Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this paper is to review and discuss the history of chiropractic vertebral subluxation (CVS) between 1908 and 1915.

Discussion

Evidence from the works of Daniel D. Palmer, Bartlett J. Palmer, Joy Loban, Willard Carver, James Firth, Alva Gregory, John Howard, Arthur Forster, and Harold Swanberg demonstrates that chiropractic during this period was characterized by increasingly complex theories of CVS, which contributed to defining the profession. Critiques of CVS as a central identifier of the profession begin with this early period when students of D. D. Palmer’s early graduates became school leaders and theorists. Textbooks were self-published during this period, including D. D. Palmer’s final works, 4 books from his son B. J. Palmer, and texts from their students. Chiropractic graduates of subsequent schools also contributed to emerging writings and concepts. Chiropractic vertebral subluxation was central to nearly all texts and schools. There was disagreement about what defined chiropractic, and various schools taught different practices. However, the theories from this period had an important role in the evolution of thought in the profession.

Conclusion

Theories presented from 1908 through 1915 built upon previous concepts from earlier years of chiropractic. The plethora of books and ideas about CVS from these early pioneers shaped the profession, and some of these viewpoints still have relevance today.

Key Indexing Terms: Chiropractic, History

Introduction

The period from 1908 to 1915 was foundational for the development of chiropractic vertebral subluxation (CVS) theory. Models grew in complexity, and chiropractors extensively discussed CVS concepts in various publications. Leaders from major chiropractic schools advocated that CVS was central to the identity of the profession.

In 1911, Joy Loban wrote that chiropractors had CVS as common ground.1 Even though Daniel D. Palmer was still alive and a book listing him as the sole author was published,2 Loban suggested there was no authority figure in chiropractic and that the leaders of the profession needed to figure it out for themselves.1 Loban wrote, “Subluxation Theory – it is Common Ground from it we trace our diverging paths ... By this central theme advanced by the earliest Chiropractors and since used by all as a basis for all we have, we stand or fall.”1

The period between 1908 and 1915 was characterized by a flourishing publication of books.2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 Two books of D. D. Palmer’s were published during this time, one posthumously.2, 3 Several of his students published books, and now a third wave of graduates contributed to the literature.8, 12, 15, 16, 17 This was the start of a tradition of CVS modeling. Authors integrated ideas from their teachers and other texts, along with empirical observations from clinical practice and early attempts at research.4, 7, 15 The object of the books was to teach students and to further substantiate chiropractic.18 The results of these efforts were self-published textbooks with new and more complex models of CVS resulting in the emergence of an early identity for the profession. The aim of this paper is to review and discuss the history of CVS in the chiropractic profession between the years 1908 and 1915. This article also explores the later theories of D. D. Palmer; several models of Bartlett J. Palmer; the theories of John Howard, Willard Carver, Alva Gregory, Loban, James Firth, and Arthur Forster; and the research of Harold Swanberg.

Discussion

Theories Between 1908 and 1915

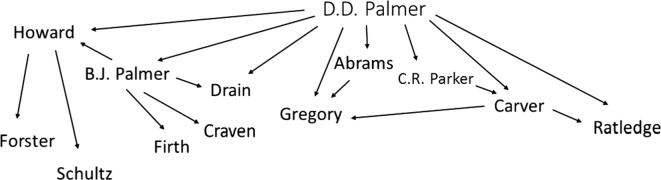

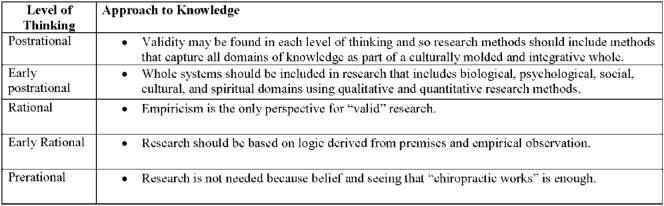

New subluxation theorists emerged during the 1908 to 1915 period (Fig 1).18, 19 In addition to the innovations of D. D. Palmer and B. J. Palmer, their students made contributions. Some students of B. J. Palmer’s became leading educators and theorists, such as Joy Loban,1, 20 John Craven,21 and James Firth, who authored the first text on diagnosis in chiropractic.17 Each expanded upon B. J. Palmer’s ideas. Willard Carver developed his own CVS theories based on decades of interaction with the Palmers and his lectures at the Carver-Denny School of Chiropractic.12, 22 Alva Gregory developed his lectures into a series of texts.8, 9, 10, 11 He merged the ideas from Carver and D. D. Palmer with his medical training along with Abrams’ Spondylotherapy.19 John Howard integrated ideas from his own clinical training in naturopathy and hydrotherapy with ideas from the Palmers,23 Davis,24 and Modernized Chiropractic.14, 25 Arthur Forster was originally trained as a surgeon.26 In his writings, he integrated his medical training along with theories from all of the previous chiropractic literature, including B. J. Palmer’s texts.15 Forster dissected cadavers at National School of Chiropractic (NSC) as part of his empirical research to understand CVS.15 Swanberg was a student of O. G. Smith, who conducted the first dissections of intervertebral foramina. Swanberg built upon Smith’s research.27 His empirical research influenced the profession for decades. Each of these individuals influenced the first generation of chiropractors in significant ways.

Fig 1.

The teacher-student relationships between subluxation theorists 1908-1915. Abrams did not study with D. D. Palmer, but he did reference D. D. Palmer’s 1910 book and used Palmer’s images of subluxated vertebra. Carver, Ratledge, and Drain learned from D. D. Palmer but did not graduate from one of his schools.

Even though the CVS theorists were developing their own separate definitions of chiropractic based on their previous perspectives about health, healing, and eclectic medical approaches, there was a common core conveyed in their writings. Different philosophical and theoretical language was used to describe CVS in each school,2, 6, 12, 14, 15, 16 yet chiropractors from every school viewed CVS as a primary or secondary contributor to disease processes.2, 9, 12, 14, 15, 16

D. D. Palmer’s Theories (1908-1913)

D. D. Palmer’s CVS models during this time were based on his initial theories as the founder of chiropractic and informed by his clinical practice and extensive study of the anatomy, physiology, and surgery literature.23, 28 Many of his thoughts on chiropractic were developed and refined in response to other chiropractors as well as the development of his courses.2, 3, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33

From 1908 until his final writings in 1913, D. D. Palmer expanded on his theories.2, 34 Much of his final theory development was stimulated by competing ideas from his students, including his son, B. J. Palmer2 (Fig 2). Some of D. D. Palmer’s new ideas were a response to B. J. Palmer’s articles and his first 2 books.4, 34, 35, 36 D. D. Palmer lived in Portland, Oregon from late 1908 to early 1911, and he read and commented on his son’s books during this time. D. D. Palmer also developed his own ideas by answering questions publicly in his writings, critiquing other authors, and interviewing chiropractors about their ideas.2 During this time, D. D. Palmer published a new publication that he called The Chiropractor Adjuster, apparently named so that he could adjust misconceptions about chiropractic.37 The articles from the publication were reprinted as chapters of his 1910 book, which was called The Textbook of the Science, Art, and Philosophy of Chiropractic, with “The Chiropractor’s Adjuster” printed on the spine.2

Fig 2.

B. J. Palmer. Courtesy of Special Services, Palmer College of Chiropractic.

D. D. Palmer strongly suggested that B. J. Palmer was too reliant on the nerve compression model. This inspired D. D. Palmer to clarify what he meant by “impingement” and to refine his theory.2 He also distanced his theories from B. J.’s new ideas about interference to the transmission of currents at the intervertebral foramina.4, 35 D. D. made clear that his view was that spinal nerves were not blocked or obstructed by being constricted. Rather, he felt they were impinged or pressed against by subluxated joints, which irritated the nerve, causing too much or not enough function.37 His impingement theory can be traced back to at least 1902 and was later developed based on references in the literature.2, 28, 38, 39 D. D. Palmer viewed disease as modified physiology. By 1910, he defined normal function as “tone.”2 This definition built upon his first writings on healthy organ tone from 1896 and normal function from 1899.40, 41

By 1910, D. D. Palmer introduced his model of the neuroskeleton as a regulator of “tension,” which was his latest evolution of his theory of tone that originated from the 1890s. He wrote, “Chiropractic is founded on tone.”2 Between 1911 and his death in 1913, he expanded on his theories in a series of lectures, which were published posthumously.29 D. D. wrote that a subluxated joint impinged upon nerves and caused tension. Tension was described in terms of tone, vigor, or “renitency” of the tissues.3

In a letter to a chiropractor dated 1 month before his death, D. D. Palmer included his thoughts on chiropractic. He wrote, “Chiropractic is the Science (knowledge) of the principles which compose the scientific portion of chiropractic. Chiropractic is divided into 3 grand divisions, the Science, the Art, and the Philosophy. The Art is subdivided in Palpation, nerve-tracing and adjusting… Nerves are stretched -- tension my boy causes 99 per cent of all diseases.”29 This statement summed up his practice and theory that had consistently developed since the late 1890s, when he first wrote about nerve tracing, stretched nerves, tone, palpation, and adjusting.41, 42, 43

