SUMMARY

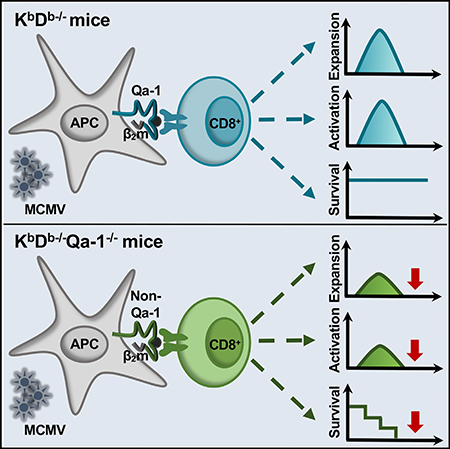

The role of non-classical T cells during viral infection remains poorly understood. Using the well-established murine model of CMV infection (MCMV) and mice deficient in MHC class Ia molecules, we found that non-classical CD8+ T cells robustly expand after MCMV challenge, become highly activated effectors, and are capable of forming durable memory. Interestingly, although these cells are restricted by MHC class Ib molecules, they respond similarly to conventional T cells. Remarkably, when acting as the sole component of the adaptive immune response, non-classical CD8+ T cells are sufficient to protect against MCMV-induced lethality. We also demonstrate that the MHC class Ib molecule Qa-1 (encoded by H2-T23) restricts a large, and critical, portion of this population. These findings reveal a potential adaptation of the host immune response to compensate for viral evasion of classical T cell immunity.

In Brief

Anderson et al. describe a heterogenous population of non-classical CD8+ T cells responding to MCMV. Importantly, this population can protect mice from MCMV-induced lethality in the absence of other adaptive immune cells. Among the MHC class Ib-restricted CD8+ T cells responding, Qa-1-specific cells are required for protection.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) is a ubiquitous herpesvirus that results in approximately half of the population in the United States becoming seropositive (Bate et al., 2010). In healthy individuals, cytomegalovirus (CMV) is easily resolved; however, it remains latent and can periodically reactivate, asymptomatically. CMV is superbly adept at evading components of the host’s innate and adaptive immune systems; thus, maintaining suppression requires a multilayered immune response (Polić et al., 1998). This results in an interplay between viral escape mechanisms and host immune control (Jackson et al., 2011). However, primary and reactivated CMV infections are both potential sources of morbidity and mortality for immunocompromised patients, in addition to being a serious congenital infection (Grosse et al., 2008).

Each member of the CMV family displays species-specific tropism; therefore, animal models are required to better understand the multifaceted immune response elicited during infection. Murine CMV (MCMV) is a well-established model with similarities in genome, latency, and reactivation to HCMV (Smith et al., 2008). There are also parallels in the immune response. For example, an intact CD8+ T cell response correlates favorably with outcome in both humans and mice (Quinn et al., 2015; Reddehase et al., 1987; Quinnan et al., 1982; Walter et al., 1995). In fact, a large fraction of the T cell compartment is devoted to CMV. In seropositive individuals, approximately 10% of circulating CD4+ and CD8+ T cells are CMV specific (Sylwester et al., 2005).

Compared to the well-characterized roles of classical CD8+ T cells during CMV infection, the immunologic contributions of non-classical CD8+ T cells remain poorly understood. Non-classical CD8+ T cells are restricted by major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class Ib molecules (e.g., human leukocyte antigen [HLA]-E, -F, and -G in humans), rather than MHC class Ia (i.e., HLA-A, -B, and -C in humans). These are structurally similar to MHC class Ia but are generally non-polymorphic and have lower cell surface expression (Stroynowski and Lindahl, 1994). Some MHC class Ib molecules can also present unique types of antigens to T cells, including vitamin B metabolites, lipids, and N-formylated peptides (Godfrey et al., 2015).

Non-classical CD8+ T cells participate in the host defense against a number of bacterial and viral pathogens (Anderson and Brossay, 2016). Evidence also suggests that HLA-E-restricted CD8+ T cells are present following HCMV infection (Mazzarino et al., 2005; Pietra et al., 2003); however, their role during the immune response is unclear. In mice, Qa-1 (encoded by H2-T23) is the functional homolog of HLA-E. HLA-E and Qa-1 are normally loaded with peptides derived from the leader sequences of classical MHC molecules, referred to as Qa-1 determinant modifier (Qdm) (Aldrich et al., 1994; Braud et al., 1997; Lee et al., 1998a). HLA-E- (Braud et al., 1998; Lee et al., 1998b) and Qa-1-bound (Vance et al., 1998; Vance et al., 1999) Qdm interact with members of the CD94-NKG2 family of receptors, in addition to certain T cell receptors. Natural killer (NK) cells and CD8+ T cells are both repressed when HLA-E and Qa-1-Qdm engages the inhibitory receptor CD94-NKG2A (Vance et al., 2002; Moser et al., 2002). Interestingly, in an attempt to avoid the NK cell response by CD94-NKG2A engagement (Wang et al., 2002), certain HCMV strains encode their own ligand for HLA-E within the signal sequence of its glycoprotein UL40 (gpUL40) (Tomasec et al., 2000; Ulbrecht et al., 2000). These peptides can be identical, or nearly identical, to Qdm depending on the HCMV strain. As a result, allogenic gpUL40-reactive HLA-E-restricted CD8+ T cells may occur following infection with certain strains and HLA haplotypes (Jouand et al., 2018).

CMV uses a variety of mechanisms to avoid the classical T cell response, including downregulation of conventional MHC class I and II molecules (Halenius et al., 2015; Yunis et al., 2018). Given the virus’s preponderance for immune evasion, we sought to delineate the contribution of MHC class Ib-restricted CD8+ T cells. We demonstrate that non-classical CD8+ T cells are phenotypically similar to conventional CD8+ T cells, rather than innate-like MHC-class-Ib-restricted T cells, and capable of developing memory; this population was also sufficient to protect against MCMV-induced lethality. Using CRISPR-Cas9-generated KbDb−/−Qa-1−/− mice, we determined that this population contained Qa-1-restricted T cells, which were critical for protection. In contrast to previously identified HLA-E-restricted cells, this population does not depend on Qdm or UL40-derived peptides. Together, these studies add another contributing immunologic layer against CMV. The anti-viral properties of non-classical T cells make them attractive targets not only to examine during infection, but also for vaccine development as well.

RESULTS

Non-classical CD8+ T Cells Participate during Acute MCMV Infection in KbDb−/− Mice

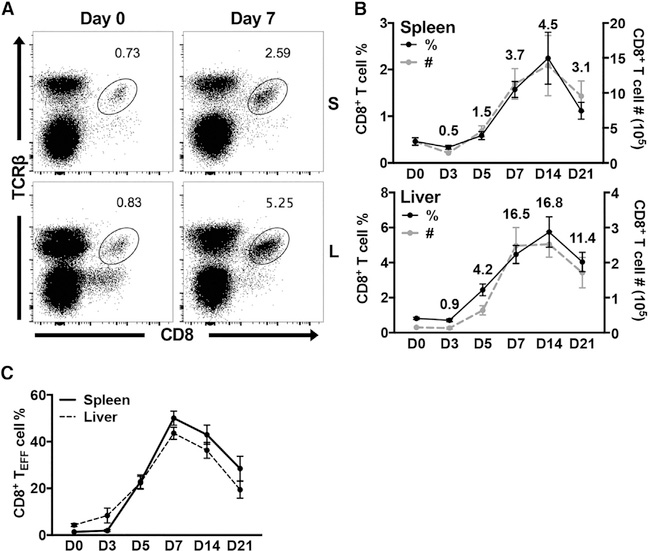

To study the non-classical CD8+ T cell response in the absence of classical CD8+ T cells, we took advantage of KbDb−/− mice (Pérarnau et al., 1999). H-2Kb and H-2Db encode MHC class Ia molecules in mice on the C57BL/6 background; thus, any residual CD8+ T cells present in KbDb−/− animals are selected by MHC class Ib molecules. As previously reported, we found greatly diminished populations of CD8+ T cells in naive KbDb−/− animals (Figure 1A) (Vugmeyster et al., 1998; Pérarnau et al., 1999). However, both the frequency and absolute number of these cells robustly increased in the spleen, liver (Figures 1A and S1A), and blood (data not shown) on day 7 post-MCMV infection. This response peaked by day 14 and equated to an approximate 5-fold and 17-fold expansion in the spleen and liver, respectively (Figure 1B). MCMV-expanded non-classical CD8+ T cells subsequently began to contract by day 21 (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Non-classical CD8+ T Cells Participate during Acute MCMV Infection in KbDb−/− Mice.

(A) Representative staining of CD8+ T cells in the spleen and liver of KbDb−/− mice on day 0 and day 7 post-MCMV infection.

(B) Frequency (black) and number (gray) of CD8+ T cells in the spleen and liver of KbDb−/− mice on indicated days post-MCMV infection (n = 9). Numbers indicate fold change of cell number compared to day zero.

(C) Frequency of CD8+ TEFF cells (KLRG1+CD127−) in the spleen (—) and liver (- -) of KbDb−/− mice on indicated days post-MCMV infection (n = 9). Data are pooled from three independent experiments and represent mean ± SEM.

See also Figures S1 and S2.

MCMV-Expanded Non-classical CD8+ T Cells Are Distinct from Innate-like T Cells

Many non-classical T cells have a unique innate-like phenotype and do not require clonal expansion following stimulation; this gives them access to more rapid effector functions (Godfrey et al., 2015). Based on the kinetics that we observed for MCMV-expanded non-classical CD8+ T cells, we wondered whether they were more similar to conventional T cells or maintained innate-like characteristics. The transcription factor promyelocytic leukemia zinc finger (PLZF) is thought to act as a major regulator for innate-like T cells. For example, γδ T cells (Kreslavsky et al., 2009), mucosal-associated invariant T (MAIT) cells (Rahimpour et al., 2015), and NKT cells (Kovalovsky et al., 2008) all express PLZF. Although PLZF-expressing CD8+ T cells were present in naive KbDb−/− mice, they were PLZFneg and T-bethi on day 7 post-MCMV infection (Figure S1B). Non-classical T cells can also express NK1.1, such as NKT cells, or have a CD8αα homodimer instead of a CD8αβ heterodimer as their co-receptor. The liver in particular was enriched for CD8αα+ and NK1.1+ T cells in naive KbDb−/− animals; however, neither of these populations expanded upon infection (Figures S1C and S1D). Together, these data indicate that non-classical CD8+ T cells are phenotypically more similar to conventional T cells than innate-like T cells, following MCMV infection.

