Abstract

Cell wall glycopolymers on the surface of Gram-positive bacteria are fundamental to bacterial physiology and infection biology. Here we identify gacH, a gene in the S. pyogenes Group A Carbohydrate (GAC) biosynthetic cluster, in two independent transposon library screens for its ability to confer resistance to zinc and susceptibility to the bactericidal enzyme human group IIA secreted phospholipase A2. Subsequent structural and phylogenetic analysis of the GacH extracellular domain revealed that GacH represents a new class of glycerol phosphate (GroP) transferase. We detected the presence of GroP in the GAC as well as the Serotype c Carbohydrate (SCC) from S. mutans, which depended on the presence of the respective gacH homologs. Finally, NMR analysis of GAC confirmed that GroP is attached to approximately 30% of the GAC N-acetylglucosamine side-chains at the C6 hydroxyl group. This previously unrecognized structural modification impacts host-pathogen interaction and has implications for vaccine design.

Gram-positive bacteria are surrounded by a thick cell wall consisting of a complex network of peptidoglycan with covalently attached glycopolymers that comprise a large family of structurally diverse molecules, including wall teichoic acid, mycobacterial arabinogalactans and capsular polysaccharides. From these, wall teichoic acid is perhaps the most widespread and the best-studied molecule. This polyanionic, phosphate-rich glycopolymer is critical for functions such as cell division, antibiotic resistance, metal ion homeostasis, phage-mediated horizontal gene transfer and protection of bacteria from host defense peptides and antimicrobial enzymes 1,2. As such, these structures and their biosynthetic pathways are attractive targets for antibiotic development and vaccine design. Interestingly, many streptococci lack classical wall teichoic acid and instead express glycopolymers that are characterized by the presence of l-rhamnose (Rha) 3. These structures comprise about 40–60% of the bacterial cell wall mass, and are historically used for serological grouping of streptococci 3. The glycopolymers of two human streptococcal pathogens, Streptococcus pyogenes or Group A Streptococcus (GAS) and Streptococcus mutans, are respectively referred to as the Lancefield group A Carbohydrate (GAC) and Serotype c Carbohydrate (SCC). These glycopolymers share a characteristic [→3)α-Rha(1→2)α-Rha(1→] polyrhamnose backbone, but are serologically distinguished based on their specific glycosyl side-chain residues, i.e. N-acetyl-β-d-glucosamine (GlcNAc) in GAC 4 and α-glucose (Glc) in SCC 5. GAC and SCC play significant roles in cell morphology and division 6, resistance to certain cell wall targeting antibiotics 7, biofilm formation 8 and pathogenesis of GAS and S. mutans 9–11. Importantly for both pathogens, GAC and SCC have been evaluated as vaccine antigens. Immunization with GAC or SCC induces opsonophagocytic antibodies that enhance killing of GAS and S. mutans, respectively 5,12,13. In addition, GAC has proven efficacious as a vaccine antigen through active immunization in mice 12,13.

The GAC and SCC biosynthetic pathways are encoded by 12-gene clusters 3,11, herein designated as gacABCDEFGHIJKL and sccABCDEFGHMNPQ (Fig. 1a), respectively. The first seven genes in both gene clusters are conserved in many streptococcal species and they participate in polyrhamnose backbone synthesis and transport 14. In GAS, gacI, gacJ, gacK and gacL encode the machinery to generate and add the GlcNAc side-chain to the polyrhamnose backbone 11,15, whereas the genes required for Glc side chain generation are not clearly identified in S. mutans. In addition to these streptococcal species, similar gene clusters are present in a wide variety of streptococcal, lactococcal and enterococcal species 3.

Fig. 1. GacH homologues are required for hGIIA bactericidal activity against GAS and S. mutans.

a, Schematic representation of GAC and SCC biosynthetic gene clusters. SCC biosynthesis encoding gene cluster smu.824–835 was renamed sccABCDEFGHMNPQ. Sequence identity (%) between encoded homologous proteins is indicated. Sequences of GAS 5005 and S. mutans UA159 were used for identity comparison. b–d, Identification of gacH in Tn-seq screen and validation for hGIIA resistance. b, Transposon gene locus tags of the 47 hGIIA-resistant mutants after exposure of Krmit mutant transposon library to lethal concentrations of hGIIA. Susceptibility of GAS 5448 and S. mutans to hGIIA concentration range upon (c) deletion of gacH in GAS 5448 and (d) the gacH-homologous gene sccH, respectively. Symbols and error bars represent the mean and s.d., respectively (n=3 biologically independent replicates and each replicate represents three technical replicates). P values were calculated by 2-way ANOVA. Bonferroni multiple comparison test was used to statistically compare multiple groups. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. The precise P values are listed in Supplementary Table 2.

In addition to the polyrhamnose biosynthesis genes, the GAC and SCC biosynthetic clusters contain another conserved gene of unknown function, gacH and sccH, respectively, which is annotated as a putative glycerol phosphate (GroP) transferase. Recently, we employed the Krmit GAS transposon mutant library 16 and identified gacI and gacH as genes that confer sensitivity of bacteria to human group IIA secreted phospholipase A2 (hGIIA) 17, an important bactericidal protein of the innate immune system against Gram-positive pathogens 18. Complementary to that study, we now identified gacH as the only valid hit when the Krmit library was exposed to a lethal concentration of hGIIA. Interestingly, gacH was also identified as a gene providing resistance to zinc toxicity, which is a mechanism deployed by neutrophils to kill GAS 19. In pursuit of the underlying mechanism, we have characterized the function of GacH at the genetic, biochemical and structural level. Our study identifies a previously overlooked GroP modification on both GAC and SCC, and pinpoints GacH homologues as the enzymes responsible for the respective GroP modifications.

Results

GacH and SccH confer sensitivity to hGIIA.

We previously identified gacH in a GAS Tn-seq transposon library screen as a potential hGIIA susceptibility gene 17. To identify additional resistant mutants, we exposed the Krmit GAS transposon library 16 to a lethal concentration of hGIIA. PCR sequencing identified that 43% of the recovered mutants had a transposon insertion in gacH, and 26% in M5005_Spy_1390 (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Table 1). M5005_Spy_1390 was identified in the initial susceptibility screen as an artifact due to biased transposon insertions 17 and not investigated further. To validate our finding for gacH, we generated a gacH deletion mutant in a GAS serotype M1T1 clone 5448, creating 5448ΔgacH. Deletion of gacH rendered GAS resistant to hGIIA over the tested concentration range and was reversed by complementation with gacH on an expression plasmid (5448ΔgacH:pgacH, Fig. 1c). The gacH-dependent hGIIA resistance was also observed in two different GAS backgrounds, 2221 (M1T1 clone strain) and 5005 (clinical covS mutant isolate of M1T1 strain) (Supplementary Fig. 1a and b), demonstrating that the effect is conserved across GAS strains of the M1T1 background and independent of CovRS status – a two-component system which regulates about 15% of the genes in this bacterium 20.

To investigate whether hGIIA susceptibility was also influenced by gacH homologues in other streptococci, we deleted the gacH homologue sccH in S. mutans (SMU) serotype c strain Xc, creating SMUΔsccH. SMUΔsccH was completely resistant to the tested hGIIA concentrations (Fig. 1d) and susceptibility was restored to WT levels by plasmid-expressed sccH. However, heterologous expression of gacH in SMUΔsccH did not restore the phenotype (Supplementary Fig. 1c), suggesting that the enzymes might target different substrates. Altogether, our data indicate that deletion of gacH homologues renders streptococci more resistant to hGIIA bactericidal activity and that GacH function is species-specific.

GacH and SccH provide protection from zinc toxicity.

Recent evidence indicates that neutrophils deploy zinc poisoning as an antimicrobial strategy against GAS during phagocytosis 19. To resist Zn2+ toxicity, GAS expresses a zinc efflux system encoded by czcD 19. To search for additional Zn2+-resistance genes, we performed a Tn-seq screen of the GAS Krmit transposon library 16 using two Zn2+ concentrations, 10 and 20 μM, selected based on growth inhibition analysis (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Genomic DNA for Tn-seq analysis was collected after T2 and T3 passages (Supplementary Fig. 2b). In addition to the expected importance of czcD, gacI and gacH transposon insertions were significantly reduced in the library (p <0.05) after growth with 20 μM Zn2+ in both T2 and T3 passages compared to untreated controls, indicating that these genes provide resistance against Zn2+ toxicity (Fig. 2a-d).

Fig. 2. Deletion of gacI and gacH renders GAS susceptible to Zn2+.

a–d, Tn-seq volcano plots showing representation of czcD, gacH and gacI in GAS Krmit transposon library screens for Zn2+ tolerance. Log2 fold-change (log2 FC) in fitness was plotted against adjusted p-value from Tn-seq analyses through an established pipeline using EdgeR and DEseq2 (n= 4 biologically independent replicates were used for analysis) 51–53. The outline of the experiment is shown in Supplementary Fig. 2b. Tn-seq screens of the transposon library were conducted using (a) 10 μM Zn2+ at T2, (b) 10 μM Zn2+ at T3, (c) 20 μM Zn2+ at T2, (d) 20 μM Zn2+ at T3. e,f, Zn2+ sensitivity as tested in drop test assay using strains (e) 5448 WT, 5448ΔgacH and 5448ΔgacH:pgacH; and (f) 5448 WT, 5448ΔgacI and 5448ΔgacI:gacI. 5448ΔczcD was included as a positive control in both panels. Each drop test assay experiment was performed independently at least three times and yielded the same results.

