Abstract

A Markovian Susceptible Infectious Recovered (SIR) model is considered for the spread of an epidemic on a configuration model network, in which susceptible individuals may take preventive measures by dropping edges to infectious neighbours. An effective degree formulation of the model is used in conjunction with the theory of density dependent population processes to obtain a law of large numbers and a functional central limit theorem for the epidemic as the population size , assuming that the degrees of individuals are bounded. A central limit theorem is conjectured for the final size of the epidemic. The results are obtained for both the Molloy–Reed (in which the degrees of individuals are deterministic) and Newman–Strogatz–Watts (in which the degrees of individuals are independent and identically distributed) versions of the configuration model. The two versions yield the same limiting deterministic model but the asymptotic variances in the central limit theorems are greater in the Newman–Strogatz–Watts version. The basic reproduction number and the process of susceptible individuals in the limiting deterministic model, for the model with dropping of edges, are the same as for a corresponding SIR model without dropping of edges but an increased recovery rate, though, when , the probability of a major outbreak is greater in the model with dropping of edges. The results are specialised to the model without dropping of edges to yield conjectured central limit theorems for the final size of Markovian SIR epidemics on configuration-model networks, and for the size of the giant components of those networks. The theory is illustrated by numerical studies, which demonstrate that the asymptotic approximations are good, even for moderate N.

Keywords: SIR epidemic, Configuration model, Social distancing, Density dependent population process, Effective degree, Final size

Introduction

In understanding the transmission dynamics in a population, one of the most important modelling components is the contact process. In this work we consider a form of self-initiated social distancing in response to an epidemic while at the same time taking into account the underlying contact network structure of the population. The resulting network is sometimes referred to as an adaptive network, e.g. Gross et al. (2006), Shaw and Schwartz (2008), Zanette and Risau-Gusmán (2008) and Tunc and Shaw (2014). Behavioural dynamics in infectious disease models can come in many different forms. Much of the literature that combines behavioural changes with network models uses agent-based simulations, as in the works cited above, although analytical advances have also been made (e.g. Britton et al. (2016) and Jacobsen et al. (2018)). Our work takes the model introduced in Britton et al. (2016) as its starting point. Britton et al. (2016) consider a broader class of models but restrict the analysis to the initial phase of the epidemic. In the current paper we analyse the time evolution and the final size of the epidemic. We model an SIR (Susceptible Infectious Recovered) infection on a configuration network that is static in the absence of infection. A susceptible individual breaks off its connection to an infectious neighbour upon learning of that neighbour’s infectious status. This occurs at a constant rate, independently per neighbour. One can think of this mechanism as being governed by infectious individuals informing their neighbours. Whereas infectious and recovered neighbours do not take any action upon being informed, susceptible neighbours want to avoid becoming infected and therefore cease contact with the infectious individual. We use the term ‘preventive dropping of edges’ to indicate this type of behaviour. Details of the model formulation are presented in Sect. 2.

To some extent, from the point of view of a susceptible neighbour of an infectious individual, it does not matter whether the infectious individual recovers or informs and dissolves the connection. Either way, it means that the susceptible neighbour can no longer acquire infection from this individual. In Sect. 5 we see that this is true when dealing with the asymptotic mean (deterministic) process, in that the number of susceptibles in the deterministic process for the model with dropping of edges coincides with that for the model without dropping of edges but with an increased recovery rate. In Sect. 8 we also see that this is not true for the stochastic process, in particular, the probability of a major outbreak differs (Theorem 8.1). Indeed, we cannot expect the two stochastic processes to coincide since informing neighbours happens independently of one another, while recovery affects all neighbours simultaneously.

In Sect. 3 we analyse the preventive dropping model throughout the epidemic outbreak, by using a so-called effective degree construction (cf. Ball and Neal 2008). Using such a construction, conditional on a major outbreak, by using techniques from Ethier and Kurtz (1986), we show under the assumption of bounded degrees that, as the population size N tends to infinity, the fractions of the population that are susceptible, infective and recovered satisfy a law of large numbers (LLN) over any finite time interval (more specifically that they converge almost surely to a limiting deterministic process), together with an associated functional central limit theorem (CLT) which describes fluctuations of the stochastic epidemic process about the limiting deterministic epidemic.

The population consists of N individuals that make up a network, which is formed using the configuaration model. The configuration model was introduced by Bollobás (1980), see Bollobás (2001) for further references, and comes in two versions: either (i) the degrees of individuals are prescribed deterministically, the Molloy–Reed (MR) random graph (Molloy and Reed 1995), or (ii) the degrees of individuals are assumed to be independent and identically distributed, the Newman–Strogatz–Watts (NSW) random graph (Newman et al. 2001). We treat both the MR and the NSW versions. If the limiting distribution of the degrees in the MR construction agrees with the degree distribution of the NSW random graph, the two versions give the same LLN, as we show in Theorem 3.1. However, the two versions differ regarding the variance in the CLTs, since (for finite N) there is greater variability in the degrees of the individuals in the NSW model than in the MR model. The functional CLT for the epidemic on an MR random graph is given in Theorem 3.2. By making a random time transformation, in Sect. 4, we conjecture a CLT for the final outcome of the epidemic on an MR random graph; see Conjecture 4.1. Corresponding results for the epidemic on an NSW random graph are discussed in Sect. 7; see Theorem 7.2 and Conjecture 7.1. To prove the latter results we require a version of the functional CLT in Ethier and Kurtz (1986) which allows for asymptotically random initial conditions; see Theorem 7.1.

The asymptotic variance–covariance matrix in the CLT in Proposition 4.1 is far from explicit. In order to obtain a nearly-explicit expression for the limiting variance of the final size, it is necessary to solve (partially) a time-transformed limiting deterministic process, which is more amenable to analysis than the corresponding deterministic process in real time. This is done in Sect. 5.1 and linked to the solution of the real-time process in Sect. 5.1.2. These results are used in Sects. 6 and 7 to obtain almost fully explicit expressions for the asymptotic variance of the final size of epidemics on MR and NSW random graphs, respectively, see Proposition 6.1 and Conjecture 7.1. In Sect. 5.2, we connect our analysis of the deterministic effective degree model to results derived using other deterministic approaches (cf. Volz (2008), Leung and Diekmann (2016) for related models), leading to a simple proof that the process of susceptible individuals in the limiting deterministic model for the epidemic with preventive dropping of edges is identical to that in the corresponding deterministic model without dropping of edges but with an increased recovery rate (see Remark 5.3).

Note that in the absence of behaviour change, we are in the setting of a Markov SIR epidemic on a configuration model network, which we consider in Sect. 9. This model has been analysed in several papers, e.g. Newman (2002), Kenah and Robins (2007), Lindquist et al. (2011) and Miller (2011). Our results further improve understanding of this well-studied model, particularly in terms of the asymptotic variance of the final size in Conjecture 9.1. Moreover, our work yields conjectured CLTs for the size of the giant component in MR and NSW configuration model random graphs; see Conjecture 9.2.

In Sect. 10, we illustrate our results with some numerical studies. In particular, we demonstrate that the asymptotic results generally give a good approximation for moderate population sizes, investigate the impact of the dropping of edges on properties of epidemics and do some comparison of the behaviour of the epidemic on MR and NSW type random graphs. Some brief concluding comments are given in Sect. 11.

Finally, we would like to make a note on the structure of the paper. Clearly, this paper does not readily lend itself to a quick superficial read, owing to its length and some of the technicalities and details involved in obtaining our results. However, we have tried to help the reader by formulating our main results in terms of propositions, theorems and well-motivated conjectures. The more technical aspects can be found in the appendices for the interested reader, which consequently constitute a significant part of the paper.

The stochastic SIR network epidemic model with preventive dropping

In this section we define the stochastic SIR network epidemic model with preventive dropping. This model is a special case of the network epidemic model with preventive rewiring defined in Britton et al. (2016), namely where there is no latent period and where the fraction of dropped edges that are replaced by new edges is set to zero.

The population consists of N individuals, labelled , that make up a network. The network is formed using the configuration model, which, as described in Sect. 1, comes in two versions, namely MR and NSW random graphs. Let D be a random variable which describes the degree of a typical individual and . Let and denote the mean and variance of D, respectively, both of which are assumed to be finite.

-

(i)

In the MR model, the degrees are prescribed. More specifically, for , let denote the degrees of the individuals when the population size is N. Note that these are deterministic. Let be the empirical distribution of , where the Kronecker delta is 1 if and 0 otherwise. It is assumed that .

-

(ii)

In the NSW model, the degrees of the N individuals are independent and identically distributed copies of D. A sequence of networks, indexed by N, may be constructed from a sequence of independent and identically distributed copies of D by using the first N random variables for the network on N individuals.

In both models the network is formed by attaching a number of stubs (i.e. half-edges) to each individual, according to its degree (so, for example, in the NSW model, stubs are attached to individual i, for ), and then pairing up these stubs uniformly at random to form the network. If is odd, there is a left-over stub, which is ignored. The network may have some ‘defects’, specifically self-loops and multiple edges between pairs of individuals, but provided , which we assume, such defects become sparse in the network as ; see Durrett (2007), Theorem 3.1.2.

A Markovian SIR epidemic is defined on the network of N individuals as follows. Each individual is at any point in time either susceptible, infective or recovered (and immune to further infection). An infective individual infects each of its susceptible neighbours at the points of independent Poisson processes, each having rate . An infectious individual recovers and becomes immune at rate (implying that the duration of the infectious period follows an exponential distribution having mean ). Finally, susceptible individuals that have infectious neighbours drop such connections, independently, at rate (an equivalent description to be used later is that the infective ‘warns’ its neighbours independently at rate , and warned susceptible individuals drop the corresponding edge). All infectious periods, infecting processes and edge-dropping processes are mutually independent. The epidemic is initiated at time by one or more individuals being infectious and all other individuals being susceptible. More precise initial conditions are given when they are required. The epidemic continues until there is no infectious individual. Then the epidemic stops and the result is that some of the individuals have been infected (and later recovered) and the rest of the population remains susceptible and hence have not been infected during the outbreak.

