Abstract

Radioactive and stable isotopes have been applied for decades to elucidate metabolic pathways and quantify carbon flow in cellular systems using mass and isotope balancing approaches. Isotope-labeling experiments can be conducted as a single tracer experiment, or as parallel labeling experiments. In the latter case, several experiments are performed under identical conditions except for the choice of substrate labeling. In this review, we highlight robust approaches for probing metabolism and addressing metabolically related questions though parallel labeling experiments. In the first part, we provide a brief historical perspective on parallel labeling experiments, from the early metabolic studies when radioisotopes were predominant to present-day applications based on stable-isotopes. We also elaborate on important technical and theoretical advances that have facilitated the transition from radioisotopes to stable-isotopes. In the second part of the review, we focus on parallel labeling experiments for 13C-metabolic flux analysis (13C-MFA). Parallel experiments offer several advantages that include: tailoring experiments to resolve specific fluxes with high precision; reducing the length of labeling experiments by introducing multiple entry-points of isotopes; validating biochemical network models; and improving the performance of 13C-MFA in systems where the number of measurements is limited. We conclude by discussing some challenges facing the use of parallel labeling experiments for 13C-MFA and highlight the need to address issues related to biological variability, data integration, and rational tracer selection.

Keywords: Metabolism, isotopic tracers, stable isotopes, metabolic network model, tracer experiment design

1. INTRODUCTION

Cellular metabolism provides cells with the necessary precursors, energy (ATP) and electrons (NADH, NADPH) needed for cell growth, maintenance, and other essential cellular functions. The nature of metabolic pathways and their central role in cellular life have been the focus of research since the early 20th century (Kohler, 1977). Much of the initial work focused on elucidating the structure of metabolic pathways, whereas recent work addressed quantitative analysis of mass flow in metabolic systems through metabolic flux analysis (MFA) (Leighty and Antoniewicz, 2011; Toya et al., 2011). The research has contributed to important advances in a wide spectrum of applications, including understanding disease phenotypes (e.g. diabetes, cancer) (DeBerardinis et al., 2008; Jensen et al., 2008; Kelleher, 2001; Kelleher, 2004); development of noninvasive methods for probing metabolism using blood and urine analysis (Burgess et al., 2003; Yang et al., 1993; Yang et al., 1996); and reengineering cellular phenotypes to produce valuable products from renewable resources through metabolic engineering (Becker and Wittmann, 2012; Boghigian et al., 2010; de Jong et al., 2012; Iwatani et al., 2008; Lee et al., 2012; Niklas et al., 2010).

Central to the study of metabolic pathways, both in the 20th and 21st century is the use of isotopic tracers (Bier, 1987; Klein and Heinzle, 2012; Matwiyoff and Ott, 1973). An isotopic tracer is a molecule in which a specific atom, or atoms, has been replaced with a different isotope. The isotope can be either radioactive (e.g. 14C, 3H), or stable (e.g. 13C, 2H, 18O, 15N). Isotopic tracers have been applied for a variety of purposes in metabolic pathway analysis. A straightforward application of isotopic tracers is to probe whether a given pathway exists and how active it is, for example, by measuring the accumulation of isotopic labeling in a metabolic end-product of the pathway. Tracers can also provide insights into the structure of pathways, stereochemistry of enzymatic reactions, presence of converging pathways, and relative activity of competing pathways (Crown et al., 2011; de Graaf and Venema, 2008; Kruger et al., 2012; Quek et al., 2010).

Whether a tracer experiment is conducted with radioactive or stable isotopes, the experimental process shares a number of key steps. First, an isotopic tracer is introduced to the biological system, which can be as simple as a single organism culture, e.g. E. coli batch culture, or as complex as a human patient. Depending on the organism investigated, the tracer experiment may be performed in vitro, as in the perfusion of tissues isolated from animals; or in vivo, as in the direct incorporation of tracers into a complete functioning organism. Secondly, sufficient incubation time is allowed such that incorporation of the tracer into cellular metabolism can proceed. The third step is the isolation of the labeled metabolites. In the case of microbes and cultured cells, intracellular and extracellular metabolites can be obtained by extraction (Garcia et al., 2008). For in vivo studies (e.g. with humans), noninvasive methods must be used and this is commonly done through blood or urine analyses (Burgess et al., 2003; Yang et al., 1993; Yang et al., 1996). The next step is the measurement of labeling that has been incorporated into the metabolites of interest. In the case of radioactive tracers, the total radioactivity of a metabolite is assayed, or in some cases, the specific activity of metabolite carbons (14C) or hydrogens (3H) (Wolfe, 2004). For stable-isotope tracers, the incorporation can be detected using techniques such as nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) (Schleucher et al., 1998; Szyperski, 1995), mass spectrometry (MS) (Antoniewicz et al., 2007a; Antoniewicz et al., 2011), and tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) (Antoniewicz, 2013; Choi et al., 2012; Jeffrey et al., 2002). The final step involves interpretation of the enrichment data, which can be purely qualitative, such as whether certain metabolites incorporate tracer atoms, or more quantitative, such as model-based analysis.

