Abstract

The nanohybrid of electrochemically-reduced graphene oxide (ERGO) nanosheets decorated with MnO2 nanorods (MnO2 NRs) was modified on the surface of a glassy carbon electrode (GCE). Controlled potential reduction was applied for the reduction of graphene oxide (GO). The characterization was performed by scanning electron microscopy, X-ray diffraction and cyclic voltammetry. Compared with the poor electrochemical response at bare GCE, a well-defined oxidation peak of sunset yellow (SY) was observed at the MnO2 NRs-ERGO/GCE, which was attributed to the high accumulation efficiency as well as considerable electrocatalytic activity of ERGO and MnO2 NRs on the electrode surface. The experimental parameters for SY detection were optimized in detail. Under the optimized experiment conditions, the MnO2 NRs-ERGO/GCE showed good linear response to SY in concentration range of 0.01–2.0 μM, 2.0–10.0 μM and 10.0–100.0 μM with a detection limit of 2.0 nM. This developed method was applied for SY detection in soft drinks with satisfied detected results.

Keywords: colorant analysis, sunset yellow, MnO2 nanorods, electrochemical reduced graphene oxide, voltammetric determination

1. Introduction

Sunset Yellow (SY) is a water-soluble synthetic colorant, extensively used in the food industry because of its excellent color uniformity, low production cost, and high stability. However, the content of SY in foods must be strictly controlled and SY is not allowed to be added to fresh meat because it can cause allergies, diarrhea and other symptoms in sensitive people [1]. When the intake is too large, it will accumulate in the body and cause kidney and liver damage. When SY is used as food additive, the required content is less than 50 ppm [2]. Therefore, for food safety and human health it is quite important to develop a simple, rapid and sensitive method for the detection of SY.

At present, some analytical methods for SY detection have been reported, such as spectrophotometry [3], high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) [4,5], HPLC-mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS) [6], capillary electrophoresis [7,8], and fluorescence emission spectrometry [9]. Spectrophotometry, capillary electrophoresis and fluorescence techniques either suffer from low sensitivity, narrow linear ranges or high detection limits. Although the chromatographic methods can offer good selectivity and detection limits, they often require time-consuming detection processes and complex pre-treatment steps. Moreover, these instruments are rather complicated, expensive, and cannot be employed for on-site measurements. Compared with the above methods, the newly developed electrochemical methods have received more attention in practical applications due to their advantages of simplicity, low cost, high sensitivity, and convenience for in-situ detection. Some chemically modified electrodes have been reported for the electrochemical detection of SY, For example, a cetyltrimethylammonium bromide-functionalized montmorillonite calcium-modified carbon paste electrode (CTAB-MMT-Ca/CPE) [10], a Au nanoparticles/graphene-modified glassy carbon electrode (Au-RGO/GCE) [11], a gold nanorods-decorated graphene oxide-modified glassy carbon electrode (AuNRs-GO/GCE) [12], a platinum nanoparticles-functionalized graphene composite-modified glassy carbon electrode (CTAB-Gr-Pt/GCE) [13], a multi-walled carbon nanotubes and graphene oxide nanocomposite-modified glassy carbon electrode (GO/MWCNTs/GCE) [14], a ZnO/cysteic acid nanocomposite-modified glassy carbon electrode (ZnO/cysteic acid/GCE) [15], a bimetallic nanoparticle-functionalized graphene-modified glassy carbon electrode (PDDA-Gr-(Pd-Pt)/GCE; PDDA-Gr-(Pt-Cu)/GCE;PDDA-Gr-(Co-Ni)/GCE) [16], a chitosan/graphene-modified glassy carbon electrode (Chit-Gr/GCE) [17], etc. The performance of these modified electrodes is strongly dependent on the modified materials. Table 1 and Table 2 summarize the comparison and advantage data of the different modified electrodes in SY detection. Each approach has its particular sensitivity and is subject to various limitations. Therefore, it is still necessary to identify new materials to detect SY accurately and rapidly.

Table 1.

Performance comparison of different modified electrodes for SY detection.

| Modified Electrode | Sensitivity (μA/μM) | Repeatability (RSD%) | Reproducibility (RSD%) | Stability | Interferences | Recovery (%) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTAB-MMT-Ca/CPE | 20.31 | poor repeatability | 3.9 | - | 1 mM vitamin C, glucose, glycine, citric acid, benzoic acid; 1 μM Tartrazine, quinoline yellow; 5 μM sudan red, amaranth had no interference |

- | [10] |

| Au-RGO/GCE | 0.496 | 2.56 | 5.32 | 20 days | 0.5 mM of NaCl, MgCl2, NaNO3, Fe (NO3)3, glucose, tartrazine and new coccine had no interference | 99.24–101.94 | [11] |

| ERGO-AuNRs/GCE | 0.0334 | 3.5 | 8.1 | 21 days | 60 μM Zn2+, Cu2+, Mg2+, Ca2+, Fe3+, Cl−, NO3−, H2PO4−, HCO3−, HPO42−, CO32−; 12 μM glucose, saccharin, sucrose, glycine, citric acid, ascorbic acid; 6 μM quinoline yellow; ponceau 4R had no interference | 89.4–108.8 | [12] |

| CTAB-Gr-Pt/GCE | 2.5481 | - | - | - | 1.0 mM citric acid, benzoic acid, glucose; 0.2 mM tartrazine, amaranth, allura red had no interference | 96.25–98.25 | [13] |

| GO/MWCNTs/GCE | 0.4636 | 3.7 | - | 30 days | 0.1 mM Cu2+, Zn2+, Na+, Cl−, K+, Mg2+, SO42−, Ca2+, CO32−, NH4+, NO3−; 10 μM uric acid, urea, glucose, oxalate, glycine, alanine, L-cysteine, L-tyrosine, L-glutamine, L-serine, valine had no interference | 101.5–104.0 | [14] |

| ZnO/Cysteic acid/GCE | 2.81 | 2.55 | 4.46 | 30 days | 1.0 mM NH4+, Ca2+, Fe3+, Al3+, Zn2+, Mn2+, Mg2+, Br2212, CO32−, SO42−, 0.2 mM starch, sucrose, glucose, uric acid, vitamin B2, vitamin B6, ascorbic acid, dopamine, citric acid; 20 μM amaranth, allura red and quinolone yellow had no interference | 95.7–101.3 | [15] |

| PDDA-Gr-(Pd-Pt)/GCE, PDDA-Gr-(Pt-Cu)/GCE, PDDA-Gr-(Co-Ni)/GCE | - | - | - | - | 5.0 mM Mg2+, K+, Ca2+, Zn2+, Cl−, SO42−, NO3−; 0.5 mM citric acid, glucose, ascorbic acid; 0.01 mM allura red, amaranth had no interference | 95.3–103 | [16] |

| Chit-Gr/GCE | 0.018 | 3.5 | - | - | 1.0 μM citric acid and ascorbic acid had no interference | 92.65–97.00 | [17] |

| MnO2 NRs-ERGO/GCE | 4.0802 | 2.56 | 5.32 | 14 days | 1.0 mM Zn2+, Cu2+, Fe3+, Ca2+, Mg2+, Cl−, NO3−, SO42−, CO32−, glucose, oxalate, sucrose, glycine, alanine, L-cysteine, L-glutamine, L-serine, caffeine, benzoic acid; 0.5 mM vitamin C; 20 μM amaranth, allura red, brilliant blue, and 10 μM tartrazine, quinoline yellow | 97.7–102.8 | This work |

Table 2.

