Abstract

Background

LGBT populations use tobacco at disparately higher rates nationwide, compared to national averages. The tobacco industry has a history targeting LGBT with marketing efforts, likely contributing to this disparity. This study explores whether exposure to tobacco content on traditional and social media is associated with tobacco use among LGBT and non-LGBT.

Methods

This study reports results from LGBT (N = 1092) and non-LGBT (N = 16430) respondents to a 2013 nationally representative cross-sectional online survey of US adults (N = 17522). Frequency and weighted prevalence were estimated and adjusted logistic regression analyses were conducted.

Results

LGBT reported significantly higher rates of past 30-day tobacco media exposure compared to non-LGBT, this effect was strongest among LGBT who were smokers (p < .05). LGBT more frequently reported exposure to, searching for, or sharing messages related to tobacco couponing, e-cigarettes, and anti-tobacco on new or social media (eg, Twitter, Facebook, etc.) than did non-LGBT (p < .05). Non-LGBT reported more exposure from traditional media sources such as television, most notably anti-tobacco messages (p = .0088). LGBT had higher odds of past 30-day use of cigarettes, e-cigarettes, and cigars compared to non-LGBT, adjusting for past 30-day media exposure and covariates (p ≤ .0001).

Conclusions

LGBT (particularly LGBT smokers) are more likely to be exposed to and interact with tobacco-related messages on new and social media than their non-LGBT counterparts. Higher levels of tobacco media exposure were significantly associated with higher likelihood of tobacco use. This suggests tobacco control must work toward reaching LGBT across a variety of media platforms, particularly new and social media outlets.

Implications

This study provides important information about LGBT communities tobacco-related disparities in increased exposure to pro-tobacco messages via social media, where the tobacco industry has moved since the MSA. Further, LGBT when assessed as a single population appear to identify having decreased exposure to anti-tobacco messages via traditional media, where we know a large portion of tobacco control and prevention messages are placed. The study points to the need for targeted and tailored approaches by tobacco control to market to LGBT using on-line resources and tools in order to help reduce LGBT tobacco-related health disparities. Although there have been localized campaigns, only just recently have such LGBT-tailored national campaigns been developed by the CDC, FDA, and Legacy, assessment of the content, effectiveness, and reach of both local and national campaigns will be important next steps.

Introduction

Although a growing body of evidence now indicates tobacco-related disparities by gender, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic status, evidence has only begun to emerge demonstrating disparities by lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) status,1–3 with almost no such research based on nationally representative samples.1 It is vital that public health researchers, tobacco control professionals, and LGBT advocates better understand LGBT populations’ staggering risk for tobacco use compared to non-LGBT. More importantly, there continues to be scant research examining disparities within disaggregated LGBT groups.1 These disparities in tobacco use may contribute to a disproportionate burden of tobacco-related diseases among LGBT populations.

A well-established predictor of tobacco-related attitudes and behaviors across products is exposure to and interaction with tobacco-related messages, a finding particularly well-documented among young and vulnerable populations.4–7 Evaluating tobacco marketing targeting LGBT is particularly important because the tobacco industry was among the first trade groups to specifically identify and directly advertise to LGBT as a viable target market.8–12 Yet, LGBT have historically been overlooked by the tobacco control community and prevention efforts have only recently begun to focus on these populations.13,14 Taken together, early attention from the tobacco industry and relatively late attention from the tobacco control community likely have contributed to the disproportionate tobacco use rates among various LGBT populations.

The scientific literature on the impact of anti-tobacco messaging on LGBT tobacco-related behaviors is sparse.15 Data from the National Adult Tobacco Survey (2009–2010) indicated that the majority of both LGBT and non-LGBT (eg, heterosexuals) had seen at least one tobacco cessation ad in the past 30 days (ranging from 86.2% to 95.6%), and did not observe significant differences between groups.16 However, the same study indicated that among current smokers, gay and bisexual adult men reported less awareness of smoking quitlines compared to their heterosexual counterparts (no such differences by sexual orientation were found for females).16 This study did not report on source of exposure or frequency of exposure to smoking cessation ads. Further, this study did not assess other types of tobacco control and prevention content, such as anti-tobacco messages focused on prevention.

Evidence suggests that LGBT are more frequently exposed to generalized anti-tobacco messaging rather than LGBT-targeted messages on LGBT-specific media sources (eg, LOGO, OUT Magazine, etc.).17 This is problematic considering that the tobacco industry has routinely tailored advertisements to LGBT as well as placed those advertisements in media sources primarily consumed by LGBT individuals (eg, LGBT magazines, PRIDE events).8,9,12,18 The extent to which LGBT and non-LGBT are differentially exposed to tobacco-related content on traditional and new media remains particularly unclear.

In order to better understand LGBT tobacco-related disparities and inform future tobacco control intervention efforts, it is important to identify the extent to which LGBT and non-LGBT are exposed to tobacco-related content on both traditional and new (eg, social or internet-based) media and whether or not such exposure is differentially associated with tobacco use among LGBT and non-LGBT populations. It is also important to identify the channels through which tobacco-related exposures occur (eg, traditional television, radio, print publications, or social media websites) to correctly identify the most appropriate media outlets to reach LGBT populations and potentially inform policy efforts addressing tobacco advertising on communication media that remain under the radar of tobacco control, such as social networking websites. The current research examines these issues and can lead to improved prevention and intervention efforts to reduce tobacco-related disparities that many LGBT populations experience.

Methods

Data

Data were collected as part of an online survey developed by our research team and fielded by the GfK Group (GfK, formerly Knowledge Networks) in February–March, 2013.