To validate our findings, we grew 5448ΔgacH and 5448ΔgacI 11 on solid rich medium supplied with different Zn2+ concentrations (Fig. 2e and f). Both mutants showed reduced growth in the medium supplied with 1.25 mM Zn2+, which was restored upon complementation with the respective genes (Fig. 2e and f). Again, we checked for function conservation by extending our experiments to S. mutans. Indeed, SMUΔsccH was more sensitive to Zn2+, in comparison to the parental strain and the phenotype could only be restored by sccH but not gacH (Supplementary Fig. 3). Hence, our results provide strong evidence that GacH and SccH are important to protect streptococci from Zn2+ toxicity.

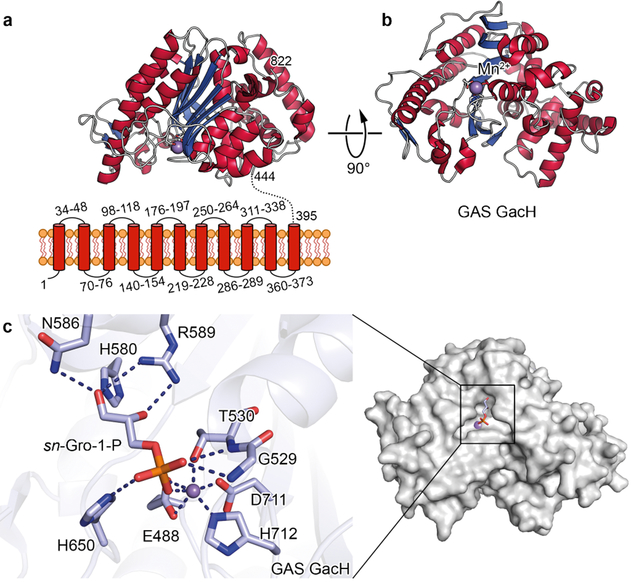

Crystal structure reveals that GacH is a GroP transferase.

GacH is predicted to contain eleven N-terminal transmembrane segments and an extracellular C-terminal catalytic domain (eGacH). To test the hypothesis that GacH is a GroP transferase, eGacH was expressed and purified from E. coli. Its crystal structure was determined in apo form (PDB ID 5U9Z) at 2.0 Å resolution (Fig. 3a and b) and in complex with GroP (PDB ID 6DGM) at 1.49 Å resolution (Fig. 3c). The apo- and GroP-containing eGacH structures belong to different crystal forms, with two molecules in the asymmetric unit. Analysis of the dimer interface and other crystal contacts revealed that the dimer interface has the largest surface of all the crystal contacts (1809 and 1894 Å2 in the two crystal forms). However, it is scored below the stable complex formation criteria, and recombinant eGacH behaves as a monomer in solution. The structures of the apo- and GroP-bound eGacH monomers are very similar with root mean square deviation of 0.3 Å for 380 superimposed Cα atoms, as well as between the non-crystallographic copies.

Fig. 3. Structure of eGacH.

a, Predicted topology of GacH showing eleven transmembrane helices and structure of extracellular domain with the enzymatic active site oriented towards the cell membrane. b, Structure of apo eGacH viewing at the active site with the Mn2+ ion shown as a violet sphere. c, A close-up view of the active site GacH crystal structure in complex with sn-Gro-1-P.

eGacH has an α/β core structure that is characteristic for the sulfatase protein family, with the closest similarity to lipoteichoic acid (LTA) synthase LtaS 21,22 (Supplementary Fig. 4a,b and 5) and LTA primase LtaP 23 (Supplementary Table 3). LtaS and LtaP are GroP transferases that participate in biosynthesis of LTA, a crucial constituent of Gram-positive cell envelopes, consisting of a poly(GroP) backbone linked to a glycolipid membrane anchor 24. The catalytic site of eGacH contained a Mn2+ ion coordinated by residues E488, T530, D711 and H712, equivalent to residues E255, T300, D475 and H476 of a C-terminal extracellular domain of LtaS (eLtaS) from Staphylococcus aureus (Fig. 3c, Supplementary Fig. 4c,d and 5). The structure of eGacH in complex with GroP revealed the position of the ligand in the active site with the phosphoryl group oriented towards the Mn2+ ion, and coordinated by residues G529, T530 and H650 (Fig. 3c). The glycerol 2- and 3-hydroxyl groups form hydrogen bonds with side-chains of residues R589, H580 and N586. The positions of GroP and coordinating residues are similar in eGacH and S. aureus eLtaS structures. For example, the glycerol moiety forms hydrogen bonds with residues H580 and R589 in GacH and equivalent residues H347 and R356 in S. aureus eLtaS (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 4c,d) 21. Thus, the structure of eGacH in complex with GroP is consistent with the idea that GacH and LtaS use related catalytic mechanisms to transfer GroP to substrates.

To functionally assess the requirement of the catalytic residues, we examined the bactericidal activity of hGIIA in 5448ΔgacH and SMUΔsccH expressing catalytically inactive versions of gacH and sccH, in which the active site T530 and T533 codons were replaced by alanine, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 6). The non-functional gacH and sccH did not restore hGIIA susceptibility (Fig. 1c and d), indicating that the GroP transferase activity of the gacH and sccH gene products is required for the observed hGIIA-dependent phenotypes.

GacH cleaves phosphatidylglycerol to release GroP.

Experimental evidence suggests that LtaS utilizes the GroP head group of the membrane lipid phosphatidylglycerol as donor for poly(GroP) backbone biosynthesis, liberating diacylglycerol 24,25. To assess whether GacH also catalyzes the cleavage of phosphatidylglycerol to yield GroP for a transfer reaction, we performed an in vitro experiment employing the eGacH protein and a fluorescently-labelled artificial substrate, NBD-phosphatidylglycerol. Incubation of eGacH with NBD-phosphatidylglycerol yielded a fluorescent product (Supplementary Fig. 7a), with the same mobility on silica gel TLC as NBD-diacylglycerol, which was obtained from NBD-phosphatidylglycerol by enzymatic cleavage with phospholipase C from Bacillus cereus. Furthermore, the eGacH product recovered from the silica gel plate and analyzed by LC-MS, yielded a spectrum consistent with NBD-diacylglycerol and identical to the spectrum of the phospholipase C product (Supplementary Fig. 7b–d). The formation of NBD-diacylglycerol by eGacH required the active-site residues, since the eGacH variant, eGacH-T530A, was not active in the assay (Supplementary Fig. 7a). These observations are consistent with the assignment of GacH as a GroP transferase.

GacH homologues decorate glycopolymers with GroP.

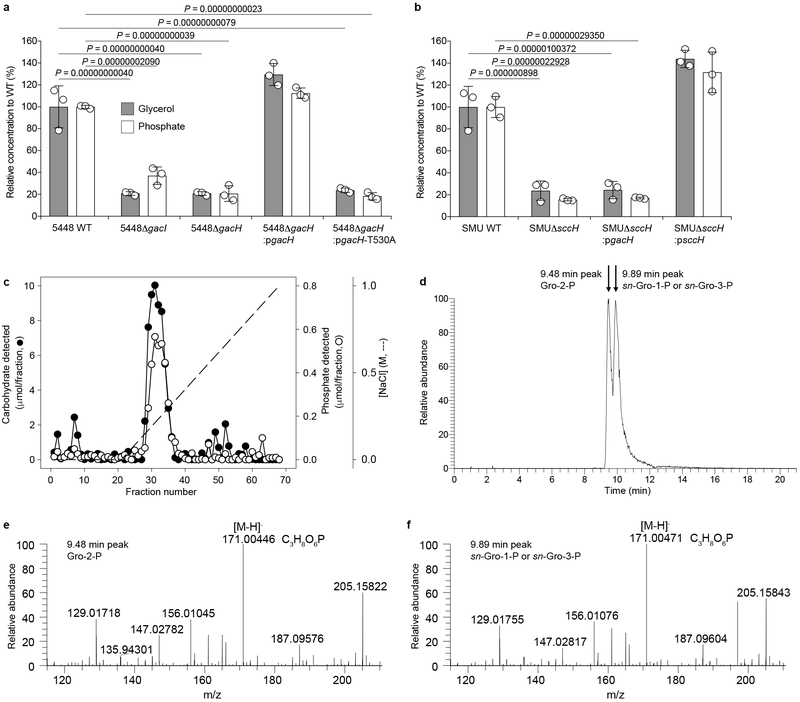

Phylogenetic analysis of either the full length or extracellular domains of GacH homologues and LtaS-related proteins revealed that these proteins fall into distinct clades of GroP transferases, suggesting that the proteins may transfer GroP to different substrates (Supplementary Fig. 8). To assess whether gacH homologues modify the respective streptococcal glycopolymers with GroP, we enzymatically released GAC and SCC from purified cell walls from GAS and S. mutans strains. Subsequently, the enriched polysaccharide preparations were analyzed for glycerol and phosphate. Hydrolysis with HCl released a significant amount of glycerol from GAC and SCC isolated from WT bacteria (Fig. 4a,b, and Supplementary Fig. 9a). Furthermore, we detected high levels of inorganic phosphate after incubating these acid-treated samples with alkaline phosphatase (Fig. 4a,b and Supplementary Fig. 9a), which was not detected when intact GAC was treated with alkaline phosphatase (Supplementary Fig. 9b,c). This indicates that the phosphoryl moiety is present as a phosphodiester, consistent with its identification as GroP. Conclusive evidence that the glycerol and phosphate detected in this analysis is, in fact, GroP is presented below. In contrast to WT GAC and SCC, the glycopolymers isolated from 5448ΔgacH, 5005ΔgacH and SMUΔsccH contained a significantly reduced amount of glycerol and phosphate (Fig. 4a,b and Supplementary Fig. 9a), which was only restored by complementation with WT gacH, but not gacH-T530A, for GAS (Fig. 4a) or plasmid-expressed sccH for SMU (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4. GacH and SccH modify their respective glycopolymers with sn-Gro-1-P.

