Abstract

Objective

The objective of this article is to present a rationale for the need of a history of chiropractic vertebral subluxation (CVS) theory based on primary sources.

Discussion

There is a dichotomy in the chiropractic profession around subluxation terminology, which has many facets. The literature around this topic spans social, economic, cultural, and scientific questions. By developing a rationale for a historical perspective of CVS theory, including the tracking of the historical development of ideas throughout the profession, a foundation for future discourse may emerge.

Conclusions

By using primary sources, ideas in chiropractic on the development of CVS theory are proposed. This introduction presents a basis for the need of a history of CVS theory and suggests how this work may be used to further philosophical dialogs in chiropractic.

Key Indexing Terms: Chiropractic, History

Introduction

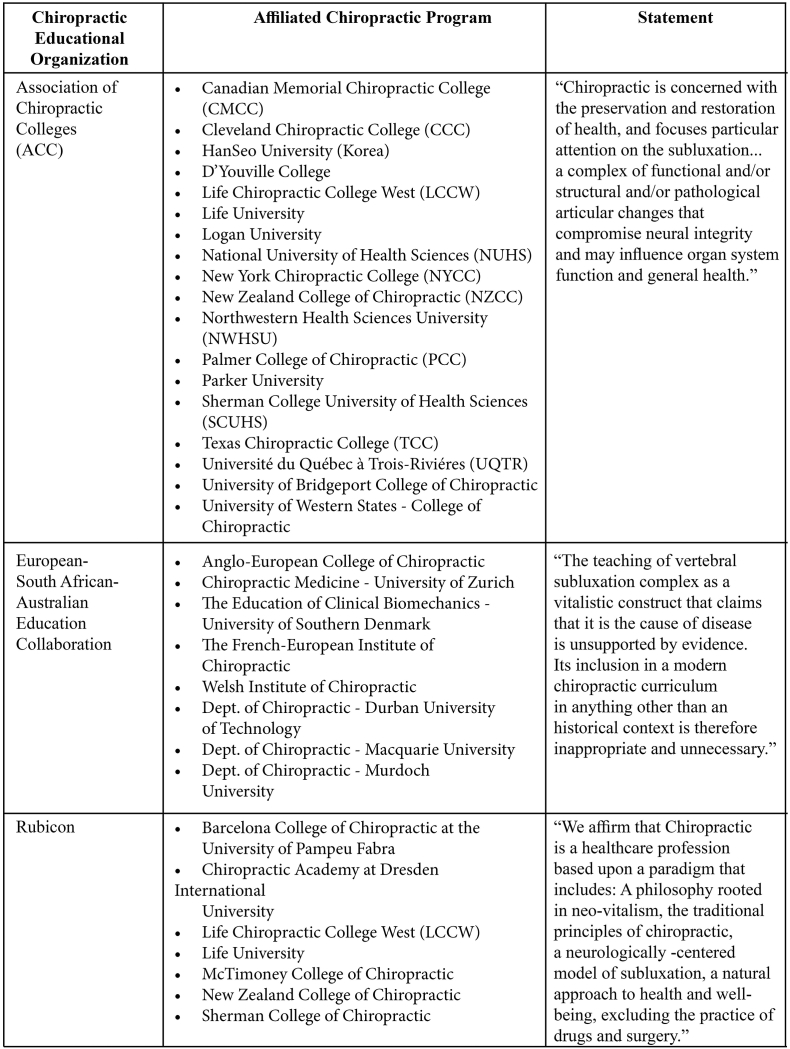

Chiropractic vertebral subluxation (CVS) is a chiropractic concept that dates back at least to 1902.1 It has been described by some authors as the central defining clinical principle of the chiropractic profession.2, 3 In the last decade, some have suggested that the term vertebral subluxation complex, which is the latest in a long line of terminology, should no longer be retained by the profession.4 Other groups, such as leaders from 9 European, Australian, and South African chiropractic training programs, have suggested that the term should only be used historically.5, 6 However, others (Association of Chiropractic Colleges and the Rubicon Group, made of up 7 chiropractic colleges in the United States, United Kingdom, and New Zealand [Fig 1]) suggest that CVS is the foundation of the profession.7, 8 To better understand these different viewpoints in the chiropractic profession, a thorough examination of primary sources from the literature is warranted. I propose that this exploration is relevant for modern clinical practice to determine if the arguments for various positions are based on a complete integration of the historical literature or only a partial or selected view.

Fig 1.

Samples of chiropractic educational organizations, colleges, and statements about chiropractic vertebral subluxation.

Some suggest that CVS should be a historical term only.5, 9 I suggest that this may be a difficult position to maintain because a majority of practitioners are content to keep the term,10 and many chiropractors state that they address CVS in practice.11, 12 For example, 62% of students in North America sampled in 1 study agreed that the emphasis of chiropractic practice is to eliminate CVS.13 Several institutions support definitions of CVS.7, 8 Some are actively researching and publishing on CVS.3, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20 It is the diagnosis chiropractors in the United States use for Medicare billing,21 and textbooks from the last decade use the term subluxation.22, 23, 24 At least 2 consensus statements were developed in the 1990s, embracing CVS as a foundation of the profession.7, 25

I propose that some of the arguments against the use of CVS terminology are based on references that may contain factual errors and literature oversights. This does not mean that there are flaws in every argument, nor does it mean that all of the literature is filled with inaccuracies. However, I have noticed several instances that include historical mistakes, which may have led to distortions in the literature about the term26, 27, 28, 29 or, in this authors’ opinion, do not adequately represent the CVS literature.2, 30, 31

Therefore, a comprehensive view of the literature on this topic could provide a better understanding among groups with varying viewpoints and may open up lines of discourse while also providing potentially new areas of research and practical relevance. A historical review may also establish a common ground to be better able to analyze these discussions in the literature for and against utilizing CVS terminology. The purpose of this article is to serve as an introduction to a historical exploration of CVS theory in the chiropractic profession and to develop a rationale for the need of a comprehensive history of CVS theory based on primary sources.

Discussion

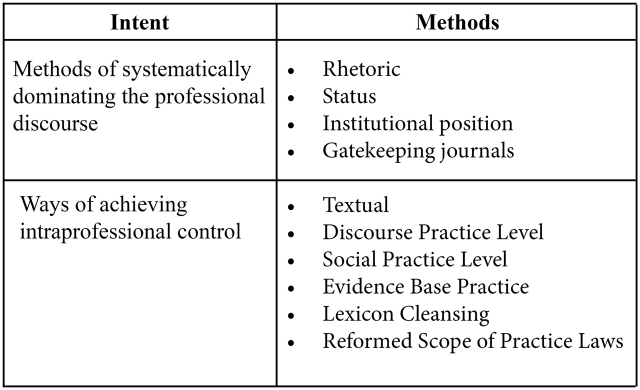

In 2011, Yvonne Villanueva-Russell used critical discourse analysis to examine the movements within the profession to establish identity.32, 33 She described a conflict between “everyday chiropractors” and a small group of academics and researchers. She noted that the surveys of chiropractors have flaws, but most chiropractors are content with the traditional lexicon.33 She concluded:

Analysis of the discourse suggests that debate over identity and cultural authority seems largely a politically-motivated intra-professional movement, focused more on paternalistic occupational control than over cohesion and identity. Hollenberg and Muzzin’s (2010) work on paradigm appropriation of acupuncture in Britain does not wholly seem to apply to the case of chiropractors in the United States. Rather than seeing the dominance of biomedicine engulf a subordinate marginal profession, the impetus to engage in paradigm assimilation (integrative medicine or the idea of becoming back/neck/pain specialist) is being driven from within the profession of chiropractic itself. Rather, changes to identity are being initiated internally by academic chiropractors as a coup d’état using the commitment to science (seen operating at the textual, discourse practice and social practice levels through [evidence-based practice], lexicon cleansing and reformed scope of practice laws) to achieve intra-professional control.33

This claim has yet to be discussed in the chiropractic literature in a substantial way. Villanueva-Russell continues:

The growing divide between the everyday chiropractor whose views are only available by proxy through methodologically flawed surveys are being systematically silenced by the claims of academic chiropractors, who utilize rhetoric, status, institutional position, and their roles as gatekeepers to journals as a means to dominate the discourse.33

Villanueva-Russell suggests that chiropractors should be included in the discourse and policy decisions about professional identity. She hypothesizes that scope of practice laws, insurance reimbursement, and licensure renewal may be affected by “lexicon cleansing” and an ideological power struggle (Fig 2).33

Fig 2.