Non-classical CD8+ T Cells Acquire an Effector Phenotype following Acute MCMV Infection

Conventional CD8+ T cells downregulate CD62L and upregulate CD44 expression following activation during acute infection, becoming cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) (CD44hiCD62Llo). In KbDb−/− mice on day 7 post-MCMV infection, there was also an increase in CTLs and a reciprocal decrease in naive (CD44IoCD62Lhi) CD8+ T cells, compared to uninfected controls (Figures S2A and S2C). However, many non-classical CD8+ T cells from naive KbDb−/− animals were already CD44hiCD62Llo, potentially misconstruing interpretation (Figures S2A and S2C) (Kurepa et al., 2003). To better evaluate the activation status of MCMV-expanded non-classical CD8+ T cells, we monitored KLRG1 expression, which is upregulated on short-lived effector CD8+ T cells (TEFF, KLRG1+CD127). Non-classical CD8+ T cells do not express KLRG1 in naive animals; however, upregulation of KLRG1 began by day 5 post-infection and peaked on day 7 (Figures 1C, S2B, and S2D). They also upregulated CD94-NKG2A (Figure S2E), commonly acquired in response to infection (McMahon et al., 2002), and became CX3CR1high (Figures S2F and S2G), which associates with terminal effector cell differentiation following MCMV challenge (Gerlach et al., 2016). In addition, KbDb−/− mice did not have increased viral levels during acute infection in the spleen or liver compared to wild-type animals (Figures S2H and S2I). Following clearance in other organs, MCMV enters the salivary gland (SMG), a privileged site of infection, where there is a peak in viral replication around 14 to 21 days. In contrast to wild-type controls, KbDb−/− animals appear to have a shift in the kinetics of MCMV replication within the SMG (Figure S2J). Altogether, these data suggest KbDb−/− mice control MCMV in the absence of conventional CD8+ T cells.

The Expansion and Activation of Non-classical CD8+ T Cells Is MCMV Dependent

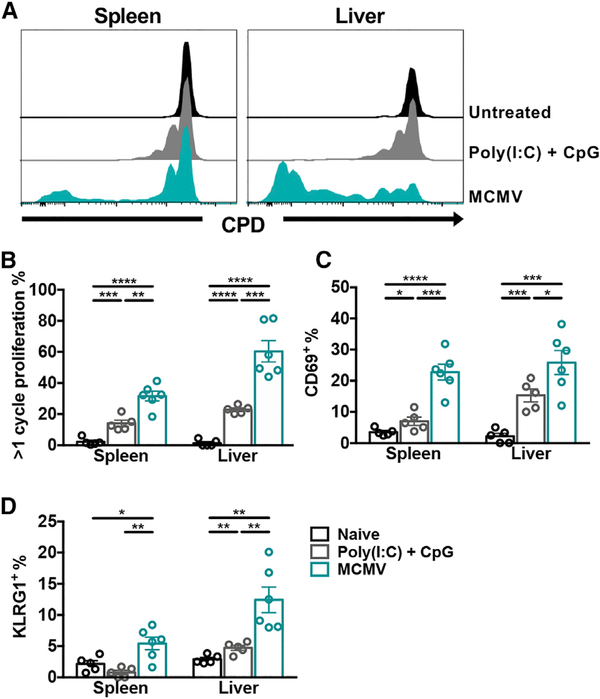

Certain non-classical T cells can uniquely respond to noncognate activation through environmental cytokines, independently of T cell receptor (TCR) engagement. For example, invariant NKT (iNKT) cell activation during MCMV infection is predominantly a result of infection-induced inflammatory cytokines (Tyznik et al., 2008; Wesley et al., 2008; Holzapfel et al., 2014). This led us to ask whether the non-classical CD8+ T cell response was cytokine dependent or MCMV dependent. CD8+ T cells from KbDb−/− mice were adoptively transferred into KbDb−/−.SJL recipients that were then left untreated, treated with CPG oligodeoxynucleotide (ODN) and polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid (Poly(I:C)), or infected with MCMV. CPG ODN and Poly(I:C) are TLR9 and TLR3 agonists, respectively, and were used to simulate MCMV infection, which signals through TLR3 and TLR9 (Tabeta et al., 2004). Donor cells in the spleen and liver of naive recipients did not undergo detectable homeostatic proliferation on day 4, and CPG ODN and Poly(I:C) treatment resulted in minimal proliferation (Figures 2A and 2B). In contrast, a significant number of donor cells from MCMV-infected mice proliferated, particularly in the liver (p < 0.001) compared to treated mice (Figures 2A and 2B). In agreement with these findings, only donor cells from virally infected recipients expressed both CD69 and KLRG1 in the spleen and liver (Figures 2C and 2D). Altogether, these data suggest that environmental inflammation alone is insufficient for non-classical CD8+ T cells to proliferate and become TEFF cells following MCMV infection.

Figure 2. The Expansion and Activation of Non-classical CD8+ T Cells is MCMV Dependent.

(A) Representative cell proliferation dye (CPD) labeling of donor non-classical CD8+ T cells (CD45.2+) in the spleen and liver of KbDb−/−.SJL (CD45.1+) recipients on day 4 post-transfer. Recipients were left naive (black), treated with Poly(I:C) + CpG (gray), or infected with MCMV (blue). Histograms are gated on total donor non-classical CD8+ T cells.

(B–D) Frequencies of donor CD8+ T cells that (B) have undergone more than one cycle of proliferation, (C) are CD69+, or (D) are KLRG1+ (n = 5–6).

Data are pooled from two independent experiments and represent mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001.

The Non-classical CD8+T Cell Response Correlates with a Prolonged Inflammatory Phenotype following MCMV Infection

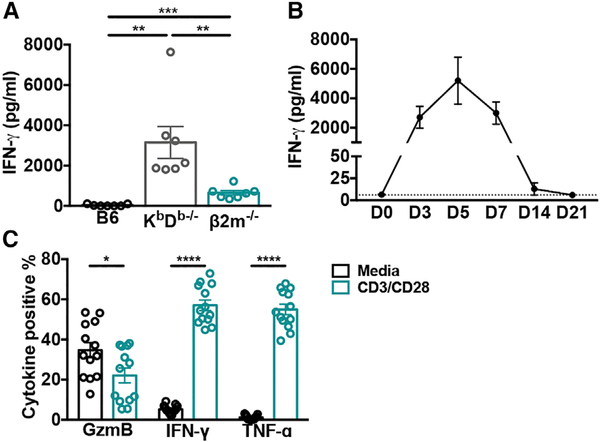

Having demonstrated that the non-classical CD8+ T cell response is dependent on viral infection, we sought to determine whether they contribute to the inflammatory cytokine profile observed during acute MCMV. Interestingly, although there was only residual interferon gamma (IFN-γ) detected in the serum of wild-type animals on day 7 post-infection, it remained elevated in KbDb−/− mice (Figure 3A). This phenotype is striking when compared to β2m−/− animals at the same time-point, which lack both MHC class Ia- and Ib-restricted CD8+ T cells, and also had significantly less IFN-γ (p < 0.01) (Figure 3A). The high level of serum IFN-γ in KbDb−/− mice returned to normal levels by day 14 post-infection (Figure 3B). Although these differences could be due to kinetic differences or a consequence of abnormalities in β2m−/− animals, non-classical CD8+ T cells were also capable of producing large amounts of cytokines on day 7 post-infection following restimulation ex vivo (Figure 3C). Together, these data indicate that non-classical CD8+ T cells may contribute to a prolonged inflammatory milieu.

Figure 3. The Non-classical CD8+ T Cell Response Correlates with a Prolonged Inflammatory Phenotype following MCMV Infection.

(A) Serum IFN-γ levels from C57BL/6, KbDb−/− and β2m−/− mice on day 7 post-MCMV infection were determined by sandwich ELISA (n = 7).

(B) Serum IFN-γ levels from KbDb−/− mice on indicated days post-MCMV infection were determined by bead-based immunoassay (n = 8–9). Dotted line indicates limit of detection.

(C) Frequency of non-classical CD8+ T cells positive for indicated cytokine after restimulation ex vivo with CD3 and CD28 or media on day 7 post-MCMV infection (n = 13).

Data are pooled from two (A and C) or three (B) independent experiments and represent mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001.

Non-classical CD8+ T Cells Form Memory Populations in Long-Term Infected KbDb−/− Mice

We observed that KbDb−/− animals were protected from MCMV for upward of 11 months without outward signs of illness. This coincided with elevated populations of non-classical CD8+ T cells in the spleen and liver of long-term infected animals compared to naive controls (Figures S3A and S3B). Given the CD44hiCD62Llo phenotype of many naive non-classical CD8+ T cells, using the typical cell surface markers to distinguish central memory and effector memory populations in long-term infected animals was challenging. However, we did determine that CD44loCD62Lhi CD8+ T cells were capable of becoming CD44hiCD62Llo when transferred into congenic recipients and infected with MCMV (data not shown). We instead investigated whether non-classical CD8+ T cells were capable of developing a tissue-resident memory (TRM, CD69+CD103+) phenotype in the SMG. We found that non-classical CD8+ T cells were recruited to the SMG and persisted in this tissue (Figures 4A and S3C). Although there were fewer total CD8+ T cells compared to C57BL/6 mice (Figure 4B), the proportion of CD8+ T cells that were TRM was equivalent (Figures 4C and S3D).

Figure 4. Non-classical CD8+ T Cells Form Memory Populations and Are Sufficient to Protect against MCMV-Induced Lethality.

(A and B) Frequency (A) and number (B) of non-classical CD8+ T cells in the SMG from long-term infected KbDb−/− and C57BL/6 mice (n = 12).

(C) Frequency of CD8+ TRM cells (CD103+CD69+) in the SMG from long-term infected KbDb−/− and C57BL/6 mice (n = 12).

(D) Representative expansion and activation of donor non-classical CD8+ T cells (CD45.2+) transferred into KbDb−/−.SJL (CD45.1+) recipients, on day 7 post-MCMV infection. Donor CD8+ TM (KLRG1−CD27+) cells were sorted from long-term infected KbDb−/− mice.

(E) Frequency of donor and recipient non-classical CD8+ TEFF cells (KLRG1+CD127−) on day 7 post-infection (n = 7).

(F) Fold change of donor CD8+ T cell number, assuming 100% engraftment in indicated organ on day 7 post-infection (n = 7).

(G) Frequency of donor and recipient non-classical CD8+ TEFF cells (KLRG1+CD127) on day 7 post-infection (n = 8); KLRG1CD27+ donor cells were sorted from naive KbDb−/− mice prior to infection.

(H) Fold change of donor CD8+ T cell number, assuming 100% engraftment in indicated organ, on day 7 post-infection (n = 8).

(I) Survival of RAG1−/−KbDb−/− mice with (—) or without (- -) adoptive transfer of 5 × 104 sorted CD8+ TM cells (KLRG1CD27+) from long-term infected KbDb−/− mice (n = 6). Statistical analysis determined by Mantel-Cox test.

(J) Fold-change of donor cells in the spleen (n = 12) and liver (n = 6) of RAG1−/−KbDb−/− recipients upon euthanization between 10 to 16 weeks post-infection.

Data represent mean ± SEM and are pooled (A–C, E–H, and I) or representative (D and I) of at least two independent experiments. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001.

See also Figure S3.