a,b, Analysis of glycerol and phosphate content in GAC and SCC isolated from (a) GAS 5448 WT, ΔgacI, ΔgacH and ΔgacH complemented with native gacH or a catalytically-inactivated version of gacH (gacH-T530A), and (b) S. mutans WT, ΔsccH, and ΔsccH complemented with sccH or gacH. The concentration of phosphate and glycerol is presented relative to the WT strain. Bars and error bars represent the average and s.d., respectively (n=3 biologically independent samples). P-values were calculated and adjusted by 2-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test. c, DEAE-Sephacel elution profile of GAC isolated from ∼90 mg of GAS cell wall. Fractions were analyzed for carbohydrate (●) and phosphate (O). d–f, Identification of the enantiomeric form of GroP associated with GAC. d, The GroP isomers were recovered from GAC following alkaline hydrolysis and separated by liquid chromatography as outlined in Methods. The elution positions corresponding to standard Gro-2-P and sn-Gro-1-P/sn-Gro-3-P are indicated by the arrows. LC-MS analysis identifies two extracted ion chromatogram peaks for the molecular GroP ion m/z 171.004 [M-H]-, which eluted at (e) 9.48 and (f) 9.89 min. Based on the accurate mass and retention times, these two peaks were assigned as Gro-2-P and sn-Gro-1-P/sn-Gro-3-P respectively by comparison with authentic chemical standards. Experiments depicted in c–f were performed independently twice and yielded the same results.

In accordance with our functional data, expression of gacH did not restore the glycerol and phosphate levels in SCC of SMUΔsccH (Fig. 4b). This suggested that GroP modifications might involve the species-specific side-chains (Glc vs. GlcNAc), rather than the identical polyrhamnose backbone. Indeed, the glycerol and phosphate contents in GAC isolated from the GlcNAc-deficient mutant, 5448ΔgacI, were significantly reduced (Fig. 4a). Importantly, analysis of GAS strains for total carbohydrate, phospholipid and phosphatidylglycerol contents established that deletion of gacH had no effect on these components (Supplementary Fig. 10a–c). Furthermore, the semi-quantitative immuno-dot blot analysis of GAS strains with anti-GAC antibodies demonstrated that the absolute amount of GAC is not affected by gacH deletion (Supplementary Fig. 10d). Analysis of the glycosyl composition of purified cell walls demonstrated that the absence of GacH and SccH did not affect the Rha/GlcNAc and Rha/Glc ratios, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 10e,f).

To provide further evidence that GAC is modified with GroP, GAC samples were subjected to alkaline hydrolysis to release GroP, as described by Kennedy et al 26 and the hydrolysate was analyzed by LC-MS for high molecular weight fragment ions arising from GroP. Compared to WT, deletion of either gacH or gacI reduced the levels of GroP in GAC significantly (Supplementary Fig. 11). Complementation of 5448ΔgacH with native gacH, but not with inactive gacH-T530A, fully restored GroP levels (Supplementary Fig. 11). Thus, the differences in GroP content for the gacH and gacI deletion mutants are consistent with a role for GacH in modification of GlcNAc side-chain of GAC with GroP.

To show that GroP is attached directly to GAC, the WT GAC was further purified by a combination of size exclusion and ion-exchange chromatography (Fig. 4c, Supplementary Fig. 12a). The majority of the rhamnose- and phosphate-containing material was bound to the ion-exchange column and eluted as a single coincident peak (Fig. 4c). The GAC purified from 5005ΔgacH did not bind to the column (Supplementary Fig. 12b). Interestingly, the 5005ΔgacH GAC does appear to contain a small amount of phosphate that may arise from the phosphodiester bond linking GAC to peptidoglycan. Taken together, our data directly support the conclusion that GAC is modified with GroP donated by GacH.

GacH decorates GAC with sn-Gro-1-P.

To assess which GroP enantiomer was incorporated in GAC, GroP liberated from purified GAC by alkaline hydrolysis was analyzed further (Supplementary Fig. 13). As described in detail by Kennedy et al 26, if GAC is modified by sn-Gro-1-P, alkaline hydrolysis of the phosphodiester bond should result in the formation of a mixture of sn-Gro-1-P and Gro-2-P, whereas modification by sn-Gro-3-P would yield a mixture of sn-Gro-3-P and Gro-2-P 26. As expected, LC-MS analysis of GAC-derived GroP revealed the presence of two GroP isomers of approximately equal proportions with LC retention times and major high molecular weight ions consistent with standard sn-Gro-1-P/sn-Gro-3-P and Gro-2-P (Fig. 4d–f, Supplementary Fig. 14). The recovered GroP was characterized further by enzymatic analysis using an sn-Gro-3-P assay kit. Under reaction conditions in which sn-Gro-3-P standard produced a robust enzymatic signal, incubation with an equal amount of either sn-Gro-1-P or the unknown Gro-P resulted in negligible activity (Supplementary Fig. 15). When the sn-Gro-3-P was mixed with an equal amount of either sn-Gro-1-P or the unknown mixture of GroP isomers, 85.8% and 90.0% of the activity detected with the standard sn-Gro-3-P alone was found, confirming that the negative result using the unknown mixture was not due to the presence of an inhibitory compound in the GroP preparation. Taken together, our results indicate that GacH decorates GAC with sn-Gro-1-P, which is most probably derived from phosphatidylglycerol.

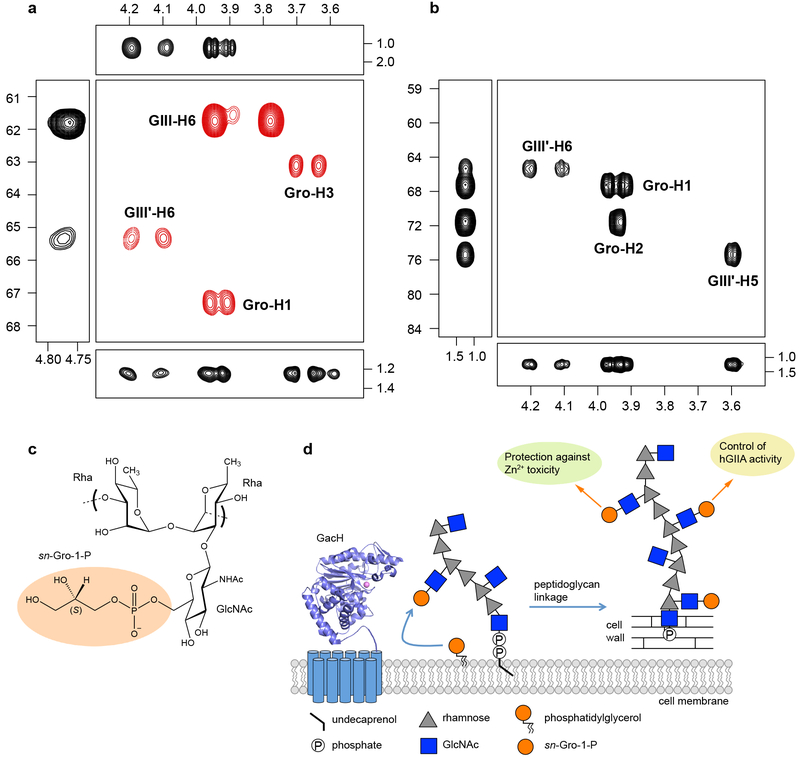

GroP is attached to the C6 hydroxyl group of GlcNAc.

To unambiguously establish the presence and location of GroP in GAC, the glycopolymer was isolated from WT GAS and analyzed by NMR (Fig. 5 a, Supplementary Table 4, Supplementary Fig. 16 and 17). The details of NMR analysis are described in Supplementary Notes. WT GAC is partially substituted by a GroP residue at O6 of the side-chain β-d-GlcpNAc residue; based on integration of the cross-peaks for the anomeric resonances in the 1H,13C-HSQC NMR spectrum, the GAC preparation carries GroP groups to ∼30 % of the GlcNAc residues. To validate the 2D NMR results, a triple-resonance 1H,13C,31P NMR experiment based on through-bond 1JHC as well as 2JCP and 3JCP correlations 27 was carried out. The 3D NMR experiments revealed the 1H NMR chemical shifts of H5' and the two H6' protons of the β-d-GlcpNAc residue, as well as the two H1 protons and H2 of the Gro residue that all correlated to 13C nuclei (Fig. 5b). The 13C NMR chemical shifts of C5' and C6' of the β-d-GlcpNAc residue as well as C1' and C2' of the Gro residue all correlated to the 31P nucleus (Fig. 5b), and the above protons correlated to the 31P nucleus (Fig. 5b). Taking into considerations the GacH-mediated mechanism of GAC modification by GroP as well as the biochemical experiments carried out herein, the substituent at O6 of β-d-GlcpNAc is an sn-Gro-1-P group (Fig. 5c).

