Abstract

Background

Shared care has been used in the management of many chronic conditions with the assumption that it delivers better care than primary or specialty care alone; however, little is known about the effectiveness of shared care.

Objectives

To determine the effectiveness of shared care health service interventions designed to improve the management of chronic disease across the primary/specialty care interface. This is an update of a previously published review.

Secondary questions include the following:

1. Which shared care interventions or portions of shared care interventions are most effective?

2. What do the most effective systems have in common?

Search methods

We searched MEDLINE, Embase and the Cochrane Library to 12 October 2015.

Selection criteria

One review author performed the initial abstract screen; then two review authors independently screened and selected studies for inclusion. We considered randomised controlled trials (RCTs), non‐randomised controlled trials (NRCTs), controlled before‐after studies (CBAs) and interrupted time series analyses (ITS) evaluating the effectiveness of shared care interventions for people with chronic conditions in primary care and community settings. The intervention was compared with usual care in that setting.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently extracted data from the included studies, evaluated study quality and judged the certainty of the evidence using the GRADE approach. We conducted a meta‐analysis of results when possible and carried out a narrative synthesis of the remainder of the results. We presented the results in a 'Summary of findings' table, using a tabular format to show effect sizes for all outcome types.

Main results

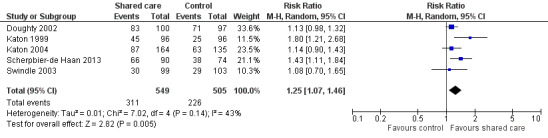

We identified 42 studies of shared care interventions for chronic disease management (N = 18,859), 39 of which were RCTs, two CBAs and one an NRCT. Of these 42 studies, 41 examined complex multi‐faceted interventions and lasted from six to 24 months. Overall, our confidence in results regarding the effectiveness of interventions ranged from moderate to high certainty. Results showed probably few or no differences in clinical outcomes overall with a tendency towards improved blood pressure management in the small number of studies on shared care for hypertension, chronic kidney disease and stroke (mean difference (MD) 3.47, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.68 to 5.25)(based on moderate‐certainty evidence). Mental health outcomes improved, particularly in response to depression treatment (risk ratio (RR) 1.40, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.22 to 1.62; six studies, N = 1708) and recovery from depression (RR 2.59, 95% CI 1.57 to 4.26; 10 studies, N = 4482) in studies examining the 'stepped care' design of shared care interventions (based on high‐certainty evidence). Investigators noted modest effects on mean depression scores (standardised mean difference (SMD) ‐0.29, 95% CI ‐0.37 to ‐0.20; six studies, N = 3250). Differences in patient‐reported outcome measures (PROMs), processes of care and participation and default rates in shared care services were probably limited (based on moderate‐certainty evidence). Studies probably showed little or no difference in hospital admissions, service utilisation and patient health behaviours (with evidence of moderate certainty).

Authors' conclusions

This review suggests that shared care improves depression outcomes and probably has mixed or limited effects on other outcomes. Methodological shortcomings, particularly inadequate length of follow‐up, may account in part for these limited effects. Review findings support the growing evidence base for shared care in the management of depression, particularly stepped care models of shared care. Shared care interventions for other conditions should be developed within research settings, with account taken of the complexity of such interventions and awareness of the need to carry out longer studies to test effectiveness and sustainability over time.

Plain language summary

Shared care across the interface between primary and specialty care in chronic disease management

What is the aim of this review?

We conducted this Cochrane review to find out if shared care between primary and specialty care physicians improves outcomes for patients with chronic conditions. Cochrane researchers collected and analysed studies to answer this question and found 42 studies relevant for inclusion.

Key messages

This review suggests that shared care is effective for managing depression. Shared care interventions for other conditions should be developed within research settings, so that further evidence can be considered before they are introduced routinely into health systems.

What was studied in this review?

We have defined shared care across the primary/specialty interface as joint participation of primary care physicians and specialty care physicians in planned delivery of care. This may be informed by enhanced information exchange, over and above routine discharge and referral notices. This approach has the potential to improve the management of chronic disease while leading to better outcomes than are attained by primary or specialty care alone.

What are the main results of the review?

Review authors found 42 relevant studies; 39 were randomised controlled trials. Studies were based in 12 different countries that use a range of healthcare systems. Investigators examined shared care for a range of chronic conditions, with diabetes and depression the most commonly included. Most studies examined shared care interventions that consisted of multiple elements and lasted an average of 12 months.

Study results suggest that shared care Interventions lead to improved outcomes for patients with depression. However, effects of shared care on a range of other outcomes are less certain. Shared care probably has limited or no effect on clinical outcomes, apart from modest effects on improving blood pressure management and mixed effects on patient‐reported outcome measures (such as quality of life and ability to carry out daily tasks), medication prescribing and use, participation in shared care services and management of risk factors. Shared care probably would have little or no effect on hospital admissions, use of services and patient health behaviours.

How up‐to‐date is this review?

Review authors searched for studies that had been published up to October 2015.

Summary of findings

for the main comparison.

| Shared care compared with usual care for patients with chronic conditions | |||

|

Patient or population: adults with chronic conditions Settings: primary care and community settings Intervention: shared care defined as joint participation of primary care physicians and specialty care physicians in planned delivery of care, informed by an enhanced information exchange over and above routine discharge and referral notices Comparison: usual care | |||

| Outcomes | Impacts | Number of studies (participants) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) |

| Clinical outcomes: physical heath | Results show probably little or no difference in clinical outcomes related to physical health but a tendency towards improved blood pressure management in the few studies conducted to examine blood pressure outcomes in shared care studies for hypertension (one study, N = 490) diabetes (seven studies, N = 2184), chronic kidney disease (one study, N = 181) and stroke (one study, N = 186) (mean difference (MD) 3.47, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.68 to 5.25) | 16 (6977) |

⊕⊕⊕⊖ Moderatea |

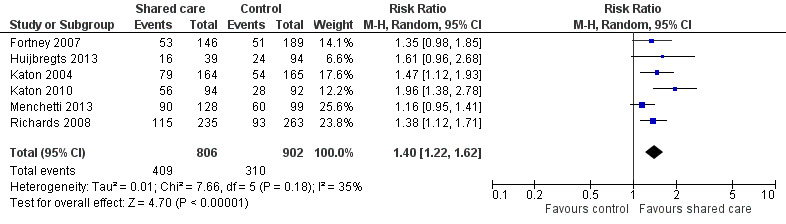

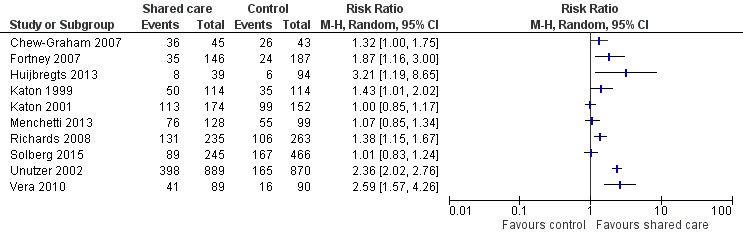

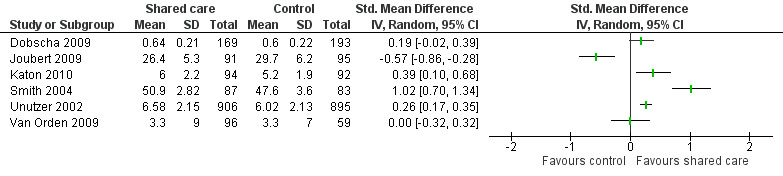

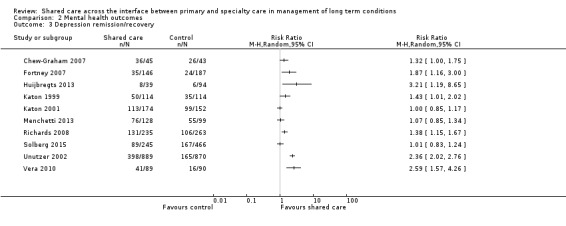

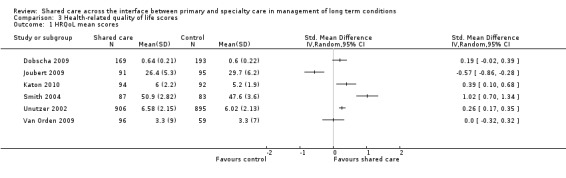

| Clinical outcomes: mental health | Shared care results in improved response to depression treatment (risk ratio (RR) 1.40, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.22 to 1.62; six studies, N = 1708) and greater recovery from depression (RR 2.59, 95% CI 1.57 to 4.26; 10 studies, N = 4482) in studies examining the 'stepped care' design of shared care interventions (10 studies, N = 4482) Shared care has moderate effects on mean depression scores (standardised mean difference (SMD) ‐0.29, 95% CI ‐0.37 to ‐0.20; six studies, N = 3250) | 18 (6243) |

⊕⊕⊕⊕ Highb |

| Patient‐reported outcome measures (PROMs) | Effects on PROMs are probably mixed, as only half of studies reporting these outcomes reported benefit. | 18 (8698) |

⊕⊕⊕⊖ Moderatec |

| Hospital admissions | Data show probably little or no difference in hospital admissions, with only a third of studies reporting that this outcome showed benefit. | 9 (2396) |

⊕⊕⊕⊖ Moderatec |

| Process of care | Investigators noted little of no difference in service utilisation, with a third of studies reporting this outcome describing benefit (12 studies, N = 5072). Effects on medication‐related outcomes were probably modest, with half of studies reporting this outcome showing benefit (18 studies, N = 9118). Effects on management of risk factors were probably modest, with half of studies reporting this outcome showing benefit (seven studies, N = 2740). | 26 (13,088) |

⊕⊕⊕⊖ Moderatec |

| Participation and default rates | Effects on participation and default rates were probably modest, with most studies reporting this outcome showing benefit. | 7 (1639) |

⊕⊕⊕⊖ Moderatec |

| Participant health behaviours | Results showed probably little or no effect on patient health behaviours related to smoking (six studies, N = 3648), exercise (one study, N = 214) and diet (one study, N = 214). | 8 (4565) |

⊕⊕⊕⊖ Moderatec |

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence. High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||

aWe downgraded the evidence for effects on clinical outcomes to moderate owing to inconsistency across studies.

bWe graded evidence for mental health outcomes as high owing to consistency of effect across studies.

c We downgraded the evidence for effects on PROMs, hospital admissions, process of care, participation and default rates and patient behaviour and risk factors to moderate owing to inconsistency in effect across studies.

