Abstract

Intrauterine adhesion (IUA) is one of the most common diseases of the reproductive system. Due to the high postoperative recurrence rate of IUA, it is crucial to identify the possible causes of pathogenesis and recurrence of this disease. In the present study, a high-throughput sequencing approach was applied to compare the vaginal microbiota between healthy women [healthy vaginal secretion (HVS) group] and patients with IUA [intrauterine adhesion patients' vaginal secretion (IAVS) group]. The results indicated that IUA had little effect on the number of vaginal bacterial species. However, at the phylum level, patients with IUA had a significantly lower percentage of Firmicutes and a higher percentage of Actinobacteria than the HVS group (P<0.05). At the genus level, ~50% of patients with IUA were found to have a marked reduction in probiotic Lactobacillus accompanied by an overgrowth of pathogenic Gardnerella and Prevotella (P<0.05), and the Principal Coordinates Analysis confirmed that 10/20 samples in the IAVS group were scattered far away from the HVS group. Therefore, it was concluded that the interaction between IUA and vaginal microbiota greatly influenced the vaginal diversity of patients with IUA. In order to increase the recovery rate and lower the recurrence rate of IUA, increasing the vaginal Lactobacillus population should be considered.

Keywords: Lactobacillus, intrauterine adhesion, high-throughput sequencing, Gardnerella

Introduction

Intrauterine adhesion (IUA) is an acquired uterine condition characterised by the formation of scar tissue inside the uterine cavity, which, in many cases, results in adherence to the opposing endometrium (1,2). Risk factors including age, myomectomy, obesity, delivery, pelvic infections and genital tuberculosis can increase the morbidity of IUA (1), and IUA can cause amenorrhea, abnormal uterine bleeding, sterility, consecutive spontaneous abortions, menstruation and abnormal placentation (3,4). Over the past two decades, the increased use of curettage and/or dilation has led to an increased prevalence of IUA. Furthermore, the recurrence of adhesion remains high, and curing IUA is challenging in patients with moderate to severe IUA (5).

Vaginal secretions and vaginal epithelial cells provide a rich source of nutrients that support bacterial growth (6), and the vaginal microbiota is made up of an extensive and varied spectrum of pathogenic and non-pathogenic organisms (7). The bacterial population present in the lower genital tract of females plays a key role in maternal and neonatal health. The normal vaginal microbiota in healthy women should be dominated by Lactobacillus species, with abnormal microbiota characterised by a low number of lactobacilli and a high number of anaerobic bacteria, such as Gardnerella vaginalis, Prevotella and Mobiluncus (8,9). Moreover, previous studies have indicated that vaginal dysbacteriosis is strongly related to postpartum endometritis, preterm delivery, pelvic inflammatory diseases, spontaneous abortion and the delivery of low birth weight infants (10–12).

Based on our knowledge, the pathological changes of IUA are bound to influence the physiology and metabolites in the uterus, which will cause side effects in the adjacent vaginal tissue and influence the vaginal microbial diversity. Therefore, whether IUA could also disrupt the microbial composition in the vagina, and if the presence of certain bacteria in the vaginal tract could affect the pathogenic condition of IUA was investigated. To answer these questions, 80 women with and without IUA were studied. Specifically, the microbial diversity between healthy women and women with moderate IUA were compared using high-throughput sequencing.

Patients and methods

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of The Second Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University (Nanchang, China). Patients provided written informed consent for sample collection.

Study groups and sampling

The trial enrolled 50 women aged between 16 and 33 years who were newly diagnosed with IUA during hysteroscopy examination between November 2017 and June 2018 at The Second Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University, based on the revised criteria of the American Fertility Society, [intrauterine adhesion vaginal secretion (IAVS) group]. Patients had not used vaginal medications, received cervical treatment or performed douching within the previous 7 days, and had not engaged in sexual activity within the previous 2 days. Thirty healthy women (15–35 years old; mean age, 29.46 years) were recruited as the control group between November 2017 and June 2018 at The Second Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University [healthy vaginal secretion (HVS) group]. Participants had no diagnosed endocrine or autoimmune disorders, cancer, severe pelvic adhesion, hysteromyoma, endometriosis, adenomyosis or acute inflammation. Self-administered vaginal swabs were used to collect vaginal specimens, which were immediately stored at −80°C for DNA extraction (Table I).

