SUMMARY

Presynaptic inhibition (PSI) of primary sensory neurons is implicated in controlling gain and acuity in sensory systems. Here, we define circuit mechanisms and functions of PSI of cutaneous somatosensory neuron inputs to the spinal cord. We observed that PSI can be evoked by different sensory neuron populations and mediated through at least two distinct dorsal horn circuit mechanisms. Low-threshold cutaneous afferents evoke a GABAA-receptor dependent form of PSI that inhibits similar afferent subtypes, whereas small-diameter afferents predominantly evoke an NMDA-receptor dependent form of PSI that inhibits large diameter fibers. Behaviorally, loss of either GABAARs or NMDARs in primary afferents leads to tactile hypersensitivity across skin types, while loss of GABAARs but not NMDARs leads to impaired texture discrimination. Post-weaning age loss of either GABAARs or NMDARs in somatosensory neurons causes systemic behavioral abnormalities, revealing critical roles of two distinct modes of PSI of somatosensory afferents in adolescence and throughout adulthood.

ETOC

Zimmerman et al. define distinct neurotransmitter and circuit mechanisms that gate the flow of tactile sensory information from the periphery into the spinal cord and characterize their roles in tactile sensitivity and behaviors

INTRODUCTION

Presynaptic inhibition (PSI) of synaptic inputs to early sensory processing areas of the central nervous system is believed to control gain, sharpen contrast, and filter irrelevant sensory cues in a context- and state-dependent manner. In the visual system, PSI of bipolar cell terminals contributes to center surround inhibition of ganglion cell receptive fields for enhanced visual contrast (Buldyrev and Taylor, 2013). In the olfactory system, PSI of primary sensory neuron input to the olfactory bulb controls temporal contrast, thus enabling pattern separation and odor discrimination and learning (Gödde et al., 2016; Raccuglia et al., 2016). In the somatosensory system, PSI of cutaneous sensory neuron inputs to the spinal cord may underlie general gain control and acuity (Eccles et al., 1963b; Frank and Fuortes, 1957; Rudomin and Schmidt, 1999), although its functions and mechanisms remain incompletely understood despite over 70 years of research.

The anatomical substrate of PSI of both cutaneous and proprioceptive afferents of the somatosensory system is believed to be inhibitory axoaxonic synapses that form upon sensory neuron terminals within the spinal cord and brainstem. In the spinal cord dorsal horn, the central projections of C- and Aδ-fiber cutaneous sensory afferents, and some Aβ afferents, terminate within complex synaptic structures termed glomeruli, where GABAergic axoaxonic as well as presumptive dendroaxonic synaptic inputs form onto them (Todd, 1996). Thus, dorsal horn GABAergic interneurons, whose activity may be controlled by descending modulatory- or sensory-evoked signals, release GABA to activate ionotropic GABA receptor chloride channels (GABAARs) present on primary sensory neuron terminals. Due to the high intracellular chloride concentration in primary sensory neurons, maintained by NKCC1 throughout development and into adulthood (Alvarez-Leefmans et al., 1988; Kanaka et al., 2001), activation of GABAARs on sensory neuron terminals leads to efflux of Cl- ions, which depolarizes the terminal. This process is termed primary afferent depolarization (PAD). Electrical stimulation of sensory afferents or supraspinal centers, or mechanical stimulation of the skin, can evoke PAD in a number of afferent subtypes (Andersen et al., 1962; Carpenter et al., 1963; Eccles et al., 1963b; Jänig et al., 1968; Jiménez et al., 1987), and GABAAR antagonists diminish low-threshold cutaneous and proprioceptive afferent-evoked PAD in the cat, rat, turtle, and mouse (Eccles et al., 1963a; Russo et al., 2000; Shreckengost et al., 2010). PAD underlies PSI by paradoxically reducing transmitter release from afferent terminals (Eccles et al., 1963b; Lidierth, 2006), which may involve one or more hypothesized mechanisms: 1) shunting inhibition, caused by Cl- efflux leading to diminished action potential (AP) height and thus transmitter release; 2) inactivation of voltagegated Na+ channels, thereby diminishing AP height and transmitter release; and 3) inactivation of voltage-gated Ca+ channels in terminals, reducing transmitter release (Rudomin and Schmidt, 1999). Experimentally, PAD can be measured in individual sensory neuron fibers or, more conveniently, with an extracellular recording electrode placed on the dorsal root and recording a dorsal root potential (DRP), which reflects back-propagating PAD in primary sensory neuron axons (Eccles et al., 1963b; Lidierth, 2006).

Although GABAAR activation is widely considered a crucial step leading to PSI of primary somatosensory neurons, several early studies reported incomplete block of sensory afferent- or supraspinal-evoked PAD by GABAAR antagonists, with some in vivo recordings implying that inhibition of GABAARs can enhance evoked DRPs (Benoist et al., 1972; Besson et al., 1971). Moreover, in vitro findings have suggested a role for presynaptic ionotropic glutamate receptors in inhibition of afferent transmission in the dorsal horn (Bardoni et al., 2004; Lee et al., 2002; Russo et al., 2000), and embryonic loss of NMDA receptors (NMDARs) in primary afferents leads to heat and mechanical hypersensitivity in adult mice (Pagadala et al., 2013). Both small and large diameter DRG neurons express GABAAR (Paul et al., 2012) and ionotropic glutamate receptor (Lee et al., 2002; Marvizón et al., 2002) subunits, and PAD can be elicited in both small and large caliber fibers (Whitehorn and Burgess, 1973). Yet earlier studies were limited in defining the sensory neuron subtypes that evoke PAD, circuit mechanisms governing activity-dependent PAD, and functions of PSI of cutaneous afferents in tactile behaviors.

Here, we used mouse genetic tools, optogenetics, electrophysiology, pharmacology, and behavioral approaches to probe the mechanisms and functions of PSI of cutaneous sensory neuron inputs to the dorsal horn. We found that, in addition to GABAARs present on the central terminals of both nociceptors and low-threshold mechanoreceptors (LTMRs), NMDARs also function presynaptically, on sensory neuron terminals in the dorsal horn, to control sensory inputs. While GABAAR-mediated PSI functions in a predominantly homotypic manner, NMDAR-mediated PSI is predominantly heterotypic. Furthermore, distinct populations of dorsal horn interneurons elicit these two forms of PSI. Disruption of either GABAAR- or NMDAR-dependent forms of PSI in adolescent mice, through selective ablation of genes encoding obligatory subunits of neurotransmitter receptors in primary somatosensory neurons, augments tactile sensitivity across multiple skin types. In contrast, loss of GABAARs, but not NMDARs, results in deficits in texture recognition. Interestingly, reducing either form of PSI leads to alterations in cognitive behaviors. Thus, two modes of PSI, which are evoked by different sensory neuron populations and mediated through distinct dorsal horn circuit mechanisms, collaborate in the control of mechanosensation and behavior.

RESULTS

Two mechanistically distinct forms of PSI of sensory input to the dorsal horn

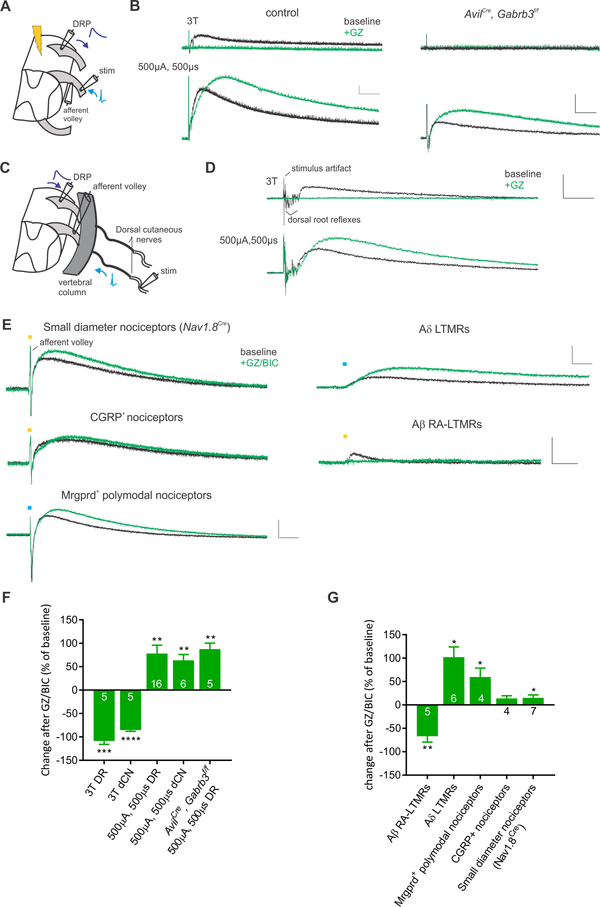

As a measure of PSI of sensory input to the spinal cord, we determined the extent of PAD using an ex vivo hemisected spinal cord preparation. By positioning a suction electrode on one dorsal root, a back-propagating wave of depolarization in sensory neuron axons, or DRP, was recorded following electrical stimulation of the adjacent dorsal root (DR, Figure 1A). This preparation allowed us to record afferent-evoked DRPs and restrict the site of action of applied drugs to the spinal cord. We also recorded from the DR proximal to the stimulation site to measure the minimum current necessary to evoke afferent volleys. Recordings were done in postnatal day 14–18 mice, an age by which inhibitory circuits in the spinal cord have matured to an adult-like state (Baccei and Fitzgerald, 2004), and when stimulating DRs at or below 3X threshold (3T; 7.5–24μA, 100μs) exclusively recruits A-fibers (Figure S1 and Torsney and MacDermott, 2006). Stimulating the lower thoracic DRs at 3T, we observed a low threshold-evoked DRP that was completely blocked by the GABAAR inhibitors gabazine (5–10μM) or bicuculline (10–20μM) (Figure 1B). Yet when the DR was stimulated at high stimulus intensity (500μA, 500μs), which recruits both A- and C-fibers, the evoked DRP was not blocked by GABAAR inhibitors, but was instead enhanced, likely due to disinhibited spinal circuits. To directly assess the role of GABAARs within sensory neurons for low-threshold afferent-evoked DRPs, we genetically eliminated GABAARs exclusively in somatosensory neurons by conditionally deleting GABRB3, an obligate GABAAR subunit for inhibitory transmission in these neurons (Nguyen and Nicoll, 2018; Orefice et al., 2016), using AvilCre; Gabrb3f/f mice. As predicted, the low threshold-evoked DRP was completely absent in AvilCre; Gabrb3f/f mice, however high intensity-evoked DRPs were present and, in fact, further enhanced by GABAAR antagonists (Figure 1B, F). No sex specific differences were observed in any DRP measurements (Figure S1A).

Figure 1. There are at least two mechanistically distinct forms of sensory neuron-evoked primary afferent depolarization (PAD).

A. Recording configuration for dorsal root (DR) or optogenetic stimulation. B. Effect of GABAAR antagonist gabazine (GZ, 10μM) on low threshold (≤3T) and high intensity (500μA, 500μs) DR evoked DRPs in control and AvilCre; Gabrb3f/f mice. Note the loss of low-threshold evoked DRPs in AvilCre; Gabrb3f/f mice. C. Recording configuration for dorsal cutaneous nerve stimulation. D. Similar to DR stimulation, GZ blocks 3T dorsal cutaneous nerve evoked DRP but enhances the high intensity electrical stimulation evoked DRP. E. Example traces of optogenetically evoked DRPs at baseline and in the presence of GABAAR antagonists GZ (5–10μM) or bicuculline (BIC, 10–20μM). Blue and yellow bars denote light pulse timing. The following crosses were used: Small diameter nociceptors (Nav1.8Cre; AvilFlpo; Rosa26LSL-FSF-ReaChR), CGRP nociceptors (AvilCre; CGRPFlpe; Rosa26LSL-FSF-ReaChR), Mrgprd+ polymodal nociceptors (MrgprdCre; Rosa26LSL-ChR2), Aδ-LTMRs (TrkBCreER; Rosa26LSL-ChR2), and Aβ RA-LTMRs (RetCreER; AvilFlpo; Rosa26LSL-FSF-ReaChR). F and G. Summary of the effects of GABAAR antagonists on electrically (F) and optogenetically evoked DRPs (G). All bar graphs in figures are represented as mean ± SEM. Asterisks above bar graphs denote statistical significance (**** p<.0001, *** p< .001, ** p<.01, * p<.05). Scale bars represent 0.05mV, 100ms.