Background

Description of the condition

Shared care has been defined as joint participation of primary care physicians and specialist care physicians in planned delivery of care for patients with a chronic condition, informed by an enhanced information exchange over and above routine discharge and referral (Hickman 1994). Chronic or non‐communicable conditions are defined as conditions that are generally of long duration and slow progression (WHO). Shared care has been used over the past three to four decades on the basis that it offers patients the benefit of input from both specialist and primary care providers in the management of many chronic conditions. The initial focus was on diabetes (Greenhalgh 1994), and emphasis has been placed more recently on shared care for depression (Bartels 2014), but this approach has been used for patients with at least 14 other chronic conditions (Hickman 1994). With spiraling healthcare costs in most healthcare systems, cost‐effective and shared or integrated care is needed for management of chronic conditions (Atun 2013; Bauer 2014; Kings Fund 2015).

The importance of improving management of chronic disease has become increasingly apparent for healthcare practitioners in most countries. Evidence suggests that management is based on a complex interplay of system characteristics and population risk factors and is suboptimal in many cases (Bauer 2014;Wagner 2002).

Description of the intervention

A taxonomy of shared care for chronic disease originally created in the UK (Hickman 1994) suggested that shared care systems may be defined in the following ways.

Community clinics: Specialists attend or run a clinic in a primary care setting with primary care personnel. Communication is informal and depends on specialists and primary care team members meeting on‐site.

Basic model: A specific, regular communication system is set up between specialty and primary care. This may be enhanced by an administrator who organises appointments and follows up and recalls defaulters from care.

Liaison: A liaison meeting is attended by specialists and primary care team members, who discuss and plan ongoing treatment of patients within the service.

Shared care record card: In a more formal arrangement for information sharing, an agreed data set is entered onto a record card, which is usually carried by the patient.

Computer‐assisted shared care and electronic mail: A data set is agreed upon and collected in both specialty and primary care settings and is circulated between the two sectors via computer systems such as a central repository or email. This system may include centrally co‐ordinated computerised registration and recall of patients.

Theoretically, shared care presents an opportunity for patients to receive the benefits of specialist intervention combined with continuity of care and management of comorbidity provided by generalists, who maintain responsibility for all aspects of the patient's health care beyond the specified chronic disease. Starfield argued for a shared model of primary care and specialty care among physicians for the management of common chronic conditions with prevalence greater than two per 1000 in a practice population (Starfield 2003).

How the intervention might work

Shared care systems frequently include prespecified clinical protocols, referral guidelines, continuing education of participating clinicians, specifically designed information exchange systems and ongoing audit and evaluation of services delivered. They should provide an opportunity for structured, ongoing clinical management of the specified chronic disease provided by both sets of providers. Shared care is sometimes referred to as integrated care but commonly describes collaborative care between disciplines within a single setting.(description of the intervention).

Why it is important to do this review

Little is known about the nature or effectiveness of the primary/specialty care interface (Chen 2009;Starfield 2003), and evidence is needed that will guide healthcare planning and provide a framework for improved management of chronic disease.

The present systematic review considers the effects of shared care between specialists and primary care healthcare providers. This review is an update of Smith 2007.

Objectives

To determine the effectiveness of shared care health service interventions designed to improve the management of chronic conditions across the primary/specialty care interface. This is an update of a previously published review.

Secondary questions include the following.

Which shared care interventions or portions of shared care interventions are most effective?

What do the most effective systems have in common?

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We considered randomised controlled trials (RCTs), non‐randomised controlled trials (NRCTs) and controlled before‐after studies (CBAs) with at least two control sites and at least two intervention sites, as well as interrupted time series studies (ITS) that described a clearly defined point in time when the intervention occurred and at least three data points before and three data points after the intervention. We included studies published in all languages. We chose these study designs because we believed they were most appropriate for the health services research‐type question underpinning this review, and because we believed that non‐RCT designs might be used more commonly to evaluate new services.

Types of participants

People or populations with a specified chronic disease(s) who were enrolled in a defined, shared care service provided by primary and specialty care practitioners.

Primary care physicians defined as physicians who provide primary health care. Primary health care consists of integrated, easy‐to‐access healthcare services provided by clinicians who are accountable for addressing a large majority of personal healthcare needs, developing a sustained and continuous relationship with patients and practising in the context of family and community (Vaneslow 1995).

Specialist care physicians who work in hospital settings such as outpatient clinics and emergency departments or in community settings and deliver specialist care to individuals that is based on a certain physiological system or clinical condition or principally on patient age. In some healthcare systems, they may also deliver primary care‐type services that would not satisfy the full definition of primary care as outlined in the Vanselow definition, particularly in relation to practice within a family context.

Types of interventions

We considered all types of structured interventions that involved continuing collaborative clinical care provided by primary and specialist care physicians for treatment of patients with a prespecified chronic disease. We included shared care systems that reflect models 3, 4 and 5 in the taxonomy of shared care described above (Hickman 1994), that is:

liaison meetings between specialists and primary care team members for discussion and planning of ongoing management of prespecified chronic disease;

shared care record cards (usually patient‐held); and

computer‐assisted shared care and electronic mail whereby an agreed data set was collected in both primary and specialty care settings and circulated between sectors. This system could include centrally co‐ordinated computerised registration and recall of patients.

We also included a fourth category classified as 'other' to include additional types of shared care services not represented in the taxonomy, so as to make this review more comprehensive.

We classified shared care interventions as simple if they used only one of these approaches, and as multi‐faceted if they incorporated more than one feature.

Investigators compared interventions versus usual care.

We excluded the following interventions.

Structured disease management in primary or specialty care that did not routinely involve prespecified care from the other provider for most participating patients (e.g. diabetes mini‐clinics in general practice with structured care provided by primary care physicians only).

Specialist outreach clinics or specialist liaison services in primary care settings defined as planned and regular visits by specialist physicians from a usual practice location, with no ongoing structured joint management programmes for participating patients (Gruen 2004).

Professional educational interventions or research initiatives by which no specified, structured clinical care was delivered to patients.

Interventions directed at communities of people on the basis of location or age of participants that have no specified chronic disease management component (e.g. interventions to improve the care of elderly patients that are based solely on age rather than specified chronic disease management).

Types of outcome measures

We included studies if they reported any objective measure of:

clinical outcomes, including physical health outcomes such as blood pressure and mental health outcomes such as depression scores;

patient‐reported outcome measures (PROMs);

hospital admissions;

process of care, including visits, prescribing and management of risk factors;

participation and default rates;

treatment satisfaction if this was reported by validated measures in a study that also reported patient outcomes or provider behaviours;

patient health behaviours; or

cost outcomes including simple cost and economic analyses of cost‐effectiveness.

We did not consider attitudinal and knowledge outcomes.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) information specialists developed search strategies in consultation with the review author team. We revised searches conducted for previous versions of this review (Smith 2007) and searched the following databases on 12 October 2015.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2015, Issue 9), part of the Cochrane Library (www.cochranelibrary.com), including the Cochrane EPOC Specialised Register.

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) (the Cochrane Library; Wiley; 2015, Issue 2).

National Health Service (NHS) Economic Evaluation Database (NHSEED) (the Cochrane Library; Wiley; 2015, Issue 2).

Health Technology Assessment (HTA) (the Cochrane Library; Wiley; 2015, Issue 3).

MEDLINE In‐Process and other non‐indexed citations, and MEDLINE, OvidSP (1946 to 12 October 2015).

Embase, OvidSP (1974 to 9 October 2015).

See the full search strategies presented in Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

We searched the Science Citation Index (SCISearch) for papers that cited studies included in this review. We handsearched the reference lists of studies included in the review. We applied no language or date restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

We downloaded to Endnote reference manager software (EndNote) all citations identified by electronic searches, and we removed duplicates. The lead review author (SS) identified potentially relevant studies by reviewing titles and abstracts provided by the search. We retrieved full‐text copies of all articles identified as potentially relevant. Two review authors independently assessed each retrieved article for inclusion (SS and SA/TOD/GC/BC). We resolved disagreements about eligibility by consensus between review authors and sought advice from the contact editor regarding the eligibility of one study. If details of the intervention provided in the paper were not clear, we contacted study authors to clarify the nature of the intervention. We contacted the authors of 16 papers and received replies from six.

Ongoing studies

We identified and described Ongoing studies, when possible, and provided an estimate of the reporting date when available.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors independently abstracted data using a modified version of the EPOC data collection checklist (EPOC 2013b). We resolved disagreements about eligibility and quality by consensus between review authors. When discrepancies remained, a third review author reviewed the paper or, if necessary, we referred the paper to the Cochrane contact editor.

We extracted the following data from all included studies.

Details of the intervention: We extracted a full description of the intervention including details regarding aims, clinical protocols, information exchange systems, use of link workers and remuneration and payment systems (whether free to patients at the point of delivery).

-

Participants.

Patients, nature of their chronic condition.

Providers (specialist and primary care providers involved).

Clinical setting: We examined the organisation of primary care and specialist services in that particular setting or country.

Study design: We excluded studies with significant design flaws.

Results: We organised results into health outcomes, process of care including changes in patient and provider behaviour, patient and provider acceptability and costs.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed the risk of bias for included studies using standard EPOC criteria and judgements (EPOC 2015). We discussed disagreements and reached consensus. If necessary, we would have consulted a third review author. We considered the following risk of bias domains: randomisation; allocation concealment; baseline data collection; blinding of participants and personnel; blinding of outcome assessors; incomplete outcome data; selective outcome reporting; and contamination and other bias.