Ways to gain control and dominate discourse.

In recent papers, several authors question the use of the term subluxation in the chiropractic profession. A cursory search on Google Scholar demonstrates that these papers were cited multiple times in the literature.34, 35, 36 However, none of the papers contain comprehensive references on the history of CVS. This may have resulted in potentially flawed conclusions. Chiropractors trust that the researchers accurately documented their arguments and were adequately versed in the historical literature and that editors and peer-reviewers are as well. My concern is that the views of chiropractors are influenced by academic chiropractors in “their roles as gatekeepers to journals as a means to dominate the discourse.”33

Although there is some literature on CVS and technique models, a comprehensive history of CVS is lacking.37, 38 Various reasons for this may include bias,39 school competition,40 and economic incentives.41 It is incumbent upon the chiropractic profession to examine CVS in light of historical facts and current research about chiropractors so that we may better assess the concerns stated by Villanueva-Russell.10, 11, 13, 33

Historical Errors in the Literature

Historical errors in publications may be passed down from 1 author to the next and affect the interpretation of concepts. I suggest that factual errors about the history of ideas in chiropractic go back to the earliest days of the discipline. One example is when D.D. Palmer’s rivals accused him of stealing chiropractic from the Bohemians.42 This claim was used originally to challenge Palmer’s authority as the founder of chiropractic.43 Textbooks written by rival school leaders also included these allegations.44, 45, 46 These texts also included history of spinal manipulation as a way to suggest that Palmer was trained in a manipulative tradition.44, 45, 46 I suggest that there is no basis in fact for that assumption. Chiropractic historian Gary Bovine writes, “It is very possible that Palmer, as did the Bohemians, Turks, and other bonesetters and healers from various cultures, gradually evolved the method of thrust adjusting independent of direct influences from anyone.”47 Palmer’s early writings on magnetic healing and chiropractic concur with Bovine’s assessment that he may have been self-taught and his methods developed over time with practice.48, 49

Another example is in an article reprinted by the New York State Chiropractic Association.26 The author included several factual errors to argue that the term subluxation be relegated to history. He suggested that D.D. Palmer did not use the term until 1907 and that the term was first used in 1906 in a text by Smith et al, and modern concepts of CVS are the same as they were during D.D. Palmer’s era.26 I would argue that these assumptions are incorrect because of factual errors supporting faulty arguments.1, 50, 51 These types of errors should be corrected in the literature before further discussion of the appropriateness of the term may be adequately undertaken.

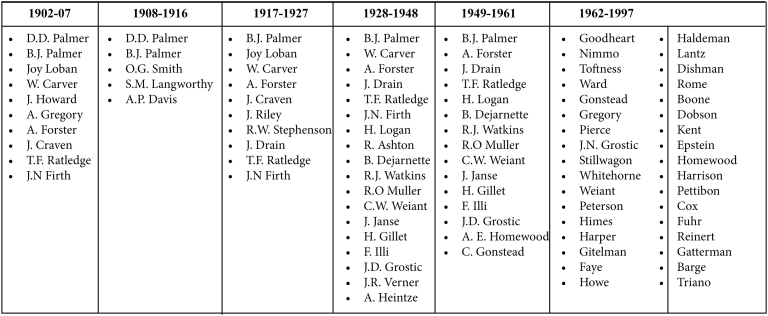

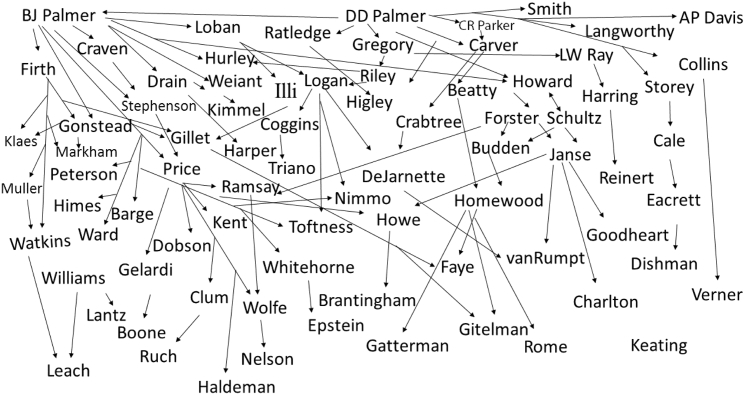

In another example, McGregor et al wrote, “The majority of practitioners historically were thought of as ‘straights,’ perceived the subluxation as the cause of disease, and its remedy to be manipulation/adjustment. This dominant faction was schooled through a single institution that boasted an enrollment of 505 students as early as 1910.”27 My argument with this statement is that most chiropractors in the first 80 years of the profession were trained to detect and correct CVS. The major schools included leaders who were subluxation theorists (Fig 3).22, 40, 45, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65 Many of the early leaders also hypothesized that 90% to 95% of disease processes were related to CVS, either as a primary or secondary cause.44, 45, 46, 57, 58, 66, 67, 68 These CVS theories evolved over the century, integrating Verner’s theory of the nonimpinging subluxation,69, 70 reflex concepts,64, 71, 72, 73 and theories developed by Speranksy, as well as dystrophic models.74, 75, 76, 77 These approaches viewed the CVS as an insult to the neurologic integrity of the organism that related to a wide variety of pathophysiological processes and was studied and taught in all factions of the profession.40

Fig 4.

Solon Langworthy (courtesy of Special Services, Palmer College of Chiropractic).

I propose that some of the confusion around these ideas stems from a general misunderstanding of the differences between treating pathology and focusing on the cause of pathophysiology. Pathophysiology is the study of altered function, which, if left unchecked, can result in altered cellular structure known as pathology. This differentiation is represented by the distinction between “disease” and “dis-ease” in the chiropractic literature. Although many chiropractors, including the Palmers, used these terms interchangeably over the years, examination of the historical literature demonstrates that D.D. Palmer and his students were focused on the pathophysiological processes primarily associated with neural disturbances related to spinal joint misalignments.44, 45, 46, 57, 64, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77 Pathophysiological processes associated with CVS were classed as “dis-ease,” which they differentiated from “disease.”

McGregor78 created categories to capture the subgroups of how chiropractors practice. The categories were general problems; biomechanical; biomechanical/general problems; biomechanical organic-visceral; CVS as a somatic dysfunction; and CVS as an obstruction to human health.27 However, I propose that this classification does not adequately capture the historical complexity of CVS theory when viewed as discreet practice styles. Many of the categories proposed by McGregor et al overlap and may not necessarily capture an accurate picture of chiropractic practice. Some of this supposition may be related to a misunderstanding of the history of CVS.