Comparison of the linear range and detection limit with other modified electrodes for the determination of SY.

| Modified Electrodes | Technique | Supporting Electrolyte | Linear Range/μM | Correlation Coefficient | Detection Limit/μM | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTAB-MMT-Ca/CPE | i DPV | 0.1 M acetate buffer (pH 4.0) | 0.0025 to 0.2 | 0.995 | 0.00071 | [10] |

| Au-RGO/GCE | DPV | 0.1 M PBS buffer (pH 4.0) | 0.002–2.145 | 0.993 | 0.002 | [11] |

| 2.145–109.145 | 0.994 | |||||

| AuNRs-GO/GCE | DPV | 0.1 M PBS (pH 6.0) | 0.01–3.0 | 0.995 | 0.0024 | [12] |

| CTAB-Gr-Pt/GCE | DPV | 0.1 M PBS (pH3.0) | 0.08–10.0 | 0.9984 | 0.0042 | [13] |

| GO/MWCNTs/GCE | j LSV | 0.1 M PBS buffer (pH 5.0) | 0.09–8.0 | 0.9982 | 0.025 | [14] |

| ZnO/Cysteic acid/GCE | DPV | 0.1 M PBS buffer (pH 5.0) | 0.1–3.0 | 0.9977 | 0.03 | [15] |

| PDDA-Gr-(Pd-Pt)/GCE | DPV | 0.1 M PBS buffer (pH 3.0) | 0.02–10.0 | - | 0.006 | [16] |

| PDDA-Gr-(Pt-Cu)/GCE | 0.02–10.0 | 0.004 | ||||

| PDDA-Gr-(Co-Ni)/GCE | 0.008–10.0 | 0.002 | ||||

| Chit-Gr/GCE | CV | 0.1 M PBS buffer (pH 6.0) | 0.2–100 | 0.99 | 0.0666 | [17] |

| MnO2 NRs-ERGO/GCE | SDLSV | 0.3 M citrate buffer (pH 4.5) | 0.01–2 | 0.9983 | 0.002 | This work |

| 2–10 | 0.9965 | |||||

| 10–100 | 0.9944 |

Many researchers have been studying nanoparticles for electrochemical sensors, especially transition metal oxide nanoparticles such as Fe2O3 [18], Fe3O4 [19,20], Cu2O [21,22], Co3O4 [23], TiO2 [24], NiO [25], etc,, which have become the most popular material due to their unique properties of low cost, large surface area, good biocompatibility and distinct catalytic activity. Among them, non-toxic, economical and effective MnO2 nanoparticles have been extensively developed [26,27,28,29]. They can be easily synthesized into various shapes, including rods, porous materials, plates, tubes, wires, spheres and many others [30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37]. The electrochemical properties of MnO2 nanoparticles can be easily adjusted by tailoring their shape or morphology [38]. MnO2 nanorods (MnO2 NRs) are tiny, rod-like nanoparticles which have many interesting functions based on their anisotropic shapes. However, the poor dispersibility and the poor conductivity of MnO2 NRs have limited their utility in electrochemical sensors. To overcome these drawbacks, intensive efforts have been applied toward coupling MnO2 with graphene (GR), because GR is an attractive electrode material with a high theoretical specific surface area (2520 m2/g) and a high electrical conductivity, and a good candidate as a carrier [39,40]. The incorporation of GR with MnO2 can produce synergistic effects leading to improved conductivity, enhanced catalytic activity and improved stability of the MnO2 nanoparticles. In previous studies, different crystalline forms and morphologies of the MnO2 nanoparticles were assembled for electrode decoration by using GR [41,42,43]. The synergistic effect is outstanding, which confers them a great potential to replace conventional catalysts. However, as for the preparation of such compounds, conventional methods usually require complex separation processes, including multiple filtration stages and high-speed centrifugation [44,45]. These are the main obstacles for practical applications. Therefore, the development of an effective method for preparing the MnO2–GR hybrid materials is of significant importance.

In our previous work, we proposed an electroreduction technology for the fabrication of MnO2–graphene hybrid materials with high efficiency and relatively low operating cost [46,47]. Graphene oxide (GO), a derivative of graphene, is highly hydrophilic and dispersible due to its large number of oxygen-containing functional groups. Therefore, a dispersion of GO and MnO2 NRs was dropped onto the surface of a glassy carbon electrode (GCE), and then electrochemical reduction of GO was carried out. The conductivity of electrochemical reduced GO (ERGO) is much higher than that of GO due to the recovery of the conductive carbon conjugated networks. We found that this hybrid material showed superior electrocatalytic activity toward amaranth [46] and dopamine [47]. However, sensitive and rapid detection of SY using this hybrid material has not been reported yet.

In the present study, a MnO2 NRs-ERGO nanocomposite-modified GCE (denoted as MnO2 NRs-ERGO/GCE) has been prepared by a facile method. The morphology of the nanocomposite was investigated by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and X-ray diffraction (XRD), and the electrochemical behaviour of the modified electrode was studied by cyclic voltammetry (CV) and second-order derivative linear sweep voltammetry (SDLSV). Due to electrocatalytic activity of MnO2 NRs-ErGO/GCE toward SY oxidation, a novel electrochemical sensing platform for SY was developed. The analytical characteristics of the sensor were studied in detail and its applicability toward SY detection in real samples was evaluated.

2. Results

2.1. Characteristics of the Nanohybrid

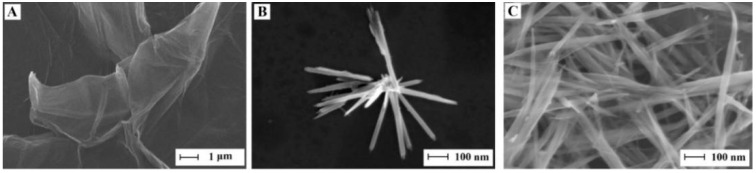

The morphology of the materials was revealed by SEM studies. Wrinkled, aggregated, and thin sheets of GO can be observed in Figure 1A. As seen in Figure 1B, the MnO2 NRs had a uniform nanorods-like structure (~44 nm in diameter and ~800 nm in length on an average). In Figure 1C, the MnO2 NRs are randomly assembled with the ERGO flakes. The ERGO flakes were self-assembled in a layered structure with MnO2 NRs embedded between the layers, suggesting the MnO2 NRs were combined with ERGO successfully.

Figure 1.

SEM images of GO (A), MnO2 NRs (B), and MnO2 NRs-ERGO (C).