Measures of treatment effect

When possible, we presented results in natural units for each study.

For RCTs, NRCTs and CBAs, we presented results of dichotomous outcomes in terms of:

absolute difference (mean or proportion of outcome in intervention group minus control at study completion);

relative percentage difference (absolute difference divided by postintervention score in the control group);

absolute change from baseline (before‐after changes in intervention and control groups); and

difference in absolute changes from baseline. For studies without baseline data, we reported only absolute difference and relative percentage difference.

We calculated standardised effect sizes (SESs) for continuous measures by dividing the difference in mean scores between intervention and comparison groups in each study by an estimate of the pooled standard deviation, when possible. We presented these in the accompanying tables.

Unit of analysis issues

We reported any issues related to cluster effects in the Results section but did not have to undertake corrections for unit of analysis errors, as no studies included in the meta‐analyses had unit of analysis errors.

Dealing with missing data

If data were missing, we contacted study authors, when possible, to obtain the missing information.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We considered clinical heterogeneity in terms of intervention components and clearly reported these in the Characteristics of included studies; we considered statistical heterogeneity when undertaking meta‐analyses.

Assessment of reporting biases

We assessed reporting bias by comparing outcomes listed in the Methods section versus those reported in the Results section and, when possible, checked outcomes in published protocols.

Data synthesis

Primary analyses

Primary analyses were based on primary and secondary outcome measures as defined by study authors. These included continuous variables (such as glycosylated haemoglobin in patients with diabetes) or dichotomous process measures (such as proportion of patients with diabetes undergoing a structured annual review for complications).

We undertook meta‐analyses using random‐effects models, when possible, and used forest plots to present outcomes. If analyses indicated significant heterogeneity (I2 > 60%), we presented graphs without a pooled effect to provide a visual representation of study results for that outcome. We used standardised mean differences (SMDs) in meta‐analyses when different scales were used to report the same outcome.

We assessed the certainty of evidence for the main comparison using Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) criteria (GRADE 2012), and we have presented our judgements in a 'Summary of findings' table. We downgraded the certainty of the evidence when we had concerns about study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias. We used EPOC Worksheet 23 to guide this process (EPOC 2013).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We had considered undertaking subgroup analyses by intervention type but found that this was not possible owing to the complex nature of the interventions. We undertook one subgroup analysis within the meta‐analysis of effects of shared care on hypertension for patients with and without diabetes. We explored heterogeneity within meta‐analyses visually and by using I2 statistics; we have not presented pooled estimates for analyses with significant heterogeneity.

Sensitivity analysis

We conducted no sensitivity analyses.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

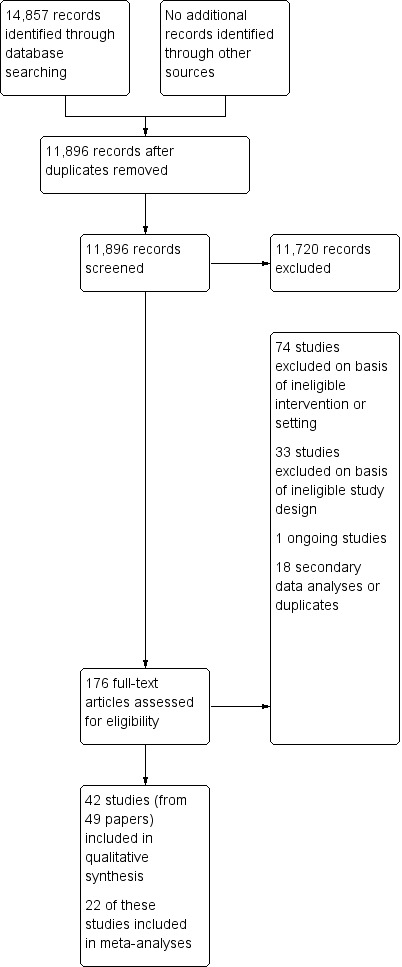

We identified 14,857 titles and removed 2961 duplicates, leaving 11,896 titles for first review. We reduced this number to 175 abstracts to be screened by two review authors for eligibility (SS, SA, TOD, GC and BC). Of these, we identified 42 studies from 49 papers as eligible for inclusion; we identified one as an ongoing study (Characteristics of ongoing studies), excluded 107 with reasons (Excluded studies) and identified 18 as secondary data publications from other included or excluded studies.

We have provided a flow chart of the search process and results in Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

See the Characteristics of included studies table.

Study design

We identified 42 studies that met the eligibility criteria for this review (N = 18,859): 39 RCTs, two CBAs (Meulepas 2007; Wood 1994) and one NRCT with a stepped wedge design (Solberg 2015). NIneteen of the 39 RCTs were cluster‐RCTs (Byng 2004; Callahan 2006; Dey 2002; Dobscha 2009; Donohoe 2000; Doughty 2002; Fihn 2011; Fortney 2007; Holm 2002; Huijbregts 2013; Menchetti 2013; Rea 2004; Richards 2008; Scherpbier‐de Haan 2013; Smith 2004; Smith 2008; Swindle 2003; Van Orden 2009; Warner 2000). Follow‐up in these studies ranged from three months to three years; most studies lasted one year.

Targeted chronic condition(s)

These studies covered a range of chronic diseases, including asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (Drummond 1994; Meulepas 2007; Rea 2004), cancer (Johannson 2001), congestive cardiac failure (CCF) (Dendale 2012; Doughty 2002), depression (Chew‐Graham 2007; Conradi 2007; Fortney 2007; Huijbregts 2013; Katon 1999; Katon 2001; Llewelyn‐Jones 1999; Menchetti 2013; Richards 2008; Solberg 2015; Swindle 2003; Unutzer 2002; Vera 2010), anxiety (Muntingh 2013), chronic mental illness (Byng 2004; Van Orden 2009; Warner 2000; Wood 1994), diabetes mellitus (DICE 1994; Donohoe 2000; Duran 2008; Goderis 2010; Hoskins 1992; Smith 2004; Smith 2008), comorbid depression and diabetes (Katon 2004; Katon 2010), comorbid depression and Alzheimer's disease (Callahan 2006), hypertension (McGhee 1994), ischaemic heart disease (Fihn 2011), transient ischaemic attack/cerebrovascular accident (TIA/CVA) (Joubert 2009), opiate misuse (Dey 2002), rheumatoid arthritis (Primdahl 2014), chronic kidney disease with comorbid diabetes and/or hypertension (Scherpbier‐de Haan 2013), chronic pain (Dobscha 2009) and a variety of chronic conditions requiring long‐term oral anticoagulation therapy (Holm 2002).

Participants

Professional participants included a wide variety of specialist physicians, specialist nurses and others, such as psychologists, psychiatrists, social workers and dieticians, and primary care professionals such as general practitioners (GPs) or family practitioners, primary care practitioners, practice nurses and home care nurses.

Settings

Studies were carried out in a variety of settings: eight in the UK, 13 in the USA, three in Australia, three in New Zealand, seven in the Netherlands, two in Denmark and Belgium and one each in Ireland, Sweden, Spain, Italy and Puerto Rico. These studies represented a variety of healthcare systems from publicly funded systems with universal free healthcare delivery, such as the UK, to more mixed public and private systems such as those in Australia and Ireland and insurance‐based systems within the USA and the Netherlands.

Shared care interventions

Forty‐one shared care interventions were multi‐faceted, and only one involved a simple intervention ‐ a shared care record card (Warner 2000). Therefore, most studies examined complex interventions involving combinations of previously agreed upon roles within each sector, clinical and referral guidelines, defined patient reviews in each sector, education and training for patients and professionals (principally for primary care professionals and workers at the interface) and synchronised patient records and recall systems. We originally planned to look for ‘other’ intervention types, but as 41 of the 42 studies provided complex multi‐faceted interventions, this was not really relevant.

Shared care interventions appeared to be driven by the specialist sector in 11 included studies (Dey 2002; Donohoe 2000; Doughty 2002; Duran 2008; Holm 2002; Hoskins 1992; Johannson 2001; Llewelyn‐Jones 1999; McGhee 1994; Primdahl 2014; Warner 2000). These studies performed relatively limited analyses of activity in primary care. Remaining studies involved a clearer collaboration between and more complete analysis of activity in both sectors.

Eighteen studies included a clearly identified professional (usually a nurse specialist) outside the study team and a usual service delivery team, whose role included co‐ordination of care across the primary/specialty care divide. Other studies reported that the service was co‐ordinated by members of the specialist team or study team (Byng 2004; Donohoe 2000; Doughty 2002; Goderis 2010; Holm 2002; Johannson 2001; Katon 1999; Katon 2002; Llewelyn‐Jones 1999; Muntingh 2013). Five studies reported on shared care interventions that were largely computer based (Dendale 2012; DICE 1994; Drummond 1994; McGhee 1994; Smith 2008).

The overall purpose of shared care interventions, as described by study authors, was to improve patient care. This was described as occurring through various mechanisms, including increasing and integrating care provided in each sector; improving, introducing or maintaining appropriate clinical management; delivering alternative and potentially more effective care; targeting higher‐risk patients; overcoming cost barriers; and increasing patient satisfaction.

Comparison intervention

Thirty‐three studies generally compared intervention groups versus a group of control patients who received what was described as 'usual care'. This was done in the primary care sector in most cases and in the specialist sector in seven studies (DICE 1994; Drummond 1994; Duran 2008; Hoskins 1992; Llewelyn‐Jones 1999; McGhee 1994; Primdahl 2014). For the remaining nine studies, the comparison was usual care augmented with an educational meeting (Callahan 2006; Dey 2002; Donohoe 2000; Fortney 2007; Menchetti 2013; Swindle 2003); an email outlining cardiovascular risk (Smith 2008); or information on depression screening results for primary care physicians (Katon 2010; Swindle 2003). In one study, participants received usual care but were themselves informed about their depression screening results and were advised to see their GP (Vera 2010).