D. D. worked on a vibration theory from 1908 through 1910. It is unknown who the true originator of the vibration theory was, although D. D. Palmer claimed the distinction.2 His first use of the term found in the literature is from March 1909. However, in that he quotes weekly output of The Palmer School, published by B. J. Palmer on December 17, 1908.44 D. D. Palmer’s second use of “vibration” was in December 1909 in critique of Joy Loban’s article on the philosophy of chiropractic,35 which was published in August 1908.20 Loban was a student of B. J. Palmer and wrote in the article, “Candor compels me to state that I have quoted freely from the utterances of B. J. Palmer.”20, 45 D. D. Palmer’s critique of Loban was updated in his 1910 book.2 D. D. Palmer wrote that Loban “… has attempted to make use of the molecular vibration theory lately put forth by the Founder of the science.”2 Based on reviewing dates of each author’s publication, it is possible that B. J. Palmer was the first to introduce vibration theory into chiropractic. B. J. Palmer used the term vibration 107 times in his compilation of lectures from winter 1908, published as Philosophy of Chiropractic, Volume 5.6 Comparatively, D. D. Palmer used the term vibration 163 times in his 1910 tome.2 No matter who used it first, each developed distinctly different theories and cited different references, which could account for much of D. D. Palmer’s dislike for B. J.’s new theories about currents over nerves.2 B. J. emphasized the physics literature and Morat’s neurophysiology,47, 48 whereas D. D. Palmer’s model was based on his study of the literature on magnetic healing, anatomy, and physiology.2, 6 Howard also lectured about vibration as part of his philosophy of chiropractic during this period.14

B. J. Palmer’s Theories (1908-1909)

B. J. Palmer’s ideas published between 1907 and 1909 formed the foundation of his CVS theories.6, 35 His theories were based on his father’s initial models, an extensive osteological lab, and coupled to his school clinic, which was a primary source for his new ideas.4, 5, 6, 7, 17, 23, 35, 48, 49, 50 B. J. developed lectures and clinical protocols after he assumed leadership of Palmer School of Chiropractic (PSC) in 1906.50 His new innovations of CVS theory during this period were developed in response to criticisms from his father2; competition with his peers18; and reviews of anatomical, physiological, and electrical literature.6, 35, 47, 51, 52

B. J. may have been the first to posit the idea that CVS may interfere with the transmission of organizing information traveling along nerves.35 This differed from D. D. Palmer’s favored theory that the information, energy, and vibration of the nerves was modified by CVS, causing too much or not enough function.2 For D. D. Palmer, interference related to function, not to transmission.2 B. J. Palmer described a spectrum of paralysis associated with CVS and interference. On one end of the spectrum was total paralysis of function of muscles and organs. In the middle of the spectrum were variations of partial paralysis. On the other end was what might be referred to today as psychospiritual paralysis. He referred to this as the inability to live life fully and related it directly to CVS.6

In the winter of 1908, B. J. Palmer expanded his theories.6 He hypothesized that the nervous system uses energy from the environment and converts it into intellectual energy used by the body as function. He suggested that this input was received by the afferent system as raw units of force or power, which traveled to the brain where it was transformed into energy imbued with intelligence. The intelligently informed impulse was then transmitted to the tissue cell as power for action. The transmission could be interfered with by CVS.6 This new theory was an expansion of his cycle of life theory from 1907 combined with his studies of electricity and biology.6, 35 His writings on power and energy referenced articles from the 10th edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica written by physicists from St. John’s College and the University of St. Andrews.46

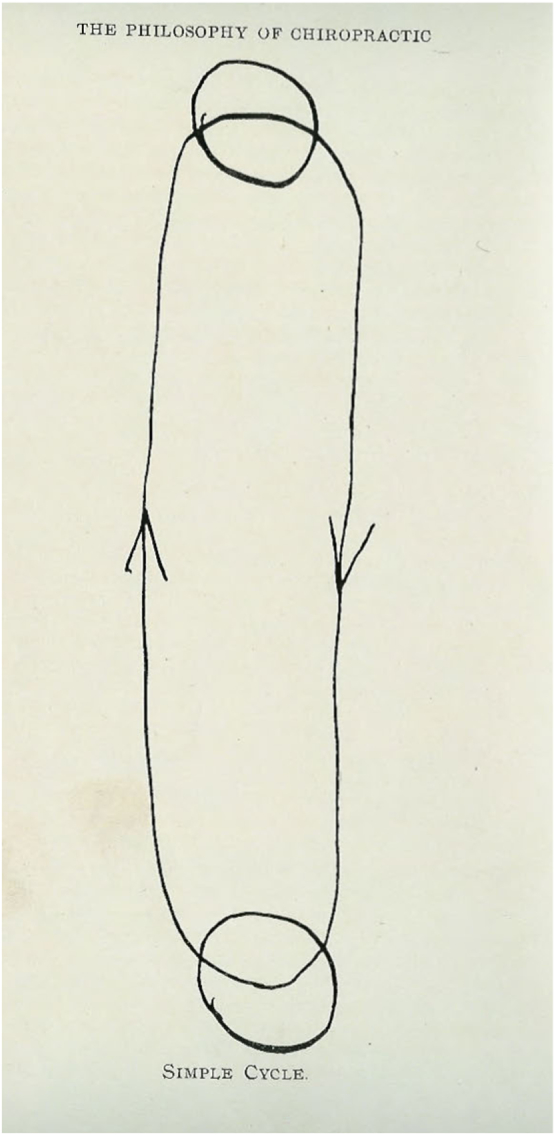

From these theories, B. J. Palmer developed the 31 steps of the Normal Complete Cycle.6 This cycle included the afferent and efferent aspects of the transmission of information and energy between the tissue cells and the brain cells (Fig 3).6 It was set in the context of his wider philosophy about the expression of intelligence through matter, which was developed from his father’s philosophical theories going back to 1903 and earlier.38, 53, 54 The Normal Complete Cycle was developed further and is still being interpreted and reinterpreted today.55, 56, 57, 58 In 1909, B. J. published The Philosophy of Chiropractic, Volume 5 and traveled to deliver his lecture on the Normal Complete Cycle.6 The ideas were received enthusiastically in the field.59 These lectures were his first of many speaking tours around the United States and may have affected early chiropractic theory in many ways.6

Fig 3.

The simple cycle from B. J. Palmer.

In 1910, B. J. Palmer brought x-ray technology into chiropractic and developed the concept of retracing.48, 60 He introduced his cord pressure model of CVS in 1911,51 and his theory of momentum of ease and “dis-ease” in 1913.49 Retracing was developed from D. D. Palmer’s ideas.23 However, it was named and developed by B. J. Palmer.6, 23 Retracing was later expanded upon by various thought leaders from every era and many schools, such as Loban,61 Drain,62 Watkins,63 Janse,64, 65 Napolitano,66 Ward,67 Strauss,68 Epstein,69 Filippi,70 and Sinnott.57 B. J. Palmer’s students, such as Craven,21, 72, 73 Firth,17 Drain,63 and Stephenson, further developed B. J.’s theories and models.56

B. J. Palmer added a chapter on cord pressures to his second edition of The Philosophy and Principles of Chiropractic Adjustments, Volume 3.17, 51 To support his theory of cord pressure-based CVS, he cited a 1910 article published in The Journal of the American Medical Association that was written by a Canadian surgeon named Primrose.52 B. J. reproduced the article in his book, which included 14 cases, and italicized points that were the basis for his extension of Primrose’s cord compression theory to CVS.51

It is possible that B. J. Palmer may have added cord pressures to his model in 1911 as a response to D. D. Palmer’s 1909 criticism.36 As noted earlier, D. D. critiqued B. J.’s over-reliance on intervertebral foramina (IVF) compression theory.75 According to D. D. Palmer, the theory that nerves pinched at the IVF did not account for pressure and impingement at the upper cervical spine, the sacrum, and the feet.17, 36 The second edition of Vol. 3 was copyrighted on June 9, 1911.74 In that edition of the book, B. J. wrote that even though “this idea was first considered 2 years ago it did not have its public introduction, Chiropractically, until last winter.”51 Thus, B. J. introduced the concept soon after D. D.’s critiques, which D. D. sent to Davenport.75

B. J. concluded that cord pressure caused by CVS may diminish lumen, reduce strength and quantity of mental impulse conduction, and lead to some level of paralysis. He felt that cord pressures occurred frequently.17 Interestingly, almost 70 years later, neurosurgeon Alf Breig demonstrated that adverse mechanical tension on the spinal cord reduced conductivity.76

John Howard’s Theory (1908-1912)

John Howard was a 1906 graduate from PSC26 and studied under D. D. Palmer (Fig 4). Howard opened the NSC in Davenport that same year and shortly thereafter left Davenport.50 Between 1908 and 1910, Howard delivered a series of lectures at the NSC, which were then developed into his 3-volume Encyclopedia of Chiropractic (The Howard System). It included a wide variety of natural remedies; however, CVS correction was at the core of his system.14 He pioneered what I have called the middle-chiropractic paradigm, which was the inclusion of natural remedies to support and supplement CVS correction (Fig 4).77

Fig 4.