McGregor states:

Interestingly, the evolution of subluxation as an impediment to health appears to have been a medicolegal maneuver to distinguish chiropractic from medicine and to defend against a charge of practicing medicine without a license [18]. The defense took note of the philosophical perspective of Langworthy on the supremacy of nerves in modulating health. Together, the medicolegal defense linked with this philosophy to proffer subluxation as an obstruction to human health [18] (p. 66–67).27

The historical source they cite was by Wardwell,79 a sociologist who published extensively on the history of chiropractic.80 Wardwell’s sources included Rehm and Lerner.28, 29 Rehm’s primary source was Lerner’s report, a dramatic account of early chiropractic history.28 Lerner spent 2 years as an investigative lawyer exploring the early history of chiropractic. He interviewed B.J. Palmer and his staff and examined primary sources from early chiropractic writings, newspapers, and court cases.28 Lerner concluded that Langworthy’s text was used by the defense in the landmark Morikubo trial to support the contention that chiropractic has a distinct science, art, and philosophy. Lerner argued that the philosophy of chiropractic was born at the trial and largely derived from Langworthy (Fig 4).

Fig 3.

Subluxation theorists by time period.

However, I propose that several of Lerner’s conjectures were not supported and cannot be verified. For example, there were no court transcriptions of the Morikubo trial. There were only newspaper accounts. None of those accounts mention Langworthy. In addition, Morikubo claimed that Langworthy’s book was not used in his defense, which he and B.J. Palmer prepared for 6 months before the trial.81 The newspaper accounts do not specifically state that Langworthy’s text was discussed at the trial; although 1 account notes that Morikubo provided “every book on osteopathy and chiropractic published” to the prosecutor.82 Peters and Chance wrote, “we have found no evidence" that the defense used Langworthy’s book.81

I propose that other historical facts further challenge Lerner’s account. D.D. Palmer’s chiropractic paradigm had its origins in his published writings, going back to 1872 and 1887.83, 84 The first use of the term subluxation was by O.G. Smith in February 1902.1 D.D. Palmer first used the term in April 1902,85 and by 1903 he wrote about his philosophy, the primacy of the nerves, and innate intelligence, along with his thoughts about adjusting and the importance of intervertebral foramina.86, 87 In an advertisement on June 14, 1902, D.D. Palmer writes, “Our philosophy of treatment, removing the pressure, has the most rational claims upon the afflicted.”86 D.D. Palmer did not have high regard for Langworthy. Palmer accused him of plagiarism and referred to him as “Langworthless” in a private letter.88, 89 It has also been suggested that Modernized Chiropractic was written mostly by O.G. Smith.90, 91

The legal argument that chiropractic had a separate “philosophy, science, and art” was used in court cases for decades after the Morikubo trial40, 92 and may have been modeled on an earlier case: South Dakota v Brunning.91 Although legal strategies used to defend chiropractors in court were common, I argue that the first models of philosophy and CVS were not a “medicolegal maneuver.”27, 81, 93

It is not clear where this supposition originated. It is possibly due to authors citing previous sources. For example, Rehm cited Lerner’s conclusions. Rehm may have been inspired by Gibbons, the first editor of the chiropractic history journal, Chiropractic History.29, 94 Gibbons cited Lerner’s theories about Langworthy’s early leadership.94 Nevertheless, no one challenged these interpretations or challenged Rehm’s paper.29 Rehm was the first president of the Association for the History of Chiropractic, one of the first associate editors of the journal Chiropractic History, and advisor to the editor of Who’s Who in Chiropractic, which included a Necrology.95, 96 Several early articles from the Association for the History of Chiropractic leadership cited Rehm and expanded on Lerner’s writings.97, 98, 99, 100, 101, 102, 103, 104 Rehm’s article may be the source for much of the literature propagating these errors.40, 79, 92, 105, 106, 107, 108, 109

Sagan and Druyan wrote that we should always mistrust arguments from authority, and that approach applies here.110 However, a history of CVS should not be an appeal to authority; rather, it should be an appeal to historical accuracy and inclusion of the chiropractic canon or the central literature of the first century of the profession. By understanding history, we may better understand practice and chiropractic’s role in health care.

It is impossible in an overview to critically analyze every historical CVS theory. Such a critique should, however, follow an accurate history based on primary sources. This is important because some theories were developed from clinical research, and some were developed based on clinical practice, whereas others were passed down authoritatively from technique developers and school leaders. Motivations to develop CVS theory originated with intentions to help the sick and suffering and yet were sometimes influenced by economic and political forces.39, 111, 112, 113 All of the theories and models should be scrutinized and subjected to analysis and research.

Historiography

Antiquarianism is the collection of facts about the past without deep analysis. Historians John Moore and Mark Munzinger both cautioned the chiropractic profession to move beyond antiquarianism in the writing of history in chiropractic.114, 115 Moore proposed that historical writing in chiropractic should move away from “chiropractic history of chiropractic” and move toward “social history of chiropractic.” His concern was that most histories in chiropractic bordered on hagiography and did not emphasize the wider social implications surrounding chiropractic.114 He critiqued the defensive postures of chiropractic historical writing with an emphasis on the deviant role of chiropractic in the biomedical paradigm. Moore writes:

Continuation of an antiquarian, chip-on-the-shoulder defensive posture will simply mire chiropractic and its history in the sludge of the past and hinder a real understanding of the complex social and cultural realities represented by the emergence and growth of chiropractic as well as the nature of medical and scientific realities.114

He suggested that too much emphasis in the historical literature was traditionally placed on events and individuals and not enough on the wider contexts and societal implications. The defensive posture could also be applied to intraprofessional disputes.33

A brief history of CVS does not need to emphasize the social and cultural context. However, once a timeline of CVS theories and research is established, such an analysis should follow. To adequately respond to the accusation of lexicon cleansing and the ideological conflict in chiropractic that I suggest is rooted in academic discourse;33 an analysis of the academic literature is a much needed first step. Thus, the focus should be to identify and correct historical mistakes and develop greater depth of perspective about historical facts, research, and ideas. A scholarly debate and discourse may then emerge in light of the wider social forces shaping worldviews about health, healing, science, and holism.

Theories as Historical Anchors

Arguments for and against the use of CVS terminology should rest upon prior theory and research. Without making this lineage explicit, the modern debate may lack historical anchors. Viewing theories as anchors may keep the profession moored to the chiropractic paradigm. Some examples might help to demonstrate the relevance of this approach for practice and the role of chiropractic in health care.

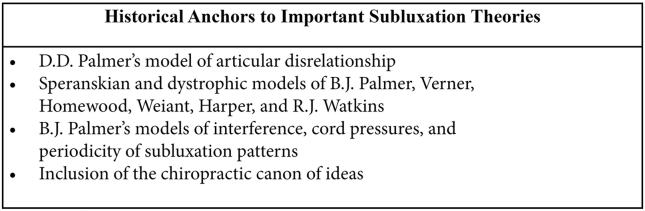

A recent discussion of chiropractic identity highlights neurologic imbalance as a “new” way to describe CVS,116 and yet such an approach can be found in the theories of B.J. Palmer,74 Verner,69 Homewood,55 Harper,65 and Peterson, Watkins, and Himes.76 As another example, recent arguments against CVS cite papers in the literature dating to the late 1980s,34 some of which are lacking in literature reviews on CVS history.30, 102 As well, several arguments in the literature attribute a “bone out of place” model to D.D. Palmer when a deeper analysis of his writings and the literature demonstrates that articular models of CVS, which came into prominence in the 1980s, could actually be traced to his model of CVS.52, 55, 75, 77, 117, 118 Also, I propose that few sources accurately describe the contributions to modern theory initiated by B.J. Palmer, such as his interference theory,119 cord pressure model,120 and periodic CVS model related to rhythmic pattern analysis.75 Finally, the prominent role of reflex models in CVS theory is not apparent in the recent peer-reviewed literature (Fig 5).

