Abstract

Older adults often experience decline in functional status during the transition from hospital to home. In order to determine the effectiveness of interventions to prevent functional decline, researchers must have instruments that are reliable and valid for use with older adults. The purpose of this integrative review is to: (1) summarize the research uses and methods of administering functional status instruments when investigating older adults transitioning from hospital to home, (2) examine the development and existing psychometric testing of the instruments, and (3) discuss gaps and implications for future research. The authors conducted an integrative review of forty research studies that assessed functional status in older adults transitioning from hospital to home. This review reveals important gaps in the functional status instruments’ psychometric testing, including limited testing to support their validity and reliability when administered by self-report and limited evidence supporting their ability to detect change over time.

Keywords: functional status, instruments, older adults, psychometrics, transition

Adults aged 65 and older are discharged from the hospital more often than any other age group, accounting for 40% of hospital discharges in the US in 2010 (‘National Hospital Discharge Survey,’ 2012). Hospitalizations are consequential for older adults, as about 50% will experience functional decline. For the purpose of this review, functional decline refers to a decline in activities of daily living (ADLs) or instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) (Buurman et al., 2011, Millán-Calenti et al., 2010, Wu et al., 2006, Zisberg et al., 2015). In addition, up to 50% of older adults do not recover their pre-hospitalization functional status during their first 30–90 days back home (Buurman et al., 2011, Huang et al., 2013, Wu et al., 2006, Zisberg et al., 2015). Older adults experiencing functional decline after discharge to home are particularly vulnerable because they may have less physical support than those discharged to rehabilitation centers, assisted living, or long-term care. Additionally, transitional care models developed to support older adults transitioning from hospital to home have not included functional status as a primary study variable (Kind et al., 20012, Naylor et al., 1999, Naylor et al., 2004, Naylor et al., 2014). Therefore, the transition between hospital and home is a critical interval during which older adults experience high rates of functional decline.

To determine the effectiveness of interventions to prevent functional decline, researchers must have instruments that are reliable and valid for use with older adults (Applegate et al., 1990). Reliability refers to repeatability or consistency of scores on an instrument (Trochim and Donnelly, 2001). Validity indicates that a tool is measuring what it is intended to measure (Trochim and Donnelly, 2001). Currently, there is considerable variability in how functional status is measured in older adults (Buurman et al., 2011). The instruments most commonly used to measure ADLs or IADLs were developed several decades ago to assess function by direct observation of patient performance in those undergoing rehabilitation for musculoskeletal conditions (Kane and Kane, 2000, Katz et al., 1963, Mahoney and Barthel, 1965). However, these instruments have subsequently been applied to many different groups of older adults (e.g., community-based, hospital-based, and across many diagnoses). Additionally, functional status instruments are commonly administered by self-report, rather than by observation of performance. Therefore, it is important to understand whether instruments used to measure functional status have had sufficient psychometric testing to validate their utility as self-report measures in various groups of older adults.

Given the high rates of functional decline among older adults transitioning from hospital to home, it is important to have instruments that are reliable and valid for measurements taken at once older adults return home, i.e., a community-dwelling population. Additionally, older adults transitioning from hospital to home are unique in that many remain in a stage of acute illness and are in a transitional phase. Hence, instruments must be able to track changes in function throughout that transitional phase, and evaluators should be able to compare repeated measures over various time points for interventions targeting this transition from hospital to home. Therefore, an instrument’s test-retest reliability, i.e., consistency from one time to another, and sensitivity to change over time must be established to study such a population. Without proper testing of the instrument’s validity, reliability, and sensitively to change, i.e. psychometric testing, it is unclear whether the instruments are consistently detecting actual changes in function (Applegate et al., 1990). Thus, the purpose of this integrative review is to: (1) summarize the research uses and methods of administering functional status instruments, i.e., instruments measuring ADLs or IADLs, when investigating older adults transitioning from hospital to home, (2) examine the development and existing psychometric testing of the instruments, and (3) discuss gaps and implications for future research.

Methods

Search Strategy

The authors conducted an integrative review from August 2016 through July 2017 in CINAHL, PUBMED, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science for peer-reviewed English original research studies that assessed functional status in older adults transitioning from hospital to home. The following search terms were used in combination to identify articles: (1) functional status OR functional decline OR activities of daily living OR functional loss OR functional recovery OR functional independence OR functional outcomes, (2) hospitalized OR hospitalization OR hospital, (3) discharge OR transition, and (4) older adults. Search terms used to narrow results included: NOT stroke, NOT fracture, and NOT dementia. Additional references were sought by reviewing bibliographies of selected articles. All publication years were included through July 2017 to obtain a comprehensive understanding of how instruments have been used to measure functional status, both recently and historically.

Inclusion Criteria

Articles were included if: (1) functional status, i.e., an individual’s participation in ADLs IADLs, was included as one of the primary study variables, (2) a standardized instrument was used to measure functional status, and (3) older adults’ functional status was measured during the transition from hospital inpatient stay to home. To qualify as the transition from hospital inpatient stay to home, authors must have measured functional status at least one time during the first 90 days after hospital discharge.

Articles were excluded from the review if they assessed functional status only for patients with a specific condition or disease. Examples of such articles that were deemed as not being applicable to the general population include those focusing on patients suffering from stroke, Rheumatoid Arthritis, Parkinson’s disease, or Dementia. In these cases, condition or disease-specific functional status instruments were unique and the results could not be applied to the larger population of older adults transitioning from hospital to home. Articles that did not focus on adults aged 65 and older were also excluded from this review.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Data were extracted from the retrieved articles related to purpose of the research study, study design, sample, and instrument used to measure functional status. Each functional status instrument identified in this review was examined for evidence related to development and psychometric testing.