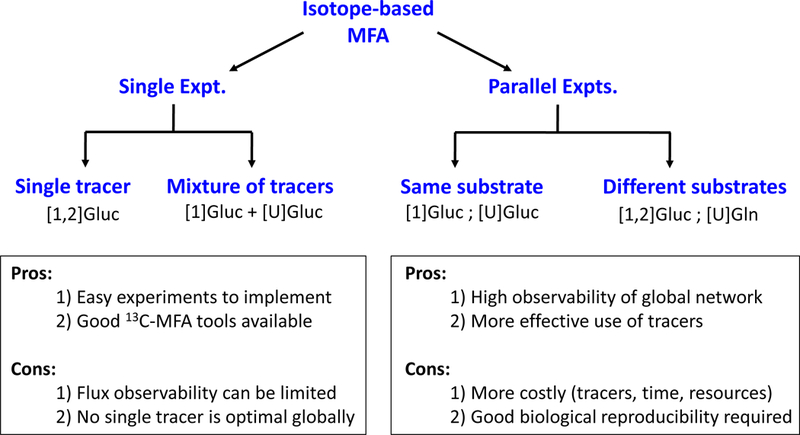

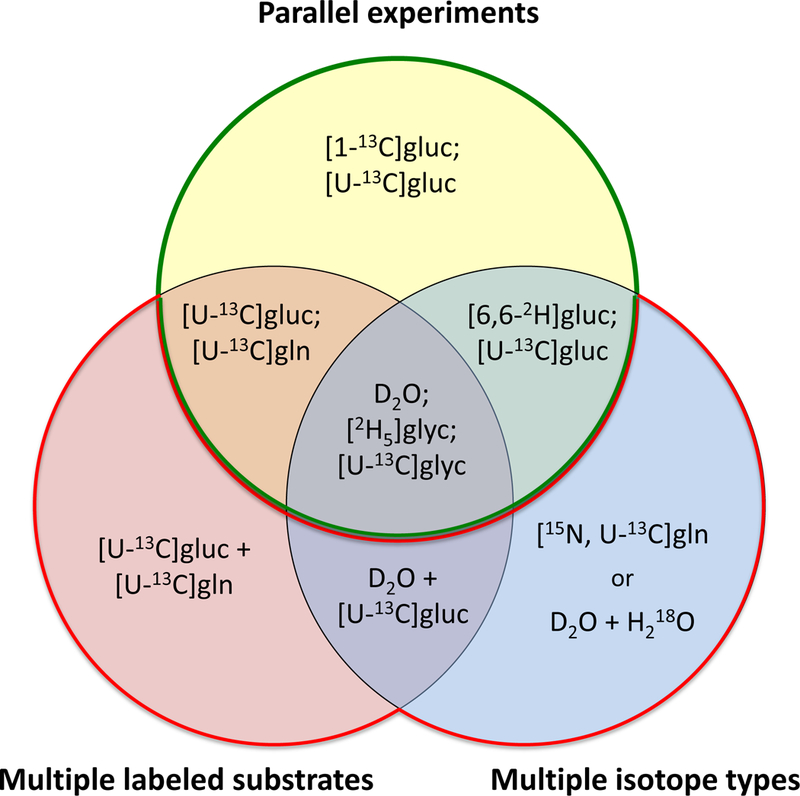

Isotopic experiments can be divided into two major categories: i) single labeling experiments, and ii) parallel labeling experiments (Fig. 1). For a single labeling experiment design, only one experiment is conducted, which can involve the use of a single labeled substrate (e.g. [1,2-13C]glucose), a mixture of tracers of the same compound (e.g. a mixture of [1-13C]glucose and [U-13C]glucose), or multiple labeled substrates (e.g. [U-13C]glucose and [U-13C]glutamine). For a parallel labeling experiment design, two or more tracer experiments are conducted in parallel. In each experiment a different tracer set is used. As shown in Fig. 2, parallel labeling experiments can be performed in a multitude of configurations. Typically, parallel experiments are started from the same seed culture to minimize biological variability (Ahn and Antoniewicz, 2013; Antoniewicz, 2006).

Figure 1.

Experimental designs for single tracer experiments and parallel labeling experiments. Major advantages and disadvantages of both approaches are highlighted. [1]Gluc denotes [1-13C]glucose. [U]Gln denotes [U-13C]glutamine. A semicolon “;” denotes parallel experiments. A plus-sign “+” indicates multiple tracers used in a single experiment.

Figure 2.

Tracer experiment designs using parallel experiments, multiple labeled substrates, and multiple isotope types. A semicolon “;” denotes parallel experiments and a plus-sign “+” indicates multiple tracers used in a single experiment.

The goal of this review article is to highlight parallel labeling approaches for probing metabolism and addressing metabolically related questions. We are particularly interested in these studies because of the synergy of complementary information that can be obtained through the use of parallel labeling experiments. In the first part of the review, we provide a brief historical perspective. We discuss research from early 20th century when mainly radioisotopes were used, and then highlight major technical and computational advances that ushered in the use of stable-isotopes as the predominant technique for probing cellular metabolism. In the second part, we discuss the use of parallel labeling experiments in the context of metabolic flux analysis, focusing mainly on 13C-MFA. We discuss the advantages of using parallel labeling experiments in comparison to a single tracer experiment design, and describe methodologies that can be used for optimal selection of isotopic tracers. Finally, we highlight recent advances in integrative flux analysis of parallel labeling experiments, and conclude by discussing potential challenges and limitations of parallel labeling experiments for 13C-MFA.

2. HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE: FROM RADIOISOTOPES TO STABLE-ISOTOPES

The use of isotopic tracers to study cellular metabolism has its roots in the 1930s. The seminal studies by Schoenheimer and Rittenberg marked the beginning of modern biochemistry (Kohler, 1977; Schoenheimer and Rittenberg, 1938; Schoenheimer and Rittenberg, 1940). Radioisotopes (e.g. 3H, 14C) were used intensively to catalog many of the metabolic pathways that are well-known today (Wolfe, 1984; Wolfe, 2004). Applications of radioactive tracers predominated metabolism research until the 1980s, when stable-isotopes became a feasible alternative due to advances in NMR and MS technologies and computational methods (Bier, 1987). Presently, stable-isotope experiments account for the majority of metabolic and flux studies. There are several practical benefits of using stable-isotopes, including the lack of radioactive emission and the ease of detection by MS and NMR (Des Rosiers et al., 2004). In the first part of this section, we highlight the use of radioisotope experiments for metabolism research. Next, we outline major technological and theoretical advances that allowed stable-isotopes to come to the forefront. Finally, we elaborate on the important role that stable-isotopes currently play for advancing our knowledge of metabolism, with a focus on parallel labeling experiments.

2.1. Radioisotopes and parallel labeling experiments

The value of using radioisotopes to study metabolism was first recognized by Hevesy who performed the first biological isotope-tracer studies (Hevesy, 1923). Because of the simplicity of measuring radioisotopes by scintillation counting and the relative ease of their production, i.e., relative to the challenges encountered in concentrating stable-isotopes in the early 20th century, radioactive isotopes were applied intensively in the decades that followed for biological research. A typical radioisotope experiment involved dosing cells with a small amount of a radioactive substrate and measuring the radioactivity in cellular metabolites and end-products. Activity measurements were often restricted to metabolites that were abundant in the cell and were easily isolated from other cellular components, such as glucose, lipid glycerol, fatty acids, lactate, and CO2 (Jeffrey et al., 1991). Radioactivity was generally measured as total activity for the entire molecule, although in some cases the activity of individual carbon atoms or hydrogen atoms could be obtained as well, e.g. after chemical or enzymatic degradation of metabolites.

Radioisotope experiments have commonly been conducted with two or more isotopic tracers in parallel experiments, where each radioactive tracer specifically targeted a particular pathway. Differences in the radioactivity between experiments provided insight into a pathway’s structure and activity. One such application, for example, addressed how pentose sugar phosphates were assembled into hexose phosphates. Horecker et al. (Horecker et al., 1954) applied [1-14C]ribose-5-phosphate and [2,3-14C]pentose-5-phosphates to rat liver tissues and measured specific activities of hexose-6-phosphate carbons, eventually elucidating the structure of the non-oxidative pentose phosphate pathway. Parallel radioisotope experiments were also applied to determine the structure, precursors and activity of other pathways in central and peripheral metabolism, including pentose phosphate pathway (Katz and Wood, 1960; Katz and Wood, 1963; Wang et al., 1956), gluconeogenesis (Hostetler et al., 1969; Mullhofer et al., 1977; White et al., 1968), anaplerosis (D’Adamo and Haft, 1965; Landau et al., 1960), fatty acid metabolism (Antony and Landau, 1968; Brown et al., 1956; Kam et al., 1978; Robinson and Williamson, 1977), and mevalonate shunt (Brady et al., 1982b; Edmond and Popjak, 1974; Weinstock et al., 1984). In addition, parallel experiments were applied to challenge assumptions regarding equilibration of hexose-6-phosphate pools (Katz and Rognstad, 1969; Landau and Bartsch, 1966; Landau et al., 1964), to investigate the magnitude of exchange fluxes (Katz et al., 1966; Landau and Bartsch, 1966), and examine CO2 isotopic equilibration and compartmentation (Marsolais et al., 1987). In addition to parallel experiments, different isotope-types (e.g. 3H,14C-labeled glucose) were sometimes used, for example, to determine hydrogen exchange by isomerization reactions (Katz and Rognstad, 1966; Katz and Rognstad, 1969).

