Abstract

Objective

The objective of this article is to review and discuss the history of chiropractic vertebral subluxation (CVS) between the years 1949 and 1961.

Discussion

Chiropractic texts from this period include books from 3 of D. D. Palmer’s students, Ratledge, Drain, and B. J. Palmer, and new works by Janse, Illi, Muller, and R. J. Watkins. Theories during this period included developments from B. J. Palmer’s research clinic and his final theories. The period also included the primary theories of Ratledge on etiology of CVS and Drain’s models of spinal curves and CVS patterns. Janse supported Illi’s new models of pelvic subluxation dynamics with cadaver studies and also developed lumbar research with Fox in the 1950s. The qualitative models of Muller on the role of CVS in sympathetic and parasympathetic systems was unique. R. J. Watkins further developed his initial theories on reflex system models as well as his first models of proprioception. Instrumentation was used in many chiropractic research programs to develop additional models.

Conclusion

The CVS theories during this period built on previous models but also added new and innovative theories based on research and collaboration.

Key indexing terms: Chiropractic, History

Introduction

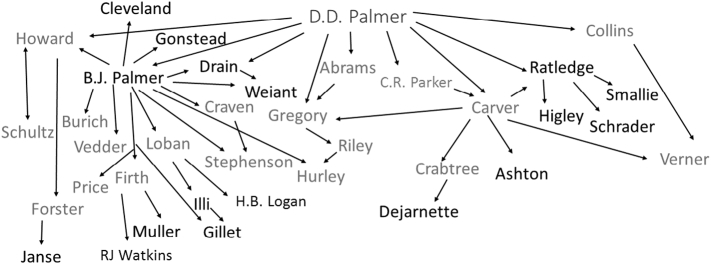

Between 1949 and 1961, pluralities of chiropractic vertebral subluxation (CVS) theories were published from schools and research facilities. These included Palmer School of Chiropractic, Ratledge Chiropractic Schools (RCS), Texas Chiropractic College (TCC), Lincoln Chiropractic College, Canadian Memorial Chiropractic College (CMCC), Chiropractic Institute of New York, National Chiropractic College, and Illi’s Institute for Research in The Statistics and Dynamics of the Human Body of Geneva, Switzerland (Fig 1).1, 2 The theories during this period represent an integration of prior theories with the addition of new models and new findings. Developments of theories include areas such as etiology,3, 4, 5 chronicity,5, 6, 7 reflex models,8 energetic models,7 spinal biomechanics,2 complex neurologic models,2, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 the spine’s role in stress and autonomic tone,6 integrations of Pottenger’s sympatheticatonia,6, 10 further applications of Speransky’s neurodystrophic theory,8 development of typologic patient assessments based on neurologic assessments,6 and the higher reaches of health and well-being in relation to CVS.4, 5 Many hypotheses are embedded within these contributions that may still be explored with current technology and research designs.

Fig 1.

Schools that inspired theory and research during the years 1949-1961.

Several theories and chiropractic consensus processes from the 1960s to the 1990s have roots in the CVS models from this time.11, 12, 13, 14, 15 By understanding the theories between 1949 and 1961, we may better understand more recent chiropractic historical events and knowledge as well as the research challenges faced by increasingly complex definitions of CVS.

The purpose of this article is to discuss CVS theories from 1949-1961, as published by T. F. Ratledge, J. R. Drain, B. J. Palmer, R. O. Muller, R. J. Watkins, Fred Illi, and J. J. Janse. The historical section is followed by a review of D. D. Palmer’s chiropractic paradigm to better understand the renaissance of D. D. Palmer scholarship from this era. The potential impact of these various theorists, including their collaborations and the way their works have been used in the literature, is also discussed.

Chiropractic Vertebral Subluxation Theory from 1949 to 1961

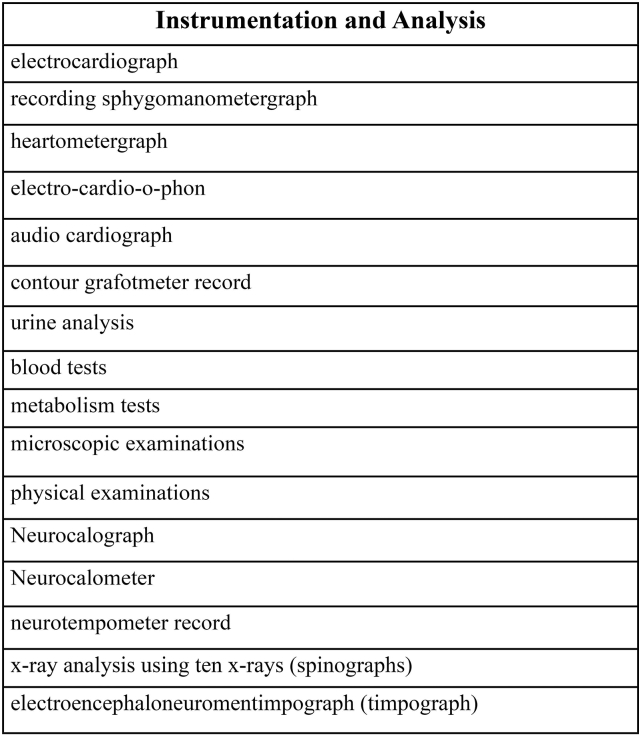

The evolution of CVS theory between 1949 and 1961 set a foundation for modern chiropractic principles. Three of D. D. Palmer’s students, T. F. Ratledge,3 J. R. Drain,5 and B. J. Palmer,16 published texts in 1949 (Fig 2). B. J. Palmer authored 16 books in the final 12 years of his life before he died in 1961.17 B. J. Palmer’s death marked the beginning of the second part of chiropractic history.18 Drain and Ratledge played important roles in the profession’s development, especially in politics, education, and the legal realm.1, 19, 20, 21, 22 Other theorists from this period include Illi and his collaboration with Janse,23 R. O. Muller’s integration of CVS and the autonomic nervous system,6 and R. J. Watkins’s expansion of his theories.8

Fig 2.

Some of the teacher-student relationships of theorists, starting with D. D. Palmer.

Based on my observations, few of the authors from this period are studied and that their roles in developing the foundation of modern chiropractic theory are virtually unknown. Most of the texts were self-published, so only students and colleagues of the authors may have read their works.3, 5, 6, 16 Some of the leaders from this period, such as Drain, Ratledge, and Watkins, were aware of B. J. Palmer’s earlier theories, though it seems that few of his peers were reading his latest books. Drain and Ratledge expressed their friendship and admiration for B. J. Palmer but did not adopt his upper cervical perspective.5, 20 Furthermore, chiropractic schools were in competition with each other for students, so requiring textbooks written by leaders from other colleges may have been bad for business. I provide the following discussion about chiropractic theories to offer some context for the profession’s foundation.

T. F. Ratledge’s Theory (1949)

Ratledge contributed to CVS models.19, 20 He pioneered teaching the methods of his teachers, Willard Carver and D. D. Palmer.24 Ratledge practiced chiropractic from 1908 until the 1950s and helped to establish chiropractic licensing laws in Oklahoma, Kansas, and California.24 He went to jail for practicing medicine without a license because he refused to accept a drugless healer's license. His protest attempted to pressure the legislature to pass a chiropractic licensing law. (Fig 3).19 He sold his Ratledge Chiropractic School in Los Angeles to Cleveland Chiropractic College in 1951.1

Fig 3.

Dr. T. F. Ratledge going to jail in California. From the Fort Wayne Sentinel, 1916.

