Abstract

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are currently being tested in several clinical trials. Mitochondria regulate many aspects of MSC function. Mitochondrial preproteins are rapidly translated and trafficked into the mitochondrion for assembly in their final destination, but whether coexisting cardiovascular risk factors modulate this process is unknown. We hypothesized that metabolic syndrome (MetS) modulates mitochondrial protein import in porcine MSCs. MSCs were isolated from porcine abdominal adipose tissue after 16 weeks of Lean or MetS diet (n=5 each). RNA-sequencing was performed and differentially expressed mitochondrial mRNAs and microRNAs were identified and validated. Protein expression of transporters of mitochondrial proteins (presequences and precursors) and their respective substrates were measured. Mitochondrial homeostasis was assessed by Western blot and function by cytochrome-c oxidase-IV activity. Forty-five mitochondrial mRNAs were upregulated and 25 downregulated in MetS-MSCs compared to Lean-MSCs. mRNAs upregulated in MetS-MSCs encoded for precursor proteins, whereas those downregulated encoded for presequences. Micro-RNAs upregulated in MetS-MSCs primarily target mRNAs encoding for presequences. Transporters of precursor proteins and their substrates were also upregulated, associated with changes in mitochondrial homeostasis and dysfunction. MetS interferes with mitochondrial protein import, favoring upregulation of precursor proteins, which might be linked to post-transcriptional regulation of presequences. This in turn alters mitochondrial homeostasis and impairs energy production. Our observations highlight the importance of mitochondria in MSC function and provide a molecular framework for optimization of cell-based strategies as we move towards their clinical application.

Keywords: Stem Cells, Mitochondria, Metabolic Syndrome, Protein Import, RNAseq

Introduction

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are non-embryonic stem cells regarded as essential components of our endogenous repair system, because of their pro-angiogenic, immunomodulatory, and tissue-trophic properties, and their ability to differentiate into a broad spectrum of cell types [1]. Furthermore, MSCs can be easily isolated from several tissues, including adipose tissue, which make them excellent therapeutic candidates for a wide range of chronic diseases. Indeed, accumulating experimental evidence and emerging clinical data indicate that MSC therapy is safe and effective for treating a myriad of disease conditions [2]. Nonetheless, cardiovascular risk factors may impair the regenerative capacity and function of MSCs, in turn having significant implications for their endogenous repair ability and exogenous delivery in patients with cardiovascular disease [3, 4].

Many aspects of MSC biology and function are highly regulated by mitochondria, double-membrane-organelles that produce cellular energy and are intimately involved in several cellular functions, including proliferation, survival, apoptosis, redox signaling, and calcium homeostasis [5]. Recent studies have shown that metabolic syndrome (MetS) induces changes in MSC mitochondria, limiting their viability and differentiation potential. MetS induces mitochondrial structural damage and changes in mitophagy of equine adipose tissue-derived MSCs, which are associated with impaired proliferation, chondrogenic, and osteogenic differentiation [6–8]. However, the mechanisms triggering MSC mitochondrial damage in MetS remain unknown.

Despite having small amount of their own DNA, the vast majority of mitochondrial proteins are encoded in the cellular nucleus, transcribed into mRNAs, and subsequently translated into preproteins in the vicinity of the mitochondrion [9]. Mitochondrial preproteins are then rapidly trafficked into the confines of the organelle through sophisticated machineries for recognition, translocation, and assembly [10].

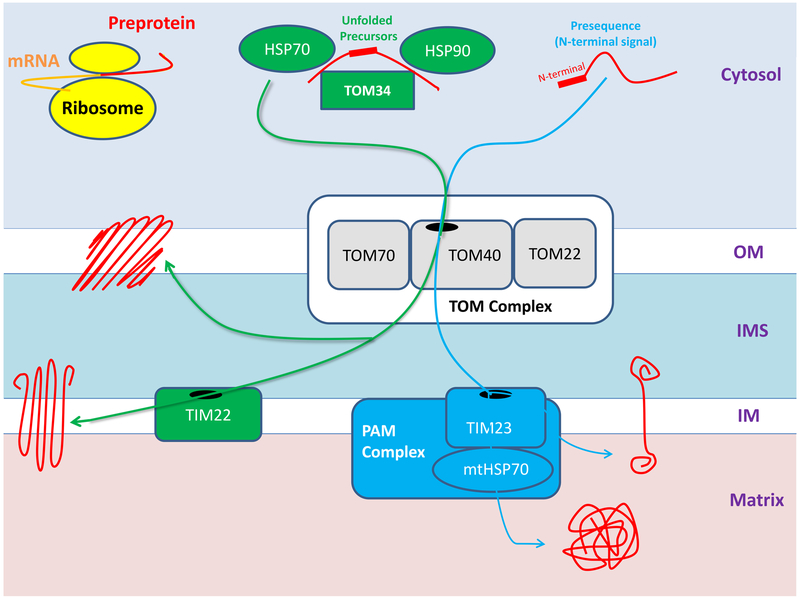

The final destination of these preproteins is determined by specific localization signals within their sequences. Mitochondrial preproteins can be classified as presequences, which possess a cleavable N-terminal signaling extension, or precursor proteins, which contain internal targeting signals. Presequences are destined for the mitochondrial matrix and inner membrane proteins, whereas precursors include all outer membrane proteins, as well as inner membrane proteins [11]. Although almost all mitochondrial preproteins are imported through a common β-barrel channel complex, presequences and precursors utilize distinct molecular mechanisms of import to reach their final destinations (Figure 1). This system plays a critical role in orchestrating mitochondrial function. Therefore, defective import of mitochondrial proteins might have important pathologic implications.

Figure 1.

Mitochondrial protein import pathways (2-column colored image)

Most mitochondrial proteins are synthesized as preproteins in cytosolic ribosomes in the vicinity of mitochondira. Precursor proteins (green) contain an integral signaling sequence which determines their final destination in the mitochondrial outer or inner mitochondrial membranes. In contrast, presequence proteins (blue) have an N-terminal sequence and will reside in the inner mitochondrial membrane or the mitochondrial matrix. Almost all mitochondrial proteins pass through the common translocase of outer mitochondrial membrane (TOM complex), including TOM40, TOM70, and TOM22. However, precursor and presequence proteins use distinct transporters to reach their final destination. Cytosolic chaperones (HSP70, HSP90 and TOM34) keep precursor proteins in an unfolded conformation in the cytosol, which will be subsequently imported and integrated in the outer membrane or assembled in the inner mitochondrial membrane by TIM22. Contrarily, presequence proteins are assembled in the inner membrane by TIM23 or transferred to the matrix through the mtHSP70.