For quantitative studies of metabolism, empirical equations relating specific fluxes, e.g. fluxes at specific branch points, to activity measurements or 14CO2 yields were derived using mass balances. The oxidative pentose phosphate pathway (oxPPP) and pyruvate carboxylase/pyruvate dehydrogenase (PC/PDH) fluxes have been among the most heavily investigated. As an example, triose-phosphate activities and 14CO2 yields measured from parallel experiments with [1-14C]glucose or [6-14C]glucose were used to estimate the oxPPP flux (Katz and Wood, 1960; Katz and Wood, 1963; Landau et al., 1964). Similarly, 14CO2 yields have been applied to parallel experiments with [1-14C] + [2-14C]acetate (Goebel et al., 1982; Kelleher, 1985; Strisower et al., 1952; Weinman et al., 1957), or [1,4-14C] + [2,3-14C]succinate (Kelleher and Bryan, 1985) to determine the flux split between PC and PDH reactions. In other studies, parallel experiments were used to relate fluxes in subnetworks to specific activities of metabolites such as glucose, lipid glycerol, lactate, glutamate, and 14CO2. As an example, Rognstad and Katz (Rognstad and Katz, 1972) utilized [2-14C] + [3-14C]pyruvate/lactate to estimate gluconeogenic and TCA cycle fluxes in kidney slides; and Borowitz et al. (Borowitz et al., 1977) used a variety of glucose, fructose, ribose, and glycerol tracers to determine changes in the glycolytic flux in Tetrahymena.

Throughout the decades, radioisotope experiments have significantly contributed to the overall understanding of metabolism (Table 1). However, radioisotope experiments also suffer from several key limitations (Jeffrey et al., 1991). First, there is the practical limitation on the number of measurements that can be obtained from these experiments; and second, elaborate metabolite isolation protocols are often needed in these studies. As a consequence, radioactive experiments often rely on a few abundant and easily measured metabolites for analysis of metabolism. In addition, computational interpretation of data often requires numerous assumptions, some of which are known to be poor approximations, e.g. the assumption that 14CO2 is only evolved from reactions in the TCA cycle; or that complete isotopic equilibrium exists between certain metabolites in glycolysis and other pathways. It is also important to note that many models relating specific activities to fluxes involved equations that included empirical parameters, some of which were not rigorously derived. As a result, the information obtained from radioactive experiments was confined to estimating only a handful of fluxes, rather than gaining a comprehensive understanding of metabolism. Despite these caveats, radioisotope experiments are still used presently for a variety of purposes, including the measurement of substrate uptake and product excretion rates (Allen et al., 2009; Alonso et al., 2011), and investigation of in vivo glucose and lipid dynamics (Jensen et al., 2001a; Jensen et al., 2001b; Previs et al., 2000).

Table 1.

Radioisotope studies with parallel labeling experiments

| Organism | Tracers | Measurements | Major achievements | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rat liver slices | [1]ac; [2]ac | Gluc, 14CO2 activity | Quantified isotopic dilution in TCA cycle | (Strisower et al., 1952) |

| Rat liver | [1]r5p; [2,3]p5p | Activity of h6p carbons | Determined structure of non-oxPPP | (Horecker et al., 1954) |

| Yeast | [1]; [2]; [6]; [U]gluc | 14CO2 activity | Estimated oxPPP, EMP and pyruvate fixation fluxes | (Wang et al., 1956) |

| n/a | [2]; [3]gluc | Activity of h6p carbons | Accounted for h6p recycling in estimation of oxPPP | (Katz and Wood, 1960) |

| Rat liver slices | [1]; [2]prop; [1]; [2]pyr; bicarb | Gluc, glycogen, FA, lact, 14CO2 activities | Elucidated pyruvate and propionate conversion to glucose and label shuffling in TCA cycle | (Landau et al., 1960) |

| Rat adipose tissue | [1]; [6]gluc | Lipid, 14CO2 activities | Evaluated methods for oxPPP estimation | (Katz and Wood, 1963) |

| Tissue slices | [1]; [6]gluc; [1]; [6]fruc | Glycerol, 14CO2 yields | Estimated oxPPP flux and hexose isomerization | (Landau et al., 1964) |

| Isolated rat liver | [2]; [5]glu | Gluc, 14CO2, FA, glycogen activities | Identified metabolism of akg to citrate via reductive carboxylation | (D’Adamo and Haft, 1965) |

| Rat liver | [1]; [2]ac; [1]; [16]palm; [18]stear; [10]ole | Activity of glycogen carbons | Examined relative contribution of α, β, and ω-oxidation of FA | (Antony and Landau, 1968) |

| Rat adipose tissue | [1]; [2]; [3]pyr; bicarb | Glycogen, glyc, FA, lact, 14CO2 activities | Probed pyruvate metabolism and glyceroneogenesis | (White et al., 1968) |

| Rat adipose tissue | [1-3H,14C]; [2-3H,14C]; [3-3H,14C]; [6-3H,14C]gluc |

3H in gluc, H2O; 3H:14C ratio in FA, glyc, lact | Investigated isotope discrimination and H-exchange by isomerization reactions | (Katz and Rognstad, 1969) |

| Kidney cortex slices | [2]; [3]lact; [2]; [3]pyr | Activity of gluc, lact, ala, glu carbons | Estimated TCA cycle and gluconeogenesis fluxes | (Rognstad and Katz, 1972) |

| Tetrahymena | Gluc, fruc, ribose, glyc tracers | Glycogen, glyc, RNA, 14CO2 activities | Estimated glycolysis and PPP fluxes | (Borowitz et al., 1977) |

| Rat liver | [1]; [2]lact; [1]; [2]pyr; [1]oct; bicarb | Activity of carbons, fragments and molecules | Extensive study on various gluconeogenic precursors | (Mullhofer et al., 1977) |

| Rat liver and kidney | Variety of palm tracers | Activity of hydroxy-butyric acid carbons | Probed multiple pathways for acetoacetate formation | (Brady et al., 1982a) |

| Rat liver | [1,4]; [2,3]succinate | 14CO2 yields | Determined pyruvate carboxylation/decarboxylation fluxes into TCA cycle | (Kelleher and Bryan, 1985) |

Notes: [1]gluc denotes [1-14C]gluc, unless stated otherwise. The semicolon “;” denotes parallel experiments.

Abbreviations: AA, amino acids; ac, acetate; acac, acetoacetate; akg, α-ketoglutarate; ala, alanine; asp, aspartate; bicarb, bicarbonate; CS, citrate synthase; FA, fatty acid; fruc, fructose; gln, glutamine; glu, glutamate; gluc, glucose; glyc, glycerol; h6p, hexose-6-phosphate; ile, isoleucine; ISA, isotopomer spectral analysis; lact, lactate; leu, leucine; lys, lysine; MIDA, mass isotopomer distribution analysis; MVA, mevalonate; oct, octanoate; ole, oleate; p5p; pentose-5-phosphate; palm, palmitate; prop, propionate; pyr, pyruvate; r5p, ribose-5-phosphate; stear, stearate; thr, threonine.