John F. A. Howard. Courtesy of Special Services, Palmer College of Chiropractic.

Before studying chiropractic, Howard studied Kneipp’s water therapy and managed patient care at the Salt Lake Sanitarium in Utah, alongside medical doctors Miller and Gowen.78 While in Davenport, he interned at Benadom’s sanitarium and later learned physical therapeutics from William Schulze, MD, who bought NSC from Howard and introduced physical therapeutics to the chiropractic profession.79

Zarbuck observed that Howard used ideas from the Palmers, Davis, Smith, and Langworthy.80, 81 Howard proposed that CVS was often the primary cause of diseases, though sometimes it was secondary to other conditions, such as environment, hygiene, diet, and poisons.14 These causes could lead to spasm and rigidity of muscles and ligaments, which affected the integrity of the spinal column, causing unequal tension and subluxated vertebra. Chiropractic vertebral subluxation led to a loss of integrity in the central nervous system. He wrote, “[In] each case find out to what extent the functional integrity of the spinal cord is responsible for the disorder or the disease.”14 Howard may have been the first to write about neural and spinal cord integrity in the chiropractic profession.

Howard proposed that CVS directly or indirectly caused 90% of the “ailments, diseases and deformities of the body,” which he considered a “conservative estimate.”14 Howard reasoned that an impinged nerve would change the vibration of nerve force to an organ by degree depending on the amount of pressure and how long it has been impinged. This may not present as a symptom until the vibration was lowered enough to cause functional abnormality. He wrote, “No longer do we need to inquire as to what has happened; the vibrations of the organ have been disturbed, changed from normal to abnormal, and this means disharmony, disease, death.”14 Howard posited that CVS could last for a long time with no other outward symptom besides some discomfort. He also felt that the chiropractic adjustment released the pressure and allowed the vitality to flow back to the affected organ, which led to normal vibration and the restoration of equilibrium and “perfect health.”14

Carver’s Theory (1909-1915)

Willard Carver was another early chiropractic educational leader (Fig 5). He graduated from C. R. Parker’s school in 1905 but had been involved with the Palmers for decades.18 Carver claimed to have already been contemplating the science of chiropractic for 10 years before earning his degree.22 Like D. D. Palmer, Carver felt that disease or “dis-ease” really meant abnormal function. Removing the cause that was irritating the nervous system allowed for normal processes to ensue.12 Carver developed the concepts of postural distortion, multiple subluxations, and full-spine adjusting.82 He originated the structural approach and emphasized looking at overall spinal posture and curves that created stress points or “disrelationships.”83

Fig 5.

Willard Carver. Courtesy of Special Services, Palmer College of Chiropractic.

Gregory’s Theory (1910-1913)

Alva Gregory was a medical doctor investigating natural methods when he completed his chiropractic degree at the Carver-Denny School of Chiropractic in Oklahoma City in 1907 (Fig 6).18

Fig 6.

D. D. Palmer with Alva Gregory.

In 1907, D. D. Palmer and Alva Gregory incorporated as the Palmer-Gregory School and were business partners for 3 months.18 Even though the partnership dissolved, Gregory kept the Palmer name on the school and the corporate charter for years.84 D. D. Palmer left Oklahoma in 1908 and started a school in Oregon. While in Oregon, D. D. wrote:

If Dr. D. D. Palmer’s connection with the Gregory School as a teacher for nine weeks is of such importance as to justify the continuance of advertising “Palmer-Gregory Chiropractic College,” how much more is it worth to you as a student to be under the personal instruction of D. D. Palmer for nine months? During that nine weeks much of my Chiropractic teaching was sidetracked, owing to the teaching of medical ideas which were not Chiropractic.85

Gregory found Palmer’s theories and methods relevant for medical practice.8 He led an early movement in the United States to merge the orthodox medicine and chiropractic paradigms.18 This was different than Schulze and Howard’s approach, which was to include many alternative methods including physical therapy as part of chiropractic or the middle-chiropractic paradigm.77 To Gregory, spinal adjusting was an adjunct to all drugless methods of healing, such as fasting, dieting, suggestion, elimination, spondylotherapy, rectal dilation, and physical culture.10 Spondylotherapy was developed by Albert Abrams,19 a famous medical doctor.86 Abrams considered spondylotherapy to be an evolution of osteopathy and chiropractic. Gregory also incorporated theories from Smith, Langworthy, and Davis.8

Gregory concluded that CVS was due to contracted muscles, tight ligaments, and “settlement” or compression of the spine.11 He emphasized mobilizing the spine to open articulations because CVS caused restricted motion. Gregory suggested that the role of the adjustment was to stimulate action of depressed nerves or remove interference. His emphasis was dilation or constriction of various nerve centers. He called his overall practice Rational Therapy.10

Joy Loban’s Theory (1912-1915)

Joy Loban was a 1908 graduate of PSC,45 during which time B. J. Palmer was president. Loban took over the philosophy department for a short time and edited The Chiropractor.50 By 1915, he was head of the Universal Chiropractic College, which was also in Davenport. After he left PSC, Loban and B. J. Palmer had a falling-out. It was once reported that this was over B. J. Palmer’s introduction of x-ray technology into chiropractic, but there is no credible proof to support that hypothesis.26

Loban (Fig 7) published the second edition of his 1912 book, Technic and Practice of Chiropractic (Fig 7).16 In the book, Loban wrote that vital energy travels over the nervous system as a third form of energy, which was different from inhibition or stimulation.16 He concluded that irritations to the nervous system affected the interconnected whole of the system and that stimulation or inhibition of one part may affect a distant part. Loban proposed that all disease was related to the nervous system, which organized the body and communicated by “contact,” and suggested that the nervous system was stimulated or inhibited by “irritability.”16

Fig 7.

Joy Loban.

According to Loban, CVS affected the nervous system and was always found in conjunction with a disease process. There may be secondary causes, such as germs, toxins, and exposure, but the CVS was always a cause.16 One of Loban’s most well-known quotes from the 1920s is in relation to the concussion of forces that cause CVS. He wrote, “It is this failure of Nature to make man adaptable to every untoward circumstance which renders him susceptible to disease.”45 Loban suggested several experiments to test the CVS hypothesis, from animal studies to refining adjusting techniques.16

Firth’s Diagnostic Approach (1914)

In 1914, James Firth published Chiropractic Symptomatology or the Manifestations of Incoordination Considered from a Chiropractic Standpoint, based on his lectures at PSC (Fig 8).88 The book included his monthly articles from The Chiropractor, which started in December 1913, along with dozens of new chapters.88, 89, 90, 91, 92 It was the first book published at PSC that was not written by the Palmers. It was also the first book to apply B. J. Palmer’s theories on retracing, momentum, subluxation, nerve tracing, his circuit theory, diagnosis and symptomatology. The book went into 5 editions through 1948 (Fig 8).93

Fig 8.

James Firth. Courtesy of Special Services, Palmer College of Chiropractic.

Firth also developed B. J.’s new model of 9 primary functions,87 wherein every disease was viewed as an abnormal expression of one or a combination of functions.17 The chiropractor’s role was to determine which expressions of functions were abnormal and where the abnormality was coming from. This was determined by a complete history starting with a consideration of a birth CVS. The chiropractor would then determine symptomatology or the “signs of incoordination” through palpation and nerve tracing.87

Firth used the term diathesis, referring to a predisposition to certain diseases, and applied it to CVS. He defined diathesis as the “constitutional disposition to certain forms of incoordination caused by vertebral subluxation.”87 This was an evolution of D. D. Palmer’s original theory of dis-ease.94

Firth noted that the process of adjustment could take several days as the character of the symptoms changed. In the second edition of his book, published in 1920,95 he wrote that the book was dedicated to a view that “disease depends upon the quantity, quality or combination of function abnormally expressed.”95 Every major abnormal function was based on the 9 functions. Today we would refer to this as pathophysiology. He republished the book as Chiropractic Diagnosis in 1929, after he left PSC.96

Arthur Forster’s Theory (1915)

Arthur Forster was a student of Howard and partner with Schulze at NSC (Fig 9). Forster was the secretary of NSC, editor of the journal, and in charge of the dissection lab (where he did his research), and he also headed the chiropractic program.26 Forster’s first book, Principles and Practice of Spinal Adjustment, was published by NSC in 1915.15 In the preface to the first edition of the book, Forster wrote, “The greatest obstacle to the general adoption of Spinal Adjustment has been the inherited belief that vertebral subluxations are impossible. This belief has been successfully shattered by a large amount of experimental work. Particularly upon the cadaver.”15 The book went into 3 editions with him as the author and was adopted by several schools.97

Fig 9.

Arthur Forster.