We hypothesized that cardiovascular risk factors modulate import of nuclear-encoded mitochondrial proteins into the MSC mitochondria, altering mitochondrial homeostasis and function. To explore this, we took advantage of a novel porcine model of MetS that recapitulates many features of the human disease, including obesity, spontaneous hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and insulin resistance [12]. We utilized an unbiased and integrated approach (mRNA and micro-RNA sequencing, and Western blotting analysis of mitochondrial transporters and their substrates) to compare the mitochondria-related transcriptome and protein transport signature between Lean- and MetS- adipose tissue-derived MSCs.

Material and methods

Experimental animal groups

All experiments were approved by the Mayo Clinic Animal Care and Use Committee. Ten 3-month-old female domestic pigs were fed a high-fat/high-fructose diet (5B4L; Purina) containing (% kcal) 17% protein, 20% fructose, 20% complex carbohydrates, and 43% fat (lard, hydrogenated soybean and coconut oils), supplemented with 2% cholesterol and 0.7% sodium cholate by weight [12] or standard pig chow for a total of 16 weeks (n = 5 each). At the end of the study, body weight, blood pressure, glucose panel, and cholesterol fractions were obtained, and animals euthanized with sodium pentobarbital (100mg/kg iv, Fatal Plus, Vortech Pharmaceuticals, Dearborn, MI).

MSC isolation, characterization, and culture

Cells were collected from subcutaneous abdominal fat (5–10g) using collagenase-H, and cultured for 3 weeks in advanced MEM medium (Gibco/Invitrogen) supplemented with 5% platelet lysate PLTmax, Mill Creek Life Sciences, Rochester, MN). MSCs were characterized by fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis to determine cellular phenotype for the MSC markers CD90 (abcam, ab124527) and CD105 (abcam, ab53321), as previously shown [13]. In addition, we tested that our adipose MSCs were negative for the progenitor cell marker CD34 (BD Biosciences, 340441) and the common leukocyte marker CD45 (Biolegend, 304014). The third passage was collected and kept in Gibco Cell Culture Freezing Medium for subsequent studies.

RNA sequencing analysis

mRNA sequencing analysis was performed at the Mayo Clinic Genome Analysis Core as previously described [14]. Sequencing RNA libraries were prepared (TruSeq RNA Sample Prep Kit v2, Illumina) and loaded onto flow cells (8–10pM) to generate cluster densities of 700,000/mm2 following the standard protocol for the Illumina cBot and cBot Paired-end cluster kit version-3. MSCs were sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2000 using TruSeq SBS kit version-3 and HCS v2.0.12, and data analyzed using the MAPRSeq v.1.2.1, TopHat 2.0.6, and featureCounts software. mRNA expression was normalized to 1 million reads, corrected for gene length, and expressed as reads per kilobasepair per million mapped reads (RPKM). Genes with RPKM>0.1, fold-change (MetS-MSCs/Lean-MSCs)>1.4 and p values<0.05 (Lean-MSCs vs. MetS-MSCs, Student’s t-test) were considered upregulated in MetS-MSCs. Genes with RPKM>0.1 and fold-change (MetS-MSCs/Lean-MSCs)<0.7 were considered downregulated in MetS-MSCs. All mapped transcripts were filtered by MitoCarta 2.0, an online inventory of mammalian mitochondrial genes [15].

MicroRNA sequencing analysis was performed as previously described, and data analyzed using the CAP-miRSeq-v1.1. Unaligned FASTQs were used to generate aligned BAMs, raw and normalized known mature microRNA expression counts, and predicted novel microRNAs and single-nucleotide variants. MicroRNAs were expressed as normalized total reads. Differential expression analysis was performed with edgeR2.6.2. MicroRNAs with fold-change (MetS-MSCs/Lean-MSCs)>1.4 were considered upregulated in MetS-MSCs. Micro-RNAs with foldchange (MetS-MSCs/Lean-MSCs)<0.7 were considered downregulated in MetS-MSCs. TargetScan 7.1 and [16] and ComiR [17] were used to identify genes targeted by micro-RNAs upregulated in MetS-MSCs, and mapped microRNA target genes were filtered by MitoCarta.

Validation of RNA sequencing analysis

To validate RNA sequencing results, we measured expression of randomly selected mRNAs and micro-RNAs, using quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR, n=5 replicates each). Total RNA was extracted from 5×10^5 −1×10^6 MSC samples by the mirVana PARIS RNA isolation kit (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA, Cat# AM1556). RNA concentrations were measured by a NanoDrop Spectrophotometer (NanoDrop, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). A fixed volume of 5μL of RNA elute at 1ng/uL was reverse transcribed by using the TaqMan MicroRNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Life Technologies, Cat# 4366596). For PCR, 1.33μL of RT product was combined with 10μL of TaqMan Universal Master Mix (Cat# 4440038), 7.67μL of H2O and 1μL of primers, including PDP1, OXCT1, GLDC, HOGA1, DHRS4, MRPL54, ssc-miR-196a, ssc-miR-let-7c, ssc-miR-27-b, ssc-miR-148a-3p, ssc-miR-345–3p, and ssc-miR-542–3p (ThermoFisher Scientific, Cat# ss04955277, ss3392870, APYMJVM, Ss04247094, Ss03391281, APNKUK, 000495, 000379, 432757, PN4427975, PN440885, PN4427975, respectively) to make up a 20μL reaction. RNU6B (Life Technology Cat# 001093) was included in the assay as reference control. Real-time qPCR was carried out on an Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA, USA) ViiA7 Real-Time qPCR system at 50°C for 2min, 95°C for 10min and 40 cycles of 95°C for 15sec and 60°C for 1min [18].

