Abstract

Background:

Chronic use of μ-opioid receptor agonists paradoxically causes both hyperalgesia and the loss of analgesic efficacy. Opioid treatment increases presynaptic N-Methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) activity to potentiate nociceptive input to spinal dorsal horn neurons. However, the mechanism responsible for this opioid-induced activation of presynaptic NMDARs remains unclear. α2δ-1, formerly known as a calcium channel subunit, interacts with NMDARs and is primarily expressed at presynaptic terminals. In this study, we tested the hypothesis that α2δ-1–bound NMDARs contribute to presynaptic NMDAR hyperactivity associated with opioid-induced hyperalgesia and analgesic tolerance.

Methods:

Rats (5 mg/kg) and wild-type and α2δ-1–knockout mice (10 mg/kg) were treated intraperitoneally with morphine twice/day for 8 consecutive days, and nociceptive thresholds were examined. Presynaptic NMDAR activity was recorded in spinal cord slices. Coimmunoprecipitation was performed to examine protein-protein interactions.

Results:

Chronic morphine treatment in rats increased α2δ-1 protein amounts in the dorsal root ganglion and spinal cord. Chronic morphine exposure also increased the physical interaction between α2δ-1 and NMDARs by 1.5 ± 0.3 fold (mean ± SD, p = 0.009, n = 6) and the prevalence of α2δ-1–bound NMDARs at spinal cord synapses. Inhibiting α2δ-1 with gabapentin or genetic knockout of α2δ-1 abolished the increase in presynaptic NMDAR activity in the spinal dorsal horn induced by morphine treatment. Furthermore, uncoupling the α2δ-1–NMDAR interaction with an α2δ-1 C-terminus–interfering peptide fully reversed morphine-induced tonic activation of NMDARs at the central terminal of primary afferents. Finally, intraperitoneal injection of gabapentin or intrathecal injection of an α2δ-1 C-terminus–interfering peptide or α2δ-1 genetic knockout abolished the mechanical and thermal hyperalgesia induced by chronic morphine exposure and largely preserved morphine’s analgesic effect during 8 days of morphine treatment.

Conclusions:

α2δ-1–bound NMDARs contribute to opioid-induced hyperalgesia and tolerance by augmenting presynaptic NMDAR expression and activity at the spinal cord level.

Summary Statement:

Chronic morphine treatment increases the α2δ-1 association with NMDA receptors at spinal cord synapses. Interrupting the α2δ-1–NMDA receptor interaction diminishes presynaptic NMDA receptor hyperactivity, hyperalgesia, and analgesic tolerance caused by morphine treatment.

Introduction

The μ-opioid receptor agonists remain the gold standard for the treatment of cancer pain and severe pain caused by tissue and nerve injury. However, over time, opioid use can paradoxically cause hyperalgesia and the loss of analgesic efficacy leading to rapid opioid dose escalation, a significant clinical problem in the treatment of pain with opioids. The cellular and molecular mechanisms responsible for opioid-induced hyperalgesia and analgesic tolerance are not well understood. Although it has been shown that morphine-induced hyperalgesia, but not tolerance, requires μ-opioid receptor-dependent expression of P2X4 receptors in microglia in the spinal cord1, there is a strong link between opioid-induced hyperalgesia and analgesic tolerance. For example, both the analgesic effect of opioids and opioid-induced hyperalgesia and analgesic tolerance are predominantly mediated by μ-opioid receptors in the dorsal root ganglion (DRG) and the spinal dorsal horn2–6. Morphine-induced hyperalgesia and tolerance largely results from stimulation of μ-opioid receptors expressed on TRPV1-expressing DRG neurons5,7. Additionally, the glutamate N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDARs) at the spinal cord level are critically involved in opioid-induced hyperalgesia and analgesic tolerance4,8–11. Conventional NMDARs are located postsynaptically, but both acute and chronic opioid treatments predominantly affect presynaptic NMDARs in the spinal cord4,12,13. Chronic morphine administration diminishes postsynaptic NMDAR activity in the spinal dorsal horn4. NMDARs are expressed at the central terminals of primary sensory neurons in the spinal dorsal horn14, although they are not functionally active under physiological conditions4,13,15. Chronic opioid treatment induces tonic activation of NMDARs at primary afferent terminals, which augments nociceptive input to spinal dorsal horn neurons4,12. Blocking NMDARs with ketamine can potentiate the opioid analgesic effect or reduce opioid consumption in patients with opioid tolerance16,17. Nevertheless, it remains unclear how opioids lead to increased presynaptic NMDAR activity at the spinal cord level. Understanding the molecular and signaling mechanism involved could lead to improved opioid analgesic efficacy.

α2δ-1 (encoded by Cacna2d1) is generally known to be a subunit of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (VGCCs) and is expressed in the dorsal root ganglion (DRG) and spinal superficial dorsal horn18–20. However, quantitative proteomic analysis has revealed that α2δ-1 only weakly interacts with VGCCs in brain tissues21. Moreover, VGCC currents in brain neurons are similar in wild-type (WT) and Cacna2d1 knockout (KO) mice22. Our recent findings indicate that α2δ-1, through its C-terminal domain, forms a heteromeric complex with NMDARs to promote their synaptic/surface trafficking23. Although α2δ-1–bound NMDARs are primarily involved in NMDAR hyperactivity in pathological conditions, such as neuropathic pain and hypertension23,24, there is no evidence that they play a role in tonic activation of presynaptic NMDARs associated with opioid-induced tolerance and hyperalgesia.

In this study, we determined the role of α2δ-1–bound NMDARs in tonic activation of presynaptic NMDARs associated with opioid-induced hyperalgesia and tolerance. In this study, we provide substantial new evidence showing that α2δ-1 contributes critically to the increase in presynaptic NMDAR activity in the spinal cord induced by opioids. This new information extends our understanding of the role of α2δ-1–bound NMDARs at the spinal cord level in opioid-induced analgesic tolerance and hyperalgesia.

Materials and Methods

Animal models and intrathecal catheterization

All experimental procedures and protocols were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (Houston, TX) and were performed in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health. Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (9–11 weeks of age; Harlan, Indianapolis, IN) were used in most of the experiments.

Repeated intrathecal injections in rats were performed via the intrathecal catheter. Single intrathecal injection in rats was performed using a lumbar puncture technique as previously described25. For intrathecal catheter insertion, rats were placed under isoflurane-induced anesthesia and positioned prone on a stereotaxic frame. A small puncture was made in the atlanto-occipital membrane of the cisterna magna. A catheter (PE-10 tubing) was then inserted such that the caudal tip reached the lumbar enlargement of the spinal cord3,7. We then exteriorized the rostral end of the catheter and closed the wound with sutures. The animals were allowed to recover for at least 5 days before intrathecal injections. In 20 rats with intrathecal catheters, 2 rats displayed neurological deficits (e.g., paralysis) or poor grooming and were promptly killed with CO2 inhalation.

The generation of conventional Cacna2d1 KO mice (C57BL/6 genetic background) was described previously26. Two breeding pairs of Cacna2d1+/− mice were purchased from Medical Research Council (Harwell Didcot, Oxfordshire, UK). Cacna2d1−/− (KO) mice and Cacna2d1+/+ (WT) littermates were obtained by breeding the Cacna2d1+/− heterozygous mice. Animals were ear-marked at the time of weaning (3 weeks after birth), and tail biopsies were used for genotyping. Both male and female adult mice (8–10 weeks of age) were used for final electrophysiological and behavioral studies. All experiments were conducted between 9 am and 6 pm.

