Abstract

The spinocerebellar ataxias (SCAs) comprise more than 40 autosomal dominant neurodegenerative disorders that present principally with progressive ataxia. Within the past few years, studies of pathogenic mechanisms in the SCAs have led to the development of promising therapeutic strategies, especially for SCAs caused by polyglutamine-coding CAG repeats. Nucleotide-based gene-silencing approaches that target the first steps in the pathogenic cascade are one promising approach not only for polyglutamine SCAs but also for the many other SCAs caused by toxic mutant proteins or RNA. For these and other emerging therapeutic strategies, well-coordinated preparation is needed for fruitful clinical trials. To accomplish this goal, investigators from the United States and Europe are now collaborating to share data from their respective SCA cohorts. Increased knowledge of the natural history of SCAs, including of the premanifest and early symptomatic stages of disease, will improve the prospects for success in clinical trials of disease-modifying drugs. In addition, investigators are seeking validated clinical outcome measures that demonstrate responsiveness to changes in SCA populations. Findings suggest that MRI and magnetic resonance spectroscopy biomarkers will provide objective biological readouts of disease activity and progression, but more work is needed to establish disease-specific biomarkers that track target engagement in therapeutic trials. Together, these efforts suggest that the development of successful therapies for one or more SCAs is not far away.

The spinocerebellar ataxias (SCAs) are a group of autosomal dominant disorders characterized by progressive ataxia due to degeneration of the cerebellum and its afferent and efferent pathways1. The prefix ‘SCA’ with an associated number (which reflects the order of genetic discovery) is assigned to dominantly inherited ataxias when their genetic loci are defined. Although the term SCA describes a broad category of disorders in which spinocerebellar degeneration occurs — including phenotypically similar recessive disorders (sometimes called recessive SCAs), mitochondrial disorders and sporadic disorders — here we focus on the autosomal dominant SCAs. Currently, SCAs numbered from 1 to 46 are registered in the Online Mendelian Inheritance of Men (OMIM) database at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), although some are vacant (such as SCA9) and others overlap (for example, SCA15 and SCA16 are both designated to the same disorder). In general, SCAs fall into two major categories on the basis of their genetic mutations: SCAs caused by microsatellite repeat expansions (FIG. 1; TABLE 1) and SCAs caused by point mutations (TABLE 2). When considering disease-causative mechanisms, SCAs resulting from repeat expansions can be further divided into those caused by polyglutamine (polyQ)-coding CAG repeat expansions and those caused by non-protein-coding repeats (TABLE 1). The pathogenic mechanisms of SCAs are complex and differ substantially among these diverse classes of the mutation2. The clinical features, management and pathogenic mechanisms of the SCAs or specific subsets of SCAs have been reviewed extensively elsewhere2–6. Here, we focus primarily on challenges in therapeutic development for the SCAs. We review the scientific premise and rigour of preclinical and molecular data relevant to such challenges and assess current gaps that need to be filled before promising drugs for SCAs can be tested in clinical trials.

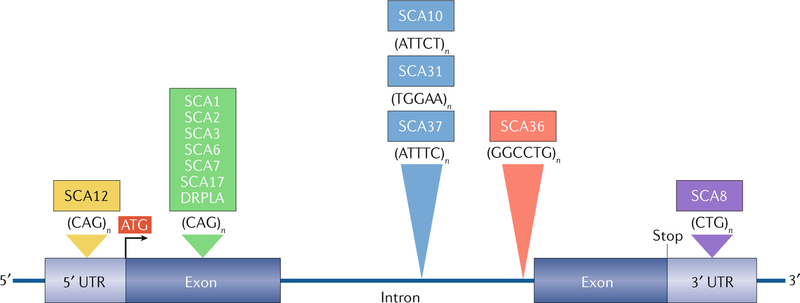

Fig. 1 |. Hereditary degenerative ataxias caused by expanded microsatellite repeats.

A CAG repeat expansion within the open reading frame of the respective genes associated with the spinocerebellar ataxias (SCAs) 1, 2, 3, 6, 7 and 17 and dentatorubral-pallidoluysian atrophy (DRPLA; green) encodes an elongated polyglutamine (polyQ) tract in the protein product. The CAG repeat in SCA12 (yellow), present in PPP2R2B, is shown in the 5′ untranslated region (UTR) in this figure but can be intronic depending on the transcription start site. In SCA8 (purple), a CTG repeat is located in the 3′ UTR of ATXN8OS. However, the complementary CAG repeat on the opposite strand encodes polyQ in ATXN8. Four large intronic microsatellite repeats include three pentanucleotide repeats (blue) in SCAs 10, 31 and 37 and one hexanucleotide repeat (red) in SCA36. In SCA31, a TGGAA repeat is located in BEAN1, and a TTCCA repeat is found in TK2 on the opposite strand, although only the UGGAA-containing transcripts are shown to be pathogenic. Likewise, the large ATTTC repeat, but not the ATTTT repeat, is pathogenic in SCA37. In SCA10, the risk of epilepsy increases sixfold when the ATTCT repeat is interrupted by a stretch of ATCCT repeat. In SCA36, an expanded GGCCTG repeat (with high sequence homology with the GGGGCC repeat in C9orf72) is present in NOP56.

Table 1 |.

SCAs caused by microsatellite repeat expansions

| Disease | Gene (repeat location) | Repeats, principal repeat unit | Notable characteristic clinical signs | Anticipation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | Intermediate | Disease | ||||

| SCAs caused by polyglutamine-coding CAG repeat expansions | ||||||

| SCA1 | ATXN1 | 6–39a | 40 | 41–83 | Hypermetric saccades and pyramidal signs | + |

| SCA2 | ATXN2 | <31 | 31–33 | 34–200 | Slow saccades and areflexia | +b |

| SCA3 | ATXN3 | 12–44 | 45–55 | 56–86 | Bulged eyes and motor neuron signs | + |

| SCA6 | CACNA1A | <18 | 19 | 20–33 | Downbeat nystagmus | − |

| SCA7 | ATXN7 | 4–19 | 28–33 | 34 to >460 | Visual loss | + |

| SCA17 | TBP | 25–40 | – | 41–66 | Huntington disease-like | −b |

| DRPLA | ATN1 | 6–35 | 36–48 | 49–88 | Huntington disease-like | + |

| SCAs caused by non-coding microsatellite repeat expansions | ||||||

| SCA8c | OSATXN8 (3′ UTR) | 15–34, CTG or CAG | 34–89, CTG or CAG | 89–250, CTG or CAG | Reduced penetrance | − |

| SCA10d | ATXN10 (intron) | 8–32, ATTCT | 33–799, ATTCT | 800–4,500, ATTCT, ATTCC, ATCCT or ATCCC | Some families with epilepsy | + (in some families) |

| SCA12 | PPP2R2B (5′ UTR) | 7–28, CAG | 29–66, CAG | 67–78, CAG | Tremor | − |

| SCA31e | BEAN (intron) | <400, ATTTT | Unknown | 500–760 TGGAA | Pure cerebellar ataxia | + |

| SCA36 | NOP56 (intron) | 3–14, GGCCTG | Unknown | 650–2,500 | Motor neuron disease | − |

| SCA37f | DAB1 (5′ UTR; intron) | <400, ATTTT | Unknown | 31–75, ATTTC repeats within ATTTT repetas | Pure cerebellar ataxia | − |

DRPLA, dentatorubral-pallidoluysian atrophy; SCA, spinocerebellar ataxia; UTR, untranslated region.

In SCA1, CAT interruption(s) are present in many normal alleles11.

CAA interruptions affect repeat stability in SCA2 and SCA17 and affect toxicity and, potentially, phenotype in SCA2.

Expanded SCA8 repeats can contain one or more CCG, CTA, CTC, CCA or CTT interruptions, which affect the stability of the repeat and, potentially, the penetrance.

In SCA10, the presence of ATCCT repeats, which often accompanies an ATCCC repeat tract, is associated with epilepsy and alters the pattern of repeat instability and anticipation.

In SCA31, the presence of TGGAA repeats is essential for pathogenicity.

In SCA37, the presence of ATTTC repeats is pathogenic. Data were extracted from Online Mendelian Inheritance of Men (OMIM) and GeneReviews of corresponding SCAs.

Table 2 |.

