Abstract

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) flow in the brain ventricles is critical for brain development. Altered CSF flow dynamics have been implicated in congenital hydrocephalus (CH) characterized by the potentially lethal expansion of cerebral ventricles if not treated. CH is the most common neurosurgical indication in children effecting 1 per 1000 infants. Current treatment modalities are limited to antiquated brain surgery techniques, mostly because of our poor understanding of the CH pathophysiology. We lack model systems where the interplay between ependymal cilia, embryonic CSF flow dynamics and brain development can be analyzed in depth. This is in part due to the poor accessibility of the vertebrate ventricular system to in vivo investigation. Here, we show that the genetically tractable frog Xenopus tropicalis, paired with optical coherence tomography imaging, provides new insights into CSF flow dynamics and role of ciliary dysfunction in hydrocephalus pathogenesis. We can visualize CSF flow within the multi-chambered ventricular system and detect multiple distinct polarized CSF flow fields. Using CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing, we modeled human L1CAM and CRB2 mediated aqueductal stenosis. We propose that our high-throughput platform can prove invaluable for testing candidate human CH genes to understand CH pathophysiology.

Subject terms: High-throughput screening, Disease model

Introduction

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) provides protection for the brain in the rigid cranium, clears waste produced by brain cells, and circulates growth factors important for neurodevelopment1. After neural tube closure, CSF is secreted primarily by the choroid plexus in the lateral ventricles, flows sequentially through the third and fourth ventricles, and then is reabsorbed by the arachnoid granulations and the lymphatic system2. The cilia on ependymal cells that line the ventricular cavities are important for CSF production and CSF flow through the ventricles3–6. As the choroid plexus pulsation and the wall motions dominates CSF dynamics in the center regions of the ventricles, ependymal cilia dominates near-wall cerebrospinal fluid dynamics in the lateral ventricles7 and regulates neuroblast migration8. Based on human and mouse genetics, mutations in genes that alter the structure and/or function of cilia can cause congenital hydrocephalus (CH); however, the mechanism of these genes on disease pathogenesis, including physiological embryonic CSF flow patterns, are poorly understood9–14.

CSF flow is critical for proper neurogenesis as it regulates neuroblast migration8. Understanding interactions between CSF flow and brain development is important to decipher the pathogenesis of hydrocephalus. While recent studies in single brain ventricular explants have highlighted potential complexities of CSF flow fields15, a global understanding of these networks in an intact, multi-compartmental ventricular system remains rudimentary. This is in part due to technical limitations of accessing the brain ventricles in a live animal through the rigid cranial vault and multilayered cortex, which impedes real-time imaging. Importantly, studies in other organ systems with cilia-lined fluid cavities (e.g., the fallopian tube or upper respiratory tract) have revealed the importance of the interaction between the cilia, chamber geometry, and fluid viscosity on the mechanical polarization of the fluid-flow. This is a severe limitation for explant experiments that are widely used to understand the polarized CSF circulation16–19. Therefore, studying explants of only one chamber of a post-mortem ventricle is suboptimal for analyzing the CSF flow network. Unfortunately, the lack of model systems enabling real time changes in CSF flow pattern and ventricular development has been a critical roadblock in understanding the pathogenesis of hydrocephalus.

The frog Xenopus tropicalis has a particular advantage for studying brain ventricular development and associated CSF flow dynamics. At stage 45 (Nieuwkoop - Faber staging. ~ post fertilization day 4 at 25 °C), the Xenopus brain is transparent, enabling Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT), a cross-sectional imaging modality that dynamically detects in vivo morphology at micrometer resolution20–23. We recently demonstrated that OCT imaging effectively detects structural changes in Xenopus craniofacial and cardiac structures, a useful screening tool for human genetic cranio-cardiac malformation research24. Here, we expand this platform to analyze in vivo CSF dynamics during ventricular development and use this approach to better understand the pathogenesis of patients with congenital hydrocephalus.

We show that Xenopus, coupled with OCT imaging, enables the simultaneous visualization of brain ventricle development, CSF flow dynamics, and ependymal cilia function. Fortuitously, we take advantage of endogenous, free-floating intraventricular particles for particle tracking revealing multiple, differentially polarized flow fields throughout the ventricular system. By adding F0 CRISPR, we can rapidly evaluate the impact of gene depletion on CSF flow and ventricular structure. By targeting human congenital hydrocephaly candidate genes, we show that we can recapitulate the aqueductal stenosis in frogs, as seen in non-communicating type of human hydrocephalus. Lastly, we gain insight into the pathogenesis of hydrocephalus by modeling the effects of the candidate CH disease genes. This work establishes a platform for the rapid testing of candidate human CH genes, expeditious given the recent large-scale sequencing efforts of this disease25.

Results

Xenopus CNS structural and CSF flow imaging

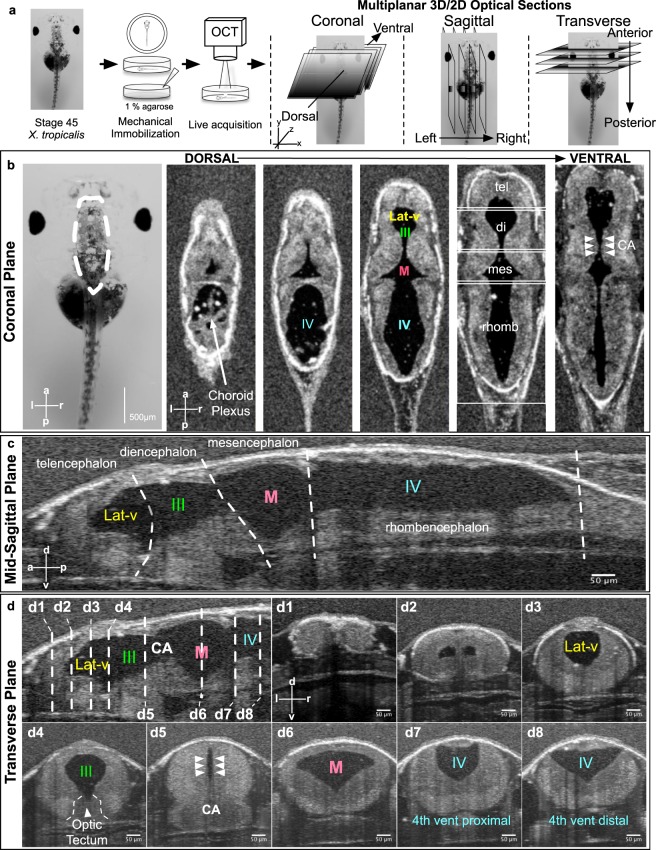

We applied OCT imaging to Xenopus tadpoles in vivo by embedding stage 45 tadpoles (post fertilization day 4 raised at 25 °C) in an agarose gel (1%) with the dorsal CNS structures positioned towards the OCT beam (Fig. 1a). This is a non-destructive, in vivo method of imaging as the tadpoles can be easily recovered from the agarose gel and raised to adulthood. Optical coherence imaging utilizes the information from backscattered light to create an image of the underlying tissue. It is analogous to clinical ultrasound but uses light. A single OCT depth profile is called an A-scan. When this A-scan is swept back and forth, the OCT system can create a 2D image (a B-scan). By combining multiple 2D images, the OCT system can also generate a 3D image of the underlying structure.

Figure 1.

In Vivo OCT imaging of the Xenopus tadpole ventricular system. (a) Stage 45 tadpoles are embedded in 1% low-melt agarose with the dorsal side of the animal facing the OCT beam. 2D and 3D images are taken. (b) A stage 45 tadpole as seen under light microscopy. Far left panel - white dotted line outlines the brain. A series of OCT images taken at progressively more ventral planes show the ventricular system with different parts of the brain. (c) A mid-sagittal view of the ventricular system at the midline. White dotted lines show the boundaries between different brain regions. (d) Transverse sections through the ventricular system along the anterior to posterior axis of the animal (d1–d8). The position of each section corresponds to the white dotted lines shown on the mid-sagittal view in the top left panel. (Lat-V: lateral ventricle, III: 3rd ventricle, M: Midbrain ventricle, IV: 4th ventricle, tel: Telencephalon, di: Diencephalon, mes: Mesencephalon, rhomb: Rhombencephalon, CA: Cerebral aqueduct).

For our purposes, the embryo is oriented such that the left-right axis is aligned along the x direction, the anteroposterior axis is aligned along the y direction, and the dorsal-ventral axis is aligned in the z direction (Fig. 1a). We then divided our analysis into 3D structural and 2D CSF flow imaging.

3D Structural Imaging

Once the CNS structures are captured by OCT imaging, we generate a 3D dataset that can be examined in three orthogonal, cross-sectional planes (Fig. 1b–d – Movies 1–2). In addition, we can isolate and measure specific ventricle volumes (Fig. S1d). In different planes, different anatomical structures can be readily isolated and measured:

Coronal plane (Fig. 1b) – Using this plane, we can visualize the four ventricles (lateral, 3rd, midbrain and 4th ventricle) in the xy-plane as we make 2D sections through the z-axis. To measure ventricular diameter, the user can examine each optical slice through the Z axis for the largest diameter for quantification (Figs 1b – S1b). Furthermore, the ventricular connections (e.g. cerebral aqueduct [CA]) can be visualized along the z-axis. Here, we should also note that as development progress in frogs, two lateral ventricles form (Fig. 1–d2) budding from the 3rd ventricle. At the tadpole stages we are imaging, they are visible as one and referred as one ventricle throughout the paper.

Mid-sagittal plane (Fig. 1c) – In this plane, we can visualize all four ventricles in a dorsal-ventral (DV) view along the anterior-posterior (AP) axis. We can outline the telencephalon, diencephalon, mesencephalon and rhombencephalon along with the associated ventricles. This plane is useful in examining CSF flow dynamics in each ventricle and also in relation to the adjacent ventricular system via the aqueducts. In this plane, we can also measure the total ventricular length along the AP axis (Figs 1c – S1a).

Transverse plane (Fig. 1d) – In this plane, we can measure the maximal dorsal-ventral (DV) length and the maximal width along the x-axis for each ventricle (Figs 1d- S1c). The transverse plane is particularly useful to measure the width and the DV length of the cerebral aqueduct that will eventually form the Xenopus equivalent of the aqueduct.