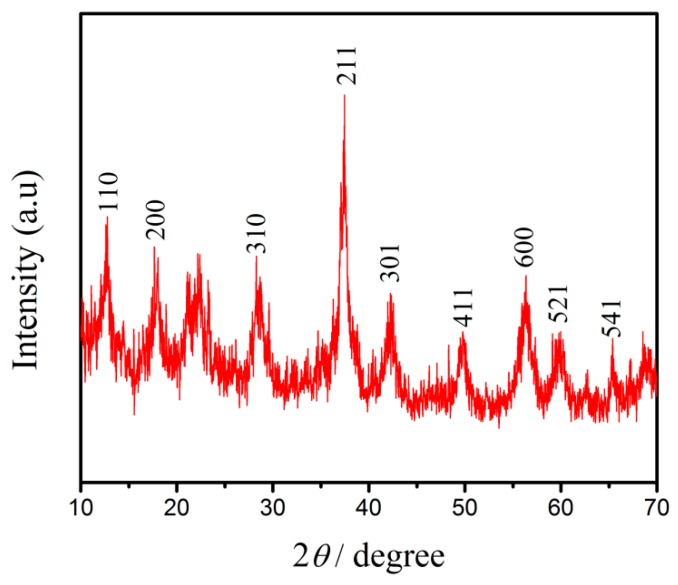

Figure 2 illustrates the XRD pattern of the MnO2 NRs recorded in the 2θ range of 10–70°. It was observed that the characteristic reflections of the MnO2 NRs were shown at 2θ = 12.1°, 18.0°, 29.3°, 37.5°, 42.1°, 50.1°, 56.5°, 60.5°, and 69.8°, corresponding to the lattice planes of (110), (200), (310), (211), (301), (411), (600), (521) and (541), which were well coincided with the standard data file (JSPDS 44-0141), suggesting α-MnO2was perfectly crystallized.

Figure 2.

XRD pattern of MnO2 NRs.

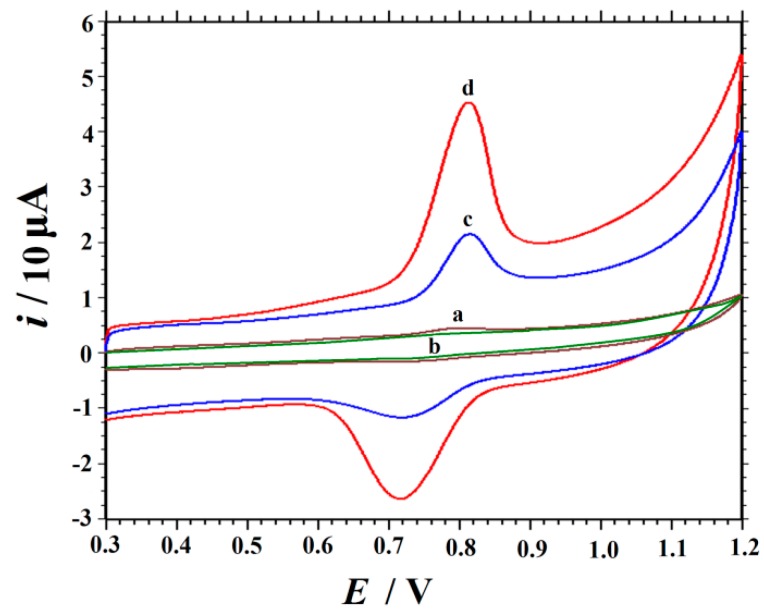

2.2. Electrochemical Behaviors of SY at Different Electrodes

The cyclic voltammograms (CVs) of 0.1 mM SY in 0.3 M citric acid-sodium citrate buffer (pH = 4.5) solution at different modified electrodes within the potential range from 0.3 to 1.2 V at a scan rate of 0.1 V/s are exhibited in Figure 3, where it can be seen that there is a very small oxidation peak (Epa = 0.804 V, ipa = 1.693 μA) of SY on bare GCE, indicating a slow electron transfer kinetic. At GO/GCE, the oxidation peak current of SY was smaller than that of GCE because of the low conductivity of GO. At ERGO/GCE, an improved oxidation peak (ipa = 23.34 μA) at 0.816 V and a greatly enhanced reduction peak (ipc = 10.88 μA) at 0.717 V were exhibited, indicating that ERGO was favorable for the electrocatalysis of SY. After ERGO was decorated with MnO2 NRs, a pair of well-defined redox peaks located at 0.814 V and 0.716 V appeared at the MnO2 NRs-ERGO/GCE. This pair of quasi-reversible peaks had stronger current responses (ipa = 61.73 μA, ipc = 35.48 μA) than the abovementioned electrodes. The oxidation peak current was 2.6, 50.6, and 36.5-fold those at ERGO/GCE, GO/GCE, and bare GCE, respectively. These results proved that MnO2 NRs-ERGO could readily facilitate electron transfer. MnO2 NRs has excellent electrocatalytic activity, which can be used as an electronic mediator to promote the transfer of electrons between the electrode and SY. From the SEM image B in Figure 1, it can be seen that regular high purity nanorods provide good crystallization, which is favorable for reducing the probability of the recombination of electrons and thus reduces the chemical energy barrier. Additionally, the nanorods–like MnO2 in Figure 1C show good dispensability and no obvious agglomeration is observed, plus the significantly rough surfaces and abundant pores, so the specific surface area of MnO2 NRs-ERGO composite increases dramatically. It is well known that large specific surface areas provide more active sites and absorb more analytes. Moreover, these pores also allow the electrons to transit inside their interior pore channels, which would improve electrocatalytic activity [38]. ERGO has good conductivity and high specific surface area. Furthermore, the remained O-H functional groups on ERGO also act as catalytic active sites and contribute to the oxidation of SY [48], thereby improve the performance of the modified electrode.

Figure 3.

Cyclic voltammograms of 0.1 mM SY recorded at GCE (a), GO/GCE (b), ERGO/GCE (c) and MnO2 NRs-ERGO/GCE (d) in 0.3 M citric acid-sodium citrate buffer (pH 4.5), scan rate 0.1 V/s.

