Abstract

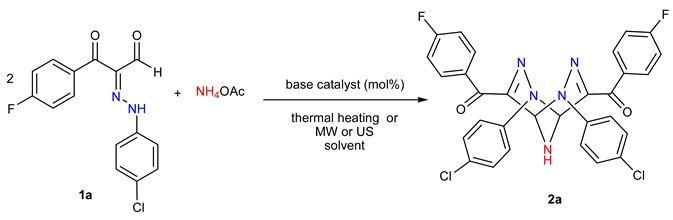

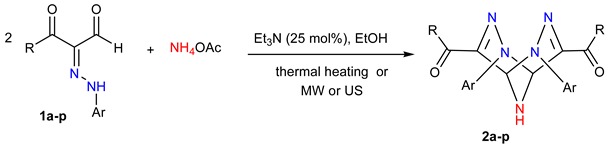

Reactions of a series of 3-oxo-2-arylhydrazonopropanal derivatives with two molar ratio of ammonium acetate afforded a library of tetrasubstituted 2,3,6,7,9-pentaazabicyclo[3.3.1]nona- 3,7-diene derivatives in good to excellent isolated yields. The reaction was activated with triethylamine catalyst under three different heating modes: thermal, ultrasonic and microwave irradiating conditions in ethanol solvent. The structures of the isolated products were fully characterized by spectral and analytical data as well as X-ray single crystal of selected examples.

Keywords: Bicyclo[3.3.1]nonadienes, 3-oxo-2-arylhydrazono-propanals, catalysis, ultrasound, microwave

1. Introduction

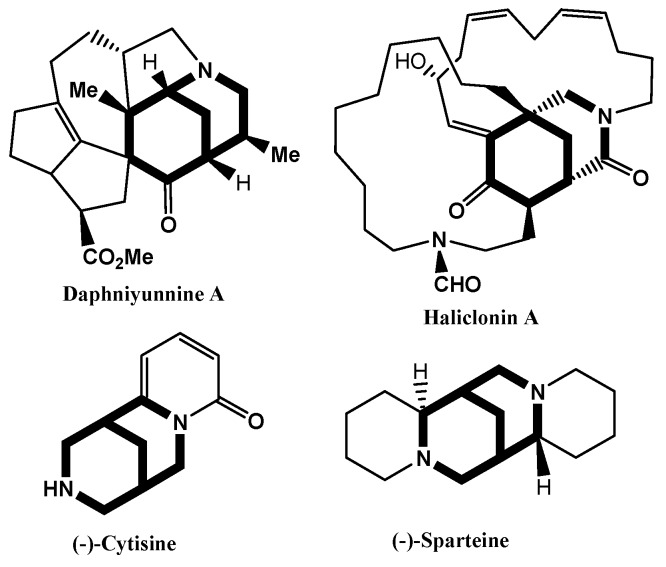

The azabicyclo[3.3.1]nonane moiety is a privileged scaffold embedded in the structures of numerous bioactive natural products (Figure 1) [1,2]. The azabicyclo[3.3.1]nonane derivatives are reported to have diverse biological applications. For example, 1-azabicyclo[3.3.1]nonanes are useful for the treatment of psychotic and neurodegenerative disorders [3,4]. The 2-azabicyclo[3.3.1]nonane skeleton is present in several important narcotic analgesics and marine alkaloids [5,6,7]. 3-Azabicylo[3.3.1]nonane is the core substructure of the marine natural product; Haliclonin A (Figure 1) [8,9]. 9-Azabicyclo[3.3.1]nonane derivatives possess cytotoxic [10], dopamine D3 receptor ligands [11], high sigma-2 receptor affinities [12], and are used for the treatment of diabetes mellitus [13]. Furthermore, 1,4-diazabicyclo[3.3.1]nonane derivatives are reported to exhibit high in vivo affinity and selectivity for the dopamine transporter (DAT) blockers [14,15]. 3,7-Diazabicyclo[3.3.1]nonanes are reported to be useful in the treatment of cardiac arrhythmias [16], and exhibited anti-platelet, antithrombotic activities [17], as well as high affinities at various nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) [18,19,20]. 3,9-Diazabicyclo[3.3.1]nonanes showed the 5-HT3 receptor antagonist [21] and opioid δ and μ-receptor activities [22,23]. Triazabicyclo[3.3.1]nonane derivatives such as 2,6,9- and 3,7,9-triazabicyclo[3.3.1]nonanes [24,25,26,27,28] were synthesized from dimerization of α,β-unsaturated carbonyl compounds with alkylamines. Some 1,3,5,7-tetraazabicyclo[3.3.1]nonane derivatives have antithrombotic activities [29]. Although tremendous progress has been achieved in the synthesis of mono-, di-, and tri-azabicyclo[3.3.1]nonanes [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27], the synthesis of tetra- and penta-azabicyclo[3.3.1]nonane frameworks has rarely been disclosed in the literature [30,31,32,33].

Figure 1.

Azabicyclo[3.3.1]nonane-based natural products.

The microwave irradiation methodology is widely employed in organic reactions because it has several advantages over conventional heating, resulting in high yields, low by-products, rapid heating and easy purification [34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41]. Mechanistically, microwave irradiation affects the reaction through internal heating by direct coupling of microwave energy with the bulk reaction mixture. Furthermore, the eco-friendly ultrasound platform has receiving much interest due to its high impacts on organic synthesis, medicinal chemistry and materials science [42,43,44,45,46]. It leads to the formation of pure products in high yields and selectivity in a shorter reaction time. In continuation of our research work employing ultrasound and microwave irradiations in the synthesis of biologically active heterocycles [47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57], we envisaged herein an efficient and versatile one-pot protocol for rapid assembly of novel C2-symmetric 2,3,6,7,9-pentaazabicyclo[3.3.1]nonane derivatives through dimerization of 3-oxo-2-arylhydrazonopropanals with ammonium acetate via a double Mannich-type reaction under three different heating platforms: conventional, ultrasound and microwave irradiation. The structures of the obtained products are established from their single crystal X-ray analysis and spectral data (IR, MS, HRMS, 1H- and 13C-NMR).