The parameters of the model are the degree distribution , including its mean and variance , the infection rate , the recovery rate and the dropping rate .

It was shown in Britton et al. (2016) that the basic reproduction number for the model is given by

| 2.1 |

see also Sect. 8. Note that the first factor in (2.1) is the probability that an infective infects a given susceptible neighbour before either the infective recovers or the neighbour drops its edge to that infective. The second factor is the expected number of susceptible neighbours for infected individuals during the early stages of an outbreak initiated by few infectives. Owing to the way the network is constructed, the degree of a typical neighbour of a typical individual has the size-biased distribution , , and hence mean . In the early stages of an outbreak, a typical infective has all susceptible neighbours except for one, namely its infector.

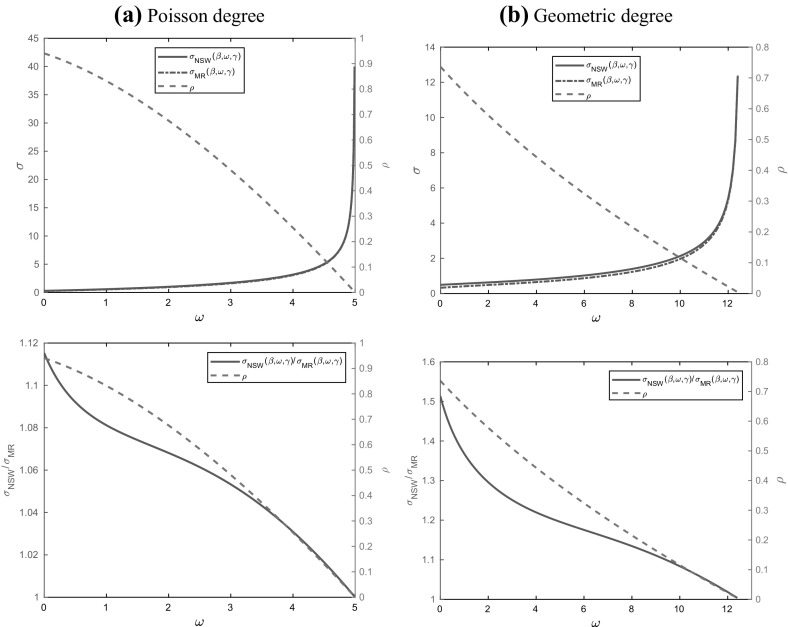

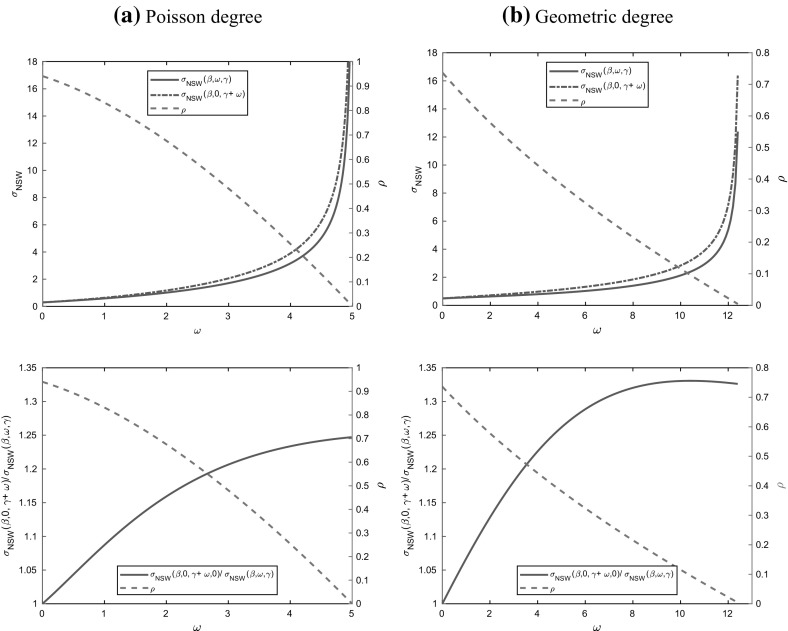

Note that for the dropping model is the same as for a Markovian SIR epidemic on a configuration model network without dropping of edges but with an increased recovery rate ; see also Remark 5.3 and Sect. 8, where we discuss this modified model with increased recovery rate and its relation to the dropping model. Furthermore, from (2.1) we find that is a monotonically decreasing function of , i.e. dropping edges always decreases the epidemic threshold parameter ; see also Fig. 5 in Sect. 10.4. For epidemics initiated by few infectives, this paper is concerned mainly with the case where , since only then is there a possibility for a major outbreak to take place.

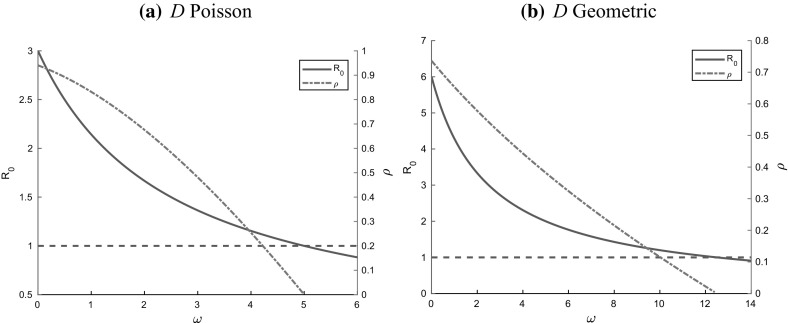

Fig. 5.

Plots of and showing the impact of increasing the dropping rate from zero. Other parameters are , , and a, b

Effective degree formulation

In this section we analyse the stochastic SIR network epidemic model with preventive dropping that is described in Sect. 2. We do so by extending the ‘effective degree’ construction of an SIR epidemic on a configuration model network, introduced in Ball and Neal (2008), to incorporate dropping of edges. This allows us to prove a LLN and a functional CLT for the epidemic process (Theorems 3.1 and 3.2). Our proofs rely on the results of Ethier and Kurtz (1986) (see also Kurtz (1970, 1971)), and we adopt mostly the notation used in their work for ease of reference.

In the effective degree formulation the network is constructed as the epidemic progresses. The process starts with some individuals infective and the remaining individuals susceptible, but with none of the stubs paired up. For , the effective degree of individual i is initially in the MR graph and in the NSW graph. Infected individuals behave in the following fashion. An infective, i say, transmits infection down its unpaired stubs at points of independent Poisson processes, each having rate . When i transmits infection down a stub, that stub is paired with a stub (attached to individual j, say) chosen uniformly at random from all other unpaired stubs to form an edge. If then the effective degrees of both i and j are reduced by 1, otherwise the effective degree of i is reduced by 2. If individual j is susceptible then it becomes infective. If individual j is infective or recovered then nothing happens, apart from the edge being formed. The infective i also independently sends warning messages down its unpaired stubs at points of independent Poisson processes, each having rate . When i sends a warning message down a stub, that stub is paired with a stub (attached to individual j, say) chosen uniformly at random from all other unpaired stubs. If individual j is susceptible then the stub from individual i and the stub from individual j are deleted, corresponding to dropping of an edge in the original model. If individual j is infective or recovered then the two stubs are paired to form an edge. In all three cases, the effective degrees of i and j are reduced as above. Individual i recovers independently at rate , keeping all, if any, of its unpaired stubs. Note that in the formulation in Ball and Neal (2008), when an infective recovers, its unpaired stubs, if any, are paired immediately; however, that is not necessary and indeed complicates analysis of the model.

Note also that we now use the equivalent formulation of the process for dropping edges of Sect. 2, where dropping is driven by infectives rather than by susceptibles, although it is clear that the two formulations are probabilistically equivalent. The change is required for the effective degree formulation to model dropping of edges correctly.

Before proceeding we introduce some notation. For and , let and be respectively the numbers of susceptibles and infectives having effective degree i at time t. We refer to such individuals as type-i susceptibles and type-i infectives. For , let be the number of unpaired stubs attached to recovered individuals at time t. (Note that it is not necessary to keep track of the effective degrees of recovered individuals since only the total number of unpaired stubs attached to recovered individuals, and not the effective degrees of the individuals involved, is required in the above effective degree formulation.) Let , and . (Unless stated to the contrary, vectors are row vectors in this paper.) Let denote the state space of . Define unit vectors and on H, where, for example, has a one in the ith ‘susceptible component’ and zeros elsewhere, and has a one in the ‘recovered component’ and zeros elsewhere. Let denote a typical element of H, and let and . Thus and are the total number of stubs attached to susceptibles, infectives and recovered individuals, respectively, when .

The process is a continuous-time Markov chain with the following transition intensities, where an intensity is zero if , since then there is only one stub remaining.

For ,

-

(i)type-i infective infects a type-j susceptible

-

(ii)type-i infective ‘infects’ a type-j infective, so an edge is formed

-

(iii)type-i infective warns a type-j susceptible, so an edge is dropped

-

(iv)type-i infective ‘warns’ a type-j infective, so an edge is formed

For ,

-

(v)type-i infective ‘infects’ a recovered individual, so an edge is formed

-

(vi)type-i infective ‘warns’ a recovered individual, so an edge is formed

For ,

-

(vii)type-i infective recovers

Remark 3.1

(Comments on the intensities) Note that although the above intensities are all independent of N, we index them by N since that is required so that is a density dependent population process, see (3.6) and (3.7) below. Note also that the intensities in (ii) and (iv) above need to be modified slightly if to include the possibility that an infective ‘infects’ or ‘warns’ itself. For example, the intensity for a type-i infective ‘infecting’ itself is given by , so this should be subtracted from the intensity in (ii) when and included instead in a new transition, (ii’) say. It is easily verified that that as , so the modifications may be absorbed into the O(1 / N) term in (3.6) below and ignoring such transitions does not affect the LLNs and CLTs in the paper.