We next wanted to determine how non-classical CD8+ T cells responded to secondary MCMV infection. Using an adoptive transfer approach, KLRG1CD27+ CD8+ T cells (TM) were isolated from long-term infected KbDb−/− mice and 5 × 104 cells were transferred into KbDb−/−.SJL recipients, which were then challenged with MCMV (Quinn et al., 2015). Donor cells underwent significant expansion, comprising up to of 25% of total splenic CD8+ T cells, and became highly activated upon secondary challenge (Figure 4D); this was greater than recipient non-classical CD8+ T cells, which only experienced their primary MCMV infection (Figure 4E). Assuming 100% engraftment in the spleen, this accounted for roughly a four-fold increase (Figure 4F). However, this is a substantial underrepresentation because donor cells were also found in other organs, including the liver and blood. In contrast, donor cells originating from naive animals constituted a very minor portion of recipient organs, and their activation was equivalent to that of recipient non-classical CD8+ T cells (Figures 4G and 4H). Together these data illustrate that non-classical CD8+ T cells in long-term infected animals are capable of forming memory populations.

Non-classical CD8+ T Cells Are Sufficient to Protect against MCMV-Induced Lethality

We next investigated the protective potential of non-classical CD8+ TM cells against MCMV. In MCMV-infected RAG1−/− mice, NK cells initially control infection, but eventually the animals succumb to the outgrowth of MCMV mutants (French et al., 2004). The addition of an adaptive immune component, such as CD8+ TM cells (KLRG1CD27+), is able to reverse this effect; however, naive cells cannot (Quinn et al., 2015). To avoid rejection of KbDb-deficient CD8+ T cells by NK cells in RAG1−/− mice, which would be killed for their lack of these “self” molecules, we generated RAG1−/−KbDb−/− animals. These mice received approximately 5 × 104 CD8+ TM cells from long-term infected KbDb−/− mice and were subsequently infected. As expected, RAG1−/−KbDb−/− controls succumbed to infection within 20 days, on average. In contrast, mice that received donor TM cells were protected against MCMV-induced lethality for upward of 100 days (Figure 4I). The antiviral effects of non-classical CD8+ T cells were confirmed by an absence of contaminating lymphocyte populations. In fact, when mice were euthanized between 10 and 16 weeks post-infection, robust populations of donor cells remained detectable (Figure 4J). Taken together, these data demonstrate that non-classical CD8+ T cells are able to successfully control MCMV infection as the sole component of the adaptive immune system.

Loss of Qa-1 Negatively Impacts the Non-classical CD8+ T Cell Response during MCMV Infection

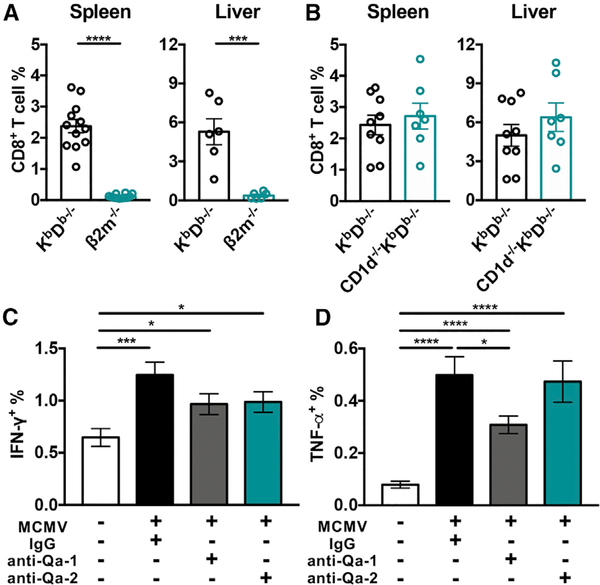

MCMV-expanded non-classical CD8+ T cells could be recognizing antigens presented by a number of MHC class Ib molecules. MHC class II-restricted CD8+ T cells have also been found under certain conditions, including following simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) vaccination in rhesus macaques (Hansen et al., 2013) and in HIV-infected individuals (Ranasinghe et al., 2016). We excluded MHC class II as a restricting element by comparing the expansion of non-classical CD8+ T cells in KbDb−/− and β2m−/− mice. Unlike KbDb−/− animals, β2m−/− mice had negligible CD8+ T cells present in the spleen and liver on day 7 post-infection, indicating restriction by one or more MHC class Ib molecules (Figures 5A and S4A). Mice encode over 30 MHC class Ib genes, many due to gene duplications, but only 21 of these are thought to be transcribed (Ohtsuka et al., 2008). However, not all of these are capable of binding peptides, such as HFE (Lebrón et al., 1998) and TL (encoded by H2-T3 and H2-T18) (Liu et al., 2003). Others present unique antigens that were unlikely in the context of a viral infection. For example, MR1 presents vitamin B metabolites, which are unique to bacteria and yeast (Kjer-Nielsen et al., 2012), and M3 binds N-formylated peptides of mitochondrial or prokaryotic origin (Wang et al., 1991). We, therefore, focused on three non-classical molecules, namely, CD1d, Qa-1, and Qa-2, which have been shown to present pathogen-derived antigens (Fischer et al., 2004; Bian et al., 2017; Swanson et al., 2008; Shang et al., 2016).

Figure 5. β2m and Qa-1 Contribute in the Non-classical CD8+ T Cell Response following MCMV Infection.

(A and B) Frequency of non-classical CD8+ T cells in the spleen and liver of (A) KbDb−/− and β2m−/− mice on day 7 post-MCMV infection (n = 6–12) or (B) KbDb−/− and CD1d−/−KbDb−/− mice (n = 7–9).

(C and D) Frequency of (C) IFN-γ+ and (D) TNF-α+ non-classical CD8+ T cells during ex vivo stimulation with uninfected or MCMV-infected KbDb−/− BMDCs in the presence of anti-Qa-1, anti-Qa-2, or immunoglobulin G (IgG) isotype control antibodies. CD8+ T cells were enriched from long-term infected KbDb−/− mice (n = 16).

Data are pooled from at least two independent experiments and represent mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001.

See also Figure S4.

The majority of MHC class Ib molecules are encoded in the same chromosome as MHC class Ia. CD1d is an exception, however, which allowed us to generate CD1d−/−KbDb−/− mice. We found that the magnitude of the CD8+ T cell response to MCMV was equivalent to KbDb−/− animals (Figures 5B and S4A), indicating that CD1d was dispensable. In contrast, to test the roles of Qa-1 and Qa-2, we performed an in vitro restimulation assay using blocking antibodies and bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs) derived from KbDb−/− mice. MCMV-infected BMDCs were capable of stimulating non-classical CD8+ T cells from long-term infected KbDb−/− mice to produce significantly more IFN-γ (p < 0.001) and TNF-α (p < 0.0001) compared to uninfected BMDCs (Figures 5C and 5D). Importantly although anti-Qa-2 treatment did not have any detectable effects, there was a significant decrease in TNF-α production following anti-Qa-1 treatment (p < 0.05), and a similar trend for IFN-γ (Figures 5C and 5D).

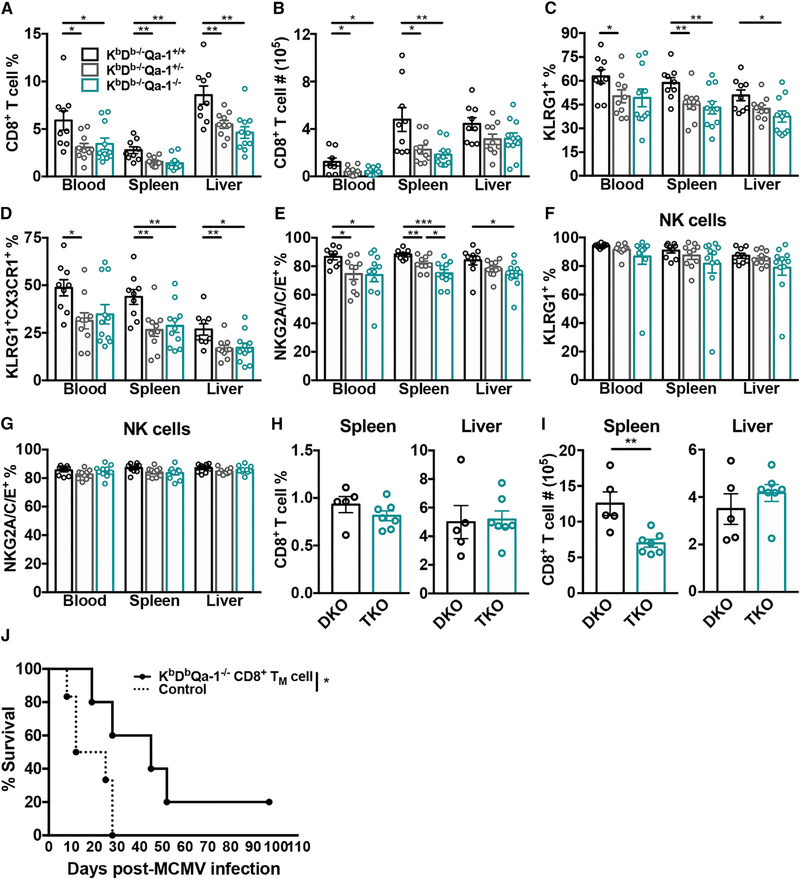

To validate these data, we generated KbDb−/−Qa-1−/− mice using CRISPR-Cas9 technology. Because H2-T23 is located approximately 0.8 megabases from H-2D, we targeted it directly on KbDb+/− zygotes (Figure 6A). The resultant line has a 184-bp deletion in the third exon and flanking intron of H2-T23 (Figure 6B) and completely lacks Qa-1 expression at the cell surface compared to KbDb−/−Qa-1+/+ and KbDb−/−Qa-1+/− littermate controls (Figure 6C). Qa-1 is normally expressed at low levels on the cell surface and becomes upregulated following MCMV infection; this is observed in littermate control animals, however, KbDb−/−Qa-1−/− mice remain Qa-1 negative (Figures 6D and 6E). As expected, Qa-1 cell surface expression in heterozygous mice was approximately half of wild-type levels (Figures 6C and 6D). The loss of Qa-1 in KbDb−/− mice did not appear to affect overall T cell development in the thymus (Figure 6F) or cause a further decrease in CD8+ T cell frequency or absolute number in naive animals (Figures 6G and 6H). We then examined the non-classical CD8+ T cell response in the resultant triple knockout and littermates on day 7 post-infection. We found that KbDb−/−Qa-1−/− mice had decreased frequencies of CD8+ T cells in the spleen, liver, and blood and decreased absolute numbers in the spleen and blood, with a similar trend in the liver (Figures 7A, 7B, and S4B). These data implied that a large component of the non-classical CD8+ T cell response during acute infection was comprised of Qa-1-restricted cells. Interestingly, the CD8+ T cell response was also compromised in KbDb−/−Qa-1+/− mice, which suggested a critical role for the level of Qa-1 expression. Remarkably, Qa-1-independent non-classical CD8+ T cells were also poorly activated during MCMV infection. This was evidenced by the reduced frequency of CD8+ T cells that were TEFFS (Figure 7C), terminally differentiated effectors (Figure 7D), and NKG2A/C/E+ from KbDb−/−Qa-1−/− animals (Figure 7E). However, this was not a global defect because the NK cell response was unaffected by the loss of Qa-1 signaling at this time point (Figures 7F and 7G). Long-term infected triple knockouts also had a decreased population of non-classical CD8+ T cells in the spleen (Figures 7H and 7I). Given the diminished response of these cells, we sought to investigate their protective capacity by adoptively transferring CD8+ TM (KLRG1−CD27+) cells from long-term infected KbDb−/−Qa-1−/− mice into RAG1−/−KbDb−/− animals. Surprisingly, in the absence of Qa-1-restricted cells, RAG1−/−KbDb−/− mice had diminished survival (Figure 7J). Overall, only 15% (2/13) of recipients that received CD8+ TM from KbDb−/−Qa-1−/− animals survived infection (data not shown). These data demonstrate that Qa-1-restricted T cells comprise a substantial and + essential portion of the non-classical CD8+ T cells responding to MCMV.