Sample

The sample is comprised of US adults aged 18 and older who completed this survey. The majority of participants (75%) were drawn from GfK’s KnowledgePanel® (KP),19 a probability-based sample of adults recruited based on a combination of random digit dialing and address-based sampling schemes. Cell phone only households were included in the addressed based sampling. In case selected households did not have computer and internet access to complete surveys, they were provided with equipment. Of the 34097 KP members, 61% completed screening for eligibility and 97% of those eligible completed the survey. KP members are given a modest incentive to encourage participation, with incentive points for survey completion that are redeemable for cash (Respondents received 5000 points for completing a 25-min survey like TCME, and 5000 points were equivalent to $5). KP members provided with equipment did not participate in the incentive program. Tobacco users were oversampled to ensure sufficient sample size for key demographic groups with a goal of 50% tobacco users and 50% nontobacco users.

Due to oversampling tobacco users at a higher level than tobacco use prevalence in the United States, the smokers in the panel was exhausted in small population areas and it was necessary to collect additional participants (Off-panel participants). To augment the KP sample (75%), GfK collected an off-panel convenience sample (25%) by screening people who clicked on online ads for study eligibility, which was then blended with the probability sample based on KnowledgePanel Calibration.20 GfK recruited the off-panel convenience sample utilizing banner ads, web pages, and e-mail invitations. Off-panel respondents volunteered to participate in the research, in exchange for a modest incentive; diverse incentives—cash, points, prizes, sweepstakes, or charity donation—were offered to increase diversity of participants. Respondents were screened for tobacco-use and demographic characteristics. Off-panel participants are not necessarily representative of the population. In order to account for this, GfK uses a calibration strategy that utilizes off-panel and KnowledgePanel response screeners to weight the off-panel sample to more closely approximate a representative sample. Qualified KP responded and off-panel responded were weighted to look like the eligible panel respondents by controlling the demographics (eg, age, race, ethnicity, education, household income, and media markets) within tobacco users and nonusers. The weights have been trimmed separately within tobacco users and nonusers and scaled to sum to the sample size of qualified respondents and qualified tobacco users/nonusers separately. Because there was no sampling frame, response rates for the convenience sample are not available. The probability and convenience sample were combined to create 100% of the sample described in this study. All participants were asked the same questions. All respondents provided online consent prior to participation.

Weighting adjustments were made in order to compensate for deviations from equal probability sampling. Post-stratification weights were developed to account for nonresponse, over-sampling of tobacco users, calibration of off-panel respondents, and other sources of nonsampling error. The target sample size of 15000 was initially determined to achieve at least 80% power for detecting differences between smokers and nonsmokers in the means of outcome measures in each priority population, assuming 0.05 significance level and equal number of smokers and nonsmokers. In the effort of ensuring sufficient number of tobacco users, we ended up exceeding the target sample size; that provided sufficient precision for estimates of relatively uncommon measures (such as smoking-related information exposure, seeking, and exchange behaviors). Observations with missing data for variables of interest were minimal (<2%) and thus omitted from the analyses. Additional descriptions of the projects methods and sampling have been described previously.1,19,21,22

The resulting sample includes 17522 participants, with 1092 self-identified LGBT respondents and 16430 heterosexual (non-LGBT) respondents. The study received institutional review board approval.

Measures

This study was developed for the purpose of studying the use of tobacco and media. Most survey items included are from previously validated studies, with a series of questions developed specifically for the purposes of this study. Study questions and sources are described in detail below.

Sexual Orientation

Participants’ self-reported their sexual orientation (heterosexual or straight, gay, lesbian, bisexual, other). Those who selected “other” were prompted to describe their sexual orientation in text, which responses were coded independently by two research team members to explore LGB relevance. In the case of disagreement, coders discussed and came to consensus about LGB inclusion or exclusion. Apparent descriptions were used to further classify them into one of the groups or exclude (eg, those who refused to identify or provided vague descriptions). Sexual orientation was then dichotomized into those identifying as lesbian, gay, or bisexual (LGB) and those who identified as heterosexual or straight.

Gender Identity

Participants self-reported gender identity by responding either yes or no to the question “Do you consider yourself to be transgender?”

LGBT Status

Dichotomized gender identity and sexual orientation were cross-compared. Participants identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual, and/or transgendered were included in the LGBT category. Participants identifying as heterosexual or straight who did not also identify as transgender were included in the non-LGBT category. Respondents refusing to answer either question on sexual orientation or gender identity were excluded from the analysis. The sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) questions were developed for this study, following recommendations on best and promising practices for collecting data on SOGI.23,24

Exposure to and Interaction with Tobacco-Specific Media Content

Participants responded to a series of questions developed specifically for this study to indicate whether or not they had seen or heard about a type of tobacco-related content (eg, coupons or discounts, e-cigarettes, and anti-smoking ads) ever (lifetime) and in the past 30 days. Specifically, respondents were asked “Have you ever seen/heard, searched for, or shared information (on television, on the radio, or online) about any of the following topics?: Cigarettes or other tobacco products, Coupons or discounts for buying tobacco products, E-cigarettes, Anti-smoking ads.” For each, respondents selected which best matched their recalled experience as to whether or not they had “Seen/Heard,” “Searched for,” “Shared,” and/or “Have NOT EVER seen/heard/searched/shared.” Those who responded yes to ever exposure, were then asked about past 30-day exposure: “During the past 30 days, how many times have you SEEN/HEARD information about the following topics?” with responses: “Not in past 30 days, 1–2 times, 3–5 times, 6–10 times, More than 10 times” that were later dichotomized. Similarly, participants responded to separate questions about whether they had searched for or shared tobacco-related content ever or in the past 30 days. Participants who reported past 30-day exposure to, searching for, or sharing of tobacco-related coupons or discounts, e-cigarettes, or anti-tobacco messages were asked the follow-up question, “When you SAW/HEARD information on [INSERT RESPONSE SEEN/HEARD] during the past 30 days, on which of the following media did you see or hear it?” with response options including: “regular television, the radio, video streaming websites such as Hulu, Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, Tumblr, e-mail, internet search engines, online news sources, some other social networking site, banner ads, text message, and/or word of mouth.” Similarly worded questions were asked for those who reported searching for or sharing such content.