SCAs caused by point mutations

| Disease | Gene | Mutation | Notable characteristic clinical signs |

|---|---|---|---|

| SCA5 | SPTBN2 | Missense | Downbeat nystagmus and some patients with spasticity, anticipation |

| SCA11 | TTBK2 | Missense | Some patients with pyramidal signs |

| SCA13 | KCNC3 | Missense | Variable between families |

| SCA14 | PRKCG | Missense | Tremor or myoclonus, facial myokymia |

| SCA15 and 16 | ITPR1 | Deletion | Pure cerebellar ataxia with tremor |

| SCA18 | IFRD1 | Missense | Sensorimotor neuropathy |

| SCA19 and 22 | KCND3 | Missense, in-frame 3bp deletion | Extracerebellar features variable between families |

| SCA20 | Multiple (DAGLA)a | 260kb duplication | Pure cerebellar ataxia with spasmodic dysphonia, palatal tremor |

| SCA21 | TMEM240 | Missense | Cognitive impairment, extrapyramidal signs |

| SCA23 | PDYN | Missense | Extracerebellar features variable between families |

| SCA26 | EEF2 | Missense | Pure cerebellar ataxia |

| SCA27 | FGF14 | Missense | Mental retardation, tremor |

| SCA28 | AFG3L2 | Missense | Spastic ataxia |

| SCA29 | ITPR1 | Missense | Pure cerebellar ataxia, congenital non-progressive |

| SCA34 | ELOVL4 | Missense | Hyperkeratosis, MSA-C-like |

| SCA35 | TGM6 | Missense | Hyperreflexia and variable other extracerebellar features |

| SCA38 | ELOVL5 | Missense | Pure cerebellar ataxia, some patients have sensory neuropathy |

| SCA40 | CCDC88C | Missense | Spastic ataxia |

| SCA41 | TRPC3 | Missense | Pure cerebellar ataxia |

| SCA42 | CACNA1G | Missense | Dementia |

| SCA43 | MME | Missense | Peripheral neuropathy |

| SCA44 | GRM1 | Missense, +1bp frameshift | Spasticity |

| SCA45 | FAT2 | Missense | Pure cerebellar ataxia (single family) |

| SCA46 | PLD3 | Missense | Sensory neuropathy |

MSA-C, multiple system atrophy of cerebellar type. Data were extracted from Online Mendelian Inheritance of Men (OMIM) and GeneReviews of corresponding SCAs.

aThe duplicated region in direct orientation contains 12 or more genes, including DAGLA.

Diagnosis

Key observations that support a diagnosis of an SCA in patients with progressive cerebellar ataxia include a family history of similar disease and a high index of suspicion of a genetically based disease. However, a lack of family history does not necessarily exclude SCA5, as incomplete family history, uninformed adoption and other causes of nonaternity, early death of a transmitting parent, low penetrance and de novo mutations can be present. When apparent sporadic ataxia is evaluated, treatable causes must be excluded carefully before hereditary causes of ataxia are considered6 (FIG. 2). In early stages of SCA, the phenotype can present as purely cerebellar, but subsequent, non-ataxic manifestations usually emerge. Owing to phenotypic overlap, a specific diagnosis of SCA is usually difficult without DNA testing, although certain findings can help to predict the genotype (see notable characteristic clinical signs in TABLES 1,2).

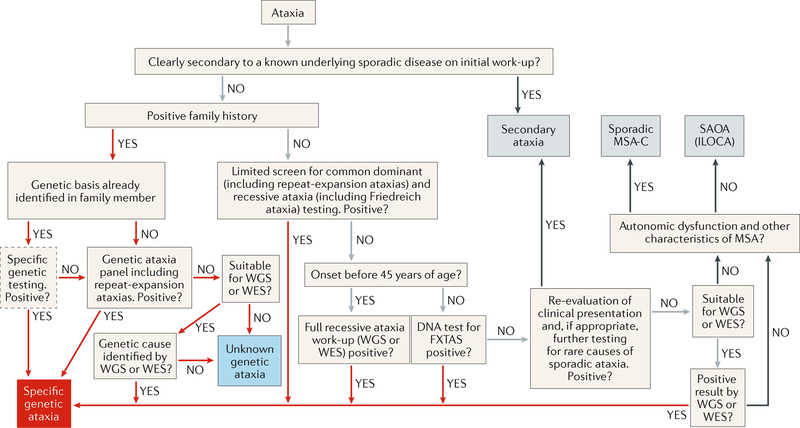

Fig. 2 |. Diagnostic algorithm for progressive ataxias.

Red arrows show steps to the diagnosis of inherited ataxias. Grey arrows indicate processes in which a genetic ataxia is still included in the differential diagnosis. Black arrows are routes to diagnoses of non-genetic ataxias. Obvious secondary ataxia should be excluded before a diagnosis of a spinocerebellar ataxia (SCA) can be made. The next step is to determine whether ataxia is inherited. If genetic diagnosis is already known in the family, optional confirmatory genetic testing is advised. If genetic diagnosis is unknown, panel testing or selective genotyping for dominant and/or recessive ataxias is recommended. If results are negative, whole-exome sequencing (WES), and potentially whole-genome sequencing (WGS), can lead to the specific genetic diagnosis. When no family history is present of a similar ataxic disorder, treatable causes of progressive ataxias should be explored on the basis of the differential diagnosis (for example, immune-mediated ataxias). Once treatable causes are excluded, genetic testing can be considered in patients with apparently sporadic ataxia. After exclusion of secondary ataxias and genetic ataxias, the diagnosis of either probable multiple system atrophy of cerebellar type (MSA-C) or sporadic adult-onset ataxia (SAOA; also known as idiopathic late-onset cerebellar ataxia (ILOCA)) can be established on the basis of the diagnostic criteria. FXTAS, fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome.

The most common SCAs are repeat-expansion diseases. A first step in establishing a diagnosis of a specific SCA is to screen for these repeat expansions, particularly for the most common subtypes — SCA1, SCA2, SCA3, SCA6 and SCA7. An important consideration is that sporadic-onset ataxia in an adult can be Friedreich ataxia, the most common recessive ataxia, which also results from a repeat expansion that can be easily tested for. Detection and sizing of repeat-expansion mutations are currently accomplished by conventional PCR, repeat-primed PCR or Southern blot analyses, depending on the size of the repeat. Internal repeat sequence irregularities are found in some SCAs, which can alter the characteristics of repeat length stability7–10. The expansion size and, in some SCAs, repeat-interrupting motifs can substantially alter disease penetrance, age at onset or even clinical manifestations. In SCA1, for example, CAT interruptions are an important determinant for the difference between normal alleles and disease alleles; a CAT interruption in the SCA1 CAG expansion reduces penetrance of the mutation7,11. Interruptions in the repeat expansions are also associated with a parkinsonian phenotype in SCA2 (REFS8,12,13), SCA10 (REF.14), SCA17 (REFS15,16) and possibly SCA8 (REF.16) and might increase the risk of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in SCA2 (REFS17–19) and epilepsy in SCA10 (REF.20) (TABLE 1).

For SCAs caused by point mutations, whole-genome sequencing (WGS) and whole-exome sequencing (WES) are useful for the detection of mutations in known SCA genes and in the identification of new genetic causes of SCA21. However, detection of variants of unknown importance by WES or WGS could necessitate an extensive family study for co-segregation of the variant with the disease as well as assessment of the biological consequences of the variant in silico and in experimental models to determine the potential pathogenic importance of the variant. Repeat expansions are difficult to detect with WGS and WES because short sequence reads obtained in next-generation sequencing (NGS) cannot be assembled effectively in repeat regions, but new NGS technologies that enable long sequence reads are emerging, including CRISPR–Cas9-targeted direct genomic single-molecule real-time sequencing (SMRT)14, nanopore22 sequencing and analytical advances such as the RepeatHMM alignment23.

Treatment

With a few exceptions (for example, SCA6), SCAs are relentlessly progressive, fatal diseases. No drugs for SCAs have been approved by the FDA or European Medicines Agency (EMA). However, multiple studies support the efficacy of coordinative physical therapy24–30 with the caveat that all previous studies were unblinded or evaluator-blinded trials with a small number of participants (allied health care in ataxia has been reviewed systematically elsewhere31). A double-blind sham-controlled trial of transcranial magnetic stimulation involving 74 patients with spinocerebellar degeneration suggested that this treatment can alleviate ataxia for a week32,33. Many agents for SCAs have been tested in clinical trials, including randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies (Supplementary Table 1), and more therapies are being tested in ongoing clinical trials (Supplementary Table 2). Development of efficacious drugs for SCAs, both symptomatic and disease-modifying, is urgently needed.

Disease-modifying drugs

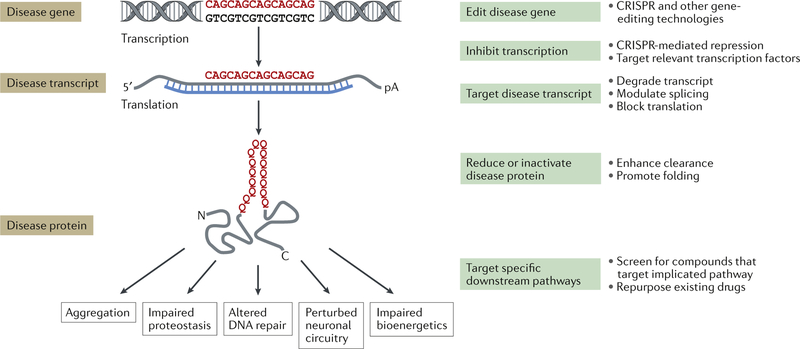

For dominantly inherited diseases such as the SCAs, the most compelling therapeutic targets lie upstream in the pathogenic cascade, regardless of the type of mutation and pathogenic mechanism (FIG. 3). Directing treatment to the root cause (in the case of SCAs, the mutation) or targets close to the root cause generally makes sense, although this concept has not yet been clinically tested in the treatment of SCAs. A special consideration for SCAs that result from a repeat expansion is that the expansion size generally determines the disease severity, progression rate and age of onset. Different degrees of expansion could change the pathogenic process, both quantitatively and qualitatively, which could confound the selection of targets for molecular interventions. The time of intervention is also likely to be a crucial issue for disease-modifying treatments. Data from SCA animal models suggest that prevention or delay of disease onset is easier than slowing, halting or reversing the disease process in symptomatic patients, especially in advanced stages of disease34–37.

