Abstract

Background: Central Asia is the center of origin and diversification of the Artemisia genus. The genus Artemisia is known to possess a rich phytochemical diversity. Artemisinin is the shining example of a phytochemical isolated from Artemisia annua, which is widely used in the treatment of malaria. There is great interest in the discovery of alternative sources of artemisinin in other Artemisia species. Methods: The hexane extracts of Artemisia plants were prepared with ultrasound-assisted extraction procedures. Silica gel was used as an adsorbent for the purification of Artemisia annua extract. High-performance liquid chromatography with ultraviolet detection was performed for the quantification of underivatized artemisinin from hexane extracts of plants. Results: Artemisinin was found in seven Artemisia species collected from Tajikistan. Content of artemisinin ranged between 0.07% and 0.45% based on dry mass of Artemisia species samples. Conclusions: The artemisinin contents were observed in seven Artemisia species. A. vachanica was found to be a novel plant source of artemisinin. Purification of A. annua hexane extract using silica gel as adsorbent resulted in enrichment of artemisinin.

Keywords: Artemisia species, Artemisia vachanica, artemisinin, HPLC-PAD, Tajikistan

1. Introduction

As reported by the World Health Organization (WHO), in the last four years (2015–2018), nearly half of the population of the world (3.2 billion people) was at risk of malaria. In 2017, there were 435,000 deaths from malaria globally, 61% (266,000) of which were of children younger than five years [1].

At present, artemisinin-based combination treatments are effective and accepted as being among the best malaria treatments [2]. Artemisinin is the bioactive compound produced by the plant Artemisia annua L. Artemisinin has saved the lives of millions of malarial patients worldwide and served as the standard regimen for treating Plasmodium falciparum infection [3].

With 500 species, the genus Artemisia L. is the largest and the most widely distributed genus of the Asteraceae, and Central Asia is the center of origin and diversification of the genus [4]. Many Artemisia species grow in Tajikistan [5]. The genus Artemisia is known to possess rich phytochemical diversity [6,7,8,9]. Almost 600 secondary metabolites have been characterized from A. annua alone [10].

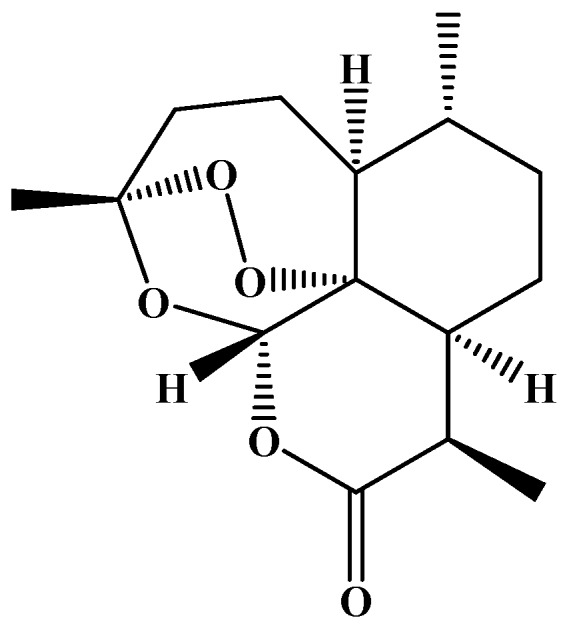

Artemisinin is the shining example of a phytochemical isolated from A. annua, and is widely used in the treatment of malaria. Artemisinin is a natural sesquiterpene lactone with an unusual 1,2,4-trioxane substructure (Figure 1). It is soluble in most aprotic solvents and is poorly soluble in water. It decomposes in protic solvents, probably by the opening of the lactone ring [11]. The artemisinin biosynthesis proceeds via the tertiary allylic hydroperoxide, which is derived from the oxidation of dihydroartemisinic acid [10].

Figure 1.

Artemisinin structure.

The mechanism of artemisinin action is controversial [12,13]. It is related to the presence of an endoperoxide bridge, which by breaking creates a powerful free radical form of the artemisinin, which attacks the parasite proteins without harming the host [14].

The presence of artemisinin has been reported in many Artemisia species, including A. absinthium, A. anethifolia, A. anethoides, A. austriaca, A. aff. tangutica, A. annua, A. apiacea, A. bushriences, A. campestris, A. cina, A. ciniformis, A. deserti, A. diffusa, A. dracunculus, A. dubia, A. incana, A. indica, A. fragrans, A. frigida, A. gmelinii, A. japonica, A. khorassanica, A. kopetdaghensis, A. integrifolia, A. lancea, A. macrocephala, A. marschalliana, A. messerschmidtiana, A. moorcroftiana, A. parviflora, A. pallens, A. roxburghiana, A. scoparia, A. sieberi, A. sieversiana, A. spicigeria, A. thuscula, A. tridentata, A. vestita, and A. vulgaris [9,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32].