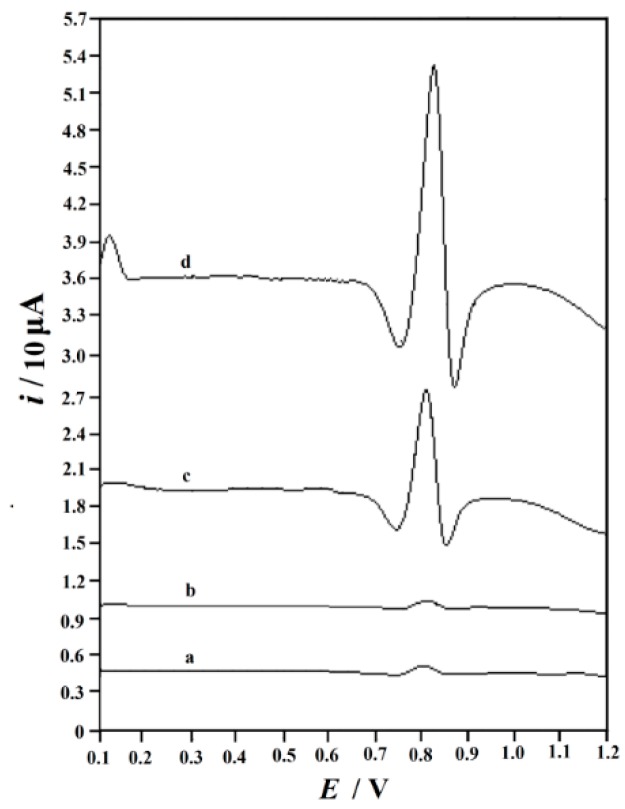

The electrochemical behavior of SY on the surface of GCE, GO/GCE, ERGO/GCE, and MnO2 NRs-ERGO/GCE was also studied using second derivative linear sweep voltammetry (SDLSV), and the results are shown in Figure 4. On the surface of GCE (curve a), the oxidation peak of SY was very weak (ipa = 1.537 μA). When using the GO/GCE (curve b), the oxidation peak current of SY decreased slightly (ipa = 1.244 μA). However, the oxidation peak of SY at 0.816 V was enhanced significantly (ipa = 24.30 μA) on the surface of ERGO/GCE (curve c), indicating the superiority of ERGO due to its good conductivity, big surface area, and electrocatalytic ability towards SY. While on MnO2 NRs-ERGO/GCE the biggest peak current of 60.08 μA appeared at 0.814 V (curve d). The remarkable peak current enlargement revealed that MnO2 NRs-ERGO/GCE exhibited strong signal enhancement toward the oxidation of SY. From the comparison, we clearly found that MnO2 NRs-ERGO facilitated the oxidation of SY, and was more sensitive for SY detection.

Figure 4.

Second-order derivative linear scan voltammograms of 0.1 mM SY recorded at GCE (a), GO/GCE (b), ERGO/GCE (c) and MnO2 NRs-ERGO/GCE (d) in 0.3 M citric acid-sodium citrate buffer (pH 4.5). Accumulation potential: 0.1 V, accumulation time: 180 s, scan rate 0.1 V/s.

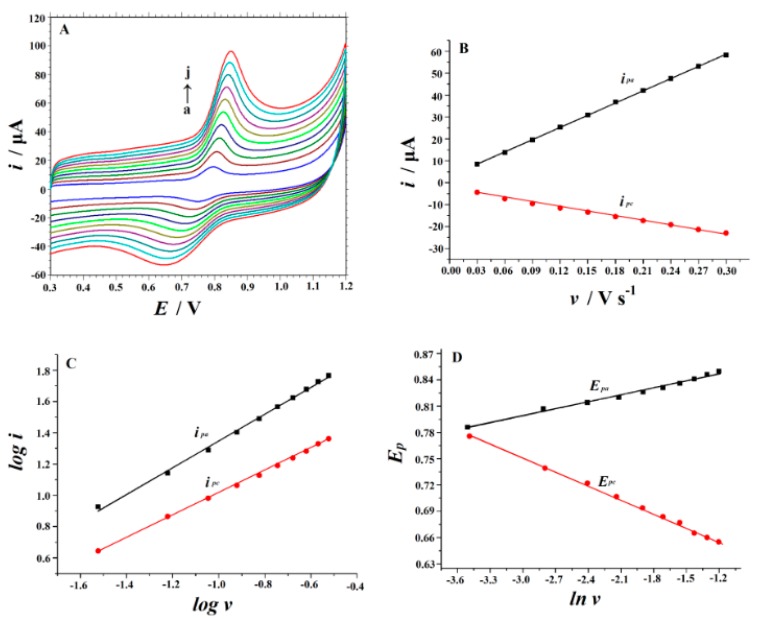

2.3. Effect of Scan Rate

In order to investigate the reaction kinetics of SY on the MnO2 NRs-ERGO/GCE, cyclic voltammograms with different scan rates were recorded (Figure 5A). As shown in Figure 5B, the anodic peak current (ipa) and cathodic peak current (ipc) of SY were linearly proportional to the scan rate (v) ranging from 0.03 to 0.3 V/s. The linear equations were as follows, indicating that the electrochemical process of SY is mainly controlled by adsorption:

| ipa (μA) = 186.04v (V s−1) + 2.9024 (R2 = 0.9998) | (1) |

| ipc (μA) = −67.257v (V s−1) −3.1713 (R2 = 0.996) | (2) |

Figure 5.

(A) Cyclic voltammograms of 10 μM SY at MnO2 NRs-ERGO/GCE with different scan rates. Curves (a–j) are obtained at 30, 60, 90, 120, 150, 180, 210, 240, 270 and 300 mV/s, respectively. (B) The plot for the dependence of peak current on scan rate. (C) The relationship between log ip and log v. (D) The relationship between Ep and ln v.

Figure 5C illustrates the relationships between log i vs. log v. The corresponding equations can be expressed as follows:

| log ipa (μA) = 0.855 log v (V s−1) +2.2022 (R2 = 0.997) | (3) |

| log ipc (μA) = 0.7101 log v (V s−1) +1.7241 (R2 = 0.9990) | (4) |

The slopes obtained were 0.855 and 0.7101 (approximately equal to 1), confirming the adsorption-controlled nature of the electrode process of SY. Meanwhile, as depicted in Figure 5D, the anodic peak potentials (Epa) and cathodic peak potentials (Epc) of SY are linearly related to the Napierian logarithm of scan rate (ln v) in the range of 0.03–0.3 V/s. The equations are found to be:

| Epa (V) = 0.0314 ln v (V/s) + 0.8864 (R2 = 0.996) | (5) |

| Epc (V) = −0.0517 ln v (V/s) +0.5957 (R2 =0.990) | (6) |

Based on Laviron’s model [49], the slopes of the line for Epa and Epc can be expressed as RT/(1–α) nF and RT/αnF, respectively. Therefore, the values of the electron-transfer coefficient (α) and the electron-transfer number (n) can be calculated to be 0.38 and 1.31, respectively.

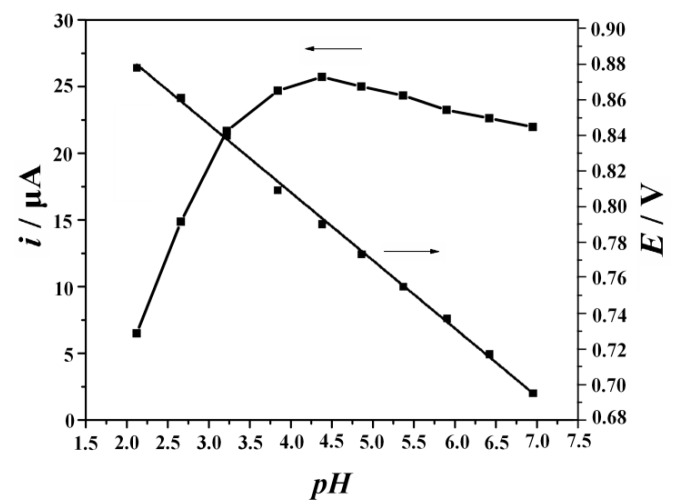

2.4. Effect of Buffer pH

The electrochemical response of SY on the MnO2 NRs-ERGO/GCE was investigated in 0.3 M citric acid-sodium citrate buffer at different pH values ranging from 2.0 to 8.0. As can be seen from Figure 6, the maximum oxidation peak current was obtained at pH 4.5 and it decreased gradually with the further increase of the pH value. Therefore, in the following experiments, pH 4.5 was chosen as the optimal pH value for SY determination. At the same time, the peak potential was found to be shifted negatively with the increase of buffer pH, indicating that proton participate in the electrochemical reaction. A linear regression equation was obtained as:

| Epa (V) = −0.0481 pH + 0.9972 (R2 = 0.9992) | (7) |

Figure 6.