Western Blotting

Standard Western blotting protocols were performed using cell lysates from Lean- and MetS-MSCs, as previously described [19]. In brief, chilled protein extraction buffer was used for immunoblotting against specific antibodies that cross-react with swine tissue. After lysate centrifugation, the supernatant was removed, and the protein concentration determined using spectrophotometry. The lysate was diluted (polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis sample buffer), sonicated, heated, and loaded onto a gel to run with specific antibodies against HSP70, HSP90, TOM34, PGC-1α, and BNIP-3 (Abcam, Catalog#: ab5439, ab59459, ab103585, ab54481, and Bioss, Catalog#bs-4239R, respectively). Protein concentration was measured using BCA kit and BSA standard curve. Western blotting analysis was carried out in a well membrane (Criterion™ Precast, 4–15% Tris-HCl 1.0mm) from Bio Rad (Hercules, California). Lean- and MetS-MSC samples (n=5 each) were run on the same membrane and exposed together. Data was analyzed using Carestream Molecular Imaging Software (version 5.0.720).

In addition, mitochondria were isolated using MITO-ISO kit (Catalog#: 8268; ScienCell) [20], and protein expression of TOM70 (ThermoFisher, Catalog#: PA5–25910), SLC25A4 (Invitrogen, Catalog#: 455800), as well as TOM40, TOM22, TIM23, TIM22, mtHsp70, OXCT1, and PDP1 (Abcam, Catalog#: ab99485, ab57523, ab116329, ab167423, ab52603, ab105320, and ab198261, respectively) were assessed by western blotting (n=5 each). Lastly, cytochrome-c oxidase (COX)-IV activity was assessed by fluorometric methods (Abnova Cat# KA3950).

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range). Parametric (Student’s t-test) and non-parametric (Kruskal Wallis) tests were used when appropriate, and statistical significance was accepted if p≤0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using JMP 10.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Systemic characteristics of study groups

After 16 weeks of feeding, body weight, mean blood pressure, lipid fractions, fasting insulin, and homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) levels were higher in MetS compared to Lean pigs (Table 1). Yet, fasting glucose levels did not differ among the groups, indicating prediabetic MetS.

Table 1:

Systemic measurements (mean ± standard deviation) in domestic pigs after 16 weeks of lean or metabolic syndrome (MetS) diet (n=5 each).

| Parameter | Lean | MetS |

|---|---|---|

| Body Weight (Kg) | 68.0±9.8 | 91.3±2.2* |

| Mean blood pressure (mmHg) | 95.6±12.3 | 123.4±7.6* |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 81.3 (74.3-88.6) | 395.0 (332.8-479.0)* |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dl) | 30.3 (25.6-38.5) | 359.1 (193.8-536.7)* |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 6.9±1.8 | 17.5±5.7* |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dl) | 119.4±18.5 | 120.3±21.9 |

| Fasting insulin (µU/ml) | 0.4±0.1 | 0.7±0.1* |

| HOMA-IR score | 0.6 (0.5-0.7) | 1.8 (1.3-1.9)* |

LDL: Low-density lipoprotein, HOMA-IR: Homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance.

p<0.05 vs. Lean.

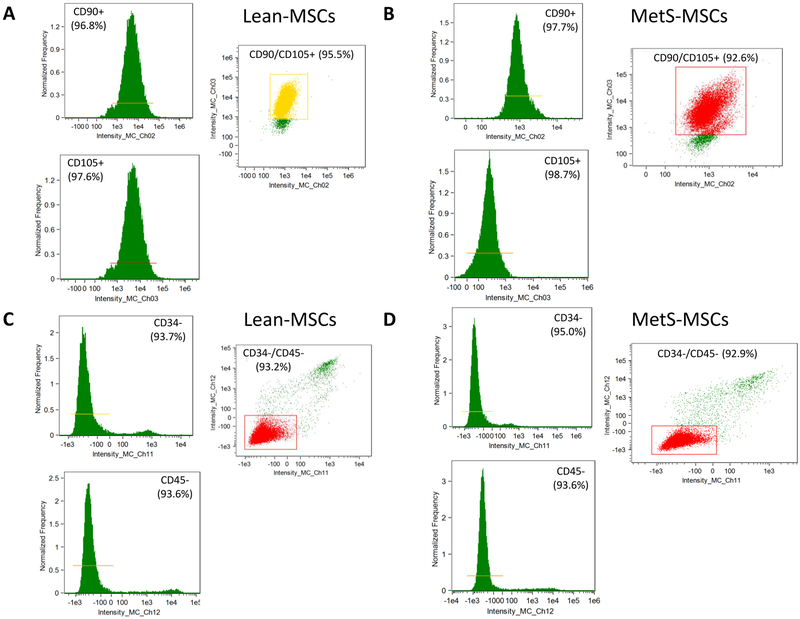

MSC characterization

Isolated and cultured Lean- and MetS-MSCs expressed similar levels of the MSC markers CD90 and CD105 (Figure 2A-B), but did not express either progenitor (CD34) or leukocyte (CD45) markers (Figure 2C-D).

Figure 2.

MSC characterization (2-column colored image)

Representative flow cytometry images showing that isolated and cultured Lean- and MetS-MSCs expressed similar levels of the MSC markers CD90 and CD105 (A-B), but did not express either progenitor (CD34) or leukocyte (CD45) markers (C-D).