We now introduce notation for the jumps of . Note that the transitions in (ii) and (iv) above are identical, as are the transitions in (v) and (vi), so there are five types of jumps. For , let

| 3.1 |

| 3.2 |

| 3.3 |

for , let

| 3.4 |

and, for , let

| 3.5 |

Then, excluding self-infection and self-warning (see Remark 3.1), the set of possible jumps of from a typical state is , where

Let and , and . Further, let , and . For , let . For any , the intensities of the jumps of admit the form

| 3.6 |

with the functions given by

| 3.7 |

Remark 3.2

(Applying the theory of Ethier and Kurtz) The theory of density dependent population processes in Ethier and Kurtz (1986), Chapter 11, is for a class of continuous-time Markov chains whose state space is a subset of for some . Thus to use this theory we need to assume that there is a maximum degree, i.e. that , where . Then, for any , provided the sample paths of remain within , is a density dependent population process; see Appendix B for details. We conjecture that our results continue to hold when the condition is relaxed, provided suitable conditions are imposed on (i) the distribution of D and (ii), for epidemics on MR random graphs, the convergence of the empirical distribution of prescribed degrees.

The key theorems in Ethier and Kurtz (1986), Chapter 11, have their origin in Kurtz (1970, 1971). However, the proofs in Ethier and Kurtz (1986) are different from those in the earlier papers and the LLN is stronger in that it concerns almost sure convergence rather than convergence in probability. In Ethier and Kurtz (1986), the processes corresponding to are defined on the same probability space by using a single set of independent unit-rate Poisson processes indexed by the possible jumps .

A LLN and a functional CLT for density dependent population processes having countable state space are proved in Barbour and Luczak (2012a, b). They do not apply immediately to as the jumps of are unbounded, though that can be overcome by replacing by , where is the number of recovered individuals having effective degree i at time t. We do not consider here sufficient conditions for the theorems in Barbour and Luczak (2012a, b) to be satisfied in the present setting, since is satisfied for real-life epidemics. We note that LLNs for the Markov SIR epidemic () on an MR random graph with unbounded degree are given in Decreusefond et al. (2012) and Janson et al. (2014), and a functional CLT for the Markov SI epidemic () on an MR random graph with unbounded degree is given in KhudaBukhsh et al. (2017). It seems likely that similar techniques used in the first two of those papers will apply to the present model. LLNs for the Markov SIR epidemic () on an MR random graph with bounded degree are given in Bohman and Picollelli (2012) and Barbour and Reinert (2013), the latter for epidemics started by a trace of infection. Indeed our model (assuming bounded degrees) fits into the framework of Barbour and Reinert (2013), Sect 3.2.

Following Ethier and Kurtz (1986), define the drift function by

Substituting from (3.7) yields (see Appendix A for details)

| 3.8 |

Consider a sequence of epidemics indexed by N, each having . Suppose that and as , where and denotes almost sure convergence. Note that for epidemics on NSW random graphs is random and, depending on how the initial infectives are chosen, may also be random. The above almost sure convergence is reasonable for such epidemics since in an NSW random graph, the fraction of vertices of any given degree satisfies the strong law of large numbers. For epidemics on MR random graphs it is often more natural for to be non-random, in which case and as . Let and . The following result holds for epidemics on both MR and NSW random graphs.

Theorem 3.1

(LLN for epidemic on network with dropping)

Suppose that and . Then, for any ,

where is given by the solution of the following system of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) with initial condition :

| 3.9 |

| 3.10 |

| 3.11 |

where

| 3.12 |

and .

Proof

See Appendix B.

Remark 3.3

(Solving the ODEs (3.9)–(3.11)) The solution of the system of ODEs (3.9)–(3.11) is considered in Sect. 5. Note that under the conditions of Theorem 3.1 the system of ODEs (3.9)–(3.11) is finite, so existence and uniqueness of a solution follow from standard results. We do not consider existence and uniqueness of solutions to ODEs (3.9)–(3.11) when the degrees are unbounded but acknowledge that further justification and some regularity conditions will be required. A similar comment applies to the time-transformed system of ODEs (4.3)–(4.5) in Sect. 4.

For the epidemic on an MR random graph, a functional CLT for the fluctuations of about its deterministic limit is also available using Ethier and Kurtz (1986), Theorem 11.2.3, as we formulate in Theorem 3.2. See Sect. 7 for discussion of a corresponding CLT for the epidemic on an NSW random graph.

Write as and let denote the matrix of first partial derivatives of . For , let be the solution of the matrix ODE

| 3.13 |

where I denotes the identity matrix of appropriate dimension. Let

where denotes transpose. Note that is the coefficient matrix of the time-inhomogeneous linear drift of the limiting Gaussian process in Theorem 3.2 below and enables a representation of in terms of an Itô integral with respect to a time-inhomogeneous Brownian motion; see (7.1) in Sect. 7.

Theorem 3.2

(Functional CLT for epidemic on MR graph with dropping)

Suppose that and, for ,

| 3.14 |

where is constant. Then

| 3.15 |

where denotes weak convergence and is a zero-mean Gaussian process with and covariance function given by

Proof

See Appendix B, where a complete definition of is given.

Remark 3.4

(Computing the asymptotic variance) Theorem 3.2 yields immediately that

| 3.16 |

It follows from (3.13) and (3.16) that satisfies the ODE

| 3.17 |

with initial condition . Thus, provided , can be computed by numerically solving the ODEs (3.9)–(3.11) and (3.17) simultaneously.

Final outcome of epidemic on MR random graph

We conjecture a CLT for the final outcome of the epidemic with preventive dropping on an MR random graph (see Conjecture 4.1). In order to do so, we consider a random time-transformation of the real-time process.

For , let and be respectively the numbers of susceptible and infectious stubs at time t. Let , so the final number of susceptibles of different types is given by . For , let , so . Recall the definition of following (3.8). For , we derive a CLT for ; see Proposition 4.1. Assuming that Proposition 4.1 holds also when leads immediately to a CLT (Conjecture 4.1) for , and hence for the total number of individuals that are ultimately infected by the epidemic, since the latter is given by . A key step in deriving these CLTs is to consider the following random time-scale transformation of ; cf. Ethier and Kurtz (1986), page 467, and Janson et al. (2014), Section 3, where similar transformations are used to derive a CLT for the final size of the so-called general stochastic epidemic and a LLN for the Markovian SIR epidemic on an MR random graph, respectively.

For , let

and let . For , let and

Then is also a density dependent population process, having the same set of jumps as , and intensity functions given by

| 4.1 |

Note that when is in state , the clock in runs at rate times faster than the clock in , so the intensities in (4.1) are obtained by multiplying the corresponding intensities in (3.7) by . The drift function associated with is (cf. (3.8))

| 4.2 |

Let be the solution of the following system of ODEs, with initial condition :

| 4.3 |

| 4.4 |

| 4.5 |

where and , with and . The solution of this system is considered in Sect. 5.1.1. Let . It is shown in Appendix C that , i.e. the duration of the limiting time-changed deterministic epidemic is finite, unless .

We consider the same sequence of epidemics as for Proposition 3.1 in Sect. 3. Again, using Ethier and Kurtz (1986), Theorem 11.2.1, as , converges almost surely over any finite time interval , with , to (see Appendix B for further details of this and of the functional CLT given at (4.6)). Suppose further that the initial conditions satisfy (3.14) and . Then it follows using Ethier and Kurtz (1986), Theorem 11.2.3, that, for any ,

| 4.6 |

where is a zero-mean Gaussian process with and variance given by

| 4.7 |

where

| 4.8 |

and, for , is the solution of the matrix ODE

| 4.9 |

For , let . Further, for , let

| 4.10 |

so both and are decreasing with , and . We show in Appendix C that ; it is clearly finite if . Let , so

For fixed , application of Ethier and Kurtz (1986), Theorem 11.4.2, yields

| 4.11 |

where denotes inner vector product and denotes convergence in distribution. This result requires that

| 4.12 |

which we show in Appendix C. Condition (4.12) ensures that is a proper crossing time. Note that

where

| 4.13 |

and denotes outer vector product.

The following proposition follows immediately from (4.11) on noting that and , where .

Proposition 4.1

(CLT for ‘final’ outcome of epidemic on MR graph with dropping) Suppose that and (3.14) is satisfied. Then

| 4.14 |

where

and denotes a multivariate normal distribution (of appropriate dimension) with mean vector and variance–covariance matrix .

Remark 4.1

(Extending Proposition 4.1to) We are primarily interested in the case when . The difficulty in extending Proposition 4.1 to include is that to apply Ethier and Kurtz (1986), Theorem 11.4.2, we need the weak convergence at (4.6) to hold for some . Thus we need to extend the process so that it is defined beyond time . Now for (see (5.11) in Sect. 5.1.1), so we need to extend the state space of so that can be negative. However, this cannot be done so that the conditions of the LLN and CLT theorems in Ethier and Kurtz (1986) are satisified. In particular, in any neighbourhood of , the intensity functions are not bounded and the drift function is not Lipschitz continuous.

In work done while this paper was under review, the first author has found a way of overcoming this problem; see Ball (2018) which is in the setting of an SIR epidemic (without dropping of edges) with an arbitrary but specified infectious period distribution on configuration model networks. The theorems proved in Ball (2018) provide further (very strong) support for Conjecture 4.1 below, which assumes that Proposition 4.1 extends in the obvious way to include , and for subsequent conjectures which are contingent on Conjecture 4.1. Note that the final outcome of the epidemic is given by and the corresponding determinsitic outcome is .