It is thought that Ratledge stopped teaching in 1948 because his rivals in California successfully passed an amendment adding orthodox medical practices to the 1922 chiropractic act without going through a referendum like the original law.19 To lobby for his position, Ratledge attended every legislative meeting of the California legislature from 1911 until 1955.21 However, losing this battle was a major personal defeat.25 Ratledge formed The Chiropractic Forum in 1949, a monthly breakfast meeting for chiropractors, which continued until 1956.19 His lectures from the forum were copyrighted and published in a 3-ring binder.3 Four original copies are known to exist today.19, 26 (Also see S. Senzon’s e-mail letter to Zail Khalsa, December 2015.)

In 1938 Henry Higley wrote an article on the philosophy of chiropractic in the National Chiropractic Association (NCA) journal.27 Higley was a 1936 RCS graduate and was on the faculty at the time. The article provided a glimpse into Ratledge’s early theories because no known articles of his were published during that time. The ideas in Higley’s article were consistent with Ratledge’s future writings,20, 25 including his 1949 lectures.3

According to Ratledge, the CVS could only be viewed in the context of life and the environment as 1 universal cause of stimuli.3 His etiology of CVS developed from D. D. Palmer and Carver and was interlinked with what Ratledge referred to as the 3 factors of matter: chemical, mechanical, and thermal. From this perspective, an “unneutral” environment could lead to changes in the body’s chemistry, structure, or temperature. These changes in the internal environment were suggested to be causes of CVS and its obstructive nerve pressure. Following this line of reasoning, when this pressure was reduced and “the interference to the transmission of nervous impulses”3 was removed, the functions could appropriately respond to the environmental demands (Fig 4).3

Fig 4.

Ratledge’s model.

Ratledge agreed with the D. D. Palmer doctrine that the body self-corrected CVS during sleep when the muscles were relaxed.3, 28 Ratledge hypothesized that during sleep the cartilage between the vertebrae expanded. Thus when the environmental circumstances were satisfactory, nature made the adjustment. If the circumstances were not satisfactory, the chiropractic adjustment was required to make the correction.3 The proposition was that the chiropractor attempted to bring about such satisfactory circumstances in nature, over time, through adjustments, and then by counseling to the patient to prevent the same environmental causes in the future. Summing up Ratledge’s perspective on this, Higley wrote, “Under such circumstances, the only indicated things to do are: first, the re-establishment of proper vertebral relationship by mechanical adjustment; second, to prevent the individual from exposure to further environmental unneutrality.”27

For Ratledge, the essence of chiropractic was philosophy, which centered on the adjustment of CVS. He believed that the adjustment helped an individual to use the body’s potential energies to function and thus achieve health.3

J. R. Drain’s Theories (1949-1955)

James Riddle Drain graduated from the Palmer School of Chiropractic in 1911, practiced for many years, and then bought TCC, where he was president until 1948.29 His 1927 book, Chiropractic Thoughts, was published as a second edition in 1946 and included a new section with letters and brief thoughts.30 He published Man Tomorrow in 1949.5 An unpublished manuscript for his final book, We Walk Again, was written in 1955 (Fig 5).31 Drain died in 1958.22 Man Tomorrow was his magnum opus and started as an invitation to 100 authors for contributions.5 Seven authors contributed. Drain also included dozens of his essays from the 1930s and 1940s and many case studies with radiograph reproductions. His CVS theories were based on the first Palmer Green books and shaped by years of practice and teaching.5

Fig 5.

Jim Drain with Leo Spears from We Walk Again by Jim Drain, Spears Papers, Cleveland Archives. Reproduced with permission from the Drain family.

In We Walk Again,31 Drain described a complex methodology to detect and correct CVS for children with polio. The manuscript contains dozens of case studies with photos of children recovering from the polio epidemic of that era. In 1949 Drain wrote that every case he had ever had of polio or infantile paralysis had a CVS in the cervical, dorsal, or lumbosacral region.5 Some patients were in his care for up to 18 months.31

In Man Tomorrow, Drain suggested that CVS may be produced by muscle contraction from events, such as influenza in the acute stage. He proposed that this type of CVS developed over time, for example into an ankylosed spine with impacts on the senses.5 He proposed that 1 or more CVS may affect an individual’s ability to express life’s full potential and genius, leading to various complexes and “life” failures.5

The CVS, according to Drain, interfered with “mental directed energy,” or the “flow of vital energy,” and “proper” body and mental expression.5 Drain felt that CVS pressed on nerves at the foramen and should be adjusted. The importance of this was to allow the power directed by innate intelligence to reach the tissue for function. One attribute of this power was the ability to cure every disease.5 For Drain, the principle of chiropractic was the CVS of vertebra. He hypothesized that they were areas of lowered vitality and that cure and recovery comes from a release of vitality. Through compensation and development of abnormal curves, the spine often contained multiple CVS with 1 major at a time. Removing them eliminated the cause and allowed normal “body tone” and complete recovery.5

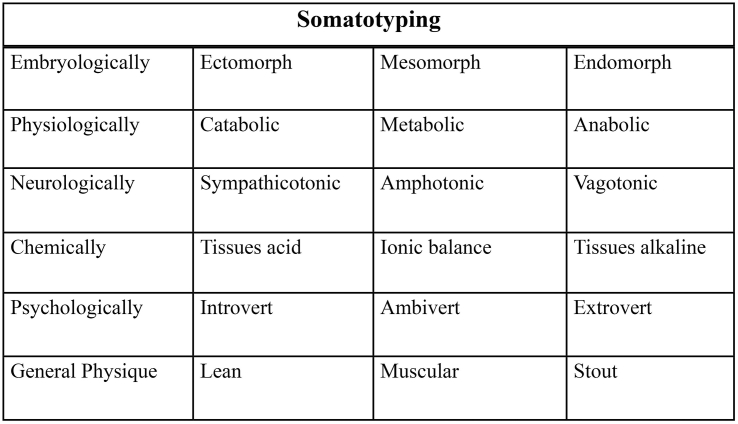

B. J. Palmer’s Theories and Final Contributions

B. J. Palmer produced a voluminous output in his final 12 years (Fig 6).4, 7, 16, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44 His last writings indicate changes in his philosophy and theories of CVS.45, 46, 47 His methodological assessment of patients at this point included an examination that included vital signs, laboratory tests, and several instrumentation measurements (Fig 7).48 All these tests were performed weekly. New x-ray images were taken biweekly with a complete set of 10 spinographs performed by the time of discharge from his clinic. Neurocalograph-neurocalometer-neurotempometer readings were taken daily.48 In 1955 B. J. and his staff developed a priority system for adjusting, which included correcting misalignments lower than axis if the thermographic pattern did not change within 2 weeks. 32, 49

Fig 6.

B. J. Palmer. Courtesy Special Services, Palmer College of Chiropractic.

Fig 7.

Instrumentation, vital signs, and laboratory tests used at the B. J. Palmer chiropractic clinic.

