Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this paper is to review and discuss the history of chiropractic vertebral subluxation (CVS) in the chiropractic profession between the years 1897 and 1907.

Discussion

The first theories in chiropractic were developed by pioneers such as D. D. Palmer; his students, such as A. P. Davis, Oakley Smith, and Solon Langworthy; and his son B. J. Palmer. Their thoughts on CVS established foundational theories for the profession. D. D. Palmer posited his initial concept of CVS as an articular disrelationship between vertebrae causing pressure and impingement on nerves leading to too much or too little function. Palmer’s students developed additional theories.

Conclusion

From the first years of CVS, there was a diversity of theories, practices, and scientific rationale. This account of the early theories may offer insights into the historical literature.

Key indexing terms: Chiropractic, History

Introduction

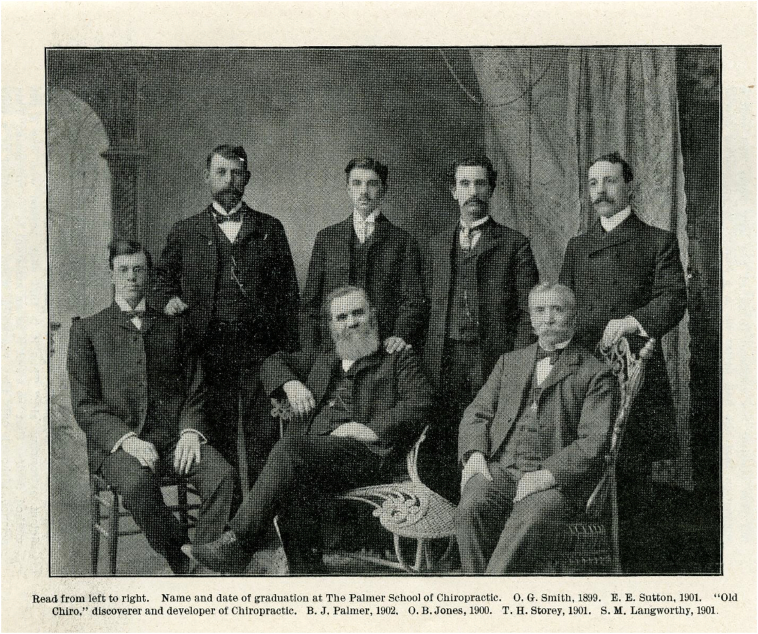

Several theories about the chiropractic vertebral subluxation (CVS) emerged during the early years of the chiropractic profession. D. D. Palmer, the founder of chiropractic, and his early students, including Andrew P. Davis, Oakley Smith, and Solon Langworthy, and his son B. J. Palmer, published the first books on the topic. Their thoughts on chiropractic and CVS established foundational theories of the profession (Fig 1).

Fig 1.

Some of D. D. Palmer’s first students.

Authors of chiropractic history have attempted to piece together early chiropractic literature on the topic of CVS. However, some of these writings may contain historical errors, especially for materials described from 1902 to 1907. Errors may have a bearing on modern day literature that analyzes the CVS1, 2, 3 or on contemporary papers that cite older materials.4, 5, 6 Since the publication of some of these histories, additional sources have become available and may help fill in gaps in the literature or update the historical record of the chiropractic profession and its theories with new discoveries, and, perhaps, greater accuracy.

A more accurate historical record of CVS between the years 1897 and 1907 may develop better-informed positions about the history of CVS theory and foster a more objective foundation for discourse and analysis. History is composed of events interpreted through the perspectives of the present. The more detail conveyed, the less possibility that events and ideas of the past may be misinterpreted. It is valuable for the chiropractic profession to have the most accurate portrayal available of the history of CVS theories because they have heavily influenced the profession since 1902.7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12

Therefore the purpose of this article is to provide a history of the CVS during the years 1897 to 1907 and to offer and appraise scholarly historical literature with an attempt to correct potential errors in previously published papers.

Discussion

D. D. Palmer’s first chiropractic students graduated in 1898.13 Between 1902 and 1907, several of his students developed and described CVS in their lectures and writings, including B. J. Palmer,14 Andrew P. Davis,15 O. G. Smith,16 and S. L. Langworthy.17 The theories of these pioneers shaped the discourse for the future of the profession.

The early students of D. D. Palmer are mentioned in the literature; however, their ideas are rarely described in the context of CVS history. Smith, Langworthy, and Paxson’s Modernized Chiropractic is probably the most well-known writing of these students.18, 19, 20 This book emphasized the axis motion between vertebra and the effect on the ligaments of the intervertebral foramina and discs.17 Davis’ approach to chiropractic has limited mention in the literature and yet it influenced several early theories.15, 21, 22, 23 B. J. Palmer’s 1907 text contains descriptions of his early theories. Although B. J.’s text was influential in later theory, it is also not well described in the literature.14 These authors’ foundational CVS theories are worth revisiting to more fully describe historical ideas in the chiropractic profession.

The First Use of the Term Subluxation

The first published use of the term subluxation in the chiropractic profession is claimed to be an advertisement by O. G. Smith in the Clarinda Herald on February 4, 1902,24 and his first use of intervertebral foramina (IVF) related to chiropractic in April 1902.16 Smith was an 1899 graduate of D. D. Palmer’s school13 and may have read a case report from 1901 in the Journal of Osteopathy where an osteopath used the term or a synonym of it.16, 25 Smith may have been a student of D. D. Palmer for a longer period than any other student because he studied with Palmer in Iowa starting in 1898 and later in California and Chicago in 1904.16, 26

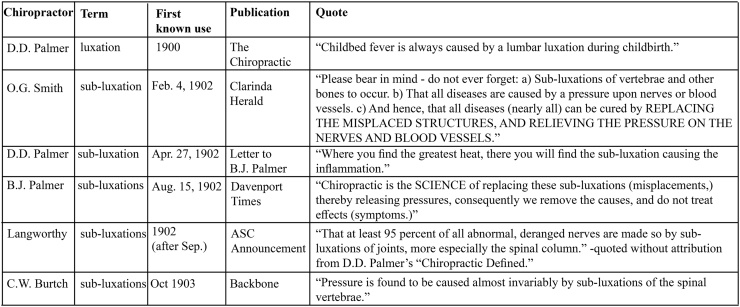

Another unreported use was by D. D. Palmer. In a letter to his son dated April 27, 1902, he used “sub-luxation.”7 B. J. Palmer started using sub-luxation in August 1902.16, 27 Thus it seems that the first use of the terms subluxation and IVF by chiropractic authors was not by Solon Langworthy or his student C. W. Burtch, as has been previously supposed.4, 28 Another early use of sub-luxation by Langworthy was in the July 1902 announcement for his new American School of Chiropractic and Nature Cure,16, 29 which may be part of an unattributed quote from an advertisement of D. D. Palmer’s dated June 14, 1902.30 Fig 2 shows the first known uses of the terms luxation and subluxation by chiropractic authors.

Fig 2.

Early usages of subluxation in the chiropractic profession.

D. D. Palmer’s Theories

D. D. Palmer’s writings on healing and his philosophical approaches to “disease” and “dis-ease” date back to 1886 and 1887.31, 32 In 1887 he wrote, “dis-ease is a condition of not ease, lack of ease.”32 This concept became central to Palmer’s chiropractic paradigm. As early as 1897, D. D. Palmer proposed his first theories about chiropractic.33 He suggested that nerves could be stretched, strained, or pinched; that vessels could be compressed; and that taking the strain off of nerves was of vital importance.33 He writes, “I often find an injury in some part of the human frame caused by a fall, a strain or shock, a partial dislocation or some nerve unduly strained, stretched, pinched, or something wrong which must be righted.”33 He also recommended annual chiropractic checkups.34

As early as 1900, D. D. Palmer described his “philosophy of treatment” or, “… philosophy of our method of treating diseases of all kinds.”35 This was related to his nerve tracing methodology. Palmer would later propose that the term treatment did not convey his nontherapeutic approach.36 D. D. Palmer’s first substantive writings on chiropractic came in 1902, the year he started using the term luxations to describe a cause of dis-ease.37 Palmer described how the spinous processes were used as handles or levers. He wrote of spinal nerves, foramina, and nerve irritation and focused on nerve pressure and the art of chiropractic. He wrote that by relieving pressure, nature or innate intelligence could perform normal functions.30, 38 Palmer hypothesized that luxations led to interference with function.38 The concept of interference to transmission of the nerve signal was probably introduced by his son B. J. Palmer.14 D. D. Palmer wrote years later that transmission of motion and sensation impulses could be disarranged by displacements.39

