Abstract

Rumen is one of the most complex gastro-intestinal system in ruminating animals. With bountiful of microorganisms supporting in breakdown and consumption of minerals and nutrients from the complex plant biomass. It is predicted that a table spoon of ruminal fluid can reside up to 150 billion microorganisms including various species of bacteria, fungi and protozoa. Several studies in the past have extensively explained about the structural and functional physiology of the rumen. Studies based on rumen and its microbiota has increased significantly in the last decade to understand and reveal applications of the rumen microbiota in food processing, pharmaceutical, biofuel and biorefining industries. Recent high-throughput meta-genomic and proteomic studies have revealed humongous information on rumen microbial diversity. In this study, we have extensively reviewed and reported present-day's progress in understanding the rumen microbial diversity. As of today, NCBI resides about 821,870 records based on rumen with approximately 889 genome sequencing studies. We have retrieved all the rumen-based records from NCBI and extensively catalogued the rumen microbial diversity and the corresponding genomic and proteomic studies respectively. Also, we have provided a brief inventory of metadata analysis software packages and reviewed the metadata analysis approaches for understanding the functional involvement of these microorganisms. Knowing and understanding the present progress on rumen microbiota and performing metadata analysis studies will significantly benefit the researchers in identifying the molecular mechanisms involved in plant biomass degradation. These studies are also necessary for developing highly efficient microorganisms and enzyme mixtures for enhancing the benefits of cattle-feedstock and biofuel industries.

Keywords: Ruminating animals, Ruminal fluid, Microbiota, Genomic, Proteomic, Bacteria, Fungi, Protozoa.

1.0 Introduction

Ruminating animals feed on plant biomass for their complete nutrition. However, they do not secrete any cellulolytic or hemicellulolytic enzymes to breakdown the plant cell wall polysaccharides 1, 2. Thus, ruminating animals are solely dependent on the rumen microbiota to enzymatically breakdown and ferment plant biomass for food and energy. Ruminating animals have a four-chambered stomach containing the following sections: (a) reticulum, (b) rumen, (c) omasum and (d) abomasum 1-3. The reticulum and rumen are together considered as stomach of the ruminating animals and most part of the digestion occurs in the stomach 1-3. The reticulum also called as blind pouch is the largest and first compartment of the ruminating animals' gut. The reticulum can hold up to 2.5 gallons of digested or undigested feed. It acts as a sieve when ruminating animals consumes indigestible materials like metal, plastic, etc. The honeycomb structure of the stomach wall stops their movement further into the digestive tract. The most significant feature of ruminating animals is their ability to regurgitate the feed, and this function happens to the feed which enters the reticulum 1-4.

The rumen is a hollow muscular organ of the gut, which grows large anatomically with the changing diet of a calf from milk to grass. Also, the microbial diversity of the rumen grows with the changing diets of a developing calf. In a fully grown ruminating animal, the rumen occupies the complete left section of the gut chamber 5, 6. It is solely a fermentation chamber and it can contain up to 40-60 gallons of undigested food. Studies have proposed that a table spoon of ruminal fluid can contain 150 billion microorganisms including various species of bacteria, fungi, protozoa 3, 6, 7. The rumen is well-suited for maintaining the growth of bacteria because it is an oxygen free environment with a pH between 5.8 to 6.4 and a temperature ranging between 100oF (37oC) to 108oF (42oC). A normal diet including portion of grains and forages should exhibit the above-mentioned pH range, which supports the growth of several bacterial strains in the rumen microbiota 5, 6, 8.

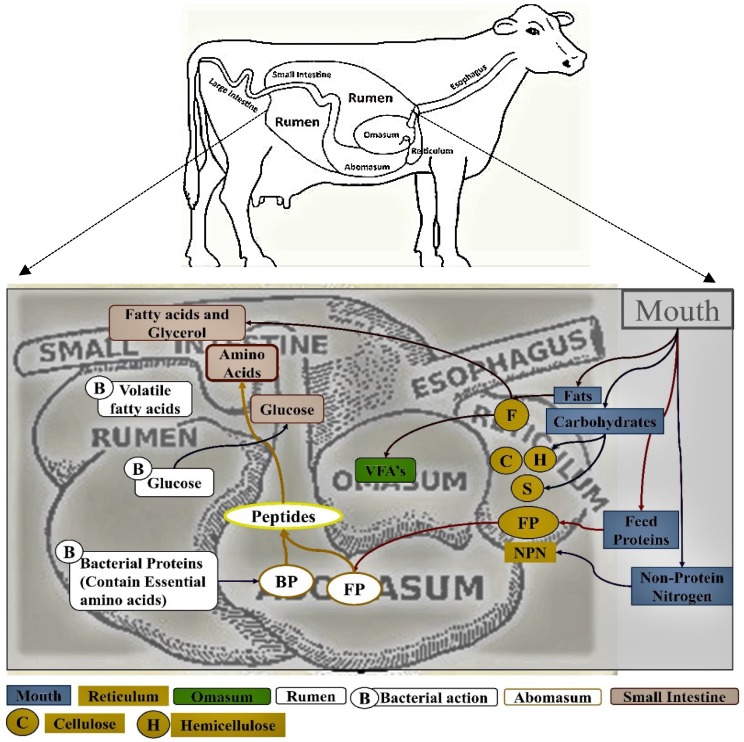

The omasum, also called many plies due to its multi-layered muscular tissue, holds up to 4 gallons of the digesta 9. This chamber removes the excess water from the digesta and reduces its particles size before it enters the abomasum 10-12. The abomasum is the fourth and final true glandular compartment of the gut and it is considered as the true stomach of the ruminating animals' gut as it secretes several digesting enzymes 5, 6, 13, 14. It can contain up to 5 gallons of feed material, but the digesta remains for a lesser period in the abomasum when compared to that of rumen. The presence of food in the abomasum stimulates the production of hydrochloric acid and this converts pepsinogen to pepsin, which converts proteins to shorter peptides and aminoacids for the digestion and absorption into the small intestine 13, 15. The pH of the stomach is maintained between 2 to 4 because of the secretion of strong acids. The digested food and released nutrients pass from the abomasum to the small intestine and, as a result, the pH rises at a slow rate. This physiological rise in pH has its implications on the pancreas and intestinal mucosa as the enzymes released by it are only active at neutral or slight alkaline pH (Figure 1) 1, 5, 6, 11, 16.

Figure 1.

Pictorial representation of rumen and the process of digestion and absorption of the food material in ruminating animals [Note: The boxes are colored to represent the food passage from mouth to the rumen].

The bile salts produced in the liver helps maintaining the alkaline pH of the small intestine 17, 18. These bile salts separate the fat globules and provide the lipase enzymes more surface area to act on. The bile and pancreatic secretions maintain the neutral pH of the gastric juice, providing the optimum conditions for enzymes to hydrolyze starch, proteins and lipids. The small intestine is the major absorption site for the nutrients obtained from the metabolism 19. When ruminants are fed with high forage diets, most of the starch and soluble sugars are fermented by the microbial community of the rumen. However, when ruminants are fed with higher amounts of grain diets, about 50 percent of the dietary starch escape from the rumen to the lower gastrointestinal tract where it is digested. Thus, substantial amounts of glucose and other monosaccharides are absorbed by the small intestine 19, 20. The proteins absorbed by the small intestine are derived from three sources, which can be classified as (a) dietary proteins (escaped from the microbial fermentation in the rumen), (b) microbial proteins present in the cells and (c) endogenous proteins (sloughed cells and secretions of abomasum and intestine). These proteins are further digested to small peptides and aminoacids by the pancreatic and intestinal proteases, which are absorbed by the small intestine as well 21. The lipids reaching the small intestine are majorly esterified fatty acids and phospholipids. Pancreatic lipases readily hydrolyze the esterified fatty acids produced by microbes and triglycerides escaped from the ruminal microorganisms. Thus, the released free fatty acids are easily absorbed by the mucosal cells of the small intestine 5, 16, 17, 19 (Figure 2).

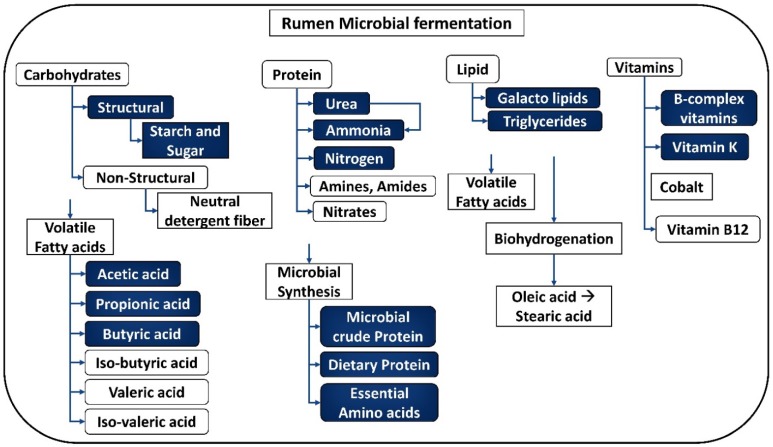

Figure 2.

Breakdown products obtained from the process of fermentation by rumen microbiota. [Note: The uncolored boxes are the macromolecules and the blue colored boxes represent the products of metabolism].

The feed that escapes from the above-mentioned digestion process enters the large intestine, where water, minerals, nitrogen and volatile fatty acids are absorbed 16. The major functions of the large intestine include (a) balancing electrolytes, (b) perform microbial fermentation and (c) provide a temporary storage of excreta. Any undigested feed obtained from the gastrointestinal tract will be passed out in the feces. Usually the fecal matter contains undigested feed, metabolic nitrogen, undigested fat and some microorganisms 5.