Effects of pH on the current response and potential response of 10 μM SY. Accumulation potential: 0.1 V, accumulation time: 180 s, scan rate 0.1 V/s.

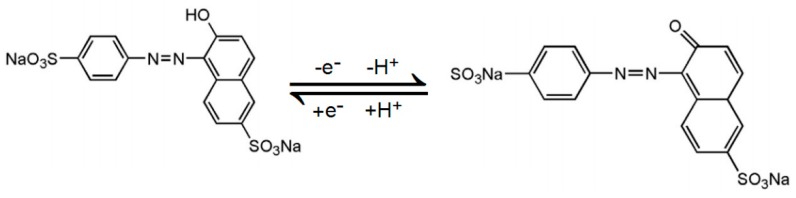

The slope of −0.0481 was close to the theoretical value of −0.059 V/pH, indicating that the number of electrons involved in SY oxidation is equal to the number of protons. According to the above results, the electrooxidation of SY on MnO2 NRs-ERGO/GCE was a one-electron one-proton process. The mechanism of its electrochemical process can be expressed as Scheme 1.

Scheme 1.

The electrode reaction mechanism for SY on the MnO2 NRs-ERGO/GCE.

2.5. Effect of Accumulation Conditions

Because the oxidation of SY on MnO2 NRs-ERGO/GCE is controlled by adsorption, the influence of accumulation conditions cannot be ignored. The effect of the accumulation potential and accumulation time on the oxidation current of 10 μM SY was investigated. It was revealed that when the accumulation potential shifted from −0.30 to 0.30 V, the current of SY changed slightly. Consequently, accumulation was carried out at the initial potential. The effect of accumulation time on the currents of SY was also investigated. The current increased significantly with the prolongation of accumulation time from 0 to 180 s. However, when the accumulation time exceeded 180 s, the current increased slowly, which indicated that the adsorption of SY on the electrode surface was supersaturated. Therefore, the accumulation time of 180 s was selected to determine SY.

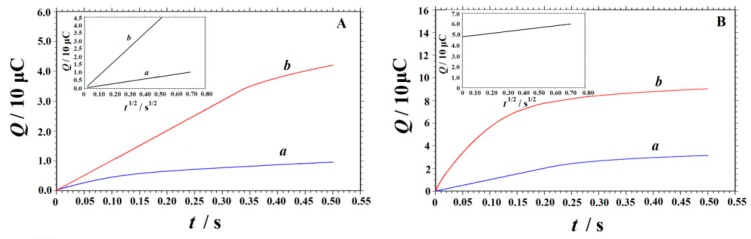

2.6. Chronocoulometry

According to the expression given by Anson [50], the electrochemical effective surface areas of bare GCE and MnO2 NRs-ERGO/GCE can be obtained by chronocoulometry:

| Q = 2nFAcD1/2π−1/2t1/2 + Qdl + Qads | (8) |

In the formula, A is the surface area of the working electrode, c is the substrate concentration, D is the diffusion coefficient, Qdl is the double layer charge, which can be eliminated by background subtraction, Qads is the adsorption charge. This experiment was performed in 1.0 mM K3[Fe(CN)6] solution containing 1.0 M KCl, where the diffusion coefficient of K3[Fe(CN)6] is 7.6 × 10−6 cm2 s−1 [51]. According to the experiment results (shown in Figure 7A), A was calculated to be 0.061 cm2 and 0.293 cm2 for GCE and MnO2 NRs-ERGO/GCE, respectively. These results showed that the effective surface area of the modified electrode increased obviously, which would improve the current response and decrease the detection limit.

Figure 7.

(A) Plot of Q–t curves of GCE (a) and MnO2 NRs-ERGO/GCE (b) in 1.0 mM K3[Fe(CN)6] containing 1.0 M KCl. Insert: Plot of Q–t1/2 curves on GCE (a) and MnO2 NRs-ERGO/GCE (b). (B) Plot of Q–t curves of the MnO2 NRs-ERGO/GCE in 0.3 M citric acid-sodium citrate buffer (pH 4.5) in the absence (a) and presence (b) of 0.1 mM SY. Insert: Plot of Q–t 1/2 curve on MnO2 NRs-ERGO/GCE after background subtracted.

The electrooxidation of SY at the MnO2 NRs-ERGO/GCE was also studied by chronocoulometry. The corresponding chronocoulometric curves are displayed in Figure 7B. The diffusion coefficient D and the adsorption charge Qads can be determined by Equation (8). As shown in the insert of Figure 7B, the relationship between Q and t1/2 was shown as a straight line after background subtraction. The slope was 1.652 × 10−5 C·s−1/2 and the intercept (Qads) was 4.813 × 10−5 C. As n = 1, A = 0.293 cm2, and c = 0.1 mM, D was calculated to be 2.68 × 10−5 cm2·s−1. According to the equation Qads = nFAΓs, the adsorption capacity Γs was 1.70 × 10−9 mol·cm−2. These results confirmed the remarkable enhancement effect of MnO2 NRs-ERGO for SY oxidation.

2.7. Analytical Properties

2.7.1. Repeatability, Reproducibility and Stability

A solution containing 10 μM SY was used for the investigation of the repeatability, reproducibility and stability of MnO2 NRs-ERGO/GCE by SDLSV. Repetitive determinations were carried out on a single electrode. The used MnO2 NRs-ERGO/GCE could be regenerated easily by voltammetric sweeps between 0.0 V to 1.2 V in a blank solution. The relative standard deviation (RSD) for the peak currents of SY based on seven replicates was obtained as 2.56%. The reproducibility was studied by fabricating seven modified electrodes which were applied for SY detection, the result of RSD with 5.32% revealed the excellent reproducible of MnO2 NRs-ERGO/GCE. The stability of the MnO2 NRs-ERGO/GCE was studied over a two-week period by periodically measuring the peak currents of SY. The electrode remained 94.8% of its initial response value after two weeks, indicating that the MnO2 NRs-ERGO/GCE had acceptable storage stability.

2.7.2. Interference Study

To evaluate the selectivity, the voltammetric response of 10 μM SY in the presence of different alien species were measured. The experimental data showed that no influences on the detection of 10 μM SY are found after addition of 1.0 mM Zn2+, Cu2+, Fe3+, Ca2+, Mg2+, Cl−, NO3−, SO42−, CO32−, glucose, oxalate, sucrose, glycine, alanine, L-cysteine, L-glutamine, L-serine, caffeine, benzoic acid; 0.5 mM vitamin C; 20 μM amaranth, allura red, brilliant blue, and 10 μM tartrazine, quinoline yellow (peak current change <10%). The results demonstrated that the MnO2 NRs-ERGO/GCE has a good selectivity for SY analysis in real samples.