Morphine treatment and drug delivery

To induce opioid analgesic tolerance, morphine sulfate (West Ward Pharmaceuticals, Eatontown, NJ) was injected intraperitoneally at a dose of 5 mg/kg (in rats) or 10 mg/kg (in mice) twice a day for 8 consecutive days4,7. The α2δ-1Tat peptide and scrambled control peptide were synthesized by Bio Basic Inc. (Marham, Ontario, Canada) and validated by using liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry. The α2δ-1Tat peptide and Tat-fused scrambled control peptide were dissolved in saline and injected intrathecally, followed by a 10 μl saline flush 20 min before morphine administration on each testing day. Gabapentin (Tocris Bioscience, Ellisville, MO) was dissolved in saline and injected intraperitoneally before morphine administration on each testing day.

Western immunoblotting

Western blotting was used to quantify the α2δ-1 protein level in the dorsal spinal cord and DRG. Spinal cord and DRG tissues at the L5–L6 levels were collected and homogenized in 300 μl radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM NaF, 1% Nonidet P-40, and 0.25% sodium-deoxycholate) with a protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). The samples were homogenized with lysis buffer on ice for 30 min, and centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was carefully collected, and its protein concentration was measured. The protein samples extracted from spinal cord and DRG tissues were subjected to 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. The blots were probed with a rabbit anti-α2δ-1 antibody (1:500; #ACC-015, Alomone Labs, Jerusalem, Israel) or rabbit anti-GAPDH antibody (1:5000; #14C10, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA). The protein bands were detected with an ECL kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), and protein band intensity was visualized and quantified using an Odyssey Fc Imager (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE).

Coimmunoprecipitation using spinal cord membrane extracts

Spinal cord tissues at the L5 and L6 levels were collected and homogenized in ice-cold hypotonic buffer (20 mM Tris [pH 7.4], 1 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM CaCl2) containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich) for extracting membrane proteins. The unbroken cells and nuclei were removed by centrifugation at 300 × g for 5 min, and the supernatant was centrifuged for 20 min at 21,000 × g. The pellets were re-suspended and solubilized in immunoprecipitation buffer (50 mM Tris [pH7.4], 250 mM NaCl, 1 mM Na3VO4, 10 mM N-ethylmaleimide, 20 mM NaF, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 2 mM benzamide, 10% glycerol, and 0.5% NP-40) containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich), and the soluble fraction was incubated at 4 °C overnight with protein A/G beads (#16–266, Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany) prebound to mouse anti-GluN1 antibodies (1:1,000; #75–272, NeuroMab, Davis, CA). Protein A/G beads prebound to mouse IgG were used as a control. All samples were washed 3 times with immunoprecipitation buffer and then immunoblotted. The following antibodies and concentrations were used for immunoblotting: rabbit anti-α2δ-1 (1:1,000; #C5105, Sigma-Aldrich; #ACC-015, Alomone Labs, Jerusalem, Israel) and rabbit anti-GluN1 (1:1,000; #G8913, Sigma-Aldrich).

Spinal cord synaptosome preparation

The spinal cord tissues at the L5 and L6 levels were collected and homogenized using a glass-Teflon homogenizer in 10 volumes of ice-cold HEPES-buffered sucrose (0.32 M sucrose, 4 mM HEPES, and 1 mM EGTA at pH 7.4) containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich). The homogenate was centrifuged at 1,000 × g at 4 °C for 10 min to remove sediment including large debris and nuclei. To obtain the crude synaptosomal fraction, the supernatant was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 15 min. The synaptosomal pellet was lysed in 9 volumes of ice-cold HEPES-buffer with the protease inhibitor cocktail for 30 min. The lysate was centrifuged at 25,000 × g at 4 °C for 20 min to obtain the synaptosomal membrane fraction. After the protein concentration was measured, 30 μg of proteins were used for Western blotting. Postsynaptic density-95 kDa protein (PSD-95), a known synaptic protein, was used as an internal loading control for synaptosomes. The amount of α2δ-1 and GluN1 in the spinal cord synaptosomes was normalized to the amount of PSD-95 in the same gels23. The following antibodies and concentrations were used for immunoblotting: rabbit anti-α2δ-1 (1:1,000; #ACC-015, Alomone Labs), rabbit anti-GluN1 (1:1000; #G8913, Sigma-Aldrich), and mouse anti-PSD95 (1:1,000; #75–348, NeuroMab, Davis, CA).

Spinal cord slice preparation and electrophysiological recordings

The lumbar spinal cord was rapidly removed through laminectomy from animals that had been anesthetized with isoflurane. The spinal cord tissues were immediately placed in ice-cold sucrose artificial cerebrospinal fluid presaturated with 95% O2 and 5% CO2. The fluid contained (in mM) 234 sucrose, 3.6 KCl, 1.2 MgCl2, 2.5 CaCl2, 1.2 NaH2PO4, 25.0 NaHCO3, and 12.0 glucose. The spinal cord tissue was then placed in a shallow groove formed in an agar block and glued to the stage of a vibratome (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). Transverse slices (400 μm thick) of the spinal cords were cut in ice-cold sucrose artificial cerebrospinal fluid and preincubated in Krebs solution oxygenated with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 at 34 °C for at least 1 h before being transferred to the recording chamber. The Krebs solution contained (in mM) 117.0 NaCl, 3.6 KCl, 2.5 CaCl2, 1.2 MgCl2, 1.2 NaH2PO4, 11.0 glucose, and 25.0 NaHCO3. The spinal cord slices in a recording chamber were perfused with Krebs solution at 5.0 ml/min at 34℃. The lamina II outer neurons were visualized and selected for recording because they predominantly receive nociceptive input and are mostly glutamate-releasing excitatory neurons27–29.

Excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) were recorded using whole-cell voltage-clamp techniques. The impedance of the glass electrode was 4 to 7 MΩ when the pipette was filled with an internal solution containing (in mM) 135.0 potassium gluconate, 2.0 MgCl2, 0.5 CaCl2, 5.0 KCl, 5.0 HEPES, 5.0 EGTA, 5.0 ATP-Mg, 0.5 Na-GTP, and 10 QX314 (280 – 300 mosM, adjusted to pH 7.25 with 1.0 M KOH). EPSCs were evoked from the dorsal root using a bipolar tungsten electrode connected to a stimulator (0.5 ms, 0.6 mA and 0.1 Hz). Monosynaptic EPSCs were recorded on the basis of the constant latency and absence of conduction failure of evoked EPSCs in response to a 20-Hz electrical stimulation, as we described previously27,28. To determine the treatment presynaptic effect, two EPSCs were evoked by a pair of electrical stimulating pulses (at 50-ms intervals) applied to the dorsal root. The paired-pulse ratio (PPR) of EPSCs was calculated as the ratio of the amplitude of the second synaptic response to the amplitude of the first synaptic response from each trial28. Miniature EPSCs (mEPSCs) were recorded at a holding potential of −60 mV in the presence of 10 μM bicuculline, 2 μM strychnine, and 1 μM tetrodotoxin. The input resistance was monitored, and the recording was abandoned if the input resistance changed by more than 15%. All signals were recorded using an amplifier (MultiClamp700B; Axon Instruments Inc., Union City, CA), filtered at 1 to 2 kHz, and digitized at 10 kHz.

All drugs were prepared in artificial cerebrospinal fluid before the recording and delivered via syringe pumps to reach their final concentrations. Tetrodotoxin citrate (TTX) and 2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid (AP5) were purchased from Hello Bio Inc. (Princeton, NJ).

Behavioral assessment of nociception

To quantify the mechanical nociceptive threshold in rats and mice, we conducted the paw pressure (Randall-Selitto) test on the left hindpaw using an analgesiometer (Ugo Basile, Varese, Italy). To activate the device, we pressed a foot pedal that applied a constantly increasing force on a linear scale. When the animal withdrew the paw or vocalized, the pedal was immediately released, and the scale of the withdrawal threshold was recorded30. A maximum pressure of 400 g (in rats) or 200 g (in mice) was used to avoid potential tissue injury to the animals.