Forster’s impact on chiropractic history and the development of CVS theory may be far greater than previously reported.18, 86, 98 This is not only because of the use of his text by several schools but also that later editions were revised then printed under new author names. This author believes that this information has not been previously published. The 1923 third edition was replaced in 1939, by Biron, Houser, and Wells’ 4th edition, Chiropractic Principles and Technic.97, 99 The first 3 editions were copyrighted by Forster, but the 1939 book was copyrighted by NSC and excluded Forster’s name. The fifth edition of the book was updated and published in 1947 with the same title as the fourth edition. The first author was changed to Joseph Janse, the new president of NSC.100 The Janse, Houser, and Wells edition was reprinted in 1978, although it is doubtful that many chiropractors knew that Forster was the author of what was essentially the first edition of this series of texts from the National College.98 The book contains extensive material on CVS theories.

Some evidence on how this oversight has impacted the literature is evident in Wardwell, who observed that page 7 of Janse's 1947 text followed “Forster's (1915) lead."86 Wardwell thought he was quoting Janse's 5 principles of chiropractic, but in fact, they were Forster's principles. For example, the chapters are both titled The Theoretical Basis of Chiropractic and start in an almost identical fashion. Forster wrote, “As stated at the commencement of the preceding chapter, chiropractic is founded on the theory that vertebra may become subluxated.”15 Janse, Houser, and Wells started the chapter with, “As stated in the preceding chapter, the practice of chiropractic originally was confined to adjustment of the spine.”100 Much of the texts are quite similar, although the later editions included new sections on neurology, adjustments, and CVS theory. Thus, students were studying a book containing much of Forster’s 1915 text well into the 1980s.

Forster was openly critical of the PSC and several PSC theories, although he integrated much of the CVS theory that came before him. His book used the term subluxation more than 700 times.65 He sought to prove CVS, in part, through dissection, anatomy and physiology, medical standards, and statistical analyses of thousands of cases.97 Although Forster poked fun at many chiropractors in the field, especially in relation to grandiose claims, he himself suggested that 95% of diseases may be related to CVS.101

Forster proposed 5 principles of chiropractic theory, which were retained in chapter 2 of the 1947 edition and reprinted verbatim in Janse's 1978 edition: (1) Vertebra become subluxated, (2) the CVS impinges on nerves, vessels, and lymphatics; (3) impingement impairs impulses and interferes with function of nerves and the cord; (4) abnormal function, disease, or predisposition to disease is the result; and (5) adjustment removes the impingement at the foramen, which leads to restoration, rehabilitation, and normal function. The CVS causes a mechanical pressure at the foramen.65, 97 In the 1940s, Janse built upon these principles viewing the chiropractic thesis as “wholistic” and the cause of disease as a “sequence of dysfunction.”102

Forster wrote that chiropractic recognizes “the true and primary cause of the disease and relieves that cause.”97 The theories are mostly concepts from the work of D. D. Palmer, B. J. Palmer, Carver, Howard, and Modernized Chiropractic, including the term spontaneity, which referred to the body’s inherent ability to proactively and energetically respond to the adjustment.103 Similar to Firth’s theory of diathesis, Forster’s book proposed that the CVS promotes conditions that make disease possible in the organs. Even though it might take time for the disease to develop, he theorized that CVS was the underlying cause of disease in many cases. He believed this was proven through a study of spinal mechanics and clinical results.97

Forster’s and Janse’s editions of the book recommended a thorough history and detailed palpation to determine chronic or acute CVS.65, 97 They described chronic cases may involve adhesions whereby the vertebra had “adapted itself to its new habitat.”97 Although pain usually existed in the area of CVS, they explained that sometimes it was referred or nonexistent and not necessarily an indicator of CVS. Forster wrote, “More often, however, the patient has no subjective sensation of pain, but tenderness may be elicited by pressure over the affected area.”65, 97 Accordingly, he hypothesized that the chiropractic adjustment removes the CVS.

Forster’s reasoning was similar to that of D. D. Palmer in terms of etiology that external traumatic events were a main cause, especially if muscles were not in healthy tone, and that CVS may sometimes be developed and corrected by reflex systems. This, Forster argued, was evident in correction while sleeping.97 The body’s ability to self-correct acute CVS was a common perspective for many early chiropractic theorists.2, 6, 62, 104

Swanberg’s Intervertebral Foramina in Man (1915)

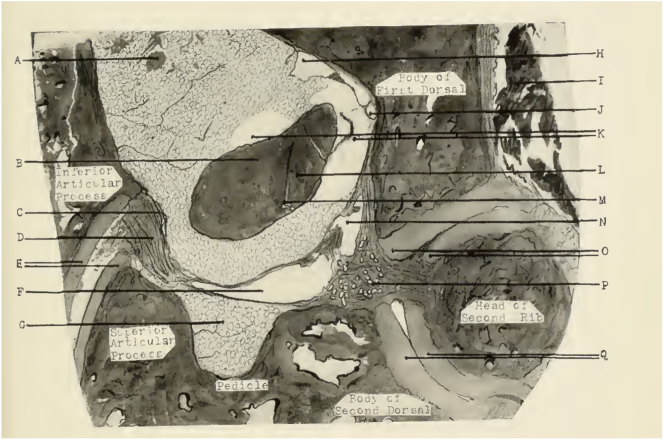

Harold Swanberg was a student of O. G. Smith (Fig 10).105 Smith was an 1899 graduate from D. D. Palmer’s first chiropractic school and later developed naprapathy.106 As a student of Smith’s Chicago College of Naprapathy, Swanberg was inspired to study the IVF in detail. This was inspired by Smith’s early dissection and microscopy studies of the IVF, connective tissue, and ligaments.27, 105 Swanberg’s 1914 text was the first book to complete an anatomical study of the IVF in cats, and his second book was the first text to complete an anatomical study of IVF of humans (Fig 11).107, 108 It was called the “definitive work on the IVF.”105 In an introduction to the book, Santee wrote:

...In the light of this new knowledge, certain theories of spinal tension and compression must be greatly modified. The undoubted anatomic facts, revealed by Mr. Swanberg in this painstaking, scientific work, necessitate a complete restatement of the rationale of “cures” effected by spinal manipulation.108

Fig 10.

Oakley Smith. Courtesy of Special Services, Palmer College of Chiropractic.

Fig 11.

A right lateral view of the spinal canal and its adjacent bony boundaries, opposite the right first dorsal intervertebral foramen. (A) Foreign particles. (B) Posterior root of spinal nerve (spinal ganglion). (C) Blood vessel. (D) Capsular ligament. (E) Articular cartilages. (F) Blood vessel. (G) Fat cells. (H) Blood vessel. (I) Voluntary muscle. (J) Blood vessel. (K) Vacant spaces. (L) Filaments of anterior root of spinal nerve. (M) Fatty-fibrous tissue. (N) Blood vessel.

(O) Articular cartilages. (P) Fatty-fibrous tissue. (Q) Articular cartilages. Depicted from Swanberg (1915).

Swanberg’s findings gave impetus to “non-stepping-on-the-hose” models, like hole-in-one and proprioceptive theories. The book was first advertised by B. J. Palmer in 1914 but then not mentioned again by B. J. until after 1930, along with the introduction of his upper cervical CVS model.109, 110, 111

Swanberg showed that the hard bone on soft nerve was unlikely. Other noncompression models like Verner’s nonimpinging CVS model and Heintze’s proprioceptive CVS model followed suit.112, 113 Swanberg’s dissections demonstrated that the largest and most sensitive neural structure in the IVF, later termed by Watkins the “interpedicular canal,114 is the dorsal nerve root ganglion, made up of sensory cell bodies. Watkins wrote:

However, most dysfunctions are NOT paralyses. Pressure against the dorsal root ganglion in the interpedicular canal is of much greater importance in transmission reduction, but even this is almost negligible when compared to the altered proprioceptive sensory input from the subluxated joint.114

Swanberg’s research, inspired by one of D. D. Palmer’s leading students, helped to transform CVS theory.

Critical Review and Discussion of Previous Works

The CVS theories published between 1908 and 1915 transformed the profession and demonstrate that CVS was important to the early identity of chiropractic. Multiple perspectives are required to fully understand this history of ideas. However, there is a general lack of historical awareness of CVS history in the literature, especially regarding many of the theories from D. D. Palmer and B. J. Palmer. Theorists from this period set the tone for much of the theoretical work that was to come in the future of the profession, and 3 main chiropractic paradigms seem to have emerged during the period studied earlier in the present article.