Table I.

Baseline patient demographics and characteristics.

| Variable | HVS group (n=30) | IAVS group (n=50) |

|---|---|---|

| Percentage of total enrollment, no. (%) | 30 (37.50) | 50 (62.50) |

| Age [years, mean (SD)] | 29.46±2.19 | 28.38±1.27 |

| Age at first sexual intercourse (years) | ||

| <18 | 5 (16.67) | 10 (20.00) |

| 18-22 | 13 (43.33) | 19 (38.00) |

| >22 | 12 (40.00) | 21 (42.00) |

| No. of abortions/complete curettage of uterine cavity | ||

| 1 | 9 (30.00) | 15 (30.00) |

| 2 | 13 (43.33) | 23 (46.00) |

| 3 | 8 (26.27) | 12 (24.00) |

| No. of deliveries | ||

| 0 | 10 (33.33) | 16 (32.00) |

| 1 | 12 (40.00) | 22 (44.00) |

| >2 | 8 (26.27) | 12 (24.00) |

| Degree of uterine adhesion, no. (%) | ||

| 0-grade | 30 (100) | 0 (0) |

| Low-grade | 0 (0) | 18 (36.00) |

| Middle-grade | 0 (0) | 27 (54.00) |

| High-grade | 0 (0) | 5 (10.00) |

HVS, healthy vaginal secretion group; IAVS, intrauterine adhesion patients' vaginal secretion group; SD, standard deviation.

Extraction of genomic DNA and high-throughput sequencing

For the extraction of bacterial DNA from vaginal samples, the combination of genomic DNA kits (Tiangen Biotech Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) and the bead beating method were used (13), and the concentration and quality of purified DNA was determined via a spectrophotometer at 230 nm (A230) and 260 nm (A260; NanoDrop; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). The V4 region of the 16S ribosomal (r)DNA genes in each sample was amplified using SYBR Green Master mix (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany) and 515F/806R primers (515F, 5′-GTGCCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA-3′; 806R, 5′-GGACTACVSGGGTATCTAAT-3′). PCR was conducted as follows: 98°C for 2 min, followed by 30 cycles of 98°C for 15 sec, 55°C for 30 sec and 72°C for 30 sec. PCR products were sequenced with an IlluminaHiSeq 2000 platform (GenBank accession no. SRP155123; Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) (14).

Bioinformatics and multivariate statistical analysis

Paired-end reads from the original DNA fragments were processed using Cutadapt (version 1.9.1, http://cutadapt.readthedocs.io/en/stable/) and UCHIME Algorithm (http://www.drive5.com/usearch/manual/uchime_algo.html) (15). Sequence analysis was subsequently performed using the UPARSE software package (version 7.0.100, http://drive5.com/uparse), and sequences with ≥97% similarity were assigned to the same operational taxonomic units (OTU). Then, QIIME software (version 1.9.1, http://qiime.org/) was used to analyse the α-diversity (within samples, indexes of observed-OTUs, Chao1, Shannon, Simpson, abundance-based coverage estimator metric, good's-coverage) and the β-diversity [among samples, principal component analysis, principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) and nonmetric multidimensional scaling] (16,17). The cluster analysis was preceded by determination of the weighted UniFrac distance using the QIIME software package (version 1.8.0) (18), and partial least squares discriminate analysis (PLS-DA) was preceded by the use of SIMCA-P software (version 11.5; Umetrics; Sartorius Stedim Biotech, Malmö, Sweden), and differently abundant taxa identifications were compared using linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe) analysis (Galaxy; http://huttenhower.sph.harvard.edu/galaxy/) (19). The statistical significance was set at P<0.05 for correction of multiple comparisons.

Results

Baseline characteristics of participants

Between November 2017 and June 2018, 80 women were recruited to either the IAVS group (50 patients with IUA) or HVS group (30 healthy women), and the baseline characteristics of patients in the two groups were similar (Table I).

