KEY POINTS

Mainstream research approaches require a substantial redesign to be relevant, respectful and effective for Aboriginal people and communities.

Engagement must be embedded throughout to ensure that the research is relevant to all partners, and that the results are accessible and meaningful to all.

Building capacity is crucial on both sides of the partnership and occurs through collaboration.

The best interests of the child (patient) must remain at the centre of all decisions.

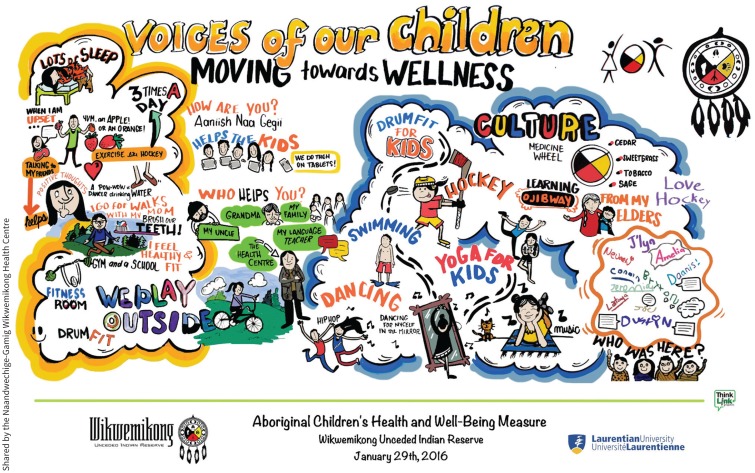

Aboriginal children experience substantial and persistent health disparities compared with their mainstream peers;1–3 innovative methods are needed to assess the effectiveness of new interventions. Health leaders in Wiikwemkoong Unceded Territory engaged with a team of scientists at Laurentian University to address these disparities, and developed a strong and respectful engagement. This collaboration began with the Outdoor Adventure Leadership Experience project (https://oalevideo.laurentian.ca) and led to the development of a culturally relevant measure of health for children 8 to 18 years of age: the Aboriginal Children’s Health and Well-being Measure (ACHWM).4 In this paper, we share the lessons learned through a community-engaged project to evaluate a new intervention for health promotion.

The purpose of our research project is to evaluate the effectiveness of screening, triage and subsequent treatment on the health of children in Wiikwemkoong. Aboriginal communities view the child as nested within the family and within the community.3,5 Thus, our approach was child-centred and community-engaged, with ongoing guidance from families, community members and leadership. This is a particularly important form of patient-oriented research.

Our focus is “upstream” on health promotion for Aboriginal children within the context of their rural community. There are multiple perspectives that require consideration in this context. Western (or mainstream) research methods are braided together with Aboriginal ways of knowing throughout this research project, in keeping with a two-eyed seeing approach.6 Although the dual perspectives add complexity to the process, when united in a good way, these approaches add strength to the design, much like the braiding of sweetgrass (which represents strength and kindness), with a shared goal of improving the health of Aboriginal children.

Patient-oriented research and engagement are the cornerstones of the Canadian Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research (SPOR). Our approach is both patient-oriented and community-engaged. It developed through a decade of community-based research that integrated child-centric research methods7 with Aboriginal ways of knowing6 and a community-engaged focus.8 We endeavour to work together in a good way, often “in circle” where there are no corners in a network of interconnections, much like the Anishinaabek dreamcatcher, which represents protection and comfort of children. We are guided by both scientific principles and teachings from Elders. Everyone around the circle is valued, and participants’ lived experiences are central to our process.

Our community-engaged approach led to two research questions that were important to all partners: Is the ACHWM able to identify the needs of youths earlier in their illness pathway? Does earlier recognition lead to better health outcomes one year later? Children are being recruited from the community and invited to participate in a self-reported health-screening process.9 Those who are identified as having acute health concerns are connected to local services. Their health outcomes are measured one year later using the measure. The ACHWM is a scientifically valid health self-assessment that was developed with and for Aboriginal children4 and implemented on Android tablets as an innovative form of patient engagement (www.ACHWM.ca). We will compare the health patterns of those identified through screening with those who are already connected to local services to answer our research questions.

There were many lessons learned through this project that would have been missed without a community-engaged approach. For example, the IMPACT grant writing instructions required us to frame the research question using the PICOT format (population, intervention, comparison, outcome, time), which was incongruent with Aboriginal ways of knowing. This narrow focus on a Western biomedical model was perceived as disrespectful at times, because it established ground rules outside the collaboration that privileged the Western lens. Getting the balance right was critical for this team, as living in balance is the foundation for the Aboriginal way of life.