Risk of Bias

The ROBIS tool was used to identify concerns in the review process and judge risk of bias in reviews (Whiting et al., 2016). Concerns related to the review process are categorized into: study eligibility criteria, identification and selection of studies, data collection and study appraisal, and synthesis and findings (Whiting et al., 2016). The objectives of the review and eligibility criteria were defined by authors prior to review. Therefore, concern regarding specification of study eligibility criteria is low (Whiting et al., 2016). All three authors (DL, LB, and BK) were involved in study identification and selection. Several databases, a variety of search terms, and additional methods (including bibliography review) were used to identify articles for potential inclusion. Therefore, concern regarding identification and selection of studies is low (Whiting et al., 2016). All study characteristics that were pre-determined to be relevant for the review were collected for use in this synthesis. Authors attempted to provide level of detail regarding study characteristics in the results for readers to be able to interpret the results on their own. Risk of bias was assessed formally. Therefore, concerns regarding data collection and study appraisal are low (Whiting et al., 2016). Last, the synthesis included all studies that were determined eligible by authors (DL, LB, and BK) using pre-determined criteria. The instruments used to measure functional status were also reviewed using pre-determined methods. The pre-determined plan for synthesis of results was able to adequately achieve the aims of this review. Therefore, the concerns regarding synthesis and findings are low (Whiting et al., 2016). Given that concerns in conducting a review, outlined above, were addressed and selected publications were relevant to the authors’ research questions, the risk of bias in this review is considered low (Whiting et al., 2016).

Results

Search Results

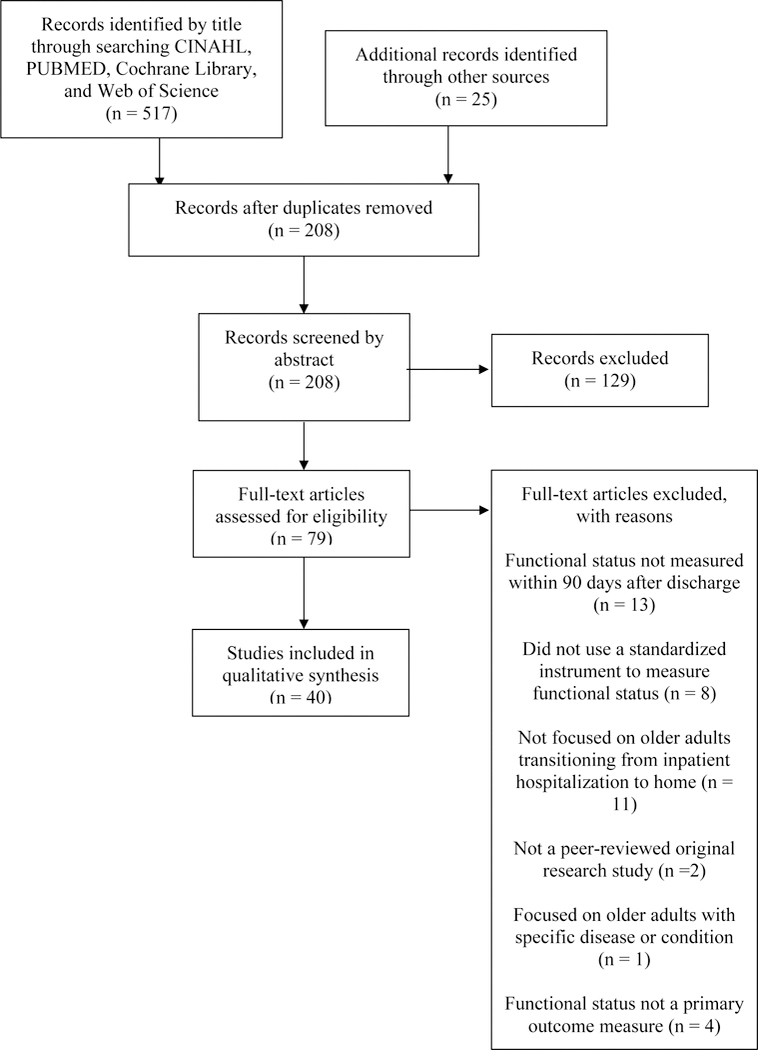

Five hundred seventeen publications were identified by title through the database searches. Twenty-five additional publications were identified through bibliography review. Two hundred eight publications remained after duplicate records were removed. Each of the 208 publications was screened by abstract (by DL, LB, and BK) resulting in exclusion of 129 records not meeting inclusion criteria. The remaining 79 publications were reviewed in full for eligibility. Forty publications were determined to be eligible and included in this review. See Figure 1 for more specific information related to reasons for exclusion from this review (Moher et al., 2009).

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram of Search Strategy and Study Selection

Instruments used to Measure Functional Status

From this review, the instruments used to measure functional status in older adults transitioning from hospital to home include: the Katz ADL, the Barthel Index, the Lawton and Brody Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL), and the ADL Summary Scale.

Katz ADL

The Katz ADL was the most common instrument used to measure functional status in older adults transitioning from hospital to home (see Table 1). This instrument tracks progressive loss of abilities seen in hospitalized patients (Katz et al., 1959), and was developed based on observations of hospitalized patients with hip fracture. It was found useful for deciding treatment and progress of ill individuals and has been used to assess other chronically ill populations age 40 and older (Katz et al., 1963). The instrument includes six items: bathing, dressing, going to toilet, transferring, continence, and feeding. Scoring of items is binary with 1 point given for independence and none given if the individual is dependent on supervision or assistance.

Table 1.

Use of Functional Status Instruments in Older Adults Transitioning from Hospital to Home

| Instrument | Examine relationships with other factors |

Create predictive index/model |

Track functional decline |

Evaluate intervention |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Katz ADL | 1–4 | 5–8 | 9 | |

| Modified Katz-1 | 10–17 | 18–19 | 20 | |

| Modified Katz-2 | 21 | |||

| Other modified Katz | 22 | 23–24 | 25–27 | 28–29 |

| Barthel Index | 30, 31 | 32–33 | 34–35 | |

| Modified Barthel-Shah | 36 | 37 | 38 | 39 |

| Modified Barthel-Granger | 40 | |||

| Lawton IADL | 36 | 9 | ||

| Modified Lawton | 12, 14–17 | 26 | 20 | |

| ADL Summary Scale | 22 |

Note: 1 = Arora et al., 2009;

2 = Bootsma et al., 2013;

5 = Buurman et al., 2012;

10 = Corsonello et al., 2012;

11 = Corsonello et al., 2014;

12 = Covinsky et al., 1997;

13 = Li et al., 2005;

14 = Mahoney et al., 1999;

15 = Pierluissi et al., 2012;

16 = Sands et al., 2005;

17 = Sands et al., 2003;

18 = Boyd et al., 2008;

19 = Chodos et al., 2015;

20 = Courtney et al., 2012;

21 = Huang et al., 2013;

22 = Volpato et al., 2011;

23 = Cornette et al., 2006;

24 = Sager et al., 1996b;

25 = Hansen et al., 1999;

26 = Sager et al., 1996a;

27 = Wu et al., 2006;

28 = Brown et al., 2016;

29 = Jeangsawang et al., 2012;

31 = Pasina et al., 2013;

32 = Bordne et al., 2015;

33 = Chen et al., 2008;

34 = Boltz et al., 2014;

35 = McMurdo et al., 2009;

36 = Zisberg et al., 2011;

37 = Zisberg et al., 2015;

38 = Zaslavsky et al., 2015;

39 = Avlund et al., 2002;

40 = Michael et al., 2005.