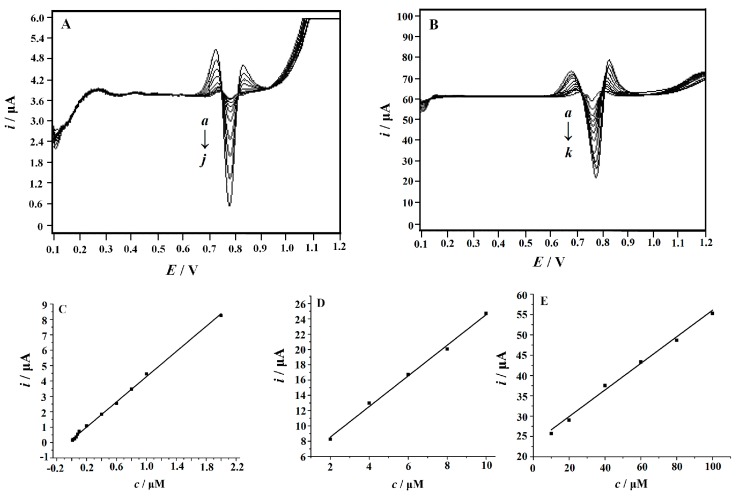

2.7.3. Calibration and Limit of Detection

Under the optimized experimental conditions, the quantitative analysis of SY was carried out by SDLSV. Figure 8 illustrates the SDLSV response of SY with different concentrations on MnO2 NRs-ERGO/GCE. A remarkable enhancement of peak current was observed with the increase of SY concentration. A good linearity was exhibited between the peak current of SY and its concentration in the range 0.01 μM~100 μM with three linear functions:

| i (µA) = 4.0802c (µM) + 0.1832 (c = 0.01μM~2 μM) (R2 = 0.9983) | (9) |

| i (µA) = 2.0014c (µM) + 4.5358 (c = 2 μM~10 μM) (R2 = 0.9965) | (10) |

| i (µA) = 0.326c (µM) + 23.086 (c = 10 μM~100 μM) (R2 = 0.9944) | (11) |

Figure 8.

Second-order derivative linear scan voltammograms obtained at MnO2 NRs-ERGO/GCE in 0.3 M citric acid-sodium citrate buffer (pH 4.5) containing different concentrations of SY. (A) From a to j: 0.01, 0.02, 0.04, 0.06, 0.08, 0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8 μM; (B) From a to k: 1.0, 2.0, 4.0, 6.0, 8.0 10, 20, 40, 60, 80, 100 μM; (C–E) the calibration plots of the concentration of SY versus peak current (C: 0.01~2.0 μM; D:2.0~10 μM; E: 10~100 μM). Accumulation potential: 0.1 V, accumulation time: 180 s, scan rate 0.1 V/s.

The limit of detection (LOD) was estimated to be 2.0 nM (S/N = 3). As shown in Table 1 and Table 2, the performance of MnO2 NRs-ERGO/GCE is comparable to or superior to that of the previously reported modified electrodes [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. In addition, this method has made remarkable improvements in simplifying the preparation of electrode, reducing cost and saving time, which proved that the electrode have good analytical performance and can be used for SY detection in real samples.

2.8. Practical Applications

The practical application of MnO2 NRs-ERGO/GCE for SY determination in real samples was testified in soft drinks with different China’s famous brands (Unified Xiangchenduo, Huiyuan Juice, Wahaha, Farmer’s Orchard, China). Before analysis by SDLSV, the samples were filtered to remove any suspended solids. The concentration of SY was obtained by the standard addition method. The results are listed in Table 3, where the contents of SY can be found to be 4.24~8.37 μM, and the recoveries were between 97.7% and 102.8%. In addition, the contents of SY were determined by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) to verify the accuracy of the new method. The results showed that the results obtained by HPLC and MnO2 NRs-ERGO/GCE were consistent, which indicates that the new method is accurate and feasible.

Table 3.

Determination of SY in beverage samples (n = 4).

| Sample a | Found b/μM | Added/μM | Total Found b/μM | Recovery/% | Content Determined by HPLC b/μM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| unified xiangchenduo | 4.24 (±0.16) | 4.00 | 8.35 (±0.03) | 102.8 | 4.28 (±0.18) |

| huiyuan juice | 6.28 (±0.31) | 6.00 | 12.14 (±0.11) | 97.7 | 6.17 (±0.34) |

| wahaha | 8.37 (±0.37) | 8.00 | 16.28 (±0.17) | 98.9 | 8.45 (±0.46) |

| farmer’s orchard | 5.65 (±0.23) | 5.00 | 10.76 (±0.47) | 101.0 | 5.52 (±0.24) |

a All samples were collected from local supermarkets. b Average ± confidence interval, the confidence level is 95%.

3. Experimental

3.1. Chemicals and Solutions

Potassium permanganate (KMnO4), graphite powder, manganese sulfate (MnSO4) were provided by Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Sunset yellow (SY) was supplied by Aladdin (Shanghai, China). All analytical grade reagents were used as received without further purification. 0.04524 g of SY was dissolved in 100.00 mL deionized water to prepare a 1.0 mM standard stock solution. A series of low concentration working solutions were prepared by further dilution of the stock solution with water. 0.3 M citric acid-sodium citrate buffer with a pH of 4.5 was used as supporting electrolyte.

3.2. Instruments

The characterization was implemented on a Hitachi S-4800 scanning electron microscope (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) at an accelerating voltage of 30 kV and a powder X-ray diffractometer (PANalytical, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) with Cu Kα radiation (0.1542 nm). Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) was finished on a CHI 660E electrochemical workstation (Chenhua Corp. Shanghai, China). Second derivative linear sweep voltammetry (SDLSV) was carried out on a JP-303E polarographic analyzer (Chengdu Instrument Factory, Chengdu, China). A traditional three-electrode system for all electrochemical experiments was composed of a bare or modified glassy carbon electrode as working electrode, a platinum wire as auxiliary electrode and a saturated calomel electrode (SCE) as reference electrode. A pH-3c exact digital pH meter (Shanghai Leichi Instrument Factory, Shanghai, China) was used for solution pH measurements.

3.3. Preparation of GO-MnO2 NRs Nanocomposites

MnO2 NRs was synthesized by a hydrothermal method according to Gan et al. [38]. MnO2 NRs dispersions (1.0 mg/mL) were obtained by addition of MnO2 NRs (10 mg) to deionized water (10 mL) and ultrasonication for 1 h. Graphite oxide was prepared using a modified Hummer’s method according to our previous report [21]. GO was then exfoliated by dispersing GO (20 mg) in deionized water (20 mL), followed by ultrasonication treatment for 2 h. Afterwards, it was centrifuged at 6000 rpm for 30 min in order to remove the unexfoliated graphite oxide and unoxidized graphite. Then MnO2 NRs dispersion (5.0 mL, 1.0 mg/mL) was very slowly dropped into GO aqueous solution (5.0 mL) and ultrasonically dispersed for 2 h. A homogeneous black dispersion was obtained

3.4. Electrode Fabrication

Before modification, the GCE with a diameter of 3 mm was polished on silk with 0.05 μM of α-Al2O3 slurry. After that, it was washed thoroughly with deionized water and cleared in anhydrous ethanol and deionized water in an ultrasonic bath. 5.0 μL of the obtained MnO2 NRs-GO dispersion was coated on the GCE surface and dried under an infrared lamp, followed by electrochemically reduction at a constant potential of −1.2 V for 120 s in a phosphate buffer solution (pH 6.5). The obtained modified electrode was denoted as MnO2 NRs-ERGO/GCE. For comparison, GO/GCE and ERGO/GCE were also prepared by the similar way.