2. Results

The intermolecular Mannich reaction is considered to be a powerful route for the synthesis of azacyclic products from acyclic substrates [58]. At first, the investigations focused on screening various reaction parameters (e.g., solvents, bases and heating techniques) for optimizing the reaction conditions of the double-Mannish reaction of the 3-oxo-2-arylhydrazonopropanal derivative 1a with ammonium acetate were thoroughly evaluated and the reaction was followed by TLC till almost full conversion of the starting substrates and the results are depicted in Table 1. Heating the 3-oxopropanal derivative 1a with double equivalents of ammonium acetate in ethanol under either reflux temperature (15 h), ultrasound irradiation (US) (120 min at 80 °C and 110 W), or microwave irradiation (MW) (30 min at 80 °C and 200 W) in the absence of catalysts, only a trace amount of product was detected by TLC (run 1, Table 1). When the reaction was heated at reflux using triethylamine (Et3N) as catalyst (15 mol%) for 4 h (as examined by TLC), it led to the formation of the 2,3,6,7,9-pentaazabicyclo[3.3.1]nonane derivative 2a in 70% isolated yield (run 2, Table 1). The structure of reaction product 2a was confirmed from its spectral data (IR, MS, HRMS, 1H- and 13C-NMR). 1H-NMR spectrum of compound 2a showed triplet at δ 4.30 (D2O-exchangeable) assigned to the NH proton and a doublet at δ 6.76 due to the symmetric-bridgehead H1 and H5-protons in addition to a multiplet at δ 7.3–7.95, corresponding to 16 aromatic protons. 13C-NMR spectrum of 2a exhibited symmetric 11 signals at δ 56.48, 118.94, 127.70, 127.98, 128.92, 129.99, 132.15, 136.98, 138.37, 141.88 and 189.39, corresponding to 30 aromatic and aliphatic carbons. When the same reaction was repeated under US (for 60 min) and MW (for 5 min), the product 2a was obtained in 82% and 87% yields, respectively (run 2, Table 1). For the same reaction, use of 25 mol% of Et3N resulted in a significant increase in the product yield, to 78%, 89% and 94% when the reaction was carried out at reflux (3 h), US (50 min) and MW (3 min), respectively (run 3, Table 1). Further increase in the amount of Et3N (30 mol%) could not significantly improve the yield, as shown in run 4, Table 1. Further evaluation of the effect of the molar ratio of 1a and ammonium acetate in the presence of 25 mol% of Et3N was attempted, where product 2a was formed in 66%, 73% and 80% yields after heating at reflux (3 h), US (50 min) and MW (3 min), respectively, when 1a and ammonium acetate (1:1 molar ratio) were employed (run 5, Table 1). Repeating the reaction of 1a and ammonium acetate (2:1 molar ratio) gave 60%, 68% and 73% yields of 2a upon heating at reflux (3 h), US (50 min) and MW (3 min), respectively (run 6, Table 1). Using methanol or isopropanol solvents instead of ethanol in the presence of Et3N (25 mol%) and 1:2 molar ratio of 1a and ammonium acetate had little effect on the product yields under all heating modes, as shown in runs 7 and 8, Table 1. Non-alcoholic solvents lowered the reaction yields and increased the reaction time, where employing n-hexane, acetic acid, dimethylformamide (DMF) or toluene as reaction solvents resulted in the formation of 2a in 30~35%, 40~52% and 50~65% yields, under reflux, US and MW conditions, respectively, as shown in runs 9–12, Table 1. Keeping ethanol as solvent, further attempts to evaluate the effect of base-types (pyridine, DABCO, DBU, NaHCO3, K2CO3, NaOH) on the reaction yields were studied and in all cases, regardless of whether an organic or inorganic base catalyst was employed (25 mol%), the overall yields decreased sharply; 10~20%, 10~28% and 15~35% yields, under the applied activation modes—thermal, US and MW—respectively (runs 13–18, Table 1). From the obtained data in Table 1, it can be concluded that EtOH/Et3N is the most effective reaction condition for achieving the stated goals.

Table 1.

Optimization the dimerization condition of 3-oxo-2-arylhydrazonopropanals 1a with ammonium acetate a.

| Run | Base-Catalyst (mol%) | Solvent | Conv. Heating | Sonication | MW Irradiation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yield b % | Time (h) | Yield b % | Time (min) | Yield b % | Time (min) | |||

| 1 | No catalyst | EtOH | trace | 15 | trace | 120 | trace | 30 |

| 2 | Et3N (15) | EtOH | 70 | 4 | 82 | 60 | 87 | 5 |

| 3 | Et3N (25) | EtOH | 78 c | 3 | 89 d | 50 | 94 | 3 |

| 4 | Et3N (30) | EtOH | 71 | 3 | 85 | 60 | 90 | 4 |

| 5 | Et3N (25) e | EtOH | 66 e | 3 | 73 e | 50 | 80e | 3 |

| 6 | Et3N (25) f | EtOH | 60 f | 3 | 68 f | 50 | 73f | 3 |

| 7 | Et3N (25) | MeOH | 71 | 4 | 82 | 50 | 89 | 4 |

| 8 | Et3N (25) | isopropanol | 70 | 4 | 80 | 60 | 88 | 4 |

| 9 | Et3N (25) | n-hexane | 34 | 6 | 52 | 80 | 63 | 10 |

| 10 | Et3N (25) | acetic acid | 32 | 4 | 40 | 70 | 50 | 6 |

| 11 | Et3N (25) | DMF | 30 | 6 | 45 | 100 | 55 | 10 |

| 12 | Et3N (25) | toluene | 35 | 5 | 50 | 90 | 65 | 10 |

| 13 | pyridine (25) | EtOH | 20 | 4 | 28 | 60 | 35 | 5 |

| 14 | DABCO (25) | EtOH | 17 | 5 | 20 | 80 | 28 | 7 |

| 15 | DBU (25) | EtOH | 15 | 5 | 18 | 70 | 25 | 8 |

| 16 | NaHCO3 (25) | EtOH | 10 | 6 | 10 | 80 | 15 | 10 |

| 17 | K2CO3 (25) | EtOH | 10 | 5 | 12 | 90 | 15 | 10 |

| 18 | NaOH (25) | EtOH | 12 | 5 | 14 | 80 | 18 | 9 |

a Reaction conditions: Arylhydrazonopropanal 1a (5 mmol), ammonium acetate (10 mmol) and base-catalyst (15~30 mol%) in solvent (7 mL) at reflux temperature for conventional heating 3~6 h, ultrasonic irradiation at 80 °C (110 W) for 50~100 min, or microwave irradiation at 80 °C (200 W) for 3~10 min. b isolated yield. c Yield was 20% after 50 min. d Yield was 35% after 15 min. e Compound 1a (5 mmol) and ammonium acetate (5 mmol) were used. f Compound 1a (10 mmol) and ammonium acetate (5 mmol) were used. Conv. = conventional, MW = microwave.

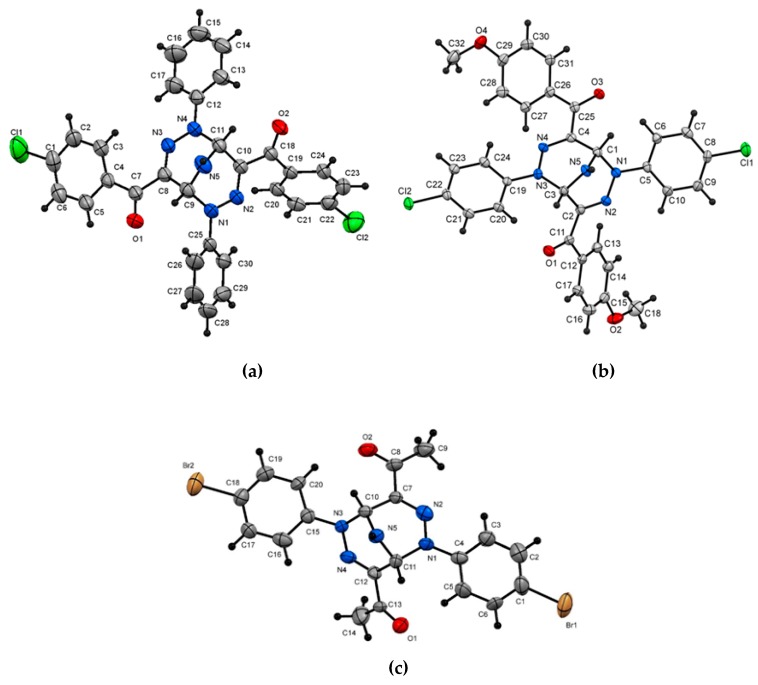

Next, a variety of C2-symmetric tetrasubstituted 2,3,6,7,9-pentaazabicyclo[3.3.1]nona-3,7-diene derivatives were prepared in accordance with the above optimized reaction conditions. The use of several 3-oxo-2-arylhydrazonopropanal derivatives 1a–p with ammonium acetate afforded the corresponding double Mannich-type products 2a–p in good to excellent isolated yields and the reactions were followed by TLC until full conversion of the starting substrates (Table 2). It was gratifying to see that the reaction proceeds well, with high isolated yields (81~94%) for all derivatives under microwave irradiation within 3~9 min at 80 °C (200 W). Reaction yields were slightly decreased by conducting the reaction under ultrasound at 80 °C (110 W), with the products being obtained in 73~89% isolated yields. When reactions were carried out under conventional heating mode, the isolated yields varied from 62 to 86% after 3~8 hours when followed by TLC. All the resulted products were established based on their elemental analyses and spectral data (IR, MS, HRMS, 1H- and 13C-NMR), as well as single crystal X-ray crystallography, of three examples, 2f, 2k and 2p, as shown in Figure 2a–c [59]. It is worth mentioning that the bicyclic scaffolds adopt a unique C2-symmetric V-shaped structures [60].

Table 2.