The chemical structure of artemisinin provided a foundation for several synthetic antimalarial drugs including pyronaridine, lumefantrine (benflumetol), naphthoquine, and so on [33]. Recently, research interest in biotechnological approaches for enhanced artemisinin production in Artemisia have increased due to the global needs and low amounts of artemisinin and its derivatives in Artemisia plants [34]. Various biotechnological approaches such as the transformation of genes for production of artemisinin to cells of eukaryotic and prokaryotic organisms and to genetically engineered yeast were developed to enhance the production of artemisinin and its derivatives [35,36,37,38].

In addition, artemisinin and its bioactive derivatives have a second career as antitumor agents [39]. They demonstrated high efficiency against a variety of cancer cells, with minor side effects to normal cells in cancer patients [40,41]. The investigation of the biological activity of Artemisia species and their constituents is required to explore the full potential of diverse Artemisia species and their chemical ingredients against cancer, malaria, and infections [42]. Artemisinin can also exert beneficial effects in treatment of the wide-spectrum diseases such as obesity, diabetes, and aging-related disorders [43].

Natural conditions influence the biotransformation and accumulation of artemisinin in plants. For example, Ferreira et al. reported that that biosynthesis of artemisinin is affected by light intensity [44]. The relatively large number of sunny days per year in Tajikistan is essential for artemisinin accumulation in Artemisia species.

Accordingly, there is great interest in the discovery of artemisinin in Artemisia species growing wild in Tajikistan. The purpose of the current investigation was to evaluate the presence of artemisinin in eight Artemisia species.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials

The aerial parts of eight Artemisia species including A. annua, A. vachanica, A. vulgaris, A. makrocephala, A. leucotricha, A. dracunculus, A. absinthium, and A. scoparia were collected during their vegetative and flowering period from three regions of Tajikistan. The voucher specimen numbers, local names, collection time, and location of plants are summarized in Table 1. These species were identified with regards to specimens in the herbarium of the Institute of Botany, Plant Physiology and Genetics of Tajikistan Academy of Sciences. The voucher specimens of the plant material were deposited at the Chinese‒Tajik Innovation Center for Natural Products research institution of the Tajikistan Academy of Sciences.

Table 1.

Artemisia species collected from Tajikistan.

| Species | Local Name | Collection Site | Time | Voucher Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. annua | гoвҷoрӯб (govjorub), бурғун (burghun) | Ziddeh, Varzob Region | 15.07.2018 | CTICNPG 2018 - 5 |

| A. vachanica | пуши oддӣ (pushi oddi) | Khaskhorugh, Ishkoshim Region | 25.08.2018 | CTICNPG 2018 - 6 |

| A. vulgaris | cафедҷoрӯб (safedjorub), явшoн (yavshon) | Khaskhorugh, Ishkoshim Region | 22.08.2018 | CTICNPG 2018 - 7 |

| A. mackrocephala | пуши калoнгул (pushi kalongul) | Khaskhorugh, Ishkoshim Region | 21.08.2018 | CTICNPG 2018 - 8 |

| A. leucotricha | пуши сафед (pushi safed) | Khaskhorugh, Ishkoshim Region | 22.08.2018 | CTICNPG 2018 - 9 |

| A. dracunculus | тархун (tarkhun), ғӯда (ghuda) | Ziddeh, Varzob Region | 15.07.2018 | CTICNPG 2018 - 10 |

| A. absinthium | тaхач (takhach) | Guli Bodom, Yovon Region | 20.07.2018 | CTICNPG 2018 - 11 |

| A. scoparia | туғак (tughak), маҳинҷoрӯб (mahinjorub) | Guli Bodom, Yovon Region | 20.07.2018 | CTICNPG 2018 - 12 |

2.2. Preparation of Hexane Extracts

The extraction process of dried aerial parts of Artemisia plants were prepared by the following procedure: 10 g of plant materials were crushed into smaller pieces and weighed in a 250-mL flask, into which 150 mL of hexane were added at room temperature. The prepared plant mixtures were sonicated in an ultrasonic bath at a frequency of 35 kHz for 15 min at room temperature. Then, plant mixtures were allowed to stand for 12 h at room temperature. After 12 h, they were filtered through Whatman filter paper and used for the designed chemical analysis.