Between 1935 and 1960, at least 7000 cases from B. J.’s clinic were documented.48 There were 120 different forms used for keeping patient records, with an average of 80 pages per case.48, 50, 51, 52 Starting around 1945 and well into the 1950s, B. J. Palmer published several case studies each month in The Chiropractor. Case numbers ranged from 3400 to 5000.53 In the 1990s Palmer College of Chiropractic paid $40,000 to scan the documents that were still in good condition for both historical and research purposes.52

The electroencephaloneuromentimpograph (timpograph) was built with early electroencephalogram technology and might be described as an early attempt at surface electromyography.7 It was a precursor to modern versions of the electroencephalograph and electrocardiograph.54, 55 The instrument was built by Palmer’s engineers to measure electrical carrier waves in the muscles of the spine, scalp, and legs.7 Eriksen and Grostic wrote:

B.J. had hoped that this instrument would be able to prove the existence and location of the subluxation, and the validity of the adjustment by demonstrating the improvement of neuroelectrical transmission. This device proved to be quite promising; however, the technology of the day lacked solid-state high gain, low-noise amplifiers with computerized signal averaging, which limited its effectiveness.54

According to Palmer it cost $100 000 over 30 years perfecting the instrument.4 The pinpoint sensors were placed in 7 locations from the occiput to the legs. Thermography and x-ray analysis were used to determine the location for the sensors above and below the CVS.48 Readings were completed before and after the chiropractic adjustment.7 He claimed that the timpograph was able to detect the mental impulses as electrical waves traveling from the brain to the body and back.4, 45

Based on their reading of Palmer’s book Our Masterpiece, published posthumously,4 Haldeman and Hammerich suggested that only B. J. Palmer was able to interpret the timpograph readings.56 It is not evident from reading this reference that B. J. meant that.4 The clinic staff were trained in using and reading all of the instrumentation in the research.48, 50, 51 Also the instrument remained in operation until November 6, 1960, even though B. J. Palmer was living in Sarasota for his last decade.4, 57 Thus data evaluation continued even when B. J. Palmer was not at the clinic, so it is possible that others were able to interpret the findings.

Palmer’s new models of CVS had their roots in his original insights from 190758 but were based on his research in the B. J. Palmer Research Clinic and his own literature reviews on the new field of energy medicine,7, 45, 46, 59 including the works of Speransky, Morat, and Crile.60, 61, 62, 63 By 1951, when he summed up his research, the metaphors he used for mental impulse and CVS were even more energetic than his early writings on the topic between 1909 and 1936.45, 59, 64 He wrote, “Vertebral subluxation shorts energy flow—vertebral adjustment restores it and restores health.”7 He still held to his primary 4-part criteria for CVS, which included misalignment, occlusion, pressure, and interference to mental impulses. B. J. Palmer’s philosophical writings during this period included the impact of CVS correction on psychospiritual aspects of health and were directly related to his research in the clinic.41, 42, 43, 47 These insights were congruent with other psychologists and philosophers of time.65, 66, 67

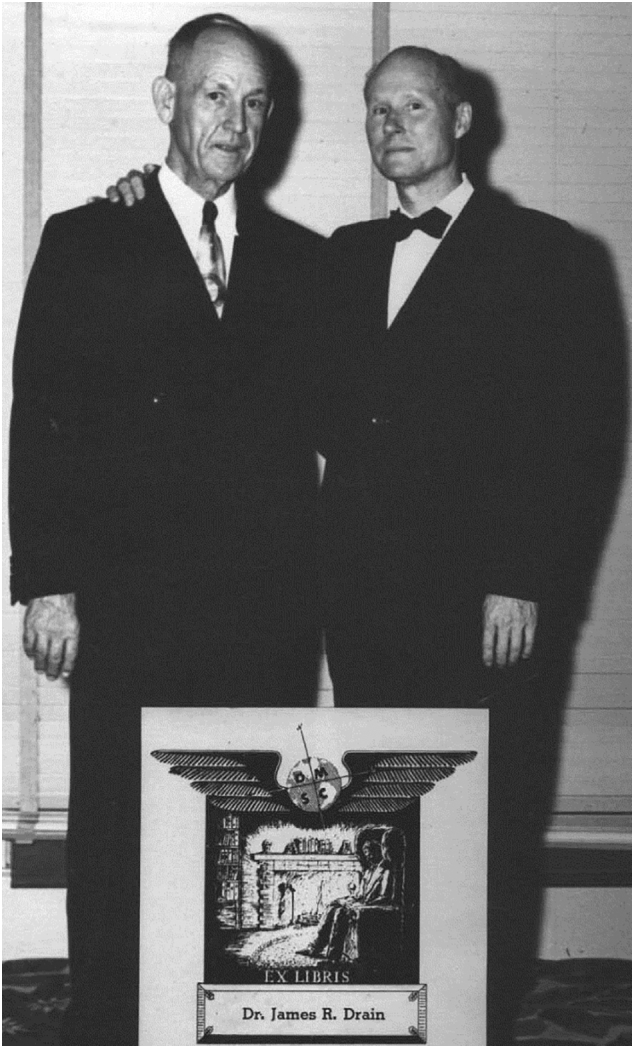

Muller’s Theory (1954)

R. O. Muller graduated from Lincoln Chiropractic College in 1937 and stayed on the faculty until 1941, when he taught R. J. Watkins. In 1946 he joined the faculty of the CMCC, where he became dean.29 In 1954 he wrote Autonomics in Chiropractic.6 Only 4 chiropractic authors (D. D. Palmer, J. N. Firth, A. L. Forster, and J. R. Verner) are cited in the book.28, 68, 69, 70 Muller based much of his theory on Firth and D. D. Palmer.6 To explain his qualitative approach he cited the fifth edition of Firth’s Chiropractic Diagnosis, published in 1948.68 The rest of the text included references to neural anatomy and physiology, chemistry, pathology, medicine, and osteopathy. It also referenced books about mind, body and behavior, medical constitutions, and psychiatry.6

Muller linked D. D. Palmer’s basic principle of chiropractic that “Life is the expression of tone”28 to Pottenger’s Symptoms of Visceral Disease.71 He wrote, “The chiropractor should be very concerned with the tone of the autonomic nervous system. For instance, Pottenger points out that every organ possesses a certain tonus; that is, a degree of tension.”6 Muller’s book represented a new integration of ideas on chiropractic and the nervous system. It was the first book to emphasize qualitative typology based on neurology in chiropractic (Fig 8).6

Fig 8.

Somatotypes that Muller used to develop his model.

According to Muller, the removal of CVS would benefit the vegetative equilibrium by affecting the autonomic tone of the patient. Adjustments could be done to affect the sympathetic or the parasympathetic nerves. He was not only talking about stimulation and inhibition, but how patients were approached based on their particular typology. Force application and every touch of the patient were supposed to be clinically considered based on the patient’s unique anatomy, body type, physiology, and symptomatology. Patients were to be assessed constitutionally as a sympathetic type or a parasympathetic type, not just according to symptoms.6 Muller’s book introduced some new terms and may be the first text in the chiropractic literature to use these new terms. Hyper- or hypoactivity of organs related to patients’ constitution and their response to “stress” and “alarm.”6 Seyle published his seminal article on stress in 1955 and book in 1956 and had already published his Fourth Annual Report on Stress by 1954.72, 73, 74, 75, 76 Autonomic imbalance often led to sympathetic dominance, similar to stress theory.8 Chiropractors were early to point out, however, that Selye emphasized the hormonal system and neglected the nervous system.77

Muller developed a priority system for adjusting each patient based on the patient’s typology. He found that the order and force application applied to the adjustment of each CVS had an impact on patient recovery. For example, he wrote:

In a given case of asthma where the following subluxations are considered for correction: atlas, fifth thoracic, tenth thoracic and base of sacrum—the chronological order in which these subluxations are corrected and the type of thrust to be used, can and does make all the difference between recovery and failure.6