Figure 6. Non-classical CD8+ T Cells Are Unaffected by the Loss of Qa-1 Signaling in Naive KbDb−/−Qa-1−/− Mice.

(A) KbDb−/−Qa1−/− mice were generated using two guideRNA (gRNA; blue) targeted to exon 3 of H2-T23 and its flanking intron in KbDb+/− zygotes. Protospacer adjacent motifs (PAM; green) and beginning and end of deleted region (arrows) are indicated.

(B) Sequence of wild-type and mutant H2-T23, including premature stop codon (*).

(C and D) Qa-1 MFI on (C) total naive thymocytes (n = 3–4) and (D) splenic CD19+ lymphocytes on day 7 post-MCMV infection (n = 3–4) compared to secondary control (dotted line) from KbDb−/−Qa-1+/+ (WT), KbDb−/−Qa-1+/− (HET), and KbDb−/−Qa-1−/− (KO) mice.

(E) Representative histograms of Qa-1 expression on CD19+ lymphocytes from the spleen of indicated mice.

(F) The CD4−CD8− double negative (DN), CD4+CD8+ double positive (DP), and CD4+ and CD8+ single positive (SP) stages of T cell development in the thymus of indicated mice (n = 6–8).

(G) Frequency and (H) absolute number of CD8+ T cells in indicated organs from naive animals (n = 6–8).

Data represent mean ± SEM and are pooled from two (F–H) or representative of two (C–E) independent experiments. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001.

Figure 7. Loss of Qa-1 Negatively Impacts the Non-classical CD8+ T Cell Response and Their Protective Capabilities.

(A and B) Frequency (A) and absolute number (B) of non-classical CD8+ T cells in the spleen, liver, and blood of KbDb−/−Qa-1+/+, KbDb−/−Qa-1+/−, and KbDb−/−Qa-1−/− mice on day 7 post-MCMV infection (n = 9–11).

(C–G) KLRG1+CD127− (C), KLRG1+CX3CR1+ (D), and NKG2A/C/E+ (E) non-classical CD8+ T cells and KLRG1+ (F) and NKG2A/C/E+ NK (G) cells on day 7 post-MCMV infection from indicated organs of KbDb−/−Qa1+/+, KbDb−/−Qa1+/−, and KbDb−/−Qa1−/− mice (n = 9–11).

(H and I) Frequency (H) and absolute number (I) of CD8+ T cells from the spleen and liver of long-term infected KbDb−/−Qa1+/+ (DKO) and KbDb−/−Qa1−/− (TKO) mice (n = 5–7).

(J) Survival of RAG1−/−KbDb−/− mice with (—, n = 5) or without (- -, n = 6) adoptive transfer of 5 × 104 sorted CD8+ TM cells (KLRG1CD27+) from long-term infected KbDb−/−Qa-1−/− mice. Statistical analysis determined by Mantel-Cox test.

Data are pooled from two (H and I) or three independent experiments (A–G) or representative of three independent experiments (J). Data represent mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001.

See also Figure S4.

DISCUSSION

Increasing evidence demonstrates that MHC-class-Ib-restricted T cells are capable of responding to many bacterial and viral pathogens (Anderson and Brossay, 2016). Thus far, however, the non-classical T cell response to CMV has largely gone unappreciated. HLA-E-restricted T cells are detectable in a subset of HCMV seropositive individuals and respond to gpUL40 peptides ex vivo (Mazzarino et al., 2005); however, their participation and protective capabilities remain ambiguous and could have allogenic and autologous potential (Jouand et al., 2018). In this report, we provide evidence that non-classical CD8+ T cells can form memory and provide long-term protection against MCMV. We also established that the MHC class Ib molecule Qa-1 restricts a large component of this population and that both Qa-1- and non-Qa-1-restricted cells respond to MCMV with differing aptitudes.

Most non-classical T cells, such as iNKT and MAIT cells, are predisposed to rapid activation in the presence of agonist antigen and/or inflammatory cytokines but are unable to form memory (Godfrey et al., 2015). For example, M3-restricted T cells develop and respond before conventional CD8+ T cells during Listeria monocytogenes infection (Kerksiek et al., 1999) but do not expand after secondary challenge (Kerksiek et al., 1999; Kerksiek et al., 2003). Surprisingly, we discovered that MCMV-specific non-classical CD8+ T cells behave similarly to conventional TEFF cells, rather than innate-like T cells, during acute MCMV. This was illustrated by their lack of PLZF expression, kinetics of expansion and contraction, and formation of memory populations, including TRM cells in the SMG. More importantly, we demonstrated that non-classical CD8+ TM cells from long-term infected mice were capable of preventing lethal infection in immunocompromised mice. Others have shown that γδ T cells from previously infected animals can also prevent lethality (Khairallah et al., 2015; Sell et al., 2015); however, we achieved protection with up to 20 times fewer cells, akin to what was reported for conventional CD8+ TM cells (Quinn et al., 2015). This memory phenotype was somewhat surprising because non-classical T cells are believed to represent an ancient and evolutionarily conserved branch of the adaptive system (Joly and Rouillon, 2006; Linehan et al., 2018). However, in agreement with our findings, a recent study reported the characterization of three Qa-1-restricted CD8+ T cell clones that behave similarly to conventional T cells (Doorduijn et al., 2018).

Using neutralizing monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), we found that blocking Qa-1 inhibits the cytokine response of non-classical CD8+ TM cells following restimulation. The essential role of Qa-1 was further established using KbDb−/−Qa-1−/− mice, which exhibit an impaired CD8+ T cell response not only during acute infection, but also in long-term infected mice as well. It is possible this could be a consequence of increased NK cell-mediated regulation of anti-viral T cells, as recently shown with LCMV-infected Qa-1-deficient animals (Xu et al., 2017). However, we considered this unlikely because NK cells from MCMV-infected KbDb−/−Qa-1−/− animals were not hyperactivated, possibly due to a lack of MHC-class-I-mediated licensing. Interestingly, the CD8+ T cell response was affected in both KbDb−/−Qa-1+/− and KbDb−/−Qa-1−/− mice, indicating that Qa-1-restricted CD8+ T cell selection and/or function is tightly regulated by Qa-1 expression level.

In addition to its interaction with the TCR, Qa-1 also acts as a ligand for the inhibitory receptor CD94-NKG2A on NK and CD8+ T cells (Vance et al., 1998; Vance et al., 1999). This inhibitory signal has been shown to restrict the magnitude of activation for virus-specific CD8+ T cells following poxvirus (Rapaport et al., 2015) and polyoma virus infection (Moser et al., 2002), as well as NK cell-mediated killing of HCMV-infected cells (Tomasec et al., 2000). Loss of CD94-NKG2A signaling also results in abnormal T cell activation during Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection (Bian et al., 2017). In several of these studies, the absence of the CD94-NKG2A inhibitory signals was presumably amplified by the absence of Qa-1-restricted regulatory CD8+ T cells (Hu et al., 2004). Accordingly, we predicted that the residual CD8+ T cells in KbDb−/−Qa-1−/− mice would be hyper-responsive. Unexpectedly, the remaining CD8+ T cells were poorly activated after MCMV infection. Therefore, among the non-classical CD8+ T cell subsets, Qa-1-restricted CD8+ T cells may deliver the dominant response during MCMV infection. In support of this hypothesis, non-Qa-1-specific CD8+ TM cells were less capable of protecting immunocompromised mice from MCMV-induced lethality (Figure 7J). Given the critical role of Qa-1 restricted CD8+ T cells during MCMV infection, it will be interesting to determine whether these cells can respond to nonrelated viruses.

In addition to Qdm, Qa-1 and HLA-E present a diverse peptide repertoire. In its absence, Qa-1 preferentially binds a peptide derived from heat shock protein 60 (Hsp60), which is upregulated on stressed cells (Davies et al., 2003). Hsp60 is homologous to prokaryotic GroEL, and Qa-1 can also present GroEL-derived antigens from Salmonella typhimurium; however, GroEL-specific CD8+ T cells are cross-reactive and can lyse stressed macrophages (Lo et al., 2000). When endoplasmic reticulum amino peptidase 1 (ERAAP1) is dysfunctional, Qa-1 loads the self-peptide FL9, which allows FL9-specific CD8+ T cells to survey for, and eliminate, ERAAP1-deficient cells (Nagarajan et al., 2012). In humans, HLA-E-restricted T cells specific for the HCMV gpUL40 (Tomasec et al., 2000; Ulbrecht et al., 2000) also lead to alloreactivity, depending on a person’s HLA genotype (Romagnani et al., 2004). Importantly, MCMV does not encode a UL40 homolog; therefore, the MCMV-derived antigen recognized by Qa-1-restricted CD8+ T cells is unlikely to induce alloreactivity. This was substantiated by MHC class Ib-restricted CD8+ TM cells protecting against lethal infection for upward of 100 days, without apparent signs of autoimmunity. However, further work is required to identify the MCMV-derived peptide(s) presented by Qa-1.

To conclude, even though no single immune component is necessary during CMV infection, a multilayered response is compulsory to keep this highly immunoevasive virus suppressed. CMV uses multiple mechanisms to elude individual cell types, with at least seven CMV-encoded genes described to avoid the NK cell response alone (Wilkinson et al., 2008). Here, we provide evidence of a protective MHC class Ib-restricted CD8+ T cell response to MCMV, including both Qa-1-restricted and non-Qa-1-restricted cells. Qa-1 and HLA-E-restricted T cells have been relatively overlooked, but recent evidence suggests that these populations have the potential to exploit immunoevasion in a CMV-based vaccine (Hansen et al., 2016). Remarkably, we show here that they can form memory and substitute for conventional T cells. This suggests that Qa-1-restricted cells may represent a category of T cells positioned between innate-like and adaptive T cells, whose activity might only be revealed when the conventional T cell response is absent or impeded.

STAR⋆METHODS

CONTACT FOR REAGENT AND RESOURCE SHARING

Requests for information and reagents may be directed to the Lead Contact, Laurent Brossay (Laurent_brossay@brown.edu).