We use the term final outcome to refer to that of the effective degree formulation, in which the degrees of susceptibles can change owing to dropping of edges. This is sufficient to determine the final size of an epidemic. If the final numbers of susceptibles of various original degrees are required, the effective degree formulation can be extended to keep track of both the original and effective degrees of suceptibles.

Conjecture 4.1

(CLT for final outcome of epidemic on MR graph with dropping) Suppose that and (3.14) is satisfied. Then

| 4.15 |

where

with B given by (4.13) with .

Remark 4.2

(LLN for final outcome of SIR epidemic with preventive dropping) Conjecture 4.1 implies that as , where denotes convergence in probability, i.e. the final outcome of the epidemic on an MR random graph obeys a weak LLN. The same conjecture holds also for the epidemic on an NSW random graph, using the theory in Sect. 7. Note that and an expression for is given in Eq. (5.26) in Sect. 5.3.

Remark 4.3

(Explicit expression for asymptotic variance of final size) Note that , and hence , can be computed numerically as described for in Remark 3.4. However, as detailed in Sect. 6 for the case , it is possible to derive an almost fully explicit expression, as a function of , for the asymptotic variance of the ‘final’ number of susceptibles. Moreover, the expression is fully explicit when , i.e. when there is no dropping of edges, so the model reduces to a standard Markov SIR epidemic on an MR configuration model network.

Deterministic temporal behaviour and final size

In Sect. 5.1 we study the deterministic temporal behaviour of the effective degree model, described by the system of ODEs (3.9)–(3.11) given in Theorem 3.1, by considering first the corresponding time-transformed system (4.3)–(4.5). The resulting (partial) solution of this system is required to calculate the asymptotic variance of the final size in Sects. 6 and 7. Furthermore, the results of this section are used in Appendix C to prove that the conditions and (4.12), required for the application of Ethier and Kurtz (1986), Theorem 11.4.2, are satisfied. In Sect. 5.2, we connect the analysis of (4.3)–(4.5) to other approaches taken in the literature for the deterministic analysis of epidemics on configuration model networks. Finally, in Sect. 5.3, we give a characterization of the deterministic final size of the epidemic and consider the final size of epidemics initiated by a trace of infection in Proposition 5.1. We do not consider existence and uniqueness of solutions of the determinstic model when (see Remark 3.3) but indicate where further justification is required for a proof.

Temporal behaviour

Time-transformed process

Consider the system of ODEs given by (4.3)–(4.5), with initial condition , and . In this section we obtain explicit expressions for , , and other variables pertaining to the fraction of susceptible, infectious, and recovered individuals in the population in the time-transformed process, while in Sect. 5.1.2 we connect these to corresponding variables in the real-time process.

Observe that the evolution of is decoupled from the rest of the system. To solve (4.3), let denote a transient continuous-time Markov chain describing the evolution of a single susceptible individual, whose stubs are independently dropped at rate and independently infected at rate . For , let X(t) be the number of stubs attached to the individual at time t, if it is still susceptible, otherwise let . Let , for and . By deriving the forward equation for it is easily seen that, for , ).

It is straightforward to calculate , since stubs disappear (by dropping or infection) independently, the probability that a given initial stub has disappeared by time t is and, given that a stub has disappeared, the probability its disappearance was caused by dropping is . Thus,

| 5.1 |

whence, for ,

| 5.2 |

where

| 5.3 |

and denotes the ith derivative of . It then follows that

| 5.4 |

where

| 5.5 |

Differentiating (5.4) yields

| 5.6 |

Note that and, using a similar argument to the derivation of (5.4),

| 5.7 |

Multiplying (4.4) by i and summing over yields

| 5.8 |

(This requires justifying and further conditions if . A similar comment applies to equations contingent on (5.8), such as (5.11).) Adding (5.6), (5.8) and (4.5) gives

which, together with the initial condition , yields

| 5.9 |

Substituting (5.9) into (4.5) yields

whence

| 5.10 |

Thus

| 5.11 |

Remark 5.1

(Fractions of susceptible, infectious, and recovered individuals) Although the above results are useful for analysing the final outcome of the epidemic, of greater practical interest is the evolution of the fractions of the population that are susceptible, infective and recovered individuals, which in the time-transformed process are given by and , respectively. Summing (5.2) over and using a similar argument to the derivation of (5.4) yields

| 5.12 |

Turning to , summing (4.4) over and using (5.4) yields

| 5.13 |

Let and

Then (5.13) has solution

| 5.14 |

We do not have a closed-form expression for the integral in (5.14), though it is straightforward to calculate numerically using the ODE (5.13). Finally, note that .

Real-time process

Turning to the system of ODEs (3.9)–(3.11), which describe the limiting evolution of the epidemic as the population size , let

| 5.15 |

where is given by (3.12). Then and it follows that, for ,

| 5.16 |

connecting the original process to the time-transformed process. Hence, , so (5.11) and (5.9) imply that is determined by

| 5.17 |

together with . The ODE (5.17) does not seem to admit an explicit solution, although it is straightforward to solve numerically.

Connection to other approaches

In this section we consider other deterministic formulations of the preventive dropping model and make the connection to the effective degree approach (ODE system (3.9)–(3.11)). Our focus is on the deterministic variable that is defined as follows:

| 5.18 |

Here, is the probability that an individual escapes infection from a given neighbour, up to at least t units of time after the neighbour became infected. In the Markovian SIR case with dropping of edges, this probability equals

| 5.19 |

Indeed, there are three competing events: transmission, ending of the infectious period, and informing the susceptible neighbour, that occur at rates , , and , respectively. We see immediately from the renewal equation for , obtained by substituting (5.19) into (5.18), that one can also interpret dropping of edges as an increased recovery rate for the deterministic mean temporal behaviour since only appears as part of the sum (see Remark 5.3 in Sect. 5.3). This aspect of the mean temporal behaviour may not be immediately clear from the system (3.9)–(3.11).

The variable can be interpreted as the probability that along a randomly chosen edge between two individuals, i and j say, there is no transmission from j to i before time t, given that no transmission occurred from individual i to j. The variable formed the basis for the edge-based compartmental models of Volz, Miller and co-workers (see e.g. Kiss et al. (2017) and references therein). Closely related to edge-based compartmental models is the binding site formulation presented in Leung and Diekmann (2016), where the relation to edge-based compartmental models is also explained. We use the binding site formulation in this section to state the renewal equation for the variable , restricting ourselves to the Markovian SIR epidemic (in Leung and Diekmann (2016) is used instead of ). In principle, the renewal Eq. (5.18) is far more general and allows for randomness in infectiousness beyond the Markovian setting, see Leung and Diekmann (2016) for details. Note that in the above works, the derivation of the equations describing the evolution of is heuristic. Those equations are proved for the Markov SIR epidemic on a configuration model network, in the sense of a large population limit, in Decreusefond et al. (2012) and Janson et al. (2014); see also Barbour and Reinert (2013).

The variable relates to the effective degree formulation as follows:

| 5.20 |

where the functions and from the effective degree formulation are defined at (5.5) and (5.15), respectively. Indeed, Eq. (5.20) is expected from the interpretation of : is the probability that the susceptible individual is informed by the infection status of a given neighbour before being infected by that neighbour, so the stub disappears through dropping, while is the probability that there is no dropping and the given stub has not disappeared at time (where accounts for the time-transformation, see (5.16)). One can check that (5.20) holds true by first transforming the renewal Eq. (5.18) into an ODE for by differentiating (and using (5.19)):

| 5.21 |

with initial condition . Next, differentiating the right-hand-side of (5.20), and using (5.17), we find that satisfies the ODE (5.21). Furthermore, the initial condition implies that .

Finally, the Malthusian parameter r, the basic reproduction number and the final size of the epidemic are easily derived from the single renewal equation (5.18). Here we only state the expressions and refer to Leung and Diekmann (2016), Section 2.5, for details. In the limit of the Euler–Lotka characteristic equation is

| 5.22 |

The Malthusian parameter r is the unique real root of (5.22) and a simple calculation yields

| 5.23 |

agreeing with Britton et al. (2016), equation (3). The basic reproduction number is obtained from (5.22) by evaluating the right hand side at , yielding the same expression as (2.1). The final size is discussed in Remark 5.2.

Final size

Recall that defined at (4.10) satisfies . In particular, using (5.11), satisfies

| 5.24 |

For later use, we rewrite (5.24) as

| 5.25 |

where and . Further, using (5.12) yields that the final proportion of the population that remains uninfected is given by

| 5.26 |

We let denote the fraction of the population ultimately infected in the limiting deterministic epidemic.

Let . Then in the limit as , i.e. for epidemics started by a trace of infection (or, more precisely, a trace of infected stubs), the final susceptible fraction is given by (5.26), where satisfies

| 5.27 |

We can now formulate the characterization for the final size of the epidemic. We illustrate the dependence of on the dropping rate in Sect. 10.4.

Proposition 5.1

(Deterministic final size) Suppose that .

- Suppose that . Then the fraction of the population that is ultimately infected in the deterministic epidemic is given by

where s is the unique solution in [0, 1) of5.28 5.29 - Suppose . Then in the limit as , the fraction of the population that is ultimately infected in the limiting deterministic epidemic is given by

where s is the unique solution in [0, 1) of5.30 5.31

Proof

(a) Suppose that . Let , so . It then follows from (5.25) and (5.26) that s satisfies (5.29) and is given by (5.28). Let and . Then and , since . Thus (5.29) has a unique solution in [0, 1) as is convex on [0, 1], since .

(b) Letting in (5.28) and (5.29) shows that is given by (5.30), where s satisfies (5.31). Let be as in (a) and . Then and , since . Further, is a convex function, so it follows that (5.31) has a solution in [0, 1) if and only if and moreover that solution is unique. Now and , so if and only if .

