Abstract

This is the first report, to our knowledge, of a fracture, unrelated to trunnion corrosion, through the midneck of a well-fixed uncemented cobalt-chromium alloy femoral component that had been implanted via a total hip revision arthroplasty 25 years ago. Three years after a second revision for polyethylene wear, the patient noted an acute onset of pain in the left hip. There was no antecedent pain in the hip or thigh. Radiographs and intraoperative findings showed a well-fixed femoral component. Electron microscopic retrieval analysis showed intergranular material cracks. Revision of the femoral component was performed with an extended trochanteric osteotomy. This fracture of the femoral component neck was likely related to metal fabrication techniques, and surveillance of this component may be warranted.

Keywords: Femoral component neck fracture, Total hip arthroplasty, Revision, Catastrophic failure

Introduction

Fracture of the femoral component of a total hip arthroplasty is a rare cause for revision compared with infection, aseptic loosening, and instability [1], [2]. Fracture of both cemented and cementless femoral component stems has been reported [1], [2], [3], [4]. In the 1970s, the reported rate of stem fracture ranged from 0.23% to 10.7% [3], [4], [5]. These fractures usually occurred in the middle third of the component and were due to fatigue failure related to cantilever bending with insufficient proximal support or fixation [6]. Despite improvements in materials and manufacturing techniques, fracture of modern cemented femoral components has still been reported [6], [7], [8], with possible causative factors including obesity, excessive physical activity, and severe trauma [9]. Other patient factors include male sex, tall patients, concurrent lumbar spine pathology, and presence of bilateral hip arthroplasties [3], [7], [10]. Predisposing surgical factors include varus alignment or an undersized femoral component, an asymmetric cement mantle, and poor proximal bone support [7], [10], [11], [12]. Flaws in design, manufacturing defects, and stress risers from postmanufacturing processing have also been associated with femoral component fracture [6], [10], [13]. Fracture of an uncemented cobalt-chromium alloy stem with small beads (anatomic medullary locking; DePuy International, Leeds, England) was associated with small-diameter stems implanted in revisions and deficiency of the proximal femur [14].

Fracture of the neck of a cemented or uncemented femoral component is an even rarer complication than stem fracture [9], [13], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19]. This complication is distinct from whole trunnion failure or fracture as has been recently reported with certain femoral components and related to severe corrosion [20], [21]. This is the first report, to our knowledge, of a patient with a nontraumatic fracture through the neck (distal to the trunnion) of an uncemented, small-bead cobalt-chromium alloy femoral component, occurring 25 years after implantation. Although a case series of stem fractures was reported for this particular femoral component related to loosening [8], the current case is unique. The patient provided informed consent for publication of deidentified medical information regarding this case.

Case history

The patient is a 71-year-old man (weight 94.2 kg, height 185.4 cm, body mass index 27.4) who underwent a left cemented total hip arthroplasty in 1982 for posttraumatic arthritis at another hospital. In 1992, at a different hospital, he had revision of both components for aseptic loosening with uncemented components: a cobalt-chromium alloy with a bead size of #10 C-taper stem (Omnifit; Osteonics, Rutherford, NJ), a +10 cobalt-chromium alloy femoral head, and a 62-mm hemispherical acetabular component with conventional polyethylene. In 2014, he developed mild hip pain, and radiographs showed severe polyethylene wear with osteolysis in the greater trochanter (Fig. 1a and b). At revision at our hospital, both components were well fixed, and liner and head exchange were performed, using a highly cross-linked polyethylene liner and a +10 C-taper low friction ion treatment 32-mm cobalt-chromium alloy femoral head (Stryker, Rutherford, NJ). The intraoperative cultures yielded no growth. No postoperative complications occurred, and the patient resumed full activities at 3 months. The patient was asymptomatic until 4 years later when he presented to the emergency department with an acute onset of pain in the left hip after stepping down off a ladder. He did not fall but heard a loud “crack” with immediate pain and inability to ambulate. Before this episode, he was able to ambulate 2–3 miles per day without a support. The left leg was shortened and externally rotated. Radiographs showed a fracture through the neck of the well-fixed femoral component distal to the trunnion (Fig. 2a and b). C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate were within normal limits.