Fig. 3 |. Therapeutic strategies for the SCAs.

A generic CAG repeat polyglutamine disease gene is used to illustrate positions along the pathogenic cascade for which disease-modifying therapeutic approaches are being developed. Examples of specific strategies at each point are shown on the right. Five representative downstream consequences of the spinocerebellar ataxia (SCA) disease protein are shown that represent potentially targetable pathways shared across multiple SCAs; this list is not intended to be comprehensive. C, carboxyl terminus; N, amino terminus; pA, polyadenosine tail.

PolyQ SCAs.

At least seven degenerative ataxias are caused by expanded CAG repeats encoding polyQ tracts: SCAs 1, 2, 3, 6, 7, 17 and dentatorubral-pallidoluysian atrophy, the last of which shares features with the SCAs and another polyQ disease, Huntington disease (HD) (TABLE 1). In these disorders, a gain of toxic function by the mutant protein plays a key part in the pathogenic mechanism2, although the precise basis of this toxicity remains unresolved. Although the normal functions of SCA polyQ disease proteins differ greatly, several of them might interact with one another directly or indirectly in the protein interactome of vulnerable cells in the nervous system38,39. The native physiological functions of the protein can also be compromised by the expansion and lead to partial loss of function in some SCAs2,38,40,41 as in HD42,43. Although research points to aberrant properties of the mutant polyQ disease protein as key drivers of disease, RNA transcripts containing the expanded CAG repeat also might be toxic, as demonstrated in experimental models of HD and of several polyQ SCAs44–48.

A further complication of our understanding of disease mechanisms is the fact that the disease gene can also produce an antisense transcript from the opposite DNA strand, which contains a complementary expanded RNA repeat, as shown in SCAs 8, 2 and 7 (REFS49–52). Furthermore, some expanded repeats form hairpin structures that can trigger noncanonical (non-ATG initiated) translation of protein across the repeat in all three reading frames53. This repeat-associated non-ATG (RAN) translation, which was first described in SCA8 (REF.53), has since been demonstrated in cellular and animal models of several SCAs and other repeat-expansion disorders. However, the extent of the pathogenic contribution of RAN translation to SCAs and other ataxias remains uncertain53–57. Nevertheless, these observations highlight that multiple toxic molecules can be generated from the expanded repeat in polyQ and other SCAs resulting from repeat expansions (FIG. 3).

Expanded microsatellite repeats generally exhibit repeat length instability in the germ line and soma, and polyQ-coding CAG repeats are no exception. With respect to intergenerational instability, the pattern of instability (for example, predilection towards further expansion and the extent of repeat size change) varies depending on the disease gene and the sex of the transmitting parent. Such differences are mostly attributable to germline instability patterns, which differ between men and women, whereas somatic instability differs between tissues58. Repeat-expansion size has profound effects not only on the age at disease onset but also on disease phenotype, which further complicates the application of therapeutic strategies that are based on downstream protein interactions in some of the SCAs.

The dominant nature of the SCAs indicates several points of potential therapeutic intervention, illustrated in FIG. 3. As for many genetic disorders, the ideal treatment would be correction of the mutation. Although genome editing is technically feasible, therapeutic applications of zinc-finger nucleases, transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs) and CRISPR–Cas nucleases in SCAs currently face numerous challenges, including delivery, off-target effects, indel formation at the double-strand break by nonhomologous end joining and other toxicity or safety concerns59–62. Furthermore, the discovery of anti-CRISPR proteins that inhibit the CRISPR–Cas system could complicate this promising technology63.

Targeting of the mutant mRNA transcript might be the next best option after genome editing for engaging the root cause of disease2,64 (FIG. 3). Experimental results with antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs), small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) and artificial microRNAs (miRNAs) in cellular and animal models of polyQ diseases have shown promising preclinical efficacy65,66 (TABLE 3). Most of these strategies have not yet advanced to human clinical trials, with the exception of ASOs. For example, a phase I/IIa trial of an ASO targeting HTT mRNA in participants with HD achieved a dose-dependent reduction in the levels of mutant huntingtin protein measured in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)67.

Table 3 |.

Candidate disease-modifying drugs for treatment of SCAs

| SCA type | Candidate drug | Scientific premise | Preclinical study | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCA1 | MSK1 inhibitor | Inhibitors of the RAS–MAPK–MSK1 pathway decrease levels of ATXN1 and alleviate neurodegeneration in cellular and animal models of SCA1 (REFS68,69) | Further screening and optimization is ongoing | Strong scientific premise. Rigorous preclinical studies are planned. No relevant human clinical observations |

| SCA1 | Stereotactic AAV-mediated delivery of miRNA-like RNAi | RNAi suppresses polyglutamine-induced neurodegeneration in an SCA1 mouse model196. Therapeutic benefits after RNAi expression vector delivery to deep cerebellar nuclei197 | RNAi prevents and reverses phenotypes induced by mutant human ATXN1 (REF.198) | Preclinical study is ongoing in B. Davidson’s laboratory under the NIH CREATE BIO199 grant support, which mandates rigorous preclinical study designs and go/no-go milestones200 |

| SCA2 | Dantrolene | Inhibits intracellular Ca2+ release and protects Purkinje cells from cell death in the SCA2–58Q mouse model201 | Feeding SCA2–58Q mice with dantrolene alleviated age-dependent motor deficits (beam-walk and rotarod assays)201 | Modest scientific premise. Needs rigorous preclinical studies. No relevant human clinical observations |

| SCA3 | Dantrolene | Inhibits intracellular Ca2+ release and protects neuronal cells in pontine nuclei and substantia nigra regions from cell death in SCA3-YAC-84Q transgenic mice202 | Feeding SCA3-YAC-84Q transgenic mice with dantrolene improved their motor performance202 | Modest scientific premise. Needs rigorous preclinical studies. No relevant human clinical observations |

| SCA3 | Citalopram | Identified in an unbiased screening for inhibition of mutant ATXN3 aggregation and reduction of ATXN3 neurotoxicity through neuronal serotonin pathways in cell and animal models70 | Efficacy of citalopram was verified in multiple SCA3 transgenic animal models, with chronic treatment leading to decreased neuronal ATXN3 aggregates, astrogliosis, weight loss and motor dysfunction70 | Strong scientific premise. Good preclinical studies in two independent laboratories. No relevant human clinical observations |

| SCA3 | Aripiprazole | Identified in an unbiased screen of FDA-approved drugs for reduction of the level of mutant ATXN3 in a cell-based assay71 | Not yet done | Unknown mechanism(s) of the effect on the mutant ATXN3. Needs rigorous preclinical studies in SCA3 animal model(s). No relevant human clinical trials or observations |

| SCA3 | Lentiviral delivery of allele-specific203 and allele-nonspecific204,205 siRNA against Atxn3 in a rat model | Silencing of Atxn3 mitigates degeneration in rat. Suppression of wild-type Atxn3 has no adverse effects and allele-nonspecific silencing might be beneficial in rat203–205 | Further preclinical studies are needed | Strong scientific premise for targeting the mRNA of the mutant ATXN3. Therapeutic efficacy shown in the rat model needs to be replicated in mouse models. Needs rigorous preclinical studies in SCA3 animal models. No relevant human clinical trials or observations |

| SCA3 | Stereotactic AAV delivery of miRNA | RNAi suppresses ATXN3 levels and alleviates molecular phenotype in SCA3 mouse models206,207 | RNAi has induced no behavioural changes | Strong scientific premise for targeting the mRNA of the mutant ATXN3. Needs rigorous preclinical studies in SCA3 animal models. No relevant human clinical trials or observations |

| SCA1, SCA2 and SCA3 | ASO against ATXN1, ATXN2 or ATXN3 | In these SCAs, toxic gain-of-function mechanisms are well established. Targeting the mRNA containing toxic polyglutamine expansion is supported by a strong rationale2 | Reduction of mutant ATXN2 (REF.208) and ATXN3 (REF.209) mRNA by ASO treatment, and skipping of CAG- repeat-containing exon 10 of ATXN3 (REF.210), are promising therapeutic approaches | Strong scientific premise for targeting the mRNA of the mutant ATXNs. Needs rigorous preclinical studies in animal models of SCA. No relevant human clinical trials or observations |

| SCA6 | miR-3191–5p | In SCA6, the CAG expansion is found in the second cistron (α1ACT) of CACNA1A. miR-3139 attenuates IRES-driven translation of toxic α1ACT66 | AAV9–miR-3191–5p protected α1ACT-Q33 mice from ataxia, motor deficits and Purkinje cell degeneration66 | Toxic mutant mRNA is the target. Needs rigorous preclinical studies in SCA6 animal models. No relevant human clinical trials or observations |

| SCA7 | Direct delivery of AAV or miRNA to retina in an SCA7 mouse model211 | In SCA7, toxic gain-of-function mechanisms are well established2,3. Targeting of the mRNA containing a toxic polyglutamine expansion is supported by a strong rationale. Eyes are severely affected in SCA7 and are readily accessible for delivery of miRNA211 | Non-allele-specific suppression of ATXN7 levels was accompanied by preservation of retinal function in SCA7 mice | Both wild-type and mutant ATXN7 mRNA are targeted. Needs rigorous preclinical studies in SCA7 animal models. No relevant human clinical trials or observations |

| SCA7 | Direct delivery of AAV or miRNA to cerebellum of a mouse model of SCA7 (REF.212) | In SCA7, toxic gain-of-function mechanisms are well established. Targeting of the mRNA containing a toxic polyglutamine expansion is supported by a strong rationale | Non-allele-specific suppression of ATXN7 levels was accompanied by improvement of ataxic phenotype in SCA7 mice | Both wild-type and mutant ATXN7 mRNA are targeted. Needs rigorous preclinical studies in SCA7 animal models. No relevant human clinical trials or observations |