Muller purported that the chiropractic profession agreed CVS was the greatest factor in the perpetuation of imbalance between the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems and that the adjustment was “normalizing” between these systems.6 In defining the CVS, Muller included a dis-relationship between 2 or more osseous structures and fixation. According to him, a fixation was a vertebra that lost its mobility but had not lost its alignment. Such a fixation might create nerve irritation.6 Based on the microscopic study of animals that underwent surgically induced CVS at the A. T. Still Research Institute in 1910,78 Muller concluded that nerve degeneration and other vasomotor disturbances to the dorsal nerve root were common. This also was related to decreased proprioception in the muscles and ligaments.6

Muller wrote that the CVS could create an area of lowered vitality, lowered tissue resistance, and a reduced functional capacity of the cord. He equated the irritation to stress, which decreased the vitality of the segment. It was proposed that this disrupted neural arc led to disease processes, which began as functional problems and later become organic.6

R. J. Watkins Theories (1951-1961)

In 1950 R. J. Watkins entered private practice and continued his scholarly activities.8 During this period he translated Tissot’s 3-volume text on bacteriology from French.8, 79 He also coauthored the second edition of Verner and Weiant’s Rational Bacteriology, published in 1953.80 In 1951 Watkins integrated the theories of Pottenger on sympatheticotonia and his own observations of sphincterismus with CVS.10 This related to cases of cardiospasm, duodenal spasm, pylorospasm, spastic colon, dysmenorrhea, and general nervous irritation. He wrote clinical briefs on chiropractic and migraine, neurodystrophies, and the upper thoracic complex.8 R. J. Watkins introduced the concept that reflexes could link multiple CVS together.81 For example, he proposed that a thoracic-cervical reflex was responsible for a mid-thoracic CVS causing an upper cervical CVS, resulting in migraine.8

Illi’s and Janse’s Model (1951)

Fred Illi was a 1927 graduate of Loban’s Universal Chiropractic College.82 He conducted research from 1931 into the 1970s at his institute in Switzerland. In the 1950s Illi was the first in the profession to make 16-mm x-ray motion spinal studies.23 With the help of Janse, Illi conducted several cadaver studies to supplement his spinal biomechanical research. Janse collaborated with Illi, published his work,23 and promoted it with Weiant.23, 83 The model of CVS developed by Illi and his group emphasized spinal movement, proprioception, spinal cord dynamics, and pelvic biomechanics.2

Illi described the unilateral CVS in terms of the sacral base fixating on 1 side in an anterior and inferior position in adults and children. The postural muscles of the spine were proposed to become distorted and the entire spinal mechanism from the head downward to become off-centered.2 This was thought to lead to pain and “systematic dysfunction occasioned by … lack of normal innervation.”2 The resulting muscle contractions were suggested to further disturb the equilibrium.

Because the vertebrae are embedded in neurologic “pools,” Illi postulated that CVS had several deleterious effects. The strained vertebral articulations could cause reflexive irritations in the nervous system, in part as a result of the weight of the head on the compensating lifeline of the spine.2 This excess off-centered weight was believed to lead to an inability for the nervous system to adapt because the membranes of the articular capsule, the ligaments, and the cartilage were under too much strain. Overstimulation of the neurology was proposed to lead to excessive stimulation of the emitting nerves, a contamination of incoming sensory streams, and unwanted discharge reactions of the motor units.2 Symptoms were thought to arise from this process and also from the impact on the vasomotor aspects of the spinal recurrent nerves. This was proposed to affect the vascularization of the cord itself, setting a vicious pathologic cycle into motion. D. D. Palmer and R. J. Watkins also wrote about the recurrent meningeal nerve.8, 28

According to Illi, signs and symptoms of CVS in children included painful symptoms or weakness of the pelvis, which could develop curvatures, painful limbs, unusual head carriage or gait, headaches, fatigue, and incoordination. He suggested that signs and symptoms in adults included neuralgias, which were often mistaken for rheumatism.2

D. D. Palmer Renaissance

This period might be viewed as a renaissance of D. D. Palmer’s works. B. J. Palmer,16 T. F. Ratledge,3 and Jim Drain studied directly under D. D. Palmer.5 Drain’s 1949 text included 6 essays on D. D. Palmer’s life by Cooley, another of D. D. Palmer’s students.5 Muller,6 Watkins,8 Weiant,83 and Harper all referenced D. D. Palmer in attempts to connect his theory to current literature on neurophysiology.84 Each of them also referenced Verner’s book,70 which was in its eighth edition in 1956. Verner referenced D. D. Palmer extensively.

The chiropractic paradigm was originally shaped by D. D. Palmer.28, 85, 86 In modern terms the paradigm may be interpreted as follows. An organism intelligently responds to the physical, emotional, and chemical stressors from the environment as best it can. Failures to successfully adapt may lead to contraction of muscles and a loss of natural connection between the articulating surfaces of joints, especially joints of the spine, which leads to impingements or pressure against nerves. This type of pressure could lead to increase or decrease activity in the nerve, which might affect organ function.28, 86 The chiropractic adjustment was developed as a specific thrust using the spinous processes and transverse processes as levers to reapproximate the articulating surfaces to a state closer to normal so that nerves may return to normal from being stretched or slack and so that normal tone or renitency of the tissues may follow, leading to greater organ function and improved physical, psychological, and spiritual health.28, 86

D. D. Palmer’s basic principle was that tension leads to pain and abnormal “functionating.”28 Functionating, a word used briefly during Palmer’s era,87 was an advancement on his 1887 concept of “dis-ease.”88 Abnormal “functionating” described a state of the nervous system caused by too much or not enough vibrational energy.28, 86

D. D. Palmer used the term tone as the basic principle of chiropractic, which relates to tension. D. D. Palmer writes, “Increased tension-increased pain. Tension above normal—tone—not only causes pain, but abnormal functionating – disease.”28 Palmer was referring to tension on the nerves, which he considered as “stretched” when impinged on. This resulted in change of “tone” in various tissues and organ systems, including the muscle system. Sensory distortions could be traced through palpation.

D. D. Palmer’s concept has not been emphasized in the recent publications, although it was paramount in CVS theories before 198089 and was included in the renaissance of theories beginning with the period from 1949 to 1961.5, 10, 16, 83, 84 Starting in 1975, early chiropractic research efforts focused on the empirical study of manipulation as it related to the relief of back pain.89, 90 Although valuable, this approach only captures a small portion of what Palmer described in his original theories. The 1949-1961 period included theories that were more congruent with the other elements of D. D. Palmer’s paradigm in terms of etiology, psychological and spiritual well-being in relation to CVS correction, and his overall theory of abnormal “functionating.”

Many chiropractors of this period embraced the theories from Speranksy,91 Pottenger,71 and Selye.72 Those theorists came to conclusions that were similar to D. D. Palmer’s in terms of how the central nervous system responds to sustained irritation and affects pathophysiology.28 The theorists of this period were looking at overall neurologic function in terms of autonomic tone and neurodystrophic processes6, 8 and more traditional chiropractic applications to acute and chronic pathophysiology.2, 3, 5, 92

Analysis of the 1949-1961 CVS Literature

The period from 1949 to 1961 encompassed a continued development and evolution of theories. There was congruence, especially in terms of links to D. D. Palmer’s paradigm across the major texts about CVS as well as new and innovative theories and models. Of the models from this period, Illi’s book The Vertebral Column: Lifeline of the Body seems to have been referenced the most.83, 93, 94, 95, 96 Other texts from the period, such as B. J. Palmer’s books, Ratledge’s lectures, Drain’s final texts, Muller’s book, and Watkins’ many articles, are not as well cited.

