Abstract

Natural killer (NK) cell cytotoxicity is determined by a balance of positive and negative signals. Negative signals are transmitted by NK inhibitory receptors (killer immunoglobulin-like receptors, KIR) at the site of membrane apposition between an NK cell and a target cell, where inhibitory receptors become clustered with class I MHC ligands in an organized structure known as an inhibitory NK immune synapse. Immune synapse formation in NK cells is poorly understood. Because signaling by NK inhibitory receptors could be involved in this process, the human NK tumor line YTS was transfected with signal-competent and signal-incompetent KIR2DL1. The latter were generated by truncating the KIR2DL1 cytoplasmic tail or by introducing mutations in the immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibition motifs. The KIR2DL1 mutants retained their ability to cluster class I MHC ligands on NK cell interaction with appropriate target cells. Therefore, receptor–ligand clustering at the inhibitory NK immune synapse occurs independently of KIR2DL1 signal transduction. However, parallel examination of NK cell membrane lipid rafts revealed that KIR2DL1 signaling is critical for blocking lipid raft polarization and NK cell cytotoxicity. Moreover, raft polarization was inhibited by reagents that disrupt microtubules and actin filaments, whereas synapse formation was not. Thus, NK lipid raft polarization and inhibitory NK immune synapse formation occur by fundamentally distinct mechanisms.

Signaling between immune effector cells and target cells is fundamental to cellular immune responses. This process involves the apposition of effector and target cell membranes to form an “immunological synapse,” a structure first described for the interaction between T cells and antigen-presenting cells (1–3). At the synapse, adhesion molecules, MHC proteins, and T cell receptors (TCR) become concentrated in an organized geometry. In a mature immunological synapse, a central supramolecular activation cluster of oligomerized TCR/CD3 bound to class II MHC antigens is surrounded by a peripheral supramolecular activation cluster of bound adhesion molecules intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) and lymphocyte function-associated antigen-1 (LFA-1) (2, 4). The use of artificial antigen-presenting cells (lipid bilayers) revealed that this organization results from a dynamic process; ICAM-1 and LFA-1 initially cluster inside the TCR/class II ring, which later inverts to form the central supramolecular activation cluster of the mature synapse (4). Using video microscopy, the rapid accumulation of ICAM-1 at the interface of a T cell and its target antigen-presenting cell was correlated with the elevation of cytoplasmic calcium that is characteristic of T cell activation. Thus, the formation of an immunological synapse was productively linked to T cell activation.

Lipid rafts have been implicated in the organization of the T cell immunological synapse (5, 6). Rafts are sphingolipid- and cholesterol-rich membrane subdomains that are hypothesized to function in signal transduction (7, 8). Rafts may mediate signal transduction by serving as scaffolds to sequester signaling complexes in an otherwise fluid membrane. Many of the cytoplasmic proteins involved in T cell activation have been shown to be either raft-resident proteins or selectively recruited to rafts during T cell activation (6). The TCR itself is recruited to rafts after initial engagement with a class II MHC ligand (5). Disruption of lipid rafts by cholesterol depletion with methyl-β-cyclodextrin interferes with TCR signal transduction (5, 6). Evidence of a role for the actin cytoskeleton in redistribution of raft-resident proteins in a variety of immune cell systems suggests a link between the cytoskeleton and T cell immunological synapse formation (9, 10). Indeed, T cell activation and T cell immunological synapse formation both depend on the activity of cytoskeletal and motor proteins including actin, actin-associated protein, and myosin motor proteins (3, 11, 12).

Immune synapse formation in natural killer (NK) cells was recently described (13, 14). NK cells comprise 5–10% of peripheral blood lymphocytes and provide an essential first line of defense in the innate immune response against tumorigenic and virally infected cells. NK cells are able to kill in the absence of prior antigen exposure. They recognize and kill cells that express virus-encoded proteins as well as tumorigenic or virally infected cells that have down-regulated expression of class I MHC protein to evade T cell recognition (15, 16). Healthy cells expressing normal levels of class I MHC protein are able to resist NK cell attack by using their class I MHC molecules as ligands to engage a range of inhibitory receptors on the NK cell surface (reviewed in ref. 17). Receptor–ligand binding between class I MHC protein and an NK inhibitory receptor leads to the initiation of a dominant inhibitory signaling cascade that blocks NK cytotoxicity. One such receptor–ligand pair in humans involves class I MHC proteins of the HLA-Cw4 allele family and the NK inhibitory receptor KIR2DL1 (18, 19).