In publications focused on older adults transitioning from hospital to home, modified versions of Katz ADL were used more than the original version. The modified versions of the Katz ADL include various items from the original instrument, as well as additional items such as ambulation or walking. For instance, the modified Katz-1 includes five items from the original Katz ADL: dressing, bathing, transferring, eating, and toileting and the modified Katz-2 includes the original six items from the Katz ADL and an additional item related to walking. The Katz ADL and modified versions have been largely administered by self-report and telephone-report to older adults transitioning from hospital to home after discharge (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Methods of Administering Functional Status Instruments to Older Adults Transitioning from Hospital to Home

| Instrument | Self-report | Telephone-report after hospital discharge |

Caregiver-report | Nurse observation/ report |

Study staff observation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Katz ADL | 1–9 | 1–9 | |||

| Modified Katz-1 | 10–20 | 10, 14, 16–18, 20 | 11 | ||

| Modified Katz-2 | 21 | 21 | |||

| Other modified Katz | 22, 24–28 | 24–28 | 23, 29 | ||

| Barthel Index | 32–33, 35 | 32 | 30, 34 | 30, 31 | |

| Modified Barthel-Shah | 36–39 | 36–38 | |||

| Modified Barthel-Granger | 40 | 40 | |||

| Lawton IADL | 9, 36 | 9, 36 | |||

| Modified Lawton | 12, 14–17, 20, 26 | 14, 16–17, 20, 26 | |||

| ADL Summary Scale | 22 |

Note: 1 = Arora et al., 2009;

2 = Bootsma et al., 2013;

5 = Buurman et al., 2012;

10 = Corsonello et al., 2012;

11 = Corsonello et al., 2014;

12 = Covinsky et al., 1997;

13 = Li et al., 2005;

14 = Mahoney et al., 1999;

15 = Pierluissi et al., 2012;

16 = Sands et al., 2005;

17 = Sands et al., 2003;

18 = Boyd et al., 2008;

19 = Chodos et al., 2015;

20 = Courtney et al., 2012;

21 = Huang et al., 2013;

22 = Volpato et al., 2011;

23 = Cornette et al., 2006;

24 = Sager et al., 1996b;

25 = Hansen et al., 1999;

26 = Sager et al., 1996a;

27 = Wu et al., 2006;

28 = Brown et al., 2016;

29 = Jeangsawang et al., 2012;

31 = Pasina et al., 2013;

32 = Bordne et al., 2015;

33 = Chen et al., 2008;

34 = Boltz et al., 2014;

35 = McMurdo et al., 2009;

36 = Zisberg et al., 2011;

37 = Zisberg et al., 2015;

38 = Zaslavsky et al., 2015;

39 = Avlund et al., 2002;

40 = Michael et al., 2005.

Despite being most commonly administered by self-report, the only validity testing found for the original Katz ADL was for ratings done by nurse observation (see Table 3) (Brorsson and Asberg, 1984). On the other hand, the modified Katz-1 has had testing supporting its validity, including convergent validity with the FIM (r = 0.78) by self-report in hospitalized older adults (Mahoney et al., 1999), predictive validity of retrospective self-report by hospitalized older adults (Covinsky et al., 2000), and construct validity, i.e., that the instrument contains the dimensions necessary to describe the concept, of telephone-report by community-dwelling adults (coefficient of reproducibility = .92; coefficient of scalability = .68) (Ciesla et al., 1993). However, there is evidence of poor agreement between self-report and observation-based assessments for the Katz ADL. For the Katz ADL, patients report significantly higher scores than did their nurses (Rubenstein et al., 1984). The modified Katz-1 has a low observed rate of agreement between patient-report and occupational therapist assessment. For example, activities such as bathing and dressing only have a 0.63 and 0.64 rate of agreement, respectively (slightly greater than the hypothetical probability of chance agreement at 0.50) (Sager et al., 1992). No evidence was found related to the validity of the remaining seven modified versions of the Katz ADL. Despite evidence of validity testing for the Katz ADL and modified Katz-1, no evidence was found concerning the test-retest reliability or ability to detect change over time for the Katz ADL or any of the modified versions of the Katz ADL used in studies on older adults transitioning from hospital to home.

Table 3.

Psychometric Testing of Instruments used to Measure Functional Status in Older Adults Transitioning from Hospital to Home

| Instrument | Reliability | Validity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inter-rater (κ or r) |

Test-retest (ICC or r) |

Internal Consistency (α) |

Construct (CR or CS) |

Predictive | Convergent (r) |

Divergent | |

| Katz ADL | 0.721 | 0.74 – 0.882 | living at home, mortality2 | ||||

| Modified Katz-1 | 0.27 – 0.636 | 0.873 | 0.68 – 0.923 | survival, independence after discharge5 | 0.784 | ||

| Modified Katz-2 | 0.917 | ||||||

| Barthel index | 0.23 – 0.958,9,10,11,14,15, 16,17 | 0.9013 | .64–112,13 | ||||

| Modified Barthel-Shah | 0.10 – 0.9514,19 | 0.9018 | |||||

| Modified Barthel-Granger | discharge to home, length of stay20 | ||||||

| Lawton IADL | 0.85 – 0.9921,23 | 0.9323 | 0.837 | 0.93 – 0.9621 | mental status, psychosocial function, living situation, # of medications, outpatient visits 22 | 0.36 – 0.7721 | |

| ADL Summary Scale | 0.82 – 0.9324 | 0.72 – 0.9524,25 | Related to actual functional changes and other health events24 | hospitalization, nursing home admission, death24 | |||

Note: κ = Kappa statistic, r = correlation, ICC = Intra-class correlation, α = Cronbach’s alpha, CR = coefficient of reproducibility, CS = coefficient of scalability

