Abstract

Background: Primary Immunodeficiencies (PIDs) are a heterogeneous group of genetic immune disorders. While some PIDs can manifest with more than one phenotype, signs, and symptoms of various PIDs overlap considerably. Recently, novel defects in immune-related genes and additional variants in previously reported genes responsible for PIDs have been successfully identified by Next Generation Sequencing (NGS), allowing the recognition of a broad spectrum of disorders.

Objective: To evaluate the strength and weakness of targeted NGS sequencing using custom-made Ion Torrent and Haloplex (Agilent) panels for diagnostics and research purposes.

Methods: Five different panels including known and candidate genes were used to screen 105 patients with distinct PID features divided in three main PID categories: T cell defects, Humoral defects and Other PIDs. The Ion Torrent sequencing platform was used in 73 patients. Among these, 18 selected patients without a molecular diagnosis and 32 additional patients were analyzed by Haloplex enrichment technology.

Results: The complementary use of the two custom-made targeted sequencing approaches allowed the identification of causative variants in 28.6% (n = 30) of patients. Twenty-two out of 73 (34.6%) patients were diagnosed by Ion Torrent. In this group 20 were included in the SCID/CID category. Eight out of 50 (16%) patients were diagnosed by Haloplex workflow. Ion Torrent method was highly successful for those cases with well-defined phenotypes for immunological and clinical presentation. The Haloplex approach was able to diagnose 4 SCID/CID patients and 4 additional patients with complex and extended phenotypes, embracing all three PID categories in which this approach was more efficient. Both technologies showed good gene coverage.

Conclusions: NGS technology represents a powerful approach in the complex field of rare disorders but its different application should be weighted. A relatively small NGS target panel can be successfully applied for a robust diagnostic suspicion, while when the spectrum of clinical phenotypes overlaps more than one PID an in-depth NGS analysis is required, including also whole exome/genome sequencing to identify the causative gene.

Keywords: primary immunodeficiencies, Next Generation Sequencing, gene panels, Ion Torrent, Haloplex

Introduction

Primary immunodeficiencies (PIDs) are a phenotypically and genetically heterogeneous group of more than 300 monogenic inherited disorders resulting in immune defects that predispose patients to infections, autoimmune disorders, lymphoproliferative disease, and malignancies (1–3). PIDs with a more severe phenotype lead to life-threatening infections and life-limiting complications that require a prompt and accurate diagnosis in order to initiate lifesaving therapy (4, 5). Phenotypic and genotypic heterogeneity of PIDs make genetic diagnosis often complex and delayed. Indeed, more than one genotype might cause similar clinical phenotypes, but identical genotypes will not often produce the same phenotype and finally clinical penetrance may be different (6–9). The characterization of PID-associated genes is expected to significantly contribute to define the molecular events governing immune system development and will provide new insights into the pathogenesis of PIDs. Molecular genetic testing is also a useful tool for the diagnosis of PIDs in atypical cases (6, 10).

Despite the progress in the genetic characterization of PIDs, many patients still lack a molecular diagnosis. A better understanding of the genetic and immune defects of patients is critical to develop therapeutic strategies aimed at changing the clinical course of the disease and to guarantee an appropriate genetic counseling allowing the identification of PID patients before the onset of the disease (11–13). The application of Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) to PIDs has been a revolution and it has accelerated the discovery and identification of novel disease-causing genes and the genetic diagnosis of patients with monogenic inborn errors of immunity (7, 8, 14–16). Targeted gene-panel sequencing (17–21), whole exome sequencing (WES) (22, 23) or whole genome sequencing (WGS) (24) approaches can rapidly identify candidate gene variants in an increasing number of genetically undefined diseases (17, 24) and are widely used in several laboratories for the diagnosis of PIDs (10). WGS also offers the opportunity to find causative variants in the structural regions of a given gene. These tools increase the amount of data analysis that can identify causative genes in both clinically defined and atypical diseases. Nonetheless, delay in diagnosis can be caused by the huge amount of data retrieved from whole sequencing, increased costs sustained by clinical laboratories and the requirement of trained personnel to validate variants (7, 8, 22). An increased depth of the sequencing coverage is generally obtained using targeted gene panels, in favor of a high accuracy, amelioration of sensitivity and management of datasets, reducing the time of analysis, the costs and the interpretation of results, thus accelerating the diagnosis for the majority of PIDs (14, 16–18). On the other hand, the usefulness of targeted exome sequencing approach for the identification of PID patients has been demonstrated, with accurate detection of point mutations and exonic deletions in patients with either known or unknown genetic diagnosis (7, 8).

In this study, we report the clinical and molecular characterization of 105 PID patients presenting with either typical SCID/CID or with overlapping PID phenotypes. Differently from other studies (20, 21, 25), most patients enrolled in this work had non-consanguineous parents. Two targeted sequencing approaches were compared to test the ion torrent reliability in diagnostics and Haloplex Target Enrichment System in diagnostics and for research purposes. Three diagnostic panels including known disease genes had been developed for the Ion Torrent platform (ThermoFisher). The Haloplex panels comprised well-defined PID genes (>300) and candidate genes associated with PIDs due to their expression and function in critical immune-pathways (1, 3). This work underlines how targeted NGS panels allow a high-throughput low-cost pipeline to identify the molecular bases of PIDs and are sensitive and accurate diagnostic tools for simultaneous mutation screening of known or putative PID-related genes.

Materials and Methods

Patients

We report the clinical and molecular characterization of 105 PID patients mainly referred to three centers (2 in Rome and 1 in Milan) participating in the Italian network of PIDs (IPINET) and part of The European Reference Network on immunodeficiency, autoinflammatory, and autoimmune diseases (ERN RITA). Nine of these patients have been enrolled in the pCID study (DRKS00000497). Data were obtained from year 2014 to 2017.

Ion Torrent and/or Haloplex panels were applied for the analysis of samples and compared. Six patients previously diagnosed by Sanger sequencing were included in the study (Table 2A) as internal positive controls. The Ion Torrent panels were used for the analysis of 73 patients with suspicion of PID. Among this group, 18 patients, still remaining without a molecular diagnosis and 32 additional patients, were tested by Haloplex panels (Target Enrichment System for Illumina platform). The work was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent, approved by the Ethical Committee of the Children's Hospital Bambino Gesù, San Raffaele Hospital (TIGET06, TIGET09) and Policlinico Tor Vergata, was obtained from either patients or their parents/legal guardians, if minors. Patients and their clinical and immunological features are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical, immunological and molecular features of PID patients.

| PID ID | AGE AT PRESENTATION | GENDER | ADMITTING CLINICAL DIAGNOSIS | NGS PLATFORM | GENETIC DIAGNOSIS | NEUTRAL VARIANTS AND VUS | OPPORTUNISTIC/RECURRENT INFECTIONS | IMMUNEDYSREGULATION/ MALIGNANCIES/ OTHERS | IMMUNOPHENOTYPE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PID 1 | BIRTH | M | OMENN SYNDROME | ION TORRENT PANEL 1 | RAG1 | CHRONIC CMV VIREMIA, PNEUMOCYSTOSIS, HERPETIC KERATITIS | TUBULE INTERSTITIAL NEPHRITIS WITH LYMPHO-MONOCYTE INFILTRATE | T+, B-, NK+ | |

| PID 2 | 2 mo | M | SCID | ION TORRENT PANEL 1 | RAG2 | EBV AND ADENOVIRUS POST HSCT | T+ (↓CD4 , ↓CD8), B-, ↑NK, ↓IgM, ↓IgA | ||

| PID 3 | 5 mo | F | SCID | ION TORRENT PANEL 1 | RAG2 | ADENOVIRUS | T-, B-, NK+ | ||

| PID 4 | 2mo | M | SCID | ION TORRENT PANEL 1 | RAG1 | CHRONIC CMV VIREMIA | T+, B-, NK+, ↓IgM | ||

| PID 5 | 5mo | M | SCID | ION TORRENT PANEL 1 | IL2RG | ADENOVIRUS, HEPATITIS, ENTEROBACTHER CLOACAE; CANDIDA | DERMATITIS (BOLLOUS TYPE) | T-, B-,↑NK | |

| PID 6 | 4mo | M | SCID | ION TORRENT PANEL 1 | JAK3 | INTERSTITIAL PNEUMONIA, PNEUMOCYSTOSIS | T-, B+, NK-, HYPGAMMAGLOBULINEMIA | ||

| PID 7 | 4mo | M | SCID | ION TORRENT PANEL 1-2 | INTERSTITIAL LUNG DISEASE; URI; LRI | HEPATOSPLENOMEGALY, AIHA, ITP | T+ (ABSENT NAIVE and RTE, ↑γδ), B+, NK+ | ||

| PID 8 | 1 y | M | SCID | ION TORRENT PANEL 1-2 | HEPATOSPLENOMEGALY, AIHA, ITP, VERTEBRAL WEDGING AND OSTEOPENIA | T (ABSENT NAIVE and RTE, ↑γδ), B+(↑UNSWITCHED MEMORY), NK+ | |||

| PID 9 | 9mo | F | SCID | ION TORRENT PANEL 1-2 | GLUTEAL ABSCESS | CHRONIC DIARRHEA | T+ (↑CM CD4 , ↑γδ), B-, NK- | ||

| PID 10 | 2mo | F | SCID | ION TORRENT PANEL 1-2 | POST-NATAL CMV INFECTION; URI;LRI; NEONATAL SEPSIS | T+, B (ABSENT SWITCHED MEMORY), NK+ | |||

| PID 11 | na | F | SCID | ION TORRENT PANEL 1-2 | CHRONIC VZV VIREMIA | THROMBOCYTOPENIA | T- (↓ CD4), B+, NK+ | ||

| PID 12 | 1y | M | SCID | ION TORRENT PANEL 1-2/ HALOPLEX PANEL 2 | ADA | URI | T-, B-, NK+ | ||

| PID 13 | 2y | M | SCID | ION TORRENT PANEL 1-2/ HALOPLEX PANEL 2 | CECR1 | PENUMONIA; CANDIDIASIS | GASTROENTERITIS, HyperIgE; LYELL SYNDROME, CARDIAC ARREST OF UNKNOWN ORIGIN; ILEOILEAL INTUSSUSCEPTION | LOW T, B-, ↑NK+, ↑IgM, ↓IgA, ↑IgE | |

| PID 14 | 5mo | M | SCID | ION TORRENT PANEL 1-2 | CHRONIC CMV AND EBV VIREMIA | ↓T (ABSENT NAIVE CD4 and CD8, ↑γδ), B+, ↑NK | |||

| PID 15 | 1y | F | SCID | ION TORRENT PANEL 1-2 | ADA | LRI | T-, B-, NK+, ↓IgM | ||

| PID 16 | 8 mo | M | leaky SCID | ION TORRENT PANEL 1-2 | IL2RG | CHRONIC CMV VIREMIA, SEVERE CMV INTERSTITIAL PNEUMONIA | PNEUMONIA, DERMATITIS, GROWTH FAILURE | T+/-, B-, NK+ | |

| PID 17 | 1y | M | SCID | ION TORRENT PANEL 1 | IL2RG | CHRONIC CMV VIREMIA, BRONCHIOLITIS, UTI, ROTAVIRUS ENTERITIS | HEPATOSPLENOMEGALY, HLH | ↓T (ABSENT NAIVE CD4 and CD8), B-, NK+ | |

| PID 18 | 4d (DIED) | M | SCID | ION TORRENT PANEL 1 | IL2RG | CMV, PNEUMOCYSTIS JIROVECI PNEUMONIA | T-, B+, ↓NK | ||

| PID 19 | 5mo | M | SCID | ION TORRENT PANEL 1 | IL2RG | STAPHYLOCOCCUS HAEMOLYTICUS; ASPERGILLUS, BCGITIS | T-, ↑B+, ↓NK+, ↓IgM, ↓IgA | ||