Fig. 5. NMR analysis confirms presence of GroP on C6 GlcNAc hydroxymethyl group of GAC.

a–b, Selected regions of NMR spectra of GAC. a, Multiplicity-edited 1H,13C-HSQC in which methylene groups have opposite phase and are shown in red color (center box), 1H,13C-HSQC-TOCSY with an isotropic mixing time of 120 ms (left box), 1H,13C-HMBC with a mixing time of 90 ms (top box), 1H,31P-hetero-TOCSY with an isotropic mixing time of 80 ms (bottom box). b, 1H,13C-plane (center box), 13C, 31P-plane using a nominal nJCP value of 5 Hz (left box), and 1H, 31P-plane (bottom box) of a through-bond 3D 1H,13C,13P NMR experiment. Cross-peaks are annotated as GIII corresponding to the GlcNAc residue, GIII' being the GroP-substituted GlcNAc residue and Gro as the glycerol residue. NMR chemical shifts of 1H (horizontal axis), 13C (left axis) and 31P (right axis and left box in b) are given in ppm. Experiments depicted in a–b were performed independently three times and yielded the same results. c, Schematic structure of the GAC repeating unit consisting of →3)-α-l-Rhap-(1→2)[β-d-GlcpNAc6P(S)Gro-(1→3)]-α-l-Rhap-(1→. d, The mechanism and the roles of GroP cell wall modification in streptococci.

Discussion

In Gram-positive bacteria, many peptidoglycan-attached glycopolymers contain negatively-charged groups in the repeating units 2. Previous detailed studies deduced chemical structures of glycopolymers from GAS and S. mutans 3–5. However, none identified anionic groups in these structures, except for one study that reported the presence of glycerol and phosphate in GAC 28 and proposed that this GroP is part of the phosphodiester linkage connecting GAC to peptidoglycan 28. Similarly, other reports identified substantial concentrations of phosphate in the glycopolymers isolated from a number of streptococcal species 29–31. Phosphate detection was either disregarded as contamination with LTA 29, or further analyzed using 1H NMR or 13C NMR methods 5,31,32 that do not directly detect phosphoryl moieties in polysaccharides. With our report, we unambiguously confirm that the glycopolymers of GAS and S. mutans are in fact polyanionic molecules through decoration of their respective glycan side-chains with GroP (Fig. 5c,d).

We identified and structurally characterized a new class of GroP transferase enzymes, represented by GacH, which modifies GAC with GroP in the human pathogen GAS. According to our phylogenetic analysis, GacH homologues are present in many streptococci (Supplementary Fig. 8), suggesting that these bacteria express glycopolymers with GroP-modified side chains, as we have demonstrated here for S. mutans. GacH belongs to the alkaline phosphatase superfamily of which two GroP transferases involved in LTA synthesis, LtaS and LtaP, have been biochemically and structurally characterized 21–23,33. LtaS and LtaP are membrane proteins that use the membrane lipid phosphatidylglycerol as the GroP donor for the transfer reaction 25. Our structural analysis of GacH in complex with GroP indicates that the T530 residue participates in the formation of a GroP-enzyme intermediate similar to observations in LtaS, where the GroP molecule is complexed in the active site threonine residue which functions as a nucleophile in phosphatidylglycerol hydrolysis 21–23. The importance of this residue was also confirmed functionally, since complementation of gacH mutant strains with a T530A gacH variant could not restore GroP content in GAC and hGIIA sensitivity to WT levels. The observations that the extracellular domain of GacH cleaves phosphatidylglycerol and the GroP in GAC is the sn-Gro-1-P enantiomer, strongly suggest that GacH uses phosphatidylglycerol as its donor substrate for the transfer reaction, similar to LtaS (Fig. 5d).

In Gram-positive bacteria, the modification of teichoic acids with d-alanine provides resistance against antibiotics, cationic antimicrobial peptides and small bactericidal enzymes including hGIIA, and affects Mg2+ ion scavenging 1,2,34. It has been assumed that incorporation of positively charged d-alanine into teichoic acids decreases negative bacterial surface charge resulting in reduced initial binding of cationic antimicrobial peptides to the bacterial surface due to ionic repulsion 35,36. Our study demonstrates that addition of the negatively-charged GroP group to glycopolymers protects streptococci from zinc toxicity but also renders bacteria more sensitive to hGIIA activity.

A large body of evidence indicates that phagocytic cells utilize Zn2+ intoxication to suppress the intracellular survival of bacteria 37. Zinc is essential as a key catalytic or structural element for a wide variety of proteins and its concentration needs to be maintained at a specific level, which requires sophisticated systems for uptake and efflux of metal ions. Hence, elevated levels of zinc in the cytosol result in cellular toxicity 19, which for GAS is due to inhibition of central carbon metabolism 38. One mechanism of microbial susceptibility to zinc toxicity is mediated by extracellular competition of Zn2+ for Mn2+ transport and thereby mediating toxicity by impairing acquisition of Mn2+, the essential nutrient metal 39. Accordingly, the phenotypes of our GroP and GlcNAc-side chain deficient mutants could be explained either by “trapping” of Zn2+ in the WT cell wall by GroP, or the increased Mn2+-binding capacity of GroP-modified bacterial cell wall which has been proposed to act as the conduit for the trafficking of mono- and divalent cations to the membrane 34.

Charge-dependent mechanisms are likely underlying the increased hGIIA susceptibility of GAS and S. mutans expressing GroP-modified glycopolymers. hGIIA is a highly cationic enzyme that catalyzes the hydrolysis of bacterial phosphatidylglycerol 40,41, ultimately leading to bacterial death through lysis. Traversal of this bactericidal enzyme through the Gram-positive cell wall to the plasma membrane is charge-dependent. Indeed, the absence of d-alanine modifications in teichoic acids severely compromises S. aureus survival when challenged with hGIIA 41,42. Similarly, the GacH/SccH-dependent GroP modifications on glycopolymers are required for hGIIA to exert its bactericidal effect against GAS and S. mutans, respectively. We have previously demonstrated that loss of the entire GlcNAc GAC side-chain strongly hampers hGIIA trafficking through the GAS cell wall, with a minor contribution of reduced hGIIA binding to the cell surface 17. Since GroP-modifications were also lost in the GlcNAc side-chain deficient mutant, 5448ΔgacI, described in this study, we now assume that the mechanisms of the hGIIA-dependent phenotype are similar in the gacI and gacH mutants.

Another very important aspect of our study is the identification of a novel, potentially antigenic, epitope on the surface of streptococci. GAS is associated with numerous mild to life-threatening invasive diseases 43 and is also causative of post-infectious sequelae, including rheumatic heart disease 43. Especially the invasive manifestations and post-infectious sequelae are difficult to treat with antibiotics and a GAS vaccine is urgently needed to combat these neglected diseases. The GAC is an attractive candidate for GAS vaccine development due to its conserved expression in all GAS serotypes and the absence of the constitutive component of GAC, Rha, in humans 12,13. However, it has been proposed that the GAC GlcNAc side-chain may elicit cross-reactive antibodies relevant to the pathogenesis of rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease 44–46. Moreover, persistence of anti-GAC and anti-GlcNAc antibodies is associated with a poor prognosis in rheumatic heart disease 45. These clinical associations and the lack of understanding of the pathogenesis of GAS post-infectious rheumatic heart disease have hampered progress in the development of GAC-based vaccines against GAS. However, the GAC GlcNAc decorated with GroP might be an attractive candidate for GAS vaccine development because GroP-modified GlcNAc represents a unique epitope, that is absent from human tissues. Thus, our study has implications for design of a safe and effective vaccine against this important human pathogen for which a vaccine is currently lacking.

Methods

Bacterial strains, growth conditions and media.

All plasmids, strains and primers used in this study are listed in Supplementary Tables 5 and 6. GAS and S. mutans strains were grown in Todd-Hewitt broth supplemented with 1% yeast extract (THY) without aeration at 37°C. S. mutans plates were grown with 5% CO2. For hGIIA-mediated killing experiments, S. mutans strains were grown in Todd-Hewitt broth without yeast extract and with 5% CO2. E. coli strains were grown in Lysogeny Broth (LB) medium or on LB agar plates at 37°C. When required, antibiotics were included at the following concentrations: ampicillin at 100 μg/mL for E. coli; streptomycin at 100 μg/mL for E. coli; erythromycin (Erm) at 500 μg/mL for E. coli, 5 μg/mL for GAS and 10 μg/mL for S. mutans; chloramphenicol (CAT) at 10 μg/mL for E. coli, 2 μg/mL for GAS and S. mutans; spectinomycin at 200 μg/mL for E. coli, 100 μg/mL for GAS and 500 μg/mL for S. mutans; kanamycin at 300 μg/mL for GAS.