2D Imaging and particle tracking

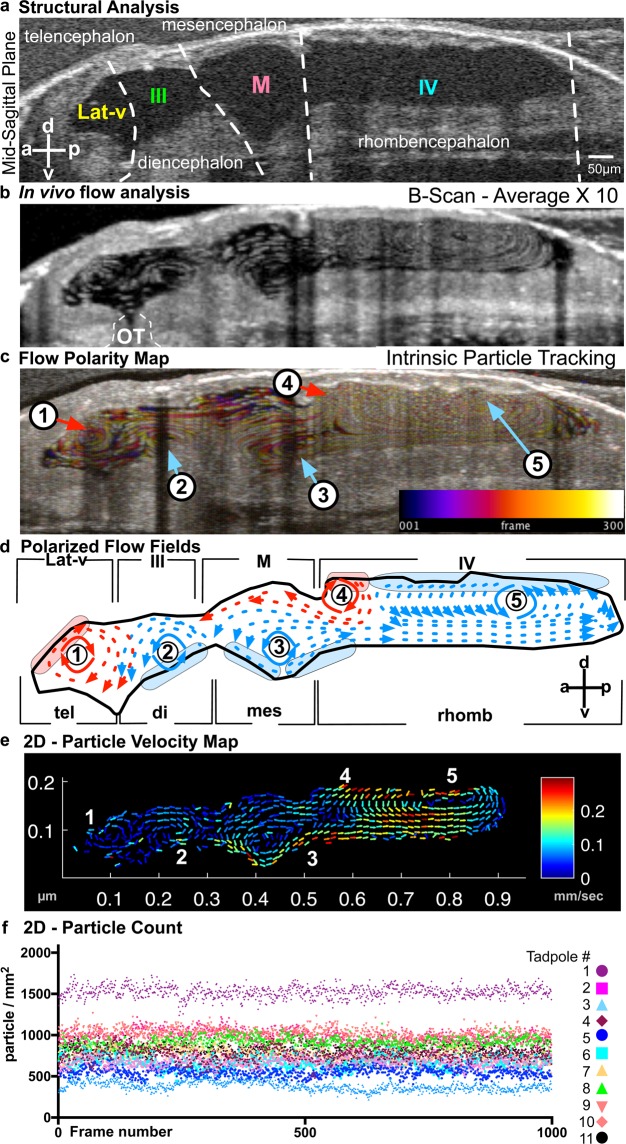

With 2D-cross sectional imaging, the scanning is fast enough to capture CSF flow. In the mid-sagittal plane where all four ventricles can be visualized simultaneously, we generated a global flow map. We took advantage of endogenous free-floating particles within the fluid-filled cavities of the ventricles. These particles appear in the range of 3.57–3.88 microns in diameter and can be readily resolved by OCT imaging. Using particle tracking techniques, we generated a CSF flow map (Fig. 2; see Methods for details) in the mid-sagittal plane. We mapped particle tracks over time in two ways: (1) B-Scan Average – We averaged 10 serial B-Scan images to form a map of the particle shift as a function of time (Fig. 2b). (2) Temporal color coding - We also used temporal color-coding to track particles over time. As a particle changes position it is coded with a different (warmer) color (ImageJ - see methods) (Fig. 2c). Based on these images, we discovered five discrete CSF “flow fields” (FFs) (Fig. 2d).

Figure 2.

Imaging ventricular CSF flow with OCT. (a) Mid-sagittal view of the brain allowing simultaneous visualization of the four ventricles. (b) B-scan image acquisition using OCT: Ventricles of a stage 45 tadpole harbor native free floating particles. In this image, the spatial position of the particles are recorded over time to demonstrate discrete flow patterns within each ventricle (OT: optical tectum). (c) Intrinsic Particle Tracking: Using ImageJ, we tracked particles using 300 frames of 2D images. Temporal color coding depicts their trajectory over time. Color bar represents color versus corresponding frame number in the color-coded image. Based on the trajectory map, 5 distinct flow fields were observed: FF1-FF5. We numbered flow fields 1 to 5 along the anterior-posterior axis. FF 1-Telencephalic flow and FF 2-Diencephalic flow are in the lateral ventricle. FF 3-Mesencephalic flow is in the 3rd ventricle. Finally, the 4th ventricle has 2 flow fields: FF 4-Anterior Rhombencephalic flow and FF 5-Posterior Rhombencephalic flow. (d) Outline of the ventricular system and vector maps of the CSF flow fields. Based on the trajectory map and real time observation (Movie 3); FF1 and FF4 are clockwise and FF2, 3 and 5 are counter-clockwise. (e) 2D Particle Velocity Map: Particle trajectories averaged across all frames (1000) to form flow velocities (see methods for details). Based on the particle velocity map and real time observations FF1 and FF2 are relatively slower compared to FF 3, 4 and 5. The fastest flow is recorded within the 4th ventricle. (f) 2D Particle Count (n = 11): Over 1000 frames, total particle number are counted for 11 different wild type tadpoles and plotted for each frame.

We expected CSF to flow along a major, single axis from the forebrain to the spinal cord; instead, we observed multiple flow fields that are clearly polarized independently with distinct velocities within different parts of the developing ventricle (Fig. 2d,e). While CSF flow fields were recently described in mammalian third ventricles15, differential polarization between the ventricles was unexpected and requires precise organization of the ependymal cells that drive flow. In describing the different flow fields, we oriented the embryo such that anterior is to the left and posterior is to the right with dorsal to the top in all of the following sections. In analyzing these images, we also quantified the endogenous particle counts for each frame and didn’t detect any significant variation between frames (1000 frames/acquisition/15 sec) or different tadpoles at the same stage (Fig. 2f).

FF1 - Telencephalic flow: This most anterior flow field is mostly confined to the telencephalon. On the mid-sagittal cross section, vector mapping shows a circular clockwise flow field along the anterior-posterior axis. The flow propels CSF anteriorly to the future lateral horns, inferiorly to the preoptic region and posteriorly towards the 3rd ventricle. Based on the velocity maps, FF1 is significantly slower than the mesencephalic and rhombencephalic flows (Fig. 2b–e – Movie 3).

FF2 - Diencephalic flow: This flow field forms superior to the zona limitans intrathalamica, a cell lineage restriction boundary between the vertebrate thalamus and the prethalamus, which is important for diencephalon development. Unlike FF1, the diencephalic flow field is counter-clockwise so that the anterior part of FF2 reinforces with the posterior part of FF1 to direct CSF towards the preoptic region. At the superior aspect, most of the flow is directed anteriorly from the cerebral aqueduct to the lateral ventricle. Together, FF1 and FF2 unite in the midst of the lateral ventricle and direct CSF flow ventrally (Fig. 2b–e – Movie 3). Similar to FF1, flow velocities are relatively low.

FF3 - Mesencephalic flow: The third flow field forms at the ventral surface of the midbrain ventricle just superior to the ventral tegmentum. This circular flow field is polarized counterclockwise. Superiorly CSF flow is directed to the lateral and third ventricle via the cerebral aqueduct and inferiorly to the fourth ventricle (Fig. 2b–e – Movie 3). Based on the flow velocities, dorsal flow (aimed towards the lateral ventricle) is significantly slower than the ventral flow (aimed towards the 4th ventricle). We recorded the slowest flow within the dorsal aspect of the midbrain ventricle.

FF4 - Anterior rhombencephalic flow: Interestingly, two discrete flow fields are observed within the rhombencephalon, each with an opposite polarization. Immediately posterior to the cerebellar region, the dorsal ventricular surface generates a clockwise flow field in which CSF is directed anteriorly to the midbrain ventricle (Fig. 2b–e – Movie 3).

FF5 - Posterior rhombencephalic flow: The posterior portion of the rhombencephalon contains the largest and fastest flow field, which flows counterclockwise. At the ventral aspect, CSF is directed posteriorly towards the spinal cord that is augmented with CSF flow originating at the posterior aspect of FF3 (Fig. 2b–e – Movie 3).

Taken together, these results demonstrate that OCT imaging can reliably detect CNS structures including the cerebral ventricles and CSF flow patterns in Xenopus tadpoles. Embryonic CSF flow in Xenopus is not uniform; there are multiple flow fields that allow continuous mixing of CSF between the ventricles. Since multiple flow fields are differentially polarized even within the same ventricle, there must exist a corresponding functional organization of ependymal cilia to generate this flow. Even at close proximity, these cells must drive extracellular fluid flow in opposite directions, suggesting a tight spatial control of the organization of ependymal ciliated cells.

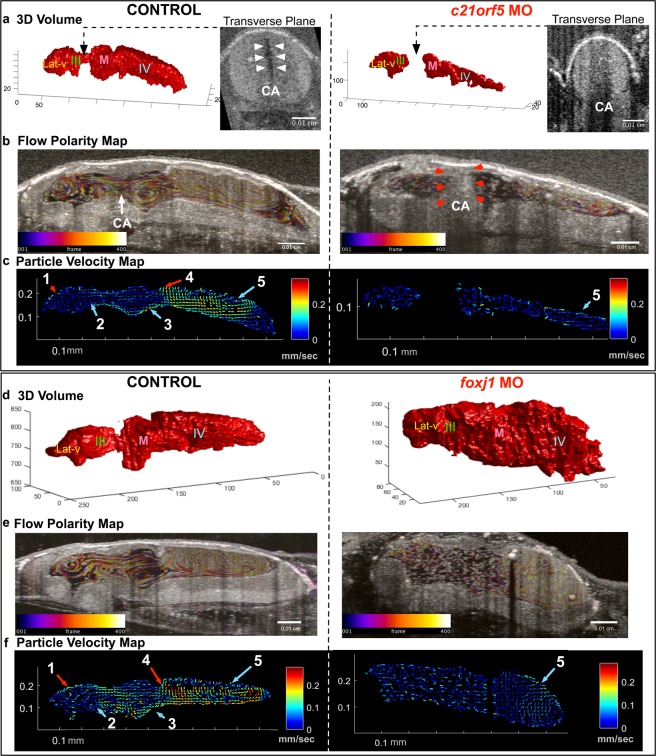

Loss of cilia motility or biogenesis causes discrete ventricular phenotypes

To test the sensitivity of OCT based particle tracking in low or no flow states and also to analyze the effects of the ependymal ciliary dysfunction on CSF flow dynamics and ventricle morphology, we perturbed cilia motility by knocking down c21orf59, which regulates the assembly of the outer dynein arms that drive ciliary beating26. These tadpoles demonstrated no or very slow CSF flow velocities as detected by OCT imaging (Fig. 3b,c). The ventricles were smaller in size and showed aqueductal stenosis between the lateral & 3rd ventricles and midbrain ventricle (Figs 3a,b, S2a, S3a), which can lead to a form of non-communicating CH. This data is in agreement with mouse experiments where, loss of cilia motility genes Ccdc39 and Mdnah5 also result in hydrocephaly3,5. In comparison, to explore changes with loss of ependymal cilia, we knocked down foxj1, a master regulator of motile cilia biogenesis27–29. We observed a dramatic loss of flow throughout the ventricles, but unlike the c21orf59 knockdown, the ventricles were significantly larger, resembling communicating hydrocephalus (Figs 3d,e, S2b,S3a). Of note, in both cases, despite the dramatic loss of cilia driven flow, FF5 remained partially intact (Figs 3c,f, S2a,b).

