Abstract

Background

The explicit use of theory in research helps expand the knowledge base. Theories and models have been used extensively in HIV‐prevention research and in interventions for preventing sexually transmitted infections (STIs). The health behavior field uses many theories or models of change. However, many educational interventions addressing contraception have no explicit theoretical base.

Objectives

To review randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that tested a theoretical approach to inform contraceptive choice and encourage or improve contraceptive use.

Search methods

To 1 November 2016, we searched for trials that tested a theory‐based intervention for improving contraceptive use in PubMed, CENTRAL, POPLINE, Web of Science, ClinicalTrials.gov, and ICTRP. For the initial review, we wrote to investigators to find other trials.

Selection criteria

Included trials tested a theory‐based intervention for improving contraceptive use. Interventions addressed the use of one or more methods for contraception. The reports provided evidence that the intervention was based on a specific theory or model. The primary outcomes were pregnancy and contraceptive choice or use.

Data collection and analysis

We assessed titles and abstracts identified during the searches. One author extracted and entered the data into Review Manager; a second author verified accuracy. We examined studies for methodological quality.

For unadjusted dichotomous outcomes, we calculated the Mantel‐Haenszel odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI). Cluster randomized trials used various methods of accounting for the clustering, such as multilevel modeling. Most reports did not provide information to calculate the effective sample size. Therefore, we presented the results as reported by the investigators. We did not conduct meta‐analysis due to varied interventions and outcome measures.

Main results

We included 10 new trials for a total of 25. Five were conducted outside the USA. Fifteen randomly assigned individuals and 10 randomized clusters. This section focuses on nine trials with high or moderate quality evidence and an intervention effect. Five based on social cognitive theory addressed preventing adolescent pregnancy and were one to two years long. The comparison was usual care or education. Adolescent mothers with a home‐based curriculum had fewer second births in two years (OR 0.41, 95% CI 0.17 to 1.00). Twelve months after a school‐based curriculum, the intervention group was more likely to report using an effective contraceptive method (adjusted OR 1.76 ± standard error (SE) 0.29) and using condoms during last intercourse (adjusted OR 1.68 ± SE 0.25). In alternative schools, after five months the intervention group reported more condom use during last intercourse (reported adjusted OR 2.12, 95% CI 1.24 to 3.56). After a school‐based risk‐reduction program, at three months the intervention group was less likely to report no condom use at last intercourse (adjusted OR 0.67, 95% CI 0.47 to 0.96). The risk avoidance group (abstinence‐focused) was less likely to do so at 15 months (OR 0.61, 95% CI 0.45 to 0.85). At 24 months after a case management and peer‐leadership program, the intervention group reported more consistent use of hormonal contraceptives (adjusted relative risk (RR) 1.30, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.58), condoms (RR 1.57, 95% CI 1.28 to 1.94), and dual methods (RR 1.36, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.85).

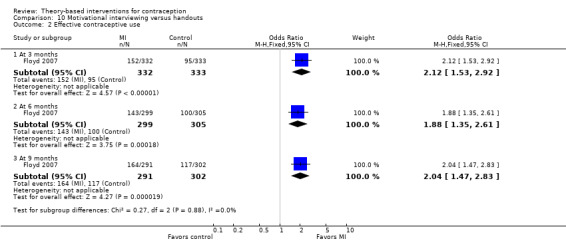

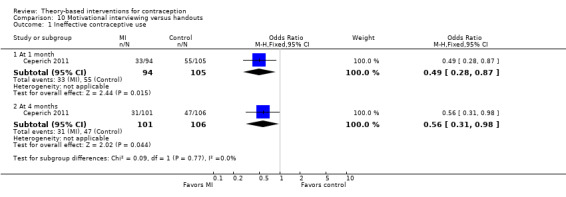

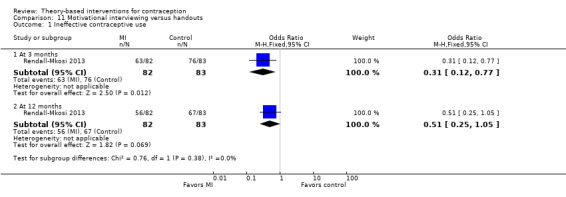

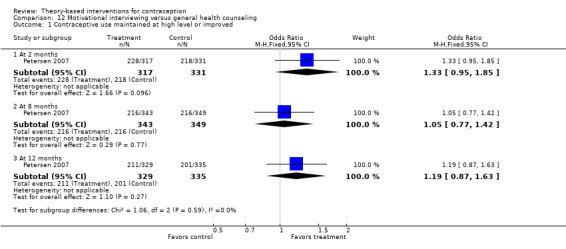

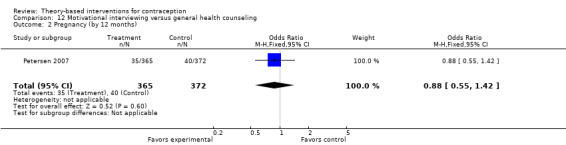

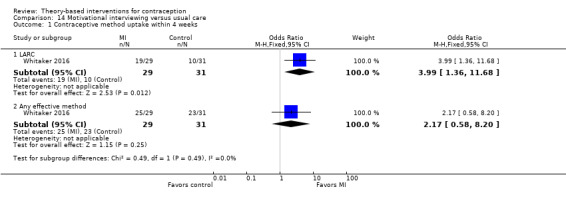

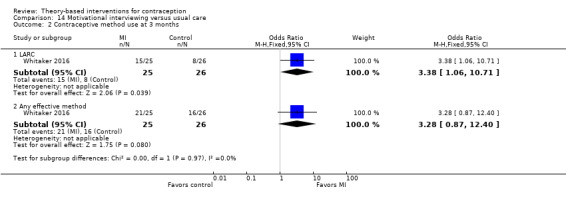

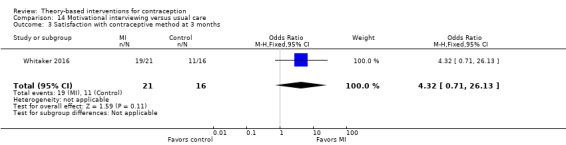

Four of the nine trials used motivational interviewing (MI). In three studies, the comparison group received handouts. The MI group more often reported effective contraception use at nine months (OR 2.04, 95% CI 1.47 to 2.83). In two studies, the MI group was less likely to report using ineffective contraception at three months (OR 0.31, 95% CI 0.12 to 0.77) and four months (OR 0.56, 95% CI 0.31 to 0.98), respectively. In the fourth trial, the MI group was more likely than a group with non‐standard counseling to initiate long‐acting reversible contraception (LARC) by one month (OR 3.99, 95% CI 1.36 to 11.68) and to report using LARC at three months (OR 3.38, 95% CI 1.06 to 10.71).

Authors' conclusions

The overall quality of evidence was moderate. Trials based on social cognitive theory focused on adolescents and provided multiple sessions. Those using motivational interviewing had a wider age range but specific populations. Sites with low resources need effective interventions adapted for their settings and their typical clients. Reports could be clearer about how the theory was used to design and implement the intervention.

Keywords: Adolescent; Adult; Female; Humans; Male; Pregnancy; Health Behavior; Models, Theoretical; Condoms; Condoms/statistics & numerical data; Contraception; Contraception/methods; Contraception/statistics & numerical data; Contraceptive Agents; Contraceptive Agents/administration & dosage; Contraceptive Devices, Female; Contraceptive Devices, Female/statistics & numerical data; HIV Infections; HIV Infections/prevention & control; Motivational Interviewing; Pregnancy in Adolescence; Pregnancy in Adolescence/prevention & control; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Sexually Transmitted Diseases; Sexually Transmitted Diseases/prevention & control; Unsafe Sex

Plain language summary

Improving birth control use with programs based on theory

Background

Theories and models help explain how behavior change occurs. HIV‐prevention research has used theories and models. Programs to prevent sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are often based on behavioral science. The health field has used many theories and models of change. However, programs that address birth control often have no stated theory base.

Methods

We did computer searches for randomized trials until 1 November 2016. Programs included must have tested a theory‐based program for improving birth control use. We excluded trials focused on high‐risk groups and efforts to prevent infections. Programs addressed the use of one or more birth control methods. The reports showed that the theory or model was part of the program design. The main outcomes were pregnancy and birth control use.

Results

We added 10 new trials for a total of 25. Five came from countries other than the USA. This section focuses on nine trials with good quality results and programs that worked. Five had programs based on social cognitive theory (SCT) and four used motivational interviewing (MI). The SCT studies addressed teen pregnancy and lasted one to two years. They included home‐based sessions for adolescent mothers, school‐based programs to prevent pregnancy and HIV, and community‐based case management. Compared to usual services for adolescent mothers, a program group had fewer second births. The other four trials showed more use of effective birth control or use of condoms at last sex among adolescents in school or in the community, The MI studies focused on individuals from a wide age range. Compared to a group with handouts only in three studies, the MI group had more use of effective birth control or less use of ineffective birth control. In another study, the MI group had more women who started using long‐acting birth control than those with usual counseling.

Authors' conclusions

The overall quality of results for our review was moderate. Trials based on SCT focused on teens and provided many sessions. Those using MI had a wider age range but special populations. Sites with low resources need programs than can work in their settings and with their usual clients. Reports could be clearer about how the theory was used to design and conduct the program.