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL DETAILS

Mice

KbDb−/− mice were purchased from Taconic Biosciences and then maintained in-house. B6.SJL mice (Taconic) were crossed with KbDb−/− mice to obtain congenic KbDb−/− (KbDb−/−.SJL) animals. For certain experiments, KbDb−/− and KbDb−/−.SJL mice were used interchangeably as KbDb−/−. CD1d−/− mice (Jackson Laboratory) and RAG1−/− mice (Jackson Laboratory) were crossed with KbDb−/− mice to obtain CD1d−/−KbDb−/− and RAG1−/−KbDb−/− animals, respectively. C57BL/6 and β2m−/− mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratory. C57BL/6 mice were used as wild-type controls. None of the experiments within these studies were blinded or randomized. Both age- and sex-matched mice were used for this study, which was carried out in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, as defined by the National Institutes of Health (PHS Assurance #A3284–01). Animal protocols were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Brown University. All animals were housed in a centralized and AAALAC-accredited research animal facility that is fully staffed with trained husbandry, technical, and veterinary personnel.

Generation of KbDb−/−Qa-1−/− mice via CRISPR/Cas9

Two guideRNAs (gRNA) were used to target H2-T23 and create a deletion in exon 3 and its flanking intron: 5′-GGCTATGT CATTCGCGGTCC-3′ (gRNA 1) and 5′-GGATTTCCCCCAAACCGCAG-3 (gRNA 2). gRNAs were selected using CHOPCHOP (http://chopchop.cbu.uib.no) and CRISPR design (http://zlab.bio/guide-design-resources) online tools (Labun et al., 2016; Montague et al., 2014; Hsu et al., 2013), and produced using the T7 gRNA SmartNuclease Synthesis Kit (System Biosciences). Cas9/gRNA injection was performed on KbDb+/− zygotes using GeneArt CRISPR Nuclease mRNA (ThermoFischer). Founders were genotyped and bred to KbDb−/− mice for two generations. Two sets of primers were used for genotyping KbDb−/−Qa-1−/− mice. (1) Qa-1 external fwd: TCTGCTTAGGTTTGGGGTTG and Qa-1 external rev: CTACAGGGGAAAAGCAGTTTTG produce a 524 bp wild-type band and a 340 bp mutant band. (2) Qa-1 WT fwd: CATCCAAACGCCTACCCAGA and Qa-1 WT rev: TGAGGCTATGTCATTCGCGG produce a 303 bp wild-type band and no mutant PCR product.

Virus and infection protocol

MCMV-RVG102 was a gift from Dr. John Hamilton (Duke University) and expresses recombinant EGFP under the immediate early-1 promoter (Henry et al., 2000). Infections were performed with 5 × 104 or 1 × 105 PFU i.p. A mouse was only excluded from analysis if determined to be aberrantly infected, based on lack of KLRG1 upregulation in the animal. Stocks were prepared in vivo from SMG homogenate (Orange et al., 1995) and its titer (PFU) determined via standard plaque assay using mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) cells. Briefly, MEF cells were grown in 10% DMEM-serum at 37°C with 7% CO2 and then infected for six days in a methylcellulose overlay, fixed with 10% formalin, and stained with crystal violet to visualize plaques. Mice were considered long-term infected at > 8 weeks post-MCMV infection.

METHOD DETAILS

Lymphocyte isolation

Spleens were dissociated in 1% PBS-serum, filtered through nylon mesh, and underlayed with lympholyte-M (Cedarlane Laboratories). Alternatively, spleens were dissociated in 150 mM NH4Cl for 10 minutes, filtered through nylon mesh, and washed twice with 1% PBS-serum. Livers were perfused with 1% PBS-serum, dissociated using GentleMACS program E0.1 (Miltenyi Biotech) and passed through nylon mesh. Samples were washed three times in 1% PBS-serum and overlayed onto a two-step discontinuous Percoll gradient (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences). SMG were cleaned of connective tissue and lymph nodes and dissociated in collagenase IV (Sigma-Aldrich) using GentleMACS program Heart 01.01. Samples were incubated at 37°C with shaking for 5 minutes, followed by the Heart 01.01 program; five-minute incubation and Heart 01.01 program were then repeated. Samples were filtered through nylon mesh, washed once in 1% PBS-serum, and underlayed with Lympholyte-M. All gradients were centrifuged at 2500 RPM for 20 minutes at room temperature. Blood was collected from a cardiac puncture into heparin-containing tubes. Red blood cells were lysed in 150 mM NH4Cl for 10 minutes and washed twice in 1% PBS-serum. To obtain serum, blood was allowed to clot at room temperature, in the absence of heparin, for 4 hours and stored at 4°C overnight. Serum was collected following centrifugation at 4°C. Live cell counts were obtained using either a hemocytometer/trypan blue exclusion or a MACSQuant/propidium iodide exclusion.

Viral quantification by qPCR

DNA was extracted using a DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (QIAGEN) and viral quantification was determined as copy number of the MCMV gene IE1, compared to a standard curve of the full-length IE1 gene. For the standard, MCMV IE1 was amplified using IE1-full Forward: 5′-TGTCGCCAACAAGATCCTCG-3′ and IE1-full Reverse: 5′-CCCTGCCTGCTGTTCTT-3′ and cloned into a pCR-Blunt vector using a Zero Blunt PCR cloning kit (Invitrogen) (Kamimura and Lanier, 2014). qPCRs were performed in triplicate on a CFX384 Real-Time System (Bio-Rad) using iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) and the following primers: IE1 Forward: 5′-GAGTCTGGAACCGAAACCGT-3′ and IE1 Reverse: 5′-GTCGCTGTTATCATTCCCCAC-3′ (Quatrini et al., 2018). Copy number was calculated using CFX Maestro software (Rio-Rad). Samples at, or below, the lowest standard were set to the limit of detection.

In vivo cell proliferation dye experiments

Splenocytes were labeled with cell proliferation dye eF450 (eBioscience) per the manufacturer’s instructions. CD8+ T cells were enriched using an AutoMACS (Miltenyi Biotech) and CD8α MicroBeads (Miltenyi Biotech) and i.v. injected into KbDb−/−.SJL recipients. Two hours post-injection, recipients were left naive, stimulated with 50 mg CPG ODN (Invivogen) + 100 μg Poly(I:C) (Sigma-Aldrich), or infected with MCMV. On day 2, mice received second dose of 50 μg CPG ODN + 100 μg Poly(I:C). Donor CD8+ T cell proliferation was analyzed on day 4.

Serum cytokine production

Serum cytokines from time-course experiments were measured by LEGENDPlex bead-based immunoassay using the Mouse Th Cytokine Panel (13-plex), per the manufacturer’s instructions (Biolegend). Serum IFN-γ levels on day 7 post-MCMV were determined via sandwich ELISA using the following antibodies: purified IFN-γ (clone R4–6A2, eBioscience), Biotin-IFN-γ (clone XMG1.2, eBioscience), and peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin (Jackson ImmunoResearch Labs) (Wesley et al., 2005).

Secondary MCMV challenge and survival studies

Samples were enriched for CD8+ cells using an AutoMACS or OctoMACS and either CD8α MicroBeads or CD19 MicroBeads (Miltenyi Biotech). 50,000 CD8+ TM cells (CD8+KLRG1−CD27+) sorted from long-term infected KbDb−/− spleens or KbDb−/−Qa-1−/− spleens were adoptively transferred per recipient. For survival studies, cells were injected i.v. into RAG1/KbDb−/− mice and three hours post-injection, recipients were infected with MCMV. For secondary MCMV infections, cells were injected i.v. into KbDb−/−.SJL mice and recipients were infected two or three hours post-injection.

In vitro CD8+ T cell stimulation and BMDC cultures

KbDb−/− BMDCs were prepared in vitro by flushing femurs and tibias with 1% PBS-serum. 1 × 107 cells were grown in 10% DMEM-serum + 10 ng/ml GM-CSF (eBioscience) in a T75 flask and media was replaced on day 3. On day 6, suspended and loosely adherent cells were harvested and plated 1 × 105 cells/well of a 96-well plate. BMDC were infected with 1 × 105 PFU MCMV (MOI 1), plates were centrifuged at 2000 RPM for 20 minutes at room temperature, and then incubated 2 hours at 37°C. Cells were washed one time with 10% DMEM-serum and fresh 10% DMEM-serum + 10 ng/ml GM-CSF (eBioscience) was added. BMDCs were used on day 2-post infection for in vitro stimulation experiments. CD8+ T cells were enriched from individual KbDb−/− spleens using an AutoMACS (Miltenyi Biotech) and CD8α MicroBeads (Miltenyi Biotech). 1 × 105 cells were plated in triplicate onto uninfected or MCMV-infected BMDCs for 6 hours at 37°C in 10% DMEM-serum + GolgiPlug Protein Transport Inhibitor (BD Biosciences), per the manufacturer’s instructions. Infected BMDCs were pretreated for at least 30 minutes with 20 μg/ml of either mouse anti-mouse Qa-1 (BD Biosciences), mouse anti-mouse Qa-2 (BioLegend), or mouse anti-mouse IgG2a isotype control (eBioscience). Antibodies were also present throughout the 6-hour incubation. Following incubation, triplicate samples were pooled and stained for intracellular IFN-γ and TNF-α production. For restimulation of cells on day 7 post-infection, wells of a 96-well plate were coated with 0.5 μg anti-mouse CD3 and CD28 antibodies (eBioscience).

Antibodies and flow cytometry

Cells were stained in 1% PBS-serum containing Fc block (2.4G2) and cell surface antibodies for 20 minutes on ice in the dark. Qa-1 staining was performed with a Biotin-conjugated Qa-1 antibody for 30 minutes on ice, followed by a Streptavidin-conjugated fluorophore for 30 minutes. Staining with CD1d tetramer (NIH Tetramer Core Facility) was performed for 15 minutes at room temperature and 15 minutes on ice. For intracellular staining, cells were fixed using Cytofix/Cytoperm (BD Biosciences) for 30 minutes and stained in Perm/Wash Buffer (BD Biosciences) for 30 minutes. For intranuclear staining, cells were fixed using Fixation/Permeabilization Solution (eBioscience) for 30 minutes and stained in Permeabilization Buffer (eBioscience) for 30 minutes. Samples were run on a FACSAria III (BD Biosciences) or MACSQuant (Miltenyi Biotech) and analyzed using FlowJo (Tree Star Inc.). The mAbs listed below were used for flow cytometry and purchased from BioLegend, eBioscience, Thermo Fischer Scientific, or BD Biosciences: APC-CD45.2, APC-CD103, APC-CX3CR1, APC-Streptavidin, APC-eF780-CD44, APC-eF780-CD45.1, APC-eF780-CD45.2, APC-eF780-KLRG1, Biotin-Qa-1, BV421-CD127, BV421-CD1d loaded tetramer, BV510-TCRβ, BV570-CD4, BV605-CD8a, BV711-CD62L, BV785-NK1.1, eF450-CD8a, eF450-CD45.1, eF450-TNF-α, FITC-CD69, FITC-Granzyme B, FITC-NKG2A/C/E, FITC-TCRβ, PE-CD8β.2, PE-CD19, PE-CD27, PE-CD69, PE-CX3CR1, PE-IFN-γ, PE-PLZF, PE-TCRβ, PE-Cy7-Granzyme B,PE-Cy7-IFN-γ, PE-Cy7-KLRG1, PE-Cy7-T-bet, PerCP-Cy5.5-CD69, PerCP-Cy5.5-TCRβ, PerCP-eF710-CD27, PerCP-eF710-CD127, PerCP-eF710-NKG2A/C/E. Brilliant Stain Buffer (BD Biosciences) was added to staining cocktail when Brilliant Violet antibodies were used.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Statistical analysis

All analyses for determining statistical significance were performed using Prism 7.0 (Graph-Pad Software, Inc.). Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t tests were used to compare two individual groups and Log-rank (Mantel Cox) tests were used for survival studies. Graphs represent the mean and error bars indicate standard error of the mean (SEM). The number of animals/sample size and total experimental replicates are indicated within each figure legend. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 and ****p < 0.0001.

