Abstract

Gastric cancer is one of the most common malignant tumors in the world. Due to the lack of early diagnosis and effective treatment, the outcome of treatment and prognosis is poor. MicroRNA-145 (miR-145) is downregulated in various cancer types. In the present study, miR-145 expression was detected by reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction in gastric cancer cell lines and normal gastric epithelial cells. The function of miR-145 in the gastric cancer cell line SGC-7901 was investigated. The present results demonstrated that the expression of miR-145 was downregulated in gastric cancer cells. Further analysis identified that upregulation of miR-145 significantly suppressed SGC-7901 cell proliferation, increased cellular apoptosis and blocked the cell cycle in the G1 phase. Additionally, overexpression of miR-145 reduced SGC-7901 cell invasion and metastasis in vitro. Western blot analysis demonstrated that overexpression of miR-145 downregulated Myc proto-oncogene protein, phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B and matrix metalloproteinase 2/9, and upregulated p21 in SGC-7901 cells. The present results revealed potential signaling pathways that miR-145 may use to regulate gastric cancer cell proliferation, apoptosis and metastasis. Collectively, the present results suggest that miR-145 is a tumor suppressor for gastric cancer and it may be a potential therapeutic target for gastric cancer treatment.

Keywords: microRNA-145, gastric cancer, apoptosis, cell cycle, invasion, migration

Introduction

Gastric cancer is one of the most common malignancies in the world with poor prognosis (1,2). Despite the reduced incidence in recent decades, gastric cancer remains the third leading cause of global cancer-associated mortality, and has the highest incidence in East Asia (3,4). The early diagnosis of gastric cancer requires improvement, as it frequently only identified in the advanced stage (5). Therefore, the prognosis of patients with gastric cancer is very poor (6–8). The primary reason for failure in the treatment of gastric cancer is cell infiltration and metastasis (9).

MicroRNAs (miRNAs/miRs) are evolutionarily conserved non-coding RNA of ~19–25 nucleotides, which function by regulating one or more mRNA to regulate gene expression for translation inhibition or cleavage (10,11). miR serve a key role in cell proliferation, cell death and organ development (12,13). In addition, previous studies demonstrated that miRs are key regulators in the development and progression of gastric cancer (14,15). However, the expression status and biological function of specific miRs in gastric cancer require further examination. miR-145 was first reported to be consistently decreased in precancerous colorectal lesions (16). Other previous studies observed that miR-145 as a tumor-suppressive miRNA regulates cell growth in tumor cells by targeting epidermal growth factor receptor, Myc proto-oncogene protein (c-Myc) and POU domain, class 5, transcription factor 1 (17–20). In addition, miR-145 has been studied in gastric cancer (21). Lei et al (22) reported that miR-145 inhibits gastric cancer cell migration and metastasis by inhibiting MYO6 expression. The results of the research of Qiu et al (23) indicated that miR-145 suppressed the proliferation, migration, invasion and cell cycle progression of gastric cancer cells through decreasing Sp1 expression. Gao et al (24) suggested that miR-145 suppresses gastric cancer metastasis by inhibiting N-cadherin protein translation. However, the exact function and underlying molecular mechanism of miR-145 in gastric cancer remains largely unclear and requires further examination.

In the present study, the expression of miR-145 was significantly decreased in gastric cancer cells. Further, miR-145 overexpression was able to inhibit the proliferation of gastric cancer cells and induce apoptosis. In addition, it was observed that miR-145 mimics inhibited gastric cancer cell invasion and migration by regulating the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (AKT) signaling pathway. The present results demonstrated that miR-145 functions as an anti-tumor gene in gastric cancer cell, and is a potential therapeutic target.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and transfection

Gastric cancer cell line SGC-7901 and normal gastric epithelial cells GES-1 were obtained from the Cell Bank of Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). All cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; both Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Cells were incubated in a humidified incubator at 37°C and 5% CO2.