Summary of findings

for the main comparison.

| Behavioral intervention based on social cognitive theory compared with usual care or education for improving contraceptive use | ||||

|

Patient or population: adolescents and women with need for contraception Settings: clinic or home Intervention: behavioral intervention based on social cognitive theory Comparison: usual care or education | ||||

| Outcomes | Relative effect (95% CI) | Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

| Second birth in 2 years | OR 0.41 (0.17 to 1.00) | Black 2006 | High | Home‐based curriculum (19 sessions) to delay second birth vs usual care; adolescent mothers |

| Consistency of hormonal contraceptive use at: 12 months; 18 months; 24 months |

Reported adjusted RR:

1.46 (1.13 to 1.89); 1.36 (1.02 to 1.83); 1.30 (1.06 to 1.58) |

Sieving 2013 | Moderate | Case management and leadership (18 months) vs usual care; adolescent girls |

| Consistency of condom use at: 12 months; 24 months |

Reported adjusted RR: 1.45 (1.26 to 1.67); 1.57 (1.28 to 1.94) |

|||

| Consistency of dual method use (OCs + condoms) at: 12 months; 24 months |

Reported adjusted RR: 1.58 (1.03 to 2.43); 1.36 (1.01 to 1.85) |

|||

| Use of effective contraceptive method:

at 7 months after baseline (after year 1 sessions); at 19 months after baseline (12 months after year 2 sessions) |

Reported adjusted OR ± SE: 1.62 ± 0.22 (P = 0.03); 1.76 ± 0.29 (P = 0.05) |

Coyle 2001 | Moderate | School‐based curriculum (20 sessions) to prevent pregnancy and HIV/STI vs usual education; grade 9 students |

| Condom use at last sex: at 7 months after baseline; at 19 months after baseline |

Reported adjusted OR ± SE: 1.91 ± 0.27 (P = 0.02); 1.68 ± 0.25 (P = 0.04) |

|||

| Frequency of sex without condom in past 3 months: at 7 months after baseline; at 19 months after baseline |

Reported ratio of adjusted means ± SE: 0.50 ± 0.31 (P = 0.03); 0.63 ± 0.23 (P = 0.05) |

|||

| Condom use at last sex (at 6 months after baseline) | Reported adjusted OR 2.12 (1.24 to 3.56) | Coyle 2006 | Moderate | School‐based curriculum (14 sessions) to prevent pregnancy and HIV/STI vs usual activities; alternative high school students Included Theory of Planned Behavior (+ earlier Theory of Reasoned Action) |

| Less frequent sex without condom in past 3 months (at 6 months after baseline) | Reported adjusted MD −1.09 ± SE 0.36; P = 0.002 | |||

| Risk avoidance group, unprotected sex at last sex: at 3 months; > 15 months |

Reported adjusted OR: 0.70 (0.52 to 0.93); 0.61 (0.45 to 0.85) |

Markham 2012 | Moderate | School‐based curriculum (24 sessions) to prevent pregnancy and HIV/STI (through risk avoidance or risk reduction) vs usual education; grade 7 and 8 students Included Theory of Planned Behavior |

| Risk reduction group, unprotected sex at last sex; sex without condom in past 3 months (at 3 months) |

Reported adjusted OR: 0.67 (0.47 to 0.96); 0.59 (0.36 to 0.95) |

|||

| CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; OR: odds ratio; RR: risk ratio; SE: standard error | ||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||

2.

| Motivational interviewing (MI) compared with usual care or handouts for improving contraceptive use | ||||

|

Patient or population: women with need for contraception Settings: clinics primarily Intervention: motivational interviewing Comparison: usual care or handouts | ||||

| Outcomes | Relative effect (95% CI) | Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

| Less use of ineffective contraception: at 1 month; at 4 months |

OR 0.49 (0.28 to 0.87); OR 0.56 (0.31 to 0.98) |

Ceperich 2011 | Moderate | Prevent alcohol‐exposed pregnancy; 1 MI session vs handout; college women, 18 to 24 years old |

| Use of effective contraception in past 3 months: at 3 months; at 9 months |

OR 2.12 (1.53 to 2.92); OR 2.04 (1.47 to 2.83) |

Floyd 2007 | Moderate | Prevent alcohol‐exposed pregnancy; 5 counseling sessions (4 MI + 1 contraceptive) vs pamphlets; women, 18 to 44 years old, from various settings |

| Less use of ineffective contraception (at 3 months) | OR 0.31 (0.12 to 0.77) | Rendall‐Mkosi 2013 | Moderate | Prevent alcohol‐exposed pregnancy; 5 MI sessions vs handouts; women, 18 to 44 years old, from clinics and farms |

| LARC uptake by 4 weeks; LARC use at 3 months |

OR 3.99 (1.36 to 11.68); OR 3.38 (1.06 to 10.71) |

Whitaker 2016 | Moderate | Prevent pregnancy after abortion; 1 MI session vs usual care only; women, 15 to 29 years old, seeking abortion |

|

CI: confidence interval; MI: motivational interviewing; OR: odds ratio; RR: risk ratio LARC: long‐acting reversible contraceptive | ||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||

Background

Description of the condition

Theories and models are useful in identifying factors that influence health behavior and may be modifiable. The intentional testing of theory in research helps expand the knowledge base (Johnston 2008). Interventions based on theory and behavioral change methods are associated with greater intervention effect (Glanz 2010; Webb 2010). Theories and models have been used extensively in HIV research (Fishbein 2000; Albarracín 2005) and in interventions for reducing risk behaviors or promoting sexual health (Tyson 2014; Bailey 2015). Health education interventions may not have an explicit theoretical premise (Borrelli 2011; Amini 2015). Increasingly though, theories and models are being used in designing and implementing health promotion interventions, as the usefulness of theory becomes more apparent (Bailey 2015).

Description of the intervention

Behavioral theory has been used since the 1950s to explain health behavior and guide interventions (Glanz 2010). Many commonly used theories and models in health behavior are based on a social cognition approach (de Wit 2004; Conner 2005). These include the Health Belief Model, Social Cognitive Theory, the Theory of Reasoned Action along with the later Theory of Planned Behavior, and Protection Motivation Theory. Underlying many of the social cognition models is expectancy‐value theory (de Wit 2004; Conner 2005). While individuals make subjective assessments of probability (expectancy) and value (utility), those assessments are combined in a rational way for decision‐making. Such principles may not be sufficient to explain how individuals make decisions (Conner 2005).

According to the Health Belief Model (HBM), one of the earlier theories in health behavior, individuals will take some action to prevent illness if they believe they are susceptible, if the consequences of the illness are severe, and if the benefits of action outweigh the costs (Janz 2002). Like the HBM, the Theory of Reasoned Action (Ajzen 1980; Terry 1993) and the Theory of Planned Behavior (Montaño 2002) assume a rational approach to engaging in new behaviors. However, they emphasize understanding attitudes toward the new health behavior rather than attitude towards the illness itself. The Theories of Reasoned Action (TRA) and of Planned Behavior (TPB) focus on behavioral intention as the best predictor of the behavior. Rational models may not be the most useful in trying to change behavior related to sexual health (Bailey 2015). The Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) states that current behaviors, thoughts and emotions, and environment all interact to affect new behavior (Bandura 1986; Baranowski 2002). The SCT contributed the construct of self‐efficacy, that is, confidence in one’s ability to undertake a specific behavior. Self‐efficacy has been incorporated into several theories and is sometimes used on its own. Having drawn on several theories, the Transtheoretical Model (TTM) (Prochaska 1992) and the AIDS Risk Reduction Model (Catania 1990) suggest that individuals move through different stages before they can maintain complex health behaviors. These models suggest that tailoring interventions could help individuals move from thinking about a new behavior, to trying it, and eventually to adherence. The Information‐Motivation‐Behavior Skills (IMB) Model placed increased attention of the role of motivation in achieving behavior change (Fisher 1992). The strategy of motivational interviewing (MI) helps individuals identify and verbalize their reasons or motivations for change (Miller 2009). From a theoretical standpoint, MI interventions are client‐centered and use techniques that help clients talk about the changes that they would like to see (Miller 2009). MI techniques were first used during counseling sessions to treat heavy drinking. Over three decades, MI has been applied to a wide range of behaviors, and has been used in combination with other theories such as the TTM. I‐Change, an integrated model for explaining the change process, includes principles and constructs from multiple sources, including the Theory of Planned Behavior, SCT, the TTM, the Health Belief Model, and goal‐setting theories (DeVries 2013).

The published reports of intervention research often provide insufficient information to assess the relevance of the intervention to the problem and the adequacy of implementation (intensity and duration). An effort is underway to extend the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials Statement for social and psychological interventions (CONSORT‐SPI) (Montgomery 2013). A tool to assess the fidelity of health behavior interventions was developed for clinical trials (Borrelli 2011). The framework can be useful in reviewing educational interventions. Domains of treatment fidelity include having a curriculum or treatment manual, specifying training of providers, assessing delivery of intervention, and assessing participants' receipt of treatment and ability to use the treatment skills. A Cochrane group developed similar criteria for assessing the integrity of health promotion and public health interventions (Armstrong 2007).

Why it is important to do this review

In this update of our 2013 version, we focus on randomized controlled trials that tested a theory‐based intervention to improve contraceptive use. When we developed the initial review in 2008, theory‐based interventions for contraception had not been systematically examined. One review of interventions to reduce unintended pregnancies among adolescents abstracted the theoretical basis, but not all the strategies addressed specific contraceptive methods (DiCenso 2002). Another discussed the need for learning what types of decision aids for health care work better with certain groups of people, but did not address any theoretical basis (O'Connor 2003). Halpern 2013 studied strategies to improve adherence to hormonal contraceptive regimens. Of trials that tested strategies for communicating contraceptive effectiveness, none had an explicit theoretical base (Lopez 2013). An updated review examined interventions to prevent unintended pregnancies among adolescents (Oringanje 2016). The types of interventions included behavior change programs, but the review did not address theories or models underpinning the programs.