KIR2DL1 signal transduction depends on two immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibition motifs (ITIM) in its cytoplasmic tail (reviewed in ref. 17). Upon KIR2DL1 binding to HLA-Cw4 on the surface of a target cell, the KIR2DL1 ITIMs are tyrosine-phosphorylated. ITIM phosphotyrosines are then recognized and bound by the SH2 domains of the cytoplasmic tyrosine phosphatases SHP-1 and SHP-2. Mutagenesis studies showed that the two KIR2DL1 ITIMs have different roles in inhibiting NK cell killing. The membrane-proximal ITIM (amino acids 377–380) recruits SHP-1 and is itself sufficient to inhibit NK cell killing. The membrane-distal ITIM (amino acids 407–410) cannot recruit either phosphatase alone but acts in concert with the membrane-proximal ITIM to recruit SHP-2, which then amplifies the signal from SHP-1 (20). SHP-1 and SHP-2 binding leads to the propagation of a downstream signaling cascade that inhibits NK cytotoxicity, sparing the HLA-Cw4-expressing target cell (17).

Similar to the T cell immunological synapse, the inhibitory NK immune synapse is characterized by the supramolecular organization of clustered receptor–ligand pairs at the interface of an effector NK cell and its target cell (13). NK immune synapses were first observed with primary NK cells cultured from human peripheral blood lymphocytes or the NK tumor line YTS transfected with KIR2DL1 (YTS/KIR2DL1). Receptor–ligand clustering indicative of the immune synapse was observed at the site of membrane contact as an aggregation of HLA-Cw4-green fluorescence protein (GFP) in transfected target cells or on the NK side of the synapse by staining with anti-KIR2DL1 mAb EB6. Synapse formation depended upon extracellular Zn2+ (13). Zinc ions bind to an extracellular zinc-binding motif on KIR2DL1 and are required for signal transduction (22). Cell-free Zn2+-dependent multimerization of KIR was demonstrated by several techniques and significantly slows KIR/HLA-C binding kinetics (21). The structure of KIR2DL2 in complex with its class I MHC ligand, HLA-Cw3, also suggests oligomerization (23).

Despite the fundamental geometric similarity of receptor clustering in the T cell and NK immune synapses, several features differ. The organization of receptor–ligand pairs in the inhibitory NK immune synapse is inverted relative to the T cell immunological synapse. In the inhibitory NK immune synapse, a ring of clustered class I MHC bound to KIR surrounds a central cluster of lymphocyte function-associated antigen-1 and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (13). Moreover, class I oligomerization at the NK immune synapse is not perturbed by the addition of cytoskeletal inhibitors or ATP-depletion drugs that have been shown to prevent formation of the T cell immunological synapse (3, 12, 13). Interestingly, the pattern of raft polarization in NK cells that form the inhibitory synapse was recently shown to be opposite that reported for activated T cell synapses. In NK cells, lipid rafts polarized to the site of cell contact in conjugates with sensitive, class I-negative target cells but not in conjugates with resistant, class I-positive target cells (24).

Because the inhibitory NK immune synapse does not precisely parallel the T cell immunological synapse, the possibility emerged that NK immune synapses form by a novel signal transduction mechanism. Thus, we sought to characterize a role for signaling in inhibitory NK immune synapse formation. To directly assess the role of KIR2DL1 signal transduction in the formation of the inhibitory NK immune synapse, a series of stable YTS transfectants expressing signal-deficient KIR2DL1 mutants was generated. Conjugates of 721.221/HLA-C transfectants and these YTS/KIR2DL1 mutant transfectants were then analyzed by laser-scanning confocal microscopy to determine a possible role for KIR2DL1 signal transduction in receptor clustering, cytoskeletal movement, and lipid raft redistribution at the inhibitory NK immune synapse.

Materials and Methods

Generation of KIR2DL1 Mutants.

cDNA encoding a full-length sequence of KIR2DL1 was previously cloned into the modified retroviral vector pBABE (25). This pBABE retrovirus containing KIR2DL1 was used as a PCR template for cloning KIR2DL1 mutants by using conditions described for QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis (Stratagene).