In order to assess cutaneous sensory neuron evoked responses, the preparation was adapted to stimulate only the dorsal cutaneous nerve (Figure 1C), which exclusively innervates hairy skin. When the dorsal cutaneous nerve was stimulated at 3T, a gabazine-sensitive DRP was elicited (Figure 1D, F), similar to that observed following DR stimulation. Also similar to DR stimulation, when the dorsal cutaneous nerve was stimulated at high intensity, the evoked DRP was enhanced by gabazine. These results, together with previously published work (e.g. De Koninck and Henry, 1994; Shreckengost et al., 2010) suggest that GABAARs are integral to low-threshold cutaneous afferent evoked PAD, and are consistent with EM findings indicating that large caliber fibers receive axoaxonic GABAergic synaptic inputs (Todd, 1996). Moreover, these findings indicate that high intensity electrical stimulation of either the DR or dorsal cutaneous nerve recruits an additional, GABAAR-independent form of PAD.

We next asked which sensory neuron subtypes evoke GABAAR-dependent and GABAAR-independent modes of PSI. Since electrical stimulation of both the DR and the dorsal cutaneous nerve cumulatively activates Aα, Aβ, Aδ, and C-fiber sensory neuron fibers at increasing stimulus intensities, this mode of stimulation is insufficient to define the sensory neuron subtypes involved. Therefore, we used an optogenetic approach to selectively activate defined sensory neuron subsets while measuring light pulse-evoked DRPs. Using Nav1.8Cre; AvilFlpO (for small diameter DRG neurons), CGRPFlpe; AvilCre (CGRP+ peptidergic nociceptors), MrgdCre (Mrgprd+ polymodal nociceptors), TH2A-CreER; AvilFlpO (C-LTMRs), TrkBCreER (Aδ-LTMRs) or RetCreER; AvilFlpO (Aβ RA-LTMRs ) mice crossed with an appropriate Cre and/or FlpO recombinase dependent channelrhodopsin (Rosa26LSL-ChR2) or ReaChR (Rosa26LSL-FSF-ReaChR or Rosa26FSF-ReaChR) mouse line, we systematically tested whether optogenetic activation of select sensory neuron subtypes is sufficient to evoke a DRP, and if so, whether the DRP is dependent on GABAARs (Figure 1E,G). Strikingly, activation of all small diameter (Nav1.8+) DRG neurons, CGRP+ peptidergic nociceptors, Mrgprd+ polymodal nociceptors, or Aδ-LTMRs evoked a DRP that was largely independent of GABAARs. We were unable to evoke a DRP following optogenetic stimulation of C-LTMRs, even though optogenetically-evoked afferent volleys could be observed (data not shown). While there may be a recording bias of afferent types with extracellular suction electrodes leading to negative findings, C-LTMRs are numerous in the DRG (Li et al., 2011), suggesting that activity in this subtype of LTMR engages little PAD under these experimental conditions. In addition, whether any of these small and medium diameter subtypes are also able to evoke a GABAAR-dependent form of PAD is unclear, as the dominant GABAAR-independent form of PAD that is disinhibited by GABAAR antagonists would likely occlude this response. In contrast, optogenetic activation of Aβ RA-LTMRs, using RetCreER; AvilFlpO; Rosa26LSL-FSF-ReaCHR mice, elicited a DRP that was predominantly GABAAR-dependent (Figure 1E, G). Thus, Aβ-LTMRs evoke GABAAR-dependent PSI, whereas C-fiber sensory neuron subtypes and Aδ-LTMRs evoke a predominantly GABAAR-independent form of PSI.

Presynaptic NMDARs are present on LTMR terminals and mediate high threshold PAD

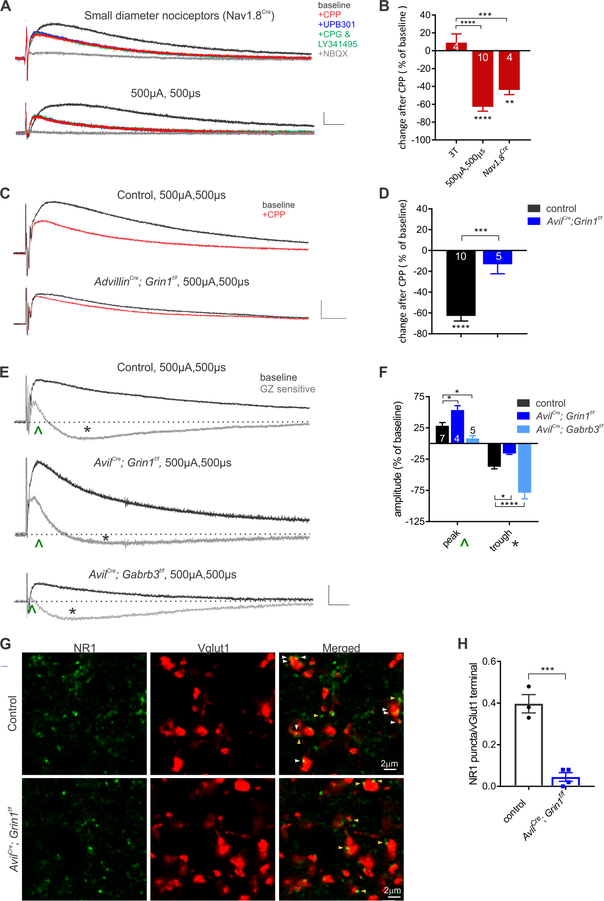

Because C-fiber sensory neuron subtypes and Aδ-LTMRs can evoke PSI through a non-canonical, GABAAR-independent mechanism, we next undertook a series of pharmacological experiments to define the receptor system involved. Nicotinic cholinergic receptor (nAChR) antagonists, glycine receptor antagonists, kainate receptor antagonists, metabotropic glutamate antagonists, and GABAB receptor antagonists all failed to diminish high threshold-evoked DRPs (Figure 2A, S1). In fact, both nAChR antagonists and glycine receptor antagonists modestly enhanced high-threshold-evoked DRPs (Figure S2), although the site of action underlying this facilitation is presently unclear. Conversely, the ionotropic NMDAR and AMPA receptor antagonists CPP and NBQX, respectively, diminished high threshold DRPs evoked either optogenetically, using Nav1.8Cre to express either ChR2 or ReaChR or electrically using high intensity DR stimulation (Figure 2A). Since both primary afferents and interneurons of spinal cord polysynaptic PSI circuits likely employ glutamatergic transmission, it was not possible to determine whether the glutamate receptor blockers acted directly on sensory neuron terminals to diminish PAD. Therefore, we turned to a gene ablation approach to determine whether NMDARs present on the central terminals of primary sensory neurons themselves are responsible for C-fiber- and Aδ-LTMR-evoked DRPs. For this, we used AvilCre; Grin1f/f mice to conditionally delete the obligatory NMDAR subunit NR1 exclusively in primary somatosensory neurons and performed DRP measurements. High threshold-evoked DRPs were diminished and, importantly, the CPP sensitivity of evoked responses was occluded in AvilCre; Grin1f/f mice (Figure 2C, S2). These findings indicate the NMDARs expressed in primary sensory neurons contribute to high threshold sensory neuron-evoked PAD.

Figure 2. Presynaptic NMDARs contribute to high threshold PAD.

A. Optogenetic activation of small diameter afferents (Nav1.8Cre; AvilFlpo; Rosa26LSL-FSF-ReaChR) and high intensity electrical stimulation of the dorsal root evoked DRPs in baseline conditions and with the sequential addition of an NMDAR antagonist (CPP, 20μM), kainate receptor antagonist (UPB301, 10μM), metabotropic glutamate receptor antagonists (MCPG, 50μM and LY341495, 50μM), and AMPA and kainate receptor antagonist (NBQX, 10μM). Only the combination of ionotropic glutamate receptor inhibitors blocks both types of DRP. B. Summary of the effects of CPP (20μM) on low threshold electrical, high intensity electrical and small diameter optogenetically evoked DRPs. Only the latter two types of evoked DRPs are inhibited by CPP (one-way ANOVA, F(2,13)=24.75, p<.0001). Asterisks denote Tukey’s post hoc test. C. Example of the effect of CPP on DRPs in control mice and AvilCre, Grin1f/f mutants. D. Summary of CPP-evoked changes on 500μA, 500μs evoked DRPs. Asterisks below bar graph denote statistical significance from baseline, asterisk above denotes two-tailed student’s t-test, p=.0003. E. Control and GZ subtracted traces of 500μA, 500μs dorsal root stimulation in control, AvilCre; Grin1f/f and AvilCre; Gabrb3f/f mutants. ^ denotes gabazine-sensitive peak, asterisk denotes gabazine-enhanced trough. F. Normalized GZ-sensitive peak and trough amplitude. Two-way ANOVA, genotype F(2,26)=30.61, p<.0001; component F(1,26)=206.6, p<.0001. Dunnett’s multiple comparison post hoc test comparing each mutant to control mice, denoted by asterisks. G. Immunohistochemistry of lamina III-IV for NR1 and myelinated afferent terminals marked by VGlut1. White arrows denote presynaptic NR1 puncta and yellow arrows denote postsynaptic NR1 puncta in control mice and AvilCre; Grin1f/f mutants. H. Average number of NR1 puncta per VGlut1 afferent terminal. Unpaired t-test, p=0.0005. (**** p<.0001, *** p< .001, ** p<.01, * p<.05)

The pharmacological and genetic deletion analyses suggested that GABAAR-dependent and NMDAR-dependent forms of PAD summate to form the high threshold-evoked DRP. In order to more clearly measure these two separate components, we defined the extent of GABAAR-sensitive PSI by subtracting DRP traces generated in the presence and absence of gabazine using AvilCre; Gabrb3f/f and AvilCre; Grin1f/f mice, which lack GABAARs or NMDARs in primary sensory neurons, respectively. High intensity electrical stimulation evoked an early onset, GABAAR-dependent DRP, and a later onset, longer lasting DRP that was not blocked but rather disinhibited by GABAAR antagonists. The early GABAAR dependent component was absent in AvilCre; Gabrb3f/f mutants while, in contrast, the longer latency GABAAR independent component was diminished in AvilCre; Grin1f/f mutants (Figure 2E, F). The identity of the receptor on sensory neuron terminals mediating the non-GABAergic PAD remaining in AvilCre; Grin1f/f mutants remains unknown, but our pharmacology experiments and related in vitro work (Lee et al., 2002) implicate presynaptic AMPA receptors.