α1ACT, α1A carboxyl terminus; AAV, adeno-associated virus; ASO, antisense oligonucleotide; ATXN, ataxin; CREATE BIO, Cooperative Research to Enable and Advance Translational Enterprises for Biotechnology Products and Biologics; IRES, internal ribosome entry site; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; miRNA, microRNA; MSK1, nuclear mitogen and stress-activated protein kinase 1; RNAi, RNA interference; SCA, spinocerebellar ataxia; siRNA, small interfering RNA.

Specific therapeutic targets might also be identifiable when the downstream pathogenic pathways triggered by a given mutant polyQ protein are well characterized (FIG. 3). An example in SCA1 is inhibitors of nuclear mitogen and stress-activated protein kinase 1 (MSK1; also known as RPS6KA5) in the RAS–mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)–MSK1 signalling pathway. MSK1 regulates phosphorylation at a critical amino acid in mutant ataxin 1 (REF.68). Genetic reduction of the levels of MSK1 was beneficial in SCA1 mouse models and resulted in decreased levels of mutant ataxin 1 and, correspondingly, reduced neurodegeneration and an improved disease phenotype69.

For some SCAs, unbiased screening of small molecules has identified compounds that might have therapeutic benefits even when the mechanism of action remains unknown. For example, compound screening in a nematode model of SCA3 identified citalopram, a widely used antidepressant, as a promising candidate drug. Citalopram was shown to decrease the levels of ataxin 3 and improve motor behavioural phenotype in an SCA3 mouse model70. Similar screening efforts in cell-based platforms identified aripiprazole, an atypical antipsychotic, as a compound that might reduce levels of mutant ataxin 3 (REF.71).

The accumulation of aggregated protein in polyQ SCAs suggests that efforts to enhance protein quality-control pathways in the brain offer a route to disease-modifying therapy (reviewed elsewhere2,72). Increasing the expression of specific molecular chaperones or quality-control ubiquitin ligases can suppress disease features in a variety of cellular and animal models of disease73–77. Conversely, quality-control pathways are impaired in several polyQ diseases78–81, which further supports the utility of boosting pathways that maintain protein homeostasis. Despite the attraction of co-opting protein quality control for therapy, compounds that act in this manner have not yet progressed to clinical trials in SCAs.

SCAs caused by toxic RNA.

Some rare SCAs are caused by an expanded microsatellite repeat in an intron (including SCAs 10, 31, 36 and 37) or 3ʹ untranslated region (such as SCA8) (FIG. 1; TABLE 1). In these disorders, expanded repeats consist of trinucleotide, pentanucleotide or hexanucleotide units and bind to RNA binding proteins (RBPs). This binding can result in a loss of function of the RBP or the formation of stress granules, which leads to cellular toxicity. Viable strategies that intervene in the upstream portion of the pathogenic pathway might include reduction of the level of toxic RNA by ASO or other RNA interference (RNAi) technology, disruption of the interaction between the toxic RNA and the RBP by decoys or competitors, overexpression of the RBP and modulation of stress granule formation. These approaches also would eliminate expression of toxic polypeptides produced through RAN translation of non-coding RNA repeats53–57. Other approaches such as unbiased screening and interventions that target pathways downstream of the toxic RNA effects might also yield therapeutic strategies, but will require further characterization of the pathogenic pathway of each disease.

SCAs caused by point mutation.

The use of NGS has led to the discovery of an increasing number of SCAs caused by point mutations. These mutations are mostly missense but a few involve deletion or duplication of a DNA segment consisting of a small number of nucleotides (TABLE 2). The majority of these disorders are rare, with some affecting only a single family. Most of the mutations identified are predicted to lead to a novel toxic function or a dominant negative effect by the mutant protein. Therapeutic strategies for such SCAs might involve gene silencing, skipping of the mutated exon by RNAi or ASO technologies or intervention in specific downstream pathways. Several SCAs of this class are caused by mutations in ion channels or in proteins involved in signal transduction pathways linked to cell surface receptors82,83 (TABLE 2). Thus, pharmacological modifications of the dysfunctional molecules in these SCAs might lead to sustainable symptomatic improvements.

Symptomatic treatments

No efficacious symptomatic treatments currently exist for SCAs. The FDA has approved 4-aminopyridine (4-AP) for improvement of gait disturbance in multiple sclerosis (MS) but not in the SCAs84,85. Nevertheless, 4-AP has been shown to normalize cerebellar Purkinje cell firing and alleviate motor coordination deficits in mouse models of SCA1 and SCA6 (REFS86,87). The Ministry of Health in Japan has approved the thyrotropin-releasing hormone mimetic agent taltirelin hydrate for spinocerebellar degeneration but it has not been approved in other countries88,89. Although many FDA-approved drugs have been tested in randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials in individuals with SCA (Supplementary Table 1), none has resulted in approval for treatment of SCAs by the FDA or the EMA. The failure of such trials stems in part from inconsistent outcomes, underpowered trial designs or suboptimal data analyses. Most of these clinical trials were based on a limited scientific premise, and many lacked rigorous preclinical data (Supplementary Table 1). Although serendipity should not be ignored and can lead to valuable discoveries of new drugs, solid scientific premise and rigorous preclinical data will be essential for future symptomatic drug treatments and have been highlighted by the NIH as crucial elements for translational and clinical research aiming to successfully develop new therapeutics90.

An attractive route to symptomatic therapy is modulation of the ion channels that underlie cerebellar circuitry (reviewed previously91). Several lines of evidence indicate the involvement of impaired cerebellar electro-physiology in ataxia. Mutations in genes that encode potassium and calcium channels or relevant signalling receptors underlie various forms of ataxia in mice and humans, including SCAs and episodic ataxias. In addition, changes in the intrinsic excitability of cerebellar Purkinje cells and synaptic signalling pathways precede robust neurodegeneration in numerous mouse models of polyQ SCAs (reviewed previously2). Furthermore, restoration of normal cerebellar electrophysiology, genetically or pharmacologically, has proved beneficial in mouse models of SCA86,87,91,92. Potassium channels, which play a key part in regulation of the excitability and dendritic plasticity of cerebellar Purkinje cells, are a particularly attractive therapeutic target93–99. Thus, a building scientific premise exists for the use of activators of small-conductance, calcium-activated potassium channels, such as chlorzoxazone100 and NS13001 (REF.92), as well as compounds with complex actions on ion channels such as riluzole. Riluzole elicited a substantial improvement in the Scale for the Assessment and Rating of Ataxia (SARA) total score in heterogeneous groups of patients with ataxia, including those with SCAs101,102. As noted earlier in the article, 4-AP also might be worth studying, particularly given its clinical usefulness in treating gait disturbance in MS (TABLE 4).

Table 4 |.

Candidate symptomatic drugs for treatment of SCAs

| SCA type | Candidate drug | Scientific premise | Preclinical study | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCA6 and other SCAs | 4-Aminopyridine | Restoration of pacemaker activities of Purkinje cells by blocking the voltage- dependent family of potassium channels87 | Alleviated motor coordination deficits and restored Purkinje cell firing precision in SCA6 mice homozygous for 84 polyQ repeats87 | Approved by the FDA for symptomatic improvement of walking in multiple sclerosis. A randomized, double- blind, placebo- controlled study showed a decreased number of attacks in patients with episodic ataxia 2 (reF.213). A phase I study214 and a small open- label study215 have been done in patients with SCAs |

| SCA2 and other SCAs | Chlorzoxazone | KCNN1 channel activator. Normalization of the Purkinje cell spontaneous firing rate in SCA2 transgenic mice with 58 polyQ repeats100 and in Cacna1a- mutant mice93 | Not yet done | Chlorzoxazone is approved by the FDA and has been used extensively as a muscle relaxant |

| SCA44 | Nitazoxanide | Negative allosteric modulator of metabotropic glutamate receptor 1 and 5 with potent inhibition of mutant forms of these receptors in transfected cells214 | Not done in SCA44 models, but similar modulators alleviated ataxia in an SCA1 mouse model216,217 | Nitazoxanide is approved by the FDA and is used for various helminthic, protozoal and viral infections218 |

KCNN1, small-conductance calcium-activated potassium channel protein 1; polyQ, polyglutamine; SCA, spinocerebellar ataxia.