Tobacco Use

Participants responded to questions regarding lifetime (ever) use of tobacco products25(p): cigarettes, e-cigarettes [e-cigs], regular cigars, cigarillos, and little cigars. Participants who stated they were ever users of a product were then asked “Do you now use [tobacco product] every day, some days, or not at all?”26 Responses were dichotomized as current use or no current use. Those who self-reported having never tried the tobacco product or who reported trying but not currently using the tobacco product were categorized as noncurrent users of the product; those who reported currently using the tobacco product some days or every day were categorized as current users. Small and medium cigar categories were combined into one variable (also called small cigars/cigarillos). Any current tobacco use was inferred if respondents reported using either cigarettes, e-cigarettes, Large/regular cigars, or small/medium cigars/cigarillos either “every day” or “some days.” Ever use of hookah and smokeless tobacco use was assessed within the survey, but not past 30-day use; thus these questions were not explored further for this particular analysis.

Control Variables

Standard demographic questions were included within the survey. Respondents reported age, gender, race and ethnicity, household income, education, and marital or relationship status. To control for the potentially influential effects of committed partnership, partnership was dichotomized into currently being married or living with a partner versus not currently being married or living with a partner.

Statistical Methods

Descriptive statistics were computed for all variables. Rao-Scott Chi-square tests were employed to examine differences between LGBT and non-LGBT exposure to and interaction with tobacco-related content. Logistic regressions were used to examine differences in current use of e-cigarettes and tobacco products (cigarettes and cigars) between LGBT and non-LGBT, adjusting for age, gender, race or ethnicity, income, education, and whether or not the participant is currently living with a partner. All analyses were performed using survey procedures in SAS version 9.4 for Windows; survey designs and weights were incorporated as appropriate. Unweighted frequencies, weighted percentages, and weighted odds ratios are reported.

Results

Population Description

Table 1 presents participant demographics. As a group, LGBT participants (N = 1092) were significantly more likely to be male, age 18 to 24, Latino/a, have income below $50000, and have more than a high school degree. Past 30-day use of tobacco was higher among LGBT than non-LGBT participants across tobacco use categories assessed, including: cigarettes, e-cigarettes, regular cigars, and little cigars or cigarillos.

Table 1.

Population Characteristics of Adult Lesbian, Gay Bisexual and/or Transgender (LGBT), and Non-LGBT Participants (N = 17522, Weighted %)

| Variables | Categories | LGBT (N = 1092) | Non-LGBT (N = 16430) | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Weighted % | N | Weighted % | |||

| Sexual Orientation | Straight | 117 | 11.8 | 16163 | 98 | NA |

| Gay | 334 | 35.4 | — | — | ||

| Lesbian | 185 | 14.5 | — | — | ||

| Bisexual | 437 | 38.3 | — | — | ||

| Other | 17 | 1.0 | 122 | 0.6 | ||

| Missing | 2 | 0.7 | 145 | 1.4 | ||

| Transgender Identity | Transgender | 168 | 15.5 | — | — | NA |

| Not Transgender | 919 | 83.9 | 16245 | 98.2 | ||

| Missing | 5 | 0.6 | 185 | 1.8 | ||

| Gender | Male | 539 | 57.8 | 7280 | 47.5 | p < .0001 |

| Female | 553 | 42.2 | 9150 | 52.5 | ||

| Age | 18 to 24 | 310 | 26.8 | 2385 | 18.7 | p < .0001 |

| 25 to 44 | 256 | 23.9 | 3275 | 25.1 | ||

| 45 to 64 | 341 | 38.1 | 5108 | 30.6 | ||

| 65+ | 185 | 11.3 | 5662 | 25.6 | ||

| Race or Ethnicity | White | 791 | 61.4 | 13140 | 68.5 | p = .0351 |

| Black | 94 | 12.2 | 1223 | 11.5 | ||

| Latino | 129 | 17.5 | 1117 | 13.2 | ||

| Other | 41 | 7.4 | 515 | 5.4 | ||

| 2+ | 37 | 1.5 | 435 | 1.4 | ||

| Partner | Married OR Living with Partner | 542 | 47.5 | 10146 | 62.9 | p < .0001 |

| Not Married OR Living with Partner | 550 | 52.5 | 6275 | 37.1 | ||

| Income | <$25000 | 337 | 24.5 | 3379 | 18.1 | p < .0001 |

| $25000–$49999 | 267 | 14.5 | 4472 | 24 | ||

| $50000–$84999 | 249 | 20.1 | 4499 | 28.5 | ||

| $85000+ | 239 | 23.9 | 4080 | 29.4 | ||

| Education | <High School | 60 | 7.9 | 637 | 6.7 | p = .0025 |

| High School | 193 | 27.1 | 3708 | 36.7 | ||

| Some College | 436 | 35.9 | 5906 | 30.9 | ||

| Bachelor’s Degree or Higher | 403 | 29.1 | 6179 | 25.7 | ||

| Location | California | 141 | 13.9 | 1545 | 11.1 | NS |

| All Other States | 951 | 86.1 | 14885 | 88.9 | ||

| Past 30-Day Tobacco Use | Cigarettes | 611 | 32.6 | 5996 | 20.1 | p < .0001 |

| E-Cigarettes | 213 | 10.8 | 1392 | 4.8 | p < .0001 | |

| Regular Cigars | 140 | 7.0 | 1342 | 5.3 | p = .0365 | |

| Small/Medium Cigars | 237 | 12.6 | 1658 | 6.2 | p < .0001 | |

Exposure to and Interaction with Tobacco Media

Table 2 presents ever and past 30-day exposure to, searching and sharing of tobacco-related content.