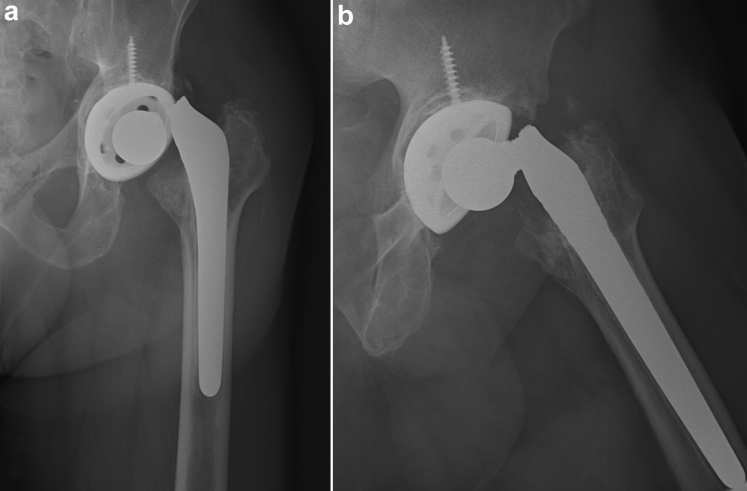

Figure 1.

Anteroposterior (a) and lateral (b) radiographs of the left hip before head and liner exchange. Radiographs demonstrate polyethylene wear and osteolysis in the greater trochanter.

Figure 2.

Anteroposterior (a) and oblique lateral (b) radiographs of the left hip on the day of injury, with fracture through the neck of the femoral component.

At revision, no corrosion at the trunnion was observed, and no pseudotumor or abductor muscle necrosis was found. The acetabular component was well fixed and was retained. The femoral component removal required a 10-cm extended trochanteric osteotomy, and a modular tapered fluted stem (Restoration; Stryker) was implanted, with a 32 + 8-mm cobalt-chromium alloy head; the osteotomy was repaired with cables. No postoperative complications occurred. At 3 months postoperatively, the patient had mild thigh pain and was able to ambulate long distances with one crutch. Radiographs showed good fixation and a healed osteotomy (Fig. 3a and b).

Figure 3.

Anteroposterior (a) and lateral (b) radiographs of the left hip at 3 months postoperatively. Radiographs demonstrate healing of the osteotomy site and stable positioning of the components.

Implant analysis

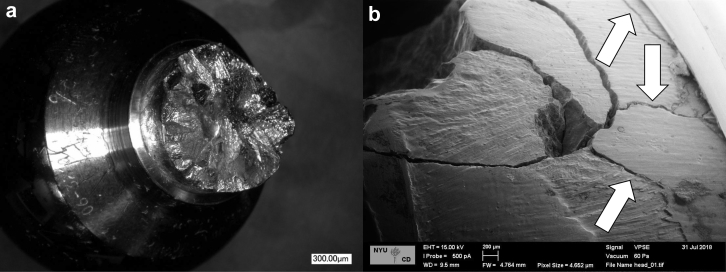

The fractured component was evaluated by one of the authors (T.M.W.) by light and scanning electron microscopy. No notable corrosion of the trunnion was found, consistent with the intraoperative findings. The surfaces of the fracture of the neck are consistent with fatigue fractures the in cobalt-chromium alloy with an intergranular appearance (Fig. 4a). In addition to the crack that formed the main fracture (Fig. 4b), electron microscopy showed a considerable number of intergranular cracks, consistent with intergranular corrosion, as the probable cause for the failure. No accompanying material defects, such as porosity, were noted on the fracture surface.

Figure 4.

Macroscopic photograph (a) of the fractured implant demonstrating typical fracture between the grains of the Co-Cr casting that resembles a series of up and down pyramids. Electron microscopy image (b) demonstrating additional intergranular cracks besides the one that formed the main fracture (arrow heads). Co-Cr, cobalt-chromium.