By 1903 D. D. Palmer hypothesized that 95% of all diseases were from luxations, which caused deranged nerves.38 Palmer purported that when nerves were free to act naturally, the life force would be normal and unobstructed and the body would be free of pain, aches, and symptoms.38 Also in 1903, D. D. Palmer more fully developed his concepts of innate intelligence, subluxation, and abnormal function.38 He suggested that innate intelligence controlled the vital functions of the body and that it operated through the nerves. Palmer proposed his hypothesis that subluxated vertebra caused pinched nerves, which led to abnormal functions, which were either excess function or insufficient.38

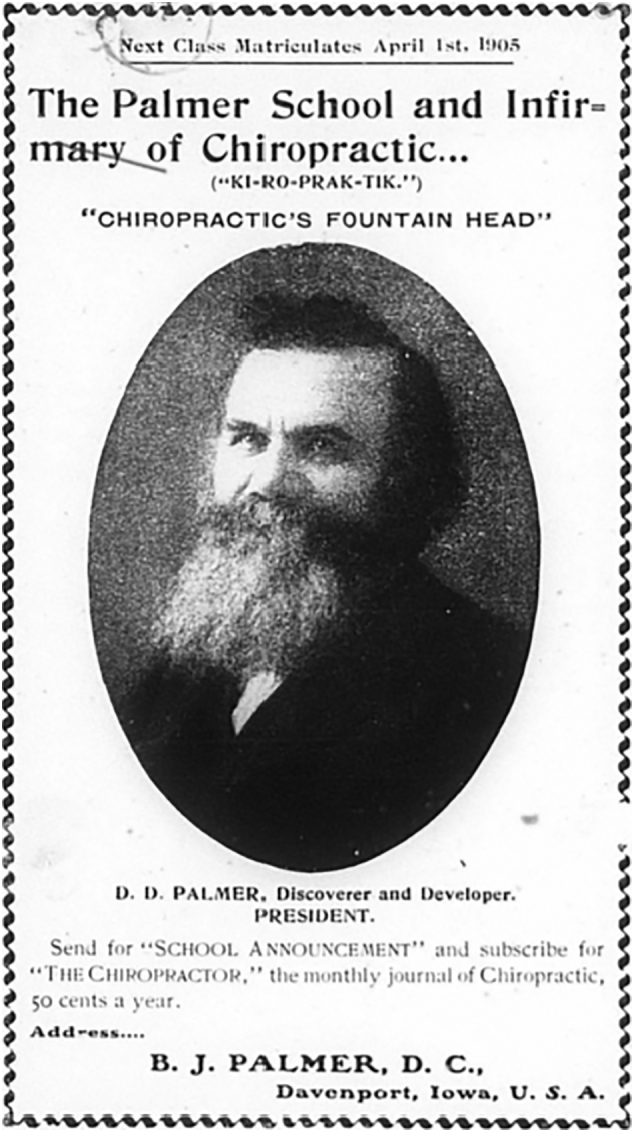

Between 1904 and 1906, D. D. Palmer elaborated on his theories and developed his practice. His theories were based on his studies and clinical observations.13, 40 During this time, he was living in Davenport, Iowa, teaching students, running a clinic, and writing monthly articles in The Chiropractor (Fig 3).13 In February 1906, D. D. and B. J. Palmer advertised that a book was being created (Fig 4).41 Several months after this advertisement, B. J. Palmer took over the school in the spring of 190613 and published the book The Science of Chiropractic later that fall.42 The Science of Chiropractic included D. D. Palmer’s articles along with other essays from The Chiropractor.42, 43, 44, 45 In this collection of writings, D. D. Palmer suggested that the principles of chiropractic were founded on anatomy, pathology, physiology, and nerve tracing, which, along with observation and palpation, were his methods of analysis.42 He also proposed that CVS could occur throughout an individual’s lifespan and that it related not only to physiological but also to psychological disease processes. His claim was that the cause of disease was an intelligible and disordered condition in the body caused by the material derangement of nerves.42

Fig 3.

Palmer’s advertisement for the school in 1905. (Courtesy Special Services, Palmer College of Chiropractic.)

Fig 4.

Palmer’s advertisement for the first chiropractic textbook in February 1906. (Courtesy Special Services, Palmer College of Chiropractic.)

In 1904 D. D. Palmer postulated that subluxated vertebrae affected the nerves and caused pressure because the nerves were pinched at the foramen.43 By 1909 he used impingement rather than pinched, and claimed that was what he meant all along.46 According to Palmer, pinched, as it was being used by other chiropractors, was incorrect. He felt that pinched referred to pressure on both sides of a nerve, causing a blockage, whereas impinged referred to the nerve being pressed on from one side or stretched and modified, instead of being blocked.47

The phrase “bone out of place” has sometimes been attributed to D. D. Palmer; however, this may be an inaccurate depiction of his view. It is possible this led to misinterpretations of D. D. Palmer’s definition of CVS by limiting his theory to one that is a bone out of place.48, 49, 50, 51 As early as 1905, D. D. Palmer described a “chiropractic luxation” as “a partial separation of two articular surfaces.”52 In 1906 he wrote of “sub-luxation known to the Chiropractor as a displacement of the articular processes,” and “a chiropractic luxation being a partial dislocation, or what we are pleased to term sub-luxations.”42 In 1910 he wrote that a subluxation was “a displacement of two or more bones whose articular surfaces have lost, wholly or in part, their natural connection.”36 He also wrote that “sub-luxation is a partial or incomplete separation; one in which the articulating surfaces remain in partial contact,” and that “a sub-luxation consists of two or more bones, whose articular surfaces have lost in part their natural connection—one in which the articulating surfaces remain in partial contact—those which partly preserve their connection.”36 This is further evidence that D. D. Palmer felt that CVS was associated with a joint, not one isolated bone.

D. D. Palmer wrote an article in February 1906 distinguishing the difference between the “osteopathic lesion” and the chiropractic subluxation.44 He wrote, “The lesion theory of the Osteopaths, is not that of sub-luxation of the Chiropractor.”44 He viewed the lesion as an effect and sub-luxation as a cause. He also suggested that lesion was a general term and that it could mean anything, which made it useless when trying to convey his definition of CVS. This article was republished in The Science of Chiropractic in 1906.42 Other articles by D. D. Palmer highlighted his distinction that his CVS theory emphasized the nervous system and that osteopathic theory emphasized obstruction to the circulatory system.36

B. J. Palmer’s Theories

The earliest printed evidence of the use of subluxation by B. J. Palmer was on August 31, 1902.27 He introduced the word into advertisements based on D. D. Palmer’s articles. B. J. Palmer continued to spread use of the term through his advertising until 1904 when he became assistant editor of The Chiropractor.43 B. J. served under his father in this capacity because D. D. Palmer was the editor.13 Some of the chapters from their book appear to have been written or compiled by B. J. directly.42

Between 1906 and 1909, B. J. developed thousands of stereopticon slides for his lectures.13 After requests of a transcription of his lectures in 1906, all subsequent lectures were recorded or transcribed.14 In each lecture series he developed his CVS theories further. By 1909, B. J. claimed that his open clinic was seeing 180 to 200 patients per day.54 B. J. reportedly used these cases to refine and develop his chiropractic models. His early ideas were inspired by his lectures and the growing clinic.55

B. J. Palmer’s lectures from February and March, 1907, were copyrighted and published as The Science of Chiropractic: Eleven Physiological Lectures, volume 2.56 In this book, B. J. described the “cycle of life,”14 which was one of his most enduring contributions to CVS theory because it included his theory of interference to transmission of nerve impulses. The cycle consisted of a triune, consisting of the creation (C) of mental impulses, transmission (T) of impulses along nerves, and expression (E) of function in the tissue cell. What I refer to as the CTE cycle, includes the afferent side of the nervous system; an impression of vibrations from the environment, afferent transmission to the brain, and interpretation of the stimuli by the inherent intelligence. His theory was that the CVS was like a circuit breaker between currents. Chiropractic vertebral subluxation could interfere with the transmission or quantity and quality of impulses.14