Several innovations to theories from this period are noteworthy, such as the influence of Ratledge, the development of new pattern theories, integration of new models of tone and vitality, and the psychospiritual elements of health and well-being evident in various writings on CVS and philosophy. Other important issues to consider include the use of scientific literature to substantiate CVS theory, new levels of collaboration among theorists, the impact of B. J. Palmer, and the importance of a nonmusculoskeletal emphasis of chiropractic.

Weiant described how CVS was perceived:

In recent years, a new body of scholarship has developed in the chiropractic profession which has critically appraised and revised theories of the nature and effect of vertebral subluxations.

Among the immediate effects are hypersensitivity of sensory nerves, increased motor response reflected in muscular contraction, and local hyperemia. All of these effects are signs of nerve irritation. While it is still recognized that this irritation may be produced by an alteration of the form and dimensions of the intervertebral foramen, emphasis has shifted from this foramen to the tissues surrounding the impulse-receiving nerve endings of the joint capsule.

It cannot be too strongly emphasized, however, that the case for chiropractic does not rest upon whether the theory of nerve pressure can be substantiated. The evaluation of chiropractic must take into consideration the clinical results obtained through its practice. A therapy judged empirically may be perfectly correct, even though the theory on which it happens to be based may be wrong. Under such circumstances, reason demands that the practice be accepted and the theory revised.97

He wrote this in 1954, 30 years after he completed his chiropractic degree and about 10 years after he earned his PhD in archeology from Columbia University and was named the head of the Chiropractic Research Foundation.

In 1955 a Danish chiropractor Hviid proposed 4 theories.98 He included the pressure theory hypothesis, which he felt was too simple. Citing prominent anatomists and physiologists, he felt that irritation was more likely than compression. He described the modified pressure theory based on Illi’s approach, which related to the recurrent meningeal nerve and proprioceptive impulses. The third approach was the fixation theory of Gillet, which he noted did not emphasize nerve pressure but vertebral fixation. He concluded with muscle-tension theory, whereby hypertense spinal and visceral muscles led to dysfunction as a result of CVS, fixations, and other disturbances.98

Cross-pollination of ideas were evident in various areas of chiropractic and especially in CVS theories. For example, Gillet’s theories of fixation are cited in Muller,6 Watkins,8 Illi,2 and Janse.92 And yet Gillet was inspired in part by Watkins’ identification of the key role played by the intrinsic intersegmental muscles.8 Watkins and Gillet corresponded in the late 1940s. From 1945 to 1949, Gillet wrote a series of articles in the NCA Journal about the development of motion palpation.8 In 1949 Gillet wrote:

I have had the great pleasure of communicating with one of the most intelligent professors in the profession, Watkins, of the Canadian Memorial College. He also has noticed these bulges, and has analyzed them as muscular contractions. He has even gone so far as to name each muscle involved in the different kinds of bulges and check them up with the deviations shown-up by the radiograph. His drawings are really very illuminating, and I sincerely hope he will soon publish his findings.8

During this period, C. S. Cleveland Sr first published his teaching notes, much of which contained B. J. Palmer’s theories.99 Cleveland Sr conducted the first animal studies in chiropractic to research CVS during this period.100 Drain, Ratledge, Cleveland, Carver, and B. J. Palmer worked together on chiropractic politics and accreditation.1 Even though they had different perspectives on CVS models, they all shared the chiropractic paradigm developed by D. D. Palmer.

Ratledge’s theories of etiology and adjustment were based on D. D. Palmer’s chiropractic paradigm.3 D. D. Palmer’s final lectures, which were published posthumously as his 1914 book The Chiropractor, were delivered by D. D. Palmer at Ratledge’s school in Los Angeles.101 Ratledge’s ideas about environmental causes of CVS were also congruent with the writings of B. J. Palmer,16 Stephenson,102 Carver,103 Drain,5 Forster,69 and Loban.104 However, Ratledge took this in a new direction. Ratledge developed a distinctly non-Palmer language as a perspective on the universality of matter as central to CVS etiology. For example, he referred to the innate recuperative powers of the body, a universal innateness, but emphasized 3 primary factors of matter: chemical, thermal, and mechanical. These were identified by Ratledge as external causes of CVS as well as body responses. His interpretation of D. D. Palmer’s philosophy led to a view of a “oneness of things.” His non-Palmerian language allowed for a completely different, yet congruent, line of exploration of the chiropractic paradigm.

Ratledge’s theories were further developed by 2 of his students, Paul Smallie, class of 1935, and Henry Higley, class of 1936. Most of Ratledge’s writings were published by Smallie between 1963 and 1979.20, 21, 25, 105, 106, 107 Smallie also started the Worldwide Report on chiropractic and published books on chiropractic theory.25, 107 In 1948 Higley became chairman of the Department of Physiology at Los Angeles Chiropractic College, and in 1958 he was named director of research and statistics of the NCA.29 His theories were published in the 1960s.108, 109 Through the works of Smallie and Higley, many of Ratledge’s ideas were developed further and integrated into the profession.

Ted Schrader, a 1940 RCS graduate, continued Ratledge’s Chiropractic Forum, which lasted until 1956. The forum was the inspiration for the American Chiropractic Association’s Inter-college Council on Technique.110 The Council may have indirectly inspired a journal and several academic textbooks on technique in the 1990s,111 as well as the consensus statement on technique published in 1990.15, 19

Another concept present during this period was that of multiple CVS patterns. B. J. Palmer, Muller, and Watkins each described multiple patterns and prioritized adjustment protocols. During this period, B. J. Palmer expanded his upper-cervical emphasis and included adjustments below axis if the thermographic patterns did not change.32 This change was announced by Himes to the PSC students in the famous “green light speech” of 1955.53 Muller found that priority and force application were dictated by addressing the patterns throughout the spine based on sympathetic and parasympathetic tone.6 Watkins found that multiple CVSs were linked with complex reflex systems.81

Among the many concepts of this period were those of decreased tissue vitality and tonal theories. In the 1930s B. J. Palmer wrote about decreased tissue vitality and tone related to patterns.7 During this era, both Drain and Muller wrote independently of decreased vitality at the segment.5, 6 Muller included the latest models of proprioception and sympatheticotonia.6 This was based in part on his collaborative work with Watkins at CMCC and inspired by Verner.16, 70 Watkins and Verner were both inspired by Heintze in the development of their proprioceptive approaches.16, 112, 113 Muller used Pottenger’s classic text to link D. D. Palmer’s theory of tone to autonomic tone.6 The quote he chose from Pottenger referenced organ tone. It is unlikely that Muller was aware that D. D. Palmer’s earliest writings on chiropractic refer to a case of increased organ tone.114 Those early writings from the Palmer archives were not accessible to the public in 1954 when Muller was writing.