Outcomes

The RCTs examined a range of outcomes including clinical outcomes, PROMs, process outcomes and cost outcomes. Two studies (Dey 2002; Donohoe 2000) presented a composite measure of the process of care, measuring participation in shared care or appropriateness of referral. The outcome in Dey 2002 (participation in shared care) was of borderline value in that control patients, by definition, could not participate in shared care and therefore scored zero automatically. Thirteen studies reported cost outcomes, and one study author (the review author, SS) provided cost data (from an MD thesis).

One CBA study reported inpatient admission days and time to first re‐admission in the two years before and after introduction of the intervention.

Excluded studies

We excluded 107 studies in total (see Characteristics of excluded studies). We excluded 33 studies on the basis of ineligible study design and 74 studies on the basis of an ineligible shared care intervention or setting, which usually involved conducting the study in a specialist setting or providing integrated care between different professional groups within the same setting.

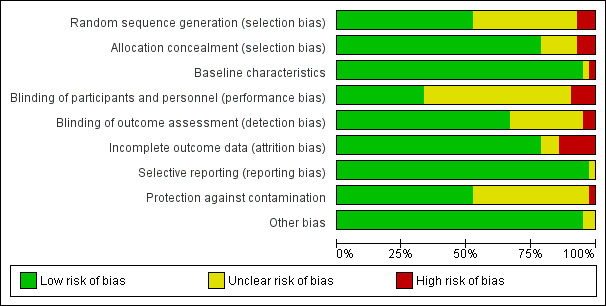

Risk of bias in included studies

See Characteristics of included studies, Figure 2 and Figure 3 for summary assessments of the risk of bias of included studies. Overall only three studies were at low risk of bias for all domains (Dobscha 2009; Muntingh 2013; Smith 2004). Nine RCTs and all three NRCTs reported at least one domain as having high risk of bias (Callahan 2006; Chew‐Graham 2007; Dendale 2012; Donohoe 2000; Drummond 1994; Hoskins 1992; Huijbregts 2013; Llewelyn‐Jones 1999; Menchetti 2013; Meulepas 2007; Solberg 2015; Wood 1994). Among the 30 remaining studies (all RCTs), we classified some domains as having unclear risk due to lack of reporting, mainly related to lack of blinding of participants and personnel and potential contamination. We have reported the risk of bias for RCTs and NRCTs separately below.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

3.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Allocation

Randomisation was unclear in 17 of the 39 RCTs, and allocation concealment was unclear in six of the 39 RCTs, mainly owing to failure to report the actual method of allocation.

Baseline data collection

One study did not report baseline data collection (Drummond 1994), and another study had unclear risk, as investigators reported only demographic details of participants at baseline (McGhee 1994). The remaining 37 RCTs reported baseline data collection that was similar between groups.

Blinding

Four of the 39 RCTs did not report blinding of participants and personnel (Callahan 2006; Chew‐Graham 2007; Dendale 2012; Drummond 1994), and blinding was unclear in 24 other studies, mainly because it was impossible to blind participants given the nature of the complex interventions being tested, unless the study used a cluster design or reported geographical separation of control and intervention groups, as in Menchetti 2013. Blinded outcome assessment was unclear in 11 RCTs and was not done in another RCT (Menchetti 2013). In two studies, primary care providers were unaware that they were participating in an intervention study (Hoskins 1992; Llewelyn‐Jones 1999).

Incomplete outcome data

In most studies, risk of bias was low in relation to incomplete outcome data, but four of the 39 RCTs had high risk of bias for this domain (Donohoe 2000; Hoskins 1992; Huijbregts 2013; Llewelyn‐Jones 1999) and risk was unclear in three studies owing to lack of reporting.

Selective reporting

Only one of the 42 studies had clearly failed to report one of its stated secondary outcomes (Chew‐Graham 2007), but the effect of this was unclear. In all other studies, results were at least described in the text, although investigators did not necessarily present all data.

Protection against contamination

We noted potential for contamination in 18 of the 39 RCTs mainly owing to lack of clarity on reporting of intervention and comparison settings. Only one of the individually randomised trials specifically addressed the issue of potential contamination (Joubert 2009). Twenty‐one of the included RCTs had a cluster design (see Characteristics of included studies), which generally reduced the risk of contamination, although contamination was still possible when the unit of allocation was the physician ‐ not the care delivery centre. For example, Callahan 2006 used a cluster design but regarded the physician ‐ not the practice ‐ as the unit of allocation, meaning that control participants attending that practice could potentially receive care from intervention physicians.

Other potential sources of bias

Two studies had other potential sources of bias. One RCT (Llewelyn‐Jones 1999) used a controversial design and performed non‐concurrent assessment of control and intervention participants for pragmatic reasons, but this could have led to temporal bias, as study authors waited a year between assessments to avoid seasonal differences. This provoked commentary in the British Medical Journal as to whether the studies used a true RCT design (Deeks 1999). As a result of these issues, we reported this study (Llewelyn‐Jones 1999) alone and did not include study findings in any grouped analysis. A second RCT (Goderis 2010) reported very low participation rates for some of the physicians and participants involved.

NRCT designs

Three of the 42 included studies used an NRCT design. One was a controlled clinical trial for which we included two arms from a stepped wedge evaluation of a shared care model for depression (Solberg 2015). This study was at high risk of selection bias owing to lack of randomisation and incomplete outcome reporting, and the other risk of bias domains were unclear.

We included in the review two other NRCTs that used a CBA design (Meulepas 2007; Wood 1994). Meulepas 2007 incorporated baseline measurement but was at high risk of bias owing to lack of blinding, inadequate follow‐up and lack of randomisation. However, contamination was unlikely owing to the regional allocation of intervention and control general practices.

Wood 1994 met EPOC quality criteria for an NRCT in that it incorporated baseline measurements, blinded assessment of primary outcomes, used reliable outcomes and provided adequate participant follow‐up. We noted a unit of analysis error that occurred because study authors did not account for a potential clustering effect at the general practice level. In addition, as outlined previously, this study reported only preliminary data on process outcomes, with study authors stating their intention to publish health outcomes at a later date.

Certainty of the evidence

See Table 1. In general, although all included studies were RCTs, the main limitation of their findings was related to lack of consistency of effect for most outcomes. We regarded only evidence related to depression as having a high GRADE ranking. We downgraded the evidence to moderate for effects on all other outcomes owing to lack of consistency of effect across studies and small effect sizes. We did not include economic outcomes in Table 1 because we lacked robust economic analyses, rather we summarised this outcome in the main results and in additional tables.

Unit of analysis issues

Most of the cluster‐RCTs had incorporated clustering effects in both power calculations and analyses. Swindle 2003 and Warner 2000 explicitly incorporated clustering in their analyses but did not include a cluster effect in their power calculations, although Warner 2000 discussed this and presented data on the clustering effect, indicating that this study was underpowered when clustering was considered. Three of the included cluster‐RCTs had unit of analysis errors (Dey 2002; Donohoe 2000; Holm 2002), and Dey 2002 also included in its analysis patients described as a dynamic cohort (58 cases closed during the study and 46 new patients who entered the service, with unknown outcomes in all cases). None of these studies reported data that were included in meta‐analyses, so we made no adjustments to correct for these unit of analysis errors.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

In presenting review results, we included all studies as RCTs unless otherwise specified. We carried out meta‐analysis only when we considered this appropriate in relation to study characteristics and available data; we have presented these results only in forest plots. When we found differences between groups, we indicated this by inserting an asterisk (*) in the notes section of the additional tables.

1. Clinical outcomes

1.1 Clinical outcomes: physical health

Sixteen studies (15 RCTs and one CBA) evaluated effects of shared care on physical health outcomes (Dendale 2012; DICE 1994; Drummond 1994; Duran 2008; Fihn 2011; Goderis 2010; Hoskins 1992; Joubert 2009; Katon 2010; McGhee 1994; Meulepas 2007; Primdahl 2014; Rea 2004; Scherpbier‐de Haan 2013; Smith 2004; Smith 2008). These studies included participants with diabetes, hypertension, asthma and COPD, vascular conditions, musculoskeletal conditions or combinations of different conditions including cancer. Apart from providing beneficial but modest effects on blood pressure (BP), shared care probably leads to few or no differences in clinical outcomes. We have presented in Table 2 summary data regarding physical health outcomes.

1. Clinical outcomes: physical health.

| Study (condition) | Study type | Outcome | Results |

Notes *Statistically significant difference reported in trial |

| DICE (diabetes) | RCT | Mean HBA1c | Int: 5.3 (standard deviation (sd) 1.7). Con: 5.3 (sd 1.7). Absolute difference 0. Relative % difference 0%. | Standardised effect size (SES) = 0 |

| Hoskins (diabetes) | RCT | Mean HBA1c | Int: 6.6 (sd 1.6). Con: 7.3 (sd 1.6). Absolute difference 0.7. Relative % difference 9.6%. | SES = 0.47 |

| Smith 2004 (diabetes) | RCT | Mean HBA1c | Int: 7.0 (sd 1.6). Con: 6.7 (sd 1.5). Absolute difference 0.3. Relative % difference 4.5%. | SES = 0.19 |

| Katon 2010 (diabetes/CHD/ depression) | RCT | Mean HBA1c | Int: 7.33 (sd 1.21). Con: 7.81 (sd 1.9). Absolute difference 0.48. Relative % difference 6%. | SES = 0.31 |

| Goderis (diabetes) | RCT | Mean HBA1c | Int (AQIP): 6.7 (sd 1.01). Con (UQIP): 6.8 (sd 0.78). Absolute difference ‐0.1. Relative % difference 1%. | SES= 0.11 |

| Duran (diabetes) | RCT | % HBA1c < 7% | Int: 27/57. Con: 24/59. Absolute difference 4. Relative % difference 16.5%. | |

| Smith 2008 (diabetes) | RCT | % HBA1c < 7% | Int: 191/358. Con: 154/277. Absolute difference ‐2.2. Relative % difference 3.9%. | |