Figure 3.

Characterization of c21orf59 and foxj1 morphants. (a) 3D rendering of the tadpole ventricular system shows aqueductal stenosis and a smaller ventricular system in c21orf59 morphants compared to controls and (b,c) flow polarity and particle velocity maps confirm loss of FFs 1-4 as well as diminished flow in FF5. (d) 3D rendering of the tadpole ventricular system shows ventriculomegaly in foxj1 morphants and (e,f) flow polarity and particle velocity map confirm loss of FFs1-4 and slow FF5. (Lat-V: lateral ventricle, III: 3rd ventricle, M: Midbrain ventricle, IV: 4th ventricle).

Ependymal cilia drive CSF flow but this is not the only mechanism. Another contributor to CSF flow is the choroid plexus; a network of blood vessels and modified ependymal cells that produce CSF. In tadpoles, FF5 is adjacent to where the choroid plexus forms. As these cells are also ciliated, it is difficult to differentiate to what degree FF5 is a function of the ciliated surface or CSF secretion by the plexus. Clearly in both morphants, FF5 velocities were diminished but not lost even in cases where the cilia were disrupted (foxj1MO). Based on these findings, we speculate that CSF secretion via the choroid plexus may be contributing to FF5 formation. Future work can explore the contribution of the choroid plexus to CSF circulation at these early stages of development.

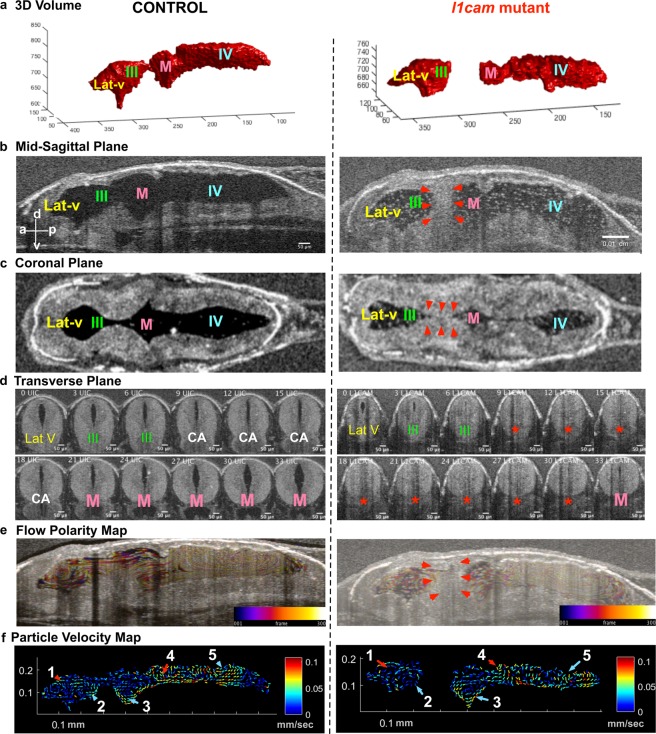

Loss of L1CAM function in Xenopus tadpoles causes aqueductal stenosis

Having established that we can readily visualize CSF flow, aqueductal stenosis, and communicating hydrocephalus, we next wanted to test if we model CH by depleting an established CH disease gene. In humans, loss-of-function (LOF) mutations in L1CAM cause X-linked hydrocephalus associated with stenosis of the cerebral aqueduct (OMIM#307000) and is the most common heritable form of hydrocephalus30. Several l1cam mouse knockouts exist with varying degrees of hydrocephalus, with or without aqueductal stenosis31. L1CAM is an integral membrane glycoprotein that mediates cell-to-cell adhesion at the cell surface but is not involved directly in cilia structure or function32. We depleted Xenopus l1cam using F0 CRISPR-Cas9. Briefly, we injected a guide RNA(sgRNA) and Cas9 protein into fertilized 1 cell embryos and raised F0 CRISPR mutant tadpoles to stage 45 (Day 4 at 25 °C) for OCT imaging. Injection of a sgRNA and Cas9 protein can readily lead to biallelic frameshift mutations in just a few hours after injection (Fig. S4a)28.

Most of the l1cam F0 CRISPR mutant tadpoles had normal external morphology with some narrowing of the cranium. To test for gene modification and depletion of gene product, we used a T7 Endonuclease I assay and detected modified alleles at the l1cam locus with F0 CRISPR and also saw a loss of anti-L1cam antibody signal in F0 CRISPR embryos (Fig. S4a,c). With OCT imaging, we detected cerebral aqueductal stenosis in l1cam F0 CRISPR mutant tadpoles (Fig. 4a–d) using both of the non-overlapping sgRNAs that we tested (Fig. S5). Overall, the length of each ventricle in its anterior to posterior aspect in the mid-sagittal plane was slightly shorter and smaller in the F0 CRISPR mutants as compared to the controls (Fig. S3a,b–d). In ~50% of the l1cam F0 CRISPR mutants, we detected complete stenosis of the cerebral aqueduct, while the remaining 50% showed a narrowing (Figs 4d, S3a,b–d). Next, we investigated the ventricular CSF flow and mapped FF1 to FF5, which appeared intact (Figs 4e,f, S2c, Movie 5).

Figure 4.

F0 CRISPR mutation in L1CAM causes cerebral aqueduct stenosis. The left column shows control and right column shows l1cam F0 CRISPR mutant images for all panels. (a) 3D rendering of the tadpole ventricular system shows aqueductal stenosis and a smaller ventricular system in l1cam F0 CRISPR mutant. (b) Mid sagittal view and (c) Coronal view of control and l1cam F0 CRISPR mutant, the later showing stenosis of the cerebral aqueduct (red arrowheads). (d) Transverse view of the control and l1cam F0 CRISPR mutant, starting at the end of the lateral ventricle through the cerebral aqueduct and ending in the midbrain ventricle. Control embryo shows normal opening of the duct whereas the mutant shows complete blockage (red star). (e) Relatively normal ciliary flow fields in the control and mutant animals. (f) 2D Particle Velocity Map shows intact FFs 1-5. (Lat-V: lateral ventricle, III: 3rd ventricle, M: Midbrain ventricle, IV: 4th ventricle).

From these results, we conclude that depletion of l1cam in Xenopus obstructs the communication between the lateral - 3rd and midbrain- 4th ventricles due to cerebral aqueduct stenosis without a major impact on the FF in the ventricles. Thus, Xenopus can also be used to model non-communicating hydrocephalus when formed independent of ciliary dysfunction and it remains to be seen if such phenotypes affects ependymal cilia flow in later development.

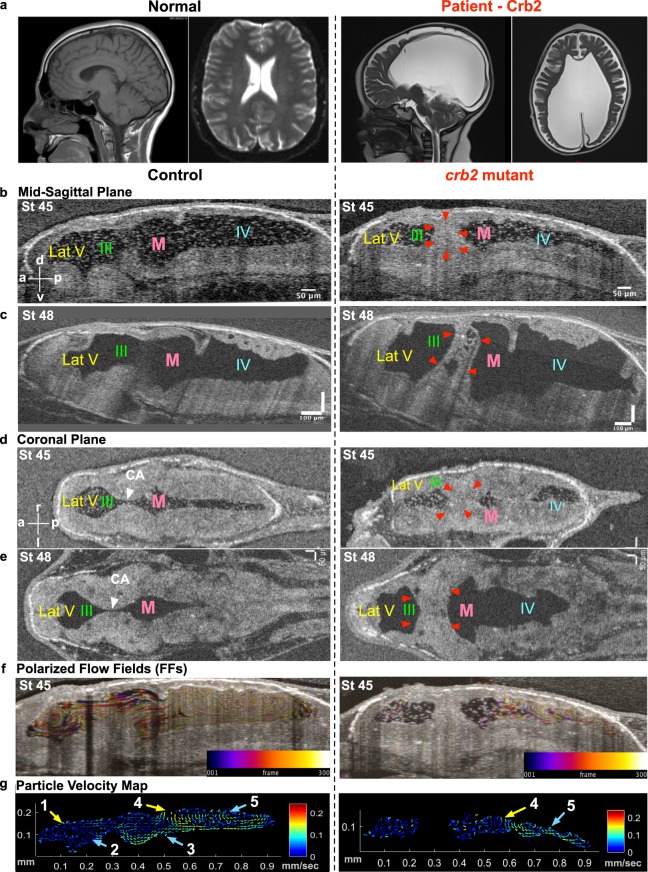

CRB2 loss-of-function leads to cerebral aqueduct stenosis and ventriculomegaly in humans and frogs

We next used our Xenopus system to test a CH gene discovered in our CH cohort. Briefly, we evaluated a child born by cesarean section for macrocephaly, secondary to prenatally diagnosed severe, bilateral cerebral ventriculomegaly (Fig. 5a), to a woman with a previous history of recurrent pregnancy loss. At birth, the infant’s head circumference was ten weeks advanced of gestational age (46 centimeters; >99%ile for age), and the patient underwent uncomplicated ventriculo-peritoneal shunt placement on the first day of life (Fig. 5a).

Figure 5.

Hydrocephaly phenotype with CRB2 mutations. (a) CT scan of a normal brain and patient brain, with enlargement of the brain ventricles. (b) Mid-sagittal view (d) Coronal view using OCT shows reduction in ventricular size along with CA stenosis in crb2 F0 CRISPR mutant tadpole brain at stage 45 as compared to controls. (c) Mid-sagittal view (e) Coronal view of control and crb2 F0 CRISPR mutant tadpole raised to stage 48 shows enlargement of the ventricles as compared to controls. This result was seen in 3 animals that survived to this later stage. (White arrow head – CA, red arrowheads – stenosis of CA). (f) Stage 45 tadpole particle tracking shows the impairment of the flow fields in the lateral 3rd and midbrain ventricles, but normal flow in the fourth ventricle for the crb2 F0 CRISPR mutant as compared to the control. (g) 2D Particle Velocity Map shows loss of FFs 1-3 and intact FFs 4-5. (Lat-V: lateral ventricle, III: 3rd ventricle, M: Midbrain ventricle, IV: 4th ventricle).