It is possible that B. J.’s CTE cycle was inspired by his study of the French neurologist, H. P. Morat, having referenced Morat’s textbook in 1909 and for decades thereafter.54, 57 In doing so he does not credit Morat but he acknowledges the similarity in their thinking. According to B. J., both were seeking the “missing link” uniting intelligence and matter in the nervous system. B. J. claimed that his cycle of life was the first to make this link in human intellectual history.14

B. J. Palmer’s thoughts from 1906 and 1907 shaped his chiropractic theories and his self-perceived role in chiropractic for the remainder of his life.14 It was during this period that he started referring to himself as chiropractic’s “developer.” Reading B. J.’s lectures from this time makes it evident that he felt the development of the cycle of life was the reason for this new designation.14

The new self-appellation “developer” did not go unnoticed by D. D. Palmer. In January 1909, while living and teaching in Portland, Oregon, D. D. Palmer decided to trace the exact month when his son started referring to himself as the “developer” of chiropractic.58 D. D. found that by studying monthly issues of The Chiropractor, by then published by B. J. in Davenport. D. D. revealed that the first use was in an advertisement published in the August/September 1907 issue of The Chiropractor.59 The advertisement was for B. J.’s forthcoming The Philosophy and Principles of Chiropractic Adjustments: A Series of Twenty-Four Lectures, volume 3.60 D. D. was not pleased with the new designation.

In the biography of B. J. Palmer, B. J. of Davenport: The Early Years of Chiropractic, attribution for the appellation developer is suggested to be a result of marketing, family disputes, and ego.61 However, in the biography there are few quotes or analyses from B. J.’s books.61 Thus the text unfortunately does not necessarily capture the full extent to which B. J. Palmer was using the term developer. By studying transcriptions of his lectures, B. J.’s thoughts and motivations on the topic may become more apparent. My review of the first editions of B. J. Palmer’s first 5 books lead me to suggest that B. J.’s expansion about CVS was the main driver of his actions, teachings, and writings during this time and for decades thereafter.14, 54, 60, 62, 63

Other Early Palmer Graduates Theories

A. P. Davis was a 1894 graduate of A. T. Still’s school of osteopathy and an 1898 graduate of D. D. Palmer’s school (Fig 5).22 Davis developed his method of Neuropathy and published 2 books on his methods, in 1905 and 1909.15, 64 His 1905 book is the first to purport to teach chiropractic.15 Davis claimed that the neurological component of CVS was secondary to the circulatory obstruction. As such, his perspective disagreed with Palmer’s model. To Davis, the adjustment was a stimulus, which united the positive and negative forces and neutralized the acid/alkaline balance.65 D. D. Palmer strongly disagreed with Davis’ theories.36 Gaucher-Peslherbe suggested that D. D. Palmer’s inspiration to start writing journal articles and a book in 1905 was to refute Davis and define his own ideas in published works.23

Fig 5.

A. P. Davis circa 1909.

Smith, Langworthy, and Paxson’s Modernized Chiropractic was published in 1906, with Smith as the primary author, Langworthy the publisher, and Paxson the editor.17, 66 A recent historical discovery of the original handwritten manuscript of the book suggests that Smith wrote most or all of the book.16 All 3 authors earned their chiropractic degrees from D. D. Palmer in 1899, 1901, and 1903, respectively, and they were all involved with the American School of Chiropractic in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, in 1904.16 The “subluxation” was described in the text Modernized Chiropractic as an aberrant motion and not merely a misalignment of the articular surfaces.17 This concept was central to Palmer’s theory.42 The objective of the thrust in an adjustment was to change the field of motion toward the hub where it “belongs.”20 They suggested that this would lead to spontaneity and that spontaneity was a release of energy or “subtle force” in the muscles and ligaments. They theorized that this activation and arousal of the body’s inherent powers contributed to the body’s self-preservation and recuperation.17 Modernized Chiropractic used the term subluxation 1186 times.17 In contrast, the Palmers’ first book only used the term 48 times and luxation 155 times42 (Fig 6).

Fig 6.

Read from left to right with graduation year from the Palmer School of Chiropractic. O. G. Smith, 1899; E. E. Sutton, 1901; D. D. Palmer; B. J. Palmer, 1902; O. B. Jones, 1900; T. H. Storey, 1901; S. M. Langworthy, 1901. Photo taken in January 1902 and printed in The Chiropractor, vol. 1, no. 3, p. 21, 1905. (Courtesy Special Services, Palmer College of Chiropractic.)

It is proposed that Oakley Smith was the first chiropractor to write about descriptions seen in the laboratory on the CVS. Under a microscope, as early as 1905, Smith found that scar tissue and shrunken tissue of the ligaments in the intervertebral disc and foramina affected the nerves and other structures.16 This led to the founding of his own profession, which he called naprapathy. Smith reissued Modernized Chiropractic in 1932, with a new introduction and title. It was called Naprapathic Genetics.66 Smith suggested the reader substitute every instance of subluxation in the book with the term ligatite, which was a term he coined in 1905.66 Tight ligaments, he surmised, led to nerve pressure.67 Smith conducted and supported the first chiropractic anatomical research into the IVF to explore this hypothesis.68, 69 In 1913 he developed his connective tissue doctrine.67

Critical Review and Discussion of Previous Works

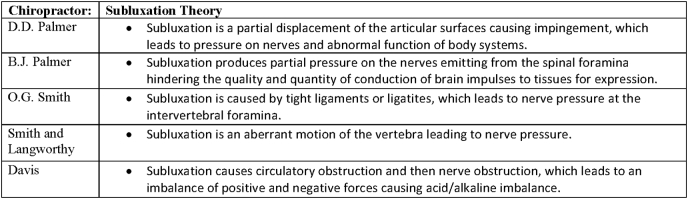

The earliest theories of chiropractic represent the foundational development of the profession’s theoretical, scientific, and philosophical rationale (Fig 7). Further analysis and an enhanced understanding of the core theories from this era may allow the modern chiropractor to more accurately interpret the literature, develop nuanced distinctions about these early ideas, and measure early theory against current insights from neurophysiology materials and other research. The following critical review explores previously published literature with an emphasis on challenging accuracy of statements and content in previously published works, updating historical timelines, and pointing out theoretical ideas that continue to be described in the literature.

Fig 7.

First subluxation theories that emerged during this time.

Assumptions in the Literature About D. D. Palmer’s Knowledge

This author posits that there should be trepidation about how previous articles may have depicted the history of ideas in early chiropractic. For example, in 2005 Nelson et al1 developed a series of “postulates” from D. D. Palmer’s theories and philosophical explanations in an attempt to offer a new rationale for the profession. In relation to D. D. Palmer’s adjustment of Harvey Lillard in 1895, they wrote1:

D.D. Palmer might state that he was trying to explain why a deaf man with a vertebral misalignment recovered his hearing following re-alignment of that vertebra. However, there is no evidence that Palmer undertook any sort of systematic exploration of the spine/health relationship following his epiphany. What we know about D.D. Palmer suggests that patient and disciplined observation was not his forte. His method of discovery was by inspiration and revelation.

However, Palmer writes of his reasoning process after comparing the Lillard case to a heart case36:

Shortly after this relief from deafness, I had a case of heart trouble which was not improving. I examined the spine and found a displaced vertebra pressing against the nerves which innervate the heart. I adjusted the vertebra and gave immediate relief—nothing “accidental” or “crude” about this. Then I began to reason if two diseases, so dissimilar as deafness heart trouble, came from impingement, a pressure on nerves, were not other disease due to a similar cause, Thus the science (knowledge) and art (adjusting) of Chiropractic were formed at that time. I then began a systematic investigation for the cause of all diseases and have been amply rewarded.