Fig 5.

Subluxation theories as historical anchors.

These types of problems could foster misunderstandings about the history of ideas in chiropractic, which could reduce the depth of understanding of the chiropractic paradigm. Discussions of the use of CVS should reflect the most complete base of knowledge available and include consensus models as well as operational models.

For example, Owens distinguishes between consensus models and operational models. He writes:

While consensus models are very broad in order to encompass all of their constituents, they are actually fairly useless for research purposes. Our greatest need in this area is for an “operational definition” that describes subluxation according to the measurements or procedures used to locate and analyze it. The operational definition is the model that can be tested for reliability and validity using the tools of science.121

He explains that most chiropractic techniques use procedures that have not been scientifically studied and validated. Operational definitions would help to accomplish this goal. Thus, as we explore the history of the CVS, it is vital to keep in mind that many of the definitions and assessments still must be operationally defined and scientifically studied.

Multiple Perspectives and Evidence in Chiropractic

The history of the chiropractic profession has been described in terms of social,79, 122 political,40 economic,111, 113 and psychological factors.39 In 2005, professionalization of chiropractic was analyzed from a sociologic perspective by building upon previous theory.123 This article proposed that a second phase of chiropractic’s professionalization was shaped by 2 dominant external forces: orthodox medicine and managed care organizations. Even though professionalization was initially achieved through licensure and accreditation, these 2 external forces dictated “how knowledge claims of expertise and practice are validated by positivistic science and how [evidence-based medicine] also serves as a crucial element to attain professional status and legitimacy.”123 This perspective on legitimacy fed into the internal conflicts in the profession, primarily because a positivistic perspective was more amenable to those in the profession who were epistemologically aligned with orthodox medicine.

The recent trend in the profession to prioritize truth claims based on evidence-based practice (EBP) was started in the 1990s before many critiques of its efficacy for manual medicine or complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) were developed.34, 123, 124, 125, 126, 127, 128 There have been several initiatives in the chiropractic profession to teach EBP literacy online and institutionally.129, 130, 131, 132, 133 It is not clear whether these trends have included varied types of evidence from chiropractic’s first 100 years of theory, clinical practice, and research into CVS.

Villanueva-Russell proposed that EBP was being used for ideological control of the chiropractic profession by a minority of academics,33 and that “EBP within chiropractic is really a political war against the philosophical roots of the chiropractic profession . . ..”134 Epistemological and ontological conflicts between EBP, social sciences, and CAM have been noted,135, 136, 137 and other holistic research strategies have been proposed.6, 123, 124, 138, 139 Mixed methods research,140 multiple levels of evidence,127 and pluralistic stances toward knowledge have been proposed to apply EBP to CAM.135 Recent articles have suggested at least 8 perspectives through which chiropractic theories might be viewed and at least 5 levels of thinking that chiropractors utilize to understand themselves and the profession.39, 125

In a critique of the overreliance of EBP in sociologic research, Humphries writes:

On the face of it, it should be regarded as a shocking revelation that policy and practice have not been informed by evidence, as otherwise how, and on what basis, can a knowledge base be built? At the same time, the collection of evidence is a complex social activity, and is influenced by competing interests.137

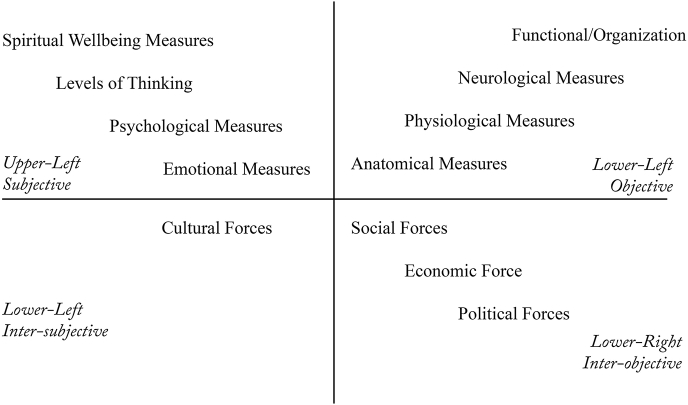

I propose that a deep analysis of the CVS should reflect the many levels of evidence that were used to establish the profession. That evidence could then be explored and reevaluated based on multiple methods of research from several perspectives, including the contextual nature of knowledge acquisition. Not 1 perspective is adequate to explain or critique CVS models, especially because the theories developed as a part of a wider chiropractic paradigm that included physiological, emotional, psychological, and spiritual elements set within cultural, social, political, and economic forces (Fig 6).

Fig 6.

Chiropractic vertebral subluxation perspectives in 4 quadrants.

Chiropractic Subluxation and Philosophy

The view that CVS could be researched, apart from the psycho-spiritual philosophical theories originated by D.D. Palmer, was proposed at Sherman College in the 1990s,121, 141, 142, 143, 144, 145 which evolved from the straight chiropractic movement from the 1970s146 and intercollegiate consensus definitions of CVS.60, 147, 148 This perspective views the CVS as a clinically relevant anatomic and neurophysiological phenomenon that relates to the body’s inherent self-organizing and self-healing structures.39, 142, 149, 150 By effectively bracketing the older philosophical terminology without dismissing it, the clinical, anatomic, and physiological elements of CVS might be analyzed, researched, and explored independently.

This approach may be relevant for this series of articles because many of the theories in the profession were developed outside of the Palmer School and may have been created in reaction to the Palmer approach (Fig 7). Thus, many theories may have been developed without any overt philosophical dimensions apart from the inherent self-healing and self-organizing aspects of the living system and the role of the nervous system in that process.58, 60, 64, 77, 118, 151, 152, 153

Fig 7.

Chiropractic vertebral subluxation theorists through their teacher-student relationships back to D.D. Palmer.

By separating CVS theory from the philosophy of chiropractic, a more unifying discourse may emerge. A research and theory agenda could be forwarded without dismissing the classical elements associated with CVS, such as innate intelligence and mental impulse. The self-organizing and self-healing hypothesized to emerge in relation to CVS correction could then be researched on its own terms.

This differentiated approach is also useful because it does not rely on extreme vitalism and is more in-line with what Donceel referred to as “moderate vitalism” as noted by Koch.141 Integrative and holistic approaches to medicine include similar viewpoints.154 Some systems and complexity theorists eschew the term vitalism altogether because of its historic implications and emphasize, instead, emergent and self-organizing behavior in living systems.155

Chiropractic authors have traditionally combined CVS theory with philosophy and art. A complete history needs to focus on objective definitions of CVS. This approach avoids some of the categorical errors,142 logical fallacies,156 and straw man arguments common in the literature.51 The purpose of a history of CVS does not need to be based on politics, scope of practice debates, or philosophical concepts like intelligence and mental impulse in isolation; however, some of these topics may be relevant in the context of the evolution of models.