| PID 20 | 1.8y | F | SCID | ION TORRENT PANEL 1-2 | RAG1 | LTI | HEPATOSPLENOMEGALY | T-, B-, NK+, ↑IgG, ↓IgM, ↓IgA, ↓IgE | |

| PID 21 | 1y | M | SCID | ION TORRENT PANEL 1-2 | CD3D | RHINOVIRUS, MYCOBACTERIUM | T (↓NAIVE CD4, ABSENT CD8, ↑γδ), B+, NK+ | ||

| PID 22 | 1.3y | M | SCID | ION TORRENT PANEL 1 | RAG1 | LRI, ADENOVIRUS, ROTAVIRUS ENTERITIS, PSEUDOMONAS AERUGINOSA | T-, B-, NK+, ↓IgM, ↓IgA, ↓IgE | ||

| PID 23 | 11mo | F | SCID | ION TORRENT PANEL 1 | JAK3 | CHRONIC HHV-6 VIREMIA, CANDIDA ALBICANS, ROTAVIRUS, CORONAVIRUS 229E, | T-, B+, ↑NK, ↓IgG, ↓IgM, ↓IgA | ||

| PID 24 | 4mo | F | SCID | ION TORRENT PANEL 1 | JAK3 | LRI, CANDIDA ALBICANS, RHINOVIRUS | T-, B+, ↑NK, ↓IgE | ||

| PID 25 | na | M | SCID | HALOPLEX PANEL 1 | IL7R | na | na | T-, B+, NK+ | |

| PID 26 | 1y | M | CID | HALOPLEX PANEL 1 | AIHA | T-, B-, NK+, ↓IgM, ↓IgA | |||

| PID 27 | 5 | F | CID | ION TORRENT PANEL 1-2/ HALOPLEX PANEL 1 | IR, EPIDERMODYSPLASIA VERRUCIFORMIS (HPV-8 WARTS); URI | MILD MYELODYSPLASIA, SEVERE HEPATIC STEATOSIS | T (↓NAIVE and ↓RTE), B+, NK+ | ||

| PID 28 | 3 | F | CID | ION TORRENT PANEL 1-2/ HALOPLEX PANEL 1 | CHRONIC EBV VIREMIA, URI, PNEUMONIA | ENTEROPATHY; CHRONIC-PANCREATITIS; ANA/ANCA+ | T (↓NAIVE), B+, NK+ | ||

| PID 29 | 1 y | M | CID | ION TORRENT PANEL 1 | RAG1 | CHRONIC CMV AND EBV VIREMIA, HAEMOPHILUS INFLUENZAE AND BOCAVIRUS RESPIRATORY INFECTION, LONG-LASTING ROTAVIRUS DIARRHEA | THROMBOCYTOPENIA, AHIA , SEVERE HEPATOSPLENOMEGALY, WITH LIVER FAILURE | ↓T, B+, NK+, ↑IgE, ↑IgM, ↑IgG | |

| PID 30 | 3 | M | CID | ION TORRENT PANEL 1-2 | URI | DERMATITIS; ANA+ | ↓T (↓NAIVE CD4), B+, NK+ | ||

| PID 31 | 3 | F | CID | ION TORRENT PANEL 1 | RAG1 | CHRONIC HHV-6, CMV,EBV VIREMIA; URI, LRI | AHIA | T+, ↓ B, NK+, ↓IgM, ↓IgA | |

| PID 32 | 3y | F | CID | ION TORRENT PANEL 1-2/ HALOPLEX PANEL 1 | CHRONIC EBV VIREMIA, URI | HODGKIN LYMPHOMA; ENTEROPATHY | T (↓NAIVE), B-, NK+ | ||

| PID 33 | 10y | M | CID | ION TORRENT PANEL 2 | CHRONIC EBV VIREMIA, URI-LRI | LYMPHADENOPATHY, URTICARIA, LONG-COURSE DIARROHEA /LYMPHATIC HYPERPLASIA | T+, B-, NK+ | ||

| PID 34 | 1y | F | CID | ION TORRENT PANEL 1 | SEVERE DERMATITIS, DIARRHEA, INTERSTITIOPATHY | T (↓CD8), ↑B+, NK+ | |||

| PID 35 | 11y | F | CID | HALOPLEX PANEL 1 | COLITIS, GH DEFICIENCY | LYMPHOPENIA, ↓T, ↓B, ↓NK (UNDER AZA) | |||

| PID 36 | 15 mo | F | CID | ION TORRENT PANEL 1-2 | IL7R | CHRONIC EBV VIREMIA, URI (recurrent) | THROMBOCYTOPENIA,SEVERE DERMATITIS, GROWTH RETARDATION, | HYPERGAMMAGLOBULINEMIA (maternal engraftment) | |

| PID 37 | 1mo | M | CID | HALOPLEX PANEL 2 | ARPC1B | WARTS, RECURRENT INFECTIONS | VASCULITIS, LYMPHADENOPATHY, ECZEMA, HYPOGAMMAGLOBULINEMIA, HYPER IgE, THROMBOCYTOPENIA, LUNG DISEASE, BRONCHIECTASIS | ↓T, B+, ↓NK, ↓IgG , ↓IgM, ↑IgA, ↑IgE | |

| PID 38 | 0.8y | M | CID | HALOPLEX PANEL 2 | NFKB1 | RECURRENT ESOPHAGEAL CANDIDIASIS, LUNG ABSCESS | ESOPHAGEAL ATRESIA | T+, B+, NK+ | |

| PID 39 | 13 mo | F | CID | HALOPLEX PANEL 1 | RAG1 | RECURRENT BRONCHITIS | SEVERE AUTOIMMUNE HEMOLITIC ANEMIA, INTERSTITIAL PNEUMOPATHY AND BRONCHIECTASIS | T+, B+, NK+ | |

| PID 40 | na (adopted 11y) | F | CID | HALOPLEX PANEL 1 | RECURRENT HERPETIC INFECTIONS (STOMATITIS) | ↓T, ↓B, NK+ | |||

| PID 41 | 18 mo | F | CID | HALOPLEX PANEL 1 | RECURRENT RESPIRATORY INFECTIONS AND OTITIS, POSITIVE HCV | HODGKIN LYMPHOMA, OBSTRUCTIVE LUNG DISEASE | ↓T (↓CD4), B-, ↑IgM, ↓IgG, ↓IgA | ||

| PID 42 | 1d | F | SYNDROMIC T-CELL DEFECT | ION TORRENT PANEL 1-2/ HALOPLEX PANEL 1 | POST SURGICAL SEPSIS | CHDs, OSTEOMYELITIS | T-, B+, NK+ | ||

| PID 43 | 8y | M | SYNDROMIC T-CELL DEFECT | ION TORRENT PANEL 1-2 | URI, NEONATLA SEPSIS | ATOPY, CHDs | T+, B-, NK+ | ||

| PID 44 | 4y | M | SYNDROMIC T-CELL DEFECT | ION TORRENT 1-2/ HALOPLEX PANEL 1 | URI; SINUSITIS | MALFORMATIVE SYNDROME; PSYCHOMOTOR RETARDATION | T+, ↓B, NK+ | ||

| PID 45 | 13y | M | UNCLASSIFIED T-CELL DEFICIENCY | ION TORRENT PANEL 2/HALOPLEX PANEL 2 | CHRONIC EBV VIREMIA, PNEUMONIA | HEPATOSPLENOMEGALY, LYMPHOADENOPATY; NEPHROTIC SYNDROME | T (↓NAIVE CD4, CD8, RTE), ↓B, NK+, ↑IgM, ↓IgA | ||

| PID 46 | 3y | M | UNCLASSIFIED T-CELL DEFICIENCY | ION TORRENT PANEL 1-2/HALOPLEX PANEL 1 | CHRONIC EBV VIREMIA, URI, LRI | PULMONARY NLH | T (↓NAIVE CD4, AND CD8), ↑B, ↑NK | ||

| PID 47 | 8y | M | UNCLASSIFIED T-CELL DEFICIENCY | ION TORRENT PANEL 1-2 | CHRONIC EBV VIREMIA, URI, UTI | GASTROENTERITIS, ATOPIC DERMATITIS | T+ (↑CD4 CM) B+ NK+ | ||

| PID 48 | 5y | M | UNCLASSIFIED T-CELL DEFICIENCY | ION TORRENT PANEL 1-2 | AIHA; VASCULITIS, APHTOSIS | T (↓CD4) ↓B+ ↑NK | |||

| PID 49 | 6y | M | HIGM | ION TORRENT PANEL 1-2 | CD40LG | CRYPTOSPORIDIUM | CHRONIC GASTRITIS,SCLEROSIS CHOLANGITIS | T+, B+(↓ SWITCHED MEMORY), NK+ | |

| PID 50 | 2y | M | HIGM | ION TORRENT PANEL 1 | CD40LG | CHRONIC EBV VIREMIA | NEPHROTIC SYNDROME,PSYCHOMOTOR DELAY, LEUKODYSTROPHY | T+ (↑CD8 EM), B+(↓ SWITCHED MEMORY), NK+ | |

| PID 51 | 10y | M | AGAMMAGLOBULINEMIA | ION TORRENT PANEL 1 HALOPLEX PANEL 1 | RAG1 | CHRONIC EBV VIREMIA, URI | NASAL POLYPOSIS, CHRONIC BRONCOPNEUMOPATHY | T+, VERY ↓B, NK+, ↓IgM, ↓IgG, ↓IgA | |

| PID 52 | 14y | M | CVID | ION TORRENT PANEL 1-2-3/ HALOPLEX PANEL 2 | URI, PNEUMONIA | CHRONIC BRONCOPNEUNOPATY, BRONCHIECTASIS, GROWTH RETARDATION | T+(↓ NAIVE CD4 and CD8), ↓B (↓ SWITCHED MEMORY) , NK+, ↓IgM, ↓IgG, ↓IgA | ||

| PID 53 | 1y | F | CVID | ION TORRENT PANEL 1-2-3 | UTI, PNEUMONIA | ATOPY | T+ (↑CD8 EM EMRA), ↓B (↓ SWITCHED MEMORY) , NK+, ↓IgG, ↓IgA | ||

| PID 54 | 5y | F | CVID | ION TORRENT PANEL 1-2-3 | PLCG2 | URI, PARASITE INFECTION (OXYURIASIS) | T+ B+ NK+, ↓IgM, ↓IgA | ||

| PID 55 | 7y | M | CVID | ION TORRENT PANEL 1-2-3 | URI | GASTROENTERITIS | T+ (↑CD8), B+, NK+, ↓IgM, ↓IgG, ↓IgA | ||

| PID 56 | 14y | F | CVID | ION TORRENT PANEL 1-2-3 | CTLA4 + PTEN | URI | T+ (↑CM, ↑THF, ↓TREG) B+ (↑NAIVE, ↓SWITCHED MEMORY, ↑AUTOREACTIVE B cells) NK+, ↓IgA | ||

| PID 57 | 1y | M | CVID | HALOPLEX PANEL 2 | TNFRSF13B*+ TCF3 | URI | NON-SPECIFIC COLITIS, NF1 | T+ (↑CD4 CM), B+, NK+, ↓IgM, ↓IgG, ↓IgA | |

| PID 58 | 1y | M | CVID | ION TORRENT PANEL 1/HALOPLEX PANEL 2 | TNFRSF13B*+ TCF3 | URI | NON-SPECIFIC COLITIS, NF1, ARTHITIS | T+ (↑CD4 CM), B+, NK+, ↓IgM, ↓IgG, ↓IgA | |

| PID 59 | 5y | M | CVID | ION TORRENT PANEL 1-2-3 | CHRONIC EBV VIREMIA, PNEUMONIA | T+ (↑γδ) B+,NK+, ↓IgA | |||

| PID 60 | 12y | F | CVID | HALOPLEX PANEL 2 | CHRONIC EBV VIREMIA, URI, PNEUMONIA, WARTS | T+, ↓B, NK+, ↓IgA | |||

| PID 61 | 9mo | M | CVID | HALOPLEX PANEL 2 | TNFRSF13B* | URI, LRI, HHV6 | GASTROENTERITIS,ESSENTIAL ARTERIAL HYPERTENSION, ARNOLD-CHIARI SYNDROME TYPE I, GLICOSURIA, PSYCHOMOTOR DELAY | T+, B+(↓ SWITCHED MEMORY) NK+, ↓IgA | |

