Abstract

Whereas carbohydrates and lipids are stored as glycogen and fat, there is no analogous inert storage form of protein. Therefore, continuous adjustments in feeding behavior are needed to match amino acid supply to ongoing physiologic need. Neuroendocrine mechanisms facilitating this behavioral control of protein and amino acid homeostasis remain unclear. The hepatokine fibroblast growth factor-21 (FGF21) is well positioned for such a role, as it is robustly secreted in response to protein and/or amino acid deficit. In this study, we tested the hypothesis that FGF21 feeds back at its receptors in the nervous system to shift macronutrient selection toward protein. In a series of behavioral tests, we isolated the effect of FGF21 to influence consumption of protein, fat, and carbohydrate in male mice. First, we used a three-choice pure macronutrient-diet paradigm. In response to FGF21, mice increased consumption of protein while reducing carbohydrate intake, with no effect on fat intake. Next, to determine whether protein or carbohydrate was the primary-regulated nutrient, we used a sequence of two-choice experiments to isolate the effect of FGF21 on preference for each macronutrient. Sweetness was well controlled by holding sucrose constant across the diets. Under these conditions, FGF21 increased protein intake, and this was offset by reducing the consumption of either carbohydrate or fat. When protein was held constant, FGF21 had no effect on macronutrient intake. Lastly, the effect of FGF21 to increase protein intake required the presence of its co-receptor, β-klotho, in neurons. Taken together, these findings point to a novel liver→nervous system pathway underlying the regulation of dietary protein intake via FGF21.

Energy from food derives from three macronutrient forms: carbohydrates, fats, and proteins. During the absorptive state, ingested carbohydrates and fats are stored in the body as glycogen or triglycerides and can later be mobilized to provide fuel during the postabsorptive state. In contrast, there is no analogous inert storage form of protein. Thus, protein is used sparingly as fuel, and continuous adjustments in feeding behavior are needed to ensure an adequate supply of amino acids for dynamic use, maintenance, and repair (1). Considerable evidence supports a behavioral regulation of protein intake, but mechanisms that underlie such behaviors are largely undescribed (1–3).

Fibroblast growth factor-21 (FGF21) was identified as a secreted protein from mouse liver and was cloned in 2000, and an abundance of studies detailing its metabolic benefits have appeared since then (4–7). However, a clear understanding of the physiological and/or nutritional contexts regulating FGF21 secretion has been elusive. Plasma FGF21 is modestly induced by fasting (8), or by maintenance on a (low-protein) ketogenic diet (9–11) in mice and rats. As a result, it was initially characterized as a “starvation hormone” that facilitates aspects of the adaptive starvation response. However, neither fasting nor a ketogenic diet reliably increases circulating FGF21 in humans (6). New findings suggest a more nuanced role. Recent evidence supports that FGF21 is induced by a deficit of various individual essential and nonessential amino acids (12–15) or by a deficit of total dietary protein, rather than by caloric restriction per se, in both rodents and in humans (15–17). Surprisingly, FGF21 is also induced by macronutrient excess. In 2009, Sánchez et al. (18) reported that, whereas plasma FGF21 was modestly increased after a 24-hour fast, refeeding with isocaloric amounts of either carbohydrate or fat caused a substantial additional increase. They concluded that FGF21 indicates an “unbalanced nutritional situation.” In agreement with this, current work now demonstrates that FGF21 is also induced up to 10-fold in ad libitum–fed rodents and humans after consuming an excess of simple sugars relative to other dietary options (19–22).

To resolve this apparent paradox, Simpson and colleagues (2) used the multidimensional geometric framework model to distinguish the roles of macronutrients and total energy intake on FGF21 levels in 853 mice maintained on 25 different diets of varying macronutrient content and caloric density. They concluded that plasma FGF21 increases in response to low dietary protein intake and, most strongly, when low protein intake was coupled with high carbohydrate intake. Thus, FGF21 is an endocrine signal of relative dietary protein “dilution,” characterized by a low dietary protein/carbohydrate (P/C) ratio. Recent findings from Rose and colleagues (15) and Morrison and colleagues (17) agree with this interpretation. Likewise, when we sampled from mice eating isocaloric diets that contain 22% fat and either 18% protein and 60% carbohydrates (normal P/C ratio) or 4% protein and 74% carbohydrates (low P/C ratio), plasma FGF21 was increased ∼40- to 60-fold in low P/C ratio mice compared with normal P/C ratio mice (23).

Circulating FGF21 crosses the blood–brain barrier to activate neurons in the brainstem and hypothalamus known to be important in the regulation of energy balance and feeding behavior (21, 24–26). Therefore, it is well situated to act as a neuroendocrine signal, eliciting compensatory behavioral changes that increase the relative intake of dietary protein. Consistent with this, in a recent genome-wide association study, variants located near the Fgf21 locus associated with decreased protein (and increased carbohydrate) intake (27). The current study tested the hypothesis that FGF21 acts via its receptors in the nervous system to restore appropriate macronutrient balance, by increasing protein intake at the expense of carbohydrate and/or fat.

Materials and Methods

Animals

All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Care and Use Committee of the University of California, Davis. Age-matched adult male C57BL/6J mice (n = 8 to 20 per group) were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Sacramento, CA) or were bred in-house, for up to two generations removed from the founders. Mice lacking β-klotho in neurons (KlbΔSynCre) were generated by crossing β-klotho-floxed mice (gift from Steven Kliewer, UT Southwestern Medical Center) with mice expressing Cre-recombinase under the Synapsin-I promoter (catalog no. 003966, The Jackson Laboratory). To avoid known germline recombination, the Cre gene was passed only through females (28). As an initial validation of this line, we extracted mRNA from whole hypothalamus of neuron-specific β-klotho-null mice (n = 3, KlbΔSynCre) and littermate controls (n = 5, Klbflox/flox/Cre−), and using quantitative RT-PCR (see methods described in this section), we determined that β-klotho (Klb) expression was reduced by 69% in the KlbΔSynCre mice (100 ± 7.7 vs 31 ± 10.1, t test, P < 0.05). Male mice were used in all of the experiments and were singly housed on a 12-hour light/12-hour dark cycle in a temperature-controlled (20°C to 22°C) and humidity-controlled vivarium with ad libitum access to food and water.

Diets

Standard chow diet, used for the experiments shown in Fig. 1, was obtained from Harlan Laboratories/Envigo (Madison, WI; catalog no. 5008). Sucrose was from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) and was dissolved in regular tap water. Single macronutrient diets from Harlan Laboratories/Envigo, used for the experiments shown in Fig. 2, contained >99% of total calories derived from protein, carbohydrates, or fat, respectively, as in Ryan et al. (29) and Chambers et al. (30) (TD.02523, TD.02521, and TD.02522). Purified, pelleted diets used for the experiments shown in Figs. 3–6 (D11092301, D11051801, D18040303, D18040304, and D18061811) were manufactured by Research Diets (New Brunswick, NJ). The pelleted diets were based on the AIN-93 rodent diet formula (31) in which protein is derived from casein and supplemented with cystine. Full nutritional details can be found in Tables 1 and 2.