Moreover, consistent with the notion that presynaptic NMDARs (preNMDARs) mediate GABAAR-independent PSI, immunohistochemical analysis of the NR1 subunit of NMDARs and VGlut1, expressed in large diameter sensory afferent terminals (Abraira et al., 2017), revealed that NMDARs are localized to ~40% of VGlut1+ terminals in the dorsal horn. Similar co-localization was observed between NR1 and sensory neuron terminal synapses, using AvilCre; Rosa26LSL-syntaptophysin-tdTomato reporter mice in which presynaptic boutons of DRG sensory neurons are labeled with tdTomato (Figure S3). These immunohistochemical measures indeed reflect NMDARs on sensory neuron terminals because co-localization of NR1 and VGlut1 was absent in AvilCre; Grin1f/f mutants, in which NR1 is eliminated in sensory neurons but not in the spinal cord (Figure 2G, H). In addition, in situ hybridization experiments confirmed the presence of NMDAR transcripts in both large and small diameter DRG sensory neurons (Figure S3). These findings are consistent with prior work showing that preNMDARs are localized to primary afferent terminals in the rat spinal cord by EM (Liu et al., 1994), and NMDA application to the isolated spinal cord induces a Mg-sensitive DRP and reduces DR-evoked AMPAR currents in the dorsal horn (Bardoni et al., 2004). Taken together, our findings indicate that NMDARs are localized to primary sensory neuron terminals where they contribute to C- and Aδ-fiber-evoked PSI. Thus, there exists at least two mechanistically distinct forms of PSI of sensory input to the dorsal horn: a GABAAR-mediated form evoked by Aβ-LTMRs, and a NMDAR-mediated form that is evoked by peptidergic and non-peptidergic C-fiber sensory neuron subtypes and Aδ-LTMRs.

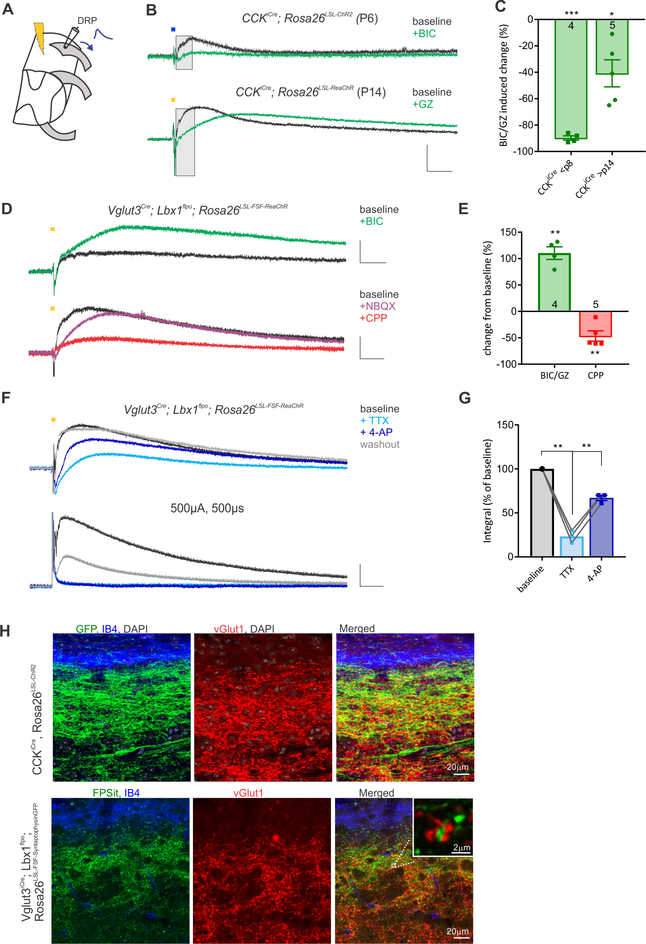

GABAAR-dependent PAD and NMDA-R-dependent PAD are activated by different excitatory interneurons of the dorsal horn

Since distinct sensory neuron subtypes promote either GABAAR- or NMDAR-dependent PSI, we next tested the idea that different populations of dorsal horn interneurons are involved. In our previous work (Abraira et al., 2017) we identified CCKiCre-labeled interneurons as a large excitatory population comprising ~30% of interneurons within the LTMR recipient zone of the dorsal horn. Interestingly, selective activation of CCKicre-labeled interneurons using optogenetic stimulation of CCKiCre; Lbx1Flpo; Rosa26LSL-FSF-ReaCHR or CCKiCre; Rosa26LSL-ChR2 mice (Figure 3A) evoked a strong DRP, and this was largely abolished by GABAAR antagonists when recorded in young (<P8) mice (Figure 3B, C). When CCKicre-labeled interneuron-evoked DRPs were examined in P14-P18 mice (the same age recorded for experiments in Figures 1 and 2), GABAAR antagonists selectively diminished the early DRP (Figure 3B, C), suggesting that CCKiCre-labeled excitatory interneurons include those that engage GABAAR-dependent PSI, likely through a GABAergic interneuron intermediate. We also assessed the involvement of transient VGlut3+ excitatory interneurons of the dorsal horn, which are implicated in mechanical allodynia (Peirs et al., 2015). VGlut3+ interneuron terminals span the more ventral nociceptive and entire LTMR recipient zone, and these excitatory interneurons receive inputs from both small and large diameter afferents (Figure 3H; Peirs et al., 2015). While a portion of transient VGlut3+ interneurons overlap with CCKiCre-labeled interneurons (Figure S4), selective activation of transient VGlut3+ interneurons, by optogenetic stimulation of the DR entry zone of VGlut3cre; Lbx1Flpo; Rosa26LSL-FSF-ReaChR mice, evoked a strong DRP that was entirely independent of GABAARs, but partially dependent on NMDARs (Figure 3D, E). Thus, as with Aβ-LTMRs and C-fibers/Aδ-LTMRs, a subset of CCKicre-labeled interneurons and transient VGlut3+ interneurons engage distinct modes of PAD to mediate PSI in the dorsal horn.

Figure 3. GABAAR PAD and NMDA-R PAD are engaged by different populations of dorsal horn excitatory interneurons.

A. Recording configuration denoting light stimulation of the dorsal root entry zone. B. CCKiCre-labeled interneuron induced DRPs in neonatal or juvenile mice are completely or partially blocked by GABAAR antagonists, respectively. Shaded region demarcates area under the DRP calculated in C. C. Composite data, integrating the area under the filtered DRP up to its peak in both neonatal and juvenile mice. Asterisks denote statistical significance from no effect. D. Transient VGlut3+ interneuron (labeled using VGlut3Cre, Lbx1Flpo mice) activated DRPs depend on ionotropic glutamate receptors, particularly NMDARs, and are enhanced by GABAAR antagonists. E. Composite data, integrating area under the full filtered DRP for each antagonist. F. Application of tetrodotoxin (TTX, 1uM) greatly diminishes the transient VGlut3+ interneuron optogenetically evoked DRP, which is partially recovered by the addition of 600 μM 4-AP. Electrically evoked DRPs were completely blocked by TTX and could not be recovered with the addition of 4-AP (400μM-1mM). G. Composite data of the effect of TTX (1 μM) and 4-AP (400–600μM) on optogenetically evoked DRPs. One-way ANOVA, F(1.241,2.482)=307.2, p=.0011. Asterisks denote Tukey’s multiple comparison post hoc test. Physiology scale bars denote 0.05mV, 100ms. H. Immunohistochemistry of transient VGlut3+ interneurons and CCKiCre labeled interneurons. Upper: Sagittal sections from CCKiCre; Rosa26LSL-ChR2 mouse counterstained for IB4 and VGlut1; Lower: Sagittal sections from VGlut3Cre; Lbx1Flpo; Rosa26LSL-FSF-Synaptohpysin-GFP mouse counterstained for VGlut1 and IB4. Inset is high magnification of close proximity of transient VGlut3 interneuron terminals to VGlut1 presumptive afferent terminals. (*** p< .001, ** p<.01, * p<.05).

Since AMPA-R antagonists had little effect on the transient VGlut3+ interneuron-evoked DRP (Figure 3D), we next asked whether this mode of interneuron-evoked DRP is due to direct actions onto afferent terminals. While tetrodotoxin (TTX, 1μM) dramatically reduced VGlut3 interneuron-evoked DRPs, and it eliminated the high intensity DR stimulation-evoked DRP in these mice, as expected for a polysynaptic circuit, the addition of the K+ channel blocker 4aminopyridine (4-AP) rescued only the light-evoked DRP (Figure 3F,G). Distinct from most optogenetic-assisted circuit mapping analyses, light-evoked DRPs partially remained in the presence of TTX alone, suggesting some light-evoked transmitter release, and at a high dose of 4-AP (1mM) light-evoked DRPs often exceeded baseline values (data not shown). These findings suggest either monosynaptic input from transient VGlut3+ interneurons onto sensory neuron terminals or, since the vast majority of axoaxonic and a majority of presumptive dendroaxonic synapses in dorsal horn glomeruli are GABAergic (Todd, 1996), perhaps more likely, an extrasynaptic mode of action. Consistent with both of these possibilities, labeled synaptic terminals of transient VGlut3+ interneurons using VGlut3cre; Lbx1Flpo; Rosa26LSL-FSF-synaptophysin-GFP mice (Niederkofler et al., 2016) were observed throughout the LTMR-recipient zone, often in close proximity to VGlut1+ terminals of sensory neurons (Figure 3H). Whether synaptic or extrasynaptic, activation of the transient VGlut3+ interneurons evokes PAD in a manner that does not appear to depend on an additional, intermediate dorsal horn interneuron. Taken together, these findings support the existence of a glutamatergic form of PSI mediated by the transient VGlut3+ interneurons of the dorsal horn.

GABAARs and NMDARs in primary somatosensory neurons differentially control cutaneous tactile sensitivity and acuity

