Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Virus capsids, the protective protein shell of a virus with typical dimensions in the nanometer range, are a challenge to analyze. Ideal analytical techniques need to characterize the morphological, chemical, physical, and mechanical properties of the capsids. Measurements require excellent size resolution, precise temporal control, label-free detection, compatibility with typical buffers, and execution under biologically relevant conditions. Ensemble techniques often obscure infrequent events in a complex mixture; consequently, single-particle techniques with sufficient throughput provide both information about the heterogeneity of individual particles and statistics of the population itself. Because no existing instrumentation can examine all these characteristics, several techniques are often needed to develop an understanding of virus capsids and their fundamental properties. Here, we highlight recent advances in virus capsid characterization and review both ensemble and single-particle methods, including light scattering techniques, fluorescence spectroscopy, mass spectrometry, resistive-pulse sensing, electron microscopy, atomic force microscopy, size exclusion chromatography, and field-flow fractionation.

Because virus capsids are produced by self-assembly of one or more protein subunits over a range of reaction conditions, timescales, and length scales,1 effectively studying the self-assembly process may be the most formidable measurement problem. Most capsids with icosahedral, roughly spherical, geometries have diameters from tens to hundreds of nanometers, whereas helical capsids have lengths that can extend to a micron or more. The self-assembly of virus capsids is a polymerization reaction that may require participation of the viral genome, scaffold proteins, or both.2 Due to the multiple steps and error-correction mechanisms involved, the virus assembly reaction is a very complicated process. Understanding the mechanisms by which viruses assemble can lead to the development of robust theoretical models.3–6 These models can subsequently accelerate the development of antivirals that target the assembly process7–8 and advancement of new biomaterials9 and nano-reactors.10–11

From an analytical perspective, characterization of these biomolecules is nontrivial, because their sizes and masses exceed the dynamic range of many conventional analytical techniques. In response, we have witnessed development of not only improved instrumentation but also highly specialized instrumentation to answer questions specifically related to characterization of virus-sized particles. From a dialectic perspective, the many outstanding questions in virology have necessitated these developments in analytical chemistry, which, in turn, have led to even more intriguing questions being posed.

OPTICAL METHODS

Optical methods based on light scattering are widely used for the analysis of viruscapsids and their assembly due to their inherently excellent temporal resolution, theirability to reveal information about average particle sizes in solution, their commercialavailability, and ease of use. Recently, development of new instrumentation has enabledlight scattering measurements at the single-particle level, which promises an exciting future for the field, as unbeatable temporal resolution and high sensitivity are achieved with a single measurement. Another single-particle optical technique is fluorescence correlation spectroscopy, which provides excellent sensitivity at very low capsid concentrations, but requires a fluorescent label, which may ultimately influence particle properties.

Static Light Scattering.

In the simplest case, virus assembly reactions are a mixture ofsubunits and capsids, and to quantify the extent of assembly only requires the measurement of the change in a signal, such as turbidity (light scattering at 180°) or staticlight scattering at a given angle with time. Static (or Rayleigh) light scattering, measured at a 90° angle from the incident beam, has offered a significant amount of information for kinetic studies of virus capsid assembly. Bigger particles scatter more light; thus, the amount of scattered light identifies relative changes in the molecular weight of the analytes and can be correlated with the extent of assembly. Although this method does not measure the size of the assembled particles, light scattering is widely used due to its simplicity and its very high temporal resolution. In terms of instrumentation, turbidity can be measured in a UV/vis spectrophotometer and light scattering at 90° in a fluorometer; to maximize the signal, the shortest wavelength where there is no sample absorbance is typically chosen. In 1993, Prevelige et al. used turbidity to follow assembly of phage P22.12 In 1999, Zlotnick and coworkers studied the kinetics of the assembly of hepatitis B virus (HBV) capsids in vitro by light scattering.4 These light scattering measurements showed a lag phase followed by sigmoidal kinetics, and the results tested a kinetic model that treated an assembly reaction as a cascade of low order reactions with a rate-limiting nucleation step. Also, light scattering measured the change in reaction rates of HBV assembly with core protein assembly modulators (CpAMs), which are small molecules that influence the kinetics and thermodynamics of virus assembly and are potential antivirals. Faster kinetics and higher assembly yields were observed, when HBV capsids were assembled in the presence of heteroaryldihydropyrimidine (HAP)13 and phenylpropenamide derivatives.14

Whereas light scattering measurements were correlated with the extent of HBV assembly, they could not be directly correlated with the extent of cowpea chlorotic mottle virus (CCMV) capsid assembly due to the heterogeneity of the assembly intermediates.15 During the assembly of these virus capsids, multiphase kinetics were observed. To interpret the light scattering data, a rapid formation of pentameric units followed by slow formation of virus capsids was proposed as the reaction mechanism. Light scattering was also used for measurements of the assembly of human papillomavirus (HPV) capsid assembly.16 Dimers of pentameric units were concluded to be the nucleus (rate-limiting step) for capsid formation. To test the simple kinetic model developed by Zlotnick and coworkers,4 Dragnea and colleagues studied the assembly of brome mosaic virus (BMV) capsids with faster time-course light scattering measurements.17 The faster than expected initial reaction takeoff required a modification to the kinetic model for BMV. In addition to monitoring assembly, light scattering offers information about the kinetic rates of virus disassembly. In a virus dissociation study, the stabilizing function of the SP1 peptide was revealed, but kinetic rate constants could not be determined for the disassembly of human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1) capsids.18

Static light scattering has also been used to extract size information and to quantify virus capsids. Multiangle light scattering (MALS) detectors are commonly coupled with size exclusion chromatography (SEC) and field flow fractionation (FFF).19 MALS detectors determine the weight average molar mass and the average size of particles by detecting the scattered light at multiple angles and extrapolating to 0°. Although MALS offers additional information, it is more susceptible to noise and impurities.16 That is why static light scattering measured at 90° angle from the incident beam is preferred for measuring reaction rates. Besides applications in kinetics studies, a method for the quantification of virus particles in solution is based on light scattering measurements of a standard solution, which consists of polymeric particles with sizes comparable to the sizes of virus particles of interest.20

Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS).

DLS is also known as quasi-elastic light scattering (QELS). Sizing of particles with DLS is based on measuring fluctuations of the lights cattered by the sample over time. Determining the diffusion coefficients of particles allows the estimation of their radius by the Stokes-Einstein equation. Because the assumption of spherical, homogenous populations of particles is necessary to transform the intensity measurements to particle diameter, DLS analysis becomes less certain when applied to heterogeneous samples. Thus, DLS measurements are usually complemented by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). For example, DLS and TEM were used to determine how the size and triangulation (T) number of BMV particles vary as a function of the size of gold nanoparticle templates.21 The size of influenza A virus VLPs (virus-like particles) was determined with DLS, and TEM determined their morphology.22 DLS and EM offered information about the size of VLPs in a vaccine against chronic HBV.23 DLS enabled the characterization of feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) capsid assembly in vitro.24 Under conditions that favored the assembly of the virus, an increase of the average diameter of the particles was observed on the timescale of minutes. EM measurements confirmed the assembly of morphologically normal, spherical capsids. DLS and TEM were also used for determining the sizes of alphavirus nucleocapsid cores assembled around different polyanionic cargos.25 In addition, the intensity of the scattered light was used to determine the relevant amounts of particles assembled and disassembled due to high ionic strengths. As hypothesized, alphavirus nucleocapsid cores, called core-like particles (CLPs), that contained longer cargoes were found to be more stable.

Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA).

NTA is a commercial system for sizing particles with diameters from 30 to 1000 nm.26 Similar to DLS, the scattered light is measured over time. However, a charge-coupled device (CCD) tracks individual particles in the solution. In a study that compared DLS and NTA for the analysis of VLPs, NTA had better resolution, performed better for the analysis of polydisperse solutions, but required longer acquisition times.26 More recently, two different research groups used NTA to quantify virus and protein particles.27–28 Both studies concluded that NTA can quantify protein particle populations, but only after careful optimization of the recording and data analysis settings.

Single-Particle Light Scattering Imaging.

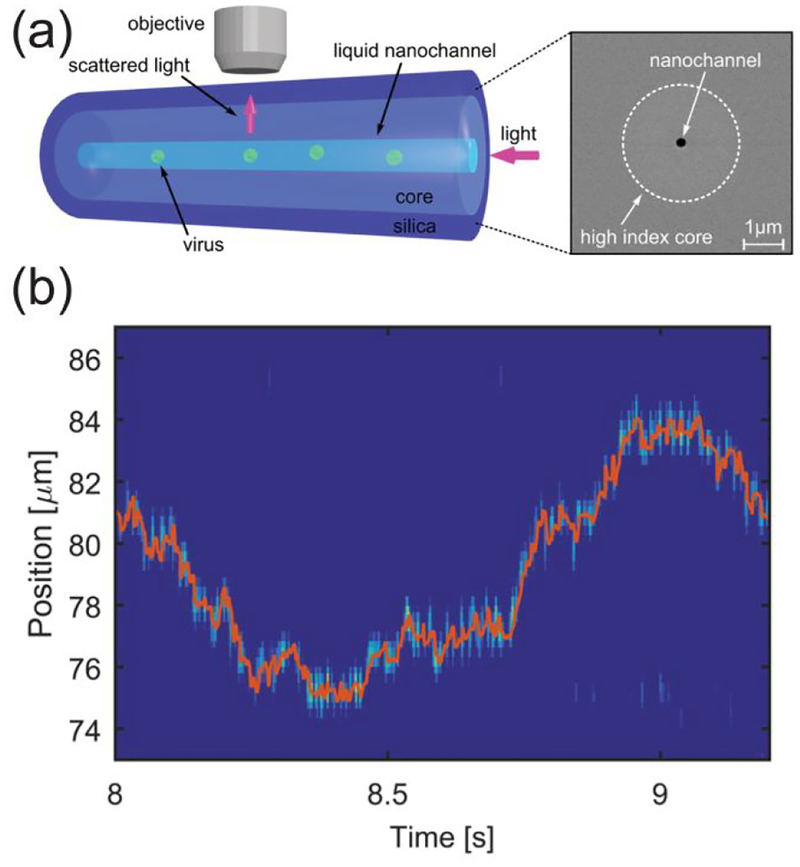

Development of new instrumentation to track and study individual virus capsids and their assembly by light scattering is undeniably the most interesting progress reported in the field of light scattering. Figure 1a shows an experimental set-up for the high-speed tracking of individual virus particles.29 In this work by Manoharan and coworkers, CCMV particles were driven by capillary forces through a fluidic, optical fiber made of GeO2-doped silica. This ‘opto-fluidic’ platform measured individual particles with subwavelength precision and microsecond time resolution (Figure 1b). In more recent work by the same group, RNA molecules were tethered to a coverslip and protein capsids were assembled around the RNA.30 This experimental set-up enabled light-scattering measurements of the assembly of individual virus particles, and self-assembly kinetics were extracted for individual particles for the first time.