| Dice (diabetes) | RCT | Mean systolic BP | Int: 161.5 (sd 25.1). Con: 156.4 (sd 25.7). Absolute difference 5.1. Relative % difference 3.3%. | SES = 0.2 |

| Hoskins (diabetes) | RCT | Mean systolic BP | Int: 130 (sd 25). Con: 133 (sd 19). Absolute difference 3. Relative % difference 2%. | SES = 0.14 |

| Smith 2008 (diabetes) | RCT | Mean systolic BP | Int: 157.7 (sd 24.1). Con: 163.4 (sd 26.5). Absolute difference 5.7. Relative % difference 3.5%. | SES = 0.23 |

| Katon 2010 (diabetes/CHD/ depression) | RCT | Mean systolic BP | Int: 131 (sd 18.2). Con: 132 (sd 17.4). Absolute difference 0.7. Relative % difference 0.5%. | SES = 0.06* |

| Joubert (stroke) | RCT | Mean systolic BP | Int: 128.5 (sd 13.7). Con: 134.5 (sd 19.4). Absolute difference 6. Relative % difference 5%. | SES = 0.35* |

| Goderis (diabetes) | RCT | Mean systolic BP | Int (AQIP): 132 (sd 20.3) Con: 134 (sd 23.2) Absolute difference ‐2 Relative % difference 1.5 | SES = 0.09 |

| Scherpbier de Hann (CKD+) | RCT | Mean systolic BP | Int: 134.7 (sd 15.7). Con: 142.9 (sd 16.8). Absolute difference 8.2. Relative % difference 5.7%. | SES = 0.5* |

| McGhee (hypertension) | RCT | Mean systolic BP | Int: 147 (sd 21.8). Con: 150.2 (sd 17.9). Absolute difference 3.2. Relative % difference 2.3%. | SES = 0.16 |

| Scherpbier de Hann (CKD+) | RCT | % SBP meeting target < 130 mmHg | Int: 40/90. Con: 16/74. Absolute difference 22%. Relative % difference 100%. | |

| Duran (diabetes) | RCT | % SBP < 130 mmHg | Int: 23/57. Con: 29/59. Absolute difference 8%. Relative % difference 17.8%. | |

| Smith 2008 (diabetes) | RCT | % BP < 130/80 mmHg | Int: 146/358. Con: 128/277. Absolute difference ‐5. Relative % difference 11%. | |

| Dice (diabetes) | RCT | Mean BMI | Int: 28.7 (sd 7.6). Con: 27.9 (sd 4.5). Absolute difference 0.8. Relative % difference 2.8%. | SES = 0.13 |

| Hoskins (diabetes) | RCT | Mean weight (kg) | Int: 75 (sd 14). Con: 79 (sd 19). Absolute difference 4. Relative % difference 5%. | SES = 0.23 |

| Smith 2004 (diabetes) | RCT | Mean BMI | Int: 31.6 (sd 6.4). Con: 31 (sd 6.4). Absolute difference 0.6. Relative % difference 2%. | SES = 0.09 |

| Joubert (stroke) | RCT | Mean BMI | Int: 27.5 (sd 5.4). Con: 28.7 (sd 6.3). Absolute difference 1.2. Relative % difference 4%. | SES = 0.21* |

| Goderis (diabetes) | RCT | Mean BMI | Int: 29.2 (sd 2.0). Con: 29.2 (sd 2.3). Absolute difference 0. Relative % difference 0%. | SES = 0 |

| Duran (diabetes) | RCT | % BMI < 25 kg/m2 | Int: 7/57. Con: 13/59. Absolute difference ‐9.8. Relative % difference 44.3%. | * |

| Joubert (stroke) | RCT | Mean total cholesterol | Int: 4.9 (sd 1.0). Con: 5 (sd 1.0). Absolute difference 0.01. Relative % difference 2.0%. | SES = 0.1 |

| Goderis (diabetes) | RCT | Mean total cholesterol | Int: 174 (sd 40.5). Con: 180 (sd 38.6). Absolute difference ‐6. Relative % difference 3.3%. |

SES = 0.15 |

| Katon 2010 (diabetes/CHD/ depression) | RCT | Mean LDL cholesterol | Int 91.9 (sd 36.7) Con: 101.9 (sd 36.6) Absolute difference 10 Relative % difference 0.1% | SES = 0.27 |

| Goderis (diabetes) | RCT | Mean LDL cholesterol | Int (AQIP): 93 (sd 30.4). Con (UQIP): 98 (sd 30.9). Absolute difference ‐5. Relative % difference 5%. | SES = 0.16 |

| Duran (diabetes) | RCT | % cholesterol < 200 mg/dL | Int: 56/57. Con: 53/59. Absolute difference 8.2%. Relative % difference 9.1% | |

| Goderis (diabetes) | RCT | Mean HDL cholesterol | Int (AQIP): 55 (sd 20.2). Con (UQIP): 54 (sd 7.7). Absolute difference 1. Relative % difference 1.8. | SES = 0.07 |

| Smith 2008 (diabetes) | RCT | % LDL cholesterol< 130 mg/dL% | Int: 271/358. Con: 227/277. Absolute difference ‐6. Relative % difference 7.3%. | |

| Smith 2008 (diabetes) | RCT | % LDL cholersterol < 100 mg/dL% | Int: 184/358. Con: 139/277. Absolute difference 1. Relative % difference 2%. | |

| Drummond (asthma) | RCT | Mean peak flow rate | Int: 351 (sd 120). Con: 351 (sd 123). Absolute difference 0. Relative % difference 0%. | SES = 0 |

| Drummond (asthma) | RCT | Mean FEV1 as % predicted | Int: 76 (sd 28). Con: 75.2 (sd 27.2). Absolute difference 0.8. Relative % difference 1%. | SES = 0.03 |

| Meulepas (asthma) | RCT | % with exacerbations of asthma | Int: 70/87. Con: 55/79. Absolute difference 0.12. Relative % difference 17%. | |

| Rea (COPD) | RCT | Mean FEV1 as %predicted | Int: 53.9. Con: 45.6. Absolute difference 8.3. Relative % difference 18%. | No SD available* |

| Rea (COPD) | RCT | Shuttle walk test ‐ mean difference (metres) | Int: 303.3 m. Con: 283.4 m. Absolute difference 19.9. Relative % difference 7%. | No SD available |

| Primdahl (RA) | RCT | Disease activity score | Int: 16. Con: 17. Absolute difference 1.0. Relative % difference 6%. | No SD available |

| Dendale (heart failure) | RCT | All‐cause mortality | Int: 4/76. Con: 14/80. Absolute difference ‐12%. Relative % difference 71%. | * |

| Dendale (heart failure) | RCT | Mean days lost to death/patient | Int: 6.5 (sd 28.6). Con: 16.3 (sd 43.1). Absolute difference ‐9.8. Relative % difference 60%. | SES = 0.27* |

| Dendale (heart failure) | RCT | Mean days lost to dialysis/patient | Int: 3.1 (19.6). Con: 9.1 (36.6). Absolute difference ‐6. Relative % difference 66%. | SES = 0.21 |

| Fihn (ischaemic heart disease) | RCT | Adjusted difference in angina frequency (Seattle Angina Questionnaire) | Intervention effect coefficient 0.93. | |

| Fihn (ischaemic heart disease) | RCT | Adjusted difference in angina frequency (Seattle Angina Questionnaire) | Intervention effect coefficient 0.93. | |

| Fihn (ischaemic heart disease) | RCT | Adjusted difference in physical limitations (Seattle Angina Questionnaire) | Intervention effect coefficient 0.97. | |

| Fihn (ischaemic heart disease) | RCT | Adjusted difference in death | Intervention effect coefficient 0.01. |

HBA1c: glycolsylated haemoglobin.

BP: blood pressure.

BMI: body mass index.

LDL: low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol.

HDL: high‐density lipoprotein.

FEV1 : Forced Expiratory Volume in one second.

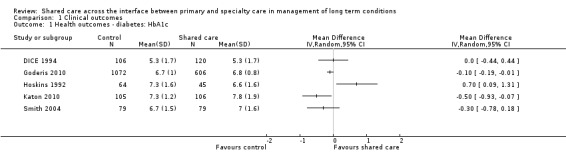

1.1.1 Diabetes

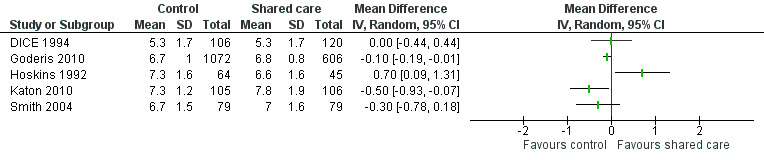

Seven studies targeted people with diabetes (DICE 1994; Duran 2008; Goderis 2010; Hoskins 1992; Katon 2010; Smith 2004; Smith 2008), and two of these reported clinically meaningful differences in mean glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c; i.e. > 0.5%) between groups receiving shared care and control groups (Hoskins 1992; Katon 2010). Five of these studies reported data that could be included in a meta‐analysis (Analysis 1.1). Results showed a limited difference in mean systolic blood pressure (SBP) within the diabetes studies (Analysis 1.2;Figure 4), with a difference in mean SBP of 2 mmHg. Four studies reported seven outcomes related to cholesterol levels (Duran 2008; Goderis 2010; Joubert 2009; Katon 2010), and only one of these noted improvement. Two of the six studies that examined body mass index (BMI) or weight (DICE 1994; Duran 2008; Goderis 2010; Hoskins 1992; Joubert 2009; Smith 2004) found limited or no differences between groups (Table 2).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Clinical outcomes, Outcome 1 Health outcomes ‐ diabetes: HbA1c.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Clinical outcomes, Outcome 2 Health outcomes ‐ systolic blood pressure.

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Clinical outcomes, outcome: 1.1 Health outcomes ‐ diabetes: HbA1c.