| PID 62 | 2y | M | CVID | HALOPLEX PANEL 2 | CHRONIC DIARRHEA, GASTROENTERITIS | T+ B+ (↑IgM MEMORY), NK+, HYPOGAMMAGLOBULINEMIA | |||

| PID 63 | 2y | M | CVID | HALOPLEX PANEL 2 | UTI, LTI | MILD NEURODEVELOPMENTAL DELAY; DYSGENESIS OF THE CORPUS CALLOSUM; ARACHNOID CYST, MILD THROMBOCYTOPENIA | T+, LOW B, NK+ ↓IgM, ↓IgA | ||

| PID 64 | 11y | M | CVID | ION TORRENT PANEL 1-2-3 | T+ (↑CD4 CM), B+(LOW SWITCHED MEMORY), NK+, ↓IgM, ↓IgG, ↓IgA | ||||

| PID 65 | 2y | F | CVID | ION TORRENT PANEL 1-2-3 | UTI, LTI (PNEUMOCOCCUS), | ECZEMATOUS DERMATITIS; GENERALIZED LYMPHADENOPATHY; HEPATOSPLENOMEGALY, GLILD | T+ (↓NAIVE CD4, ↑ EM CD8), B+(ABSENT MEMORY), NK+, ↓IgM, ↓IgG, ↓IgA | ||

| PID 66 | 3mo | F | CVID | ION TORRENT PANEL 1-2-3 | URI; LRI; SEPSI | CANDIDA ENTERITIS,MALFORMATIVE SYNDROME, PSYCHOMOTOR RETARDATION, CHDs;CGH ARRAY: 15q25.1 DUPLICATION | T+ (↑EMRA CD4), B+, NK+, ↓IgM, ↓IgA | ||

| PID 67 | 15y | M | CVID | HALOPLEX PANEL 1 | SALMONELLA OSTEOMIELYTIS | LINFOADENOPATHY, SPLENOMEGALY, AHA„ITP | T+, B+, NK+, HYPOGAMMAGLOBULINEMIA | ||

| PID 68 | 6y | M | CVID | HALOPLEX PANEL 2 | LINFOADENOPATHY, SPLENOMEGALY, AHA, ITP, PULMONARY INFILTRATES, BRONCHIECTASIS | T+, B+, NK+, IgA-, IgG- | |||

| PID 69 | 1y | M | CVID | HALOPLEX PANEL 2 | RECURRENT VZV, RECURRENT INFECTIONS | URTICARIA, ANGIOEDEMA, LUNG FIBROSIS | T+, B+, NK+, IgA ↓, IgG ↓ | ||

| PID 70 | 15y | M | CVID | HALOPLEX PANEL 2 | TNFRSF13B | RECURRENT INFECTIONS | LINFOADENOPATHY, SPLENOMEGALY,HYPOTHYROIDISM, LUNG NODULAR INFILTRATES, GROUND GLASS | T+, B+, NK+, IgM ↓ | |

| PID 71 | 12y | F | CVID | HALOPLEX PANEL 2 | RECURRENT PNEUMONIA | T+, B+, NK+, HIPER IgG | |||

| PID 72 | 13y | M | CVID | HALOPLEX PANEL 1 | PULMONARY NODULES | T+, B+, NK+, IgG-, IgM-, IgA- | |||

| PID 73 | 10y | M | SELECTIVE IgM DEFICIENCY | ION TORRENT PANEL 1-2-3 | SEPSI; URI, LRI | GASTROENTERITIS; HEPATOSPLENOMEGALY | T+ (↑γδ), B+ ↓ MEMORY), NK+, ↓IgM | ||

| PID 74 | 12y | F | HYPERIGG4 | HALOPLEX PANEL 2 | T+, B+, NK+, ↑IgG4 | ||||

| PID 75 | 2y | M | UNCLASSIFIED ANTIBODY IMMUNODEFICIENCY | ION TORRENT PANEL 1-2-3 | TCF3 | ATYPICAL MYCOBACTERIOSIS (M.AVIUM) | BRONCHIAL GRANULOMA | T+ (↑CD4), B+, ↓NK+, ↓IgA | |

| PID 76 | 5y | M | UNCLASSIFIED ANTIBODY IMMUNODEFICIENCY | ION TORRENT PANEL 1-3/HALOPLEX PANEL 2 | CHRONIC HHV-6 VIREMIA, URI; PNEUMONIA; MOLLUSCUM CONTAGIOSUM | DERMATITIS | T+ (↑NAIVE CD4, ↑LATE EFFETOR CD8, ↓THF, ↓TREG) B+ (↓MEMORY, ↑TRANSITIONAL), NK+ | ||

| PID 77 | 6y | F | UNCLASSIFIED ANTIBODY IMMUNODEFICIENCY | ION TORRENT PANEL 1-2-3/ HALOPLEX PANEL 2 | NOD2 | CHRONIC CMV AND HHV-6 VIREMIA | BURKITT LYMPHOMA, EBV-REACTIVATION, CMV PRIMARY INFECTION | T+ (LOW NAIVE CD8), B+ (LOW MEMORY), ↑IgM, ↓IgG, ↓IgA | |

| PID 78 | 12y | M | UNCLASSIFIED ANTIBODY IMMUNODEFICIENCY | ION TORRENT PANEL 1-2-3/HALOPLEX PANEL 2 | CHRONIC EBV VIREMIA | THROMBOCYTOPENIA; GASTROENTERITIS | T+, B+ (↓ IgM MEMORY AND ↓SWITCHED MEMORY), NK+, ↓IgM, ↓IgA | ||

| PID 79 | 3y | M | UNCLASSIFIED SYNDROMIC DEFICIENCY | ION TORRENT PANEL 1-2-3 | THROMBOCYTOPENIA IMMUNOMEDIATED, CELIAC DISEASE | T+, B+, NK+, ↓IgA | |||

| PID 80 | 6y | F | IMMUNE DYSREGULATION | ION TORRENT PANEL 1 | URI, LRI, RECURRENT SKIN INFECTIONS | DERMATITIS, FEMORAL DYSPLASIA | T+ (↑NAIVE CD4), B+ (↓ MEMORY) , NK+ | ||

| PID 81 | 10y | M | IMMUNE DYSREGULATION | ION TORRENT PANEL 1-3/HALOPLEX PANEL 2 | AIRE*+ PLCG2 | URI | ALOPECIA; ONYCHODYSTROPHY | T+, ↓B+, NK+, ↓IgG, ↓IgA | |

| PID 82 | 2y | F | INNATE IMMUNE DISEASE | ION TORRENT PANEL 1-2/HALOPLEX PANEL 1 | MYD88/CARD9 | CHRONIC EBV, HHV-6, CMV VIRMEMIA, URI; UTI; PBI | INGUINAL ABSCESS; GRANULOMATOUS LYMPHADENITIS | T+ B+ NK+ | |

| PID 83 | 3y | M | NEUTROPENIA | HALOPLEX PANEL 2 | JAGN1 | CHRONIC EBV VIREMIA, LRI,URI | APHTOSIS | T+, B+ (↓ IgM MEMORY and ↓SWITCHED MEMORY), NK+, ↑IgA | |

| PID 84 | 1y | F | NEUTROPENIA | HALOPLEX PANEL 2 | CECR1 | RECURRENT INFECTIONS | SEVERE NEUTROPENIA | T+, B+, NK+, NEUTROPENIA | |

| PID 85 | 5y | F | NEUTROPENIA | HALOPLEX PANEL 2 | CARDIOPATHY, NEUTROPENIA, NEUROLOGICAL DELAY, LIGAMENT LAXITY | T+, B+, NK+, NEUTROPENIA | |||

| PID 86 | 13d | M | ALPS-LIKE | HALOPLEX PANEL 1 | NRAS | URI | THROMBOCYTOPENIA; SPLENOMEGALY | T+ (↑CD4 CM, ↓RTE, ↑CD8 EM and ↑EMRA), B+(↓SWITCHED MEMORY), NK+ | |

| PID 87 | 3y | M | ALPS | HALOPLEX PANEL 2 | TNFRSF13B | GENITAL AND PERIANAL WARTS, TONSILLITIS, PNEUMONIA | AHA, ITP, LINFOADENOPATHY, SPLENOMEGALY, HYPOGAMMAGLOBULINEMIA, PULMONARY INFILTRATES | T+, B+, NK+, ↓IgG, IgM-, ↓IgA | |

| PID 88 | 8y | M | VEO-IBD | ION TORRENT PANEL 1 | XIAP | CHRONIC EBV AND HVV-6 VIREMIA, URI | ENTEROPATHY | T+, B- (↑CD8 EM and ↑EMRA), NK+ | |

| PID 89 | 4y | M | VEO-IBD | ION TORRENT PANEL 1 | CHRONIC EBV VIREMIA | ENTEROPATHY; CELIAC SPRUE | ↓T+, ↑B+, NK+ | ||

| PID 90 | 2y | M | VEO-IBD | ION TORRENT PANEL 1-2/HALOPLEX PANEL 2 | CHRONIC VZV VIREMIA, URI | CHRONIC DIARRHEA, CELIAC SPRUE | T+ (↓NAIVE CD4) B+ NK+ | ||

| PID 91 | 2mo | M | AUTOINFLAMMATORY SYNDROME | ION TORRENT PANEL 1-2 | HLH; HEPATOSPLENOMEGALY; SKIN RASH; SYSTEMIC INFLAMMATORY SYNDROME | CHRONIC DIARRHEA, MONOCYTOPENIA | T+ (↑CM CD4+ ↓ RTE), B+ (↑SWITCHED MEMORY B CELL, ↑PLASMABLAST ↑CD21LOW, ↓TRANSITIONAL B CELL), AND DC- | ||

| PID 92 | 13y | F | AUTOINFLAMMATORY SYNDROME | HALOPLEX PANEL 2 | SLE | T+, B+, NK+ | |||

| PID 93 | 5y | F | UNCLASSIFIED SYNDROMIC DEFICIENCY | ION TORRENT PANEL 1-2 | CHRONIC EBV VIREMIA, URI, PNEUMONIA | CHRONIC BRONCOPNEUNOPATY, MALFORMATIVE SYNDROME PSYCHOMOTOR DELAY | T+ (↑CM CD4+ ↑THF), B+ (↓ IgM MEMORY and ↓SWITCHED MEMORY), ↓ NK | ||

| PID 94 | 1y | M | UNCLASSIFIED SYNDROMIC DEFICIENCY | ION TORRENT PANEL 1-2 | CHRONIC EBV VIREMIA | LAMBERT EATON SYNDROME, GLIOMA, 5q- MYELODISPLASIA; PSYCHOMOTOR RETARDATION; POLYNEUROPATHY | T+ ↓B NK+ | ||

| PID 95 | 1.5y | M | UNCLASSIFIED SYNDROMIC DEFICIENCY | HALOPLEX PANEL 1 | BMP4 | URI, LRI | THROMBOCYTOPENIA, HYPERLAXITY, DENTAL ANOMALIES; DYSMORPHIC FEATURES; CRYPTORCHIDISM; SEVERE MYOPIA; ECTODERMAL DYSPALSIA SIGNS | T+, B+, NK+ | |

| PID 96 | 9y | M | SYNDROMIC | ION TORRENT PANEL 1-2 | URI, POLYALLERGY | INTERSTITIAL TUBULOPATHY; CHRONIC PANCREATITIS; CHRONIC GASTRODUODENITIS; MILD ESOPHAGITIS; BRONCOPNEUMOPATHY WITH BRONCHIECTASIAS. | T+ (↑CM CD4+ ↓ RTE), B+, NK+ | ||