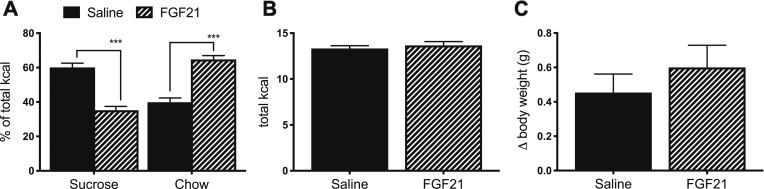

Figure 1.

FGF21 decreases sucrose intake and increases chow intake. In a two-bottle test, mice were offered 10% sucrose vs water, together with ad libitum chow. (A) FGF21 (1 mg/kg bw, IP) reduced sucrose intake and increased chow intake [P (diet × treatment) < 0.001; Tukey post hoc test, ***P < 0.001]. There was no effect of FGF21 on (B) total caloric intake or (C) body weight change. Data are shown as mean ± SEM; n = 9 to 11 mice per group.

Figure 2.

FGF21 increases protein intake and decreases carbohydrate intake. In a three-choice pure macronutrient selection paradigm, mice were offered free access to pure protein (PRO; casein), carbohydrate (CHO; 33% sucrose and 67% corn starch), and FAT (vegetable shortening) diets. We injected 1 mg/kg bw FGF21 or saline IP and measured overnight food intake. (A) FGF21 increased PRO intake and decreased CHO intake [P (diet × treatment) < 0.01; Tukey post hoc test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01). There was no effect of FGF21 on (B) total caloric intake or (C) body weight change. Data are shown as mean ± SEM; n = 20 mice per group.

Figure 3.

FGF21 increases protein intake and decreases carbohydrate intake. (A) In a first cohort of mice, we measured circulating hFGF21 concentrations following an IP injection of 0.1 mg/kg. A second cohort of mice was offered simultaneous access to two pelleted diets matched for dietary fat content (22%), whereas the protein/carbohydrate ratio varied (4%:74% or 18%:60%). After establishing a baseline intake for 1 wk, mice were divided into two groups that were well matched for (B) total caloric and (C) macronutrient intake. (E) Next, we delivered FGF21 (0.2 mg/kg/d, IP) or saline for 7 d. FGF21 elicited an increase in the consumption of dietary protein, offset by a decrease in carbohydrate intake. In agreement with its established role to increase energy expenditure, FGF21 also (D) increased total caloric intake and (F) induced body weight loss. Data are shown as mean ± SEM; n = 3 to 5 mice per treatment per time point for (A), and n = 15 mice per group for (B)–(F). All comparisons were made by a t test: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. PRO, protein.

Figure 6.

Nervous system β-klotho is necessary for the effects of FGF21 on protein intake. Mice lacking the FGF21 coreceptor, β-klotho, in neurons (KlbΔSynCre) and littermate controls (Klbflox/ flox) were offered a choice between two pelleted diets matched for dietary fat content (22%), whereas the protein/carbohydrate ratio varied (4%:74% or 18%:60%). After establishing a baseline intake for 1 wk, mice of each genotype were divided into two groups that were well matched for (A) caloric and (C) macronutrient intake (n = 5 to 7 per group). Next, we delivered FGF21 (0.2 mg/kg/d, IP) or saline for 7 d. (D) As expected, the effect of FGF21 on macronutrient intake depended on genotype [P (treatment × genotype) < 0.05]. Only the Klbflox/flox mice significantly altered diet selection relative to baseline by increasing protein intake in response to FGF21 (Wilcoxon signed-rank test, #P < 0.05). (B) FGF21 also elicited a significant increase in caloric intake, which did not depend on genotype [P (treatment) < 0.05], and (E) there was no effect of either genotype or treatment on body change. (F) Lastly, we confirmed knockdown by quantitative RT-PCR (t test, ***P < 0.001). iBAT, intrascapular brown adipose tissue; iWAT, inguinal white adipose tissue; PRO, protein.

Table 1.

Diet Composition for Three-Choice Diets

| Ingredient, g/kg | Protein Only (TD.02523) | Carbohydrate Only (TD.02521) | Fat Only (TD.02522) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Casein | 871.7 | ||

| dl-Methionine | 1.1 | 1.1 | 2.0 |

| Cellulose | 87.0 | 87.0 | 169.0 |

| Mineral mix, AIN-76 (170915) | 30.7 | 30.7 | 59.5 |

| Mineral mix, AIN-76A (40077) | 7.7 | 7.7 | 14.9 |

| Choline chloride | 1.8 | 1.8 | 3.4 |

| Corn starch | 581.1 | ||

| Sucrose | 290.6 | ||

| Vegetable shortening, hydrogenated | 751.2 | ||

| kcal/g | 3.2 | 3.3 | 6.9 |

Table 2.

Diet Composition for Pelleted Diets

| Ingredient, g | D11092301 | D11051801 | D18040303 | D18040304 | D18061811 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Casein | 50 | 200 | 50 | 206 | 206 |

| l-Cystine | 0.75 | 3 | 0.75 | 3 | 3 |

| Corn starch | 485 | 375.7 | 176.75 | 180 | 289.2 |

| Maltodextrin 10 | 150 | 125 | 60 | 60 | 125 |

| Sucrose | 107.0777 | 107.0777 | 107.0777 | 107.0777 | 107.0777 |

| Cellulose | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| Soybean oil | 25 | 25 | 69.25 | 53.4 | 34 |

| Lard | 75 | 75 | 207.75 | 160.1 | 102.1 |

| Mineral mix S10022G | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mineral mix S10022C | 3.5 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 3.5 |

| Calcium carbonate | 8.7 | 12.495 | 8.7 | 8.7 | 8.7 |

| Calcium phosphate, dibasic | 5.3 | 0 | 5.3 | 5.15 | 5.15 |

| Potassium citrate, 1 H2O | 2.4773 | 2.4773 | 2.4773 | 6.72 | 6.72 |

| Potassium phosphate, monobasic | 6.86 | 6.86 | 6.86 | 1.53 | 1.53 |

| Sodium chloride | 2.59 | 2.59 | 2.59 | 2.59 | 2.59 |

| Vitamin mix V10037 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Choline bitartrate | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 |

| FD&C yellow dye no. 5 | 0 | 0.05 | 0 | 0.025 | 0.025 |

| FD&C red dye no. 40 | 0.05 | 0 | 0 | 0.025 | 0 |

| FD&C blue dye no. 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.05 | 0 | 0.025 |

| kcal/g | 4.15 | 4.082 | 5.35 | 4.75 | 4.27 |

| Protein, g% | 4.569 | 17.88 | 5.89 | 21.39 | 19.22 |

| Carbohydrate, g% | 81.437 | 66.72 | 52.91 | 47.31 | 60.70 |

| Fat, g% | 10.154 | 9.99 | 36.28 | 24.87 | 14.21 |

| Protein, kcal% | 4.38 | 17.52 | 4.38 | 18.03 | 18.03 |

| Carbohydrate, kcal% | 73.6 | 60.46 | 34.62 | 34.94 | 51.99 |

| Fat, kcal% | 22.021 | 22.021 | 61.00 | 47.03 | 29.97 |

| Calcium, g | 5.06 | 5.06 | 5.06 | 5.06 | 5.06 |

| Phosphorus, g | 3.17 | 3.17 | 3.17 | 3.17 | 3.17 |

| Potassium, g | 3.6 | 3.6 | 3.6 | 3.6 | 3.6 |

| Folate, g | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Omega-6 fatty acids | 15.10 | 15.10 | 41.83 | 32.25 | 20.54 |

| Omega-3 fatty acids | 3 | 3 | 8.31 | 6.41 | 4.08 |

| Omega-6/omega-3 ratio | 5.03 | 5.03 | 5.03 | 5.03 | 5.03 |

Abbreviation: FD&C, food, drug, and cosmetic.