Figure 1.

Single-particle light scattering imaging. (a) Schematic of the apparatus for tracking of single virus particles in a nanofluidic optical fiber and an SEM image of the fiber cross section. Capillary forces drive the capsids through the fiber, and light scattered from individual virus particles is measured from above. (b) Detected position of a freely diffusing CCMV particle in water with time. Reproduced from Faez, S.; Lahini, Y.; Weidlich, S.; Garmann, R. F.; Wondraczek, K.; Zeisberger, M.; Schmidt, M. A.; Orrit, M.; Manoharan, V. N., ACS Nano 2015, 9, 12349–12357 (ref.29). Copyright 2015 American Chemical Society.

Fluorescence Correlation Spectroscopy (FCS).

Fluorescence measurements offer valuable information about biological processes at the single-particle level due to their high sensitivity.31–32 With fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (FCS), important insights into studies of virus capsids and their assembly reaction in vitro have been made. Labeling the coat protein of the capsid with a fluorescent probe allows monitoring the assembly reaction, and labeling of the viral genome permits tracking the conformation changes of the viral genome during packaging. The kinetics of DNA packaging for bacteriophage T4 were captured by FCS as a measurement of the change in diffusion coefficients between the labeled, free DNA and DNA packaged inside the T4 capsid.33 At very low concentrations, the high sensitivity of fluorescence allows single molecule (smFCS) observation of RNA packaging during the assembly of bacteriophages MS2 and satellite tobacco necrosis virus (STNV).34 The core protein of both these viruses, as well as the viral RNA, were labeled with a fluorescent probe. This study showed that packaging of the RNA during the assembly process results in a rapid collapse of the conformation RNA occupies in solution. In a more recent study of STNV with smFCS, certain regions of the viral DNA, termed packaging signals, were found to mediate the assembly.35 Consequently, design of specific genome sequences can facilitate manipulation of the assembly process.

MASS SPECTROMETRY (MS)

The development of electrospray ionization (ESI) sources has led to an increased use of mass spectrometry for the analysis of biological samples and large biomolecules. Currently, mass analyzers are the only instruments able to measure the mass of virus capsids and their intermediates. In addition, MS provides sufficient temporal resolution for real-time analysis of virus assembly. However, ESI sources require use of volatile buffers and are incompatible with typical assembly buffers, e.g., NaCl. Also, because the particles must be transferred to the gas phase to be measured, complete desolvation of the complex can pose a problem.

Native Mass Spectrometry.

Both ESI36 and matrix assisted laser desorption ionization (MALDI)37 facilitate analysis of large biomolecules by MS. These soft ionization methods are able to maintain in gas phase the state that biomolecules had in solution prior to ionization (‘native’ state) with careful selection of solution parameters such as buffer composition, pH, and ionic strength.38 In an ESI source, the sample passes through a capillary with a high voltage applied, and the charged droplets generated decrease in size by Coulombic repulsion forces. For native mass spectrometry, nano-electrospray ionization (nano-ESI), that involves a spray orifice with a diameter of 1 – 10 μm (i.e., an order of magnitude smaller compared conventional ESI), is more popular and allows the use of small sample volumes, micromolar concentrations, and low flow rates.39 Despite the large number of success stories in the field, there are also several limitations, which are rooted in the requirement for volatile buffers, change in the strength of hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions in gas phase, and incomplete desolvation during ionization.39–40 These limitations are challenges that must be overcome.

In one of the first applications of ESI for ionization of virus particles, infectious icosahedral rice mottle virus (RYMV) and rod-shaped tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) particles were sprayed into a mass spectrometer, collected, and imaged by TEM.41 Although these virus particles were not detected with the quadrupole analyzer because of their very high m/z values, TEM images showed that ESI did not disrupt the quaternary structure of the capsids. The first successful measurement of intact virus capsids with a mass analyzer was reported in 2000,42 in which intact bacteriophage MS2 virus capsids were measured with a time-of-flight (TOF) mass analyzer.

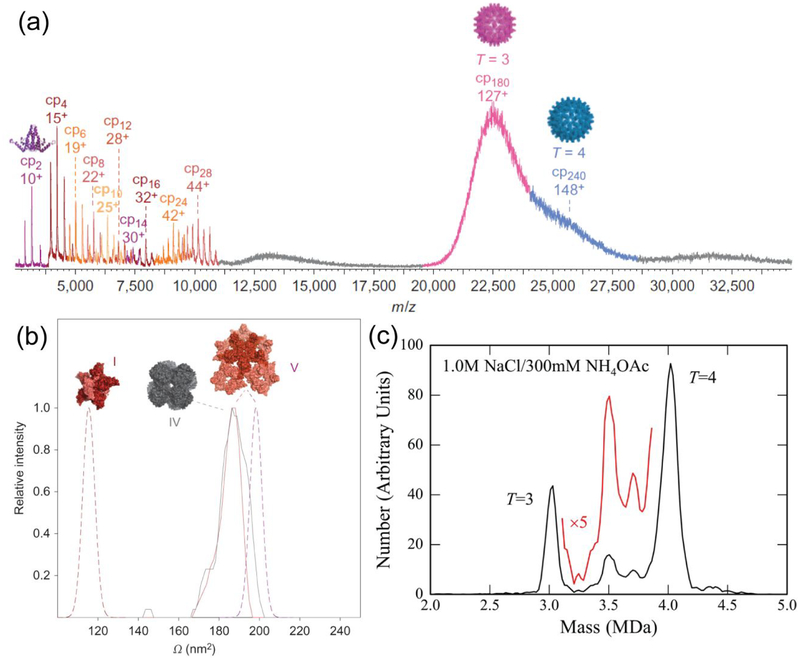

More recently, Heck and coworkers studied extensively the in vitro assembly of HBV capsids initiated in ammonium acetate at various concentrations and pHs.43 High resolution spectra of virus particles and their small oligomers formed during assembly were achieved with a quadrupole-time-of-flight (Q-TOF) instrument. As seen in Figure 2a, the resolution of the instrument is excellent for identifying small species, but becomes significantly worse for the analysis of fully formed T = 3 and T = 4 HBV capsids. To extract further information about the morphology and shapes of the small oligomers, they were analyzed with ion mobility-mass spectrometry (IM-MS). Figure 2b illustrates the comparison of the measured collision cross section (Ω) of a small oligomer formed during HBV assembly and a globular protein with higher mass. The fact that these two proteins shared the same Ω value showed that the HBV oligomer has a more extended structure in space. Stepherd et al. studied small HBV oligomers and their changes in the presence of a CpAM with IM-MS.44 To evaluate the limitations of gas-phase electrophoretic mobility molecular analysis (GEMMA) – a technique that separates single-charged particles based on their electrophoretic mobilities −, native mass spectrometry was used in parallel with GEMMA.45 The measurements from these two techniques correlated well for intact capsids. However, for the analysis of empty capsids and smaller intermediates, several parameters, which cannot be easily predicted, were found to affect the electrophoretic mobility and hydrodynamic diameter measured by GEMMA.

Figure 2.

Mass spectrometry. (a) Time-of-flight mass spectrum of HBV assembly with 15 μM dimer in 250 mM ammonium acetate (pH 6.8). The presence of small oligomers consisting of up to 28 monomers (14 dimers) can be observed in the m/z spectrum. (b) Ion mobility-mass spectrometry measurement of collision cross-sections (Ω) of the HBV 28-mer (structure V, 447 kDa) and a globular protein complex with higher mass (VAO 8-mer, structure IV, 510 kDa). The solid and dashed lines represent Ω values estimated from experiments and from the crystal structure of the virus capsid (V) and a collapsed structure (I), respectively. Reprinted by permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd: Nature Chemistry, Uetrecht, C.; Barbu, I. M.; Shoemaker, G. K.; van Duijn, E.; Heck, A. J. R., Nat. Chem. 2011, 3, 126–132 (ref.43), copyright 2011. (c) Charge detection mass spectrum of HBV capsid assembly. Assembly was initiated with 40 μM dimer in 50 mM HEPES with 1 M NaCl, and after 48 h, the assembly buffer was exchanged to ammonium acetate. Reproduced from Pierson, E. E.; Keifer, D. Z.; Selzer, L.; Lee, L. S.; Contino, N. C.; Wang, J. C. Y.; Zlotnick, A.; Jarrold, M. F., J Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 3536–3541 (ref.50). Copyright 2014 American Chemical Society.

Charge Detection Mass Spectrometry (CDMS).

CDMS is a single-molecule technique that measures both the charge (z) and mass-to-charge (m/z) ratio for individual ions.46 The charge of the ion is imaged and measured by a charge sensitive preamplifier, while the time-of-flight of the ion through the mass analyzer returns the m/z ratio. Single-molecule mass spectrometry is advantageous in the case of very heterogeneous samples where the number of the masses present is significantly higher than the ions sampled.47 However, issues associated with complete desolvation still persist. For complex samples, single molecule measurements can lead to mass spectra with higher resolution compared to spectra obtained with native mass spectrometry.

