccine uptake of U.S. older adults during 2016–2017 was obtained from the CDC FluVaxView website.5 Data were collected and analyzed in 2018. The model was built using TreeAge Pro 2017 software, version 2.0.

RESULTS

During an average influenza season (February peak), assuming no deceased vaccine uptake with compressed vaccination (a best case scenario for compressed vaccination) and using 2014–2015 influenza season strain distributions, delaying vaccination to October or later resulted in a seasonal influenza case incidence of 5.06%, whereas status quo vaccination had an incidence of 5.09%, or a difference of 11,423 cases among the 49.2 million people aged ≥65 years in the U.S.

In this scenario, the model predicts 481 fewer hospitalizations and 134 fewer deaths with a compressed vaccination schedule. During the 2013–2014 season, compressed vaccination resulted in 17,503 fewer cases, 737 fewer hospitalizations, and 205 fewer deaths. Public health results for early (December) and late (April) influenza illness peaks when assuming no decrease in overall vaccine uptake are shown in Table 2. In either season, an early influenza peak results in more influenza cases with compressed vaccination compared with the status quo in this best-case scenario for compressed vaccination.

Table 2.

Public Health Results Under Differing Influenza Incidence Peak and Strain Assumptions in the U.S. Population Aged ≥65 Years

| Variable | Influenza incidence | Reduction (increase) in | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compressed, % |

Status quo, % |

Cases, N |

Hospitalizations, N |

Deaths, N |

|

| Typical peak – February | |||||

| 2013–2014a | 4.14 | 4.17 | 17,503 | 737 | 205 |

| 2014–2015b | 5.06 | 5.09 | 11,423 | 481 | 134 |

| Early peak – December | |||||

| 2013–2014 | 4.36 | 4.34 | (9,216) | (108) | (388) |

| 2014–2015 | 5.10 | 5.10 | (1,504) | (18) | (63) |

| Late peak – April | |||||

| 2013–2014 | 4.15 | 4.20 | 22,062 | 929 | 258 |

| 2014–2015 | 5.14 | 5.16 | 11,480 | 483 | 134 |

H1N1 predominant.

H3N2 predominant.

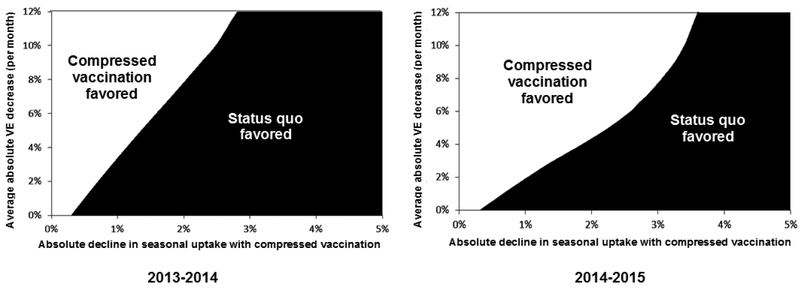

However, it is unclear what effects compressed vaccination might have on overall influenza vaccine uptake. If compressed vaccination results in decreased seasonal influenza vaccine uptake, more influenza can result regardless of influenza strain distribution or waning VE assumptions. For example, using 2014–2015 season influenza distributions, more influenza cases occur with compressed vaccination if overall uptake decreases by ≥3.5 percentage points (i.e., decreases overall vaccine uptake from 65.3% to ≤61.8%). Using the 2013–2014 season distributions, more influenza occurs if overall uptake decreases ≥2.5 percentage points. These effects are depicted as areas in Figure 1 where strategies are favored, based on influenza cases avoided, when simultaneously varying VE waning and declines in seasonal vaccine uptake. Results are similarly sensitive to variation in vaccine waning assumptions and to differences in influenza case seasonal peaks.

Figure 1.

Two-way sensitivity analysis (February influenza illness peak).

Notes: Areas where influenza vaccination strategies are favored when simultaneously varying average absolute vaccination effectiveness waning (y-axis) and absolute declines in seasonal influenza vaccine uptake (x-axis).