Et3N-catalyzed synthesis of 2,3,6,7,9-pentaazabicyclo[3.3.1]nona-3,7-dienes 2a–p.

| Run | Products | R | Ar | Conv. Heating a | Sonication a | MW a Irradiation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yield b% | Time (h) | Yield b % | Time (min) | Yield b % | Time (min) | ||||

| 1 | 2a | 4-FC6H4 | 4-ClC6H4 | 78 | 3 | 89 | 50 | 94 | 3 |

| 2 | 2b | 4-FC6H4 | 4-BrC6H4 | 77 | 4 | 87 | 60 | 93 | 4 |

| 3 | 2c | C6H5 | 4-ClC6H4 | 70 | 3 | 81 | 50 | 89 | 4 |

| 4 | 2d | C6H5 | 4-BrC6H4 | 72 | 5 | 82 | 70 | 90 | 6 |

| 5 | 2e | C6H5 | 2-NO2C6H4 | 68 | 4 | 80 | 70 | 86 | 5 |

| 6 | 2f | 4-ClC6H4 | C6H5 | 71 | 3 | 83 | 40 | 90 | 3 |

| 7 | 2g | 4-ClC6H4 | 4-BrC6H4 | 73 | 5 | 84 | 70 | 91 | 5 |

| 8 | 2h | 4-BrC6H4 | 4-ClC6H4 | 86 | 4 | 87 | 70 | 92 | 5 |

| 9 | 2i | 4-BrC6H4 | 4-BrC6H4 | 84 | 5 | 86 | 80 | 92 | 6 |

| 10 | 2j | 4-OMeC6H4 | C6H5 | 66 | 5 | 77 | 70 | 82 | 5 |

| 11 | 2k | 4-OMeC6H4 | 4-ClC6H4 | 65 | 6 | 77 | 90 | 81 | 6 |

| 12 | 2l | 4-OMeC6H4 | 4-BrC6H4 | 67 | 8 | 78 | 100 | 83 | 7 |

| 13 | 2m | 4-NO2C6H4 | 4-ClC6H4 | 67 | 7 | 79 | 110 | 84 | 7 |

| 14 | 2n | 4-NO2C6H4 | 4-BrC6H4 | 71 | 8 | 80 | 100 | 86 | 8 |

| 15 | 2o | CH3 | 4-ClC6H4 | 62 | 7 | 73 | 90 | 81 | 8 |

| 16 | 2p | CH3 | 4-BrC6H4 | 64 | 6 | 75 | 110 | 81 | 9 |

a Reaction conditions: 3-Oxo-2-arylhydrazonopropanals 1a–p (5 mmol), ammonium acetate (10 mmol) and Et3N (25 mol%) in EtOH (7 mL) at reflux temperature for conventional heating 3~8 h, ultrasonic irradiation at 80 °C (110 W) for 50~110 min, or microwave irradiation at 80 °C (200 W) for 3~9 min. b Isolated yields. Conv. = conventional, MW = microwave.

Figure 2.

ORTEP diagrams of the crystal structures of 2f (a), 2k (b), 2p (c).

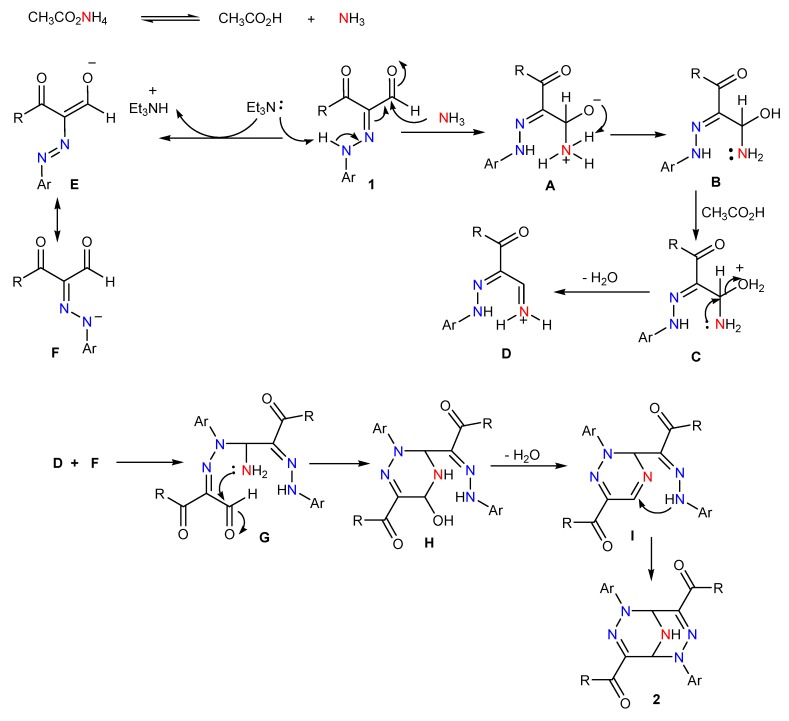

A plausible mechanism is proposed, as outlined in Scheme 1, on the basis of the aforementioned results for the tandem formation of the 2,3,6,7,9-pentaazabicyclo[3.3.1]nonane derivatives 2a–p through a Mannich-type reaction. At first, ammonium acetate is dissociated into ammonia and acetic acid. Then, nucleophilic addition of ammonia to the aldehydic carbonyl of compound 1, followed by dehydration through the intermediary A~C furnished the iminium ion intermediate D. A second molecule of structure 1 is deprotonated by Et3N as basic catalyst to form the arylazo-enolate ion intermediate E. The resonated intermediate F attacks the iminium ion intermediate D to form the non-isolated Mannich adduct G that cyclizes to form the triazacyclic intermediate H by intramolecular attacking of the amine function to the aldehyde function. Finally, loss of water molecule from H produced the pentaazabicyclo[3.3.1]nonane system 2.

Scheme 1.

Suggested reaction mechanism for 2,3,6,7,9-pentaazabicyclo[3.3.1]nonanes 2.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General Information

Melting points were recorded on a Griffin melting point apparatus and are reported uncorrected. IR spectra were recorded using KBr disks using a Perkin-Elmer System 2000 FT-IR spectrophotometer (Perkin Elmer, Shelton, CT, USA). 1H-NMR (600 MHz) and 13C-NMR (150 MHz) spectra were recorded at 25 °C using DMSO-d6 as solvent with TMS as internal standard on a Bruker DPX 600 super-conducting NMR spectrometer (Bruker, Karlsruhe, Germany). Chemical shifts δ are reported in ppm. Low-resolution electron impact mass spectra [MS (EI)] and high-resolution electron impact mass spectra [HRMS (EI)] were performed using a high-resolution GC-MS (DFS) thermo spectrometer at 70.1 eV using a magnetic sector mass analyzer (Thermo, Bremen, Germany). Follow-up of the reactions and checking homogeneity of the prepared compounds was carried out by using thin layer chromatography (TLC). Microwave experiments were carried out using a CEM Discover Labmate microwave apparatus (300 W with CHEMDRIVER software; Matthews, NC, USA). Reactions were conducted under microwave irradiation in heavy-walled Pyrextubes fitted with PCS caps (closed vessel under pressure). The X-ray crystal structures were determined by using a Rigaku R-AXISRAPID diffractometer (Rigaku, Tokyo, Japan) and Bruker X8 Prospector and the collection of single crystal data was made at room temperature by using Cu-Kα radiation. The data were collected at room temperature. The structures were solved by using direct methods and expanded using Fourier techniques. The non-hydrogen atoms were refined anisotropically. The structures were solved and refined using the Bruker SHELXTLSoftware Package (Structure solution program-SHELXS-97 and Refinement program-SHELXL97) [61].

Data were corrected for the absorption effects using the multi-scan method (SADABS). Sonication was performed in MKC6, Guyson ultrasonic bath (Model-MKC6, operating frequency 38 kHz ± 10% and an output power of 110 Watts) with a digital timer (6 s to 100 min) and a heater, allowing solution heating to be set from 20 to 80 °C in 1 °C increments. The inside tank dimensions are 150 × 300 × 150 mm (length × width × depth) with a fluid capacity of 6 L. The 3-oxo-2-arylhydrazonopropanal derivatives 1a–p were prepared following reported procedures in the literature [62].