RYMV and TMV were the first intact virus capsids measured by CDMS.46 The mass measurements obtained by CDMS were in close agreement with estimated molecular weights of icosahedral RYMV and rod-shaped TMV. More recently, the heterogeneous products of assembly of two coat protein variants of bacteriophage P22 were characterized by CDMS.48 Chemical-cross linking was required to stabilize the particles prior to ESI. More specifically, the products ranged from 5 to 25 MDa and varied in triangulation (T) numbers. In the same study, the charge measurements were used to distinguish compact structures from less dense hollow particles. In other work, 50 MDa infectious bacteriophage P22 viruses were successfully transferred to gas phase, and their masses were accurately measured.49

CDMS has also been used for the analysis of HBV capsid assembly. Late-stage intermediates of in vitro HBV assembly were successfully detected and analyzed.50 To kinetically trap intermediates, assembly was initiated at high dimer and NaCl concentrations, and after 48 h, the buffer was exchanged to ammonium acetate to be compatible with ESI. As seen in Figure 2c, the high resolution achieved for high masses allowed T = 3 and T = 4 HBV capsid distributions to be baseline resolved and enabled the characterization of the more stable, persistent late-stage intermediates with masses between that of the T = 3 and T = 4 capsids. More recently, CDMS was used for real-time analysis of HBV assembly initiated in ammonium acetate.51–52 As expected, the population of small oligomers decreased over time, as they reacted to form T = 4 HBV capsids. Interestingly, overgrown HBV particles were observed and annealed to form regular HBV capsids on the timescale of days.

Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange Mass Spectrometry (HDX-MS).

Although virus capsids are not measured intact in an HDX-MS experiment, the coupling of hydrogen-deuterium exchange to mass spectrometry has been widely used and offers important information about dynamic changes in virus capsids.53 After isotopic exchange, the virus particles are typically digested, and the polypeptides are chromatographically separated and measured by MS. The rates at which the peptides of a virus capsid exchange their hydrogens depend on their chemical environment and their possible shielding from the solvent.54 Differences in the exchange rates of amide hydrogens between immature and mature HIV capsids suggested that only half of the HIV capsid protein assembles into the conical core.55 Variation in the exchange rates of hydrogens during particle maturation has been observed for several viruses, including the bacteriophage P22,56 lambda-like bacteriophage HK97,57 and nudaurelia capensis omega virus (NωV).58 In the latter study, the exchange rates exhibited a bimodal distribution for the hydrogens of the same peptide in the NωV capsid; in one population, the peptide exchanged 30% of its protons, whereas in the other population, the peptide exchanged 80% of its protons. This difference was explained by structural data. Different exchange rates of hydrogens were also observed due to binding of antibodies to HBV capsids.59 Besides the observation of dynamic changes of virus capsids at equilibrium, conformational transitions in the minute virus of mice (MVM) capsids at increased temperatures were recently studied with HDX-MS.60 Global structural rearrangements of MVM occurred during translocation events through the capsid pores during the virus infection cycle.

RESISTIVE-PULSE SENSING

Techniques with sensitivity to detect single molecules are the ultimate target of analytical chemistry, especially for biosensing applications where the samples can be inherently heterogeneous. Recent advances in nanofabrication61 have led to the development of robust resistive-pulse sensors (fluid-based particle counters) for extensive analysis of virus capsids and their assembly. Resistive-pulse sensing is well suited for the real-time analysis of virus assembly, because these measurements are compatible with typical assembly buffers, conducted under biologically relevant conditions, take place in solution, and have sufficient temporal resolution.

Resistive-Pulse Sensing with Out-of-Plane Pores.

In a typical resistive-pulse experiment, the particles of interest pass through a single, three-dimensional (‘out-of-plane’) pore with dimensions similar to that of the particles. The particles are driven through the pores either by an applied potential or by a pressure gradient, and detection is based on measuring a difference in conductivity during translocation of the particle. Generally, the amplitude of the current pulses correlates with the particle size, pulse width with the particle length, and pulse frequency with the particle concentration. The first resistive-pulse sensor developed by Coulter was a fluidic counter for individual blood cells.62 Later, DeBlois and coworkers sized and quantified a variety of nanoparticles and virus particles.63–64

More recent developments in the fields of nano- and microfabrication catalyzed the fabrication of a wide variety of solid-state pores to size a large range of sub-micron particles.61,65–67 A pore with a 650 nm diameter nanomachined with a femtosecond pulsed laser on a glass substrate detected paramecium bursaria chlorella virus (PBCV-1) particles and quantified the number of antibodies bound to individual virus particles.68 In an experimental and theoretical study of the noise and signal bandwidth of resistive-pulse current recordings, PBCV-1 particles were measured on pores fabricated in glass and polyethylene terephthalate (PET).69 The basic conclusions were that the signal bandwidth limits the time resolution of changes in the current, whereas the noise levels can be used to estimate the sensitivity of a given pore. In another study, track-etched pores ~40 nm in diameter, fabricated in a PET membrane, offered sufficient size resolution for the analysis of T = 3 and T = 4 HBV capsids that differ only by 4 nm in diameter.70 More recently, pores with diameters in the range of 20 to 500 nm integrated between two microfluidic channels were used for sizing HIV and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) particles.71 The pores were fabricated with electron beam lithography and anisotropic wet etching, and the fabrication error was less than 10 nm.

To understand the physics of translocation during resistive-pulse measurements, the 880 nm long filamentous virus fd was measured on nanopores with diameters ranging from 12 to 50 nm, fabricated with a transmission electron microscope (TEM) in silicon nitride membranes.72 In contrast to DNA molecules, filamentous virus fd is stiff and could only be translocated through the pores if oriented lengthwise. Although electrophoretic forces tended to correctly orient the virus particles lengthwise, the same forces tended to trap the virus at the pore entrance, preventing translocation. Indeed, current events with smaller amplitudes and shorter widths that corresponded to particle collisions with the pore were observed in the current traces. In comparison, events of successful translocation through the pore had higher pulse amplitudes and pulse durations. As a follow up to this work, resistive-pulse measurements of filamentous virus fd were compared with measurements of the filamentous virus M13, which has a smaller charge density.73 Existence of a ‘stagnant’ layer of counterions close to the particle surface was an important parameter for predicting and understanding the electrokinetic translocation of viruses.

Tunable Resistive-Pulse Sensing.

Tunable resistive-pulse sensing can be considered a subcategory of resistive-pulse sensing with out-of-plane pores. The primary difference is the pore is fabricated in an elastomer membrane, which allows ‘tuning’ of the pore dimensions by mechanical tension.74 These tunable pores offer further versatility, as they can be stretched in real-time to accommodate the analyte of interest.75 To date, infectious rotavirus capsids,76 vesicular stomatitis virus particles,77 HIV-1 VLPs,78 and lentivirus particles79 have been measured and quantified by tunable resistive-pulse sensing.

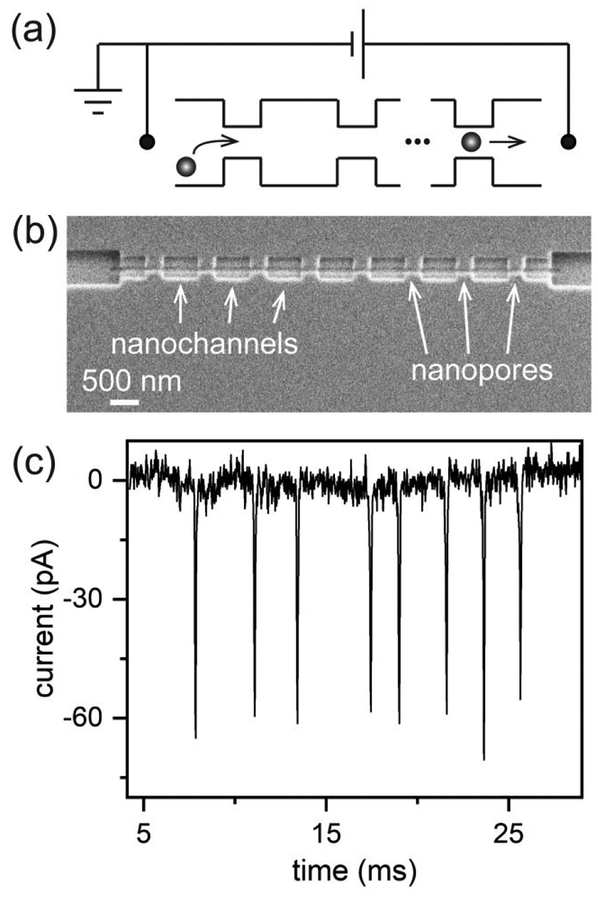

Resistive-Pulse Sensing with Multiple In-Plane Pores.

Two-dimensional, in-plane designs for nanopore fabrication offer unique advantages including straightforward coupling of nanofluidic components with microfluidic networks and fabrication of nanopores in-series or in-parallel.80 Fabrication of multiple pores in series is advantageous, because individual particles can be measured multiple times (Figure 3a). For example, Figure 3b shows a nanofluidic device that consists of eight pores connected in series. The corresponding current trace from the measurement of an individual T = 4 HBV capsid is shown in Figure 3c. Multiple measurements create a unique pulse sequence that has been used to unambiguously identify particle translocation. Also, multiple measurements of pulse amplitude and the time between adjacent pulses (pore-to-pore time) increase the resolution of particle size measurements and estimate the electrophoretic mobility of particles with higher precision, respectively.

Figure 3.

Resistive-pulse sensing. (a) Schematic of resistive-pulse measurement with an in-plane, multi-pore device. Virus capsids are electrokinetically driven through the series of pores by an applied potential. (b) Scanning electron microscope (SEM) image of a nanofluidic device with 8 pores connected in series, and (c) the corresponding 8-pulse sequence resulting from the translocation of a single T = 4 capsid through those 8 pores. Reproduced from Kondylis, P.; Zhou, J.; Harms, Z. D.; Kneller, A. R.; Lee, L.; Zlotnick, A.; Jacobson, S. C., Anal. Chem. 2017, 89, 4855–4862 (ref.80). Copyright 2017 American Chemical Society.