Barthel Index

The Barthel Index was the second most common instrument used to measure functional status in older adults transitioning from hospital to home (see Table 1). The Barthel Index was developed as a simple index of independence to score the self-care ability of a patient (Mahoney and Barthel, 1965). The instrument was designed for rehabilitation staff to rate their observations of the patient’s ability and progress over time (Mahoney and Barthel, 1965). The target population for the instrument was rehabilitation patients in chronic disease hospitals suffering from a neuromuscular or musculoskeletal disorder (Mahoney and Barthel, 1965). The Barthel Index includes 10 items: feeding, moving between wheelchair and bed, personal toilet, getting on and off toilet, bathing self, walking on level surface, ascending and descending stairs, dressing, controlling bowels, and controlling bladder (Mahoney and Barthel, 1965). Scoring ranges from 0 (dependent) or 1 (independent) on basic care items such as bathing and grooming to 0 (dependent), 1 (major help), 2 (minor help), or 3 (independent) on more complex items such as walking and transferring (Mahoney and Barthel, 1965).

In publications focusing on older adults transitioning from hospital to home, modified versions of the Barthel Index were used approximately as often as the original version. The Barthel Index has been primarily administered by self-report and telephone-report after discharge in older adults transitioning from hospital to home (see Table 2). The modified versions of the Barthel Index, the modified Barthel-Shah and modified Barthel-Granger, were exclusively administered by self-report and telephone-report after discharge. The modified Barthel-Shah includes more scoring categories per item (five categories: unable to perform, attempts task but unsafe, moderate help required, minimal help required, fully independent) to increase sensitivity of the instrument for stroke patients in inpatient rehabilitation (Shah et al., 1989). The modified Barthel-Granger has revised scores per item category (from 0, 1, 2, or 3 points to 5, 10, or 15 points) and revised scoring criteria, i.e., more specific descriptions of what would qualify as independent versus needing help or being dependent, to track progress of patients in a rehabilitation hospital (Granger et al., 1979).

There is little evidence supporting the validity of the Barthel Index and the two modified versions (see Table 3). For instance, only two studies provide evidence of convergent validity, i.e., demonstrate that the instrument yields similar results to another measure of the same concept, of the Barthel Index, and these studies were conducted with populations vastly different than older adults transitioning from hospital to home, e.g., stroke patients (Gosman-Hedström and Svensson, 2000), and with observation-based assessment (Minosso et al., 2010). The only validity testing for the modified versions was predictive validity for observations of rehabilitation patients (Granger et al., 1979). Despite testing of the inter-rater reliability of the Barthel Index and modified Barthel-Shah, results were mixed and the reliability between self-report and observation methods was low (κ = 0.10 – 0.39) (Sinoff and Ore, 1997). Additionally, no evidence was found related to the ability to detect change over time or test-retest reliability for the Barthel Index or the two modified versions.

Lawton and Brody IADL

The Lawton and Brody IADL has also been used to measure functional status in older adults transitioning from hospital to home (see Table 1). The Lawton and Brody IADL was developed as an objective measure of more complex functioning than other ADL instruments for older adults (Lawton and Brody, 1969). Despite an attempt to include a variety of older adults in the developmental study, the sample primarily included community-based or community-destined older adults. The original Lawton and Brody IADL includes an eight-point scale for women: ability to use telephone, shopping, food preparation, housekeeping, laundry, mode of transportation, responsibility for medications, ability to handle finances (Lawton and Brody, 1969). A five-point scale was originally developed for men: ability to use telephone, shopping, mode of transportation, responsibility for medications, ability to handle finances (Lawton and Brody, 1969). Each item is scored as 1 point (independent) or 0 points (dependent) (Lawton and Brody, 1969). Originally, it was thought that as men participate less in activities pertaining to food preparation, housekeeping, and laundry, these activities should not be included in an instrument administered to men (Lawton and Brody, 1969). However, the same instrument has since been administered to men and women, and a seven-point modified version (omitting laundry) is administered most frequently. Both the original Lawton and Brody IADL and the modified version have been administered to older adults exclusively by self-report and the majority by telephone-report during the transition from hospital to home after discharge (see Table 2).

The development study for the Lawton and Brody IADL documents acceptable convergent validity (r = 0.36 – 0.77), good construct validity (coefficient of reproducibility = 0.93 – 0.96), and good inter-rater reliability (r = 0.85) in community-dwelling and community-destined older adults (see Table 3) (Lawton and Brody, 1969). However, the scale was developed for observation-based assessments and each of the publications in this review administered it by self-report. Additionally, the instrument has not been administered as designed—with unique scales for men versus women (Lawton and Brody, 1969). There is evidence to support the test-retest reliability (r = 0.93) and inter-rater reliability (r = 0.99) of the self-report Lawton and Brody IADL in hospitalized older adults (Edwards, 1990). However, the only test of validity found since its development was for predictive validity across various scoring methods (Vittengl et al., 2006). Additionally, patient self-report scores on the Lawton and Brody IADL have been found to indicate significantly better functional status than nurse-derived or significant-other reported scores (Rubenstein et al., 1984). No evidence could be found to support the ability of the Lawton and Brody IADL to detect change over time. No evidence could be found related to the validity, test-retest reliability, or ability to detect change over time of the modified version of the Lawton and Brody IADL.

ADL Summary Scale

The ADL Summary Scale was used to measure functional status in a single study with older adults transitioning from hospital to home (see Table 1). The ADL summary scale was developed from five Katz ADLs (bathing, using the toilet, transferring from bed to chair, dressing, and eating) to assess a gradient of difficulty in ADLs (Ostir et al., 2001). The ADL Summary Scale was developed as a self-report measure, and the authors developed a scoring system for the instrument in a population of older disabled women living in the community (Ostir et al., 2001). The score per item ranges from 0 (able to do without difficulty), 1 (little difficulty), 2 (some difficulty), 3 (a lot of difficulty), to 4 (unable to do) (Ostir et al., 2001). The ADL Summary Scale was administered by self-report in the study focusing on older adults transitioning from hospital to home (see Table 2).

The development study for the ADL Summary Scale provides evidence of predictive validity, internal consistency (α = 0.72) test-retest reliability (ICC = 0.82 – 0.93), and ability to detect changes over time (see Table 3) (Ostir et al., 2001). However, the sample for the development study was older disabled women living in the community. There is insufficient evidence to support the instrument’s validity and reliability in men or older adults who are not disabled. When administered to a more general group of older adults, only evidence of internal consistency was found for the ADL Summary Scale (α = 0.95) (Volpato et al., 2011)—not validity, test-retest reliability, nor ability to detect changes over time.