Over the course of chiropractic’s first century, the term subluxation grew in complexity. Each iteration of technique, research, and theory led to more complex ways to detect, correct, and study the CVS. In the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s, this complexity grew to such a degree that terms such as subluxation complex, chiropractic vertebral subluxation, vertebral subluxation complex, and subluxation syndrome were developed.22, 157, 158, 159 Some have suggested that this complexity points to irrelevance for the term.2 Several consensus statements throughout the profession have suggested that it points to a robust clinical phenomenon that is best understood with multiple levels of analysis.7, 25

By describing theory and CVS as a clinical entity that may be studied, CVS may come to represent the complexity and history of ideas in chiropractic. Each multiplication of components and mechanisms increases the research challenges. The research agenda for chiropractic could be reframed by such a historical approach.

Limitations

This article reflects 1 person’s interpretation of historical writings and theories. It is acknowledged that the author’s perspectives on chiropractic practice, epistemology, and history can influence this writing. A narrative review of the historical literature does have its limitations, even though the author has reviewed an abundance of literature on this topic. Without detailed search parameters, inclusion and exclusion criteria, synthesis methods, a standard critical appraisal of the literature reviewed, and evaluation of bias, it is acknowledged that conclusions do need to be made with caution and within the historical context from which they are made. Future research into this area of inquiry would benefit from a more systematized approach.

Conclusions

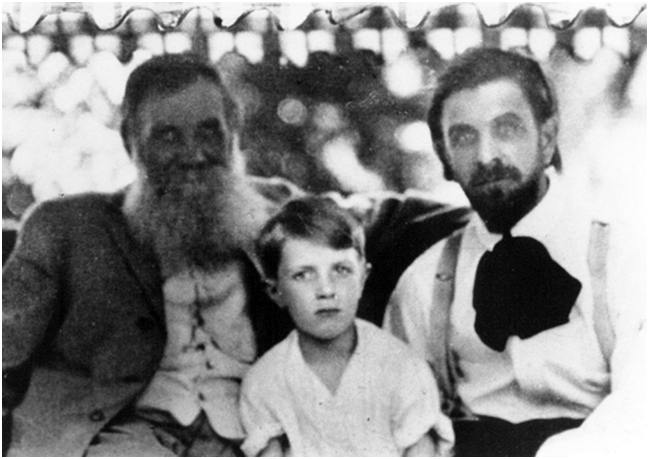

The history of ideas in chiropractic starts with D.D. Palmer.52, 66, 160 From Palmer, we can trace a lineage of significant thinkers in chiropractic and the evolution of chiropractic ideas alongside the distinctive Palmer School of Chiropractic (Fig 8). An emphasis on teacher–student relationships and the use of references to trace the development of ideas is an important way to explore this history.

Fig 8.

D.D. Palmer, B.J. Palmer, and Dave Palmer circa 1913 (courtesy of Special Services, Palmer College of Chiropractic).

This paper presents a basis for the need for a far-reaching history of CVS and suggests how such work may be used to further philosophical dialogs in chiropractic. The series of articles that follows is meant to take a step towards productive dialogue that is needed in the profession. It is not meant to be a one-sided argument for the CVS perspective; although it may seem that way to those who agree with the statement that “the subluxation is dead.”26 To that point of view, any discussion of the history of CVS that does not dissect each and every theory is inherently one sided.

Previous generations were familiar with this history, even though few theorists seemed to have integrated all of the relevant literature, possibly owing to school and personal biases and the dearth of historical data available to many at different points in time. This series of articles is an attempt to introduce the current generation of chiropractors to their own literature and provide my analysis of this information. There have been several prior valiant attempts at comprehensive reviews of CVS theory. These articles are written in that spirit, to capture the past so that it might be relevant for the present and help to pave the way for the future.

Practical Applications

-

•

This series of articles provides an interpretation of the history and development of chiropractic vertebral subluxation theories.

-

•

This series aims to assist modern chiropractors to interpret the literature and develop new research plans.

Alt-text: Unlabelled Box

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges Brian McAulay, DC, PhD, David Russell, DC, Stevan Walton, DC, Timothy J. Faulkner, DC, Joseph Foley, DC, and the Tom and Mae Bahan Library at Sherman College of Chiropractic for their assistance.

Funding Sources and Conflicts of Interest

The author received funding from the Association for Reorganizational Healing Practice and the International Chiropractic Pediatric Association for writing this series of papers. No conflicts of interest were reported for this study.

Contributorship Information

Concept development (provided idea for the research): S.A.S.

Design (planned the methods to generate the results): S.A.S.

Supervision (provided oversight, responsible for organization and implementation, writing of the manuscript): S.A.S.

Data collection/processing (responsible for experiments, patient management, organization, or reporting data): S.A.S.

Analysis/interpretation (responsible for statistical analysis, evaluation, and presentation of the results): S.A.S.

Literature search (performed the literature search): S.A.S.

Writing (responsible for writing a substantive part of the manuscript): S.A.S.

Critical review (revised manuscript for intellectual content, this does not relate to spelling and grammar checking): S.A.S.

References

- 1.Smith O. Clarinda Herald. In: Faulkner T. The Chiropractor's Protégé: The Untold Story of Oakley G. Smith's Journey with D.D. Palmer in Chiropractic's Founding Years. Association for the History of Chiropractic; Rock Island, IL: 2017. Advertisement; p. 72. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nelson C. The subluxation question. J Chiropr Humanit. 1997;7:46–55. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haavik-Taylor H, Holt K, Murphy B. Exploring the neuromodulatory effects of vertebral subluxation. Chiropr J Aust. 2010;40:37–44. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Triano J, Goertz C, Weeks J. Chiropractic in North America: toward a strategic plan for professional renewal—outcomes from the 2006 chiropractic strategic planning conference. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2010;33(5):395–405. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.SOFEC . Societe Franco-Europeenne de Chiropaxic. 2015. Clinical and professional chiropractic education: a policy statement. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ebrall P. Commentary: is EBM damaging the social conscience of chiropractic? Chiropr J Aust. 2016;44(3):203–213. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Association of Chiropractic Colleges The ACC chiropractic paradigm. 1996. http://www.chirocolleges.org/resources/chiropractic-paradigm-scope-practice/ Available at:

- 8.Rubicon Our mission. http://www.therubicongroup.org/#/about-us/ Available at:

- 9.Chiropractic Australia Policy statement: vertebral subluxation complex. https://chiropracticaustralia.org.au/wp-content/uploads/Policies/Vertebral-Subluxation-Complex-Policy.pdf Available at:

- 10.McDonald W, Durkin K, Pfefer M. How chiropractors think and practice: the survey of North American chiropractors. Semin Integr Med. 2004;2(3):92–98. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Christensen MG. Practice Analysis of Chiropractic 2010: A Project Report, Survey Analysis, and Summary of the Practice of Chiropractic within the United States. National Board of Chiropractic Examiners; Greeley, CO: 2010. Chapter 6: Overview of survey responses. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Institute for Alternative Futures. Chiropractic 2025: Divergent Futures. http://www.altfutures.org/pubs/chiropracticfutures/IAF-Chiropractic2025.pdf Available at:

- 13.Gliedt J, Hawk C, Anderson M. Chiropractic identity, role and future: a survey of North American chiropractic students. Chiropr Man Therap. 2015;23(1):4. doi: 10.1186/s12998-014-0048-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park Inn at Heathrow Airport; London, England: March 11-13, 2016. The Rubicon Conference. [Google Scholar]