Chiropractic Vertebral Subluxation Was Chiropractic’s Identity From the Early Years

This author argues that CVS was the identity of chiropractic from the early years of the profession. The modern chiropractic literature about chiropractic's identity should accurately portray the viewpoints from these early years. It does not always do so, which weakens arguments especially about scope of practice and worldviews.115 For example, Schneider et al state that chiropractic’s identity around CVS was always in question.116 They write,

Chiropractic Identity: The chiropractic profession has always suffered from a lack of consensus. What constitutes “the chiropractic identity”? That is, what do we do as chiropractors? Do we adjust subluxations to remove nerve interference? Do we manipulate joint fixations wherever found in the spine or extremity joints? Do we offer holistic health care using any type of natural method to treat any type of health care problem? Do we act as alternative primary care physicians? Or do we do a little bit of all of the above?116

They conclude that chiropractors should identify themselves as musculoskeletal spine specialists. However, their article offers no historical references to support their assumption.116 The history of CVS theory between 1908 and 1915 argue counter to the conclusions of Schneider et al. Chiropractic vertebral subluxation has been referred to as the chiropractic profession’s central defining identity and even the profession’s “rock of Gibraltar.”117, 118

Multiple Perspectives

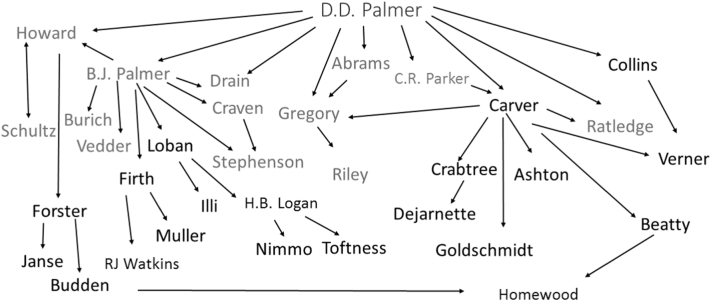

Keating et al suggest that defining chiropractic by CVS is foolish because the meaningfulness of the hypothesis should be tested first.117 They base their conclusion on several assumptions about epistemological approaches to knowledge,119 the importance of validity claims developed from blinded clinical trials, and reference to CVS as more political than scientific.120, 121, 122 Although these assumptions are worth exploring,117 without a larger context and historical basis, the overall argument could use a greater focus on multiple perspectives. For example, the epistemological perspective that they favor is 1 of at least 5 perspectives that chiropractors use to make meaning of the world and the profession.115, 123, 124 These perspectives include a prerational point of view (POV), which they rightly critique as dogmatic, an early rational POV, a rational POV, and several forms of postrational POV, all of which should be considered when thoroughly critiquing chiropractic history and theory (Fig 12).115, 125

Fig 12.

Five levels of thinking as they might be applied to perspectives on research.

Validity claims can be enacted using research methodologies from at least 8 viewpoints on CVS, including subjective, objective, cultural, and social domains.126, 127 Instead, the authors117 argue for 1 approach to objective validity measures, an approach that has since been extensively critiqued in the literature regarding chiropractic, clinical practice, and physical medicine.128, 129, 130, 131, 132

Without adequately describing the varied anatomical, neurological, and physiological definitions for CVS, the rationale for those definitions, and their practical application, any critique of CVS from any era would be lacking in empirical facts. Ultimately, such an analysis should include personal, social, and cultural analytic methodologies to better understand the paradigms that emerged from within the chiropractic profession.126

D. D. Palmer and the Literature

According to Gaucher, D. D. Palmer’s theory of CVS was a substantial contribution to the physiological models of his day.133 Palmer cited contemporary European clinicians and medical researchers in addition to the standard American texts used by most medical schools.28 Gaucher noted that D. D. Palmer’s theories of irritation were described in the literature of his time as neurectasia, nerve irritation, and nerve stretching.30 Palmer proposed that spinal “sprains” described in textbooks on orthopedic surgery referred to impacts on the joints of the spine, which can lead to nerve tension, that can be corrected by spinal adjustment.32 Palmer may have even been aware of Sherrington, Cannon, and Pavlov through his readings of Brubaker and Abrams.2

There is no evidence that many chiropractors read D. D. Palmer’s books in the first half of the chiropractic century or thereafter. In 1995, Gaucher wrote, “There is no real collective memory of Daniel D. Palmer’s importance in chiropractic.”32 This may have been due to many factors such as school politics,18 family conflicts,60 and economics.134 Even though B. J. Palmer republished his father’s 2 books in 1921, it is difficult to say if many chiropractors knew.135 For example, Clarence Weiant, one of the leading academics of the first generation of chiropractors and a 1921 PSC graduate, wrote in 1979 that he had never heard of D. D.’s second book until the 1960s.26, 136

Some historians feel that D. D. Palmer was one of chiropractic’s leading theorists and that his final and most significant CVS theories, such as his concept of the neuroskeleton, have not had a significant impact on the profession.28, 137 However, when reviewing the references of some pivotal texts on CVS theory from the middle of the century, D. D. was cited regularly.112, 114, 138, 139

B. J. Palmer and the Literature

There are not many accurate and detailed accounts about B. J. Palmer’s contribution to CVS theory from 1908 to 1915. For example, his cyclical theory (often referred to as the “safety-pin cycle”) and his interference theory are often attributed to others, such as his father or to R.W. Stephenson, his student. In an award-winning scientific paper published in 1971 by Haldeman and Hammerich, the cycle was compared to Sherrington’s reflex arc but mistakenly attributed to Stephenson.140 Stephenson developed the concept in his 1927 text, which was developed to teach B.J. Palmer's models, theories, and practices.6, 35, 57 There are no known references to the cellular cycle theory before B. J. Palmer’s 1907 introduction of the idea and his 1909 expansion of the theory.6, 59 This misattribution by Haldeman and Hammerich was repeated in the literature and cited by several sources.64, 141, 142, 143, 144 These types of mistakes may have caused some misunderstanding of B. J. Palmer’s legacy.

Another potential example of mistaken reference is from Harper’s book Anything Can Cause Anything. Harper attributed the cellular cycle theory to D. D. Palmer rather than B. J. Palmer.145 Harper studied D. D. Palmer’s writings for a decade before writing the book, but he did not reference B. J. Palmer’s writings. Perhaps Harper learned the cycle theory from his mentor, Drain,62 who learned from both Palmers.146 Harper correctly wrote that D. D. Palmer’s theory of tone could be described with his theory of irritability.139 This line of thinking was also congruent with Loban and Forster.15, 97 But his reference to the cellular theory should have been B. J. Palmer instead of D. D. Palmer. Harper’s book was cited in the literature for many years, which may have perpetuated this mistake.136, 139, 142, 147, 148, 149, 150, 151, 152, 153, 154, 155

Few chiropractic historians or theorists include B. J. Palmer’s cord pressure theory as part of his CVS model.60, 140, 156, 157, 158 Some theorists have made the distinction that B. J. Palmer’s upper cervical model depended on his cord compression model, but none have traced it back to his 1911 text.140, 159 Without understanding how B. J. Palmer’s emphasis on the upper cervical spine in 1934 was a development from his earlier cord pressure model, historians and theorists may misunderstand the evolution of B. J. Palmer’s CVS theories.51, 160

Carver, Howard, Firth, and Gregory

Carver’s structural, full-spine approach affected the profession in many ways.82 Chiropractic techniques developed by Hurley, Logan, Ashton, and DeJarnette owe a theoretical debt to Carver’s concepts of compensations to the gravity line, even though the techniques of correction differed.82 Full-spine developers such as Gonstead, Pettibon, Pierce, Stillwagon, and the Harrisons are of this professional lineage as well.161

Howard, Firth, and Gregory each contributed to CVS theory, as did their students. Howard taught Forster and pioneered the integration of adjunctive therapies alongside CVS correction.18 Firth taught Muller and R. J. Watkins, both of whom were leaders in education and authored textbooks.162, 163 Firth taught his approach to diagnosis and correction of CVS to chiropractors for more than 40 years.26 Gregory’s theories of settlement and inhibition/excitation stimulus influenced several CVS theories.11 Books by his student, Riley, inspired many reflex techniques from Logan to DeJarnette.164, 165, 166

Implications of the Forster/Janse Book

The book authored by Janse, Houser, and Wells contained a substantial amount of content from Forster’s original book. However, there was no attribution to Forster.65, 97 I have found no writings that state that the content of the book was not all written by Janse, although he probably contributed to the new sections and updates.65, 98, 167, 168 This finding highlights the extraordinary impact that Forster’s book had on the profession for more than 60 years.

Those who may refer to students of B. J. Palmer’s books as fundamentalists may also have been studying a text by Forester that was originally written in 1915 into the 1980s.87, 169, 170 The next book to assume the title Principles and Practices of Chiropractic was the one by Scott Haldeman.171, 172

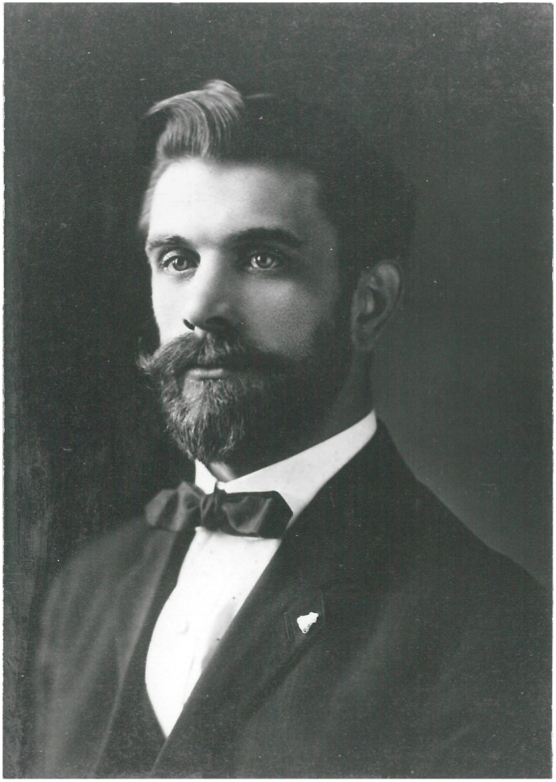

Chiropractic Paradigms

In a recent article, this author suggested that the period between 1908 and 1915 may be credited with the start of 3 distinct paradigms in chiropractic.77 These are the chiropractic paradigm, the middle-chiropractic paradigm, and the medical-chiropractic paradigm. The Chiropractic Paradigm is characterized by D. D. Palmer’s hypothesis that CVS may be corrected by adjustment, leading to a greater expression of health mediated by the central nervous system and the body’s inherent ability to organize2; The Middle-Chiropractic Paradigm is attributed to John Howard and includes the correction of CVS, supplemented by natural therapies.14 The Medical-Chiropractic Paradigm is attributed to Alva Gregory, who attempted to merge the orthodox medical paradigm with Palmer’s, Carver’s, and Abrams’ adjustive methods.10 Elements of these early paradigms may still be found in modern clinical practice (Fig 13).173

Fig 13.