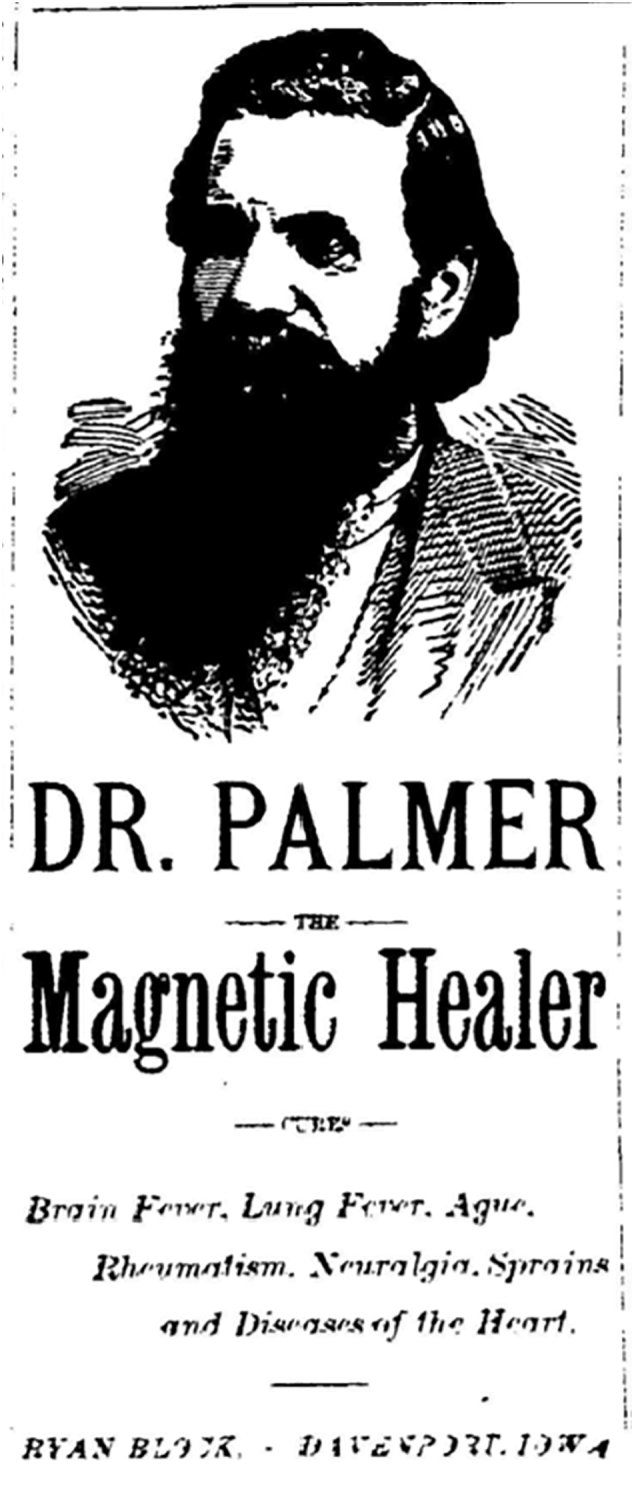

There is evidence of Palmer’s systematic exploration of the spine and health. D. D. Palmer’s earliest study of anatomy and physiology in relation to health and the spine goes back to the late 1880s and early 1890s.32, 70, 71 He wrote of obstruction to vessels in 1892.70 He cared for patients for a decade before he first adjusted Lillard.72 His patient care during those years included a systematic approach to determining locations of organ congestion through a history and presentation followed by palpation of tender spots over affected organs.73 This was an innovation on the standard magnetic healing practices of his time73 (Fig 8). Palmer then decided that the problems he had been treating were connected to the spine through nerve and circulatory pathways. This was assessed by palpation of tender nerves to the source of injury in the spine, which he termed sub-luxation.30, 33, 35, 74

Fig 8.

Advertisement in the Davenport Times, October 29, 1891.

An analysis of D. D. Palmer’s study of anatomy, physiology, and surgery textbooks up to 1910 suggests that he was at least as well read as the average medical doctor and that he cited the latest editions in addition to historical editions going back 200 years.75, 76 Photographs of his medical library and osteology collection were published in 1906.42 Palmer wrote of the effects of impingement on recurrent meningeal nerves in relation to their innervation of the meninges.36 About D. D. Palmer, Nelson et al1 state, “His method of discovery was by inspiration and revelation.” However, this does not necessarily reflect an accurate historical record.

Another fascinating and confusing element of D. D. Palmer’s studies is his claim that he received chiropractic from a spirit who was a doctor that lived 50 years earlier, named Jim Atkinson.36 D. D. Palmer seems to have made this claim in hopes of offering legal cover to chiropractors.77 One recent historical discovery suggests that he was considering such a maneuver as early as 1904.16 However, that claim does not minimize the decades of self-study and clinical practice that led to his systematic exploration of the spine, nervous system, and physiology.23, 77, 78, 79, 80 D. D. Palmer’s claim to receiving information about chiropractic from an “intelligent spiritual being” named Jim Atkinson was linked to Spiritualism,77 of which Palmer was an adherent. Years later, B. J. suggested that Spiritualism should be considered D. D. Palmer’s religion.81 D. D. Palmer believed in spirit communication and even suggested that his entire 1910 text was written as a form of “revelation.”77, 82 Considering that much of that book was written over the course of 2 years, we might consider it today a type of “flow state” writing style.83 It was common practice for Spiritualist authors of books on health topics to make claims that the information came from the spirits of doctors from other eras.84 It is possible that D. D. Palmer was modeling the approach based on one of the books in his library by Stone. Stone claimed that his book The New Gospel of Health85 was written by his spirit, which was in communion with disembodied physicians such as Sir Astley Cooper and Sir Benjamin Brodie, “who had stood at the head of their profession when in earth-life.”85 Palmer’s copy of Stone’s book was signed by him on August 6, 1888, and is in the Palmer museum. We will never accurately know why D. D. Palmer claimed to have received chiropractic from a spirit; however, it seems that Spiritualism was a guiding element in his reasoning. There can be several interpretations of these historical data.

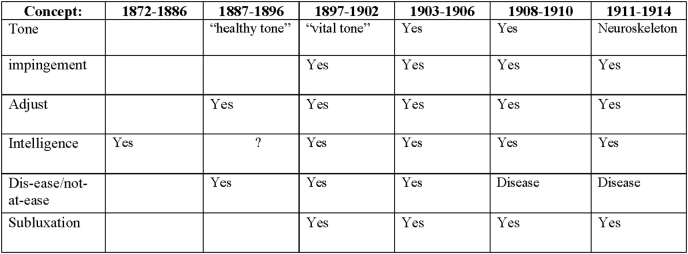

Historical scholarship about D.D. Palmer has been guided by Keating’s work on the evolution of Palmer’s ideas and by Lerner’s writing on the earliest use of philosophy and terminology in chiropractic.4, 6 Some of Keating’s research on D. D. Palmer’s early ideas was based on original documents which are in the Palmer archives.6 Keating compared those documents to quotes from Palmer’s later writings in an article on the evolution of Palmer’s ideas.6 Keating’s basic argument was that D. D. Palmer’s ideas were not static but went through 3 distinct phases of development: 1897 to 1902, 1903 to 1906, and 1908 to 1910.6 Although I feel that many of Keating’s observations from his The Evolution of Palmer's Metaphors and Hypotheses6 are valid, there are additional interpretations of Palmer’s writings.

D. D. Palmer’s writings from 1872 to 1913 are available in searchable portable document files, digital books, journals, and newspaper archives.31, 72, 86, 87, 88 From these, we can add to previous historical papers and provide additional perspectives on the topics studied by the authors of these papers. For example, Keating's paper is an excellent example because he traced several important theories of D.D. Palmer's. We can address each concept to determine what new information might be added to Keating's analysis.