3.2. Synthesis of 2,3,6,7,9-Pentaazabicyclo[3.3.1]nona-3,7-diene Derivatives 2a–p

3.2.1. General Method A

A mixture of the appropriate arylhydrazonopropanals 1a–p (5 mmol) and ammonium acetate (10 mmol) was dissolved in of ethanol (7 mL), then triethylamine (25 mol%) was added and the reaction mixture was refluxed for 3–8 h (monitored by TLC using a mixture of petroleum ether (bp 60–80):EtOAc (2:1)). The reaction mixture was then evaporated under reduced pressure and the solid product, so formed, was recrystallized from EtOH/DMF to give the corresponding 2,3,6,7,9-pentaazabicyclo[3.3.1]nonane products 2a–p.

3.2.2. General Method B

In a round-bottomed three-necked flask, a mixture of the appropriate arylhydrazonopropanals 1a–p (5 mmol) and ammonium acetate (10 mmol) in of ethanol (7 mL), then triethylamine (25 mol%) was added and the reaction mixture was sonicated in a MKC6, Guyson ultrasonic bath (Model-MKC6, operating frequency 38 kHz ± 10% and an output power of 110 W) for 50–110 min at 80 °C. The reaction was controlled by TLC and continued until the starting substrates were completely consumed, then left to cool to room temperature. In each case, the solid product, so formed, was collected by filtration, washed with ethanol, dried and recrystallized from EtOH/DMF to give the corresponding products 2a–p.

3.2.3. General Method C

In a process glass vial, a mixture of the appropriate arylhydrazonopropanals 1a–p (5 mmol) and ammonium acetate (10 mmol) in ethanol (7 mL), then triethylamine (25 mol%) was added. The vial was capped properly, and thereafter, the mixture was heated under microwave irradiating conditions at 80 °C and 300 W for the appropriate reaction time as listed in Table 2. After cooling to room temperature, the products were isolated by filtration, washed with ethanol, dried and recrystallized from EtOH/DMF to give the corresponding products 2a–p, see Supplementary materials.

2,6-Di(4-chlorophenyl)-4,8-di(4-fluorobenzoyl)-2,3,6,7,9-pentaazabicyclo[3.3.1]nona-3,7-diene (2a): Pale yellow color; m.p. 245–246 °C; IR (KBr): 3331, 3073, 1636, 1597 cm−1; 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ = 4.30 (t, 1H, J = 2.4 Hz, NH), 6.76 (d, 2H, J = 2.4 Hz, H-1 and H-5), 7.31 (t, 4H, J = 9 Hz), 7.45 (d, 4H, J = 9.6 Hz), 7.65 (d, 4H, J = 9 Hz), 7.93–7.95 (m, 4H); 13C-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ = 56.93, 115.45, 115.60, 119.49, 128.25, 129.44, 133.39, 133.45, 133.92, 138.74, 142.35, 164.03, 165.69, 188.35; MS (EI, 70 eV): m/z (%) = 588.90 (M+, 6), 463.0 (34), 314.0 (18), 138.0 (5), 123.0 (100), 95 (29); HRMS (EI): m/z calcd for C30H19Cl2F2N5O2: 589.0884; found: 589.0878.

2,6-Di(4-bromophenyl)-4,8-di(4-fluorobenzoyl)-2,3,6,7,9-pentaazabicyclo[3.3.1]nona-3,7-diene (2b): Yellow color; m.p. 216–217 °C; IR (KBr): 3332, 3065, 1633, 1597 cm−1; 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ = 4.30 (t, 1H, J = 2.4 Hz, NH), 6.76 (d, 2H, J = 2.4 Hz, H-1 and H-5), 7.29–7.33 (m, 4H), 7.56–7.60 (m, 8H), 7.92–7.95 (m, 4H); 13C-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ = 56.37, 114.97, 115.12, 115.83, 119.36, 131.84, 132.91, 132.97, 133.39, 133.41, 138.28, 142.26, 163.55, 165.21, 187.84; MS (EI, 70 eV): m/z (%) = 678.80 (M+, 5), 508.9 (19), 498.8 (3), 359.9 (10), 181.9 (3), 154.9 (8), 123.0 (100), 95.0 (27); HRMS (EI): m/z calcd for C30H19Br2F2N5O2: 676.9874; found: 676.9865.

4,8-Di(benzoyl)-2,6-di(4-chlorophenyl)-2,3,6,7,9-pentaazabicyclo[3.3.1]nona-3,7-diene (2c): Pale yellow color; m.p. 223–224 °C; IR (KBr): 3323, 3066, 1648, 1600 cm−1; 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ = 4.31 (t, 1H, J = 2.4 Hz, NH), 6.76 (d, 2H, J = 2.4 Hz, H-1 and H-5), 7.44 (d, 4H, J = 1.8 Hz), 7.49 (t, 4H, J = 7.8 Hz), 7.59 (t, 2H, J = 7.5 Hz), 7.63–7.65 (m, 4H), 7.83 (d, 4H, J = 7.2 Hz); 13C-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ = 56.48, 118.94, 127.70, 127.98, 128.92, 129.99, 132.15, 136.98, 138.37, 141.88, 189.39; MS (EI, 70 eV): m/z (%) = 553.30 (M+, 15.9), 448.2 (4), 427.2 (70), 138.1 (5), 127.0 (10), 105.1 (100), 77.0 (33); HRMS (EI): m/z calcd for C30H21Cl2N5O2: 553.1072; found: 553.1067.

4,8-Di(benzoyl)-2,6-di(4-bromophenyl)-2,3,6,7,9-pentaazabicyclo[3.3.1]nona-3,7-diene (2d): Pale yellow color; m.p. 245–247 °C; IR (KBr): 3334, 2919, 1634, 1593 cm−1; 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ = 4.34 (t, 1H, J = 2.4 Hz, NH), 6.78 (s, 2H, H-1, H-5), 7.48 (t, 4H, J = 7.8 Hz), 7.55–7.60 (m, 10H), 7.83 (t, 4H, J = 7.8 Hz); 13C-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ = 56.43, 115.79, 119.31, 127.99, 130.01, 131.81, 132.17, 136.96, 138.41, 142.28, 189.38; MS (EI, 70 eV): m/z (%) = 643.1 (M++2, 27), 538.1 (6), 471.1 (97), 354.1 (4), 340.1 (36), 171.0 (10), 105.0 (100), 77 (17); HRMS (EI): m/z calcd for C30H21Br2N5O2: 641.0062; found: 641.0048.

4,8-Di(benzoyl)-2,6-di(2-nitrophenyl)-2,3,6,7,9-pentaazabicyclo[3.3.1]nona-3,7-diene (2e): Pale yellow color; m.p. 233–234 °C; IR (KBr): 3302, 3063, 1664, 1577 cm−1; 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ = 4.52 (t, 1H, J = 2.4 Hz, NH), 6.71 (d, 2H, J = 2.4 Hz, H-1 and H-5), 7.38 (t, 4H, J = 7.5 Hz), 7.44 (t, 2H, J = 7.8 Hz), 7.50 (t, 2H, J = 7.8 Hz), 7.50 (d, 4H, J = 7.2 Hz), 7.80–7.86 (m, 4H), 8.00 (d, 2H, J = 7.8 Hz); 13C-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ = 58.65, 125.62, 125.74, 126.77, 127.92, 128.93, 131.57, 133.89, 136.93, 137.71, 139.64, 143.16, 189.91; MS (EI, 70 eV): m/z (%) = 575.20 (M+, 70), 558.2 (48), 527.2 (5), 438.2 (35), 410.2 (10), 305.1 (12), 214.1 (16), 105.0 (100), 77.0 (35); HRMS (EI): m/z calcd for C30H21N7O6: 575.1553; found: 575.1549.