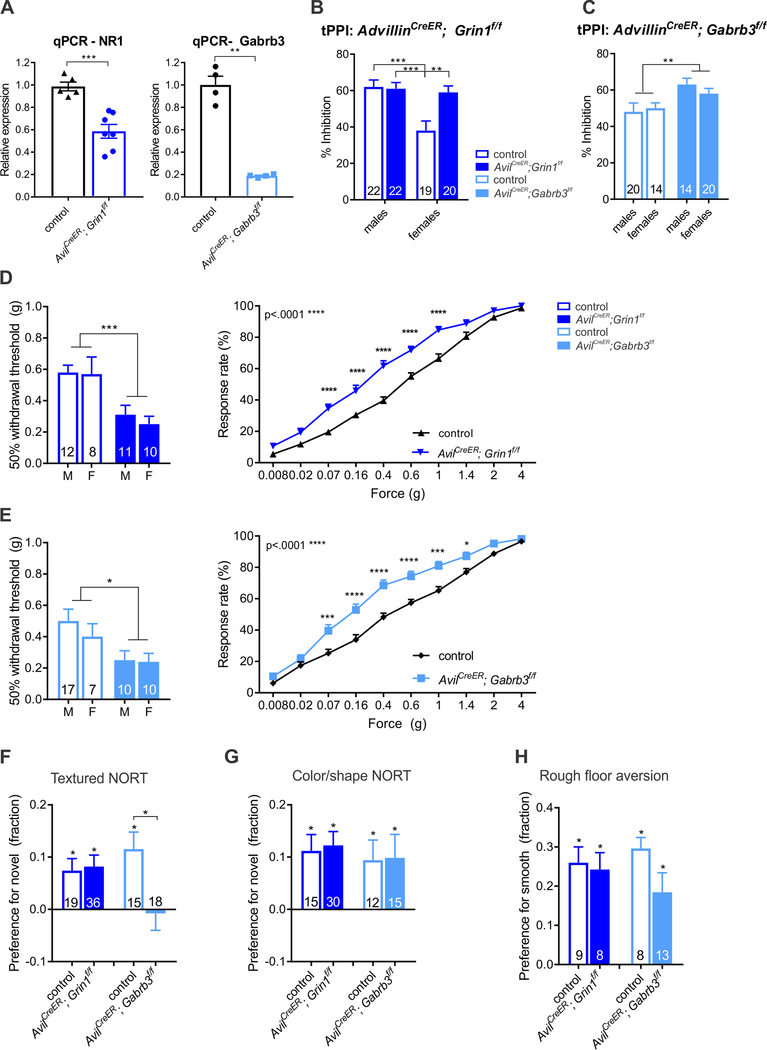

Our observations reveal the existence of at least two distinct receptor mechanisms and dorsal horn circuit motifs controlling PSI of sensory neuron terminals. Therefore, we next sought to define the roles of these two modes of PSI in behavioral responses to natural cutaneous stimuli. To avoid compensation and non-cell autonomous effects from developmental disruption of NMDAR- and GABAAR-mediated transmission, we conditionally ablated either Gabrb3 or Grin1 in somatosensory neurons of post-weaning mice using the conditional Gabrb3 and Grin1 alleles and the somatosensory neuron selective, tamoxifen-sensitive allele AvilCreER (Lau et al., 2011). Thus, AvilCreER; Gabrb3f/f mice and AvilCreER; Grin1f/f mice and their Cre-negative control littermates were treated with tamoxifen (1mg/day) for five consecutive days, beginning at P28. This treatment regimen achieved ~80% reduction of Gabrb3 mRNA and ~40% reduction of Grin1 mRNA in DRGs of experimental mice (Figure 4A), reflecting a reduction but not elimination of these obligate receptor subunits and likely results in an underestimation of the requirement of these receptors. Male and female control and experimental mice were subjected to a battery of behavioral tests at 8–11 weeks of age, with experimenters blind to genotype. As a measure of hairy skin tactile sensitivity, we used a tactile prepulse inhibition assay (tPPI), where an acoustic startle stimulus is preceded by a light air puff delivered to the back hairy skin of animals with varying inter-stimulus intervals (Orefice et al., 2016). For this assay, the more sensitive a mouse is to the air puff, the more the air puff prepulse attenuates the acoustic startle response (i.e. increased PPI). We observed that female, but not male, AvilCreER; Grin1f/f mice and, as predicted from previous work (Orefice et al., 2016), both female and male AvilCreER; Gabrb3f/f mice exhibit enhanced tPPI compared to controls, indicative of hairy skin hypersensitivity (Figure 4B, C).

Figure 4. GABAARs and NMDA-Rs are both required in adult somatosensory afferents for normal tactile sensitivity.

A. qPCR of mRNA knockdown in both AvilCreER conditional knockout models. Unpaired two-tailed student’s t-test with Welch’s correction, p=0.0003 for Grin1 and p=.0018 for Gabrb3. B. tPPI, 50ms ISI, AvilCreER; Grin1f/f. Two-way ANOVA: interaction F(1,79)=7.437, p=.0079; sex F(1,79)=10.39, p=.0018; genotype F(1, 79)=6.146, p=.0153. Tukey’s multiple comparisons test denoted by asterisks. C. tPPI, 50ms ISI, AvilCreER; Gabrb3f/f. Two-way ANOVA, asterisks denote main effect of genotype (F(1,64)=8.618, p=.0046), no main effect of sex or interaction. D and E. Von Frey thresholds and response rates for AvilCreER; Grin1f/f (D) and AvilCreER; Gabrb3f/f (E). Two-way ANOVA of threshold, main effect of genotype denoted by asterisks. AvilCreER; Grin1f/f: F(1,37)=16.05, p=0.0003; AvilCreER; Gabrb3f/f: F(1,40)=6.937, p=0.0119. For response rates, a two-way repeated measures ANOVA was performed, main effect of genotype noted by the p-value in the upper left and asterisks denoting Sidak multiple comparisons post hoc test. No main effect of sex or interaction for either genotype. F-H. Textured NORT (F), shape NORT (G), and rough floor aversion tests (H) for both Grin1f/f and Gabrb3f/f crosses. Asterisks above bar graphs denote preference significantly different than zero. Unpaired two-tailed student’s t-test per cross, p=.0122 for AvilCreER; Gabrb3f/f mice textured NORT. (**** p<.0001, *** p< .001, ** p<.01, * p<.05)

Both AvilCreER; Grin1f/f and AvilCreER; Gabrb3f/f mice also exhibited glabrous skin hypersensitivity, as assessed using von Frey filament stimulation of hindpaw glabrous skin. Thresholds and response rates to filament stimulation were abnormal in the conditional knockouts, and no difference between males and females was observed (Figure 4D, E). When estrus checking female mice for other behavioral measures not included in this study, we noticed an additional potential tactile sensitivity phenotype; many mice exhibited vigorous responses following contact with the genital skin area. We therefore generated a genital skin sensitivity scale (see Supplemental videos and Methods). AvilCreER; Grin1f/f females, but not AvilCreER; Gabrb3f/f females, showed markedly increased sensitivity to contact with the genital skin area, compared to controls (Figure S6A). AvilCreER; Grin1f/f mice, but not AvilCreER; Gabrb3f/f mice, also exhibited a mild hypersensitivity to heat pain, as assessed using the Hargreaves test (Figure S6B, C). In contrast to a prior study (McRoberts et al., 2011), hyposensitivity to inflammatory pain was not observed in either AvilCreER; Grin1f/f or Nav1.8Cre; Grin1f/f male mice (Figure S6D, E). Other pain and temperature assays were not assessed, reflecting an interesting future direction.

PSI is implicated in lateral inhibition, which in other sensory systems contributes to spatial and temporal acuity (Buldyrev and Taylor, 2013; Gödde et al., 2016; Raccuglia et al., 2016).

Therefore, we also assessed texture discrimination in controls and mutant mice using a textured novel object recognition task (textured NORT, Orefice et al., 2016). In this behavioral paradigm, control mice typically spend more time exploring a novel block compared to a familiar block. Two versions of NORT were done; one in which blocks differ in texture but are identical in shape and color (textured NORT), and a control NORT in which blocks differ in shape and color but have the same texture (color/shape NORT). As we previously observed with heterozygous AvilCreER; Gabrb3f/+mice (Orefice et al., 2016), homozygous AvilCreER; Gabrb3f/f mutant mice did not exhibit preference for novel textured objects, although they did show normal novelty preference for objects that differ in shape and color (Figure 4F,G). These findings confirm that GABAARs in somatosensory neurons are crucial for texture discrimination. In contrast, AvilCreER; Grin1f/f mice exhibited a similar preference for textured objects to controls (Figure 4F). Thus, NMDARs in sensory neurons are dispensable for this behavior. Finally, both AvilCreER; Grin1f/f mice and AvilCreER; Gabrb3f/f mice exhibited aversion to rough textured floors, comparable to their littermate controls (Figure 4H), indicating that avoidance of an aversive texture is not dependent on either mode of PSI.

While it is likely that more dramatic behavioral phenotypes would be observed with a more complete gene deletion in somatosensory neurons, these findings indicate that loss of either NMDARs or GABAARs in primary afferents causes hypersensitivity across trunk hairy skin and hindpaw glabrous skin, while loss of NMDARs but not GABAARs in sensory neurons causes genital skin hypersensitivity and modest temperature hypersensitivity. Moreover, consistent with a role for PSI of Aβ-LTMRs in tactile acuity, a reduction of GABAARs but not NMDARs in sensory neurons leads to deficits in fine texture discrimination.

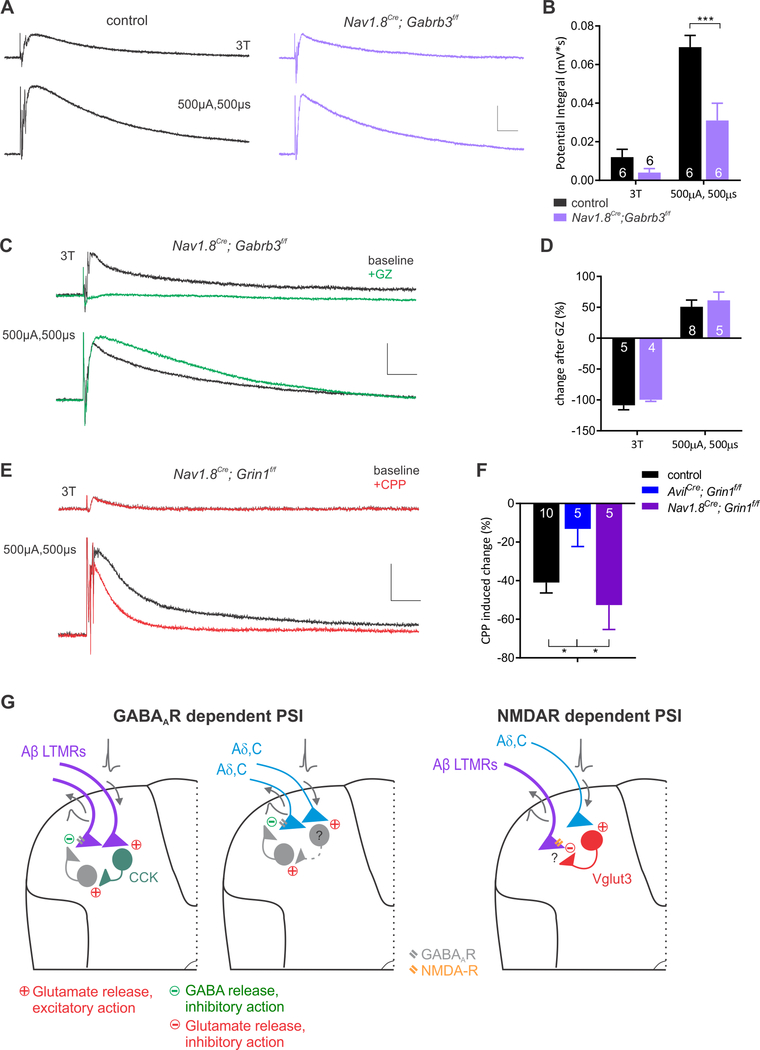

Presynaptic GABAARs and NMDARs both function in large diameter sensory neurons for sensory neuron-evoked PSI

The finding that two mechanistically distinct forms of PSI differentially contribute to cutaneous tactile sensitivity and acuity raises the question of which classes of sensory neurons each form of PSI modulates. To address this, we used the ex vivo DRP recording preparation and mice harboring the Nav1.8Cre allele and the Gabrb3 and Grin1 conditional alleles to abolish either GABAAR- or NMDAR-mediated PSI exclusively in small-to-medium diameter sensory neurons, which are labeled with Nav1.8Cre. We found that high intensity electrical stimulation-evoked DRPs were diminished in magnitude in Nav1.8Cre; Gabrb3f/f mice, whereas low threshold-evoked DRPs were unaffected in these mutants (Figure 5A, B). Moreover, both low threshold- and high intensity-evoked DRPs exhibited similar sensitivity to gabazine in Nav1.8Cre; Gabrb3f/f and control mice (Figure 5C, D). These findings indicate that activation of purely large diameter sensory neurons (with 3T DR stimulation), including Aβ-LTMRs, promotes GABAAR-mediated PSI predominantly of large diameter sensory neuron inputs to the dorsal horn (i.e. those not labeled with Nav1.8Cre). In contrast, high intensity electrical stimulation of afferents promotes at least two forms of PSI, including GABAAR-mediated PSI of small-to-medium diameter afferents. To test whether the latter reflects small diameter afferent-evoked inhibition of other small diameter afferents, we selectively activated small diameter fibers while simultaneously silencing GABAARs in the same afferents (with Nav1.8Cre; Gabrb3f/f; Rosa26LSL-ReaChR mice). We found that the light activated DRP was diminished in Nav1.8Cre; Gabrb3f/f; Rosa26LSL-ReaChR mice when compared to light activated control (Nav1.8Cre; Rosa26LSL-ReaChR) mice, with similar gabazine sensitivity (Figure S5). Thus, while the dominant form of PAD evoked by small diameter afferents is GABAAR-independent (Figure 1), a coinciding weaker form of PAD is evoked by small diameter afferents and induces GABAAR-dependent PAD of other small diameter afferents.

Figure 5. GABAARs mediate PSI of both large diameter and small diameter sensory neurons, whereas NMDARs mediate PSI predominantly in large diameter neurons.