Keating made the case that D. D. Palmer’s use of the term tone was first represented as “vital tone” in his 1897 writings and was present in his writings until 1902 but then absent in his writings until 1908. However, we now know that Palmer used “healthy tone” even earlier, in 1896,73 and in his 1906 book,42 where he writes, “Freeing these nerves allows them to act and innervates the vital parts; improve digestion, assimilation and the circulation, giving strength, vigor and tone to the mental and physical....” Thus gaps in on this topic can be filled in with new knowledge on this topic. Rather than tone representing distinct new ideas for Palmer during different periods and acting as a bridge between his older ideas and his newer ones,6 it was a concept that gradually developed over time. I suggest that tone came to characterize all disorders and disturbances especially related to the “neuroskeleton” or tension frame.6, 14, 23, 77

Other important concepts emphasized by Keating were impingement and nerve-stretching. Keating included little about D. D. Palmer's use of the terms impingement and nerve-stretching. Perhaps this was because materials were not available. New findings in D.D. Palmer's writing suggest Palmer's theory of nerve-stretching was developed from 1897 to 1913 and his theory of impingement was central to his theory from 1905 and features prominently in his 1906 text.74, 77, 89 Impingement, as described by D. D. Palmer in 1910, was not a new development but rather a new distinction of a theory that was in development for years.6, 36, 47 Bovine observed that Palmer's theory focused on the opening of the IVF rather than a closing of the IVF, as proposed by others such as Smith, Langworthy, and B. J. Palmer.88 Bovine's observation provides further insight, which adds to a richer understanding of D. D. Palmer's impingement theory.

Keating also suggested that B. J. Palmer and others used the terms pinched and not impinged.6 This interpretation was potentially based in part on Keating’s reading of D. D. Palmer’s vehemence against other theories.46 However, investigation of additional primary literature indicates that impingement was a term used by B. J. Palmer and many of his students for decades.14, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94, 95

Bovine observed that Palmer’s theory focused on the opening of the IVF rather than a closing of the IVF, as proposed by others such as Smith, Langworthy, and B. J. Palmer.88 Bovine’s observation provides further insight, which adds to a richer understanding of D. D. Palmer’s impingement theory. Based on materials he had access to at the time, Keating wrote that the term adjust was not used before 1903 and suggested that D. D. Palmer did not refer to “intelligence” in spiritual terms until his later writings.6 However, documents suggest that D. D. Palmer used the term adjust several times between 1897 and 1900,33, 35, 74 and his first reference to “intelligence” as spirit dates to 1872.96

Even though there are gaps in Keating's historical facts, his insights about D. D. Palmer's theories are important. Keating writes, “Ironically, much that is potentially testable in Palmer’s theories has been forgotten by chiropractors. Langworthy’s and subsequently B. J. Palmer’s metaphor of ‘pressure on the hose’ has replaced Old Dad Chiro’s belief in vibrational nerve transmission, aggravated nerve tension and altered tone.”6 Although it may be true that chiropractors today have forgotten D. D. Palmer’s theories, many CVS theorists cited D. D. Palmer and attempted to substantiate his theories.54, 97, 98, 99, 100, 101, 102, 103

Also, few historians have written about B. J. Palmer’s early theories and assessed the impact those theories had on the profession.14, 60 For example, B. J. Palmer was probably the first to use the hose metaphor to depict the compression theory.57 Also, B. J. Palmer developed his own vibrational theory of nerve transmission, which was distinct from his father’s theory.36, 54

This correction of the timeline of D. D. Palmer’s ideas is relevant and important today because earlier analysis of Palmer’s theories is well cited in the literature and published in several textbooks (Fig 9).104, 105, 106, 107, 108, 109, 110, 111, 112 For example, in an article by Perle where he cited Keating’s timeline of D. D. Palmer’s ideas,3 Perle relies, in part, on Keating’s timeline to disparage chiropractor’s use of CVS theories that originated with Palmer. Perle states, “If D. D. could change his theory three times, then why on earth would the chiropractic profession want to pick one of D. D.'s or his son's theories and etch them in stone?” I suggest that the general premise of the argument is incorrect because chiropractors considerably changed and evolved many theories that date back to D. D. Palmer’s era. Perle’s argument seems to rest on the partial timeline established by a previous publication.6

Fig 9.

D. D. Palmer’s terminology timeline.

Cyrus Lerner’s account of early chiropractic history cites interviews, which are lost to history, as well as court records and newspapers.4 Lerner wrote his report in the form of a fictional play. He embellished on facts, some of which could not be verified whereas others have been verified by historians.13, 113, 114 Lerner’s report about the early ideas in chiropractic has been extensively cited and has thus shaped the knowledge base of the profession.5, 6, 19, 48, 49, 112, 115, 116, 117, 118, 119, 120 Lerner’s report led to assumptions about early CVS theories especially in relation to the importance of Langworthy.4 Lerner proposed that “subluxation” and “intervertebral foramina” were first used and published by Langworthy in 190328 and that the text he coauthored introduced philosophy into chiropractic in 1906.17 These assumptions are likely incorrect, based on currently available historical documents.5, 7, 8, 16, 30, 121, 122, 123 Philosophy and CVS were in development before 1906, which counters Lerner’s conclusions that philosophy and CVS were invented by Langworthy and solely adopted for legal reasons.4, 5

Bone Out of Place and Lesion Concepts in the Literature

In an article in the first issue of Chiropractic History on the structural approach in chiropractic,124 Rosenthal attributed the “bone out of place” (BOOP) theory to the Palmers because they did not emphasize adjusting multiple CVSs throughout the spine as Carver did. This attribution of the BOOP theory to D. D. Palmer conflates Palmer’s analysis, adjusting method, and CVS theory. This has led to confusion in the literature because it did not emphasize Palmer’s definition of CVS in terms of the disrelationship of articulations of the joint. His analysis included a 3-finger gliding palpation coupled to nerve tracing to a particular vertebra. His adjusting method involved a thrust on the spinous processes and transverse processes on one vertebra as a lever, although he defined the “subluxation” in terms of a joint, not a bone.36, 42, 77

Chiropractic historians and theorists have cited Rosenthal’s conclusion, which I feel is in error. Moore cited Rosenthal and attributed the BOOP theory to D. D. Palmer.70 Wardwell also cited Rosenthal, attributing the BOOP theory to B. J. Palmer.48, 49 The first editions of Leach’s text on chiropractic theories attributes BOOP to D. D. Palmer without recognizing Palmer’s emphasis on the joint because Leach suggested the joint emphasis was a recent phenomenon.125, 126 Chiropractors of the 1950s and 1960s included D. D. Palmer’s models in their joint proprioception hypotheses of CVS.97, 98, 127 Differentiating CVS theory, chiropractic analysis, and adjusting method may aid us to more accurately interpret the history of this terminology in chiropractic and provide more robust materials for discussions regarding the CVS.

Another important distinction about D. D. Palmer’s theories that applies to the modern literature was his dismissal of the term lesion. Palmer felt that lesions were general and may have been caused by subluxation, but they were not synonymous. To the best of this author’s knowledge, there is no known CVS literature that refers to subluxation as a lesion and also references D. D. Palmer’s hypothesis on the topic. Authors have used lesion as a synonym for subluxation in chiropractic without referencing Palmer’s disagreement with using that term.127, 128, 129, 130 For example, “manipulable spinal lesion” was used by Schafer in the American Chiropractic Association’s 1973 CVS definition: “A manipulable spinal lesion …[has] the following characteristics: vertebral malposition, abnormal vertebral motion, lack of joint play, palpable soft tissue changes, and muscle contraction or imbalance.”131 Cooperstein and Gleberzon suggest that “adjustable lesion”132 is more appropriate for the profession because it fits better with the chiropractic paradigm. None of these authors addressed D. D. Palmer’s semantics, which defined his paradigm.133 Without reference to D. D. Palmer’s reasoning as to why lesion was not the correct term, any modern semantic approach using the term may lead to conclusions that may be out of historical context.

Different Schools of Thought

It is difficult to assess the impact of the other CVS theorists from this period. Zarbuck documented the influence of ideas from Davis’ books and Modernized Chiropractic on the works of Howard.26 The ideas of Smith, Langworthy, and Davis are also evident in the works of Gregory,134 Loban,135 Forster,136 and Carver,137 and thus chiropractors who came after them. A recent article by Coleman et al138 assessed the impact of Modernized Chiropractic on modern practice. These early texts included overlapping ideas and distinct theories.