4,8-Di(4-chlorobenzoyl)-2,6-diphenyl-2,3,6,7,9-pentaazabicyclo[3.3.1]nona-3,7-diene (2f): Yellow color; m.p. 215–216 °C; IR (KBr): 3337, 3029, 1632, 1589 cm−1; 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ = 4.25 (t, 1H, J = 2.4 Hz, NH), 6.77 (d, 2H, J = 2.4 Hz, H-1 and H-5), 7.11 (t, 2H, J = 7.5 Hz), 7.38–7.41 (m, 3H), 7.54–7.57 (m, 3H), 7.64–7.66 (m, 3H), 7.86–7.88 (m, 3H); 13C-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ = 56.46, 117.44, 123.85, 128.04, 129.10, 131.89, 135.80, 136.86, 137.77, 142.98, 188.04; MS (EI, 70 eV): m/z (%) = 553.10 (M+, 10), 461.0 (36), 414.1 (7), 387.1 (5), 321.0 (4), 296.1 (42), 139.0 (100), 111.0 (23), 77.0 (22); HRMS (EI): m/z calcd for C30H21Cl2N5O2: 553.1072; found: 553.1068.; Crystal Data, C30H21Cl2N5O2, M = 554.42, triclinic, crystal size = 0.140 × 0.260 × 0.370 mm, a = 6.3807(7) Å, b = 12.9107(13) Å, c = 16.2532(17) Å, α = 94.517(5)°, β = 97.765(5)°, γ = 99.214(5)°, V = 1302.6(2) Å3, T = 296(2) K, space group: P -1, Z = 2, calculated density = 1.414 g/cm3, no. of reflection measured 20549, θ max = 66.87°, R1 = 0.0557 (CCDC 1885322) [59].

2,6-Di(4-bromophenyl)-4,8-di(4-chlorobenzoyl)-2,3,6,7,9-pentaazabicyclo[3.3.1]nona-3,7-diene (2g): Orange color; m.p. 261–262 °C; IR (KBr): 3344, 2980, 1635, 1587 cm−1; 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ = 4.30 (t, 1H, J = 2.4 Hz, NH), 6.76 (d, 2H, J = 3 Hz, H-1 and H-5), 7.55 (dd, 4H, J =1.8 Hz, J = 1.8 Hz), 7.59 (s, 8H), 7.86 (dd, 4H, J = 1.8 Hz, J=1.8 Hz); 13C-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ = 56.42, 115.97, 119.43, 128.09, 131.84, 131.96, 135.57, 138.16, 142.22, 188.04; MS (EI, 70 eV): m/z (%) = 710.9 (M++2, 4), 540.9 (25), 514.9 (7), 480.9 (3), 437.0 (5), 375.9 (15), 154.9 (15), 139.0 (100), 111.0 (40), 90.0 (5), 75.0 (15); HRMS (EI): m/z calcd for C30H19Br2Cl2N5O2: 708.9283; found: 708.9279.

2,6-Di(4-chlorophenyl)-4,8-di(4-bromobenzoyl)-2,3,6,7,9-pentaazabicyclo[3.3.1]nona-3,7-diene (2h): Pale yallow color; m.p. 255–256 °C; IR (KBr): 3350, 3090, 1634, 1585 cm−1; 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ = 4.33 (t, 1H, J = 2.4 Hz, NH), 6.76 (d, 2H, J = 2.4 Hz, H-1 and H-5), 7.47 (d, 4H, J = 9 Hz), 7.66 (d, 4H, J = 9 Hz), 7.70 (d, 4H, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.80 (d, 4H, J = 8.4 Hz); 13C-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ = 56.50, 119.11, 126.13, 127.88, 128.97, 131.05, 132.09, 135.95, 138.09, 141.83, 188.22; MS (EI, 70 eV): m/z (%) = 710.7 (M++2, 6), 584.8 (47), 556.8 (3), 387.9 (7), 375.9 (22), 182.9 (100), 154.9 (36), 127.0 (33), 111.0 (26), 75.0 (15); HRMS (EI): m/z calcd for C30H19Br2Cl2N5O2: 708.92825; found: 708.9278.

4,8-Di(4-bromobenzoyl)-2,6-di(4-bromophenyl)-2,3,6,7,9-pentaazabicyclo[3.3.1]nona-3,7-diene (2i): Yellow color; m.p. 264–265 °C; IR (KBr): 3346, 2990, 1638, 1592 cm−1; 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ = 4.31 (t, 1H, J = 2.7 Hz, NH), 6.73 (d, 2H, J = 2.4 Hz, H-1 and H-5), 7.58–7.64 (m, 8H), 7.68 (d, 4H, J = 9 Hz), 7.80 (d, 4H, J = 8.4 Hz); 13C-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ = 56.43, 115.97, 119.46, 126.15, 131.04, 131.85, 132.10, 135.92, 138.12, 142.22, 188.19; MS (EI, 70 eV): m/z (%) = 800.7 (M++4, 2), 630.8 (18), 587.8 (6), 560.8 (12), 480.9 (16), 419.9 (8), 208.9 (12), 182.9 (100), 154.9 (80), 90.0 (12), 76.0 (46); HRMS (EI): m/z calcd for C30H19Br4N5O2: 796.8272; found: 796.8268.

4,8-Di(4-methoxybenzoyl)-2,6-diphenyl-2,3,6,7,9-pentaazabicyclo[3.3.1]nona-3,7-diene (2j): Pale yellow color; m.p. 237–238 °C; IR (KBr): 3328, 2974, 1626, 1596 cm−1; 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ = 3.82 (s, 6H, 2OCH3), 4.24 (t, 1H, J = 2.4 Hz, NH), 6.76 (d, 2H, J = 2.4 Hz, H-1, H-5), 7.03 (dd, 4H, J = 1.8 Hz, J = 1.8 Hz), 7.08 (t, 2H, J = 7.2 Hz), 7.37–7.39 (m, 4H, ArH), 7.64 (d, 4H, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.87–7.91 (m, 4H); 13C-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ = 55.41, 56.43, 113.38, 117.10, 123.42, 129.13, 129.45, 132.40, 138.53, 143.13, 162.57, 187.74; MS (EI, 70 eV): m/z (%) = 545.0 (M+, 11), 453.0 (25), 383.0 (3), 292.0 (22), 135.0 (100), 107.0 (5), 92.0 (12), 77.0 (20); HRMS (EI): m/z calcd for C32H27N5O4: 545.2063; found: 545.2058.

2,6-Di(4-chlorophenyl)-4,8-di(4-methoxybenzoyl)-2,3,6,7,9-pentaazabicyclo[3.3.1]nona-3,7-diene (2k): Yellow color; m.p. 247–249 °C; IR (KBr): 3319, 3007, 1597, 1566 cm−1; 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ = 3.81 (s, 6H, 2CH3O), 4.30 (t, 1H, J = 2.4 Hz, NH), 6.76 (d, 2H, J = 2.4 Hz, H-1, H-5), 7.03 (d, 4H, J = 9 Hz), 7.45 (d, 4H, J = 9 Hz), 7.66 (d, 4H, J = 9 Hz), 7.91 (d, 4H, J = 9 Hz); 13C-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ = 55.40, 56.03, 56.43, 113.18, 113.42, 118.48, 118.71, 118.92, 127.42, 128.96, 132.46, 138.83, 141.97, 162.41, 162.64, 162.84, 187.69; MS (EI, 70 eV): m/z (%) = 613.10 (M+, 7), 487.1 (25), 450.1 (3), 421.1 (5), 326.1 (10), 161.0 (3), 135.0 (100), 77.0 (10); HRMS (EI): m/z calcd for C32H25Cl2N5O4: 613.1284; found 613.1278. Crystal Data: C32H25Cl2N5O4, M = 614.49, monoclinic, crystal size = 0.200 × 0.120 × 0.020 mm, a = 25.381(2) Å, b = 7.6990(3) Å, c = 25.477(2) Å, α = 90°, β = 145.50(1)°, γ = 90°, V = 2819.7(8) Å3, T = -123.0 °C, space group: P21/c, Z = 4, calculated density = 1.447 g/cm3, no. of reflection measured 15678, θ max = 50.1°, R1 = 0.0403 (CCDC 1885339) [59].