Table 2.

Unadjusted Ever and Past 30-Day Tobacco Media Exposure Among LGBT Participants (N = 17522, Weighted %’s)

| Entire survey populations (N = 17522) | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tobacco media exposure | Seen/ Heard | Searched For | Shared | ||||||||||||

| LGBT (N = 1092) | Non-LGBT (N = 16430) | LGBT (N = 1092) | Non-LGBT (N = 16430) | LGBT (N = 1092) | Non-LGBT (N = 16430) | ||||||||||

| N | Weighted % | N | Weighted % | N | Weighted % | N | Weighted % | N | Weighted % | N | Weighted % | ||||

| EVER | |||||||||||||||

| Discounts | 378 | 28.1 | 4315 | 24.5 | NS | 222 | 11.1 | 1603 | 5.7 | *** | 69 | 4.1 | 443 | 2.0 | ** |

| E-Cigarettes | 599 | 48.7 | 8236 | 47.7 | NS | 180 | 9.4 | 1269 | 4.7 | *** | 83 | 5.3 | 432 | 1.8 | *** |

| Anti-smoking ads | 631 | 54.1 | 9281 | 53.5 | NS | 63 | 3.1 | 309 | 1.3 | *** | 51 | 3.7 | 269 | 1.3 | *** |

| Past 30-Days | |||||||||||||||

| Discounts | 229 | 15.3 | 2131 | 11.1 | * | 160 | 7.3 | 1015 | 3.4 | *** | 51 | 2.8 | 269 | 1.2 | ** |

| E-Cigarettes | 451 | 34.7 | 5455 | 29.3 | * | 123 | 5.8 | 676 | 2.3 | *** | 60 | 3.4 | 303 | 1.2 | *** |

| Anti-smoking ads | 441 | 36.4 | 6231 | 34.1 | NS | 51 | 2.7 | 191 | 0.7 | *** | 31 | 1.6 | 171 | 0.7 | * |

| Current Smokers Only (Past 30-day, N = 6607) | |||||||||||||||

| Tobacco Media Exposure | Seen/ Heard | Searched For | Shared | ||||||||||||

| LGBT (N = 611) | Non-LGBT (N = 5996) | LGBT (N = 611) | Non-LGBT (N = 5996) | LGBT (N = 611) | Non-LGBT (N = 5996) | ||||||||||

| N | Weighted % | N | Weighted % | N | Weighted % | N | Weighted % | N | Weighted % | N | Weighted % | ||||

| Discounts | 194 | 31.8 | 1413 | 23.7 | *** | 154 | 25.2 | 947 | 15.8 | *** | 48 | 7.9 | 220 | 3.7 | *** |

| E-cigarettes | 312 | 51.1 | 2809 | 46.9 | * | 113 | 18.5 | 607 | 10.1 | *** | 54 | 8.8 | 246 | 4.1 | *** |

| Anti-smoking ads | 284 | 53.5 | 2790 | 46.6 | NS | 45 | 7.4 | 167 | 2.8 | *** | 29 | 4.7 | 136 | 2.3 | ** |

Significance: *p < .05, **p = .001, ***p < .0001

Lifetime Interaction with Tobacco Media

LGBT were significantly more likely to report having ever searched for or shared each of the three tobacco-related contents assessed (eg, coupons/discounts, e-cigarettes, and anti-tobacco messages) than were non-LGBT.

Past 30-Day Interaction with Tobacco Media

LGBT participants were significantly more likely to have been exposed to e-cigarette content (34.7%) in the past 30 days, compared to non-LGBT (29.3%, p = .0188). Similarly, LGBT participants were significantly more likely (15.5%) than non-LGBT participants (11.1%) to report having been exposed to coupons or discounts for buying tobacco products in the last 30 days (p = .0042).

Conversely, LGBT were not more likely than non-LGBT to report being exposed to anti-tobacco (tobacco control) content in the past 30 days. Despite this, LGBT were significantly more likely to report having searched for anti-tobacco messages in the past 30 days (2.7%) compared to non-LGBT (0.7%, p < .0001). LGBT were also more likely than non-LGBT to have searched for (Discounts: 7.3%, E-cigarettes: 5.8%, Anti-Smoking Ads: 2.7%) or shared (Discounts: 2.8%, E-Cigarettes: 3.4%, Anti-Smoking Ads:1.6%) each of the tobacco-related contents assessed in the past 30 days than were non-LGBT (Searched: Discounts: 3.4%, E-cigarettes: 2.3%, Anti-Smoking Ads:0.7%; Shared: Discounts: 1.2%, E-cigarettes: 1.2%, Anti-Smoking Ads: 0.7%).