| PID 97 | 4y | M | SYNDROMIC | ION TORRENT PANEL 1 | HYPOSURRENALISM; COATS DISEASE; MYELODYSPLASIA; HYPOSPADIAS; MONOSOMY CHR 7 | T+ (↑ CD4+), ↓B (↓TRANSITIONAL and ↑PLASMACELLS, NK+,↑IgA | |||

| PID 98 | 2y | M | ACUTE LIVER FAILURE | ION TORRENT PANEL 1-2 | CHRONIC EBV VIREMIA, TWO EPISODES OF ACUTE EPATITIS | GROWTH RETARDATION, IUGR | T(↑ CD4+), B+, ↓NK+ | ||

| PID 99 | 4y | M | HYPERSENSITIVITY | ION TORRENT PANEL 1 | LTI (RECURRENT BRONCHITIS), ORAL PAPILLOMATOSIS, ATOPIC DERMATITIS | FOOD ALLERGY | T+ (↑γδ), B+, NK+ | ||

| PID 100 | 16y | F | IMMUNE DYSREGULATION | HALOPLEX PANEL 1 | RECURRENT INFECTIONS | ENTEROCOLITIS | T+, B+, NK+ | ||

| PID 101 | 7y | F | IMMUNE DYSREGULATION | HALOPLEX PANEL 2 | WARTS, NAIL FUNGAL INFECTION (NOT RECURRENT) | ALOPECIA, AUTOIMMUNE THYROIDITIS, MILD LYMPHOPENIA | ↓T, B+, NK+ | ||

| PID 102 | na | M | OTHER (TROMBOCYTOPENIC PURPURA) | ION TORRENT PANEL 1-2 | HYPOSPADIAS, ITP | T+ (↑CM CD4+), B+, NK+ | |||

| PID 103 | 11y | M | OTHER | HALOPLEX PANEL 2 | ALOPECIA | T+, B+, NK+ | |||

| PID 104 | 13y | M | OTHER | HALOPLEX PANEL 2 | ITP | T+, B+, NK+, ↓IgG, ↓IgA | |||

| PID 105 | 4y | F | OTHER | HALOPLEX PANEL 2 | AUTOIMMUNE/AUTOINFLAMMATORY PHENOTYPE |

EBV, Epstein-Barr; CMV, Cytomegalovirus; VZV, Varicella-Zoster Virus; HHV-6, Human Herpesvirus 6; HPV, Human Papilloma Virus; URI, Upper Respiratory Infection; LRI, Lower Respiratory Infections; UTI, Urinary Tract Infection; SLE, Systemic Lupus Erythematosus; ITP, Idiopathic Thrombocytopenic Purpura; HLH, Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis; AIHA, Autoimmune Haemolytic Anemia; CHDs, Congenital Heart Disease ; NF1, Neurofibromatosis 1. ↓ low as compared to age matched normal range; ↑high as compared to age matched normal range.

Black Bold: Ion Torrent diagnosis. Blue Bold: Haloplex diagnosis. Different colors show genes in which we found: Violet

> Previous Sanger detections in predisposing gene variants to PID; Violet > predisposing gene variants to PID. Gray > no-causative disease variants; Green > variants of uncertain significance (VUS). Orange > variant in genes partially associated to the clinical phenotype.

Ion Torrent Target System

Panel Design

The construction of targeted panels design required the study of several reported clinical phenotypes of known PID genes described in the IUIS (International Union of Immunological Societies) in the years 2014–2015. Our three custom Ion Torrent panels were designed with Ampliseq Designer software using GRCh37 (panel 1 and 2) and GRCh38 (panel 3) as references. Primers were divided into two pools. The first custom panel (panel 1) contains 17 known genes related to SCID-CID phenotypes (85.85 kb). The second custom panel (panel 2) includes 24 genes for less frequent CID phenotypes (101.9 kb) and the third panel (panel 3) includes 62 genes for CVID (240.01 kb) (Supplementary Tables S1–S3). The final design was expected to cover 95.43% of the first panel, 94.13% of the second panel and 97.2% of the third genes panel. For each gene included in the panels a 10 bp of exon padding was included to cover the flanking regions of exon's coding sequences (CDS) including (panel 1 and 2) or not (panel 3) the untranslated regions (UTRs).

Ion Torrent Gene Target Library Preparation and NGS Sequencing

DNA was extracted by QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen). Five nanograms of gDNA were used for library preparation. DNA was amplified with 17 amplification cycles using gene panel Primer Pools and AmpliSeq HiFi mix (Thermo Fisher). PCR pools for each sample were combined and subjected to primer digestion with FuPa reagent (Thermo Fisher). Libraries were indexed using the Ion Xpress Barcode Adapter Kit. After purification, the amplified libraries were quantified with Qubit® 2.0 Fluorometer. All samples were diluted at a final concentration of 100 pM, then amplicon libraries were pooled for emulsion PCR (ePCR) on an Ion OneTouch System 2TM using the Ion PGM Template OT2 200 kit or Ion Chef according to manufacturer's instructions. Quality control of all libraries was performed on Qubit® 2.0 Fluorometer. Ampliseq Design Samples were subjected to the standard ion PGM 200 Sequencing v2 protocol using Ion 316 v2 chips or Ion S5 using Ion 520 v2 chips (Life Technologies).

Ion Torrent Bioinformatics Analysis, Variants Filtering, and Assessment of Pathogenicity

Mapping and variants calling were performed using the Ion Torrent suite software v3.6. Sequencing reads were aligned on GRCh37 (panel 1 and 2) and GRCh38 (panel 3) reference genome using the program distributed within the Torrent mapping Alignment Program (TMAP) map4 algorithm (Thermo Fisher; https://github.com/Ion Torrent/TS). The alignment step is limited only to the regions of target genes. BAM files with aligned reads were processed for variant calling by Torrent Suite Variant Caller TVC program and variants in Variant Calling Format (VCF) file were annotated with ANNOVAR. Called variants with minimum coverage of 30X, standard Mapping Quality and Base Phred Quality were examined on Integrative Genome Viewer (IGV) and BIOMART. Filtering procedures selected variants with a minor allele frequency (MAF) < 2% annotated using the following public databases: 1000 Genomes Project (2500 samples; http://www.1000genomes.org/), the Exome Variant Server (ESP) (6500 WES samples; http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/) and the Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC) (60,706 samples; http://exac.broadinstitute.org/). Nonsense, frame-shift, start lost, stop lost, and canonical splice site variants were considered potentially pathogenic (6). In silico prediction of functional consequences of novel SNV was performed using Mutation taster, LTR, Polyphen2, SIFT, and CADD score >15 (26–30) and literature available data. Supplementary Figure 1A summarizes all steps of the process.

Haloplex Target System

Panel Design

We designed two panels including up to 300 known PID genes (3) chosen from a Custom Gene Target Panel from Agilent SureDesign online tool (http://web16.kazusa.or.jp/rapid_original/) and about 300 candidate additional genes taken from the RAPID web site (http://rapid.rcai.riken.jp) from the RIKEN Center for Integrative Medical Science, from the literature and the ESID Online Registry. The candidate genes category includes genes that might be found in clinically relevant PID pathways and can share similar biological function of known PID genes. The first panel of 623 target genes comprised 7,245 regions with 66,600 amplicons, while the second panel of 601 target genes, included 6,984 regions and 73,061 amplicons. The designed probes capture 25 flanking bases in the coding exons regions (Supplementary Tables 4A,B). The final probe design was expected to cover >97% of target regions. Practical coverage is indicated.

Haloplex Gene Target Library Preparation and NGS Sequencing

Genomic DNA was extracted by QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen) and quantified by Qubit dsDNA BR Assay Kit (Thermofisher). DNA integrity was check by agarose gel (1% of agarose in TAE 1x). Genomic DNA was enriched with Haloplex Target Enrichment System kit (Agilent Technologies Inc., 2013, Waghäusel-Wiesental, Germany). Libraries were prepared according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, 225 ng of genomic DNA was enzymatically digested; fragments were hybridized with conjugated biotin probes for 16 h at 54°C. Circularized target DNA-Haloplex probe hybrids were captured with streptavidin-coated magnetic beads. DNA ligase was added to the capture reaction to close nicks in the circularized probe-target DNA hybrids. All DNA samples were individually indexed during the hybridization step and library PCR amplification was performed on the Mastercycler Nexus Thermal Cyclers (Life Sciences Biotechnology, Hamburg, Germany). Amplicons were purified with AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter, Inc., Krefeld, Germany). Sequencing was performed with a MiSeq Reagent Kit v3 (600 Cycles) with 7 pM of sample libraries loaded on the Illumina MiSeq (San Diego, CA, USA). Quality controls after fragmentation and final concentration of prepared libraries, were assessed by Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies Inc., Eindhoven, the Netherlands).

Haloplex Bioinformatics Analysis, Variants Filtering, and Assessment of Pathogenicity

FastQ files were aligned to the human reference genome (UCSC hg19, GRCh37) by Burrows–Wheeler Aligner (31). Picard HsMetrics was applied to analyze the target-capture sequencing experiments (http://picard.sourceforge.net/) and internal scripts were used to calculate mean gene coverage. Variant calling was performed by Freebayes (32). Raw variants were filtered by the following parameters: QUAL> 1, (QUAL/AO)> 10, SAF> 0, SAR > 0, RPR > 1, RPL > 1. Variants with an allele depth below 20 reads were excluded from the analysis. Selected variants were annotated for dbSNP-146, ClinVar, dbNSFP v2.9 databases and SnpEff (33) and were filtered for Common Allele Frequencies (CAF) < 5% and variant effect on exons (missense, frameshift, splice acceptor/donor, start lost, stop lost, stop gained, 3′UTR, 5′UTR). Variants found in the either 5′ or 3′ UTR were excluded from the subsequent analyses. In silico analysis for variants' pathogenicity was determined according to 5 prediction tools: Mutation taster, LTR, Polyphen2, SIFT, and CADD score >15 (26–30). In case of trios, variants were subdivided according to model of inheritance (Autosomal Recessive/Dominant, X-linked, De novo). The complete bioinformatics analysis is reported in Supplementary Figure 1B.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed with Graph-Pad Prism, version 6.2 (Graph Pad Software, la Jolla, CA).

Results

Characterization of PID Patients

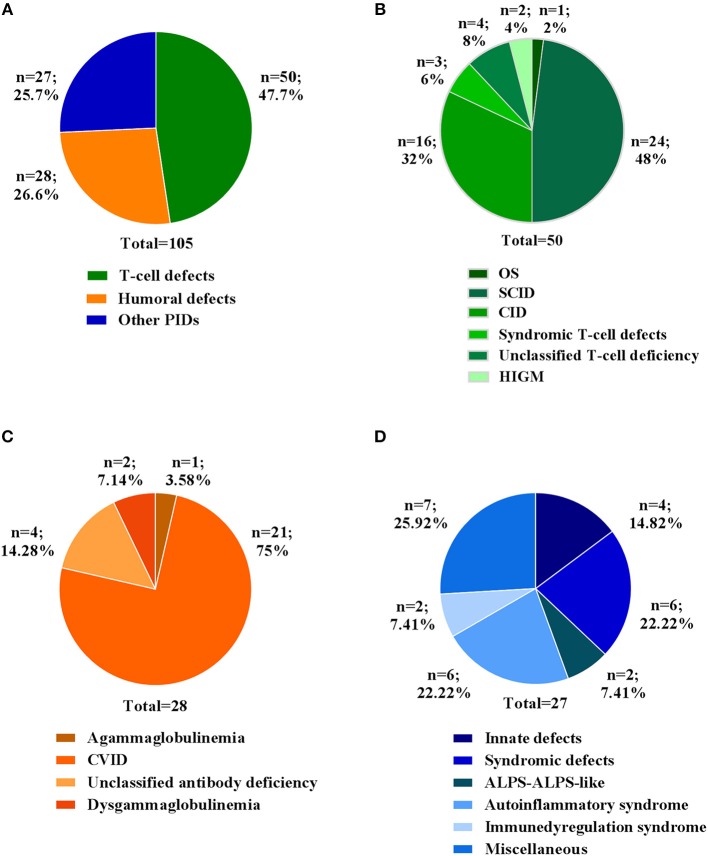

In this study, we report the clinical and molecular characterization of 105 PID patients presenting with either typical or overlapping PID phenotypes. Patients were clustered according to initial clinical presentation in 3 main categories (Figure 1A): T-cell defects (including Omenn syndrome, SCID, CID, syndromic T-cell defect, unclassified T-cell deficiency, hyper IgM syndrome); Humoral defects (agammaglobulinemia, CVID, unclassified antibody deficiency, dysgammaglobulinemia); Other PIDs (immune dysregulation, innate immunity defects including congenital defects of phagocytes, syndromic defects with immune-deficiency signs/symptoms, ALPS-ALPS-like, autoinflammatory syndrome, and a miscellaneous that includes non-typical PID patients with a broad range of clinical phenotypes). The clinical, immunological, and molecular features are reported in Table 1. The percentage of patients in each subgroup is shown in Figures 1B–D. Among the T-cell defects (n = 50; 47,7%), the majority of patients presented with SCID (48%), followed by CID (32%) (Figure 1B). The Humoral Defects group (n = 28; 26,6%) was mainly represented by CVID (75%), while the Other PIDs group (n = 27; 25,7%) included a wide spectrum of rare defects and uncommon phenotypes.