The miR-145 mimics (5′-GTCCAGTTTTCCCAGGAATCCCT-3′) (50 nM), miR-145 inhibitor (5′-AGGGATTCCTCCCAAAACTGGAC-3′) (100 nM) and the negative control vector (5′-GUAGGAGUAGUGAAAGGCC-3′) (NC; 50 nM; Shanghai GenePharma Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) were transfected into SGC-7901 cells using Lipofectamine® 2000 (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's protocol. After transfection for 48–72 h, cells were collected for further assays. Cells in the blank group (BL) were untreated cells.

Cell proliferation

The proliferation of SGC-7901 cells transfected with miR-145 mimics, miR-145 inhibitor or NC were examined using MTT colorimetric assays. After transfection for 48 h, SGC-7901 cells (1×105) were seeded in 96-well plates in triplicate. MTT (20 µl; 5 mg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) was added to each well at 48 h after transfection. Following incubation for 4 h, the MTT medium was removed and 150 µl dimethyl sulfoxide was added. After shaking for 15 min at room temperature, the optical density at the 490 nm of each sample was determined with scanning multi-well spectrophotometer.

Flow cytometry analysis

SGC-7901 cells were transfected with miR-145 mimics, miR-145 inhibitor or NC, and 48 h after transfection, the cells were collected and washed with PBS. To detect the cell cycle, the cells were fixed in 70% methanol at −20°C overnight. Subsequently, the cells were washed with PBS twice and stained with propidium iodide (PI). Finally, flow cytometry was used to detect cell cycle.

To detect cellular apoptosis, cells were stained with an Annexin V/PI (apoptosis detection kit; BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. After incubating with Annexin V/PI for 15 min in the dark, cellular apoptosis (Q1: Dead cells; Q2: Late apoptosis; Q3: Normal cells; Q4: Early apoptosis) was detected using a flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Data were analyzed by using WinMDI version 2.5 (Purdue University Cytometry Laboratories; http://www.cyto.purdue.edu/flowcyt/software/Catalog.htm).

Cell invasion assay

The effect of miR-145 on SGC-7901 cell invasive capability was detected using a 24-well Transwell plate (8 mm pore size; Corning Incorporated, Corning, NY, USA). Chamber inserts were coated with 200 mg/ml Matrigel and dried overnight under sterile conditions. SGC-7901 cells were transfected with miR-145 mimic, miR-145 inhibitor or NC, and 48 h after transfection, the cells (1×104) in RPMI-1640 medium were added to the top chamber, and RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 20% FBS was added to the lower chamber. Following incubation for 48 h at 37°C, the top chambers were wiped with cotton wool to remove the noninvasive cells and subsequently fixed in 100% methanol at room temperature for 10 min. Following staining in hematoxylin-eosin solution at room temperature for 20 min, the invading cells on the underside of the membrane were counted at five random fields under a light microscope (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

Cell migration assay

The scratch wound healing assay was used to detect the effect of miR-145 on SGC-7901 cell metastasis. SGC-7901 cells were transfected with miR-145 mimics, miR-145 inhibitor or NC, and cells (1×104 cells/well) were subsequently seeded homogeneously on 6-well plates. When the cells formed a monolayer, a sterile plastic 200 µl pipette tip was used to scratch the cells. The floating cells were washed with RPMI-1640 medium. At 0, 24 and 48 h after scratch wound formation, images were obtained using an inverted microscope at a magnification of ×200 and measured using Image-Pro Plus software version 7.0 (Media Cybernetics, Inc., Rockville, MD, USA).

Western blot analysis

SGC-7901 cells, which were transfected with miR-145 mimics, miR-145 inhibitor or NC for 48 h, were collected and the total proteins were extracted using 40 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) containing 150 mM NaCl and 1% (v/v) Triton X-100, supplemented with protease inhibitors. Protein concentration was determined using the bicinchoninic acid protein assay. Equal amounts of protein (30 µg per lane) were resolved on 10% SDS-PAGE, and subsequently transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). Following blocking with 5% skimmed milk in Tris buffered saline with 0.1% Tween-20 at room temperature for 1.5 h, samples were probed with antibodies against c-Myc (1:1,000; cat. no. 5605; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Danvers, MA, USA), phosphorylated (p-)AKT (1:1,000; cat. no. 4060; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), PI3K (1:1,000; cat. no. 4249; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), P21 (1:1,000; cat. no. 2947; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) 2 (1:1,000; cat. no. 40994; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), MMP9 (1:1,000; cat. no. 13667; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) and GAPDH (1:1,000; cat. no. 8884; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.). Following washing with 1X PBST (10 min/wash) for three times, blots were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:2,000; cat. no. 7074; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) at room temperature for 2 h. Immunoreactive bands were visualized using SignalFire™ Plus ECL Reagent (cat no. 12630; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.). The protein expression levels of the stripes were normalized based on the gray value of GAPDH. Image J version 2.0 software (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc, USA) was used to quantify the intensity of the bands.

Reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from cells using RNAiso Plus (Takara Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Dalian, China) according to the manufacturer's protocol. RT was conducted to synthesize cDNA with the ThermoScript RT-PCR system (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's protocol. qPCR was performed to analyze the synthesized cDNA by using the SYBR® Premix Ex Taq™ II kit (Takara Bio, Inc., Otsu, Japan). Primer sequences were listed as following: U6 forward: 5′GCTTCGGCAGCACATATACTAAAAT3′ and reverse: 5′CGCTTCACGAATTTGCGTGTCAT3′; miR-145 forward: 5′-GTCCAGTTTTCCCAGGAATCCCT-3′ and reverse: 5′-GCTGTCAACGATACGCTACCTA-3′. The conditions of qPCR used for amplification were as follows: 95°C for 5 min, 40 cycles at 95°C for 30 sec, 55°C for 30 sec, 72°C for 30 sec, and 72°C for 10 min. U6 served as an internal control. The relative gene expression was assessed by using the 2−ΔΔCq method (25). The experiment was repeated at least three times.

Statistical analysis

SPSS version 17.0 software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used to analyze the data. Dare are presented as the mean ± standard deviation of experiments performed in triplicate. Data were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey's post-hoc test, or the Student's t-test. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

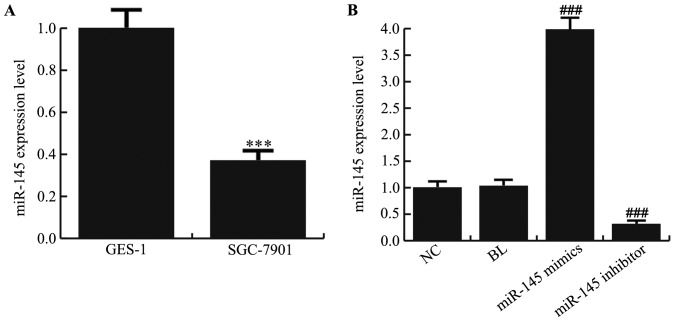

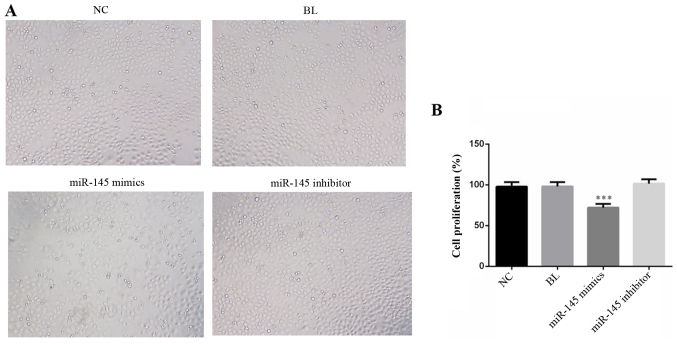

miR-145 inhibits the proliferation of SGC-7901 cells

The RT-qPCR results demonstrated that the expression of miR-145 was significantly decreased in the gastric cancer cell line SGC-7901 compared with normal gastric epithelial GES-1 cells (Fig. 1A; P<0.001). To expand the limited understanding of the role served by miR-145 in gastric cancer cells, the effects of miR-145 gain and loss-of-function on SGC-7901 cells were examined. For this, miR-145 mimics, miR-145 inhibitor or NC were transfected into SGC-7901 cells, and RT-qPCR was performed to detect the transfection efficiency. As presented in Fig. 1B, miR-145 mimics significantly increased the expression level of miR-145 in SGC-7901 cells and the expression level of miR-145 was significantly decreased in the miR-145 inhibitor-transfected SGC-7901 cells (P<0.001). After transfection for 48 h, cell morphology was imaged (Fig. 2A), and cells were plated into 96-well plates to measure the absorbance. The MTT results demonstrated that transfection with miR-145 mimics significantly suppressed SGC-7901 cell proliferation compared with the NC (Fig. 2B; P<0.001).