2,6-Di(4-bromophenyl)-4,8-di(4-methoxybenzoyl)-2,3,6,7,9-pentaazabicyclo[3.3.1]nona-3,7-diene (2l): Pale yellow color; m.p. 255–256 °C; IR (KBr): 3321, 2968, 1673, 1596 cm−1; 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ = 3.82 (s, 6H, 2CH3O), 4.28 (t, 1H, J = 2.4 Hz, NH), 6.73 (d, 2H, J = 2.4 Hz, H-1, H-5), 7.01–7.03 (m, 4H), 7.55–7.59 (m, 8H), 7.88–7.89 (m, 4H); 13C-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ = 55.44, 56.34, 113.45, 115.46, 119.08, 129.22, 131.85, 132.46, 138.84, 142.35, 162.66, 187.68; MS (EI, 70 eV): m/z (%) = 702.8 (M++1, 5), 532.9 (20), 371.9 (7), 181.9 (3), 170.9 (6), 135.0 (100), 107.0 (7), 77.0 (13); HRMS (EI): m/z calcd for C32H25Br2N5O4: 701.0273; found: 701.0266.

2,6-Di(4-chlorophenyl)-4,8-di(4-nitrobenzoyl)-2,3,6,7,9-pentaazabicyclo[3.3.1]nona-3,7-diene (2m): Orange color; m.p. 221–222 °C; IR (KBr): 3329, 2971, 1659, 1599 cm−1; 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ = 4.36 (t, 1H, J = 2.4 Hz, NH), 6.80 (d, 2H, J = 2.4 Hz, H-1 and H-5), 7.46–7.48 (m, 4H), 7.66 (dd, 4H, J = 2.4 Hz, J = 2.4 Hz), 8.04–8.07 (m, 4H) 8.30–8.32 (m, 4H); 13C-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ = 56.71, 119.43, 122.98, 128.24, 128.95, 131.18, 137.88, 141.73, 142.64, 149.04, 162.24, 187.98; MS (EI, 70 eV): m/z (%) = 642.7 (M+, 4), 516.8 (18), 464.8 (16), 435.9 (22), 401.9 (20), 352.9 (16), 302.9 (12), 176.0 (10), 150.0 (100), 110.9 (58), 76.0 (32); HRMS (EI): m/z calcd for C30H19Cl2N7O6: 643.0774; found: 645.0741.

2,6-Di(4-bromophenyl)-4,8-di(4-nitrobenzoyl)-2,3,6,7,9-pentaazabicyclo[3.3.1]nona-3,7-diene (2n): Yellow color; m.p. 271–272 °C; IR (KBr): 3329, 3073, 1650, 1601 cm−1; 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ = 4.36 (t, 1H, J = 2.4 Hz, NH), 6.80 (d, 2H, J = 3 Hz, H-1 and H-5), 7.59–7.63 (m, 8H), 8.06 (d, 4H, J = 8.4 Hz), 8.31 (d, 4H, J = 9 Hz); 13C-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ = 56.65, 116.38, 119.80, 123.03, 131.23, 131.89, 137.93, 142.15, 142.65, 149.07, 162.28, 188.02; MS (EI, 70 eV): m/z (%) = 732.7 (M+, 6), 562.8 (36), 532.8 (21), 509.8 (8), 479.8 (14), 398.9 (20), 386.9 (13), 243.0 (10), 181.9 (23), 170.9 (37), 150.0 (100), 120.0 (22), 104.0 (63), 76.0 (56); HRMS (EI): m/z calcd for C30H19Br2N7O6: 732.9744; found: 732.9739.

4,8-Diacetyl-2,6-di(4-chlorophenyl)-2,3,6,7,9-pentaazabicyclo[3.3.1]nona-3,7-diene (2o): Pale yellow color; m.p. 228–230 °C; IR (KBr): 3248, 2995, 1656, 1593 cm−1; 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ = 2.33 (s, 6H, 2CH3), 4.05 (t, 1H, J = 2.4 Hz, NH), 6.41 (d, 2H, J = 2.4 Hz, H-1 and H-5), 7.47 (d, 4H, J = 9 Hz), 7.79 (d, 4H, J = 9 Hz); 13C-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ = 24.22, 55.99, 119.08, 127.54, 128.69, 139.15, 141.85, 194.72; MS (EI, 70 eV): m/z (%) = 429.2 (M+,28), 386.1 (14), 359.1 (7), 332.1 (3), 303.1(100), 261.1 (30), 234.1 (77), 198.1 (15), 138.0 (36), 111.0 (57), 75.0 (12); HRMS (EI): m/z calcd for C20H17Cl2N5O2: 429.0760; found: 429.0752.

4,8-Diacetyl-2,6-di(4-bromophenyl)-2,3,6,7,9-pentaazabicyclo[3.3.1]nona-3,7-diene (2p): Yellow color; m.p. 236–237 °C; IR (KBr): 3245, 3006, 1655, 1581 cm−1; 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ = 2.33 (s, 6H, 2CH3), 4.06 (t, 1H, J = 2.4 Hz, NH), 6.40 (s, 2H, H-1 and H-5), 7.59–7.58 (m, 4H), 7.74–7.72 (m, 4H); 13C-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ = 24.29, 55.92, 115.64, 119.46, 131.63, 139.19, 142.25, 194.78; MS (EI, 70 eV): m/z (%) = 519.1 (M+, 44), 476.1 (20), 449.1 (10), 422.0 (5), 347.1 (100), 305.1 (27), 280.1 (70), 266.1 (10), 182.0 (25), 157.0 (33), 143.0 (3), 91.1 (8); HRMS (EI): m/z calcd for C20H17Br2N5O2: 518.9729; found: 518.9727. Crystal Data, C20H17Br2N5O2, M = 519.19, monoclinic, crystal size = 0.130 × 0.090 × 0.020 mm, a = 11.766(2) Å, b = 10.114(2) Å, c = 17.408(3) Å, α = 90°, β = 103.573(8) °, γ = 90°, V = 2013.8(6)Å3, T = 20.0 °C, space group: P21, Z = 4, calculated density = 1.712 g/cm3, no. of reflection measured 11322, θmax = 51.1°, R1 = 0.0862 (CCDC 1888859) [59].

4. Conclusions

A new series of C2-symmetric 2,3,6,7,9-pentaazabicyclo[3.3.1]nonane derivatives were synthesized in high yields through one-pot double Mannich-type reaction of Et3N-catalyzed 3-oxo-2-arylhydrazonopropanals with double equivalents of ammonium acetate under three different heating platforms: conventional, ultrasound and microwave irradiation. Single crystal X-ray analysis supported the elucidation of the structures of the obtained products.

Acknowledgments

Use of the facilities of Analab/SAF through research grants GS01/01, GS01/05, GS03/01 and GS03/08 at the University of Kuwait are gratefully acknowledged.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary materials (1H and 13C-NMR spectral sheets) are available online.

Author Contributions

H.M.A.-M, K.M.D. and W.M.T. designed the research, wrote the manuscript, edited and prepared it for publication. H.M.A.-M and K.M.D. were also responsible for the correspondence of the manuscript. W.M.T. and M.A.S. carried out the experimental part. All authors approved the final version.

Funding

This research work was funded by the University of Kuwait, grant number SC07/13.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Footnotes

Sample Availability: Samples of the synthesized compounds are available from the corresponding authors.