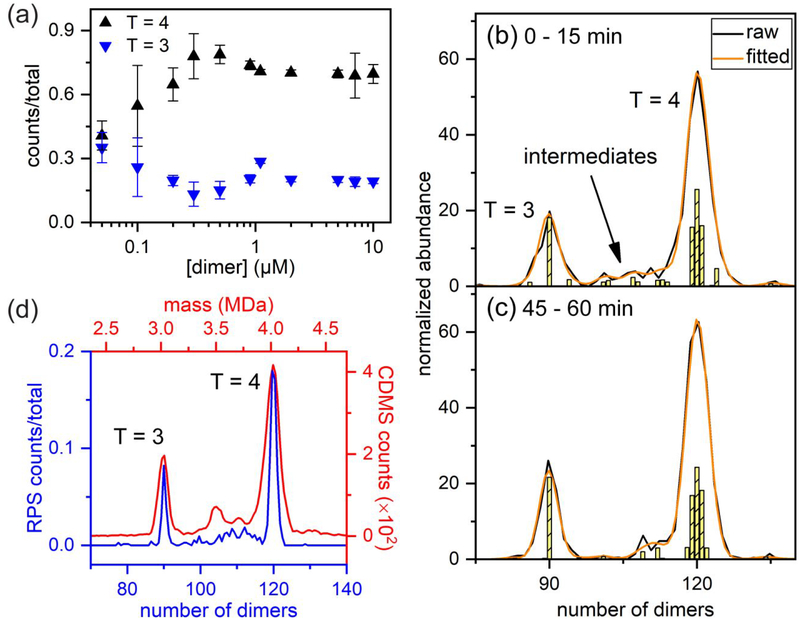

Devices with two 50 nm wide, 50 nm deep, and 40 nm long pores connected in series were successfully fabricated on a silicon wafer with electron beam lithography and reactive ion etching.81 These devices were used to measure T = 4 HBV capsids. Later, devices with two pores in series were milled with a focused ion beam (FIB) instrument directly.82 On these devices, T = 3 and T = 4 HBV capsid distributions were baseline resolved. In addition, the electrophoretic mobilities of these HBV capsids were experimentally determined based on the pulse widths and pore-to-pore times. Then, these 2-pore devices were used to characterize HBV capsid assembly over a range of conditions.83 In that study, the faster formation of T = 3 capsids, and the slower annealing of late-stage pre-T = 4 intermediates were experimentally observed for the first time. In the same work, more than 700,000 individual virus particles were measured across five nanofluidic devices, demonstrating the robustness of this resistive-pulse platform. Figure 4a summarizes extensive characterization of HBV assembly products formed in vitro over a wide range of core protein dimer concentrations. Most interestingly, the relative abundances of T = 3 and T = 4 capsids depend on the initial protein dimer concentration.

Figure 4.

Resistive-pulse sensing and charge detection mass spectrometry of capsid assembly. (a) Variation of the relative abundances of T = 3 and T = 4 capsids assembled in 1 M NaCl with initial dimer concentration. For this plot, more than 700,000 HBV particles were measured on five 2-pore nanofluidic devices. Reproduced from Harms, Z. D.; Selzer, L.; Zlotnick, A.; Jacobson, S. C., ACS Nano 2015, 9, 9087–9096 (ref.83). Copyright 2015 American Chemical Society. Histograms of average pulse amplitudes from (b) 0 to 15 min and (c) 45 to 60 min of a capsid assembly reaction of HBV. The measurements were taken on an 8-pore device, and the enhanced resolution permitted observation of the shift in the population of intermediate species in real-time. Reproduced from Kondylis, P.; Zhou, J.; Harms, Z. D.; Kneller, A. R.; Lee, L.; Zlotnick, A.; Jacobson, S. C., Anal. Chem. 2017, 89, 4855–4862 (ref.80). Copyright 2017 American Chemical Society. (d) Overlay of histograms from measurements of HBV capsid assembly in equilibrium with multi-cycle resistive-pulse sensing (RPS) and with charge detection mass spectrometry (CDMS). These two techniques represent the highest resolution measurements of particle size distributions for capsid assembly products. Reproduced from Zhou, J.; Kondylis, P.; Haywood, D. G.; Harms, Z. D.; Lee, L. S.; Zlotnick, A.; Jacobson, S. C., Anal. Chem. 2018, 90, 7267–7274 (ref.84). Copyright 2018 American Chemical Society, and from Pierson, E. E.; Keifer, D. Z.; Selzer, L.; Lee, L. S.; Contino, N. C.; Wang, J. C. Y.; Zlotnick, A.; Jarrold, M. F., J Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 3536–3541 (ref.50). Copyright 2014 American Chemical Society.

To further increase the measurement precision, e.g., resolution of the particle size distributions, devices with up to 8 pores in series were fabricated.80 On these devices, assembly intermediates were characterized in real time (Figure 4b,c). During the first hour of the HBV assembly reaction, the relative abundance of smaller intermediates decreased, whereas the relative abundance of larger intermediates with sizes closer to that of the T = 4 HBV capsid remained constant. To increase the size resolution even further, individual HBV capsids and their assembly intermediates were cycled back-and-forth through a series of 4 pores.84 Each time a particle passed through the pores, the polarity of the applied potential was switched to drive the particle back through the pores again, and so on. This molecular ping-pong experiment sacrifices temporal resolution because of the increase in data acquisition time for each particle, but can achieve ultra-high resolution to discriminate particles that differ in size by few dimers for the analysis of assembly at equilibrium. Currently, the highest resolution measurements for HBV assembly in equilibrium have been achieved with multi-cycle resistive-pulse sensing and with CDMS (Figure 4d). In another study, devices with 4 pores connected in series were used to understand the in vitro assembly of simian virus40 (SV40) VP1 particles around different polyanion templates.85 Particle morphology was affected by both template length and template structure. Multipore devices played a significant role in characterizing a very heterogeneous mixture of assembly products formed in the presence of a heteroaryldihydropyrimidine (HAP) derivative, and the results revealed a direct competition between normal and drug-induced assembly.86 In this recent study, pulse amplitudes were correlated with the number of dimers in the capsid, and pulse widths were correlated with the particle lengths, which provided morphological information about the particles.

Another advantage of in-plane pores is that they can be easily coupled to more complex fluidic components. To increase the detection bandwidth, a submicron pore was integrated to a fluidic, balancing restriction.87 These two fluidic components formed a voltage divider which allowed the submicron pore to be biased at a constant voltage by a source with low output impedance. The device was made in PDMS by micromolding, and the nanopore was 250 nm wide, 250 nm long, and 290 nm deep. On this device, bacteriophage T7 particles were detected in salt solutions and in solutions of mouse blood plasma.

ELECTRON MICROSCOPY (EM)

The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2017, awarded to Jacques Dubochet, Joachim Frank, and Richard Henderson for developing cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM) to study biological molecules with high resolution, substantiates the recent revolution in the field of electron microscopy and its importance analytical chemistry, biochemistry, and biology. In particular, cryo-EM is extremely powerful for the analysis of very homogeneous and structurally identical fully formed virus capsids; three-dimensional (3D) capsid reconstructions is achieved with near-atomic resolution by averaging multiple two-dimensional (2D) images. Cryo-EM cannot be used for the analysis of very heterogeneous samples, which prevent classification and averaging of multiple 2D images. Consequently, negative-stain transmission electron microscopy (TEM) with a dehydration step is often used to reveal sample heterogeneities, but with lower resolution and possible distortion or flattening of fragile structures. The relatively low throughput and temporal resolution of TEM analysis are offset by the ability to acquire unique morphological information.

Negative-Stain Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM).

Negative-stain TEM offers qualitative morphological information about virus capsids and has been extensively applied to virus diagnosis.88–89 Over the last few decades, a large number of previously unknown virus families have been isolated from cells and examined with negative-stain TEM. Prior to TEM imaging, the virus capsids are fixed onto a surface, dehydrated, and stained with a heavy metal salt (e.g., uranyl acetate). In this case, the stain is not applied to the viruses, but to the surrounding space. Besides diagnostic applications, negative-stain TEM has been proposed for quantitative analysis of viruses. In two studies, latex90 and gold91 particle standards enabled the quantification of virus particles with TEM. Disadvantages of this quantification method is the low throughput and sensitivity. More recently, to eliminate the need for negative staining and to increase the throughput, a scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) detector in a scanning electron microscope (SEM) was used to quantify Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus (VEEV) and eastern equine encephalitis virus (EEEV) particles.92 Prior to imaging, the virus particles were mixed with a gold particle standard. To study virus assembly products formed in vitro, negative-stain TEM was used to visualize the observation of assembly intermediates14 and to validate resistive-pule83,85 and MS50 data. Also, averaging of 2D imagesenabled the reconstruction of brome mosaic virus (BMV) VLPs in three dimensions and the determination of their triangulation (T) numbers.21

Cryogenic Electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM).

Cryo-TEM has been the key for the structural analysis of many viruses the past few years.93 In conventional EM, dehydration of the sample and adsorption to a support can damage virus capsids, whereas in cryo-EM, samples are unfixed, unstained, and frozen-hydrated, which minimizes damage to virus capsids and maintains their 3D structure.94 In addition, the structure of the virus capsids of interest can be reconstructed in three dimensions with high resolution by averaging the 2D projection images of multiple individual capsids.95 The first reconstructions with near-atomic resolution (<4 Å) were reported for the inner capsids of the icosahedral rotavirus96 and cytoplasmic polyhedrosis virus.97 Near-atomic resolution reconstruction of the rod-shaped virus SIRV2 (sulfolobus islandicus rod-shaped virus 2) was also possible because of the sufficient regularity of its structure.98 However, 3D reconstruction of enveloped viruses with less structural regularity, such as HIV, is achievable, but at lower resolution.99