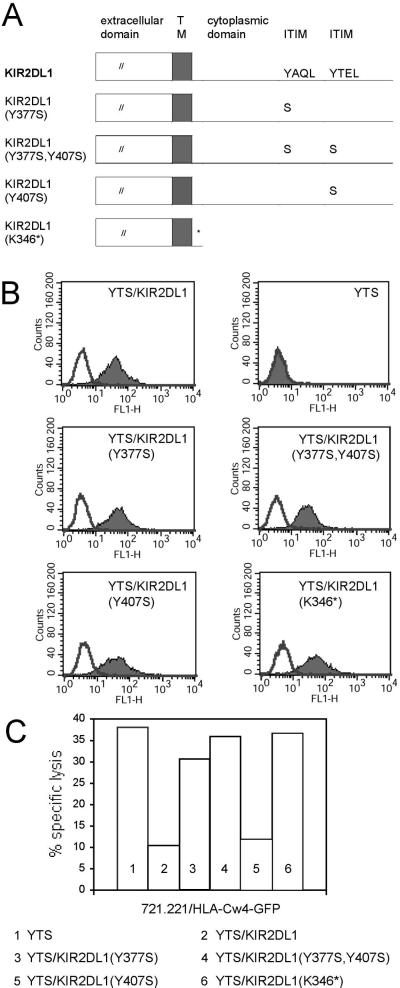

To directly assess the role of signal transduction involving the two KIR2DL1 ITIMs, located at amino acids 377–380 (membrane-proximal ITIM) and 407–410 (membrane-distal ITIM), ITIM tyrosines were mutated by site-directed mutagenesis. The product of the membrane-proximal ITIM PCR is KIR2DL1(Y377S) (primers with mutant codon underlined in the sense primer: 5′-GAGGTGACATCCACACAGTTG-3′ and 3′-AAGTTGCGTGGACACGATGATATC-5′), and the membrane-distal ITIM PCR produced KIR2DL1(Y407S) (primers 5′-GATATCATCGTGTCCACGGAACTT-3′ and 3′-AAGTTCCGTGGGACACGATGAATATC-5′). KIR2DL1(Y377S) DNA was then mutated in a second round of site-directed mutagenesis by using the Y407S primer set to create a KIR2DL1 with both ITIM tyrosine residues mutated, KIR2DL1(Y377S,Y407S). Finally, the entire KIR2DL1 cytoplasmic domain was truncated to create mutant KIR2DL1(K346*) (PCR primers with stop codon underlined in the sense primer: 5′-TCCAACAAATAAAATGCTGCG-3′ and 3′-CGCAGCATTTTATTTGTTGGA-5′). Mutant KIR2DL1 sequences are depicted in Fig. 1A.

Figure 1.

Generation of YTS cell lines transfected with KIR2DL1 mutants. (A) KIR2DL1 cDNA in pBABE was mutated by site-directed mutagenesis. The wild-type KIR2DL1 sequence (Top) includes ITIM motifs. KIR2DL1(Y377S) contains a tyrosine-to-serine substitution in the membrane-proximal ITIM, KIR2DL1(Y407S) has a tyrosine-to-serine substitution in the membrane-distal ITIM, and KIR2DL1(Y377S,Y407S) contains tyrosine-to-serine substitutions in both membrane-proximal and membrane-distal ITIMs. KIR2DL1(K346*) has a stop codon at the start of the cytoplasmic tail. (B) Relative levels of KIR2DL1 protein expression in YTS cells after retroviral transfection and sorting for positive KIR2DL1 expression. FACS analysis using the anti-KIR2DL1 antibody HP-3E4 is denoted by the solid histogram, where the open histogram indicates staining with an IgM isotype control. (C) Specific lysis of 721.221/HLA-Cw4-GFP target cells by YTS and its wild type and mutant KIR2DL1 transfectants was assayed by 35S release. Spontaneous release did not exceed 15%. The absence of tyrosine 377 in KIR2DL1 mutants corresponds with the loss of KIR2DL1-mediated inhibition of cytotoxicity.

All primers were purchased from Operon Technologies (Alameda, CA), and all plasmid inserts were sequenced by the Children's Hospital Nucleic Acid and Protein Core Facility (Philadelphia).

Cell Lines and Transfectants.

YTS transfectants.

The YTS-Eco cell line, an NK tumor cell line expressing the murine ecotropic receptor but no known KIR, was previously described (25). Mutant KIR2DL1 was transfected into murine retrovirus packaging cell lines, either Bosc 293-Eco (25) or Plat-E 293-Eco (26). Packaged retroviruses containing the mutant KIR2DL1 cDNA were used to infect YTS-Eco as described (25). Transfectants were selected for puromycin resistance (2.0 μg/ml) in RPMI supplemented with 10% FCS.

KIR2DL1 expression on YTS transfectants was verified by FACS analysis. Cells were stained with primary mAb HP-3E4, anti-KIR2DL1 (ref. 27; gift of M. Lopez-Botet, Hospital Universitario de la Princesa, Madrid), followed by an FITC-conjugated goat-anti-mouse secondary Ab (ICN) and analyzed on a Becton Dickinson FACSCalibur. Positive transfectants were sorted at the Dana–Farber Cancer Institute Core Facility (Boston).

YTS/KIR2DL1 mutant transfectants were assayed for cytotoxicity by 5 h 35S release assay as described (28).

721.221 transfectants.

HLA-Cw3-GFP and HLA-Cw4-GFP transfectants of the MHC-deficient B-lymphoblastoid cell line 721.221 have been described (13).

Slide Preparation and Microscopy.