Remark 5.2

(Connection to the renewal Eq. (5.18)) Proposition 5.1(b) can also be derived by taking the limit in (5.18):

| 5.32 |

using (5.19), so satisfies (5.31). Then, using (5.12) and (5.16), one obtains that the proportion of the population that ultimately is susceptible agrees with (5.30).

Remark 5.3

(Increased recovery rate and no dropping) Observe that Eq. (5.18) for and (5.19) for together imply immediately that the process of susceptibles in the deterministic model with recovery rate and dropping rate depends on only through their sum , since and only appear in (5.19) through the sum . Furthermore, (5.20) relates the variable of the binding site formulation to the effective degree formulation through and defined at (5.5) and (5.15), respectively. Thus the LLN limit describing the evolution of susceptibles classified by their effective degree for the model with dropping is the same as that for the model without dropping (i.e. the standard Markov SIR epidemic on a configuration model network) but with the recovery rate increased to . In particular, this implies that the deterministic final size of the two models are the same, as is apparent immediately from Proposition 5.1. This invariance also holds for the basic reproduction number and Mathusian parameter r, as is clear from the formulae in Eqs. (2.1) and (5.23), respectively. Note however that the LLN limit describing the infectives is not the same for these two models, since infectives recover more quickly in the model with increased recovery rate. Thus (as illustrated in Fig. 9 in Sect. 10.6) at any time there are more infectives in the deterministic model with dropping than in the corresponding model with increased recovery rate and no dropping. We revisit the model with increased recovery rate and no dropping in Sect. 8, where we focus on the probability of a major outbreak in the stochastic model with few initial infectives.

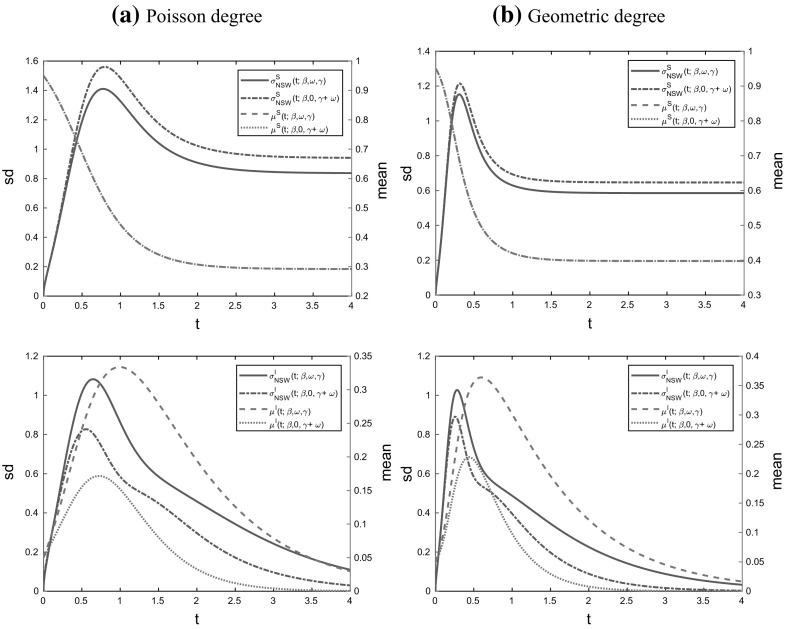

Fig. 9.

Scaled asymptotic means and standard deviations of the number of susceptible and infectious individuals through time (in the upper and lower plots, respectively), comparing the model with dropping to that with increased recovery rate. Model parameters are as in Fig. 7, except that . (Note that in the upper plots the two quantities are exactly equal)

Asymptotic variance of final size of epidemic on an MR random graph

Recall that denotes the number of susceptibles remaining at the end of the epidemic on an MR random graph. Thus denotes the final size of the epidemic. Note that, in an obvious notation, . Let and . Then, assuming the truth of Conjecture 4.1 for , the asymptotic variance of is given by

| 6.1 |

Suppose that and let z be the unique solution in [0, 1) of (5.25); cf. Proposition 5.1(a). The following proposition gives an almost fully explicit expression for the asymptotic variance .

Proposition 6.1

(Asymptotic variance of final size of epidemic on MR graph with dropping) Suppose that and . Then,

| 6.2 |

with

| 6.3 |

| 6.4 |

| 6.5 |

| 6.6 |

| 6.7 |

and .

Proof

The proof is rather long so only an outline is given here, with detailed calculations deferred to appendices. Let

| 6.8 |

where B is given by (4.13) with . Then, using (4.7) and (4.8),

| 6.9 |

The rest of the proof involves showing that the right-hand side of (6.9) yields the expression (6.2) for .

Recall that and note that is a scalar. It then follows that

| 6.10 |

where

| 6.11 |

Evaluation of (6.11) requires , which we now determine.

Let . Observe that , where , so using (4.2),

| 6.12 |

| 6.13 |

using , (5.7) and (5.9). Also, using (4.2), , so

| 6.14 |

where

| 6.15 |

Note from (4.2) that takes the partitioned form

| 6.16 |

It follows from (4.9) that has the partitioned form

Thus, using (6.8) and (6.14), we have

We show in Appendix D that

see (D.5), (D.26), (D.15) and (D.14), respectively. Hence,

| 6.17 |

where

| 6.18 |

| 6.19 |

| 6.20 |

with

We can now calculate using (6.11), (6.17) and (4.1), and hence obtain using (6.10). The details are lengthy and are given in Appendix E.

Recall from Sect. 5.3 that if then , where z is the unique solution in [0, 1) of (5.25), and if and then , where z is the unique solution in [0, 1) of (5.25) with replaced by ; cf. Proposition 5.1.

Conjecture 6.1

(CLT for of final size of epidemic on MR graph with dropping)

Remark 6.1

(Proving Conjecture 6.1) Part (a) of Conjecture 6.1 follows immediately from Conjecture 4.1 and Proposition 6.1; see Remark 4.1 for how Conjecture 4.1 might be proved. Part (b) of Conjecture 6.1 is concerned with epidemics started by a trace of infection, i.e. with . Similar CLTs for the final size of a wide range of SIR epidemics (e.g. von Bahr and Martin-Löf (1980), Scalia-Tomba (1985) and Ball and Neal (2003)) suggest that letting in the CLT with yields the correct CLT when for epidemics that become established and lead to a major outbreak. This is proved for the SIR epidemic without dropping of edges on configuration model networks in Ball (2018); see Remark 4.1. A similar proof should hold for the present model with dropping of edges.

Remark 6.2

(The condition) The condition in Proposition 6.1 and Conjecture 6.1 is required to ensure that ; recall from Sect. 5.3 that . Note from (5.28) that implies , so the LLN and functional CLT in Ethier and Kurtz (1986), Chapter 11, hold for both the original and random time-scale transformed processes and provided there is a maximum degree; see Appendix B. Further, as explained in Appendix C, if then if and only if . Now if and only if . Thus unless there is no recovery of infectives, no droping of edges and the limiting fraction of degree-1 susceptibles is 0. The same conclusion holds when .

Extension to iid degrees: epidemics on an NSW random graph

In this section we assume that the underlying network is constructed from a sequence of independent and identically distributed copies of the random variable D, which describes the degree of a typical individual. The random variables are used to construct a network of N individuals, yielding a realisation of NSW random graph. The almost sure convergence results described in Theorem 3.1 (and the corresponding time-transformed almost sure convergence result of Sect. 4) still hold for the present model, as noted previously, but the functional CLT and the CLT for the final size (Theorem 3.2 and Conjecture 6.1) need modifying, as the variability in the empirical degree distribution of the random network (and hence in the initial conditions for the effective degree process ) is of the same order of magnitude as that of the process itself. The modified results for epidemics on an NSW random graph are presented in Theorem 7.2 and Conjecture 7.1. In order to prove and motivate, respectively, these results we need a version of the functional CLT (Theorem 11.2.3) in Ethier and Kurtz (1986) that allows for asymptotically random initial conditions; see Theorem 7.1 below, which may be of more general interest beyond the present paper. Like the above-mentioned Theorem 11.2.3, Theorem 7.1 assumes a finite-dimensional state space, which for our application amounts to assuming that .

The limiting Gaussian process in Theorem 3.2 admits the Itô integral representation

| 7.1 |

where is a time-inhomogeneous Brownian motion (see Ethier and Kurtz (1986), Theorem 11.2.3, page 458) and . (To aid connection with Ethier and Kurtz (1986), and are now column vectors.) In Ethier and Kurtz (1986), Theorem 11.2.3, is nonrandom. In Theorem 7.1 below, we allow to be random.

Theorem 7.1

(Functional CLT for process with asymptotically random initial conditions) Suppose that the conditions of Ethier and Kurtz (1986), Theorem 11.2.3, are satisfied except that as , where . Then

| 7.2 |

where is a zero-mean Gaussian process with covariance function given, for , by

| 7.3 |

Proof

It is easily seen that the proof of Ethier and Kurtz (1986), Theorem 11.2.3, continues to hold in this more general setting. In particular, the limiting process satisfies (7.1), where now , so is a zero-mean Gaussian process. Further, the time-inhomogeneous Brownian motion arises as the weak limit, as , of the (suitably centred and scaled) Poisson processes used to construct realisations of , and hence is independent of . The covariance function in (7.3) then follows immediately from (7.1).

Remark 7.1

(Computing the asymptotic variance) Setting in (7.3) and differentiating as in Remark 3.4 shows that satisfies the ODE (3.17) but now with initial condition .

Remark 7.2

(Non-Gaussian limiting initial conditions) The covariance function (7.3) also holds when is non-Gaussian, provided and , though of course is no longer Gaussian.

Theorem 7.2

(Functional CLT for epidemic on NSW graph with dropping)

Suppose that as . Then the same functional CLT holds as in the MR graph situation (Theorem 3.2), but with the covariance function of changed in accordance with Eq. (7.3) and Remark 7.1 to reflect the randomness in the initial conditions.