Prenatal and postnatal chromosome analysis, microarray, and a comprehensive genetic panel for craniofacial syndromes and L1CAM X-linked hydrocephalus were negative, and the patient was subsequently referred to our institution for whole exome sequencing (WES). We identified compound heterozygous mutations: c.1062delA (p.Thr354fs) and c.2400C>G (p.Asn800Lys) in Crumbs homolog 2 (CRB2), a gene involved in ciliogenesis33–35 and previously implicated in a rare Mendelian syndrome of prenatal onset ventriculomegaly and steroid-resistant nephropathy (OMIM#609720)33,36,37. Sanger sequencing of PCR amplicons confirmed p.Thr354fs and p.Asn800Lys compound heterozygosity in the patient, and heterozygosity in each respective parent (primer sequences available on request).

To test if we could recapitulate a CH phenotype in Xenopus, we depleted crb2 using F0 CRISPR and examined the ventricular system with OCT. At stage 45, crb2 F0 CRISPR mutant tadpoles had smaller ventricles (Figs 5b,d, S3a,e–g). Both the dorsal-ventral height and the width of the ventricles were smaller although the anterior-posterior length was only mildly affected (Fig. S3e–g). 78% of the F0 CRISPR mutants showed stenosis of the aqueduct and only 12% showed an open connection, a phenotype recapitulated in a second non-overlapping sgRNA (Fig. S5a). Importantly, the flow of the lateral - 3rd (FF1 and 2) and midbrain ventricles (FF3) was severely affected (Figs 5f,g, S2d, Movie 6), consistent with a role in cilia. Interestingly, we did not see any changes in the flow of the fourth ventricle (FF4 and FF5) (Fig. 5f,g, Movie 6), whether the flow in these posterior flow fields reflects near normal cilia function or choroid plexus flow remains to be determined. At stage 45, most of the crb2 F0 CRISPR mutant tadpoles had aqueductal obstruction but no obvious hydrocephalus. However, at stage 48 (3 weeks post fertilization), the few tadpoles that survived to this stage developed signs of hydrocephalus and the cerebral aqueduct remained obstructed (Fig. 5c,e). To evaluate our F0 CRISPR strategy for crb2, we detected gene modification at the crb2 locus and could rescue the crb2 aqueductal stenosis with human CRB2 mRNA. We also detected a reduction in crb2 signal by in situ hybridization especially in the ventricle (Fig. S5).

From these results, we conclude that depletion of crb2 in Xenopus obstructs the communication between the lateral - 3rd and midbrain - 4th ventricles due to cerebral aqueduct stenosis, and this is associated, and likely due, to impairment of cilia-driven CSF flow in select populations of ependymal cells.

Discussion

Congenital hydrocephalus (CH) is a common (1 per 1000 infants) and potentially lethal expansion of the CSF filled cerebral ventricles. Unfortunately, current treatment modalities are limited to morbid and antiquated brain surgery techniques38, in part due to our poor understanding of the interplay between ependymal cilia, embryonic CSF flow dynamics, and brain development. A recent NIH workshop identified a pressing need to establish animal models of CH in order to understand the genetic contribution to disease pathophysiology (Midbrain/Hindbrain Malformations and Hydrocephalus, 2014 NINDS). Our work addresses this need in two ways: 1) we develop a vertebrate animal model where the architecture of the brain ventricles can be visualized in real-time to map out an intact CSF flow network and 2) we use this model system to functionally assay the effect of CH genes on brain ventricular morphology, ependymal cilia function, and multi-ventricular CSF flow patterns.

CSF dynamics have been analyzed in various genetically tractable animal models including zebrafish, mice and Xenopus. As our goal is to model human disease, choosing an animal model as close to human is ideal. In isolated third ventricular explants, exogenously administered fluorescent particles can detect cilia-dependent flow15. However, these explant preparations cannot reproduce the three-dimensional CSF flow patterns in intact ventricular systems. Alternatively, CSF flow has been documented in zebrafish by injecting contrast reagents into the ventricular system39. However, Xenopus has certain evolutionary advantages for studying CH including lateral ventricles which the teleost lack and a neurulation process which is more similar between humans and Xenopus compared to zebrafish. In addition, the speed and low cost of making Xenopus models of CH makes Xenopus ideal for functionally testing CH candidate genes especially compared to the high cost of mouse. Previous work in Xenopus has identified CSF flow in a portion of the brain40,41. Miskevich in his work showed that fluorescent microspheres introduced to the ventricles with microinjection can be tracked using high speed camera in Albino Xenopus leavis tadpoles. He observed different velocities in different compartments of the brain which aligns with our current findings, yet this work was limited to visible parts of the ventricular system and didn’t show a global circulatory pattern41. Work by Hagencloher et al. showed that cilia were absent in foxj1 morphants, causing impaired CSF flow and fourth ventricle hydrocephalus in tadpole-stage embryos. This study also tracked fluorescent microspheres in the fourth ventricle using high speed imaging40. In our work, we comprehensively describe CSF flow through the entire ventricular system with its distinct polarity. We also reveal that the nature of ciliary gene affected can lead to distinct phenotypes and demonstrate its utility as a hydrocephalus model. When paired with OCT imaging, Xenopus provides a genetically tractable system where brain development, ventricular patterning, ependymal cilia function, and CSF microcirculatory dynamics can be simultaneously investigated and genetically perturbed in a non-destructive, label-free fashion. The candidate genes which show disease causality in our model, can be further studied using previously established methods to get at the underlying mechanism for gene function.

Using our Xenopus-OCT platform, we can detect the global CSF flow network mapped to CNS structures. We detect five discrete flow fields nested within three ventricles. Interestingly, unlike other ciliated surfaces that are polarized along a single axis, the CSF flow fields are location- and context-specific, suggesting patterning and polarization of the underlying ependymal cilia. For example, the telencephalic lateral ventricle has two discrete ciliary surfaces polarized in opposite directions generating a flow that unites in the center and forms a flow vector oriented towards the ventrally located optical tectum. Future work will define the cilia polarity and beating characteristics that are location specific to create these unique flow fields as well as the analysis of the 3D flow. Analyzing the subcellular architecture required for cilia polarization will prove fruitful for understanding how these flow fields are generated and how they change in disease states.

In analyzing flow fields with particle tracking, the presence of endogenous particles was fortuitous. By tracking particles, we can compute velocities in real time since the number and speed of these particles can be resolved with OCT imaging. Based on this data, we calculated average velocity maps to compare regional changes in velocities among the control and perturbed embryos. The average velocity maps can quantify mean velocity changes across multiple samples and highlight the dramatic changes in CSF flow across conditions (Fig. S2).

We also counted the number of particles within the ventricles and created heat maps to indicate particle concentration. Similar to averaged velocity maps, we formed averaged particle maps and analyzed the particle distribution across multiple embryos of a given condition. In wild types, we saw an even distribution of these particles across the ventricles, despite differentially polarized flow fields. The mean particle count per mm2 also remained constant over time (Fig. S2a). In c21orf59 morphants, where cilia motility was diminished and the tadpoles developed aqueductal stenosis further limiting ventricular mixing, we observed a slightly reduced total particle counts but surprisingly a relatively even distribution (Fig. S2a). In contrast, foxj1 morphants had significantly more particles even after adjusting for the larger ventricular volume but again the particles were evenly distributed (Fig. S2b). On the other hand, l1cam F0 CRISPR mutants had an uneven particle distribution where most of the particles were confined to the third and fourth ventricle, much less in the lateral ventricle. The change in distribution was not a result of a loss of particles; in fact, l1cam F0 CRISPR mutants had slightly more particles than wildtype controls (Fig. S2c). Surprisingly, crb2 F0 CRISPR mutants had the near opposite. Compared to wildtype controls, crb2 F0 CRISPR mutants had fewer particles that were confined to the lateral ventricles (Fig. S2d). These observations clearly suggest that alterations in CSF circulation, ependymal patterning and/or ventricular patterning may result in differential mixing or maldistribution of potential CSF derived factors. Whether these particles are vesicles or some other physiologically relevant structures and their importance in ventricle patterning and hydrocephalus pathogenesis is worth pursuing in the future.

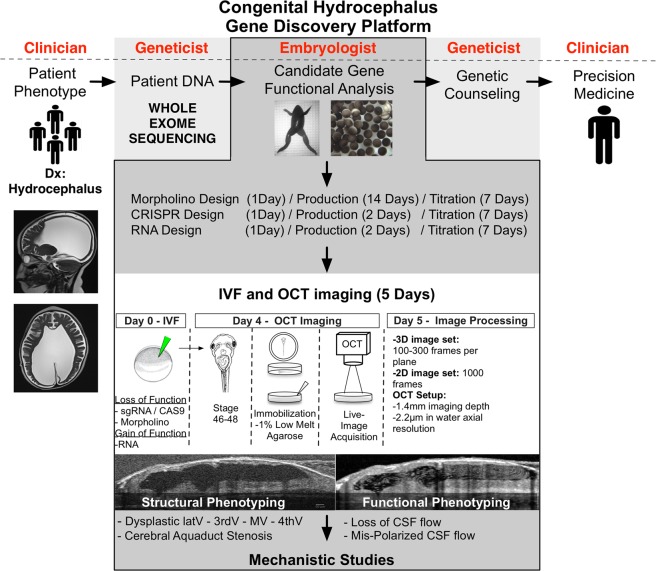

The genetic basis of hydrocephalus is at the early stages of gene discovery with only a handful of genes identified so far38. The most daunting problem for genetic analysis is high locus heterogeneity. To date only four bona fide genes, L1CAM, AP1S2, MPDZ and CCDC88C have been directly shown to be causal. With the plummeting cost in gene sequencing, we readily detect gene variants in our patients42. However, the high locus heterogeneity complicates assigning disease causality and is likely to identify a number of genes whose mechanism of hydrocephalus pathogenesis is unknown. Therefore, rapid functional testing of these variants in model systems remains a crucial step. Recently, an analysis of 27 families with recurrent hydrocephalus demonstrated a remarkably high contribution of recessive mutations to congenital hydrocephalus42. Xenopus is an ideal system to evaluate the genetic and physiological impact of these potential candidate genes inexpensively and in a short period of time (F0 CRISPR mutants can be generated and phenotyped in 5 days)28. If the candidate genes recapitulate the hydrocephalus phenotype in our Xenopus model, this data bolsters the evidence for disease relevance and is also crucial to provide mechanistic insight about hydrocephalus pathophysiology. Our results with L1CAM and CRB2 indicate that Xenopus is efficient and robust for CH modeling. As WES identifies novel CH candidate genes, our Xenopus model may serve as a robust system to validate implicated genes, as well as to use for drug screening to develop of targeted therapeutics for specific CH subtypes (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Schematic representation of the gene discovery platform for screening novel developmental hydrocephaly genes using Xenopus and OCT as a model system.