A. Sample traces of same-day-recorded littermate control and Nav1.8Cre; Gabrb3f/f mutant DRPs. B. Composite data of DRP integrals, two-way ANOVA: interaction of stimulus intensity and genotype, F(1,20)=6.461, p=0.0194. Asterisks denote Sidak’s multiple comparisons test, compared within each stimulus intensity. C. Example traces from Nav1.8Cre; Gabrb3f/f mutant DRPs evoked by stimulating an adjacent dorsal root at stimulus intensity noted, and with the addition of 10μM gabazine (GZ). D. Composite data of GZ sensitivity. Control and Nav1.8Cre; Gabrb3f/f mutant mice have bidirectional GZ modulation of evoked DRPs (two-way ANOVA, no main effect of genotype or interaction with stimulus intensity). E. Example traces from Nav1.8Cre, Grin1f/f mutant DRPs evoked by dorsal root stimulation using the stimulation intensities noted, and with the addition of CPP. Note marked CPP-induced reduction of the high intensity DRP remains. F. Composite data comparing control, Nav1.8Cre; Grin1f/f, and AvilCre; Grin1f/f mice (repeated from Figure 2). One-way ANOVA: F(2,12)=5.228, p=.0233. Asterisks below bars denote Dunnett’s multiple comparison post hoc test. All scalebars denote 0.05mV, 100ms. G. Diagrams of three afferent activity-dependent modes of PSI. Left most spinal cord dorsal horn represents GABAAR dependent PSI of large diameter cutaneous afferents. Activity in Aβ-LTMRs can lead to activation of a subset of CCKiCre-labeled excitatory interneurons, which in turn activate GABAergic interneurons and induce GABAAR-dependent PAD in predominantly other Aβ subtypes. Middle spinal cord represents GABAAR-dependent PSI of small diameter afferents, induced by activity in small diameter afferents. Currently unidentified interneuron(s) are colored grey. The right spinal cord dorsal horn represents NMDAR-dependent PSI, whereby activity in C and Aδ afferents predominantly inhibits Aβ LTMRs through transient VGlut3+ excitatory interneurons. The anatomical substrate of this form of PSI is unknown but does not require additional synapses.

In related experiments, NR1 was deleted in small diameter afferents using Nav1.8Cre; Grin1f/f mice, and the pharmacological sensitivity of evoked DRPs in these mice were compared to those observed in control mice and AvilCre; Grin1f/f mice, which lack NMDARs in all primary sensory neurons. Interestingly, CPP application attenuated the high threshold-evoked DRPs in Nav1.8Cre; Grin1f/f mice to an extent comparable to that observed in control mice; this attenuation of CCP-sensitivity was not observed in pan-DRG Grin1 knockout mice (Figure 5E, F). This indicates a minimal contribution of NMDARs on small diameter afferents to sensory neuron-evoked PAD. Together with the results shown in Figure 1, these findings indicate that NMDAR-dependent PAD is evoked exclusively by small-to-medium caliber afferents and expressed mainly in large diameter afferents, which are not labeled with Nav1.8Cre. These findings support a model in which presynaptic GABAARs (preGABAARs) predominantly mediate homotypic (Aβ->Aβ, C/Aδ->C/Aδ) PSI, whereas preNMDARs primarily mediate heterotypic (C/Aδ->Aβ) PSI of cutaneous afferents (Figure 5G).

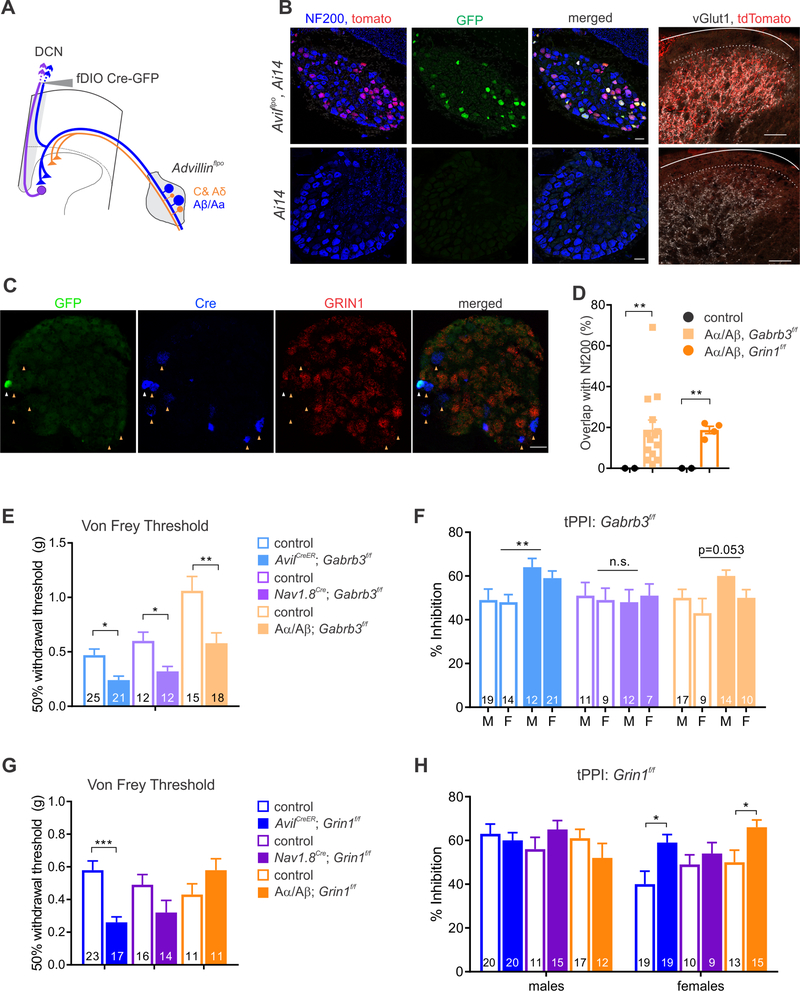

NMDARs on DCN-projecting Aβ-LTMRs regulate hairy skin sensitivity, while GABAARs on both small-to-medium diameter neurons and DCN-projecting Aβ-LTMRs affect glabrous skin sensitivity

Our physiological findings indicate that both GABAARs and NMDARs function within presynaptic terminals of large diameter neurons, while GABAARs also function in C/Aδ afferents, to mediate sensory-evoked PSI. Therefore, we asked whether deletion of GABAARs or NMDARs in either large or small/medium diameter sensory neuron subtypes recapitulates any of the tactile hypersensitivity phenotypes observed in the pan-DRG Gabrb3 and Grin1 mutant mice. To delete Gabrb3 or Grin1 exclusively in small and medium diameter afferents, we again used Nav1.8Cre; Gabrb3f/f and Nav1.8Cre; Grin1f/f mice. To delete Gabrb3 or Grin1 in large diameter neurons, including Aβ-LTMRs, but not in small and medium diameter DRG neurons, we took advantage of the fact that only Aβ/Aα afferents project via the dorsal column to the dorsal column nuclei (DCN) of the brainstem (Bai et al., 2015). Thus, we injected a FlpO-dependent Cre adeno-associated virus (AAV2/9-fDIO-Cre-GFP, Penzo et al., 2015) into the rostral dorsal column of AvilFlpO mice to direct Cre-dependent recombination exclusively in DCN-projecting afferents (Figure 6A). This labeling strategy was tested using AvilFlpO; Rosa26LSL-tdTtomato (Ai14) mice. Indeed, tdTomato expression was observed in ~26% of NF200+ caudal thoracic DRG neurons, with GFP labeling ~50% of these neurons, whereas neither tdTomato nor GFP labeling was observed in neurons lacking NF200 or in Ai14 control mice (Figure 6B). Moreover, tdTomato+ terminals were observed exclusively within the VGlut1+ LTMR recipient zone of the spinal cord, indicating transduction of large but not small diameter sensory neuron subtypes by this approach. In addition, no somatic labeling of the spinal cord was observed in these mice. Next, the efficiency of NR1 deletion in fDIO-Cre-GFP virus-injected AvilFlpO; Grin1f/f mice was assessed using RNAscope. In both GFP+/Cre+ and Cre+-only neurons, NR1 expression was undetectable (Figure 6C). This approach thus ablates genes in a large subset of DCN-projecting sensory neurons, which includes Aβ-LTMR subtypes, but not in Aδ-LTMRs, C-fiber sensory neuron subtypes or spinal cord neurons.

Figure 6. NMDAR-mediated PAD of Aα/Aβ afferents underlies hairy skin hypersensitivity, while GABAAR-mediated PAD of both C-/Aδ-afferents and Aα/Aβ afferents underlies glabrous skin hypersensitivity.

A. Diagram of viral strategy to conditionally delete receptors only in DCN projecting A-fibers. B. Characterization of viral strategy of AAV2/9-fDIO-CreGFP in AvilFlpO; Rosa26LSL-tdTomato mice and control (Rosa26LSL-tdTomato) mice in DRG and spinal cord dorsal horn (right most panels). GFP expression and Cre driven tdTomato expression was observed only in NF200+ neurons in the DRG of AvilFlpO mice. Scalebars denote 20μm for DRG and 50μm for spinal cord. C. RNAscope for Cre and Grin1 expression in AvilFlpO; Grin1f/f mice and immunohistochemistry for GFP expression. White arrowhead denotes Cre+/GFP+ soma, yellow arrowheads note Cre+/GFP- cells. D. Labeling efficiency of virus injected mice previously run on behavioral assays. E. 50% withdrawal threshold for Von Frey test for Gabrb3f/f crosses. Two-way ANOVA was run separately on each cross; asterisks denote main effect of genotype. Nav1.8Cre; Gabrb3f/f main effect of genotype: F(1,26)=6.136, p=.0201; AvilFlpO; Gabrb3/f main effect of genotype: F(1,36)=8.506, p=.0061. F. tPPI with 50ms ISI for all three Gabrb3f/f crosses, M labels male data, F labels female data. No significant effects of sex or interactions between sex and genotype for any cross. G. Von Frey thresholds for Grin1f/f crosses, asterisks denote main effect of genotype. H. tPPI with 50ms ISI for all three Grin1f/f crosses. Two-way ANOVA interaction between sex and genotype for AvilFlpO; Grin1f/f mutants, F(1,61)=6.244, p=.0132. For each cross, Sidak’s multiple comparison post hoc test was performed within each sex and denoted with asterisks. AvilCreER; Gabrb3f/f and AvilCreER; Grin1f/f data are replotted from data in Figure 4. (*** p< .001, ** p<.01, * p<.05)

We next injected AAV2/9-fDIO-Cre-GFP into the rostral dorsal column of AvilFlpO; Grin1f/f and AvilFlpO; Gabrb3f/f mice, and their control littermates at p28, and used these mice along with Nav1.8Cre; Grin1f/f and Nav1.8Cre; Gabrb3f/f mice and their control littermates for tactile sensitivity behavioral measurements at 8–10 weeks of age. In a subset of mice, the efficiency of viral transduction was assessed by measuring the extent of GFP and NF200 co-localization using immunohistochemistry (IHC) following completion of behavioral analyses. This IHC analysis confirmed efficient and selective transduction in AvilFlpO mice but not control mice (Figure 6D). Using this paradigm, we observed hypersensitivity to von Frey filaments applied to the hindpaw in both Nav1.8Cre; Gabrb3f/f mutants and the AvilFlpO; Gabrb3f/f mutants injected with AAV2/9fDIO-Cre-GFP in the DCN (Figure 6E). These findings of glabrous skin hypersensitivity are consistent with the physiological findings implicating GABAARs in PSI of both Aβ afferents and C/Aδ neurons. Conversely, when GABAARs were deleted exclusively in Aβ/Αα afferents, hairy skin hypersensitivity was not observed, although there was a trend in that direction (Figure 6F); this negative finding may reflect incomplete deletion using the dorsal column nuclei viral ablation paradigm (Figure 6D). Consistent with this possibility, tPPI was unperturbed in Nav1.8Cre; Gabrb3f/f mice. Thus, GABAARs in both Aβ-fiber and C/Aδ-fiber subtypes modulate glabrous skin sensitivity, while GABAARs in large diameter afferents, afferents unlabeled by either strategy, or a combination of subtypes, modulate hairy skin sensitivity.