Proof

The details of the proof, applying Theorem 7.1, are exactly the same as those in Appendix B where Theorem 11.2.3 of Ethier and Kurtz (1986) is applied to prove Theorem 3.2.

Remark 7.3

(The asymptotic variance matrix) Note that in Theorem 7.2 depends on how the initial infectives are chosen from the population. An example and some discussion can be found in Sect. 10.1. Also note that Theorem 7.2 as presented allows for the possibility of some initially recovered individuals in the population. This is to simplify the presentation of the theorem; the assumption of no initially recovered individuals implies that , from which it follows that and the last row and column of have all entries 0.

Next, we use Theorem 7.1 to conjecture a CLT for the final size of the epidemic on an NSW random graph. For , let denote a random variable with distribution given by the empirical distribution of , so

| 7.4 |

For , let be the final size of the epidemic on an NSW configuration model random graph having N vertices. We consider epidemics initiated by a trace of infection and assume that the variability in the initial conditions is owing entirely to the variability in .

Conjecture 7.1

(CLT for final size of epidemic on NSW graph with dropping)

Suppose that , , and . Then, in the event of a major outbreak,

| 7.5 |

where

| 7.6 |

with given by (6.2) (replacing by D in (6.3)–(6.7)) and

| 7.7 |

We now give the argument leading to this conjecture. Suppose, for the time being, that and consider the random time-scale transformed process , defined in Sect. 4, but now for the epidemic on an NSW network. Using (4.6) and Theorem 7.1, for any ,

where is a zero-mean Gaussian process with variance–covariance matrix at time t given by

| 7.8 |

is given by (4.7) and , with being defined as in Theorem 7.1. Then arguing as in the derivation of Proposition 4.1 yields, for any ,

| 7.9 |

where

| 7.10 |

We now assume that (7.9) extends to the case , so (7.5) holds with

cf. (6.1). Thus, using (7.8) and (7.10),

| 7.11 |

where

| 7.12 |

using (6.14).

We now assume that the above extends in the obvious way to and calculate the resulting asymptotic variance . Write

| 7.13 |

Then

| 7.14 |

where and are the deterministic ‘number’ of susceptible individuals and infectious half-edges, given by (5.26) and (5.11), respectively, but with (random) initial conditions induced by the NSW random graph on N vertices.

Recall the function and the random variable , defined at (5.5) and (7.4), respectively. It follows from (5.26) that

| 7.15 |

and, from (5.11), that

| 7.16 |

Let . Note, for example, that , so and is asymptotically normally distributed by the CLT for independent and identically distributed random variables. This and similar elementary calculations show that

| 7.17 |

| 7.18 |

| 7.19 |

| 7.20 |

| 7.21 |

| 7.22 |

Recall that , and (see (5.25) and Proposition 5.1(b)). Setting in (5.27) then gives (cf. (5.25))

| 7.23 |

Then, using (7.15) and (7.17),

| 7.24 |

using (7.15), (7.16), (7.20) and (7.22)

| 7.25 |

and

| 7.26 |

It follows from (5.4), (6.13), (6.15) (all with replaced by D) and (7.23), that

| 7.27 |

so

| 7.28 |

Note that , where is given by (6.3) with replaced by D. Substituting (7.24), (7.25) and (7.26) into (7.14), and invoking (7.23) and (7.28), yields (7.7) after a little algebra.

Remark 7.4

(Proving Conjecture 7.1) The two remaining steps required to prove Conjecture 7.1 are to justify (i) that (7.9) holds when and (ii) letting to obtain a CLT in the event of a major outbreak; cf. Remarks 4.1 and 6.1 which discuss these steps, respectively, for an epidemic on a MR random graph. As for epidemics on MR random graphs, the proofs in Ball (2018) for the SIR epidemic without dropping of edges on an NSW random graph should extend to the model with dropping of edges.

Remark 7.5

(Conjecture 7.1with) It is possible to extend Conjecture 7.1 to consider also the case and obtain an analogous result to Conjecture 6.1(a). The asymptotic variance is given by (7.11) and (7.12) but now depends on how the initial infectives are chosen.

Increased recovery rate instead of dropping edges

Recall the equivalent formulation of the model with dropping in which an infectious individual sends out warnings to each neighbour independently at rate , and susceptible individuals who receive such a warning immediately drop the corresponding edge. Consider a different but related model where, instead of sending out warnings to each neighbour at rate independently, one single warning (at rate ) is used for all neighbours simultaneously (and all of them immediately drop the edges). The effect of this change is that edge droppings become dependent. However, from the point of view of a given susceptible neighbour the probability that it drops its edge to a given infective is unchanged. Thus, for a given susceptible, such a warning (where all susceptible neighbours drop their edges) has the same effect as if its infective neighbour recovered. Hence, we consider a model without dropping, but with recovery rate instead of . We use and to refer to the two models, where the first component refers to the recovery rate and the second component to the dropping rate.

The above reasoning suggests that the dropping model should in some ways resemble this modified model. In fact, we have seen already in Sect. 5.3 (Remark 5.3) that, as , the scaled process of susceptibles in the two epidemics converge to the same LLN limit, and the same LLN holds for the final fraction getting infected. However, the two models are stochastically different, even for the process of susceptibles. The underlying reason for this difference is that independent warning signals makes the total number of infections less variable compared to having one warning signal to all susceptible neighbours. Consequently, the probability of a major outbreak is greater in the dropping model than in the modified model, as we prove in Theorem 8.1 below. Furthermore, we expect that the decrease in variability of the number of infections made by an infective decreases the limiting variance of both the whole process of susceptibles and the final size in the event of a major outbreak compared to the modified model. This is illustrated by the numerical results in Sect. 10.6.

Consider the beginning of an outbreak and an infectious individual having k susceptible neighbours. Let be the number of these k neighbours that the infectious individual infects in the dropping model and define similarly for the modified model. We compute the distributions of these two offspring random variables.

In the model we first condition on the infectious period I, which has an distribution, i.e. an exponential distribution with rate and hence mean . Given the duration of the infectious period , the infectious individual infects each of its k susceptible neighbours independently, and a given neighbour is infected if and only if there is an infectious contact before t and the edge has not been dropped before then. Thus, conditional upon , the probability that the given neighbour is infected is

Given , the number of neighbours infected follows a binomial distribution with parameters k and the probability above. Hence, if we relax the conditioning, it follows that has the mixed-Binomial distribution

| 8.1 |

Setting and yields immediately that

| 8.2 |

It is not hard to show that

| 8.3 |

and that .

Suppose that the epidemic is initiated by a single individual, chosen uniformly at random from the entire population, becoming infective. Then the number of susceptible neighbours of the initial infective is distributed according to D and, during the early stages of an outbreak in a large population, the number of susceptible neighbours of a subsequently infected individual is distributed as (see Sect. 2). These results hold for both models. It follows that the early stages of the dropping model in a large population can be approximated, on a generation basis, by a Galton–Watson branching process having offspring distribution that is a mixture of , , with mixing probabilities in the initial generation and mixing probabilities in all subsequent generations, where . (Note that , , is the probability mass function of .) A similar approximation holds for the modified model, except is replaced by . These approximations can be made rigorous in the limit as the population size by using a coupling argument, as in e.g. Ball and Sirl (2012). In the limit as , the probability of a major outbreak in the epidemic model is given by the probability that the corresponding approximating branching process does not go extinct.

The following lemma, proved in Appendix F, is required for the proof of Theorem 8.1 below, which shows that the probability of a major outbreak is greater in the dropping model than in the corresponding modified model. First, some more notation is required. For let , , denote the probability-generating function (PGF) of , the number of neighbours that an infectious individual with k susceptible neighbours infects in the early stages of the dropping model, and define similarly for the modified model. Let . Then, for the dropping model, the approximating branching process has offspring PGF in the first generation and offspring PGF in all subsequent generations, with analogous results holding for the model.

Lemma 1

Suppose that and . Then, for ,

| 8.4 |

with strict inequality for all when .

Theorem 8.1

(Probability of a major outbreak)

The basic reproduction number for both the dropping and modified models is given by (2.1).

- Suppose that and the epidemic is initiated by a single infective individual, chosen uniformly at random from the population. Then the probability of a major outbreak for the dropping model is strictly greater than the probability of a major outbreak for the modified model, i.e.

8.5

Proof

The basic reproduction number is given by the offspring mean of a typical (i.e. non-initial generation) infective, so for both models, using (8.3),

which proves part (a).

Turning to part (b), suppose that . Then, using standard branching process theory gives that, for the dropping model, the probability of a major outbreak is given by , where is the unique solution in [0, 1) of ; cf. Kenah and Robins (2007) and Ball and Sirl (2013). Analogously, for the modified model, , where is the unique solution in [0, 1) of .

Note that if then , so implies that . It then follows immediately from Lemma 1 that and for all . Hence, since and the derivative of both and at is , it follows that , whence , as is strictly increasing on [0, 1]. Thus we obtain our statement (8.5).

Remark 8.1

(Other choices for initial infectives) Theorem 8.1 is easily extended to other assumptions concerning initial infectives; for example, to an epidemic initiated by infective individuals chosen uniformly at random from the population, or to an epidemic initiated by an infective of a specified degree.

No dropping of edges

We use the results from this paper to analyse the Markovian SIR epidemic on a configuration model network in Sect. 9.1 and the giant component of a configuration model network in Sect. 9.2. Note that in the case that there is no dropping of edges, i.e. , we are in the setting of a Markovian SIR epidemic on a configuration model network. We treat the asymptotic variance of the final size for this model in Conjecture 9.1. If additionally, there is no recovery, i.e. , then in the event of a major outbreak, all individuals in the giant component eventually get infected. By using this we can apply the results from this paper to make statements about the size of the giant component in configuration model random graphs, see Conjecture 9.2.