Materials and Methods

Xenopus tropicalis

Xenopus tropicalis were housed and cared for in our aquatics facility according to established protocols that were approved by the Yale Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) in accordance with NIH guidelines. Female and male mature Xenopus tropicalis were obtained from National Xenopus Resource.

Subjects and samples

All study procedures and protocols comply with Yale University’s Human Investigation Committee and Human Research Protection Program. The study has been approved by Yale Human Investigation Committee (HIC protocol #1602017144) and by Yale IRB board. Written informed consent for genetic studies was obtained from all participants. Our patient and her participating family members provided buccal swab samples (Isohelix SK-2S DNA buccal swab kits), medical records, radiological imaging studies, operative reports, and congenital hydrocephalus phenotype data.

Microinjections

Xenopus embryo in vitro fertilization and microinjections were performed as per standard protocols24. Embryos were injected with CRISPR sgRNA and mRNA at the one cell stage. For microinjections, borosilicate glass needles were calibrated to inject 1.6 ng Cas9 protein with 200 pg of the CRISPR sgRNA and a fluorescent tracer Alexa488 (Invitrogen). The target sequence for the l1cam CRISPRs are GGGGACTGCTCAGTAATCAC and GGTGGCTGTGCCCAGATCAT and for crb2 CRISPRs are GGCAGCCCTGTCAGAATGGA and GGTCTCCATCATAGCCCGCT. To make F0 CRISPR mutants, we generated sgRNAs using the EnGen sgRNA synthesis kit (NEB) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Full length human WT CRB2 RNA construct was a kind gift from Dr. Nishimura, Shiga University of Medical Science. It was sub-cloned in the standard Xenopus vector, pCS2 and capped mRNA was synthesized in vitro using the mMessage machine kit (Ambion) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. We injected 12.5 and 25 pg wild type human CRB2 RNA for rescue of crb2 F0 CRISPR mutants. The following morpholino oligonucleotide was injected at 4-cell stage: foxj1 translation blocking (8 ng/embryo 5′-ATGCTGCTGTTGGGCATCTTCCTCC-3′) and the c21orf59 translation blocking (8 ng/embryo 5′-CCTTCTTAACGTGTAAGCGCACCAT-3′). Post-injections, embryos were incubated in 1/9X MR supplemented with 50 μg/ml of gentamycin at 25 °C. Injections were confirmed by fluorescent lineage tracing with a Zeiss Lumar fluorescence stereomicroscope at stage 28 and tadpoles further raised at until stage 45.

F0 CRISPR mutant genotyping

Genomic DNA was extracted from each embryo using a DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen). The target regions were amplified by PCR with 35 cycles to facilitate the heteroduplex formation using Phusion® High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (NEB). PCR products were then annealed and digested with T7 Endonuclease I (NEB) as per the manufacturer’s instructions and run on a 2% agarose gel to determine genome targeting efficiency.

Immunofluorescence

We fixed control and mutant tadpoles at stage 45. We then dissected the brains and performed immunofluorescence of L1CAM (Abcam – ab24345) at 1:500. Alexa 488 (1:500) was used as a secondary antibody. Alexa 647 phalloidin (1:40) was used for actin staining. Embryos were mounted in Pro-Long Gold (Invitrogen) before imaging. Images were captured using a Zeiss 710 confocal microscope. Images were processed in Fiji, Image J, or Adobe Photoshop. Final figures were made in Adobe illustrator.

RNA in situ hybridization

X. tropicalis embryos were collected at stages 28 and stage 45. in-situ hybridization was performed according to standard protocols43. Additional probe information is available upon request.

Optic Coherence Tomography and Particle Tracking

Stage 45 (post-fertilization Day 4) tadpoles were immobilized in 2.5 ml of 1% low melt agar in a 35 mm diameter −10 mm height polystyrene petri dish. The tadpoles were aligned such that the dorsal side of the body was exposed en face to the OCT imaging field. We used a Thorlabs Ganymede 900 nm spectral domain-OCT Imaging System, which allows for 1.4 mm imaging depth in air + water −2.2 µm Axial Resolution in water. We obtained 2D cross sectional and 3D images by scanning at 36 kHz (36000 A-scans per second) with maximal 101 dB sensitivity. Measurements obtained from Thorlabs software ThorImageOCT version 4.4.6, analyzed using Prism7 statistical software. The data was analyzed to check if it fits normal distribution and an independent-samples t-test was conducted to compare different ventricular measurements for control and mutant embryos.

Flow velocimetry was performed in four steps: (1) anisotropy removal, (2) particle tracking, (3) region of interest selection, (4) particle displacement averaging to yield flow velocities. Further, we analyzed spatial particle distribution and present it as heatmaps (5). Next, (6) flow maps and heatmaps across multiple animals were created. The ventricle volume and 3D shape were also examined (7).

All image and data processing was performed using Matlab (The MathWorks, Natick, Massachusetts, USA, Version R2017b) and ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, USA, Version 1.5.1 u).

Anisotropy Removal

Images from OCT are usually not stored as isotropic images (images of equal physical height and length). Various settings and factors during acquisition dictate the aspect ratio of a pixel (or voxel respectively), such as refractive index and beam movement. Using this information, width and height of each pixel was adjusted to have square aspect ratio.

Particle Tracking

Particle tracking was performed using Mosaic particle tracker44 plugin build in ImageJ45. The plugin allows two-dimensional tracking for automated detection and analysis of particle trajectories. It is self-initializing, discriminates spurious detections, can handle temporary occlusion as well as particle appearance and disappearance from the image region to some degree.

Region of Interest Selection

In order to exclude any particles tracked outside the ventricle, the region of interest (ROI) was segmented. This was done manually using the MATLAB tool CROIEditor. All particle tracking data outside of the ROI was removed before any analysis.

Flow Velocity

Particle trajectories were averaged across all frames of each sample to yield mean flow at each position. For visualization purposes, the number of vectors in the flow velocity plots was reduced to 10-by-10 pixel non-overlapping windows. Within each window, the average flow was calculated. After averaging, magnitudes above the 97th percentile were considered outliers caused by incorrect particle tracking and therefore removed.

Particle Quantity and Particle Distribution Heatmaps

The number of particles in a given sample was calculated as the mean number of particles in each frame (extracted from particle tracking information) and was normalized using the sample’s ROI area. Where particle tracking yielded a high rate of false negatives (this was limited to foxj1 morphants where particle counts were significantly high), we shifted to a single-image-based approach consisting of H-dome transform46 and subsequent particle detection using boundary detection47.

Spatial distribution of particles is conveyed through heatmaps which are also based on the particle tracking information. They show the spatial particle density averaged over all frames of a video.

Cross-Animal Flow Fields and Heatmaps

Averaged flow maps and particle distribution heatmaps of animals of a group were created by first matching the ROIs to each other using Procrustes analysis48. Ventricle outlines were used as input to the Procrustes function, which returns rotation, translation and scaling to be applied to a set of points (describing the ventricle outline/ROI) in order to transform them such that they match another set of input points (another ventricle outline/ROI) as closely as possible (based on minimizing the sum of squared errors). This resulting transformation information was applied to corresponding flow vectors/heatmaps. Finally, all transformed flow vectors/heatmaps of a group were averaged.

Ventricle Volume Measurement and Plot

Employing a region growing algorithm49 we extracted 3D representations of the ventricle and its volume. Seed points for the region growing algorithm were chosen manually. High particle density caused unsatisfactory performance of this approach. In these cases, manual segmentation of several slices was performed and the full volume was interpolated. Validation of this method was conducted by comparing volume measurements using the above described automatic approach with the manual approach on 12 different samples. Volume measurements of the automatic and manual approach showed a mean error of 0.005602574 mm3 and a standard deviation of the error of 0.006480865 mm3. This is based on 11–12 slices of the z-stack with manual ventricle segmentation.

Whole-exome sequencing and variant calling

DNA was obtained from buccal swab samples in accordance with manufacturer protocol. Whole-exome sequencing was performed using the Nimblegen SeqxCap EZ MedExome Target Enrichment Kit (Roche Sequencing, Pleasanton, CA, USA) followed by 99 base paired-end sequencing on the Illumina HiSeq 2000 instrument at the Yale Center for Genome Analysis as previously described50. Sequence reads were mapped and aligned to the GRCh38/hg19 human reference genome using Burrows-Wheeler Aligner-MEM51 and further processed using Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) base quality score recalibration52, indel realignment, duplication marking and removal, and base quality score recalibration in accordance with GATK Best Practices recommendations53,54. Single nucleotide variants and small indels were called using GATK Haplotype Caller and annotated using ANNOVAR55, DbSNP56, 1000 Genomes57, NHLBI exome variant server58, and gnomAD and ExAC databases59.

Kinship analysis

Pedigree information and participant relationships were confirmed utilizing pairwise PLINK identity-by-descent calculation60.

De novo and Inherited (Dominant/Recessive) variant analysis

The Bayesian framework TrioDeNovo was used to call de novo mutations in the parent-offspring trio, consisting of our patient and her biological parents61. De novo candidates were filtered based on the following criteria of: (1) possessing a minor allele frequency (MAF) ≤ 5 × 10−3 in ExAC, (2) having a GATK variant quality score recalibration (VQSR) of ‘pass’, (3) meeting a minimum sequencing depth of 8 reads in the proband and 12 reads in each parent, (4) having a genotype quality (GQ) score ≥20 and alternate allele ratio ≥40%, (5) earning a TrioDeNovo data quality (DQ) score ≥7, and (6) being an exonic or canonical splice-site variant.

Transmitted variants were filtered similarly, with dominant variants meeting the following criteria of rareness and quality: (1) MAF ≤ 2 × 10−5 in ExAC, (2) GQ ≥ 20 and alternate allele ratio ≥40%, (3) GATK VQSR of ‘pass’, and (4) minimum sequencing depth of 8 reads in each participant. Recessive variants were filtered for rare (MAF ≤ 10−3 in ExAC) homozygous and compound heterozygous mutations that met read quality criteria as above (GQ ≥ 20, alternate allele ratio ≥40%, ‘pass’ GATK VQSR, and minimum sequencing depth ≥8).

We predicted the impact of nonsynonymous single nucleotide variants on protein function using the MetaSVM algorithm62, identifying mutations with rank scores greater than 0.83357 as deleterious (‘D-mis’). Only D-Mis and loss-of function mutations (nonsense, canonical splice-site, and frameshift indels) were considered potentially damaging to protein function.