LGBT and Non-LGBT Smokers’ Interaction with Tobacco Media

Among smokers only, results were similar to the general population, but more pronounced. LGBT who were smokers were significantly more likely to report having seen or heard tobacco couponing or discounts (31.8 vs. 23.7, p < .0001) and e-cigarette advertising (51.1 vs. 46.9, p < .05) in the past 30-days compared to non-LGBT smokers. Conversely, LGBT smokers were not more likely to report having seen or heard anti-tobacco advertisements in the past 30 days. LGBT who were smokers reported significantly more searching for and sharing of all three of the tobacco media exposure variables, compared to their non-LGBT smoker counterparts.

Channels of Tobacco Media Exposure in Past 30-Days

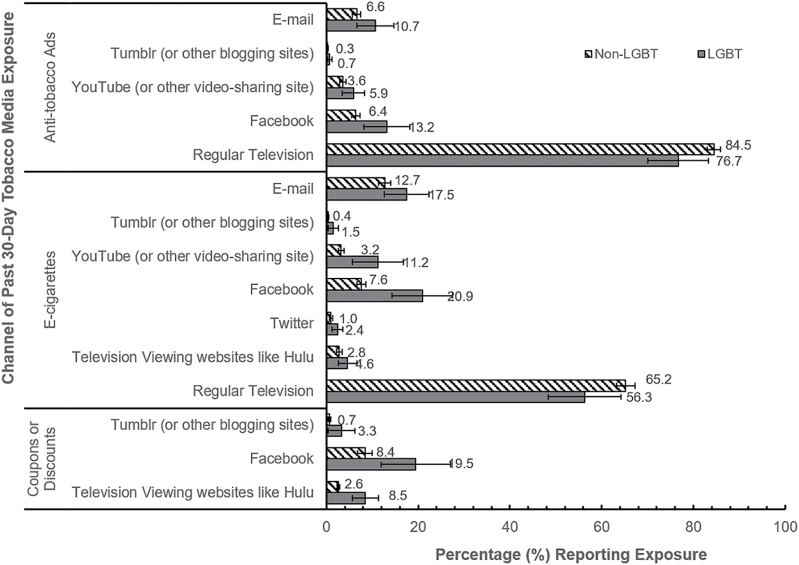

Data describing significant differences in channels of exposure to tobacco-related content (eg, coupons or discounts, e-cigarettes, or anti-tobacco messages) of those exposed to tobacco-related content in the past 30-days are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Channel of past 30-day media exposure by LGBT and non-LGBT.

Coupons and Discounts

LGBT were significantly more likely to report being exposed to tobacco-related coupons or discounts on social media such as Facebook (19.5%, p = .0003) and Tumblr (3.3%, p = .0004) than were non-LGBT (8.4% vs. 0.7%, respectively). LGBT (8.5%) were over three times as likely to report being exposed to tobacco couponing messages on video streaming websites such as Hulu than were non-LGBT (2.6%, p < .0001).

E-cigarettes

LGBT participants were significantly less likely to report exposure to e-cigarettes on regular television (56.3%) than did non-LGBT participants (65.2%, p < .05). However, LGBT were significantly more likely than non-LGBT participants to be exposed to e-cigarette content on a variety of internet-based and social media (p < .05), including Facebook (20.9% vs. 7.6%, respectively), YouTube (11.2% vs. 3.2%, respectively), video streaming websites (4.6% vs. 2.8%, respectively), Twitter (2.4% vs. 1.0%, respectively), and Tumblr (1.5% vs. 0.4%, respectively).

Anti-Tobacco Messages

LGBT (76.7%) were significantly less likely than non-LGBT (84.5%) to report exposure to anti-tobacco messages on regular television (p = .0088). However, LGBT continued to be more likely to report exposure to anti-tobacco messages on internet-based and social media websites. LGBT were approximately twice as likely as non-LGBT to be exposed to anti-tobacco messages on Facebook (13.2% vs. 6.4%, p = .0006), YouTube (5.9% vs. 3.6%, p < .05), and Tumblr (0.7% vs. 0.3%, p < .05)). LGBT were also more likely to be exposed to anti-tobacco messages via e-mail (10.7%) than were non-LGBT (6.6%, p < .05).

Channels of Past 30-day Searching and Sharing of Tobacco Media Content

Tobacco-related Coupons or Discounts

LGBT were significantly more likely to use social media websites to search for tobacco coupons or discounts than were non-LGBT. Specifically, LGBT used Twitter (12.1% vs. 4.8%, p = .0007) and Tumblr (10.3% vs. 2.7%, p < .0001) nearly three times as often as non-LGBT to search for tobacco coupons or discounts. LGBT reported using Facebook (28.9% vs. 17.1%, p = .0084) and YouTube (15.9% vs. 8.2%, p = .0185) nearly twice as often as non-LGBT for tobacco-related couponing or discounts.

E-cigarettes

LGBT reported using Twitter twice as often as non-LGBT to search for information on e-cigarettes (12.7% vs. 5.6%, p = .0174) and used Tumblr nearly three times as often to share information about e-cigarettes (20.2% vs. 6.8%, p = .0320).

Anti-tobacco Messages

Although LGBT participants were somewhat less likely to use YouTube to search for anti-tobacco messages (23.7%) than their non-LGBT counterparts (25.5%, p = .0463), they were over twice as likely to report having shared anti-tobacco messages on Twitter (29.5% vs. 12.1%, p = 0.0025) and Tumblr (0.7% vs. 0.3%, p = 0.0104).