Objectives

To review randomized controlled trials that tested a theoretical approach to inform contraceptive choice and encourage or improve contraceptive use.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that tested an intervention with a theoretical basis for improving contraceptive use for contraception. RCTs were individually randomized or cluster randomized. The use of theories or models had to be explicit, that is, the theory or model had to be named in the report. In addition, the intervention description should have had some evidence of incorporating the theoretical basis, e.g. the constructs used to develop a counseling program.

We excluded trials that focused on preventing sexually transmitted infections (STI) or HIV without also addressing pregnancy prevention. The motivation to prevent disease may differ from that to prevent pregnancy, and consequently the types of theories and models used could also differ. We had included such studies in the initial review but decided to focus on the original intent for the first update.

Types of participants

We included the women in the trials who were users or potential users of the contraceptive methods. We excluded trials that focused on women who are HIV‐positive or high‐risk groups, such as sex workers or women with a known psychiatric or substance abuse disorder.

Types of interventions

The intervention had to address the use of one or more contraceptive methods intended to prevent pregnancy. Any hormonal or non‐hormonal contraceptive could have been the focus, such as oral contraceptives or intrauterine contraception. The theoretical base may have been, but was not limited to, a theory or model of education, communication, or behavior change. The theory‐based intervention could have been compared with a different theory‐based intervention, an intervention without an explicit theoretical base, or usual care. We excluded studies with an intervention focused on abstinence or postponing sexual intercourse for adolescents if they did not include a contraception component.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Included trials had to report at least one of the primary outcomes, as the review focuses on affecting contraceptive use.

Pregnancy (test or self‐report)

Contraceptive use, including initiation or change

Adherence to contraceptive regimen

Contraceptive continuation

Because the review included studies assessing contraception initiation or change, we did not have a minimum time frame for outcome assessment. In 2016 we added a minimum of three months after the intervention began for contraceptive adherence and continuation. We still included any time frame for uptake. For pregnancy, we set the minimum time as six months after the intervention began. We also added criteria for high quality evidence, i.e. 6 months for contraceptive use and 12 months for pregnancy. The longer time frames provide more meaningful outcome measures.

Secondary outcomes

Knowledge of contraceptive effectiveness

Attitude about contraception in general or about a specific contraceptive method

In 2016 we added criteria for assessment of these outcomes, i.e. the minimum time frame was three months or more after the baseline. For high quality evidence, we required at least six months.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

To 1 November 2016, we searched MEDLINE via PubMed, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), POPLINE, and Web of Science for trials that tested an intervention with a theoretical basis for addressing contraceptive use. We searched for recent clinical trials through ClinicalTrials.gov and the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (www.who.int/ictrp/en). Appendix 1 shows the most recent search strategies. Appendix 2 has the strategies for previous searches.

Searching other resources

We examined reference lists of relevant articles and reviews for additional trials. For the initial review, we wrote to investigators for information about other published or unpublished trials not discovered in our search.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

We assessed for inclusion all titles and abstracts identified during the literature search with no language limitation. One author reviewed the search results and identified reports for inclusion or exclusion. A second author also examined the reports identified for appropriate categorization. For studies that appeared eligible for this review, we obtained and examined the full‐text articles. We resolved discrepancies by discussion.

Data extraction and management

Two authors conducted the data extraction. One author entered the data into Review Manager 5 (RevMan 2014), and a second author checked accuracy. These data included the study characteristics, risk of bias, and outcomes. The authors resolved discrepancies through discussion.

We extracted the theoretical basis of the experimental intervention which could be derived from, for example, the fields of education, communication, or behavioral change. The use of theory or models had to be explicit; the theory or model had to be named in the report. In addition, the intervention description should have had some evidence of the theoretical basis, for example what principles or constructs were used to develop a counseling session. The identified theoretical basis can be found in Table 3, along with the constructs or principles reportedly used in the intervention design and implementation.

2. Theoretical basis.

| Study | Theory or model | Principles or constructs |

| Social cognitive theory (SCT) | ||

| Black 2006 | Social cognitive theory | Skills, cultural norms, goal‐setting, self‐efficacy, modeling, family support, mentoring relationships |

| Sieving 2013 | Social cognitive theory; resilience paradigm | Environmental (relationships, involvement, norms), personal (expectations), behavioral (skills) |

| Wight 2002 | Social cognitive theory plus health education principles used by teachers | Self‐efficacy, intentions, behavior planning, normative influence, social and communication skills, gender norms, power |

| Coyle 2001 | Social cognitive theory, social influence theory; models of school change | Knowledge, self‐efficacy, communicate, perceived risks and barriers, perceived peer norms; school organization, staff development, school environment, parent education |

| Coyle 2006 | Social cognitive theory; Theory of Reasoned Action; Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) | Knowledge, attitudes, norms, self‐efficacy, sense of vulnerability, risk, skills |

| Tortolero 2010 | Social cognitive theory, social influence models, and theory of triadic influence | Unclear how used in design other than formative guidance in curriculum development; outcomes assessed relevant concepts Markham 2012, which used this curriculum, was more explicit about theory base |

| Markham 2012 | Social cognitive theory; Theory of Planned Behavior | SCT: personal, environmental, behavioral influences TPB: behavioral and normative beliefs, intentions, behavior Activities to affect behavioral knowledge, self‐efficacy, behavioral and normative beliefs, intentions, environmental factors |

| Raj 2016 | Social cognitive theory; Theory of Gender and Power | Perceive positive outcomes, self‐efficacy, supportive environment; gender power dynamics, social norms, decision making |

| Motivational interviewing (MI) | ||

| Ceperich 2011 | Motivational interviewing | Risk behavior; exercises (decisional balance, development of goal statements and change plans); feedback using "elicit‐provide‐elicit strategy" |

| Floyd 2007 | Motivational interviewing; Transtheoretical model (TTM) | Client‐centered, decisional balance, readiness to change, goal statements and change plans, personalized feedback, problem‐solving, commitment to change |

| Kirby 2010 | Motivational interviewing | Careful and nonjudgmental listening, summarizing, expressing empathy; perceived advantages and disadvantages of behavior change, behavioral expectancies, perceived barriers, reinforcement |

| Petersen 2007 | Motivational interviewing | Empathy, self‐efficacy, perceived barriers, motivation, stage of adopting, improving communication |

| Rendall‐Mkosi 2013 | Motivational interviewing based on Floyd 2007, which also used TTM | Build rapport, assess readiness to change and confidence in ability, develop change plan, implement plan, review counseling experience and progress |

| Whitaker 2016 | Motivational interviewing | Reflective listening; collaborative discussion of benefits and drawbacks of contraceptive methods; avoidance of confrontation |

| Boyer 2005 | Information‐Motivation‐Behavioral Skills Model | Knowledge, attitudes, skills (communication and condom use), risks, decisions |

| Transtheoretical model | ||

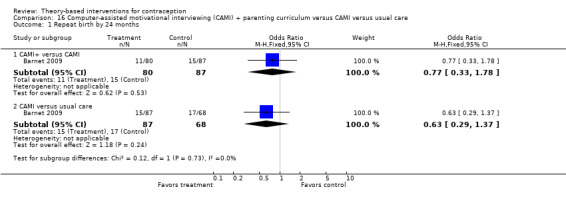

| Barnet 2009 | Transtheoretical model; MI; SCT (parenting curriculum from Black 2006) | Stage of change, intentions, behavior; risk, motivation, change |

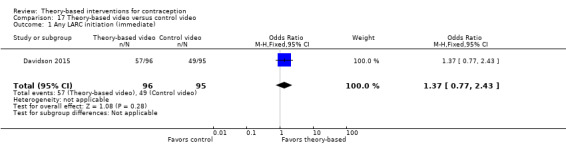

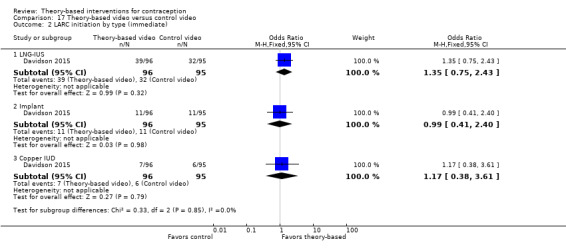

| Davidson 2015 | Transtheoretical model | Assumed precontemplation or contemplation for LARC Increase awareness, weigh pros and cons, gain self‐efficacy; patient narrative with interview questions according to TTM |

| Gold 2016 | Transtheoretical model; MI | TTM: stages of change, decisional balance, self‐efficacy, processes of change MI as counseling strategy: express empathy, develop discrepancy, roll with resistance, support self‐efficacy; discuss feedback and develop plan |

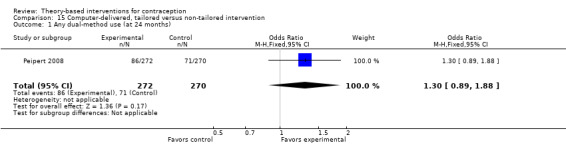

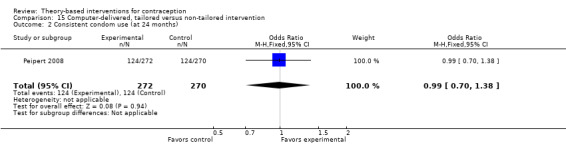

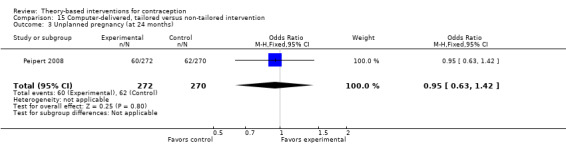

| Peipert 2008 | Transtheoretical model | Stages of change (contemplation, preparation, action, maintenance); decisional balance, self‐efficacy, change processes |

| Additional theories and models | ||

| Schinke 1981 | Cognitive and behavioral training; problem‐solving schema | Decisions, worth and payoff of options, planning, communicate, coach, feedback, contracting |