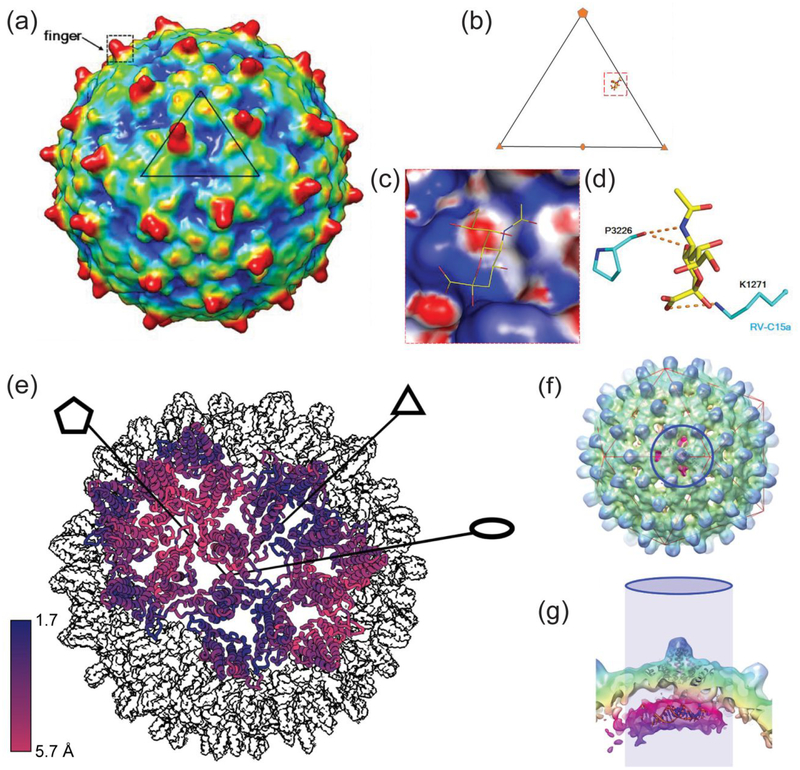

In some of its most important applications, 3D cryo-EM reconstruction can help with the development of new antiviral therapeutics and vaccines. In a recent study of the rhinovirus C (RV-C), spikes/fingers, possible immunogens, that could have utility as vaccines, were observed with near-atomic resolution reconstruction of the virus capsid (Figure 5a).100 Figure 5b–d shows a region in RV-C canyons that could bind sialic acid, which indicated an important role of glycans in RV-C1 receptor interactions. Necessitated by the recent spread of Zika virus (ZIKV), near-atomic resolution cryo-EM reconstruction of the mature ZIKV capsid revealed differences between a glycosylation site of ZIKV and that of other flaviviruses.101 A carbohydrate moiety located in this region could be an attachment site of the ZIKV capsids to host cells. Cryo-EM also characterized the 3D structure of HPV VLPs in a vaccine, not only by itself, but also after ‘decoration’ with neutralizing antibodies.102 In addition, this study showed that the VLPs retained their integrity even after adsorption to aluminum adjuvants, which are commonly used in vaccines to enhance immunogenicity.

Figure 5.

Electron microscopy. (a) A 3D reconstruction of RV-C15a capsids that shows the ‘spiky’ structure of the virus. A possible binding site for sialic acid is represented on an icosahedral asymmetric unit of the virus in (b) and on the surface electrostatic potential in (c). (d) The sialic acid (yellow) interacts with its surrounding neighbors on RV-C15a (cyan). Reproduced with permission from Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA Liu, Y.; Hill, M. G.; Klose, T.; Chen, Z. G.; Watters, K.; Bochkov, Y. A.; Jiang, W.; Palmenberg, A. C.; Rossmann, M. G., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2016, 113, 8997–9002 (ref.100). (e) A 3D reconstruction that points out the differences between an empty T = 4 HBV capsid and a T = 4 capsid with HAP-TAMRA bound in its interior. The reconstructions of the two capsids were oriented based on their center. The differences in the color represent the relative increase in the capsid size due to HAP-TAMRA binding and reveal that the biggest distortion is on the five-fold vertices. Reproduced with permission from eLife Schlicksup, C. J.; Wang, J. C. Y.; Francis, S.; Venkatakrishnan, B.; Turner, W. W.; VanNieuwenhze, M.; Zlotnick, A., eLife 2018, 7, 23. (ref.107) (f) Visualization of RNA feature with an asymmetric 3D reconstruction of T = 4 HBV capsids, and (g) side view of the same reconstruction. Reprinted by permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd: Nature Microbiology, Patel, N.; White, S. J.; Thompson, R. F.; Bingham, R.; Weiss, E. U.; Maskell, D. P.; Zlotnick, A.; Dykeman, E. C.; Tuma, R.; Twarock, R.; Ranson, N. A.; Stockley, P. G., Nat. Microbiol. 2017, 2, 17098 (ref.109), copyright 2017.

HBV is a model system for the development of antivirals that target virus capsid assembly, known as core protein allosteric modulators (CpAMs). Heteroaryldihydropyrimidines (HAPs) and phenylpropenamides are well-studied classes of compounds that can affect and misdirect HBV assembly.13–14,103 Because CpAMs misdirect assembly and result in very heterogeneous products when present during assembly, cryo-EM has shown where these small molecules bind to pre-assembled capsids, and the structural changes they induce. The regularity of preassembled HBV capsids allows image averaging and high resolution reconstruction of the virus with bound HAP molecules. HAP1 bound to a hydrophobic pocket in the interior of HBV capsids causing the five-fold, three-fold, and quasi-six-fold vertices to protrude, open, and flatten, respectively.104 AT-130, a phenylpropenamide derivative, bound to the same hydrophobic pocket as HAP1, but AT-130 favored different quasi-equivalent subunits.105 Unlike HAP1 and AT-130 that increased the capsid diameter by ~1 nm, HAP18 decreased the capsid diameter by 0.3 nm.106 Binding of HAP-TAMRA to preassembled T = 4 capsids created sharp angles and flat regions in the capsids.107 Figure 5e illustrates that most of the defects induced by the binding of HAP-TAMRA were localized at the icosahedral five-fold axis. HBV assembly in the presence of Bay 41–4109 under tuned reaction conditions produced large tubes.108 These tubes had sufficient regularity to facilitate 3D structural averaging and reconstruction, which revealed hexameric arrangement of the subunits and absence of pentamers.

In addition to unique structural information obtained for virus capsids, cryo-EM reconstructions have uncovered information about molecules bound in the interior of highly ordered virus capsids. A recent study showed that specific regions in the pre-genomic RNA have high affinity for the HBV core protein dimers.109 Asymmetric 3D reconstruction of the capsid showed an asymmetric RNA feature bound below the protein shell (Figure 5f,g). Understanding the preferred interactions between RNA and core protein may lead to targets for potential antivirals. Asymmetric 3D reconstruction also showed the structure of HIV and hepatitis C virus (HCV) polymerases bound in the interior of HBV capsids.110 In this example, the only possible way to obtain such a structure is with highly ordered virus capsids.

Cryo-EM has had applications for studying systems with higher dispersion. One example is the assembly of alphavirus core-like particles in vitro.111 In that study, 2D classification of the assembled particles helped explain experimental data based on 3D models. Also, in the case of polydisperse systems, template-assisted assembly may be a possible approach to decrease heterogeneity. For example, bacteriophage P22 was used as a template for the assembly of the Gag structural protein of HIV-1.112 Because the bacteriophage is a monodisperse, electron-transparent template, 2D cryo-EM images clearly showed the radial layering of the P22-Gag particles and the average diameter of the particles.

ATOMIC FORCE MICROSCOPY (AFM)

Atomic force microscopy belongs to the group of single-particle analysis methods; a tip scans over a surface to reveal topographic information. Individual capsids immobilized on a surface (e.g., mica) can be imaged by AFM, and pentameric and hexameric protein arrangements in the virus capsids are recognized and resolved. The need to immobilize the particles on a solid substrate, low throughput, and long time required for data acquisition are disadvantages of probe-based imaging techniques that scan over a surface. Despite these limitations, nanoindentation experiments, in which individual capsids are ‘poked’ with an AFM tip, demonstrate the power of this technique. Mechanical properties of capsids are measured and can be correlated with chemical and physical properties of the particles.

AFM Imaging.

A number of AFM measurements of viruses have been reported, and several reviews have been written for this rapidly expanding field.113–115 AFM was developed in 1980s as a technique to measure forces between a sample and AFM tip.116 The first measurements of virus capsids with AFM were reported in 1992, when TMV particles were the resolution standards for developing specimen preparation methods and optimizing imaging parameters.117 The images obtained with AFM were consistent with cryo-EM data. Later, contact mode AFM characterized the exterior topography of the bacteriophage φKZ capsid, as well as the interior protein surface of a partially dissociated capsid.118

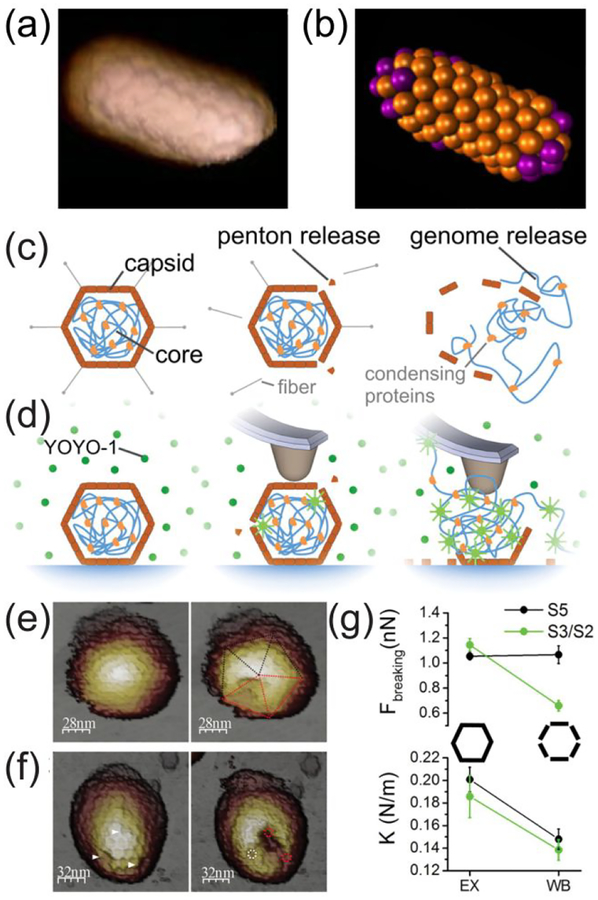

The development of tapping mode AFM in liquids, where the tip taps the surface at the extreme of each modulation cycle, enabled imaging of biomolecules with higher resolution and minimal damage to the sample.119 Usually, the tip oscillates by acoustic excitation in tapping mode AFM; however, alternating magnetic fields can be used for the same purpose. The release of RNA from human rhinovirus capsids under physiological conditions was monitored with magnetically coated AFM tips; viral RNA appeared to be either separated from the capsids or connected with them.120 In a structural study of the tailed cyanophage S-CAM4, viral DNA was found to be protein-free next to ruptured virus heads.121 In the same study, AFM images of infected cells showed that cell lysis happened through individual perforations and not by catastrophic rupture events. More recently, the core protein of BMV, that readily assembles to icosahedral capsids, was assembled around gold nanorods to form spherocylindrical closed protein shells.122 AFM images (Figure 6a) showed the formation of a hexagonal lattice in the body of the cylinder, and molecular dynamic simulations (Figure 6b) offered insight into the assembly mechanism.