All participants were thoroughly informed about their conditions, and the IAVS and HVS groups were well balanced with no marked differences. The age, age at first sexual intercourse, number of abortions, complete curettage of the uterine cavity, number of deliveries and degree of uterine adhesion are summarised in Table I. The vaginal samples of women with no IUA and those with mid-grade IUA were used for high-throughput sequencing.

Sequencing coverage

To compare the microbial diversity between HVS and IAVS groups, 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing analysis was applied to sequence the V4 hypervariable region of bacteria. Data were obtained by filtering the raw data, and sequences with >97% similarity were cultured to the same OTU. In total, 3,051,883 filtered clean reads (76,297.08 reads/sample) and 12,266 OTUs were obtained from all samples, with an average of 306.65 OTUs per group (Table II).

Table II.

Number of raw reads, clean reads, observed species and effective in groups HVS and IAVS by high-throughput sequencing.

| Sample name | Raw reads | Clean reads | Observed species | Effective (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HVS1 | 82299 | 80306 | 529 | 97.58 |

| HVS2 | 91596 | 86891 | 900 | 94.86 |

| HVS3 | 77376 | 76554 | 164 | 98.94 |

| HVS4 | 55907 | 55314 | 264 | 98.94 |

| HVS5 | 86040 | 80337 | 370 | 93.37 |

| HVS6 | 72413 | 70253 | 458 | 97.02 |

| HVS7 | 84510 | 80429 | 163 | 95.17 |

| HVS8 | 84881 | 80177 | 252 | 94.46 |

| HVS9 | 83311 | 80259 | 295 | 96.34 |

| HVS10 | 84538 | 80185 | 218 | 94.85 |

| HVS11 | 66322 | 64824 | 167 | 97.74 |

| HVS12 | 82364 | 80271 | 349 | 97.46 |

| HVS13 | 58278 | 57101 | 485 | 97.98 |

| HVS14 | 78482 | 77649 | 148 | 98.94 |

| HVS15 | 101853 | 98324 | 193 | 96.54 |

| HVS16 | 81362 | 80314 | 143 | 98.71 |

| HVS17 | 65697 | 63227 | 127 | 96.24 |

| HVS18 | 83160 | 80320 | 187 | 96.58 |

| HVS19 | 83135 | 80132 | 195 | 96.39 |

| HVS20 | 83759 | 80318 | 499 | 95.89 |

| IAVS1 | 80796 | 80112 | 156 | 99.15 |

| IAVS2 | 68475 | 64205 | 667 | 93.76 |

| IAVS3 | 85975 | 80132 | 230 | 93.2 |

| IAVS4 | 67704 | 65111 | 183 | 96.17 |

| IAVS5 | 84329 | 80170 | 271 | 95.07 |

| IAVS6 | 80902 | 80247 | 265 | 99.19 |

| IAVS7 | 84042 | 83435 | 283 | 99.28 |

| IAVS8 | 67329 | 66696 | 397 | 99.06 |

| IAVS9 | 84233 | 81691 | 191 | 96.98 |

| IAVS10 | 68959 | 64354 | 179 | 93.32 |

| IAVS11 | 78713 | 75827 | 228 | 96.33 |

| IAVS12 | 79026 | 75605 | 338 | 95.67 |

| IAVS13 | 81928 | 80129 | 296 | 97.8 |

| IAVS14 | 61256 | 57481 | 190 | 93.84 |

| IAVS15 | 71488 | 69808 | 379 | 97.65 |

| IAVS16 | 85869 | 80434 | 314 | 93.67 |

| IAVS17 | 84245 | 80046 | 244 | 95.02 |

| IAVS18 | 84923 | 80215 | 310 | 94.46 |

| IAVS19 | 97284 | 93566 | 781 | 96.18 |

| IAVS20 | 80790 | 79434 | 258 | 98.32 |

| Total | 3165549 | 3051883 | 12266 | / |

| Average | 79138.73 | 76297.08 | 306.65 | 96.45 |

HVS, healthy vaginal secretion group; IAVS, intrauterine adhesion patients' vaginal secretion group.