To identify gene providing resistance against Zn2+ toxicity, RPMI 1640 (without glucose) (Gibco) was supplemented with guanine, adenine and uracil at a concentration of 25 μg/mL each, d-glucose at a concentration of 0.5% w/v and HEPES at 50 mM. Vitamins were provided by 100X BME Vitamins (Sigma B6891).

Genetic manipulations.

Plasmids were transformed into GAS and S. mutans by electroporation or natural transformation as described previously 6. All constructs and mutants were confirmed by PCR and sequencing analysis (Eurofins MWG Operon and Macrogen).

Genetic manipulation of GAS. To construct 5005ΔgacH and 2221ΔgacH, 5005 chromosomal DNA was used as a template for amplification of two DNA fragments using primers pairs 5005-f/gacHdel-r and gacHdel-f/5005-r, which were fused and amplified using a PCR overlap method 47 with primer pair 5005-f/5005-r to create the deletion of gacH. The PCR product was digested with BamHI and XhoI and ligated into BamHI/SalI-digested plasmid pBBL740, transformed into 5005 and 2221, and CAT resistant colonies were selected on THY agar plates. Several potential double crossover mutants were selected as previously described 48.

To construct the plasmid for in cis complementation of 5005ΔgacH, 5005 chromosomal DNA was used as a template for amplification of gacH using the primer pair 5005-f/5005-r, which was cloned in pBBL740 through restriction-ligation using BamHI and XhoI. The plasmid was transformed into the 5005ΔgacH strain, and CAT resistant colonies were selected on THY agar plates. Double crossover mutants were selected as described above.

To construct 5448ΔgacH, GAS 5448 chromosomal DNA was used to amplify up and downstream regions flanking gacH using primer pairs: 5448-f/5448CAT-r and 5448CAT-f/5448-r. Primers 5448CAT-f and 5448CAT-r contain 25 bp extensions complementary to the CAT resistance cassette. Up- and downstream were fused to the CAT cassette using 5448-f/5448-r, and cloned into pHY304 through digestion-ligation using XhoI and HindIII, yielding plasmid pHY304ΔgacH. After the plasmid transformation into 5448, double crossover mutant, 5448ΔgacH, was selected as previously described 15.

To complement 5448ΔgacH, gacH was amplified from 5448 chromosomal DNA using primer pair gacH-EcoRI-f/gacH-BglII-r, digested using EcoRI/BglII, and ligated into EcoRI/BglII-digested pDCerm, yielding pgacH_erm. To make a catalytically inactive variant of gacH, the mutation T550A was introduced into pgacH_erm using Gibson Assembly site-directed mutagenesis with the primers gacH-T530A-F, gacH-T530A-R, repB-isoF and repB-isoR. The plasmids were transformed into 5448ΔgacH and selected for Erm resistance on THY agar plates. Transformation was confirmed by PCR, yielding strains 5448ΔgacH:pgacH and 5448ΔgacH:pgacH-T530A, respectively.

To construct SMUΔsccH, S. mutans Xc chromosomal DNA was used to amplify up and downstream regions flanking using primer pairs: sccH-f/sccH-erm-r and sccH-erm-f /sccH-r. Primers sccH-erm-f and sccH-erm-r contained 25 bp extensions complementary to the Erm resistance cassette. Up and downstream PCR fragments were mixed with the Erm cassette and amplified as a single PCR fragment using primer pair sccH-f/sccH-r. The sccH knockout construct was transformed into S. mutans as described previously 6. Erm resistant single colonies were picked and checked for deletion of sccH and integration of Erm cassette by PCR, resulting in SMUΔsccH. For complementation, sccH and gacH were amplified from S. mutans Xc and GAS 5448 chromosomal DNA, respectively, using primer pairs sccH-EcoRI-f/sccH-BglII-r and gacH-EcoRI-f/gacH-BglII-r. The PCR products were digested with EcoRI/BglII, and ligated into EcoRI/BglII-digested pDC123 vector, yielding psccH and pgacH_cm, respectively. To make a catalytically inactive variant of sccH, the mutation T553A was introduced into psccH using Gibson Assembly site-directed mutagenesis with the primers sccH-T553A-F, sccH-T553-R, repB-isoF and repB-isoR. The plasmids were transformed into SMUΔsccH as described 6. CAT resistant single colonies were picked and checked for presence of psccH or pgacH_cm by PCR, yielding strains SMUΔsccH:psccH, SMUΔsccH:psccH-T533A and SMUΔsccH:pgacH, respectively.

To create a vector for expression of eGacH in E. coli, the gene was amplified from 5005 chromosomal DNA using the primers gacH-NcoI-f and gacH-XhoI-r. The PCR product was digested with NcoI and XhoI, and ligated into NcoI/XhoI-digested pCDF-NT vector. The resultant plasmid, pCDF-GacH, contained gacH fused at the N-terminus with a His-tag followed by a TEV protease recognition site. To produce a catalytically inactive variant of eGacH, the mutation T530A was introduced into pCDF-GacH using Gibson Assembly site-directed mutagenesis and the primers gacH-T530A-F, gacH-T530A-R, Str-isoF and Str-isoR.

Identification of hGIIA-resistant GAS transposon mutants.

The GAS M1T1 5448 Krmit transposon mutant library 16 was grown to mid-log phase (OD600 = 0.4). 1 × 105 colony-forming units (CFU) were incubated with 27.5 μg/mL recombinant hGIIA 49 in triplicate for 1 h at 37°C and plated on THY agar plates supplemented with kanamycin. The position of the transposon insertion of resistant colonies was determined as described previously 50. hGIIA susceptibility experiments were performed as described previously 17.

Determination of selective metal concentrations.

To find the target concentration of Zn2+, colonies of 5448 WT and 5448ΔczcD 19 were scraped from THY agar plates, resuspended and washed in PBS to OD600=1, and used to inoculate freshly prepared mRPMI containing varying concentrations of Zn2+ to OD600=0.05 in a 96-well plate. Growth at 37 °C was monitored at OD595 every 15 min using the BMG Fluostar plate reader.

Tn-seq library screen for Zn2+ sensitivity.

The 5448 Krmit Tn-seq library at T0 generation 16 was thawed, inoculated into 150 mL prewarmed THY broth containing kanamycin and grown at 37 °C for 6 hrs. The culture (T1) was centrifuged at 4,000 x g for 15 min at 4 °C and the pellet resuspended in 32.5 mL saline. Freshly prepared mRPMI or mRPMI containing 10 μM or 20 μM Zn2+ was inoculated with 500 μL culture into 39.5 mL media, creating a 1:20 fold inoculation. These T2 cultures were then grown at 37°C for exactly 6 hrs, at which point 2 mL of these cultures were inoculated again into 38 mL of freshly prepared mRPMI alone or mRPMI containing 10 μM or 20 μM Zn2+. The remaining 38 mL of T2 culture was harvested by centrifugation at 4,000 x g for 10 min at 4 °C and pellets stored at −20 °C for later DNA extraction. Cultures were grown for additional 6 hrs, at which point T3 cultures were harvested by centrifugation at 4,000 x g for 10 min at 4 °C and pellets stored at −20 °C.

Tn-seq Krmit transposon insertion tags were prepared from the cell pellets as previously described 16,51. After quality control with the Bioanalyzer instrument (Agilent), the libraries of Krmit insertion tags were sequenced (50-nt single end reads) on an Illumina HiSeq 1500 in the Institute for Bioscience and Biotechnology Research (IBBR) Sequencing Core at the University of Maryland, College Park. Tn-seq read datasets were analyzed (quality, filtering, trimming, alignment, visualization) as previously described 16,51 using the M1T1 5448 genome as reference for read alignments. The ratios of mutant abundance comparing the output to input mutant pools were calculated as a fold change for each GAS gene using the DEseq2 and EdgeR pipelines 51–53.

Drop test assays.

Strains 5448 WT, 5448ΔgacI, 5448ΔgacI:gacI, 5448ΔgacH, 5448ΔgacH:pgacH, S. mutans WT, SMUΔsccH, SMUΔsccH:psccH and SMUΔsccH:pgacH were grown in THY to mid-exponential growth phase, adjusted to OD600 = 0.6 and serially diluted. Five μL were spotted onto THY agar plates containing varying concentrations of Zn2+ (ZnSO4·7H2O). Plates were incubated at 37°C overnight and photographed.

Protein expression and purification.

To purify eGacH and eGacH-T530A, E. coli Rosetta (DE3) carrying the respective plasmid was grown in LB at 37 °C to OD600=0.4–0.6 and induced with 0.25 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at 18 °C for approximately 16 hrs. Bacteria were lysed in 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl by a microfluidizer cell disrupter. The soluble fractions were purified by Ni-NTA chromatography. The eluate was dialyzed into 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl in the presence of TEV protease (1 mg per 20 mg of protein) and reapplied to a Ni-NTA column equilibrated in 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl to remove the cleaved His-tag and any uncleaved protein from the sample. The protein was further purified by size exclusion chromatography on a Superdex 200 column in 20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl.