To assess the thermal sensitivity of the hindpaw, rats or mice were lightly restrained in a small enclosure placed on the glass surface maintained constant at 30 °C (IITC Life Sciences, Woodland Hills, CA). We allowed them to acclimate for 30 min before testing. A mobile radiant heat source located under the glass was focused onto the hindpaw of each animal. The paw withdrawal latency was recorded with a timer, and the hindpaw was tested twice to obtain the average. A cut-off of 30 s was used to prevent potential tissue damage2,31.

Rotarod performance test was conducted using a rotarod accelerator treadmill (Med Associates Inc., St. Albans, VT) to determine motor function of rats as previously described32. The falling latency was measured from the start of the acceleration until the rat fell off the drum.

Study design and data analysis

Data are expressed as means ± SD. No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample sizes for the studies, but our sample sizes were based on our previous experience with similar studies and were similar to those generally employed in the field. Animals were randomly assigned (1:1 allocation) to receive saline, α2δ-1Tat peptide, control peptide, or gabapentin. At least three animals were used for each recording protocol, and only one neuron was recorded from each spinal cord slice. The amplitude of the evoked EPSCs was quantified by averaging 6 consecutive EPSCs using Clampfit software (version 10.0, Axon Instruments). The mEPSCs were analyzed off-line using the peak detection program MiniAnalysis (Synaptosoft, Leonia, NJ). The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to compare the cumulative probability of the amplitude and inter-event interval of mEPSCs. The primary outcomes of electrophysiological experiments are changes in the frequency of mEPSCs and the amplitude of evoked EPSCs. In biochemical experiments, the primary outcome is the target protein levels. The primary outcome of the behavioral experiments is the altered withdrawal threshold and latency. For the biochemical and electrophysiological data, two-tailed paired t tests were used to compare two groups, and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post hoc test was used to evaluate differences among more than two groups. Two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test was used for the comparison of differences in behavioral data between groups/subjects (vs. vehicle/control peptide/wild-type groups) and the differences within subjects (vs. the pretreatment baseline control). The investigators performing the behavioral and electrophysiological experiments were blinded to the treatment and genotypes. Outliers were not evaluated, and no data were excluded from statistical analysis. All statistical analyses were performed using Prism software (version 7, GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA). P values of less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Chronic morphine treatment increases the prevalence of α2δ-1–NMDAR complexes in the DRG and spinal cord

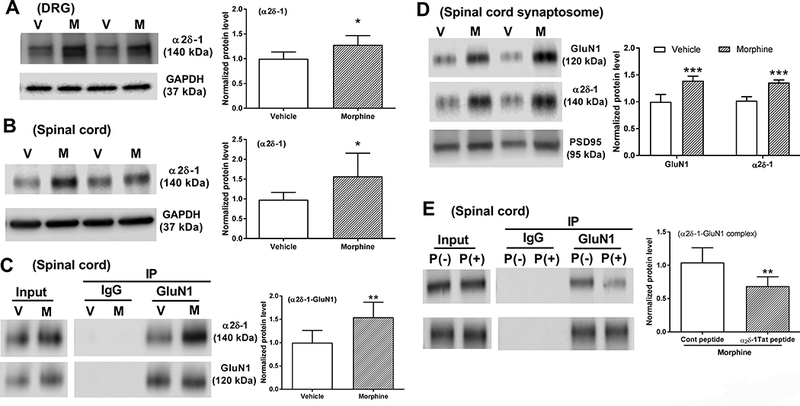

To determine whether chronic administration of morphine alters α2δ-1 expression levels, we measured α2δ-1 protein amounts in DRG and dorsal spinal cord tissues from morphine- and vehicle-treated rats. Morphine (5 mg/kg) or vehicle was injected intraperitoneally twice a day for 8 consecutive days. Immunoblotting analysis using total proteins showed that α2δ-1 levels in both the DRG (p = 0.039, t(10) = 2.37, n = 6 rats/group; Fig. 1A) and dorsal spinal cord (p = 0.014, t(10) = 2.97; n = 6 rats/group; Fig. 1B) were significantly higher in morphine-treated rats than in vehicle-treated rats.

Figure 1. Chronic morphine treatment increases α2δ-1 association with NMDARs at spinal cord synapses.

A and B, Representative blots and quantification of α2δ-1 protein levels in the DRG (A) and dorsal spinal cord (B) from vehicle-treated (V) and morphine-treated (M) rats (n = 6 rats in each group). C, Coimmunoprecipitation analysis shows that GluN1 coprecipitated with α2δ-1 in the membrane extracts of dorsal spinal cord tissues of rats treated with vehicle or morphine for 8 days (n = 6 rats in each group). The amount of α2δ-1 proteins was normalized to that of GluN1 in the same sample, and the mean α2δ-1 level in vehicle-treated rats was considered to be 1. D, Representative gel images and quantification of GluN1 and α2δ-1 protein amounts in dorsal spinal cord synaptosomes from vehicle- and morphine-treated rats (n = 6 rats in each group). E, Coimmunoprecipitation analysis shows the effect of treatment with 1 μM α2δ-1Tat peptide and scrambled control peptide on the α2δ-1-GluN1 complex level in spinal cord slices from morphine-treated rats (n = 6 rats in each group). Data are shown as means ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. the vehicle or control peptide group.

To determine whether chronic morphine treatment affects the physical interaction between α2δ-1 and NMDARs in vivo, we conducted coimmunoprecipitation analyses using membrane extracts of dorsal spinal cords obtained from vehicle-treated and morphine-treated rats. Using specific antibodies, GluN1, an obligatory subunit of NMDARs, was coprecipitated with α2δ-1 in the dorsal spinal cord. The amounts of the α2δ-1–GluN1 protein complex in the dorsal spinal cord were significantly higher in morphine-treated rats than in vehicle-treated rats (p = 0.009, t(10) = 3.213, n = 6 rats/group; Fig. 1C).

α2δ-1 primarily increases synaptic NMDAR activity via promoting NMDAR trafficking23. We therefore determined whether chronic morphine exposure increases synaptic targeting of α2δ-1 and NMDARs. Immunoblotting analysis using synaptosomes isolated from the dorsal spinal cord showed that both GluN1 (p < 0.001, t(10) = 6.056; n = 6 rats/group, Fig. 1D) and α2δ-1 (p < 0.001, t(10) = 9.285, n = 6 rats/group; Fig. 1D) protein amounts were significantly higher in morphine-treated rats than in vehicle-treated rats. These results indicate that chronic opioid treatment causes α2δ-1 upregulation and increases the α2δ-1–NMDAR interaction at spinal cord synapses.

The C terminus of α2δ-1 is required for its interaction with NMDARs23, and a Tat (YGRKKRRQRRR)-fused 30-amino-acid peptide (VSGLNPSLWSIFGLQFILLWLVSGSRHYLW) effectively disrupts the α2δ-1–NMDAR interaction in vivo23,33. To determine the ability of α2δ-1Tat peptide to disrupt the α2δ-1–NMDA interaction in the spinal cord of morphine-treated rats, we conducted coimmunoprecipitation analyses using membrane extracts of spinal cord tissue sections treated with 1 μM Tat-fused scrambled control peptide (FGLGWQPWSLSFYLVWSGLILSVLHLIRSN) or 1 μM α2δ-1Tat peptide for 30 min. Treatment with α2δ-1Tat peptide significantly reduced the level of the α2δ-1–GluN1 protein complex in the dorsal spinal cord, compared with that treated with the control peptide (p = 0.008, t(10) = 3.331, n = 6 rats/group; Fig. 1E).