- 15.12th Annual International Research and Philosophy Symposium. Sherman College of Chiropractic Spartanburg; Spartanburg, SC: October 9-11, 2015. Subluxation: more than just a historical term. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Srbely J, Vernon H, Lee D, Polgar M. Immediate effects of spinal manipulative therapy on regional antinociceptive effects in myofascial tissues in healthy young adults. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2013;36(6):333–341. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2013.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Song X, Gan Q, Cao J, Wang Z, Rupert R. Spinal manipulation reduces pain and hyperalgesia after lumbar intervertebral foramen inflammation in the rat. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2006;29(1):5–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Teodorczyk-Injeyan J, Injeyan HS, Ruegg R. Spinal manipulative therapy reduces inflammatory cytokines but not substance P production in normal subjects. J Manip Physiol Ther. 2006;29(1):14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Owens E, Hart J, Donofrio J, Haralambous J, Mierzejewski E. Paraspinal skin temperature patterns: an interexaminer and intraexaminer reliability study. J Manip Physiol Ther. 2004;27(3):155–159. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2003.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Owens E. Chiropractic subluxation assessment: what the research tells us. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2002;46(4):215. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rutherford L. Health Education Publishing Corp; Eugene, OR: 1989. The Role of Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gatterman M. 2nd ed. Mosby; St. Louis, MO: 2005. Foundations of Chiropractic Subluxation. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruch W. Life West Press; Boca Raton, FL: 2014. Atlas of Common Subluxations of the Human Spine and Pelvis. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eriksen K. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Baltimore, MD: 2004. Upper Cervical Subluxation Complex: A Review of the Chiropractic and Medical Literature. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gatterman M, Hansen D. Development of chiropractic nomenclature through consensus. J Manip Physiol Ther. 1994;17(5):302–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perle S. New York State Chiropractic Association Newsletter. August 2012. Foundation for Anachronistic Chiropractic Pseudo-Religion; p. 11. [Google Scholar]

- 27.McGregor M, Puhl A, Reinhart C, Injeyan H, Soave D. Differentiating intraprofessional attitudes toward paradigms in health care delivery among chiropractic factions: results from a randomly sampled survey. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2014;14(1):51. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-14-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lerner C. Palmer College Archives; Davenport, IA: 1952. The Lerner Report. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rehm W. Legally defensible: chiropractic in the courtroom and after, 1907. Chiropr Hist. 1986;6:51–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Charlton K. Approaches to the demonstration of vertebral subluxation: 1. Introduction and manual diagnosis: a review. J Aust Chiropr Assoc. 1988;18(1):9–13. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keating J. Science and politics and the subluxation. Am J Chiropr Med. 1988;1(3):107–110. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Texas A&M University Commerce College of Humanities, Social Sciences & Arts: Faculty and Staff. http://www.tamuc.edu/academics/colleges/humanitiesSocialSciencesArts/departments/sociologyCriminalJustice/Faculty%20and%20Staff/villanueva-RussellYvonne.aspx Available at:

- 33.Villanueva-Russell Y. Caught in the crosshairs: identity and cultural authority within chiropractic. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72(11):1826–1837. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Keating J, Charton K, Grod J, Perle S, Sikorski D, Winterstein J. Subluxation: dogma or science. Chiropr Osteopat. 2005;13(17) doi: 10.1186/1746-1340-13-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murphy D, Schneider M, Seaman D, Perle S, Nelson C. How can chiropractic become a respected mainstream profession? The example of podiatry. Chiropr Osteopath. 2008;16(10) doi: 10.1186/1746-1340-16-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mirtz T, Morgan L, Wyatt L, Greene L. An epidemiological examination of the subluxation construct using Hill’s criteria of causation. Chiropr Osteopat. 2009;17(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1746-1340-17-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kent C. Models of vertebral subluxation: a review. J Vert Sublux Res. 1995;1(1):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cooperstein R, Gleberzon B. Churchill Livingstone; Philadelphia, PA: 2004. Technique Systems in Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Senzon S. Chiropractic professionalism and accreditation: an exploration of conflicting worldviews through the lens of developmental structuralism. J Chiropr Humanit. 2014;21(1):25–48. doi: 10.1016/j.echu.2014.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Keating J, Callender A, Cleveland C. Association for the History of Chiropractic; Davenport, IA: 1998. A History of Chiropractic Education in North America. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Villaneuva-Russell Y. Graduate School, University of Missouri; Columbia, MO: 2002. On the Margins of the System of Professions: Entrepreneurialism and Professionalism as Forces Upon and Within Chiropractic [Dissertation] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Burtch C. How old is chiropractic. Backbone. 1903;1(2):43–45. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bovine G. The Bohemian thrust: Frank Dvorsky, the Bohemian “napravit” bonesetter. Chiropr Hist. 2011;31(1):39–46. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smith O, Langworthy S, Paxson M. American School of Chiropractic; Cedar Rapids, IA: 1906. A Textbook of Modernized Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gregory A. Self-published; Oklahoma City, OK: 1910. Spinal Adjustment: An Auxillary Method of Treatment. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Forster A. National School of Chiropractic; Chicago, IL: 1915. Principles and Practice of Spinal Adjustment. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bovine G. D.D. Palmer’s adjustive technique for the posterior apical prominence: “hit the high places”. Chiropr Hist. 2014;34(1):7–19. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Palmer DD. The Burlington Daily Hawkey: Sunday Morning. October 1887. Cured by magnetism; p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Palmer DD. Advertiser. The Chiropractic. January 1897 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Peters R. Integral Altitude; Asheville, NC: 2014. An Early History of Chiropractic: The Palmers and Australia. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kent C. Foundation for Vertical Subluxation; 2010. An analysis of the General Chiropractic Council’s policy on claims made for the vertebral subluxation complex; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Palmer DD. Portland Printing House; Portland, OR: 1910. The Science, Art, and Philosophy of Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Palmer BJ. Vol. 18. Palmer School of Chiropractic; Davenport, IA: 1934. The Subluxation Specific the Adjustment Specific. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Drain J. Standard Print Company; San Antonio, TX: 1949. Man Tomorrow. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Homewood AE. Earl Homewood; Ontario, Canada: 1962. The Neurodynamics of the Vertebral Subluxation. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ratledge T. Ratledge; Los Angeles, CA: 1949. The Philosophy of Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Howard J. National School of Chiropractic; Chicago, IL: 1912. Encyclopedia of Chiropractic (The Howard System) [Google Scholar]

- 58.Forster A. 3rd ed. The National Publishing Association; Chicago, IL: 1923. Principles and Practice of Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Phillips R. R. Phillips; Los Angeles, CA: 2006. Joseph Janse: The Apostle of Chiropractic Education. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bittner H, Harper W, Homewood A, Janse J, Weiant C. Chiropractic of today. ACA J Chiropr. 1973;10(11) VII(S81-88) [Google Scholar]