1.1 Rumination

Rumination significantly supports the process of digestion. The processes involved during rumination are (a) the regurgitation of food and (b) the rechewing, re-salivation and re-swallowing of the ingested food material 8, 10, 22. The rumination process reduces the particle size of the ingested food, which significantly enhances microbial fermentation and aids in easy passage by the stomach compartments. Rechewing or ruminating strongly induces the process of salivation. A mature ruminant produces 47.5 gallons of saliva per day if it chews the feed for 6 to 8 hours 1, 23-25. Thus, secretion of saliva is directly proportional to the amount of time a cow spends in chewing or ruminating the bolus or cud. The saliva of ruminating animals highly comprises of sodium (126 mEq/L), phosphate (26 mEq/L), bicarbonate (126 mEq/L) and lesser amounts of potassium (6 mEq/L) and chloride (7 mEq/L) ions which act as buffering agents in the digestive system 1, 24, 26. It aids in the maintenance of the neutral environment by neutralizing the acids released during fermentation. The type of feed ingested also plays a crucial role in the stimulation of salivation. Dried feeds such as hay and grass stimulate higher rates of salivation and other feeds such as silage, fresh grass and pelleted materials result in lesser stimulation of saliva. It was also reported that rate of saliva production is significantly reduced if the ruminants are not fed with adequate amounts of effective fiber and high moisture containing feeds 8, 10, 22.

1.2 Functional Physiology of Rumen

The rumen is a muscular organ which performs the mixing and churning of the digesta 1. The rumen constantly stirs the digesta to enhance the accessibility of coarser feed particles during the process of regurgitation and bolus chewing, thus reducing the particle size of feed and enhancing its fermentation 27. Smaller feed particles digested by the rumen are collected at the bottom and eventually pass out of the rumen along with the microbial strains to aid digestion in the lower gastrointestinal tract 5, 28. The composition of the ruminal contents is completely dependent on the type of food materials that are ingested. Generally, ruminants consume different types of food. Thus, contents of the rumen are not uniform among ruminants. Since the rumen is a fermentation chamber, gases such as hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, methane and carbon dioxide are produced during microbial fermentation 1. The descending order of gases released in the rumen are carbon dioxide (65.5%), methane (26.8%), nitrogen (7.0%), oxygen (0.5%) and hydrogen (0.2%) 1, 29. The released gases get accumulated in the upper part of the rumen with higher percentages of carbon dioxide and methane.

The composition of these gases is again dependent on the ecology and fermentation rates of the rumen; usually, the proportion of carbon dioxide is 2-3 times higher than that of methane 7, 28. However, a large proportion of carbon dioxide is in turn reduced to methane. On average, about 132 to 264 gallons of these gases are produced by the process of fermentation, which are belched frequently by the ruminants to avoid bloating 5. Rumen mucosal linings consists of ruminal papillae (organs for absorption) and their size and distribution are directly related to the type of food material they ingest. The diet of ruminating animals varies significantly from high forage diet to a high grain diet. Changes in diet must be implemented gradually to permit the adaptation of papillae to changes in nutrition, which may take approximately 2 to 3 weeks 30. The ruminal papillae are also related to the production acids from the fermentation of feeds. Thus, the size, number and distribution of the ruminal papillae depends on the diet and acids released during fermentation 31.

1.3 Microbiology of Rumen

Ruminating animals are very rich in microorganisms. Studies have reported that a milliliter of rumen contains approximately 105 to 106 protozoans and about 1010 to 1011 of bacterial inhabitants 1-3, 7. The protozoans inhabiting ruminal fluids can be majorly divided into two ciliate groups: (a) holotrichs and (b) entodinimorphs 32. The bacterial population present in ruminal fluids are classified into cocci, rods and spirilla based on their size and shape 16, 25. The ruminal bacteria can also be classified based on their substrate fermenting abilities into eight different groups that are able to consume cellulose, hemicelluloses, starch, simple sugars, pectin, proteins, lipids and intermediate acids. The ruminal bacteria are also majorly known for their ability to produce methane 1, 32, 33. Most of the ruminal bacteria are capable of degrading and fermenting multiple substrates. Compared to other ruminal microorganisms, methane producing bacteria are the most important and special bacteria that regulate the process of fermentation and its products in the rumen 34. Methanogens aid in removing hydrogen gas by forming methane and reducing carbon dioxide, thus maintaining the lower concentrations of hydrogen in the rumen and supporting the growth and development of several other bacterial strains 33, 35.

Apart from bacteria, protozoa are highly observed in the ruminal fluid when the ruminants are fed with higher digestibility feed 33, 35. Thus, different diets of the ruminants encourage the growth of different protozoan populations. Diets richer in starch and soluble sugars promote higher growth rates of different protozoan populations. Protozoans are important in neutralizing the rumen environment by stabilizing the end products of fermentation 36. Recent studies have reported on the occurrence of anaerobic fungi in the ruminal fluids of ruminants. Especially, the fungal divisions Chytridiomycota and Neocallimastigomycota were found to contain anaerobic fungi which are also majorly observed in the rumens of the ruminating animals 36, 37. Studies have reported that anaerobic fungi contribute up to 8% of the microbial mass in the rumen. The anaerobic fungi were proposed to play a significant role in degradation of plant biomass containing cellulose and xylans. However, further studies are still needed to demonstrate the role of anaerobic fungi in the rumen metabolism 36, 38-40.

Physiologically, the rumen comprises three connecting environments, one liquid (free living microorganisms in the rumen liquid breakdown and feed on carbohydrates and protein) and another solid (microorganisms attached to the ingested food particles and to the rumen epithelium or protozoa) 1, 5. Liquid and solid phase microorganisms constitute up to 70% of the rumen microbiota and up to 5% of microorganisms associated with the rumen epithelium 41. To maintain their population, it is important for the bacteria to have a reproduction time shorter than the turnover of the rumen digesta. However, bacteria with slower reproduction rates tend to attach to the particulate matter and start degrading it, without being flushed out of the body in the liquid stream 1, 33. Majorly, two factors strongly influence the bacterial population in the rumen: (a) the type of food material they ingest and (b) the rumen pH 3, 22. It is highly important to consider the reproduction rates of microorganisms when shifting the diet of ruminants, as changing diet also requires a change in shift of microbial population in the rumen. Microbial shift of the rumen is a time taking process and it requires several days. For instance, when ruminants are fed with simple carbohydrates (easily fermentable), such feeding habit encourages the growth of bacteria with lactate utilizing and producing abilities; hence, acid-sensitive lactate utilizing bacteria are gradually replaced by acid-tolerant lactate utilizing bacteria 25, 29, 33, 42.

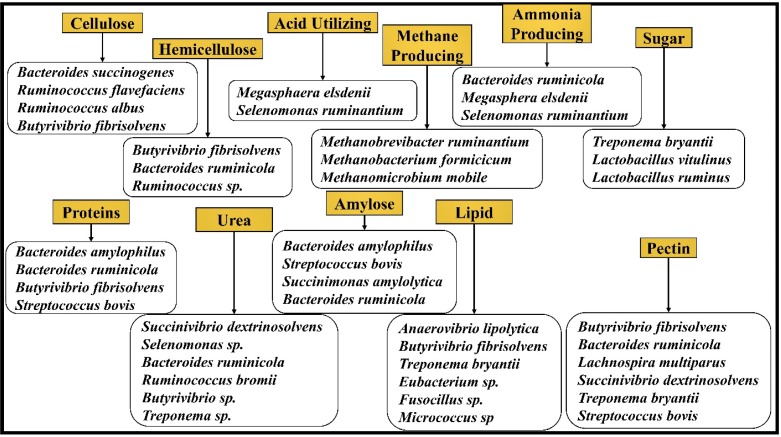

It is highly necessary to maintain ideal pH conditions for sustaining the microbiota of the rumen. Majorly, bacteria can be classified on the basis of their activity in the rumen as fiber digestors (active at pH 6.2 to 6.8) and starch digestors (active at pH 5.2 to 6.0) 16. Studies have also reported that the population of cellulolytic and methanogenic bacteria drops if the rumen pH drops below 6.0 and few species of protozoa were also found to drop if the rumen pH is under 5.5. Several studies have reported on the major bacterial strains involved in the metabolism of plant biomass components in ruminating animals (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The major microorganism species reported in the previous studies and classified based on the substrates they degrade.

2.0 Metadata Analysis (or) Systematic Review Based Methods

The metadata analysis and systematic review are two statistical approaches for re-analyzing the data by combining the information from various datasets and identifying the common effect behind the effect size or treatment effect respectively. Metadata analysis (or) systematic review is mainly used for understanding and identifying the reason responsible for the variations in the effect size between one study to another study respectively. The valuable information reported in previous literature, and the resourceful supplementary information are major sources for the systematic reviews and metadata analysis approaches. There are various advantages of metadata analysis approaches such as: a) It plays a significantly role in designing and executing new studies, b) metadata analysis helps in identifying the questions which are already reported, and it can help the studies to focus on the answered questions of the research. In our present study, we have conducted an extensive systematic review reporting all the previously reported literature related to the “rumen” and “rumen microbiota”, which can be further used by the data scientists and researchers to identify the microorganisms supporting the metabolism of lignocellulosic plant biomass in cattle.