Discussion

This integrative review reveals that the instruments most commonly used to measure functional status, i.e., ADLs and IADLs, in older adults transitioning from hospital to home are not administered as originally designed. Each of the instruments, with the exception of the ADL Summary Scale, was developed for observation (of performance)-based assessments. However, the large majority of the studies measuring functional status as an outcome in older adults transitioning from hospital to home rely on self-report. Further, many of the studies relied on self-report by telephone to follow patients after hospital discharge. However, there is limited evidence regarding the validity of these instruments when administered by self-report. Only one study demonstrated the convergent validity of the self-report Barthel Index with patients recovering from a stroke (Gosman-Hedström and Svensson, 2000). Similarly, no validity testing was found for the Lawton and Brody IADL and Katz ADL by self-report. Rubenstein et al. (1984) provided evidence that patients report better functional status than nurse observed scores or proxy report scores on the Katz ADL and Lawton and Brody IADL. Given the discrepancies between observation and self-report of functional status, it is crucial that functional status instruments have evidence supporting their validity when administered by self-report. Currently, the majority of the evidence supporting the validity of the instruments is only for observation-based assessments. If there is no evidence of validity for the instruments being used, then it is unclear whether these instruments are measuring the concepts they are intended to (Applegate et al., 1990).

Testing of reliability of instruments used to measure functional status is also important, specifically test-retest reliability (Applegate et al., 1990). There have been more tests of reliability than validity in the instruments used to measure functional status. However, few studies have been conducted on test-retest reliability of functional status instruments used in this group. Test-retest reliability assumes there is no substantial change in the construct being measured between two time points and speaks to the stability of the instrument (Polit and Beck, 2004, Trochim and Donnelly, 2001). If the instrument is stable, then changes measured with the instrument should reflect actual alterations in older adults’ functional status. No psychometric testing of test-retest reliability was found for the two most commonly used instruments in this group, the Katz ADL and Barthel Index. The ADL Summary Scale and Lawton and Brody IADL have some evidence of test-retest reliability; therefore, documenting validity of the instruments by self-report among older adults transitioning from hospital to home is needed.

In addition to validity and reliability, instruments used to measure functional status in older adults transitioning from hospital to home should be sensitive to actual changes in function over time. Otherwise, results related to interventions aimed at improving function or results tracking change in functional status may not be detecting actual changes. For instance, only two of the seven intervention studies included in this review detected significant differences in functional status during follow-up after discharge. Based on this review of the instruments, it is unclear whether any results were due to the intervention or study methodological differences. The ADL Summary Scale is the only instrument used in this review for which evidence was found supporting its sensitivity to change. However, the supporting evidence is only in older disabled women, not men or non-disabled groups (Ostir et al., 2001). Given the lack of testing related to sensitivity to change over time, it is unclear whether the studies are detecting actual changes in function that are occurring during the transition from hospital to home (Applegate et al., 1990). Therefore, the results of these studies should be interpreted carefully and interventions developed by using these instruments may not yield practical benefits when implemented (Deyo and Inui, 1984, Deyo and Patrick, 1989).

This review revealed the use of several modified versions of functional status instruments used in older adults transitioning from hospital to home. When an instrument is modified from the original instrument, additional psychometric testing of the modified instrument is essential to ensure its validity and reliability. However, for most of the modified versions, little or no psychometric testing could be found. The absence of psychometric testing for these modified versions indicates that there is no evidence that these instruments are measuring as intended or that there will be any consistency in the derived scores (Polit and Beck, 2004). Only the modified Katz-1 (five items: dressing, bathing, transferring, eating, and toileting) has had significant psychometric testing among the modified instruments (Ciesla et al., 1993, Covinsky et al., 2000, Mahoney et al., 1999, Sager et al., 1992). Despite encouraging validity and reliability testing for this modified version of the Katz ADL, it still lacks evidence related to test-retest reliability and ability to detect change over time. Additionally, the use of various instruments and several modified versions of those instruments limits our ability to synthesize results and derive implications for translating the research being reviewed into practice.

The review needs to be considered in light of a few limitations. As researchers use many different terms to refer to functional status, we found it necessary to use a large variety of search terms to seek out publications addressing functional status in older adults transitioning from hospital to home. Despite our inclusion of a large variety of search terms, some publications may not have been identified. We addressed this concern with our directed screening of the bibliographies from several recent high-profile publications in this field. Additionally, this review focused on research with older adults transitioning from hospital to home. A review of the literature on transitioning care of older adults from hospital to subacute or long-term care settings may produce different results. Further, this review focused on the use of functional status instruments in research on transitioning care and did not address clinical implications of the instruments. Implications for clinical practice should be pursued in future reviews. Finally, the ROBIS tool was used to determine risk of bias in the review. Our results determined the overall risk of bias as low (Whiting et al., 2016).

This integrative review has several implications for future research conducted with this high-risk population. The instruments used to measure functional status in older adults transitioning from hospital to home were developed in the 1960s (Kane and Kane, 2000, Katz et al., 1963, Lawton and Brody, 1969, Mahoney and Barthel, 1965) and have been applied to a variety of populations of older adults without sufficient psychometric testing to support their utility in various groups. Further, the instruments most commonly used to measure functional status were originally designed to assess function by observation and primarily in rehabilitation patients. This review also reveals that the majority of research on older adults transitioning from hospital to home use self-report rather than observation. Review of psychometric testing yielded limited evidence supporting the functional status instruments’ reliability and validity by self-report. It may be important to conduct additional psychometric testing of self-report versions of the instruments to determine the trustworthiness of results and future utility of the instruments. There was also little evidence supporting the ability of these functional status instruments to detect actual changes in function over time, which is important during transitional periods when function may continue to decline (Applegate et al., 1990). Given the limitations of the instruments used to measure functional status in older adults transitioning from hospital to home, it is unclear whether results represent actual changes in functional status occurring during the transition (Applegate et al., 1990, Deyo and Inui, 1984, Deyo and Patrick, 1989). The use of many different instruments and modified versions also limits our ability to synthesize results and make implications for practice. The use of a framework to unify future research in this area or development of an instrument specifically designed for older adults transitioning from hospital to home would be important steps to advance research and improve outcomes for this group.