In contrast, neither Nav1.8Cre; Grin1f/f mice nor AvilFlpO; Grin1f/f mice injected with AAV2/9fDIO-Cre-GFP into the rostral dorsal column recapitulated the glabrous skin hypersensitivity to von Frey stimulation observed in mice lacking Grin1 in all DRG neurons (Figure 6G). However, deletion of NMDARs in DCN-projecting Aβ/Aα afferents led to a similar female specific hairy skin tactile hypersensitivity phenotype as observed in AvilCreER; Grin1f/f mice (Figure 6H). This suggests that preNMDARs function in DCN-projecting Aβ-LTMRs to control hairy skin sensitivity in female mice.

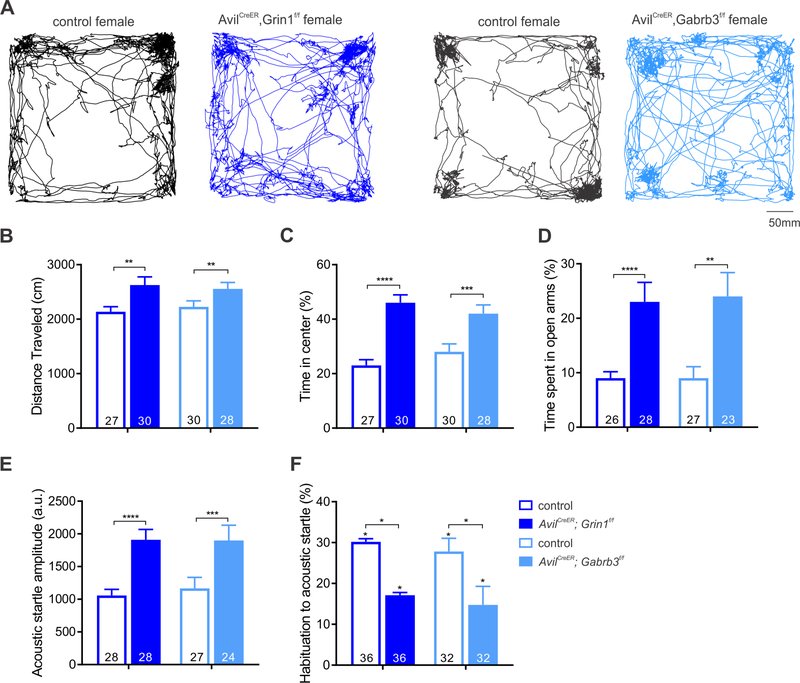

Loss of GABAAR and NMDAR-mediated PSI in young adult mice results in changes in anxiety-like and exploratory behaviors.

Since post-weaning age loss of NMDARs and GABAARs in somatosensory neurons leads to tactile hypersensitivity, and our previous findings demonstrated that impaired tactile information processing and reactivity during development contribute to anxiety and social interaction abnormalities in adult mice (Orefice et al., 2016), the consequences of adolescent (P28) disruption of the receptor systems underlying PSI on complex behaviors were next tested. 2–3 month old AvilCreER; Grin1f/f and AvilCreER; Gabrb3f/f mice and their littermate controls (which received tamoxifen treatments starting at P28) were subjected to open field and elevated plus maze tests, and their startle amplitude and habituation to startle assessed from acoustic PPI trial data. Overall, both sets of mutants had similar behavioral abnormalities, distinct from their control littermates. Both AvilCreER; Grin1f/f and AvilCreER; Gabrb3f/f mutant mice exhibited hyper-locomotion during the open field test, covering greater distances (Figure 7A, B). Similarly, AvilCreER; Grin1f/f and AvilCreER; Gabrb3f/f mice exhibited increased exploratory behavior, spending more time in the center of the open field chamber (Figure 7A, C), and displaying less aversion to the open arms of the elevated plus maze (Figure 7D), with female mutants showing a more severe phenotype (Figure S7). Both AvilCreER; Grin1f/f and AvilCreER; Gabrb3f/f mice also exhibited an increased acoustic startle reflex and decreased short-term habituation to acoustic startle (Figure 7E, F). Moreover, 2–3 month old Grin1 mutants exhibited aggressive behavior, including fratricide (data not shown). Unexpectedly, both AvilCreER; Grin1f/f and AvilCreER; Gabrb3f/f mice exhibited alterations in acoustic PPI (Figure S7), with deficits in AvilCreER; Grin1f/f mice being more pronounced. As spiral ganglion afferents are not labeled by AvilCreER P28 tamoxifen treatment (data not shown), this phenotype may suggest cross-sensory modality compensation for aberrant tactile filtering. Together, these findings indicate that alterations of the receptor systems underlying both modes of PSI in adolescent mice leads to general, overt changes in exploratory and anxiety-like behaviors in the adult.

Figure 7. Loss of GABAARs and NMDARs in somatosensory neurons leads to anxiety-like and exploratory behavioral alterations.

A. Sample open field traces of AvilCreER; Grin1f/f and AvilCreER; Gabrb3f/f female mice and their littermate controls. B-F. Composite data of behavioral paradigms, asterisks and statistics denote two-way ANOVA main effect of genotype, data shown are pooled across sex. B. Distance traveled during open field; AvilCreER; Grin1f/f: F(1,54)=8.943, p=.0042; and AvilCreER; Gabrb3f/f: F(1,54)=10.36, p=.0022. C. Time in center of open field, AvilCreER; Grin1f/f: F(1,54)=42.34, p<0.0001; AvilCreER; Gabrb3f/f: F(1,54)=13.49, p=0.0006. D. Elevated plus maze, AvilCreER; Grin1f/f F(1,50)=20.53, p<0.0001; AvilCreER; Gabrb3f/f: F(1,51)=11.14, p=0.0016. E. Acoustic startle reflex, AvilCreER; Grin1f/f: F(1,74)=27.85, p<0.0001; and AvilCreER; Gabrb3f/f: F(1,64)=13.15, p=0.0006. F. Short term habituation to acoustic startle, asterisks above bars denote statistically significant habituation. Two-way ANOVA main effect of genotype of AvilCreER; Grin1f/f: F(1,55)=4.366, p=.0413; AvilCreER; Gabrb3f/f: F(1,60)=4.856, p=0.0314.

DISCUSSION

Here we report that the spinal cord dorsal horn contains at least two distinguishable circuit motifs governing presynaptic inhibition of somatosensory afferents. These two PSI circuits are driven by different sensory neuron inputs, they are comprised of distinct dorsal horn excitatory interneuron populations, and they engage distinct receptor mechanisms on select afferent fiber subtype endings in the dorsal horn. The two modes of PSI play similar roles in some tactile behaviors, yet differential roles in others, thus providing insight into the scope of behavioral influence of peripherally and centrally driven PSI of cutaneous afferents. Moreover, changes in exploratory and anxiety-like behaviors resulting from loss of somatosensory neuron GABAARs and NMDARs implicate both modes of PSI of somatosensory afferents as essential for general mouse behavior and late-stage cognitive development.

Different somatosensory neuron subtypes and dorsal horn circuits underlie two distinct modes of PSI

Our findings reveal the presence of both homotypic, GABAAR-dependent and predominantly heterotypic, NMDAR-dependent modes of PSI of afferent input to the dorsal horn. The homotypic nature of GABAAR-dependent PSI is consistent with prior work suggesting that, for proprioceptors and glabrous skin-innervating Aβ-LTMRs (Jänig et al., 1968), activity in one afferent type recruits GABAergic inhibition preferentially of similar or the same afferent types. In addition, our finding that activation of a subset of CCKicre-labeled dorsal horn excitatory interneurons can recruit this GABAAR-dependent form of PAD is consistent with a tri-synaptic circuit motif activated or modulated by both afferent inputs and descending projections from cortex and brainstem. Moreover, our behavioral and physiological findings are consistent with the idea that a GABAAR-dependent form of PSI also engages small diameter afferents in a homotypic manner, yet the interneuron(s) involved in this form of PAD are currently unidentified. Additional studies assessing the necessity and sufficiency of the dorsal horn interneurons that mediate each form of PAD are warranted.

In contrast to GABAAR-dependent PSI, NMDAR-dependent PSI is uniquely activated by small and medium caliber afferents, including Aδ-LTMRs, and acts predominantly on large caliber afferents, including Aβ-LTMRs. The transient VGlut3+ population of dorsal horn interneurons, which play a role in mechanical allodynia after nerve injury or inflammation (Peirs et al., 2015), appears to directly engage somatosensory afferents to activate NMDAR-dependent PSI. It is interesting that GABAAR antagonists enhance or “disinhibit” NMDAR-dependent PSI, especially in light of prior work implicating decreased dorsal horn GABAergic tone and GABAAR-dependent PSI in mechanical allodynia in rodent inflammatory and neuropathic pain models (Malan et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2008). These findings together may suggest the existence of cross-talk between spinal GABAergic inhibition and the NMDAR-dependent form of PSI, leading us to speculate that an altered balance of inhibitory mechanisms may contribute to the genesis and/or maintenance of mechanical allodynia associated with chronic pain states.

Functions of PSI in mechanosensation and behavior

P28 deletion of Grin1 and Gabrb3 (present study) mimics hypersensitivity characterized with embryonic deletion of these subunits (Orefice et al., 2016; Pagadala et al., 2013), indicating critical roles of these receptors in regulating mechanosensation in adult mice. Moreover, while our findings implicate GABAAR- and NMDAR-mediated PSI in controlling tactile sensitivity in overlapping but distinct skin regions, only GABAAR-mediated PSI is implicated in texture discrimination. These findings are consistent with a general, modulatory role of both GABAAR- and NMDAR-mediated PSI in controlling gain in the tactile sensory system, and a unique, obligatory role for GABAAR-dependent PSI in texture discrimination. An appealing explanation for this difference is that GABAAR-dependent PSI underlies lateral inhibition of glabrous skin-innervating Aβ-LTMR terminals, thus providing a substrate for controlling acuity.

Our findings also implicate preNMDARs in DCN-projecting Aβ/Aα afferents for controlling hairy skin sensitivity, and preGABAARs in both DCN-projecting Aβ/Aα afferents and small caliber afferents for controlling glabrous skin sensitivity. Since the DCN viral knockout strategy used to ablate receptor genes is incomplete and variable (Figure 6H), and probably spares receptors expressed in at least some hairy-skin Aβ SAI-LTMRs of lumbar DRGs (Bai et al., 2015), our approach almost assuredly underestimates the roles of preGABAARs and preNMDARs in Aβ-LTMRs in the behavioral measures reported. Likewise, while both forms of PSI are clearly diminished in DRG conditional knockouts, the incomplete reductions may reflect preferential loss in some afferent subtypes and likely leads to an underestimation of the roles of these presynaptic receptors. It is also possible NMDARs and/or GABAARs have a peripheral locus of action (e.g. Iwashita et al., 2012) that may contribute to the behavioral phenotypes observed, or that centrally-evoked PSI contributes to other sensory functions not assessed using of our battery of behavioral tests, such as thermal preference, cold, and itch sensation.