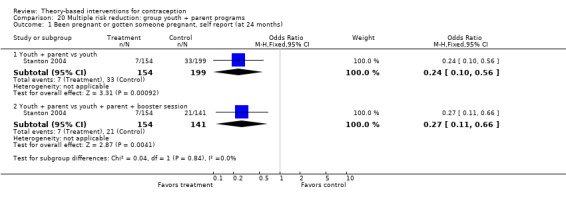

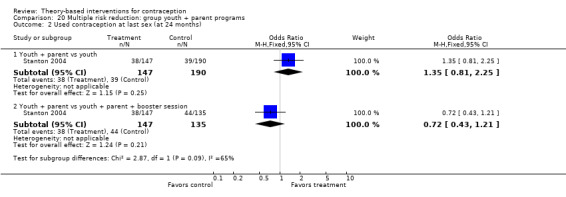

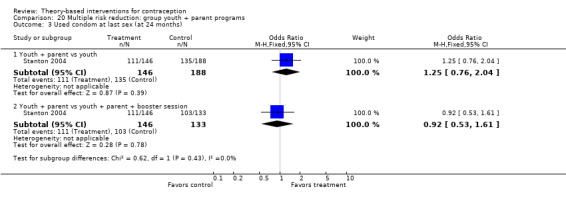

| Stanton 2004 | Protection Motivation Theory | Threat appraisal: extrinsic and intrinsic rewards, perceived severity and vulnerability; coping appraisal: self‐efficacy, response efficacy, response cost |

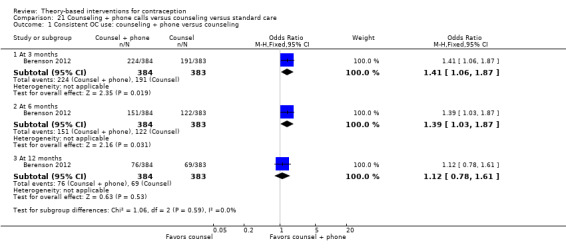

| Berenson 2012 | Health Belief Model | Cues, perceived risk, impact (consequences), benefits of action |

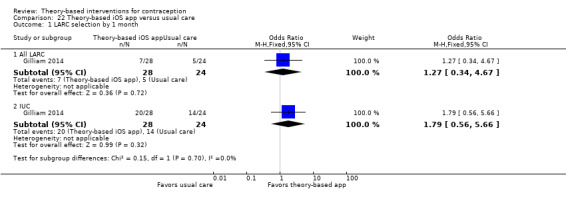

| Gilliam 2014 | Human‐centered design (HCD); Theory of Planned Behavior | HCD: iterative process, rapid low‐fidelity prototyping; stakeholder participation TPB: basis for design unclear; video testimonials, added during testing phase, addressed normative and control beliefs; intended app to raise LARC awareness and interest |

| Taylor 2014 | I‐Change, integrated model | Motivation (affected by predisposing, awareness, information factors), intention (influenced by ability and barriers), behavior |

| Schuler 2015 | C‐Change, social and behavioral change model | Concepts of enabling environment, community organization and services, interpersonal factors, self; issues of information, motivation, ability to act, norms |

MI: motivational interviewing SCT: social cognitive theory TPB: Theory of planned behavior TTM: Transtheoretical model

Intervention fidelity

We used an existing framework to assess the quality of the educational intervention (Borrelli 2011). This framework was developed for assessing treatment fidelity in public health trials of health behavior change. The principles were relevant for this systematic review of behavior change interventions. We examined the trial reports for evidence of intervention (or treatment) fidelity. Domains of treatment fidelity are study design, training of providers, delivery of treatment, receipt of treatment, and enactment of treatment skills. We list the criteria of interest for our review below.

Study design: had a curriculum or treatment manual

Prior training of providers: specified providers' credentials

Project‐specific training: provided standardized training for the intervention

Delivery: assessed providers' adherence to the protocol

Receipt: assessed clients' understanding and skills regarding the intervention (added in 2013)

Information on intervention fidelity came from the primary reports and related design articles (Table 30). For the assessment of evidence quality, we downgraded trials that met fewer than four of the five listed criteria.

1. Intervention fidelity.

| Studya | Curriculum or manual | Provider credentials | Training for intervention | Assessed adherence to protocol | Assessed intervention receipt | Fidelity criteriab |

| Barnet 2009 | Computer‐assisted motivational intervention (CAMI) for study; counseling 20‐min stage‐matched MI; parenting curriculum (Black 2006) | African American paraprofessional women from participants' communities with empathetic qualities, rapport with adolescents, knowledge of community | 2.5 days on Transtheoretical model, motivational interviewing (MI), and CAMI | First 4 months: counselors met biweekly with MI supervisor, who discussed audiotapes, provided feedback |

Not specific: stage‐matched MI |

4 |

| Berenson 2012 | 'Standardization of counseling techniques' (lower literacy handouts, key points, review instructions) | Not specific: Research assistants (RA) | Investigator trained RA in contraceptive counseling | Audio record some sessions for each RA; review for key points | Develop cue for pill‐taking, discuss risks and benefits of pill use, develop plan for side effects, practice condom application | 4 |

| Black 2006 | Curriculum with 19 lessons; order could vary after 2 sessions | 2 Black women, college‐educated, in their 20s, single mothers living independently | Extensive training provided |

Not specific: weekly supervisory sessions |

_ | 4 |

| Boyer 2005 | 4 sessions with educational objectives and strategies; activities and materials | Not specific: research assistants |

Not specific: Trained |

_ | Last session involved describing, practicing, discussing | 2 |

| Ceperich 2011 | Semi‐structured counseling manual with activities and materials | 4 counselors (master's degree in psychology or social work); supervisors experienced in MI training and supervision | Training in motivational interviewing (MI) and counseling manual; reviewed, practiced MI twice per month | Sessions audio‐taped, used in supervision sessions; adjustments made if drifting noted | Sessions involved participant in summarizing, self‐assessment, readiness for change | 5 |

| Coyle 2001 | 20 lessons; grades 9 and 10 (10 lessons each year) | School teachers; in‐class peer leaders for selected activities | Teachers had initial training and ongoing technical support | _ | In‐class peer leaders for some activities, role playing; homework (student‐parent, local resources) | 4 |

| Coyle 2006 | 14‐session curriculum; 9 class lessons and 5 units of service‐learning; pilot‐tested twice | Experienced health educators | Trained to implement; practiced during pilot | _ | Experiential activities, e.g. creating posters, role playing, group discussion, guided skill practice | 4 |

| Davidson 2015 | 3‐segment video for tablet computer | Developers: unspecified for content (presume investigators) + end users; edited by videographers; pilot‐tested | Standard delivery via video | Participants viewed video | _ | 4 |

| Floyd 2007 | Intervention had been tested in feasibility study | 21 counselors (master's level or above) and 6 contraceptive care providers (physicians and family planning nurse practitioners) | _ | Counselors supervised by Project Research team | Participants involved in goals‐setting, change plans, problem solving | 4 |

| Gilliam 2014 | iOS app (15 min) for tablet; designed for project |

Not specific for initial prototype (input from clinicians); tested with women similar to clients; university programmers built iOS prototype |

Standard delivery via app | No information on how women used app | Assessed contraceptive knowledge & LARC interest (post‐intervention; app group only) | 3 |

| Gold 2016 | Computer‐assisted motivational intervention (CAMI); didactic education (DEC) had 3 modules | Developers: unspecified (investigators likely); CAMI counselor not specified; DEC counselor, bachelor's degree layperson |

Standard CAMI delivery; not specified for CAMI counselor |

No information | Participant involved in developing plan for safe behavior; assessed CAMI feasibility and acceptability | 3 |

| Kirby 2010 | Motivational interviewing (MI) guide and training materials | Clinic staff with training on family planning methods, adolescent risk behavior, and counseling | Call content + 3 sessions on MI; observed ≥ 4 calls | Counselors were observed for ≥ 4 calls before conducting solo calls | Interview methods engaged participant in decision‐making | 5 |

| Markham 2012 | 24 sessions (12 per year), 50 min each; based on existing middle school program | Hired for program; most were African American or Hispanic with college degrees; experienced working with adolescents | 5‐day training; skilled trainers modeled lessons, provided teaching practice | Not specific: technical support during implementation | Assessed knowledge and self efficacy about sex and condom use | 4 |

| Peipert 2008 | Computer‐delivered; participants counseled about computer use | Computer‐delivered | Program based on prior system; tested to provide intended feedback | Pre‐tested for delivery of feedback as intended | _ | 4 |

| Petersen 2007 | _ | Experienced health educators trained for this project | 30 to 40 hours | Random observation of sessions and feedback from project manager | Booster session addressed progress and barriers to risk reduction | 4 |

| Raj 2016 | Curriculum 3 sessions with modules | Developers, research team (social science & public health); providers, village health care providers (allopathic or non‐allopathic) | 3 days, FP counseling, gender equity, & partner violence; 2 half‐day boosters | Self‐report only | Review barriers identified, assess discussion of FP with spouse, review FP goals | 4 |

| Rendall‐Mkosi 2013 | Manual developed and used to guide MI sessions: flip chart with alcohol and contraceptive information | Trained lay counselors | _ | Quality control via regular meetings of MI trainer and lay counselor | Participants involved in behavior change plans, implementation, problem solving | 4 |

| Schinke 1981 | 14 group sessions (50 min) for cognitive and behavioral training | Female and male graduate students, 3 to 4 years counseling experience but not with teenagers regarding sex | _ | _ | Sessions involved problem solving, role play, rehearsal | 3 |

| Schuler 2015 | Manual adapted from several sources; 6 sessions with defined activities | APROFAM educators (trained facilitators | Trained to use manual (not specific) | _ | Sessions involved games, role play discussion; study assessed attitudes and knowledge | 4 |

| Sieving 2013 | Case management: monthly core topics each 6 months Peer leadership: training with 15‐session curriculum, group teaching practicum; service learning with standard curriculum |