Acknowledgements:

The project described was supported by the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program, through the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), grant UL1TR000427. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.”

References

- 2012. National Hospital Discharge Survey. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Healthcare Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Applegate WB, Blass JP, Williams TF, 1990. Instruments for the functional assessment of older patients. New England Journal of Medicine 322 (17), 1207–1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arora VM, Plein C, Chen S, Siddique J, Sachs GA, Meltzer DO, 2009. Relationship between quality of care and functional decline in hospitalized vulnerable elders. Medical Care 47 (8), 895–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avlund K, Jepsen E, Vass M, Lundemark H, 2002. Effects of comprehensive follow-up home visits after hospitalization on functional ability and readmissions among old patients. A randomized controlled study. Scandinavian journal of occupational therapy 9 (1), 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Baker LA, Cahalin LP, Gerst K, Burr JA, 2005. Productive activities and subjective well-being among older adults: The influence of number of activities and time commitment. Social Indicators Research, 73(3), 431–458. [Google Scholar]

- Boltz M, Resnick B, Chippendale T, Galvin J, 2014. Testing a Family‐Centered Intervention to Promote Functional and Cognitive Recovery in Hospitalized Older Adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 62 (12), 2398–2407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bootsma AJ, Buurman BM, Geerlings SE, de Rooij SE, 2013. Urinary incontinence and indwelling urinary catheters in acutely admitted elderly patients: relationship with mortality, institutionalization, and functional decline. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 14 (2), 147. e147–147. e112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordne S, Schulz R-J, Zank S, 2015. Effects of inpatient geriatric interventions in a German geriatric hospital. Zeitschrift für Gerontologie und Geriatrie 48 (4), 370–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd CM, Landefeld CS, Counsell SR, Palmer RM, Fortinsky RH, Kresevic D, Burant C, Covinsky KE, 2008. Recovery of activities of daily living in older adults after hospitalization for acute medical illness. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 56 (12), 2171–2179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brorsson B, Asberg KH, 1984. Katz index of independence in ADL. Reliability and validity in short-term care. Scand J Rehabil Med 16 (3), 125–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown CJ, Foley KT, Lowman JD, MacLennan PA, Razjouyan J, Najafi B, Locher J, Allman RM, 2016. Comparison of Posthospitalization Function and Community Mobility in Hospital Mobility Program and Usual Care Patients: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA internal medicine. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buurman BM, Hoogerduijn JG, de Haan RJ, Abu-Hanna A, Lagaay AM, Verhaar HJ, Schuurmans MJ, Levi M, de Rooij SE, 2011. Geriatric conditions in acutely hospitalized older patients: prevalence and one-year survival and functional decline. PLoS One 6 (11), e26951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buurman BM, Hoogerduijn JG, Van Gemert EA, De Haan RJ, Schuurmans MJ, de Rooij SE, 2012. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of hospitalized older patients with distinct risk profiles for functional decline: a prospective cohort study. PloS one 7 (1), e29621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buurman BM, van Munster BC, Korevaar JC, de Haan RJ, de Rooij SE, 2011. Variability in measuring (instrumental) activities of daily living functioning and functional decline in hospitalized older medical patients: a systematic review. Journal of clinical epidemiology 64 (6), 619–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CC, Wang C, Huang GH, 2008. Functional trajectory 6 months posthospitalization: a cohort study of older hospitalized patients in Taiwan. In, Nurs Res. United States, pp. 93–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y, Park S, Cho KH, Chun SY, Park EC,2016. A change in social activity affect cognitive function in middle‐aged and older Koreans: analysis of a Korean longitudinal study on aging (2006–2012). International journal of geriatric psychiatry, 31(8), 912–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chodos AH, Kushel MB, Greysen SR, Guzman D, Kessell ER, Sarkar U, Goldman LE, Critchfield JM, Pierluissi E, 2015. Hospitalization-Associated Disability in Adults Admitted to a Safety-Net Hospital. J Gen Intern Med 30 (12), 1765–1772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciesla JR, Shi L, Stoskopf CH, Samuels ME, 1993. Reliability of Katz’s Activities of Daily Living Scale when used in telephone interviews. Evaluation & the health professions 16 (2), 190–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collin C, Wade DT, Davies S, Horne V, 1988. The Barthel ADL Index: a reliability study. Int Disabil Stud 10 (2), 61–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornette P, Swine C, Malhomme B, Gillet JB, Meert P, D’Hoore W, 2006. Early evaluation of the risk of functional decline following hospitalization of older patients: development of a predictive tool. In, Eur J Public Health. England, pp. 203–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corsonello A, Lattanzio F, Pedone C, Garasto S, Laino I, Bustacchini S, Pranno L, Mazzei B, Passarino G, Incalzi On Behalf Of The Pharmacosurveillance In The Elderly Care Pvc Study Investigators, R.A., 2012. Prognostic significance of the short physical performance battery in older patients discharged from acute care hospitals. Rejuvenation Research 15 (1), 41–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corsonello A, Maggio M, Fusco S, Adamo B, Amantea D, Pedone C, Garasto S, Ceda GP, Corica F, Lattanzio F, 2014. Proton pump inhibitors and functional decline in older adults discharged from acute care hospitals. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 62 (6), 1110–1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtney MD, Edwards HE, Chang AM, Parker AW, Finlayson K, Bradbury C, Nielsen Z, 2012. Improved functional ability and independence in activities of daily living for older adults at high risk of hospital readmission: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice 18 (1), 128–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covinsky KE, Fortinsky RH, Palmer RM, Kresevic DM, Landefeld CS, 1997. Relation between symptoms of depression and health status outcomes in acutely ill hospitalized older persons. Ann Intern Med 126 (6), 417–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covinsky KE, Palmer RM, Counsell SR, Pine ZM, Walter LC, Chren MM, 2000. Functional status before hospitalization in acutely ill older adults: validity and clinical importance of retrospective reports. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 48 (2), 164–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Saint-Hubert M, Jamart J, Morrhaye G, Martens HJ, Geenen V, Vo TKD, Toussaint O, Swine C, 2011. Serum IL-6 and IGF-1 improve clinical prediction of functional decline after hospitalization in older patients. Aging clinical and experimental research 23 (2), 106–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Della Pietra GL, Savio K, Oddone E, Reggiani M, Monaco F, Leone MA, 2011. Validity and reliability of the Barthel index administered by telephone. Stroke 42 (7), 2077–2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deschodt M, Wellens NIH, Braes T, De Vuyst A, Boonen S, Flamaing J, Moons P, Milisen K, 2011. Prediction of functional decline in older hospitalized patients: a comparative multicenter study of three screening tools. Aging Clinical & Experimental Research 23 (5/6), 421–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deyo RA, Inui TS, 1984. Toward clinical applications of health status measures: sensitivity of scales to clinically important changes. Health services research 19 (3), 275. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deyo RA, Patrick DL, 1989. Barriers to the use of health status measures in clinical investigation, patient care, and policy research. Medical care, S254–S268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards MM, 1990. The reliability and validity of self-report activities of daily living scales. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy 57 (5), 273–278. [Google Scholar]