Supplementary Material

KEY RESOURCES TABLE.

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

| Antibodies | ||

| APC anti-mouse CD45.2 | Thermo Fischer Scientific | Cat#: 17–0454-82; RRID: AB_469400 |

| APC anti-mouse CD103 | Thermo Fischer Scientific | Cat#: 17–1031-80; RRID: AB_1106993 |

| APC anti-mouse CX3CR1 | BioLegend | Cat#: 149007; RRID: AB_2564491 |

| APC Streptavidin | Thermo Fischer Scientific | Cat#: 17–4317-82 |

| APC-eF780 anti-human/mouse CD44 | Thermo Fischer Scientific | Cat#: 47–0441-82; RRID: AB_1272244 |

| APC-eF780 anti-mouse CD45.1 | Thermo Fischer Scientific | Cat#: 47–0453-82; RRID: AB_1582228 |

| APC-eF780 anti-mouse CD45.2 | Thermo Fischer Scientific | Cat#: 47–0454-82; RRID: AB_1272175 |

| APC-Cy7 anti-mouse/human KLRG1 | BioLegend | Cat#: 138426; RRID: AB_2566554 |

| Biotin anti-mouse IFN-γ | Thermo Fischer Scientific | Cat#: 13–7311-85; RRID: AB_466937 |

| Biotin anti-mouse Qa-1 | BD Biosciences | Cat#: 559829; RRID: AB_397345 |

| BV421 anti-mouse CD127 | BioLegend | Cat#: 135027; RRID: AB_2563103 |

| BV421 mouse CD1d tetramer loaded with PBS-57 | NIH Tetramer Core Facility | N/A |

| BV510 anti-mouse TCRβ | BioLegend | Cat#: 109234; RRID: AB_2562350 |

| BV570 anti-mouse CD4 | BioLegend | Cat#: 100542; RRID: AB_2563051 |

| BV605 anti-mouse CD8a | BioLegend | Cat#: 100744; RRID: AB_2562609 |

| BV711 anti-mouse CD62L | BioLegend | Cat#: 104445; RRID: AB_2564215 |

| BV785 anti-mouse NK1.1 | BioLegend | Cat#: 108749; RRID: AB_2564304 |

| eF450 anti-mouse CD8a | Thermo Fischer Scientific | Cat#: 48–0081-82; RRID: AB_1272198 |

| eF450 anti-mouse CD45.1 | Thermo Fischer Scientific | Cat#: 48–0453-80; RRID: AB_1272225 |

| eF450 anti-mouse TNF-α | Thermo Fischer Scientific | Cat#: 48–7321-80; RRID: AB_1548828 |

| FITC anti-mouse CD69 | Thermo Fischer Scientific | Cat#: 11–0691-85; RRID: AB_465120 |

| FITC anti-mouse Granzyme B | Thermo Fischer Scientific | Cat#: 11–8898-82; RRID: AB_10733414 |

| FITC anti-mouse NKG2A/C/E | BD Biosciences | Cat#: 550520; RRID: AB_393723 |

| FITC anti-mouse TCRβ | BioLegend | Cat#: 109206; RRID: AB_313429 |

| FITC anti-mouse TCRβ | Thermo Fischer Scientific | Cat#: 11–5961-82; RRID: AB_465323 |

| PE anti-mouse CD8β.2 | BD Biosciences | Cat#: 553041; RRID: AB_394577 |

| PE anti-mouse CD19 | Thermo Fischer Scientific | Cat#: 12–0193-82; RRID: AB_657659 |

| PE anti-mouse/human/rat CD27 | Thermo Fischer Scientific | Cat#: 12–0271-82; RRID: AB_465614 |

| PE anti-mouse CD69 | Thermo Fischer Scientific | Cat#: 12–0691-83; RRID: AB_465733 |

| PE anti-mouse CX3CR1 | BioLegend | Cat#: 149005; RRID: AB_2564314 |

| PE anti-mouse IFN-γ | Thermo Fischer Scientific | Cat#: 12–7311-82; RRID: AB_466193 |

| PE anti-mouse PLZF | BioLegend | Cat#: 145804; RRID: AB_2561973 |

| PE anti-mouse TCRβ | Thermo Fischer Scientific | Cat#: 12–5961-83; RRID: AB_466067 |

| PE-Cy7 anti-mouse Granzyme B | Thermo Fischer Scientific | Cat#: 25–8898-80; RRID: AB_10853338 |

| PE-Cy7 anti-mouse IFN-γ | Thermo Fischer Scientific | Cat#: 25–7311-82; RRID: AB_469680 |

| PE-Cy7 anti-mouse KLRG1 | Thermo Fischer Scientific | Cat#: 25–5893-82; RRID: AB_1518768 |

| PE-Cy7 anti-human/mouse T-bet | Thermo Fischer Scientific | Cat#: 25–5825-80; RRID: AB_11041809 |

| PerCP-Cy5.5 anti-mouse CD69 | BD Biosciences | Cat#: 561931; RRID: AB_10892815 |

| PerCP-Cy5.5 anti-mouse TCRβ | BioLegend | Cat#: 109228; RRID: AB_1575173 |

| PerCP-eF710 anti-mouse/rat/human CD27 | Thermo Fischer Scientific | Cat#: 46–0271-80; RRID: AB_1834448 |

| PerCP-eF710 anti-mouse CD127 | Thermo Fischer Scientific | Cat#: 46–1273-80; RRID: AB_2573709 |

| PerCP-eF710 anti-mouse NKG2A/C/E | Thermo Fischer Scientific | Cat#: 46–5896-82; RRID: AB_10853352 |

| Peroxidase-conjugated Streptavidin | Jackson ImmunoResearch | Cat#: 016–030-084; RRID: AB_2337238 |

| Purified anti-mouse CD3e | Thermo Fischer Scientific | Cat#: 14–0031-85; RRID: AB_467050 |

| Purified anti-mouse CD16/CD32 (Fc block, 2.4G2) | In-house produced | N/A |

| Purified anti-mouse CD28 | Thermo Fischer Scientific | Cat#: 14–0281-85; RRID: AB_467191 |

| Purified anti-mouse IFN-γ | Thermo Fischer Scientific | Cat#: 14–7312-85; RRID: AB_468470 |

| Purified anti-mouse IgG2a kappa Isotype Control | Thermo Fischer Scientific | Cat#: 16–4724-85; RRID: AB_470165 |

| Purified anti-mouse Qa-1b | BD Biosciences | Cat#: 559827; RRID: AB_397344 |

| Purified anti-mouse Qa-2 | BioLegend | Cat#: 121711; RRID: AB_2650759 |

| Virus Strains | ||

| MCMV-RVG102 | Produced in house | Henry et al., 2000 |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| Ammonium chloride | Fisher Scientific | Cat# A661–500 |

| Brilliant Stain Buffer | BD Biosciences | Cat#: 563794 |

| CPG ODN 1826 | InvivoGen | Cat#: tlrl-modn |

| Collagenase, Type IV | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#: C5138 |

| Fixation and Permeabilization Solution | BD Biosciences | Cat#: 554722 |

| Fixation/Permeabilization Concentrate | eBioscience | Cat#: 00–5123-43 |

| Fixation/Permeabilization Diluent | eBioscience | Cat#: 00–5223-56 |

| GolgiPlug Protein Transport Inhibitor (Brefeldin A) | BD Biosciences | Cat#: 555029 |

| Heparin sodium salt | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#: H3393–500KU |

| Lympholyte-M | Cedarlane Laboratories | Cat#: CL5035 |

| Percoll | GE Healthcare | Cat#: 17–0891-01 |

| Permeabilization Buffer (10X) | eBioscience | Cat#: 00–8333-56 |

| Perm/Wash Buffer | BD Biosciences | Cat#: 554723 |

| Peroxidase Substrate Solution A | KPL | Cat#: 50–64-02 |

| Peroxidase Substrate Solution B | KPL | Cat#: 50–65-02 |

| Polyinosinic–polycytidylic acid potassium salt (Poly(I:C)) | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#: P9582–50MG |

| Recombinant Murine GM-CSF Protein | eBioscience | Cat#: 14–8331 |

| UltraComp eBeads, Compensation Beads | Invitrogen | Cat#: 01–2222-42 |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| CD8a (Ly-2) Microbeads, Mouse | Miltenyi Biotec | Cat#: 130–049-401 |

| CD8a (Ly-2) Microbeads, Mouse | Miltenyi Biotec | Cat#: 130–117-044 |

| CD19 Microbeads, Mouse | Miltenyi Biotec | Cat#: 130–052-201 |

| Cell Proliferation Dye, eF450 | eBioscience | Cat#: 65–0842-85 |

| DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit | QIAGEN | Cat#: 69506 |

| GeneArt CRISPR Nuclease mRNA | ThermoFischer | Cat#: A29378 |

| iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix | Bio-Rad | Cat#: 1725121 |

| LEGENDPlex Mouse Th Cytokine Panel (13-plex) | BioLegend | Cat #: 740005 |

| T7 gRNA SmartNuclease Synthesis Kit | System Biosciences | Cat#: CAS510A-KIT |

| Zero Blunt PCR Cloning Kit | Invitrogen | Cat#: 44–0302 |

| Experimental Models: Mouse Strains | ||

| β2m−/− | Jackson | Cat #: 002087; RRID: IMSR_JAX:002087 |

| B6.SJL | Taconic | Cat #: 4007; RRID: IMSR_TAC:4007 |

| C57BL/6 (B6) | Jackson | Cat #: 000664; RRID: IMSR_JAX:000664 |

| CD1d−/− | Jackson | Cat #: 008881; RRID: IMSR_JAX:008881 |

| CD1d−/−KbDb−/− | This paper | N/A |

| KbDb−/− | Taconic | Cat #: 4215 |

| KbDb−/−.SJL | This paper | N/A |

| KbDb−/−Qa-1−/− | This paper | N/A |

| RAG1−/− | Jackson | Cat #: 002216; RRID: IMSR_JAX:002216 |

| RAG1−/−KbDb−/− | This paper | N/A |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| H2-T23 gRNA1: 5′-GGCTATGTCATTCGCGGTCC-3′ | Produced in house | N/A |