Figure 6.

Atomic force microscopy (AFM). (a) AFM image of single spherocylindrical BMV VLP and (b) the corresponding, typical structure obtained from simulations. Reproduced from Zeng, C.; Rodriguez Lázaro, G.; Tsvetkova, I. B.; Hagan, M. F.; Dragnea, B., ACS Nano 2018, 12, 5323–5332 (ref.122). Copyright 2018 American Chemical Society. Schematics of disassembly of adenovirus (c) in vivo, and (d) in vitro. As represented in panel (d), an AFM tip induces the release of pentons, which initiates the disassembly of the virus. The viral genome is released and fluoresces after binding to YOYO-1 dye molecules. Reproduced from Ortega-Esteban, A.; Bodensiek, K.; San Martin, C.; Suomalainen, M.; Greber, U. F.; de Pablo, P. J.; Schaap, I. A. T., ACS Nano 2015, 9, 10571–10579 (ref.137). Copyright 2015 American Chemical Society. (e) AFM images of an expanded bacteriophage P22 capsid before (left) and after (right) nanoindentation. The capsid was indented along the 5-fold axis. (f) AFM image of a whiffle ball P22 capsid before and after the nanoindentation. The capsid was indented along the 3-fold axis. (g) Plots of the breaking force and elastic constant (K) of the 2-, 3-, and 5-fold axes of the expanded and whiffle ball P22 capsids. Reproduced from Llauro, A.; Schwarz, B.; Koliyatt, R.; de Pablo, P. J.; Douglas, T., ACS Nano 2016, 10, 8465–8473 (ref.141). Copyright 2016 American Chemical Society.

Nanoindentation.

Nanoindentation experiments offer unique information about the mechanical properties of virus capsids.123 In a nanoindentation experiment, the capsid is imaged with AFM at first, and then, the capsid is indented at specified locations.124 The change in indentation as a function of the force offers information about the rigidity and strength of the capsids (force that causes rupture and critical deformation). In one of the first applications with viruses, the Young’s modulus of bacteriophage φ29 capsids was measured to be 1.8 GPa, which is comparable to that of hard plastic particles.125 These capsids showed remarkable elasticity and function as high pressure containers storing energy for viral DNA injection. Later, the internal pressure of the capsid was estimated to be ~40 atm.126 In another study, measurements of the mechanical properties of HIV particles estimated that immature particles are more than 14-fold stiffer than mature particles.127 The change in mechanical properties was correlated with the infection process and the ability of infectious viruses to enter cells. In a subsequent study, this change in stiffness was found to be regulated by a cytoplasmic tail domain.128 Quantification of the swelling of CCMV capsids in response to pH changes and measurement of their Young’s modulus suggested that cells became softer as the capsids swelled.129 Nanoindentation experiments on the dimorphic HBV showed that empty T = 3 and T = 4 HBV capsids have indistinguishable mechanical properties.130

The presence of the viral genome affects the mechanical properties of virus capsids. CCMV capsids filled with DNA were found to be more resistant to indentation.131 In the same work, the capsid strength increased due to a single point mutation of the CCMV’s core protein. An AFM study of icosahedral MVM capsids showed that the presence of DNA inside these virions changes the mechanical properties of the capsids anisotropically.132 Although the stiffness of empty capsids was isotropically distributed along all symmetry axes, the presence of DNA resulted in an anistropic increase in stiffness of 3%, 42%, and 140% along the 5-, 3-, and 2-fold symmetry axes, respectively. These differences were attributed to the orientation of DNA bound in the MVM capsids. In a study on herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV1), Roos, Wuite, and coworkers observed the presence of DNA did not change the mechanical properties of the capsids.133 On the contrary, capsids that contained scaffold proteins were significantly more fragile than empty and DNA-filled capsids. Furthermore, this study showed capsids that are missing pentameric units can still be imaged and indented. Nanoindentation studies on avian infectious bursal disease virus (IBDV) showed a direct correlation between the ribonucleoproteins and rigidity of the virus capsids.134 In another study, the genetic content of adeno-associated virus (AAV) capsids was determined based on their mechanical properties.135 A multivariate conditional probability approach used the height, rupture force, and elastic constant as parameters. In the same study, orientation toward the 2-fold symmetry axis was preferred upon adsorption. This orientation bias that generally affects the measurement of the mechanical properties was attributed to the morphology and hydrophobicity of the 2-fold sites.

To study genome release, virus disassembly was triggered and analyzed by AFM. The AFM tip initiated disassembly of the ssRNA filled triatoma virus (TrV) capsids, and images of the virus fragments showed that the virus split into pentamers.136 The same pentameric fragments were observed when disassembly was induced at high pH. The disassembly of the dsDNA human adenovirus was also triggered by an AFM.137 In those experiments, the release of the DNA was studied with fluorescence microscopy; YOYO-1 dye molecules present in the solution fluoresced after binding with the released DNA (Figure 6c,d).

Understanding the mechanical properties of viruses enhances our ability to manipulate them by altering interactions among chemical groups. Softer MVM VLPs were designed by one site-directed mutagenesis based on a simple mechanical model.138 Also, binding of proteins in or on the virus capsid significantly changed its mechanical stability.139–140 Studying bacteriophage P22 VLPs, Douglas and coworkers showed the loss of pentons during the transition from expanded to whiffle-ball P22 capsids had a dramatic impact on the mechanical and chemical stability of the 2-fold and 3-fold symmetry axes (Figure 6e–g).141 Interestingly, the stability of the virus recovered after addition of decorating proteins, which bound adjacent to the fracture points of the virus.

Theoretical Models.

Development of theoretical models quickly followed measurements of the mechanical properties of virus capsids by AFM. Simple elastic shell approximations, continuum models, and models based on coarse-grain molecular dynamics have been developed.142–145 Although theoretical approaches are not discussed further here, these proposed models take into account the adhesion of the virus capsids onto the substrate,146–147 geometry of the substrate,146 and geometry of the AFM tip.148

SEPARATION TECHNIQUES

Flow analysis techniques that can achieve physical separation of virus particles are advantageous for multiple reasons. The physical separation of protein monomers, fully formed virus capsids, and bigger protein aggregates allows straightforward quantification with optical detection. Also, separation techniques are critical for fractionation of capsid particles of various sizes and purification of capsids from sample impurities. However, in contrast to the power of high performance liquid chromatography for the analysis of small molecules, existing separation instrumentation for the analysis of particles with dimensions in the nanoscale lacks sufficient resolution. In addition, because separation methods require time for the separation to take place, they are inherently not suitable for real-time measurements of virus assembly.

Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC).

SEC separates particles based on a size-dependent mechanism. Particles travel through a column with a porous stationary phase and their retention time depends on their hydrodynamic volume. Specifically, particles with larger hydrodynamic volume are generally excluded and elute earlier.149–150 The first separation of biomolecules with SEC was reported in 1955, when Lindqvist and Storgårds separated peptides from amino acids.151 Because virus capsids are some of the very few platonic solids in nature (e.g., biomolecules with well-defined geometrical shapes), several viruses were used as calibration standards in theoretical studies of the SEC separation mechanism.152 In that work, the elution times of spherical viruses (i.e., tomato bushy stunt virus, turnip yellow mosaic virus) and rod-shaped viruses (tobacco mosaic virus) were measured and further analyzed.

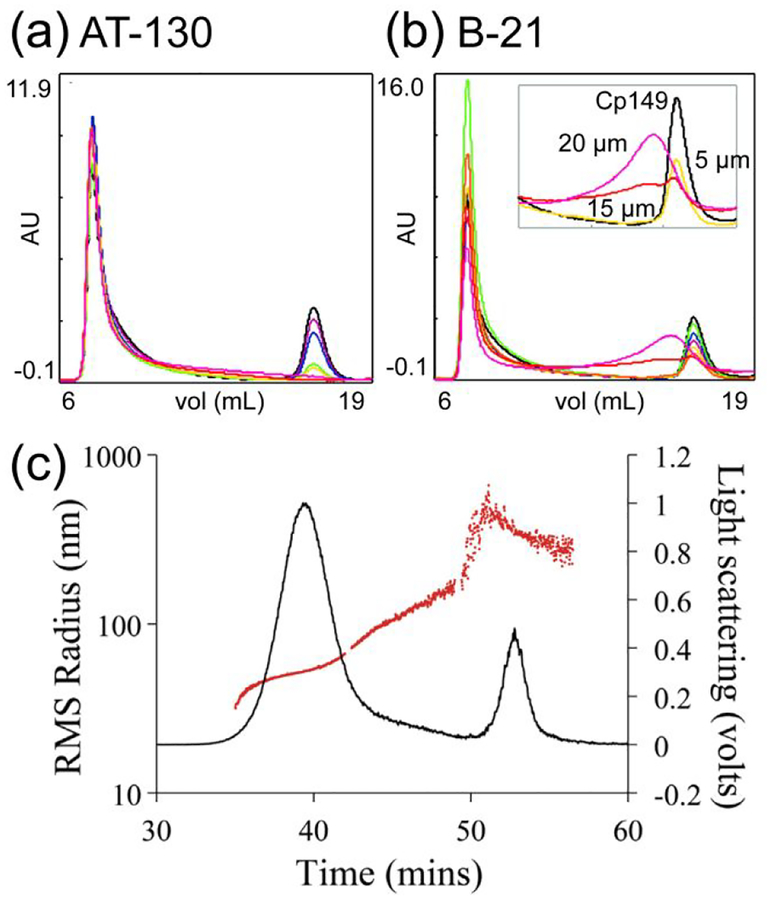

Although this early work did not bring significant attention, SEC played a significant role in one of the first thermodynamic studies of the HBV capsid assembly.153 In these experiments, the fully formed virus capsids were eluted in the void volume, whereas the single protein subunits (dimers of HBV core protein) and the early intermediates were retained in the chromatographic column and eluted later. The ability to separate and quantify with UV detection the amount of fully-formed capsids and unassembled protein dimers in equilibrium led to determining thermodynamic parameters of HBV assembly. In more recent work, early, kinetically trapped assembly intermediates were isolated from capsids and dimer by SEC (Figure 7a,b).14 These intermediates were observed in the presence of the phenylpropenamide derivative B-21, but not in the presence of AT-130. Both B-21 and AT-130 were found to significantly increase the extent of HBV assembly.