2.1 Literature Related to Rumen

Understanding the structural and functional physiology of the rumen and its diverse microbiota are subject of study since several years. Understanding the characteristic features of rumen has various potential benefits such as (a) increase the rate of breakdown of ingested feed, (b) increase the rate of absorption of nutrients and minerals by ruminants and (c) diversify the countless commercial applications of rumen microbiota in the food, pharmaceutical, textile, biofuel and bioremediation industries. The NCBI database is an online public repository for biological and life science data. The NCBI database resides and classifies the data among 37 NCBI databases (Table 1). The search with the term “Rumen” has resulted in the data distributed among the 27 databases respectively, with zero records from the NCBI Genetics database.

Table 1.

The NCBI public repository and its major classification of NCBI databases.

| NCBI Literature | Bookshelf, MeSH, NLM Catalog, PubMed and PubMed Central |

|---|---|

| NCBI Genes | Gene, GEO Database, GEO Profiles, HomoloGene, PopSet UniGene |

| NCBI Genetics | ClinVar, dbGap, dbSNP, dbVar, GTR, MedGen, OMIM |

| NCBI Genomes | Assembly, BioCollections, BioProject, BioSample, Genome, Nucleotide, Probe, SRA, Taxonomy |

| NCBI Proteins | Conserved Domains, Identical Protein Groups, Proteins, Protein Clusters, Sparcle, Structure |

| NCBI Chemicals | Biosystems, PubChem BioAssay, PubChem Compound, PubChem Substance |

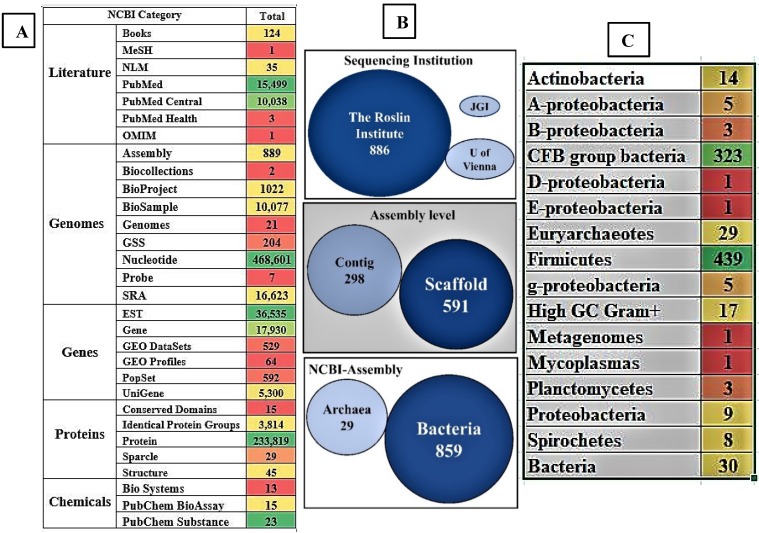

Several research communities around the world have contributed significantly to the current knowledge on the structural and functional physiology of the rumen. We have retrieved and reported the total number of 821,870 recorded datasets on “rumen” till date, classified among different NCBI databases. The 821,870 articles of NCBI can be classified under sections of literature-25,701, genome-4,97,446, genes-60,950, proteins-2,37,722 and chemicals-51 of the reported articles among these databases respectively. Till date in NCBI literature section there are 25,701 reported articles which includes 124 books, 15,449 Pubmed articles, 10,038 Pubmed central articles, 3 Pubmed health, 1 medical subject headings, 1 online mendelian inheritance in man and 35 national library of medicine articles respectively (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

Pictorial representation of the present days collection a) the number of records and datasets in NCBI database based on the term “Rumen”, b) briefly lists details of the genomic and metagenomic sequencing studies i) sequencing institution, ii) level of assembly and iii) the classification of assembled genomes into archaea and bacteria groups and c) shows the division of assembled genomes of microorganisms at genus level (A, B, D, E and G - proteobacteria represents α, β, δ, γ, £- proteobacteria). [Note: The color gradient used for the images A and B were generated using Microsoft Excel with red color represents lowest count, green color represents highest count and yellow color represents for intermediate count. Especially for figure 4A was gradient colored based for each section separately].

2.2 Metagenomic, Genomic, Proteomic Studies on Rumen and Its Microbiota

In the past, numerous studies were conducted to understand the microbial diversity of the rumen and its fermenting abilities by employing conventional isolation techniques and biochemical characterization methods 32, 43-46. These microorganisms were characterized majorly by their fiber digestion and protein assimilation abilities 32. Using these targeted screening approaches, several rumen microorganisms were reported in the past, including bacterial, fungal and protozoan species 44, 47. Over time, the conventional standard phylogenetic analysis based on 16s RNA 47-50 and 18s RNA 50-52 functional gene classification methods were applied. However, these techniques are very limited, and they only provide the functional relatedness of the targeted species to the already defined and studied phenotypes. Development of advanced molecular techniques especially high throughput sequencing has replaced these conventional methods with the whole genome and metagenome sequencing methods 53-63. Recent developments in the field of genome sequencing revealed important facts about living organisms and the molecular mechanisms underlying the cellular processes 64-66. In the last few years, whole genome sequences of several commercially important bacterial and fungal species have been revealed. In 2013, the first whole genome sequence of rumen bacteria Wolinella succinogens was revealed and after that several other rumen bacterial and fungal genomes have been released 67.

More recently, several studies have been conducted to understand and reveal the complete genomic sequences of various rumen microorganisms. Simultaneously, public data repositories such as DOE-Joint Genome Institute (https://jgi.doe.gov/) 68, 69 and Hungate 1000 (aimed to sequence 1000 rumen microbial strains including rumen bacteria, methanogenic bacteria, fungi, archaea and ciliate protozoans - http://www.rmgnetwork.org/hungate1000.html) were made available 70. The Hungate research project has 410 whole genome sequences of microorganisms present in the rumen of cattle. This project involves 60 laboratories from 14 research organizations situated across 9 countries. The collection of whole genome sequence information of these 410 rumen microorganisms can be retrieved from the DOE-Joint genome institute portal https://genome.jgi.doe.gov/portal/HungateCollection/HungateCollection.info.html 70.

Currently, the NCBI-Assembly harbors 889 whole genome sequences or clone-based assembly sequences of rumen microorganisms and rumen metagenome, respectively. We have retrieved all the summary data from the NCBI-Assembly and separated the data based on the organism, submitter and assembly level. Out of these, 859 are bacterial genomes and 29 are archaeal genomes. Based on the assembly level these sequenced genomes can be separated into 591 scaffold level and 298 contig level. Most number of genomes were submitted by the Roslin Institute (886 genomes), 2 genomes came from the University of Vienna and 1 genome from the DOE-Joint Genome Institute (Figure 4B). The 859 sequenced rumen bacterial genomes can be majorly separated into 439 firmicutes, 323 CFB (Cytophaga-Flavobacterium-Bacteroides) group bacteria, 17 high GC gram positive and 14 actinobacteria (Figure 4C). Among the 889 sequenced rumen microorganisms only 9 bacterial strains are cultured and 879 were uncultured strains. Interestingly, among the 879 uncultured strains, 434 were firmicutes (276 Clostridiales, 74 Lachnospiraceae, 28 Erysipelotrichaceae, 15 Selenomonadales, and 10 Ruminococcus) and 323 were CFB group bacteria (135 Prevotellaceae, 121 Bacteroidales and 67 Prevotella).

Recent next generation sequencing methods especially large-scale metagenome sequencing techniques has enabled the identification of microbial communities inhabiting the complex environments such as rumen (Figure 4C, Table 2). However, the metagenome sequencing techniques skips various traditional identification methods such as isolation, culturing and characterization of microorganisms. Thus, majority of the bacterial strains reported from the NCBI database are reported as uncultured strains respectively.

Table 2.

List of the cultured and uncultured NCBI assembled genomes of the rumen isolated microorganisms retrieved from NCBI Assembly Database.

| NCBI Assembled genomes of Microorganisms retrieved from Rumen |

|---|

|

Acidaminococcus fermentans, Bacillus licheniformis, Kandleria vitulina, Megasphaera sp. DJF_B143, Streptococcus equinus Uncultured Firmicutes: Acidaminococcus sp., Clostridia bacterium, Clostridiales bacterium, Dialister sp., Erysipelotrichaceae bacterium, Eubacterium sp., Firmicutes bacterium, Lachnospiraceae bacterium, Negativicutes bacterium, Ruminococcus sp., Selenomonadales bacterium, Sharpea sp., Streptococcus sp., Veillonellaceae bacterium |

| Uncultured actinobacteria: Olsenella species |

| Uncultured α-Proteobacteria: Rhodospirillaceae bacterium |

| Uncultured Bacteria: Brachyspira sp., Elusimicrobia bacterium, Elusimicrobium sp., Fibrobacter sp., Lentisphaerae bacterium |

| Uncultured β-Proteobacteria: Sutterella sp. |

| Uncultured CFB group bacteria: Bacteroidales bacterium, Prevotella species, Prevotellaceae bacterium |

| Uncultured γ-Proteobacteria: Desulfovibrio species |

| Uncultured ε-Proteobacteria: Campylobacter species |

|

Methanomassiliicoccales archaeon M1 and M2 strain Uncultured Euryarchaeotes: Candidatus Methanomethylophilus species, Methanobrevibacter species, Methanosphaera species |

| Uncultured δ-Proteobacteria: Acinetobacter species, gamma proteobacterium, Succinatimonas species, |

| Bifidobacterium merycicum, Uncultured high GC gram+: Actinobacterium species, Bifidobacterium species |

| Mycoplasmas: Mycoplasmataceae bacterium |

| Planctomycetes: Planctomycete species |

| Spirochetes: Spirochaetaceae bacterium, Treponema species |

Earlier studies have reported that rumen bacteria predominantly include gram negative cellulolytic bacteria such as Fibrobacter succinogenes, Ruminococcus flavifaciens, Megasphaera elsdenii, Selenomonas ruminantium, Veillonella parvula, Butyrivibrio fibrisolvens Lactobacillus ruminis respectively. According to Jewell, K. A, et al (2015), rumen microbiota of cow's rumen majorly composed of Bacteroidetes- 49.42%, Firmicutes-39.32%, Proteobacteria-5.67%, and Tenericutes-2.17% respectively 71. This study has also reported that the abundant genera of cow's rumen includes Prevotella (40.15%), Butyrivibrio (2.38%), Ruminococcus (2.35%), Coprococcus (2.29%), and Succiniclasticum (2.28%) genera respectively 71.