Slides were prepared following a protocol adapted from Eisenbraun et al. (29). Effector cells (YTS/KIR2DL1 or YTS/KIR2DL1 mutant transfectants) were suspended in 1 ml of complete RPMI to a final concentration of 5 × 106 cells/ml. Target cells (721.221/HLA-Cw3-GFP or 721.221/HLA-Cw4-GFP) were diluted in complete RPMI to a concentration of 2.5 × 106 cells/ml. Twenty-five microliters each of the desired effector cell and target cell combination (50 μl total volume) were mixed in a tissue culture tube to achieve a 2:1 cell ratio and coincubated at 37°C for 15 min. The conjugated cells were then gently resuspended, and 25 μl was spread onto a prewarmed poly(l-lysine)-coated slide (Sigma). Slides were incubated for another 15 min at 37°C to promote cell attachment. After this incubation, slides were sealed with a 0.17-mm coverslip (VWR Scientific). Single- and two-color confocal analyses were performed on a Zeiss LSM 510 equipped with an argon (488 nm) and a helium neon (543 nm) laser. Image collection was performed with Zeiss 510-associated software.

Calculating Percentage Clustering.

To maintain objectivity in all percentage-clustering observations, slides were scanned first by Nomarski imaging, and cells that were clearly conjugated were then examined for their fluorescence distribution. Randomly selected NK cell–B cell conjugates were selected for confocal imaging only if they formed tight cell–cell contacts under Nomarski light microscopy conditions. Acceptable conjugates were scored as either positive or negative for accumulation of fluorophore-conjugated protein at the cell–cell interface. A minimum of 40 cell conjugates were scored per slide. Percentage clustering indicates results from three or more experiments.

Cholera Toxin Staining.

Transfectants (1.25 × 106 YTS/KIR2DL1) were incubated for 1 h on ice with Alexa 594-conjugated cholera toxin β subunit (CTX β) diluted to 40 μg/ml in PBS according to the manufacturer's instructions (Molecular Probes). CTX β-labeled YTS/KIR2DL1 transfectants were washed twice in PBS, counted, and resuspended to a concentration of 5 × 106 cells/ml; 25 μl was then mixed with target cells and prepared for microscopy as described above.

Treatment with Cytoskeletal Inhibitors.

Transfectants (1.25 × 106 YTS/KIR2DL1) were incubated for 1 h at room temperature in RPMI containing 10 μM cytochalasin D or colchicine (Sigma). Treated cells were centrifuged and resuspended in an appropriate volume of media containing the cytoskeletal inhibitors such that NK cells were at a density of 5 × 106/ml. Cells were then labeled with Alexa-594-conjugated CTX β and prepared for microscopy with 721.221/HLA-Cw4-GFP targets.

Results

Mutations to the Cytoplasmic Domain of KIR2DL1 Do Not Affect Receptor–Ligand Clustering at the Inhibitory NK Immune Synapse.

The possibility that inhibitory signals generated by KIR2DL1 after ligand binding were responsible for the receptor–ligand clustering observed at NK immune synapses was examined by constructing retroviral expression vectors encoding mutant KIR2DL1. Because KIR2DL1 ITIM phosphotyrosines 377 and 407 have different roles in mediating inhibitory signal transduction, KIR2DL1 mutants with both single and double tyrosine-to-serine substitutions, KIR2DL1(Y377S), KIR2DL1(Y407S), and KIR2DL1(Y377S,Y407S), were generated (Fig. 1A). Serines were chosen because they conserve amino acid polarity while eliminating phosphorylation by tyrosine kinases. Finally, a stop codon was inserted near the start of the KIR2DL1 cytoplasmic domain at lysine 346. The resulting KIR2DL1(K346*) truncation mutant lacks both the membrane-proximal and membrane-distal ITIM motifs required for KIR2DL1 signal transduction (Fig. 1A).

Using a retroviral infection system, KIR2DL1 mutant genes were transfected into YTS, an NK tumor cell line that expresses no known KIR. After antibiotic selection and sorting of YTS/KIR2DL1-positive cell populations, stable transfectants were generated for each of the KIR2DL1 mutants. Each of the YTS transfectants expressed KIR2DL1 mutant protein at levels similar to the YTS/KIR2DL1 wild-type transfectant (Fig. 1B).

In a cytotoxicity assay with 721.221/HLA-Cw4-GFP cells as targets, effector cells YTS/KIR2DL1(Y3775), YTS/KIR2DL1(Y3775,Y4075), or YTS/KIR2DL1(K346*), termed signal incompetent mutants, were unable to inhibit NK cytotoxicity as reported (20). YTS/KIR2DL1(Y4075) remained inhibitory signal competent (Fig. 1C).