Case managers (CM) + intervention coordinators: women, aged 22 to 50 years, diverse ethnic and racial backgrounds, bachelor's or master's degree in related field, experience with youth programs |

Not specific for intervention coordinators. CM received training for program and in youth development |

Not specific for intervention coordinators. CM had practice and feedback on strategies, coaching during first group |

CM: adolescent's needs guided specific topics covered | 4 |

| Stanton 2004 | Standard curricula for 3 components, with activities and materials | _ | _ | _ | Involves making decisions, setting goals; includes discussion, homework, role play | 2 |

| Taylor 2014 | 12 weekly lessons with topics and activities; developed with formative research | 2 pairs, young, male and female trained facilitators | _ | _ | Lessons were interactive (role play, discussions, debates, videos) | 3 |

| Tortolero 2010 | 24 lessons (45 min) developed with qualitative work and participatory methods | Trained facilitators | _ | _ | Sessions had computer‐based activities with quizzes, serials with on‐line student feedback, discussion | 3 |

| Whitaker 2016 | Counseling session with 2‐page guide and pictorial guide of FP methods | Counselors (MD‐investigator; licensed social worker) | 2 sessions @ 3 h MI with demonstrations & role play; 5 h encounter & feedback; videotaped; evaluated for competency | Not after training (encounters with professional standardized patients) |

Related to receipt: participant's confidence and readiness to use FP; participant chooses method and helps develop strategy to obtain it; satisfaction with counseling |

4 |

| Wight 2002 | Resource pack of 20 lessons, piloted twice and revised; pilot test had evaluation with teachers and students and lesson observation | Classroom teachers | 5 days | Process evaluation: extent + quality of delivery; who led sessions | Interaction on video with discussion; how to obtain condoms, practice use | 5 |

aIntervention information was assessed with 5 criteria from Borrelli 2011. Those criteria were relevant to completed, rather than ongoing, interventions. bNumber of criteria met by the study, according to information in the reports.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We examined the trials for methodological quality, according to recommended principles (Higgins 2011), and entered the information into the 'Risk of bias' tables. We considered study design, randomization method, allocation concealment, blinding, and losses to follow‐up and early discontinuation. For individually randomized trials, adequate methods for allocation concealment include a centralized telephone system and the use of sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes (Schulz 2002). In cluster randomized trials, clusters are usually randomized all at once, making allocation concealment less of an issue (Campbell 2012; Higgins 2011). However, selection bias may be introduced when individuals are approached for consent after the cluster has been randomized. We presented limitations in design in Risk of bias in included studies and considered them in interpreting the results.

Measures of treatment effect

Outcomes listed in the Characteristics of included studies address the primary and secondary outcomes for this review. Trials reports may have included other outcomes of interest to the investigators.

For unadjusted dichotomous outcomes, we calculated the Mantel‐Haenszel odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI). This applied to an individually randomized trial or a cluster randomized trial that did not adjust for clustering. An example is the proportion of adolescents who used a condom with the last sexual intercourse. Fixed effect and random‐effects give the same result if no heterogeneity exists, as when a comparison includes only one study. We did not have unadjusted continuous outcomes.

Cluster randomized trials may use a variety of strategies to account for the clustering. When available, we used adjusted measures that the investigators considered the primary effect measures. The adjusted odds ratio (OR) is commonly provided for dichotomous outcomes when analyses are obtained using cluster‐adjusted logit models with or without covariates. If an appropriate adjusted OR was unavailable from the report, we considered other effect measures, for example adjusted risk ratio, adjusted difference in proportions, or regression coefficient (adjusted beta). For continuous outcomes, we used the adjusted mean difference (MD), the adjusted beta, or other measure obtained from cluster‐adjusted linear models. Where the investigators used multivariate models, we did not analyze the treatment effect as that would usually require individual participant data. Rather we presented the results from adjusted models as reported by the investigators.

Unit of analysis issues

We included cluster RCTs for which the analysis appeared to account for the cluster effects. Cluster RCTs used various methods of accounting for the clustering, such as multilevel modeling. We give the specific methods in the results for each trial. Most reports did not provide sufficient information to calculate the effective sample size, so we did not analyze the data in this review. For those studies, we present the results as reported by the investigators. Stanton 2004 reported the intraclass correlation coefficients for each outcome and the number of clusters. We calculated the design effects and then effective sample sizes, according to recommended methods (Higgins 2011).

Dealing with missing data

If reports were missing data needed for analysis, we wrote to the study investigators. Responses and any data provided are shown in Characteristics of included studies. We limited our data requests to studies less than 10 years old. Investigators are unlikely to have access to data for older studies.

We wrote to trial investigators to request missing statistics, such as sample sizes for analysis and actual proportions or means for outcomes presented in figures. However, we limited our requests to studies less than 10 years old, as well as trials that had a report within the past five years. Investigators are unlikely to have access to data from older studies. In some cases, we had obtained information from investigators for earlier work that included the studies. If we could not analyze the data due to missing data, we presented the results as reported by the investigators.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We did not combine data from studies with different interventions. Therefore, we were not able to conduct any meta‐analysis due to the variety of behavioral interventions. Heterogeneity is not an issue when a comparison has a single study.

Data synthesis

To assess the quality of evidence and address confidence in the effect estimates, we applied principles from GRADE (Higgins 2011; GRADE 2013). If meta‐analysis is not viable because of varied interventions or outcome measures, a typical 'Summary of findings' table is not feasible. We provide a 'Summary of findings' table for the main results, although we did not conduct a formal GRADE assessment for all outcomes (GRADE 2013).

We assessed the body of evidence based on the quality of evidence from the included trials. Evidence quality includes the design, implementation, and reporting of the intervention and of the trial. The information on intervention fidelity is part of the overall assessment. We considered RCTs to be high quality and then downgraded the evidence based on the criteria below.

Intervention fidelity information for fewer than four criteria

Inadequate randomization sequence generation or allocation concealment, or no information provided for either one

Follow‐up less than 6 months for contraceptive use or less than 12 months for pregnancy

Loss to follow‐up greater than 20%

In 2016, we added the criterion for follow‐up time and deleted the earlier one for self‐reported outcomes; contraceptive use is generally by self‐report. In addition, we lowered the cutoff for losses from 25% to 20%. We examined the trials that provided evidence of moderate quality and showed an intervention effect.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

The 2013 search produced 589 citations: 540 references from the database searches, 5 from other sources, and 44 trials from searches of the clinical trials sites. Three new trials were included along with secondary articles from three previously included trials. We excluded nine studies after reviewing the full text. The remaining references were discarded after reviewing the titles and abstracts or trial summaries.

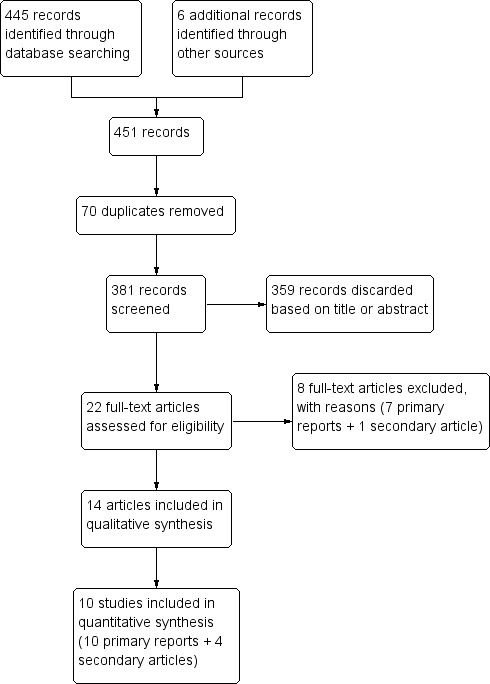

In 2016, the database searches yielded 445 unduplicated references (Figure 1). Another six items came from other sources, i.e. reference lists or other projects for a new total of 451. We removed 70 references electronically or by hand, leaving 381 unduplicated references. After reviewing the full text of 22 articles, we excluded 8 that did not meet the eligibility criteria (7 primary reports plus 1 secondary article). This total does not include the two trials from a previous version of this review that we excluded in this update. We included 14 items, i.e. 10 primary reports from studies that met the criteria plus 4 secondary references. Searches of clinical trials listing produced 62 unduplicated trials. They were either not eligible or from completed studies we had already considered.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

In 2016, we included 10 new trials for a total of 25 (Table 3); 15 randomly assigned individuals and 10 assigned groups (cluster randomized trials). Twenty were conducted in the USA; the other locations were Scotland (Wight 2002), Guatemala (Schuler 2015), India (Raj 2016), and South Africa (Rendall‐Mkosi 2013; Taylor 2014). Participants were generally recruited from primary care sites, family planning clinics, community‐based organizations, and schools.

Trial reports were published from 2001 to 2016, except for one from 1981. Sample sizes for the individual‐randomized trials ranged from 36 to 1155. The cluster‐randomized trials ranged from 817 to 9645 individuals, and the number of clusters ranged from 20 to 35. The effective sample sizes would be smaller due to the assignment of groups rather than individuals.

Most studies provided multiple sessions or contacts with participants. Many interventions involved group sessions, including the school‐based programs. Five studies had a single session for individuals (Petersen 2007; Ceperich 2011; Gilliam 2014; Davidson 2015; Whitaker 2016); four of those focused on young women ranging from 15 to 30 years old. Overall, 12 studies targeted adolescents and 7 included both adolescents and young women.