FGF21

Endotoxin-free, recombinant human FGF21 (hFGF21; ProSpecBio, Rehovot, Israel) (32) was first dissolved in H2O, according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and was further diluted in 0.9% sterile saline for injection (1 mg/kg acutely, or 0.1 mg/kg twice daily, given just after the onset of light and again just before the onset of dark during a 12-hour light/12-hour dark cycle).

To determine plasma hFGF21 concentration in C57BL/6 mice, following a single IP injection (0.1 mg/kg), we collected blood at 0, 1, 4, and 10 hours, which was stored on ice. Plasma was separated by centrifugation for 30 minutes at 3000g at 4°C and stored at −80°C until later use. hFGF21 was measured using a commercially available ELISA kit following the manufacturer’s protocol (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN; catalog no. DF2100) (33). The lower limit of detection for this assay is 4.67 pg/mL.

Gene expression by quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from hypothalamus (see above), whole brain (Fig. 6F), and adipose depots (Fig. 6F) using the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Germantown MD), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was synthesized using a high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Life Technologies/Thermo Fisher, Carlsbad, CA), and gene expression analysis was performed, in duplicate, using TaqMan gene expression assays. Expression of Klb (Mm00473122_m1) was normalized to the housekeeping genes Rn18s (Mm04277571_s1) and Ppib (Mm00478295_m1) by the 2−ΔΔCT method.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA) and SigmaStat (Systat Software, San Jose, CA) by a two-tailed t test, Wilcoxon signed-rank test, or ANOVA, as indicated. Planned comparisons were made using a Tukey honestly significant difference test. Data are plotted as means ± SEM unless otherwise noted.

Results

Sucrose vs water: two-choice test

Recent evidence supports that FGF21 is a negative regulator of simple sugar intake and sweet taste preference. In independent studies, Kliewer and colleagues (20) and Potthoff and colleagues (21) reported that FGF21 reduces the preference for sucrose solution vs water in a two-bottle choice test. For these experiments, however, it was not clear whether total caloric intake was also changed, or whether reduced energy intake from sucrose was offset by compensatory changes in the consumption of other dietary macronutrients. To explicitly test this, we provided adult male mice simultaneous free access to two 50-mL sippers containing 10% sucrose vs water, and with ad libitum access to regular chow. Following a 48-hour acclimation period, we administered 1 mg/kg body weight (bw) of FGF21 by IP injection, as in Kliewer and colleagues (20) and Potthoff and colleagues (21), or saline, just prior to lights out. Water, 10% sucrose, and chow intakes were measured the following morning, 2 hours into the light period.

Consistent with prior reports, we find that FGF21 reduced the consumption of sucrose vs water in the two-bottle test. FGF21-treated mice consumed fewer total kilocalories from sucrose compared with saline-treated controls. This was offset by increased consumption of normal chow [Fig. 1A, two-way ANOVA, P (diet × treatment) < 0.001; P < 0.001 by Tukey post hoc test] such that there was no difference in total caloric intake (Fig. 1B). There was no effect of FGF21 on body weight following this acute FGF21 injection (Fig. 1C). Taken together, we conclude that FGF21 decreases sucrose intake while simultaneously increasing consumption of other available dietary options.

Single macronutrient diets: three-choice test

To explicitly determine macronutrient tradeoffs in response to FGF21, we used a standard three-choice macronutrient selection paradigm, in which mice can freely distribute food intake between three single macronutrient diets. Dietary protein was from casein supplemented with methionine (TD.02523); dietary fat was from vegetable shortening (TD.02521); and dietary carbohydrate was one-third sucrose and two-thirds cornstarch (TD.02522) (see Table 1 for details). Following a 4-day acclimation period, we delivered FGF21 (1 mg/kg bw IP) or saline just before lights out and measured food intake overnight. We observed a significant increase in dietary protein intake, coupled with a significant decrease in carbohydrate intake [Fig. 2A, P (diet × treatment) < 0.01; P < 0.05, Tukey post hoc test]. There was no difference in total caloric intake (Fig. 2B), and there was no significant effect of FGF21 on body weight (Fig. 2C). We conclude that FGF21 decreases carbohydrate intake, and this is offset by increased consumption of dietary protein.

Pelleted diets: series of two-choice tests

In three separate cohorts of mice, we completed a series of experiments in which individuals were allowed to choose between two pelleted diets that were matched for one of the three macronutrients, whereas the other two macronutrients varied. To isolate the contribution of carbohydrates per se vs simple sugars and/or sweet taste, sucrose content was held constant for all of the pairwise diet choices discussed below. Detailed descriptions of the diets can be found in Table 2. For these chronic experiments, FGF21 was delivered at 0.1 mg/kg, twice daily. This dose was chosen according to a previous study (34) demonstrating that it is effective to induce weight loss and improve glucose tolerance in diet-induced obese mice. To determine the plasma concentration of hFGF21 resulting from this dose, we collected blood from mice at 0, 1, 2, 4, and 10 hours after its IP injection. Circulating concentrations reached 65.7 ng/mL hFGF21 at 1 hour after the injection. By 4 hours, plasma hFGF21 was comparable to the levels we and others observe during dietary protein dilution (23) (7.86 ng/mL), and by 10 hours no hFGF21 was detectible. As expected, we did not detect hFGF21 from saline-injected mice at any time point (Fig. 3A).

In the first of the two-choice experiments mice were offered simultaneous access to two diets that were matched at 22% fat (iso-FAT), together with 18% protein and 60% carbohydrates or 4% protein and 74% carbohydrates [diets as in Maida et al. (15), Laeger et al. (17), and Larson et al. (23); D11051801 and D11092301, Table 2]. First, mice were maintained on the two diets for 1 week to establish a baseline ratio of macronutrient intake. Next, mice were divided into two treatment groups matched for baseline caloric and macronutrient intake, expressed here as percentage of total kilocalories from protein (Fig. 3B and 3C). Lastly, we delivered FGF21 (0.1 mg/kg/d, twice daily, IP) and measured intake of the two diets for 7 days. Chronic administration of FGF21 induces weight loss via increased energy expenditure, and this is often accompanied by increased caloric intake (35). In agreement with this, mice treated for 7 days with FGF21 lost weight (Fig. 3F, t test, P < 0.05) and ate more calories (Fig. 3D, t test, P < 0.01) compared with saline-treated controls. Moreover, as we observed during our three-diet choice test (Fig. 2), mice treated for 7 days with FGF21 significantly increased the percentage of kilocalories consumed from dietary protein (and decreased the percentage of kilocalories consumed from carbohydrates), whereas saline-treated mice did not change their macronutrient consumption (Fig. 3E, t test, P < 0.01).