Figure 7.

Size exclusion chromatography and field-flow fractionation. Size exclusion chromatograms of HBV assembly reactions with 5 μM dimer in 500 mM NaCl in the presence of various concentrations of (a) AT-130, and (b) B-21 phenylpropenamide derivatives. Increasing the concentration of phenylpropenamides from 0 to 20 μM increases the extent of HBV assembly. For assembly with B-21, the expanded view (inset in panel b) shows peaks that correspond to intermediate species. Reproduced from Katen, S. P.; Chirapu, S. R.; Finn, M. G.; Zlotnick, A., ACS Chem. Biol. 2010, 5, 1125–1136 (ref.14). Copyright 2010 American Chemical Society. (c) Field flow fractionation-multi-angle light scattering (FFF-MALS) fractogram of influenza PR8 virus. The black trace shows the light scattering signal at 90°, and the red trace shows the RMS radius of the particles. The first peak, eluted between 35 and 42 min, corresponds to virus particles, whereas the second peak, eluted between 49 and 56 min, corresponds to virus aggregates. Reprinted from J. Virol. Methods, Vol. 193, Bousse, T.; Shore, D. A.; Goldsmith, C. S.; Hossain, M. J.; Jang, Y.; Davis, C. T.; Donis, R. O.; Stevens, J. Quantitation of influenza virus using field flow fractionation and multi-angle light scattering for quantifying influenza A particles, pp. 589–596 (ref. 167). Copyright 2013, with permission from Elsevier.

SEC has also been used for biopharmaceutical and purification applications. On SEC systems, several research groups have performed quality control experiments of various VLPs interesting for potential pharmaceutical applications (i.e., development of vaccines).19,154–156 In addition, SEC methods are powerful tools for purifying cell-cultured viruses by separating them from other cell proteins.157 For better purification of cell culture-derived influenza A and B viruses, SEC removed host cell proteins, and anion exchange chromatography eliminated DNA.158–159 To improve throughput of SEC as a purification tool, two size exclusion columns, based on simulated moving bed (SMB) designs, were used to purify influenza virus160 and adenovirus sterotype 5.161–162

Field Flow Fractionation (FFF).

Giddings developed FFF in the 1960s.163 The separation is based on the parabolic flow profile in thin channels with a force applied perpendicularly to the flow and depends on the type and magnitude of applied force and the chemical and physical properties of the particles. The first report of FFF application for the characterization of virus capsids belongs to Giddings and coworkers,164 in which, FFF determined the diffusion coefficients of bacteriophages Qβ, MS2, f2, and φX174, and baseline separated the bacteriophages Qβ and P22.

Following development of SEC methods for characterizing virus capsids, methods based on FFF were reported for the analysis of influenza virions,165–167 murine polyomavirus (MPV) particles,168 and adenovirus.166 In all these experiments, the FFF separation was followed by multi-angle light scattering (MALS) detection, which allowed the determination of particle size (root mean square radius or radius of gyration). Figure 7c illustrates a typical FFF-MALS fractogram where influenza virions were successfully resolved from larger aggregates.167 Assembly of VLPs around desired DNA strands, and then, their triggered disassembly was studied by FFF coupled with a MALS detector.169 The purpose of this study was development of virus-based genome-delivery systems. In other studies, FFF coupled with UV detection was used to purify infectious bacteriophage PRD1 virions and to quantify PRD1 virus production in infected cells.170 More recently, four halophilic, infectious viruses with very different, distinct morphologies were successfully purified by FFF.171

OTHER ANALYTICAL INSTRUMENTATION

In addition to the techniques discussed above, X-ray crystallography,172 small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS),173 solid-state NMR,174 and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC)175 have contributed to our understanding of virus capsids. Although, these techniques are not reviewed in depth here, their importance is briefly described. X-ray crystallography, similar to cryo-EM, is used to determine the 3D structure of viruses. However, in contrast to cryo-EM, X-ray crystallography requires crystallization of the virus capsids. In SAXS, 2D plots of the intensity versus the magnitude of the scattering vector, q, are fitted by models to reveal information about the 3D structures. Solid-state NMR complements structural data from cryo-EM and X-ray crystallography, especially when sample heterogeneity prevents near-atomic resolution image reconstruction. Lastly, thermal induced dissociation of capsids has been studied with DSC.

CONCLUSION AND OUTLOOK

Analytical methods have been developed to characterize the structure and fundamental properties of virus capsids. Optical methods offer excellent temporal resolution, MS measures mass directly, resistive-pulse sensing tracks virus assembly with high size resolution, EM displays unique morphological information, AFM extracts mechanical properties of virus capsids, and separation methods fractionate capsid. The challenge in the future is not only to further improve existing analytical instrumentation but also to assimilate all the complementary information generated by these various techniques. Combining all sources of information enhances our current understanding of viruses and their fundamental properties and leads to their effective manipulation.

Acknowledgments.

This work was supported in part by NIH R01 GM129354.

Biographies

Panagiotis Kondylis received a B.S. in chemistry from National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece in 2013 and a Ph.D. in chemistry with a concentration in analytical chemistry from Indiana University, Bloomington in 2018. During his graduate studies, he was a member of the Jacobson Research Group and worked on developing nanofluidic devices for the analysis of hepatitis B virus capsid assembly in the presence of antivirals.

Christopher J. Schlicksup is a graduate student in the Department of Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry at Indiana University. He received his B.S. and M.S. degrees in Biology and Biotechnology, also from Indiana University. His current focus is the structural biology of hepatitis B virus capsids, with an emphasis on how the capsid responds to the presence of antiviral molecules.

Adam Zlotnick is a Professor of Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry at Indiana University. He received his B.A. from the University of Virginia and Ph.D. from Purdue University under the supervision of Jack Johnson. He was subsequently a postdoctoral fellow at the National Institutes of Health, followed by a faculty appointment at the University of Oklahoma. He has been at Indiana University since 2008. Professor Zlotnick has a long-standing interest in virus structure and the molecular mechanisms for virus capsid assembly.

Stephen C. Jacobson is a Professor of Chemistry and holds the Dorothy & Edward Bair Chair in Chemistry at Indiana University. He received a B.S. in mathematics from Georgetown University in 1988 and a Ph.D. in chemistry from the University of Tennessee in 1992. After graduate school, Stephen was awarded an Alexander Hollaender Distinguished Postdoctoral Fellowship at Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL), and in 1995, he became a research staff member at ORNL. In 2003, Stephen joined the faculty in the Department of Chemistry at Indiana University. Stephen and his research group are currently working in the areas of microfluidic separations, nanofluidic transport, cancer screening, virus sensing and assembly, and bacterial adhesion, development, and aging.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest. The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): A.Z. reports a financial interest in a company that develops core protein allosteric modulators (CpAMs).

References

- (1).Caspar DLD; Klug A Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol 1962, 27, 1–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Perlmutter JD; Hagan MF Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem 2015, 66, 217–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Zlotnick A J Mol. Biol 1994, 241, 59–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Zlotnick A; Johnson JM; Wingfield PW; Stahl SJ; Endres D Biochemistry 1999, 38, 14644–14652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Zhang TQ; Schwartz R Biophys. J 2006, 90, 57–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Hagan MF, in Adv. Chem. Phys: Vol. 155 John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2014, pp 1–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Deres K, et al. Science 2003, 299, 893–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Pei YM; Wang CT; Yan SF; Liu GJ Med. Chem 2017, 60, 6461–6479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Douglas T; Young M Science 2006, 312, 873–875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Jordan PC; Patterson DP; Saboda KN; Edwards EJ; Miettinen HM; Basu G; Thielges MC; Douglas T Nat. Chem 2016, 8, 179–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Dragnea B ACS Nano 2017, 11, 3433–3437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Prevelige PE; Thomas D; King J Biophys. J 1993, 64, 824–835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Stray SJ; Bourne CR; Punna S; Lewis WG; Finn MG; Zlotnick A Proc. Nall. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2005, 102, 8138–8143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Katen SP; Chirapu SR; Finn MG; Zlotnick A ACS Chem. Biol 2010, 5 1125–1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Zlotnick A; Aldrich R; Johnson JM; Ceres P; Young MJ Virology 2000, 277, 450–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Casini GL; Graham D; Heine D; Garcea RL; Wu DT Virology 2004, 325, 320–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Chen C; Kao CC; Dragnea BJ Phys. Chem. A 2008, 112, 9405–9412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Muller B; Anders M; Reinstein J PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e99504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Steppert P; Burgstallera D; Klausberger M; Tover A; Berger E; Jungbauer AJ Chromatogr. A 2017, 1487, 89–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Makra I; Terejanszky P; Gyurcsanyi RE Methodsx 2015, 2, 91–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Sun J; DuFort C; Daniel MC; Murali A; Chen C; Gopinath K; Stein B; De M; Rotello VM; Holzenburg A; Kao CC; Dragnea B Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2007, 104, 1354–1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Wu CY; Yeh YC; Yang YC; Chou C; Liu MT; Wu HS; Chan JT; Hsiao PW PLoS ONE 2010, 5 e9784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Matilde L; Elias Nelson R; Yadira L; Alexis M; Viviana F; Gerardo G; Julio CA Adv. Nat. Sci: Nanosci. Nanotechnol 2017, 8, 025009. [Google Scholar]

- (24).Serriere J; Fenel D; Schoehn G; Gouet P; Guillon C PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e56424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Vamseedhar R; Alan M; Joseph Che-Yen W; Boon Chong G; Juan RP; Adam Z; Suchetana MJ Phys. Condens. M atter 2017, 29, 484003. [Google Scholar]