LGBT Status, Tobacco Media Exposure, and Past 30-Day Tobacco Use Behaviors—Adjusted Logistic Regression

Unadjusted and adjusted logistic regressions were similar across analyses, thus unadjusted regressions are not presented. Across each of the fully adjusted regression analyses (Table 3), LGBT had significantly higher odds of past 30-day tobacco use compared to non-LGBT (p = .0001 or p < .0001), even after controlling for past 30-day exposure to each of the various tobacco media assessed (coupons/discounts, e-cigarettes and anti-tobacco ads), as well as age, ethnicity, income, and living with a partner. Controlling for the aforementioned variables, past 30-day anti-tobacco ad exposure was also independently significantly associated with higher odds of past 30-day tobacco use across products in each of the nine models (p < .0001).

Table 3.

Adjusted Logistic Regression Examining the Association Between LGBT Status and Past 30-Day Exposure to Tobacco-related Media With Current Tobacco Use Among Adults*

| Variables of interest | Past 30-day use | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Past 30-Day Coupon Exposure | Cigarette (N = 17496) |

E-Cigarettes (N = 17467) |

Cigar (N = 17388) |

|||

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| LGBT (vs. Non-LGBT) | 1.76*** | (1.44–2.16) | 2.12*** | (1.66–2.71) | 1.60*** | (1.26–2.02) |

| Past 30-day Coupon Exposure (vs. No Exposure) | 3.27*** | (2.81–3.80) | 2.85*** | (2.34–3.48) | 3.21*** | (2.70–3.82) |

| Past 30-Day E-Cigarette Exposure | Cigarette (N = 17493) |

E-Cigarettes (N = 17464) |

Cigar (N = 17385) |

|||

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| LGBT (vs. Non-LGBT) | 1.77*** | (1.44–2.17) | 2.11*** | (1.64–2.71) | 1.60** | (1.26–2.04) |

| Past 30-day E-cigarette Ad Exposure (vs. No Exposure) | 2.52*** | (2.27–2.81) | 2.78*** | (2.35–3.30) | 2.29*** | (1.99–2.64) |

| Past 30-Day Anti-Tobacco Exposure | Cigarette (N = 17494) |

E-Cigarettes (N = 17465) |

Cigar (N = 17287) |

|||

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| LGBT (vs. Non-LGBT) | 1.79*** | (1.46–2.19) | 2.17*** | (1.69–2.77) | 1.62*** | (1.27–2.06) |

| Past 30-day Anti-Tobacco Ad Exposure (vs. No Exposure) | 1.92*** | (1.72–2.13) | 1.91*** | (1.62–2.26) | 2.10*** | (1.82–2.42) |

*All analyses adjust for: age, gender, race or ethnicity, education, income, and whether or not living with a partner.

**p = .001, ***p < .0001

Discussion

This is the first scientific study to report significant differences between LGBT and non-LGBT in exposure to pro- and anti-tobacco–related messages. This study demonstrates that LGBT may not only be exposed to pro-tobacco–related marketing at higher rates than their non-LGBT peers, but also appear to be actively searching for and sharing this information on social media at higher rates. This relationship appears to be stronger among LGBT smokers. Taken together, this evidence suggests that the impact of such differences in media exposure is linked to the disparate tobacco use behavior across products assessed between LGBT and non-LGBT; specifically, current use of cigarettes, e-cigarettes, and cigars. Additionally, it appears that higher tobacco use observed in LGBT populations is complex and higher media exposure by itself is not sufficient to account for the disparities in tobacco use between LGBT and non-LGBT.

This study adds to the literature on the tobacco industry’s complex practice of marketing to and targeting LGBT communities8–12 by providing evidence that LGBT appear to be more frequently exposed to pro-tobacco content via television and on-line sources, while at the same time being less frequently reached by anti-tobacco messages through sources such as broadcast media, print ads, and point-of-sale promotions, in comparison to non-LGBT. The literature is sparse on LGBT exposure to anti-tobacco messages; what is available has largely focused on cessation rather than prevention or general anti-tobacco messaging.15,16 Research assessing exposure to cessation advertising found similar exposure between LGBT and non-LGBT participants, but did not assess for general exposure to prevention or general anti-tobacco messages.16

The current study provides evidence that LGBT are more frequently exposed to tobacco-related content on new and social media and less frequently exposed via traditional methods such as television. The source of exposure varied between LGBT and non-LGBT, with LGBT more frequently reporting exposure to both pro- and anti-tobacco content on social media sources (eg, Facebook and Twitter). Conversely, LGBT less frequently reported exposure to tobacco-related content on television compared to non-LGBT. Additionally, this study supports the idea that both LGBT and non-LGBT smokers appear to recall anti-tobacco messages at higher rates than LGBT and non-LGBT populations as a whole; this may or may not indicate actual exposure to anti-tobacco ads.

In this study, LGBT more frequently reported actively interacting with (eg, searching or sharing) tobacco-related content across both pro- and anti-tobacco categories than did non-LGBT. The finding that LGBT not only are exposed to, but also interact with pro-tobacco content at significantly higher rates than non-LGBT is concerning. Whether this result directly affects higher tobacco product consumption is unknown and is certainly an area for further research. An opportunity to better target anti-tobacco messages may be evident in the finding that LGBT actively use new and social media to find ways to quit. No other studies have reported on this phenomenon and our study provides evidence that a higher proportion of LGBT may be actively searching for cessation information.

In line with research focused on young and vulnerable populations, exposure to tobacco messages appears to be directly related to disparities in LGBT tobacco use.4–7 The current study describes higher odds of tobacco use across products for LGBT compared to non-LGBT, even after controlling for past 30-day exposure to tobacco media, both of which were significant.