In the second such experiment, mice were offered simultaneous access to two diets that were matched at 35% carbohydrate (iso-CHO), together with 18% protein and 47% fat or 4% protein and 61% fat (D18040304 and D18040303, Table 2). Mice were maintained on the two diets for 1 week to establish a baseline, as above. Next, mice were divided into two treatment groups matched for baseline caloric (Fig. 4A) and macronutrient intake, expressed here as percentage of total kilocalories from protein (Fig. 4C). Finally, we delivered FGF21 (0.1 mg/kg, twice daily, IP) and measured intake of the two diets for 7 days. We observed a decrease in total caloric intake during the 7 days of treatment (Fig. 4B), relative to baseline (Fig. 4A), for both treatment groups. We attribute this to mild stress associated with increased handling and the twice-daily injections, together with decreasing novelty of the higher fat diets. Mice treated for 7 days with FGF21 significantly increased the percentage of kilocalories consumed from dietary protein (and decreased the percentage of kilocalories consumed from fat). In contrast, saline-treated mice did not change their macronutrient consumption (Fig. 4D, t test, P < 0.001). FGF21-treated mice lost weight relative to saline-treated controls (Fig. 4E, t test, P < 0.001) despite no effect on caloric intake (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

FGF21 increases protein intake and decreases fat intake. Mice were offered simultaneous access to two pelleted diets matched for dietary carbohydrate content (35%), whereas the protein/fat ratio varied (4%:61% or 18%:47%). After establishing a baseline intake for 1 wk, mice were divided into two groups that were well matched for (A) caloric and (C) macronutrient intake. (D) Next, we delivered FGF21 (0.2 mg/kg/d, IP) or saline for 7 d. FGF21 elicited an increase in the consumption of dietary protein, offset by a decrease in fat intake. In agreement with its established role to increase energy expenditure, FGF21 also (E) induced body weight loss, despite (B) no significant effect on caloric intake. Data are shown as mean ± SEM; n = 8 to 9 mice per group. All comparisons were made by a t test: ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. PRO, protein.

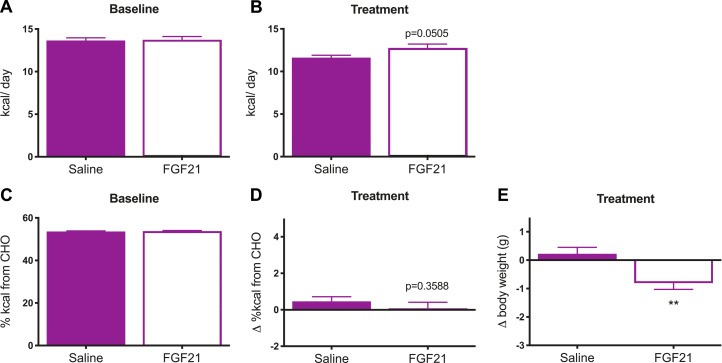

In the third such experiment, mice were offered simultaneous access to two diets that were matched at 18% protein (iso-PRO), together with 60% carbohydrate and 22% fat or 52% carbohydrate and 30% fat (D11051801 and D18061811). Mice were maintained on the two diets for 1 week to establish a baseline, as above. Next, mice were divided into two treatment groups matched for baseline caloric (Fig. 5A) and macronutrient intake, expressed here as percentage of total kilocalories from carbohydrate (Fig. 5C). Finally, we delivered FGF21 (0.1 mg/kg, twice daily, IP) and measured intake of the two diets for 7 days. FGF21 increased caloric intake (Fig. 5B, t test, P = 0.0505), but there was no significant effect of FGF21 on macronutrient selection in this experiment (Fig. 5D, t test, P = 0.3588). Again, consistent with the literature, FGF21-treated mice lost weight relative to saline-treated controls (Fig. 5E, t test, P < 0.01).

Figure 5.

FGF21 does not change macronutrient intake when dietary protein is held constant. In this experiment, mice were offered simultaneous access to two pelleted diets matched for dietary protein content (18%), whereas the carbohydrate/fat ratio varied (60%:22% or 52%:30%). After establishing a baseline intake for 1 wk, mice were divided into two groups that were well matched for (A) caloric and (C) macronutrient intake. Next, we delivered FGF21 (0.2 mg/kg/d, IP) or saline for 7 d. (D) There was no effect of FGF21 on macronutrient selection. In agreement with its established role to increase energy expenditure, FGF21 (E) induced weight loss, (B) despite a tendency to increase caloric intake. Data are shown as mean ± SEM; n = 12 mice per group. All comparisons were made by a t test: **P < 0.01. CHO, carbohydrate.

Comparing the outcomes from this series of two-choice experiments identifies protein as the primary regulated variable in our three-choice study. The results from the iso-FAT and iso-CHO experiments support that FGF21 increases protein intake at the expense of either carbohydrate or fat. The results of the iso-PRO experiment support that FGF21 does not change macronutrient preference when protein (and sucrose) content is held constant. Therefore, we conclude that, with regard to dietary macronutrient preference, FGF21 specifically acts to increase the relative intake of dietary protein.

Macronutrient intake in neuronal Klb-null mice

FGF21 preferentially signals to tissues using a heteromeric cell-surface receptor comprised of the FGF receptor-1 (Fgfr1) in complex with its obligate co-receptor β-klotho (Klb) (36, 37) to signal via RAS/MAPK, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT, and protein kinase C (6). Whereas Fgfr1 is broadly distributed, Klb is discretely localized and provides tissue and cell-type specificity for FGF21 action (38). In the brain, Klb is highly expressed in the suprachiasmatic nucleus of the hypothalamus, in the nucleus of the solitary tract, and in the area postrema (39). It is also modestly expressed in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus, where it directs feeding responses to sweet taste (26). To determine the contribution of neuronal β-klotho to mediate increased protein intake after peripheral FGF21 administration, we performed a two-diet choice experiment using the iso-FAT diets described above. First, we maintained neuron-specific β-klotho-null mice (KlbΔSynCre) and littermate controls (Klbflox/flox/Cre−) on diets that were matched at 22% fat, together with 18% protein and 60% carbohydrates or 4% protein and 74% carbohydrates to establish a baseline, as above (D11051801 and D11092301 as in Fig. 3; see Table 2). Next, within each genotype, mice were divided into two treatment groups matched for baseline caloric (Fig. 6A) and macronutrient intake (Fig. 6C). Lastly, we delivered FGF21 (0.1 mg/kg, twice daily, IP) and measured intake of the two diets for 7 days. FGF21 increased total caloric intake [Fig. 6B, two-way ANOVA, P (drug) < 0.05] and there was no interaction with genotype. As expected, however, the effect of FGF21 treatment on macronutrient intake depended on genotype [Fig. 6D, two-way ANOVA, P (treatment × genotype) < 0.05]. Put another way, only the Klbflox/flox/Cre− mice significantly altered diet selection relative to baseline by increasing protein intake in response to FGF21 (Wilcoxon signed-rank test, P < 0.05). There was no significant effect of FGF21 on body weight in this experiment (Fig. 6E), likely because of the smaller group size and the small effect size among mice consuming low-fat diets (34). Lastly, we confirmed the efficacy of our cre-lox recombination by measuring Klb mRNA expression from the mice involved in this experiment. We observed a 59% decrease in Klb expression from whole brain of KlbΔSynCre mice compared with the Klbflox/flox/Cre− littermate controls, whereas there was no difference in Klb expression in intrascapular brown adipose or inguinal white adipose tissue (Fig. 6F, t test, P < 0.001). We conclude that FGF21 acts via its receptors in neurons to elicit changes in dietary protein intake. Further studies are needed to identify the critical neuronal populations.