Figure 1.

Clinical diagnosis of patients at admission. (A) Percentage of patients for three main categories. Percentage of each clinical diagnosis in patients belonging to (B) T cell defects, (C) Humoral defects and (D) Other PIDs categories. For each category the total number of patients is indicated.

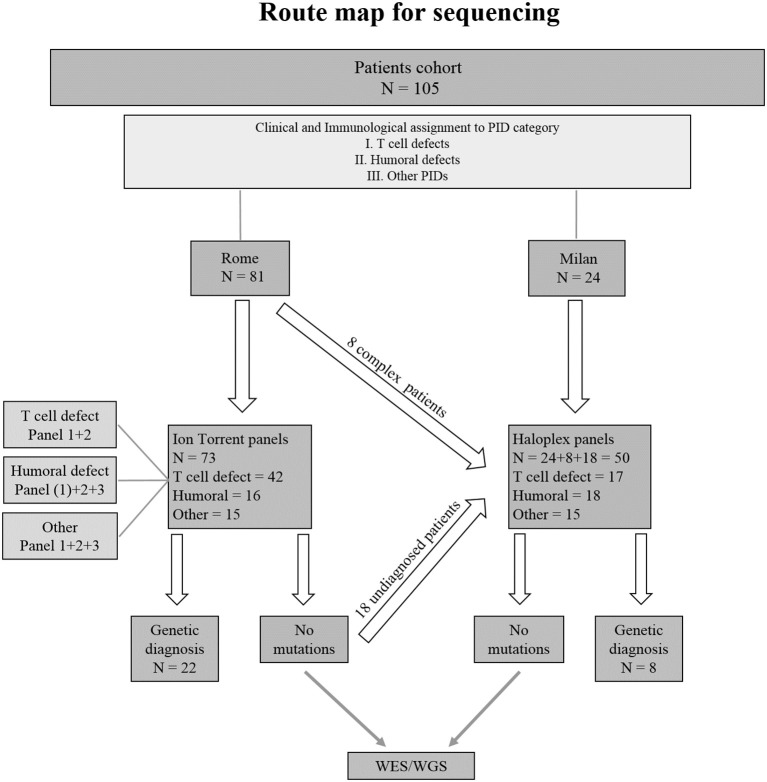

Seventy-three PID patients were analyzed by Ion Torrent sequencing system using three different panels including SCID/CID and CVID known genes. Two Haloplex panels including more than 600 known and candidate PID genes were applied to 32 additional patients. Additionally, 18 patients previously analyzed by Ion Torrent but still without a clear molecular diagnosis, were analyzed by Haloplex system. A flow chart showing the route map for sequencing of index patients is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Flowchart indicating the strategy of the study. (1) Indicates the only patient in Humoral defect group who has been analyzed by Ion Torrent panel 1.

Target Enrichment Performance and Gene Coverage

The mean target coverage resulted of 529 ± 169X (panel 1), 361 ± 97X (panel 2) and 417 ± 117X (panel 3) for Ion Torrent and 229 ± 25X for Haloplex panels (Supplementary Figure 2A). The mean target coverage for Ion Torrent panels was optimal as compared to recently published works in which a coverage of 335X was obtained (34). Indeed, the Ion Torrent expected coverage of the coding regions was 95.43% for panel 1 (SCID-CID), 94.13% for panel 2 (rare CID) and 97.2% for the panel 3 (Supplementary Tables 1–3). The practical coverage obtained from Ion Torrent panels is shown in Supplementary Figures 2B–D.

Primer design for Haloplex aimed at covering more than 97% of the coding regions for all genes. The observed coverage of the targeted regions after running the two panels is represented in Supplementary Tables 4A,B. The majority of shared genes included in all panels and analyzed by both technologies were well-covered (Supplementary Figures 3A–C).

Performance Evaluation

The use of large panels for NGS retrieved a big number of data as compared to small panels. Putative variants detected by Ion Torrent have been examined and validated obtaining an average of false positive variants < 0.6%. Such value decreases reducing the number of genes included in the panel. Haloplex produces larger amount of variants, but only the ones significantly indicative among those related to the patient's phenotype have been investigated; hence, we could not properly evaluate data accuracy. In the 18 patients resequenced by Haloplex, no variants in genes included in the Ion Torrent panels were found supporting the accuracy of these methods. Furthermore, 6 available samples previously diagnosed by Sanger sequencing with 8 known different mutations in RAG1, IL2RG, JAK3, and LIG4 genes, were included in the study and detected by Ion Torrent panel 1 (Table 2A).

Table 2A.

Genetic mutations in 6 positive control PID patients.

| ID | Disease | Gene | RefSeq | Mutation | dbSNP and references | Zygosity | Method | OMIM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PID I | OS | RAG1 | NM_000448 | a) c.1682G>A; p.R561H | b) c.1871G>A; p.R624H | rs104894284; rs199474680 | Compound Heterozygous | Ion Torrent | OMIM *179615 |

| PID II | SCID | IL2RG | NM_000206 | a) c.452T>C; p.L151P | rs137852511 | Hemizygous | Ion Torrent | OMIM *308380 | |

| PID III | SCID | JAK3 | NM_000215 | a) c.1208G>A; p.R403H | Scarselli et al. (35) | Homozygous | Ion Torrent | OMIM *600173 | |

| PID IV | SCID | LIG4 | NM_001352601 | a) c.833G>A, p.R278H | b) c.1271_1275delAAAGA; p.K424RfsTer20 | Cifaldi et al. (36) | Compound Heterozygous | Ion Torrent | OMIM *601837 |

| PID V | leaky SCID | RAG1 | NM_000448 | a) c.2521C>T; p.R841W | rs104894287 | Homozygous | Ion Torrent | OMIM *179615 | |

| PID VI | leaky SCID | RAG1 | NM_000448 | a) c.256_257del; p.K86VfsTer33 | rs772962160 | Homozygous | Ion Torrent | OMIM *179615 | |

In bold novel mutations.

One false negative diagnosis has been recently recognized. Indeed, the Torrent Suite Variant Caller TVC program was unable to identify the c.C664T: p.R222C mutation in exon 5 of IL2RG gene in patient PID16 but this was detectable on IGV.

Molecular Diagnoses

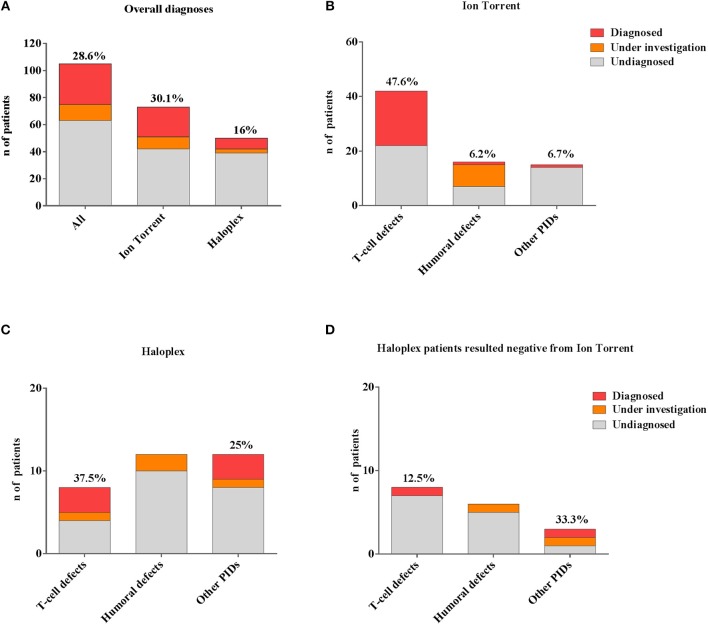

In our cohort, 28.6% (30/105) of molecular diagnosis was obtained (Figure 3A). Sanger sequencing for all mutations and parents' carrier status were performed. Functional studies were conducted for most novel variants and results are reported in Table 2B.

Figure 3.

Comparison between different number of genetic diagnoses obtained by Ion Torrent and Haloplex. (A) Histogram showing the number of overall diagnosed (red), under investigation (orange) or undiagnosed (gray) patients. (B) Histogram showing the Ion Torrent diagnoses. (C) Histograms showing Haloplex diagnoses. (D) Diagnostic findings by Haloplex in negative Ion Torrent patients. The percentages refer only to diagnosed patients.

Table 2B.

Mutations detected in our PID cohort.

| ID | Disease | Gene | RefSeq | Mutation | dbSNP and references | Zygosity | Inheritance | Method | OMIM | Functional test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PID 1 | OS | RAG1 | NM_000448 | a) c.1870C>T; p.R624C | b) c.2521C>T; p.R841W | rs199474688; rs104894287 | Compound Heterozygous | Familial | Ion Torrent | OMIM *179615 | |

| PID 2 | SCID | RAG2 | NM_000536 | a) c.685C>T; p.R229W | rs765298019 | Homozygous | Unknown | Ion Torrent | OMIM *179616 | ||

| PID 3 | SCID | RAG2 | NM_000536 | a) c.1A>G; p.M1V | b) c.1403_1406del ATCT | n.d.; rs786205616 | Compound Heterozygous | Familial | Ion Torrent | OMIM *179616 | n.a. |

| PID 4 | SCID | RAG1 | NM_000448 | a) c.1681C>T; p.R561C | b) c.1815G>C; p.M605I | rs104894285; Dobbs et al. (37) | Compound Heterozygous | Familial | Ion Torrent | OMIM *179615 | Recombinase activity ongoing |

| PID 5 | SCID | IL2RG | NM_000206 | a) c.202G>A; p.E68K | rs.1057520644 | Hemizygous | Familial | Ion Torrent | OMIM *308380 | ||

| PID 6 | SCID | JAK3 | NM_000215 | a) c1796T>G; p.V599G | b) c.2125T>A; p.W709R | Di Matteo et al. (38); rs748216175 | Compound Heterozygous | Familial | Ion Torrent | OMIM *600173 | Published data |

| PID 12 | SCID | ADA | NM_000022 | a) c. 455T>C p.L152P | b) c.478+6T>C | n.d.; Santisteban et al. (39) | Compound Heterozygous | Familial | Ion Torrent/Haloplex | OMIM *608958 | Reduced ADA enzymatic activity |

| PID 15 | SCID | ADA | NM_000022 | a) c.367delG; p.D123fsTer10 | n.d. | Homozygous | Familial | Ion Torrent | OMIM *608958 | Reduced ADA enzymatic activity | |

| PID 16 | CID | IL2RG | NM_000206 | a) c.C664T:p.R222C | rs111033618 | Hemizygous | De novo | Ion Torrent | OMIM *308380 | ||