Preparation for sound clinical trials

Future clinical trials of therapeutic compounds must be carefully justified with a strong scientific premise and rigorous preclinical evidence of efficacy. These considerations are particularly important for trials of disease-modifying therapies, partly because of the scarcity of patients with SCA. The collective prevalence of all known types of SCAs has been estimated as 1.0–5.6 per 100,000 individuals3,4,103–106; as such, the number of individuals with any one of the SCAs is far less than 200,000 in the United States and satisfies the FDA and NIH criteria for rare diseases107. The limited number of patients available for clinical trials restricts the number of applicable clinical trial designs and the number of drugs that can be tested. Investigators will need to establish which cohort of participants will be studied, the natural history of the specific SCA being investigated, the clinical outcome measures that will be used, which biomarkers can be used to objectively track the disease-related biological changes and the expected effect size and the potential adverse events of the agents to be tested. With the availability of such information, statistically valid clinical trial designs must be carefully chosen with the strictest control of variables achievable given the inherently small sample size of these rare diseases.

Assessment measures

Natural history

Under NIH funding, the Clinical Research Consortium for Studies of Cerebellar Ataxias (CRC-SCA) obtained natural history data on the most common types of polyQ SCAs (namely, SCAs 1, 2, 3 and 6) with SARA108 as the primary outcome measure109. The study included 60 individuals with SCA1, 75 with SCA2, 138 with SCA3 and 72 with SCA6, all of who were enrolled from 2009 to 2012 at 12 US sites. The European Ataxia Study Group (EASG), which includes the EUROSCA team and the Spastic Paraplegia and Ataxia network (SPATAX) team, enrolled 107 patients with SCA1, 146 with SCA2, 122 with SCA3 and 87 with SCA6 in their natural history study at 17 European ataxia referral centres110. For SCA3, the European SCA3/Machado Joseph Disease Initiative (ESMI) has compiled data on 570 participants with SCA3 from 7 multinational investigators, including those in EASG111,112. Collectively, these studies have shown that disease progression data obtained with the SARA are best fitted with a linear model for all genotypes, that SCA1 is the fastest progressing SCA, that SCA3 is the most prevalent SCA and that patients with SCA6 have substantially later onset and slower progression than those with SCAs 1, 2 and 3.

The responsiveness of the SARA score to clinical change is calculated as the standardized response mean (SRM), which is the mean annual change in SARA score divided by the s.d. of the annual change. The mean ± s.d. of the annual change of the SARA total score can be obtained from the CRC-SCA and EUROSCA natural history studies. Using the EUROSCA data, the minimal sample size required to achieve 80% power with an effect size of 50% was estimated to be 142 individuals (71 per group) for SCA1, the fastest progressing SCA110 (FIG. 4). For SCA2, SCA3 and SCA6, the minimal sample size is comparable to or larger than that for SCA1. Data obtained in the CRC-SCA cohort indicate that the sample size would need to be even larger. As such, we will face the challenge of insufficient sample sizes unless we identify drugs with a very large effect size. The rate of progression of each SCA varies in different populations (Supplementary Table 3), and further investigations are needed to determine whether the differences are due to biological disparity or artefacts caused by procedural variation. The required sample size can also be estimated from the difference between the mean progression in SARA score of the placebo group and of the intervention group (estimated on the basis of the hypothetical effects of the intervention)113. This estimation of sample size from placebo groups facilitates the design of double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials.

Fig. 4 |. Sample size estimation for evaluation of drug efficacy in SCA1.

FIGure shows the estimated sample size required for the efficacy of a drug to be tested in a clinical trial of patients with spinocerebellar ataxia 1 (SCA1). Among individuals with common SCAs, patients with SCA1 have shown the fastest progression rate with an annual increase of the Scale for Assessment and Rating of Ataxia (SARA) total score of 1.61 ± 0.41 (mean ± s.e.) in the 2-year Clinical Research Consortium for Studies of Cerebellar Ataxias (CRC-SCA) study and of 2.11 ± 0.12 in the 5-year EUROSCA study. On the basis of the progression data, the sample size needed for two-group interventional trials of 1-year duration was calculated to be P< 0.05 for various effect sizes of the intervention. The estimated sample size per group to achieve 80% power with effect sizes ranging from 20% to 100% is shown. The estimates were calculated separately from the CRC-SCA data (red) and the EUROSCA data (blue).

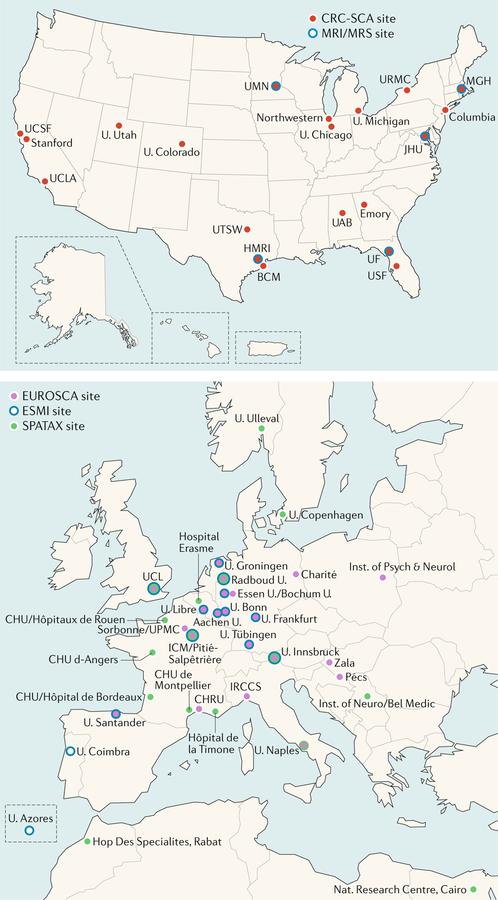

The effect size of potential therapeutic compounds in humans will be difficult to predict even when data from well-performed preclinical studies are available. Thus, identification of a sufficiently large cohort of study participants available for clinical trials is crucially important. The European and US investigators continue to increase the size of respective cohorts and extend the longitudinal data collection. The collaborative approach adopted by the ESMI for SCA3 has now been extended to SCA1 by a new US–European joint leadership initiative that involves multiple large international SCA consortia (FIG. 5). These studies focus on individuals in whom SCA is premanifest or who are at an early stage of the disease114 because convincing data suggest that early-stage neurodegeneration has reversibility that is lost as the disease progresses and cellular dysfunction and cell death increase in the brain115. Investigators in other parts of the world, particularly East Asia and South America, have also shown interest in such a collaborative approach.

FIG. 5 |. Transatlantic SCA consortia.

Twenty US institutions (top panel) are participating in the Clinical Research Consortium for Studies of Cerebellar Ataxias (CRC-SCA). The European consortia (bottom panel) operate in multiple organizations including the German Centre for Neurodegenerative Diseases (DZNE), the European Ataxia Study Group (EASG), the Spastic Paraplegia and Ataxia network (SPATAX) and the European SCA3/Machado Joseph Disease Initiative (ESMI). The US CRC-SCA and these European counterparts are now collaborating in translational and clinical research of spinocerebellar ataxias (SCAs). BCM, Baylor College of Medicine; BRP, Bioengineering Research Partnerships; Charité, Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin; CHRU, Regional Hospital University Centre; CHU, Hospital University Centre; HMRI, Houston Methodist Research Institute; Hop Des, Hopital Des; ICM, Brain & Spine Institute; Inst., Institute; IRCCS, Instituto Di Ricovero e Cura a Carattere Scientifico; JHU, Johns Hopkins University; MGH, Massachusetts General Hospital; MRS, magnetic resonance spectroscopy; Nat., National; Pécs, University of Pécs; Psych & Neurol, Psychiatry and Neurology; U., University or University of; UAB, University of Alabama–Birmingham; UCL, University College London; UCLA, University of California–Los Angeles; UCSF, University of California–San Francisco; UF, University of Florida; UMN, University of Minnesota; UPMC, Université Pierre et Marie Curie; USF, University of South Florida; UTSW, University of Texas Southwestern. The complete list of institutions involved is available in supplementary materials.