SIR epidemic on configuration network

When , the model reduces to the Markov SIR epidemic on a configuration model network. The formulae for the asymptotic variance of the final size for the epidemic on MR and NSW random networks simplify and become fully explicit given z, defined below.

Recall that . If , then setting in Proposition 5.1(a) shows that , where z is the unique solution in [0, 1) of

| 9.1 |

If , so the epidemic is started by a trace of infection, and then, using Proposition 5.1(b), , where z is the unique solution in [0, 1) of (9.1) with replaced by .

Let and denote the final size of the epidemic, with no dropping of edges, on an MR and NSW configuration model random network, respectively, each having N vertices. Let and denote the asymptotic variance of the final size for the epidemic on an MR and an NSW configuration model random network, respectively. The following conjecture gives fully explicit formulae for and as functions of z, which are derived in Appendix G.

Conjecture 9.1

(CLT for final size of epidemic on configuration model networks)

- For the epidemic on an NSW network, suppose that , , and . Then, in the event of a major outbreak,

where9.5

and is given by (9.4), with replaced by D.9.6

Remark 9.1

(Proof of Conjecture 9.1) Although only conjectured here, Conjecture 9.1 (and hence also Conjecture 9.2 below) follow as a special case of Ball (2018), Theorems 2.1 and 2.2.

Remark 9.2

(Epidemics on NSW random network with) As for the model with dropping, Conjecture 9.1(b) can be extended to include the case ; the asymptotic variance then depends on how the initial infectives are chosen (cf. Remark 7.5).

Configuration model giant component

If then the epidemic ultimately infects all individuals in all components of the random network that contain at least one initial infective. Thus, under suitable conditions, in the limit as , setting in Conjecture 9.1(a)(ii) and (b) leads to CLTs for the size of the largest connected (i.e. giant) component in MR and NSW configuration model random graphs, respectively.

Let and note that, setting in the formula for , if and only if . The above configuration model random graphs possess a giant component if and only if , see e.g. Durrett (2007), Theorem 3.1.3. Suppose that . Setting and in (9.1) shows that z is now given by the unique solution in [0, 1) of

| 9.7 |

and the asymptotic fraction of vertices in the giant components of the above configuration model random graphs is given by .

Let and denote respectively the size of the giant component in an MR and an NSW random graph on N vertices. Setting in Conjecture 9.1 (a)(ii) and (b) yields the following conjecture.

Conjecture 9.2

(CLT for the size of the giant component)

Suppose that , and . Then,

- for an MR random graph,

where9.8 9.9 - for an NSW random graph,

where9.10 9.11

It is easily verified that the expressions (9.9) and (9.11) for the asymptotic variances and coincide with those first obtained by Ball and Neal (2017) using a completely different method; a CLT was conjectured in that paper and subsequently proved for an MR random graph in Barbour and Röllin (2019), and for both MR and NSW random graphs by Janson (2018). The results proved in these three papers allow for unbounded degrees under suitable conditions.

Numerical examples

In this section we give numerical results which exemplify some of the limit theorems and support some of the conjectures presented in the paper and give examples of using those limiting results for approximation. Such approximations follow from our asymptotic results in exactly the same way as the approximate distribution of the sum of independent and identically distributed random variables follows from the classical CLT. For example, we can use Eq. (3.15) in Theorem 3.2 to say that, for large N, the distribution of is approximately that of , from which approximations for the mean and variance of follow immediately from the corresponding properties of the Gaussian process . We also explore numerically some aspects of the behaviour of the model we have analysed, using the asymptotic results we have derived. In our numerical examples relating to the temporal evolution of the epidemic we look only at the mean and variance of the number of infective individuals in the population, we do not investigate any other quantities of interest or explicitly investigate the covariance/correlation structure in any way.

In this section we use the notation or to denote that the network degree distribution follows a standard Poisson or Geometric distribution with mass functions () or (), respectively. In particular we shall use repeatedly in our examples the distributions and . These distributions both have mean 5 and their standard deviations are and respectively.

First, however, we discuss some of the issues that arise in relation to the numerical implementation of our analytical results.

Implementation

The numerical implementation of our asymptotic results concerning epidemic final size (the formulae laid out in Propositions 5.1 and 6.1 and Conjecture 7.1) is straightforward, involving root-finding, numerical integration and derivatives up to order 3 of the degree distribution PGF . For the degree distributions we use, we have when and when , with both formulae being valid for . In the final size examples we always use the version of these results with , i.e. we work under the asymptotic regime where the epidemic starts with a trace of infection. The results concerning the evolution of the epidemic through time (Theorems 3.1, 3.2 and 7.2) warrant discussion of some issues that arise.

An obvious first issue is initial conditions and for the system of ODEs given by (3.9)–(3.11) together with the variance/covariance-related matrix ODE (3.17) (see also Remark 7.3). In an MR network we take the initial infectives to comprise a fixed number of individuals, with numbers of individuals of the various degrees chosen in the same proportions as they are present in the whole population. In an NSW network we choose the required number of initial infectives uniformly at random from the population. Ideally we might want the initial conditions to represent a large outbreak initiated by few initial infectives; this is a rather more complex situation and could be addressed using the results of Ball and House (2017).

Let be the proportion of individuals initially infected in the limit as . It is straightforward to show that and similarly that and (cf. the paragraph immediately before Theorem 3.1; with a NSW network these limits hold almost surely). Turning to , in the case of an MR network we have chosen the initial conditions so that there is no variability; i.e. all elements of are zero. With an NSW network there is variability in the initial conditions; to characterise it we let be the number of initially infected individuals (or assume that is a function of N such that ) and use the notation for the (i, j)-th element of the submatrix of corresponding to the susceptible elements (cf. the partitioning in (7.13)), so for example . We find that the following elements of are non-zero: for all i, and ; and for all , and . Derivations can be found in Appendix H.

After solving the ODE systems numerically we can calculate the asymptotic means and variances for other quantities of interest, for example to approximate , the number of infected individuals at time t, we use

The final ODE-related issue is choosing the value of M, the maximum degree, to use when the degree distribution does not have finite support. (This amounts to setting for all and .) The upper bound M needs to be large enough that the approximation is accurate but not so large that the systems of ODEs are impractical to solve numerically (the number of ODEs grows like ). To decide on an appropriate value for M we compare plots of the asymptotic means and variances of I(t) (i.e. the solid lines in the lower plots of Fig. 1), increasing M until there is no observable difference in these plots. We also compare the predicted relative ‘final’ size from the numerical ODE solution to the asymptotic final size predicted by Proposition 5.1. For the degree distributions we find that is sufficient when and when .

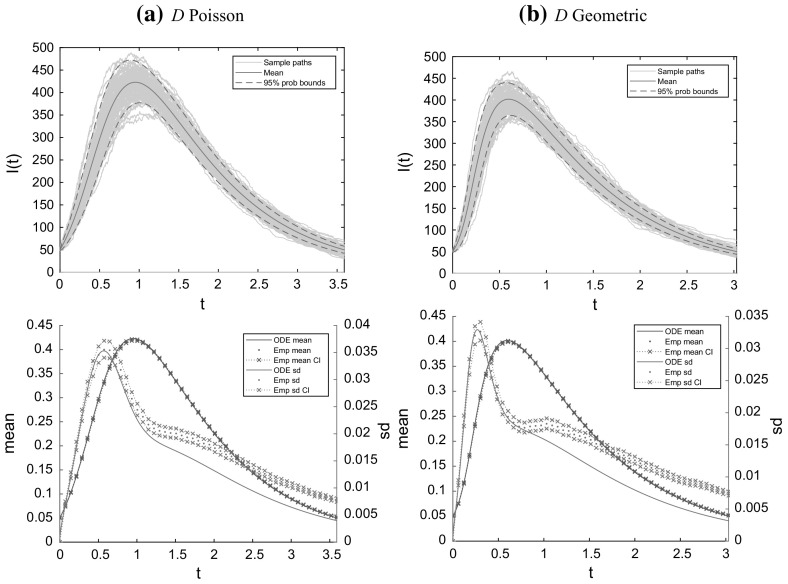

Fig. 1.

Demonstration of approximation implied by Theorem 7.2, for a and b. The upper plots show 100 simulated sample paths of the number of infectives against time t, together with the mean and central 95% probability bands for predicted by the functional CLT. The lower plots show asymptotic values and estimates from 1000 simulations of the scaled mean and standard deviation of the number of infectives through time. Other parameters are , , , , (All plots are truncated at the time when the proportion of individuals that are infective drops below 0.05)

Simulation of the epidemic process is relatively straightforward. Given a sequence of degrees (either [MR] a specified sequence or [NSW] independent realisations from the distribution ) we (i) generate the network, (ii) choose initial infectives, (iii) spread the epidemic on the network. There is therefore randomness in each simulation deriving not just from the evolution of the epidemic, but also the graph construction and, in the case of an NSW graph, the degree sequence. When we calculate confidence intervals (CIs) for quantities associated with simulations of the temporal evolution of the epidemic they are calculated independently for each time point; i.e. they are not confidence bands for the process. Endpoints of CIs for standard deviations are calculated as the square roots of the endpoints of standard symmetric (in terms of probability) CIs for the variance.

Convergence and approximation of temporal properties

First we demonstrate numerically some of the limit theorems from earlier sections, showing both how the convergence is realised and thus how these limit theorems can be used for approximation. We give examples only with an NSW graph construction, but much the same observations apply in the MR graph scenario.

In Fig. 1 we demonstrate using Theorem 7.2 for approximation of the temporal evolution of the epidemic, comparing simulated trajectories of the prevalence (for ) versus time t of the model with predictions from the functional central limit theorem, for a Poisson and a Geometric degree distribution. The upper plots show the simulated trajectories together with the mean and a central 95% probability band predicted by the CLT; they suggest that the approximation is fairly good. The lower plots compare the mean and standard deviation of the prevalence through time with the LLN and CLT based asymptotic predictions.