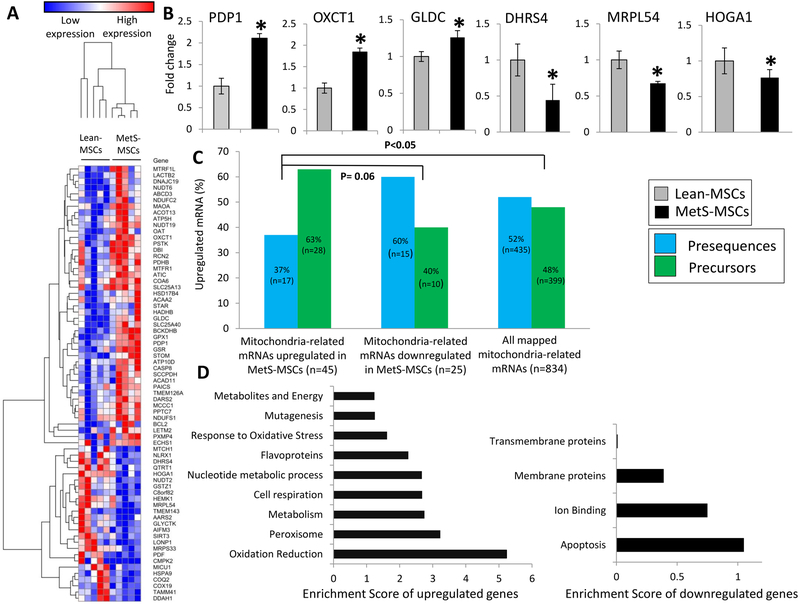

MetS upregulates expression of mRNAs encoding for mitochondrial precursor proteins

A total of 7,427 mRNAs were identified in MSCs, including 834 unique mitochondria-related genes, among which 45 were upregulated and 25 downregulated in MetS-MSCs compared to Lean-MSCs (Figure 3A). To validate these findings, we measured the expression of 6 randomly selected differentially expressed mRNAs by qPCR (PDP1, OXCT1, GLDC, HOGA1, DHRS4, and MRPL54), which followed the same patterns as the RNA sequencing findings (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

mRNA expression in MSCs (1-column colored image)

A: Heat map of differentially expressed mRNAs encoding for mitochondrial proteins between Lean- vs. MetS-MSCs. B: Expression of candidate mRNAs pyruvate dehydrogenase phosphatase subunit 1 (PDP1), 3-Oxoacid CoA-Transferase 1 (OXCT1), Glycine Decarboxylase (GLDC), 4-Hydroxy-2-Oxoglutarate Aldolase 1 (HOGA1), Dehydrogenase/Reductase 4 (DHRS4, and Mitochondrial Ribosomal Protein L54 (MRPL54) by qPCR was in accordance to RNA sequencing findings (n=5 each). C: Comparing proportions of presequences and precursors among mitochondria-related mRNAs upregulated in MetS-MSCs, down-regulated in MetS-MSCs, and all mapped mitochondria-related mRNAs. D: Functional annotation clustering of mRNAs upregulated (left) and downregulated (right) in MetS- compared to Lean- MSCs. *p<0.05 vs. Lean-MSCs.

Gene ontology analysis revealed that 17 out of 45 upregulated mRNAs encoded for mitochondrial presequences (Table 2) and the remaining 28 for precursor proteins (Table 3). Notably, the proportion of genes encoding for precursor proteins was considerably higher in mRNAs upregulated in MetS-MSCs compared to those downregulated in MetS-MSCs and all mapped mitochondria-related mRNAs in Lean- and MetS-MSCs (63% versus 40%, p=0.06, and versus 48%, p<0.05 respectively; Figure 3C), indicating that MetS preferentially upregulates mRNAs encoding for precursor proteins.

Table 2:

List of mRNAs upregulated in MetS-MSCs that encode for mitochondrial presequence proteins.

| Gene | Name | Location |

|---|---|---|

| OXCT1 | 3-Oxoacid CoA-Transferase 1 | Matrix |

| NDUFS1 | NADH:Ubiquinone Oxidoreductase Core Subunit S1 | IM |

| DARS2 | Aspartyl-TRNA Synthetase 2, Mitochondrial | Matrix |

| BCKDHB | Branched Chain Keto Acid Dehydrogenase E1 Subunit Beta | Matrix |

| ECHS1 | Enoyl-CoA Hydratase, Short Chain 1 | Matrix |

| GSR | Glutathione-Disulfide Reductase | Matrix |

| GLDC | Glycine Decarboxylase | Matrix |

| HADHB | Hydroxyacyl-CoA Dehydrogenase/3-Ketoacyl-CoA Thiolase/Enoyl-CoA Hydratase (Trifunctional Protein), Beta Subunit | OM/IM |

| ACAA2 | Acetyl-CoA Acyltransferase 2 | IM/Matrix |

| LETM2 | Leucine Zipper And EF-Hand Containing Transmembrane Protein 2 | IM |

| MCCC1 | Methylcrotonoyl-CoA Carboxylase 1 | IM/Matrix |

| MTRF1L | Mitochondrial Translational Release Factor 1 Like | Matrix |

| NUDT19 | Nudix Hydroxylase 19 | Unknown |

| OAT | Ornithine Aminotransferase | Matrix |

| PDHB | Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Beta | Matrix |

| PDP1 | Pyruvate Dehyrogenase Phosphatase Catalytic Subunit 1 | Matrix |

| STAR | Steroidogenic Acute Regulatory Protein | IMS |

IM, Inner membrane; OM, Outer membrane; IMS, Intermembrane space.

Table 3:

List of mRNAs upregulated in MetS-MSCs that encode for mitochondrial precursor proteins.

| Gene | Name | Location |

|---|---|---|

| BCL2 | BCL2, Apoptosis Regulator | OM |

| NUDT6 | Nudix Hydrolase 6 | Unknown |

| NDUFC2 | NADH:Ubiquinone Oxidoreductase Subunit C2 | IM |

| GPX1 | Glutathione Peroxidase 1 | Matrix |

| SLC25A40 | Solute Carrier Family 25 Member 40 | IM |

| MAOA | Monoamine Oxidase A | OM |

| MTFR1 | Mitochondrial Fission Regulator 1 | IM/OM |

| LACTB2 | Lactamase Beta 2 | Matrix |

| STOM | Stomatin | Unknown |

| PSTK | Phosphoseryl-TRNA Kinase | Unknown |

| COA6 | Cytochrome C Oxidase Assembly Factor 6 | IMS |

| ATP10D | ATPase Phospholipid Transporting 10D | Unknown |

| SLC25A13 | Solute Carrier Family 25 Member 13 | IM |

| PAICS | Phosphoribosylaminoimidazole Carboxylase And Phosphoribosylaminoimidazolesuccinocarboxamide Synthase | IM |