| PID 17 | SCID | IL2RG | NM_000206 | a) c.677G>A; p.R226H | rs869320660 | Hemizygous | Familial | Ion Torrent | OMIM *308380 | ||

| PID 18 | SCID | IL2RG | NM_000206 | a) c.854G>A; (splice) | rs111033617 | Hemizygous | Familial | Ion Torrent | OMIM *308380 | ||

| PID 19 | SCID | IL2RG | NM_000206 | a) c.455T>G; p.V152G | n.d. | Hemizygous | Familial | Ion Torrent | OMIM *308380 | n.a. | |

| PID 20 | SCID | RAG1 | NM_000448 | a) c.1229G>A; p.R410Q | b) c.1863delG; p.A622QfsTer9 | rs199474684; n.d. | Compound Heterozygous | Unknown | Ion Torrent | OMIM *609889 | n.a. |

| PID 21 | SCID | CD3D | NM_000732 | a) c.274+5G>A | rs730880296 | Homozygous | Mother; n.a. | Ion Torrent | OMIM *186790 | ||

| PID 22 | SCID | RAG1 | NM_000448 | a) c.987delC: p.S330LfsTer15 | n.d. | Homozygous | Unknown | Ion Torrent | OMIM *179615 | Evident pathogenicity | |

| PID 23 | SCID | JAK3 | NM_000215 | a) c.308G>A; p.R103H | rs774202259 | Homozygous | Unknown | Ion Torrent | OMIM *600173 | ||

| PID 24 | SCID | JAK3 | NM_000215 | a) c.1132G>C; p.G378R | b) c.1442-2A>G | rs1485406844; JAK3base_D0095 | Compound Heterozygous | Familial | Ion Torrent | OMIM *600173 | |

| PID 25 | SCID | IL7R | NM_002185 | a) c.134A>C; p.Q45P | b) c.537+1G>A | n.d.; rs777878144 | Compound Heterozygous | Familial | Haloplex | OMIM *146661 | n.a. |

| PID 29 | CID | RAG1 | NM_000448 | a) c. 2521C>T; p.R841W | rs104894287 | Homozygous | Familial | Ion Torrent | OMIM *179615 | ||

| PID 31 | CID | RAG1 | NM_000448 | a) c.1871G>A; p.R624H | b) c. 1213A>G; p.R405G | rs199474680; n.d. | Compound Heterozygous | Familial | Ion Torrent | OMIM *179615 | Recombinase activity ongoing |

| PID 36 | CID | IL7R | NM_002185 | a) c.160T>C; p.S54P | b) c.245G>T; p.C82F | rs1002396899; rs757797163 | Compound Heterozygous | Familial | Ion Torrent | OMIM *146661 | |

| PID 37 | CID | ARPC1B | NM_005720 | a) c.64+1G>A | Brigida et al. (40) (accepted) | Homozygous | Familial | Haloplex | OMIM *604223 | Published data | |

| PID 39 | CID | RAG1 | NM_000448 | a) c.2119G>C; p.E665D | b) c.519delT ; p.Glu174SerfsTer27 | n.d.; rs1241698978 | Compound Heterozygous | Unknown | Haloplex | OMIM *179615 | n.a. |

| PID 49 | HIGM | CD40LG | NM_000074 | a) c.410-2 A>T | rs1254732497 | Hemizygous | Familial | Ion Torrent | OMIM *300386 | ||

| PID 51 | CVID | RAG1 | NM_000448 | a) c.1871G>A; p.R624H | b) c.2182T>C; p.Y728H | rs199474680; Cifaldi et al. (41) | Compound Heterozygous | Familial | Ion Torrent | OMIM *179615 | Published data |

| PID 88 | IBD | XIAP | NM_001167 | a) c.566T>C; p.L189P | Cifaldi et al. (42) | Hemizygous | De novo | Ion Torrent | OMIM *300079 | Published data | |

| PID 83 | NEUTROPENIA | JAGN1 | NM_032492 | a) c.63G>T; p.E21D | rs587777729 | Homozygous | Familial | Haloplex | OMIM *616012 | ||

| PID 84 | NEUTROPENIA | CECR1 | NM_001282225 | a)c.1367A>G, p.Y456C | b)c.1196G>A, p.W399* | Barzaghi et al. (43) | Compound Heterozygous | Familial | Haloplex | OMIM *607575 | Accepted for publication |

| PID 82 | INNATE IMMUNE DISEASE | CARD9 | NM_052813 | a) c.1434+1G>C | Chiriaco et al. (44) | rs141992399 | Homozygous | Familial | Ion Torrent/ Haloplex | OMIM *607212 | |

| MYD88 | NM_002468 | a) c.195_197delGGA; p.E66del | rs878852993 | Homozygous | Familial | OMIM *602170 | |||||

| PID 86 | ALPS-LIKE | NRAS | NM_002524 | a) c.35G>A; p.G12D | rs121913237 | Heterozygous | Somatic | Haloplex | OMIM *164790 | ||

In bold novel not described mutations

A rapid molecular diagnosis was established in 30.1% (22/73) of PID patients who were investigated by Ion Torrent. Diagnoses were achieved in RAG1, RAG2, IL2RG, JAK3, ADA, CD3D, IL7R, CD40L, and XIAP genes (see Table 2B). As expected, the identification of a molecular defect resulted more frequent in patients with a clear clinical and immunological phenotype as shown in those included in the group of T cell defects (20/42; 47.6%) (Figure 3B). Interestingly, the percentage of diagnosis in the group of SCID/CID patients was 60.6% (20/33).

The percentage of molecular diagnosis for the 50 patients studied through the Haloplex panels was of 16% (8/50) as shown in Figure 3A. The first 6 diagnoses were obtained in a cohort of 32 patients. Three SCID/CID patients with mutations in RAG1, IL7R and ARPC1B genes [(40, 45–47) and Volpi et al., under revision] were diagnosed in 8 T cell defects (37,5%). Moreover, JAGN1 (48), CECR1 (43) and NRAS genes, associated to complex phenotypes, were identified in 12 of the Other PIDs group (25%) (Figure 3C).

Two additional patients were diagnosed analyzing the 18 patients, previously negative by Ion Torrent, presenting with a less defined immunological phenotype (Figure 3D). For one patient (PID12), the Ion Torrent panel 1 was able to detect only a missense mutation in the ADA gene. Haloplex identified the second intronic mutation located in the fifth nucleotide upstream exon 5, not included in the Ion Torrent design, of the gene. In the second Ion Torrent negative patient (PID82) presenting an atypical HyperIgE syndrome, Haloplex detected two rare homozygous mutations in MYD88 and CARD9 genes, which were not included in the Ion Torrent panels (1 and 2). The pathogenic role of each single gene mutation is still under investigation but this molecular information is important to optimize the clinical management of the patient including the evaluation of HSCT as definitive treatment (44).

In summary, 4 SCID/CID patients out of a total of 16 T cell defects, were identified by Haloplex, demonstrating once more a higher percentage of diagnosis in this PID group (Table 2B). However, although the possibility to identify a causative gene mutation correlates with a precise clinical clusterization, the identification of patients, with complex and extended phenotypes, needs larger NGS panels.

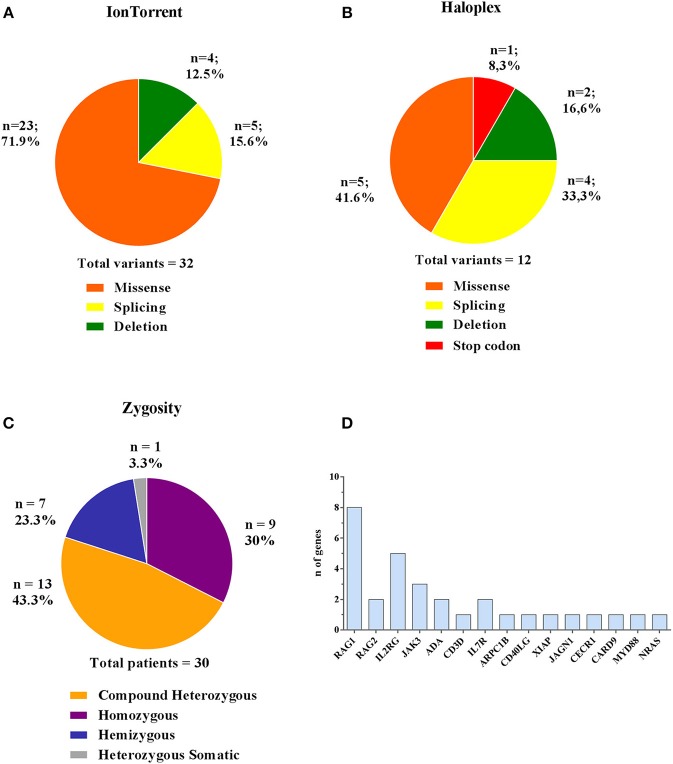

Disease-Associated Variants

Comparing the results obtained by the two methods, 44 (32 Ion Torrent and 12 Haloplex) disease-associated variants have been identified in 30 patients, of whom 18 were novel (Table 2B). The majority of variants detected by Ion Torrent were missense (n = 23; 74.2%) as summarized in Figure 4A. We were also able to detect 4 small deletions and 5 splice site variants. The Haloplex panels detected 5 missense, 2 deletions, 4 splice site and 1 stop codon variants (Figure 4B). Among the 30 diagnosed patients, we found 13 compound heterozygous patients with mutations in RAG1, JAK3, ADA, IL7R, and CECR1 genes, 9 homozygous variants including ADA, RAG1, RAG2, CD3D, JAK3, ARPC1B, MYD88/CARD9, and JAGN1, 7 hemizygous variants in IL2RG, CD40LG, and XIAP, and only 1 heterozygous somatic variant in NRAS (Figure 4C). Therefore, most patients enrolled in this study were offspring of non-consanguineous marriages. The most frequent mutated gene in our cohort is RAG1 followed by IL2RG (Figure 4D).

Figure 4.

Type and zygosity of mutations and mutated genes distribution. Types and percentage of mutations found in diagnosed PID patients for Ion Torrent (A) and Haloplex (B). (C) Overall observed zygosity for diagnosed PID patients. (D) Total number of detected mutated genes.

Putative Neutral Variants vs. Variants of Uncertain Significance (VUS)

Fifteen CVID patients were initially analyzed by Ion Torrent panels 1-2, but no causative variants were found. We therefore designed a specific CVID panel and found 4 putative causative variants suggestive of AD disease that was confirmed by Sanger sequencing. Indeed, we found a heterozygous damaging variant in the CTLA4 gene and a predicted damaging variant in the PTEN gene in an adult patient followed since childhood (PID56). The patient inherited one mutation from the father and one from the mother but the real role of these variants and their possible combined effect is still under investigation. In addition, two other VUS in TCF3 and PLCG2 genes were found in two patients (PID75 and PID54), in which no other evidences are available (see Table 1).

A rare variant in CD40L gene (p.R200S) found in patient PID50 was excluded from the analysis, although an altered CD40L expression was detected. This variant was predicted benign in multiple databases. Furthermore, a homozygous rare variant in CECR1 gene (p.Q233R) was found in patient PID13. However, the two proband's healthy brothers were found to be homozygous for this variant thus it was not considered pathogenic, nevertheless, additional functional studies will be performed to exclude genetic predisposition (e.g., ADA2 activity, protein expression).

Three novel variants of uncertain significance (VUS) identified by Haloplex in patients with classical and complex phenotypes are still “under investigation.” We are currently validating a novel damaging variant in the TCF3 gene in two twin patients (PID57-58) and their mother affected by CVID (49). EMSA assay is ongoing to assess the capacity of TCF3 protein to bind DNA target sequences. In these twin patients we also previously found by Sanger sequencing a mutation in TNFRSF13B gene already described to be associated to CVID (50).