α-Diversity of the microbial community in the HVS and IAVS groups

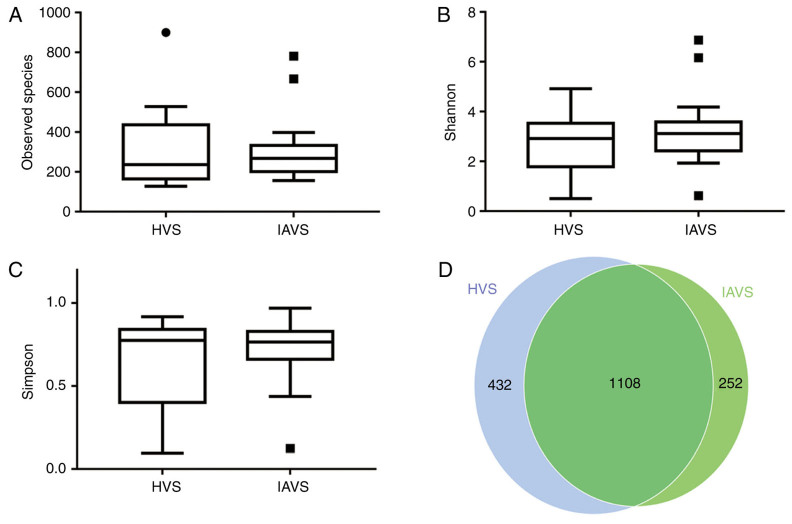

As presented in Fig. 1, the results for the observed species, Shannon index and Simpson index indicated that IUA had little effect on the α-diversity of the vaginal microbial community between HVS and IAVS groups, with 1,540 and 1,360 OTUs in the HVS and IAVS groups, respectively. The percentage of common OTUs was 71.95% (1,108/1,540) and 81.47% (1,108/1,360), respectively.

Figure 1.

Effects of intrauterine adhesion on the α-diversity of the vaginal microbial community. α-Diversity distances between the HVS and IAVS groups, revealing (A) the observed species, (B) the Shannon index, (C) the Simpson index and the (D) Scalar-Venn representation. The α-diversity distances did not significantly differ between the HVS and IAVS groups, and the Venn results indicated that there were 1,540 and 1,360 OTUs in the HVS and IAVS groups, respectively, with a total OTU number of 1,108. Circles and squares represent outliers. HVS, healthy vaginal secretion; IAVS, intrauterine adhesion patients' vaginal secretion; OTU, operational taxonomic units.

Composition of the microbial community in the HVS and IAVS groups at the phylum level