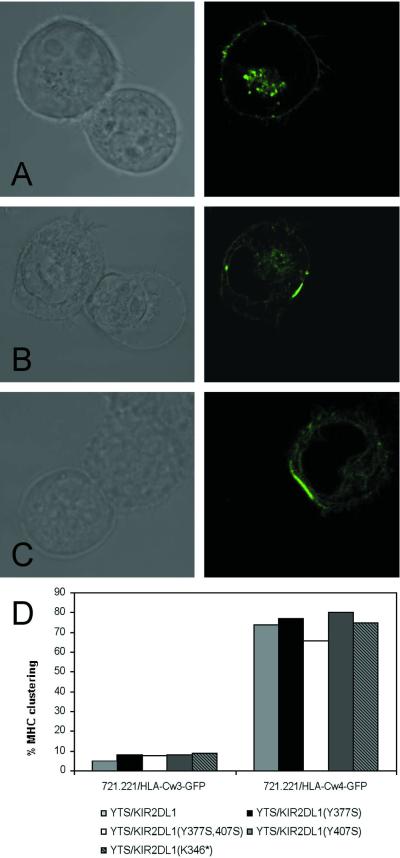

Confocal microscopy of YTS/KIR2DL1 conjugates formed with 721.221 target cells transfected with HLA-C alleles demonstrated receptor–ligand clustering in 71% of conjugates with HLA-Cw4-GFP but only 5% of conjugates with HLA-Cw3-GFP (13; Fig. 2 A and B). Using YTS/KIR2DL1 mutants YTS/KIR2DL1(Y377S), YTS/KIR2DL1(Y377S,Y407S), YTS/KIR2DL1(Y407S), and YTS/KIR2DL1(K352*) as effector cells, HLA-Cw4-GFP was again clustered in a synapse in roughly 75% of conjugates (Fig. 2 C and D; data not shown). Thus, HLA-Cw4-GFP clustering mediated by its interaction with KIR2DL1 did not depend on signal transduction through the cytoplasmic domain of KIR2DL1.

Figure 2.

Both wild-type and signal-incompetent YTS/KIR2DL1 transfectants induce clustering of HLA-Cw4. For each effector/target cell conjugate, Nomarski imaging is shown to the left of corresponding HLA-C-GFP fluorescence as detected by laser-scanning confocal microscopy (original magnification ×160). (A) YTS/KIR2DL1 + 721.221/HLA-Cw3-GFP is representative of conjugates scored as negative for ligand clustering. (B) YTS/KIR2DL1 + 721.221/HLA-Cw4-GFP demonstrates positive HLA-Cw4 clustering. (C) YTS/KIR2DL1(Y377S,Y407S) + 721.221/HLA-Cw4-GFP illustrates positive clustering as scored for all YTS/KIR2DL1 mutant transfectants. (D) Percentage clustering of HLA-Cw3-GFP (Left) or HLA-Cw4-GFP (Right) in cell–cell conjugates of YTS/KIR2DL1 transfectants. For each effector/target cell pair, >50 conjugates were scored.

Signal-Competent and Signal-Incompetent Inhibitory NK Immune Synapses Demonstrate Differential Lipid Raft Polarization.

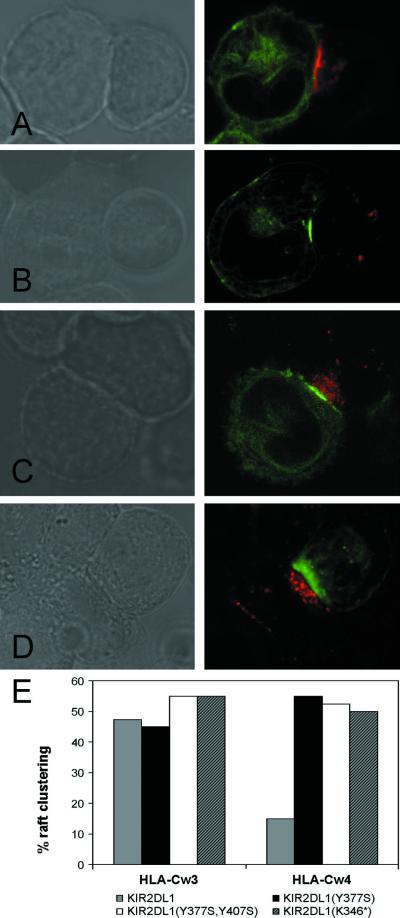

Lipid rafts in the NK cell membrane migrate to the interface of NK cells and sensitive targets, but not to the interface of NK cells and resistant targets (24). Rafts may be detected by specific cholera toxin staining of cells for GM1, a marker of lipid rafts. Confocal microscopy of YTS/KIR2DL1 and 721.221/HLA-Cw4-GFP or 721.221/HLA-Cw3-GFP after staining with Alexa-594-labeled cholera toxin revealed a raft polarization pattern similar to that previously reported (24). Rafts polarized toward the contact site of YTS/KIR2DL1 and 721.221/HLA-Cw3-GFP cell conjugates, as demonstrated by raft polarization in 47.5% of conjugates imaged in the absence of HLA-Cw3-GFP clustering at the membrane contact (Fig. 3 A and E). However, similar raft polarization was observed in only 15% of YTS/KIR2DL1 and 721.221/HLA-Cw4-GFP conjugates in which inhibitory synapses formed, as is apparent by the absence of raft staining near the clustered HLA-Cw4-GFP (Fig. 3B). Thus, lipid raft polarization toward the apposed membranes of conjugated cells negatively correlated with the existence of inhibitory signal-competent immune synapses, i.e., rafts are excluded from signal-competent inhibitory synapses.