- Fricke J, Unsworth CA, 1997. Inter-rater reliability of the original and the modified Barthel Index, and a comparison with the Functional Independence Measure. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal 44, 22–29. [Google Scholar]

- Gariballa S, Alessa A, 2017. Impact of poor muscle strength on clinical and service outcomes of older people during both acute illness and after recovery. BMC geriatrics 17 (1), 123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosman-Hedström G, Svensson E, 2000. Parallel reliability of the functional independence measure and the Barthel ADL index. Disability and rehabilitation 22 (16), 702–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granger CV, Dewis LS, Peters NC, Sherwood CC, Barrett JE, 1979. Stroke rehabilitation: analysis of repeated Barthel index measures. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 60 (1), 14–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen K, Mahoney J, Palta M, 1999. Risk factors for lack of recovery of ADL independence after hospital discharge. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 47 (3), 360–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartigan I, O’Mahony D, 2011. The Barthel Index: comparing inter-rater reliability between Nurses and Doctors in an older adult rehabilitation unit. Applied nursing research 24 (1), e1–e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoogerduijn JG, Buurman BM, Korevaar JC, Grobbee DE, de Rooij SE, Schuurmans MJ, 2012. The prediction of functional decline in older hospitalised patients. Age and ageing 41 (3), 381–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoogerduijn JG, Schuurmans MJ, Korevaar JC, Buurman BM, de Rooij SE, 2010. Identification of older hospitalised patients at risk for functional decline, a study to compare the predictive values of three screening instruments. In, J Clin Nurs. England, pp. 1219–1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H-T, Chang C-M, Liu L-F, Lin H-S, Chen C-H, 2013. Trajectories and predictors of functional decline of hospitalised older patients. Journal of Clinical Nursing 22 (9/10), 1322–1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeangsawang N, Malathum P, Panpakdee O, Brooten D, Nityasuddhi D, 2012. Comparison of outcomes of discharge planning and post-discharge follow-up care, provided by advanced practice, expert-by-experience, and novice nurses, to hospitalized elders with chronic healthcare conditions. Int J Res Nurs 16 (4), 343–360. [Google Scholar]

- Kane RL, & Kane RA, 2000. Assessing older persons. Oxford University. [Google Scholar]

- Katja P, Timo T, Taina R, Tiina-Mari L, 2014. Do mobility, cognitive functioning, and depressive symptoms mediate the association between social activity and mortality risk among older men and women? European Journal of Ageing, 11(2), 121–130. doi: 10.1007/s10433-013-0295-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW, 1963. STUDIES OF ILLNESS IN THE AGED. THE INDEX OF ADL: A STANDARDIZED MEASURE OF BIOLOGICAL AND PSYCHOSOCIAL FUNCTION. Jama 185, 914–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kind AJ, Jensen L, Barczi S, Bridges A, Kordahl R, Smith MA, Asthana S, 2012. Low-cost transitional care with nurse managers making mostly phone contact with patients cut rehospitalization at a VA hospital. Health Affairs, 31(12), 2659–2668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton MP, Brody EM, 1969. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist 9 (3), 179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lennartsson C, Silverstein M, 2001. Does engagement with life enhance survival of elderly people in Sweden? The role of social and leisure activities. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 56(6), S335–S342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li AK, Covinsky KE, Sands LP, Fortinsky RH, Counsell SR, Landefeld CS, 2005. Reports of financial disability predict functional decline and death in older patients discharged from the hospital. J Gen Intern Med 20 (2), 168–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney FI, Barthel DW, 1965. FUNCTIONAL EVALUATION: THE BARTHEL INDEX. Md State Med J 14, 61–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney JE, Sager MA, Jalaluddin M, 1999. Use of an ambulation assistive device predicts functional decline associated with hospitalization. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 54 (2), M83–M88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martín SM, Cruz-Jentoft A, 2012. Impact of hospital admission on functional and cognitive measures in older subjects. European Geriatric Medicine 3 (4), 208–212. [Google Scholar]

- McMurdo ME, Price RJ, Shields M, Potter J, Stott DJ, 2009. Should oral nutritional supplementation be given to undernourished older people upon hospital discharge? A controlled trial. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 57 (12), 2239–2245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael R, Wichmann H, Wheeler B, Horner B, Downie J, 2005. The Healthy Ageing Unit: Beyond discharge. Journal of the Australasian Rehabilitation Nurses’ Association (JARNA) 8 (4). [Google Scholar]