All de novo and transmitted calls were verified by in silico visualization of aligned reads using the Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV)63 and BLAT search64. Resultant de novo and compound heterozygous calls were then verified in the patient and both parents by direct Sanger sequencing of PCR amplicons containing the mutation. A compound heterozygous mutations: c.1062delA (p.Thr354fs) and c.2400C>G (p.Asn800Lys) was identified in Crumbs homolog 2 (CRB2), The maternally-inherited p.Thr354fs mutation is a novel, frameshift deletion not reported in large, reference databases (gnomAD, ExAC, 1000 Genomes Project, NHLBI). The second, paternally inherited p.Asn800Lys mutation occurs in a highly conserved residue and is extremely rare in the general population (MAF of 1.4 × 10−4 in the ExAC database). Sparse case reports demonstrate pathogenicity of this substitution in compound heterozygous state with other CRB2 mutations; interestingly, all previously reported patients harboring the p.Asn800Lys mutation were of Ashkenazi Jewish descent33,36. Analysis from 128 genomes of Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry identified two CRB2-p.Asn800Lys heterozygotes, demonstrating a 1:64 carrier frequency in the population33,34.

Whole-Exome Sequencing

The average depth of coverage of the whole-exome sequencing data was 41.2×, with greater than 8x coverage in 96.40% of the target region for exome capture. The pedigree suggested a sporadic or autosomal recessive mode of inheritance, so compound heterozygous, homozygous, and de novo variants were prioritized. Variants were filtered for predicted deleteriousness using a series of in silico prediction algorithms, and excluded if above standard rare minor allele frequency thresholds in ExAC and other established databases.

Quantification and Statistical Analysis

The data was analyzed to check if it fits normal distribution. Measurements via OCT Thorlabs software represented by the mean value ± SEM for each group. Two-tailed Student’s t test analysis or a chi-square test of independence was used to examine all significant differences between groups as indicated in the figure legends. Significance was determined when the p value is lower than 0.05.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge members of Khokha lab and Kahle lab for their helpful discussions. This work was supported by NIH R33HL120783, and R01HD081379 to MKK, 5K12HD001401-15 to ED. MKK is a Mallinckrodt Scholar.

Author Contributions

P.D. and P.A. equally contributed to the manuscript. P.D., P.A., C.F., M.K., K.K., E.D. conceived and designed the experiments. P.D., E.D. performed Xenopus experiments. C.F., K.K. collected patient data. P.A., I.F. and S.J. developed a MATLAB interface to quantify particle velocities and 3D volumes. C.F., K.K. analyzed the human data. P.D., P.A., S.J., M.K., E.D. analyzed the frog data. P.D., P.A., C.F., M.K., K.K. and E.D. wrote and edited the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Priya Date and Pascal Ackermann contributed equally.

Contributor Information

Kristopher T. Kahle, Email: kristopher.kahle@yale.edu

Engin Deniz, Email: engin.deniz@yale.edu.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-42549-4.

References

- 1.Johanson CE, et al. Multiplicity of cerebrospinal fluid functions: New challenges in health and disease. Cerebrospinal Fluid Res. 2008;5:10. doi: 10.1186/1743-8454-5-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hladky SB, Barrand MA. Mechanisms of fluid movement into, through and out of the brain: evaluation of the evidence. Fluids Barriers CNS. 2014;11:26. doi: 10.1186/2045-8118-11-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ibanez-Tallon I, et al. Dysfunction of axonemal dynein heavy chain Mdnah5 inhibits ependymal flow and reveals a novel mechanism for hydrocephalus formation. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:2133–2141. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banizs B, et al. Dysfunctional cilia lead to altered ependyma and choroid plexus function, and result in the formation of hydrocephalus. Development (Cambridge, England) 2005;132:5329–5339. doi: 10.1242/dev.02153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abdelhamed Zakia, Vuong Shawn M., Hill Lauren, Shula Crystal, Timms Andrew, Beier David, Campbell Kenneth, Mangano Francesco T., Stottmann Rolf W., Goto June. A mutation in Ccdc39 causes neonatal hydrocephalus with abnormal motile cilia development in mice. Development. 2018;145(1):dev154500. doi: 10.1242/dev.154500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Del Bigio MR. Ependymal cells: biology and pathology. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;119:55–73. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0624-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siyahhan B, et al. Flow induced by ependymal cilia dominates near-wall cerebrospinal fluid dynamics in the lateral ventricles. J R Soc Interface. 2014;11:20131189. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2013.1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sawamoto K, et al. New neurons follow the flow of cerebrospinal fluid in the adult brain. Science. 2006;311:629–632. doi: 10.1126/science.1119133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee JE, Gleeson JG. Cilia in the nervous system: linking cilia function and neurodevelopmental disorders. Curr Opin Neurol. 2011;24:98–105. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e3283444d05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee L. Riding the wave of ependymal cilia: genetic susceptibility to hydrocephalus in primary ciliary dyskinesia. Journal of neuroscience research. 2013;91:1117–1132. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang J, Williams MA, Rigamonti D. Genetics of human hydrocephalus. J Neurol. 2006;253:1255–1266. doi: 10.1007/s00415-006-0245-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jimenez AJ, Dominguez-Pinos MD, Guerra MM, Fernandez-Llebrez P, Perez-Figares JM. Structure and function of the ependymal barrier and diseases associated with ependyma disruption. Tissue barriers. 2014;2:e28426. doi: 10.4161/tisb.28426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou JJ, Ding MP, Liu JR. [Research advances on associated genes and pathogenesis of hydrocephalus] Zhejiang Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2010;39:644–649. doi: 10.3785/j.issn.1008-9292.2010.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vogel P, et al. Congenital hydrocephalus in genetically engineered mice. Vet Pathol. 2012;49:166–181. doi: 10.1177/0300985811415708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Faubel R, Westendorf C, Bodenschatz E, Eichele G. Cilia-based flow network in the brain ventricles. Science. 2016;353:176–178. doi: 10.1126/science.aae0450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang S, Larina IV. In Vivo Imaging of the Mouse Reproductive Organs, Embryo Transfer, and Oviduct Cilia Dynamics Using Optical Coherence Tomography. Methods Mol Biol. 2018;1752:53–62. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-7714-7_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang S, Syed R, Grishina OA, Larina IV. Prolonged in vivo functional assessment of the mouse oviduct using optical coherence tomography through a dorsal imaging window. J Biophotonics. 2018;11:e201700316. doi: 10.1002/jbio.201700316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang BK, Gamm UA, Bhandari V, Khokha MK, Choma MA. Three-dimensional, three-vector-component velocimetry of cilia-driven fluid flow using correlation-based approaches in optical coherence tomography. Biomed Opt Express. 2015;6:3515–3538. doi: 10.1364/BOE.6.003515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ling Y, et al. Ex vivo visualization of human ciliated epithelium and quantitative analysis of induced flow dynamics by using optical coherence tomography. Lasers Surg Med. 2017;49:270–279. doi: 10.1002/lsm.22653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fujimoto JG, Pitris C, Boppart SA, Brezinski ME. Optical coherence tomography: an emerging technology for biomedical imaging and optical biopsy. Neoplasia. 2000;2:9–25. doi: 10.1038/sj.neo.7900071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boppart SA, Brezinski ME, Fujimoto JG. Optical coherence tomography imaging in developmental biology. Methods in molecular biology. 2000;135:217–233. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-685-1:217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gutierrez-Chico JL, et al. Optical coherence tomography: from research to practice. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;13:370–384. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jes025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fujimoto JG, et al. Optical biopsy and imaging using optical coherence tomography. Nat Med. 1995;1:970–972. doi: 10.1038/nm0995-970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deniz E, et al. Analysis of Craniocardiac Malformations in Xenopus using Optical Coherence Tomography. Sci Rep. 2017;7:42506. doi: 10.1038/srep42506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McAllister JP, 2nd, et al. An update on research priorities in hydrocephalus: overview of the third National Institutes of Health-sponsored symposium “Opportunities for Hydrocephalus Research: Pathways to Better Outcomes”. J Neurosurg. 2015;123:1427–1438. doi: 10.3171/2014.12.JNS132352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jaffe KM, et al. c21orf59/kurly Controls Both Cilia Motility and Polarization. Cell Rep. 2016;14:1841–1849. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.01.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu X, Ng CP, Habacher H, Roy S. Foxj1 transcription factors are master regulators of the motile ciliogenic program. Nature genetics. 2008;40:1445–1453. doi: 10.1038/ng.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bhattacharya D, Marfo CA, Li D, Lane M, Khokha MK. CRISPR/Cas9: An inexpensive, efficient loss of function tool to screen human disease genes in Xenopus. Dev Biol. 2015;408:196–204. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2015.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stubbs JL, Oishi I, Izpisua Belmonte JC, Kintner C. The forkhead protein Foxj1 specifies node-like cilia in Xenopus and zebrafish embryos. Nature genetics. 2008;40:1454–1460. doi: 10.1038/ng.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kousi M, Katsanis N. The Genetic Basis of Hydrocephalus. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2016;39:409–435. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-070815-014023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rolf B, Kutsche M, Bartsch U. Severe hydrocephalus in L1-deficient mice. Brain Res. 2001;891:247–252. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(00)03219-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haspel J, Grumet M. The L1CAM extracellular region: a multi-domain protein with modular and cooperative binding modes. Front Biosci. 2003;8:s1210–1225. doi: 10.2741/1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jaron R, et al. Expanding the phenotype of CRB2 mutations - A new ciliopathy syndrome? Clinical genetics. 2016;90:540–544. doi: 10.1111/cge.12764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carmi, S. et al. Sequencing an Ashkenazi reference panel supports population-targeted personal genomics and illuminates Jewish and European origins. Nature communications5, 4835, 10.1038/ncomms5835, http://www.nature.com/articles/ncomms5835#supplementary-information (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Omori Y, Malicki J. oko meduzy and related crumbs genes are determinants of apical cell features in the vertebrate embryo. Curr Biol. 2006;16:945–957. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.03.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Slavotinek A, et al. CRB2 Mutations Produce a Phenotype Resembling Congenital Nephrosis, Finnish Type, with Cerebral Ventriculomegaly and Raised Alpha-Fetoprotein. The American Journal of Human Genetics. 2015;96:162–169. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lamont RE, et al. Expansion of phenotype and genotypic data in CRB2-related syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet. 2016;24:1436–1444. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2016.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kahle KT, Kulkarni AV, Limbrick DD, Jr., Warf BC. Hydrocephalus in children. Lancet. 2016;387:788–799. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60694-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fame RM, Chang JT, Hong A, Aponte-Santiago NA, Sive H. Directional cerebrospinal fluid movement between brain ventricles in larval zebrafish. Fluids Barriers CNS. 2016;13:11. doi: 10.1186/s12987-016-0036-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hagenlocher C, Walentek P, M Ller C, Thumberger T, Feistel K. Ciliogenesis and cerebrospinal fluid flow in the developing Xenopus brain are regulated by foxj1. Cilia. 2013;2:12. doi: 10.1186/2046-2530-2-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miskevich F. Imaging fluid flow and cilia beating pattern in Xenopus brain ventricles. J Neurosci Methods. 2010;189:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2010.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shaheen R, et al. The genetic landscape of familial congenital hydrocephalus. Ann Neurol. 2017;81:890–897. doi: 10.1002/ana.24964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Khokha MK, et al. Techniques and probes for the study of Xenopus tropicalis development. Dev Dyn. 2002;225:499–510. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sbalzarini IF, Koumoutsakos P. Feature point tracking and trajectory analysis for video imaging in cell biology. J Struct Biol. 2005;151:182–195. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9:671–675. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vincent L. Morphological grayscale reconstruction in image analysis: applications and efficient algorithms. IEEE Trans Image Process. 1993;2:176–201. doi: 10.1109/83.217222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Deniz E, Jonas S, Khokha M, Choma MA. Endogenous contrast blood flow imaging in embryonic hearts using hemoglobin contrast subtraction angiography. Optics letters. 2012;37:2979–2981. doi: 10.1364/OL.37.002979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pierpont ME, et al. In Circulation. 2007;115:3015–3038. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.183056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Region Growing (2D/3D grayscale) - File Exchange - MATLAB Central, https://de.mathworks.com/matlabcentral/fileexchange/32532-region-growing-2d-3d-grayscale (2011).