Discussion

In this study, we identify a novel role for the polypeptide hormone FGF21 in the neuroendocrine control of dietary protein intake. First, we find that the previously reported effect of FGF21 to reduce simple sugar intake (20, 21) involves caloric tradeoffs with other available dietary options (Fig. 1). To more clearly define the nature of these tradeoffs, we used a standard three-choice pure macronutrient diet paradigm. In response to FGF21, mice increased consumption of protein while reducing consumption of carbohydrate. There was no effect on fat intake (Fig. 2). Next, to determine whether protein or carbohydrate was the primary regulated nutrient, we employed a series of two-choice experiments to isolate the effect of FGF21 on preference for each of the three macronutrients. Sweetness was well controlled by holding sucrose constant across all of the diets. Under these conditions, we found that FGF21 increased consumption of dietary protein while decreasing the consumption of either carbohydrate or fat (Figs. 3 and 4). However, when protein was held constant between the two-diet options, there was no effect of FGF21 on the relative consumption of carbohydrate vs fat (Fig. 5). Finally, we report that the effect of FGF21 to alter dietary protein intake was dependent on the presence of its co-receptor, β-klotho, in neurons (Fig. 6). Thus, FGF21 is a hepatokine that is secreted into circulation during dietary protein or amino acid restriction, in both rodents and humans (2, 12–15, 17, 23), and it feeds back via the nervous system to increase the relative intake of dietary protein.

The homeostatic regulation of energy balance is essential to survival. Consequently, well-described and robust neuroendocrine pathways control caloric intake to facilitate the defense of total energy stores (40–43). However, food intake is critical not only to supply energy substrates, but also to provide organic building blocks supporting growth (e.g., during development) and/or for dynamic use, maintenance, and repair (e.g., in adulthood). Moreover, although carbohydrates and lipids can be stored as glycogen and fat, there is no easily accessible, inert storage form of protein. Continuous adjustments in feeding behavior are therefore needed to ensure an adequate supply of amino acids for ongoing needs.

Perhaps the strongest evidence for a behavioral control of dietary protein and amino acid homeostasis comes from the multidimensional geometric framework model, which provides a quantitative assessment of macronutrient intake in a free-feeding situation (3, 44–48). The model has been applied across diverse species, including rodents (3) and humans (49), and consistently finds a strong behavioral regulation of dietary protein intake. Moreover, the data support that when the ratio of dietary protein/total energy is low, a drive to consume sufficient protein supersedes the homeostatic control of energy balance. It has been suggested, therefore, that this “protein leverage” may be a driving force contributing to the global rise in obesity [(50, 51), but see Simpson et al. (49)]. If so, defining the underlying mechanisms may provide new opportunities for manipulating food intake to improve metabolic health. Yet there has been little progress defining critical neuroendocrine mediators (1–3, 44, 52).

Amino acids can be directly sensed by neurons that control feeding behavior. For example, diets devoid of one or more essential amino acids are aversive and are rejected by both rodents and humans (53–55). This learned taste aversion, and subsequent hypophagia, is thought to rely on direct neuronal sensing of amino acid depletion or imbalance by the GCN2 kinase in neurons of the anterior piriform cortex (APC) (52), because it is prevented in GCN2-null mice [but see Leib and Knight (48)] by lesioning the APC, or by directly injecting the missing dietary amino acid locally within the APC (56–60). Careful recent studies by Leib and Knight (48) indicate the rapid aversive response to amino acid–depleted diets requires a prior physiologic need; that is, the mice must be previously deprived of one or more individual amino acids, or of total dietary protein, for 2 days prior to behavioral testing. They concluded that this “need-based mechanism” is the primary innate mechanism animals possess to select among diets based on their amino acid and/or protein content. The present data position FGF21 as a likely neuroendocrine signal of this “prior physiologic need” and suggest future research to determine how/whether the FGF21 signal interacts with direct amino acid sensing in the APC.

Local excess of certain amino acids can also be sensed by neurons to alter feeding behavior. Rodents maintained on high-protein diets are hypophagic, and this is recapitulated by dietary supplementation with l-leucine (3, 52, 61). Moreover, injecting a leucine-containing mixture of amino acids, or l-leucine alone, into the brain of fasted rodents reduces total energy intake during the subsequent refeeding period (62–66). The leucine-induced hypophagia is thought to depend in part on direct activation of mTORC1 and AMP-activated protein kinase (62, 64, 66, 67) and in part on local branched chain amino acid catabolism (67) in key neuronal populations of the medial basal hypothalamus and brainstem. The relevance of brain leucine signaling to a specific regulation of dietary protein intake vs calories per se, however, is unknown. Notably, brain leucine sensing is most effective to reduce total caloric intake in fasted rodents [reviewed in Heeley and Blouet (52)] or in rodents fed ad libitum low-protein diet (68). Thus, any potential effect of hypothalamic or brainstem leucine-sensing on macronutrient selection may also require a signal of “physiologic need” to shift diet preferences. Future studies will investigate whether direct central nervous system infusion of amino acids and/or l-leucine is sufficient to blunt the FGF21-induced increase of dietary protein intake.