Theorists who may not use the language of the Palmers may have been describing the same basic theories. This is an important distinction because the literature often views CVS and Palmer terminology like mental impulse and innate intelligence as synonymous when there were several models and not all included the same terminology.139

In his later years B. J. Palmer insisted that any definition of CVS must include the “mental impulse.”140 Mental impulse, from this perspective, was analogous to the energy and organizing information traveling over the nerve.141 Some authors from the Palmer school made this distinction a point of definition for CVS and others dismissed it.141, 142, 143 Also, CVS theorists who learned chiropractic between the years 1908 and 1915, such as Drain, Ratledge, and Firth, went on to lead schools and develop their own terminology to capture the same ideas,94, 112, 92, 144 as did their students such as Harper, Smallie, Higley, Muller, and Watkins.97, 98, 102, 145, 146

A common understanding of the history of ideas offers new insights into the ubiquity of CVS across early theory. It also highlights the importance of teacher-student relationships within chiropractic and dispels thoughts that CVS concepts only came from one school or one school of thought. I suggest that nearly every early chiropractic school was involved in defining and explaining CVS theories.

Limitations

This article reflects one person’s interpretation of historical writings and theories. Future reviews of the literature should include more systematic methods. Without detailed search parameters, inclusion and exclusion criteria, synthesis methods, a standard critical appraisal of the literature reviewed, and evaluation of bias, it is acknowledged that conclusions do need to be made with caution. A strength of this work is that it includes new insights into the history of the CVS, based on primary and secondary sources, many of which have not been included in previous works. However, this research is limited by the writings that are currently available. It is likely that historians will find more data in the future. These discoveries will hopefully further detail the history of seminal CVS theories and may alter our understanding of these concepts.

Conclusions

The term subluxation had several different meanings during the period from 1902 to 1907. Yet simultaneously it represented a fundamental concept for early chiropractors. This is one of the paradoxes of the history of the CVS. Each new definition multiplied the complexity of the subject. By understanding that even at this early stage of the profession’s development CVS was described in several different theories from different schools calls into question assertions in the literature that CVS was only a Palmer phenomenon or that it was only comprised of one set of ideas. New discoveries of historic documents provide an opportunity to fill in gaps in our knowledge of CVS history and theory and correct inaccuracies that may have been published in the past. This enriched view of the development of CVS theory allows for new and more informed ways to examine the recent literature, understand the past, and apply CVS models to clinical practice.

Practical Applications

-

•

This series of articles provides an interpretation of the history and development of chiropractic vertebral subluxation theories.

-

•

This series aims to assist modern chiropractors to interpret the literature and develop new research plans.

Alt-text: Unlabelled Box

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges Brian McAulay, DC, PhD, David Russell, DC, Stevan Walton, DC, Timothy J. Faulkner, DC, Joseph Foley, DC, and the Tom and Mae Bahan Library at Sherman College of Chiropractic for their assistance.

Funding Sources and Conflicts of Interest

The author received funding from the Association for Reorganizational Healing Practice and the International Chiropractic Pediatric Association for writing this series of papers. No conflicts of interest were reported for this study.

Contributorship

Concept development (provided idea for the research): S.A.S.

Design (planned the methods to generate the results): S.A.S.

Supervision (provided oversight, responsible for organization and implementation, writing of the manuscript): S.A.S.

Data collection/processing (responsible for experiments, patient management, organization, or reporting data): S.A.S.

Analysis/interpretation (responsible for statistical analysis, evaluation, and presentation of the results): S.A.S.

Literature search (performed the literature search): S.A.S.

Writing (responsible for writing a substantive part of the manuscript): S.A.S.

Critical review (revised manuscript for intellectual content, this does not relate to spelling and grammar checking): S.A.S.

References

- 1.Nelson C, Lawrence D, Triano J. Chiropractic as spine care: a model for the profession. Chiropr Man Ther. 2005;13(1):9. doi: 10.1186/1746-1340-13-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huijbregts P. The chiropractic subluxation: implications for manual medicine. J Man Phys Ther. 2005;13(3):139–141. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perle S. N Y State Chiropr Assoc Newsletter. Vol. 11. 2012; August. Foundation for Anachronistic Chiropractic Pseudo-Religion. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lerner C. Palmer College Archives; Davenport, IA: 1952. The Lerner Report. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rehm W. Legally defensible: chiropractic in the courtroom and after, 1907. Chiropr Hist. 1986;6:51–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keating J. The evolution of Palmer's metaphors and hypotheses. Philos Constr Chiropr Prof. 1992;2(1):9–19. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palmer D.D. Letter to B.J. Palmer; April 27, 1902. In: Faulkner T., editor. The Chiropractor's Protégé: The Untold Story of Oakley G. Smith's Journey with D.D. Palmer in Chiropractic's Founding Years. Association for the History of Chiropractic; Rock Island, IL: 2017. p. 103. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith OG. Advertisment. In: Faulkner T., editor. The Chiropractor's Protégé: The Untold Story of Oakley G. Smith's Journey with D.D. Palmer in Chiropractic's Founding Years. Association for the History of Chiropractic; Rock Island, IL: 2017. p. 72. [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeJarnette MB. The chiropractic subluxation. ACA J Chiropr. 1965;2(6):8–11. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nelson C. The subluxation question. J Chiropr Humanit. 1997;7:46–55. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haavik-Taylor H, Holt K, Murphy B. Exploring the neuromodulatory effects of vertebral subluxation. Chiropr J Aust. 2010;40:37–44. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keating J, Charton K, Grod J, Perle S, Sikorski D, Winterstein J. Subluxation: dogma or science. Chiropr Osteopat. 2005;13:17. doi: 10.1186/1746-1340-13-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peters R. Integral Altitude; Asheville, NC: 2014. An Early History of Chiropractic: The Palmers and Australia. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Palmer BJ. Vol. 2. The Palmer School of Chiropractic; Davenport, IA: 1907. The Science of Chiropractic: Eleven Physiological Lectures. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davis A. F. L. Rowe; Cincinnati, OH: 1905. Neurology, Embracing Neuro-Ophthalmology, the New Science for the Successful Treatment of All Functional Human Ills: Neuropathy, Chiropractic, Magnetism, Suggestive Therapeutics, Phrenology and Palmistry, as Related to Neuropathy. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Faulkner T. Association for the History of Chiropractic; Rock Island, IL: 2017. The Chiropractor's Protégé: The Untold Story of Oakley G. Smith's Journey with D.D. Palmer in Chiropractic's Founding Years. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith O, Langworthy S, Paxson M. American School of Chiropractic; Cedar Rapids, IA: 1906. A Textbook of Modernized Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gatterman M. Indications for spinal manipulation in the treatment of back pain. ACA J Chiropr. 1982;19(10):51–52. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gibbons R. Solon Massey Langworthy: keeper of the flame during the ‘lost years' of chiropractic. Chiropr Hist. 1981;1(1):15–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson C. Modernized chiropractic: reconsidered: beyond foot-on-hose and bones-out-of-place. J Man Phys Ther. 2006;29(4):253–254. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2006.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gibbons R. Joy Loban and Andrew P. Davis: itinerant healers and “schoolmen," 1910-1923. Chiropr Hist. 1991;11(1):23–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zarbuck M. Chiropractic parallax: part 1. Ill Prairie State Chiropractors Assoc J Chiropr. 1988; January [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gaucher-Peslherbe P. National College of Chiropractic; Chicago, IL: 1993. Chiropractic: early concepts in their historical setting. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith O. Clarinda Herald, Timothy Faulkner Archives; February 4, 1902. In: Faulkner T., editor. The Chiropractor's Protégé: The Untold Story of Oakley G. Smith's Journey with D.D. Palmer in Chiropractic's Founding Years. Association for the History of Chiropractic; Rock Island, IL: 2017. p. 103. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Banning JW. The importance of the atlas. J Osteopat. January 1901:13–15. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zarbuck M. Chiropractic parallax: part 5. Ill Prairie State Chiropractors Assoc J Chiropr. 1989;9(1):4–10. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Palmer BJ. The Davenport Times. August 1902. Chirorpactic: its value to suffering humanity. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burtch C. The relation of vertebral displacement to disease. Backbone. 1903;1(1):43–45. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Announcement 1902. Cedar Rapids, IA: American School of Chiropractic and Nature Cure; 1902. In: Faulkner T. The Chiropractor's Protégé: The Untold Story of Oakley G. Smith's Journey with D.D. Palmer in Chiropractic's Founding Years. Rock Island, IL: Association for the History of Chiropractic; 2017:131.