Figure 1.

miR-145 is downregulated in SGC-7901 cells. (A) Relative miR-145 expression in the gastric cancer cell line SGC-7901 and normal gastric epithelial cells GES-1 was detected using reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction. (B) Relative miR-145 expression in SGC-7901 cells in different groups. ***P<0.001 vs. GES-1; ###P<0.001 vs. NC group. miR, micro RNA; NC, negative control; BL, blank.

Figure 2.

miR-145 mimics inhibits the proliferation of SGC-7901 cells. (A) Cell morphology was imaged with a microscope (magnification, ×200). (B) Cell proliferation was detected by an MTT assay. ***P<0.001 vs. NC group. miR, micro RNA; NC, negative control; BL, blank.

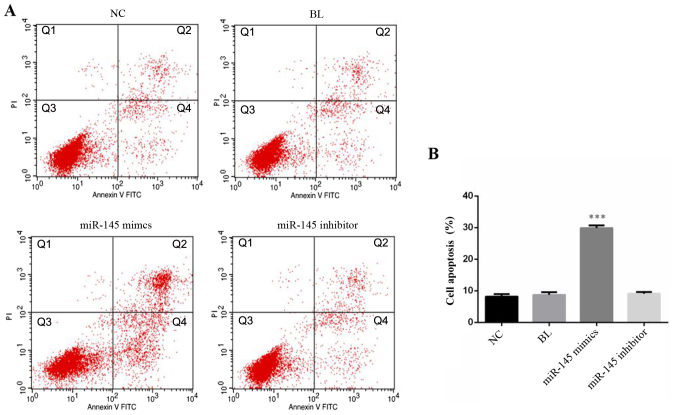

miR-145 mimics promotes SGC-7901 cell apoptosis

SGC-7901 cell apoptosis was detected 48 h after transfection with miR-145 mimics, miR-145 inhibitor or NC (Fig. 3A). Flow cytometry analysis revealed that early apoptosis and late apoptosis were upregulated in miR-145 mimics transfected SGC-7901 cells compared with the NC (Fig. 3B). These data demonstrated that overexpression of miR-145 induced gastric cancer cellular apoptosis.

Figure 3.

Effects of overexpression miR-145 on cellular apoptosis of gastric cancer cells. (A) Cellular apoptosis (Q1: Dead cells; Q2: Late apoptosis; Q3: Normal cells; Q4: Early apoptosis) was detected by flow cytometry and (B) the rate of apoptosis was analyzed. ***P<0.001 vs. NC group. miR, micro RNA; NC, negative control; BL, blank; PI, propidium iodide; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate.

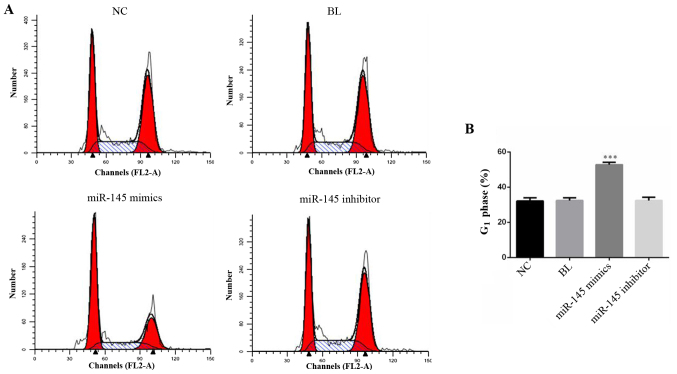

miR-145 mimics induces cell-cycle arrest in SGC-7901 cells

Cell cycle analysis was used to examine the possible mechanism by which miR-145 inhibits proliferation. SGC-7901 cells, which were transfected with miR-145 mimics, miR-145 inhibitor or NC for 48 h, were detected by cell cycle analysis (Fig. 4A). The results suggested that overexpression of miR-145 significantly increased the percentage of cells in the G1 phase (Fig. 4B; P<0.001).