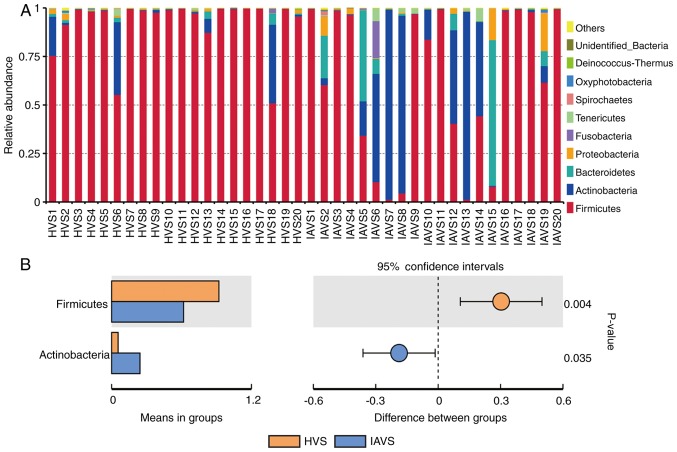

As presented in Fig. 2, data for the top 10 microorganism populations at the phylum level were analysed. At the phylum level, Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes and Proteobacteria constituted the four most predominant phyla in the HVS (92.12, 5.58, 0.92 and 0.64%, respectively) and IAVS (61.84, 24.37, 8.64 and 2.74%, respectively) groups, which accounted for 99.26 and 97.58% of the total sequences in the HVS and IAVS groups, respectively. In the HVS group, the percentage of Firmicutes was over 90% in most samples except for HVS1, HVS6 and HVS18, while only few Firmicutes were detected in samples IAVS5, IAVS6, IAVS7, IAVS8, IAVS13 and IAVS15. In addition, a marked increase in Actinobacteria and Bacteroidetes was observed in the IAVS group, particularly Actinobacteria in samples IAVS6, IAVS7, IAVS8, IAVS12, IAVS13 and IAVS14, and Bacteroidetes in samples IAVS5, IAVS6, IAVS12, IAVS15 and IAVS19. The statistical analysis also indicated that the HVS group had a significantly higher percentage of Firmicutes and a significantly lower percentage of Actinobacteria compared to the IAVS group (P<0.05; Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Analysis of microorganism populations at the phylum level. Microbiota composition of the vaginal cavity in the HVS and IAVS groups at (A) the phylum level and (B) the phyla that differed significantly between the HVS and IAVS groups. HVS, healthy vaginal secretion; IAVS, intrauterine adhesion patients' vaginal secretion.

Composition of the microbial community in the HVS and IAVS groups at the genus level

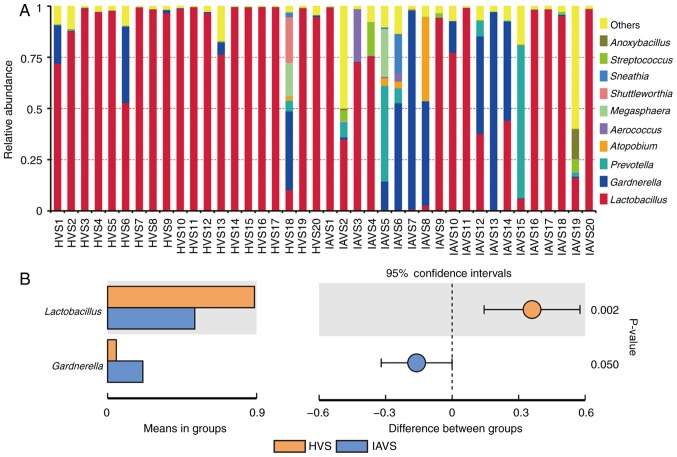

Similar to Fig. 2, the top 10 genera were analysed, with Lactobacillus revealed to account for >97% in most samples in the HVS group (Fig. 3A). For patients with IUA, the uterine disorder markedly reduced the percentage of Lactobacillus, but greatly enhanced the percentage of Gardnerella and Prevotella. Statistical analysis revealed a significant difference in Lactobacillus and Gardnerella between the HVS and IAVS groups (P<0.05; Fig. 3B). Notably, some samples (IAVS9, IAVS11, IAVS16, IAVS17, IAVS18 and IAVS20) also possessed a high percentage of Lactobacillus.

Figure 3.

Analysis of microorganism populations at the genus level. Microbiota composition of the vaginal cavity in the HVS and IAVS groups at (A) the genus level and (B) the genera that differed significantly between the HVS and IAVS groups. HVS, healthy vaginal secretion; IAVS, intrauterine adhesion patients' vaginal secretion.

β-Diversity of the microbial community in the HVS and IAVS groups

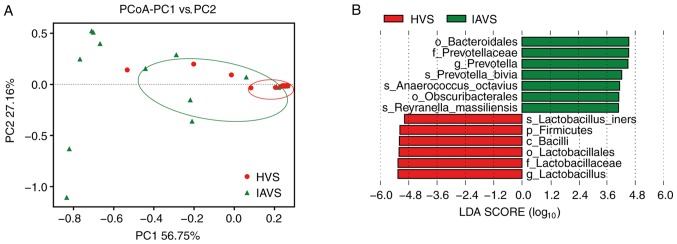

PCoA of the HVS and IAVS groups was carried out to explore differences in the microbial diversity between groups. As presented in Fig. 4, most samples in the HVS group were clustered together on the right, while 50% of samples (10/20) were scattered far away from the HVS group, indicating that IUA greatly altered the vaginal microbial diversity of IUV patients. In addition, the LEfSe analysis indicated that Bacteroidales (order), Prevotellaceae (family), Prevotella (genus), Prevotella bivia (species), Anaerococcus octavius (species), Obscuribacterales (order) and Reyranella massilliensis (species) were markedly higher in the IAVS group (P<0.05), while Lactobacillus iners (species), Firmicutes (phylum), Bacilli (class), Lactobacillales (order), Lactobacillaceae (family) and Lactobacillus (genus) were significantly higher in the HVS group (P<0.05).