| H2-T23 gRNA2: 5′-GGATTTCCCCCAAACCGCAG-3 | Produced in house | N/A |

| Qa-1 external fwd: 5′-TCTGCTTAGGTTTGGGGTTG-3′ | IDT | Custom |

| Qa-1 external rev: 5′-CTACAGGGGAAAAGCAGTTTTG-3′ | IDT | Custom |

| Qa-1 WT fwd: 5′-CATCCAAACGCCTACCCAGA-3′ | IDT | Custom |

| Qa-1 WT rev: 5′-TGAGGCTATGTCATTCGCGG-3′ | IDT | Custom |

| IE1 Forward: 5′-GAGTCTGGAACCGAAACCGT-3′ | IDT | Quatrini et al., 2018 |

| IE1 Reverse: 5′-GTCGCTGTTATCATTCCCCAC-3′ | IDT | Quatrini et al., 2018 |

| IE1-full Forward: 5′-TGTCGCCAACAAGATCCTCG-3′ | IDT | Kamimura and Lanier, 2014 |

| IE1-full Reverse: 5′-CCCTGCCTGCTGTTCTT-3′ | IDT | Kamimura and Lanier, 2014 |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| CFX Maestro | Bio-Rad | N/A |

| CHOPCHOP, v1 |

Labun et al., 2016; Montague et al., 2014 |

http://chopchop.cbu.uib.no |

| CRISPR Design, v1 | Hsu et al., 2013 | http://zlab.bio/guide-design-resources |

| FlowJo, v10 | FlowJo, LLC (Tree Star, Inc.) | https://www.flowjo.com |

| Prism 7.0 | GraphPad Software | https://www.graphpad.com |

| Other | ||

| autoMACS | Miltenyi Biotec | N/A |

| BD FACSAria III | BD Biosciences | N/A |

| CFX384 Real-Time System | Bio-Rad | N/A |

| gentleMACS | Miltenyi Biotec | N/A |

| MACSQuant | Miltenyi Biotec | N/A |

| OctoMACS | Miltenyi Biotec | N/A |

Highlights.

MHC class Ib-restricted CD8+ T cells participate during MCMV infection

This population behaves like conventional T cells, rather than innate-like T cells

These cells can protect against MCMV-induced lethality without other T and B cells

Qa-1-restricted cells are an essential component for the non-classical response

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Kevin Carlson for cell sorting, Cé line Fugè re for intravenous (i.v.) injections, and the NIH Tetramer Core Facility for CD1d-loaded tetramers. We also thank Dr. John Hamilton for MCMV-RVG102 and Dr. Russel Vance for scientific discussions. This work was supported by NIH research grants R01 AI046709 (L.B.), R01 AI122217 (L.B.), and F31 AI124556 (C.K.A.). This work was also supported by an American Association of Immunologists Career in Immunology Fellowship (L.B.).

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no competing interests.

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2019.03.059.