Three chiropractic paradigms, as proposed by the author.

Limitations

This article reflects one person’s interpretation of historical writings and theories. Future reviews of the literature should include more systematic methods. Without detailed search parameters, inclusion and exclusion criteria, synthesis methods, a standard critical appraisal of the literature reviewed, and evaluation of bias, conclusions do need to be made with caution. A strength of this work is that it includes new insights into the history of the CVS, based on primary and secondary sources, many of which have not been included in previous works. However, this research is limited by the writings that are currently available.

Conclusion

D. D. Palmer died in 1913,174 but his death did not affect the growth of the profession and the development of CVS theory. An examination of CVS theory between 1908 and 1915 demonstrates an early focal identity and increasing complexity.2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 19, 21, 24, 34, 48, 49, 51, 71, 72, 85, 89, 108 New perspectives from various chiropractors brought nuanced layers to previous principles, theories, and models. Future critiques of CVS in chiropractic that include historical accounts should include the history from this early period, especially how it was central to the profession’s identity. The identity of the profession was shaped by the increasing complexity of CVS models, which had an effect on the profession for decades (Fig 14). Some of these viewpoints still have relevance today.

Practical Applications

-

•

This series of articles provides an interpretation of the history and development of chiropractic vertebral subluxation theories.

-

•

This series aims to assist modern chiropractors in interpreting the literature and developing new research plans.

Alt-text: Unlabelled Box

Fig 14.

A representation of how each of the subluxation theorists from the 1908-1915 period influenced their students, who carried subluxation theories well into the 1980s in most chiropractic schools.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges Brian McAulay, DC, PhD, David Russell, DC, Stevan Walton, DC, and the Tom and Mae Bahan Library at Sherman College of Chiropractic for their assistance.

Funding Sources and Conflicts of Interest

The author received funding from the Association for Reorganizational Healing Practice and the International Chiropractic Pediatric Association for writing this series of papers. No conflicts of interest were reported for this study.

Contributorship Information

Concept development (provided idea for the research): S.A.S.

Design (planned the methods to generate the results): S.A.S.

Supervision (provided oversight, responsible for organization and implementation, writing of the manuscript): S.A.S.

Data collection/processing (responsible for experiments, patient management, organization, or reporting data): S.A.S.

Analysis/interpretation (responsible for statistical analysis, evaluation, and presentation of the results): S.A.S.

Literature search (performed the literature search): S.A.S.

Writing (responsible for writing a substantive part of the manuscript): S.A.S.

Critical review (revised manuscript for intellectual content, this does not relate to spelling and grammar checking): S.A.S.

References

- 1.Loban J. Chiropractic reasoning. Int Chiropr J. 1911;1(1) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palmer DD. Portland Printing House; Portland, OR: 1910. The Science, Art, and Philosophy of Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palmer DD. Press of Beacon Light Printing Company; Los Angeles, CA: 1914. The Chiropractor. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palmer BJ. vol. 3. Palmer School of Chiropractic; Davenport, IA: 1908. The Philosophy and Principles of Chiropractic Adjustments: A Series of Twenty-four Lecures. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Palmer BJ. vol. 4. Palmer School of Chiropractic; Davenport, IA: 1908. The Science of Chiropractic: Causes Localized. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Palmer BJ. 1st ed. vol. 5. Palmer School of Chiropractic; Davenport, IA: 1909. Philosophy of Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palmer BJ. vol. 6. Palmer School of Chiropracitc; Davenport, IA: 1911. The Philosophy, Science, and Art of Chiropractic Nerve Tracing: A Book of Four Sections. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gregory AS. Self-published; Oklahoma City, OK: 1910. Spinal Adjustment: An Auxillary Method of Treatment. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gregory AS. Self-published; Oklahoma City, OK: 1912. Spinal Treatment: Auxillary Methods. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gregory AS. Palmer-Gregory College; Oklahoma City, OK: 1913. Rational Therapy: A Manual of Rational Therapy Methods. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gregory AS. Self-published; Oklahoma City, OK: 1914. Spondylotherapy Simplified. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carver W. Carver Chiropractic College; Oklahoma City, OK: 1909/1915. Carver’s Chiropractic Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carver W. Carver Chiropractic College: Psychic Department; Oklahoma City, OK: 1915. Applied Psychology. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Howard J. National School of Chiropractic; Chicago, IL: 1912. Encyclopedia of Chiropractic (The Howard System) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Forster A. The National School of Chiropractic; Chicago, IL: 1915. Principles and Practice of Spinal Adjustment. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loban J. Loban Publishing Company; 1915. Technic and Practice of Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Firth J. vol. 7. Palmer College of Chiropractic; Davenport: 1914. Chiropractic Symptomatology. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keating J, Callender A, Cleveland C. Association for the History of Chiropractic; Davenport, IA: 1998. A History of Chiropractic Education in North America. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abrams A. Philopolis Press; San Francisco, CA: 1912. Spondylotherapy: Spinal Concussion and the Application of Other Methods to the Spine in the Treatment of Disease. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loban J. The completeness of chiropractic philosophy. Chiropractor. 1908;4(7&8):30–35. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Craven JH. Chiropractic philosophy: mental. Chiropractor. 1914;10(7):7–8. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carver W. National Instititute of Chiropractic Research; 1936. History of Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Palmer DD, Palmer BJ. The Palmer School of Chiropractic; Davenport, IA: 1906. The Science of Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davis AP. F.L. Rowe; Cincinnati, OH: 1909. Neuropathy: The New Science of Drugless Healing Amply Illustrated and Explained Embracing Ophthalmology, Osteopathy, Chiropractic Science, Suggestive Therapeutics, Magnetics, Instructions on Diet, Deep Breathing, Bathing Etc. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zarbuck M. Illinois Prairie State Chiropractors Association J Chiropr. 1988. Chiropractic parallax: part 2. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rehm W. A necrology. In: Dzaman F, editor. Who's Who in Chiropractic, International. 2nd ed. Who's Who in Chiropractic International Publishing Co; Littelton, CO: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Faulkner T. Association for the History of Chiropractic; Rock Island, IL: 2017. The Chiropractor’s Protégé: The Untold Story of Oakley G. Smith’s Journey with D.D. Palmer in Chiropractic’s Founding Years. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gaucher-Peslherbe P, Wiese G, Donahue J. Daniel David Palmer’s medical library: The founder was “into the literature”. Chiropr Hist. 1995;15(2):63–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Foley J. D.D. Palmer's second book The Chiropractor 1914 - revealed. Chiropr Hist. 36(1):72-86.

- 30.Gaucher-Peslherbe P. Chiropractic, an illegitimate child of science? II. De opprobira medicorum. Eur J Chiropr. 1986;34:99–106. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gaucher-Peslherbe P. Defining the debate: An exploration of the factors that influenced chiropractic’s founder. Chiropr Hist. 1988;8(1):15–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gaucher-Peslherbe P. D.D. Palmer as authentic medical radical. J Neuromusculoskelet Syst. 1995;3(4):175–181. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bovine G. D.D. Palmer’s adjustive technique for the posterior apical prominence: “Hit the High Places”. Chiropr Hist. 2014;34(1):7–19. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Palmer DD. Chiropr Adjust. 1908;1(1) [Google Scholar]

- 35.Palmer BJ. vol. 2. Palmer School of Chiropractic; Davenport, IA: 1907. The Science of Chiropractic: Eleven Physiological. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Palmer DD. Luxations adjusted. Chiropractor Adjust. 1909;1(2):25–28. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Palmer DD. Forward. Chiropr Adjust. 1909;1(2):29. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Palmer DD. The Davenport Times. June 14, 1902. Is chiropractic an experiment? [Google Scholar]

- 39.Landois L. P. Blakiston, Son & Company; 1889. Textbook of Human Physiology. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Palmer DD. January 1896. The Magnetic Cure. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Palmer DD. Chiropractic. 1899;(26) [Google Scholar]