- 50.Timberlake, A. T. et al. Two locus inheritance of non-syndromic midline craniosynostosis via rare SMAD6 and common BMP2 alleles. eLife5, 10.7554/eLife.20125 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McKenna A, et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome research. 2010;20:1297–1303. doi: 10.1101/gr.107524.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.DePristo MA, et al. A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nature genetics. 2011;43:491–498. doi: 10.1038/ng.806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Van der Auwera GA, et al. From FastQ data to high confidence variant calls: the Genome Analysis Toolkit best practices pipeline. Current protocols in bioinformatics. 2013;43:11.10.11–33. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi1110s43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic acids research. 2010;38:e164. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sherry ST, et al. dbSNP: the NCBI database of genetic variation. Nucleic acids research. 2001;29:308–311. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.1.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gibbs Richard A., Boerwinkle Eric, Doddapaneni Harsha, Han Yi, Korchina Viktoriya, Kovar Christie, Lee Sandra, Muzny Donna, Reid Jeffrey G., Zhu Yiming, Wang Jun, Chang Yuqi, Feng Qiang, Fang Xiaodong, Guo Xiaosen, Jian Min, Jiang Hui, Jin Xin, Lan Tianming, Li Guoqing, Li Jingxiang, Li Yingrui, Liu Shengmao, Liu Xiao, Lu Yao, Ma Xuedi, Tang Meifang, Wang Bo, Wang Guangbiao, Wu Honglong, Wu Renhua, Xu Xun, Yin Ye, Zhang Dandan, Zhang Wenwei, Zhao Jiao, Zhao Meiru, Zheng Xiaole, Lander Eric S., Altshuler David M., Gabriel Stacey B., Gupta Namrata, Gharani Neda, Toji Lorraine H., Gerry Norman P., Resch Alissa M., Flicek Paul, Barker Jonathan, Clarke Laura, Gil Laurent, Hunt Sarah E., Kelman Gavin, Kulesha Eugene, Leinonen Rasko, McLaren William M., Radhakrishnan Rajesh, Roa Asier, Smirnov Dmitriy, Smith Richard E., Streeter Ian, Thormann Anja, Toneva Iliana, Vaughan Brendan, Zheng-Bradley Xiangqun, Bentley David R., Grocock Russell, Humphray Sean, James Terena, Kingsbury Zoya, Lehrach Hans, Sudbrak Ralf, Albrecht Marcus W., Amstislavskiy Vyacheslav S., Borodina Tatiana A., Lienhard Matthias, Mertes Florian, Sultan Marc, Timmermann Bernd, Yaspo Marie-Laure, Mardis Elaine R., Wilson Richard K., Fulton Lucinda, Fulton Robert, Sherry Stephen T., Ananiev Victor, Belaia Zinaida, Beloslyudtsev Dimitriy, Bouk Nathan, Chen Chao, Church Deanna, Cohen Robert, Cook Charles, Garner John, Hefferon Timothy, Kimelman Mikhail, Liu Chunlei, Lopez John, Meric Peter, O’Sullivan Chris, Ostapchuk Yuri, Phan Lon, Ponomarov Sergiy, Schneider Valerie, Shekhtman Eugene, Sirotkin Karl, Slotta Douglas, Zhang Hua, McVean Gil A., Durbin Richard M., Balasubramaniam Senduran, Burton John, Danecek Petr, Keane Thomas M., Kolb-Kokocinski Anja, McCarthy Shane, Stalker James, Quail Michael, Schmidt Jeanette P., Davies Christopher J., Gollub Jeremy, Webster Teresa, Wong Brant, Zhan Yiping, Auton Adam, Campbell Christopher L., Kong Yu, Marcketta Anthony, Gibbs Richard A., Yu Fuli, Antunes Lilian, Bainbridge Matthew, Muzny Donna, Sabo Aniko, Huang Zhuoyi, Wang Jun, Coin Lachlan J. M., Fang Lin, Guo Xiaosen, Jin Xin, Li Guoqing, Li Qibin, Li Yingrui, Li Zhenyu, Lin Haoxiang, Liu Binghang, Luo Ruibang, Shao Haojing, Xie Yinlong, Ye Chen, Yu Chang, Zhang Fan, Zheng Hancheng, Zhu Hongmei, Alkan Can, Dal Elif, Kahveci Fatma, Marth Gabor T., Garrison Erik P., Kural Deniz, Lee Wan-Ping, Fung Leong Wen, Stromberg Michael, Ward Alistair N., Wu Jiantao, Zhang Mengyao, Daly Mark J., DePristo Mark A., Handsaker Robert E., Altshuler David M., Banks Eric, Bhatia Gaurav, del Angel Guillermo, Gabriel Stacey B., Genovese Giulio, Gupta Namrata, Li Heng, Kashin Seva, Lander Eric S., McCarroll Steven A., Nemesh James C., Poplin Ryan E., Yoon Seungtai C., Lihm Jayon, Makarov Vladimir, Clark Andrew G., Gottipati Srikanth, Keinan Alon, Rodriguez-Flores Juan L., Korbel Jan O., Rausch Tobias, Fritz Markus H., Stütz Adrian M., Flicek Paul, Beal Kathryn, Clarke Laura, Datta Avik, Herrero Javier, McLaren William M., Ritchie Graham R. S., Smith Richard E., Zerbino Daniel, Zheng-Bradley Xiangqun, Sabeti Pardis C., Shlyakhter Ilya, Schaffner Stephen F., Vitti Joseph, Cooper David N., Ball Edward V., Stenson Peter D., Bentley David R., Barnes Bret, Bauer Markus, Keira Cheetham R., Cox Anthony, Eberle Michael, Humphray Sean, Kahn Scott, Murray Lisa, Peden John, Shaw Richard, Kenny Eimear E., Batzer Mark A., Konkel Miriam K., Walker Jerilyn A., MacArthur Daniel G., Lek Monkol, Sudbrak Ralf, Amstislavskiy Vyacheslav S., Herwig Ralf, Mardis Elaine R., Ding Li, Koboldt Daniel C., Larson David, Ye Kai, Gravel Simon, Swaroop Anand, Chew Emily, Lappalainen Tuuli, Erlich Yaniv, Gymrek Melissa, Frederick Willems Thomas, Simpson Jared T., Shriver Mark D., Rosenfeld Jeffrey A., Bustamante Carlos D., Montgomery Stephen B., De La Vega Francisco M., Byrnes Jake K., Carroll Andrew W., DeGorter Marianne K., Lacroute Phil, Maples Brian K., Martin Alicia R., Moreno-Estrada Andres, Shringarpure Suyash S., Zakharia Fouad, Halperin Eran, Baran Yael, Lee Charles, Cerveira Eliza, Hwang Jaeho, Malhotra Ankit, Plewczynski Dariusz, Radew Kamen, Romanovitch Mallory, Zhang Chengsheng, Hyland Fiona C. L., Craig David W., Christoforides Alexis, Homer Nils, Izatt Tyler, Kurdoglu Ahmet A., Sinari Shripad A., Squire Kevin, Sherry Stephen T., Xiao Chunlin, Sebat Jonathan, Antaki Danny, Gujral Madhusudan, Noor Amina, Ye Kenny, Burchard Esteban G., Hernandez Ryan D., Gignoux Christopher R., Haussler David, Katzman Sol J., James Kent W., Howie Bryan, Ruiz-Linares Andres, Dermitzakis Emmanouil T., Devine Scott E., Abecasis Gonçalo R., Min Kang Hyun, Kidd Jeffrey M., Blackwell Tom, Caron Sean, Chen Wei, Emery Sarah, Fritsche Lars, Fuchsberger Christian, Jun Goo, Li Bingshan, Lyons Robert, Scheller Chris, Sidore Carlo, Song Shiya, Sliwerska Elzbieta, Taliun Daniel, Tan Adrian, Welch Ryan, Kate Wing Mary, Zhan Xiaowei, Awadalla Philip, Hodgkinson Alan, Li Yun, Shi Xinghua, Quitadamo Andrew, Lunter Gerton, McVean Gil A., Marchini Jonathan L., Myers Simon, Churchhouse Claire, Delaneau Olivier, Gupta-Hinch Anjali, Kretzschmar Warren, Iqbal Zamin, Mathieson Iain, Menelaou Androniki, Rimmer Andy, Xifara Dionysia K., Oleksyk Taras K., Fu Yunxin, Liu Xiaoming, Xiong Momiao, Jorde Lynn, Witherspoon David, Xing Jinchuan, Eichler Evan E., Browning Brian L., Browning Sharon R., Hormozdiari Fereydoun, Sudmant Peter H., Khurana Ekta, Durbin Richard M., Hurles Matthew E., Tyler-Smith Chris, Albers Cornelis A., Ayub Qasim, Balasubramaniam Senduran, Chen Yuan, Colonna Vincenza, Danecek Petr, Jostins Luke, Keane Thomas M., McCarthy Shane, Walter Klaudia, Xue Yali, Gerstein Mark B., Abyzov Alexej, Balasubramanian Suganthi, Chen Jieming, Clarke Declan, Fu Yao, Harmanci Arif O., Jin Mike, Lee Donghoon, Liu Jeremy, Jasmine Mu Xinmeng, Zhang Jing, Zhang Yan, Li Yingrui, Luo Ruibang, Zhu Hongmei, Alkan Can, Dal Elif, Kahveci Fatma, Marth Gabor T., Garrison Erik P., Kural Deniz, Lee Wan-Ping, Ward Alistair N., Wu Jiantao, Zhang Mengyao, McCarroll Steven A., Handsaker Robert E., Altshuler David M., Banks Eric, del Angel Guillermo, Genovese Giulio, Hartl Chris, Li Heng, Kashin Seva, Nemesh James C., Shakir Khalid, Yoon Seungtai C., Lihm Jayon, Makarov Vladimir, Degenhardt