Figure 4.

PCoA of microbial diversity in the HVS and IAVS groups. (A) PCoA of the β-diversity index and (B) linear discriminant analysis effect size analysis between the HVS and IAVS groups. HVS, healthy vaginal secretion; IAVS, intrauterine adhesion patients' vaginal secretion; LDA, linear discriminant analysis; PCoA, principal coordination analysis.

Discussion

As one of the most common diseases of the reproductive system in fertile women, the incidence of IUA is leading to an increase in intrauterine surgeries (e.g., hysteromyomectomy, dilation and curettage) (20). Although transcervical resection of the adhesion has been widely applied in the treatment of moderate and severe IUA (5), the high postoperative recurrence rates and low pregnancy rates presents a great challenge for clinical management (21).

Although the uterus is considered a sterile tissue, serious pathological changes of the uterine tissue of patients with IUA have a great influence on the blood supply, inflammatory and immune status and homeostasis of the uterine tissue (20). In addition, systemic disorders undoubtedly influence the microbial composition of the vagina. To date, many studies have been carried out to study the role of the vaginal microbiota in cancer, vaginal infection, abortion, sterility and menstrual disorders (9,22–27); however, no studies have explored the interaction between IUA and the vaginal microbiota.

In the present study, high-throughput sequencing was used to evaluate the effect of IUA on vaginal microbial diversity. A total of 80 fertile women (50 patients with IUA and 30 healthy women) were recruited, and vaginal samples of 20 healthy women (HVS group) and 20 mid-grade patients with IUA (IAVS group) were used for microbial evaluation. A total of 12,266 OTUs were obtained from all samples, and the average OTU number in each group was 306.65 (Table II). Although the Venn results indicated that the OTU numbers in the HVS and IAVS groups were 1,540 and 1,360, respectively, the findings for α-diversity of the observed species, Shannon index and Simpson index indicated that there was no significant difference between the groups. Therefore, IUA did not alter the microbial species between healthy women and those with IUA (Fig. 1).

When microbial communities were compared between the HVS and IAVS groups at the phylum level, it was observed that Firmicutes and Actinobacteria were the predominant phyla in the two groups. Firmicutes was markedly higher in the HVS group than in the IAVS group, while Actinobacteria was significantly lower in this group (P<0.05; Fig. 2). The Firmicutes usually have a Gram-positive cell wall structure, and most Firmicutes can produce endospores to defend against desiccation in extreme conditions. Thus, this phylum can be found in various environments, and is known to play an important role in beer, wine and cider spoilage (28). Moreover, Firmicutes constitute the largest portion of the mouse and human gut microbiota involved in energy resorption, and previous studies have confirmed that Firmicutes are part of a normal, healthy placental microbiome (29). Actinobacteria is another phylum of Gram-positive bacteria, and they are of great economic importance to humans due to their role in agriculture and forests, specifically their contribution to soil systems; however, some genera living in human faeces and vaginal sections have been reported to be harmful for human health (11,23–25,30).