- 42.Palmer DD. Chiropractic. 1897;(17) [Google Scholar]

- 43.Palmer DD. Chiropractic. 1900;(26) [Google Scholar]

- 44.Palmer DD. Chiropr Adjust. 1909;1(3) [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gibbons R, Joy Loban and Andrew P. Davis: itinerant healers and “schoolmen.". Chiropr Hist. 1991;11(1):23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Encyclopaedia Britannica Eighth Edition. A. & C. Black; London, England: 1902. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Morat JP. Archibeld Constable; London, England: 1906. Physiology of the Nervous system. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Palmer BJ. Retracing: A common experience the process of getting well. Palmer School of Chiropractic; Davenport, IA: 1910. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Palmer BJ. Momentum. Chiropractor. 1913;9(4) [Google Scholar]

- 50.Peters R. Integral Altitude; Asheville, NC: 2014. An Early History of Chiropractic: The Palmers and Australia. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Palmer BJ. 2nd ed. vol. 3. Palmer School of Chiropractic; Davenport, IA: 1911. The Philosophy and Principles of Chiropractic Adjustments: A Series of Thirty Eight Lectures. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Primrose A. Compression of spinal cord causing paraplegia: and its surgical treatment. JAMA. 1910;55(17):1434–1438. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Palmer DD. Letter to the editor. Religio-Philos J. 1872;12(16):6. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Palmer DD. Palmer Infirmary and Chiropractic Institute; 1903. Innate intelligence. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Palmer BJ, Craven JH. 2nd ed. vol. 5. Palmer School of Chiropractic; Davenport, IA: 1916. The Philosophy of Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Koch D. Roswell Publishing Co; Roswell, GA: 2008. Contemporary Chiropractic Philosophy: An Introduction. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stephenson R. Palmer School of Chiropractic; Davenport, IA: 1927. Chiropractic Textbook: Vol. 14. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sinnott R. Self-published; Mokena, IA: 2009. Sinnott’s Textbook of Chiropractic Philosophy. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cooley C. Letter to the editor. Chiropractor. 1909;5(11):20. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Keating J. Association for the History of Chiropractic; Davenport, IA: 1997. B.J. of Davenport: The Early Years of Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Loban J. Loban Publishing Company; 1916. Technic and Practice of Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Drain J. Standard Print Company; San Antonio, TX: 1927. Chiropractic Thoughts. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Watkins RJ. NCA Convention. 1949. Tissue memory in retracing. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Janse J, Goldstein M. History of the development of chiropractic concepts: chiropractic terminology. In: Goldstein M, editor. The Research Status of Spinal Manipulative Therapy: A Workshop Held at the National Institutes of Health, February 2-4, 1975. vol. 15. U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare; Bethesda, MD: 1975. pp. 25–42. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Janse J, Houser RH, Wells BF. National College of Chiropractic; Chicago, IL: 1947. Chiropractic Principles and Technic: For Use by Students and Practitioners. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Napolitano E. Columbian Institute of Chiropractic Yearbook. 1963. Chiropractic principles and practice. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lowell Ward DC. Stressology pioneer. Dyn Chiropr. 1993;11(10) [Google Scholar]

- 68.Strauss J. Strauss; 1988. Freshman Philosophy. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Epstein D. Amber Allen; San Raphael, CA: 1994. The Twelve Stages of Healing: A Network Approach to Wholeness. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Filippi M. Subluxation as a social/cultural imitation: resolving a phylobiological epiphenomenon, part 2. J Vert Sublux Res. 1999;3(4):10–11. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Craven JH. Chiropractic philosophy: creation. Chiropractor. 1914;10(8) [Google Scholar]

- 72.Craven JH. Chiropractic philosophy: Transformation. Chiropractor. 1914;10(10):14–15. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Palmer DD. Communicating nerves. Chiropr Adjust. 1909;1(2):40. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Catalogue of Copyright Entries. Library of Congress Copyright Office: Goverment Printing Office; Washington, DC: 1911. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Palmer DD. The adjuster too ridiculous. Chiropr Adjust. 1909;1(4):15. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Breig A. Almqvist & Wiksell International; 1978. Adverse Mechanical Tension in the Central Nervous System: An Analysis of Cause and Effect: Relief by Functional Neurosurgery. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Senzon S. Chiropractic and systems science. Chiropr Dialogues. 2015:9–20. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Vol. 2. International News Service; New York, NY: 1915. Press Reference Library: Western Edition Notables of the West. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Keating J, Rehm W, William C, Schulze MD. DC (1870-1936): From mail-order mechano-therapists to scholarship and professionalism among drugless physicians. Chiropr J Aust. 1995;25(4):122–128. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zarbuck M. Illinois Prairie State Chiropractors Association J Chiropr. 1989. Chiropractic parallax: part 5. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zarbuck M. Illinois Prairie State Chiropractors Association J Chiropr. 1989. Chiropractic parallax: Part 6. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rosenthal M. The structural approach to chiropractic: from Willard Carver to present practice. Chiropr Hist. 1981;1(1) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Carver W. Carver; East Aurora, NY: 1922. Carver’s Chiropractic Analysis of Chiropractic Principoles: As Applied to Pathology, Relatology, Symtomology and Diagnosis. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Keating J, Alva Gregory MD. Los Angeles College of Chiropractic. 1998. DC. Chronology. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Palmer DD. Chiropr Adjust. 1909;1(2):62. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wardwell W. Mosby; St. Louis, MO: 1992. Chiropractic: History and Evolution of a New Profession. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Firth J. vol. 7. Palmer College of Chiropractic; Davenport, IA: 1925. Chiropractic Symptomatology. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Firth J. What chiropractic does for it. Chiropractor. 1913;9(12):16–18. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Firth J. Nervous prostration. Chiropractor. 1914;10(1):8–9. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Firth J. Bronchitis. Chiropractor. 1914;10(2):11–12. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Firth J. What chiropractic can do for heart trouble. Chiropractor. 1914;10(3):13–15. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Firth J. Typhoid fever. Chiropractor. 1914;10(6):5–8. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Firth J. J.N. Firth; Indianapolis, IN: 1948. A text-book on chiropractic diagnosis. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Palmer DD. The Burlington Daily Hawkeye: Sunday Morning. 1887. Cured by magnetism. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Firth JA. Driffill Printing Co.; Rock Island, IL.: 1920. Text-Book on Chiropractic Symptomatology: Or, The Manifestations of Incoordination Considered From a Chiropractic Standpoint. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Firth J. Firth; Indianapolis, IN: 1929. A Text-book on Chiropractic Diagnosis. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Forster A. 3rd ed. The National Publishing Association; Chicago, IL: 1923. Principles and Practice of Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Phillips R. R. Phillips; Los Angeles, CA: 2006. Joseph Janse: The Apostle of Chiropractic Education. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Biron WA, Wells BF, Houser RH. National College of Chiropractic; Chicago, IL: 1939. Chiropractic Principles and Technic: For Use by Students and Practitioners. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Janse J, Houser R, Wells B. National College of Chiropractic; Chicago, IL: 1978. Chiropractic Principles and Technic: For Use by Students and Practitioners. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Forster A. National Publishing Association; Chicago, IL: 1921. The White Mark: An Editorial History of Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Janse J. National College of Chiropractic; Lombard, IL: 1976. Principles and Practice of Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Smith O, Langworthy S, Paxson M. American School of Chiropractic; Cedar Rapids, IA: 1906. A Textbook of Modernized Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ratledge T. Ratledge; Los Angeles, CA: 1949. The Philosophy of Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Cramer G, Scott C, Tuck N. The holey spine: A summary of the history of scientific investigation of the intervertebral foramina. Chiropr Hist. 1998;18(2):13–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Zarbuck M. A profession for ‘Bohemian chiropractic’: Oakley Smith and the evolution of naprapathy. Chiropr Hist. 1986;6:77–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Swanberg H. Chicago Scientific Publishing Co.; Chicago, IL: 1914. The Intervertebral Foramen; An Atlas and Histologic Description of an Intervertebral Foramen and Its Adjacent Parts. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Swanberg H. Chicago Scientific Publishing Co.; Chicago, IL: 1915. The Intervertebral Foramina in Man; The Morphology of the Intervertebral Foramina in Man, Including a Description of Their Contents and Adjacent Parts, With Special Reference to the Nervous Structures. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Advertisement The intervertebral foramen by Harold Swanberg. Chiropractor. 1914;10(2):47. [Google Scholar]

- 110.Palmer BJ. Disciplining the hour. Chiropractor. 1933;29(11):4. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Cheney J. The universality of chiropractic. Chiropractor. 1931;29(27):15. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Verner J. 2nd ed. Dr. P.J. Cerasoli; Brooklyn, NY: 1956. The Science and Logic of Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 113.Heintze A. The proprioceptive faculty: a broader theory of chiropractic is indicated. Chiropr J. 1937:11–44. [Google Scholar]

- 114.Walton S. The Institute Chiropractic; Asheville, NC: 2017. The Complete Chiropractor: RJ Watkins, DC, PhC, FICC, DACBR. [Google Scholar]