2.2. Technological advances allowing widespread use of stable-isotopes

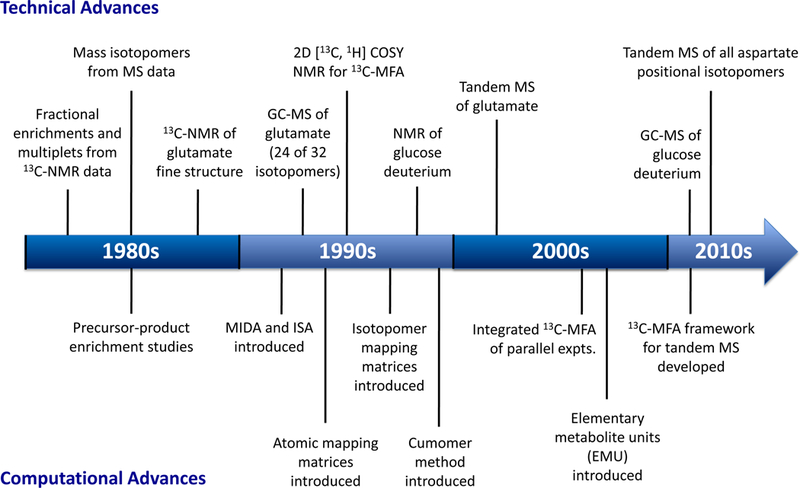

To quantify metabolism on a more global level than could be done with radioisotope studies, metabolic flux analysis (MFA) was developed based on stable-isotope experiments (Vallino and Stephanopoulos, 1993; Zupke and Stephanopoulos, 1995). The transition from radioisotopes to stable-isotopes was possible in a large part due to major advances in stable-isotope measurement techniques, including NMR and MS, and breakthroughs in computational capabilities and modeling approaches (Fig. 3). In the 1980s, stable-isotope techniques rapidly replaced radioisotope approaches as they were easier to conduct, allowed multiple measurements of isotopic enrichment from a single experiment, were safer to perform, and provided more informative data for flux determination (Bier, 1987; Matthews and Bier, 1983). In addition, several studies compared results from radioisotope and stable-isotope experiments and found only negligible differences between radioactivity assays and 13C-NMR (Cohen et al., 1981) and MS results (Strong et al., 1983).

Figure 3.

Timeline of important technical and computational advances that facilitated the transition from radioisotopes to stable-isotopes and further development of 13C-MFA.

For stable-isotope studies, quantification of individual positional isotopomers is ideally desired (Christensen and Nielsen, 1999). A positional isotopomer is defined as a molecule with a specific labeling pattern of its atoms. For a metabolite with n atoms, there are 2n possible positional isotopomers. Knowledge of the complete positional isotopomer distribution provides the complete labeling state of a metabolite. Early NMR techniques, such as 1H-NMR and 13C-NMR, could not resolve all positional isotopomers (Chance et al., 1983; Cohen, 1983; Malloy et al., 1988; Walker et al., 1982). Proton NMR (1H-NMR) only provided information regarding the fractional enrichments of carbons, while 13C-NMR measured multiplet structures that contained only partial labeling information. With the introduction of 2D-[13C, 1H]-COSY NMR (Szyperski, 1995), more detailed positional isotopomer information could be obtained; however, elucidation of the complete isotopomer distribution of molecules remains a challenge even today.

In the case of MS, multiple fragments of a molecule must be measured to obtain positional labeling information. As an example, with GC-MS analysis of multiple fragments it is possible to determine the complete positional isotopomer distribution of a few small molecules (Dauner and Sauer, 2000). In practice, MS methods measure mass isotopomers, which are isotopomers of molecules with the same mass-to-charge ratio (m/z). Through analysis of multiple MS fragments for a given metabolite the amount of labeling information can be increased. For example, Di Donato et al. (Di Donato et al., 1993) was able to obtain 24 of 32 positional isotopomers of glutamate, and Katz et al. (Katz et al., 1993) had similar success with other metabolites. With the introduction of tandem mass spectrometry, measuring complete positional isotopomer distributions is possible for larger molecules, as was recently demonstrated by Choi et al. for aspartate (Choi and Antoniewicz, 2011; Choi et al., 2012).

3. CURRENT APPROACHES BASED ON STABLE-ISOTOPES

3.1. Pathway structure elucidation

Stable isotopes, like their radioactive counterparts, have played an important role in elucidating metabolism. In many cases, parallel labeling experiments have provided valuable information to elucidate the structure and function of metabolic pathways (Table 2). With careful selection of isotopic tracers and quantitative isotopomer measurements, the activity of pathways can be determined and inconsistencies in a hypothesized network can be identified. Stable-isotope techniques have been applied to a variety of biological systems, for example, to quantify glucose metabolism via Embden-Meyerhof-Parnas (EMP), Entner Doudoroff (ED), and oxPPP (Blank et al., 2005; Fuhrer et al., 2005); to validate amino acid biosynthesis pathways, especially for organisms where multiple alternative routes are known to exist (Feng et al., 2009; Tang et al., 2010; Tang et al., 2009); to elucidate the exact stereochemistry of enzymatic reactions, e.g. Re- vs. Si-citrate synthase (Amador-Noguez et al., 2010; Feng et al., 2009; Tang et al., 2009); and to demonstrate bifurcation of TCA cycle in several microbes (Amador-Noguez et al., 2010; Olszewski et al., 2010). Through careful selection of isotopic tracers, several studies have also provided valuable information on the reversibility of reactions. For example, 13C-glutamate tracers were used by various investigators to quantify the exchange flux of isocitrate dehydrogenase and reductive carboxylation flux in the TCA cycle (Des Rosiers et al., 1994; Metallo et al., 2012; Yoo et al., 2004). Lastly, parallel tracer investigations have been applied to determine the structure of metabolic pathways outside of central metabolism, including the biosynthesis of isoprenoids (Schwender et al., 1996), polyketides (Simpson, 1998), polyalkanoates (Anderson and Dawes, 1990), and shikimate metabolites (Dewick, 1995).

Table 2.

Stable-isotope studies with parallel labeling experiments

| Organism | Tracers | Measurements | Major achievements | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isolated rat hepatocytes | 15NH4+; [5-15N]gln | MS - uracil | Related mass isotopomers to precursor enrichments and pyrimidine biosynthesis | (Strong et al., 1985) |

| Rat hearts | [3]pyr; [2]ac; [2]ac + [3]prop; [1,2]ac + [3]pyr | NMR - glutamate | Analyzed 13C-NMR spectra and modeled flux of TCA cycle | (Malloy et al., 1988) |

| 3T3-L1 adipocytes | [1]ac; [1,2]acac | MS - fatty acids | First ISA study on fatty acid synthesis | (Kharroubi et al., 1992) |

| Human Hep-G2 cells | [1]ac; [U]acac; [4,5]MVA; [1,2,3,4]oct | MS - cholesterol | Examined cholesterol synthesis as a polymerization of MVA precursors | (Kelleher et al., 1994) |

| Sprague-Dawley rats | [3]; [1]lact; [2]glyc; [6-3H]gluc |

MS - glucose | First MIDA study on gluconeogenesis pathway | (Neese et al., 1995) |

| Rat hearts | [1]oct; [U]lact + [U]pyr; [1]oct + [U]lact + [U]pyr; [U]glu; [U]ac | MS - citrate and its fragments | Estimated relative rates of PC/PDH/CS/FA oxidation | (Comte et al., 1997a) |