Drain’s ideas relating chiropractic to psychospiritual well-being dates to the earliest writings of the Palmers.5, 28, 64 Verner described how the neurophysiology of CVS could have deleterious psychological and mental effects.70 Muller included an assessment of the psychological tone of the patient along with an assessment of the physiological tone to determine sympathetic or parasympathetic typologies.6 Muller’s inclusion of Selye’s stress response as part of CVS theory is notable as well.6 The effects of CVS on mental and psychological well-being were prominent aspects of chiropractic into the 1970s.115, 116 B. J. Palmer included many elements of psychospiritual health and well-being in his approach to understanding the impact of CVS on all elements of life.41, 42, 43

B. J. had an influence on chiropractic theories during his final years. The bulk of his research was published in 19517 and was discussed throughout his many texts during the 1950s.41, 42, 43 When B. J. Palmer’s clinical findings during this period are mentioned in the literature, it is sometimes dismissed by authors,117 critiquing things such as a lack of research methodology or Palmer’s adherence to his upper cervical approach.56, 118 Although some historical perspectives have been applied to the B. J. Palmer Research Clinic, there has yet to be any systematic analysis of the data collected in the clinic during its active research phase, the dozens of cases he published every year, or the thousands of cases that were cared for with detailed records.52

Not all of the CVS theorists during this period and later were aware of B. J. Palmer’s final writings. This may have been due to school competition, limited self-publishing, or other political factors. For example, during the 1940s and 1950s, B. J. Palmer’s books were not found on other chiropractic campuses, such as TCC or CCC,119, 120 even though the leaders of those schools were originally B. J. Palmer’s students and still taught many of his theories. Furthermore, there was a lack of reference to B. J. Palmer’s works in the literature of this time.6, 70, 84, 93

Nevertheless, B. J.’s impact should not be underestimated considering that in the first 75 years of chiropractic history, approximately 75% of chiropractors graduated from PSC.55 In addition, Drain’s theories were probably based on B. J. Palmer’s early works. He wrote of “mentally directed energy,” and used the 9 functions that Palmer developed in Volume 6 and Firth integrated into Volume 7.5 Drain was influential in chiropractic politics for his entire career.1

Gillet’s fixation model, which developed into the motion palpation paradigm and was integrated into Faye’s vertebral subluxation complex (VSC), was influenced by B. J. Palmer. Gillet studied all of B. J. Palmer’s methods and his first text on his research findings in the clinic, which was published in 1938 as Volume 20.121 A few years later, Gillet reanalyzed the thermographs from this collection of research and used the data to apply B. J. Palmer’s spinographs to his own research.122 Motion palpation and VSC are still taught at many schools. Thus B. J. Palmer’s research and theories can be viewed as part of the foundation of modern practice, including the motion palpation paradigm.

The nonmusculoskeletal effects of the CVS on the central nervous system were central to theories from Janse,123 Muller,6 B. J. Palmer,7 Illi,2 Harper,84 Weiant,83 and R. J. Watkins.8 Their theories and the theories that built on them included specific somatic changes but also global neurological consequences.82, 85, 118, 119, 120, 121, 122 D. D. Palmer’s first adjustments were for visceral complaints, not musculoskeletal complaints.28 Literature reviews that have looked into visceral effects of CVS are varied. Hannon conducted a literature review on positive health benefits of chiropractic adjustments in asymptomatic subjects and concluded that functional health benefits were a measurable outcome of the correction of CVS.124 Rome conducted a literature review and concluded that there is compelling evidence for the neurological basis of somato-autonomic changes from manual manipulative interventions.125 Troyanovich and Troyanovich concluded that there is compelling anecdotal and neuroanatomic evidence for success of “manual methods in treating Type O disorders.”126 Yet they note that a patient’s results are unpredictable and thus studies that demonstrate predictable responses to manual therapies are needed otherwise benefits are best explained as side effects.126

Testing the various hypotheses that may be stated on the basis of many theories from this era may require different research strategies than looking for predictable outcomes for named disease processes. Other outcomes could include those that are functional and physiological, such as neurological assessments that are widely accepted within the scientific community, like heart rate variability and functional magnetic resonance imaging. There are many research questions to still be studied from this era.

Limitations

This paper is based on 1 author’s interpretation of the most extensive evidence available at the time of writing. Future reviews of the literature should include more systematic methods. Without detailed search parameters, inclusion and exclusion criteria, synthesis methods, a standard critical appraisal of the literature reviewed, and evaluation of bias, it is acknowledged that conclusions do need to be made with caution. Because of the difficulties in obtaining primary sources for this type of research, it is possible that this work is missing some important source documents. It is hoped that future researchers will help to fill in gaps in this literature.

Conclusions

A lack of perspective on the development of the history of CVS models has hindered professional discourse and a deep understanding of the foundations of modern practice. By providing a brief history of CVS from this period, I hope that readers might better understand empirical and theoretical roots of current chiropractic theories. By understanding how D. D. Palmer’s chiropractic paradigm was integrated within new theories, a greater appreciation for his original ideas may emerge. The pervasiveness of D. D. Palmer’s theories of this time informs current chiropractic models.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges Brian McAulay, DC, PhD, David Russell, DC, Stevan Walton, DC, and the Tom and Mae Bahan Library at Sherman College of Chiropractic for their assistance.

Funding Sources and Conflicts of Interest

The author received funding from the Association for Reorganizational Healing Practice and the International Chiropractic Pediatric Association for writing this series of papers. No conflicts of interest were reported for this study.

Contributorship

Concept development (provided idea for the research): S.A.S.

Design (planned the methods to generate the results): S.A.S.

Supervision (provided oversight, responsible for organization and implementation, writing of the manuscript): S.A.S.

Data collection/processing (responsible for experiments, patient management, organization, or reporting data): S.A.S.

Analysis/interpretation (responsible for statistical analysis, evaluation, and presentation of the results): S.A.S.

Literature search (performed the literature search): S.A.S.

Writing: (responsible for writing a substantive part of the manuscript) S.A.S.

Critical review: (revised manuscript for intellectual content, this does not relate to spelling and grammar checking) S.A.S.

Practical Applications

-

•

This series of articles provides an interpretation of the history and development of chiropractic vertebral subluxation theories.

-

•

This series aims to assist modern chiropractors to interpret the literature and develop new research plans.

Alt-text: Unlabelled Box

References

- 1.Keating J, Callender A, Cleveland C. Association for the History of Chiropractic; Rock Island, IL: 1998. A History of Chiropractic Education in North America. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Illi F. National College of Chiropractic; Lombard, IL: 1951. The Vertebral Column: Life-line of the Body. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ratledge T. Ratledge; Los Angeles, CA: 1949. The Philosophy of Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palmer BJ. Vol. 39. Palmer School of Chiropractic; Davenport, IA: 1966. Our Masterpiece. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drain J. Standard Print. Co; San Antonio, TX: 1949. Man Tomorrow. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muller RO. The Chiro Publishing Co; Toronto, Ontario, Canada: 1954. Autonomics in Chiropractic: The Control of Autonomic Imbalance. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palmer BJ. Vol. 25. Palmer School of Chiropractic; Davenport, IA: 1951. Clinical Controlled Chiropractic Research. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walton S. The Institute Chiropractic; Asheville, NC: 2017. The Complete Chiropractor: RJ Watkins, DC, PhC, FICC, DACBR. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watkins RJ. Paper presented at: National Chiropractic Association Convention. 1949. Tissue memory in retracing. In: Walton S. The Complete Chiropractor: RJ Watkins, DC, PhC, FICC, DACBR. Asheville, NC: The Institute Chiropractic; 2017:223-226. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Watkins RJ. Sphincterismus and sympatheticotonia: the great American disease. NCA J. November 1951 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luedtke K. Chiropractic definition goes to World Organization. J Am Chiropr Assoc. 1988;25(6):5, 16. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gatterman M. Development of chiropractic nomenclature through consensus. J Man Phys Ther. 1994;17(5):302–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Association of Chiropractic Colleges The ACC chiropractic paradigm. 1996. http://www.chirocolleges.org/resources/chiropractic-paradigm-scope-practice/ Available at:

- 14.Cooperstein R, Gleberzon B. Churchill Livingstone; Philadelphia, PA: 2004. Technique Systems in Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bergmann T. Proceedings of the first Consensus Conference on Validation of Chiropractic Methods. J Chiropr Technique. 1990;2(3):71–161. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Palmer BJ. Vol. 22. Palmer School of Chiropractic; Davenport, IA: 1949. The Bigness of the Fellow Within. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sinnott R. Chiropractic Books; Mokena, IL: 1997. The Greenbooks: A Collection of Timeless Chiropractic Works—By Those Who Lived It! [Google Scholar]