Discussion

The published reports of fracture of the neck of a femoral component include all 3 of the common orthopedic metallic alloys, with failures attributed to several causes (Table 1). Burstein and Wright first reported the fracture of the neck of a stainless steel, cemented femoral component in 2 patients [15]. These fractures were associated with a design flaw in the trapezoidal shaped neck leading to excessive tensile stress [15]. Rand and Chao [18] reported 2 fractures of the neck and 32 fractures of the stem of the same prosthesis in a case series of 1808 hips. Vatani et al. [13] reported 9 patients with a fracture of the neck of a stainless steel Charnley-type cemented femoral component and concluded that these fractures were associated with the design of an inadequately congruent radius, leading to abnormal force transmission through the neck. Aspenberg et al. [22] reported 5 neck fractures in 25 Brunswik-type cemented components, with failure attributed to a faulty welding procedure. Fractures of the femoral component neck have also been reported with cemented and cementless titanium alloy femoral components. Magnissalis et al. [23] described 2 titanium alloy cemented femoral components (Optifix; Smith and Nephew, Andover, MA) that had fractured at the stem-neck junction. Light and electron microscopy showed striations, with cracks propagating along multiple plateaus, consistent with fatigue. Fatigue fractures of the neck of the femoral component of 3 other titanium alloy stems have been reported: the hydroxyapatite-coated Furlong (JRI Limited, London, UK) [9], the SEM3 type (Science et Médecine, Montrouge, France) [17], and the Accolade I (Stryker, Kalamazoo, MI) [1].

Table 1.

Reports of fractures of the neck of femoral components.

| Authors | Year | Fixation | Material | Component name (manufacturer) | No. of cases | Presumed etiology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burstein and Wright [15] | 1985 | Cement | Stainless steel | Trapezoidal-28 (Zimmer) | 2 | Design flaw |

| Rand and Chao [18] | 1987 | Cement | Stainless steel | Trapezoidal-28 (Zimmer) | 2 | Design flaw |

| Aspenberg et al [22] | 1987 | Cement | Stainless steel | Brunswik (Mecron GmbH) | 5 | Welding process |

| Vatani et al [13] | 2002 | Cement | Stainless steel | Charnley type (MedTec Brazil) | 9 | Design flaw |

| Magnisallis et al [23] | 2003 | Cement | Titanium alloy | Optifix (Smith and Nephew) | 2 | Fatigue failure at the area of porous coating |

| Morgan-Hough et al [9] | 2004 | Cementless | Titanium alloy | Furlong (JRI Limited) | 1 | Fatigue |

| Grivas et al [17] | 2007 | Cementless | Titanium alloy | SEM3 type (Science et Médecine) | 1 | Fatigue, patient with strenuous manual labor occupation |

| Spayner et al [1] | 2016 | Cementless | Titanium alloy | Accolade I (Stryker) | 3 | Unknown (retrieval analysis not performed) |

| Lee and Kim [6] | 2001 | Cement | Co-Cr alloy | Opteon (Exactech) | 2 | Laser etching stress riser |

| Gilbert et al [16] | 1994 | Cementless | Co-Cr alloy | PCA (Howmedica) | 2 | Corrosion |

| Lam et al [24] | 2008 | Cementless | Co-Cr alloy | Omnifit (Osteonics) | 4 | Crevices and intergranular corrosion |

| Morley et al [10] | 2012 | Cemented | Co-Cr alloy | C-STEM (DePuy) | 1 | Corrosion in large head metal-on-metal hip |

| Present case | 2018 | Cementless | Co-Cr alloy | Omnifit (Osteonics) | 1 | Casting process |

Co-Cr, cobalt-chromium.

Fractures of the proximal portion of uncemented titanium alloy femoral components with cobalt-chromium alloy femoral heads and highly cross-linked polyethylene have also been reported secondary to mechanically assisted crevice corrosion or trunnionosis of the modular connection between the head and stem. Trunnionosis has been associated with a variety of prodromal symptoms and operative findings of pseudotumor, soft tissue damage, and visible corrosion at the head-neck junction [25], [26], [27]. Extreme cases show gross material loss and deformation of the trunnion on the femoral stem, across several designs with variable neck lengths and head sizes, “skirted or nonskirted” femoral heads [20]. One report of fracture of the proximal femoral component with trunnionosis noted corrosion, scoring, and scratches at the site of fracture [21]. There have also been reports of fracture of the neck of modular or dual-taper titanium alloy femoral components, but these were likely related to mechanically assisted crevice corrosion in mixed metal composites [28], [29].