| C. glutamicum | [1]gluc; 40% [U]gluc | MS - ext. ala, lys, trehalose | Performed 13C-MFA using parallel data sets and ratios of M+x/M+0 isotopomers | (Wittmann and Heinzle, 2001a) |

| E. coli | [1]gluc; 20% [U]gluc | MS - biomass AA | Developed metabolic flux ratio analysis (MetaFor) | (Fischer and Sauer, 2003) |

| E. coli | [1]gluc; 20% [U]gluc | MS - biomass AA | Demonstrated improved flux observability with PLE’s | (Fischer et al., 2004) |

| C. glutamicum | [1]gluc; 50% [U]gluc or fruc | MS - ext. lys, trehalose | 13C-MFA with only external metabolite measurements | (Kiefer et al., 2004) |

| Brown adipocytes | [U]gluc; [U]gln; [U]ac; [U]acac | MS - fatty acids | Utilized ISA to quantify carbon sources for de novo lipogenesis | (Yoo et al., 2004) |

| Various bacteria | [1]gluc; 20% [U]gluc | MS - biomass AA | Quantified glucose metabolism via EMP/ED/oxPPP in several bacteria using MetaFor | (Fuhrer et al., 2005) |

| B. napus | [1,2]gluc + [U]gluc; [U]ala; 50% [U]gln | MS - biomass AA, FA, gluc, glyc | Integrated 13C-MFA: utilized [15N]-tracers to assess protein synthesis and turnover | (Schwender et al., 2006) |

| Isolated hepatocytes | [2H5]; [U]glyc; 2H2O | MS - glucose | Integrated 13C-MFA: quantified net and reversible fluxes in gluconeogenesis pathway | (Antoniewicz, 2006) |

| C. glutamicum | [1]; [6]; [1,6]gluc | MS - CO2 | 13C-MFA with CO2 as the only labeling measurement | (Yang et al., 2006) |

| Maize root tips | [1]; [2]gluc | NMR - int. sugars, AA | Integrated 13C-MFA: estimated fluxes from 13C-enrichments | (Alonso et al., 2007) |

| Soybean seedlings | [U]gluc; [U]gln | MS - biomass AA, int. sugars, organic acids | Integrated 13C-MFA: utilized two labeled substrates to improve flux resolution | (Allen et al., 2009) |

| D. ethenogenes | [1]; [2]ac; bicarb | MS - biomass AA | Elucidated pathways for ile, leu, thr biosynthesis, and identified Re-CS | (Tang et al., 2009) |

| C. acetobutylicum | [U]gluc; [U]glu; [U]asp; others | MS - int. metabolites | Demonstrated bifurcated TCA cycle and identified Re-CS | (Amador-Noguez et al., 2010) |

| P. falciparum | [U]gluc; [U-13C,15N]asp; [U-13C,15N]gln | MS - int. metabolites | Demonstrated bifurcation of TCA cycle and reductive carboxylation | (Olszewski et al., 2010) |

| HEK-293 | [1]; [6]; [U]gluc; [U]gln | MS - ext. lactate | 13C-MFA with lactate as the only labeling measurement | (Henry and Durocher, 2011) |

| E. coli | 20, 40, 60, 80, 100% [U]gluc | MS - biomass AA | Integrated 13C-MFA: identified exchange of CO2 and validated E. coli model for 13C-MFA | (Leighty and Antoniewicz, 2012) |

Notes: [1]gluc denotes [1-13C]gluc, unless stated otherwise. A semicolon “;” denotes parallel experiments, and plus-sign “+” denotes multiple tracers used in a single experiment. Abbreviations are same as in Table 1.

3.2. Empirical models and multiple isotopes

Empirical models relating NMR and MS data to carbon fluxes were popular in the 1980s and 1990s for data analysis, i.e. before the emergence of 13C-MFA. These models were often extensions of previously developed methods for analysis of radioisotope labeling studies. The models were often limited to a handful of measurements, such as NMR fine structures of glutamate, mass isotopomer distributions of TCA cycle intermediates, and deuterium enrichments of glucose; and were often based on many simplifying assumptions to make the calculations manageable. Although relatively simple compared to current 13C-MFA approaches, empirical modeling efforts led to several useful applications, for example, to quantify the relative utilization of competing substrates, measure fatty acid oxidation, study hepatic glucose production, quantify TCA cycle fluxes, and determine anaplerotic fluxes with a variety of pyruvate, acetate, lactate, glucose, glutamine and fatty acid tracers (Comte et al., 1997a; Comte et al., 1997b; Jones et al., 1993; Malloy et al., 1988; Malloy et al., 1990a; Malloy et al., 1990b; Sherry et al., 1988).

Since parallel labeling experiments are infeasible for studies involving living subjects, labeling experiments were also conducted using simultaneous infusions of multiple tracers and different isotopes. For example, to investigate glucose production in humans a tracer bolus of [1,6-13C]glucose, 2H2O, and [U-13C]propionate tracers had been used by Jones et al. (Jones et al., 2001), as well as several other combinations of tracers and isotopes (Chandramouli et al., 1997; Chevalier et al., 2006; Jin et al., 2005). Similarly, whole-body energy balance was routinely investigated using a doubly-labeled water approach, in which 2H2O and H218O were simultaneously injected into living subjects as a bolus and the differences in elimination rates of 2H and 18O from body water were monitored in time (Bederman et al., 2006; Brunengraber et al., 2002).

3.3. Emergence of 13C-metabolic flux analysis

Currently, 13C-MFA studies are the preferred method for obtaining detailed metabolic fluxes in microbial, mammalian and plant systems (Iwatani et al., 2008; Kruger et al., 2012; Quek et al., 2010). Current approaches are based on rigorous isotopomer balancing techniques that were established in mid-1990s (Schmidt et al., 1997; Zupke and Stephanopoulos, 1994). In the past decade, quantitative evaluation of metabolic fluxes using 13C-MFA has become a key activity in many research fields, including in metabolic engineering, systems biology and biomedical investigations (Kelleher, 2001; Moxley et al., 2009). The emergence of 13C-MFA as the preferred analysis method was spearheaded by the development of advanced computational approaches to comprehensively simulate all isotopomers in network models (see Fig. 3). With the isotopomer framework in place (Schmidt et al., 1997), fluxes could be finally determined for large-scale systems that encompassed most of central metabolism, including reversible reactions, as well as amino acids metabolism and fatty acid biosynthesis. The widespread use of 13C-MFA studies was also fueled by the development of easy-to-use programs for 13C-MFA such as 13CFLUX (Wiechert et al., 2001), OpenFlux (Quek et al., 2009), and Metran (Yoo et al., 2008).

The development of metabolic flux ratio analysis (Metafor) offered an alternative method to analyze mass spectrometry data and quantify fluxes, including from parallel labeling experiments (Fischer and Sauer, 2003). Metafor analysis essentially decouples amino acid mass isotopomers into the mass isotopomers of precursor metabolites, which are then used to determine flux ratios at specific convergence points in metabolism. Commonly, Metafor is conducted with parallel experiments using [1-13C]glucose and a mixture of [U-13C]/natural glucose (Fischer and Sauer, 2003; Fischer et al., 2004). Compared to 13C-MFA approaches, however, Metafor analysis has several drawbacks. First, the method relies on manually derived expressions that are specific to certain network models and tracers, which significantly limits which biological systems can be investigated. In addition, because not all MS and NMR data can be utilized for flux analysis, fluxes are determined with the same precision as with rigorous 13C-MFA methods.