Figure 4.

miR-145 mimics induces cell-cycle arrest in SGC-7901 cells. (A) Cell cycle was detected by flow cytometry and (B) the percentage of G1 phase was analyzed. ***P<0.001 vs. NC group. miRNA, micro RNA; NC, negative control; BL, blank.

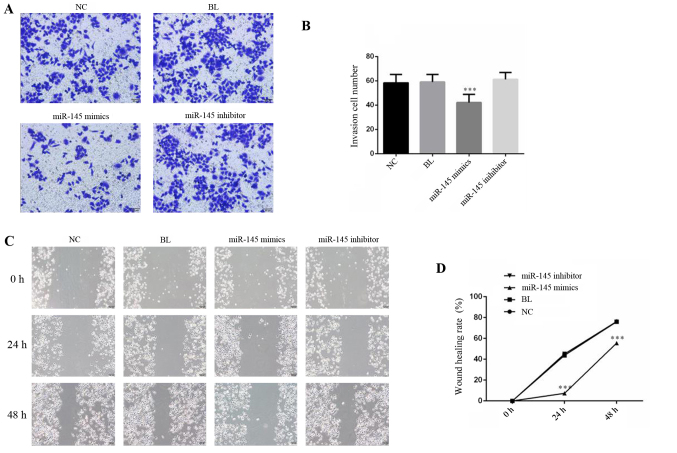

Overexpression of miR-145 inhibits the invasion and migration of gastric cancer cells

To investigate the metastatic effect of miR-145 on SGC-7901 cells, migration and invasion assays were performed. The mimics of miR-145 and NC were transfected into SGC-7901 cells, which were identified to express relatively low levels of miR-145. The results of the Matrigel Transwell assay demonstrated that numbers of adhesive cells in the miR-145 mimics group was significantly decreased compared with the NC group (Fig. 5A and B; P<0.05). To examine whether cell migration ability was similarly suppressed by miR-145 overexpression, a scratch wound healing assay was performed. The results revealed that overexpression of miR-145 suppressed the wound healing rate of SGC-7901 cells compared with the NC group (Fig. 5C and D). Collectively, these data suggested that miR-145, as a regulatory molecule, is involved in gastric cancer cell migration and invasion.

Figure 5.

Effect of miR-145 on SGC-7901 cell invasion and migration. (A) Transwell assay was used to detect cell invasion and (B) invasive cell number was determined. (C) Scratch wound healing assays were performed to detect cell migration at 0, 24 and 48 h after scratch wound formation, images were obtained (magnification, ×200) and (D) analyzed. ***P<0.001 vs. NC group. miRNA, micro RNA; NC, negative control; BL, blank.

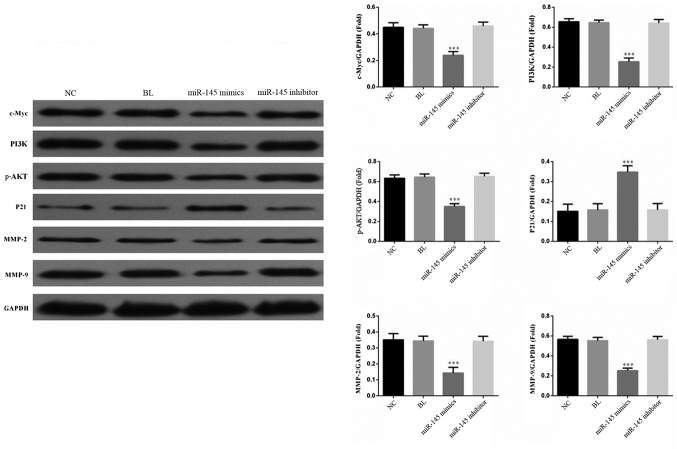

miR-145 inhibits SGC-7901 cell growth by regulating the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway

To further investigate the molecular mechanisms regulated by miR-145, western blotting was performed to detect c-Myc, PI3K, p-AKT, MMP2 and MMP9 in SGC-7901 cells transfected with the miR-145 mimics, miR-145 inhibitor or NC. The data demonstrated that overexpression of miR-145 decreased protein expression levels of c-Myc, PI3K, p-AKT, MMP2 and MMP9 (Fig. 6). Western blot analysis demonstrated that the expression of p21, a cell cycle regulatory protein, was significantly increased, suggesting that miR-145 may block the cell cycle by regulating p21 expression. These data revealed the potential molecular mechanism of miR-145 inhibiting gastric cancer progression involves these proteins.

Figure 6.

miR-145 inhibits SGC-7901 cell growth by regulating the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. miR-145 overexpression significantly decreased the expression of PI3K, p-AKT, c-Myc, MMP2 and MMP9 while increased the expression of p21. ***P<0.001 vs. NC group. miRNA, micro RNA; NC, negative control; BL, blank; PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinase; p-AKT, phosphorylated protein kinase B; c-Myc, Myc proto-oncogene protein; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase.

Discussion

In previous years, research has revealed the occurrence and development of gastric cancer. Gastric cancer remains one of the most common malignancies and causes approximately one million novel cases each year in the world (26). miRNA has been reported to express abnormalities or mutations in various tumors. Previous studies demonstrated that miR-145 is commonly downregulated in various types of cancer (27–30), thus in the present study, the role of miR-145 in gastric cancer was evaluated.

The miR-145 expression was examined in gastric cancer SGC-7901 cells and normal gastric epithelial cells GES-1. Consistent with a previous study, the present study identified that the expression of miR-145 significantly decreased in gastric cancer cells (22). Furthermore, the role of miR-145 in gastric cancer was investigated. Transfection with miR-145 mimics suppressed SGC-7901 cell growth, induced cellular apoptosis and blocked cell cycle in the G1 phase. Overexpression of miR-145 was able to inhibit SGC-7901 cell invasion and migration. Collectively, miR-145 as a tumor suppressor may inhibit gastric cancer progression. Although the present results are consistent with previous studies (22–24), there were differences. The present study systematically studied the effect of miR-145 on biological behavior, including proliferation, apoptosis, migration, invasion and cell cycle distribution of gastric cancer cells for the first time, to the best of the authors' knowledge. Different from other previous studies, the effect of miR-145 downregulation on gastric cancer cells was additionally investigated. Furthermore, notably, a novel molecular mechanism of the influence of miR-145 on the biological behavior of gastric cancer cells was identified in the present study.

c-Myc, an oncogene, is involved in cell proliferation, transformation and cell death regulation (31). Increased c-Myc protein expression levels strongly contribute to the apoptotic stimuli of epithelial cells, including DNA damage (32). Therefore, the downregulation of c-Myc is necessary for cell cycle arrest (33). In the present study, c-Myc expression was significantly decreased in miR-145 overexpressed SGC-7901 cells. In addition, overexpression of miR-145 was able to inhibit the SGC-7901 cell proliferation and block cell cycle in G1 phase, which were consistent with a previous study (34). c-Myc may be a potential target of miR-145.

The PI3K/AKT signaling pathway may regulate a variety of biological functions. Activated AKT may induce a downstream phosphorylation cascade, regulation of cell growth and survival, proliferation and apoptosis, angiogenesis, cell migration and cell cycle and other cell activity and biological effects (35,36). In the present study, it was observed that overexpression of miR-145 in SGC-7901 cells decreased the protein expression level of PI3K and p-AKT. The present data suggested that miR-145 suppressed gastric cancer cell growth by regulating the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway.