Clinical outcome

The primary clinical outcome assessment measure used in most natural history studies of SCAs has been the SARA108, a semi-quantitative scale. Other validated semi-quantitative ataxia scales include the International Cooperative Ataxia Rating Scale (ICARS)116, Modified ICARS (MICARS)117, Brief Ataxia Rating Scale (BARS)118 and Neurological Examination Score for Spinocerebellar Ataxia (NESSCA)119. The SARA has been the scale of choice in clinical studies of SCA within the past few years because it is simple, can be completed in 10 minutes and has been extensively validated and correlated with measures of the quality of life in patients with SCAs120,121. Although composite ataxia measures, such as Composite Cerebellar Functional Severity (CCFS)122, SCA Functional Index (SCAFI)123 and spatiotemporal movement capture of intralimb variability124, provide quantitative data, the responsiveness of these measures has not consistently demonstrated superiority over SARA. A study of 171 patients (including 43 with SCA1, 61 with SCA2, 37 with SCA3 and 30 with SCA6) in the EUROSCA natural history cohort compared the responsiveness of different clinical assessment tools in participants after a 1-year follow-up period. Standardized response means were 0.50 for SARA and −0.48 for SCAFI, and sample size was estimated to be 250 per group for SARA and 275 per group for SCAFI for a two-arm interventional trial aiming at 50% reduction of progression and 80% power125. A similar 1-year follow-up study, conducted in France, of 25 individuals with SCA1, 35 with SCA2 and 58 with SCA3 showed sample size estimates of 175 for SARA and 260 for CCFS126. In 49 patients with SCA2 evaluated with SARA, NESSCA, INAS, SCAFI and CCFS, the only instrument that presented good responsiveness to change in 1 year was SARA121.

Wearable devices to measure ataxia and ataxia-related activities would enable data to be recorded in the daily living environment127,128. Such measures, which result from remarkable advances in data capture and analysis, would provide better information about participants’ performance in variable conditions than the typical ‘snap shot’ obtained during clinic visits and might be more clinically meaningful.

Genetic and environmental modifiers

Several genetic variants have been reported as predictors of the age at onset in patients with SCA3. These variants include the size of the polyQ-coding CAG repeat in the normal allele in eight genes (ATXN1–3, ATXN7, ATXN17, CACNA1A, ATN1 and HTT)129,130, two single-nucleotide polymorphisms (rs709930 and rs910369) in the 3ʹ untranslated region of the ATXN3 gene131, the APOE ε2 allele132, the C9orf72 GGGGCC repeat size133, promoter sequence variation and expression levels of inflammatory genes such as IL1A, IL1B, IL6 and TNF134 and the presence of parkinsonism and/or dystonia135. However, the findings from most of these genetic association studies remain to be confirmed. For example, the association of APOE ε2 with decreased age at onset132 was not confirmed in one study136, and different associations between disease onset and genes that contain polyQ-coding CAG repeats were obtained in populations from Europe129, China130 and Brazil137. Living environment might also affect symptoms and signs of SCAs, as has been suggested in other genetic neurodegenerative disorders. Identification of genetic and environmental predictors will enable the definition of patient subgroups with homogeneous disease evolution and the capture of patients at a high risk of disease, both of which will be crucial to stratification of participants in trials.

Biomarkers

Although the field of translational medicine has broadened the definition of a biomarker, the core definition is a biological characteristic that can be measured and evaluated objectively as an indicator of normal biological processes, pathogenic processes or pharmacological responses to therapeutic intervention138. Biomarkers are crucial for new drug discovery and development and are often used to stratify patient populations to reduce variability of the clinical outcome (FIG. 6). Although reliable molecular biomarkers in body fluids are yet to be discovered for the SCAs, MRI-based biomarkers have shown promising results.

Fig. 6 |. Biomarkers for SCAs.

Diagram shows the stages at which clinical outcome assessment measures and biomarkers are expected to have utility in a hypothetical gene-silencing trial of a polyglutamine (polyQ) spinocerebellar ataxia (SCA) in which a patient cohort with early and premanifest disease is targeted. Clinical outcome assessment, genetic markers (for example, size of CAG triplet repeat and other modifiers of age of onset) and MRI or magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) markers might facilitate the selection of patients with minimal cerebral involvement and enable premanifest enrolment of patients who already show cerebral changes. Measures of the disease protein in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) are being developed to monitor target engagement in those who have been allocated to a gene-silencing intervention. Use of a PET tracer that specifically binds to polyQ repeats could provide direct evidence of clearance of the mutant protein or aggregates from the brain195. Finally, MRI and MRS markers are expected to aid treatment monitoring as secondary outcome measures that supplement the primary clinical outcome assessment measures. Furthermore, MRI and MRS markers might also serve as safety markers to ensure that the treatment does not exacerbate the cerebral pathology. The biomarkers shown are not intended to be comprehensive and need further development and/or validation, particularly in the premanifest and early disease stages, for the proposed uses in trials. ATXN, ataxin; SARA, Scale for Assessment and Rating of Ataxia.

Imaging biomarkers

As in other neurodegenerative conditions, clinical outcome assessment measures are the primary outcome measures in clinical trials of SCAs and are likely to remain so for the foreseeable future. However, use of clinical outcome assessment measures to assess whether therapies slow disease progression in the SCAs is challenging because of their slow progression and phenotypic variability and because they require long clinical trials with large sample sizes (FIG. 4). Clinical outcome assessment measures also lack sensitivity in the earliest stages of disease, including premanifest stages when neuroprotective agents are likely to be most effective, and usually have poor test–retest reliability139. Consequently, although such measures are an essential component of any SCA treatment trial, they should be supplemented with non-invasive neuroimaging to directly assess treatment effects on the brain. Validated imaging biomarkers of CNS pathology can contribute to patient stratification, in combination with genotypic, demographic and clinical outcome assessment data, to enable the individuals most likely to benefit from prospective therapies to be selected (FIG. 6). Validated imaging biomarkers also enable enrolment of mutation carriers at the premanifest stage of SCA by providing evidence of early pathological changes in the brain. Finally, they could enable a reduction in sample sizes if they are approved as primary outcome measures by the FDA or EMA. As detailed earlier in the article, estimated sample sizes range from 71 to 301 patients in each group for a two-arm interventional trial that aims to reduce disease progression by 50% in 1 year in the common SCAs when SARA is used as the outcome measure110,125. On the other hand, 37 patients would be needed per arm of the trial to detect a comparable change by the most sensitive volumetric MRI measure (SRM of −1.3) reported across SCAs140 in 1 year with the same power. This number is in contrast with 78 patients per arm of the trial for SARA (SRM of 0.9) reported in the same cohort140.

Several studies have demonstrated regional metabolic abnormalities and dopaminergic dysfunction in SCAs via PET, including at the premanifest stage114. MRI-based modalities have the advantage of a wider availability than PET and avoid concerns about the repeated radiation exposure associated with PET. Hence, MRI-based modalities have been used in multisite settings and have been more widely validated in SCAs than has PET. In addition, conventional structural MRI has been the standard of care to monitor the characteristic cerebellar and brainstem atrophy in patients with SCAs.

Among the many MRI modalities, morphometric MRI, diffusion MRI and magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) have been evaluated as biomarkers in SCAs by a number of groups worldwide141. In addition, the utility of task-based and resting-state functional MRI142,143 is gathering increased interest for monitoring of functional abnormalities.

Regarding macrostructural MRI measures, the EASG group conducted single-site and multisite investigations to establish the sensitivity of volumetric MRI to morphometric alterations in the most common SCAs112,144,145. Morphometric T1-weighted MRI data analysed with a 3D volumetric method and voxel-based morphometry reveal prominent reductions in grey matter and white matter in the cerebellum and brainstem in individuals with SCAs145. Although these macrostructural changes correlate with SARA145, the volumetric measures were shown to be more sensitive to change than SARA in a longitudinal multisite study140, which provides a strong rationale to supplement clinical outcome assessments with these objective, non-invasive MRI markers in trials (FIG. 6).

Regarding microstructural MRI measures, many groups have demonstrated regional damage to white matter in common SCAs via diffusion tensor imaging (DTI)146–151. In cross-sectional investigations, differences in DTI metrics between patients with SCAs and healthy controls were reported in multiple brain regions, including cerebellar peduncles, cerebellum, brainstem and cerebral white matter. Most of these studies also showed correlations between DTI metrics and clinical severity in SCAs. The sensitivity of DTI metrics to progressive changes in SCAs is largely unexplored, except for one report in SCA2 that showed progressive microstructural damage to white matter tracts152. In addition, the standard DTI model could miss subtle alterations in white matter and does not resolve crossing fibres. These limitations can be overcome by more sophisticated diffusion models, such as high angular resolution diffusion imaging153,154, which need to be validated in large patient cohorts in multisite longitudinal settings.

Complementary to these morphometric MRI measures, proton MRS enables non-invasive and regional quantification of endogenous neurochemicals, thereby providing biochemical and metabolic information155. The sensitivity of MRS to neurochemical abnormalities in SCAs has been demonstrated consistently by different groups on the basis of a few metabolites accessible at low magnetic fields156,157. Within the past few years, increased field strength has enabled quantification of neurochemical profiles of up to 15 metabolites. This capability enabled the detection of robust neurochemical alterations, including molecules reflecting neuronal loss or dysfunction (such as N-acetylaspartate and glutamate) and gliosis (such as myo-inositol), among differences in other metabolites, in the cerebella and brainstems of patients with SCAs158–161. Similar to morphometric measures, the neurochemical alterations measured by MRS correlated with SARA158,159,161 but were more sensitive to change than SARA in a longitudinal 3T MRI study162. MRS biomarkers were further validated in animal models of SCA and were shown to be sensitive to the progression163 and reversal164,165 of SCA1 pathology. Neurochemical abnormalities were detected in the animals at the pre-symptomatic stage163 and before the appearance of gross histopathological changes166. Importantly, MRS detected treatment effects in a conditional transgenic SCA1 mouse model with the same sensitivity and specificity as invasive outcome measures and had higher sensitivity and specificity than standard motor behavioural assessment165. Finally, MRS measures were demonstrated to be reproducible within site167 and between sites168,169, which is crucial for utility in future multisite trials.