Intervention focus

Twelve trials focused on contraception: delaying second births (Black 2006; Barnet 2009); reducing risk for alcohol‐exposed pregnancy (Floyd 2007; Ceperich 2011; Rendall‐Mkosi 2013); preventing unplanned pregnancy (Schinke 1981; Gilliam 2014; Taylor 2014; Davidson 2015; Schuler 2015; Raj 2016; Whitaker 2016)

Eleven studies addressed preventing HIV or STI as well as pregnancy (Coyle 2001; Wight 2002; Boyer 2005; Coyle 2006; Petersen 2007; Peipert 2008; Kirby 2010; Tortolero 2010; Berenson 2012; Markham 2012; Gold 2016)

Two addressed multiple risks including sexual risk behavior (Stanton 2004; Sieving 2013)

Outcome measures

Eleven trials assessed pregnancy or births. Seven of those had an objective measure: pregnancy test (Boyer 2005; Petersen 2007; Peipert 2008; Raj 2016), observation of a second child (Black 2006), or record review (Barnet 2009; Berenson 2012). The other four trials used self‐reported pregnancy (Stanton 2004; Coyle 2006; Kirby 2010; Taylor 2014). One had self‐reported pregnancy in the original paper (Wight 2002), but a later article provided data from national records on conceptions and abortions by age 20.

The other outcomes assessed included use of non‐condom or hormonal or effective contraceptives, condom use, and dual‐method use.

Excluded studies

In some cases, the full text indicated that assignment was not random. For some cluster randomized trials, the analysis did not appear to account for clustering effects.

Other reasons for exclusions were that the intervention focused on preventing STI or HIV and did not have a contraception component, the target population was a high‐risk group, the intervention had no explicit theoretical or model base, the study did not have a primary outcome for this review, or the report did not provide outcome data for both study arms.

In 2010, we specified the intervention had to have a contraception component, and excluded 14 of the original trials focusing on STI or HIV prevention (Stanton 1996; Boekeloo 1999; Kalichman 1999; Shain 1999; Hoffman 2003; DiClemente 2004; Jemmott 2005; Morrison‐Beedy 2005; Peragallo 2005; DiIorio 2006; Kiene 2006; Villarruel 2006; Jemmott 2007; Roye 2007).

In 2016, we excluded two previously included trials (Ross 2007; Cowan 2010). After closer examination for another review, the intervention in Ross 2007 did not appear to include contraception. The study focused on prevention of STI, although a later cross‐sectional survey included use of modern contraception as an outcome. For Cowan 2010, nearly half the cohort migrated out of the area. The investigators and data and safety monitoring board changed the design to a cross‐sectional survey, which would otherwise not have been eligible.

Risk of bias in included studies

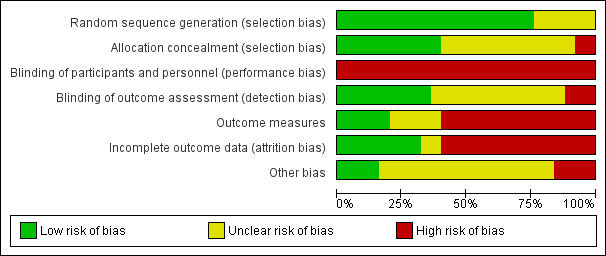

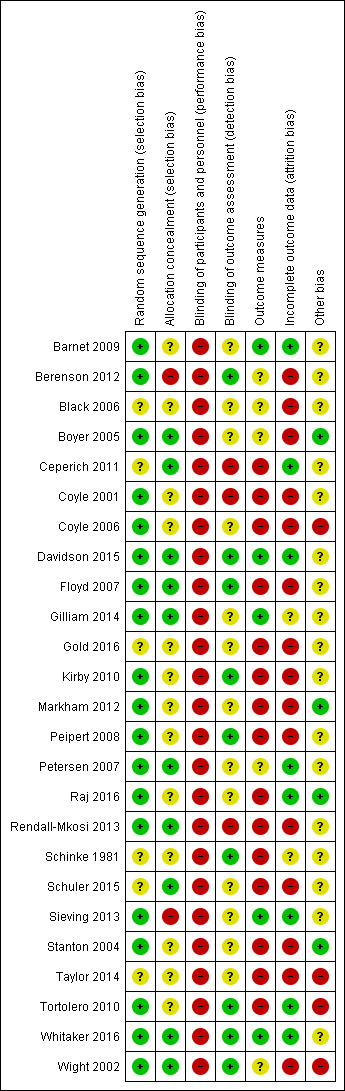

We looked for evidence of intervention fidelity (Table 30), which we included in the assessment of evidence quality (Table 4). Figure 2 illustrates our assessments of risk of bias for the overall review; Figure 3 provides our assessment for each study.

3. Summary of evidence quality.

| Study | Intervention fidelity < 4 items | Randomization and allocation concealment | Follow‐up period | Loss > 20% | Evidence qualitya |

| Social cognitive theory | |||||

| Black 2006 | _ | _ | _ | _ | High |

| Coyle 2001 | _ | _ | _ | −1 | Moderate |

| Coyle 2006 | _ | _ | _ | −1 | Moderate |

| Markham 2012 | _ | _ | _ | −1 | Moderate |

| Raj 2016 | _ | _ | _ | _ | High |

| Sieving 2013 | _ | −1 | _ | _ | Moderate |

| Tortolero 2010 | −1 | _ | _ | _ | Moderate |

| Wight 2002 | _ | _ | _ | −1 | Moderate |

| Motivational interviewing or IMB model | |||||

| Boyer 2005 | −1 | _ | _ | −1 | Low |

| Ceperich 2011 | _ | _ | −1 | _ | Moderate |

| Floyd 2007 | _ | _ | _ | −1 | Moderate |

| Kirby 2010 | _ | _ | _ | −1 | Moderate |

| Petersen 2007 | _ | _ | _ | _ | High |

| Rendall‐Mkosi 2013 | _ | _ | _ | −1 | Moderate |

| Whitaker 2016 | _ | _ | −1 | _ | Moderate |

| Transtheoretical model | |||||

| Barnet 2009 | _ | _ | _ | _ | High |

| Davidson 2015 | _ | _ | −1 | _ | Moderate |

| Gold 2016 | −1 | _ | _ | −1 | Low |

| Peipert 2008 | _ | _ | −1 | −1 | Low |

| Additional theories or models | |||||

| Berenson 2012 | _ | −1 | _ | −1 | Low |

| Gilliam 2014 | −1 | _ | −1 | _ | Low |

| Schinke 1981 | −1 | −1 | _ | _ | Low |

| Schuler 2015 | _ | _ | −1 | −1 | Low |

| Stanton 2004 | −1 | _ | _ | −1 | Low |

| Taylor 2014 | −1 | _ | _ | −1 | Low |

aGrades could be high (RCT), moderate, low, or very low. RCTs downgraded (−1) one level for following: (a) intervention fidelity information for < 4 criteria; (b) randomization sequence generation and allocation concealment: no information on either, or one inadequate; (c) follow‐up < 6 months for contraceptive use or < 12 months for pregnancy; (d) losses > 20%.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study

Allocation

Of 25 included trials, three provided no information on the randomization sequence generation (Schinke 1981; Ceperich 2011; Schuler 2015). Five trials mentioned stratification (Black 2006; Peipert 2008; Kirby 2010; Taylor 2014; Gold 2016).

Of the 14 individually randomized trials, seven provided some detail on allocation concealment (Floyd 2007; Petersen 2007; Ceperich 2011; Rendall‐Mkosi 2013; Gilliam 2014; Davidson 2015; Whitaker 2016). Peipert 2008 referred to concealment but the information was limited. The investigator for Sieving 2013 communicated that they did not use any allocation concealment.

The cluster randomized trials identified the clusters prior to randomization; individuals meeting the inclusion criteria were eligible. We considered the allocation concealment unclear if the report did not indicate whether the recruiters of individuals or the potential participants were aware of the cluster allocation prior to the consent process.

Blinding

Double‐blinding is often not feasible for participants or providers in educational interventions, but the assessors could be blinded to study arm. Eleven trial reports mentioned using blinding. Counselors and clinicians were unaware of allocation in three trials (Gilliam 2014; Davidson 2015; Whitaker 2016). The assessors or interviewers were masked to the participant's assignment in eight studies (Schinke 1981; Wight 2002; Floyd 2007; Peipert 2008; Kirby 2010; Tortolero 2010; Berenson 2012; Whitaker 2016).

Several trials mentioned no use of blinding (Ceperich 2011; Gold 2016; Raj 2016) or noted the difficulty in blinding field workers (assessors) in a rural community (Rendall‐Mkosi 2013).

Incomplete outcome data

Loss to follow‐up was 20% or more for 13 trials: Wight 2002 (31%); Stanton 2004 (40%); Boyer 2005 (38% to 55%); Coyle 2006 (44%); Floyd 2007 (29%); Peipert 2008 (26%); Kirby 2010 (25%); Berenson 2012 (44%); Markham 2012 (27% to 31%); Rendall‐Mkosi 2013 (23% and 26%); Taylor 2014 (11% and 23%); Schuler 2015 (46%); Gold 2016 (34% and 45%). High losses to follow‐up threaten validity (Strauss 2005).

Differential losses between treatment and control groups did not appear to be a major factor. Most trials had similar losses across treatment arms, and one reported the losses did not differ significantly. However, losses in Taylor 2014 were 11% intervention and 23% control.

Selective reporting

In Black 2006, contraceptive use was presented by second birth rather than by randomized group. The investigators presented combined percentages, but claimed there were no differences by second birth or not. However, mothers who did not have a second infant were slightly more likely to plan to use contraceptive at next intercourse.