α2δ-1 mediates chronic morphine treatment-induced potentiation of presynaptic NMDAR activity in the spinal cord

Chronic morphine treatment increases presynaptic NMDAR activity but diminishes postsynaptic NMDAR, activity in the spinal dorsal horn4. Gabapentin binds primarily to α2δ-134,35 and is a clinically used α2δ-1 inhibitory ligand. Thus, we used gabapentin to determine whether α2δ-1 contributes to the increased presynaptic NMDAR activity in the spinal cord induced by chronic morphine treatment. We recorded glutamatergic mEPSCs, which reflect spontaneous quantal release of glutamate from presynaptic terminals4. In vehicle-incubated spinal cord slices from morphine-treated rats, bath application of 50 μM AP5, a specific NMDAR antagonist, reversed the increased frequency of mEPSCs in dorsal horn neurons (4.95 ± 1.06 Hz vs. 6.74 ± 1.09 Hz, p = 0.007, F(5,57) = 10.84, n = 11 neurons; Fig. 2, A and B). These results suggest that chronic morphine exposure increases the activity of presynaptic NMDARs in the spinal dorsal horn, as shown previously4. In spinal cord slices from morphine-treated rats, gabapentin pretreatment (100 μM for 60 min) substantially reduced the baseline frequency (4.44 ± 1.29 Hz vs. 6.74 ± 1.09 Hz, p < 0.001, F(5,57) = 10.84), but not the amplitude, of mEPSCs in dorsal horn neurons (n = 10 neurons, Fig. 2, C and D). In these neurons, subsequent bath application of 50 μM AP5 had no effect on the frequency or amplitude of mEPSCs (Fig. 2, C and D).

Figure 2. α2δ-1 mediates chronic morphine exposure-induced potentiation of presynaptic NMDAR activity in the spinal dorsal horn.

A, Representative recording traces and cumulative plots show the effect of bath application of 50 μM AP5 on the frequency and amplitude of mEPSCs of a lamina II neuron from a morphine-treated rat. B, Summary data show the effect of 50 μM AP5 on the mean frequency and amplitude of mEPSCs of lamina II neurons (n = 11 neurons) from morphine-treated rats. C, Representative recording traces and cumulative plots show that bath application of 50 μM AP5 had no effect on the frequency or amplitude of mEPSCs of a lamina II neuron pretreated with 100 μM gabapentin from a morphine-treated rat. D, Summary data show no effect from 50 μM AP5 on the mean frequency or amplitude of mEPSCs of lamina II neurons (n = 10 neurons) pretreated with 100 μM gabapentin from morphine-treated rats. Data are shown as means ± SD. **P < 0.01 vs. the baseline. ###P < 0.001 vs. the baseline in the morphine + vehicle group.

Furthermore, to determine the role of α2δ-1 in NMDAR-mediated synaptic glutamate release from central terminals of primary afferent nerves, we examined the effect of gabapentin on the amplitude of monosynaptic EPSCs evoked from the dorsal root. In vehicle-incubated spinal cord slices from morphine-treated rats, bath application of 50 μM AP5 significantly reduced the amplitude of monosynaptic EPSCs (375.0 ± 85.3 pA vs. 511.3 ± 70.0 pA, p < 0.001, F(5,57) = 8.73) and increased the paired-pulse ratio (PPR, 0.61 ± 0.28 vs. 0.85 ± 0.40, p = 0.038, F(5,57) = 4.20) of monosynaptically evoked EPSCs of lamina II neurons (n = 10 neurons, Fig. 3, A–C). These data are consistent with our previous findings4. Gabapentin incubation (100 μM for 60 min) of spinal cord slices from morphine-treated rats considerably reduced the baseline amplitude of evoked EPSCs of lamina II neurons (398.4 ± 44.6 pA vs. 511.3 ± 70.0 pA, p = 0.003, F(5,57) = 8.73; Fig. 3, C and F). After gabapentin incubation, further bath application of AP5 had no significant effect on the amplitude or PPR of evoked EPSCs of lamina II neurons (n = 10 neurons, Fig. 3, D–F). These findings suggest that α2δ-1 plays a crucial role in the increase in presynaptic NMDAR activity in the spinal cord induced by chronic opioid treatment.

Figure 3. α2δ-1 is involved in chronic morphine exposure-induced potentiation of NMDAR activity at primary afferent terminals in the spinal dorsal horn.

A and B, Representative recording traces show the effect of bath application of 50 μM AP5 on evoked monosynaptic EPSCs (A) and the paired-pulse ratio (PPR, B) of a vehicle-incubated lamina II neuron from a morphine-treated rat. C, Summary data show the effect of 50 μM AP5 on the amplitude (n = 10 neurons) and PPR (n = 10 neurons) of evoked monosynaptic EPSCs of vehicle-incubated lamina II neurons in morphine-treated rats. D and E, Representative recording traces show no effect from bath application of 50 μM AP5 on the amplitude of monosynaptically evoked EPSCs (D) or the PPR (E) of a lamina II neuron in spinal cord slices pretreated with 100 μM gabapentin in a morphine-treated rat. F, Summary data show no effect from 50 μM AP5 on the mean amplitude (n = 11 neurons) or PPR (n = 11 neurons) of monosynaptic EPSCs of lamina II neurons pretreated with 100 μM gabapentin from morphine-treated rats. Data are shown as means ± SD. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001 vs. the baseline. ##P < 0.01 vs. the baseline in the morphine + vehicle group.

α2δ-1 is essential for chronic morphine exposure-induced tonic activity of NMDARs at primary afferent terminals

To validate the critical role of α2δ-1 in the opioid-induced increase in presynaptic NMDAR activity, we used Cacna2d1 KO (Cacna2d1−/−) mice. Spinal dorsal horn neurons from morphine-treated Cacna2d1 KO mice had lower baseline mEPSC frequencies than did neurons from morphine-treated WT mice (4.81 ± 0.54 Hz vs. 6.21 ± 1.17 Hz, p = 0.007, F(5,57) = 10.55; Fig. 4). Bath application of AP5 (50 μM) significantly reduced the baseline frequency of mEPSCs in dorsal horn neurons from morphine-treated WT mice (4.10 ± 1.00 Hz vs. 6.21 ± 1.17 Hz, p < 0.001, F(5,57) = 10.55, n =11 neurons; Fig. 4, A and B). In contrast, in dorsal horn neurons from morphine-treated Cacna2d1 KO mice, application of AP5 had no significant effect on the frequency or amplitude of mEPSCs (n = 10 neurons, Fig. 4, C and D).

Figure 4. α2δ-1 is essential for the chronic morphine exposure-induced activation of presynaptic NMDARs in the spinal dorsal horn.

A, Representative recording trace and cumulative plots show the effect of bath application of 50 μM AP5 on the frequency and amplitude of mEPSCs of a lamina II neuron from a morphine-treated WT mouse. B, Summary data show the effect of 50 μM AP5 on the mean frequency and amplitude of mEPSCs (n = 11 neurons) in spinal cord slices from morphine-treated WT mice. C, Representative recording traces and cumulative plots show no effect from AP5 on the frequency or amplitude of mEPSCs of a lamina II neuron from a morphine-treated α2δ-1 KO mouse. D, Summary data show no effect of AP5 on the mean frequency or amplitude of mEPSCs (n = 10 neurons) in spinal cord slices from morphine-treated α2δ-1 KO mice. Data are shown as means ± SD. ***P < 0.001 vs. the baseline. ##P < 0.01 vs. the baseline in the WT group.