In light of mounting evidence that argues for administration of therapies in the earliest stages of neurodegeneration115, the sensitivity of MRI measures to premanifest abnormalities has been investigated in patients with SCAs. Although conventional MRI has limited sensitivity at the premanifest stage170,171, sophisticated analyses of MRI structural data that use volumetry and voxel-based morphometry confer sensitivity to early changes. A large multisite EASG study (RISCA) of individuals at risk of SCA (with SARA < 3) showed substantial grey matter loss in the brainstem and cerebellum in individuals with an ATXN1 or ATXN2 mutation and showed a loss of brainstem volume in individuals carrying an ATXN2 mutation111. In addition, the feasibility of detecting premanifest abnormalities with MRS and diffusion MRI has been demonstrated151,158,170,172. Notably, neurochemical abnormalities were detectable by MRS in a small cohort of premanifest carriers of common SCA-causative mutations whose estimated disease onset was within 10 years, showing that such changes may be detected up to 10 years before onset of ataxia158.

In summary, numerous studies have demonstrated the sensitivity of biomarkers on MRI and MRS to cerebral changes in patients with SCAs, as well as their correlations with disease severity112,140,144–149,158–161,173. Furthermore, morphological MRI and MRS have shown abnormalities in premanifest carriers of SCA-causative mutations111,158. However, further studies must validate the capability of these modalities to predict disease onset in premanifest individuals, to facilitate participant selection for trials and to enable disease progression to be monitored in early-stage patients in multicentre longitudinal settings.

Biofluids and other biomarkers

Biofluid biomarkers are attractive because they are generally less expensive and are potentially easier to access than imaging biomarkers. Although the genetic mutation is the definitive diagnostic biomarker in SCAs, useful body fluid biomarkers for disease activities and disease progression are yet to be developed. CSF levels of tau174, indices of oxidative stress in serum175, serum cytokines176, serum level of glutathione S-transferase177 and circulating plasma DNA level178 are altered in some SCAs. However, these measures have not proved to be useful in clinical trials owing to insufficient specificity or sensitivity for, or limited correlations with, target disease measures. In the past few years, SCA consortia have initiated the search for body fluid biomarkers via transcriptomics, proteomics and investigations of molecules of particular interest in CSF, plasma, serum, exosomes and peripheral cells. Among these markers, the CSF level of ataxin 1 (ATXN1), ATXN2, ATXN3, ATXN7 and other SCA disease proteins that possess toxic gain-of-function properties is considered to be a promising biomarker for monitoring the response to nucleotide-based gene-silencing therapeutic approaches such as ASOs or RNAi (FIG. 6). Other preliminary biomarker studies in SCAs include the frequency of micronuclei in buccal cells179, retinal nerve layer thinning on optical coherence tomography180,181, various measures of CNS function (including cognition182, eye motility183–188, rapid eye movement (REM) sleep and other sleep-related functions189–191), peripheral nerve electrophysiological measures192 and quantitative measures of gait and other motor activities184,193,194. However, further studies are needed to determine the utility of these potential biomarkers.

The importance of stringent adherence to sample and data acquisition and processing protocols when using biomarkers cannot be overemphasized. Standard operating procedures for sample collections are essential and should be based on careful consideration of the stability of biomarker molecules, the nature of assays to be used, the condition of the patient at the time of sample or data acquisition and the circumstances in which the sample is collected.

Conclusions

SCAs are autosomal dominant degenerative disorders that primarily affect the cerebellum and its efferent and afferent pathways. Although clinical characteristics can help to guide physicians towards the correct diagnosis, the diagnosis of SCAs ultimately depends on genetic testing. DNA testing technologies have rapidly improved with NGS technologies although challenges remain, especially in repeat-expansion disorders. Although currently no symptomatic or disease-modifying drugs for SCAs have been approved by the FDA or the EMA, promising candidate drugs are being developed that are based on a strong scientific premise and rigorous preclinical studies. However, SCAs are rare diseases, and clinical trials for these drugs face challenges. Strategies to ensure the feasibility of scientifically sound clinical trials for SCAs include the identification or development of drugs with a large effect size, establishment of sufficiently large cohorts of individuals with SCAs, characterization of cohorts for natural history of the disease, development of responsive clinical outcome assessment measures, identification of disease modifiers to enable refinement of study participant stratification, identification and characterization of biomarkers of disease-related biological changes and adoption of valid clinical designs for small sample sizes. Employment of these strategies should enable decisive clinical trials of new drugs. Given the success of large-scale clinical research efforts in the SCAs in the past few years and continued coordination among ataxia investigators worldwide, we are cautiously optimistic that drugs will be found that are beneficial for those with SCAs.

Supplementary Material

Key points.

Spinocerebellar ataxias (ScAs) are a group of dominantly inherited degenerative disorders that principally involve the cerebellum and its connections.

Insights into the pathogenic mechanisms of many ScAs have suggested promising routes to symptomatic and disease-modifying therapy.

clinical research consortia for ScAs have started international collaborations to share and analyse natural history data.

the Scale for Assessment and rating of Ataxia is the best validated clinical outcome assessment measure, but additional measures should be developed with improved responsiveness to changes that are directly relevant to patients’ lives.

mrI and magnetic resonance spectroscopy have emerged as potentially powerful biomarkers for disease activities and progression, but target engagement biomarkers, especially molecular biomarkers in biofluids, are yet to be developed.

collective efforts in ScA clinical research within the past few years have improved the prospects for eventual successful therapeutic development for the ScAs.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from the US NIH (U01 NS104326–01) to T.A. (contact principal investigator), G.Ö. (multiple principal investigator) and H.L.P. (multiple principal investigator). T.A. is funded by the NIH (R01 NS083564), the National Ataxia Foundation and the Harriet and Joe B. Foster Endowment Fund on spinocerebellar ataxia (SCA) research and is collaborating with Pacific Biosciences on single-molecule real-time sequencing of the expanded SCA10 tandem repeat. G.Ö. receives grant funding from the NIH (R01 NS080816), the National Ataxia Foundation and Takeda Pharmaceuticals on SCA research. The Center for Magnetic Resonance Research is supported by the US National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering grant P41 EB015894 and the US Institutional Center Cores for Advanced Neuroimaging award P30 NS076408. H.L.P.’s work on SCAs is funded by the NIH (R01 NS038712), the National Ataxia Foundation, the Alfred Taubman Medical Research Institute, the University of Michigan Center for the Discovery of New Medicines, Cydan and the SCA Network of Sweden. He collaborates with Ionis Pharmaceuticals on antisense oligonucleotide therapy development for SCA3. The authors thank C. Potvin for helping with manuscript preparation and L. Eberly for assistance with sample size calculations.

Competing interests

T.A. has received honoraria and travel support from Pacific Biosciences. G.Ö. has received funding from Takeda Pharmaceuticals for a spinocerebellar ataxia (SCA) preclinical trial. H.L.P. recently completed a research contract with Ionis Pharmaceuticals for ASO treatments of SCA3.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41582-018-0051-6.