4. PARALLEL LABELING EXPERIMENTS

In the past few years, the use of parallel labeling experiments (PLE’s) for 13C-MFA has increased significantly (Table 2). The main advantage of PLE’s is the potential to generate complementary labeling information that can dramatically improve the resolution of fluxes in complex systems (Allen et al., 2009; Alonso et al., 2010; Alonso et al., 2007; Leighty and Antoniewicz, 2012; Schwender et al., 2006). Comprehensive integration of data from PLE’s is accomplished by concurrently fitting measurements from multiple experiments to a single flux model (Antoniewicz, 2006). This type of integrated 13C-MFA approach returns, in the ideal case, a single set of fluxes that satisfies all isotopomer measurements from all parallel experiments.

4.1. Advantages of parallel labeling experiments

As we discussed in the previous sections, the use of PLE’s is a well-established concept in metabolism research. Thus far, most studies have focused on semi-quantitative data analysis. Recently, however, several integrative methods were described for comprehensive data analysis and 13C-MFA using parallel experiments (Antoniewicz, 2006; Leighty and Antoniewicz, 2012; Schwender et al., 2006). These developments represent a major step forward in 13C-MFA field. In this section, we discuss several advantages of using PLE’s for 13C-MFA compared to a single-tracer-experiment approach: i) tailoring 13C-experiments to resolve specific fluxes with high precision, ii) reducing the length of labeling experiments by introducing multiple entry-points of isotopes, iii) validating biochemical network models, and iv) improving performance of 13C-MFA in systems where the number of measurements is limited.

4.2. Tailoring 13C-experiments to resolve specific fluxes with high precision

One of the factors contributing to a poor resolution of fluxes when using a single tracer experiment is the structure of the network model itself. The network dictates the flow of 13C-atoms throughout the system and the labeling patterns that can be produced. For many biological systems, however, it is difficult to select one tracer that allows good flux observability for the entire network. PLE’s can offer an alternative solution to this problem.

It has been well known that for realistic network models there is rarely one optimal tracer that can simultaneous resolve all key fluxes with high precision (Crown et al., 2012; Metallo et al., 2009; Schellenberger et al., 2012). Studies have shown that different parts of central metabolism require different 13C-tracers. As an example, Metallo et al. (Metallo et al., 2009) identified optimal glucose and glutamine tracers for subnetworks of the mammalian network model with GC-MS measurements. It was determined that [1,2-13C]glucose was optimal for flux estimation of glycolysis and pentose phosphate pathway fluxes, while [U-13C]glutamine was found to be ideal for TCA cycle fluxes. In a similar study, we recently optimized glucose tracers for estimating oxPPP and PC fluxes in mammalian cells with lactate as the only measured metabolite (Crown et al., 2012). We found that [2,3,4,5,6-13C]glucose was optimal for resolving oxPPP flux and [3,4-13C]glucose was optimal for estimating PC flux. In addition to resolving net fluxes in a model, resolution of exchange fluxes can often require very specific labeling of tracers (Follstad and Stephanopoulos, 1998; Metallo et al., 2009). Similarly, resolution of metabolic cycles in eukaryotic cells (e.g. cross-compartmental pyruvate cycling) is challenging when using only a single tracer experiment (Wahrheit et al., 2011; Zamboni, 2011).

In general, the PLE approach provides the researcher with more design flexibility. Separate experiments can be performed in parallel with carefully selected tracers to accurately quantify specific fluxes of interest. As an example, for the mammalian network model, two experiments could be run in parallel using the two optimal tracers identified by Metallo et al. (Metallo et al., 2009). The labeling data from each experiment could then be integrated to achieve improved flux resolution. In simulation studies we have found that when multiple 13C-labeled substrates are used for 13C-MFA, it is often more advantageous to run the experiments in parallel rather than using all tracers in a single experiment. For example, introducing [1,2-13C]glucose and [U-13C]glutamine simultaneously in a single experiment produces less informative labeling data than if two separate experiments are performed with [1,2-13C]glucose and [U-13C]glutamine independently.

We believe that there are two major factors contributing to improved flux precision for parallel experiments. First, the increased number of measurements (i.e. twice the number of measurements for two PLE’s compared to a single tracer experiment) can result in an improvement of the flux precision. Second, and perhaps more importantly, parallel experiments provide complementary information for each other, which may aid in improved flux precision. For example, two tracers may provide poor flux precision when used in single tracer experiments, but may excel when analyzed in a parallel experimental design. The resulting improvement or “tracer synergy” distinguishes parallel labeling experiments from single tracer experiments; however, presently these synergistic effects are not well understood and should be further investigated.

4.3. Reducing length of labeling experiments by introducing multiple entry-points of isotopes

Another application of PLE’s is to reduce the labeling time needed to achieve isotopic steady-state, which can greatly simplify the modeling work needed for 13C-MFA. As an example, in mammalian cells isotopic steady-state is often not obtained for all relevant metabolites in a practical time frame (Ahn and Antoniewicz, 2011). Although it is possible to apply isotopic non-stationary 13C-MFA to calculate fluxes, this is still a challenging approach that requires significant experimental and computational effort (Young et al., 2008). As a result, isotopic non-stationary 13C-MFA is still not widely used in the metabolic engineering community. An alternative PLE approach would consist of conducting experiments in parallel with carefully selected entry-points for 13C-tracers such that isotopic steady state can be achieved quickly for the relevant metabolites. We have found, for example, that in CHO cells glycolysis and pentose phosphate pathway metabolites rapidly approach isotopic steady-state when glucose tracers are used, and very fast labeling dynamics are observed for TCA metabolites when glutamine tracers are used (Ahn and Antoniewicz, 2013). Using the PLE strategy, two experiments can be run in parallel with glucose and glutamine tracers, thus allowing for isotopic steady-state to be reached for all relevant metabolites within a short time frame. Using this approach, metabolic fluxes can then be calculated using stationary 13C-MFA methods instead of isotopic non-stationary 13C-MFA (Ahn and Antoniewicz, 2013).

4.4. Validating biochemical network models

A central premise of 13C-MFA is the assumption that the network model used for flux calculations is complete, i.e., that the model accounts for all significant enzymatic and transport reactions occurring in the biological system. In the current post-genomic era, experimental validation of metabolic network models is an increasingly important activity, as genome-scale models are constructed for newly sequenced organisms at an ever increasing pace, including for many poorly characterized microbes (Kim et al., 2012). These automatically generated models are likely to contain many errors, e.g. missing reactions and incorrect annotations. The PLE methodology is ideally suited for quantitative dissection of complex metabolic systems and may be especially instrumental for validating metabolic network models and quantifying metabolic phenotypes for less well studied organisms. We believe that PLE’s can have a significant impact on improving basic biology understanding in the coming years.