- (26).Filipe V; Hawe A; Jiskoot W Pharm. Res 2010, 27, 796–810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Kramberger P; Ciringer M; Strancar A; Peterka M Virol. J 2012, 9, 265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Gross J; Sayle S; Karow AR; Bakowsky U; Garidel P Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm 2016, 104, 30–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Faez S; Lahini Y; Weidlich S; Garmann RF; Wondraczek K; Zeisberger M; Schmidt MA; Orrit M; Manoharan VN ACS Nan? 2015, 9, 12349–12357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Garmann RF; Goldfain AM; Manoharan VN 2018, arXiv:1802.05211 [cond-mat.soft] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Banerjee S; Maurya S; Roy R J Biosci 2018, 43, 519–540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Parveen N; Borrenberghs D; Rocha S; Hendrix J Vruses 2018, 10, 250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Sabanayagam CR; Oram M; Lakowicz JR; Black LW Biophys. J 2007, 93, L17–L19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Borodavka A; Tuma R; Stockley PG Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2012, 109, 15769–15774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Patel N; Wroblewski E; Leonov G; Phillips SEV; Tuma R; Twarock R; Stockley PG Proc. Nat! Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2017, 114, 12255–12260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Yamashita M; Fenn JB J Phys. Chem 1984, 88, 4451–4459. [Google Scholar]

- (37).Tanaka K; Waki H; Ido Y; Akita S; Yoshida Y; Yoshida T; Matsuo T Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom 1988, 2, 151–153. [Google Scholar]

- (38).Leney AC; Heck AJ R. J Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 2017, 28, 5–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Erba EB; Petosa C Protein Sci 2015, 24, 1176–1192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Lossl P; Snijder J; Heck AJ R. J Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 2014, 25, 906–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Siuzdak G; Bothner B; Yeager M; Brugidou C; Fauquet CM; Hoey K; Chang CM Chem. Bioi 1996, 3, 45–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Tito MA; Tars K; Valegard K; Hajdu J; Robinson CV J Am. Chem. Soc 2000, 122, 3550–3551. [Google Scholar]

- (43).Uetrecht C; Barbu IM; Shoemaker GK; van Duijn E; Heck AJ R. Nat. Chem 2011, 3, 126–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Shepherd DA; Holmes K; Rowlands DJ; Stonehouse NJ; Ashcroft AE Biophys. J 2013, 105, 1258–1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Weiss VU; Bereszcazk JZ; Havlik M; Kallinger P; Gosler I; Kumar M; Blaas D; Marchetti-Deschmann M; Heck AJR; Szymanski WW; Allmaier G Anal. Chem 2015, 87, 8709–8717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Fuerstenau SD; Benner WH; Thomas JJ; Brugidou C; Bothner B; Siuzdak G Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2001, 40, 542–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Keifer DZ; Jarrold MF Mass Spectrom. Rev 2017, 36, 715–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Keifer DZ; Motwani T; Teschke CM; Jarrold MF J Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 2016, 27, 1028–1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Uetrecht C; Barbu IM; Shoemaker GK; van Duijn E; Heck AJ R. Nat. Spectrom 2016, 30, 1957–1962. [Google Scholar]

- (50).Pierson EE; Keifer DZ; Selzer L; Lee LS; Contino NC; Wang JCY; Zlotnick A; Jarrold MF J Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 3536–3541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Lutomski CA; Lyktey NA; Zhao ZC; Pierson EE; Zlotnick A; Jarrold MF J Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 16932–16938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Lutomski CA; Lyktey NA; Pierson EE; Zhao Z; Zlotnick A; Jarrold MF Journal of the American Chemical Society 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Guttman M; Lee KK Methods Enzymo 2016, 566, 405–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Zhang Z; Smith DL Protein Sci 1993, 2 522–531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Lanman J; Lam TT; Emmett MR; Marshall AG; Sakalian M; Prevelige PE Jr Nat. Struct. Mol Bio 2004, 11, 676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Tuma R; Coward LU; Kirk MC; Barnes S; Prevelige PE J. Mol. Biol 2001, 306, 389–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Gertsman I; Gan L; Guttman M; Lee K; Speir JA; Duda RL; Hendrix RW; Komives EA; Johnson JE Nature 2009, 458, 646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Domitrovic T; Movahed N; Bothner B; Matsui T; Wang Q; Doerschuk PC; Johnson JE J MoI. Bio 2013, 425, 1488–1496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Bereszczak JZ; Rose RJ; van Duijn E; Watts NR; Wingfield PT; Steven AC; Heck AJ R. J Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 6504–6512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).van de Waterbeemd M; Llauro A; Snijder J; Valbuena A; Rodriguez-Huete A; Fuertes MA; de Pablo PJ; Mateu MG; Heck AJ R. Biophysical J 2017, 112, 1157–1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Harms ZD; Haywood DG; Kneller AR; Jacobson SC Analyst 2015, 140, 4779–4791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Coulter WH Proceedings of the National Electronics Conference 1956. [Google Scholar]

- (63).Deblois RW; Uzgiris EE; Cluxton DH; Mazzone HM Ana. Biochem 1978, 90, 273–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).DeBlois RW; Wesley RK A. J Virol 1977, 23, 227–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Kozak D; Anderson W; Vogel R; Trau M Nano Today 2011, 6, 531–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Haywood DG; Saha-Shah A; Baker LA; Jacobson SC Ana. Chem 2015, 87, 172–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Yang L; Yamamoto T Front Microbiol 2016, 7, 1500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Uram JD; Ke K; Hunt AJ; Mayer M Small 2006, 2, 967–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (69).Uram JD; Ke K; Mayer M ACS Nano 2008, 2, 857–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (70).Zhou K; Li L; Tan Z; Zlotnick A; Jacobson SC J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133, 1618–1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (71).Arjmandi N; Van Roy W; Lagae L Anal. Chem 2014, 86, 4637–4641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (72).McMullen A; de Haan HW; Tang JX; Stein D Nat. Comm 2014, 5 4171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (73).McMullen AJ; Tang JX; Stein D ACS Nano 2017, 11, 11669–11677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (74).Weatherall E; Willmott GR Analyst 2015, 140, 3318–3334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (75).Blundell E; Mayne LJ; Billinge ER; Platt M Anal. Methods 2015, 7 7055–7066. [Google Scholar]

- (76).Farkas K; Pang LP; Lin S; Williamson W; Easingwood R; Fredericks R; Jaffer MA; Varsani A Food Environ Virol 2013, 5, 231–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (77).Akpinar F; Yin J J Virol. Methods 2015, 218, 71–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (78).Gutierrez-Granados S; Cervera L; Segura MD; Wolfel J; Godia F Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnoi 2016, 100, 3935–3947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (79).Heider S; Muzard J; Zaruba M; Metzner C Mol. Biotechnoi 2017, 59, 251–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (80).Kondylis P; Zhou J; Harms ZD; Kneller AR; Lee L; Zlotnick A; Jacobson SC Anal. Chem 2017, 89, 4855–4862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (81).Harms ZD; Mogensen KB; Nunes PS; Zhou K; Hildenbrand BW; Mitra I; Tan Z; Zlotnick A; Kutter JP; Jacobson SC Anal. Chem 2011, 83, 9573–9578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (82).Harms ZD; Haywood DG; Kneller AR; Selzer L; Zlotnick A; Jacobson SC Anal. Chem 2015, 87, 699–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (83).Harms ZD; Selzer L; Zlotnick A; Jacobson SC ACS Nano 2015, 9, 9087–9096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (84).Zhou J; Kondylis P; Haywood DG; Harms ZD; Lee LS; Zlotnick A; Jacobson SC Anal. Chem 2018, 90, 7267–7274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (85).Li CL; Kneller AR; Jacobson SC; Zlotnick A ACS Chem. Biol 2017, 12, 1327–1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (86).Kondylis P; Schlicksup CJ; Brunk NE; Zhou J; Zlotnick A; Jacobson SC J Am. Chem. Soc Submitted, ja-2018–10131e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (87).Fraikin JL; Teesalu T; McKenney CM; Ruoslahti E; Cleland AN Nat. Nanotechnoi 2011, 6, 308–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (88).Hazelton PR; Gelderblom HR Emerg. Infect. Dis 2003, 9, 294–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (89).Goldsmith CS, et al. Emerg. Infect. Dis 2013, 19, 886–891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (90).Malenovska H J Viroi. Methods 2013, 191, 136–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (91).Rossi CA; Kearney BJ; Olschner SP; Williams PL; Robinson CG; Heinrich ML; Zovanyi AM; Ingram MF; Norwood DA; Schoepp RJ Viruses 2015, 7 857–872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (92).Blancett CD; Fetterer DP; Koistinen KA; Morazzani EM; Monninger MK; Piper AE; Kuehl KA; Kearney BJ; Norris SL; Rossi CA; Glass PJ; Sun MG J Viroi. Methods 2017, 248, 136–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (93).Kaelber JT; Hryc CF; Chiu W Annu. Rev. Viroi 2017, 4, 287–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (94).Adrian M; Dubochet J; Lepault J; McDowall AW Nature 1984, 308, 32–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (95).Earl LA; Subramaniam S Proc. Nati. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2016, 113, 8903–8905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (96).Zhang X; Settembre E; Xu C; Dormitzer PR; Bellamy R; Harrison SC; Grigorieff N Proc. Nati. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2008, 105, 1867–1872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (97).Yu XK; Jin L; Zhou ZH Nature 2008, 453, 415–U73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (98).DiMaio F; Yu X; Rensen E; Krupovic M; Prangishvili D; Egelman EH Science 2015, 348, 914–917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (99).Liu J; Bartesaghi A; Borgnia MJ; Sapiro G; Subramaniam S Nature 2008, 455, 109–U76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (100).Liu Y; Hill MG; Klose T; Chen ZG; Watters K; Bochkov YA; Jiang W; Palmenberg AC; Rossmann MG Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2016, 113,8997–9002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (101).Sirohi D; Chen Z; Sun L; Klose T; Pierson TC; Rossmann MG; Kuhn RJ Science 2016, 352, 467–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (102).Zhao QJ; Potter CS; Carragher B; Lander G; Sworen J; Towne V; Abraham D; Duncan P; Washabaugh MW; Sitrin RD Hum. Vaccin. ímmunother 2014, 10, 734–739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (103).Li LC; Chirapu SR; Finn MG; Zlotnick A Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2013, 57, 1505–1508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (104).Bourne CR; Finn MG; Zlotnick AJ Virol 2006, 80, 11055–11061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]