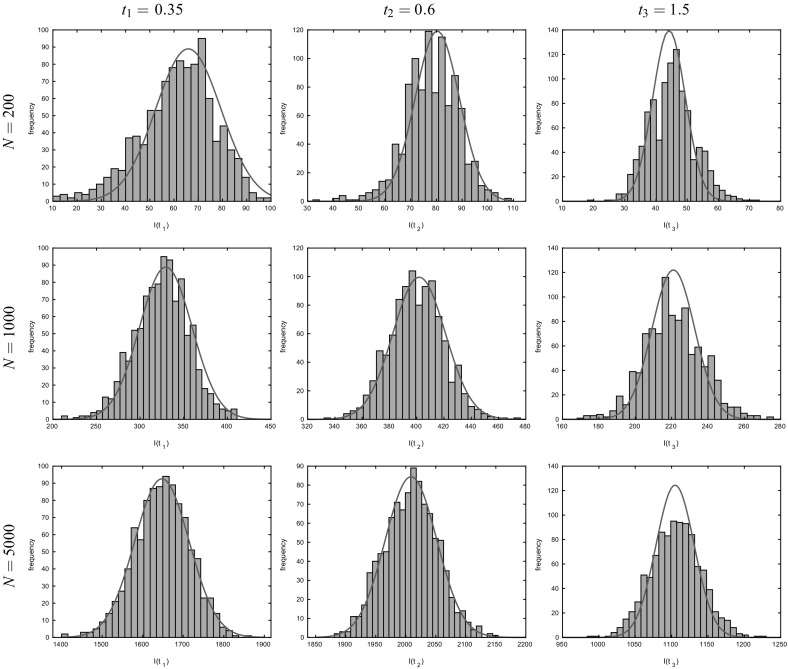

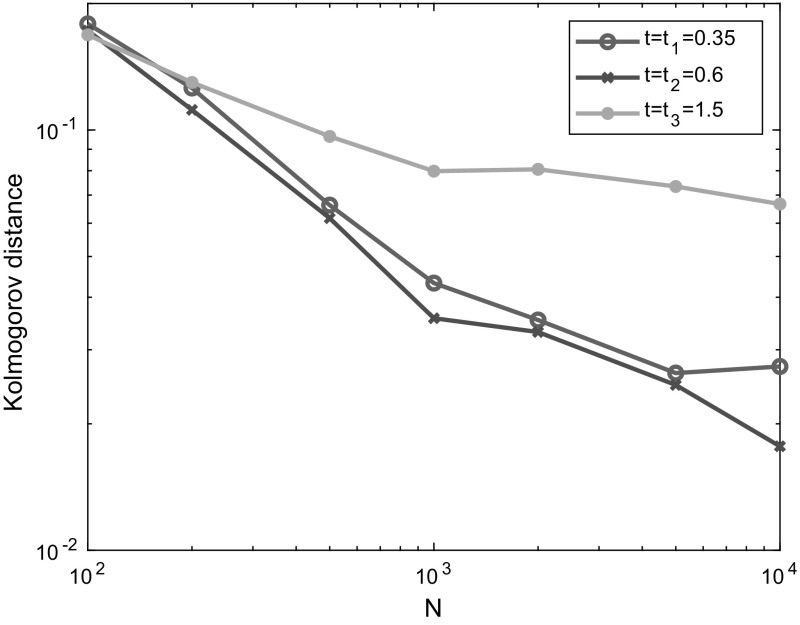

In Fig. 2 we investigate the convergence of the distribution of to its limit at three time points , and . The times are chosen so that is close to the time of peak prevalence and and are when prevalence is increasing and decreasing, respectively, at a level roughly half that of the peak prevalence. (Effectively we are examining the upper-right plot of Fig. 1 in detail at these three time points.) In this figure we have used a geometric degree distribution, but very similar conclusions are obtained using different distributions. This convergence is further investigated/demonstrated in Fig. 3, where, separately for each of the same three time points, we plot the Kolmogorov distance between the empirical and asymptotic distributions of the number of infectives against population size N.

Fig. 2.

Demonstration of convergence described by Theorem 7.2, for . Histograms of (based on 1000 simulated trajectories) and normal approximation for three fixed time points , , and 3 population sizes , , . Other parameters are , , ,

Fig. 3.

Demonstration of convergence described by Theorem 7.2, for . The distribution of (based on 5000 simulated trajectories) and its normal approximation are compared using the Kolmogorov distance at three fixed time points , , for population sizes . Other parameters are , , ,

Broadly speaking, Fig. 1 and similar plots for other population sizes, together with Figs. 2 and 3 and similar plots for other degree distributions, show that the predicted convergence is apparent, but seems slower for the later times. Even for quite small population sizes in the low hundreds, the asymptotic approximation to the mean behaviour of the epidemic is excellent. With smaller population sizes of a few hundred the approximation of the variability seems quite good in the early phase of epidemic growth, begins to worsen at or slightly before the time of peak prevalence and consistently underestimates the variability of after that. As the population size increases, the approximation for the standard deviation improves but not as quickly as one might hope: the agreement between asymptotic and empirical distributions seems to improve fairly slowly as N increases from 200 to 5000. Thus we can be very confident in using an LLN-based approximation for nearly any population size; but CLT-based approximations must be used with some caution, particularly at and after the time of peak prevalence. For these later times, a CLT-based approximation seems to systematically underestimate the variability in the number of infectives in the population. On a slightly more theoretical note, the plausibly linear (though also decidely noisy) behaviour of the plots in Fig. 3 is consistent with these Kolmogorov distances tending to 0 as . Consistent with the observations above, this convergence is at roughly the same rate for the time points in the early growth phase and near peak prevalence but much more slowly for the later time point in the phase where the infection is dying out.

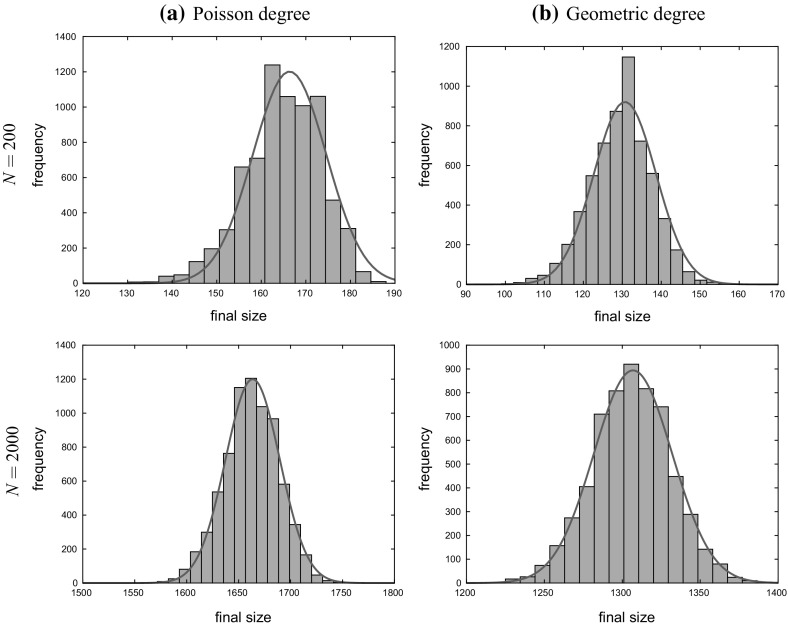

Approximation of epidemic final size

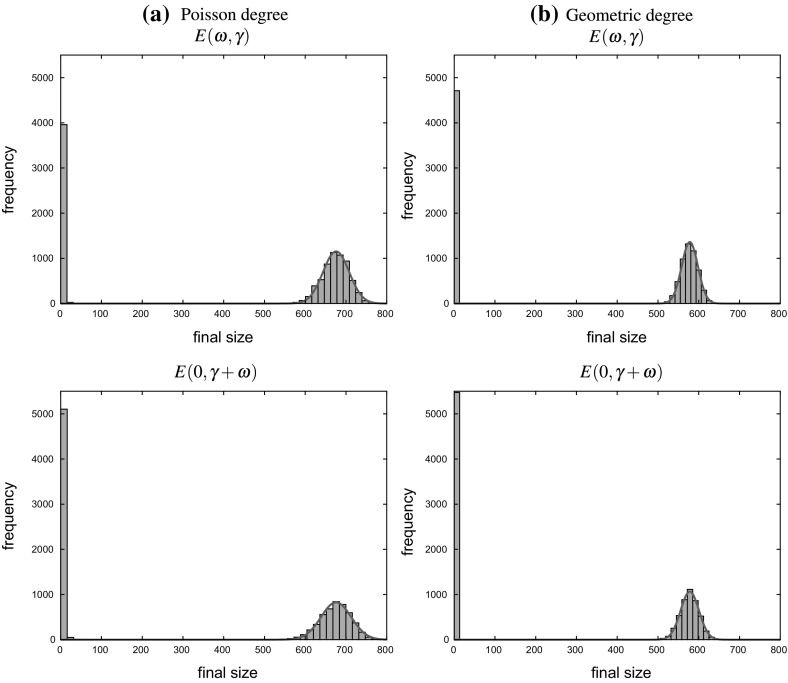

In Fig. 4 we demonstrate approximation results for the final size of major outbreaks in our epidemic model on an NSW graph (Conjecture 7.1). Again we see that the approximation is quite reasonable for relatively small population sizes in the low hundreds and becomes very good indeed for population sizes in the thousands.

Fig. 4.

Histograms (based on 10,000 simulations) and normal approximation of the final size distribution of major outbreaks for epidemics on graphs with a, b and varying populations sizes . Other parameter values are , and

The effect of dropping