An additional consideration pertains to the origin of centrally-evoked PSI, either supraspinally or spinally driven, and whether it engages GABAAR-mediated PSI, NMDAR-mediated PSI, or both. Interestingly, afferent-evoked DRPs remain fully sensitive to NMDAR antagonists when small caliber afferents are devoid of Grin1 (Figure 5), indicating that NMDARs contribute minimally, if at all, to sensory neuron-evoked PAD of small-to-medium diameter sensory neuron subtypes. Yet most, if not all, DRG sensory neurons express Grin1 mRNA (Figure S2, Yang Zheng and DDG unpublished), and electrophysiological and EM evidence supports the conclusion that NMDARs are broadly expressed in DRG neurons (Li et al., 2004; Liu et al., 1994). Thus, while our findings indicate that sensory neuron-evoked NMDAR-dependent PSI plays a minor role in controlling glutamate release from nociceptors under normal conditions, it is possible that preNMDARs on C/Aδ fiber afferents contribute to centrally-evoked PSI. PreNMDARs may also function in nociceptors under pathological conditions because they are upregulated in rat models of neuropathic pain and opiate tolerance, where they may function by enhancing glutamate release from nociceptors instead of inhibiting it (Xisheng et al., 2013; Zeng et al., 2006).

A notable outcome of the present study is that manipulations that diminish PSI of somatosensory afferents in adolescent mice, beginning at P28 and causing tactile hypersensitivity, lead to changes in exploratory and anxiety-like behaviors in 8–11 week old mice. These phenotypes contrast with those seen when Gabrb3 was deleted embryonically, and they also differ from heterozygous conditional Gabrb3 deletion (AvilCreER; Gabrb3f/+ mutants) beginning at P28 (Orefice et al., 2016). Indeed, when Gabrb3 was deleted in all sensory neurons during embryonic development, marked decreases in exploration, and no change in startle amplitude or aPPI, were observed, and P28 heterozygous deletion of Gabrb3 did not lead to changes in these behavioral measures. These findings, taken together, provide additional support for the existence of a developmental switch in the dependency of PSI and tactile sensitivity for overt mouse behaviors (Orefice et al., 2016). It is also intriguing that the combined phenotypes of hyper-locomotion, decreased aPPI, and increased acoustic startle reflex, shown here for post-weaning age homozygous deletions of both Gabrb3 and Grin1, have also been noted in mouse models of systemic NR1 hypofunction (Duncan et al., 2004), human mutations implicated in autism and schizophrenia (Didriksen et al., 2017), and adolescent social isolation models in rodents (Fone and Porkess, 2008). We thus propose that two mechanistically and functionally distinct modes of PSI of sensory inputs to the dorsal horn collaborate to control gain and discriminatory capabilities of the somatosensory system, deficiencies of which compromise an animal’s perception of, and interaction with, the outside world.

STAR METHODS

CONTACT FOR REAGENT AND RESOURCE SHARING

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to the Lead Contact, David Ginty (david_ginty@hms.harvard.edu)

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Animals

Mice for behavior were ear notched and tail biopsied at p21 and weaned at p25. All behavioral experiments were completed between 8–11 weeks of age. Mice for electrophysiology were toe tagged at postnatal day 5–7 and used at postnatal day 14–18. In every behavioral and physiology experiment where mutants were compared to control mice, the experimenter was blinded to genotype. All experiments were in accordance with Harvard Medical School IACUC guidelines. The following mouse lines were used in electrophysiology and behavioral experiments:

Grin1f/f mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratory (RRID:IMSR_JAX:005246) and were previously described (Tsien et al., 1996). Gabrb3f/f mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratory (RRID:IMSR_JAX:008310) and were previously described (Ferguson et al., 2007). Mice were generated by crossing a double heterozygous (Cre/+, f/+) male to homozygous conditional females. Cre negative littermates were used as controls. The following Cre and flp lines were used for conditional knockout strategies: AvilCre (Hasegawa et al., 2007), AvilCreER (RRID:IMSR_JAX:026516, (Lau et al., 2011)), Nav1.8Cre (Stirling et al., 2005), and AvilFlpO (to be characterized elsewhere, T. Dickendesher and DDG, unpublished). Tamoxifen was dissolved in sunflower oil (10mg/mL) and stored at −20 in 1mL aliquots, and administered to AvilCreER; Grin1f/f and AvilCreER; Gabrb3f/f mice and their control littermates by intraperitoneal injections for 1 mg per day for 5 days. Grin1f/f and Gabrb3f/f mice used for behavioral experiments were on mixed genetic backgrounds (C57Bl6/CD1 for Grin1 and Sv129/C57Bl6 for Gabrb3).

For optogenetic physiology experiments, the following Cre and Flp lines were used: Nav1.8Cre (Stirling et al., 2005), TrkBCreER (tamoxifen treated at p7 or p8, 0.5mg (Rutlin et al., 2014); CGRPFlpe (to be characterized in a subsequent paper); RetCreER (tamoxifen treated 2.5mg at e10.5, (Luo et al., 2009)); TH2A-CreER (tamoxifen treated at p8 or p10, 0.5mg, RRID:IMSR_JAX:025614 (Abraira et al., 2017), MrgdCre (Rau et al., 2009), VGlut3iCre (Jackson laboratory, RRID:IMSR_JAX:018147 (Grimes et al., 2011)), Lbx1Flpo (Duan et al., 2014), CCKiCre (Jackson Laboratory, RRID:IMSR_JAX:012706 (Abraira et al., 2017)). Conditional optogenetic lines: Rosa26LSL-ChR2 (Ai32, RRID:IMSR_JAX:012569); Rosa26LSL-FSF-ReaChR; Rosa26FSF-ReaChR (RRID:IMSR_JAX:024846 (Hooks et al., 2015)).

METHOD DETAILS

Electrophysiology

In vitro DRP measurements were completed as described previously (Orefice et al., 2016). Postnatal day 14–18 mice of both sexes were anesthetized with isofluorane, transcardiacally perfused with ice cold high Mg++, low Ca++ ACSF containing: 128mM NaCl, 1.9mM KCl, 1.2mM KH2PO4, 26mM NaHCO3, 0.85mM CaCl2, 6.5mM MgSO4, and 10mM d-glucose (pH of 7.4) prior to decapitation and vertebral column removal. The vertebral column was placed in a circulating, oxygenated bath of high Mg, low Ca ACSF, and a ventral verbrectomy and laminectomy was performed. An off-centered sagittal hemisection (adjacent to the dorsal column) was performed with insect pins, then the preparation was inverted and dorsal laminectomy completed. The isolated cord was secured with insect pins in a sylgard covered dish, and dura around the spinal cord and roots removed to allow suction electrode access. The superfusate was then switched to recording ACSF (128mM NaCl, 1.9mM KCl, 1.2mM KH2PO4, 26mM NaHCO3, 2.4mM CaCl2, 1.3mM MgSO4, and 10mM D-glucose) circulating (3–5mL/minute).

A L1-T10 dorsal root was stimulated, with a recording suction electrode placed proximally on the same root to record afferent volleys. An additional suction electrode was placed on the rostral adjacent dorsal root close to its site of entry into the spinal cord. Stimulus threshold was determined by gradually increasing stimulus intensity until an afferent volley was detected in at least 50% of the sweeps (typically 3–6μA; stimulus duration 100μs). DRPs were recorded at 2T, 3T, and at 500μA, 500μs for maximal activation, for a total of 10 sweeps each, with 10 seconds between sweeps for 2T and 3T and 30 seconds between sweeps for 500μA, 500μs.

For dorsal cutaneous nerve activation, the preparation was similar as above, but back hairy skin was shaved prior to perfusion and removed with the vertebral column. After ventral vertebrectomy, laminectomy, and hemisection were completed, back hairy skin was pinned down and cut along the midline, minimizing disruption of the main branches of the dorsal cutaneous nerves. The right side of the vertebral column and associated dorsal cutaneous nerves were kept intact during the dorsal vertebrectomy, and fascia partially removed from the dorsal cutaneous nerves to allow a stimulating suction electrode access. Afferent volleys were recorded in the corresponding dorsal root, and DRPs from the rostrally located adjacent root. All ventral roots were cut to remove motor signals to the intercostal muscles.

DC recordings were acquired using an AC/DC differential amplifier and mini headstage (A-M systems, Model 3000), a Digidata 1440A acquisition system, and pClamp10 software (Molecular Devices), using a 10kHz sampling rate. A custom-built MATLAB program was used to subtract the baseline values prior to the stimulus, average 10 sweeps at each intensity, low-pass filter the response at 100 Hz, find the onset of the evoked DRP, its peak amplitude, the integral under the filtered response from onset peak and from peak to offset (defined as the time at which the slow potential decayed to 20% of peak amplitude, with a 1s hard time cap). When comparing integral changes with the addition of drug, parameters were constrained to baseline values. Traces shown are average of 10 sweeps and low-pass filtered at 1 kHz. Stimulus artifact and occasionally large afferent volleys were truncated manually offline for visualization purposes.

To activate ChR2 or ReaChR in the isolated spinal cord, whole field illumination was applied through a 10× objective centered over the dorsal root entry zone. Afferent terminals or interneurons were stimulated with blue or yellow light (473 and 555nm, 30–50mW at the level of the spinal cord, respectively, for 10ms). When comparing baseline values for conditional knockout mice, mutants and their littermate controls lacking Cre were recorded on the same day when possible or on adjacent days, with the experimenter blinded to genotype.

For any drug treatment experiments, stable recordings were obtained for at least 15 minutes before adding drug, and when possible without DC fluctuations in resting potential, washout recordings obtained. The following drugs were added to the circulating ACSF of known volume to make the noted final concentration: SR95531 (gabazine, 5–10μM, Sigma-Aldrich, S106), bicuculline (10–20μM, Tocris, 0130), strychnine (1μM, Sigma Aldrich, S0532), NBQX (10μM, Fisher Scientific, 037310), CNQX (10μM, Sigma-Aldrich, C127), CPP (20μM, Fisher Scientific 017310), UBP301 (10μM, Tocris, 1766), tetrodotoxin citrate (TTX, 1μM, Tocris, 1069), 4aminopyridine (4-AP, 400μM-1mM, Tocris, 0940), tubocurarine chloride pentahydrate (20μM, Sigma Aldrich, 93750), mecamyline hydrochloride (50μm, Sigma-Aldrich, M9020), SCH 50911 (10μM, Tocris, 0984), LY341495 disodium salt (100μM, Tocris, 4062), and (RS)-MCPG disodium salt (100μM, Tocris, 3696).

For gabazine subtraction experiments (Figure 2E), average traces of 10 sweeps from 500μA, 500μs stimulation were low-pass filtered at 100Hz and drug induced traces subtracted from baseline traces. Peak time, peak amplitude, trough time, and trough amplitude were determined using PClamp and expressed as a % of baseline amplitude.

For recruitment threshold comparisons, within the same two week period, spinal cords and dorsal roots were isolated from P14-P18 mice or 4–6 month Cre negative behavior mice treated with tamoxifen. A sacral root was stimulated distally and recorded at the DR entry zone in the presence of ionotropic glutamate receptor antagonists CPP and NBQX. This recording configuration allowed at least 3.5mm from stimulation to recording site in order to clearly distinguish slower conducting afferent volleys.

Tissue Fixation and Immunohistochemistry

Male and female mice 6–52 weeks old and their age and sex matched littermate controls were anesthetized with isofluorane and perfused with 5–10mL modified Ames Media in 1× PBS, followed by 0.5mL/g of 2% PFA (for NR1 or GABRB3 IHC) or 4% PFA (for all other IHC experiments), with no postfix. Brains, spinal cords, and DRGs were dissected out and kept in PBS at 4°C. For long-term storage, tissue was stored in PBS + 0.01% sodium azide.

Tissue for vibratome sectioning (only used in the Vglut3Cre; Lbx1Flpo, Rosa26LSL-FSF-synaptophysin-GFP and CCKiCre, Rosa26LSL-ChR2 crosses) was mounted on 4% agar in desired orientation and covered with 2% agar to hold it in place. 60μm sagittal sections of spinal cord were made on the vibratome, placed in wells filled with 1× PBS, and stored at 4°C.