The yield of hexane extracts were calculated using following Equation (1):

| (1) |

where is the yield of hexane extract (%), a is the weight of hexane extract; and b is the weight of plant sample.

2.3. Quantitative Analysis of Artemisinin Using HPLC

A number of studies have been addressed for the development of HPLC methodology for quantification of artemisinin in plant material and extracts [44,45]. The best separation of artemisinin was achieved on columns Luna 5 μm C18 250 × 4.6 mm (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA) and Betasil C18 5 μm 250 × 4.6 mm (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), using acetonitrile:water (65:35, v/v) as the mobile phase [44,45].

In addition, artemisinin analysis by HPLC-PAD at 192 nm, compared to HPLC with evaporative light scattering detection (HPLC-ELSD), was very accurate, precise, and reproducible [44].

Artemisia extracts were analyzed by HPLC UltiMate 3000 system with DAD detector (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Extracts of Artemisia plants (10 mg/mL) were prepared in methanol and the solution was filtered using a 0.45-µm syringe filter for HPLC analysis. Analysis was performed on a Waters Bridge C18 5 μm (250 × 4.6 mm, Waters, Milford, MA, USA) and XSelect CSHTM C18 5 μm (250 × 4.6 mm, Waters, Milford, MA, USA) columns. The mobile phase consisted of water (A) and acetonitrile (B). The gradient elution program was as follows: 0–7 min, hold 60% of B; 17–30 min, 60–100% of B; 30–35 min, 100% of B. The detection wavelengths were 192, 210, 254, and 320 nm, the flow rate was 1 mL/min, the injection volume was 5 µL, and the oven temperature was set to 30 °C.

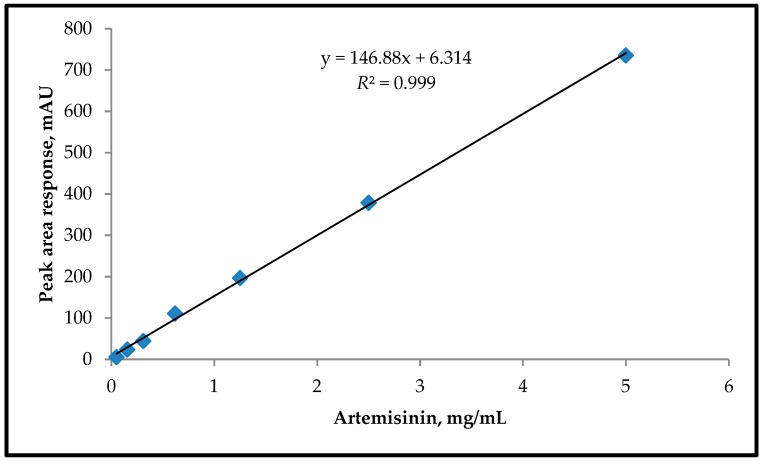

Quantification of the artemisinin was performed using a linear calibration graph with increasing amounts of artemisinin and their peak area response with UV detection (192 nm) (Figure 2). Standard solutions with seven different concentrations (between 0.05 and 5 mg/mL) were prepared by solving the standard artemisinin in methanol.

Figure 2.

Linear calibration graph for the standard artemisinin.

2.4. Purification of Artemisia annua Extract

Silica gel as adsorbent (10.0 g dry weight) was added to 100 mL of A. annua extract (10 mg/mL in hexane) in a 250-mL flask while agitating on a shaker at room temperature until the adsorption reached equilibrium. After reaching the adsorption equilibrium, the silica gel was filtered from the mixture and then washed with hexane 3–4 times until decolorization of the filtrate. The filtrate was evaporated using a rotary evaporator.

3. Results

The yields of hexane extract, number of components detected at 192 nm, and content of artemisinin per dry weight plant are summarized in Table 2. The hexane percentage yield of Artemisia species ranged from 2.3% to 8.1%. The hexane extract of A. vachanica had the highest yield (8.1%), followed by A. annua (5.8%) and A. absinthium (5.4%), while A. vulgaris had the lowest yield (2.3%). A total of 83, 90, 95, 94, 75, 100, 98, and 90 components (peaks on the chromatograms) were detected in A. annua; A. vachanica; A. vulgaris; A. makrocephala; A. leucotricha; A. dracunculus; A. absinthium, and A. scoparia, respectively.

Table 2.