| SCCPDH | Saccharopine Dehydrogenase | Matrix |

| RCN2 | Reticulocalbin 2 | Unknown |

| HSD17B4 | Hydroxysteroid 17-Beta Dehydrogenase 4 | Unknown |

| CASP8 | Caspase 8 | OM |

| DBI | Diazepam Binding Inhibitor, Acyl-CoA Binding Protein | Unknown |

| PXMP4 | Peroxisomal Membrane Protein 4 | IM |

| ABCD3 | ATP Binding Cassette Subfamily D Member 3 | IM |

| ACAD11 | Acyl-CoA Dehydrogenase Family Member 11 | IM |

| ATIC | 5-Aminoimidazole-4-Carboxamide Ribonucleotide Formyltransferase/IMP Cyclohydrolase | Unknown |

| ACOT13 | Acyl-CoA Thioesterase 13 | Unknown |

| PPTC7 | PTC7 Protein Phosphatase Homolog | Unknown |

| ATP5H | ATP Synthase, H+ Transporting, Mitochondrial Fo Complex Subunit D | IM |

| TMEM126A | Transmembrane Protein 126A | IM |

| DNAJC19 | DnaJ Heat Shock Protein Family (Hsp40) Member C19 | IM |

IM, Inner membrane; OM, Outer membrane; IMS, Intermembrane space.

Functional clustering analysis indicated that genes up- and down- regulated in MetS-MSCs encoded for proteins involved in several mitochondrial functions, including oxidation reduction, metabolism, cell respiration, apoptosis, ion binding, and response to oxidative stress (Figure 3D).

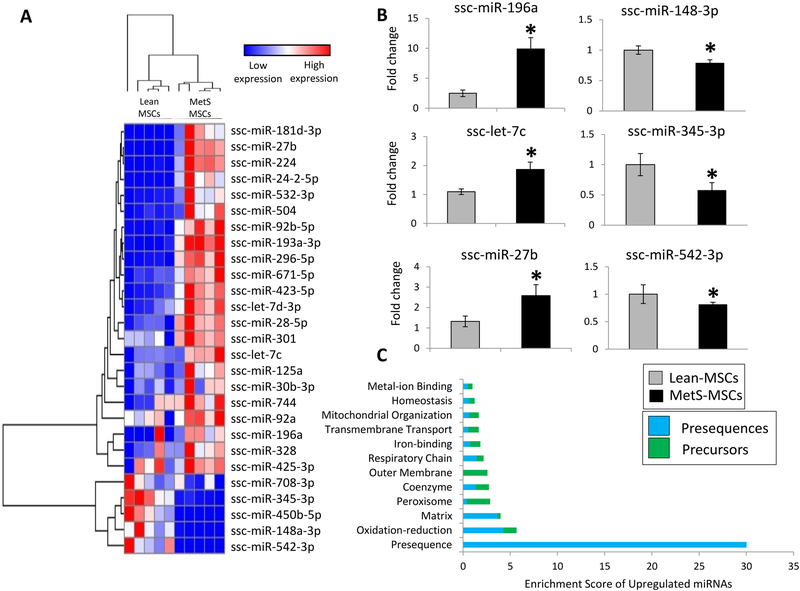

Mets induces post-transcriptional regulation of genes encoding for presequence proteins

To further investigate the mechanisms by which MetS preferentially upregulated mRNAs encoding for precursor proteins, we compared the microRNA profiles of Lean- and MetS-MSCs using RNA sequencing. We identified a total of 413 microRNAs expressed in MSCs, among which 22 were upregulated (fold change MetS-MSCs/Lean-MSCs>1.4 and p<0.05) in MetS- versus Lean-MSCs and 6 downregulated (fold change MetS-MSCs/Lean-MSCs<0.7 and p<0.05) in MetS- versus Lean-MSCs (Figure 4A). To confirm these findings, we measured the expression of 6 randomly selected differentially expressed microRNAs (ssc-miR-196a, ssc-let-7c, ssc-miR-27b, miR-148a-3p, miR-345–3p, and miR-542–3p) by qPCR, which yielded compatible results with RNA sequencing analysis (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

microRNA expression in MSCs (1-column colored image)

A: Heat map of differentially expressed microRNAs between Lean- vs. MetS-MSCs. B: Expression of candidate microRNAs ssc-miR-196a, ssc-let-7c, ssc-miR-27b, ssc-miR-148a-3p, ssc-miR-345-3p, and ssc-miR-542-3p by qPCR was in accordance to RNA sequencing findings. C: Functional annotation clustering of target genes of microRNAs upregulated in MetS-MSCs. *p<0.05 vs. Lean-MSCs.

Then, targetScan [16] and ComiR [17] were used to identify their microRNA target genes, which were subsequently filtered by MitoCarta. Functional analysis of mitochondrial target genes showed that presequences were the top category of upregulated microRNAs in MetS-MSCs (enrichment score = 30; Figure 4C). Moreover, the ratio of presequences/preproteins of micro-RNA target genes was higher among most functional categories, including coenzymes, oxidation-reduction, respiratory chain, and homeostasis pathways, suggesting that MetS-induced posttranscriptional regulation of presequence genes might be partly responsible for the imbalance of mRNAs encoding for presequences and precursors in MetS-MSCs.