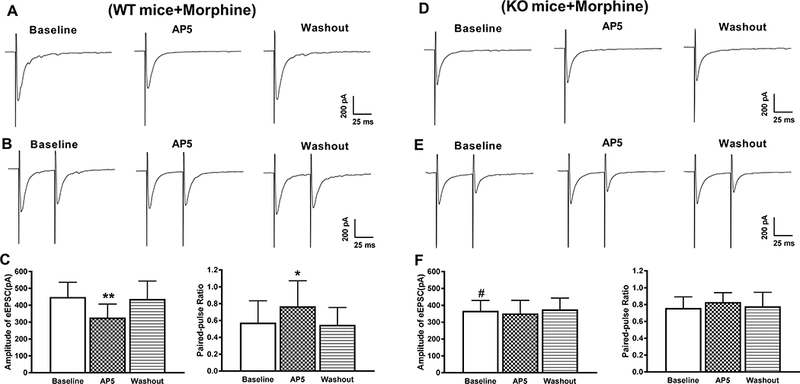

Furthermore, the baseline amplitude of monosynaptic EPSCs evoked from the dorsal root in spinal cord slices from morphine-treated WT mice was significantly higher than in those from morphine-treated Cacna2d1 KO mice (449.1 ± 87.0 pA vs. 368.0 ± 61.3 pA, p = 0.04, F(5,60) = 5.58; Fig. 5). In dorsal horn neurons from morphine-treated WT mice, bath application of 50 μM AP5 significantly reduced the amplitude of monosynaptic EPSCs (327.1 ± 80.3 pA vs. 449.1 ± 87.0 pA, p = 0.003, F(5,60) = 5.58) and increased the PPR (0.57 ± 0.26 vs. 0.77 ± 0.30, p = 0.02, F(5,60) = 5.04) of evoked EPSCs (n =11 neurons, Fig. 5, A–C). However, in dorsal horn neurons from morphine-treated Cacna2d1 KO mice, AP5 had no effect on the amplitude or the PPR of monosynaptic EPSCs (n = 11 neurons, Fig. 5, D–F). These data provide unequivocal evidence that α2δ-1 is essential for the opioid-induced increase in presynaptic NMDAR activity at the spinal cord level.

Figure 5. α2δ-1 is required for the chronic morphine exposure-induced increase in NMDAR activity at primary afferent terminals.

A and B, Representative current traces show the effect of bath application of 50 μM AP5 on the amplitude of monosynaptic EPSCs (A) and the PPR (B) of a lamina II neuron from a morphine-treated WT mouse. C, Summary data show the effect of 50 μM AP5 on the mean amplitude (n = 11 neurons) and PPR (n = 11 neurons) of monosynaptic EPSCs of lamina II neurons from spinal cord slices of morphine-treated WT mice. C and D, Representative current traces show no effect of AP5 on the mean amplitude of evoked monosynaptic EPSCs (C) or PPR (D) of a lamina II neuron of a morphine-treated α2δ-1 KO mouse. E, Group data show the lack of effect of 50 μM AP5 on the amplitude (n = 11 neurons) and the PPR (n = 11 neurons) of monosynaptic EPSCs of lamina II neurons from spinal cord slices of morphine-treated α2δ-1 KO mice. Data are shown as means ± SD. **P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. the baseline. #P < 0.05 vs. the baseline in the WT group.

α2δ-1-bound NMDARs are required for the morphine-induced increase in presynaptic NMDAR activity in the spinal cord

We next used α2δ-1Tat peptide to determine the role of α2δ-1–bound NMDARs in the opioid-induced increase in presynaptic NMDAR activity. In dorsal horn neurons from morphine-treated rats, the frequency, but not the amplitude, of mEPSCs was significantly lower in slices incubated with the α2δ-1Tat peptide (1 μM for 60 min) than in slices incubated with a Tat-fused scrambled control peptide (1 μM for 60 min) (4.10 ± 0.78 Hz vs. 6.60 ± 0.92 Hz, p < 0.001, F(5,57) = 20.87; Fig. 6). Furthermore, bath application of 50 μM AP5 significantly reduced the frequency of mEPSCs in control peptide-incubated dorsal horn neurons from morphine-treated rats (4.65 ± 0.91 Hz vs. 6.60 ± 0.92 Hz, p < 0.001, F(5,57) = 20.87, n =10 neurons; Fig. 6, A and B). In contrast, AP5 had no effect on the frequency of mEPSCs in α2δ-1Tat peptide-incubated dorsal horn neurons from morphine-treated rats (n = 11 neurons; Fig. 6, C and D).

Figure 6. α2δ-1–bound NMDARs mediate the chronic morphine exposure-induced increase in presynaptic NMDAR activity in the spinal cord.

A, Representative recording traces and cumulative plots show the effect of bath application of 50 μM AP5 on the frequency and amplitude of mEPSCs of a lamina II neuron pretreated with control peptide (1 μM) from a spinal cord slice of a morphine-treated rat. B, Summary data show the effect of 50 μM AP5 on the mean frequency and amplitude of mEPSCs (n = 10 neurons) in spinal cord slices pretreated with control peptide from morphine-treated rats. C, Representative recording traces and cumulative plots show no effect of AP5 on the frequency or amplitude of mEPSCs of a lamina II neuron pretreated with α2δ-1Tat peptide (1 μM) from a spinal cord slice of a morphine-treated rat. D, Summary data show no effect of AP5 on the mean frequency or amplitude of mEPSCs (n = 11 neurons) in spinal cord slices pretreated with α2δ-1Tat peptide from morphine-treated rats. Data are shown as means ± SD. ***P < 0.001 vs. the baseline. ###P < 0.001 vs. the baseline in the morphine + control peptide group.

We also examined whether the α2δ-1Tat peptide affects the morphine-induced activation of NMDARs at primary afferent terminals in spinal cord slices obtained from morphine-treated rats. The amplitude of monosynaptic EPSCs of dorsal horn neurons was significantly higher in the Tat-fused control peptide-incubated group than in the α2δ-1Tat peptide-incubated group (503.0 ± 34.3 pA vs. 394.2 ± 51.5 pA, p < 0.001, F(5,60) = 15.74; Fig. 7). Bath application of 50 μM AP5 markedly reduced the amplitude (388.5 ± 39.4 pA vs. 503.0 ± 34.3 pA, p < 0.001, F(5,60) = 15.74) and increased the PPR (0.63 ± 0.25 vs. 0.87 ± 0.27, p = 0.002, F(5,60) = 4.30) of monosynaptic EPSCs in control peptide-incubated dorsal horn neurons from morphine-treated rats (n = 11 neurons, Fig. 7, A–C). In contrast, in spinal cord slices treated with α2δ-1Tat peptide (1 μM for 60 min), further application of AP5 had no significant effect on the amplitude of evoked monosynaptic EPSCs (n = 11 neurons; Fig. 7, D and F) or the PPR of evoked EPSCs (n = 11 neurons; Fig. 7, E and F). These findings indicate that α2δ-1–bound NMDARs are indispensable for opioid-induced activation of presynaptic NMDARs in the spinal dorsal horn.

Figure 7. α2δ-1–bound NMDARs are critically involved in chronic morphine exposure-induced activation of NMDARs at primary afferent terminals.

A and B, Representative current traces show the effect of bath application of 50 μM AP5 on the amplitude of monosynaptic EPSCs (A) and the PPR (B) of a lamina II neuron from a spinal cord slice pretreated with control peptide (1 μM) from a morphine-treated rat. C, Summary data show the effect of 50 μM AP5 on the mean amplitude (n = 11 neurons) and PPR (n = 11 neurons) of monosynaptic EPSCs of lamina II neurons from spinal cord slices pretreated with control peptide from morphine-treated rats. C and D, Representative current traces show no effect of AP5 on the amplitude of evoked monosynaptic EPSCs (C) or PPR (D) of a lamina II neuron from a spinal cord slice pretreated with α2δ-1Tat peptide (1 μM) from a morphine-treated rat. E, Summary data show no effect of AP5 on the mean amplitude (n = 11 neurons) or PPR (n = 11 neurons) of monosynaptic EPSCs of lamina II neurons from spinal cord slices pretreated with α2δ-1Tat peptide from morphine-treated rats. Data are shown as means ± SD. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. the baseline. ###P < 0.001 vs. the baseline in the morphine + control peptide group.

α2δ-1-bound NMDARs at the spinal cord level mediate opioid-induced hyperalgesia and analgesic tolerance

Having shown the importance of α2δ-1–bound NMDARs in the opioid-induced increase in presynaptic NMDAR activity, we next determined whether α2δ-1 also contributes to opioid-induced hyperalgesia and analgesic tolerance. We administered intraperitoneal morphine (5 mg/kg, twice a day) to rats for 8 consecutive days4,7. We examined the withdrawal thresholds in response to noxious pressure and heat stimuli 30 min before (baseline) and 30 min after morphine injection (5 mg/kg) each day. We injected 100 mg/kg gabapentin (or vehicle) intraperitoneally or 1 μg α2δ-1Tat peptide or control peptide intrathecally 20 min before each morphine treatment in separate groups of rats. Gabapentin and α2δ-1Tat peptide do not affect the acute nociceptive thresholds in naïve animals23,36,37.