Extraction yield, componential composition, and artemisinin content in Artemisia species.

| Species | Yield of Hexane Extract, % | Number of Components | Content of Artemisinin in Dry Weight Plant, % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Artemisia annua | 5.80 ± 0.05 | 83 | 0.45 ± 0.03 |

| Artemisia vachanica | 8.09 ± 0.1 | 90 | 0.34 ± 0.02 |

| Artemisia vulgaris | 2.32 ± 0.02 | 95 | 0.18 ± 0.01 |

| Artemisia makrocephala | 3.01 ± 0.02 | 94 | 0.20 ± 0.01 |

| Artemisia leucotricha | 3.19 ± 0.03 | 75 | Not detected |

| Artemisia dracunculus | 3.78 ± 0.04 | 100 | 0.07 ± 0.01 |

| Artemisia absinthium | 5.41 ± 0.0.5 | 98 | 0.09 ± 0.01 |

| Artemisia scoparia | 3.39 ± 0.02 | 90 | 0.11 ± 0.02 |

The content of artemisinin per dry weight of Artemisia species ranged from 0.07% to 0.45%. The highest content of artemisinin was observed in A. annua (0.45%), followed by A. vachanica (0.34%), while A. dracunculus had the lowest artemisinin content (0.07%). The HPLC chromatograms of Artemisia species with standard of artemisinin are showed in Figures S1–S5.

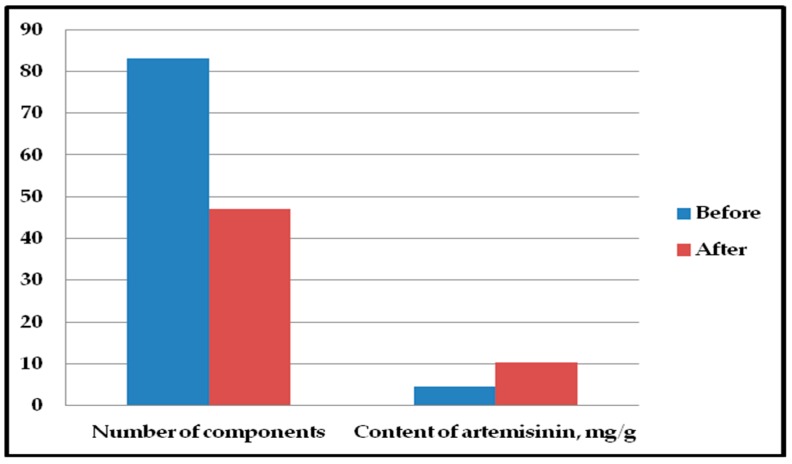

After treatment of A. annua extract with silica gel as an adsorbent, the total peaks in the chromatograms decreased from 83 to 47, while the content of artemisinin in A. annua extract increased from 4.5 mg/g to 10.2 mg/g. The results of A. annua extract treatment are given in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Total components number and artemisinin content in A. annua extract before and after purification.

4. Discussion

There are many factors such as environmental, genetic, etc. that can influence the variation in artemisinin concentration [17]. Ranjbar and co-authors have reported that there is a relationship between the increased expression of some genes and the enhancement of artemisinin content in Artemisia species at the vegetative, budding, and flowering stages [22]. Recently, Salehi et al. investigated the expression of artemisinin biosynthesis and trichome formation genes in five Artemisia species and concluded that there is a relationship between the enhancement of artemisinin content and increased expression of some genes [23].

Previous works have reported that artemisinin concentration varied due to differences in methods of artemisinin extraction as well as the solvents used [40,41]. Literature reports indicated that extraction of artemisinin has been carried out by different extraction methods: traditional solvent extraction, microwave-assisted extraction, ultrasound-aided extraction, and supercritical fluid extraction method using CO2 as a solvent [20,46]. n-hexane [38], toluene [40], chloroform [41], petroleum ether [44], acetone, and ethanol [47] were the solvents most widely used for artemisinin extraction from Artemisia species.

According to our results, ultrasound-aided extraction and n-hexane as a solvent for artemisinin extraction were suitable for the extraction of artemisinin from Artemisia species. Our experiments are in agreement with previous reports that the yield of artemisinin extraction is enhanced by ultrasound-aided extraction when compared to comparable conventional extraction processes [46].

Various methods such as thin-layer chromatography (TLC), high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with evaporative light scattering detection (ELSD), ultraviolet detection (PAD), diode array detection (DAD), gas chromatography (GC) combined with flame ionization detector (FID), and mass spectrometry (MS) have been proposed and assessed to detect and quantify artemisinin [48,49]. Recently, a fully electrochemical molecularly imprinted polymer sensor was developed for the sensitive detection of artemisinin with a detection limit of 0.02 μM in plant matrix [50].