References

- 1.Hamaker L.K., Cook J.M. The Synthesis of Macroline Related Sarpagine Alkaloids. Alkaloids: Chemical and Biological Perspectives. Volume 9 Elsevier Science; Amsterdam, The Netherlands: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keawpradub N., Kirby G.C., Steele J.C.P., Houghton P.J. Antiplasmodial Activity of Extracts and Alkaloids of Three Alstonia Species from Thailand. Planta Med. 1999;65:690–694. doi: 10.1055/s-1999-14043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Novartis A.-G., Novartis Pharma GmbH, Switz (1-Aza-bicyclo[3.3.1]non-4-yl)-[5-(1H-indol-5-yl)-heteroaryl]amines as Cholinergic Ligands of the n-AChR for the Treatment of Psychotic and Neurodegenerative Disorders. Patent WO2007068475. 2007 Jun 21;

- 4.Novartis A.-G., Novartis Pharma GmbH, Switz [(1H-Indol-5-yl)-heteroaryloxy]-(1-azabicyclo-[3.3.1]nonanes as Cholinergic Ligands of the n-AChR for the Treatment of Psychotic and Neurodegenrative Disorders. Patent WO2007068476. 2007 Jun 21;

- 5.Bonjoch J., Diaba F., Bradshaw B. Synthesis of 2-Azabicyclo[3.3.1]nonanes. Synthesis. 2011:993–1018. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1258420. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trost B.M., Tang W., Toste F.D. Divergent Enantioselective Synthesis of (−)-Galanthamine and (−)-Morphine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:14785–14803. doi: 10.1021/ja054449+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Proto S., Amat M., Pérez M., Ballette R., Romagnoli F., Mancinelli A., Bosch J. Model Studies on the Synthesis of Madangamine Alkaloids. Assembly of the Macrocyclic Rings. Org. Lett. 2012;14:3916–3919. doi: 10.1021/ol301672y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jang K.H., Kang G.W., Jeon J.-E., Lim C., Lee H.-S., Sim C.J., Oh K.-B., Shin J. Haliclonin A, a New Macrocyclic Diamide from the Sponge Haliclona sp. Org. Lett. 2009;11:1713–1716. doi: 10.1021/ol900282m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Orihara K., Kawagishi F., Yokoshima S., Fukuyama T. Synthetic Studies of Haliclonin A: Construction of the 3-Azabicyclo[3.3.1]nonane Skeleton with a Bridge that Forms the 17-Membered Ring. Synlett. 2018;29:769–772. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keawpradub N., Eno-Amooquaye E., Burke P.J., Houghton P.J. Cytotoxic activity of indole alkaloids from Alstonia macrophylla. Planta Med. 1999;65:311–315. doi: 10.1055/s-1999-13992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boeckler F., Gmeiner P. The structural evolution of dopamine D3 receptor ligands: Structure–activity relationships and selected neuropharmacological aspects. Pharmacol. Ther. 2006;112:281–333. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu Z.-W., Song S.-Y., Li L., Lu H.-L., Lieberman B., Huang Y.-S., Mach R.H. Synthesis and evaluation of tetrahydroindazole derivatives as sigma-2 receptor ligands. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2015;23:1463–1471. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2015.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arora S., Sinha N., Nair P., Chakka S.K., Sai K., Hajare A., Reddy A., Patil P., Sayyed M., Kamboj R.K., et al. Novel Compounds as DIPEPTIDYL Peptidase IV (DPP IV) inhibitors. 2010/0291020. US Patent. 2010 Nov 18;

- 14.Kolhatkar R., Cook C.D., Ghorai S.K., Deschamps J., Beardsley P.M., Reith M.E., Dutta A.K. Further structurally constrained analogues of cis-(6-benzhydrylpiperidin-3-yl)benzylamine with elucidation of bioactive conformation: discovery of 1,4-diazabicyclo[3.3.1]nonane derivatives and evaluation of their biological properties for the monoamine transporters. J. Med. Chem. 2004;47:5101–5113. doi: 10.1021/jm049796t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mishra M., Kolhatkar R., Zhen J., Parrington I., Reith M.E.A., Dutta A.K. Further structural optimization of cis-(6-benzhydryl-piperidin-3-yl)-benzylamine and 1,4-diazabicyclo-[3.3.1]nonane derivatives by introducing an exocyclic hydroxyl group: Interaction with dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine transporters. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008;16:2769–2778. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Annika B., Magnus B., Torbjorn H., Kurt-Jürgen H., Bertil S., Gert S. Bispidine Compounds Useful in the Treatment of Cardiac Arrhythmias. 6,887,881 B1. US Patent. 2005 May 3