A key advantage of PLE’s for model validation is that these experiments provide significantly more independent measurements that place more stringent constraints on the network model assumptions. A recent study from our group demonstrates the utility of PLE’s for model validation. Here, E. coli was grown in parallel cultures on varying mixtures of natural glucose and [U-13C]glucose (0, 20, 40, 60, 80, 100%) (Leighty and Antoniewicz, 2012). A common assumption when performing 13C-MFA in microbial systems is that CO2 incorporated via carboxylation reactions has the same labeling as CO2 that is generated inside the cells via decarboxylation reactions. However, we demonstrated that 13C-MFA produced inconsistent flux results with this common assumption. On the other hand, an updated model that accounted for external CO2 incorporation into central metabolism, i.e. air naturally contains about 0.04% unlabeled CO2, produced statistically acceptable fits for parallel labeling experiments with good flux agreement.

4.5. Improving performance of 13C-MFA in systems where the number of measurements is limited

PLE’s also offer significant advantages for resolving fluxes in systems where the number of measurements is low due to limitations of the measurement technique, or due to limited number of accessible metabolites. In these circumstances the number of free fluxes may be equal or greater than the number of independent measurements, and the system may be poorly resolved, or not observable at all, when using a single tracer experiment strategy. In these cases, PLE’s can be used to increase the number of independent measurements. As such, flux resolution can be improved and biological systems that were previously poorly determined, or non-observable, may become fully observable. The application of PLE’s for increasing the number of redundant measurements in poorly resolved systems has been demonstrated already in several studies.

For example, PLE’s were used to determine fluxes in Corynebacteria from measured mass isotopomers of extracellular products (Kiefer et al., 2004; Wittmann and Heinzle, 2001a; Wittmann and Heinzle, 2002; Wittmann et al., 2004). Given that a single experiment did not provide enough constraints to calculate all fluxes, parallel experiments with [1-13C]glucose and a mixture of [U-13C]/natural glucose were conducted. PLE’s were also conducted with 13C-glucose and 13C-glutamine tracers to determine fluxes in mammalian cells using mass isotopomer measurements of secreted lactate as the only measured metabolite (Henry and Durocher, 2011; Niklas et al., 2011; Strigun et al., 2012). As a third example, Yang et al. (Yang et al., 2006) proposed a 13C-respirometry flux analysis methodology to analyze the metabolism of Corynebacterium glutamicum using only 13C-enrichment data from evolved CO2. To make the system observable, three experiments were conducted in parallel, with [1-13C]glucose, [6-13C]glucose and [1,6-13C]glucose.

5. FUTURE OUTLOOK

5.1. Selection of 13C-tracers for parallel labeling experiments

Parallel labeling experiments require careful selection of tracers to take full advantage of the additional experimental effort required. The significance of a judicious selection of tracers for flux analysis has been known since the early years of 13C-MFA, i.e. even for single tracer experiments (Follstad and Stephanopoulos, 1998; Mollney et al., 1999; Wittmann and Heinzle, 2001b). The choice of the isotopic tracer determines which isotopomers of a metabolite can be formed in a network and the sensitivities of isotopic measurements with respect to flux changes, which are directly related to the precision with which fluxes can be determined. Despite the importance of proper tracer selection, this step is still often over-looked or given very little thought.

One of the predominant methods for tracer selection and experiment design is based on a grid-search type of approach. The process involves calculating the parameter covariance matrix for various isotopic tracers of interest. For these calculations an assumed measurement set, a set of fluxes, and an assumed network model are needed. To compare between different tracers and determine which tracer is optimal for a given system, the D-optimality criterion is commonly used (Mollney et al., 1999). The D-optimality criterion is related to the covariance matrix of the free fluxes and provides a measure of single parameter confidence intervals and correlations between the estimated parameters. A relative information score for each tracer is then determined from the D-optimality criterion, given an assumed reference tracer experiment. The tracer scheme that produces the highest information score is then selected as the optimal tracer (Arauzo-Bravo and Shimizu, 2003; Noh and Wiechert, 2006; Yang et al., 2006).

The use of the covariance matrix for tracer experiment design relies on the inherent assumption that the underlying non-linear isotopomer balances can be approximated by linearization near the optimal solution. Metallo et al. (Metallo et al., 2009) introduced another method using a precision scoring system, which captures the true nonlinearity behavior of flux analysis systems. The precision scoring method requires the calculation of nonlinear confidence intervals for free fluxes (Antoniewicz et al., 2006). The method computes a score for each flux, based on the upper and lower bounds for the confidence intervals, and using a flux weighting parameter. If a flux has a score of zero, it is unidentifiable; if the score is one, the flux is optimally identifiable. The precision score is the sum of the scores for each flux. Similar to the grid-search method, precision scores are compared for various tracers of interest and the tracer that has the highest score is selected as optimal. Walther et al. (Walther et al., 2012) recently proposed a genetic algorithm for tracer design that takes advantage of the precision scoring system in the evaluation of optimal tracers.

Recently, we introduced an alternative approach for tracer selection, which does not rely on trial-and-error strategies for identifying optimal tracers (Crown et al., 2012; Crown and Antoniewicz, 2012). The framework is based on the elementary metabolite units (EMU) framework developed by Antoniewicz et al. (Antoniewicz et al., 2007b). We have demonstrated that every metabolite in a network can be decomposed into a linear combination of so-called EMU basis vectors (EMU-BV), where each EMU-BV represents a unique way of assembling substrate EMU’s into the measured metabolites. The corresponding coefficients quantify the weights of each EMU-BV to the measurement. The methodology decouples the dependencies between isotopic labeling (i.e. EMU-BV’s) and free fluxes (i.e. coefficients) in a network model. To select optimal tracers, we conducted sensitivity analyses on the EMU-BV coefficients with respect to free fluxes. Through efficient grouping of coefficient sensitivities we were able to propose rational selection criteria in a number of example systems. Using this methodology we were able to identify novel tracers that drastically improved flux resolution in comparison to previous studies (Henry and Durocher, 2011). We believe that the EMU-BV method can be valuable for selecting optimal tracers for PLE’s. For example, applying this method in parallel for key fluxes of interest in a model can allow optimal tracers to be tailored for different sections of the system. In the end, detailed flux maps can be determined with high precision by integrating the labeling data from the individual parallel experiments.

5.2. Potential disadvantages of parallel labeling experiments

Despite the many benefits of PLE’s, there are also some potential drawbacks as compared to single tracer experiments. The first and most transparent caveat is the increased amount of time and resources required to conduct PLE’s, given that two or more experiments must be performed in parallel. The total number of parallel experiments will depend on the complexity of the system and the required flux precision, but it is reasonable to expect anywhere from 2 to 6 experiments in parallel. With each additional experiment the cost of the study increases. Furthermore, the amount of time and resources required for sampling, labeling measurements, and data processing also increases with each additional experiment. Ultimately, it is at the researcher’s discretion to decide as to whether the increased flux resolution is worth the additional cost, time and resources required as compared to a single tracer experiment.