4. Conclusions

This study provides a simple and practical method for preparing the nanohybrid of electrochemical reduced graphene oxide decorated with manganese dioxide nanorods (MnO2 NRs-ERGO), and the MnO2 NRs-ERGO-modified GCE exhibited superior electrocatalytic ability towards the oxidation of SY, which can be attributed to the strong catalytic activity of MnO2 NRs, high adsorption capacity and excellent conductivity of ERGO. The developed modified electrode exhibited excellent analytical performance such as fast response, low cost, high sensitivity and selectivity, as well as wide linear range and low detection limit for SY detection.

Author Contributions

P.D., Z.D. and Q.H. conceived and designed the experiments; Z.D., Y.W., Y.T., J.L. and G.L. performed the experiments; P.D. and Z.D. analyzed the data; G.L. and J.L. contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools; Z.D., Q.H. and P.D. wrote the paper.

Funding

This work was supported by the NSFC (61703152), Hunan Provincial Natural Science Foundation (2016JJ4010, 2018JJ3134), Postgraduates Innovation Fund of School of Life Science and Chemistry in HUT, Doctoral Program Construction of Hunan University of Technology, Project of Science and Technology Department of Hunan Province (18A273, 18C0522), Project of Science and Technology Plan in Zhuzhou (201706-201806) and Opening Project of Key Discipline of Materials Science in Guangdong (ESI Project GS06021, CNXY2017001, CNXY2017002 and CNXY2017003), The key Project of Department of Education of Guangdong Province (2016GCZX008) and The Project of Engineering Research Center of Foshan (20172010018).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Sample Availability: Samples of the compounds are available from the authors.