Figure 3.

Lipid raft polarization in YTS/KIR2DL1 transfectants is regulated by KIR2DL1 signal transduction. Effector cells were stained with Alexa 594-conjugated CTX β before coincubation with target cells and subsequent confocal microscopy (original magnification ×160). For each effector/target cell pair, Nomarski imaging (Left) and CTX β and GFP fluorescence (Right) are shown. NK cell lipid rafts are visible as Alexa 594-conjugated CTX β staining (red), and target cells express HLA-Cw3-GFP or HLA-Cw4-GFP (green). (A) YTS/KIR2DL1 + 721.221/HLA-Cw3-GFP is representative of conjugates scored as positive for raft polarization in a cell with a signal-competent synapse. (B) YTS/KIR2DL1 + 721.221/HLA-Cw4-GFP fails to demonstrate raft polarization. (C) YTS/KIR2DL1(Y377S,Y407S) + 721.221/HLA-Cw4-GFP exemplifies raft polarization using signal-incompetent YTS/KIR2DL1 mutant transfectants. (D) YTS/KIR2DL1(K346*) + 721.221/HLA-Cw4-GFP. (E) Percentage raft clustering in cell–cell conjugates of HLA-Cw3-GFP (Left) or HLA-Cw4-GFP (Right) and YTS/KIR2DL1 transfectants as indicated. For each effector/target cell pair, 40 conjugates were scored.

To investigate whether KIR2DL1 signal transduction was responsible for the differential raft distribution observed between 721.221/HLA-Cw3-GFP and 721.221/HLA-Cw4-GFP, KIR2DL1 mutants YTS/KIR2DL1(Y377S), YTS/KIR2DL1(Y377S,Y407S), and YTS/KIR2DL1(K346*) were also examined for raft distribution. Unexpectedly, polarized lipid rafts were observed at the synaptic interface in roughly 50% of conjugates between the YTS/KIR2DL1 mutants and 721.221/HLA-Cw4 (Fig. 3 C–E). Because lipid raft polarization was observed in YTS/KIR2DL1(Y377S) and YTS/KIR2DL1(Y377S,Y407S), signaling mediated by KIR2DL1 ITIMs appears to be required to exclude rafts from the inhibitory synaptic region. Raft polarization in the absence of negative signaling was also shown by 721.221/HLA-Cw3-GFP conjugates formed with all YTS/KIR2DL1 mutants (Fig. 3E).

Cytoskeletal Inhibitors Reverse Raft Polarization at Synapses Between YTS/KIR2DL1 Mutants and 721.221/HLA-Cw4-GFP.

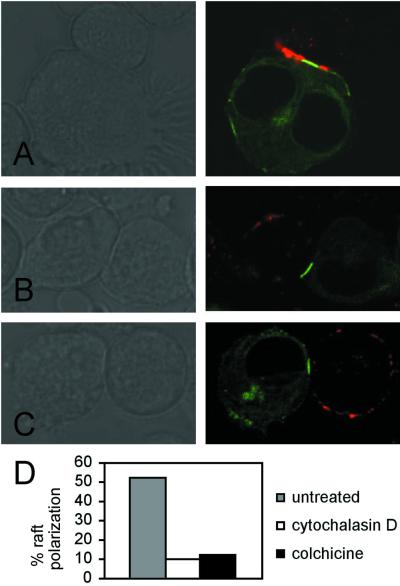

Previously, clustering of HLA-Cw4 in the inhibitory NK immune synapse was observed to be independent of the actin and tubulin cytoskeleton, as preincubation of YTS/KIR2DL1 effector cells with cytochalasin B or D (drugs that prevent actin polymerization) or colchicine (prevents microtubule polymerization) had no effect on inhibitory immune synapse formation (13). However, lipid raft polarization during T cell activation has been shown to depend on cytoskeletal mobilization (9, 10). Similarly, pretreating YTS transfectants with either cytochalasin D or colchicine prevented raft polarization in synapsing conjugates of YTS/KIR2DL1(Y377S,Y407S) and 721.221/HLA-Cw4-GFP (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Cytoskeletal inhibitors reverse raft aggregation at signal-incompetent NK immune synapses. For each effector/target cell pair, Nomarski imaging is shown to the left of fluorescence (original magnification ×160). NK cell lipid rafts are visible as Alexa 568-conjugated CTX β staining (red), and target cells express HLA-Cw4-GFP (green). (A) YTS/KIR2DL1(Y377S,Y407S) and 721.221/HLA-Cw4-GFP, no drug treatment. (B) YTS/KIR2DL1(Y377S,Y407S) cells pretreated with 10 μM cytochalasin D before co-incubation with 721.221/HLA-Cw4-GFP targets. Note that ligand clustering remains unperturbed, whereas rafts, which were polarized in the untreated sample, are dispersed. (C) YTS/KIR2DL1(Y377S,Y407S) cells pretreated with 10 μM colchicine before coincubation with 721.221/HLA-Cw4-GFP targets again display ligand clustering but no raft polarization.