Only fewer reports of fractures of the neck of a cobalt-chromium alloy femoral component exist. Lee and Kim [6] reported that the early fracture of the neck of 2 cemented cobalt-chromium components (Opteon; Exactech, Gainesville, FL) was associated with a stress riser at the site of laser etching. Other reports noted corrosion at the site of fracture. Gilbert et al. [16], [30] reported 2 uncemented prostheses (PCA; Howmedica, Rutherford, NJ) with fracture of the neck, intragranular corrosion and deep penetration into the microstructure, increased porosity at the grain boundaries, and cyclic fatigue loading of the neck. Lam et al. [24] reported 4 cases of fracture of the neck, directly adjacent to the femoral head, in uncemented femoral components (Omnifit; Osteonics, Allandale, NJ). Retrieval analysis showed corrosion, and 3 of the 4 hips had a “skirted” modular head that may have contributed to impingement and corrosion. Morley et al. [10] reported a fracture of the neck of a cemented femoral component (C-STEM; DePuy, Warsaw, IN) in a metal-on-metal hip and hypothesized that increased fretting of the large femoral head on a stem with a small-diameter taper contributed to corrosion and the eventual fracture.

This case report is distinct from the other cases of fracture of the neck of a cobalt-chromium alloy femoral component because this component was uncemented, with a 32-mm metal femoral head on a polyethylene liner, and the fracture occurred in the midneck region. No evidence of corrosion secondary to fretting of the trunnion was evident on microscopic analysis. The femoral component had a well-fixed, small bead ingrowth surface and was without apparent material defects or mechanical damage. The patient was not obese, did not participate in high-impact activities, and had no other risk factors for femoral component fracture [3], [7], [10], [12]. Furthermore, the fracture was unrelated to mechanically assisted crevice corrosion because the patient was asymptomatic before the sudden, atraumatic fracture of the neck and no pseudotumor or soft tissue damage was found intraoperatively. Gilbert and colleagues [16] also reported on neck fractures in 2 modular hip implants with cobalt-chromium alloy heads and stems, but in both those cases, the intergranular porosity, caused by improper manufacturing, contributed directly to the fractures. Lee and Kim [6], in their report of 2 neck fractures in cobalt-chromium alloy head and stem femoral components, attributed the fatigue fractures to stress concentrations caused by local metallurgical alterations in the region around the laser-etched markings on the neck. We found no such evidence of manufacturing or etching problems in the fractured component from our case. We suggest that this case represents a type of fatigue failure. The long neck length (+10) and longevity of the implant (25 years) likely contributed to cantilever bending forces, resulting in failure at the midpoint of the neck between the center of rotation and the fixed portion of the stem. However, it was not associated with loosening or mechanically assisted crevice corrosion. This rare instance of neck fracture has not yet been reported to MedWatch, the FDA's Safety Information and Adverse Reporting Program. Our institution does not require reporting; however, submission of device failures to centralized databases is important.

Summary

Fracture of the neck of a femoral component is a rare complication after total hip arthroplasty with cemented and, less commonly, uncemented components and is usually associated with design or material defects or trunnion corrosion. Although this cobalt-chromium alloy femoral component design, when cemented, has been reported to cause fracture in the midstem after proximal loosening, this is the first report of a fracture of the neck of a well-fixed uncemented femoral component not related to trunnion corrosion.