Sagittal sections were processed for free floating immunohistochemistry as described previously (Abraira et al., 2017). Tissue sections were incubated in 50% ethanol in ddH2O for 30 minutes to improve antibody penetration, then washed in high salt 1× PBS (1× PBS with 0.3M NaCl, HSPBS) 3×10 minutes. Sections were then incubated with primary antibodies diluted in HS-PBS with 0.3% Triton X-100 (HS-PBST) for 48–72 hours at 4°C. Sections were washed in HS-PBST 3×10 minutes, and then incubated with secondary antibodies diluted in HS-PBST overnight at 4°C. Sections were washed in HS-PBST 3×10 minutes, and then mounted on glass slides and coverslipped with Fluoromount Aqueous Mounting Medium (Sigma). The slides were stored at 4°C.

Tissue for frozen sectioning (all other genetic crosses) was cryoprotected in 30% sucrose in 1× PBS overnight at 4°C, embedded in OCT and frozen in tissue molds over a dry ice and ethanol slurry, then stored at −80°C until sectioning. 20μm transverse sections of thoracic spinal cord and DRGs were made on a cryostat, with littermate controls and mutants on the same slides, and stored at −80°C until staining.

Sections were defrosted for 1 hour at room temperature, then rehydrated for 3×10 min in 1× PBS. Slides were blocked for 1–2 hours in 1× PBS containing 0.1% Triton-X 100 and 5% normal serum (Vector Labs S-1000). Sections were incubated with primary antibodies diluted in blocking solution (5% donkey or goat serum, no detergent) overnight at 4°C. Slides were washed 4×5 minutes in 1× PBS containing 0.02% Tween 20 (PBSt) and then incubated with species specific secondary antibodies in blocking solution for 1 hour at room temperature. Tissue was washed with PBSt 2×5 minutes, then treated with 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) stain at a 1:5000 dilution for ten minutes, then washed again with PBSt for 2×5 minutes. Tissue sections were then mounted on glass slides and coverslipped with Fluoromount Aqueous Mounting Medium (Sigma). The slides were stored at 4°C.

For GABRB3 staining and NR1 staining age comparisons, a modified high salt protocol was used on frozen 20 μm sections. Sections were defrosted for 5–12 hours at room temperature, then rehydrated for 3×10 min in 1× PBS. Tissue sections were incubated in 50% ethanol in ddH2O for 30 minutes to improve antibody penetration, then washed in HS-PBS for 3×10 minutes. Sections were then incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes in HS-PBS, then for 15 min in 0.001% trypsin + 0.001% CaCl2 at 37°C. Slides were washed in HS-PBS 3× 10 minutes. Sections were incubated with primary antibodies diluted in HS-PBST for 48 hours at 4°C. After 48 hours, sections were incubated with primary antibodies for 30 minutes at room temperature. Sections were then washed in HS-PBST 6×10 minutes, and then incubated with secondary antibodies diluted in HSPBST for 2 hours at room temperature. Sections were washed in HS-PBST 3×10 minutes, and then mounted on glass slides with Fluoromount Aqueous Mounting Medium (Sigma). The slides were stored at 4°C.

The following primary antibodies and concentrations were used: guinea pig anti-VGlut1 (Millipore AB5905, 1:1000, RRID:AB_2301751); mouse anti-NR1 (Millipore MAB 363, 1:500, RRID:AB_94946), chicken anti-GFP (Aves, GFP-1020, 1:1000, RRID:AB_10000240), IB4–647 (LifeTech I32450, 1:500), rabbit anti-NF200 (Sigma N4142, 1:1000, RRID:AB_477272). A rabbit polyclonal antibody to GABRB3 was raised against the full-length protein, with the signal peptide and transmembrane domains deleted. The final sequence represented residues 26–245, 328–450 of mouse GABRB3 (Biomatik, Ontario, Canada, 1:500). An array of goat derived Alexa Fluor 488,546, and 647 secondaries conjugated IgGs (Invitrogen) were used.

RT-qPCR

Male and female mice 11–29 weeks old and their age and sex matched littermate Grin1f/+ or Gabrb3f/+ controls were sacrificed by asphyxiation followed by cervical dislocation and decapitation. Dissections were kept to less than 25 minutes from time of death and occurred on a lab bench that had been thoroughly cleaned with 70% ethanol and ELIMINase (VWR). DRGs were dissected out and placed immediately into RNAlater solution (Invitrogen) on ice. DRGs in RNAlater solution were stored at 4°C.

To extract RNA, DRGs were removed from RNAlater solution and placed into 300uL of TRIzol (Thermo Fisher). DRGs were disrupted in TRIzol using a motorized hand-held pestle and homogenized with a 31-gauge needle.

Direct-zol Microprep Purification Column (Zymo Research) was used to extract RNA from homogenized samples, with a DNase I treatment step on-column. Extracted RNA samples were stored at −80°C. Reverse transcription was completed with the SuperScript IV VILO Master Mix after treatment with ezDNase enzyme (Thermo Fisher), using 100ng of RNA per sample.

Samples were assayed using SsoAdvanced Universal SYBR Green Supermix and run on a CT1000 Thermal Cycler with CFX96 Real-Time System (BioRad). cDNA was diluted by a factor of 10, and 5μL of sample cDNA was used per 20μL reaction. Cycle conditions were: 95°C for 30 seconds, then 40 cycles of 95°C for 10 seconds and 60°C for 30 seconds, ending with a melt curve analysis ranging from 65°C to 95°C with 5 second steps of 0.5°C increments. All reactions were run in triplicate, with individual wells excluded from analysis if they differed beyond +/− 0.2 quantification cycles (Cq) from the remaining two wells. RNA expression levels were determined from the mean values, and were standardized to expression of the housekeeping gene glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). Data shown is normalized to average values from control mice. The following primer pairs were used: GAPDH (forward): ACCCTGTTGCTGTAGCCGTATCA and (reverse): TCAACAGCAACTCCCACTCTCCA; GABRB3 (forward): GCCAGCATCGACATGGTTTC and (reverse): GCGGATCATGCGGTTTTTCA; NR1 (forward): CCTGGAAGCAAAATGTGTCCC and (reverse): AGATCCCAGCTACGATGCCT.

RNAscope

Male and female mice 13–41 weeks old and their age and sex matched littermate controls were sacrificed by asphyxiation followed by cervical dislocation and decapitation. Dissections were kept to less than 25 minutes from time of death and occurred on a sterilized lab bench that had been thoroughly cleaned with 70% ethanol and ELIMINase (VWR). Thoracic DRGs and spinal cords were dissected out and placed into a cryomold filled with OCT, which was then placed in a dry-ice cooled methyl-butane bath until frozen. Frozen samples were stored in airtight containers at −80°C.

RNAscope staining was completed following the RNAscope Fluorescent Multiplex Assay (ACD Bio). The following probes were used: Mm-Grin1-O2-C3 (ACDBio, 474011-C3), Mm-Nefh (ACDBio, 443671), Mm-Mrgprd-C2 (ACDBio, 417921-C2), Cre (ACDBio, 312281), MmSLc17a8 (ACDBio, 431261), and EGFP-C2 (ACDBio, 400281-C2). For combination with immunohistochemistry, the above protocol was run through until the hybridization of Amp 4-FL. After washing to remove Amp 4-FL, immunohistochemistry was completed following the protocol outlined above before counterstaining with DAPI.

Image analysis

Z stack images for puncta analysis were obtained on the Zeiss LSM7000 confocal microscope with the 63× objective. Images were taken in lamina III-IV, within 150μm of lamina IIiv (using IB4 labeling to demarcate boundary). The depth of the z-stack was determined by the expanse of VGlut1+ terminals. Imaging parameters were held constant for NR1/GABRB3 across all animals. NR1 and GABRB3 puncta analysis was performed using a custom script in ImageJ over 0.9 μm thick images, creating a mask of VGlut1+ terminals ≥ 0.5 μm in diameter, thresholding NR1/GABRB3, and counting puncta of at least 0.1μm in diameter contained within that mask. 34 animals of each genotype or age were used, with at least 1000 VGlut1 terminals per animal.

For CCKiCre; Rosa26LSL-ChR2 mouse RNAscope analysis, Z stack images were obtained on the Zeiss LSM7000 confocal microscope with the 20× objective. Imaging parameters were held constant for all samples, with a minimum of 6 dorsal horn images per animal. Images were analyzed by hand using the threshold of 5 distinct puncta within a DAPI positive cell to consider the cell positive for expression of the probe RNA.

Dorsal Column Injections

Male and female mice P28-P30 were anesthetized by isofluorane inhalation (1.5–2.5%). Breathing rate and anesthesia were continuously monitored and isofluorane level adjusted as necessary. The back of the neck was shaved and then swabbed with betadine and 70% ethanol. A 5mm incision was made in the skin, and 0.5% lidocaine was applied to the incision site and underlying muscle. Muscles were separated or cut to expose the cervical vertebral column. The dura and arachnoid membranes between C1 and C2 were cut to expose the spinal cord. Four 75nL injections of AAV2/9-fDIO-Cre-GFP virus (Boston Children’s viral core; 1.16492E+13gc/ml) mixed with a nominal volume of fast green were made bilaterally into the dorsal column under visual guidance with a glass pipette. Injections were assessed by determining the extent to which the dorsal column took up the tracer, and an additional injection site was added when inefficient uptake noted. Muscle and skin were then stitched together with sutures, and carprofen (4mg/kg) was injected intraperitoneally for analgesia. Mice were returned to their home cage after recovery from anesthesia, and additional doses of carprofen were given twice daily for 48 hours post-surgery. The condition of the mice was monitored daily for 1 week following surgery, and weekly thereafter. Mice were used 4 weeks later for behavior or tissue processing.

Behavioral Assays

All mice were group housed with same-sex littermates with a 12-hour light/dark cycle and free access to food and water. Cages were changed once per week by an investigator at least three days before the next behavioral assay. Mice were habituated to behavioral test location while still in their home cage for a minimum of 30 minutes before testing began. All testing materials were cleaned thoroughly with ddH2O and/or 70% ethanol before and between trials. All investigators were blind to animals’ genotypes while running tests and gathering data.

Elevated Plus Maze (EPM)

The elevated plus maze was run in an acrylic chamber with arms 30 cm long and 5 cm wide. Two opposing arms have walls that were 15 cm high (closed arms), while the other two arms have no walls (open arms). The maze was elevated 40 cm above the ground, with a barrier around the base. Mice were allowed to freely explore the maze for 10 minutes under dim lighting. Video was recorded from overhead to track the mouse’s movements. Videos were analyzed for the time spent in the open arms of the maze compared to time in closed arms or center using a custom Matlab script.

Open Field Test

Open field test is a measure of anxiety-like behavior in rodents. Mice were placed individually into a 40 cm × 40 cm × 40 cm matte black acrylic testing chamber with matte white acrylic floor under dim lighting. Exploratory behavior was recorded from above and videos were tracked using custom Matlab scripts to analyze distance traveled and time spent within a 5cm radius of the center of the chamber.

Novel Object Recognition Test (NORT)

Texture NORT was used as a measure of texture discrimination, as previously described (Orefice et al., 2016). For these experiments, we instituted specific handling protocols to ensure minimal stress during the repeated transfers between the home cage and testing chamber. Kimwipes were added to the wire cage hopper to encourage the mice to nest build and socialize, minimizing anxiety and male-to-male aggression. These kimwipes were used to scoop mice into the palm of the investigator’s hand, applying gentle pressure to the tail to secure them during transfers, and mice were allowed to step off the investigator’s hand at the end of the transfer.

For two consecutive days (day 1 and 2) mice were individually habituated to an empty testing chamber (40 cm × 40 cm × 40 cm) under dim lighting for 10 minutes. Mice were then tested on color/shape NORT (day 3) and texture NORT (day 4).