This research has important implications for tobacco control and prevention policy and outreach. Most of the available scientific literature on tobacco industry marketing to LGBT has focused on traditional media.9,18 There has been debate in both scientific and marketing fields as to whether or not LGBT are early adopters and more frequent users of novel technologies and social media compared to the general population. It is important that, as technology advances, so does scientific inquiry into these topics such as exploring the role new and social media play in tobacco-related health disparities. Although some research indicates LGBT do use new and social media at higher rates,27 little has been done to assess the relationship between LGBT use of traditional and new media and the frequency and availability of LGBT-targeted pro- and anti-tobacco messages across these platforms. Recently, LGBT-targeted tobacco prevention and cessation campaigns by Legacy, CDC Tips from a Former Smoker, FDA and others have begun to address this important gap.28,29 Future research should specifically explore the relationships across media platforms, as well as assess the success of these targeted campaigns in order to assess how tobacco control can best reach and appeal to LGBT populations.

As LGBT participants reported higher rates of exposure on new and social media compared to non-LGBT, reducing tobacco-related disparities among LGBT may require increasing the number of LGBT-targeted anti-tobacco campaigns to complement other anti-tobacco efforts. Based on the current research, anti-tobacco efforts should consider creating more social media-friendly messaging in order to better reach LGBT populations. Our data suggest that LGBT self-report higher rates of tobacco use and higher rates of social media use, both of which are associated with higher self-reported exposure to tobacco-related messaging on social media. Based on a plethora of evidence from tobacco industry documents,8,11,12 it is plausible that the tobacco industry specifically targets LGBT on social media. However, more research is needed to determine if and how the tobacco industry is specifically targeting LGBT on social media. To better understand how to reach and appeal to LGBT populations, future research should explore whether differences observed in exposure to tobacco-related content among LGBT and non-LGBT are due to differences in use of these media, to differences in the amount of LGBT-targeted or appealing ads available on these media, or perhaps due to a combination of the two.

This study has certain limitations. First, while the LGBT sample size was sufficient to examine tobacco-related media and product use variables, it was insufficient to explore variation across LGBT subgroups. Our previous work demonstrated that LGBT are heterogeneous, exhibit differences in tobacco use across subpopulations and by gender, and likely study included LGBT as a single aggregate population compared with non-LGBT as a single aggregate population, future research including a second wave of data collection, will include stratified analysis by sexual orientation experience important differences in risk factors by subgroup1; particularly relevant as other research has indicated differences in LGBT subpopulation exposure to tobacco industry marketing.30 Future research should augment LGBT sample size, allowing for subpopulation exploration. Second, this study did not assess print media or in-store promotions, which have been associated with tobacco use particularly in young and diverse populations.31–34 Third, this study is cross-sectional; longitudinal research is needed to confirm causal relationships. An additional limitation of the current study is that while it is a national sample, 25% of the sample (off-panel) relies on convenience sampling. We address this concern by applying post-stratification weighting procedures (Knowledge Panel Calibration) to calibrate and combine the two samples so that the combined sample is comparable to the probability sample as a whole. Furthermore, participants who agree to participate in research may be different in some unforeseen way in comparison to participants who do not choose to participate in research; this bias was minimized with base weighting as well as the post-stratification weighting to account for nonresponse. Taken together, the findings should be interpreted keeping the complex sampling structure in mind. However, we are confident that biases that may arise from a panel survey have been minimized as best as possible using appropriate statistical techniques, and previous research has been published using these sampling technique.1,21 Finally, a variety of analyses were conducted to explore the vast number of predictive variables and outcomes of interest, increasing the possibility of finding a significant difference by chance. The relatively consistent significance across analyses offers confidence that the observed results were not based on false positives.

Conclusion

LGBT reported more frequent exposure to and interaction with pro-tobacco content and some evidence for less exposure to anti-tobacco content than did non-LGBT, and these relations appear directly related to tobacco-related LGBT disparities. This was particularly apparent among LGBT who were smokers. In contrast, exposure to anti-tobacco content appears to have an ameliorative effect on tobacco-use disparities among LGBT. Compared to non-LGBT, LGBT reported higher levels of exposure to tobacco-related content on new and social media, and lower levels of exposure on television, making the internet an ideal medium for future tobacco control and prevention efforts among this hard-to-reach population.

Funding

This research was supported by funds from the National Cancer Institute (5 U01 CA154254) and the State of California Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program (TRDRP) Research Grants Program Office of the University of California, grant number 23FT-0115.

Declaration of Interests

The authors have no competing interests to report.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank the entire team at the Health Media Collaboratory (HMC) as well as participants of the TCME study, without whom this manuscript would not have been possible.

References

- 1. Emory K, Kim Y, Buchting F, Vera L, Huang J, Emery SL. Intragroup variance in lesbian, gay, and bisexual tobacco use behaviors: Evidence that subgroups matter, notably bisexual women. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18(6):1494–1501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lee JGL, Griffin GK, Melvin CL. Tobacco use among sexual minorities in the USA, 1987 to May 2007: A systematic review. Tob Control. 2009;18(4):275–282. doi:10.1136/tc.2008.028241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lee JG, Blosnich JR, Melvin CL. Up in smoke: Vanishing evidence of tobacco disparities in the Institute of Medicine’s report on sexual and gender minority health. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(11):2041–2043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Emory KT, Messer K, Vera L, et al. . Receptivity to cigarette and tobacco control messages and adolescent smoking initiation. Tob Control. 2015;24(3):281–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lovato C, Watts A, Stead LF. Impact of tobacco advertising and promotion on increasing adolescent smoking behaviours. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(10):CD003439 http://cochranelibrary-wiley.com/ doi/10.1002/14651858.CD003439.pub2/abstract [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gilpin EA, White MM, Messer K, Pierce JP. Receptivity to tobacco advertising and promotions among young adolescents as a predictor of established smoking in young adulthood. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(8):1489–1495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Smith DM, Bansal-Travers M, O’Connor RJ, Goniewicz ML, Hyland A. Associations between perceptions of e-cigarette advertising and interest in product trial amongst US adult smokers and non-smokers: Results from an internet-based pilot survey. Tob Induc Dis. 2015;13(1):14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Stevens P, Carlson LM, Hinman JM. An analysis of tobacco industry marketing to lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) populations: Strategies for mainstream tobacco control and prevention. Health Promot Pract. 2004;5(3 Suppl):129S–134S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Washington HA. Burning Love: Big tobacco takes aim at LGBT youths. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(7):1086–1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Smith EA, Malone RE. The outing of Philip Morris: Advertising tobacco to gay men. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(6):988–993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Reynolds RJ. Project SCUM December 1995. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/mum76d00.