Discussion

NK cell killing is regulated by the integration of signals initiated by ligand binding to an array of activating and inhibitory NK cell surface receptors (reviewed in ref. 30). The NK inhibitory receptor KIR2DL1 is known to cluster at its membrane contact with 721.221 B lymphoblastoid target cells expressing the KIR2DL1 ligand HLA-Cw4 (13). This KIR2DL1-HLA-Cw4 clustering occurs at regions of membrane apposition between effector cells and target cells and constitutes the inhibitory NK immune synapse.

Little is known about events leading to the formation of the inhibitory NK immune synapse. One model holds that initial stochastic binding events between KIR2DL1 and HLA-Cw4 lead to the Zn2+-dependent recruitment of further receptor–ligand pairs to constitute the full inhibitory NK immune synapse. The present data demonstrate that any such recruitment cannot depend on ITIM-mediated KIR2DL1 signal transduction. Confocal imaging experiments using signal-incompetent YTS/KIR2DL1 transfectants revealed that KIR2DL1 signaling is not required for co-clustering of HLA-Cw4 and KIR2DL1 and formation of the inhibitory NK immune synapse. Because ITIM phosphorylation requires ATP hydrolysis, this result accords with the observation that KIR2DL1-class I clustering is ATP-independent (13).

Lipid rafts polarize to the contact site of NK cells and sensitive target cells but are excluded from the contact site of NK cells and resistant targets. The effect of negative signals on lipid raft polarization was initially determined by antibody blocking of KIR3DL/HLA-B58 binding and by overexpression of a dominant negative SHP-1 (24). Results reported here extend these findings and suggest that KIR2DL1 signaling at the inhibitory NK immune synapse inhibits lipid raft polarization in NK cells. Blocking raft polarization depends on KIR2DL1 ITIM tyrosines. Because NK killing correlates with raft polarization, KIR2DL1 ITIM-mediated modulation of raft polarization provides a mechanism for NK inhibition.

NK cell activation and inhibition are known to be local rather than global effects, as NK cells in contact with two target cells have been shown to be inhibited by one resistant target while simultaneously activated to kill the other, susceptible target (31). Signal-mediated exclusion of lipid rafts from an inhibitory NK immune synapse is consistent with this local signaling mechanism and may allow raft polarization and thus NK activation at another contact site. Co-localization of lipid rafts and HLA-Cw4 at signal-incompetent inhibitory immune synapses suggests that lipid rafts may in fact localize NK-activating receptors to the site of membrane contact in the absence of productive KIR2DL1 signaling. However, it is unclear how lipid raft polarization is linked to NK activation and cytotoxicity. Rafts are known to carry many activating signal transduction molecules in other immune cell systems (5, 8, 9); the spatial organization of these molecules at the NK synapse has also been recently observed (32). Whether lipid rafts transport NK-activating receptors to the immune synapse remains to be determined.

Finally, the relationship established between raft polarization and KIR2DL1 signaling through the NK immune synapse illuminates similarities and differences between NK and T cell synapses. In both NK cells and T cells, raft polarization is cytoskeleton-dependent and thus inhibited by reagents such as cytochalasin and colchicine that disrupt organized actin and tubulin structures (Fig. 4; refs. 9 and 33). However, in T cells, actin- and tubulin-mediated cytoskeletal movement is also required to form the TCR clusters that characterize activating T cell immunological synapses (3, 12). In contrast, in NK cells, clustered signal-competent KIR2DL1 actively excluded rafts from the immune synapse. Further, biochemical isolation of raft fractions from NK cells failed to reveal the presence of KIR or SHP-1 in rafts (unpublished data cited in ref. 24).

Taken together, our results suggest that a complex series of interactions are involved in inhibitory NK immune synapse formation. In this model, class I MHC binding to KIR2DL1 initiates Zn2+-dependent receptor oligomerization, which generates ITIM-dependent signals at the NK immune synapse. These ITIM-dependent signals actively prevent the raft polarization and NK activation that otherwise occurs during conjugation of NK cells and target cells. Further analysis will be necessary to precisely determine the molecular interactions that mediate relationships between NK cell immune synapses, signal transduction, raft polarization, and cytoskeletal movement.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jonathan Boyson, Isaac Chiu, Jordan Orange, Ilaria Potolicchio, and Louise Koopman for insightful discussions and Dave Smith for technical assistance. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant CA-47554 (to J.L.S.) and a grant from the Harvard College Research Program (to M.S.F.).