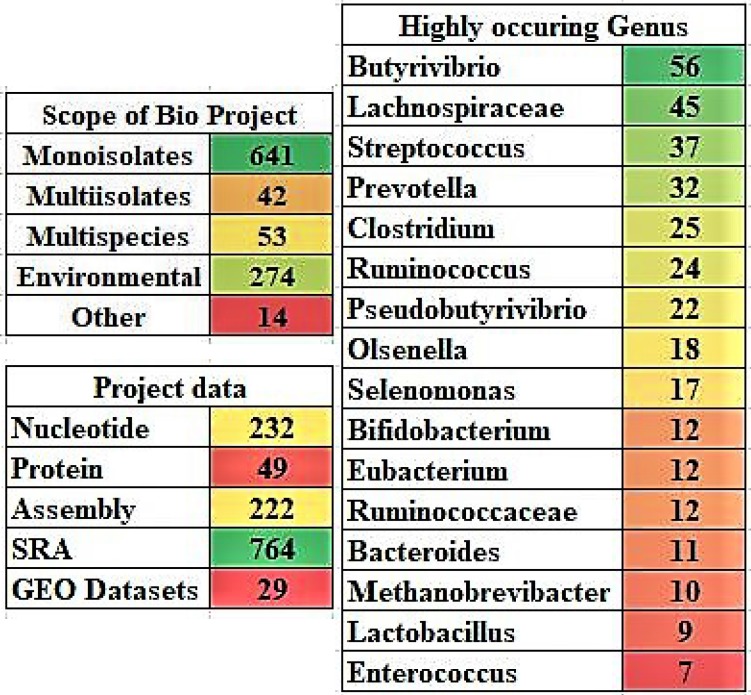

The NCBI search with the term “Rumen” has resulted in a total of 1,026 records were listed under the NCBI BioProjects section, out of which 641 records are mono-isolates, 53 records are multi-species, 42 are multi-isolates, 274 are environmental samples and 14 are other reports. Based on the type of project, these data can be further classified into 232 nucleotide, 49 protein, 222 assembly, 764 SRA (sequence read archive) and 29 gene expression omnibus datasets (GEO). Among the 641 mono-isolate cultures, the following genuses were highly observed: Butyrivibrio, Lachnospiraceae, Streptococcus, Prevotella, Clostridium, Ruminococcus, Pseudobutyrivibrio, Olsenella, Selenomonas, Bifidobacterium, Eubacterium, Ruminococcaceae, Bacteroides, Methanobrevibacter, Lactobacillus and Enterococcus (Figure 5). The systematic review of the NCBI Genomes databases reported in this study adds up to the present days knowledge on rumen microbial communities.

Figure 5.

The project data details of rumen microorganisms and the highly occurring genus in the rumen isolates. [Note: The color gradient used for the images A and B were generated using Microsoft Excel with red color represents lowest count, green color represents highest count and yellow color represents for intermediate count].

The genome database of the NCBI harbors 21 genomes of the following bacteria: Treponema saccharophilum, Selenomonas ruminantium, Slackia heliotrinireducens, Butyrivibrio proteoclasticus, Wolinella succinogenes, Fibrobacter succinogenes, Lachnospiraceae bacterium, Desulfotomaculum ruminis, Ruminococcus champanellensis, Ruminococcus bromii, Butyrivibrio fibrisolvens, Oxalobacter formigenes, Holdemanella biformis, Lactobacillus ruminis, Eubacterium saphenum, Eubacterium rectale, Prevotella ruminicola, Sagittula stellata, Actinobacillus succinogenes, Eubacterium eligens and Ruminococcus albus (Table 3). The genome survey sequences (GSS) are similar to the expression sequence tags (EST) but GSS nucleotide sequences are of genomic origin, whereas EST nucleotide sequences are of mRNA origin. As of today, there are 204 rumen nucleotide sequences of GSS origin, out of which 81 (GSS: HHX01H12) are sequences from rumen metagenome from uncultured organisms, 50 sequences belong to Orpinomyces sp. OUS1, 64 sequences belong to bovine rumen metagenome, 3 sequences belong to Gastrothylax crumenifer and 6 sequences belong to Paramphistomum cervi.

Table 3.

Lists the details of ruminal bacteria with whole genome sequences, available from the genome database of NCBI.

| Name | Subgroup | Length (Mb) | Protein | GC% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treponema saccharophilum | Spirochaetia | 3.4539 | 2837 | 53.2% |

| Selenomonas ruminantium | Firmicutes | 3.1123 | 2805 | 50.1% |

| Slackia heliotrinireducens | Actinobacteria | 3.1650 | 2721 | 60.2% |

| Butyrivibrio proteoclasticus | Firmicutes | 4.0483 | 3504 | 40.149% |

| Wolinella succinogenes | δ/ε subdivision | 2.1103 | 2040 | 48.5% |

| Fibrobacter succinogenes | Fibrobacteres | 3.8428 | 3077 | 48.05% |

| Lachnospiraceae bacterium | Firmicutes | 2.9589 | 2446 | 54.3% |

| Desulfotomaculum ruminis | Firmicutes | 3.9690 | 3753 | 47.2% |

| Ruminococcus champanellensis | Firmicutes | 2.5424 | 2059 | 53.35% |

| Ruminococcus bromii | Firmicutes | 2.2760 | 2121 | 41% |

| Butyrivibrio fibrisolvens | Firmicutes | 4.6654 | 3764 | 39.7% |

| Oxalobacter formigenes | β-proteobacteria | 2.4528 | 2204 | 49.06% |

| Holdemanella biformis | Firmicutes | 2.5177 | 2261 | 34.4% |

| Lactobacillus ruminis | Firmicutes | 2.0249 | 1846 | 43.4% |

| Eubacterium saphenum | Firmicutes | 1.0849 | 919 | 40.6% |

| Eubacterium rectale | Firmicutes | 3.3450 | 2973 | 41.5% |

| Prevotella ruminicola | Bacteroidetes | 3.5894 | 2908 | 47.7% |

| Sagittula stellata | α-proteobacteria | 5.2628 | 4816 | 65% |

| Actinobacillus succinogenes | γ-proteobacteria | 2.3170 | 2104 | 44.9% |

| Eubacterium eligens | Firmicutes | 2.8313 | 2613 | 37.56% |

| Ruminococcus albus | Firmicutes | 3.8452 | 3661 | 44.5% |

The nucleotide database harbors a total of 468616 nucleotide sequences which can be majorly classified based on their source as gut metagenome (201684), uncultured bacterium (169318), uncultured rumen bacterium (18860), uncultured archaeon (16876), Clostridium beijerinckii (6121), uncultured prokaryote (6090), Ruminococcus flavefaciens (2582), uncultured rumen protozoa (1975), Acinetobacter baumannii (1929), uncultured organism (1418), uncultured methanogenic archaeon (1316), uncultured Prevotella sp. (1207), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (1180), uncultured rumen archaeon (1175), uncultured fungus (1067), Pseudochrobactrum sp. AO18b (1015), uncultured Methanobacteriaceae archaeon (962), Bacillus nealsonii (817), Lactococcus lactis (811), Synergistes jonesii (709) and all other taxa (31504), respectively. The sequence read archive (SRA) database currently contains 16,645 records which can be majorly classified into bovine gut metagenome (6558), gut metagenome (3901), stomach metagenome (1300), Bos taurus (1267), bovine metagenome (754), Ovis aries (331), metagenome (249), sheep gut metagenome (202), environmental samples (182), Bubalus bubalis (151), anaerobic digester metagenome (134), metagenomes (13419), uncultured prokaryote (90), feces metagenome (70), rumen bacterium 1/9293-11A (66), Bos indicus (58), firmicutes (405), fermentation metagenome (51), Capra hircus (43), synthetic metagenome (38) and all other taxa (1070), respectively.

The expressed sequence tags (EST) database holds a collection of short single-read transcripts from GenBank. These transcript sequences deliver the means for determining the gene expression, for finding the possible genetic variations and for annotating gene products. As of today there are 36,535 EST records in the NCBI EST database which can be classified as Bos taurus (32027), Entodinium caudatum (1061), Polyplastron multivesiculatum (624), Epidinium ecaudatum (594), Dasytricha ruminantium (587), Isotricha prostoma (542), Eudiplodinium maggii (542), Isotricha sp. BBF-2003 (276), Metadinium medium (151), Isotricha intestinalis (82), Entodinium simplex (27), Diploplastron affine (10), uncultured microorganism (6), Homo sapiens (4), Oryzias latipes (1) and Leucoraja erinacea (1), respectively.