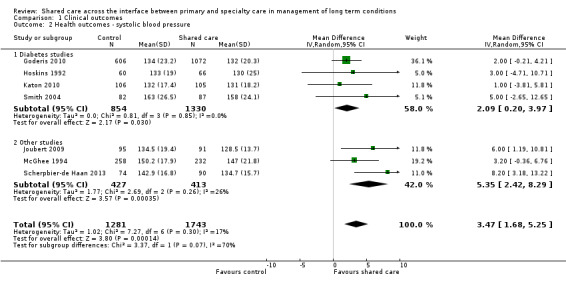

1.1.2 Hypertension

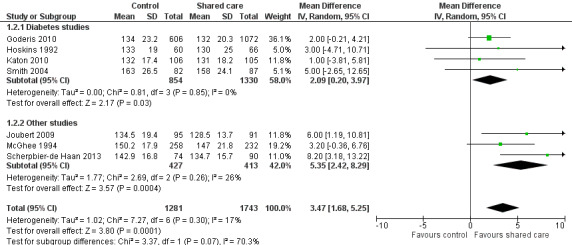

Only one study reported on a shared care scheme targeting patients with hypertension (McGhee 1994) and found limited or no difference in SBP between intervention and control participants. This study was incorporated in a subgroup of the SBP analysis (Figure 5). This meta‐analysis presents SBP outcomes in diabetes shared care studies and in other studies targeting BP and reveals a modest effect favouring shared care. We performed a sensitivity analysis while removing DICE 1994, as participants were recruited from specialist settings and this removed statistical heterogeneity. This analysis shows modest benefit of shared care for the range of conditions included in these studies (mean difference (MD) 3.47, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.68 to 5.25; Figure 5). However, this benefit is clinically modest.

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Clinical outcomes, outcome: 1.2 Health outcomes ‐ systolic blood pressure.

1.1.3 Respiratory conditions

Three studies targeted respiratory conditions ‐ asthma and COPD (Drummond 1994; Meulepas 2007; Rea 2004). Drummond 1994 reported two biophysical measures for asthma control ‐ peak flow rate (PFR) and forced expiratory volume in one minute (FEV1) ‐ and indicated limited or no differences between shared care and control groups. Rea 2004 reported a difference in FEV1 favouring participants in the shared care group but described limited or no difference in distance walked in the shuttle walk test between those receiving shared care and participants given conventional care. Meulepas 2007, a CBA, found limited or no effect on proportions of participants with exacerbations of COPD.

1.1.4 Vascular conditions

Three studies (Dendale 2012; Fihn 2011; Joubert 2009) examined shared care for different vascular conditions (Table 2). One study (Dendale 2012) reported lower all‐cause mortality (absolute difference of 12%) in the intervention group than in the group of controls with congestive heart failure. This same study reported a greater reduction in mean days lost to death per participant in the intervention group but no difference in mean days lost to dialysis per participant. Fihn 2011 reported no intervention effect on mortality, angina symptoms or physical limitations. Joubert 2009, which targeted people with cerebrovascular disease (CVA/TIA), reported improvement in BMI among participants given intervention but limited or no difference in SBP or cholesterol levels.

1.1.5 Musculoskeletal conditions

Primdahl 2014 examined collaborative care for patients with rheumatoid arthritis and reported limited or no difference in disease activation measures between intervention and control participants (Table 2).

1.1.6 Comorbidity and cancer studies

Three studies included participants with specific comorbid conditions (Katon 2004; Katon 2010; Scherpbier‐de Haan 2013), and one study included participants with cancer (Johannson 2001). Katon 2004 examined shared care for people with depression and diabetes and found limited or no difference in mean HbA1c between intervention and control participants. The intervention in this study was targeted specifically toward improving depression outcomes. Katon 2010 included participants with depression and diabetes and/or ischaemic heart disease. The primary outcome for this study was a composite measure of depression score (Symptom Checklist Depression Scale (SCL‐20)), HBA1c, SBP and cholesterol, and investigators reported greater improvement in this composite outcome at 12 months (P < 0.001). Scherpbier‐de Haan 2013 examined collaborative care for participants with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and diabetes/hypertension and found improvement in BP management in terms of mean BP and proportions of participant achieving target BP levels but limited or no difference in lipids, renal function, weight and a range of 22 other biomarkers between intervention and control participants.

1.2 Clinical outcomes: mental health

Eighteen studies presented data on mental health outcomes. Sixteen of these studies examined shared care for various forms of depression (Callahan 2006; Chew‐Graham 2007; Conradi 2007; Dobscha 2009; Fortney 2007; Huijbregts 2013; Katon 1999; Katon 2001; Katon 2004; Katon 2010; Llewelyn‐Jones 1999; Menchetti 2013; Richards 2008; Solberg 2015; Swindle 2003; Unutzer 2002). All were RCTs except one (Solberg 2015). Results showed a tendency towards improvement in mean depression scores (six of 11 studies reported differences) and proportions responding to depression treatment (six of eight studies reported a difference) or achieving remission (four of seven studies reported a difference). This was based on high certainty of evidence regarding depression outcomes.

One RCT (Muntingh 2013) examined shared care for anxiety disorders and reported improvements in anxiety and depression scores among shared care participants (Table 3).

2. 2 Clinical outcomes: mental health.

| Study (condition) | Study type | Outcome | Results |

Notes *Statistically significant difference reported in trial |

|

| Katon 2004 (depression) | RCT | Mean SCL‐20 score | Int: 1.5. Con: 1.16. Absolute difference ‐0.34. Relative % difference 29.3%. | SES 0.23 (calculated using baseline standard deviations)* | |

| Llewelyn‐Jones 1999 (depression) | RCT | Mean Geriatric Depression Scale score | Int: 11.8 (sd 4.7). Con: 12.6 (sd 4.1). Absolute difference 0.76. Relative % difference 6%. | SES = 0.17 | |

| Swindle 2003 (depression) | RCT | Mean Beck Depression Inventory score | Int: 21.4 (sd 10.5). Con: 22.5 (sd 10.8). Absolute difference 1.1. Relative % difference 4.8%. | SES = 0.1 | |

| Unutzer (depression) | RCT | Mean SCL‐20 score | Int: 0.99 (0.67). Con: 1.39 (0.67). Absolute difference 0.4. Relative % difference 29%. | SES = 0.6* | |

| Katon 2010 (diabetes/CHD/ depression) | RCT | Mean SCL‐20 score | Int: 0.83 (sd 0.68). Con: 1.14 (sd 0.66). Absolute difference 0.31. Relative % difference 27%. | SES = 0.46* | |

| Menchetti (depression) | RCT | Mean PHQ‐9 score | Int: 7 (sd 4.7). Con: 7.5 (sd 4.4). Absolute difference 0.5. Relative % difference 7%. | SES = 0.11 | |

| Muntingh (anxiety) | RCT | Mean PHQ‐9 score | Int: 4.87. Con: 6.6. Absolute difference 0.64. Relative % difference 7%. | *No standard deviations available | |

| Richards (depression) | RCT | Mean PHQ‐9 score | Int: 10.0 (sd 7.1). Con: 11.7 (sd 6.8). Absolute difference 1.7. Relative % difference 14.5%. | SES = 0.28* | |

| Richards (depression) | RCT | Mean GAD score | Int: 7.7 (sd 6.2). Con: 9.1 (sd 6.2). Absolute difference 1.4. Relative % difference 15%. | SES = 0.22 | |

| Katon 1999 (depression) | RCT | % remission/recovery from depression | Int: 50/114. Con: 35/ 114. Absolute difference 13%. Relative % difference 42%. | * | |

| Katon 2001 (depression) | RCT | % remission/recovery from depression | Int: 113/174. Con: 99/152. Absolute difference 0. Relative % difference 0%. | ||

| Katon 2004 (depression) | RCT | % response, 40% reduction from baseline SCL‐20 score | Int: 79/164. Con: 59/165. Absolute difference 12.4%. Relative % difference 35%. | * | |

| Fortney (depression) | RCT | % response to treatment (50% improvement in SCL‐20 score) | Int: 53/146. Con: 51/189. Absolute difference 9%. Relative % difference 33%. | ||

| Menchetti (depression) | % response to treatment (at least 50% decrease in PHQ‐9 score) | Int: 90/128. Con: 60/99. Absolute difference 9%. Relative % difference 15%. | * | ||

| Richards (depression) | RCT | % response to treatment (at least 50% decrease in PHQ‐9 score) | Int: 115/235. Con: 93/263. Absolute difference 13.5%. Relative % difference 38%. | * | |

| Richards (depression) | RCT | % recovery/remission (PHQ‐9 < 9) | Int: 131/235. Con: 106/263. Absolute difference 15.4%. Relative % difference 38%. | * | |

| Menchetti (depression) | RCT | % recovery/remission from depression (PHQ‐9 < 5) | Int: 76/128. Con: 55/99. Absolute difference 3%. Relative % difference 54%. | ||

| Unutzer (depression) | RCT | % recovery/remission from depression | Int: 398/889. Con: 165/870. Absolute difference 25%. Relative % difference 132%. | * | |

| Fortney (depression) | RCT | % recovery/remission from depression (SCL‐20 score < 0.5) | Int: 35/146. Con: 24/187. Absolute difference 11%. Relative % difference 85%. | * | |

| Katon 2010 (diabetes/CHD/ depression) | RCT | % response to treatment (50% improvement in SCL‐20 score) | Int: 56/94. Con: 28/92. Absolute difference 30%. Relative % difference 100%. | * | |

| Byng (chronic mental illness) | RCT | Mean severity of illness score | Int: 2.34. Con: 2.36. Absolute difference ‐0.02. Relative % difference 0.8%. | No standard deviations available | |

| Warner (chronic mental illness) | RCT | Mean BASIS score | Int: 1.21 (sd 0.88). Con: 1.27 (sd 0.86). Absolute difference ‐0.06. Relative % difference ‐4.7%. | SES = 0.07 | |

| Warner (chronic mental illness) | RCT | Mean BPRS score | Int: 16.9 (sd 9.8). Con: 13.8 (sd 8.6). Absolute difference 3.1. Relative % difference 22%. | SES = 0.34 | |