The primary reason for the failure of gastric cancer treatment is cell infiltration and metastasis. The present study demonstrated that gastric cancer cell invasion and migration was suppressed by miR-145. In the MMP family, MMP2 and MMP9 are the most important enzymes to degrade type IV collagen and serve an important role in tumor vascularization, tumor cell invasion and metastasis formation (37). Therefore, the expression level of MMP2 and MMP9 were detected in the present study, and it was observed that MMP2 and MMP9 protein were decreased in miR-145 mimics transfected SGC-7901 cells. These data suggested that miR-145 inhibited gastric cancer cell invasion and metastasis by regulating MMP2 and MMP9 expression.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that miR-145 is downregulated in gastric cancer cells. Furthermore, it was identified that miR-145 inhibited SGC-7901 cell proliferation and induced cellular apoptosis through repression of the pro-oncogene c-Myc. In addition, miR-145 suppressed gastric cancer cell invasion and metastasis by regulating MMP2 and MMP9 expression. Therefore, restoration of miR-145 may be utilized as a potential novel therapeutic strategy in gastric cancer in the future.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Project of National Clinical Research Base of Traditional Chinese Medicine in Jiangsu, China (grant no. JD201511).

Availability of data and materials

The analyzed data sets generated during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

JW and ZS assessed and analyzed the data, and contributed to the paper preparation. SY contributed to data analysis. FG collaborated to design the study. All authors collaborated to interpret the results and develop the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xu AM, Huang L, Liu W, Gao S, Han WX, Wei ZJ. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgery versus surgery alone for gastric carcinoma: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2014;9:e86941. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN, 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2893–2917. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Song Z, Wu Y, Yang J, Yang D, Fang X. Progress in the treatment of advanced gastric cancer. Tumour Biol. 2017;39:1010428317714626. doi: 10.1177/1010428317714626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Memon MA, Subramanya MS, Khan S, Hossain MB, Osland E, Memon B. Meta-analysis of D1 versus D2 gastrectomy for gastric adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 2011;253:900–911. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318212bff6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu AM, Huang L, Zhu L, Wei ZJ. Significance of peripheral neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio among gastric cancer patients and construction of a treatment-predictive model: A study based on 1131 cases. Am J Cancer Res. 2014;4:189–195. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang L, Xu A, Li T, Han W, Wu S, Wang Y. Detection of perioperative cancer antigen 72-4 in gastric juice pre-and post-distal gastrectomy and its significances. Med Oncol. 2013;30:651. doi: 10.1007/s12032-013-0651-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ghosn M, Tabchi S, Kourie HR, Tehfe M. Metastatic gastric cancer treatment: Second line and beyond. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:3069–3077. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i11.3069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hammond SM. An overview of microRNAs. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2015;87:3–14. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2015.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilson RC, Doudna JA. Molecular mechanisms of RNA interference. Annu Rev Biophys. 2013;42:217–239. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-083012-130404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guo H, Ingolia NT, Weissman JS, Bartel DP. Mammalian microRNAs predominantly act to decrease target mRNA levels. Nature. 2010;466:835–840. doi: 10.1038/nature09267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miska EA. How microRNAs control cell division, differentiation and death. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2010;15:563–568. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ueda T, Volinia S, Okumura H, Shimizu M, Taccioli C, Rossi S, Alder H, Liu CG, Oue N, Yasui W, et al. Relation between microRNA expression and progression and prognosis of gastric cancer: A microRNA expression analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:136–146. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70343-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Volinia S, Calin GA, Liu CG, Ambs S, Cimmino A, Petrocca F, Visone R, Iorio M, Roldo C, Ferracin M, et al. A microRNA expression signature of human solid tumors defines cancer gene targets. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:2257–2261. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510565103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Michael MZ, O'Connor SM, van Holst Pellekaan NG, Young GP, James RJ. Reduced accumulation of specific microRNAs in colorectal neoplasia. Mol Cancer Res. 2003;1:882–891. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu J, Guo H, Li H, Liu Y, Liu J, Chen L, Zhang J, Zhang N. MiR-145 regulates epithelial to mesenchymal transition of breast cancer cells by targeting Oct4. PLoS One. 2012;7:e45965. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 18.Wang F, Xia J, Wang N, Zong H. miR-145 inhibits proliferation and invasion of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in part by targeting c-Myc. Onkologie. 2013;36:754–758. doi: 10.1159/000356978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cho WC, Chow AS, Au JS. MiR-145 inhibits cell proliferation of human lung adenocarcinoma by targeting EGFR and NUDT1. RNA Biol. 2011;8:125–131. doi: 10.4161/rna.8.1.14259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sachdeva M, Mo YY. MicroRNA-145 suppresses cell invasion and metastasis by directly targeting mucin 1. Cancer Res. 2010;70:378–387. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cui SY, Wang R, Chen LB. MicroRNA-145: A potent tumour suppressor that regulates multiple cellular pathways. J Cell Mol Med. 2014;18:1913–1926. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lei C, Du F, Sun L, Li T, Li T, Min Y, Nie A, Wang X, Geng L, Lu Y, et al. miR-143 and miR-145 inhibit gastric cancer cell migration and metastasis by suppressing MYO6. Cell Death Dis. 2017;8:e3101. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2017.493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Qiu T, Zhou X, Wang J, Du Y, Xu J, Huang Z, Zhu W, Shu Y, Liu P. miR-145, miR-133A and miR-133b inhibit proliferation, migration, invasion and cell cycle progression via targeting transcription factor Sp1 in gastric cancer. FEBS Lett. 2014;588:1168–1177. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.02.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gao P, Xing AY, Zhou GY, Zhang TG, Zhang JP, Gao C, Li H, Shi DB. The molecular mechanism of microRNA-145 to suppress invasion-metastasis cascade in gastric cancer. Oncogene. 2013;32:491–501. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guimarães RM, Muzi CD. Trend of mortality rates for gastric cancer in Brazil and regions in the period of 30 years (1980–2009) Arq Gastroenterol. 2012;49:184–188. doi: 10.1590/S0004-28032012000300003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luo X, Burwinkel B, Tao S, Brenner H. MicroRNA signatures: Novel biomarker for colorectal cancer? Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20:1272–1286. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang X, Tang S, Le SY, Lu R, Rader JS, Meyers C, Zheng ZM. Aberrant expression of oncogenic and tumor-suppressive microRNAs in cervical cancer is required for cancer cell growth. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2557. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iorio MV, Visone R, Di Leva G, Donati V, Petrocca F, Casalini P, Taccioli C, Volinia S, Liu CG, Alder H, et al. MicroRNA signatures in human ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2007;67:8699–8707. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu X, Sempere LF, Galimberti F, Freemantle SJ, Black C, Dragnev KH, Ma Y, Fiering S, Memoli V, Li H, et al. Uncovering growth-suppressive MicroRNAs in lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:1177–1183. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hermeking H, Eick D. Mediation of c-Myc-induced apoptosis by p53. Science. 1994;265:2091–2093. doi: 10.1126/science.8091232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maclean KH, Keller UB, Rodriguez-Galindo C, Nilsson JA, Cleveland JL. c-Myc augments gamma irradiation-induced apoptosis by suppressing Bcl-XL. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:7256–7270. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.20.7256-7270.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cannell IG, Kong YW, Johnston SJ, Chen ML, Collins HM, Dobbyn HC, Elia A, Kress TR, Dickens M, Clemens MJ, et al. p38 MAPK/MK2-mediated induction of miR-34c following DNA damage prevents Myc-dependent DNA replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:5375–5380. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910015107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shao Y, Qu Y, Dang S, Yao B, Ji M. MiR-145 inhibits oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) cell growth by targeting c-Myc and Cdk6. Cancer Cell Int. 2013;13:51. doi: 10.1186/1475-2867-13-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.De Luca A, Maiello MR, D'Alessio A, Pergameno M, Normanno N. The RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK and the PI3K/AKT signalling pathways: Role in cancer pathogenesis and implications for therapeutic approaches. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2012;16(Suppl 2):S17–S27. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2011.639361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aksamitiene E, Kiyatkin A, Kholodenko BN. Cross-talk between mitogenic Ras/MAPK and survival PI3K/Akt pathways: A fine balance. Biochem Soc Trans. 2012;40:139–146. doi: 10.1042/BST20110609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kessenbrock K, Plaks V, Werb Z. Matrix metalloproteinases: Regulators of the tumor microenvironment. Cell. 2010;141:52–67. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The analyzed data sets generated during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.