- 30.Palmer DD. The Davenport Times. June 14, 1902. Is chiropractic an experiment? [Google Scholar]

- 31.Waters T. Lulu, Inc.; Raleigh, NC: 2015. Fishing for Palmer in What Cheer: D.D. Palmer 1882-1886. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Palmer DD. The Burlington Daily Hawkey: Sunday Morning. October 9, 1887. Cured by magnetism. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Palmer DD. Chiropractic. 1897;January;(17) [Google Scholar]

- 34.Palmer DD. Chiropractic. 1897;March;(18) [Google Scholar]

- 35.Palmer DD. Chiropractic. 1900;(26) [Google Scholar]

- 36.Palmer DD. Portland Printing House; Portland, OR: 1910. The Science, Art, and Philosophy of Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Palmer DD. Chiropractic. 1902;(29) [Google Scholar]

- 38.Palmer DD. Palmer Infirmary and Chiropractic Institute; Davenport, IA: 1903. Innate Intelligence. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Palmer DD. Communicating nerves. Chiropr Adjust. 1909;1(2):40. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Palmer D. Bawden Brothers; Davenport IA: 1967. The Palmers. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Palmer DD, Palmer BJ. Chiropractic book. Chiropractor. 1906;2(2):8. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Palmer DD, Palmer BJ. The Palmer School of Chiropractic; Davenport, IA: 1906. The Science of Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Palmer DD. Chiropractic defined. Chiropractor. 1904;1(1) [Google Scholar]

- 44.Palmer DD. Lesion versus sub-luxations. Chiropractor. 1906;2(3):13. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Palmer DD. Immortality. Chiropractor. 1906;2(3):14–16. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Palmer DD. Foreword. Chiropr Adjust. 1909:January;1(2) [Google Scholar]

- 47.Palmer DD. Foreword. Chiropr Adjust. 1909;1(2):29. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moore S. Johns Hopkins University Press; Baltimore, MD: 1993. Chiropractic in America: The History of a Medical Alternative. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wardwell W. Mosby; St. Louis, MO: 1992. Chiropractic: History and Evolution of a New Profession. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Drum D. The vertebral motor unit and intervertebral foramen. In: Goldstein M, editor. The Research Status of Spinal Manipulative Therapy: A Workshop Held at the National Institutes of Health, February 2-4, 1975. Vol. 15. U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare; Bethesda, MD: 1975. pp. 63–75. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Leach R. 4th ed. Lippincott; Philadelphia, PA: 2004. The Chiropractic Theories: A Textbook of Scientific Research. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Palmer DD. Chiropractor. 1905;1(5):1. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Palmer BJ. Palmer Chiropractic School and Infirmary; Davenport, IA: 1903. Chiropractic Proofs. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Palmer BJ. Vol. 5. Palmer School of Chiropractic; Davenport. IA: 1909. Philosophy of Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Palmer BJ. 2nd ed. Vol. 3. Palmer School of Chiropractic; Davenport, IA: 1911. The Philosophy and Principles of Chiropractic Adjustments: A Series of Thirty-Eight Lectures. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Catalogue of Copyright Entries. Library of Congress Copyright Office, Goverment Printing Office; Washington, DC: 1907. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Palmer BJ. Vol. 25. Palmer College; Davenport, IA: 1951. Clinical Controlled Chiropractic Research. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Palmer DD. Luxations adjusted. Chiropr Adjust. 1909;1(2):25–28. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Advertisement. Vol. 3: the science of chiropractic. Chiropractor. 1907;3(9-10):59. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Palmer BJ. Vol. 3. Palmer School of Chiropractic; Davenport, IA: 1908. The Philosophy and Principles of Chiropractic Adjustments: A Series of Twenty-Four Lecures. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Keating J. Association for the History of Chiropractic; Davenport, IA: 1997. B.J. of Davenport: The Early Years of Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Palmer BJ. Vol. 4. Palmer School of Chiropractic; Davenport, IA: 1908. The Science of Chiropractic: Causes Localized. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Palmer BJ. Vol. 6. Palmer School of Chiropractic; Davenport, IA: 1911. The Philosophy, Science, and Art of Chiropractic Nerve Tracing: A Book of Four Sections. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Davis AP. F.L. Rowe; Cincinnati, OH: 1909. Neuropathy: The New Science of Drugless Healing Amply Illustrated and Explained Embracing Ophthalmology, Osteopathy, Chiropractic Science, Suggestive Therapeutics, Magnetics, Instructions on Diet, Deep Breathing, Bathing etc. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zarbuck M. Chiropractic parallax: part 2. Ill Prairie State Chiropractors Assoc J Chiropr. 1988;9(2):4-5, 14-16. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Smith O. Author; Chicago, IL: 1932. Naprapathic Genetics: Being a Study of the Origin and Development of Naprathy. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zarbuck M. A profession for ‘Bohemian chiropractic': Oakley Smith and the evolution of naprapathy. Chiropr Hist. 1986;6:77–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Swanberg H. Chicago Scientific Publishing; Chicago, IL: 1915. The Intervertebral Foramina in Man: The Morphology of the Intervertebral Foramina in Man, Including a Description of Their Contents and Adjacent Parts, With Special Reference to the Nervous Structures. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cramer G, Scott C, Tuck N. The holey spine: a summary of the history of scientific investigation of the intervertebral foramina. Chiropr Hist. 1998;18(2):13–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Palmer DD. Foley Archives. 1892;May 25. Letter to W.J. Joseph M. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Palmer DD. Ed, Borchert, Printer. 1889;June 20. Cripples cured! The sick get well by magnetism. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Waters T. Lulu, Inc.; Raleigh, NC: 2013. Chasing D.D.: D.D. Palmer in the News 1886-1913. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Palmer DD. 1896. The Magnetic Cure. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Palmer DD. Chiropractic. 1899;March;(26) [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gaucher-Peslherbe P, Wiese G, Donahue J. Daniel David Palmer’s medical library: the founder was “into the literature.”. Chiropr Hist. 1995;15(2):63–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gaucher-Peslherbe P. DD Palmer as authentic medical radical. J Neuromusculoskelet Syst. 1995;3(4):175–181. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Palmer DD. Press of Beacon Light Printing Co; Los Angeles, CA: 1914. The Chiropractor. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Palmer DD. Letter to P.W. Johnson. May 4, 1911. In: Foley J, editor. D. D. Palmer's Second Book The Chiropractor - 1914 Revealed. Chiropr Hist. 2017. pp. 72–86. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gaucher-Peslherbe P. Defining the debate: An exploration of the factors that influenced chiropractic's founder. Chiropr Hist. 1988;8(1):15–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gaucher-Peslherbe P. Chiropractic, an illegitamate child of science? II. De opprobria medicorum. Eur J Chiropr. 1986;34:99–106. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Palmer BJ. Vol. 24. Palmer College; Davenport, IA: 1950. Fight to Climb. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Palmer DD. June 6, 1906. Letter to B.J. Palmer. Available at: https://www.institutechiro.com/gens/first-generation-chiropractors/dd-palmer/books-and-writings/dd-palmer-letters-john-howard/. Accessed November 28, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Nakamura J, Csikszentmihalyi M. The concept of flow. In: Csikszentmihalyi M, editor. Flow and the Foundations of Positive Psychology. Springer; New York, NY: 2014. pp. 239–263. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Albanese C. Yale University Press; New Haven, CT: 2007. A Republic of Mind and Spirit: A Cultural History of American Metaphysical Religion. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Stone A. Lung and Hygienic Institute; Troy, NY: 1879. The New Gospel of Health: An Effort to Teach People the Principles of Vital Magnetism: or, How to Replenish the Springs of Life Without Drugs or Stimulants. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Faulkner T, Foley J. The science, art, and philosophy of chiropractic by D.D. Palmer: identification and rarity of editions in print with a survey of original copies. Chiropr Hist. 2015;35(1):36–45. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Foley J. The chiropractor 1914: revealed. Chiropr Hist. 2017;37(1):75–76. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bovine G. D.D. Palmer's adjustive technique for the posterior apical prominence: “Hit the High Places.". Chiropr Hist. 2014;34(1):7–19. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Palmer DD. Chiropractic defined. Chiropractor. 1905;1(4) [Google Scholar]

- 90.Palmer BJ. Vol. 13. Palmer College; Davenport, IA: 1920. A Textbook on the Palmer Technique of Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Vedder H. Vol. 8. Palmer College of Chiropractic; Davenport, IA: 1922. Chiropractic Physiology. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Firth J. Vol. 7. Palmer College of Chiropractic; Davenport, IA: 1925. Chiropractic Symptomatology. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Palmer BJ. Vol. 27. Palmer College; Davenport, IA: 1951. History Repeats. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ratledge T. Ratledge; Los Angeles, CA: 1949. The Philosophy of Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Drain J. Standard Print Co; San Antonio, TX: 1949. Man Tomorrow. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Palmer DD. Letter to the editor. Religio-Philos J. 1872;12(16):6. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Walton S. The Institute Chiropractic; Asheville, NC: 2017. The Complete Chiropractor: RJ Watkins, DC, PhC, FICC, DACBR. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Harper W. Texas Chiropractic College; Pasadena, TX: 1997. Anything Can Cause Anything: A Correlation of Dr. Daniel David Palmer's Priniciples of Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Toftness I. Philosophy of Chiropractic Correction. Wisconsin: I.N. Toftness, DC, PhC; 1977.