In the present work, HPLC-PAD was used to analyze artemisinin in Artemisia species. Researchers have reported that HPLC-PAD is readily applicable for quality control of herbals and artemisinin-related pharmaceutical compounds and it was validated for the quantification of underivatized artemisinin, dihydroartemisinic acid, and artemisinic acid from crude plant samples [44].

The literature reports with respect to artemisinin content in Artemisia species up to now are summarized in Table 3. Artemisinin was found at least in 40 Artemisia species [9,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32]. The artemisinin content ranged from 0.0005% to 1.38% on dried parts of Artemisia species.

Table 3.

Summary of literature reports showing presence of artemisinin in Artemisia species.

| Artemisia Species | Part Used | Artemisinin, % | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| A. absinthium | Flowers, leaves, stem, and roots | 0.02–0.35 | [17,22,24] |

| A. austriaca | Leaves | 0.05 | [23] |

| A. aff. tangutica | Flowers, leaves, stem, and roots | 0.02–0.11 | [17] |

| A. anethifolia | Leaves | 0.05 | [30] |

| A. anethoides | Leaves | 0.006 | [30] |

| A. annua | Flowers, leaves, stem, and roots | 0.02–1.4 | [17,25,26,27,28,51,52] |

| A. arborescens | Leaves | 0.001 | [30] |

| A. apiacea | Leaves | Not shown | [21] |

| A. bushriences | Flowers, leaves, stem, and roots | 0.01–0.34 | [17] |

| A. campestris | Leaves, buds, and flowers | 0.05–0.1 | [22] |

| A. cina | Shoots | 0.0006 | [16] |

| A. ciniformis | Leaves | 0.22 | [23] |

| A. deserti | Leaves | 0.4–0.6 | [23] |

| A. diffusa | Leaves, buds, and flowers | 0.05–0.15 | [22] |

| A. dracunculus | Flowers, leaves, stem, and roots | 0.01–0.27 | [17] |

| A. dubia | Flowers, leaves, stem, and roots | 0.01–0.07 | [17,19] |

| A. incana | Leaves | 0.25 | [23] |

| A. indica | Flowers, leaves, stem, and roots | 0.01–0.10 | [17,19] |

| A. fragrans | Leaves | 0.2 | [23] |

| A. frigida | Leaves | 0.007 | [30] |

| A. gmelinii | Leaves | 0.038 | [30] |

| A. japonica | Flowers, leaves, stem, and roots | 0.01–0.08 | [17] |

| A. kopetdaghensis | Leaves | 0.18 | [23] |

| A. integrifolia | Leaves | 0.036 | [30] |

| A. lancea | Leaves | Not shown | [21] |

| A. macrocephala | Leaves | 0.011 | [30] |

| A. marschalliana | Leaves | 0.38 | [23] |

| A. messerschmidtiana | Leaves | 0.032 | [30] |

| A. moorcroftiana | Flowers, leaves, stem, and roots | 0.01–0.16 | [17] |

| A. parviflora | Flowers, leaves, stem, and roots | 0.03–0.15 | [17] |

| A. pallens | Leaves and flowers | 0.1 | [31] |

| A. roxburghiana | Flowers, leaves, stem, and roots | 0.02–0.22 | [17] |

| A. scoparia | Leaves, buds, and flowers | 0.1–0.18 | [22,32] |

| A. sieberi | Aerial parts | 0.1–0.2 | [22,23] |

| A. sieversiana | Flowers, leaves, stem, and roots | 0.05–0.20 | [17] |

| A. spicigeria | Leaves, buds, and flowers | 0.05–0.14 | [22] |

| A. thuscula (syn. A. canariensis) | Leaves | 0.045 | [30] |

| A. tridentata Nutt. subsp. vaseyana | Leaves | 0.0005 | [30] |

| A. vestita | Flowers, leaves, stem, and roots | 0.04–0.20 | [17] |

| A. vulgaris | Flowers, leaves, stem, and roots | 0.02–0.18 | [17,22] |

The highest content of artemisinin was found in A. annua (up to 1.4%) [51], followed by A. deserti (0.4–0.6%), A. marschalliana (up to 0.38%) [23] and A. absinthium (up to 0.35%) [17,22,24].

The current study observed the presence of artemisinin in eight of the various Artemisia species growing wild in Tajikistan. A. vachanica was found to be a novel plant source of artemisinin. The content of artemisinin in A. macrocephala was found almost 20-fold higher than a previous study [30]. Hence, no significant difference was detectable between the artemisinin content of A. annua, A. absinthium, A. dracunculus, and A. vulgaris growing in Tajikistan. Generally, previous studies reported that the artemisinin content in A. annua was higher than in other Artemisia species [15,17,21,22,24]. Artemisinin was not detected in A. leucotricha.