| Byng (chronic mental illness) | RCT | % experiencing psychiatric relapse | Int: 126/177. Con: 56/145. Absolute difference 32%. Relative % difference 84%. | *Adjusted absolute difference reported in paper was 0.28 (95% CI 0.08 to 0.49) | |

| Callahan (Alzheimer/depression) | RCT | Mean Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia | Int: 5.4 (sd 4.4). Con (augmented usual care): 4.2 (sd 3.9). Absolute difference 1.2. Relative % difference 29%. | SES = 0.29 | |

| Callahan (Alzheimer/depression) | RCT | Mean PHQ‐9 (caregiver) | Int: 3.1 (sd 4.5). Con (augmented usual care): 5.2 (5.3). Absolute difference ‐2.1. Relative % difference 40%. | SES = 0.43* | |

| Chew‐Graham (depression/older adults) | RCT | % with recovery/remission (5 or fewer symptoms on SCID Depression Scale) | Int: 36/45. Con: 26/43. Absolute difference 20%. Relative % difference 33%. | * | |

| Dobscha (chronic pain) | RCT | Mean PHQ‐9 depression | Int: 10.6 (sd 10.5). Con: 13.2 (sd 9.7). Absolute difference ‐2.6. Relative % difference 20%. Difference in absolute changes since baseline (‐2.5). | SES = 0.26 *Adjusted group difference in change in outcome over 12 months |

|

| Fihn (ischaemic heart disease) | RCT | Adjusted difference PHQ‐9 depression | Intervention effect coefficient 0.05. | i | |

| Vera (depression) | RCT | HSCL‐20 | Mean/sd not reported (improvement in intervention). | * | |

| Vera (depression) | RCT | % recovery/remission, at least 50% reduction in HSCL‐20 score at 6 months | Int: 50%. Con: 19%. Absolute difference 31. Relative % difference 163%. | * | |

| Huijbregts (depression) | RCT | % response, at least 50% reduction in PHQ‐9 scores at 12 months | Int: 16/39. Con: 24/94. Absolute difference 15.5. Relative % difference 60%. | ||

| Huijbregts (depression) | RCT | % recovery/remission (score < 5 on PHQ‐9) | Int: 8/39. Con: 6/94. Absolute difference 14.4. Relative % difference 229%. | ||

| Muntingh (anxiety) | RCT | Mean BAI score | Int: 12.2. Con: 16.8. Absolute difference 4.6. Relative % difference 27%. | *No standard deviations available |

SCL‐20: Symptom Checklist.

PHQ‐9: Patient Health questionnaire.

BASIS: Behavior and Symptom Identification Scale.

BPRS: Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale.

SCID: Structured Clinical Interview.

HSCL‐20: Hopkins Symptom Checklist Depression Scale.

BAI: Becks Anxiety Inventory.

Two RCTs (Byng 2004; Warner 2000) and one CBA (Wood 1994) targeted chronic mental illness and found no differences in shared care. We have presented summary outcome data in Table 3.

1.2.1 Depression

Eleven of the 16 studies examining shared care for depression presented depression outcomes as mean scores on validated depression scales and/or categorical depression outcomes. Eleven studies presented categorical data related to proportions recovered from depression or achieving remission, with a tendency towards improvement in response to treatment among intervention groups and limited effects on remission rates.

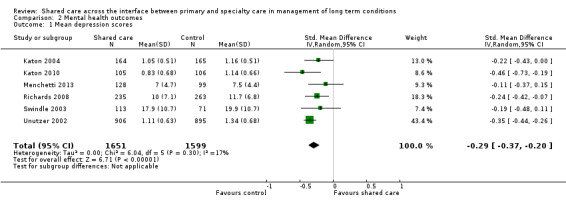

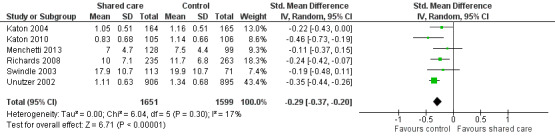

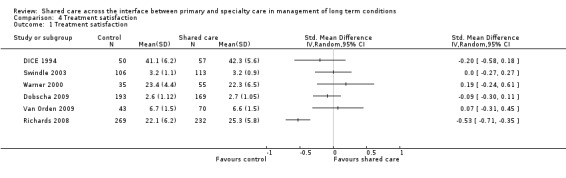

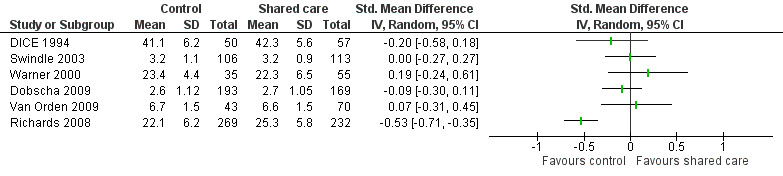

Eleven studies presented data related to mean depression scores (Katon 1999; Katon 2001; Katon 2004; Katon 2010; Llewelyn‐Jones 1999; Menchetti 2013; Richards 2008; Swindle 2003; Unutzer 2002; Van Orden 2009; Vera 2010). Two of these studies presented outcomes on graphs without providing raw data (Katon 1999; Katon 2001). Katon 1999 reported limited or no difference in mean depression score at six months between intervention and control groups; Katon 2001 reported benefit, with the intervention group having a lower mean score on the SCL‐20 depression scale at study completion (mean difference 0.08) (no data available for Table 2); Katon 2004, Katon 2010, Richards 2008, Unutzer 2002 and Vera 2010 reported improvement in mean depression scores, whereas Llewelyn‐Jones 1999, Menchetti 2013, Swindle 2003 and Van Orden 2009 found no differences between groups. We undertook a meta‐analysis of SMDs in depression scores among six studies, which showed a modest difference in these scores (RR ‐0.29, 95% CI ‐0.36 to ‐0.21; Analysis 2.1;Figure 6)..

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Mental health outcomes, Outcome 1 Mean depression scores.

6.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 Mental health outcomes, outcome: 2.1 Mean depression scores.

We included two arms from a stepped wedge evaluation of a shared care model for depression (Solberg 2015) and found limited or no difference in depression outcomes between participants who continued to receive usual care and those who received the shared care intervention. This study was at high risk of selection bias owing to lack of randomisation; therefore, we did not include it in the meta‐analysis.

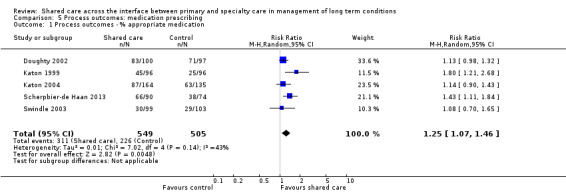

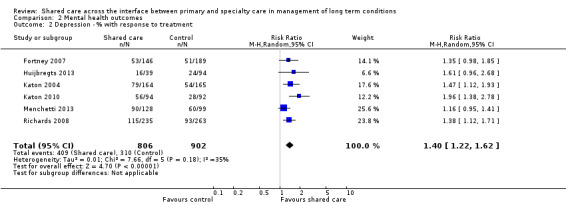

Eleven studies examined categorical outcomes related to depression (Chew‐Graham 2007; Fortney 2007; Huijbregts 2013; Katon 1999; Katon 2001; Katon 2004; Llewelyn‐Jones 1999; Menchetti 2013; Richards 2008; Unutzer 2002; Vera 2010). Eight of these studies examined response to depression treatment, with six showing important differences favouring shared care (Table 3). We undertook a meta‐analysis of this outcome, which showed an effect favouring shared care (RR 1.4, 95% CI 1.22 to 1.62; Figure 7).

7.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 Mental health outcomes, outcome: 2.2 Depression ‐ % with response to treatment.

Seven studies examined proportions achieving recovery or remission from depression. Four of these studies reported an effect (Table 3). We undertook a meta‐analysis of this outcome, but results were heterogeneous, so we have not reported a pooled result (Figure 8).

8.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 Mental health outcomes, outcome: 2.3 Depression remission/recovery.

Llewelyn‐Jones 1999 reported a shift from more severe to less severe depression in the intervention group compared with the control group. We did not include this study in the meta‐analysis, as we noted issues regarding the quality of its study design (see section on methodological quality of included studies (Types of studies)).

Callahan 2006 included participants with both depression and Alzheimer's disease and found limited or no difference in mean depression scores for participants or caregivers.

Four studies examined shared care for diabetes, asthma, chronic pain and cancer and included depression measures as secondary outcomes (DICE 1994; Dobscha 2009; Drummond 1994; Johannson 2001). DICE 1994 used a validated scale ‐ the diabetes health questionnaire (which included scores for anxiety and depression) ‐ and found limited or no difference in mean anxiety and depression scores between shared care participants and controls. Dobscha 2009 found limited or no difference in mean depression scores among participants with chronic pain. Drummond 1994 showed limited or no difference between shared care participants and controls in Hospital Anxiety and Depression (HAD) scores at study completion. Johannson 2001 also examined HAD scores among participants with cancer receiving shared care but included the data only as covariates in an analysis of effects on hospital admissions (presented in Section 1.4).

1.2.2 Anxiety disorders

One study examined shared care for anxiety disorders and reported improvement in both anxiety and related depression scores (Muntingh 2013).

1.2.3 Chronic mental illness (other)

Three studies examined shared care for chronic mental illness (Byng 2004; Warner 2000; Wood 1994). Outcomes were mixed. Byng 2004 found limited or no difference in mean severity of illness scores between intervention and control participants. Warner 2000 evaluated a simple shared care intervention ‐ a shared care record card alone ‐ and presented data on general mental health outcomes ‐ the Behaviour and Symptom Identification Scale (BASIS) and the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS). Investigators found limited or no differences between intervention and control groups at study completion. Byng 2004 reported an adjusted 28% absolute reduction (95% CI 8% to 49%) in numbers of shared care participants experiencing a psychiatric relapse. Wood 1994 also looked at shared care for patients with chronic mental illness but reported only outcomes related to hospital admissions.