The current study has several limitations. First, we used casein as the sole source of dietary protein in all of the experiments. This logistical decision allows for continuity with the original literature describing FGF21 as a signal of dietary protein restriction (15–17), and it maintains internal consistency to facilitate comparisons across all of the choice paradigms. Because deficits in a number of essential (13, 14) and nonessential (12, 15) amino acids are known to increase FGF21 secretion, we expect that this neuroendocrine system is responding to “dietary protein” in the generic sense. Thus, we anticipate that the homeostatic model supported by the current studies will generalize to other protein sources—but certainly this is an important empirical question that will be addressed in future work. Likewise, it remains uncertain to what extent FGF21 contributes to dietary preferences for specific amino acids, but we hypothesize that it acts as a “signal of physiologic need” to modulate the behavioral response to direct individual amino acid sensing, as discussed above. Second, the experiment with neuron-specific knockout mice did not include KlbCre+/flox− controls. Although we consider it unlikely, it is possible the expression of Cre recombinase alone interferes with FGF21 action, independent of β-klotho. This potential confound will likely be resolved by future use of nucleus-specific viral approaches to delineate the intracellular signaling mechanisms and specific neuroanatomic circuits mediating the observed behaviors. Third, the current experiments all involved exogenous administration of recombinant FGF21. Further research using FGF21-null mice will be necessary to clarify the physiological relevance of these findings. Lastly, the current findings include only male mice. In light of the divergent energetic and nutritional costs of reproduction in male and female mammals, it will be especially important to compare the role of FGF21 to control dietary protein intake in females and males.

Conclusions

Because it is the primary anatomical site of amino acid catabolism and biosynthesis, the liver is well situated to function as a “canary in the coal mine,” signaling physiologic need to the brain during times of protein deficit, and eliciting behaviors that replenish an adequate supply for cells throughout the body. Together with previous reports that define FGF21 as an endocrine signal of dietary amino acid and/or protein restriction (2, 12–15, 17, 23), the present findings support a critical liver → nervous system mechanism facilitating the control of dietary protein intake via FGF21. Amino acids are one of the main building blocks of life and are used not only as fuels, but as precursors for hormones, neurotransmitters, enzymes, and structural proteins throughout the body (69). Therefore the quantity and quality of dietary protein intake has a critical influence on diverse aspects of organismal health (70), including development (71, 72), growth (73), metabolism (1), performance (71, 72), immune function (74, 75), cognition (71, 72), and aging (76). Identifying the critical role of FGF21 signaling in the nervous system to control dietary protein intake represents a first step toward new opportunities for manipulating macronutrient intake to benefit various aspects of health and longevity.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R56 DK117412 (to K.K.R.) and by startup funds from the University of California, Davis, College of Biological Sciences (to K.K.R.) The funding sources had no role in study design, nor in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- APC