Effects of interventions

The results are grouped according to the type of theory or model that guided the experimental intervention (Table 3). While several studies used the same theoretical basis for their experimental interventions, the actual programs differed in structure and emphasis, as noted in the Description of studies.

Social Cognitive Theory (SCT)

Eight trials were based on Social Cognitive Theory (Bandura 1986) or SCT plus another theory or model.

Primarily SCT

Three trials based on Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) or Social Learning Theory (SLT) examined a theory‐based intervention versus usual care (or program). One assigned schools to conditions in Scotland, while two USA trials randomized individuals. The participants were adolescents in all three studies. The interventions provided multiple sessions and lasted 18 months to two years.

A cluster randomized trial used a school‐based curriculum. Wight 2002 was based on SLT and incorporated educational principles familiar to teachers to enhance acceptability. The 7616 participants were 13 to 15 years old and attending state schools in Scotland. The program included active learning and skill development in 20 sessions over two years. The control group received the usual sex education. To assign schools to treatment groups, the investigators selected an allocation from the set of 20,000 possible allocations, which provided the best balance of school‐level measures. To analyze the outcome of unwanted pregnancy, the investigators used a random effects logistics regression. For the other outcomes they used a randomization test, based on all the possible allocations from which they selected the final allocation. The investigators based the analysis of behavioral outcomes at six months on a subsample of those who were sexually experienced, a variable that the intervention could affect. Since they did not include all students in the randomized groups, those comparisons were not randomized comparisons. At six months postprogram (or 24 months from baseline), the intervention and comparison groups did not differ significantly for oral contraceptive (OC) use during last intercourse or self‐reported unwanted pregnancy (Analysis 1.1), first intercourse without condom use or no condom use during most recent intercourse (Analysis 1.2). By linking records from the National Health Service, the investigators examined pregnancies by age 20, approximately 4.5 years after the intervention. The termination data included live births, stillbirths, abortions, and miscarriages. The groups did not differ significantly in conceptions or terminations (Analysis 1.3).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Pregnancy prevention curriculum versus usual sex education, Outcome 1 Pregnancy and oral contraceptive use at 6 months postprogram (24 months).

| Pregnancy and oral contraceptive use at 6 months postprogram (24 months) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Outcome | Gender | N | Intervention Reported % (n) | Control Reported % (n) | Reported adjusted difference (95% CI) |

| Wight 2002 | Unwanted pregnancy (self report) | Young women | 2117 | 4.0% (48) | 3.8% (35) | 1.0 (0.6 to 1.8) |

| Wight 2002 | OC use during last sex | Young men | 876 | 18.7% (79) | 21.2% (96) | ‐2.5 (‐8.0 to 2.9) |

| Wight 2002 | OC use during last sex | Young women | 1269 | 30.4% (196) | 28.0% (175) | 2.4 (‐4.1 to 8.9) |

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Pregnancy prevention curriculum versus usual sex education, Outcome 2 Condom use at 6 months postprogram (24 months).

| Condom use at 6 months postprogram (24 months) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Outcome | Gender | N | Intervention Reported % (n) | Control Reported % (n) | Reported adjusted difference (95% CI) |

| Wight 2002 | First‐time sex without condom after 1st program year | Young men | 2323 | 5.2% (57) | 5.7% (70) | ‐0.5 (‐2.5 to 1.5) |

| Wight 2002 | First‐time sex without condom after 1st program year | Young women | 2629 | 9.7% (127) | 9.1% (120) | 0.6 (‐1.9 to 3.1) |

| Wight 2002 | No condom during last sex | Young men | 876 | 33.6% (142) | 34.9% (158) | ‐1.3 (‐5.9 to 3.3) |

| Wight 2002 | No condom during last sex | Young women | 1269 | 44.9% (289) | 44.0% (275) | 0.9 (‐5.7 to 7.4) |

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Pregnancy prevention curriculum versus usual sex education, Outcome 3 Outcomes by age 20 (women, 4.5 years postprogram).

| Outcomes by age 20 (women, 4.5 years postprogram) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Outcome | Intervention rate/1000 | Control rate/1000 | Reported adjusted difference (95% CI) |

| Wight 2002 | Termination events | 126.6 | 112.0 | 15.7 (‐10.7 to 42.1) |

| Wight 2002 | Conception events (live births, stillbirths, therapeutic terminations, miscarriages) | 300.2 | 273.8 | 31.9 (‐16.1 to 79.9) |

| Wight 2002 | Had > 1 termination | 108.9 | 104.3 | 5.6 (‐16.0 to 27.2) |

| Wight 2002 | Had > 1 conception | 222.6 | 216.8 | 9.7 (‐21.8 to 41.2) |

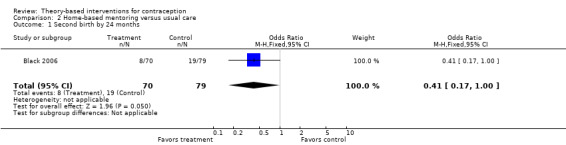

In Black 2006 (N = 181), the intervention group had multiple contacts over two years. The home‐based curriculum for new adolescent mothers included a maximum of 19 lessons. Content included information about access to birth control and condoms provided at each visit. The adolescents in the treatment group were less likely to have had a second birth within two years than the usual care group (OR 0.41, 95% CI 0.17 to 1.00) (Analysis 2.1). Second births were assessed during home visits. Report had results for contraceptive use by second birth and not by randomized group.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Home‐based mentoring versus usual care, Outcome 1 Second birth by 24 months.

For Sieving 2013 (N = 253), the 18‐month intervention involved case management as well as a peer‐leadership program for sexually active adolescent girls. Besides SCT, the investigators used a resilience paradigm and principles of social connectedness. They adjusted the analysis for baseline values and intercorrelation among participants recruited from the same clinic using a generalized estimating equation model. Compared with the control group, the intervention group reported greater consistency of use for the outcomes below.

Condoms at 12 and 24 months: reported adjusted relative risk (RR) 1.45 (95% CI 1.26 to 1.67); RR 1.57 (95% CI 1.28 to 1.94) (Analysis 3.1)

Hormonal contraceptives: at 12 months, RR 1.46 (95% CI 1.13 to 1.89); at 18 months, RR 1.36 (95% CI 1.02 to 1.83); at 24 months, RR 1.30 (95% CI 1.06 to 1.58) (Analysis 3.2)

Dual methods (OCs plus condoms): at 12 months, RR 1.58 (95% CI 1.03 to 2.43); at 24 months, RR 1.36 (95% CI 1.01 to 1.85) (Analysis 3.3)

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Case management + peer leadership versus usual care, Outcome 1 Consistency of condom use.

| Consistency of condom use | ||

|---|---|---|

| Study | Assessment | Reported adjusted relative risk (95% CI) |

| Sieving 2013 | 12 months | 1.45 (1.26 to 1.67) |

| Sieving 2013 | 18 months | 1.10 (0.73 to 1.68) |

| Sieving 2013 | 24 months | 1.57 (1.28 to 1.94) |

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Case management + peer leadership versus usual care, Outcome 2 Consistency of hormonal contraceptive use.

| Consistency of hormonal contraceptive use | ||

|---|---|---|

| Study | Assessment | Reported adjusted relative risk (95% CI) |

| Sieving 2013 | 12 months | 1.46 (1.13 to 1.89) |

| Sieving 2013 | 18 months | 1.36 (1.02 to 1.83) |

| Sieving 2013 | 24 months | 1.30 (1.06 to 1.58) |

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Case management + peer leadership versus usual care, Outcome 3 Consistency of dual‐method use.

| Consistency of dual‐method use | ||

|---|---|---|

| Study | Assessment | Reported adjusted relative risk (95% CI) |

| Sieving 2013 | 12 months | 1.58 (1.03 to 2.43) |

| Sieving 2013 | 18 months | 1.08 (0.78 to 1.50) |

| Sieving 2013 | 24 months | 1.36 (1.01 to 1.85) |

At 30 months in Sieving 2013, the intervention group reported more consistent use of condoms (reported adjusted risk ratio (ARR) 1.67, 95% CI 1.39 to 2.00) and dual methods (reported ARR 2.28, 95% CI 1.31 to 3.97) (Analysis 3.4). The groups did not differ significantly for hormonal methods. The study arms did not differ significantly for desire to use contraception at 12, 18, or 24 months (Analysis 3.5).

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Case management + peer leadership versus usual care, Outcome 4 Months of consistent use in past 7 months (at 30 months).

| Months of consistent use in past 7 months (at 30 months) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Method | N | Reported adjusted risk ratio (95% CI) |

| Sieving 2013 | Condoms | 199 | 1.67 (1.39 to 2.00) |

| Sieving 2013 | Hormonal methods | 198 | 1.52 (0.85 to 2.71) |

| Sieving 2013 | Dual methods (hormonal + condoms) | 198 | 2.28 (1.31 to 3.97) |

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Case management + peer leadership versus usual care, Outcome 5 Attitude: desire to use contraception.

| Attitude: desire to use contraception | ||

|---|---|---|

| Study | Assessment | Reported adjusted OR (95% CI) |

| Sieving 2013 | 12 months | 1.62 (0.81 to 3.27) |

| Sieving 2013 | 18 months | 1.18 (0.96 to 1.46) |

| Sieving 2013 | 24 months | 1.17 (0.77 to 1.77) |

SCT plus another theory or model

The interventions in five trials were based on social cognitive theory plus another theory or model. All randomized clusters rather than individuals. The four school‐based programs for adolescents took place in the USA; one lasted 5 to 7 weeks while the others were provided over two school years. The fifth study took place in India with young couples. The intervention involved three sessions.