The partnership has led to a design that will generate results that are inherently meaningful to Aboriginal communities and respected by the scientific community. It is enabling us to tackle issues that could not be addressed by other groups. The lessons learned will be easier to adopt because of the community ownership and direct engagement in the work. We have been able to leverage the strengths of all partners to move this research forward. We have in turn leveraged this work to obtain additional funding for both service delivery in the community and research collaboration.

The team has also gained insights from the children, both through the measure and by including youth from the community as research team members. Keeping the children’s voices and perspective in mind guides all of our decisions. The question “What would be in the best interests of the children?” keeps us grounded.

We are now just past the halfway mark in this grant. The nature of collaborative research is time-consuming, and funding timelines inevitably do not line up with the realities of the community or those of children. Focusing on the big-picture goal (improving the health of children), building relationships and respecting the partnership are the priorities. These have been the key to our success to date. We are grateful that the funder has accommodated the extended timeline necessary to protect our priorities.

Image courtesy of Shared by the Naandwechige-Gamig Wikwemikong Health Centre

At this point, we have sufficient data to address the first research question and have faced challenges implementing the study into clinical practice to address the second question. We are currently focusing most of our energy on the latter. Because we have succeeded in connecting children at risk to local services, we have also discovered new barriers: it is difficult to retain children in clinical practice. This new challenge calls for new solutions that we are exploring with our partners. Keeping children at the forefront of decision-making has enabled us to take a creative and solution-focused approach.

Our community–university collaboration has generated key lessons learned that add to what is known.10 The integration of two world views is expected to enhance uptake of this project’s results because they will speak to both Western scholars and Aboriginal health leaders. More importantly, we will be able to generate new solutions to address critical health inequities. Together, we are responding to the call for action from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s report (www.nctr.ca). In the process, capacity has been enhanced on both sides, respect has been demonstrated for the sovereignty of the First Nation, and we have identified innovations to support child health with existing resources.

We are at a critical time in Canada, with real opportunities to address the health inequities borne by Aboriginal children. The operationalization of Jordan’s Principle (www.fncaringsociety.com/jordans-principle) provides new hope, to put what is best for each child at the forefront. Research has the potential to improve the health of Aboriginal children, when all aspects of the work are carried out in respectful collaboration.

Footnotes

More information on this project is available at www.ossu.ca/IMPACTAwards.

Competing interests: The copyright on the Aboriginal Children’s Health and Well-being Measure is jointly held by Nancy L. Young, Mary Jo Wabano and Stephen Ritchie. This measure is shared with Aboriginal communities and agencies free of charge. No other competing interests were declared.

This article was solicited and has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Both authors wrote the commentary, gave final approval of the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: This project was supported by a research grant from OSSU (the Ontario SPOR [Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research] SUPPORT [Support for People and Patient-Oriented Research and Trials] Unit).

References

- 1.King M, Smith A, Gracey M. Indigenous health part 2: the underlying causes of the health gap. Lancet 2009;374:76–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Canadian UNICEF Committee. Canadian supplement to the state of the world’s children. Aboriginal children’s health: leaving no child behind. Toronto: Canadian UNICEF Committee; 2009. Available: www.unicef.ca/sites/default/files/imce_uploads/DISCOVER/OUR%20WORK/ADVOCACY/DOMESTIC/POLICY%20ADVOCACY/DOCS/Leaving%20no%20child%20behind%2009.pdf (accessed 2018 Sept. 25). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greenwood ML, de Leeuw SN. Social determinants of health and the future well-being of Aboriginal children in Canada. Paediatr Child Health 2012;17:381–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Young NL, Wabano MJ, Burke TA, et al. A process for creating the Aboriginal Children’s Health and Well-being Measure (ACHWM). Can J Public Health 2013; 104:e136–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Loppie Reading C, Wien F. Health inequalities and social determinants of Aboriginal Peoples’ health. Prince George (BC): National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barlett C, Marshall M, Marshall A. Two-eyed seeing and other lessons learned within a co-learning journey of bringing together Indigenous and mainstream knowledges and ways of knowing. J Environ Studies Sci 2012;2:331–40. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Young NL, Yoshida KK, Williams JI, et al. The role of children in reporting their physical disability. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1995;76:913–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maar MA, Sutherland M, McGregor L. A regional model for ethical engagement: the First Nations Research Ethics Committee on Manitoulin Island. Aboriginal Policy Research Volume IV Setting the Agenda for Change 2007:4:55–68. Available: http://ir.lib.uwo.ca/aprci/112 (accessed 2017 Sept. 7). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Young NL, Jacko D, Wabano MJ, et al. A screening mechanism to recognize and support Aboriginal children at-risk: based on a child-centric survey. Can J Public Health 2016;107:e399–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Starkes JM, Baydala LT; Canadian Paediatric Society First Nations IMHC. Health research involving First Nations, Inuit and Métis children and their communities. Paediatr Child Health 2014;19:99–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]