The NCBI Gene database harbors and integrates a wide range of information about the gene sequences of a wide range of species. Currently, there are 17,937 records about the gene sequences of various rumen microorganisms, which can majorly be classified into Methanosarcina barkeri CM1 (3764), Methanobacterium formicicum (2420), Methanobrevibacter millerae (2318), Methanobrevibacter sp. YE315 (2146), Methanogenic archaeon ISO4-H5 (1868), Methanobrevibacter olleyae (1868), Methanobrevibacter sp. AbM4 (1737), Thermoplasmatales archaeon BRNA1 (1526), Calicophoron microbothrioides (36), Bos taurus (15), Streptomyces atroolivaceus (6), Escherichia coli (4), Streptomyces scabiei 87.22 (4), Streptomyces rimosus subsp. rimosus (4), Streptomyces canus (4), Streptomyces leeuwenhoekii (4), Streptomyces olivochromogenes (4), Ovis aries (3), Colletotrichum orchidophilum (3), Sphingobium yanoikuyae ATCC 51230 (3) and all other taxa (200), respectively.

The gene expression omnibus (GEO) is a public repository of functional genomics data. The GEO repository contains both microarray and gene sequence (RNA-Sequencing) datasets. Present day GEO database contains 34 gene expression datasets and a total of 529 gene expression data samples and 64 gene expression profiles (Table 4). The term “rumen” is enriched with 15 conserved domain sites upon our search in the NCBI database. There is a total of 3,814 records in NCBI identical protein database groups, whose annotated protein sequences are available in GenBank, RefSeq, SwissProt and Protein data bank. This allows researchers to rapidly obtain information about the protein of interest. A total of 233,827 protein sequences are publicly available in the NCBI-Protein database, which can be majorly classified as bacterial origin (203479), RefSeq (4414) and related structures (22525). NCBI-SPARCLE is a database which functionally characterizes and labels the protein sequences based on their unique conserved domains. NCBI-SPARCLE presently contains 29 records related to the rumen. There are 45 protein structures related to the rumen and ruminal microorganisms till date in the NCBI-protein database (Table 5).

Table 4.

Lists the details of gene expression datasets that was retrieved from the NCBI-GEO database using the term “rumen”.

| GEO-ID | Organisms | Method | Platform | Samples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GSE89874 | Bos taurus | RNA-Sequencing | Illumina HiSeq 2000 | 45 |

| GSE81847 | Ovis aries | RNA-Sequencing | Illumina HiSeq 2000 | 62 |

| GSE107550 | Fibro-chip | Microarray (Rumen microbiota) | Custom Agilent gene expression array | 14 |

| GSE89162 | Bos taurus | RNA-Sequencing | Illumina HiSeq 2000 | 38 |

| GSE78197 | Bos taurus | RNA-Sequencing | Illumina HiSeq 2000 | 18 |

| GSE99066 | Capra hircus | RNA-Sequencing | Illumina HiSeq 2500 | 9 |

| GSE76346 | Bos taurus | RNA-Sequencing | Illumina HiSeq 2000 | 10 |

| GSE86323 | Bos taurus | RNA-Sequencing | Illumina HiSeq 2000 | 8 |

| GSE93907 | Fibrobacter succinogenes | RNA-Sequencing | Illumina MiSeq | 10 |

| GSE76501 | Bos taurus | RNA-Sequencing | Illumina HiSeq 2000 | 20 |

| GSE80173 | Bacteria | Microarray (CAZy-chip) | Custom Agilent gene expression array | 94 |

| GSE52193 | Bos taurus | RNA-Sequencing | Illumina HiScanSQ | 63 |

| GSE87391 | Bos taurus | Microarray | Affymetrix Bovine genome array | 10 |

| GSE83813 | Bos taurus | Microarray | Agilent Bovine custom array | 7 |

| GSE82272 | Bos taurus | Microarray | Agilent Bovine custom array | 8 |

| GSE74329 | Bos taurus | RNA-Sequencing | Illumina HiSeq 2000 | 71 |

| GSE74379 | Bacteroides xylanosolvens | RNA-Sequencing | Illumina HiSeq 2000 | 24 |

| GSE68791 | Ovis aries | RNA-Sequencing | Illumina MiSeq | 2 |

| GSE71153 | Bos taurus | RNA-Sequencing | Illumina Genome Analyzer II | 16 |

| GSE63550 | Bos taurus | RNA-Sequencing | Illumina HiSeq 2000 | 4 |

| GSE62624 | Bovine gut metagenome | Microarray | CUST Rumen Bacto-array | 12 |

| GSE50448 | Ovis aries | Microarray | Custom Agilent gene expression array | 8 |

| GSE39206 | Bacteria | SARST libraries | SARST libraries | 9 |

| GSE35212 | Bos taurus | Microarray | Affymetrix Bovine genome array | 14 |

| GSE21492 | Synthetic construct | Microarray | NimbleGen Custom array | 3 |

| GSE16747 | Escherichia coli | Microarray | EDL933 Spotted PCR array | 7 |

| GSE19802 | Bos taurus | Microarray | Custom Bovine array | 10 |

| GSE21544 | Bos taurus | RNA-Sequencing | Illumina Genome Analyzer | 95 |

| GSE18716 | Methanobrevibacter ruminantium | Microarray | Custom microarray | 1 |

| GSE18382 | Bos taurus | Microarray | Custom Bovine microarray | 18 |

| GSE17849 | Bos taurus | Microarray | Affymetrix Bovine Genome array | 12 |

| GSE15916 | Ruminococcus flavefaciens | Microarray | Custom microarray | 4 |

| GSE3029 | Bos taurus | Microarray | Custom microarray | 39 |

| GSE1842 | Bacteria | SARST libraries | SARST libraries | 1 |

Table 5.

List of the details of characterized proteins with corresponding structural details and source organism, available from the NCBI genome database.

| PDB | MMDB | Structural details | Organism |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5K9H | 143569 | Glycoside Hydrolase 29 | Rumen bacterium |

| 4DEV | 107545 | Acetyl Xylan Esterase | Butyrivibrio proteoclasticus B316 |

| 3U37 | 107485 | Acetyl Xylan Esterase | Butyrivibrio proteoclasticus B316 |

| 5WH8 | 160168 | Cellulase | Paraporphyromonas polyenzymogenes |

| 5U22 | 151772 | Glycoside Hydrolase 39 | Neocallimastix frontalis |

| 5G0R | 149432 | Methyl-coenzyme-M-Reductase | Methanothermobacter marburgensis |

| 2WTN | 79382 | Feruloyl esterase | Butyrivibrio proteoclasticus |

| 2WTM | 79381 | Feruloyl esterase | Butyrivibrio proteoclasticus |

| 5K6O | 143776 | Glycoside Hydrolase 3 | Rumen metagenome |

| 5K6N | 143775 | Glycoside Hydrolase 3 | Rumen metagenome |

| 5K6M | 143774 | Glycoside Hydrolase 3 | Rumen metagenome |

| 5K6L | 143773 | Glycoside Hydrolase 3 | Rumen metagenome |

| 4NOV | 123603 | Glycoside Hydrolase 43 | Butyrivibrio proteoclasticus B316 |

| 4KCB | 117247 | Glycoside Hydrolase 5 | Uncultured bacterium |

| 4KCA | 117246 | Glycoside Hydrolase 5 | Bos taurus |

| 5LXV | 144187 | Scaffoldin C Cohesin | Ruminococcus flavefaciens |

| 5D9P | 133948 | Glycoside Hydrolase 5 | Prevotella bryantii |

| 5D9O | 133947 | Glycoside Hydrolase 5 | Prevotella bryantii |

| 5D9N | 133946 | Glycoside Hydrolase 5 | Prevotella bryantii |

| 5D9M | 133945 | Glycoside Hydrolase 5 | Prevotella bryantii |

| 4YHG | 130962 | Glycoside Hydrolase 5 | Bacteroidetes bacterium AC2a |

| 4YHE | 129494 | Glycoside Hydrolase 5 | Bacteroidetes bacterium AC2a |

| 4W8B | 127728 | Glycoside Hydrolase 5 | Uncultured bacterium |

| 4W8A | 127727 | Glycoside Hydrolase 5 | Uncultured bacterium |

| 4W89 | 127726 | Glycoside Hydrolase 5 | Uncultured bacterium |

| 4W88 | 127725 | Glycoside Hydrolase 5 | Uncultured bacterium |

| 4W87 | 127724 | Glycoside Hydrolase 5 | Uncultured bacterium |

| 4W86 | 127723 | Glycoside Hydrolase 5 | Uncultured bacterium |

| 4W85 | 127722 | Glycoside Hydrolase 5 | Uncultured bacterium |

| 4W84 | 127721 | Glycoside Hydrolase 5 | Uncultured bacterium |

| 4KC8 | 117245 | Glycoside Hydrolase 43 | Thermotoga petrophila RKU-1 |

| 4KC7 | 117244 | Glycoside Hydrolase 43 | Thermotoga petrophila RKU-1 |

| 4N2O | 116090 | Cohesin | Ruminococcus flavefaciens |

| 4IU3 | 109437 | Cohesin | Ruminococcus flavefaciens |

| 4IU2 | 109436 | Cohesin | Ruminococcus flavefaciens |

| 4EYZ | 108431 | Cellulosomal protein | Ruminococcus flavefaciens |

| 4AEM | 106860 | Carbohydrate binding module | Eubacterium cellulosolvens |

| 4AEK | 106648 | Carbohydrate binding module | Eubacterium cellulosolvens |

| 4AFD | 106169 | Carbohydrate binding module | Eubacterium cellulosolvens |

| 4BA6 | 105916 | Carbohydrate binding module | Eubacterium cellulosolvens |

| 4AFM | 105889 | Carbohydrate binding module | Eubacterium cellulosolvens |

| 3VDH | 96587 | Glycoside Hydrolase 5 | Prevotella bryantii |

| 2AGK | 39565 | His6 protein | Saccharomyces cerevisiae |

| 5UHX | 156474 | Cellulase | Uncultured bacterium |

| 2VG9 | 61544 | Glycoside Hydrolase 11 | Neocallimastix frontalis |

2.3 NCBI Chemicals Database

The NCBI Chemical database is a public repository for harboring the chemical information and molecular pathways. It provides a direct links to the relevant records such as proteins, genes and other participating compounds in other NCBI databases. The NCBI chemical database can be majorly classified into three domains: (a) chemical assays, (b) biological assays and (c) molecular pathways. We have searched for the publicly available resources that are related to the rumen. A total of 51 resources were available out of which 13 were listed under BioSystems (it provides information about molecular pathways and links to the proteins, genes and chemicals), 15 were listed under PubChem BioAssay (it includes bioactivity screening studies) and 23 were listed under PubChem Substance (it harbors information about chemical substances) (Table 6).