To express seleno-methionine labeled eGacH, E. coli Rosetta (DE3) carrying eGacH was grown in LB at 37 °C to OD600=0.5. The bacteria were centrifuged and resuspended in M9 minimal media supplemented with seleno-methionine. Protein expression was induced with 0.25 mM IPTG, and the cultures were grown at 16 °C for approximately 16 hrs. Seleno-methionine labeled eGacH was purified as described above.

Crystallization, data collection and structure solution.

eGacH crystallization conditions were initially screened using the JCSG Suites I–IV screens (Qiagen) at a protein concentration of 9 mg/mL by hanging drop vapor diffusion method. Crystals of Se-Met-substituted eGacH were grown in 0.1 M HEPES pH 7.5, 10% PEG8000, 8% ethylene glycol. Crystals were transferred into crystallization solution supplemented with 20% ethylene glycol and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. The data were collected at APS 22-ID at a wavelength of 0.9793 Å. Crystals of GroP•eGacH complex were obtained using crystallization solution containing 0.2 M calcium acetate, 0.1 M MES pH 6.0, 20% PEG8000. sn-Gro-1-P (Sigma Aldrich) was mixed with eGacH at 10 mM prior to crystallization. Initial crystals of GroP•eGacH complex belonged to the same crystal form as apo GacH, however, crystals of different morphology grew epitaxially after several days. These crystals displayed better diffraction and were used for structure determination of GroP•eGacH complex. Crystals were cryoprotected in crystallization solution supplemented with 10 mM sn-glycerol-1-phosphate and 20% ethylene glycol and vitrified in liquid nitrogen. The data were collected at SSRL BL9–2 at a wavelength of 0.97946 Å.

All data were processed and scaled using XDS and XSCALE 54. The structure of eGacH was solved by Se single-wavelength anomalous diffraction method. Se atoms positions were determined using HySS module in PHENIX 55. The structure was solved using AutoSol wizard in PHENIX 55. The model was completed using Coot 56 and refined using phenix.refine in PHENIX 55. Ramachandran distribution analysis of the eGacH final structure with MolProbity 57 indicates that 96.6% and 3.4% residues are in favored and allowed regions, respectively, with no outliers.

The structure of GroP•eGacH complex was solved by molecular replacement using Phaser in PHENIX 55 and the dimer of apo eGacH as a search model. The model was adjusted using Coot and refined using phenix.refine. Difference electron density corresponding to GroP molecules was readily identified after refinement. GroP molecules were modeled using Coot. The geometric restraints for GroP were generated using Grade Web Server (http://grade.globalphasing.org) (Global Phasing). The last several rounds of refinement were performed using 19 translation/libration/screw (TLS) groups, which were identified by PHENIX 55. Ramachandran distribution analysis of the GroP•eGacH final structure indicates that 97.2% and 2.8% residues are in favored and allowed regions, respectively, with no outliers. The structures were validated using Coot, MolProbity and wwPDB Validation Service (https://validate.wwpdb.org). Statistics for data collection, refinement, and model quality are listed in Supplementary Table 7.

In vitro assay of eGacH enzymatic activity.

16:0–6:0 NBD-phosphatidylglycerol lipid (Avanti) was purified by preparative thin layer chromatography (TLC) as described previously 25, dissolved in CH3OH and stored at −20 °C until use. The lipid was dried and dispersed in octyl-glucoside by sonication prior to addition of the remaining components. Reaction mixtures contained 0.05 M sodium succinate pH 6.3, 10 mM MnCl2, 0.05 M NaCl, 0.25 % octyl-glucoside, 20 μg NBD-phosphatidylglycerol, ultrasonically dispersed in 0.5 % octyl-glucoside (Branson 2200 bath sonicator) and either no enzyme, 20 μg eGacH, or 20 μg eGacH-T530A in a total volume of 0.02 mL. Following incubation at 37 °C for 3 hrs, the reaction was stopped by the addition of 0.08 mL CHCl3/CH3OH (2:1) and analyzed for fluorescence on a BioRad ChemiDoc MP Imaging System using the fluorescein preset mode, as described previously 25. The migration position of the NBD-diacylglycerol product was determined from the product of a separate reaction containing purified phospholipase C from B. cereus (Sigma Aldrich).

Isolation of cell wall.

Cell wall was isolated from exponential phase cultures by the SDS-boiling procedure and lyophilized as previously described 15.

GAC purification.

GAC was released from the cell wall by sequential digestion with mutanolysin (Sigma Aldrich) and recombinant PlyC amidase 15, and partially purified by a combination of size exclusion chromatography and ion-exchange chromatography. Mutanolysin digests contained 5 mg/mL of cell wall suspension in 0.1 M sodium acetate, pH 5.5, 2 mM CaCl2 and 5 U/mL mutanolysin. Following overnight incubation at 37 °C, GAC was separated from the cell wall by centrifugation at 13,000 x g, 10 min and precipitated from 80% acetone (−20 °C). The precipitate was sedimented (5,000 x g, 20 min), dried briefly under nitrogen gas and redissolved in 0.1 M Tris-Cl, pH 7.4 and digested with PlyC (50 μg/mL) overnight at 37 °C. Following PlyC digestion, GAC was recovered by acetone precipitation, as described above, redissolved in a small volume of 0.2 N acetic acid and chromatographed on a 25 mL column of BioGel P10 equilibrated in 0.2 N acetic acid. Fractions (1.5 mL) were collected and monitored for carbohydrate by the anthrone assay. Fractions containing GAC were combined, concentrated and desalted by spin column centrifugation (3,000 MW cutoff filter). GAC was loaded onto an 18 mL column of DEAE-Sephacel. The column was eluted with a 100 mL gradient of NaCl (0–1 M). Fractions were analyzed for carbohydrate by the anthrone assay and phosphate by the malachite green assay following digestion with 70% perchloric acid (see below). Fractions containing peaks of carbohydrate were combined, concentrated by spin column (3,000 MW cut off) and lyophilized.

Anthrone assay.

Total carbohydrate content was determined by a minor modification of the anthrone procedure. Reactions contained 0.08 mL of aqueous sample and water and 0.32 mL anthrone reagent (0.2% anthrone in concentrated H2SO4). The samples were heated to 100 °C, 10 min, cooled in water (room temperature) and the absorbance at 580 nm was recorded. GAC concentration was estimated using an l-Rha standard curve.

Phosphate assay.

Approximately 1.5 mg of GAS cell wall material was dissolved in 400 μL H2O and 8 μg/mL PlyC, and incubated at 37 °C, rotating for approximately 16 hrs. Additional PlyC was added and incubated for a further 4–6 hrs. To liberate SCC from S. mutans cell walls, 1.5 mg of S. mutans cell wall material was incubated 24 hrs with 1.5 U/mL mutanolysin in 400 μL of 0.1 M sodium acetate, pH 5.5, 2 mM CaCl2. The samples were incubated at 100°C for 20 min and centrifuged for 5 min at maximum speed in a table top centrifuge. The supernatant was transferred to a new micro-centrifuge tube and incubated with 2 N HCl at 100°C for 2 hrs. The samples were neutralized with NaOH, in the presence of 62.5 mM HEPES pH 7.5. To 100 μL of acid hydrolyzed sample, 2 μL of 1 U/μL alkaline phosphatase (Thermo Fisher) and 10 μL 10 x alkaline phosphatase buffer was added and incubated at 37 °C, rotating, overnight. Released phosphate was measured using the Pi ColorLock Gold kit (Innova Biosciences), according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Total phosphate content was determined by the malachite green method following digestion with perchloric acid. Samples containing 10 to 80 μL were heated to 110 °C with 40 μL 70% perchloric acid (Fisher Scientific) in 13 × 100 borosilicate disposable culture tubes for 1 h. The reactions were diluted to 160 μL with water and 100 μL was transferred to a flat-bottom 96-well culture plate. Malachite Green reagent (0.2 mL) was added and the absorbance at 620 nm was read after 10 min at room temperature. Malachite Green reagent contained 1 vol 4.2% ammonium molybdate tetrahydrate (by weight) in 4 M HCl, 3 vol 0.045% malachite green (by weight) in water and 0.01% Tween 20.

Glycerol assay.

Samples for glycerol measurement were prepared as described for the phosphate assay but were not digested with alkaline phosphatase. Instead glycerol concentration was measured using the Glycerol Colorimetric assay kit (Cayman Chemical) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Glycosyl composition analysis.

Glycosyl composition analysis of GAS and S. mutans cell wall samples was performed at the Complex Carbohydrate Research Center (Athens, GA) by combined gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS) of the per-O-trimethylsilyl derivatives of the monosaccharide methyl glycosides produced from the sample by acidic methanolysis as described previously 15.

Dot-blot analysis of GAC.

The semi-quantitative immuno-dot blot analysis of GAC expressed by GAS strains was conducted essentially as described 15 with a following minor modification: the PlyC-digested cell wall fractions were serial diluted before spotting to a nitrocellulose membrane.

Total phospholipid content analysis.

GAS cells (50 mL) grown in THY broth to OD600 = 0.5 were centrifuged, washed with PBS, resuspended in 5 mL PBS and incubated with PlyC (100 μg/ml) at 37 °C for 1 h. A total lipid extract was prepared by a modification of the Bligh-Dyer extraction, freed of non-lipid contaminants by Folch partitioning as described previously 15 and redissolved in 1 mL CHCl3/CH3OH (2:1). An aliquot (20 μL) was analyzed for total phospholipid using the malachite green phosphate assay following perchloric acid digestion at 120 °C, 1 h and the remainder was analyzed for phosphatidylglycerol, as described below.