At the genus level, Lactobacillus was clearly the dominant bacteria in the vaginal samples of healthy women, with a marked reduction in their percentage in the IAVS group accompanied by the overgrowth of pathogenic Gardnerella and Prevotella genera (P<0.05; Fig. 3). As in the intestines, disruption of the vaginal microbiota can lead to infection (31–33), and previous studies have consistently indicated that vaginal microbiota dominated by Lactobacillus was linked to good vaginal health (31,34). Lactobacilli in the vagina could protect the female urogenital tract against pathogen colonisation, and these bacteria can protect the female genitourinary tract against infections and help maintain a healthy genital system (9,35). Therefore, the significant reduction in Lactobacillus and overgrowth of Gardnerella and Prevotella observed in patients with IUA would disrupt the microbial homeostasis; however, 7 patients with IUA still possessed a high number of Lactobacilli in their vaginal samples, indicating that vaginal microbiota disorder only occurred in some patients with IUA. Future studies will focus on the differences in prognosis and recurrence between patients with IUA with high and low percentages of Lactobacillus, initially in an animal model and subsequently in volunteers. The β-diversity between HVS and IAVS groups was also compared using PCoA analysis, and it was revealed that ~50% of samples in the IAVS group (10/20) were scattered far away from the HVS groups, indicating that IUA altered the ratio of certain bacteria (Fig. 4).

In the present study, our group firstly explored the interaction between IUA and the vaginal microbiota using high-throughput sequencing technology, revealing that IUA significantly reduced the percentage of Lactobacillus and significantly increased Gardnerella and Prevotella in ~50% of patients with IUA, which may worsen the degree of IUA and increase the risk of recurrence. Therefore, supplementation of vaginal Lactobacillus during IUA treatment may help accelerate recovery and reduce the recurrence of IUA. However, due to the limited sample size of patients in the current study, a larger number of patients is required to obtain a more confident result.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 81503364 and 31560264), the Excellent Youth Foundation of JiangXi Scientific Committee (grant no. 20171BCB23028) and the Science and Technology Plan of Jianxi Health Planning Committee (grant no. 20175526).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Authors' contributions