- Millán-Calenti JC, Tubío J, Pita-Fernández S, González-Abraldes I, Lorenzo T, Fernández-Arruty T, Maseda A, 2010. Prevalence of functional disability in activities of daily living (ADL), instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) and associated factors, as predictors of morbidity and mortality. Archives of gerontology and geriatrics 50 (3), 306–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minosso JSM, Amendola F, Alvarenga MRM, Oliveira MAd.C., 2010. Validation of the Barthel Index in elderly patients attended in outpatient clinics, in Brazil. Acta Paulista de Enfermagem 23 (2), 218–223. [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, 2009. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Annals of internal medicine 151 (4), 264–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naylor MD, Brooten D, Campbell R, Jacobsen BS, Mezey MD, Pauly MV, Schwartz JS, 1999. Comprehensive discharge planning and home follow-up of hospitalized elders: a randomized clinical trial. Jama, 281(7), 613–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naylor MD, Brooten DA, Campbell RL, Maislin G, McCauley KM, Schwartz JS, 2004. Transitional care of older adults hospitalized with heart failure: a randomized, controlled trial. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 52(5), 675–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naylor MD, Hirschman KB, Hanlon AL, Bowles KH, Bradway C, McCauley KM, Pauly MV, 2014. Comparison of evidence-based interventions on outcomes of hospitalized, cognitively impaired older adults. J Comp Eff Res, 3(3), 245–257. doi: 10.2217/cer.14.14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niti M, Yap K-B, Kua E-H, Tan C-H, Ng T-P, 2008. Physical, social and productive leisure activities, cognitive decline and interaction with APOE-4 genotype in Chinese older adults. International Psychogeriatrics, 20(2), 237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostir GV, Volpato S, Kasper JD, Ferrucci L, Guralnik JM, 2001. Summarizing amount of difficulty in ADLs: a refined characterization of disability. Results from the women’s health and aging study. Aging (Milano) 13 (6), 465–472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parlevliet JL, MacNeil‐Vroomen J, Buurman BM, Rooij SE, Bosmans JE, 2016. Health‐Related Quality of Life at Admission Is Associated with Postdischarge Mortality, Functional Decline, and Institutionalization in Acutely Hospitalized Older Medical Patients. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 64 (4), 761–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasina L, Djade CD, Lucca U, Nobili A, Tettamanti M, Franchi C, Salerno F, Corrao S, Marengoni A, Iorio A, Marcucci M, Violi F, Mannucci PM, 2013. Association of anticholinergic burden with cognitive and functional status in a cohort of hospitalized elderly: comparison of the anticholinergic cognitive burden scale and anticholinergic risk scale: results from the REPOSI study. Drugs Aging 30 (2), 103–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierluissi E, Mehta KM, Kirby KA, Boscardin WJ, Fortinsky RH, Palmer RM, Landefeld CS, 2012. Depressive symptoms after hospitalization in older adults: function and mortality outcomes. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 60 (12), 2254–2262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polit DF, Beck CT, 2004. Nursing research: Principles and methods. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- Ranhoff AH, Laake K, 1993. The Barthel ADL index: scoring by the physician from patient interview is not reliable. Age Ageing 22 (3), 171–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards SH, Peters TJ, Coast J, Gunnell DJ, Darlow MA, Pounsford J, 2000. Inter-rater reliability of the Barthel ADL index: how does a researcher compare to a nurse? Clin Rehabil 14 (1), 72–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy C, Togneri J, Hay E, Pentland B, 1988. An inter-rater reliability study of the Barthel Index. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research 11 (1), 67–70. [Google Scholar]

- Rubenstein LZ, Schairer C, Wieland GD, Kane R, 1984. Systematic biases in functional status assessment of elderly adults: effects of different data sources. Journal of Gerontology 39 (6), 686–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sager MA, Dunham NC, Schwantes A, Mecum L, Halverson K, Harlowe D, 1992. Measurement of Activities of Daily Living in Hospitalized Elderly: A Comparison of Self‐Report and Performance‐Based Methods. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 40 (5), 457–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sager MA, Franke T, Inouye SK, Landefeld CS, Morgan TM, Rudberg MA, Sebens H, Winograd CH, 1996a. Functional outcomes of acute medical illness and hospitalization in older persons. Arch Intern Med 156 (6), 645–652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sager MA, Rudberg MA, Jalaluddin M, Franke T, Inouye SK, Landefeld CS, Siebens H, Winograd CH, 1996b. Hospital Admission Risk Profile (HARP): identifying older patients at risk for functional decline following acute medical illness and hospitalization. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 44 (3), 251–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sands LP, Landefeld CS, Ayers SM, Yaffe K, Palmer R, Fortinsky R, Counsell SR, Covinsky KE, 2005. Disparities between black and white patients in functional improvement after hospitalization for an acute illness. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 53 (10), 1811–1816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sands LP, Yaffe K, Covinsky K, Chren M-M, Counsell S, Palmer R, Fortinsky R, Landefeld CS, 2003. Cognitive screening predicts magnitude of functional recovery from admission to 3 months after discharge in hospitalized elders. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 58 (1), M37–M45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah S, Vanclay F, Cooper B, 1989. Improving the sensitivity of the Barthel Index for stroke rehabilitation. J Clin Epidemiol 42 (8), 703–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein M, Parker MG, 2002. Leisure activities and quality of life among the oldest old in Sweden. Research on aging, 24(5), 528–547. [Google Scholar]

- Sinoff G, Ore L, 1997. The Barthel Activities of Daily Living Index: Self‐Reporting Versus Actual Performance in the Old‐Old (≥ 75 years). Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 45 (7), 832–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trochim WM, Donnelly JP, 2001. Research methods knowledge base. [Google Scholar]

- Vittengl JR, White CN, McGovern RJ, Morton BJ, 2006. Comparative validity of seven scoring systems for the instrumental activities of daily living scale in rural elders. Aging & Mental Health 10 (1), 40–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpato S, Cavalieri M, Sioulis F, Guerra G, Maraldi C, Zuliani G, Fellin R, Guralnik JM, 2011. Predictive value of the Short Physical Performance Battery following hospitalization in older patients. In, J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. United States, pp. 89–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiting P, Savović J, Higgins JP, Caldwell DM, Reeves BC, Shea B, Davies P, Kleijnen J, Churchill R, 2016. ROBIS: a new tool to assess risk of bias in systematic reviews was developed. Journal of clinical epidemiology 69, 225–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu HY, Sahadevan S, Ding YY, 2006. Factors associated with functional decline of hospitalised older persons following discharge from an acute geriatric unit. Ann Acad Med Singapore 35 (1), 17–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo D, Faleiro R, Lincoln N, 1995. Barthel ADL Index: a comparison of administration methods. Clinical Rehabilitation 9 (1), 34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Zaslavsky O, Zisberg A, Shadmi E, 2015. Impact of functional change before and during hospitalization on functional recovery 1 month following hospitalization. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 70 (3), 381–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zisberg A, Shadmi E, Gur-Yaish N, Tonkikh O, Sinoff G, 2015. Hospital-Associated Functional Decline: The Role of Hospitalization Processes Beyond Individual Risk Factors. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 63 (1), 55–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zisberg A, Shadmi E, Sinoff G, Gur-Yaish N, Srulovici E, Admi H, 2011. Low mobility during hospitalization and functional decline in older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 59 (2), 266–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]