Phosphatidylglycerol and NBD-diacylglycerol analysis.

The analysis of phosphatidylglycerol and NBD-diacylglycerol was performed using an Ultimate 3000 ultra HPLC system coupled to a Thermo Q-Exactive Orbitrap mass spectrometer equipped with a heated electrospray ion source (Thermo Scientific, CA, USA). Lipid extracts were separated on a Waters ACQUITY BEH C8 column (2.1 × 100 mm, 1.7 μm) with the temperature maintained at 40°C. The flow rate was 250 μL/min, and the mobile phases were consisted of 60:40 water/acetonitrile (A), and 90:10 isopropanol/acetonitrile (B), both containing 10 mM ammonium formate and 0.1% formic acid. The samples were eluted with a linear gradient from 32% B to 97% B over 25 min, maintained at 97% B for 4 min and re-equilibration with 32% B for 6 min. The sample injection volume was 5 μL. The mass spectrometer was operated in positive and negative ionization modes. The full scan and fragment spectra were collected at a resolution of 70,000 and 17,500, respectively. Data analysis and lipid identification were performed using Xcalibur 4.0 and Lipidsearch 4.1 (Thermo Fisher).

Total carbohydrate content analysis.

GAS cells (10 mL) grown in THY broth OD600 = 0.5 were centrifuged, washed twice with PBS, and resuspended in 0.2 mL distilled water. The cell suspension was assayed for carbohydrate content by the anthrone assay as described above.

Analysis of GAC for GroP.

GAC (prepared from ∼1.5 mg of cell wall) was hydrolyzed in 0.1 mL 0.5 M NaOH (100 ºC, 1 h) to release GroP, as described by Kennedy et al. (ref. 26). Following alkaline treatment, the reaction was neutralized with acetic acid, supplemented with 5 nmol of citronellyl phosphate (as internal standard) and centrifuged on an Amicon Ultra Centrifugal Filter (0.5 mL, 3,000 NWML). The filtrate was lyophilized and analyzed using a Q-Exactive mass spectrometer and an Ultimate 3000 ultra HPLC system (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using a silica-based SeQuant ZIC-pHILIC column (2.1 mm × 150 mm, 5 μm, Merck, Germany) with elution buffers consisting of (A) 20 mM (NH4)2CO3 with 0.1% NH4OH in H2O and (B) acetonitrile. The column temperature was maintained at 40°C, and the flow rate was set to 150 μL/min. MS detection was performed by electrospray ionization in negative ionization mode with source voltage maintained at 3.0 kV. The capillary temperature, sheath gas flow and auxiliary gas flow were set at 275 °C, 40 arb and 15 arb units, respectively. Full-scan MS spectra (mass range m/z 75 to 1000) were acquired with resolution R = 70,000 and AGC target 1e6. Extracted ion chromatograms for GroP and citronellyl phosphate were obtained from the LC-MS chromatograms and used to estimate relative GroP content.

Identification of the stereochemistry of the GroP moiety of GAC.

GroP was liberated from GAC by alkaline hydrolysis as described by Kennedy et al. (ref. 26) and re-fractionated on BioGel P10. The bulk of the GAC elutes in the void volume and GroP elutes in the inclusion volume as identified by LC-MS. Column fractions containing GroP were combined, concentrated by rotary evaporation (30°C, under reduced pressure) and desalted on BioGel P2. The stereochemistry of the GroP was determined by enzymatic method using the Amplite™ Fluorimetric sn-Gro-3-P Assay Kit (AAT Bioquest) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

NMR spectroscopy.

The NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker AVANCE III 700 MHz equipped with a 5 mm TCI Z-Gradient Cryoprobe (1H/13C/15N) and dual receivers and a Bruker AVANCE II 600 MHz spectrometer equipped with a 5 mm TXI inverse Z-Gradient 1H/D-31P/13C. The 1H and 13C NMR chemical shift assignments of the polysaccharide material were carried out in D2O solution (99.96 %) at 323.2 K unless otherwise stated. Chemical shifts are reported in ppm using internal sodium 3-trimethylsilyl-(2,2,3,3-2H4)-propanoate (TSP, δH 0.00 ppm), external 1,4-dioxane in D2O (δC 67.40 ppm) and 2 % H3PO4 in D2O (δP 0.00 ppm) as reference. The 1H,1H-TOCSY experiments (dipsi2ph) were recorded with mixing times of 10, 30, 60, 90 and 120 ms. The 1H,1H-NOESY experiments 58 were collected with mixing times of 100 and 200 ms. A uniform and non-uniform sampling (50 and 25 % NUS) were used for the multiplicity-edited 1H,13C-HSQC experiments 59 employing an echo/antiecho-TPPI gradient selection with and without decoupling during the acquisition. The 2D 1H,13C-HSQC-TOCSY were acquired using MLEV17 for homonuclear Hartman-Hahn mixing, an echo/antiecho-TPPI gradient selection with decoupling during acquisition and mixing times of 20, 40, 80 and 120 ms. The 2D 1H,31P-Hetero-TOCSY experiments 60 were collected using a DIPSI2 sequence with mixing times of 10, 20, 30, 50 and 80 ms. The 2D 1H,31P-HMBC experiments were recorded using an echo/antiecho gradient selection and mixing times of 25, 50 and 90 ms. The 3D 1H,13C,31P 27 spectra were obtained using echo/antiecho gradient selection and constant time in t2 with a nominal value of nJCP of 5 Hz and without multiplicity selection. The spectra were processed and analyzed using TopSpin 4.0.1 software (Bruker BioSpin).

Statistical analysis.

Unless otherwise indicated, statistical analysis was carried out on pooled data from at least three independent biological repeats. A 2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni multiple comparison test was used to compare multiple groups. A P value equal to or less that 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Data availability

Illumina sequencing reads from the Tn-seq analysis were deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under the accession number SRP150081. The Tn-seq data, analyses, and pipeline for the Tn-seq analyses are accessible under the DOI number 10.5281/zenodo.2541163 in GitHub as the following link http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.2541163. Atomic coordinates and structure factors of the reported crystal structures have been deposited to the Protein Data Bank with accession codes 5U9Z (apo eGacH) and 6DGM (GroP•eGacH complex). All data generated during this study are included in the article and supplementary information files or will be available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Center of Biomedical Research Excellence (COBRE) Pilot Grant (to NK, KVK and JSR) supported by NIH grant P30GM110787 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS), NIH grant R56AI135021 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) (to NK), VIDI grant 91713303 from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) (to NMvS and VPvH), the Swedish Research Council (no. 2013–4859 and 2017–03703) and The Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation (to GW), NIH grant P30GM110787 from the NIGMS and NIH grant 1S10OD021753 (to AJM), the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (to MJW), grants from CNRS, ANR (MNaims ANR-17-CE17–0012-01) and FRM (SPF20150934219) (to GL), NIH grant AI047928 from NIAID (to KSM and YLB) and NIH grant AI094773 (to NMES and ATB).