Daily morphine injection in vehicle-treated (n = 8 rats) or control peptide-treated (n = 10 rats) rats caused a gradual reduction in the baseline withdrawal thresholds, indicating the presence of mechanical and thermal hyperalgesia (Fig. 8, A–D). These rats also showed a gradual decrease in the anti-nociceptive effect of morphine. By day 6, intraperitoneal injection of 5 mg/kg morphine failed to produce a significant effect on withdrawal thresholds, indicating the development of analgesic tolerance (Fig. 8, A–D). In contrast, co-treatment with gabapentin (n = 8 rats) or α2δ-1Tat peptide (n = 10 rats) completely blocked the reduction in baseline withdrawal thresholds induced by chronic morphine injections (Fig. 8, A–D). Furthermore, co-treatment with gabapentin or α2δ-1Tat peptide substantially attenuated the reduction in the analgesic effect of morphine. Even at day 8, injection of 5 mg/kg morphine still significantly increased the nociceptive mechanical and thermal withdrawal thresholds in co-treated rats (Fig. 8, A–D). To determine whether gabapentin treatment affects motor performance, we conducted rotarod tests in rats 30 min after intraperitoneal injection of 100 mg/kg gabapentin or 5 mg/kg morphine. The falling latency was not significantly affected by gabapentin (157.0 ± 26.5 s vs. 153.6 ± 21.2 s) or morphine (155.9± 18.3 s vs. 154.4 ± 24.1 s) treatment.

Figure 8. α2δ-1 at the spinal cord level mediates chronic morphine exposure-induced hyperalgesia and analgesic tolerance.

A and B, Time course of changes in the baseline mechanical (A) and thermal (B) withdrawal thresholds and the analgesic effect of morphine in rats treated with systemic morphine plus vehicle (n = 8 rats) or gabapentin (100 mg/kg, n = 8 rats). C and D, Time course of changes in the baseline mechanical (C) and thermal (D) withdrawal thresholds and the analgesic effect of morphine in rats treated with systemic morphine plus control peptide (1 μg) or α2δ-1Tat peptide (1 μg) (n = 10 rats in each group). E and F, Time course of changes in the baseline mechanical (E) and thermal (F) withdrawal thresholds and the analgesic effect of morphine in WT and α2δ-1 KO mice (n = 8 mice per group). The baseline withdrawal threshold was measured before each morphine injection, and the analgesic effect of morphine was tested 30 min after morphine injection. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. values at day 1. Data are shown as means ± SD. #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 vs. values in the corresponding control group (vehicle, control peptide, or WT) at the same time point.

We then used Cacna2d1 KO mice to validate the role of α2δ-1 in opioid-induced hyperalgesia and analgesic tolerance. In WT mice, twice-daily intraperitoneal injection of morphine (10 mg/kg) for 8 consecutive days gradually reduced the baseline withdrawal thresholds in response to noxious pressure and heat stimuli and diminished the anti-nociceptive effect of morphine (n = 8 mice, Fig. 8, E,F). However, in Cacna2d1 KO mice, daily morphine injections did not significantly affect the baseline withdrawal threshold. Also, the anti-nociceptive effect of morphine was largely preserved at the end of 8-day morphine treatment in Cacna2d1 KO mice (n = 8 mice, Fig. 8, E,F).

In addition, we determined whether gabapentin or α2δ-1Tat peptide can reverse the established hyperalgesia and analgesic tolerance caused by chronic morphine treatment. Rats were first treated with morphine (5 mg/kg, twice a day) for 8 days and then tested after a single intraperitoneal injection of gabapentin (100 mg/kg) or vehicle) or a single intrathecal injection of 1 μg α2δ-1Tat peptide or control peptide with or without intraperitoneal administration of morphine (5 mg/kg). Treatment with gabapentin or α2δ-1Tat peptide (n = 8 rats) significantly reduced baseline mechanical and thermal hyperalgesia induced by chronic morphine administration (n = 8 rats in each group, Fig. 9, A–D). Moreover, co-treatment with gabapentin and morphine or α2δ-1Tat peptide and morphine significantly potentiated on antinociceptive effect of morphine (n = 8 rats in each group, Fig. 9, A–D). Together, these findings indicate that α2δ-1–bound NMDARs at the spinal cord level play a crucial role in the development of opioid-induced hyperalgesia and analgesic tolerance.

Figure 9. Treatment with gabapentin or α2δ-1Tat peptide attenuates established hyperalgesia and analgesic tolerance induced by chronic morphine treatment.

A and B, Effect of intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of vehicle or gabapentin (100 mg/kg, i.p.) on the baseline mechanical (A) and heat (B) withdrawal thresholds and the acute analgesic effect of morphine (5 mg/kg, i.p.) in rats pretreated with chronic morphine for 8 days (n = 8 rats in each groups). C and D, Effect of intrathecal injection of α2δ-1Tat peptide (1 μg) or control peptide (1 μg) on the baseline mechanical (C) and heat (D) withdrawal thresholds and the acute analgesic effect of morphine (5 mg/kg, i.p.) in rats pretreated with chronic morphine for 8 days (n = 8 rats in each group). BL, pre-morphine treatment baseline. Data are shown as means ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. values at time 0. #P < 0.05, ###P < 0.001 vs. corresponding values in the vehicle or control peptide group at the same time point.

Discussion

Our knowledge of the molecular mechanisms underlying opioid-induced hyperalgesia and analgesic tolerance is still fragmentary. Hyperalgesia and analgesic tolerance, two seemingly unrelated phenomena, may share common neural substrates that act at NMDARs, which are involved in the development of both opioid-induced hyperalgesia and opioid-induced analgesic tolerance4,8,9. In the present study, chronic morphine treatment not only increased α2δ-1 protein levels but also potentiated the physical association between α2δ-1 and NMDARs in the spinal cord. It has been shown that protein kinase C play a major role in opioid-induced hyperalgesia and analgesic tolerance and in presynaptic NMDAR hyperactivity in the spinal cord4,8. However, whether there is a potential link between α2δ-1–bound NMDARs and protein kinases in regulating NMDAR activity is still uncertain. Since increased protein phosphorylation can strengthen protein-protein binding complexes38, it is possible that protein kinase C potentiates phosphorylation of α2δ-1 and/or NMDAR proteins to promote their physical interactions by changing their physicochemical conformation. We also found that chronic morphine exposure increased the prevalence of α2δ-1–NMDAR complexes at spinal cord synapses. Therefore, opioid-induced hyperalgesia and analgesic tolerance are associated with increased synaptic expression of α2δ-1–NMDARs at the spinal cord level.

A major finding of our study is that α2δ-1–bound NMDARs are essential for the opioid-induced increase in presynaptic NMDAR activity at primary afferent terminals. In our study, the α2δ-1Tat peptide not only abolished aberrant presynaptic NMDAR activity in the spinal dorsal horn but also diminished the hyperalgesia and analgesic tolerance induced by chronic morphine treatment. Because we recorded mEPSCs in the presence of tetrodotoxin (a sodium channel blocker), VGCCs were not open in this recording condition. Therefore, α2δ-1 likely enhances the presynaptic NMDAR activity of spinal dorsal horn neurons independent of VGCCs. We have shown that the increased synaptic glutamate release to spinal dorsal horn neurons by chronic morphine administration is mediated by GluN2A- and GluN2B-containing NMDARs on primary afferent terminals4. In addition to promoting synaptic trafficking of NMDARs, α2δ-1 also reduces the Mg2+ block of GluN2A-containing NMDARs23, which may contribute to the potentiation of NMDAR activity by opioids. Because neither α2δ-1 genetic ablation nor α2δ-1Tat peptide had an effect on basal NMDAR activity in normal conditions23,39, α2δ-1–bound NMDARs seem to be preferentially responsible for opioid-induced presynaptic NMDAR hyperactivity. Our results, therefore, show that the interaction with NMDARs accounts for the crucial role of α2δ-1 in opioid-induced aberrant presynaptic NMDAR activity.