- 12. Smith EA, Thomson K, Offen N, Malone RE. “If you know you exist, it’s just marketing poison”: Meanings of tobacco industry targeting in the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender community. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(6):996–1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sell RL, Dunn PM. Inclusion of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people in tobacco use-related surveillance and epidemiological research. J LGBT Health Res. 2008;4(1):27–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Buchting FO, Furmanski WL, Lee JGL, et al. . Mpowered: Best and Promising Practices for LGBT Tobacco Prevention and Control Released. Boston, MA: Network for LGBT Health Equity; 2012. http://lgbthealthequity.wordpress.com/2012/08/21/mpowered-best-and-promising-practices-for-lgbt-tobacco-prevention-and-control-released/. Accessed September 13, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lee JG, Matthews AK, McCullen CA, Melvin CL. Promotion of tobacco use cessation for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people: A systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(6):823–831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fallin A, Lee YO, Bennett K, Goodin A. Smoking cessation awareness and utilization among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender adults: An analysis of the 2009–2010 national adult tobacco survey. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18(4): 496–500. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntv103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Matthews AK, Balsam K, Hotton A, Kuhns L, Li C-C, Bowen DJ. Awareness of media-based antitobacco messages among a community sample of LGBT individuals. Health Promot Pract. 2014 Nov;15(6): 857–866. Epub 6 May 2014. doi:10.1177/1524839914533343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lee JGL, Agnew-Brune CB, Clapp JA, Blosnich JR. Out smoking on the big screen: Tobacco use in LGBT movies, 2000–2011. Tob Control. 2014;23:e156–e158. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013–051288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. The GfK Group. Knowledge Panel Design Summary. Palo Alto, CA: The GfK Group; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 20. KnowledgePanel Calibration. http://www.gfk.com/products-a-z/us/knowledgepanel-united-states/knowledgepanel-calibration/. Published February 15, 2017. Accessed February 22, 2018.

- 21. Buchting FO, Emory KT, Scout, et al. Transgender use of cigarettes, cigars, and e-cigarettes in a national study. Am J Prev Med. 2017;53(1):e1–e7. Epub 13 Jan 2017. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2016.11.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Huang J, Kim Y, Vera L, Emery SL. Electronic cigarettes among priority populations: Role of smoking cessation and tobacco control policies. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50(2):199–209. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2015.06.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. SMART. Best Practices for Asking Questions about Sexual Orientation on Surveys. Los: The Williams Institute on Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Law and Public Policy at UCLA School of Law; 2009:58. [Google Scholar]

- 24. The GenIUSS Group. Best Practices for Asking Questions to Identify Transgendder and Other Gender Minority Respondents on Population-Based Surveys. Los Angeles, CA: The Williams Institute; 2004. http://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/geniuss-report-sep-2014.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Current Population Survey, May 2006: Tobacco Use Supplement (TUS), 2006–2007 Wave Census Bureau; 2006. http://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/RCMD/studies/24781. Accessed August 18, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 26. ITC Project. ITC project http://www.itcproject.org/. Published 2013. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 27. Seidenberg AB, Jo CL, Ribisl KM, et al. . A national study of social media, television, radio, and internet usage of adults by sexual orientation and smoking status: Implications for campaign design. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(4):450. doi:10.3390/ijerph14040450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. This Free Life Campaign. Washington DC: U.S. Food and Drug Administration; 2016. https://www.fda.gov/TobaccoProducts/PublicHealthEducation/PublicEducationCampaigns/ThisFreeLifeCampaign/default.htm. Accessed June 20, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) Tips From Former Smokers. http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/campaign/tips/groups/lgbt.html. Published 2015. Accessed May 17, 2016.

- 30. Dilley JA, Spigner C, Boysun MJ, Dent CW, Pizacani BA. Does tobacco industry marketing excessively impact lesbian, gay and bisexual communities?Tob Control. 2008;17(6):385–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wakefield MA, Ruel EE, Chaloupka FJ, Slater SJ, Kaufman NJ. Association of point-of-purchase tobacco advertising and promotions with choice of usual brand among teenage smokers. J Health Commun. 2002;7(2):113–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Robertson L, McGee R, Marsh L, Hoek J. A systematic review on the impact of point-of-sale tobacco promotion on smoking. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(1):2-17. Epub 30 Aug 2014. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntu168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Paynter J, Edwards R. The impact of tobacco promotion at the point of sale: A systematic review. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11(1):25–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Smith EA, Offen N, Malone RE. What makes an ad a cigarette ad? Commercial tobacco imagery in the lesbian, gay, and bisexual press. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59(12):1086–1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]