- 115.Senzon S. Chiropractic professionalism and accreditation: an exploration of conflicting worldviews through the lens of developmental structuralism. J Chiropr Humanit. 2014;21(1):25–48. doi: 10.1016/j.echu.2014.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Schneider M, Murphy D, Perle S, Hyde T, Vincent R, Ierna G. 21st century paradigm for chiropractic. J Am Chiropr Assoc. 2005:8–15. [Google Scholar]

- 117.Keating J, Charton K, Grod J, Perle S, Sikorski D, Winterstein J. Subluxation: dogma or science. Chiropr Osteopat. 2005;13(17) doi: 10.1186/1746-1340-13-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.DeJarnette MB. The chiropractic subluxation. ACA J Chiropr. 1965;2(6):8–11. [Google Scholar]

- 119.Keating J. Stockton Foundation for Chiropractic Research; Stockton, CA: 1992. Toward a Philosophy of the Science of Chiropractic: A Primer for Clinicians. [Google Scholar]

- 120.Keating J. Science and politics and the subluxation. Am J Chiropr Med. 1988;1(3):107–110. [Google Scholar]

- 121.Keating J. To hunt the subluxation: clinical research considerations. J Man Phys Ther. 1996;19(9):613–619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Nelson C. The subluxation question. J Chiropr Humanit. 1997;7:46–55. [Google Scholar]

- 123.Kegan R. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1982. The Evolving Self: Problem and Process in Human Development. [Google Scholar]

- 124.Cook-Greuter S. Cook-Greuter & Associates; Wayland, MA: 2007. Ego Development: Nine Levels of Increasing Embrace. [Google Scholar]

- 125.Senzon S. Constructing a philosophy of chiropractic: when worldviews evolve and postmodern core. J Chiropr Humanit. 2011;18(1):39–63. doi: 10.1016/j.echu.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Senzon S. Constructing a philosophy of chiropractic I: an Integral map of the territory. J Chiropr Humanit. 2010;17(17):6–21. doi: 10.1016/j.echu.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Esbjörn-Hargens S. Integral research: a multi-method approach to investigating phenomena. Constructivism Hum Sci. 2006;2(1):79–107. [Google Scholar]

- 128.Hampton J. Evidence-based medicine, opinion-based medicine, and real-world medicine. Perspect Biol Med. 2002;45(4):549–568. doi: 10.1353/pbm.2002.0070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Villanueva-Russell Y. Evidence-based medicine and its implications for the profession of chiropractic. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60:545–561. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Lambert H. Accounting for EBM: notions of evidence in medicine. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62(11):2633–2645. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Rosner A. Evidence-based medicine: revisiting the pyramid of priorities. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2012;16(1):42–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Koutouvidis N. CAM and EBM: arguments for convergence. J R Soc Med. 2004;97(1):39–40. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.97.1.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Gaucher-Peslherbe P. National College of Chiropractic; Chicago, IL: 1993. Chiropractic: Early Concepts in Their Historical Setting. [Google Scholar]

- 134.Villaneuva-Russell Y. Graduate School, University of Missouri; Columbia, MO: 2002. On the Margins of the System of Professions: Entrepreneurialism and Professionalism as Forces Upon and Within Chiropractic [dissertation] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Palmer BJ, editor. The Chiropractic Adjuster; A Compilation of the Writings of D.D. Palmer. vol. 4. Palmer School of Chiropractic; Davenport, IA: 1921. [Google Scholar]

- 136.Weiant C. 1979. Chiropractic Philosophy: The Misnomer That Plagues the Profession. [Google Scholar]

- 137.Keating J. The evolution of Palmer’s metaphors and hypotheses. Philos Constr Chiropr Prof. 1992;2(1):9–19. [Google Scholar]

- 138.Homewood AE. Earl Homewood; Willowdale, Ontario: 1962. The Neurodynamics of the Vertebral Subluxation. [Google Scholar]

- 139.Harper W. Texas Chiropractic College; Pasadena, TX: 1997. Anything Can Cause Anything: A Correlation of Dr. Daniel David Palmer’s Priniciples of Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 140.Haldeman S, Hammerich K. The evolution of neurology and the concept of chiropractic. ACA J Chiropr. 1973;VII(S-57):60. [Google Scholar]

- 141.Janse J. The revolving manipulative sciences and arts in health care: the 1977 Phillip Law lecture. ACA J Chiropr. 1977:25. [Google Scholar]

- 142.Howe J. A contemporary perspective on chiropractic and the concept of subluxation. ACA J Chiropr. 1976;X(S-165) [Google Scholar]

- 143.Leach R. The chiropractic theories: discussion of some important considerations. ACA J Chiropr. 1981;15(S-19) [Google Scholar]

- 144.ACA Chiropractic terminology: A report of the ACA Council on Technic. ACA J Chiropr. 1988:46. [Google Scholar]

- 145.Harper W. William D. Harper; Texas: 1964. Anything Can Cause Anything: A Correlation of Dr. Daniel David Palmer’s Priniciples of Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 146.Drain JR. Spears Papers. Cleveland College Archives; 1956. We Walk Again. [Google Scholar]

- 147.Haldeman S. Spinal and paraspinal receptors. ACA J Chiropr. 1972;VI:S-25. [Google Scholar]

- 148.Kimmel E. Electro analytical instrumentation: part 1. ACA J Chiropr. 1972;VI(S-33) [Google Scholar]

- 149.Hinton H. Neurology. ACA J Chiropr. 1972:22. [Google Scholar]

- 150.Jessen A. The syndrome of leriche. ACA J Chiropr. 1973;VII(Jul):S-53. [Google Scholar]

- 151.Schafer R. Review: anything can cause anything. ACA J Chiropr. 1974:23. [Google Scholar]

- 152.Anderson C. Cellular reserach and the chiropractic profession - I: development of an approach for experimental studies. ACA J Chiropr. 1975;(IX):S-1. [Google Scholar]

- 153.Malik D, Slack J, Brooks S, Wald L. Effectiveness of chiropractic adjustment and physical therapy to treat spinal subluxation. ACA J Chiropr. 1983;17(Jun):63. [Google Scholar]

- 154.Smallie P. World-Wide Books; Stockton, CA: 1988. The Opening of the Chiropractic Mind. [Google Scholar]

- 155.Keating J. Philosophical barriers to technique research in chiropractic. Chiropr Tech. 1989;1(1) [Google Scholar]

- 156.Palmer BJ. vol. 18. Palmer School of Chiropractic; Davenport. IA: 1934. The Subluxation Specific The Adjustment Specific. [Google Scholar]

- 157.Amman M. A profession seeking clinical competency: the role of the Gonstead chiropractic technique. Chiropr Hist. 2008;28(2) [Google Scholar]

- 158.Quigley W. The last days of B.J. Palmer: revolutionary confronts reality. 1989;9(2):11–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Gatterman M. Mosby; St. Louis, MO: 1995. Foundations of Chiropractic Subluxation. [Google Scholar]

- 160.Palmer BJ. vol. 13. Palmer School of Chiropractic; Davenport, IA: 1920. A Textbook on the Palmer Technique of Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 161.Cooperstein R, Gleberzon B. Churchill Livingstone; Philadelphia, PA: 2004. Technique Systems in Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 162.Muller RO. The Chiro Publishing Company; Toronto, Canada: 1954. Autonomics in Chiropractic: The Control of Autonomic Imbalance. [Google Scholar]

- 163.Peterson A, Watkins RJ, Himes H, CMC College. Canadian Memorial Chiropractic College; 1965. Segmental Neuropathy: The First Evidence of Developing Pathology. [Google Scholar]

- 164.Riley S. J.S. Riley; 1921. Conquering Units: Or the Mastery of Disease. [Google Scholar]

- 165.Logan H. Logan; St. Louis, MO: 1931. Logan Universal Health Basic Technique. [Google Scholar]

- 166.DeJarnette B. DeJarnette; Nebraska City, NE: 1933. Sacro Occipital Technic. [Google Scholar]

- 167.Obituary: Joseph Janse, DC, FACCRJ CCA. 1986;30(1):52. [Google Scholar]

- 168.Phillips R, Triano JJ. Historical perspective Joseph Janse. Spine. 1995;20(21):2349–2353. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199511000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Gibbons R. The rise of the chiropractic educational establishment: 1897-1980. In: Lints-Dzaman F, Scheider S, Schwartz L, editors. Who’s Who in Chiropractic International. Who’s Who in Chiropractic International Pub. Co.; Littleton, CO: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 170.Gibbons R. Physician-chiropractors: medical presence in the evolution of chiropractic. Bull Hist Med. 1981;55:233–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Haldeman S. Appleton-Century-Crofts; New York, NY: 1980. Modern Developments in the Principles and Practice of Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 172.Haldeman S. McGraw-Hill; New York, NY: 2004. Principles and Practice of Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 173.McDonald W. Trafford Publishing; 2009. Chiropractic Peace. [Google Scholar]

- 174.Geilow V. Fred Barge; La Crosse, WI: 1982. Old Dad Chiro: A Biography of D.D. Palmer, Founder of Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]