Our findings also provide strong evidence showing that gabapentin reduces opioid-induced hyperalgesia and analgesic tolerance primarily by targeting α2δ-1–bound NMDARs. Gabapentinoids can attenuate opioid-induced analgesic tolerance and hyperalgesia in animal models40–42, and gabapentin may also reduce opioid-induced hyperalgesia and opioid consumption in patients43,44 through a largely unknown mechanism. Although the therapeutic action of gabapentinoids, including gabapentin and pregabalin, is mediated by α2δ-1 binding23,26,35, gabapentinoids have no effect on the interaction between α2δ-1 and VGCC α1 subunits or VGCC activity in neurons and cell lines23,45,46. Gabapentin treatment (up to 7 days) does not affect VGCC trafficking or VGCC-dependent neurotransmitter release47. Also, the interaction between Cav2.2 and α2δ-1 is not disrupted by gabapentin48, which is confirmed by our recent study23. Our recent study reveals that gabapentinoids primarily target α2δ-1–bound NMDARs to normalize the nerve injury-induced increase in synaptic NMDAR activity in the spinal dorsal horn23. We showed in the present study that gabapentin fully reversed the NMDAR-mediated increase in the frequency of mEPSCs and the amplitude of EPSCs monosynaptically evoked from the dorsal root in chronically morphine-exposed rats. Our findings thus indicate that gabapentin alleviates opioid-induced hyperalgesia and analgesic tolerance by diminishing abnormal NMDAR activity at primary afferent terminals in the spinal cord. Nevertheless, our conclusion is based solely on the data from rodent models, and the effectiveness of gabapentinoids in reducing opioid-induced hyperalgesia and analgesic tolerance should be further validated in clinical studies.

In conclusion, our study provides new evidence that chronic opioid treatment causes upregulation of α2δ-1 and enhances the association between α2δ-1 and NMDARs in the spinal cord. Our findings support the notion that α2δ-1–bound NMDARs are critically involved in opioid-induced tonic activation of presynaptic NMDARs in the spinal cord, which augments glutamatergic input to spinal dorsal horn neurons to cause hyperalgesia and analgesic tolerance. This information is important for understanding the mechanisms of opioid-induced synaptic plasticity and suggests new strategies for improving the analgesic efficacy of opioids by eliminating aberrant presynaptic NMDAR activation. We demonstrated that gabapentin and α2δ-1Tat peptide not only prevented opioid-induced hyperalgesia and analgesic tolerance but also reversed established hyperalgesia and tolerance induced by chronic opioid administration. Gabapentinoids and α2δ-1 C-terminus–interfering peptides do not affect physiological α2δ-1–free NMDARs and could therefore be used to avoid the adverse effects associated with the use of general NMDAR antagonists, such as ketamine. Thus, targeting α2δ-1–bound NMDARs is a more desirable approach to managing opioid-induced hyperalgesia and analgesic tolerance than blocking total NMDARs with non-selective NMDAR antagonists.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (Grant R01 DA041711) and the N.G. and Helen T. Hawkins Endowment (to H.-L.P.).

The abbreviations used are:

- AP5

2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid

- DRG

dorsal root ganglion

- EPSC

excitatory postsynaptic current

- KO

knockout

- mEPSC

miniature excitatory postsynaptic current

- NMDAR

N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor

- PPR

paired-pulse ratio

- VGCC

voltage-gated Ca2+ channel

- WT

wild-type

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests with the contents of this study.