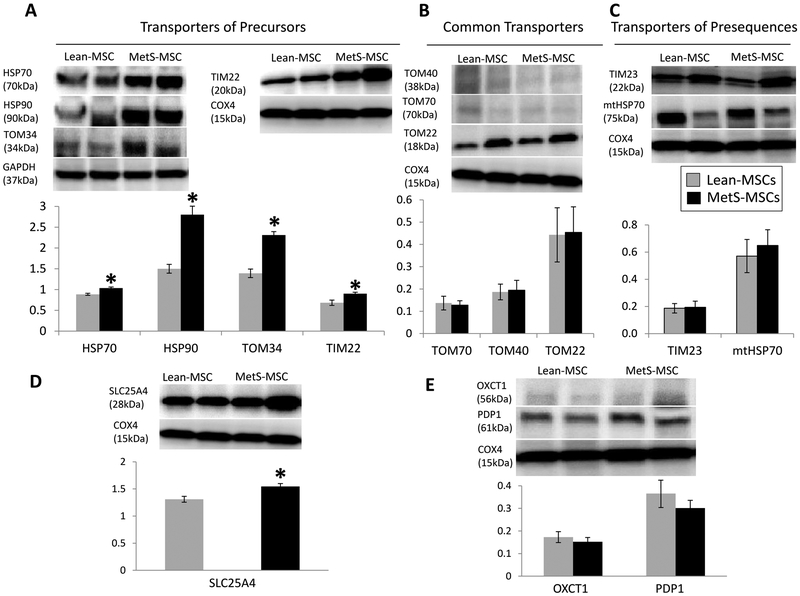

MetS upregulates expression of transporters of precursors and their substrates

We next compared the expression of transporters of mitochondrial presequence and precursor proteins between Lean- and MetS-MSCs. We found that transporters of precursor proteins including the cytosolic chaperones heat shock protein-70 (HSP70) and −90 (HSP90) and the translocase of the outer mitochondrial membrane-34 (TOM34) were upregulated in MetS-MSCs compared to Lean-MSCs (Figure 5A), as was the translocase of the inner membrane-22 (TIM22). However, expression of the common translocase of outer mitochondrial membrane (TOM) complex, including TOM40, TOM70, and TOM22 (Figure 5B) and transporters of presequence proteins, including TOM22, mitochondrial HSP70 (mtHSP70), and TIMM23 did not differ between the groups (Figures 5C).

Figure 5.

Protein expression of mitochondrial transporters and their substrates in MSCs (2 column black and white image)

Representative western blot images and quantifications for protein expression of transporters of mitochondrial precursor proteins heat shock proetin 70 (HSP70), HSP90, translocase of outer membrane 34 (TOM34), translocase of inner membrane 22 (TIM22), common transporters TOM40, TOM70, and TOM22 (B), and transporters of presequence proteins TIM23 and mitochondrial heat shock protein 70 (mtHSP70) (C) in Lean- and MetS-MSCs. D: Representative western blot images and quantifications for expression of mitochondrial precursor protein SLC25A4 (D) and presequence proteins OXCT1 and PDP1 (E) in Lean- and MetS-MSCs.

Congruently, we found that expression of precursor proteins was altered in MetS. For instance, expression of the precursor protein solute carrier family 25 member-4 (SLC25A4) was higher in MetS- compared to Lean-MSCs (Figure 5D), whereas expression of mitochondrial matrix presequence proteins 3-oxoacid CoA-transferase-1 (OXCT1) and pyruvate dehyrogenase phosphatase subunit-1 (PDP1) did not differ between the groups (Figure 5E), indicating that MetS selectively upregulates the expression of transporters of precursor proteins and their respective substrates.

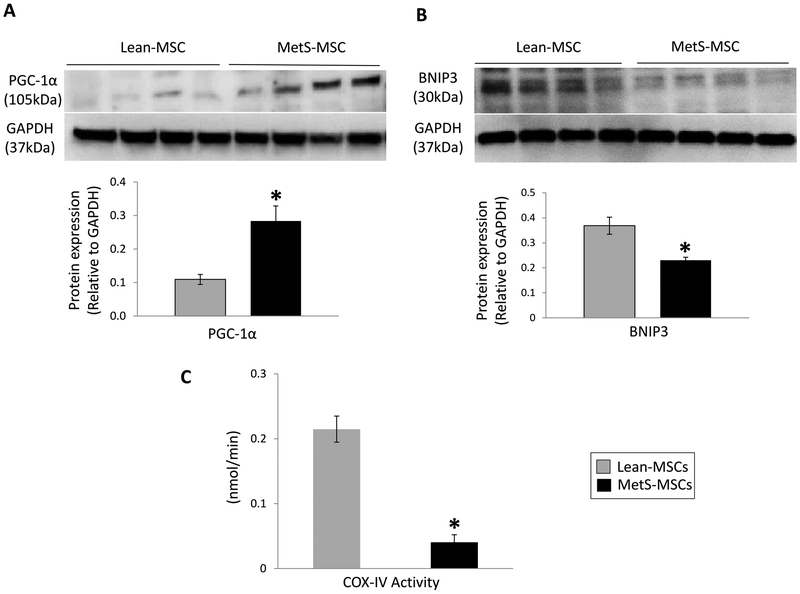

MetS alters mitochondrial homeostasis and impairs mitochondrial function in MSCs

To explore the functional implications of these findings, we compared mitochondrial homeostasis and function between Lean- and MetS- MSCs. We found that expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha (PGC-1α) was higher in MetS-MSCs compared to Lean-MSCs (Figure 6A), suggesting increased mitochondrial biogenesis. Contrarily, expression of BCL2/adenovirus E1B 19 kDa protein-interacting protein 3 (BNIP3) was downregulated in MetS-MSCs compared to Lean-MSCs (Figure 6B), suggesting decreased mitophagy. Finally, COX-IV activity was significantly decreased in MetS-MSCs compared to Lean-MSCs (Figure 6C), suggesting impaired mitochondrial energy production.

Figure 6.

Mitochondrial homeostasis and function in MSCs (1-column black and white image)

Protein expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator (PGC)-1α (A) and BCL2/adenovirus E1B 19 kDa protein-interacting protein (BNIP)-3 (B), and cytochrome-c oxidase (COX)-IV activity (C) in Lean- and MetS- MSCs. *p<0.05 vs. Lean-MSCs.

Discussion

Autologous transplantation of MSCs has demonstrated remarkable tissue-protective properties in experimental disease and is currently tested in patients with cardiovascular diseases. However, MSC function may be impaired by exposure to cardiovascular risk factors, which create an unfavorable milieu for MSC harvesting and transplantation [3, 4]. Mitochondria modulate several important aspects of MSC function. For example, MSC proliferation is only made possible by means of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation [21], and their differentiation into adipocytes and osteocytes largely relies on intact mitochondrial metabolic activity [22–24]. Furthermore, mitochondrial production of reactive oxygen species and antioxidant defenses were both found not only to influence MSCs proliferation, but also to regulate their fate, self-renewal, and multipotency [25–27].