The extracts obtained from plant material using organic solvent extractions are very complex, and have several unwanted components such as chlorophylls and other colored organic molecules from the feed material. Removal of the contaminants from the extracts has been performed with charcoal and clays [53,54].

In this work, purification of A. annua hexane extract by using silica gel as adsorbent resulted in the enrichment of artemisinin. The concentration of artemisinin increased 2.3 times and 35 unwanted components were purified out by silica gel.

A selective sorption method has resulted in the increase of artemisinin to a final purity up to 90% using a polymeric adsorbent loaded with specific ligands [53]. Using silica gel compared to an adsorbent with specific ligands was less effective. However, silica gel is a cheap alternative that can be used for primary treatment of crude artemisinin extracts from the feed material.

5. Conclusions

The study demonstrated the presence of artemisinin, a biologically important natural sesquiterpene lactone in several Artemisia species growing wild in Tajikistan. The content of artemisinin ranged between 0.07% and 0.45% on a dry weight basis of Artemisia species. A. vachanica was found to be a novel plant source of artemisinin. Treatment of A. annua hexane extract with silica gel as adsorbent resulted in enrichment of artemisinin.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for financial support from the Central Asian Drug Discovery & Development Centre of Chinese Academy of Sciences (Grant No. CAM201808) and PIFI PostDoctoral scholarship for Sodik Numonov (No. 2019PB0043).

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at http://www.mdpi.com/2305-6320/6/1/23/s1, Figure S1: HPLC chromatogram of the pure artemisinin (Rt 4.257 min) (A) and hexane extract of Artemisia annua (B), Figure S2: HPLC chromatogram of hexane extract of Artemisia vachanica (A) and Artemisia vulgaris (B), Figure S3: HPLC chromatogram of hexane extract of Artemisia makrocephala (A) and Artemisia leucotricha (B), Figure S4: HPLC chromatogram of hexane extract of Artemisia dracunculus (A) and Artemisia absinthium (B), Figure S5: HPLC chromatogram of hexane extract of Artemisia scoparia (A) and mixture Artemisia annua and pure artemisinin (B).