Table 6.

List of the publicly available resources in NCBI Chemicals databases that are related to the term “rumen”.

| NCBI-BioSystems |

|---|

| 9 Conserved Biosystems: L-isoleucine biosynthesis V, Pyruvate fermentation to acetate VII, Oxalate degradation II, Phytol degradation, Coenzyme M biosynthesis I, Pyruvate fermentation to butanoate, L-isoleucine biosynthesis IV, Sulfur reduction I and Fatty acid alpha-oxidation II |

| 4 Organism Specific Biosystems: Phytol degradation, Pyruvate fermentation to acetate VII, Isoleucine biosynthesis IV and Fatty acid alpha-oxidation |

| PubChem BioAssay |

| Insecticidal activity: Myzus persicae, Frankliniella occidentalis, Bemisia argentifolii, Plutella xylostella Anti-feeding activity: Frankliniella occidentalis Multicidal activity: Tetranychus urticae Fungicidal activity: Botryotinia fuckeliana, Podosphaera fuligineam 2-In vitro rumen propionic acid test procedure Antibacterial activity: Streptococcus equi 02I001, Streptococcus zooepidemicus 02H001, Staphylococcus aureus 01A005, Clostridium perfringens 10A002 |

2.4 Application of Metadata Analysis Work-frame

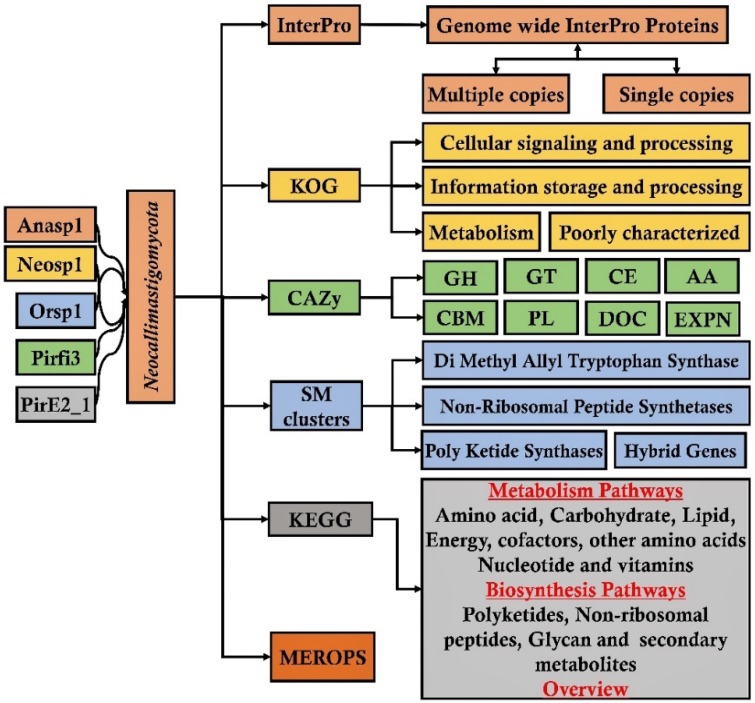

The metadata analysis is statistical data analysis approach which involves systematic analysis of data generated from multiple studies 72, 73. The metadata analysis approach can significantly reveal about the regular involvement of highly active genes or proteins involved in a molecular mechanism. Presence of genomic and proteomic data based on rumen allows data scientists and bioinformaticians to extensively analyze the metadata of various rumen microorganisms. The genome sequencing studies reveal enormous genetic information. Comparative analysis of annotated genome can primarily reveal significant information about the evolutionary loss of genes, broad involvement of these genes (or) proteins in various molecular mechanisms. Biological annotations such as especially InterPro, GO (Gene Ontology), KOG (Eukaryotic orthologous groups), COG (Prokaryotic orthologous groups), CAZy (Carbohydrate active enzymes), SM (Secondary metabolites), KEGG (Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes) and MEROPS (peptide database) helps to compare the genomic data. Metadata analysis of anaerobic fungal genomes belonging to Neocallimastigomycota division (Anaeromyces robustus, Neocallimatix californiae, Orpinomyces sp, Piromyces finnis, Piromyces sp E2) has revealed about extensive loss of genes involved metabolism of ligninolytic genes 74. It was also reported that these anaerobic fungi encode for arsenal of enzymes which are involved in breakdown and conversion of plant cell wall carbohydrates. This metadata analysis study also reported that these anaerobic fungi possess highest number of carbohydrate active enzymes compared to any other fungal species 74. Similarly, metadata analysis study of different wood-decaying fungi (white-rot, brown-rot and soft-rot fungi) has reported about the genes and proteins underlying various molecular mechanisms employed during metabolism of plant biomass components 75. This study has also extensively reported and compared the total cellulolytic, hemicellulolytic, pectinolytic and ligninolytic abilities of white, brown and soft rot fungi 75 (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Pictorial representation of metadata analysis workflow applied for analyzing and understanding the genomic metadata analysis approach;

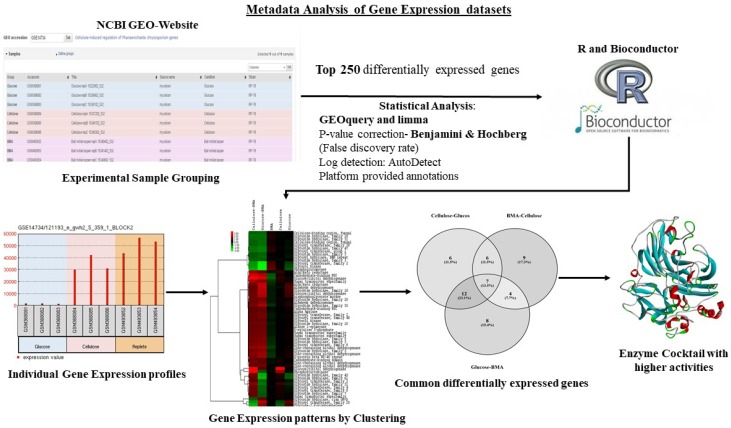

The high-throughput gene expression studies (e.g. microarray, RNA-Seq) of microorganisms reveals highly significant molecular information on gene regulation. Analyzing the common gene expression patterns in microorganisms will play a crucial role in deciphering biological pathways and molecular mechanisms, dominant genes/proteins with greater importance. A best way to study the common gene expression pattern would be to perform a gene-expression metadata analysis. The publicly available gene expression datasets can be retrieved from the gene expression omnibus (GEO) and Array Express repositories by performing a simple search over all the database queries. Once retrieved these datasets can be analyzed using different methods and software packages summarized below (Table 7). Recent studies on metadata analysis of Phanerochaete chrysosporium and Postia placenta gene expression datasets have revealed the common differentially expressed gene patterns involved in lignocellulose metabolism. These studies have also reported the tentative molecular networks employed by these fungi during plant biomass degradation 76-79. We have pictorially represented the tentative metadata analysis workflow implemented in previous studies, for analyzing and understanding the genomic and proteomic datasets (Figure 7).

Table 7.

List of softwares (or) R-packages used for the metadata analysis of gene expression datasets. (Note: All the words written in bold are the names of the softwares (or) packages).

| Name | Software type | Operating system | Programming language |

|---|---|---|---|

| MEM | NA | Web user interface | C++, JavaScript, Perl |

| Onto-Compare, PhenoGen, ExAtlas MiMiR, INMEX |

NA | Web user interface | NA |

| ImaGEO, ShinyMDE jNMFMA |

NA | Web user interface | R |

| Bloader | Package (or) Module | Unix/Linux, Mac OS, Windows | Graphical user interface |

| MAAMD | Package (or) Module | Mac OS, Windows | NA |

| Package (or) Module Unix/Linux, Mac OS, Windows, R |

mixOmics, MetaOmics, CoGAPS, MetaQC, metaAnalyzeAll, metafor metaMA, OrderedList, metahdep, YuGene, metaArray, RankAggreg, MergeMaid, MAMA, NMF, GeneMeta, MetaDE, MetaSparseKmeans, categoryCompare, IQRray |

||

| A-MADMAN | Package (or) Module | Unix/Linux, Mac OS, Windows | R, Python |

| MetaKTSP | Toolkit/Suite | Unix/Linux, Mac OS, Windows | R |

Figure 7.

Pictorial representation of metadata analysis workflow applied for analyzing and understanding the proteomic metadata analysis approach.