For the probabilistic sensitivity analyses, where all parameters were varied over distributions simultaneously, results for the four influenza strain and high dose vaccine waning scenarios are summarized, for each seasonal peak assumption, in Table 3. During seasons with early peaks, compressed vaccination was rarely favored and was never favored in all four strain distribution and VE scenarios if compressed vaccination resulted in an absolute decrease in overall seasonal influenza vaccine uptake of >1.6% (i.e., a decrease from the baseline uptake of 65.3% to <63.7%). For average or late illness peaks, compressed vaccination was always favored in all scenarios if overall seasonal uptake decreased by <0.97 or 1.3 percentage points respectively; compressed vaccination was never favored if it decreased uptake by >5.1 or >5.6 percentage points.

Table 3.

Probabilistic Sensitivity Analysis Results. Absolute Declines in Seasonal Vaccine Uptake Where a Compressed Strategy Is Always or Never Favored Among Differing Scenarios in Adults Aged ≥65 Years

| Season | Absolute declines in seasonal influenza vaccine uptakea | |

|---|---|---|

| Compressed always favored, % | Compressed never favored, % | |

| Early peak (December) | <0.001 | >0.01 |

| Average peak (February) | <0.97 | >5.1 |

| Late peak (April) | <1.3 | >5.6 |

When compressed vaccination strategy is in place.

In a separate analysis, using historical Northern Hemisphere data on seasonal influenza peaks, where one in four seasons had early peaks (December or before) and another one in four had late peaks (after late February),15 results were weighted based on influenza peak likelihood timing to assess, on average, the potential effects of compressed vaccination. Using 2013–2014 influenza strain data, with averaged peaks, compressed vaccination resulted in 11,952 fewer influenza cases compared with the status quo, whereas use of 2014–2015 data resulted in 8,198 more cases with compressed vaccination. In another sensitivity analysis, detailed in Appendix Table 3, the shape of the influenza incidence curve was altered to model greater than average incidence starting in November but retaining a February peak incidence. This analysis resulted in both the compressed and status quo strategies preventing more influenza than when an average February distribution occurred (because of closer proximity of vaccination month and influenza attack distributions), with compressed vaccination being more favored in terms of influenza cases and complications prevented (because of its closer proximity to influenza attack rates than status quo vaccination).

DISCUSSION

Moderate influenza VE in recent years11–14 and increasing evidence of waning VE before the end of influenza circulation4 could leave people vaccinated early in influenza seasons unprotected and hence, may require a change in influenza vaccine policy. The current recommendation to begin vaccination when influenza vaccine becomes available maximizes opportunities for providers to vaccinate. In this analysis, it was found that compressing the vaccination season into fewer months (i.e., not starting before October), resulted in fewer influenza cases in adults aged 65 years and older under most scenarios when no loss of overall vaccine uptake occurred, excepting influenza seasons with early peaks. However, if vaccine uptake decreases when influenza vaccination season is compressed, more influenza cases may occur despite gains in VE through reduced intra-season waning effects. When typical late January to early February peaks in influenza activity were modeled or when peaks occurred later in the season, compressed vaccination led to fewer influenza cases in all modeled serotype distribution and high dose vaccine waning scenarios if overall absolute vaccine uptake decreased by less than approximately 1%. Possible advantages of compressed vaccination were not seen when early peaks in influenza were modeled. However, in all situations, compressed vaccination was never favored if it decreased absolute vaccine uptake by more than 5.6%.

The impact of removing early season influenza vaccination and delay of vaccination until later in the season is unclear. This analysis points out boundaries that vaccination policymakers might find useful when considering how to decrease the potential effects of waning intra-season vaccination protection. Addressing waning through delaying the start of vaccination has a relatively narrow window where such a policy would be consistently favorable. Delayed vaccination would only be advantageous in seasons without an early peak and if a delayed schedule does not decrease uptake by 1 percentage point or more. Historical analyses of influenza season peaks in temperate Northern Hemisphere regions suggest that early influenza season peaks (December or before) occur in approximately one in four influenza seasons.15 Thus, a compressed vaccination strategy would be expected to result in more influenza cases in older adults in about 25% of influenza seasons, even if no decreases in vaccine uptake are assumed with compressed vaccination. Weighting influenza illness peak likelihood to develop an average peak resulted in differing favorability of compressed vaccination depending on influenza strain distributions. Thus, uncertainty regarding when influenza peaks may occur and what influenza strains might circulate prevent definitive conclusions regarding the favorability of compressed vaccination. Altering the shape of influenza incidence curves so that more influenza cases occur early in a season with an average (February) peak will also favor compressed vaccination, as long as those early additional cases occur after compressed vaccination has begun.