- 61.Firth J. Vol. 7. Palmer College of Chiropractic; Davenport, IA: 1914. Chiropractic Symptomatology. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Logan H. Logan; St. Louis, MO: 1950. Logan Basic Methods. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cleveland C. C.S. Cleveland; Kansas City, MO: 1951. Chiropractic Symptomatology Outline. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Janse J, Houser RH, Wells BF. National College of Chiropractic; Chicago, IL: 1947. Chiropractic Principles and Technic: For Use by Students and Practitioners. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Harper W. WD Harper; San Antonio, TX: 1964. Anything Can Cause Anything: A Correlation of Dr. Daniel David Palmer’s Priniciples of Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Palmer DD, Palmer BJ. Vol. 1. The Palmer School of Chiropractic; Davenport, IA: 1906. The Science of Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Loban J. 2nd ed. Universal Chiropractic College; Davenport, IA: 1915. Technic and Practice of Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Carver W. 2nd ed. Carver Chiropractic College; Oklahoma City, OK: 1909. Carver’s Chiropractic Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Verner J. 8th ed. Dr. P.J. Cerasoli; Brooklyn, NY: 1956. The Science and Logic of Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Haldeman S, Hammerich K. The evolution of neurology and the concept of chiropractic. ACA J Chiropr. 1973;VII:S-57. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Watkins RJ. Anthropology in reflex technics. Natl Chiropr J. 1948;XVIII:14–15. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sato A. The somatosympathetic reflexes: their physiological clinical significance. In: Goldstein M, editor. The Research Status of Spinal Manipulative Therapy: A Workshop Held at the National Institutes of Health, February 2-4, 1975. vol. 15. U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare; Bethesda, MD: 1975. pp. 163–172. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Phillips R. The irritable reflex mechanism. ACA J Chiropr. 1975;VIII:S-9. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Palmer BJ. Vol. 25. Palmer School of Chiropractic; Davenport, IA: 1951. Clinical Controlled Chiropractic Research. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Harper W. WD Harper; San Antonio, TX: 1974. Anything Can Cause Anything: A Correlation of Dr. Daniel David Palmer's Priniciples of Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Peterson A, Watkins RJ, Himes H, College CMC . Canadian Memorial Chiropractic College; New York, ON: 1965. Segmental Neuropathy: The First Evidence of Developing Pathology. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Weiant C. Chiropractic Institute; New York, NY: 1958. Medicine and Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 78.McGregor-Triano M. The University of Texas at Dallas; Dallas, TX: 2006. Jurisdictional Control of Conservative Spine Care: Chiropractic Versus Medicine [dissertation] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wardwell W. Mosby; St. Louis, MO: 1992. Chiropractic: History and Evolution of a New Profession. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wardwell WI. A marginal professional role: the chiropractor. Soc Forces. 1952;30(3):339–348. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Peters R, Chance M. Disasters, discoveries, developments, and distinction: the year that was 1907. Chiropr J Aust. 2007;37:145–156. [Google Scholar]

- 82.La Cross Argus. August 18, 1907. Morikubo’s Case. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Palmer DD. Letter to the editor. Religio-Philos J. 1872;12(16):6. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Palmer DD. The Burlington Daily Hawkeye: Sunday Morning. October 9, 1887. Cured by magnetism. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Palmer DD. Letter to B.J. Palmer; April 27, 1902. In: Faulkner T, editor. The Chiropractor's Protégé: The Untold Story of Oakley G. Smith's Journey with D.D. Palmer in Chiropractic's Founding Years. Association for the History of Chiropractic; Rock Island, IL: 2017. p. 103. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Palmer DD. The Davenport Times. June 14, 1902. Is chiropractic an experiment? [Google Scholar]

- 87.Palmer DD. Palmer Infirmary and Chiropractic Institute; 1903. Innate Intelligence. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Palmer DD. Letter to B.J. Palmer; April 17, 1902. In: Faulkner T, editor. The Chiropractor's Protégé: The Untold Story of Oakley G. Smith's Journey with D.D. Palmer in Chiropractic's Founding Years. Association for the History of Chiropractic; Rock Island, IL: 2017. pp. 95–96. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Palmer DD. Be honest with yourself. Chiropractor. 1905;1(3):25. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Smith O. Self-published; Chicago, IL: 1932. Naprapathic Genetics: Being a Study of the Origin and Development of Naprathy. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Faulkner T. Association for the History of Chiropractic; Rock Island, IL: 2017. The Chiropractor's Protégé: The Untold Story of Oakley G. Smith’s Journey with D.D. Palmer in Chiropractic’s Founding Years. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Keating J. Association for the History of Chiropractic; Davenport, IA: 1997. B.J. of Davenport: The Early Years of Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wolfe J. International Research and Philosophy Symposium. Sherman College; Spartanburg, SC: 2014. Historical Misconceptions: Who really convinced a jury that the chiropractic vertebral subluxation is distinct from the osteopathic spinal lesion. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Gibbons R. Solon Massey Langworthy: keeper of the flame during the “lost years” of chiropractic. Chiropr Hist. 1981;1(1):15–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Rehm W. A necrology. In: Dzaman F, editor. Who’s Who in Chiropractic, International. 2nd ed. Who’s Who in Chiropractic International Publishing Co; Littleton, CO: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Gibbons R. A moment of silence for Dr. William Rehm. Chiropr Hist. 2002;22(1):5–8. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Keating J. Rationalism and empiricism vs. the philosophy of science in chiropractic. Chiropr Hist. 1990;10(2):23–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Trafecanty T, Mostashari M, Green B. Tom Morris: chiropractic advocate and friend of drugless healers. Chiropr Hist. 1994;14(1):36. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Editor Instructions for authors. Chiropr Hist. 1997-2008:17–28. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Donahue J. Metaphysics, rationality and science. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1994;17(1):54–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Keating J. Beyond the theosophy of chiropractic. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1989;12:147–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Keating J, Mootz R. The influence of political medicine on chiropractic dogma: implications for scientific development. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1989;12(5):393–397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Keating J. The evolution of Palmer’s metaphors and hypotheses. Philos Constr Chiropr Prof. 1992;2(1):9–19. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Keating J, Rehm W. The origins and early history of the National Chiropractic Association. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 1993;37(1):27–51. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Moore S. Johns Hopkins University Press; Baltimore, MD: 1993. Chiropractic in America: The History of a Medical Alternative. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Troyanovich S, Troyanovich J. Chiropractic and type O (organic) disorders: historical development and current thought. Chiropr Hist. 2012;32(1):59–72. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Keating J, Troyanovich S. Wisconsin versus chiropractic: the trials at LaCrosse and the birth of a chiropractic champion. Chiropr Hist. 2005;25(1):37–45. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Leach R. 3rd ed. Williams and Wilkins; Baltimore, MD: 1994. The Chiropractic Theories: A Textbook of Scientific Research. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wardwell W. Chiropractic “philosophy”. J Chiropr Humanit. 1994;3:3–8. [Google Scholar]

- 110.Sagan C, Druyan A. Random House; New York, NY: 1995. The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Keating J, Green B, Johnson C. “Research” and “science” in the first half of the chiropractic century. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1995;18(6):357–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Martin S. “The only true scientific method of healing”: Chiropractic and American science. Isis. 1994;85(2):207–227. doi: 10.1086/356807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Villanueva-Russell Y. An ideal-typical development of chiropractic, 1895-1961: pursuing professional ends through entrepreneurial means. Soc Theory Health. 2008;6:250–272. [Google Scholar]

- 114.Moore J. Reflections on healing, orthodoxy, and a new direction for chiropractic history. Chiropr Hist. 2009;29(1):55–65. [Google Scholar]

- 115.Munzinger M. In pursuit of the past: the hazardous path to historical relevance. Chiropr Hist. 2009;29(1):47–53. [Google Scholar]

- 116.Rosner A. Chiropractic identity: a neurological, professional, and political assessment. J Chiropr Humanit. 2016;23(1):35–45. doi: 10.1016/j.echu.2016.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Leach R. 4th ed. Williams and Wilkins; Baltimore, MD: 1986. The Chiropractic Theories: A Textbook of Scientific Research. [Google Scholar]