2.5 Potential Applications

Rumen microbiota exhibit several potential applications in the dairy, feedstock, winery and brewery, pulp and paper, biofuel, biorefinery, textiles-detergent, food and pharmaceutical industries. Rumen microbiota can be potentially used in preparation of industrially important enzyme mixtures such as cellulases, xylanases, pectinases, amylases, lipases and proteases, which are widely used in various industrial processes 80, 81. Recent studies have proved the importance of rumen microorganisms in the breakdown and conversion of lignocellulosic components (cellulose, hemicelluloses, pectin, lignin) to commercially important products such as bioethanol and other platform chemicals including hydrogen, butanol, iso-butanol, methane and other energy yielding products 82. Enhancing the rate of digestion and metabolism of the feedstock by cattle is one of the major challenges in the dairy and feedstock industries. Several studies were continuously being conducted with rumen microorganisms and the enzymes secreted by these for pretreating the feedstock to enhance its digestion rate by ruminating animals 83. Simultaneously, studies were also being conducted to develop genetically modified microorganisms (especially bacteria) to improve the process of digestion and enhance the rumen function 84. Thus, understanding the microbial diversity of rumen will significantly benefit various industrial processes.

3.0 Conclusions

All the above studies and reports strongly endorses that ruminating animals are solely dependent on their microbiota for their daily metabolism. Recent studies based on gut microbiomes of several ruminating animals, termite, mice and human have significantly enhanced the current knowledge about gut residing microorganisms. The JGI-MycoCosm and Hungate 1000 microbial genome sequencing projects revealed whole genome sequences of about 1087 fungal genomes and 501 rumen microorganisms. Although studies have reported that one milliliter of ruminal fluid contains approximately 105 to 106 protozoans and about 1010 to 1011 of bacterial inhabitants, there is still a long way in understanding the rumen microbiome and their role in physiology of ruminating animals. In this article we have extensively discussed the recent advancements in understanding the role of rumen microbiota in the degradation and metabolism of plant biomass. We have studied and listed all the genomic and proteomic studies based on rumen and ruminal microbiota. Further studies about the ruminal microbiota may benefit various industrial sectors significantly, including biofuel, biorefining, pretreatment of cattle feedstocks and several other processes. Our article can be used as a primer for understanding and focusing towards developing efficient recombinant microbial strains with higher plant biomass degrading abilities.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada Funding (RGPIN-2017-05366) to Wensheng Qin and Mitacs Globalink Research Scholarship award to Ayyappa Kumar Sista Kameshwar.

Authors' contributions

AKSK has summarized the published data and drafted the manuscript. WQ and LPR contributed in revisiting and reviewing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Abbreviations

- DOE

Department of Energy

- JGI

Joint Genome Institute

- GO

Gene Ontology

- KOG

Eukaryotic orthologous groups

- COG

Prokaryotic orthologous groups

- CAZy

Carbohydrate active enzymes

- SM

Secondary metabolites

- KEGG

Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes.

References

- 1.Ishler VA, Heinrichs AJ, Varga GB. From feed to milk: understanding rumen function: Pennsylvania State University; 1996.

- 2.Hungate R. The rumen microbial ecosystem. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 1975;6:39–66. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hobson PN, Stewart CS. The rumen microbial ecosystem: Springer Science & Business Media; 2012.

- 4.Harfoot C, Hazlewood G. Lipid metabolism in the rumen. The rumen microbial ecosystem: Springer; 1997. p. 382-426. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krehbiel C. INVITED REVIEW: Applied nutrition of ruminants: Fermentation and digestive physiology1. The Professional Animal Scientist. 2014;30:129–39. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Becker R, Marshall S, Arnold PD. Anatomy, Development, and Functions of the Bovine Omasum1. Journal of Dairy Science. 1963;46:835–9. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bohatier J. The rumen protozoa: taxonomy, cytology and feeding behaviour. Rumen microbial metabolism and ruminant digestion Paris: Inra; 1991. pp. 27–38. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qi M, Wang P, O'Toole N, Barboza PS, Ungerfeld E, Leigh MB. et al. Snapshot of the eukaryotic gene expression in muskoxen rumen—a metatranscriptomic approach. PloS one. 2011;6:e20521. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Engelhardt W, Hauffe R. Role of the omasum in absorption and secretion of water and electrolytes in sheep and goats. Digestion and Metabolism in the Ruminant; 1975. pp. 216–30. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahvenjärvi S, Vanhatalo A, Huhtanen P, Varvikko T. Determination of reticulo-rumen and whole-stomach digestion in lactating cows by omasal canal or duodenal sampling. British Journal of Nutrition. 2000;83:67–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hofmann RR. The ruminant stomach. Stomach structure and feeding habits of East African game ruminants. The ruminant stomach Stomach structure and feeding habits of East African game ruminants; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Towne G, Nagaraja T. Omasal ciliated protozoa in cattle, bison, and sheep. Applied and environmental microbiology. 1990;56:409–12. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.2.409-412.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Longenbach J, Heinrichs A. A review of the importance and physiological role of curd formation in the abomasum of young calves. Animal feed science and technology. 1998;73:85–97. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Constable P, Hoffsis G, Rings D. The reticulorumen: normal and abnormal motor function. Part I. Primary contraction cycle. Compendium on Continuing Education for the Practicing Veterinarian. 1990;12:1008–14. [Google Scholar]

- 15.LeBlanc S, Leslie K, Duffield T. Metabolic predictors of displaced abomasum in dairy cattle. Journal of dairy science. 2005;88:159–70. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(05)72674-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Church DC. The Ruminant animal: digestive physiology and nutrition; 1988.

- 17.Doreau M, Chilliard Y. Digestion and metabolism of dietary fat in farm animals. British Journal of Nutrition. 1997;78:S15–S35. doi: 10.1079/bjn19970132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chilliard Y. Dietary fat and adipose tissue metabolism in ruminants, pigs, and rodents: A review. Journal of Dairy Science. 1993;76:3897–931. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(93)77730-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Doreau M, Ferlay A. Digestion and utilisation of fatty acids by ruminants. Animal Feed Science and Technology. 1994;45:379–96. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Soest PJ. Ruminant fat metabolism with particular reference to factors affecting low milk fat and feed efficiency. A review. Journal of Dairy Science. 1963;46:204–16. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Calsamiglia S, Stern MD. A three-step in vitro procedure for estimating intestinal digestion of protein in ruminants. Journal of Animal Science. 1995;73:1459–65. doi: 10.2527/1995.7351459x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krause D, Nagaraja T, Wright A, Callaway T. Board-invited review: Rumen microbiology: Leading the way in microbial ecology 1, 2. Journal of animal science. 2013;91:331–41. doi: 10.2527/jas.2012-5567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carter RR, Grovum WL. A review of the physiological significance of hypertonic body fluids on feed intake and ruminal function: salivation, motility and microbes. Journal of Animal Science. 1990;68:2811–32. doi: 10.2527/1990.6892811x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harfoot C. Anatomy, physiology and microbiology of the ruminant digestive tract. Lipid metabolism in ruminant animals: Elsevier; 1981. p. 1-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bailey C. The rate of secretion of mixed saliva in the cow. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society: CAB INTERNATIONAL C/O PUBLISHING DIVISION, WALLINGFORD OX10 8DE, OXON, ENGLAND; 1959. p. R13-R. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bailey C, Balch C. Saliva secretion and its relation to feeding in cattle: 2.* The composition and rate of secretion of mixed saliva in the cow during rest. British Journal of Nutrition. 1961;15:383–402. doi: 10.1079/bjn19610048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kay R, Engelhardt Wv, White R. The digestive physiology of wild ruminants. Digestive physiology and metabolism in ruminants: Springer; 1980. p. 743-61. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Church DC. Digestive physiology and nutrition of ruminants. Volume 2. Nutrition: O & B Books, Inc. 1979.

- 29.Sniffen C, Herdt H. The Veterinary Clinics of North America: Food Animal Practice, Vol 7, No 2. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders Company; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kay R. Comparative studies of food propulsion in ruminants. Physiological and pharmacological aspects of the reticulo-rumen: Springer; 1987. p. 155-70. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keeney M, Phillipson A. Physiology of digestion and metabolism in the ruminant. Lipid metabolism in the rumen Oriel Press, Newcastle upon Tyne; 1970. pp. 489–503. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krause DO, Denman SE, Mackie RI, Morrison M, Rae AL, Attwood GT. et al. Opportunities to improve fiber degradation in the rumen: microbiology, ecology, and genomics. FEMS microbiology reviews. 2003;27:663–93. doi: 10.1016/S0168-6445(03)00072-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dehority BA. Rumen microbiology: Nottingham University Press Nottingham; 2003.

- 34.Russell JB. Rumen microbiology and its role in ruminant nutrition: Cornell University; 2002.