anterior piriform cortex

- bw

body weight

- FGF21

fibroblast growth factor-21

- Fgfr1

fibroblast growth factor receptor-1

- hFGF21

human fibroblast growth factor-21

- P/C

protein/carbohydrate

References

- 1. Morrison CD, Laeger T. Protein-dependent regulation of feeding and metabolism. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2015;26(5):256–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Solon-Biet SM, Cogger VC, Pulpitel T, Heblinski M, Wahl D, McMahon AC, Warren A, Durrant-Whyte J, Walters KA, Krycer JR, Ponton F, Gokarn R, Wali JA, Ruohonen K, Conigrave AD, James DE, Raubenheimer D, Morrison CD, Le Couteur DG, Simpson SJ. Defining the nutritional and metabolic context of FGF21 using the geometric framework. Cell Metab. 2016;24(4):555–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Solon-Biet SM, McMahon AC, Ballard JW, Ruohonen K, Wu LE, Cogger VC, Warren A, Huang X, Pichaud N, Melvin RG, Gokarn R, Khalil M, Turner N, Cooney GJ, Sinclair DA, Raubenheimer D, Le Couteur DG, Simpson SJ. The ratio of macronutrients, not caloric intake, dictates cardiometabolic health, aging, and longevity in ad libitum-fed mice. Cell Metab. 2014;19(3):418–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nishimura T, Nakatake Y, Konishi M, Itoh N. Identification of a novel FGF, FGF-21, preferentially expressed in the liver. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1492(1):203–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kharitonenkov A, Shiyanova TL, Koester A, Ford AM, Micanovic R, Galbreath EJ, Sandusky GE, Hammond LJ, Moyers JS, Owens RA, Gromada J, Brozinick JT, Hawkins ED, Wroblewski VJ, Li DS, Mehrbod F, Jaskunas SR, Shanafelt AB. FGF-21 as a novel metabolic regulator. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(6):1627–1635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fisher FM, Maratos-Flier E. Understanding the physiology of FGF21. Annu Rev Physiol. 2016;78(1):223–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. BonDurant LD, Potthoff MJ. Fibroblast growth factor 21: a versatile regulator of metabolic homeostasis. Annu Rev Nutr. 2018;38(1):173–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Inagaki T, Dutchak P, Zhao G, Ding X, Gautron L, Parameswara V, Li Y, Goetz R, Mohammadi M, Esser V, Elmquist JK, Gerard RD, Burgess SC, Hammer RE, Mangelsdorf DJ, Kliewer SA. Endocrine regulation of the fasting response by PPARα-mediated induction of fibroblast growth factor 21. Cell Metab. 2007;5(6):415–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Badman MK, Pissios P, Kennedy AR, Koukos G, Flier JS, Maratos-Flier E. Hepatic fibroblast growth factor 21 is regulated by PPARα and is a key mediator of hepatic lipid metabolism in ketotic states. Cell Metab. 2007;5(6):426–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ryan KK, Packard AEB, Larson KR, Stout J, Fourman SM, Thompson AMK, Ludwick K, Habegger KM, Stemmer K, Itoh N, Perez-Tilve D, Tschöp MH, Seeley RJ, Ulrich-Lai YM. Dietary manipulations that induce ketosis activate the HPA axis in male rats and mice: a potential role for fibroblast growth factor-21. Endocrinology. 2018;159(1):400–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stemmer K, Zani F, Habegger KM, Neff C, Kotzbeck P, Bauer M, Yalamanchilli S, Azad A, Lehti M, Martins PJF, Müller TD, Pfluger PT, Seeley RJ. FGF21 is not required for glucose homeostasis, ketosis or tumour suppression associated with ketogenic diets in mice. Diabetologia. 2015;58(10):2414–2423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shimizu N, Maruyama T, Yoshikawa N, Matsumiya R, Ma Y, Ito N, Tasaka Y, Kuribara-Souta A, Miyata K, Oike Y, Berger S, Schütz G, Takeda S, Tanaka H. A muscle-liver-fat signalling axis is essential for central control of adaptive adipose remodelling. Nat Commun. 2015;6(1):6693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. De Sousa-Coelho AL, Relat J, Hondares E, Pérez-Martí A, Ribas F, Villarroya F, Marrero PF, Haro D. FGF21 mediates the lipid metabolism response to amino acid starvation. J Lipid Res. 2013;54(7):1786–1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wanders D, Forney LA, Stone KP, Burk DH, Pierse A, Gettys TW. FGF21 mediates the thermogenic and insulin-sensitizing effects of dietary methionine restriction but not its effects on hepatic lipid metabolism. Diabetes. 2017;66(4):858–867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Maida A, Zota A, Sjøberg KA, Schumacher J, Sijmonsma TP, Pfenninger A, Christensen MM, Gantert T, Fuhrmeister J, Rothermel U, Schmoll D, Heikenwälder M, Iovanna JL, Stemmer K, Kiens B, Herzig S, Rose AJ. A liver stress-endocrine nexus promotes metabolic integrity during dietary protein dilution. J Clin Invest. 2016;126(9):3263–3278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Laeger T, Albarado DC, Burke SJ, Trosclair L, Hedgepeth JW, Berthoud HR, Gettys TW, Collier JJ, Münzberg H, Morrison CD. Metabolic responses to dietary protein restriction require an increase in FGF21 that is delayed by the absence of GCN2. Cell Reports. 2016;16(3):707–716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Laeger T, Henagan TM, Albarado DC, Redman LM, Bray GA, Noland RC, Münzberg H, Hutson SM, Gettys TW, Schwartz MW, Morrison CD. FGF21 is an endocrine signal of protein restriction. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(9):3913–3922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sánchez J, Palou A, Picó C. Response to carbohydrate and fat refeeding in the expression of genes involved in nutrient partitioning and metabolism: striking effects on fibroblast growth factor-21 induction. Endocrinology. 2009;150(12):5341–5350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Søberg S, Sandholt CH, Jespersen NZ, Toft U, Madsen AL, von Holstein-Rathlou S, Grevengoed TJ, Christensen KB, Bredie WL, Potthoff MJ, Solomon TP, Scheele C, Linneberg A, Jørgensen T, Pedersen O, Hansen T, Gillum MP, Grarup N. FGF21 is a sugar-induced hormone associated with sweet intake and preference in humans. Cell Metab. 2017;25(5):1045–1053.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Talukdar S, Owen BM, Song P, Hernandez G, Zhang Y, Zhou Y, Scott WT, Paratala B, Turner T, Smith A, Bernardo B, Müller CP, Tang H, Mangelsdorf DJ, Goodwin B, Kliewer SA. FGF21 regulates sweet and alcohol preference. Cell Metab. 2016;23(2):344–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. von Holstein-Rathlou S, BonDurant LD, Peltekian L, Naber MC, Yin TC, Claflin KE, Urizar AI, Madsen AN, Ratner C, Holst B, Karstoft K, Vandenbeuch A, Anderson CB, Cassell MD, Thompson AP, Solomon TP, Rahmouni K, Kinnamon SC, Pieper AA, Gillum MP, Potthoff MJ. FGF21 mediates endocrine control of simple sugar intake and sweet taste preference by the liver. Cell Metab. 2016;23(2):335–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dushay JR, Toschi E, Mitten EK, Fisher FM, Herman MA, Maratos-Flier E. Fructose ingestion acutely stimulates circulating FGF21 levels in humans. Mol Metab. 2014;4(1):51–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Larson KR, Russo KA, Fang Y, Mohajerani N, Goodson ML, Ryan KK. Sex differences in the hormonal and metabolic response to dietary protein dilution. Endocrinology. 2017;158(10):3477–3487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hsuchou H, Pan W, Kastin AJ. The fasting polypeptide FGF21 can enter brain from blood. Peptides. 2007;28(12):2382–2386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Owen BM, Ding X, Morgan DA, Coate KC, Bookout AL, Rahmouni K, Kliewer SA, Mangelsdorf DJ. FGF21 acts centrally to induce sympathetic nerve activity, energy expenditure, and weight loss. Cell Metab. 2014;20(4):670–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Douris N, Stevanovic DM, Fisher FM, Cisu TI, Chee MJ, Nguyen NL, Zarebidaki E, Adams AC, Kharitonenkov A, Flier JS, Bartness TJ, Maratos-Flier E. Central fibroblast growth factor 21 browns white fat via sympathetic action in male mice. Endocrinology. 2015;156(7):2470–2481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chu AY, Workalemahu T, Paynter NP, Rose LM, Giulianini F, Tanaka T, Ngwa JS, Qi Q, Curhan GC, Rimm EB, Hunter DJ, Pasquale LR, Ridker PM, Hu FB, Chasman DI, Qi L; CHARGE Nutrition Working Group; DietGen Consortium. Novel locus including FGF21 is associated with dietary macronutrient intake. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22(9):1895–1902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Harno E, Cottrell EC, White A. Metabolic pitfalls of CNS Cre-based technology. Cell Metab. 2013;18(1):21–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ryan KK, Tremaroli V, Clemmensen C, Kovatcheva-Datchary P, Myronovych A, Karns R, Wilson-Pérez HE, Sandoval DA, Kohli R, Bäckhed F, Seeley RJ. FXR is a molecular target for the effects of vertical sleeve gastrectomy. Nature. 2014;509(7499):183–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chambers AP, Wilson-Perez HE, McGrath S, Grayson BE, Ryan KK, D’Alessio DA, Woods SC, Sandoval DA, Seeley RJ. Effect of vertical sleeve gastrectomy on food selection and satiation in rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2012;303(8):E1076–E1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Reeves PG, Nielsen FH, Fahey GC Jr. AIN-93 purified diets for laboratory rodents: final report of the American Institute of Nutrition ad hoc writing committee on the reformulation of the AIN-76A rodent diet. J Nutr. 1993;123(11):1939–1951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nguyen AN, Song JA, Nguyen MT, Do BH, Kwon GG, Park SS, Yoo J, Jang J, Jin J, Osborn MJ, Jang YJ, Thi Vu TT, Oh HB, Choe H. Prokaryotic soluble expression and purification of bioactive human fibroblast growth factor 21 using maltose-binding protein. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):16139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.RRID:AB_2783729, https://scicrunch.org/resolver/AB_2783729.