- 118.Walton S. The Institute Chiropractic; Asheville, NC: 2017. The Complete Chiropractor: RJ Watkins, DC, PhC, FICC, DACBR. [Google Scholar]

- 119.Palmer BJ. Vol. 2. The Palmer School of Chiropractic; Davenport, IA: 1907. The Science of Chiropractic: Eleven Physiological Lectures. [Google Scholar]

- 120.Palmer BJ. Vol. 3. Palmer College; Davenport, IA: 1911. The Philosophy and Principles of Chiropractic Adjustments: A Series of Thirty Eight Lectures. [Google Scholar]

- 121.Owens E. Chiropractic subluxation assessment: what the research tells us. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2002;46(4):215–220. [Google Scholar]

- 122.Coulter I. Chiropractic observed: thirty years of changing sociological perspectives. Chiropr Hist. 1982;3(1):43–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Villanueva-Russell Y. Evidence-based medicine and its implications for the profession of chiropractic. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60:545–561. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Rosner A. Evidence-based medicine: revisiting the pyramid of priorities. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2012;16(1):42–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Senzon S. Constructing a philosophy of chiropractic I: an integral map of the territory. J Chiropr Humanit. 2010;17(17):6–21. doi: 10.1016/j.echu.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Draper B, Richards D. Commentary: clinical uncertainty. Chiropr J Aust. 2013;43(3):99. [Google Scholar]

- 127.Kligler B, Weeks J. Finding a common language: resolving the town and gown tension in moving toward evidence-informed practice. Explore (NY) 2014;10(5):275–277. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2014.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Ooi SL, Rae J, Pak SC. Implementation of evidence-based practice: a naturopath perspective. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2016;22:24–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2015.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Schneider MJ, Evans R, Haas M. US chiropractors’ attitudes, skills and use of evidence-based practice: a cross-sectional national survey. Chiropr Man Therap. 2015;23(1):16. doi: 10.1186/s12998-015-0060-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Haas M, Leo M, Peterson D, LeFebvre R, Vavrek D. Evaluation of the effects of an evidence-based practice curriculum on knowledge, attitudes, and self-assessed skills and behaviors in chiropractic students. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2012;35(9):701–709. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2012.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Schneider M, Evans R, Haas M. The effectiveness and feasibility of an online educational program for improving evidence-based practice literacy: an exploratory randomized study of US chiropractors. Chiropr Man Therap. 2016;24(1):27. doi: 10.1186/s12998-016-0109-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Long CR, Ackerman DL, Hammerschlag R. Faculty development initiatives to advance research literacy and evidence-based practice at CAM academic institutions. J Altern Complement Med. 2014;20(7):563–570. doi: 10.1089/acm.2013.0385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Evans R, Maiers M, Delagran L, Kreitzer MJ, Sierpina V. Evidence informed practice as the catalyst for culture change in CAM. Explore (NY) 2012;8(1):68. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Villanueva-Russell Y. In whose interest does evidence-based practice operate. Illuminate. 2011;4:1. [Google Scholar]

- 135.Kaptchuk TJ, Miller FG. What is the best and most ethical model for the relationship between mainstream and alternative medicine: opposition, integration, or pluralism? Acad Med. 2005;80(3):286–290. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200503000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Anderson BJ, Kligler B, Cohen HW, Marantz PR. Survey of chinese medicine students to determine research and evidence-based medicine perspectives at pacific college of oriental medicine. Explore (NY) 2016;12(5):366–374. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2016.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Humphries B. What else counts as evidence in evidence-based social work? Soc Work Educ. 2003;22(1):81–91. [Google Scholar]

- 138.Triano J. The functional spinal lesion: an evidence-based model of subluxation. Top Clin Chiropr. 2001;8(1):16–29. [Google Scholar]

- 139.Hampton JR. Evidence-based medicine, opinion-based medicine, and real-world medicine. Perspect Biol Med. 2002;45(4):549–568. doi: 10.1353/pbm.2002.0070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Bishop FL, Holmes MM. Mixed methods in CAM research: a systematic review of studies published in 2012. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/187365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Koch D. Has vitalism been a help or a hindrance to the science and art of chiropractic? J Chiropr Humanit. 1997;6:18–22. [Google Scholar]

- 142.Senzon S. Causation related to self-organization and health related quality of life expression based on the vertebral subluxation model, the philosophy of chiropractic, and the new biology. J Vert Sublux Res. 1999;3:104–112. [Google Scholar]

- 143.Gelardi T. The science of identifying professions as applied to chiropractic. J Chiropr Humanit. 1996;6:11–17. [Google Scholar]

- 144.Owens E, Koch D, Moore L. Hypothesis formulation for scientific investigation of vertebral subluxation. J Vert Sublux Res. 1999;3:98–103. [Google Scholar]

- 145.Owens E, Pennacchio V. Operational definitions of vertebral subluxation: a case study. Top Clin Chiropr. 2001;8(1):40–49. [Google Scholar]

- 146.Strauss J. Foundation for the Advancement of Chiropractic Education; Levittown, PA: 1994. Refined by Fire: The Evolution of Straight Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 147.Watkins RJ. Subluxation terminology since 1746. J Am Chiropr Assoc. 1968. In: Walton S, editor. The Complete Chiropractor: RJ Watkins, DC, PhC, FICC, DACBR. The Institute Chiropractic; Asheville, NC: 2017. pp. 271–279. [Google Scholar]

- 148.Howe J. A contemporary perspective on chiropractic and the concept of subluxation. ACA J Chiropr. 1976;X:S-165. [Google Scholar]

- 149.Senzon S. An integral approach to unifying the philosophy of chiropractic: B.J. Palmer’s model of consciousness. J Vert Sublux Res. 2000;4(1):43–50. [Google Scholar]

- 150.Senzon S. Constructing a philosophy of chiropractic: when worldviews evolve and postmodern core. J Chiropr Humanit. 2011;18(1):39–63. doi: 10.1016/j.echu.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Muller RO. The Chiro Publishing Company; Toronto, Canada: 1954. Autonomics in Chiropractic: The Control of Autonomic Imbalance. [Google Scholar]

- 152.Gillet H. The evolution of a chiropractor. Natl Chiropr J. November 1945 [Google Scholar]

- 153.Faye LJ. Motion Palpation Institute; Huntingtion Beach, CA: 1983. Motion Palpation of the Spine. [Google Scholar]

- 154.Peters D. Proceedings of the World Federation of Chiropractic Conference on Philosophy in Chiropractic Education. Nov 11-12, 2000. Vitalism and chiropractic. Fort Lauderdale, FL. [Google Scholar]

- 155.Senzon S. What is life? J Vert Sublux Res. 2003;13:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 156.Keating J. Chiropractic: science & anti-science & pseudo-science, side by side. Skeptical Inquirer. 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 157.Faye L. The subluxation complex. J Chiropr Humanit. 1999;9:28–31. [Google Scholar]

- 158.Stiga J, Flesia J. Renaissance International; S.A.: 1982. The “Vertebral Subluxation Complex”. [Google Scholar]

- 159.Dishman R. Review of the literature supporting a scientific basis for the chiropractic subluxation complex. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1985;8(3):163–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Palmer DD. Press of Beacon Light Printing Company; Los Angeles, CA: 1914. The Chiropractor. [Google Scholar]