To test whether cardiovascular risk factors modulate mitochondrial protein import in porcine MSCs, we took advantage of a novel swine model of diet-induced MetS, which leads to progressive development of common features of human MetS. We have previously shown that adipocyte cell surface area progressively enlarged over the 16 weeks of MetS diet, while abdominal visceral fat volume increased compared to Lean pigs [12]. Here, we found that MetS pigs increased body weight, total cholesterol, and LDL, accompanied by spontaneous hypertension. Despite normal fasting glucose, MetS pigs exhibited elevated fasted insulin levels and developed glucose intolerance, indicating successful development of pre-diabetic MetS. Importantly, isolated Lean- and MetS-MSCs expressed similar levels of MSC markers, and did not express either progenitor or leukocyte markers, supporting their mesenchymal origin.

In this study, we identified 45 unique mitochondrial mRNAs upregulated and 25 downregulated in MetS- compared to Lean-MSCs. Interestingly, the vast majority of genes upregulated in MetS-MSCs encoded for mitochondrial precursor proteins, whereas presequences accounted for a small proportion of proteins upregulated in MetS-MSCs. Contrarily, most genes downregulated in MetS-MSCs encoded for presequences and only a small fraction encoded for precursor proteins. Importantly, genes up- and down- regulated in MetS-MSCs encoded for proteins involved in several mitochondrial functions, including oxidation reduction, metabolism, cell respiration, apoptosis, ion binding, and response to oxidative stress. Therefore, our observations indicate that MetS preferentially upregulates the expression of genes encoding for precursor proteins and downregulates the expression of those encoding for presequences, disrupting the physiological balance between these protein groups.

To further investigate the mechanisms by which MetS alters this balance, we compared the microRNA profile of Lean- and MetS-MSCs. Micro-RNAs are highly conserved non-coding RNA fragments that regulate gene expression by directing their target mRNAs for degradation or translational repression [39]. In vitro studies have shown that the microRNA profile of MSCs differs under culture conditions that modulate cell proliferation and differentiation [40]. Furthermore, upregulation or inhibition of microRNAs in rat cardiomyocytes modulate cardiac mitochondrial biogenesis and function [41]. In this study, we found that several mitochondria-related microRNAs were upregulated in MetS- versus Lean-MSCs. Functional analysis of their mRNA targets revealed that these microRNAs primarily target genes encoding for mitochondrial presequence proteins, suggesting that MetS-induced modulation of precursor and presequence gene expression might be linked to post-transcriptional regulation of presequences.

To determine if MetS also modulates the fate of mRNAs, we comprehensively characterized the profile of the mitochondrial protein import machinery in Lean- and MetS-MSCs by Western blotting. mRNAs encoding for mitochondrial proteins are translated in ribosomes located in the proximity of the mitochondrion and preproteins subsequently transferred into the organelle by the mitochondrial import machinery [9]. Although all mitochondrial preproteins are imported by the translocase of the outer mitochondrial membrane (TOM) complex (TOM-40, TOM-70, and TOM-22), presequences and precursors utilize distinct molecular mechanisms of import to reach their final destinations [10]. Presequences are transferred to the translocase of the inner membrane (TIM)-23 for their subsequent insertion into the inner membrane or transport into the matrix by the presequence of the translocase-associated motor (PAM) complex and the mitochondrial heat shock protein 70 (mtHSP70). Contrarily, precursors usually bind cytosolic chaperones, like heat shock protein (HSP)-70, HSP-90, and TOM-34 to prevent their aggregation in the cytosol, and upon translocation through the TOM complex are integrated into the outer membrane or inserted into the inner membrane by the TIM-22 complex. Our results showed that MetS upregulated the expression of cytosolic chaperones (HSP-70, HSP-90, and TOM-34) and TIM22. However, transporters of presequence proteins (TIM-23 and mtHSP70) remained unchanged, suggesting that MetS preferentially promotes the import of precursor proteins into the mitochondria. In line with this, we found that expression of the protein substrates of these transporters followed the same pattern. While expression of the precursor protein SLC25A4 was higher in MetS- compared to Lean-MSCs, expression of the presequences OXCT1 and PDP1 did not differ between the groups. Taken together, our observations suggest that MetS modulates the import of mitochondrial preproteins into the organelle, shifting the balance of presequences and precursors towards the later.

To establish the contribution of these changes to MetS-induced MSC mitochondrial dysfunction, we compared mitochondrial homeostasis and energy production between Lean- and MetS- MSCs. Mitochondrial homeostasis is regulated by a balance between the formation of new mitochondria (mitochondrial biogenesis) and degradation of damaged mitochondria (mitophagy). Interestingly, we found that MetS increased MSC expression of PGC-1α, the master regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis [28], whereas expression of BNIP-3, which promotes mitochondrial targeting during mitophagy [29], was lower in MetS- compared to Lean-MSCs. Furthermore, we found that COX-IV activity, which catalyzes the final step in mitochondrial electron transfer chain during oxidative phosphorylation, [30] was lower in MetS- compared to Lean- MSCs, suggesting impaired mitochondrial respiration. Therefore, MetS-induced modulation of mitochondrial protein import may be linked to changes in mitochondrial biogenesis and mitophagy, and impaired energy production.

Our study is limited by the small number of animals and relatively short duration of MetS in our experimental model. Nevertheless, our pigs developed many features of human MetS after 16 weeks of feeding with high-fat/high-carbohydrate diet. This was paralleled with important changes in the transcriptome and proteome of mitochondria-related genes, remarkable alterations in the expression of microRNAs that target these genes, and significant implications for mitochondrial homeostasis and function in MetS-MSCs. However, we cannot correlate described changes with individual components of MetS. Additionally, electron microscopy analysis was not available to explore mitochondrial structural changes in MetS-MSCs. Further studies are also needed to assess whether these changes impact on MSC function and capacity to repair damaged tissues.

In summary, the current study shows that MetS alters the expression of mitochondria-related mRNAs in porcine MSCs and preferentially upregulates genes encoding for mitochondrial precursor proteins. Interestingly, these changes were associated with post-transcriptional regulation of genes encoding for presequence proteins, a selective upregulation of transporters of mitochondrial precursors and their substrates, changes in mitochondrial homeostasis, and impaired mitochondrial function. Therefore, our study has important clinical implications and may assist in developing novel approaches to boost the reparative capacity of these cells in patients with cardiovascular disease. Further studies are needed to test whether these alterations impair MSCs regenerative function in these patients.