2. Patient‐reported outcome measures (PROMs)

Eighteen studies examined PROMs and found probably mixed effects, as only half of the studies reporting these outcomes showed any benefit. We have presented these results in Table 4. Only six of 15 studies reporting on well‐being and quality of life found an effect. Five of nine studies reporting on measures of functional impairment, productivity and disability showed an effect favouring shared care. Twelve additional PROMs were reported across studies, and five of these showed an effect favouring shared care.

3. Patient‐reported outcome measures.

| Study (condition) | Study type | Outcome | Results | Notes |

| Byng (chronic mental illness) | RCT | Lack well‐being ‐ mean score | Int: 3.41. Con: 3.46. Absolute difference 0.05. Relative % difference 1%. | No standard deviations available |

| Dice (diabetes) | RCT | Mean DWBS in patients with Type 2 Diabetes | Int: 46.5 (sd 6.7). Con: 47.1 (sd 7.5). Absolute difference ‐ 0.6. Relative % difference ‐1%. | SES = 0.08 |

| Dice (diabetes) | RCT | Mean DWBS in patients with Type 2 Diabetes | Int: 65.3 (sd 11.2). Con: 67.5 (sd 12.4). Absolute difference ‐2.2. Relative % difference ‐3%. | SES = 0.19 |

| Smith 2004 (diabetes) | RCT | Mean DWBS | Int: 50.9 (sd 2.82). Con: 47.6 (sd 3.56). Absolute difference 3.3. Relative % difference 6.9%. | SES = 0.03* |

| Katon 2010 (diabetes/CHD/ depression) | RCT | Mean quality of life score | Int: 6.0 (sd 2.2). Con: 5.2 (sd 1.9). Absolute difference 0.8. Relative % difference 15%. | SES = 0.38* |

| Joubert (stroke) | RCT | Mean AQoL score | Int: 26.4 (sd 5.3). Con: 29.7 (sd 6.2). Absolute difference 3.3. Relative % difference 11%. | SES = 0.57* |

| Unutzer (depression) | RCT | Mean quality of life score | Int: 6.58 (sd 2.15). Con: 6.02 (sd 2.13). Absolute difference 0.56. Relative % difference 9%. | SES = 0.26* |

| Drummond (asthma) | RCT | Mean number of nights of disturbed sleep | Int: 2.4 (sd 1.6). Con: 2.4 (sd 1.4). Absolute difference 0. Relative % difference 0%. | SES = 0 |

| Drummond (asthma) | RCT | Mean number of days of restricted activity | Int: 5.7 (sd 6.9). Con: 4.8 (sd 7.3). Absolute difference 0.9. Relative % difference 19%. | SES = 0.13 |

| Katon 1999 (depression) | RCT | Mean Sheehan Disability Scale scores | Int: 3.4 (sd 2.5). Con: 4.1 (sd 2.5). Absolute difference 0.7. Relative % difference 17%. | SES = 0.28* |

| Joubert (stroke) | RCT | Mean Rankin score | Int: 1.2 (sd 1.1). Con: 1.9 (sd 1.2). Absolute difference 0.7. Relative % difference 37%. | SES = 0.61* |

| Joubert (stroke) | RCT | Mean Barthel Index score | Int: 19.1 (sd 2.2). Con: 17.8 (sd 3.8). Absolute difference 1.3. Relative % difference 7%. | SES = 0.43 |

| Katon 1999 (depression) | RCT | Mean SF‐36 score ‐ role limitation (emotional) | Int: 55.1 (sd 33.04). Con: 52.4 (sd 33.04). Absolute difference 2.7. Relative % difference 5%. | SES = 0.08 |

| Muntingh (anxiety) | RCT | Mean SF‐36 score | Int: 43.6. Con: 40. Absolute difference 3.6. Relative % difference 9%. | *No standard deviations available |

| Muntingh (anxiety) | RCT | EQ5D score | Int: 0.8. Con: 7. Absolute difference 0.1. Relative % difference 14%. | *No standard deviations available |

| Rea (COPD) | RCT | Mean SF‐36 score ‐ role limitation (emotional) | Int: 68.1. Con: 62. Absolute difference 6.1. Relative % difference 10%. | No standard deviations available |

| Fortney (depression) | RCT | Mean SF‐12 PCS score | Int: 30.1. Con: 28.3. Absolute difference 1.8. Relative % difference 6%. | No standard deviations available |

| Fortney (depression) | RCT | Mean SF‐12 MCS score | Int: 36.1. Con: 36.9. Absolute difference 0.8. Relative % difference 2%. | No standard deviations available |

| Unutzer (depression) | RCT | Mean functional impairment score | Int: 3.58 (sd 2.8). Con: 4.52 (sd 2.7). Absolute difference 0.94. Relative % difference 21%. | SES = 0.34* |

| Byng (chronic mental illness) | RCT | Total unmet need ‐ mean score | Int: 1.49. Con: 1.31. Absolute difference 0.18. Relative % difference 14%. | No standard deviations available |

| Joubert (stroke) | RCT | MMSE score | Int: 21 (sd 4). Con: 19 (sd 5.2). Absolute difference 2. Relative % difference 11%. | SES = 0.43 |

| Katon 2010 (diabetes/CHD/ depression) | RCT | % better on global improvement score | Int: 41/92. Con: 16/91. Absolute difference 27%. Relative % difference 153%. | * |

| Callahan (Alzheimer) | RCT | Mean Neuropsychiatric Inventory score | Int: 8.4 (sd 10.2). Con (augmented usual care): 16.2 (sd 18.7). Absolute difference ‐7.8. Relative % difference 48%. | SES = 0.54* |

| Callahan (Alzheimer) | RCT | Mean Neuropsychiatric Inventory score (caregiver portion of NPI) | Int: 4.6 (sd 6.3). Con: 7.4 (9.7) (augmented usual care). Absolute difference ‐2.8. Relative % difference 38%. | SES = 0.35 |

| Callahan (Alzheimer) | RCT | Mean activities of daily living | Int: 45.7 (sd 20.1). Con (augmented usual care): 42.1 (16.8). Absolute difference 3.6. Relative % difference 8.6%. | SES = 0.20 |

| Chew‐Graham (depression/older adults) | RCT | Mean Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) ‐ Pain | Int: 0.64 (sd 0.88). Con: 1.11 (sd 1.06). Absolute difference ‐0.47. Relative % difference 42%. | SES = 0.48 |

| Chew‐Graham (depression/older adults) | RCT | Mean Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) ‐ Disability | Int: 0.78 (sd 0.74). Con: 1.05 (sd 0.75). Absolute difference ‐0.27. Relative % difference 26%. | SES = 0.36 |

| Dobscha (chronic pain) | RCT | Mean pain RMDQ | Int: 13.3 (sd 2.8). Con: 14.3 (sd 5.2). Absolute difference ‐1. Relative % difference 7%. Difference in absolute changes since baseline (‐1.2). | SES = 0.25 *Adjusted group difference in change in outcome over 12 months. |

| Dobscha (chronic pain) | RCT | % achieving 30% reduction in RMDQ scores over 12 months | Int: 21.9%. Con: 14%. Absolute difference 7.9. Relative % difference 56%. | *Adjusted |

| Dobscha (chronic pain) | RCT | Mean Chronic Pain Grade intensity | Int: 63.2 (sd 17.4). Con: 65.6 (sd 17.2). Absolute difference ‐2.3. Relative % difference 3.5%. Difference in absolute changes since baseline (‐4.64). | SES = 0.13 *Adjusted group difference in change in outcome over 12 months |

| Dobscha (chronic pain) | RCT | Mean Chronic Pain Grade pain interference subscale | Int: 44.6 (sd 26.9). Con: 51.1 (sd 26.1). Absolute difference ‐6.5. Relative % difference 13%. Difference in absolute changes since baseline (‐8). | SES = 0.25 *Adjusted group difference in change in outcome over 12 months |

| Dobscha (chronic pain) | RCT | Mean EQ5D QOL | Int: 0.64 (sd 0.21). Con: 0.60 (sd 0.22). Absolute difference 0.04. Relative % difference 6.7%. Difference in absolute changes since baseline (0.02). | SES = 0.19 |

| Fihn (ischaemic heart disease) | RCT | Adjusted difference disease perception | Intervention effect coefficient ‐0.02. | |

| Fihn (ischaemic heart disease) | RCT | Adjusted difference general self‐rated health (Veterans Rand 12‐Item Health Survey) | Intervention effect coefficient 0.37. | |

| Fihn (ischaemic heart disease) | RCT | Adjusted difference Physical Component Summary (Veterans Rand 12‐Item Health Survey) | Intervention effect coefficient ‐0.08. | |

| Fihn (ischaemic heart disease) | RCT | Adjusted difference Mental Component Summary (Veterans Rand 12‐Item Health Survey) | Intervention effect coefficient ‐0.20. | |

| Solberg (depression) | CCT | Productivity loss score | Int: 31. Con: 24.5. Absolute difference 6.5. Relative % difference 26%. | *No standard deviations |

| Van Orden (mental health) | RCT | Mean psychopathology subscale SCL‐90 | Int: 158.9 (sd 64.6). Con: 154.4 (sd 52.4). Absolute difference 4.5. Relative % difference 2.9%. | SES = 0.08 |

| Van Orden (mental health) | RCT | Mean WHOQOL‐BREF | Int: 3.3 (sd 9). Con: 3.3 (sd 7). Absolute difference 0. Relative % difference 0%. | SES = 0 |

| Vera (depression) | RCT | Social Functioning SF‐36 | Mean/sd not reported (improvement in intervention). | * |

DWBS: Diabetes well‐being score.

AQoL: Assesment of quality of life.

EQ5D: EuroQol five dimensions questionnaire.

SF‐12: Short form 12.

SF‐36: Short form 36.

WHOQOL‐BREF: World Health Organisation Quality of Life.

2.1 Well‐being and quality of life