A causative variant in the BMP4 gene (51) with a severe myopia, ectodermal dysplasia, and cytopenia was found in a patient (PID95) in whom the altered immunological phenotype remains poorly explained by this mutation. Moreover, NFκB1 variant in a CID patient (PID38) was found but its significance is still under investigation.

Finally, heterozygous variants in TNFRSF13B (PID70, PID87) and NOD2 (PID77), genes were found by Haloplex in three patients. Generally, variants in susceptibility genes involved in the disease pathogenesis should be considered for potential future phenotypic implications particularly in adult patients where multiple factors may contribute to the onset of the disease.

Discussion

The application of multigene NGS panels has extended our knowledge of PIDs and is currently recognized as a comprehensive diagnostic method in the field of rare disorders consenting the diagnosis in the 15–70% of all cases depending on the PID clinical and phenotypic clusterization (25, 52). In the present work we show that the complementary, integrated use of two custom-made targeted sequencing approaches, Ion Torrent or Haloplex, allowed to clearly identify causative variants in 28.6% (n = 30) of the patients in all groups of PIDs, confirming the value of NGS assays to obtain a genetic diagnosis for PIDs (17–23).

The Ion Torrent approach resulted highly successful for SCID patients, a group generally more defined for its immunological and clinical presentation (53). Indeed, with this approach we identified 20/33 SCID/CID patients (60,6%). The Haloplex workflow was able to identify causative variants in 8/50 patients (16%) of whom 4 were found in the group of SCID/CID patients and 4 fall in that of complex and extended phenotypes. Interestingly, a molecular diagnosis was achieved in 2/18 (11%) patients presenting with typical and atypical clinical phenotypes resulted negative after Ion Torrent analysis and included in the Haloplex approach.

By NGS it is possible to identify unexpected mutations in apparently not corresponding PID cases, as recently reported by our group for a patient with agammaglobulinemia due to RAG1 deficiency (41). This result strengthen the notion of a large phenotypic variety associated with RAG deficiency, suggesting that it should be considered also in patients presenting with an isolated marked B-cell defect (54–57) and as already reported that RAG mutations are more frequent than expected. Notably, RAG1 is the most frequent PID cause in our cohort. This case represents a paradigmatic model of how new questions arise on the management and follow-up for patients in which a milder phenotype could be associated to alternative treatments to transplantation (41, 57, 58).

CVID is a typical example of a disease with a broad phenotype due to different gene alterations (59–61). Notably, in 4 CVID patients with mutations in TNFRSF13B and AIRE previously detected by Sanger sequencing (see Table 1) we extended NGS analysis to looking for novel disease causing genes. Therefore, frequent variants comparable to polymorphisms should be considered with caution since the pathogenic meaning is still unclear. Additional functional studies in these cases are required. Four additional diagnoses are summarized in Supplementary Table 5 (62). These were obtained after the completion of the present study by other targeted NGS panels and Sanger sequencing, indicating that the combination of in-depth clinical knowledge and appropriate sequencing techniques can lead to new diagnoses.

Although the prioritization methods applied in this study follows all common assumptions for a correct data analysis, the identification of novel variants currently under investigation represents a challenge and their validation needs the essential support of further in-depth experimental studies (6–8, 63). The integration of clinical, immunological, biochemical and molecular data might favor a revised PIDs classification of patients with similar phenotype due to a different genetic cause, or patients with different phenotypes but with the same genetic cause. In our experience, the use of selected NGS panels is useful and easy to handle for rapid diagnosis in clinically and immunologically well-characterized phenotypes. As compared to WES, targeted small NGS panels provide an important alternative for clinicians for direct sequencing of relevant genes, guaranteeing a high coverage and sequencing depth (64). On the contrary, their application in patients with atypical phenotypes could result in an incomplete and delayed diagnosis. Extended gene panels or WES should be directly used in these cases for research purposes, to allow the diagnosis of unexpected genotype-phenotype association.

As reported by several groups (7, 8, 22–24), the application of targeted WES for each suspicion of PID by exploring gene-by-gene also for limited numbers of striking genes still remain time and resource consuming in the absence of synergy between clinical and bioinformatics supports. This is yet unfeasible for extended diagnostic purposes. Indeed, the huge amount of retrieved data and the risk of incidental findings in other non-PID genes involved in different monogenic or multifactorial pathologies may be confounding and do not corresponding to the first suspicion. Additionally, the confidence of the results decreases with the number of targeted genes and may preclude any variant detection in self-evident known genes (65). Many previously undetected variants do not have a well-defined role in our genome (1.5 × 106 million variants in each genome and lesser in exome). In this scenario, ethical and legal issues related to the disclosure of genetic information generated by NGS need to be considered and guidelines should be developed to help the different specialists to translate the genetic results into the clinics (64).

The achievement of NGS application will require further integration of knowledge based on clinical, immunological and molecular data and the collaboration among different experts in these fields. A better clinical, immunological and genetic characterization of new PIDs will significantly contribute to the identification of diagnostic and prognostic markers and early individual therapeutic strategies with significant patients' benefit.

Data Availability

Data have been uploaded to ClinVar, accession number: SUB5252744.

Author Contributions

CrC, IB, and GD performed experiments, developed gene panels for targeted sequencing. CrC, IB, FB, and DMG interpreted the results and wrote the manuscript. DP, CrC, VF, FS, CaC, and GD created gene clusters to filter variants and integrated clinical and bioinformatics analysis of data retrieved by Ion Torrent platform. IB, DL, DC, FB, MPC, MZ, DP, CrC, GD, MO, and CaC created gene clusters to filter variants and integrated clinical and bioinformatics analysis of data retrieved by Haloplex workflow. CrC, IB, SD, GF, MC, MZ, MG, AV, and GD performed molecular and functional experiments. FB, MPC, EA, FC, AS, FL, FF, CP, GF, GB, PM, DM, ClC, PP, SC, AT, VM, LC, CA, AF, FLi, PR, CaC, and AA provided or referred clinical samples and patient's clinical data. GD, IB, SG, FS, CrC, CaC, and AA participate to the study design and data interpretation. CaC, FS, GD, and AA designed the research, participate to the study design and data interpretation. FS, VM, SG, SF, and FLi made substantial contributions to revising the manuscript. CaC, GD, and AA supervised the research and manuscript revision. Legend: CrC, Cifaldi Cristina; FC, Conti Francesca; CaC, Cancrini Caterina; ClC, Canessa Clementina; FL, Licciardi Francesco; FLi, Locatelli Franco.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Dr. Taruscio and Dr. Torreri (Istituto Superiore di Sanità) for their help in the development of patient's database. The authors are grateful to patients and families.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- AD

Autosomal Dominant

- AR

Autosomal Recessive

- CAF

Common Allele Frequency

- CDS

Coding Sequence

- CID

Combined Immunodeficiencies

- CVID

Common Variable Immunodeficiency

- IGV

Integrative Genome Viewer

- MAF

Minor Allele Frequency

- NGS

Next Generation Sequencing

- PCR

Polymerase Chain Reaction

- PID

Primary Immunodeficiency

- SCID

Severe Combined Immunodeficiency

- SNP

Single Nucleotide Polymorphism

- UTR

Untranslated Region

- VCF

Variant Calling Format

- WES

Whole Exome Sequencing

- WGS

Whole Genome Sequencing.

Footnotes

Funding. The study was supported by grants of the Italian Ministero della Salute (NET-2011-02350069) to AA and CaC, the European Commission (ERARE-3-JTC 2015 EUROCID) to AA, the Ricerca Corrente from Childrens' Hospital Bambino Gesù, Rome, Italy (201702P003966) to CaC, Fondazione Telethon (GGP15109) to AF and Fondazione Telethon (TIGET Core grant C6) to AA. MPC and GF acknowledge 5x1000 OSR PILOT & SEED GRANT by Ospedale San Raffaele. IB received fellowship from not-for-profit LaSpes organization. MZ, FB, and DP conducted this study as partial fulfillment of their Ph.D. in Immunology, Molecular Medicine, and Applied Biotechnologies Applicate, Tor Vergata University, Rome, Italy. Participating centers are part of the Italian Network for Primary Immunodeficiencies (IPINET) of Associazione Italiana di Ematologia ed Oncologia Pediatrica (AIEOP).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2019.00316/full#supplementary-material

Schematic representation of filtering variants strategy for Ion Torrent (A) and Haloplex (B).

Coverage analysis. (A) Mean target coverage for genes included in Haloplex and Ion Torrent panels 1-2 and 3. Box and whiskers show median, 5th and 95th percentiles. Haloplex shows 605 shared genes in the two panels. (B) Mean gene coverage for Ion Torrent Panel 1, (C) panel 2 and (D) panel 3. Coverage is shown as number of reads.

Comparison of coverage analysis. (A–C) Comparison of mean gene coverage in shared genes between Ion Torrent and Haloplex panels.

Theoretical coverage of genes included in Ion Torrent panel 1.

Theoretical coverage of genes included in Ion Torrent panel 2.

Theoretical coverage of genes included in Ion Torrent panel 3.

(A) Theoretical and effective coverage of gene intervals in Haloplex platform panel 1. (B) Theoretical and effective coverage of gene intervals in Haloplex platform panel 2.

Additional diagnoses obtained after this study.