REFERENCES

- Aldrich CJ, DeCloux A, Woods AS, Cotter RJ, Soloski MJ, and Forman J (1994). Identification of a Tap-dependent leader peptide recognized by alloreactive T cells specific for a class Ib antigen. Cell 79, 649–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson CK, and Brossay L (2016). The role of MHC class Ib-restricted T cells during infection. Immunogenetics 68, 677–691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bate SL, Dollard SC, and Cannon MJ (2010). Cytomegalovirus seroprevalence in the United States: the national health and nutrition examination surveys, 1988–2004. Clin. Infect. Dis 50, 1439–1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bian Y, Shang S, Siddiqui S, Zhao J, Joosten SA, Ottenhoff THM, Cantor H, and Wang CR (2017). MHC Ib molecule Qa-1 presents Mycobacterium tuberculosis peptide antigens to CD8+ T cells and contributes to protection against infection. PLoS Pathog. 13, e1006384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braud V, Jones EY, and McMichael A (1997). The human major histocompatibility complex class Ib molecule HLA-E binds signal sequence-derived peptides with primary anchor residues at positions 2 and 9. Eur. J. Immunol 27, 1164–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braud VM, Allan DS, O’Callaghan CA, Söderström K, D’Andrea A, Ogg GS, Lazetic S, Young NT, Bell JI, Phillips JH, et al. (1998). HLA-E binds to natural killer cell receptors CD94/NKG2A, B and C. Nature 391, 795–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies A, Kalb S, Liang B, Aldrich CJ, Lemonnier FA, Jiang H, Cotter R, and Soloski MJ (2003). A peptide from heat shock protein 60 is the dominant peptide bound to Qa-1 in the absence of the MHC class Ia leader sequence peptide Qdm. J. Immunol 170, 5027–5033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doorduijn EM, Sluijter M, Querido BJ, Seidel UJE, Oliveira CC, van der Burg SH, and van Hall T (2018). T Cells Engaging the Conserved MHC Class Ib Molecule Qa-1b with TAP-Independent Peptides Are Semi-Invariant Lymphocytes. Front. Immunol 9, 60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer K, Scotet E, Niemeyer M, Koebernick H, Zerrahn J, Maillet S, Hurwitz R, Kursar M, Bonneville M, Kaufmann SH, and Schaible UE (2004). Mycobacterial phosphatidylinositol mannoside is a natural antigen for CD1d-restricted T cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 10685–10690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French AR, Pingel JT, Wagner M, Bubic I, Yang L, Kim S, Koszinowski U, Jonjic S, and Yokoyama WM (2004). Escape of mutant double-stranded DNA virus from innate immune control. Immunity 20, 747–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlach C, Moseman EA, Loughhead SM, Alvarez D, Zwijnenburg AJ, Waanders L, Garg R, de la Torre JC, and von Andrian UH (2016). The Chemokine Receptor CX3CR1 Defines Three Antigen-Experienced CD8 T Cell Subsets with Distinct Roles in Immune Surveillance and Homeostasis. Immunity 45, 1270–1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey DI, Uldrich AP, McCluskey J, Rossjohn J, and Moody DB (2015). The burgeoning family of unconventional T cells. Nat. Immunol 16, 1114–1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosse SD, Ross DS, and Dollard SC (2008). Congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection as a cause of permanent bilateral hearing loss: a quantitative assessment. J. Clin. Virol 41, 57–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halenius A, Gerke C, and Hengel H (2015). Classical and non-classical MHC I molecule manipulation by human cytomegalovirus: so many targets—but how many arrows in the quiver? Cell. Mol. Immunol 12, 139–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen SG, Sacha JB, Hughes CM, Ford JC, Burwitz BJ, Scholz I, Gilbride RM, Lewis MS, Gilliam AN, Ventura AB, et al. (2013). Cytomegalovirus vectors violate CD8+ T cell epitope recognition paradigms. Science 340, 1237874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen SG, Wu HL, Burwitz BJ, Hughes CM, Hammond KB, Ventura AB, Reed JS, Gilbride RM, Ainslie E, Morrow DW, et al. (2016). Broadly targeted CD8+ T cell responses restricted by major histocompatibility complex E. Science 351, 714–720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry SC, Schmader K, Brown TT, Miller SE, Howell DN, Daley GG, and Hamilton JD (2000). Enhanced green fluorescent protein as a marker for localizing murine cytomegalovirus in acute and latent infection. J. Virol. Methods 89, 61–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzapfel KL, Tyznik AJ, Kronenberg M, and Hogquist KA (2014). Antigen-dependent versus -independent activation of invariant NKT cells during infection. J. Immunol 192, 5490–5498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu PD, Scott DA, Weinstein JA, Ran FA, Konermann S, Agarwala V, Li Y, Fine EJ, Wu X, Shalem O, et al. (2013). DNA targeting specificity of RNA-guided Cas9 nucleases. Nat. Biotechnol 31, 827–832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu D, Ikizawa K, Lu L, Sanchirico ME, Shinohara ML, and Cantor H (2004). Analysis of regulatory CD8 T cells in Qa-1-deficient mice. Nat. Immunol 5, 516–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson SE, Mason GM, and Wills MR (2011). Human cytomegalovirus immunity and immune evasion. Virus Res. 157, 151–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joly E, and Rouillon V (2006). The orthology of HLA-E and H2-Qa1 is hidden by their concerted evolution with other MHC class I molecules. Biol. Direct 1, 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jouand N, Bressollette-Bodin C, Gérard N, Giral M, Guérif P, Rodallec A, Oger R, Parrot T, Allard M, Cesbron-Gautier A, et al. (2018). HCMV triggers frequent and persistent UL40-specific unconventional HLA-E-restricted CD8 T-cell responses with potential autologous and allogeneic peptide recognition. PLoS Pathog. 14, e1007041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamimura Y, and Lanier LL (2014). Rapid and sequential quantitation of salivary gland-associated mouse cytomegalovirus in oral lavage. J. Virol. Methods 205, 53–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerksiek KM, Busch DH, Pilip IM, Allen SE, and Pamer EG (1999). H2-M3-restricted T cells in bacterial infection: rapid primary but diminished memory responses. J. Exp. Med 190, 195–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerksiek KM, Ploss A, Leiner I, Busch DH, and Pamer EG (2003). H2-M3-restricted memory T cells: persistence and activation without expansion. J. Immunol 170, 1862–1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khairallah C, Netzer S, Villacreces A, Juzan M, Rousseau B, Dulanto S, Giese A, Costet P, Praloran V, Moreau JF, et al. (2015). γδ T cells confer protection against murine cytomegalovirus (MCMV). PLoS Pathog. 11, e1004702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjer-Nielsen L, Patel O, Corbett AJ, Le Nours J, Meehan B, Liu L, Bhati M, Chen Z, Kostenko L, Reantragoon R, et al. (2012). MR1 presents microbial vitamin B metabolites to MAIT cells. Nature 491, 717–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovalovsky D, Uche OU, Eladad S, Hobbs RM, Yi W, Alonzo E, Chua K, Eidson M, Kim HJ, Im JS, et al. (2008). The BTB-zinc finger transcriptional regulator PLZF controls the development of invariant natural killer T cell effector functions. Nat. Immunol 9, 1055–1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreslavsky T, Savage AK, Hobbs R, Gounari F, Bronson R, Pereira P, Pandolfi PP, Bendelac A, and von Boehmer H (2009). TCR-inducible PLZF transcription factor required for innate phenotype of a subset of gammadelta T cells with restricted TCR diversity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 12453–12458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurepa Z, Su J, and Forman J (2003). Memory phenotype of CD8+ T cells in MHC class Ia-deficient mice. J. Immunol 170, 5414–5420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labun K, Montague TG, Gagnon JA, Thyme SB, and Valen E (2016). CHOPCHOP v2: a web tool for the next generation of CRISPR genome engineering. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, W272–W276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebrón JA, Bennett MJ, Vaughn DE, Chirino AJ, Snow PM, Mintier GA, Feder JN, and Bjorkman PJ (1998). Crystal structure of the hemochromatosis protein HFE and characterization of its interaction with transferrin receptor. Cell 93, 111–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee N, Goodlett DR, Ishitani A, Marquardt H, and Geraghty DE (1998a). HLA-E surface expression depends on binding of TAP-dependent peptides derived from certain HLA class I signal sequences. J. Immunol 160, 4951–4960. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee N, Llano M, Carretero M, Ishitani A, Navarro F, López-Botet M, and Geraghty DE (1998b). HLA-E is a major ligand for the natural killer inhibitory receptor CD94/NKG2A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 5199–5204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan JL, Harrison OJ, Han SJ, Byrd AL, Vujkovic-Cvijin I, Villarino AV, Sen SK, Shaik J, Smelkinson M, Tamoutounour S, et al. (2018). Non-classical Immunity Controls Microbiota Impact on Skin Immunity and Tissue Repair. Cell 172, 784–796.e18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Xiong Y, Naidenko OV, Liu JH, Zhang R, Joachimiak A, Kronenberg M, Cheroutre H, Reinherz EL, and Wang JH (2003). The crystal structure of a TL/CD8alphaalpha complex at 2.1 A resolution: implications for modulation of T cell activation and memory. Immunity 18, 205–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo WF, Woods AS, DeCloux A, Cotter RJ, Metcalf ES, and Soloski MJ (2000). Molecular mimicry mediated by MHC class Ib molecules after infection with gram-negative pathogens. Nat. Med 6, 215–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzarino P, Pietra G, Vacca P, Falco M, Colau D, Coulie P, Moretta L, and Mingari MC (2005). Identification of effector-memory CMV-specific T lymphocytes that kill CMV-infected target cells in an HLA-E-restricted fashion. Eur. J. Immunol 35, 3240–3247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon CW, Zajac AJ, Jamieson AM, Corral L, Hammer GE, Ahmed R, and Raulet DH (2002). Viral and bacterial infections induce expression of multiple NK cell receptors in responding CD8(+) T cells. J. Immunol 169, 1444–1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montague TG, Cruz JM, Gagnon JA, Church GM, and Valen E (2014). CHOPCHOP: a CRISPR/Cas9 and TALEN web tool for genome editing. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, W401–W407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser JM, Gibbs J, Jensen PE, and Lukacher AE (2002). CD94-NKG2A receptors regulate antiviral CD8(+) T cell responses. Nat. Immunol 3, 189–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagarajan NA, Gonzalez F, and Shastri N (2012). Non-classical MHC class Ib-restricted cytotoxic T cells monitor antigen processing in the endoplasmic reticulum. Nat. Immunol 13, 579–586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtsuka M, Inoko H, Kulski JK, and Yoshimura S (2008). Major histocompatibility complex (Mhc) class Ib gene duplications, organization and expression patterns in mouse strain C57BL/6. BMC Genomics 9, 178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orange JS, Wang B, Terhorst C, and Biron CA (1995). Requirement for natural killer cell-produced interferon gamma in defense against murine cytomegalovirus infection and enhancement of this defense pathway by interleukin 12 administration. J. Exp. Med 182, 1045–1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérarnau B, Saron MF, Reina San Martin B, Bervas N, Ong H, Soloski MJ, Smith AG, Ure JM, Gairin JE, and Lemonnier FA (1999). Single H2Kb, H2Db and double H2KbDb knockout mice: peripheral CD8+ T cell repertoire and anti-lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus cytolytic responses. Eur. J. Immunol 29, 1243–1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietra G, Romagnani C, Mazzarino P, Falco M, Millo E, Moretta A, Moretta L, and Mingari MC (2003). HLA-E-restricted recognition of cytomegalovirus-derived peptides by human CD8+ cytolytic T lymphocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 10896–10901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polic B, Hengel H, Krmpotic A, Trgovcich J, Pavic I, Luccaronin P, Jonjic S, and Koszinowski UH (1998). Hierarchical and redundant lymphocyte subset control precludes cytomegalovirus replication during latent infection. J. Exp. Med 188, 1047–1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quatrini L, Wieduwild E, Escaliere B, Filtjens J, Chasson L, Laprie C, Vivier E, and Ugolini S (2018). Endogenous glucocorticoids control host resistance to viral infection through the tissue-specific regulation of PD-1 expression on NK cells. Nat. Immunol 19, 954–962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn M, Turula H, Tandon M, Deslouches B, Moghbeli T, and Snyder CM (2015). Memory T cells specific for murine cytomegalovirus re-emerge after multiple challenges and recapitulate immunity in various adoptive transfer scenarios. J. Immunol 194, 1726–1736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinnan GV Jr., Kirmani N, Rook AH, Manischewitz JF, Jackson L, Moreschi G, Santos GW, Saral R, and Burns WH (1982). Cytotoxic t cells in cytomegalovirus infection: HLA-restricted T-lymphocyte and non-T-lymphocyte cytotoxic responses correlate with recovery from cytomegalovirus infection in bone-marrow-transplant recipients. N. Engl. J. Med 307, 7–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahimpour A, Koay HF, Enders A, Clanchy R, Eckle SB, Meehan B, Chen Z, Whittle B, Liu L, Fairlie DP, et al. (2015). Identification of phenotypically and functionally heterogeneous mouse mucosal-associated invariant T cells using MR1 tetramers. J. Exp. Med 212, 1095–1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranasinghe S, Lamothe PA, Soghoian DZ, Kazer SW, Cole MB, Shalek AK, Yosef N, Jones RB, Donaghey F, Nwonu C, et al. (2016). Antiviral CD8+ T Cells Restricted by Human Leukocyte Antigen Class II Exist during Natural HIV Infection and Exhibit Clonal Expansion. Immunity 45, 917–930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapaport AS, Schriewer J, Gilfillan S, Hembrador E, Crump R, Plougastel BF, Wang Y, Le Friec G, Gao J, Cella M, et al. (2015). The Inhibitory Receptor NKG2A Sustains Virus-Specific CD8+ T Cells in Response to a Lethal Poxvirus Infection. Immunity 43, 1112–1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddehase MJ, Mutter W, Münch K, Bühring HJ, and Koszinowski UH (1987). CD8-positive T lymphocytes specific for murine cytomegalovirus immediate-early antigens mediate protective immunity. J. Virol 61, 3102–3108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romagnani C, Pietra G, Falco M, Mazzarino P, Moretta L, and Mingari MC (2004). HLA-E-restricted recognition of human cytomegalovirus by a subset of cytolytic T lymphocytes. Hum. Immunol 65, 437–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sell S, Dietz M, Schneider A, Holtappels R, Mach M, and Winkler TH (2015). Control of murine cytomegalovirus infection by γδ T cells. PLoS Pathog. 11, e1004481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang S, Siddiqui S, Bian Y, Zhao J, and Wang CR (2016). Nonclassical MHC Ib-restricted CD8+ T Cells Recognize Mycobacterium tuberculosis-Derived Protein Antigens and Contribute to Protection Against Infection. PLoS Pathog. 12, e1005688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith LM, McWhorter AR, Masters LL, Shellam GR, and Redwood AJ (2008). Laboratory strains of murine cytomegalovirus are genetically similar to but phenotypically distinct from wild strains of virus. J. Virol 82, 6689–6696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroynowski I, and Lindahl KF (1994). Antigen presentation by non-classical class I molecules. Curr. Opin. Immunol 6, 38–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson PA 2nd, Pack CD, Hadley A, Wang CR, Stroynowski I, Jensen PE, and Lukacher AE (2008). An MHC class Ib-restricted CD8 T cell response confers antiviral immunity. J. Exp. Med 205, 1647–1657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sylwester AW, Mitchell BL, Edgar JB, Taormina C, Pelte C, Ruchti F, Sleath PR, Grabstein KH, Hosken NA, Kern F, et al. (2005). Broadly targeted human cytomegalovirus-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells dominate the memory compartments of exposed subjects. J. Exp. Med 202, 673–685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabeta K, Georgel P, Janssen E, Du X, Hoebe K, Crozat K, Mudd S, Shamel L, Sovath S, Goode J, et al. (2004). Toll-like receptors 9 and 3 as essential components of innate immune defense against mouse cytomegalovirus infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 3516–3521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomasec P, Braud VM, Rickards C, Powell MB, McSharry BP, Gadola S, Cerundolo V, Borysiewicz LK, McMichael AJ, and Wilkinson GW (2000). Surface expression of HLA-E, an inhibitor of natural killer cells, enhanced by human cytomegalovirus gpUL40. Science 287, 1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyznik AJ, Tupin E, Nagarajan NA, Her MJ, Benedict CA, and Kronenberg M (2008). Cutting edge: the mechanism of invariant NKT cell responses to viral danger signals. J. Immunol 181, 4452–4456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulbrecht M, Martinozzi S, Grzeschik M, Hengel H, Ellwart JW, Pla M, and Weiss EH (2000). Cutting edge: the human cytomegalovirus UL40 gene product contains a ligand for HLA-E and prevents NK cell-mediated lysis. J. Immunol 164, 5019–5022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vance RE, Kraft JR, Altman JD, Jensen PE, and Raulet DH (1998). Mouse CD94/NKG2A is a natural killer cell receptor for the nonclassical major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I molecule Qa-1(b). J. Exp. Med 188, 1841–1848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vance RE, Jamieson AM, and Raulet DH (1999). Recognition of the class Ib molecule Qa-1(b) by putative activating receptors CD94/NKG2C and CD94/NKG2E on mouse natural killer cells. J. Exp. Med 190, 1801–1812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vance RE, Jamieson AM, Cado D, and Raulet DH (2002). Implications of CD94 deficiency and monoallelic NKG2A expression for natural killer cell development and repertoire formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 868–873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vugmeyster Y, Glas R, Pérarnau B, Lemonnier FA, Eisen H, and Ploegh H (1998). Major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I KbDb −/− deficient mice possess functional CD8+ T cells and natural killer cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 12492–12497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter EA, Greenberg PD, Gilbert MJ, Finch RJ, Watanabe KS, Thomas ED, and Riddell SR (1995). Reconstitution of cellular immunity against cytomegalovirus in recipients of allogeneic bone marrow by transfer of T-cell clones from the donor. N. Engl. J. Med 333, 1038–1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CR, Loveland BE, and Lindahl KF (1991). H-2M3 encodes the MHC class I molecule presenting the maternally transmitted antigen of the mouse. Cell 66, 335–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang EC, McSharry B, Retiere C, Tomasec P, Williams S, Borysiewicz LK, Braud VM, and Wilkinson GW (2002). UL40-mediated NK evasion during productive infection with human cytomegalovirus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 7570–7575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wesley JD, Robbins SH, Sidobre S, Kronenberg M, Terrizzi S, and Brossay L (2005). Cutting edge: IFN-gamma signaling to macrophages is required for optimal Valpha14i NK T/NK cell cross-talk. J. Immunol 174, 3864–3868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wesley JD, Tessmer MS, Chaukos D, and Brossay L (2008). NK cell-like behavior of Valpha14i NK T cells during MCMV infection. PLoS Pathog. 4, e1000106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson GW, Tomasec P, Stanton RJ, Armstrong M, Prod’homme V, Aicheler R, McSharry BP, Rickards CR, Cochrane D, Llewellyn-Lacey S, et al. (2008). Modulation of natural killer cells by human cytomegalovirus. J. Clin. Virol 41, 206–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]