Acknowledgements

This study was partly supported by the NIH grant numbers: DK104273, HL123160, and DK102325, DK109134, DK106427, and the Mayo Clinic: Mary Kathryn and Michael B. Panitch Career Development Award. The funding sources had no involvement in study design, conduct, analysis or interpretation of the results.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors do not have any financial conflict of interests to disclose.

Research Involving Animals

All experiments were conducted with the approval of the Mayo Clinic Animal Care and Use Committee (approval case number: A00003694–18), which regulates and establishes procedures for the scientific use of animals.

References

- 1.Spees JL, Lee RH, Gregory CA. Mechanisms of mesenchymal stem/stromal cell function. Stem Cell Res Ther 2016; 7: 125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hosseinikia R, Nikbakht MR, Moghaddam AA et al. Molecular and Cellular Interactions of Allogenic and Autologus Mesenchymal Stem Cells with Innate and Acquired Immunity and Their Role in Regenerative Medicine. Int J Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Res 2017; 11: 63–77. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Badimon L, Onate B, Vilahur G. Adipose-derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Their Reparative Potential in Ischemic Heart Disease. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed) 2015; 68: 599–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hickson LJ, Eirin A, Lerman LO. Challenges and opportunities for stem cell therapy in patients with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 2016; 89: 767–778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Friedman JR, Nunnari J. Mitochondrial form and function. Nature 2014; 505: 335–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marycz K, Kornicka K, Basinska K, Czyrek A. Equine Metabolic Syndrome Affects Viability, Senescence, and Stress Factors of Equine Adipose-Derived Mesenchymal Stromal Stem Cells: New Insight into EqASCs Isolated from EMS Horses in the Context of Their Aging. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2016; 2016: 4710326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marycz K, Kornicka K, Maredziak M et al. Equine metabolic syndrome impairs adipose stem cells osteogenic differentiation by predominance of autophagy over selective mitophagy. J Cell Mol Med 2016; 20: 2384–2404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marycz K, Kornicka K, Grzesiak J et al. Macroautophagy and Selective Mitophagy Ameliorate Chondrogenic Differentiation Potential in Adipose Stem Cells of Equine Metabolic Syndrome: New Findings in the Field of Progenitor Cells Differentiation. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2016; 2016: 3718468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lesnik C, Golani-Armon A, Arava Y. Localized translation near the mitochondrial outer membrane: An update. RNA Biol 2015; 12: 801–809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dudek J, Rehling P, van der Laan M. Mitochondrial protein import: common principles and physiological networks. Biochim Biophys Acta 2013; 1833: 274–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wiedemann N, Frazier AE, Pfanner N. The protein import machinery of mitochondria. J Biol Chem 2004; 279: 14473–14476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pawar AS, Zhu XY, Eirin A et al. Adipose tissue remodeling in a novel domestic porcine model of diet-induced obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2015; 23: 399–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu XY, Ma S, Eirin A et al. Functional Plasticity of Adipose-Derived Stromal Cells During Development of Obesity. Stem cells translational medicine 2016; 5: 893–900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eirin A, Riester SM, Zhu XY et al. MicroRNA and mRNA cargo of extracellular vesicles from porcine adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Gene 2014; 551: 55–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Calvo SE, Clauser KR, Mootha VK. MitoCarta2.0: an updated inventory of mammalian mitochondrial proteins. Nucleic Acids Res 2016; 44: D1251–1257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Agarwal V, Bell GW, Nam JW, Bartel DP. Predicting effective microRNA target sites in mammalian mRNAs. Elife 2015; 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coronnello C, Benos PV. ComiR: Combinatorial microRNA target prediction tool. Nucleic Acids Res 2013; 41: W159–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saad A, Zhu XY, Herrmann S et al. Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells from patients with atherosclerotic renovascular disease have increased DNA damage and reduced angiogenesis that can be modified by hypoxia. Stem Cell Res Ther 2016; 7: 128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eirin A, Ebrahimi B, Zhang X et al. Mitochondrial protection restores renal function in swine atherosclerotic renovascular disease. Cardiovasc Res 2014; 103: 461–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang X, Li ZL, Crane JA et al. Valsartan regulates myocardial autophagy and mitochondrial turnover in experimental hypertension. Hypertension 2014; 64: 87–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pattappa G, Heywood HK, de Bruijn JD, Lee DA. The metabolism of human mesenchymal stem cells during proliferation and differentiation. J Cell Physiol 2011; 226: 2562–2570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Costello LC, Franklin RB. A review of the important central role of altered citrate metabolism during the process of stem cell differentiation. J Regen Med Tissue Eng 2013; 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen CT, Shih YR, Kuo TK et al. Coordinated changes of mitochondrial biogenesis and antioxidant enzymes during osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells 2008; 26: 960–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hsu YC, Wu YT, Yu TH, Wei YH. Mitochondria in mesenchymal stem cell biology and cell therapy: From cellular differentiation to mitochondrial transfer. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2016; 52: 119–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Folmes CD, Dzeja PP, Nelson TJ, Terzic A. Metabolic plasticity in stem cell homeostasis and differentiation. Cell Stem Cell 2012; 11: 596–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garcia-Prat L, Sousa-Victor P, Munoz-Canoves P. Proteostatic and Metabolic Control of Stemness. Cell Stem Cell 2017; 20: 593–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hu C, Fan L, Cen P et al. Energy Metabolism Plays a Critical Role in Stem Cell Maintenance and Differentiation. Int J Mol Sci 2016; 17: 253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jornayvaz FR, Shulman GI. Regulation of mitochondrial biogenesis. Essays Biochem 2010; 47: 69–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ding WX, Yin XM. Mitophagy: mechanisms, pathophysiological roles, and analysis. Biol Chem 2012; 393: 547–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li Y, Park JS, Deng JH, Bai Y. Cytochrome c oxidase subunit IV is essential for assembly and respiratory function of the enzyme complex. J Bioenerg Biomembr 2006; 38: 283–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]