References

- 1.Bousfiha A, Jeddane L, Picard C, Ailal F. The 2017 IUIS phenotypic classification for primary immunodeficiencies. J Clin Immunol. (2018) 38:129–43. 10.1007/s10875-017-0465-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Notarangelo LD. Primary immunodeficiencies. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2010) 125:S182–94. 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.07.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Picard C, Bobby Gaspar H, Al-Herz W, Bousfiha A, Casanova J-L, Chatila T, et al. International Union of Immunological Societies: 2017 primary immunodeficiency diseases committee report on inborn errors of immunity. J Clin Immunol. (2018) 38:96–128. 10.1007/s10875-017-0464-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ochs HD, Hagin D. Primary immunodeficiency disorders: general classification, new molecular insights, and practical approach to diagnosis and treatment. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. (2014) 112:489–95. 10.1016/j.anai.2014.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonilla FA, Khan DA, Ballas ZK, Chinen J, Frank MM, Hsu JT, et al. Practice parameter for the diagnosis and management of primary immunodeficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2015) 136:1186–205. 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.04.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Casanova J-LJ-L, Conley ME, Seligman SJ, Abel L, Notarangelo LD. Guidelines for genetic studies in single patients: lessons from primary immunodeficiencies. J Exp Med. (2014) 211:2137–49. 10.1084/jem.20140520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meyts I, Bosch B, Bolze A, Boisson B, Itan Y. Exome and genome sequencing for inborn errors of immunity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2016) 138:957–69. 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.08.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seleman M, Hoyos-Bachiloglu R, Geha RS, Chou J. Uses of next-generation sequencing technologies for the diagnosis of primary immunodeficiencies. Front Immunol. (2017) 8:847. 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Erman B, Bilic I, Hirschmugl T, Salzer E, Boztug H, Sanal, et al. Investigation of Genetic Defects in Severe Combined Immunodeficiency Patients from Turkey by targeted sequencing. Scand J Immunol. (2017) 85:227–34. 10.1111/sji.12523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heimall JR, Hagin D, Hajjar J, Henrickson SE, Hernandez-Trujillo HS, Tan Y, et al. Use of genetic testing for primary immunodeficiency patients. J Clin Immunol. (2018) 38:320–9. 10.1007/s10875-018-0489-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lenardo M, Lo B, Lucas CL. Genomics of immune diseases and new therapies. Annu Rev Immunol. (2016) 34:121–49. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-041015-055620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Notarangelo LD, Fleisher TA. Targeted strategies directed at the molecular defect: Toward precision medicine for select primary immunodeficiency disorders. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2017) 139:715–23. 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Valencic E, Grasso AG, Conversano E, Lucafò M, Piscianz E, Gregori M, et al. Theophylline as a precision therapy in a young girl with PIK3R1 immunodeficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. (2018) 6:2165–7. 10.1016/j.jaip.2018.02.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raje N, Soden S, Swanson D, Ciaccio CE, Kingsmore SF, Dinwiddie DL. Utility of Next Generation Sequencing in Clinical Primary Immunodeficiencies. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. (2014) 14:1–13. 10.1007/s11882-014-0468-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Picard C, Fischer A. Contribution of high-throughput DNA sequencing to the study of primary immunodeficiencies. Eur J Immunol. (2014) 44:2854–61. 10.1002/eji.201444669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suzuki T, Sasahara Y, Kikuchi A, Kakuta H, Kashiwabara T, Ishige T, et al. Targeted sequencing and immunological analysis reveal the involvement of primary immunodeficiency genes in pediatric IBD: a Japanese Multicenter Study. J Clin Immunol. (2017) 37:67–79. 10.1007/s10875-016-0339-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stoddard JL, Niemela JE, Fleisher TA, Rosenzweig SD. Targeted NGS : a cost-effective approach to molecular diagnosis of PIDs. Front Immunol. (2014) 5:531. 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moens LN, Falk-Sörqvist E, Asplund AC, Bernatowska E, Smith CIE, Nilsson M. Diagnostics of primary immunodeficiency diseases: a sequencing capture approach. PLoS ONE. (2014) 9:e114901. 10.1371/journal.pone.0114901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nijman IJ, Van Montfrans JM, Hoogstraat M, Boes ML, Van De Corput L, Renner ED, et al. Targeted next-generation sequencing: a novel diagnostic tool for primary immunodeficiencies. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2014) 133:1–7. 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.08.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fang M, Abolhassani H, Lim CK, Zhang J, Hammarström L. Next generation sequencing data analysis in primary immunodeficiency disorders – future directions. J Clin Immunol. (2016) 36:68–75. 10.1007/s10875-016-0260-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Al-Mousa H, Abouelhoda M, Monies DM, Al-Tassan N, Al-Ghonaium A, Al-Saud B, et al. Unbiased targeted next-generation sequencing molecular approach for primary immunodeficiency diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2016) 137:1780–7. 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.12.1310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stray-Pedersen A, Sorte HS, Samarakoon P, Gambin T, Chinn IK, Coban Akdemir ZH, et al. Primary immunodeficiency diseases: Genomic approaches delineate heterogeneous Mendelian disorders. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2017) 139:232–45. 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.05.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gallo V, Dotta L, Giardino G, Cirillo E, Lougaris V, D'Assante R, et al. Diagnostics of primary immunodeficiencies through next-generation sequencing. Front Immunol. (2016) 7:466. 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mousallem T, Urban TJ, McSweeney KM, Kleinstein SE, Zhu M, Adeli M, et al. Clinical application of whole-genome sequencing in patients with primary immunodeficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2015) 136:476–9.e6. 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.02.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bisgin A, Boga I, Yilmaz M, Bingol G, Altintas D. The utility of next-generation sequencing for primary immunodeficiency disorders: experience from a clinical diagnostic laboratory. Biomed Res Int. (2018) 2018:9647253. 10.1155/2018/9647253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lubeck E, Coskun AF, Zhiyentayev T, Ahmad M, Cai L. MutationTaster2: mutation prediction for the deep-sequencing age. Nat Methods Nat Methods Nat Methods. (2012) 9:743–8. 10.1038/nmeth.2892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chun S, Fay JC. Identification of deleterious mutations within three human genomes. Genome Res. (2009) 19:1553–61. 10.1101/gr.092619.109.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adzhubei I, Jordan DM, Sunyaev SR. Predicting functional effect of human missense mutations using PolyPhen-2. Curr Protoc Hum Genet. (2013) Chapter 7:Unit7.20. 10.1002/0471142905.hg0720s76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kumar P, Henikoff S, Ng PC. Predicting the effects of coding non-synonymous variants on protein function using the SIFT algorithm. Nat Protoc. (2009) 4:1073–81. 10.1038/nprot.2009.86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kircher M, Witten DM, Jain P, O'Roak BJ, Cooper GM, Shendure J. A general framework for estimating the relative pathogenicity of human genetic variants. Nat Genet. (2014) 46:310–5. 10.1038/ng.2892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li H. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. arXiv Prepr arXiv. (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garrison E, Marth G. Haplotype-based variant detection from short-read sequencing. arXiv Prepr arXiv12073907. (2012) 9. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cingolani P, Platts A, Wang LL, Coon M, Nguyen T, Wang L, et al. A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff: SNPs in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster strain w1118; iso-2; iso-3. Fly. (2012) 6:80–92. 10.4161/fly.19695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abolhassani H, Chou J, Bainter W, Platt CD, Tavassoli M, Momen T, et al. Clinical, immunologic, and genetic spectrum of 696 patients with combined immunodeficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2018) 141:1450–8. 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.06.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scarselli A, Di Cesare S, Di Matteo G, De Matteis A, Ariganello P, Romiti ML, et al. Combined immunodeficiency due to JAK3 mutation in a child presenting with skin granuloma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2016) 137:948–51.e5. 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cifaldi C, Angelino G, Chiriaco M, Di Cesare S, Claps A, Serafinelli J, et al. Late-onset combined immune deficiency due to LIGIV mutations in a 12-year-old patient. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. (2017) 28:203–6. 10.1111/pai.12684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dobbs K, Tabellini G, Calzoni E, Patrizi O, Martinez P, Giliani SC, et al. Natural killer cells from patients with recombinase-activating gene and non-homologous end joining gene defects comprise a higher frequency of CD56bright NKG2A+++ cells, and yet display increased degranulation and higher perforin content. Front Immunol. (2017) 8:1244 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Di Matteo G, Chiriaco M, Scarselli A, Cifaldi C, Livadiotti S, Di Cesare S. JAK3 mutations in Italian patients affected by SCID: new molecular aspects of a long-known gene. Mol Genet Genomic Med. (2018) 6:713–21. 10.1002/mgg3.391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Santisteban I, Arredondo-Vega FX, Kelly S, Mary A, Fischer A, Hummell DS, et al. Novel splicing, missense, and deletion mutations in seven adenosine deaminase-deficient patients with late/delayed onset of combined immunodeficiency disease. Contribution of genotype to phenotype. J Clin Invest. (1993) 92:2291–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brigida I, Zoccolillo M, Cicalese MP, Barzaghi F, Scala S, Oleaga- C, et al. T-cell defects in patients with ARPC1B germline mutations account for combined immunodeficiency. Blood. (2018) 132:2362–74. 10.1182/blood-2018-07-863431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cifaldi C, Scarselli A, Petricone D, Di Cesare S, Chiriaco M, Claps A, et al. Agammaglobulinemia associated to nasal polyposis due to a hypomorphic RAG1 mutation in a 12 years old boy. Clin Immunol. (2016) 173:121–3. 10.1016/j.clim.2016.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cifaldi C, Chiriaco M, Di Matteo G, Di Cesare S, Alessia S, De Angelis P, et al. Novel X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis mutation in very early-onset inflammatory bowel disease child successfully treated with HLA-haploidentical hemapoietic stem cells transplant after removal of αβ+T and B cells. Front Immunol. (2017) 8:1893. 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barzaghi F, Minniti F, Mauro M, Bortoli M, Balter R, Bonetti E, et al. ALPS-like phenotype caused by ADA2 deficiency rescued by allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Front Immunol. (2019) 9:2767. 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chiriaco M, Di Matteo G, Conti F, Petricone D, De Luca M, Di Cesare S, et al. First case of patient with two homozygous mutations in MYD88 and CARD9 genes presenting with pyogenic bacterial infections, elevated IgE, and persistent EBV viremia. Front. Immunol. (2019) 10:130. 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kuijpers TW, Tool ATJ, van der Bijl I, de Boer M, van Houdt M, de Cuyper IM, et al. Combined immunodeficiency with severe inflammation and allergy caused by ARPC1B deficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2017) 140:273–77.e.10. 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.09.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kahr WHA, Pluthero FG, Elkadri A, Warner N, Drobac M, Chen CH, et al. Loss of the Arp2/3 complex component ARPC1B causes platelet abnormalities and predisposes to inflammatory disease. Nat Commun. (2017) 8:14816. 10.1038/ncomms14816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Somech R, Lev A, Lee YN, Simon AJ, Barel O, Schiby G, et al. Disruption of thrombocyte and T lymphocyte development by a mutation in ARPC1B. J Immunol. (2017) 199:4036–45. 10.4049/jimmunol.1700460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cifaldi C, Sera J, Petricone D, Brigida I, Di Cesare S, Di Matteo G, et al. Next-generation sequencing reveals A JAGN1 mutation in a syndromic child with intermittent neutropenia. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. (2018). [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1097/MPH.0000000000001256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Engel I, Murre C. The function of E- and ID proteins in lymphocyte development. Nat Rev Immunol. (2001) 1:193–9. 10.1038/35105060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ameratunga R, Koopmans W, Woon S-T, Leung E, Lehnert K, Slade CA, et al. Epistatic interactions between mutations of TACI (TNFRSF13B) and TCF3 result in a severe primary immunodeficiency disorder and systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Transl Immunol. (2017) 6:e159. 10.1038/cti.2017.41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Huang Y, Lu Y, Mues G, Wang S, Bonds J, D'Souza R. Functional evaluation of a novel tooth agenesis-associated bone morphogenetic protein 4 prodomain mutation. Eur J Oral Sci. (2013) 121:313–8. 10.1111/eos.12055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rae W, Ward D, Mattocks C, Pengelly RJ, Eren E, Patel SV, et al. Clinical efficacy of a next-generation sequencing gene panel for primary immunodeficiency diagnostics. Clin Genet. (2018) 93:647–55. 10.1111/cge.13163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yu H, Zhang VW, Stray-Pedersen A, Hanson IC, Forbes LR, de la Morena MT, et al. Rapid molecular diagnostics of severe primary immunodeficiency determined by using targeted next-generation sequencing. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2016) 138:1142–51.e2. 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.05.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Abolhassani H, Wang N, Aghamohammadi A, Rezaei N, Lee YN, Frugoni F, et al. A hypomorphic recombination-activating gene 1 (RAG1) mutation resulting in a phenotype resembling common variable immunodeficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2014) 134:1375–80. 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.04.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kato T, Crestani E, Kamae C, Honma K, Yokosuka T, Ikegawa T, et al. RAG1 Deficiency May Present Clinically as Selective IgA Deficiency. J Clin Immunol. (2015) 35:280–8. 10.1007/s10875-015-0146-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hedayat M, Massaad MJ, Lee YN, Conley ME, Orange JS, Ohsumi TK, et al. Lessons in gene hunting: A RAG1 mutation presenting with agammaglobulinemia and absence of B cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2014) 134:983–5. 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.04.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Notarangelo LD, Kim MS, Walter JE, Lee YN. Human RAG mutations: biochemistry and clinical implications. Nat Rev Immunol. (2016) 16:234–6. 10.1038/nri.2016.28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Villa A, Sobacchi C, Notarangelo LD, Bozzi F, Abinun M, Abrahamsen TG, et al. V(D)J recombination defects in lymphocytes due to RAG mutations: severe immunodeficiency with a spectrum of clinical presentations. Blood. (2001) 97:81–8. 10.1182/blood.V97.1.81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bogaert DJA, Dullaers M, Lambrecht BN, Vermaelen KY, De Baere E, Haerynck F. Genes associated with common variable immunodeficiency: one diagnosis to rule them all? J Med Genet. (2016) 53:575–90. 10.1136/jmedgenet-2015-103690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.van Schouwenburg PA, Davenport EE, Kienzler AK, Marwah I, Wright B, Lucas M, et al. Application of whole genome and RNA sequencing to investigate the genomic landscape of common variable immunodeficiency disorders. Clin Immunol. (2015) 160:301–4. 10.1016/j.clim.2015.05.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Maffucci P, Filion CA, Boisson B, Itan Y, Shang L, Casanova JL, et al. Genetic diagnosis using whole exomesequencing in common variable immunodeficiency. Front Immunol. (2016) 7:220. 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]