Author Contributions

F.S., S.N., and S.A. performed the phytochemical investigation, designed the study, and wrote the manuscript; F.S., P.S., and A.S. analyzed the data; R.S., M.H., and H.A.A. made revisions to the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.WHO . World Malaria Report 2018. WHO; Geneva, Switzerland: 2018. p. 165. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nosten F., White N.J. Artemisinin-Based Combination Treatment of Falciparum Malaria. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2007;77:181–192. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2007.77.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guon Z. Artemisinin anti-malarial drugs in china. Acta Pharm. Sin. B. 2016;6:115–124. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2016.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanz M., Vilatersana R., Hidalgo O., Garcia-Jacas N., Susanna A., Schneeweiss G.M., Valls J. Molecular phylogeny and evolution of floral characters of Artemisia and Allies (Anthemideae, Asteracea): Evidence from nrdna ets and its sequences. Taxon. 2008;57:66–78. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharopov F., Setzer W.N. Medicinal plants of Tajikistan. In: Egamberdieva D., Öztürk M., editors. Vegetation of Central Asia and Environs. Springer Nature; Cham, Switzerland: 2018. pp. 163–210. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharopov F.S., Sulaimonova V.A., Setzer W.N. Composition of the essential oil of Artemisia absinthium from Tajikistan. Rec. Nat. Prod. 2012;6:127–134. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharopov F.S., Setzer W.N. Thujone-rich essential oils of Artemisia rutifolia stephan ex spreng. Growing wild in Tajikistan. J. Essent. Oil-Bear. Plants. 2011;14:136–139. doi: 10.1080/0972060X.2011.10643913. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharopov F.S., Setzer W.N. The essential oil of Artemisia scoparia from Tajikistan is dominated by phenyldiacetylenes. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2011;6:119–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tan R.X., Zheng W.F., Tang H.Q. Biologically active substances from the genus Artemisia. Planta Med. 1998;64:295–302. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-957438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown G.D. The biosynthesis of artemisinin (qinghaosu) and the phytochemistry of Artemisia annua L. (qinghao) Molecules. 2010;15:7603–7698. doi: 10.3390/molecules15117603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rydén A.M., Kayser O. Bioactive Heterocycles III. Volume 9. Springer; Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: 2007. Chemistry, biosynthesis and biological activity of artemisinin and related natural peroxides; pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yarnell E. Artemisia annua (sweet annie), other Artemisia species, artemisinin, artemisinin derivatives, and malaria. J. Restor. Med. 2014;3:69–85. doi: 10.14200/jrm.2014.3.0105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krishna S., Uhlemann A.C., Haynes R.K. Artemisinins: Mechanisms of action and potential for resistance. Drug Resist. Updat. 2004;7:233–244. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meshnick S.R. Artemisinin: Mechanisms of action, resistance and toxicity. Int. J. Parasitol. 2002;32:1655–1660. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7519(02)00194-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arab H.A., Rahbari S., Rassouli A., Moslemi M.H., Khosravirad F.D.A. Determination of artemisinin in Artemisia sieberi and anticoccidial effects of the plant extract in broiler chickens. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2006;38:497–503. doi: 10.1007/s11250-006-4390-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aryanti, Bintang M., Ermayanti T.M., Mariska I. Production of antileukemic agent in untransformed and transformed root cultures of Artemisia cina. Ann. Bogor. 2001;8:11–16. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mannan A., Ahmed I., Arshad W., Asim M.F., Qureshi R.A., Hussain I., Mirza B. Survey of artemisinin production by diverse Artemisia species in northern Pakistan. Malar. J. 2010;9:310. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-9-310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mannan A., Ahmed I., Arshad W., Hussain I., Mirza B. Effects of vegetative and flowering stages on the biosynthesis of artemisinin in Artemisia species. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2011;34:1657–1661. doi: 10.1007/s12272-011-1010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mannan A., Shaheen N., Arshad W., Qureshi R.A., Zia M., Mirza B. Hairy roots induction and artemisinin analysis in Artemisia dubia and Artemisia indica. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2008;7:3288–3292. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bayarmaa J., Zorzi G.D. Determination of artemisinin content in Artemisia annua L. Mong. J. Boil. Sci. 2011;9:47–51. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hsu E. The history of qing hao in the Chinese materia medica. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2006;100:505–508. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2005.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ranjbar M., Naghavi M.R., Alizadeh H., Soltanloo H. Expression of artemisinin biosynthesis genes in eight Artemisia species at three developmental stages. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2015;76:836–843. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2015.07.077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Salehi M., Karimzadeh G., Naghavi M.R., Badi H.N., Monfared S.R. Expression of artemisinin biosynthesis and trichome formation genes in five Artemisia species. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2018;112:130–140. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2017.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zia M., Abdul M., Chaudhary M.F. Effect of growth regulators and amino acids on artemisinin production in the callus of Artemisia absinthium. Pak. J. Bot. 2007;39:799–805. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Charles D.J., Simon J.E., Wood K.V., Heinstein P. Germplasm variation in artemisinin content of Artemisa annua using an alternative method of artemisinin analysis from crude plant extracts. J. Nat. Prod. 1990;53:157–160. doi: 10.1021/np50067a021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dayrit F.M. From Artemisia annua L. to Artemisinins: The Discovery and Development of Artemisinins and Antimalarial Agents. Academic Press; Cambridge, MA, USA: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Singh A., Vishwakarma R.A., Husain A. Evaluation of Artemisia annua strains for higher artemisinin production. Planta Med. 1988;54:475–477. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-962515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Woerdenbag H.J., Pras N., Chan N.G. Artemisinin, related sesquiterpenes, and essential oil in Artemisia annua during a vegetation period in Vietnam. Planta Med. 1994;60:272–275. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-959474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hamidi F., Karimzadeh G., Monfared S.R., Salehi M. Assessment of Iranian endemic Artemisia khorassanica: Karyological, genome size, and gene expressions involved in artemisinin production. Turk. J. Boil. 2018;42:322–333. doi: 10.3906/biy-1802-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pellicera J., Saslis-Lagoudakis C.H., Carrió E., Ernst M., Garnatje T., Grace O.M., Gras A., Mumbrú M., Vallès J., Vitales D., et al. A phylogenetic road map to antimalarial Artemisia Species. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018;225:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2018.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suresh J., Singh A., Vasavi A., Ihsanullah M., Mary S. Phytochemical and pharmacological properties of Artemisia pallens. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 2011;5:3090–3091. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Singh A., Sarin R. Artemisia scoparia: A new source of artemisinin. Bangladesh J. Pharmacol. 2010;5:17–20. doi: 10.3329/bjp.v5i1.4901. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu C.X. Discovery and development of artemisinin and related compounds. Chin. Herb. Med. 2017;9:101–114. doi: 10.1016/S1674-6384(17)60084-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kayani W.K., Kiani B.H., Dilshad E., Mirza B. Biotechnological approaches for artemisinin production in Artemisia. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018;34:54. doi: 10.1007/s11274-018-2432-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zeng Q.P., Qiu F., Yuan L. Production of artemisinin by genetically-modified microbes. Biotechnol. Lett. 2008;30:581–592. doi: 10.1007/s10529-007-9596-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arsenault P.R., Wobbe K.K., Weathers P.J. Recent advances in artemisinin production through heterologous expression. Curr. Med. Chem. 2008;15:2886. doi: 10.2174/092986708786242813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hommel M. The future of artemisinins: Natural, synthetic or recombinant? J. Boil. 2008;7:38. doi: 10.1186/jbiol101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Badshah S.L., Ullah A., Ahmad N., Almarhoon Z.M., Mabkhot Y. Increasing the strength and production of artemisinin and its derivatives. Molecules. 2018;23:100. doi: 10.3390/molecules23010100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Efferth T. Artemisinin–second career as anticancer drug? World J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2015;1:2–25. doi: 10.15806/j.issn.2311-8571.2015.0036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang Y., Xu G., Zhang S., Wang D., Prabha P.S., Zuo Z. Antitumor research on artemisinin and its bioactive derivatives. Nat. Prod. Bioprospect. 2018 doi: 10.1007/s13659-018-0162-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Efferth T. From ancient herb to modern drug: Artemisia annua and artemisinin for cancer therapy. Semin. Cancer Boil. 2017;46:65–83. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2017.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Naß J., Efferth T. The activity of Artemisia spp. and their constituents against Trypanosomiasis. Phytomedicine. 2018;47:184–191. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2018.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yuan D.S., Chen Y.P., Tan L.L., Huang S.Q., Li C.Q., Wang Q., Zeng Q.P. Artemisinin: A panacea eligible for unrestrictive use? Front. Pharmacol. 2017;8:737. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ferreira J.F.S., Gonzalez J.M. Analysis of underivatized artemisinin and related sesquiterpene lactones by high-performance liquid chromatography with ultraviolet detection. Phytochem. Anal. 2009;20:91–97. doi: 10.1002/pca.1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lapkin A.A., Walker A., Sullivan N., Khambay B., Mlambo B., Chemat S. Development of HPLC Analytical Protocol for Artemisinin Quantification in Plant Materials and Extracts. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2009;49:908–915. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2009.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Paniwnyk L., Briars R. Examining the extraction of artemisinin from Artemisia annua using ultrasound. In: Linde B.B.J., Pączkowski J., Ponikwicki N., editors. International Congress on Ultrasonics. American Institute of Physics; Gdańsk, Poland: 2011. pp. 581–585. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huter M.J., Schmidt A., Mestmäcker F., Sixt M., Strube J. Systematic and model-assisted process design for the extraction and purification of frtemisinin from Artemisia annua L.—Part iv: Crystallization. Processes. 2018;6:181. doi: 10.3390/pr6100181. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu C.Z., Zhou H.Y., Zhao Y. An effective method for fast determination of artemisinin in Artemisia annua L. by high performance liquid chromatography with evaporative light scattering detection. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2007;581:298–302. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2006.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Peng C.A., Ferreira J.F.S., Wood A.J. Direct analysis of artemisinin from Artemisia annua L. using high-performance liquid chromatography with evaporative light scattering detector, and gas chromatography with flame ionization detector. J. Chromatogr. A. 2006;1133:254–258. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2006.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Waffo A.F.T., Yesildag C., Caserta G., Katz S., Zebger I., Lensen M.C., Wollenberger U., Scheller F.W., Altintas Z. Fully electrochemical mip sensor for artemisinin. Sens. Actuators B. Chem. 2018;275:163–173. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2018.08.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Czechowski T., Larson T.R., Catania T.M., Harvey D., Wei C., Essome M., Brown G.D., Graham I.A. Detailed phytochemical analysis of high- and low artemisinin-producing chemotypes of Artemisia annua. Front. Plant Sci. 2018;9:641. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.00641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liersch R., Soicke H., Stehr C., Tüllner H.U. Formation of artemisinin in Artemisia annua during one vegetation period. Planta Med. 1986;52:387–390. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-969193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Patil A.R., Arora J.S., Gaikar V.G. Purification of artemisinin from Artemisia annua extract by sorption on different ligand loaded polymeric adsorbents designed by molecular simulation. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2012;47:1156–1166. doi: 10.1080/01496395.2011.644876. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chemat-Djenni Z., Sakhri A. MATEC. EDP Sciences; Les Ulis, France: 2013. Purification of artemisinin excerpt from Artemisia annua L. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.