Footnotes

One or more of the authors of this article have disclosed potential or pertinent conflicts of interest, which may include receipt of payment, either direct or indirect, institutional support, or association with an entity in the biomedical field which may be perceived to have potential conflict of interest with this work. For full disclosure statements refer to https://doi.org/10.1016/j.artd.2019.01.006.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Spanyer J., Hines J., Beaumont C.M., Yerasimides J. Catastrophic femoral neck failure after THA with the accolade((R)) I stem in three patients. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474:1333. doi: 10.1007/s11999-015-4438-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bozic K.J., Kurtz S.M., Lau E. The epidemiology of revision total hip arthroplasty in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:128. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Charnley J. Fracture of femoral prostheses in total hip replacement. A clinical study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1975;111:105. doi: 10.1097/00003086-197509000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heck D.A., Partridge C.M., Reuben J.D. Prosthetic component failures in hip arthroplasty surgery. J Arthroplasty. 1995;10:575. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(05)80199-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martens M., Aernoudt E., de Meester P. Factors in the mechanical failure of the femoral component in total hip prosthesis. Report of six fatigue fractures of the femoral stem and results of experimental loading tests. Acta Orthop Scand. 1974;45:693. doi: 10.3109/17453677408989679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee E.W., Kim H.T. Early fatigue failures of cemented, forged, cobalt-chromium femoral stems at the neck-shoulder junction. J Arthroplasty. 2001;16:236. doi: 10.1054/arth.2001.20542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galante J.O. Causes of fractures of the femoral component in total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1980;62:670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Della Valle A.G., Becksac B., Anderson J. Late fatigue fracture of a modern cemented [corrected] cobalt chrome stem for total hip arthroplasty: a report of 10 cases. J Arthroplasty. 2005;20:1084. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2005.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morgan-Hough C.V., Tavakkolizadeh A., Purkayastha S. Fatigue failure of the femoral component of a cementless total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2004;19:658. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morley D., Starks I., Lim J. A case of a C-stem fracture at the head-neck junction and a review of the literature. Case Rep Orthop. 2012;2012:158604. doi: 10.1155/2012/158604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ritter M.A., Campbell E.D. An evaluation of Trapezoidal-28 femoral stem fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1986;212:237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carlsson A.S., Gentz C.F., Stenport J. Fracture of the femoral prosthesis in total hip replacement according to Charnley. Acta Orthop Scand. 1977;48:650. doi: 10.3109/17453677708994812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vatani N., Comando D., Acuna J., Prieto D., Caviglia H. Faulty design increases the risk of neck fracture in a hip prosthesis. Acta Orthop Scand. 2002;73:513. doi: 10.1080/000164702321022776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Unnanuntana A., Chen D.X., Unnanuntana A., Wright T.M. Trunnion fracture of the anatomic medullary locking a plus femoral component. J Arthroplasty. 2011;26:504.e13-6. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2010.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burstein A.H., Wright T.M. Neck fractures of femoral prostheses. A report of two cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1985;67:497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gilbert J.L., Buckley C.A., Jacobs J.J., Bertin K.C., Zernich M.R. Intergranular corrosion-fatigue failure of cobalt-alloy femoral stems. A failure analysis of two implants. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1994;76:110. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199401000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grivas T.B., Savvidou O.D., Psarakis S.A. Neck fracture of a cementless forged titanium alloy femoral stem following total hip arthroplasty: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep. 2007;1:174. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-1-174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rand J.A., Chao E.Y. Femoral implant neck fracture following total hip arthroplasty. A report of three cases. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987;221:255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allcock S., Ali M.A. Early failure of a carbon-fiber composite femoral component. J Arthroplasty. 1997;12:356. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(97)90038-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Banerjee S., Cherian J.J., Bono J.V. Gross trunnion failure after primary total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30:641. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2014.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Botti T.P., Gent J., Martell J.M., Manning D.W. Trunion fracture of a fully porous-coated femoral stem. Case Report. J Arthroplasty. 2005;20:943. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2005.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aspenberg P., Kolmert L., Persson L., Onnerfalt R. Fracture of hip prostheses due to inadequate welding. Acta Orthop Scand. 1987;58:479. doi: 10.3109/17453678709146382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Magnissalis E.A., Zinelis S., Karachalios T., Hartofilakidis G. Failure analysis of two Ti-alloy total hip arthroplasty femoral stems fractured in vivo. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2003;66:299. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.10003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lam L.O., Stoffel K., Kop A., Swarts E. Catastrophic failure of 4 cobalt-alloy Omnifit hip arthroplasty femoral components. Acta Orthop. 2008;79:18. doi: 10.1080/17453670710014707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cooper H.J., Della Valle C.J., Berger R.A. Corrosion at the head-neck taper as a cause for adverse local tissue reactions after total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94:1655. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.K.01352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jacobs J.J., Cooper H.J., Urban R.M., Wixson R.L., Della Valle C.J. What do we know about taper corrosion in total hip arthroplasty? J Arthroplasty. 2014;29:668. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2014.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lachiewicz P.F., O'Dell J.A. Trunnion corrosion in metal-on-polyethylene hip arthroplasty. Bone Joint J. 2018;100-B:898. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.100B7.BJJ-2017-1127.R2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fokter S.K., Rudolf R., Molicnik A. Titanium alloy femoral neck fracture--clinical and metallurgical analysis in 6 cases. Acta Orthop. 2016;87:197. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2015.1047289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shah R.R., Goldstein J.M., Cipparrone N.E. Alarmingly high rate of implant fractures in one modular femoral stem design: a comparison of two implants. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32:3157. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2017.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gilbert J.L., Buckley C.A., Jacobs J.J. In vivo corrosion of modular hip prosthesis components in mixed and similar metal combinations. The effect of crevice, stress, motion, and alloy coupling. J Biomed Mater Res. 1993;27:1533. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820271210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.