Carbohydrate composition analysis at the Complex Carbohydrate Research Center was supported by the Chemical Sciences, Geosciences and Biosciences Division, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, U.S. Department of Energy grant (DE-FG02–93ER20097) to Parastoo Azadi. Use of the Advanced Photon Source was supported by the U. S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under Contract No. W-31–109-Eng-38 and NIH grants S10_RR25528 and S10_RR028976. Use of the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences under Contract No. DE-AC02–76SF00515. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the DOE Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and by the NIH, NIGMS including P41GM103393. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NIGMS or NIH.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Brown S, Santa Maria JP Jr. & Walker S Wall teichoic acids of Gram-positive bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol 67, 313–336 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weidenmaier C & Peschel A Teichoic acids and related cell-wall glycopolymers in Gram-positive physiology and host interactions. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 6, 276–287 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mistou MY, Sutcliffe IC & van Sorge NM Bacterial glycobiology: rhamnose-containing cell wall polysaccharides in Gram-positive bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev 40, 464–479 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang DH, Rama Krishna N & Pritchard DG Characterization of the group A streptococcal polysaccharide by two-dimensional 1H-nuclear-magnetic-resonance spectroscopy. Carbohydr. Res 155, 193–199 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.St Michael F et al. Investigating the candidacy of the serotype specific rhamnan polysaccharide based glycoconjugates to prevent disease caused by the dental pathogen Streptococcus mutans. Glycoconj. J. 35, 53–64 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van der Beek SL et al. GacA is essential for Group A Streptococcus and defines a new class of monomeric dTDP-4-dehydrorhamnose reductases (RmlD). Mol. Microbiol 98, 946–962 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsuda H, Yamashita Y, Shibata Y, Nakano Y & Koga T Genes involved in bacitracin resistance in Streptococcus mutans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 46, 3756–3764 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De A et al. Deficiency of RgpG causes major defects in cell division and biofilm formation, and deficiency of LytR-CpsA-Psr family proteins leads to accumulation of cell wall antigens in culture medium by Streptococcus mutans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 83, e00928 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nagata E et al. Serotype-specific polysaccharide of Streptococcus mutans contributes to infectivity in endocarditis. Oral. Microbiol. Immunol 21, 420–423 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henningham A et al. Virulence role of the GlcNAc side chain of the Lancefield cell wall carbohydrate antigen in non-M1-serotype Group A Streptococcus. mBio 9, e02294 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Sorge NM et al. The classical Lancefield antigen of Group A Streptococcus is a virulence determinant with implications for vaccine design. Cell Host Microbe 15, 729–740 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kabanova A et al. Evaluation of a Group A Streptococcus synthetic oligosaccharide as vaccine candidate. Vaccine 29, 104–114 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sabharwal H et al. Group A streptococcus (GAS) carbohydrate as an immunogen for protection against GAS infection. J. Infect. Dis. 193, 129–135 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shibata Y, Yamashita Y, Ozaki K, Nakano Y & Koga T Expression and characterization of streptococcal rgp genes required for rhamnan synthesis in Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun 70, 2891–2898 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rush JS et al. The molecular mechanism of N-acetylglucosamine side-chain attachment to the Lancefield group A carbohydrate in Streptococcus pyogenes. J. Biol. Chem 292, 19441–19457 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Le Breton Y et al. Essential genes in the core genome of the human pathogen Streptococcus pyogenes. Sci. Rep 5, 9838 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Hensbergen VP et al. Streptococcal Lancefield polysaccharides are critical cell wall determinants for human Group IIA secreted phospholipase A2 to exert its bactericidal effects. PLoS Pathog. 14, e1007348 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weiss JP Molecular determinants of bacterial sensitivity and resistance to mammalian Group IIA phospholipase A2. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1848, 3072–3077 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ong CL, Gillen CM, Barnett TC, Walker MJ & McEwan AG An antimicrobial role for zinc in innate immune defense against group A streptococcus. J. Infect. Dis 209, 1500–1508 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Graham MR et al. Virulence control in group A Streptococcus by a two-component gene regulatory system: global expression profiling and in vivo infection modeling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 13855–13860 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu D et al. Structure-based mechanism of lipoteichoic acid synthesis by Staphylococcus aureus LtaS. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 1584–1589 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schirner K, Marles-Wright J, Lewis RJ & Errington J Distinct and essential morphogenic functions for wall- and lipo-teichoic acids in Bacillus subtilis. EMBO J. 28, 830–842 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Campeotto I et al. Structural and mechanistic insight into the Listeria monocytogenes two-enzyme lipoteichoic acid synthesis system. J. Biol. Chem 289, 28054–28069 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fischer W, Laine RA & Nakano M On the relationship between glycerophosphoglycolipids and lipoteichoic acids in Gram-positive bacteria. II. Structures of glycerophosphoglycolipids. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 528, 298–308 (1978). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karatsa-Dodgson M, Wormann ME & Grundling A In vitro analysis of the Staphylococcus aureus lipoteichoic acid synthase enzyme using fluorescently labeled lipids. J. Bacteriol 192, 5341–5349 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kennedy EP, Rumley MK, Schulman H & Van Golde LM Identification of sn-glycero-1-phosphate and phosphoethanolamine residues linked to the membrane-derived oligosaccharides of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem 251, 4208–4213 (1976). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marino JP et al. Three-dimensional triple-resonance 1H, 13C, 31P experiment: sequential through-bond correlation of ribose protons and intervening phosphorus along the RNA oligonucleotide backbone. J. Am. Chem. Soc 116, 6472–6473 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heymann H, Manniello JM & Barkulis SS Structure of streptococcal cell walls. V. Phosphate esters in the walls of group A Streptococcus pyogenes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 26, 486–491 (1967). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Emdur LI, Saralkar C, McHugh JG & Chiu TH Glycerolphosphate-containing cell wall polysaccharides from Streptococcus sanguis. J. Bacteriol 120, 724–732 (1974). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prakobphol A, Linzer R & Genco RJ Purification and characterization of a rhamnose-containing cell wall antigen of Streptococcus mutans B13 (serotype d). Infect. Immun 27, 150–157 (1980). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pritchard DG, Michalek SM, McGhee JR & Furner RL Structure of the serotype f polysaccharide antigen of Streptococcus mutans. Carbohydr. Res 166, 123–131 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pritchard DG, Gregory RL, Michalek SM & McGhee JR Characterization of the serotype e polysaccharide antigen of Streptococcus mutans. Mol. Immunol 23, 141–145 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vickery CR, Wood BM, Morris HG, Losick R & Walker S Reconstitution of Staphylococcus aureus lipoteichoic acid synthase activity identifies Congo red as a selective inhibitor. J. Am. Chem. Soc 140, 876–879 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Neuhaus FC & Baddiley J A continuum of anionic charge: structures and functions of D-alanyl-teichoic acids in Gram-positive bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev 67, 686–723 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peschel A et al. Inactivation of the dlt operon in Staphylococcus aureus confers sensitivity to defensins, protegrins, and other antimicrobial peptides. J. Biol. Chem 274, 8405–8410 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Falagas ME, Rafailidis PI & Matthaiou DK Resistance to polymyxins: Mechanisms, frequency and treatment options. Drug Resist. Updat 13, 132–138 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Djoko KY, Ong CL, Walker MJ & McEwan AG The role of copper and zinc toxicity in innate immune defense against bacterial pathogens. J. Biol. Chem 290, 18954–18961 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ong CL, Walker MJ & McEwan AG Zinc disrupts central carbon metabolism and capsule biosynthesis in Streptococcus pyogenes. Sci. Rep 5, 10799 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McDevitt CA et al. A molecular mechanism for bacterial susceptibility to zinc. PLoS Pathog. 7, e1002357 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Buckland AG & Wilton DC Inhibition of secreted phospholipases A2 by annexin V. Competition for anionic phospholipid interfaces allows an assessment of the relative interfacial affinities of secreted phospholipases A2. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1391, 367–376 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koprivnjak T, Peschel A, Gelb MH, Liang NS & Weiss JP Role of charge properties of bacterial envelope in bactericidal action of human group IIA phospholipase A2 against Staphylococcus aureus. J. Biol. Chem 277, 47636–47644 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hunt CL, Nauseef WM & Weiss JP Effect of d-alanylation of (lipo)teichoic acids of Staphylococcus aureus on host secretory phospholipase A2 action before and after phagocytosis by human neutrophils. J. Immunol 176, 4987–4994 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carapetis JR, Steer AC, Mulholland EK & Weber M The global burden of group A streptococcal diseases. Lancet Infect. Dis 5, 685–694 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goldstein I, Rebeyrotte P, Parlebas J & Halpern B Isolation from heart valves of glycopeptides which share immunological properties with Streptococcus haemolyticus group A polysaccharides. Nature 219, 866–868 (1968). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ayoub EM & Dudding BA Streptococcal group A carbohydrate antibody in rheumatic and nonrheumatic bacterial endocarditis. J. Lab. Clin. Med 76, 322–332 (1970). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kirvan CA, Swedo SE, Heuser JS & Cunningham MW Mimicry and autoantibody-mediated neuronal cell signaling in Sydenham chorea. Nat. Med 9, 914–920 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Horton RM, Hunt HD, Ho SN, Pullen JK & Pease LR Engineering hybrid genes without the use of restriction enzymes: gene splicing by overlap extension. Gene 77, 61–68 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Trevino J, Liu Z, Cao TN, Ramirez-Pena E & Sumby P RivR is a negative regulator of virulence factor expression in group A Streptococcus. Infect. Immun 81, 364–372 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ghomashchi F et al. Preparation of the full set of recombinant mouse- and human-secreted phospholipases A2. Methods Enzymol. 583, 35–69 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Le Breton Y & McIver KS Genetic manipulation of Streptococcus pyogenes (the Group A Streptococcus, GAS). Curr. Protoc. Microbiol 30, Unit 9D 3 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Le Breton Y et al. Genome-wide discovery of novel M1T1 group A streptococcal determinants important for fitness and virulence during soft-tissue infection. PLoS Pathog. 13, e1006584 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Anders S & Huber W Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol. 11, R106 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ & Smyth GK edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26, 139–140 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kabsch W Xds. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 66, 125–132 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Adams PD et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr 66, 213–221 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG & Cowtan K Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr 66, 486–501 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chen VB et al. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr 66, 12–21 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wagner R & Berger S Gradient-selected NOESY-A fourfold reduction of the measurement time for the NOESY Experiment. J. Magn. Reson. A 123, 119–121 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Willker W, Leibfritz D, Kerssebaum R & Bermel W Gradient selection in inverse heteronuclear correlation spectroscopy. Magn. Reson. Chem 31, 287–292 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kellogg GW Proton-detected hetero-TOCSY experiments with application to nucleic acids. J. Magn. Reson 98, 176–182 (1992). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Illumina sequencing reads from the Tn-seq analysis were deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under the accession number SRP150081. The Tn-seq data, analyses, and pipeline for the Tn-seq analyses are accessible under the DOI number 10.5281/zenodo.2541163 in GitHub as the following link http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.2541163. Atomic coordinates and structure factors of the reported crystal structures have been deposited to the Protein Data Bank with accession codes 5U9Z (apo eGacH) and 6DGM (GroP•eGacH complex). All data generated during this study are included in the article and supplementary information files or will be available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.