References

- 1.Bird TD in GeneReviews (eds Adam MP et al.) (University of Washington, Seattle, 1998, last updated 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paulson HL, Shakkottai VG, Clark HB & Orr HT Polyglutamine spinocerebellar ataxias-from genes to potential treatments. Nat. Rev. Neurosci 18, 613–626 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klockgether T The clinical diagnosis of autosomal dominant spinocerebellar ataxias. Cerebellum 7, 101–105 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manto MU The wide spectrum of spinocerebellar ataxias (SCAs). Cerebellum 4, 2–6 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giordano I et al. Clinical and genetic characteristics of sporadic adult-onset degenerative ataxia. Neurology 89, 1043–1049 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van de Warrenburg BP et al. EFNS/ENS consensus on the diagnosis and management of chronic ataxias in adulthood. Eur. J. Neurol 21, 552–562 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Menon RP et al. The role of interruptions in polyQ in the pathology of SCA1. PLoS Genet 9, e1003648 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Charles P et al. Are interrupted SCA2 CAG repeat expansions responsible for parkinsonism? Neurology 69, 1970–1975 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Landrian I et al. Inheritance patterns of ATCCT repeat interruptions in spinocerebellar ataxia type 10 (SCA10) expansions. PLoS ONE 12, e0175958 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McFarland KN et al. SMRT sequencing of long tandem nucleotide repeats in SCA10 reveals unique insight of repeat expansion structure. PLoS ONE 10, e0135906 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Opal P & Ashizawa T in GeneReviews (eds Adam MP et al.) (University of Washington, Seattle, 1997, last updated 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Socal MP et al. Intrafamilial variability of Parkinson phenotype in SCAs: novel cases due to SCA2 and SCA3 expansions. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord 15, 374–378 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Modoni A et al. Prevalence of spinocerebellar ataxia type 2 mutation among Italian Parkinsonian patients. Mov. Disord 22, 324–327 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schule B et al. Parkinson’s disease associated with pure ATXN10 repeat expansion. NPJ Parkinsons Dis 3, 27 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choubtum L et al. Analysis of SCA8, SCA10, SCA12, SCA17 and SCA19 in patients with unknown spinocerebellar ataxia: a Thai multicentre study. BMC Neurol 15, 166 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu YR et al. Genetic testing in spinocerebellar ataxia in Taiwan: expansions of trinucleotide repeats in SCA8 and SCA17 are associated with typical Parkinson’s disease. Clin. Genet 65, 209–214 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ross OA et al. Ataxin-2 repeat-length variation and neurodegeneration. Hum. Mol. Genet 20, 3207–3212 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elden AC et al. Ataxin-2 intermediate-length polyglutamine expansions are associated with increased risk for ALS. Nature 466, 1069–1075 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu Z et al. PolyQ repeat expansions in ATXN2 associated with ALS are CAA interrupted repeats. PLoS ONE 6, e17951 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McFarland KN et al. Repeat interruptions in spinocerebellar ataxia type 10 expansions are strongly associated with epileptic seizures. Neurogenetics 15, 59–64 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nibbeling EAR et al. Exome sequencing and network analysis identifies shared mechanisms underlying spinocerebellar ataxia. Brain 140, 2860–2878 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clarke J et al. Continuous base identification for single-molecule nanopore DNA sequencing. Nat. Nanotechnol 4, 265–270 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roberts RJ, Carneiro MO & Schatz MC The advantages of SMRT sequencing. Genome Biol 14, 405 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ilg W et al. Intensive coordinative training improves motor performance in degenerative cerebellar disease. Neurology 73, 1823–1830 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ilg W et al. Consensus paper: management of degenerative cerebellar disorders. Cerebellum 13, 248–268 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miyai I et al. Cerebellar ataxia rehabilitation trial in degenerative cerebellar diseases. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 26, 515–522 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Silva RC et al. Occupational therapy in spinocerebellar ataxia type 3: an open-label trial. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res 43, 537–542 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ilg W et al. Video game-based coordinative training improves ataxia in children with degenerative ataxia. Neurology 79, 2056–2060 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fonteyn EM et al. Gait adaptability training improves obstacle avoidance and dynamic stability in patients with cerebellar degeneration. Gait Posture 40, 247–251 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chang YJ et al. Cycling regimen induces spinal circuitry plasticity and improves leg muscle coordination in individuals with spinocerebellar ataxia. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil 96, 1006–1013 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fonteyn EM et al. The effectiveness of allied health care in patients with ataxia: a systematic review. J. Neurol 261, 251–258 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ihara Y, Takata H, Tanabe Y, Nobukuni K & Hayabara T Influence of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on disease severity and oxidative stress markers in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with spinocerebellar degeneration. Neurol. Res 27, 310–313 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shiga Y et al. Transcranial magnetic stimulation alleviates truncal ataxia in spinocerebellar degeneration. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 72, 124–126 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zu T et al. Recovery from polyglutamine-induced neurodegeneration in conditional SCA1 transgenic mice. J. Neurosci 24, 8853–8861 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Furrer SA et al. Reduction of mutant ataxin-7 expression restores motor function and prevents cerebellar synaptic reorganization in a conditional mouse model of SCA7. Hum. Mol. Genet 22, 890–903 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yamamoto A, Lucas JJ & Hen R Reversal of neuropathology and motor dysfunction in a conditional model of Huntington’s disease. Cell 101, 57–66 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Katsuno M et al. Reversible disruption of dynactin 1-mediated retrograde axonal transport in polyglutamine-induced motor neuron degeneration. J. Neurosci 26, 12106–12117 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sanchez I, Balague E & Matilla-Duenas A Ataxin-1 regulates the cerebellar bioenergetics proteome through the GSK3beta-mTOR pathway which is altered in Spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 (SCA1). Hum. Mol. Genet 25, 4021–4040 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lim J et al. A protein-protein interaction network for human inherited ataxias and disorders of Purkinje cell degeneration. Cell 125, 801–814 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Crespo-Barreto J, Fryer JD, Shaw CA, Orr HT & Zoghbi HY Partial loss of ataxin-1 function contributes to transcriptional dysregulation in spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 pathogenesis. PLoS Genet 6, e1001021 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Matilla-Duenas A, Goold R & Giunti P Clinical, genetic, molecular, and pathophysiological insights into spinocerebellar ataxia type 1. Cerebellum 7, 106–114 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Busch A et al. Mutant huntingtin promotes the fibrillogenesis of wild-type huntingtin: a potential mechanism for loss of huntingtin function in Huntington’s disease. J. Biol. Chem 278, 41452–41461 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cattaneo E et al. Loss of normal huntingtin function: new developments in Huntington’s disease research. Trends Neurosci 24, 182–188 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Evers MM, Toonen LJ & van Roon-Mom WM Ataxin-3 protein and RNA toxicity in spinocerebellar ataxia type 3: current insights and emerging therapeutic strategies. Mol. Neurobiol 49, 1513–1531 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tsoi H & Chan HY Expression of expanded CAG transcripts triggers nucleolar stress in Huntington’s disease. Cerebellum 12, 310–312 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Samaraweera SE et al. Modeling and analysis of repeat RNA toxicity in Drosophila. Methods Mol. Biol 1017, 173–192 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shieh SY & Bonini NM Genes and pathways affected by CAG-repeat RNA-based toxicity in Drosophila. Hum. Mol. Genet 20, 4810–4821 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li LB, Yu Z, Teng X & Bonini NM RNA toxicity is a component of ataxin-3 degeneration in Drosophila. Nature 453, 1107–1111 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moseley ML et al. Bidirectional expression of CUG and CAG expansion transcripts and intranuclear polyglutamine inclusions in spinocerebellar ataxia type 8. Nat. Genet 38, 758–769 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ikeda Y, Daughters RS & Ranum LP Bidirectional expression of the SCA8 expansion mutation: one mutation, two genes. Cerebellum 7, 150–158 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li PP et al. ATXN2-AS, a gene antisense to ATXN2, is associated with spinocerebellar ataxia type 2 and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann. Neurol 80, 600–615 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sopher BL et al. CTCF regulates ataxin-7 expression through promotion of a convergently transcribed, antisense noncoding RNA. Neuron 70, 1071–1084 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zu T et al. Non-ATG-initiated translation directed by microsatellite expansions. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 260–265 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ishiguro T et al. Regulatory role of RNA chaperone TDP-43 for RNA misfolding and repeat-associated translation in sCA31. Neuron 94, 108–124 e7 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sellier C et al. Translation of expanded CGG repeats into FMRpolyG is pathogenic and may contribute to fragile X tremor ataxia syndrome. Neuron 93, 331–347 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Krans A, Kearse MG & Todd PK Repeat-associated non-AUG translation from antisense CCG repeats in fragile X tremor/ataxia syndrome. Ann. Neurol 80, 871–881 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Scoles DR et al. Repeat associated non-AUG translation (RAN translation) dependent on sequence downstream of the ATXN2 CAG repeat. PLoS ONE 10, e0128769 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ashizawa T & Wells RD Genetic Instabilities and Neurological Disorders (Elsevier, Burlington, 2006). [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stella S, Alcon P & Montoya G Class 2 CRISPR-Cas RNA-guided endonucleases: Swiss Army knives of genome editing. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 24, 882–892 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Murugan K, Babu K, Sundaresan R, Rajan R & Sashital DG The revolution continues: newly discovered systems expand the CRISPR-Cas toolkit. Mol. Cell 68, 15–25 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Monteys AM, Ebanks SA, Keiser MS & Davidson BL CRISPR/Cas9 editing of the mutant Huntingtin allele in vitro and in vivo. Mol. Ther 25, 12–23 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cornu TI, Mussolino C & Cathomen T Refining strategies to translate genome editing to the clinic. Nat. Med 23, 415–423 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Maxwell KL The anti-CRISPR story: a battle for survival. Mol. Cell 68, 8–14 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fiszer A & Krzyzosiak WJ Oligonucleotide-based strategies to combat polyglutamine diseases. Nucleic Acids Res 42, 6787–6810 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Keiser MS, Kordasiewicz HB & McBride JL Gene suppression strategies for dominantly inherited neurodegenerative diseases: lessons from Huntington’s disease and spinocerebellar ataxia. Hum. Mol. Genet 25, R53–R64 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Miyazaki Y, Du X, Muramatsu S & Gomez CM An miRNA-mediated therapy for SCA6 blocks IRES-driven translation of the CACNA1A second cistron. Sci. Transl Med 8, 347ra94 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tabrizi S et al. Effects of IONIS-HTTRx in patients with early Huntington’s disease, results of the first HTT-lowering drug trial. Neurology 90 (Suppl. 15), CT.002 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zoghbi HY & Orr HT Pathogenic mechanisms of a polyglutamine-mediated neurodegenerative disease, spinocerebellar ataxia type 1. J. Biol. Chem 284, 7425–7429 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Park J et al. RAS-MAPK-MSK1 pathway modulates ataxin 1 protein levels and toxicity in SCA1. Nature 498, 325–331 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]