References

- 1.Ferrini F, Trang T, Mattioli TAM, Laffray S, Del’Guidice T, Lorenzo LE, Castonguay A, Doyon N, Zhang WB, Godin AG, Mohr D, Beggs S, Vandal K, Beaulieu JM, Cahill CM, Salter MW, De Koninck Y: Morphine hyperalgesia gated through microglia-mediated disruption of neuronal Cl- homeostasis. Nat Neurosci 2013; 16: 183–192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen SR, Pan HL: Loss of TRPV1-expressing sensory neurons reduces spinal mu opioid receptors but paradoxically potentiates opioid analgesia. J Neurophysiol 2006; 95: 3086–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen SR, Pan HL: Blocking mu opioid receptors in the spinal cord prevents the analgesic action by subsequent systemic opioids. Brain Res 2006; 1081: 119–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao YL, Chen SR, Chen H, Pan HL: Chronic opioid potentiates presynaptic but impairs postsynaptic N-methyl-D-aspartic acid receptor activity in spinal cords: implications for opioid hyperalgesia and tolerance. J Biol Chem 2012; 287: 25073–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corder G, Tawfik VL, Wang D, Sypek EI, Low SA, Dickinson JR, Sotoudeh C, Clark JD, Barres BA, Bohlen CJ, Scherrer G: Loss of mu opioid receptor signaling in nociceptors, but not microglia, abrogates morphine tolerance without disrupting analgesia. Nat Med 2017; 23: 164–173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sun J, Chen SR, Chen H, Pan HL: mu-Opioid receptors in primary sensory neurons are essential for opioid analgesic effect on acute and inflammatory pain and opioid-induced hyperalgesia. J Physiol 2018: December 22. doi: 10.1113/JP277428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen SR, Prunean A, Pan HM, Welker KL, Pan HL: Resistance to morphine analgesic tolerance in rats with deleted transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1-expressing sensory neurons. Neuroscience 2007; 145: 676–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mao J, Price DD, Mayer DJ: Thermal hyperalgesia in association with the development of morphine tolerance in rats: roles of excitatory amino acid receptors and protein kinase C. J Neurosci 1994; 14: 2301–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trujillo KA, Akil H: Inhibition of morphine tolerance and dependence by the NMDA receptor antagonist MK-801. Science 1991; 251: 85–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Song L, Wu CR, Zuo YX: Melatonin prevents morphine-induced hyperalgesia and tolerance in rats: role of protein kinase C and N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors. Bmc Anesthesiology 2015; 15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang X, Chen S, Chen H, Pan H, Zhao Y: Inhibition of beta-ARK1 Ameliorates Morphine-induced Tolerance and Hyperalgesia Via Modulating the Activity of Spinal NMDA Receptors. Mol Neurobiol 2018; 55: 5393–5407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zeng J, Thomson LM, Aicher SA, Terman GW: Primary afferent NMDA receptors increase dorsal horn excitation and mediate opiate tolerance in neonatal rats. J Neurosci 2006; 26: 12033–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou HY, Chen SR, Byun HS, Chen H, Li L, Han HD, Lopez-Berestein G, Sood AK, Pan HL: N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor- and calpain-mediated proteolytic cleavage of K+-Cl- cotransporter-2 impairs spinal chloride homeostasis in neuropathic pain. J Biol Chem 2012; 287: 33853–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu H, Wang H, Sheng M, Jan LY, Jan YN, Basbaum AI: Evidence for presynaptic N-methyl-D-aspartate autoreceptors in the spinal cord dorsal horn. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1994; 91: 8383–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xie JD, Chen SR, Chen H, Zeng WA, Pan HL: Presynaptic N-Methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) Receptor Activity Is Increased Through Protein Kinase C in Paclitaxel-induced Neuropathic Pain. J Biol Chem 2016; 291: 19364–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chazan S, Ekstein MP, Marouani N, Weinbroum AA: Ketamine for acute and subacute pain in opioid-tolerant patients. J Opioid Manag 2008; 4: 173–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Loftus RW, Yeager MP, Clark JA, Brown JR, Abdu WA, Sengupta DK, Beach ML: Intraoperative ketamine reduces perioperative opiate consumption in opiate-dependent patients with chronic back pain undergoing back surgery. Anesthesiology 2010; 113: 639–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cole RL, Lechner SM, Williams ME, Prodanovich P, Bleicher L, Varney MA, Gu G: Differential distribution of voltage-gated calcium channel alpha-2 delta (alpha2delta) subunit mRNA-containing cells in the rat central nervous system and the dorsal root ganglia. J Comp Neurol 2005; 491: 246–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luo ZD, Chaplan SR, Higuera ES, Sorkin LS, Stauderman KA, Williams ME, Yaksh TL: Upregulation of dorsal root ganglion (alpha)2(delta) calcium channel subunit and its correlation with allodynia in spinal nerve-injured rats. J Neurosci 2001; 21: 1868–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Newton RA, Bingham S, Case PC, Sanger GJ, Lawson SN: Dorsal root ganglion neurons show increased expression of the calcium channel alpha2delta-1 subunit following partial sciatic nerve injury. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 2001; 95: 1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muller CS, Haupt A, Bildl W, Schindler J, Knaus HG, Meissner M, Rammner B, Striessnig J, Flockerzi V, Fakler B, Schulte U: Quantitative proteomics of the Cav2 channel nano-environments in the mammalian brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010; 107: 14950–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Felsted JA, Chien CH, Wang D, Panessiti M, Ameroso D, Greenberg A, Feng G, Kong D, Rios M: Alpha2delta-1 in SF1(+) Neurons of the Ventromedial Hypothalamus Is an Essential Regulator of Glucose and Lipid Homeostasis. Cell Rep 2017; 21: 2737–2747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen J, Li L, Chen SR, Chen H, Xie JD, Sirrieh RE, MacLean DM, Zhang Y, Zhou MH, Jayaraman V, Pan HL: The α2δ-1-NMDA Receptor Complex Is Critically Involved in Neuropathic Pain Development and Gabapentin Therapeutic Actions. Cell Rep 2018; 22: 2307–2321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ma H, Chen SR, Chen H, Zhou JJ, Li DP, Pan HL: α2δ-1 Couples to NMDA Receptors in the Hypothalamus to Sustain Sympathetic Vasomotor Activity in Hypertension. J Physiol 2018: doi: 10.1113/JP276394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xie JD, Chen SR, Chen H, Pan HL: Bortezomib induces neuropathic pain through protein kinase C-mediated activation of presynaptic NMDA receptors in the spinal cord. Neuropharmacology 2017; 123: 477–487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fuller-Bicer GA, Varadi G, Koch SE, Ishii M, Bodi I, Kadeer N, Muth JN, Mikala G, Petrashevskaya NN, Jordan MA, Zhang SP, Qin N, Flores CM, Isaacsohn I, Varadi M, Mori Y, Jones WK, Schwartz A: Targeted disruption of the voltage-dependent calcium channel alpha2/delta-1-subunit. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2009; 297: H117–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li DP, Chen SR, Pan YZ, Levey AI, Pan HL: Role of presynaptic muscarinic and GABA(B) receptors in spinal glutamate release and cholinergic analgesia in rats. J Physiol 2002; 543: 807–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhou HY, Chen SR, Chen H, Pan HL: Opioid-induced long-term potentiation in the spinal cord is a presynaptic event. J Neurosci 2010; 30: 4460–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Santos SF, Rebelo S, Derkach VA, Safronov BV: Excitatory interneurons dominate sensory processing in the spinal substantia gelatinosa of rat. J Physiol 2007; 581: 241–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen SR, Hu YM, Chen H, Pan HL: Calcineurin inhibitor induces pain hypersensitivity by potentiating pre- and postsynaptic NMDA receptor activity in spinal cords. J Physiol 2014; 592: 215–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li L, Chen SR, Chen H, Wen L, Hittelman WN, Xie JD, Pan HL: Chloride Homeostasis Critically Regulates Synaptic NMDA Receptor Activity in Neuropathic Pain. Cell Rep 2016; 15: 1376–1383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cai YQ, Chen SR, Pan HL: Upregulation of nuclear factor of activated T-cells by nerve injury contributes to development of neuropathic pain. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2013; 345: 161–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luo Y, Ma H, Zhou J,J, Li L, Chen S,R, Zhang J, Chen L, Pan H,L: Focal Cerebral Ischemia and Reperfusion Induce Brain Injury through α2δ-1–Bound NMDA Receptors. Stroke 2018; 49: 2464–2472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gee NS, Brown JP, Dissanayake VU, Offord J, Thurlow R, Woodruff GN: The novel anticonvulsant drug, gabapentin (Neurontin), binds to the alpha2delta subunit of a calcium channel. J Biol Chem 1996; 271: 5768–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marais E, Klugbauer N, Hofmann F: Calcium channel alpha(2)delta subunits-structure and Gabapentin binding. Mol Pharmacol 2001; 59: 1243–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gilron I, Biederman J, Jhamandas K, Hong M: Gabapentin blocks and reverses antinociceptive morphine tolerance in the rat paw-pressure and tail-flick tests. Anesthesiology 2003; 98: 1288–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Urban MO, Ren K, Park KT, Campbell B, Anker N, Stearns B, Aiyar J, Belley M, Cohen C, Bristow L: Comparison of the antinociceptive profiles of gabapentin and 3-methylgabapentin in rat models of acute and persistent pain: implications for mechanism of action. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2005; 313: 1209–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nishi H, Hashimoto K, Panchenko AR: Phosphorylation in protein-protein binding: effect on stability and function. Structure 2011; 19: 1807–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ma H, Chen SR, Chen H, Li L, Li DP, Zhou JJ, Pan HL: alpha2delta-1 Is Essential for Sympathetic Output and NMDA Receptor Activity Potentiated by Angiotensin II in the Hypothalamus. J Neurosci 2018: doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0447-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hansen C, Gilron I, Hong M: The effects of intrathecal gabapentin on spinal morphine tolerance in the rat tail-flick and paw pressure tests. Anesth Analg 2004; 99: 1180–4, table of contents [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lin JA, Lee MS, Wu CT, Yeh CC, Lin SL, Wen ZH, Wong CS: Attenuation of morphine tolerance by intrathecal gabapentin is associated with suppression of morphine-evoked excitatory amino acid release in the rat spinal cord. Brain Res 2005; 1054: 167–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van Elstraete AC, Sitbon P, Mazoit JX, Benhamou D: Gabapentin prevents delayed and long-lasting hyperalgesia induced by fentanyl in rats. Anesthesiology 2008; 108: 484–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eckhardt K, Ammon S, Hofmann U, Riebe A, Gugeler N, Mikus G: Gabapentin enhances the analgesic effect of morphine in healthy volunteers. Anesth Analg 2000; 91: 185–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yucel A, Ozturk E, Aydogan MS, Durmus M, Colak C, Ersoy MO: Effects of 2 different doses of pregabalin on morphine consumption and pain after abdominal hysterectomy: a randomized, double-blind clinical trial. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp 2011; 72: 173–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rock DM, Kelly KM, Macdonald RL: Gabapentin actions on ligand- and voltage-gated responses in cultured rodent neurons. Epilepsy Res 1993; 16: 89–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schumacher TB, Beck H, Steinhauser C, Schramm J, Elger CE: Effects of phenytoin, carbamazepine, and gabapentin on calcium channels in hippocampal granule cells from patients with temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia 1998; 39: 355–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hoppa MB, Lana B, Margas W, Dolphin AC, Ryan TA: alpha2delta expression sets presynaptic calcium channel abundance and release probability. Nature 2012; 486: 122–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cassidy JS, Ferron L, Kadurin I, Pratt WS, Dolphin AC: Functional exofacially tagged N-type calcium channels elucidate the interaction with auxiliary alpha2delta-1 subunits. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014; 111: 8979–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]