- 35.Caldwell DR, Bryant MP. Medium without rumen fluid for nonselective enumeration and isolation of rumen bacteria. Applied microbiology. 1966;14:794–801. doi: 10.1128/am.14.5.794-801.1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Orpin C. Studies on the rumen flagellate Neocallimastix frontalis. Microbiology. 1975;91:249–62. doi: 10.1099/00221287-91-2-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bauchop T. Rumen anaerobic fungi of cattle and sheep. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 1979;38:148–58. doi: 10.1128/aem.38.1.148-158.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Orpin C, Joblin K. The rumen anaerobic fungi. The rumen microbial ecosystem: Springer; 1997. p. 140-95. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bauchop T. The anaerobic fungi in rumen fibre digestion. Agriculture and Environment. 1981;6:339–48. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lowe SE, Theodorou M, Trinci A. Cellulases and xylanase of an anaerobic rumen fungus grown on wheat straw, wheat straw holocellulose, cellulose, and xylan. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 1987;53:1216–23. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.6.1216-1223.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gill JW, King KW. Rumen Microbiology, Characteristics of Free Rumen Cellulases. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 1957;5:363–7. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kaufmann W, Hagemeister H, Dirksen G. Adaptation to changes in dietary composition, level and frequency of feeding. Digestive physiology and metabolism in ruminants: Springer; 1980. p. 587-602. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kocherginskaya SA, Aminov RI, White BA. Analysis of the rumen bacterial diversity under two different diet conditions using denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis, random sequencing, and statistical ecology approaches. Anaerobe. 2001;7:119–34. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jouany J, Ushida K. The role of protozoa in feed digestion-Review. Asian-Australasian Journal of Animal Sciences. 1999;12:113–28. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tajima K, Aminov R, Nagamine T, Matsui H, Nakamura M, Benno Y. Diet-dependent shifts in the bacterial population of the rumen revealed with real-time PCR. Applied and environmental microbiology. 2001;67:2766–74. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.6.2766-2774.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Morgavi D, Forano E, Martin C, Newbold C. Microbial ecosystem and methanogenesis in ruminants. Animal. 2010;4:1024–36. doi: 10.1017/S1751731110000546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ozutsumi Y, Tajima K, Takenaka A, Itabashi H. The effect of protozoa on the composition of rumen bacteria in cattle using 16S rRNA gene clone libraries. Bioscience, biotechnology, and biochemistry. 2005;69:499–506. doi: 10.1271/bbb.69.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Whitford MF, Forster RJ, Beard CE, Gong J, Teather RM. Phylogenetic analysis of rumen bacteria by comparative sequence analysis of cloned 16S rRNA genesß. Anaerobe. 1998;4:153–63. doi: 10.1006/anae.1998.0155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jarvis GN, Strömpl C, Burgess DM, Skillman LC, Moore ER, Joblin KN. Isolation and identification of ruminal methanogens from grazing cattle. Current Microbiology. 2000;40:327–32. doi: 10.1007/s002849910065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shin E, Cho K, Lim W, Hong S, An C, Kim E. et al. Phylogenetic analysis of protozoa in the rumen contents of cow based on the 18S rDNA sequences. Journal of applied microbiology. 2004;97:378–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2004.02304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sylvester JT, Karnati SK, Yu Z, Morrison M, Firkins JL. Development of an assay to quantify rumen ciliate protozoal biomass in cows using real-time PCR. The Journal of Nutrition. 2004;134:3378–84. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.12.3378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Denman SE, McSweeney CS. Development of a real-time PCR assay for monitoring anaerobic fungal and cellulolytic bacterial populations within the rumen. FEMS microbiology ecology. 2006;58:572–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2006.00190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brulc JM, Antonopoulos DA, Miller MEB, Wilson MK, Yannarell AC, Dinsdale EA, Gene-centric metagenomics of the fiber-adherent bovine rumen microbiome reveals forage specific glycoside hydrolases. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences; 2009. pnas. 0806191105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Qu A, Brulc JM, Wilson MK, Law BF, Theoret JR, Joens LA. et al. Comparative metagenomics reveals host specific metavirulomes and horizontal gene transfer elements in the chicken cecum microbiome. PloS one. 2008;3:e2945. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Flint HJ, Bayer EA, Rincon MT, Lamed R, White BA. Polysaccharide utilization by gut bacteria: potential for new insights from genomic analysis. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2008;6:121. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li RW, Connor EE, Li C, Baldwin V, Ransom L, Sparks ME. Characterization of the rumen microbiota of pre-ruminant calves using metagenomic tools. Environmental microbiology. 2012;14:129–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02543.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jami E, Mizrahi I. Composition and similarity of bovine rumen microbiota across individual animals. PloS one. 2012;7:e33306. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pope PB, Mackenzie AK, Gregor I, Smith W, Sundset MA, McHardy AC. et al. Metagenomics of the Svalbard reindeer rumen microbiome reveals abundance of polysaccharide utilization loci. PLoS One. 2012;7:e38571. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dai X, Zhu Y, Luo Y, Song L, Liu D, Liu L. et al. Metagenomic insights into the fibrolytic microbiome in yak rumen. PLoS One. 2012;7:e40430. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ross EM, Petrovski S, Moate PJ, Hayes BJ. Metagenomics of rumen bacteriophage from thirteen lactating dairy cattle. BMC microbiology. 2013;13:242. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-13-242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Morgavi DP, Kelly W, Janssen P, Attwood G. Rumen microbial (meta) genomics and its application to ruminant production. Animal. 2013;7:184–201. doi: 10.1017/S1751731112000419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Parmar NR, Solanki JV, Patel AB, Shah TM, Patel AK, Parnerkar S. et al. Metagenome of Mehsani buffalo rumen microbiota: an assessment of variation in feed-dependent phylogenetic and functional classification. Journal of molecular microbiology and biotechnology. 2014;24:249–61. doi: 10.1159/000365054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Henderson G, Cox F, Ganesh S, Jonker A, Young W, Collaborators GRC. et al. Rumen microbial community composition varies with diet and host, but a core microbiome is found across a wide geographical range. Scientific reports. 2015;5:14567. doi: 10.1038/srep14567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kameshwar A, Qin W. Recent Developments in Using Advanced Sequencing Technologies for the Genomic Studies of Lignin and Cellulose Degrading Microorganisms. International journal of biological sciences. 2016;12:156. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.13537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rubin EM. Genomics of cellulosic biofuels. Nature. 2008;454:841–5. doi: 10.1038/nature07190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hess M, Sczyrba A, Egan R, Kim T-W, Chokhawala H, Schroth G. et al. Metagenomic discovery of biomass-degrading genes and genomes from cow rumen. Science. 2011;331:463–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1200387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Baar C, Eppinger M, Raddatz G, Simon J, Lanz C, Klimmek O. et al. Complete genome sequence and analysis of Wolinella succinogenes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2003;100:11690–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1932838100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Grigoriev IV, Nikitin R, Haridas S, Kuo A, Ohm R, Otillar R. et al. MycoCosm portal: gearing up for 1000 fungal genomes. Nucleic acids research. 2013;42:D699–D704. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Grigoriev IV, Cullen D, Goodwin SB, Hibbett D, Jeffries TW, Kubicek CP. et al. Fueling the future with fungal genomics. Mycology. 2011;2:192–209. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Seshadri R, Leahy SC, Attwood GT, Teh KH, Lambie SC, Cookson AL. et al. Cultivation and sequencing of rumen microbiome members from the Hungate1000 Collection. Nature biotechnology. 2018;36:359. doi: 10.1038/nbt.4110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jewell KA, McCormick C, Odt CL, Weimer PJ, Suen G. Ruminal bacterial community composition in dairy cows is dynamic over the course of two lactations and correlates with feed efficiency. Applied and environmental microbiology; 2015. AEM. 00720-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wirapati P, Sotiriou C, Kunkel S, Farmer P, Pradervand S, Haibe-Kains B. et al. Meta-analysis of gene expression profiles in breast cancer: toward a unified understanding of breast cancer subtyping and prognosis signatures. Breast Cancer Research. 2008;10:R65. doi: 10.1186/bcr2124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Waldron L, Riester M. Meta-analysis in gene expression studies. Statistical Genomics: Springer; 2016. p. 161-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kameshwar AKS, Qin W. Genome Wide Analysis Reveals the Extrinsic Cellulolytic and Biohydrogen Generating Abilities of Neocallimastigomycota Fungi. Journal of genomics. 2018;6:74. doi: 10.7150/jgen.25648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sista Kameshwar AK, Qin W. Comparative study of genome-wide plant biomass-degrading CAZymes in white rot, brown rot and soft rot fungi. Mycology; 2017. pp. 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kameshwar AKS, Qin W. Metadata Analysis of Phanerochaete chrysosporium gene expression data identified common CAZymes encoding gene expression profiles involved in cellulose and hemicellulose degradation. International journal of biological sciences. 2017;13:85. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.17390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kameshwar AKS, Qin W. Gene expression metadata analysis reveals molecular mechanisms employed by Phanerochaete chrysosporium during lignin degradation and detoxification of plant extractives. Current genetics. 2017;63:877–94. doi: 10.1007/s00294-017-0686-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kameshwar AKS, Qin W. Analyzing Phanerochaete chrysosporium gene expression patterns controlling the molecular fate of lignocellulose degrading enzymes. Process Biochemistry. 2018;64:51–62. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kameshwar AKS, Qin W. Molecular Networks of Postia placenta Involved in Degradation of Lignocellulosic Biomass Revealed from Metadata Analysis of Open Access Gene Expression Data. International Journal of Biological Sciences. 2018;14:237–52. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.22868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cheng K, Lee S, Bae H, Ha J. Industrial applications of rumen microbes. ASIAN AUSTRALASIAN JOURNAL OF ANIMAL SCIENCES. 1999;12:84–92. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jami E, White BA, Mizrahi I. Potential role of the bovine rumen microbiome in modulating milk composition and feed efficiency. PLoS One. 2014;9:e85423. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yue Z-B, Li W-W, Yu H-Q. Application of rumen microorganisms for anaerobic bioconversion of lignocellulosic biomass. Bioresource technology. 2013;128:738–44. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2012.11.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Carrere H, Antonopoulou G, Affes R, Passos F, Battimelli A, Lyberatos G. et al. Review of feedstock pretreatment strategies for improved anaerobic digestion: from lab-scale research to full-scale application. Bioresource technology. 2016;199:386–97. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2015.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Teather RM. Genetic Engineering of Rumen Bacteria for Improved Productive Efficiency in Ruminants. Biotechnology Research and Applications: Springer; 1988. p. 3-11. [Google Scholar]