- 18.Villaneuva-Russell Y. Graduate School, University of Missouri; Columbia, MO: 2002. On the Margins of the System of Professions: Entrepreneurialism and Professionalism as Forces Upon and Within Chiropractic. [dissertation]. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keating J, Brown R, Smallie P. One of the roots of straight chiropractic: Tullius de Florence Ratledge. In: Sweere J, editor. Chiropractic Family Practice: A Clinical Manual. Aspen Publishers; Gaithersburg, MD: 1992. pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smallie P. Self-published; 1963. The Guiding Light of Ratledge. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smallie P, Ratledge TF. World-Wide Books; Stockton, CA: 1990. Introduction to Ratledge Files and Ratledge Manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keating J, Davison R. That down in Dixie school: Texas Chiropractic College, between the wars. Chiropr Hist. 1997;17:17–36. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Janse J. In memoriam: Fred W. Illi passes away. ACA J Chiropr. January 1984:94–95. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keating J, Brown R, Smallie P. TF. TF Ratledge, the missionary of straight chiropractic in California. Chiropr Hist. 1991;11(2):27–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smallie P, Ratledge T. 2nd ed. Vol. 1. Integral Altitude, Inc; Asheville, NC: 2014. Ratledge philosophy. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Worldcat. www.worldcat.org/title/philosophy-of-chiropractic Available at: Accessed September 17, 2016.

- 27.Higley H. Chiropractic philosophy: an interesting interpretation of basic tenets. Chiropr J. February 1938:13–14. 54-55. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Palmer DD. Portland Printing House; Portland, OR: 1910. The Science, Art, and Philosophy of Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rehm W. Necrology. In: Dzaman F, editor. Who's Who in Chiropractic International. 2nd ed. Who's Who in Chiropractic International Publishing Co; Littleton, CO: 1980. pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Drain JR. Part 2 of chiropractic thoughts. 2nd ed. 1946. In: Drain JR, editor. Mind and My Pencil. Integral Altitude Inc; Asheville, NC: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Drain JR. Cleveland Chiropractic College Archives; Cleveland, OH: 1956. We Walk Again. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Palmer BJ. Vol. 35. Palmer School of Chiropractic; Davenport, IA: 1957. History in the Making. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Palmer BJ. Vol. 23. Palmer College; Davenport, IA: 1950. Up From Below the Bottom. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Palmer BJ. Vol. 24. Palmer College; Davenport, IA: 1950. Fight to Climb. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Palmer BJ. Vol. 26. Palmer College; Davenport, IA: 1951. Conflicts Clarify. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Palmer BJ. Vol. 27. Palmer College; Davenport, IA: 1951. History Repeats. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Palmer BJ. Vol. 28. Palmer College; Davenport, IA: 1952. Answers. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Palmer BJ. Vol. 29. Palmer College; Davenport, IA: 1953. Upside Down Inside Out With B.J. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Palmer BJ. Vol. 32. Palmer College; Davenport, IA: 1955. Chiropractic Philosophy. Science, and Art: What It Does, How It Does It, and Why It Does It. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Palmer BJ. Vol. 33. Palmer College; Davenport, IA: 1955. Fame and Fortune. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Palmer BJ. Vol. 34. Palmer College; Davenport, IA: 1957. Evolution or Revolution. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Palmer BJ. Vol. 36. Palmer College; Davenport, IA: 1958. Palmer’s Law of Life. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Palmer BJ. Vol. 37. Palmer College; Davenport, IA: 1961. The Glory of Going On. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Palmer BJ. Vol. 38. Palmer College; Davenport, IA: 1966. The Great Divide. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Senzon S. A history of the mental impulse: theoretical construct or scientific reality? Chiropr Hist. 2001;21(2):63–76. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Senzon S. Chiropractic and energy medicine: a shared history. J Chiropr Humanit. 2008;15:27–54. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Senzon S. BJ Palmer: an integral biography. J Integral Theory Pract. 2010;5(3):118–136. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Erickson N. Electroencephaloneuromentimograph. Chiropr Hist. 2002;22(2):31–44. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Coxon VG. Trust nature. Chiropractor. 1938;34(12):4. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Coxon VG. Sincerity of purpose. Chiropractor. 1939;35(4):6. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Killinger L. The resurrection of the B.J. Palmer Clinic research: a personal view. Chiropr Hist. 1998;18(1):53–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Palmer BJ. Chiropractic principle and practice. Chiropractor. 1945;50(8) [Google Scholar]

- 53.Himes M. Policy talk. In: Faulkner T, Foley J, Senzon S, editors. Palmer Chiropractic Green Books: The Definitive Guide. Asheville, NC:The Institute Chiropractic; 2018. pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Eriksen K, Grostic R. History of the Grostic/orthospinology procedure. In: Eriksen K, Rochester R, Grostick J, editors. Orthospinology Procedures: An Evidence-Based Approach to Spinal Care. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; Philadelphia, PA: 2007. pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Keating J. Association for the History of Chiropractic; Davenport, IA: 1997. B.J. of Davenport: The Early Years of Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Haldeman S, Hammerich K. The evolution of neurology and the concept of chiropractic. ACA J Chiropr. 1973;VII(S-57):60. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Quigley W. The last days of B.J. Palmer: revolutionary confronts reality. Chiropr Hist. 1989;9(2):11–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Palmer BJ. Vol. 2. Palmer School of Chiropractic; Davenport, IA: 1907. The Science of Chiropractic: Eleven Physiological Lectures. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Palmer BJ. Vol. 19. Palmer School of Chiropractic; Davenport, IA: 1936. The Known Man or an Explanation of the “Phenomenon of Life.”. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Crile GW. A bipolar theory of the nature of cancer: presidential address, American Surgical Association, April 17, 1924. Ann Surg. 1924;80(3):289. doi: 10.1097/00000658-192409000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Speransky A. A Basis for the Theory of Medicine. International Publishers; New York, NY: 1936. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Morat JP. Archibeld Constable; London, UK: 1906. Physiology of the Nervous System. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Crile GW. The Macmillan Co; New York, NY: 1926. The Bipolar Theory of Living Processes. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Palmer BJ. Vol. 5. Palmer School of Chiropractic; Davenport. IA: 1909. Philosophy of Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Maslow A. D. Van Nostrand Co; New York, NY: 1968. Toward a Psychology of Being. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Taylor E. Counterpoint; Washington, DC: 1999. Shadow Culture: Psychology and Spirituality in America. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wilber K, Engler J, Brown B. New Science Library; Boston, MA: 1986. Transformations of Consciousness. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Firth JN. J.N. Firth; Indianapolis, IN: 1948. Text-book on Chiropractic Diagnosis. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Forster A. 3rd ed. The National Publishing Association; Chicago, IL: 1923. Principles and Practice of Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Verner J. 8th ed. Dr. P.J. Cerasoli; Brooklyn, NY: 1956. The Science and Logic of Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pottenger F. Mosby; St. Louis, MO: 1953. Symptoms of Visceral Disease: A Study of the Vegetative Nervous System in its Relationship to Clinical Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Selye H. McGraw-Hill; New York, NY: 1956. Stress and Disease. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Selye H. The stress concept in 1955. J Chronic Dis. 1955;2(5):583–592. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(55)90155-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Selye H, Horava A. The third annual report on stress. Am J Med Sci. 1954;228(2):249. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Selye H, Heuser G. Acta; Montreal, QC, Canada: 1954. Fourth Annual Report on Stress. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Selye H. Stress and the general adaptation syndrome. BMJ Br Med J. 1950;1(4667):1383. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.4667.1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Del Pino M. Questions and comment regarding research of Dr. Hans Selye. Chiropractor. 1955;51(2):12. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Still AT. 1910. The A.T. Still research institute. Bulletin No. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tissot J. Muséum d'histoire naturelle; Paris, France: 1946. Constitution des Organismes Animaux et Végétaux: Causes des Maladies qui les Atteignent. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Verner J, Weiant C, Watkins RJ. 2nd ed. Weiant; Peekskill, NY: 1953. Rational Bacteriology. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Watkins RJ. Side effects of subluxations. Digest Chiropr Econ. February 1982 In: Walton S. The Complete Chiropractor: RJ Watkins, DC, PhC, FICC, DACBR. Asheville, NC: The Institute Chiropractic; 2017:281-288. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Baker J. Fred W.H. Illi, DC (1901-1981): A clinical reformation in chiropractic. J Am Chiro Assoc. June 1997:53–56. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Weiant C. Chiropractic Institute; New York, NY: 1958. Medicine and Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Harper W. Clarifying the term “irritation” and its relationship to the chiropractic premise. J Natl Chiropr Assoc. 1954;11:9–11. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Palmer DD, Palmer BJ. The Palmer School of Chiropractic; Davenport, IA: 1906. The Science of Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Palmer DD. Press of Beacon Light Printing Co; Los Angeles, CA: 1914. The Chiropractor. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Google books Ngramviewer: functionating 2016. https://books.google.com/ngrams Available at:

- 88.Palmer DD. The Burlington Daily Hawkeye: Sunday Morning; October 9, 1887. Cured by magnetism. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Masarsky C, Todres-Masarsky M. Churchill Livingstone; New York, NY: 2001. Somatovisceral Aspects of Chiropractic: An Evidence-Based Approach. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Goldstein M. Vol. 15. U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare; Bethesda, MD: 1975. The Research Status of Spinal Manipulative Therapy: A Workshop Held at the National Institutes of Health, February 2-4, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Speransky A. 2nd ed. International Publishers Co; New York, NY: 1943. A Basis for the Theory of Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Janse J. National College of Chiropractic; Lombard, IL: 1976. Principles and Practice of Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Homewood AE. 3rd ed. Homewood; 1981. The Neurodynamics of the Vertebral Subluxation. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Drum D. The vertebral motor unit and intervertebral foramen. In: Goldstein M, editor. The Research Status of Spinal Manipulative Therapy: A Workshop Held at the National Institutes of Health, February 2-4, 1975. Vol. 15. U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare; Bethesda, MD: 1975. pp. 63–75. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lantz C. Vertebral subluxation chiropractic. Top Clin Chiropr. 1995;2(2):1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ward L. 3rd ed. SSS Press; Long Beach, CA: 1980. The Dynamics of Spinal Stress: Spinal Column Stressology. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Weiant C. September 1954. National Chiropractic Association: Healthways Magazine. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hviid H. A consideration of contemporary chiropractic theory. J Natl Chiropr Assoc. January 1955;17-18:68. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Cleveland C. Cleveland Chiropractic College; Kansas City, MO: 1951. Chiropractic Analysis: Symptomatology Outline. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Agocs S. Cleveland's rabbis: The use of animals to study vertebral subluxation. Chiropr Hist. 2016;36(1):63–69. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Foley J. The chiropractor 1914: revealed. Chiropr Hist. 2016;36(1):72–86. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Stephenson R. Vol. 14. Palmer School of Chiropractic; Davenport, IA: 1927. Chiropractic Textbook. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Carver W. 2nd ed. National Institute of Chiropractic Research; Phoenix, AZ: 2002. History of Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Loban J. 2nd ed. Loban Publishing Co; 1915. Technic and Practice of Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Smallie P. World-Wide Books; Stockton, CA: 1984. Scientific Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Smallie P. World-Wide Books; Stockton, CA: 1988. The Opening of the Chiropractic Mind. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Smallie P. 2nd ed. Vol. II. Integral Altitude, Inc.; Asheville, NC: 2014. Ratledge Philosophy. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Higley H, Rich E, Goodrich T. Foundation for Chirorpactic Education and Research; Carmichael, CA: 1968. Report of a Study of Spinal Mechanics L-3, L-4, L-5. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Higley H, Rich E, Goodrich T. Foundation for Chirorpactic Education and Research; Carmichael, CA: 1967. Lumbo-sacral Spine Facet Facings. [Google Scholar]

- 110.Keating J. National Institute of Chiropractic Research; Phoenix, AZ: 2004. Chronology of Tullius de Florence Ratledge, DC and the Cleveland Chirorpactic College of Los Angeles. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Green B, Johnson C, Keating J, Ted L, Shrader DC. FICC: a gentle force for improvement in chiropractic. 1998 Lee-Homewood Chiropractic Heritage Award recipient. Chiropr Hist. 1998;18(1):59–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Verner J. Venard Press; Closter, NJ: 1939. The Science of Chiropractic and Its Proper Place in the New Health Era. [Google Scholar]

- 113.Heintze A. The proprioceptive faculty: a broader theory of chiropractic is indicated. The Chiropractic Journal. February 1937:11, 44. [Google Scholar]

- 114.Palmer DD. January 1897. The Chiropractic. (Number 17) [Google Scholar]

- 115.Schwartz H. Sessions Publishers; New York, NY: 1973. Mental Health and Chiropractic: A Multidisciplinary Approach. [Google Scholar]

- 116.Hynes R. Chiropractic's foray into mental health. Chiropr Hist. 2008;28(2):61–70. [Google Scholar]

- 117.McAulay B. Rigor in the philosophy of chiropractic: beyond the dismissivism/authoritarian polemic. J Chiropr Humanit. 2005;12:16–32. [Google Scholar]

- 118.Keating J. Stockton Foundation for Chiropractic Research; Stockton, CA: 1992. Toward a Philosophy of the Science of Chiropractic: A Primer for Clinicians. [Google Scholar]

- 119.Russell J. 2014. Interview with Simon Senzon. Available at: www.institutechiro.com. Accessed November 24, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 120.Kaufman J. 2016. Interview with Simon Senzon. Available at: www.institutechiro.com. Accessed November 24, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 121.Palmer BJ. Vol. 20. Palmer School of Chiropractic; Davenport, IA: 1938. Precise, Posture-Constant, Spinograph, Comparative Graphs. [Google Scholar]

- 122.Gillet H. The evolution of a chiropractor. Natl Chiropr J. November 1945:15–19. 54-55. [Google Scholar]

- 123.Janse J, Houser RH, Wells BF. 2nd ed. National College of Chiropractic; Chicago, IL: 1978. Chiropractic Principles and Technic: For Use By Students and Practitioners. [Google Scholar]

- 124.Hannon S. Objective physiologic changes and associated health benefits of chiropractic adjustments in asymptomatic subjects: a review of the literature. J Vert Subl Res. 2004:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 125.Rome P. Neurovertebral influence upon the autonomic nervous system: some of the somato-autonomic evidence to date. Chiropr J Aust. 2009;39(1):2. [Google Scholar]

- 126.Troyanovich S, Troyanovich J. Chiropractic and type O (organic) disorders: historical development and current thought. Chiropr Hist. 2012;32(1):59–72. [Google Scholar]