References

- 1.Rowe K.S., Rowe K.J. Synthetic food coloring and behavior: A dose response effect in a double-blind, placebo-controlled, repeated-measures study. J. Pediatr. 1994;125:691–698. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(06)80164-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Degs Y.S. Determination of three dyes in commercial soft drinks using HLA/GO and liquid chromatography. Food Chem. 2009;117:485–490. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.04.097. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aktas A.H., Ertokus G.P. Spectral simultaneous determination of tartrazine, allura red, sunset yellow and caramel in drink sample by chemometric method. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2010;29:107–116. doi: 10.1515/REVAC.2010.29.2.107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alves S.P., Brum D.M., Andrade É.C.B.d., Netto A.D.P. Determination of synthetic dyes in selected foodstuffs by high performance liquid chromatography with UV-DAD detection. Food Chem. 2008;107:489–496. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.07.054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Minioti K.S., Sakellariou C.F., Thomaidis N.S. Determination of 13 synthetic food colorants in water-soluble foods by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with diode-array detector. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2007;583:103–110. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gosetti F., Gianotti V., Polati S., Gennaro M.C. HPLC-MS degradation study of E110 Sunset Yellow FCF in a commercial beverage. J. Chromatogr. A. 2005;1090:107–115. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2005.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee K.S., Shiddiky M.J.A., Park S.H., Park D.S., Shim Y.B. Electrophoretic analysis of food dyes using a miniaturized microfluidic system. Electrophoresis. 2008;29:1910–1917. doi: 10.1002/elps.200700556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ryvolová M., Táborsky P., Vrábel P., Krásensky P., Preisler J. Sensitive determination of erythrosine and other red food colorants using capillary electrophoresis with laser-induced fluorescence detection. J. Chromatogr. A. 2007;1141:206–211. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2006.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dinc E., Baydan E., Kanbur M., Onur F. Spectrophotometric multicomponent determination of Sunset Yellow, tartrazine and allura red in soft drink powder by double divisor-ratio spectra derivative, inverse least-squares and principal component regression methods. Talanta. 2002;58:579–594. doi: 10.1016/S0039-9140(02)00320-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Songyang Y., Yang X., Xie S., Hao H., Song J. Highly-sensitive and rapid determination of sunset yellow using functionalized montmorillonite-modified electrode. Food Chem. 2015;173:640–644. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.10.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang J., Yang B., Wang H., Yang P., Du Y. Highly sensitive electrochemical determination of Sunset Yellow based on gold nanoparticles/graphene electrode. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2015;893:41–48. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2015.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deng K., Li C., Li X., Huang H. Simultaneous detection of sunset yellow and tartrazine using the nanohybrid of gold nanorods decorated graphene oxide. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2016;780:296–302. doi: 10.1016/j.jelechem.2016.09.040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu L., Shi M., Yue X., Qu L. A novel and sensitive hexadecyltrimethyl ammonium bromide functionalized graphene supported platinum nanoparticles composite modified glassy carbon electrode for determination of sunset yellow in soft drinks. Sensors Actuators B Chem. 2015;209:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2014.10.098. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qiu X., Lu L., Leng J., Yu Y., Wang W., Jiang M., Bai L. An enhanced electrochemical platform based on graphene oxide and multi-walled carbon nanotubes nanocomposite for sensitive determination of Sunset Yellow and Tartrazine. Food Chem. 2016;190:889–895. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.06.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dorraji P.S., Jalali F. Electrochemical fabrication of a novel ZnO/cysteic acid nanocomposite modified electrode and its application to simultaneous determination of sunset yellow and tartrazine. Food Chem. 2017;227:73–77. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.01.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li L., Zheng H., Guo L., Qu L., Yu L. Construction of novel electrochemical sensors based on bimetallic nanoparticle functionalized graphene for determination of sunset yellow in soft drink. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2019;833:393–400. doi: 10.1016/j.jelechem.2018.11.059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Magerusan L., Pogacean F., Coros M., Socaci C., Leostean S.P.C., Pana I.O. Green methodology for the preparation of chitosan/graphene nanomaterial through electrochemical exfoliation and its applicability in Sunset Yellow detection. Electrochim. Acta. 2018;283:578–589. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2018.06.203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Al-Qasmi N., Soomro M.T., Aslam M., Rehman A.U., Alid A.S., Danish E.Y., Ismail I.M.I., Hameed A. The efficacy of the ZnO: α-Fe2O3 composites modified carbon paste electrode for the sensitive electrochemical detection of loperamide: A detailed investigation. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2016;783:112–124. doi: 10.1016/j.jelechem.2016.11.036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.He Q., Liu J., Liu X., Li G., Chen D., Deng P., Liang J. Fabrication of amine-modified magnetite-electrochemically reduced graphene oxide nanocomposite modified glassy carbon electrode for sensitive dopamine determination. Nanomaterials. 2018;8:194. doi: 10.3390/nano8040194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mehdinia A., Khodaee N., Jabbari A. Fabrication of graphene/Fe3O4@polythiophene nanocomposite and its application in the magnetic solid-phase extraction of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons from environmental water samples. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2015;868:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2014.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.He Q., Liu J., Liu X., Li G., Deng P., Liang J. Preparation of Cu2O-reduced graphene nanocomposite modified electrodes towards ultrasensitive dopamine detection. Sensors. 2018;18:199. doi: 10.3390/s18010199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu F., Deng M., Li G., Chen S., Wang L. Electrochemical behavior of cuprous oxide–reduced graphene oxide nanocomposites and their application in nonenzymatic hydrogen peroxide sensing. Electrochim. Acta. 2013;88:59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2012.10.070. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elhag S., Ibupoto Z.H., Liu X., Nur O., Willander M. Dopamine wide range detection sensor based on modified Co3O4 nanowires electrode. Sensors Actuators B Chem. 2014;203:543–549. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2014.07.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.He Q., Liu J., Liu X., Li G., Deng P., Liang J., Chen D. Sensitive and selective detection of tartrazine based on TiO2-Electrochemically reduced graphene oxide composite-modified electrodes. Sensors. 2018;18:1911. doi: 10.3390/s18061911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carbone M., Nesticò A., Bellucci N., Micheli L., Palleschi G. Enhanced performances of sensors based on screen printed electrodes modified with nanosized NiO particles. Electrochim. Acta. 2017;246:580–587. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2017.06.074. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mahmoudian M.R., Alias Y., Basirun W.J., Woi P.M., Sookhakian M. Facile preparation of MnO2 nanotubes/reduced graphene oxidenanocomposite for electrochemical sensing of hydrogen peroxide. Sensors Actuators B Chem. 2014;201:526–534. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2014.05.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ye D., Li H., Liang G., Luo J., Zhang X., Zhang S., Chen H., Kong J. A three-dimensional hybrid of MnO2/graphene/carbon nanotubes based sensor for determination of hydrogen-peroxide in milk. Electrochim. Acta. 2013;109:195–200. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2013.06.119. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaabi N., Chouchene B., Mabrouk W., Matoussi F., Selmane E., Hmida B.H. Electrochemical properties of a modified electrode with δ-MnO2-based new nanocomposites. Solid State Ion. 2018;325:74–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ssi.2018.07.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.He Q., Liu J., Liang J., Liu X., Li W., Liu Z., Ding Z., Tuo D. Towards Improvements for Penetrating the Blood–Brain Barrier—Recent Progress from a Material and Pharmaceutical Perspective. Cells. 2018;7:24. doi: 10.3390/cells7040024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.He Q., Li G., Liu X., Liu J., Deng P., Chen D. Morphologically tunable MnO2 nanoparticles fabrication, modelling and their influences on electrochemical sensing performance toward dopamine. Catalysts. 2018;8:323. doi: 10.3390/catal8080323. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.He Q., Wu Y., Tian Y., Li G., Liu J., Deng P., Chen D. Facile electrochemical sensor for nanomolar rutin detection based on magnetite nanoparticles and reduced graphene oxide decorated electrode. Nanomaterials. 2019;9:115. doi: 10.3390/nano9010115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ranjusha R., Nair A.S., Ramakrishna S., Anjali P., Sujith K., Subramanian K.R.V., Sivakumar N., Kim T.N., Nair S.V., Balakrishnan A. Ultra fine MnO2 nanowire based high performance thin film rechargeable electrodes: Effect of surface morphology, electrolytes and concentrations. J. Mater. Chem. 2012;22:20465–20471. doi: 10.1039/c2jm35027k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jiang H., Li C.Z., Sun T., Ma J. A green and high energy density asymmetric supercapacitor based on ultrathin MnO2 nanostructures and functional mesoporous carbon nanotube electrodes. Nanoscale. 2012;4:807–812. doi: 10.1039/C1NR11542A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li J.F., Xi B.J., Zhu Y.C., Li Q.W., Yan Y., Qian Y.T. A precursor route to synthesize mesoporous γ–MnO2 microcrystals and their applications in lithium battery and water treatment. J. Alloys Compd. 2011;509:9542–9548. doi: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2011.07.064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen R.X., Yu J.G., Xiao W. Hierarchically porous MnO2 microspheres with enhanced adsorption performance. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2013;1:11682–11690. doi: 10.1039/c3ta12589k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang X., Li Y.D. Selected–control hydrothermal synthesis of α–and β–MnO2 single crystal nanowires. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:2880–2881. doi: 10.1021/ja0177105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang T., Sun D.D. Removal of arsenic from water using multifunctional micro–/nano–structured MnO2 spheres and microfiltration. Chem. Eng. J. 2013;225:271–279. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2013.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gan T., Shi Z., Deng Y., Sun J., Wang H. Morphology–dependent electrochemical sensing properties of manganese dioxide–graphene oxide hybrid for guaiacol and vanillin. Electrochim. Acta. 2014;147:157–166. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2014.09.116. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Geim A.K. Graphene: Status and prospects. Science. 2009;324:1530–1534. doi: 10.1126/science.1158877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Iski E.V., Yitamben E.N., Gao L., Guisinger N.P. Graphene at the atomic-scale: Synthesis, characterization, and modification. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2013;23:2554–2564. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201203421. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mei J., Zhang L., Niu Y. Fabrication of the magnetic manganese dioxide/graphene nanocomposite and its application in dye removal from the aqueous solution at room temperature. Mater. Res. Bull. 2015;70:82–86. doi: 10.1016/j.materresbull.2015.04.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee K., Ahmed M.S., Jeon S. Electrochemical deposition of silver on manganese dioxide coated reduced graphene oxide for enhanced oxygen reduction reaction. J. Power Sources. 2015;288:261–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2015.04.060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu Y., Yan D., Li Y., Wu Z., Zhuo R., Li S., Feng J., Wang J., Yan P., Geng Z. Manganese dioxide nanosheet arrays grown on graphene oxide as anadvanced electrode material for supercapacitors. Electrochim. Acta. 2014;117:528–533. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2013.11.121. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu F., Jin Y., Liao H., Cai L., Tong M., Hou Y. Facile self-assembly synthesis of titanate/Fe3O4 nanocomposites for the efficient removal of Pb2+ from aqueous systems. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2013;1:805–813. doi: 10.1039/C2TA00099G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kwon S.W., Byun M., Yoon D.H., Park J.-H., Kim W.-K., Lin Z., Yang W.S. Simple route to ridge optical waveguide fabricated viacontrolled evaporative self-assembly. J. Mater. Chem. 2011;21:5230–5233. doi: 10.1039/c0jm04514d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.He Q., Liu J., Liu X., Li G., Deng P., Liang J. Manganese dioxide Nanorods/electrochemically reduced graphene oxide nanocomposites modified electrodes for cost-effective and ultrasensitive detection of Amaranth. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 2018;172:565–572. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2018.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.He Q., Liu J., Liu X., Li G., Chen D., Deng P., Liang J. A promising sensing platform toward dopamine using MnO2 nanowires/electro-reduced graphene oxide composites. Electrochim. Acta. 2019;296:683–692. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2018.11.096. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xiong H., Jin B. The electrochemical behavior of AA and DA on graphene oxide modified electrodes containing various content of oxygen functional groups. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2011;661:77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jelechem.2011.06.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Laviron E. Adsorption, autoinhibition and autocatalysis in polarography and in linear potential sweep voltammetry. J. Electroanal. Chem. 1974;52:355–393. doi: 10.1016/S0022-0728(74)80448-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Anson F. Application of potentiostatic current integration to the study of the adsorption of cobalt (III)-(ethylenedinitrilo (tetraacetate)) on mercury electrodes. Anal. Chem. 1964;36:932–934. doi: 10.1021/ac60210a068. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Adams R. Electrochemistry at Solid Electrodes. Marcel Dekker Inc.; New York, NY, USA: 1969. [Google Scholar]