The school‐based curriculum in Coyle 2001 incorporated social cognitive theory, social influence theory, and models of school change. The 20 randomized schools had 3869 students who completed baseline surveys. The intervention addressed using condoms and other contraception and included 20 sessions, divided between grades 9 and 10. The program also included school organization activities and parent education. The comparison group received the standard five‐session curriculum and some school activities. The locations were in southeast Texas and northern California (USA). This cluster randomized trial accounted for the cluster effects in the analysis by using multilevel models adjusted for baseline responses for outcomes, geographic area, and unspecified covariates related to the outcome and intervention condition. The investigators conducted assessments immediately after intervention years 1 and 2 as well as 12 months after year 2. The intervention group had more favorable outcomes than the comparison group. Results below are from assessments at 7 and 19 months after baseline (i.e. after year 1 sessions and 12 months after year 2 sessions), unless otherwise specified.

Intervention group versus comparison group

Was more likely to report using an effective method of contraception at last intercourse (condoms, OCs, or both): reported adjusted OR 1.62 ± standard error (SE) 0.22 (P = 0.03); reported adjusted OR 1.76 ± SE 0.29 (P = 0.05) (Analysis 4.1).

Was more likely to report using a condom during last intercourse: reported adjusted OR 1.91 ± SE 0.27 (P = 0.02); reported adjusted OR 1.68 ± SE 0.25 (P = 0.04) (Analysis 4.2).

Was more likely to report a lower frequency of sex without condom use in the past three months: reported ratio of adjusted means 0.50 ± SE 0.31 (P = 0.03); reported ratio of adjusted means 0.63 ± SE 0.23 (P = 0.05) (Analysis 4.2).

Had a higher mean for positive attitudes about condoms 7 months after baseline (reported MD 0.10 ± SE 0.03; P < 0.01) and year 2 (reported MD 0.07; P < 0.01) and 19 months after baseline (reported MD 0.07 ± SE 0.02; P = 0.01) (Analysis 4.3).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Curriculum to prevent pregnancy, HIV, and STI versus standard sex education, Outcome 1 Effective protection against pregnancy.

| Effective protection against pregnancy | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Outcome | Assessment | N | Reported adjusted OR ± SE | Reported P |

| Coyle 2001 | Use of effective protection against pregnancy at last sex (condom, OCs, or both) | After 9th‐grade lessons (7 months after baseline) | 998 | 1.62 ± 0.22 | 0.03 |

| Coyle 2001 | _ | After 10th‐grade lessons (19 months after baseline) | _ | 1.40 (no SE reported) | 0.38 |

| Coyle 2001 | _ | 12 months after year 2 (31 months after baseline) | 549 | 1.76 ± 0.29 | 0.05 |

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Curriculum to prevent pregnancy, HIV, and STI versus standard sex education, Outcome 2 Condom use.

| Condom use | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Outcome | Assessment | N | Reported adjusted effect ± SE | Reported P |

| Coyle 2001 | Condom use at first sex (initiators only) | After 9th‐grade lessons (7 months after baseline) | 285 | OR 0.68 ± 0.48 | 0.42 |

| Coyle 2001 | _ | After 10th‐grade lessons (19 months after baseline) | _ | OR 1.23 (no SE reported) | 0.52 |

| Coyle 2001 | _ | 12 months after year 2 (31 months after baseline) | 733 | OR 1.44 ± 0.27 | 0.17 |

| Coyle 2001 | Condom use at last sex | After 9th‐grade lessons | 1018 | OR 1.91 ± 0.27 | 0.02 |

| Coyle 2001 | _ | After 10th‐grade lessons | _ | OR 1.51 (no SE reported) | 0.26 |

| Coyle 2001 | _ | 12 months after year 2 | 549 | OR 1.68 ± 0.25 | 0.04 |

| Coyle 2001 | Frequency of sex without condom in past 3 months | After 9th‐grade lessons | 963 | Ratio of adjusted means (RM) 0.50 ± 0.31 | 0.03 |

| Coyle 2001 | _ | After 10th‐grade lessons | _ | RM 0.69 (no SE reported) | 0.14 |

| Coyle 2001 | _ | 12 months after year 2 | 1371 | RM 0.63 ± 0.23 | 0.05 |

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Curriculum to prevent pregnancy, HIV, and STI versus standard sex education, Outcome 3 Attitudes toward condoms.

| Attitudes toward condoms | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Assessment | N | Reported adjusted MD ± SE | Reported P |

| Coyle 2001 | After 9th‐grade lessons (7 months after baseline) | 3510 | 0.10 ± 0.03 | < 0.01 |

| Coyle 2001 | After 10th‐grade lessons (19 months after baseline) | _ | 0.07 (no SE reported) | < 0.01 |

| Coyle 2001 | 12 months after year 2 (31 months after baseline) | 3751 | 0.07 ± 0.02 | 0.01 |

For Coyle 2006, the school‐based curriculum was based on SCT and the Theory of Planned Behavior, which extended the earlier Theory of Reasoned Action. The program included nine sessions of skill‐based learning plus five service‐learning activities in 24 alternative day schools in northern California (USA). The comparison group received the usual prevention activities for HIV, STI, and pregnancy. The schools served high school students with severe discipline issues, substance use, or chronic absenteeism. This cluster RCT accounted for the cluster effects in the analysis by using multilevel models adjusted for baseline responses on outcomes and unspecified covariates related to the outcome and intervention condition. The study included 988 participants. The investigators based the analysis of behavioral outcomes on a subsample that reported ever having sex, a variable that the intervention could affect. Since they did not include all those randomized, we did not consider the comparisons to be randomized comparisons. The assessments at 6, 12, and 18 months after baseline were conducted about 5, 11, and 17 months postprogram.

The study arms did not differ significantly for self‐reported pregnancy or using an effective method of pregnancy prevention at last sex (Analysis 5.1; Analysis 5.2).

At 5 months but not 11 or 17 months, the intervention group was more likely than the usual‐activity group to report having used a condom during last intercourse (reported adjusted OR 2.12, 95% CI 1.24 to 3.56) (Analysis 5.3) and less frequent sex without a condom in the past three months (reported adjusted MD −1.09 ± SE 0.36; P = 0.002) (Analysis 5.4).

The intervention group had a higher mean for condom knowledge at 5 months (reported MD 0.055 ± SE 0.028; P = 0.05) and at 17 months (reported adjusted MD 0.060 ± 0.030; P = 0.04) (Analysis 5.5).

The two groups did not differ significantly in their attitudes about condoms (Analysis 5.6).

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Curriculum to prevent HIV, STI, and pregnancy versus usual prevention activities (in alternative schools), Outcome 1 Pregnancy (self report).

| Pregnancy (self report) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Assessment (postprogram) | N | Reported adjusted OR (95% CI) | Reported P |

| Coyle 2006 | 5 months | 308 | 0.61 (0.33 to 1.12) | 0.11 |

| Coyle 2006 | 11 months | _ | 1.15 (no CI reported) | 0.66 |

| Coyle 2006 | 17 months | _ | 0.84 (no CI reported) | 0.61 |

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Curriculum to prevent HIV, STI, and pregnancy versus usual prevention activities (in alternative schools), Outcome 2 Effective pregnancy prevention at last sex.

| Effective pregnancy prevention at last sex | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Assessment (postprogram) | N | Reported adjusted OR (95% CI) |

| Coyle 2006 | 5 months | 527 | 1.15 (0.78 to 1.70) |

| Coyle 2006 | 11 months | 460 | 1.12 (0.74 to 1.66) |

| Coyle 2006 | 17 months | 417 | 0.77 (0.49 to 1.23) |

5.3. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Curriculum to prevent HIV, STI, and pregnancy versus usual prevention activities (in alternative schools), Outcome 3 Condom use at last sex.

| Condom use at last sex | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Assessment (postprogram) | N | Reported adjusted OR (95% CI) |

| Coyle 2006 | 5 months | 469 | 2.12 (1.24 to 3.56) |

| Coyle 2006 | 11 months | 386 | 0.88 (0.50 to 1.55) |

| Coyle 2006 | 17 months | 359 | 1.00 (0.49 to 2.02) |

5.4. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Curriculum to prevent HIV, STI, and pregnancy versus usual prevention activities (in alternative schools), Outcome 4 Frequency of sex without condom use in past 3 months.

| Frequency of sex without condom use in past 3 months | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Assessment (postprogram) | N | Reported adjusted MD ± SE | Reported P |

| Coyle 2006 | 5 months | 412 | ‐1.09 ± 0.36 | 0.002 |

| Coyle 2006 | 11 months | 328 | 0.18 ± 0.34 | 0.6 |

| Coyle 2006 | 17 months | 289 | 0.38 ± 0.39 | 0.33 |

5.5. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Curriculum to prevent HIV, STI, and pregnancy versus usual prevention activities (in alternative schools), Outcome 5 Condom knowledge.

| Condom knowledge | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Assessment (postprogram) | N | Reported adjusted MD ± SE | Reported P |

| Coyle 2006 | 5 months | 532 | 0.055 ± 0.028 | 0.05 |

| Coyle 2006 | 11 months | 449 | 0.026 ± 0.029 | 0.4 |

| Coyle 2006 | 17 months | 411 | 0.060 ± 0.030 | 0.04 |

5.6. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Curriculum to prevent HIV, STI, and pregnancy versus usual prevention activities (in alternative schools), Outcome 6 General attitudes toward condoms.

| General attitudes toward condoms | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Assessment (postprogram) | N | Reported adjusted MD ± SE | Reported P |

| Coyle 2006 | 5 months | 527 | 0.086 ± 0.061 | 0.16 |

| Coyle 2006 | 11 months | 451 | 0.035 ± 0.052 | 0.5 |

| Coyle 2006 | 17 months | 413 | ‐0.044 ± 0.066 | 0.5 |

Two USA studies used variations of the same curriculum and provided 24 sessions across grades 7 and 8.