Jeremiah, Korbel Jan O., Fritz Markus H., Meiers Sascha, Raeder Benjamin, Rausch Tobias, Stütz Adrian M., Flicek Paul, Paolo Casale Francesco, Clarke Laura, Smith Richard E., Stegle Oliver, Zheng-Bradley Xiangqun, Bentley David R., Barnes Bret, Keira Cheetham R., Eberle Michael, Humphray Sean, Kahn Scott, Murray Lisa, Shaw Richard, Lameijer Eric-Wubbo, Batzer Mark A., Konkel Miriam K., Walker Jerilyn A., Ding Li, Hall Ira, Ye Kai, Lacroute Phil, Lee Charles, Cerveira Eliza, Malhotra Ankit, Hwang Jaeho, Plewczynski Dariusz, Radew Kamen, Romanovitch Mallory, Zhang Chengsheng, Craig David W., Homer Nils, Church Deanna, Xiao Chunlin, Sebat Jonathan, Antaki Danny, Bafna Vineet, Michaelson Jacob, Ye Kenny, Devine Scott E., Gardner Eugene J., Abecasis Gonçalo R., Kidd Jeffrey M., Mills Ryan E., Dayama Gargi, Emery Sarah, Jun Goo, Shi Xinghua, Quitadamo Andrew, Lunter Gerton, McVean Gil A., Chen Ken, Fan Xian, Chong Zechen, Chen Tenghui, Witherspoon David, Xing Jinchuan, Eichler Evan E., Chaisson Mark J., Hormozdiari Fereydoun, Huddleston John, Malig Maika, Nelson Bradley J., Sudmant Peter H., Parrish Nicholas F., Khurana Ekta, Hurles Matthew E., Blackburne Ben, Lindsay Sarah J., Ning Zemin, Walter Klaudia, Zhang Yujun, Gerstein Mark B., Abyzov Alexej, Chen Jieming, Clarke Declan, Lam Hugo, Jasmine Mu Xinmeng, Sisu Cristina, Zhang Jing, Zhang Yan, Gibbs Richard A., Yu Fuli, Bainbridge Matthew, Challis Danny, Evani Uday S., Kovar Christie, Lu James, Muzny Donna, Nagaswamy Uma, Reid Jeffrey G., Sabo Aniko, Yu Jin, Guo Xiaosen, Li Wangshen, Li Yingrui, Wu Renhua, Marth Gabor T., Garrison Erik P., Fung Leong Wen, Ward Alistair N., del Angel Guillermo, DePristo Mark A., Gabriel Stacey B., Gupta Namrata, Hartl Chris, Poplin Ryan E., Clark Andrew G., Rodriguez-Flores Juan L., Flicek Paul, Clarke Laura, Smith Richard E., Zheng-Bradley Xiangqun, MacArthur Daniel G., Mardis Elaine R., Fulton Robert, Koboldt Daniel C., Gravel Simon, Bustamante Carlos D., Craig David W., Christoforides Alexis, Homer Nils, Izatt Tyler, Sherry Stephen T., Xiao Chunlin, Dermitzakis Emmanouil T., Abecasis Gonçalo R., Min Kang Hyun, McVean Gil A., Gerstein Mark B., Balasubramanian Suganthi, Habegger Lukas, Yu Haiyuan, Flicek Paul, Clarke Laura, Cunningham Fiona, Dunham Ian, Zerbino Daniel, Zheng-Bradley Xiangqun, Lage Kasper, Berg Jespersen Jakob, Horn Heiko, Montgomery Stephen B., DeGorter Marianne K., Khurana Ekta, Tyler-Smith Chris, Chen Yuan, Colonna Vincenza, Xue Yali, Gerstein Mark B., Balasubramanian Suganthi, Fu Yao, Kim Donghoon, Auton Adam, Marcketta Anthony, Desalle Rob, Narechania Apurva, Wilson Sayres Melissa A., Garrison Erik P., Handsaker Robert E., Kashin Seva, McCarroll Steven A., Rodriguez-Flores Juan L., Flicek Paul, Clarke Laura, Zheng-Bradley Xiangqun, Erlich Yaniv, Gymrek Melissa, Frederick Willems Thomas, Bustamante Carlos D., Mendez Fernando L., David Poznik G., Underhill Peter A., Lee Charles, Cerveira Eliza, Malhotra Ankit, Romanovitch Mallory, Zhang Chengsheng, Abecasis Gonçalo R., Coin Lachlan, Shao Haojing, Mittelman David, Tyler-Smith Chris, Ayub Qasim, Banerjee Ruby, Cerezo Maria, Chen Yuan, Fitzgerald Thomas W., Louzada Sandra, Massaia Andrea, McCarthy Shane, Ritchie Graham R., Xue Yali, Yang Fengtang, Gibbs Richard A., Kovar Christie, Kalra Divya, Hale Walker, Muzny Donna, Reid Jeffrey G., Wang Jun, Dan Xu, Guo Xiaosen, Li Guoqing, Li Yingrui, Ye Chen, Zheng Xiaole, Altshuler David M., Flicek Paul, Clarke Laura, Zheng-Bradley Xiangqun, Bentley David R., Cox Anthony, Humphray Sean, Kahn Scott, Sudbrak Ralf, Albrecht Marcus W., Lienhard Matthias, Larson David, Craig David W., Izatt Tyler, Kurdoglu Ahmet A., Sherry Stephen T., Xiao Chunlin, Haussler David, Abecasis Gonçalo R., McVean Gil A., Durbin Richard M., Balasubramaniam Senduran, Keane Thomas M., McCarthy Shane, Stalker James, Bodmer Walter, Bedoya Gabriel, Ruiz-Linares Andres, Cai Zhiming, Gao Yang, Chu Jiayou, Peltonen Leena, Garcia-Montero Andres, Orfao Alberto, Dutil Julie, Martinez-Cruzado Juan C., Oleksyk Taras K., Barnes Kathleen C., Mathias Rasika A., Hennis Anselm, Watson Harold, McKenzie Colin, Qadri Firdausi, LaRocque Regina, Sabeti Pardis C., Zhu Jiayong, Deng Xiaoyan, Sabeti Pardis C., Asogun Danny, Folarin Onikepe, Happi Christian, Omoniwa Omonwunmi, Stremlau Matt, Tariyal Ridhi, Jallow Muminatou, Sisay Joof Fatoumatta, Corrah Tumani, Rockett Kirk, Kwiatkowski Dominic, Kooner Jaspal, Tịnh Hiê`n Trâ`n, Dunstan Sarah J., Thuy Hang Nguyen, Fonnie Richard, Garry Robert, Kanneh Lansana, Moses Lina, Sabeti Pardis C., Schieffelin John, Grant Donald S., Gallo Carla, Poletti Giovanni, Saleheen Danish, Rasheed Asif. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature. 2015;526(7571):68–74. doi: 10.1038/nature15393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sanders SJ, et al. De novo mutations revealed by whole-exome sequencing are strongly associated with autism. Nature. 2012;485:237–241. doi: 10.1038/nature10945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lek Monkol, Karczewski Konrad J., Minikel Eric V., Samocha Kaitlin E., Banks Eric, Fennell Timothy, O’Donnell-Luria Anne H., Ware James S., Hill Andrew J., Cummings Beryl B., Tukiainen Taru, Birnbaum Daniel P., Kosmicki Jack A., Duncan Laramie E., Estrada Karol, Zhao Fengmei, Zou James, Pierce-Hoffman Emma, Berghout Joanne, Cooper David N., Deflaux Nicole, DePristo Mark, Do Ron, Flannick Jason, Fromer Menachem, Gauthier Laura, Goldstein Jackie, Gupta Namrata, Howrigan Daniel, Kiezun Adam, Kurki Mitja I., Moonshine Ami Levy, Natarajan Pradeep, Orozco Lorena, Peloso Gina M., Poplin Ryan, Rivas Manuel A., Ruano-Rubio Valentin, Rose Samuel A., Ruderfer Douglas M., Shakir Khalid, Stenson Peter D., Stevens Christine, Thomas Brett P., Tiao Grace, Tusie-Luna Maria T., Weisburd Ben, Won Hong-Hee, Yu Dongmei, Altshuler David M., Ardissino Diego, Boehnke Michael, Danesh John, Donnelly Stacey, Elosua Roberto, Florez Jose C., Gabriel Stacey B., Getz Gad, Glatt Stephen J., Hultman Christina M., Kathiresan Sekar, Laakso Markku, McCarroll Steven, McCarthy Mark I., McGovern Dermot, McPherson Ruth, Neale Benjamin M., Palotie Aarno, Purcell Shaun M., Saleheen Danish, Scharf Jeremiah M., Sklar Pamela, Sullivan Patrick F., Tuomilehto Jaakko, Tsuang Ming T., Watkins Hugh C., Wilson James G., Daly Mark J., MacArthur Daniel G. Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature. 2016;536(7616):285–291. doi: 10.1038/nature19057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Purcell S, et al. PLINK: A Tool Set for Whole-Genome Association and Population-Based Linkage Analyses. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wei Q, et al. A Bayesian framework for de novo mutation calling in parents-offspring trios. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 2015;31:1375–1381. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dong C, et al. Comparison and integration of deleteriousness prediction methods for nonsynonymous SNVs in whole exome sequencing studies. Human molecular genetics. 2015;24:2125–2137. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Robinson JT, et al. Integrative genomics viewer. Nature biotechnology. 2011;29:24–26. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kent W. J. BLAT---The BLAST-Like Alignment Tool. Genome Research. 2002;12(4):656–664. doi: 10.1101/gr.229202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.