- 34. Hale C, Chen MM, Stanislaus S, Chinookoswong N, Hager T, Wang M, Véniant MM, Xu J. Lack of overt FGF21 resistance in two mouse models of obesity and insulin resistance. Endocrinology. 2012;153(1):69–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sarruf DA, Thaler JP, Morton GJ, German J, Fischer JD, Ogimoto K, Schwartz MW. Fibroblast growth factor 21 action in the brain increases energy expenditure and insulin sensitivity in obese rats. Diabetes. 2010;59(7):1817–1824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ogawa Y, Kurosu H, Yamamoto M, Nandi A, Rosenblatt KP, Goetz R, Eliseenkova AV, Mohammadi M, Kuro-o M. βKlotho is required for metabolic activity of fibroblast growth factor 21. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(18):7432–7437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kurosu H, Choi M, Ogawa Y, Dickson AS, Goetz R, Eliseenkova AV, Mohammadi M, Rosenblatt KP, Kliewer SA, Kuro-o M. Tissue-specific expression of βKlotho and fibroblast growth factor (FGF) receptor isoforms determines metabolic activity of FGF19 and FGF21. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(37):26687–26695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fon Tacer K, Bookout AL, Ding X, Kurosu H, John GB, Wang L, Goetz R, Mohammadi M, Kuro-o M, Mangelsdorf DJ, Kliewer SA. Research resource: comprehensive expression atlas of the fibroblast growth factor system in adult mouse. Mol Endocrinol. 2010;24(10):2050–2064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bookout AL, de Groot MH, Owen BM, Lee S, Gautron L, Lawrence HL, Ding X, Elmquist JK, Takahashi JS, Mangelsdorf DJ, Kliewer SA. FGF21 regulates metabolism and circadian behavior by acting on the nervous system. Nat Med. 2013;19(9):1147–1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Woods SC, Seeley RJ, Porte D Jr, Schwartz MW. Signals that regulate food intake and energy homeostasis. Science. 1998;280(5368):1378–1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ryan KK, Woods SC, Seeley RJ. Central nervous system mechanisms linking the consumption of palatable high-fat diets to the defense of greater adiposity. Cell Metab. 2012;15(2):137–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Dryden S, Frankish H, Wang Q, Williams G. Neuropeptide Y and energy balance: one way ahead for the treatment of obesity? Eur J Clin Invest. 1994;24(5):293–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gautron L, Elmquist JK, Williams KW. Neural control of energy balance: translating circuits to therapies. Cell. 2015;161(1):133–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Morrison CD, Reed SD, Henagan TM. Homeostatic regulation of protein intake: in search of a mechanism. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2012;302(8):R917–R928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Le Couteur DG, Solon-Biet S, Cogger VC, Mitchell SJ, Senior A, de Cabo R, Raubenheimer D, Simpson SJ. The impact of low-protein high-carbohydrate diets on aging and lifespan. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2016;73(6):1237–1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Simpson SJ, Raubenheimer D. Macronutrient balance and lifespan. Aging (Albany NY). 2009;1(10):875–880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Simpson SJ, Raubenheimer D. Geometric analysis of macronutrient selection in the rat. Appetite. 1997;28(3):201–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Leib DE, Knight ZA. Rapid sensing of dietary amino acid deficiency does not require GCN2. Cell Reports. 2016;16(8):2051–2052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Simpson SJ, Batley R, Raubenheimer D. Geometric analysis of macronutrient intake in humans: the power of protein? Appetite. 2003;41(2):123–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Raubenheimer D, Machovsky-Capuska GE, Gosby AK, Simpson S. Nutritional ecology of obesity: from humans to companion animals. Br J Nutr. 2015;113(Suppl):S26–S39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Simpson SJ, Raubenheimer D. Obesity: the protein leverage hypothesis. Obes Rev. 2005;6(2):133–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Heeley N, Blouet C. Central amino acid sensing in the control of feeding behavior. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2016;7:148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Rose WC, Johnson JE, Haines WJ. The amino acid requirements of man I. The role of valine and methionine. J Biol Chem. 1950;182:541–556. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Rose WC. Feeding experiments with mixtures of highly purified amino acids. I. The inadequacy of diets containing nineteen amino acids. J Biol Chem. 1931;94:155–165. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Leung PM, Rogers QR, Harper AE. Effect of amino acid imbalance in rats fed ad libitum, interval-fed or force-fed. J Nutr. 1968;95(3):474–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Leung PM, Rogers QR. Importance of prepyriform cortex in food-intake response of rats to amino acids. Am J Physiol. 1971;221(3):929–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Beverly JL, Gietzen DW, Rogers QR. Effect of dietary limiting amino acid in prepyriform cortex on food intake. Am J Physiol. 1990;259(4 Pt 2):R709–R715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Rudell JB, Rechs AJ, Kelman TJ, Ross-Inta CM, Hao S, Gietzen DW. The anterior piriform cortex is sufficient for detecting depletion of an indispensable amino acid, showing independent cortical sensory function. J Neurosci. 2011;31(5):1583–1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Russell MC, Koehnle TJ, Barrett JA, Blevins JE, Gietzen DW. The rapid anorectic response to a threonine imbalanced diet is decreased by injection of threonine into the anterior piriform cortex of rats. Nutr Neurosci. 2003;6(4):247–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Berthoud HR, Münzberg H, Richards BK, Morrison CD. Neural and metabolic regulation of macronutrient intake and selection. Proc Nutr Soc. 2012;71(3):390–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Simpson SJ, Le Couteur DG, Raubenheimer D. Putting the balance back in diet. Cell. 2015;161(1):18–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Cota D, Proulx K, Smith KA, Kozma SC, Thomas G, Woods SC, Seeley RJ. Hypothalamic mTOR signaling regulates food intake. Science. 2006;312(5775):927–930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Morrison X, Morrison CD, Xi X, White CL, Ye J, Martin RJ. Amino acids inhibit Agrp gene expression via an mTOR-dependent mechanism. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;293(1):E165–E171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Journel M, Chaumontet C, Darcel N, Fromentin G, Tomé D. Brain responses to high-protein diets. Adv Nutrition. 2012;3(3):322–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Blouet C, Ono H, Schwartz GJ. Mediobasal hypothalamic p70 S6 kinase 1 modulates the control of energy homeostasis. Cell Metab. 2008;8(6):459–467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Blouet C, Schwartz GJ. Brainstem nutrient sensing in the nucleus of the solitary tract inhibits feeding. Cell Metab. 2012;16(5):579–587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Blouet C, Jo Y-H, Li X, Schwartz GJ. Mediobasal hypothalamic leucine sensing regulates food intake through activation of a hypothalamus-brainstem circuit. J Neurosci. 2009;29(26):8302–8311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Laeger T, Reed SD, Henagan TM, Fernandez DH, Taghavi M, Addington A, Münzberg H, Martin RJ, Hutson SM, Morrison CD. Leucine acts in the brain to suppress food intake but does not function as a physiological signal of low dietary protein. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2014;307(3):R310–R320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Bröer S, Bröer A. Amino acid homeostasis and signalling in mammalian cells and organisms. Biochem J. 2017;474(12):1935–1963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Millward DJ, Layman DK, Tomé D, Schaafsma G. Protein quality assessment: impact of expanding understanding of protein and amino acid needs for optimal health. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87(5):1576S–1581S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Langley SC, Jackson AA. Increased systolic blood pressure in adult rats induced by fetal exposure to maternal low protein diets. Clin Sci (Lond). 1994;86(2):217–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Zeman FJ, Stanbrough EC. Effect of maternal protein deficiency on cellular development in the fetal rat. J Nutr. 1969;99(3):274–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Ketelslegers JM, Maiter D, Maes M, Underwood LE, Thissen JP. Nutritional regulation of insulin-like growth factor-I. Metabolism. 1995;44(10Suppl 4):50–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Law DK, Dudrick SJ, Abdou NI. Immunocompetence of patients with protein-calorie malnutrition. The effects of nutritional repletion. Ann Intern Med. 1973;79(4):545–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Iyer SS, Chatraw JH, Tan WG, Wherry EJ, Becker TC, Ahmed R, Kapasi ZF. Protein energy malnutrition impairs homeostatic proliferation of memory CD8 T cells. J Immunol. 2012;188(1):77–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Solon-Biet SM, Walters KA, Simanainen UK, McMahon AC, Ruohonen K, Ballard JW, Raubenheimer D, Handelsman DJ, Le Couteur DG, Simpson SJ. Macronutrient balance, reproductive function, and lifespan in aging mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112(11):3481–3486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]