- 17.Misra A., Kumar K.S.A., Jain M., Bajaj K., Shandilya S., Srivastava S., Shukla P., Barthwal M.K., Dikshit M., Dikshit D.K. Synthesis and evaluation of dual antiplatelet activity of bispidine derivatives of N-substituted pyroglutamic acids. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2016;110:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2016.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gündisch D., Eibl C. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor ligands, a patent review. Expert Opin. Ther. Patents. 2011;21:1867–1896. doi: 10.1517/13543776.2011.637919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eibl C., Munoz L., Tomassoli I., Stokes C., Papke R.L., Gündisch D. The 3,7-diazabicyclo-[3.3.1]nonane scaffold for subtype selective nicotinic acetylcholine receptor ligands. Part 2: Carboxamide derivatives with different spacer motifs. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2013;21:7309–7329. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.09.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tomassoli I., Gündisch D. The twin drug approach for novel nicotinic acetylcholine receptor Ligands. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2015;23:4375–4389. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2015.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bermudez J., Gaster L., Gregory J., Jerman J., Joiner G.F., King F.D., Rahman S.K. Synthesis and 5-HT 3 receptor antagonist potency of novel (endo) 3,9-diazabicyclo-[3.3.1]nonan-7-amino Derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1994;4:2373–2376. doi: 10.1016/S0960-894X(01)80393-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pinna G.A., Cignarella G., Loriga G., Murineddu G., Mussinu J.-M., Ruiu S., Faddad P., Frattad W. N-3(9)-Arylpropenyl-N-9(3)-propionyl-3,9-diazabicyclo-[3.3.1]nonanes as μ-Opioid Receptor Agonists. Effects on μ-Affinity of Arylalkenyl Chain Modifications. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2002;10:1929–1937. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0896(01)00436-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Loriga G., Lazzari P., Manca I., Ruiu S., Falzoi M., Murineddu G., Bottazzi M.E.H., Pinna G., Pinna G.A. Novel diazabicycloalkane delta opioid agonists. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2015;23:5527–5538. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2015.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tanaka K., Siwu E.R.O., Hirosaki S., Iwata T., Matsumoto R., Kitagawa Y., Pradipta A.R., Okamura M., Fukase K. Efficient synthesis of 2,6,9-triazabicyclo[3.3.1]nonanes through amine-mediated formal [4+4] reaction of unsaturated imines. Tetrahedron Lett. 2012;53:5899–5902. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2012.08.081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsutsui A., Tanaka K. 2,6,9-Triazabicyclo[3.3.1]nonanes as overlooked amino-modification products by acrolein. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2013;11:7208–7211. doi: 10.1039/c3ob41285g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsutsui A., Pradipta A.R., Saigitbatalova E., Kurbangalieva A., Tanaka K. Exclusive formation of imino[4+4]cycloaddition products with biologically relevant amines: plausible candidates for acrolein biomarkers and biofunctional modulators. Med. Chem. Commun. 2015;6:431–436. doi: 10.1039/C4MD00383G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Revesz L., Blum E., Wicki R. Synthesis of Novel Piperazine Based Building Blocks: 3,7,9-Triazabicyclo[3.3.1]nonane, 3,6,8-Triazabicyclo[3.2.2]nonane, 3-Oxa-7,9-diazabicyclo-[3.3.1]nonane and 3-Oxa-6,8-diazabicyclo[3.2.2]nonane. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005;46:5577–5580. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2005.06.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pradipta A.R., Tanaka K. Synthesis of 3,7,9- and 2,6,9-triazabicyclo[3.3.1]nonane derivatives. Heterocycles. 2013;87:2001–2014. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Herpel M., Rehse K. Nitrosation Products of Hexamethylenetetramine. Arch. Pharm. Pharm. Med. Chem. 1999;332:255–257. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4184(19997)332:7<255::AID-ARDP255>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bryukhanov A.Y., Golod E.L. Synthesis and Transformations of 1,3,5,7-Tetraazabicyclo-[3. 3.1]nonanes, Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2002;72:1299–1305. doi: 10.1023/A:1020860720137. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vagenknecht J., Zeman S. Some characteristics of 3,7-dinitro-, 3,7-dinitroso- and dinitrate compounds derived from 1,3,5,7-tetraazabicyclo[3. 3.1]nonane, J. Hazard. Mat. 2005;A119:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2004.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cordes A.W., Oakley R.T., Boeri R.T. Structure of a Bicyclic Sulfur-Nitrogen-Carbon Heterocyclic Molecule. Acta Cryst. 1985;C41:1833–1834. doi: 10.1107/S0108270185009659. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Behbehani H., Ibrahim H.M. An efficient ultrasonic-mediated one-pot synthesis of 2,3,6,7,9-pentaazabicyclo[3.3.1]nonanes via a N,N-dimethylformamide dimethylacetal catalyzed Mannich-like reaction. RSC Adv. 2016;6:52700–52709. doi: 10.1039/C6RA09210A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.De la Hoz A., Loupy A. Microwaves in Organic Synthesis. 3rd ed. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim, Germany: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pollastri M.P., Devine W.G. In: Microwave Synthesis in Green Techniques for Organic Synthesis and Medicinal Chemistry. Zhang W., Cue B., editors. Wiley; Chichester, UK: 2012. pp. 325–342. Charpter 12. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kappe C.O., Stadler A. Microwaves in Organic and Medicinal Chemistry. 2nd ed. Wiley; Weinheim, Germany: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang W., Cue B.W. Green Techniques for Organic Synthesis and Medicinal Chemistry. 2nd ed. Wiley & Sons, Ltd.; Hoboken, NK, USA: 2018. Chapter 17. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baig R.B.N., Varma R.S. Alternative energy input: mechanochemical, microwave and ultrasound-assisted organic synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012;41:1559–1584. doi: 10.1039/C1CS15204A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pedersen S.L., Tofteng A.P., Malik L., Jensen K.J. Microwave heating in solid-phase peptide synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012;41:1826–1844. doi: 10.1039/C1CS15214A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takkellapati S.R. Microwave-assisted Chemical Transformations. Curr. Org. Chem. 2013;17:2305–2322. doi: 10.2174/13852728113179990042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kappe C.O. How to measure reaction temperature in microwave-heated transformations. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013;42:4977–4990. doi: 10.1039/c3cs00010a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mason T.J., Lorimer J.P. Applied Sonochemistry: Uses of Power Ultrasound in Chemistry and Processing. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim, Germany: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ruano J.L.G., Parra A., Marzo L., Yuste F., Mastranzo V.M. One-pot synthesis of sulfonamides from methyl sulfinates using ultrasound. Tetrahedron. 2011;67:2905–2910. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2011.02.060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Puri S., Kaur B., Parmar A., Kumar H. Applications of Ultrasound in Organic Synthesis—A Green Approach. Curr. Org. Chem. 2013;17:1790–1828. doi: 10.2174/13852728113179990018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Banerjee B. Recent developments on ultrasound-assisted one-pot multicomponent synthesis of biologically relevant heterocycles. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2017;35:15–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2016.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chatel G. How sonochemistry contributes to green chemistry. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2018;40:117–122. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2017.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Al-Matar H.M., Dawood K.M., Tohamy W.M. Tandem one-pot synthesis of 2-arylcinnolin-6-one derivatives from arylhydrazonopropanals and acetoacetanilides using sustainable ultrasound and microwave platforms. RSC Adv. 2018;8:34459–34467. doi: 10.1039/C8RA06494F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Behbehani H., Dawood K.M., Ibrahim H.M., Mostafa N.S. Regio- and stereoselective route to bis-[3-methyl-1,1′,4′-triaryl-5-oxo-spiro-pyrazoline-4,5′-pyrazoline] derivatives via 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition under sonication. Arab. J. Chem. 2018;11:1053–1060. doi: 10.1016/j.arabjc.2017.05.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Khalil K.D., Al-Matar H.M. Studies on 2-Arylhydrazononitriles: Synthesis of 3-Aryl-2-arylhydrazopropanenitriles and Their Utility as Precursors to 2-Substituted Indoles, 2-Substituted-1,2,3-Triazoles, and 1-Substituted Pyrazolo[4,3-d]pyrimidines. Molecules. 2012;17:12225–12233. doi: 10.3390/molecules171012225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Al-Matar H.M., Riyadh S.M., Elnagdi M.H. Studies with enamines: Reactivity of N,N-dimethyl-N-[(E)-2-(4-nitrophenyl)-1-ethenyl]amine towards nitrilimine and aromatic diazonium salts. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2007;44:603–607. doi: 10.1002/jhet.5570440315. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dawood K.M., El-Deftar M.M. Microwave-Assisted Synthesis of 2-Substituted 4-Biarylyl-1,3-thiazoles by Carbon–Carbon Cross-Coupling in Water. Synthesis. 2010:1030–1038. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1218662. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Darweesh A.F., Shaaban M.R., Farag A.M., Metz P., Dawood K.M. Facile Access to Biaryls and 2-Acetyl-5-Arylbenzofurans via Suzuki Coupling in Water under Thermal and Microwave Conditions. Synthesis. 2010:3163–3173. doi: 10.1002/chin.201106102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Abdel-Aziz H.A., El-Zahabi H.S.A., Dawood K.M. Microwave-assisted synthesis and in-vitro anti-tumor activity of 1,3,4-triaryl-5-N-arylpyrazole-carboxamides. Eur J. Med. Chem. 2010;45:2427–2432. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2010.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dawood K.M., Farag A.M., El-Deftar M.M., Gardiner M., Abdelaziz H.A. Microwave-assisted synthesis of 5-arylbenzofuran-2-carboxylates via Suzuki coupling using a 2-quinolinealdoxime-Pd(II)-complex. Arkivoc. 2013;2013:210–226. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dawood K.M., Elamin M.B., Farag A.M. Microwave-assisted synthesis of 2-acetyl-5-arylthiophenes and 4-(5-arylthiophen-2-yl)thiazoles via Suzuki coupling in water. Arkivoc. 2015;7:50–62. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Behbehani H., Ibrahim H.M., Dawood K.M. Ultrasound-Assisted Regio- and Stereoselective Synthesis of Bis-[1′,4′-diaryl-1-oxo-spiro-benzosuberane-2,5′-pyrazoline] Derivatives via 1,3-Dipolar Cycloaddition. RSC Adv. 2015;5:25642–25649. doi: 10.1039/C5RA02972D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Basyouni W.M., El-Bayouki K.A.M., Tohamy W.M., Abbas S.Y. Silica Sulfuric Acid: An Efficient, Reusable, Heterogeneous Catalyst for the One-Pot, Five-Component Synthesis of Highly Functionalized Piperidine Derivatives. Synth. Commun. 2015;45:1073–1081. doi: 10.1080/00397911.2015.1005632. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tramontini M., Angiolini L. Mannich-Bases, Chemistry and Uses. CRC; Boca Raton, FL, USA: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 59.The Crystallographic Data for Compounds 2f (ref. CCDC 1885322), 2k (ref. CCDC 1885339) and 2p (ref. CCDC 1888859) Can Be Obtained on Request from the Director. Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center; Cambridge, UK: [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bishop R. Supramolecular Host–Guest Chemistry of Heterocyclic V-Shaped Molecules. Top. Heterocycl. Chem. 2009;18:37–74. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sheldrick G.M. A short history of SHELX. Acta Crystallogr. 2008;A64:112–122. doi: 10.1107/S0108767307043930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Al-Shiekh M.A., Medrassi H.Y., Elnagdi M.H., Hafez E.A. Substituted hydrazonals as building blocks in heterocyclic synthesis: A new route to arylhydrazonocinnolines. J. Chem. Res. 2007:432–436. doi: 10.3184/030823407X234617. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.