Abbreviations

- NK

natural killer

- KIR

killer immunoglobulin-like receptor

- ITIM

immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibition motif

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- CTX β

cholera toxin β subunit

- TCR

T cell receptor

References

- 1.Wülfing C, Davis M M. Science. 1998;282:2266–2269. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5397.2266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Monks C R, Freiberg B A, Kupfer H, Sciaky N, Kupfer A. Nature (London) 1998;395:82–86. doi: 10.1038/25764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wülfing C, Sjaastad M D, Davis M M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:6302–6307. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grakoui A, Bromley S K, Sumen C, Davis M M, Shaw A S, Allen P M, Dustin M L. Science. 1999;285:221–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Montixi C, Langlet C, Bernard A-M, Thimonier J, Dubois C, Wurbel M-A, Chauvin J-P, Pierres M, He H-T. EMBO J. 1998;17:5334–5348. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.18.5334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xavier R, Brennan T, Li Q, McCormack C, Seed B. Immunity. 1998;8:723–732. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80577-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown D A, London E. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1998;14:111–136. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.14.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simons K, Ikonen E. Nature (London) 1997;387:569–572. doi: 10.1038/42408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harder T, Simons K. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:556–562. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199902)29:02<556::AID-IMMU556>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Howolka D, Sheets E D, Baird B. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:1009–1019. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.6.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Valitutti S, Dessing M, Aktories K, Gallati H, Lanzavecchia A. J Exp Med. 1995;181:577–584. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.2.577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dustin M L, Cooper J A. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:23–29. doi: 10.1038/76877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davis D M, Chiu I, Fassett M, Cohen G B, Mandelboim O, Strominger J L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:15062–15067. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.15062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eriksson M, Ryan J C, Nakamura M C, Sentman C L. Immunology. 1999;97:341–347. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1999.00800.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mandelboim O, Lieberman N, Lev M, Paul L, Arnon T I, Bushkin Y, Davis D M, Strominger J L, Yewdell J W, Porgador A. Nature (London) 2001;409:1055–1060. doi: 10.1038/35059110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ljunggren H-G, Karre K. Immunol Today. 1990;11:237–244. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(90)90097-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Long E O. Annu Rev Immunol. 1999;17:875–904. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Colonna M, Borsellino G, Falco M, Ferrara G B, Strominger J L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:12000–12004. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.24.12000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Colonna M, Samaridis J. Science. 1995;268:405–408. doi: 10.1126/science.7716543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bruhns P, Marchetti P, Fridman W H, Vivier E, Daeron M. J Immunol. 1999;162:3168–3175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Valez-Gomez M, Erskine R A, Deacon M P, Strominger J L, Reyburn H T. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:1734–1739. doi: 10.1073/pnas.041618298. . (First Published February 6, 2001; 10.1073/pnas.0416182980) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rajagopalan S, Long E O. J Immunol. 1998;161:1299–1305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boyington J C, Motyka S A, Schuck P, Brooks A G, Sun P D. Nature (London) 2000;405:537–543. doi: 10.1038/35014520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lou Z, Jeremovic D, Billadeau D D, Leibson P J. J Exp Med. 2000;191:347–354. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.2.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cohen G B, Gandhi R T, Davis D M, Mandelboim O, Chen B K, Strominger J L, Baltimore D. Immunity. 1999;10:661–671. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80065-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morita S, Kojima T, Kitamura T. Gene Ther. 2000;7:1063–1066. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perez-Villar J J, Melero I, Navarro F, Carretero M, Bellon T, Llano M, Colonna M, Geraghty D E, Lopez-Botet M. J Immunol. 1997;158:5736–5743. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mandelboim O, Wilson S B, Valez-Gomez M, Reyburn H T, Strominger J L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:4604–4609. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eisenbraun M D, Tamir A, Miller R A. J Immunol. 2000;164:6105–6112. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.12.6105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moretta A, Biassoni R, Bottino C, Moretta L. Semin Immunol. 2000;12:129–138. doi: 10.1006/smim.2000.0215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eriksson M, Leitz G, Fallman E, Axner O, Ryan J C, Nakamura M C, Sentman C L. J Exp Med. 1999;190:1005–1012. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.7.1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vyas Y M, Mehta K M, Morgan M, Maniar H, Butros L, Jung S, Burkhardt J K, Dupont B. J Immunol. 2001;167:4358–4367. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.8.4358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sancho D, Nieto M, Llano M, Rodriguez-Fernandez J L, Tejedor R, Avraham S, Cabanas C, Lopez-Botet M, Sanchez-Madrid R. J Cell Biol. 2000;149:1249–1262. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.6.1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]