There are open questions regarding whether moving to a compressed vaccination schedule should be considered, given relatively modest and uncertain benefits and, if it should, whether compressed vaccination could be practically implemented. Shortening the vaccination season decreases currently available opportunities for older adults to be vaccinated during early season routine checkups and medical appointments, and requires patients, practices, and other medical infrastructure to make arrangements to ensure that vaccination can occur later. Older adults could “fall through the cracks” in those arrangements, leading to decreased vaccine uptake that could minimize or eliminate the potential benefits of compressing the vaccination season. However, older adults at greatest risk from influenza and its complications tend to have pre-existing conditions for which they are under care, so opportunities to immunize them may be more frequent, and practices caring for them likely feel a strong responsibility to recall or remind them so that immunization occurs. Additionally, policy changes of this magnitude require substantial organizational and educational efforts at all levels of the public health and medical care systems; on its own, this required work could make compressed vaccination impractical and inefficient given its potential outcomes. On the other hand, historical CDC guidance on influenza vaccination campaigns has emphasized mid-October or later vaccination, showing that the organization needed for compressed vaccination campaigns is possible.1 The CDC now discusses these trade-offs, stating, “Community vaccination programs should balance maximizing likelihood of persistence of vaccine-induced protection through the season with avoiding missed opportunities to vaccinate or vaccinating after onset of influenza circulation occurs.”16 It is unclear how often vaccination in older adults occurs during healthcare visits for other reasons compared with immunization occurring when it is deliberately sought; further research in this area could inform influenza vaccination policymaking.

Limitations

Issues with waning vaccine-induced protection from influenza may already have been addressed through high dose influenza vaccine in older adults, with 60%–66% of them receiving this vaccine in recent years (personal communication, David Greenberg, 2018). However, the degree of waning associated with high dose influenza vaccines is unknown at this point, presenting a limitation in this analysis. Two scenarios for high dose vaccine waning were examined. The first used strain-specific absolute decreases in effectiveness observed with standard dose vaccines and applied these decreases to the higher baseline VE levels observed with high dose vaccine use. The other used relative strain-specific decreases in VE observed with standard dose vaccine (i.e., monthly decrease in VE divided by baseline standard dose VE) and applied those same relative decreases on baseline high dose VE. These conclusions hold with either scenario. If assumptions overestimated high dose VE declines, then compressed vaccination becomes more unfavorable. In addition, the modeled cohorts did not account for potential heterogeneity within the cohort in vaccine received, vaccination timing, or influenza morbidity and mortality based on increasing age.

This analysis has other limitations. It did not consider other newer influenza vaccination options, the recombinant and adjuvanted vaccines, because waning VE data for them are not yet available. It also did not consider the cost effectiveness of differing vaccination strategies. High dose vaccine is considerably more expensive than the standard dose vaccine but has been shown elsewhere to be economically reasonable compared with the standard dose vaccine in older adults.17,18 Moreover, this analysis did not consider other costs that could occur with compressed vaccination: costs of implementing, publicizing, and maintaining this policy change; and potential costs to patients and practices to ensure that vaccination occurs if early vaccination is not available. If compressed vaccination is contemplated, further research on the cost aspects of this policy will be necessary. Finally, this analysis did not consider indirect (herd immunity) effects of vaccination in the model. Some of the protection from influenza afforded to older adults is derived from herd immunity effects from the vaccination of other age groups, particularly children. Compressed vaccination in younger age groups, where early vaccination occurs less often than in older groups, likely would not substantially change indirect effects in older adults resulting from vaccination of younger people. However, given the complexity of predicting these effects, it is unclear how consideration of herd immunity might affect this analysis, which concentrates on direct vaccination effects in older adults.

CONCLUSIONS

This analysis found that deferring influenza vaccination until at least October could decrease the effects of waning VE and improve protection afforded by vaccination if a shortened vaccination season minimally decreased overall vaccine uptake. However, this potential positive effect of a compressed vaccination season may be negated by early season influenza peaks or by substantial decreases in overall vaccine uptake that could occur if the vaccination season was shortened.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The research presented in this paper is that of the authors and does not reflect the official policy of NIH.

Supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (R01 GM111121), which had no role in study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing the report; and the decision to submit the report for publication.

Kenneth Smith, Glenson France, and Angela Wateska performed the analysis and drafted the manuscript. The remaining authors contributed to the conception and design of the analysis, the interpretation of data, critically appraised and edited the manuscript, and gave final approval of the version to be published.

Richard Zimmerman has no active research grants from industry but within 3 years had grants from Sanofi Pasteur, Pfizer Inc., and Merck & Co., Inc. Jonathan Raviotta has no active research grants from industry but within 3 years had grants from Pfizer Inc., and Merck & Co., Inc. Mary Patricia Nowalk has grant funding from Merck & Co., Inc. on an unrelated topic and within 3 years had received grant funding from Pfizer Inc. No other financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Smith NM, Bresee JS, Shay DK, Uyeki TM, Cox NJ, Strikas RA. Prevention and control of influenza: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR10):1–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fiore AE, Shay DK, Haber P, et al. Prevention and control of influenza: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2007. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2007;56(RR06):1–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fiore AE, Uyeki TM, Broder K, et al. Prevention and control of influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-8):1–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferdinands JM, Fry AM, Reynolds S, et al. Intraseason waning of influenza vaccine protection: evidence from the U.S. influenza vaccine effectiveness network, 2011–2012 through 2014–2015. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(5):544–550. 10.1093/cid/ciw816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.CDC. 2016–17. Influenza Season Vaccination Coverage Report. www.cdc.gov/flu/fluvaxview/reportshtml/reporti1617/reporti/index.html. Accessed November 21, 2018.

- 6.Belongia EA, Sundaram ME, McClure DL, Meece JK, Ferdinands J, VanWormer JJ. Waning vaccine protection against influenza A (H3N2) illness in children and older adults during a single season. Vaccine. 2015;33(1):246–251. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.06.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petrie JG, Ohmit SE, Truscon R, et al. Modest waning of influenza vaccine efficacy and antibody titers during the 2007–2008 influenza season. J Infect Dis. 2016;214(8):1142–1149. 10.1093/infdis/jiw105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Puig-Barberà J, Mira-Iglesias A, Tortajada-Girbés M, et al. Waning protection of influenza vaccination during four influenza seasons, 2011/2012 to 2014/2015. Vaccine. 2017;35(43):5799–5807. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DiazGranados CA, Dunning AJ, Kimmel M, et al. Efficacy of high-dose versus standard-dose influenza vaccine in older adults. New Engl J Med. 2014;371(7):635–645. 10.1056/NEJMoa1315727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Molinari N-AM, Ortega-Sanchez IR, Messonnier ML, et al. The annual impact of seasonal influenza in the U.S.: measuring disease burden and costs. Vaccine. 2007;25(27):5086–5096. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flannery B, Chung J, Belongia E, et al. Interim estimates of 2017–18 seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness – United States, February 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(6):180–185. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6706a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flannery B, Chung J, Thaker S, et al. Interim estimates of 2016–17 seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness—United States, February 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(6):167–171. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6606a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flannery B, Zimmerman RK, Gubareva LV, et al. Enhanced genetic characterization of influenza A(H3N2) viruses and vaccine effectiveness by genetic group, 2014–2015. J Infect Dis. 2016;214(7):1010–1019. 10.1093/infdis/jiw181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zimmerman RK, Nowalk MP, Chung J, et al. 2014–2015 influenza vaccine effectiveness in the United States by vaccine type. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(12):1564–1573. 10.1093/cid/ciw635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bloom-Feshbach K, Alonso WJ, Charu V, et al. Latitudinal variations in seasonal activity of influenza and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV): a global comparative review. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e54445 10.1371/journal.pone.0054445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grohskopf LA, Sokolow LZ, Broder KR, et al. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices–United States, 2017–18 influenza season. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2017;66(2):1–20. 10.15585/mmwr.rr6602a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raviotta JM, Smith KJ, DePasse J, et al. Cost-effectiveness and public health effect of influenza vaccine strategies for U.S. elderly adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(10):2126–2131. 10.1111/jgs.14323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raviotta JM, Smith KJ, DePasse J, et al. Reply to: estimating the full value of high-dose influenza vaccine. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(9):2111–2112. 10.1111/jgs.14976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.