TC, ZL and XD designed the experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. YK, YG, YR and CZ performed the experiments. All authors discussed the results and commented on the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the research in ensuring that the accuracy or integrity of any part of the study are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University. Patient samples were obtained with written informed consent in accordance with the Ethics Committee's requirements.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Salma U, Xue M, Sheikh SA, Guan X, Xu B, Zhang A, Huang L, Xu D. Role of transforming growth factor-β1 and smads signaling pathway in intrauterine adhesion. Mediators Inflamm. 2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/4158287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chi Y, He P, Lei L, Lan Y, Hu J, Meng Y, Hu L. Transdermal estrogen gel and oral aspirin combination therapy improves fertility prognosis via the promotion of endometrial receptivity in moderate to severe intrauterine adhesion. Mol Med Rep. 2018;17:6337–6344. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2018.8685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schenker JG. Etiology of and therapeutic approach to synechia uteri. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1996;65:109–113. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(95)02315-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Menzies D. Postoperative adhesions: Their treatment and relevance in clinical practice. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1993;75:147–153. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pabuccu R, Onalan G, Kaya C, Selam B, Ceyhan T, Ornek T, Kuzudisli E. Efficiency and pregnancy outcome of serial intrauterine device-guided hysteroscopic adhesiolysis of intrauterine synechiae. Fertil Steril. 2008;90:1973–1977. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.06.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nunn KL, Forney LJ. Unraveling the dynamics of the human vaginal microbiome. Yale J Biol Med. 2016;89:331–337. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen H, Luo T, Chen T, Wang G. Seminal bacterial composition in patients with obstructive and non-obstructive azoospermia. Exp Ther Med. 2018;15:2884–2890. doi: 10.3892/etm.2018.5778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van de Wijgert JHHM. The vaginal microbiome and sexually transmitted infections are interlinked: Consequences for treatment and prevention. PLoS Med. 2017;14:e1002478. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Witkin SS, Linhares IM. Why do lactobacilli dominate the human vaginal microbiota? BJOG. 2017;124:606–611. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.14390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kenyon C, Colebunders R, Crucitti T. The global epidemiology of bacterial vaginosis: A systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209:505–523. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bradshaw CS, Sobel JD. Current treatment of bacterial vaginosis-limitations and need for innovation. J Infect Dis. 2016;214(Suppl 1):S14–S20. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hay PE, Lamont RF, Taylor-Robinson D, Morgan DJ, Ison C, Pearson J. Abnormal bacterial colonisation of the genital tract and subsequent preterm delivery and late miscarriage. BMJ. 1994;308:295–298. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6924.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu X, Wu X, Qiu L, Wang D, Gan M, Chen X, Wei H, Xu F. Analysis of the intestinal microbial community structure of healthy and long-living elderly residents in Gaotian Village of Liuyang City. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2015;99:9085–9095. doi: 10.1007/s00253-015-6888-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu J, Lian F, Zhao L, Zhao Y, Chen X, Zhang X, Guo Y, Zhang C, Zhou Q, Xue Z, et al. Structural modulation of gut microbiota during alleviation of type 2 diabetes with a Chinese herbal formula. ISME J. 2015;9:552–562. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2014.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bolger A, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edgar RC. UPARSE: Highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat Methods. 2013;10:996–998. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Magurran AE. Wiley-Blackwell; Hoboken, NJ: 2004. Measuring Biological Diversity. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, Bittinger K, Bushman FD, Costello EK, Fierer N, Peña AG, Goodrich JK, Gordon JI. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods. 2010;7:335–336. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Afgan E, Baker D, Batut B, van den Beek M, Bouvier D, Cech M, Chilton J, Clements D, Coraor N, Grüning BA, et al. The Galaxy platform for accessible, reproducible and collaborative biomedical analyses: 2018 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:W537–W544. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johary J, Xue M, Zhu X, Xu D, Velu PP. Efficacy of estrogen therapy in patients with intrauterine adhesions: Systematic review. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21:44–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2013.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deans R, Abbott J. Review of intrauterine adhesions. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2010;17:555–569. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2010.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Younes JA, Lievens E, Hummelen R, van der Westen R, Reid G, Petrova MI. Women and their microbes: The unexpected friendship. Trends Microbiol. 2018;26:16–32. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2017.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nasioudis D, Linhares IM, Ledger WJ, Witkin SS. Bacterial vaginosis: A critical analysis of current knowledge. BJOG. 2017;124:61–69. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.14209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moreno I, Codoñer FM, Vilella F, Valbuena D, Martinez-Blanch JF, Jimenez-Almazán J, Alonso R, Alamá P, Remohí J, Pellicer A, et al. Evidence that the endometrial microbiota has an effect on implantation success or failure. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215:684–703. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.09.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Champer M, Wong AM, Champer J, Brito IL, Messer PW, Hou JY, Wright JD. The role of the vaginal microbiome in gynecological cancer. BJOG. 2018;125:309–315. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.14631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jenmalm MC. The mother-offspring dyad: Microbial transmission, immune interactions and allergy development. J Intern Med. 2017;282:484–495. doi: 10.1111/joim.12652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blaser MJ, Dominguez-Bello MG. The human microbiome before birth. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;20:558–560. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wolf M, Müller T, Dandekar T, Pollack JD. Phylogeny of Firmicutes with special reference to Mycoplasma (Mollicutes) as inferred from phosphoglycerate kinase amino acid sequence data. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2004;54:871–875. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.02868-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mor G, Kwon JY. Trophoblast-microbiome interaction: A new paradigm on immune regulation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(4 Suppl):S131–S137. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.06.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ningthoujam DS, Sanasam S, Tamreihao K, Salam N. Antagonistic activities of local actinomycete isolates against rice fungal pathogens. Afr J Microbiol Res. 2009;3:737–742. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Humphries C. Microbiome: Detecting diversity. Nature. 2017;550:S12–S14. doi: 10.1038/550S12a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martin DH. The microbiota of the vagina and its influence on women's health and disease. Am J Med Sci. 2012;343:2–9. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e31823ea228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anukam KC, Osazuwa EO, Ahonkhai I, Reid G. Lactobacillus vaginal microbiota of women attending a reproductive health care service in Benin city, Nigeria. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33:59–62. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000175367.15559.c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tachedjian G, Aldunate M, Bradshaw CS, Cone RA. The role of lactic acid production by probiotic Lactobacillus species in vaginal health. Res Microbiol. 2017;168:782–792. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2017.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reid G. Probiotic agents to protect the urogenital tract against infection. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;73:437S–443S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/73.2.437s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.