- 100.Epstein D. April 1996. Spinal system integrity. Network Spinal Analysis: Basic Level Intensive. San Francisco, CA: Innate Intelligence, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Weiant C. Chiropractic Institute; New York, NY: 1958. Medicine and Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Muller RO. The Chiro Publishing Co; Toronto, ON, Canada: 1954. Autonomics in Chiropractic: The Control of Autonomic Imbalance. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Homewood AE. 1981. Neurodynamics of the Vertebral Subluxation. 3rd ed. Homewood. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Keating J. Several pathways in the evolution of chiropractic manipulation. J Man Phys Ther. 2003;26(5):300–321. doi: 10.1016/S0161-4754(02)54125-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Busse J, Wilson K, Campbell J. Attitudes towards vaccination among chiropractic and naturopathic students. Vaccine. 2008;26(49):6237–6243. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Morgan L. Innate intelligence: its origins and problems. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 1998;42(1):35–41. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Keating J. A brief history of the chiropractic profession. In: Haldeman S, editor. Principles and Practice of Chiropractic. McGraw Hill; New York, NY: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 108.McAulay B. Rigor in the philosophy of chiropractic: beyond the dismissivism/authoritarian polemic. J Chiropr Humanit. 2005;12:16–32. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Mirtz T. Universal intelligence. J Chiropr Humanit. 1999;9:55–71. [Google Scholar]

- 110.Keating J, William D, Harper MS., Jr. DC: Anything Can Cause Anything. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2008;52(1):38. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Gatterman M. 2nd ed. Mosby; St. Louis, MO: 2005. Foundations of Chiropractic Subluxation. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Keating J, Callender A, Cleveland CA. Association for the History of Chiropractic; Rock Island, IL: 1998. History of Chiropractic Education in North America. [Google Scholar]

- 113.Zarbuck M, Hayes M. Following D.D. Palmer to the west coast: the Pasadena connection, 1902. Chiropr Hist. 1990;10(2):17–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Peters R, Chance M. Disasters, discoveries, developments, and distinction: the year that was 1907. Chiropr J Aust. 2007;37:145–156. [Google Scholar]

- 115.Gibbons R, Wiese G. Fred Rubel: the first black chiropractor? Chiropr Hist. 1991;11(1):8–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Keating JC. “Heat by nerves and not by blood": the first major reduction in chiropractic theory, 1903. Chiropr Hist. 1995;15(2):70–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Troyanovich S, Gibbons R. Finding Langworthy: the last years of a chiropractic pioneer. Chiropr Hist. 2003;23(1):7–16. [Google Scholar]

- 118.Gibbons R. Assessing the oracle at the Fountainhead: B.J. Palmer and his times, 1902-1961. Chiropr Hist. 1987;7(1):8–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Zarbuck M. Chiropractic parallax: part 3. Ill Prairie State Chiropractors Assoc J Chiropr. 1988;9(3):4-5,17-19. [Google Scholar]

- 120.Keating J. Stockton Foundation for Chiropractic Research; Stockton, CA: 1992. Toward a Philosophy of the Science of Chiropractic: A Primer for Clinicians. [Google Scholar]

- 121.Palmer DD. Chiropractic rays of light. The Chiropractor. 1905;1(7):17–23. [Google Scholar]

- 122.Leach R. Williams and Wilkins; Baltimore, MA: 1994. The Chiropractic Theories: A Textbook of Scientific Research. 3rd ed. [Google Scholar]

- 123.Rehm W. Necrology. In: Dzaman F, ed. Who's Who in Chiropractic International. 2nd ed. Littleton, CO: Who's Who in Chiropractic International Publishing Co; 1980.

- 124.Rosenthal M. The structural approach to chiropractic: from Willard Carver to present practice. Chiropr Hist. 1981;1(1):25–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Leach R. Mid-South Scientific Publishers; Mississippi State, MS: 1980. The Chiropractic Theories: A Synopsis of Scientific Research. [Google Scholar]

- 126.Leach R. 4th ed. Williams and Wilkins; Baltimore, MD: 1986. The Chiropractic Theories: A Textbook of Scientific Research. [Google Scholar]

- 127.Verner J. Dr. P.J. Cerasoli; Brooklyn, NY: 1956. The Science and Logic of Chiropractic. 8th ed. [Google Scholar]

- 128.Terrett A. The genius of D.D. Palmer: An exploration of the origin of chiropractic in his time. Chiropr Hist. 1991;11(1):31–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Coulter I. Butterworth-Heinemann; Woburn, MA: 1999. Chiropractic: A Philosophy for Alternative Health Care. [Google Scholar]

- 130.Meeker W, Haldeman S. Chiropractic: a profession at the crossroads of mainstream and alternative medicine. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:216–217. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-3-200202050-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Schafer R. ACA; Des Moines, IA: 1973. Basic Chiropractic Procedure Manual. [Google Scholar]

- 132.Cooperstein R, Gleberzon B. Churchill Livingstone; Philadelphia, PA: 2004. Technique Systems in Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 133.Senzon S. Chiropractic and systems science. Chiropr Dialogues. 2015;25:9–20. [Google Scholar]

- 134.Gregory AS. Author; Oklahoma City, OK: 1910. Spinal Adjustment: An Auxillary Method of Treatment. [Google Scholar]

- 135.Loban J. Loban Publishing Co; Denver, CO: 1915. Technic and Practice of Chiropractic. 2nd ed. [Google Scholar]

- 136.Forster A. The National School of Chiropractic; Chicago, IL: 1915. Principles and Practice of Spinal Adjustment. [Google Scholar]

- 137.Carver W. 2nd ed. Universal Chiropractic College; Davenport, IA: 1915. Carver's Chiropractic Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 138.Coleman R, Wolf K, Dever L, Coleman J, Wenham T. Does the chiropractic of modernized chiropractic still live? Chiropr Hist. 2015;35(2):20–35. [Google Scholar]

- 139.Clusserath M. Vertebral subluxation and a professional objective for chiropractic. J Chiropr Humanit. 1999;9:9–20. [Google Scholar]

- 140.Palmer BJ. Vol. 39. Palmer School of Chiropractic; Davenport, IA: 1966. Our Masterpiece. [Google Scholar]

- 141.Boone W, Dobson G. A proposed vertebral subluxation model reflecting traditional concepts and recent advances in health and science. J Vert Subl Res. 1996;1:19–36. [Google Scholar]

- 142.Barge F. Vol. V. Bawden Brothers, Inc.; Eldridge, IA: 1987. Life Without Fear: Chiropractic's Major Philosophical Tenets. [Google Scholar]

- 143.Haldeman S, Drum D. The compression subluxation. J Clin Chiropr. 1971;7:10–21. [Google Scholar]

- 144.Drain J. Alumni Association of the Texas Chiropractic College; San Antonio, TX: 1927. Chiropractic Thoughts. [Google Scholar]

- 145.Smallie P. World-Wide Books; Stockton, CA: 1984. Scientific Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 146.Higley H. Chiropractic philosophy: an interesting interpretation of basic tenets. Chiropr J. 1938;7(2) 13-14, 54-55. [Google Scholar]