Another potential disadvantage of PLE’s is related to inconsistencies that may be observed due to biological variability. Before addressing this aspect, it is important to understand the sources of error in a typical 13C-MFA experiment. In general, the majority of random errors result from metabolite concentration measurements (e.g. HPLC data for calculating external rates) and 13C-labeling measurements (e.g. GC-MS, NMR data). In addition, systematic errors may also be present due to the specific analytical and sampling techniques used, e.g. for culture sampling, cell harvesting, extraction of the metabolites, sample pre-treatment, etc. The flux analysis process inherently assumes that the largest source of error is due to random measurement errors. When experiments are run in parallel, these sources of error are still present; however, there is the additional concern of biological variability. The key question is: is the relative contribution of biological variability to the total error small or large? In cases of simple systems, such as microbial batch or continuous cultures, this may not be a major concern as these experiments are highly reproducible (Leighty and Antoniewicz, 2012). It is expected that the random errors from measurements will remain the dominant source of error. However, for more complex systems, such as mammalian cultures and extended fed-batch fermentations (Ahn and Antoniewicz, 2012; Antoniewicz et al., 2007c), errors due to biological variability may not be negligible. If the experiment-to-experiment errors become the largest contributor to the total error, the benefits of running parallel labeling experiments may be negated. The last potential caveat of PLE’s is whether current 13C-MFA software packages are capable of successfully integrating 13C-labeling data from multiple experiments for comprehensive flux analysis. Without such techniques in place, analyzing and interpreting data from PLE’s may be difficult for laboratories that do not have in-house experience.

Overall, we do not see the disadvantages raised in this section as damning to the PLE methodology. It is important, however, that researchers are aware of these limitations so that proper means of action can be taken to attenuate the potential impact. The increased time and resources required for parallel experiments place an impetus on the development of efficient analytical procedures and cost-effective 13C-tracer selections. In the end, the quality of information accrued from PLE’s is expected to outweigh the cost-benefit compared to a single tracer experiment. Studies focusing on optimizing cell culture performance can also mitigate the effects of biological variability. Lastly, we believe that software limitations for analysis of PLE’s are only a short-term concern, since new algorithms for PLE’s can be relatively easily incorporated into existing programs to allow rigorous and integrated analysis of multiple data sets.

5.3. Future directions

There are several aspects of PLE’s that require additional attention going forward. As we described in this review, when conducting tracer experiments the researcher has control over the choice of isotopic tracers and the measurement set. Unfortunately, there is still little understanding regarding the interplay between the choice of tracer and measurement set. Currently, methods are available where, given a measurement, an optimal tracer can be determined for a set of fluxes of interest (Crown et al., 2012). Similarly, given a tracer, the minimal measurements set can also be determined (Chang et al., 2008). However, the question regarding which tracers and which measurements are optimal for a given network is still considered in isolation, rather than in conjunction with each other. In the case of PLE’s, another level of complexity is added, as the investigator can also control how many experiments are performed in parallel. The interconnections and relationships between the tracer selection, measurement choice, and number of parallel experiments is an important question to address. For example, consider a hypothetical case where several experiments are conducted in parallel, but the flux resolution still needs to be improved. What is the appropriate course of action: should more isotopic measurements be collected? Should an additional experiment be performed in parallel? Should one of the experiments involve a different tracer? Similarly, is it better to have fewer experiments in parallel with plentiful 13C-enrichment measurements, or is it better to have many experiments with more scarce labeling data? These questions highlight the importance of a rational decision-making process when approaching PLE design. Currently, this thought process is still underdeveloped.

To address these issues going forward, an emphasis on efficient methods for optimal tracer selection is essential. Due to the number of variables involved in tracer experiment design, i.e. single or multiple tracer substrates, the composition of tracer mixtures, and number of parallel experiments, the number of possible experiment designs can increase exponentially. Current experiment design methodologies that focus on trial-and-error simulations to determine optimal tracers will be increasingly inefficient for PLE’s due to the near-infinite number of possibilities. A rational and systematic method for approaching tracer selection is therefore needed as a precursor to simulation-based studies. The premise of a rational framework is to efficiently reduce the experiment design space to a feasible and tractable subset, which can then be further evaluated using simulation based approaches. Ideally, the methods should also account for the impact of measurement error and biological variability on the expected outcomes.

6. CONCLUSIONS

In this paper, we have reviewed the use of parallel labeling experiments for metabolism research, both in the context of a historical perspective and current applications in 13C-MFA. Parallel labeling experiments offer significant advantages in comparison to traditional single tracer experiments. However, there are also several challenges that must be addressed for its successful implementation. As we described above, we believe the advantages of parallel labeling experiments will ultimately outweigh the challenges that lie ahead. If anything, the challenges facing parallel labeling experiments should only reinforce the need for careful planning of experiments and development of improved analytical, experimental and computational approaches. Future studies should focus on addressing the issues outlined in this review, as well as identifying additional unforeseen difficulties. In the end, we believe that parallel labeling experiments are a powerful approach for probing metabolism with the potential to become the predominant technique used for high-resolution 13C-MFA.

ABBREVIATIONS

- ED

Entner-Doudoroff

- EMP

Embden-Meyerhof-Parnas

- EMU

elementary metabolite unit

- EMU-BV

elementary metabolite unit basis vector

- GC-MS

gas chromatography-mass spectrometry

- MFA

metabolic flux analysis

- MS

mass spectrometry

- MS/MS

tandem mass spectrometry

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- oxPPP

oxidative pentose phosphate pathway

- PC

pyruvate carboxylase

- PDH

pyruvate dehydrogenase

- PLE

parallel labeling experiment

REFERENCES

- Ahn WS, Antoniewicz MR, 2011. Metabolic flux analysis of CHO cells at growth and non-growth phases using isotopic tracers and mass spectrometry. Metab Eng. 13, 598–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn WS, Antoniewicz MR, 2012. Towards dynamic metabolic flux analysis in CHO cell cultures. Biotechnol J. 7, 61–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn WS, Antoniewicz MR, 2013. Parallel labeling experiments with [1,2–13C]glucose and [U-13C]glutamine provide new insights into CHO cell metabolism. Metab Eng. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2012.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen DK, Ohlrogge JB, Shachar-Hill Y, 2009. The role of light in soybean seed filling metabolism. Plant J. 58, 220–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso AP, Dale VL, Shachar-Hill Y, 2010. Understanding fatty acid synthesis in developing maize embryos using metabolic flux analysis. Metab Eng. 12, 488–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso AP, Raymond P, Hernould M, Rondeau-Mouro C, de Graaf A, Chourey P, Lahaye M, Shachar-Hill Y, Rolin D, Dieuaide-Noubhani M, 2007. A metabolic flux analysis to study the role of sucrose synthase in the regulation of the carbon partitioning in central metabolism in maize root tips. Metab Eng. 9, 419–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso AP, Val DL, Shachar-Hill Y, 2011. Central metabolic fluxes in the endosperm of developing maize seeds and their implications for metabolic engineering. Metabolic Engineering. 13, 96–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amador-Noguez D, Feng XJ, Fan J, Roquet N, Rabitz H, Rabinowitz JD, 2010. Systems-level metabolic flux profiling elucidates a complete, bifurcated tricarboxylic acid cycle in Clostridium acetobutylicum. J Bacteriol. 192, 4452–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson AJ, Dawes EA, 1990. Occurrence, Metabolism, Metabolic Role, and Industrial Uses of Bacterial Polyhydroxyalkanoates. Microbiol Rev. 54, 450–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoniewicz MR, Comprehensive analysis of metabolic pathways through the combined use of multiple isotopic tracers. Ph.D. Thesis. Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Antoniewicz MR, 2013. Tandem mass spectrometry for measuring stable-isotope labeling. Curr Opin Biotechnol. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2012.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoniewicz MR, Kelleher JK, Stephanopoulos G, 2006. Determination of confidence intervals of metabolic fluxes estimated from stable isotope measurements. Metab Eng. 8, 324–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoniewicz MR, Kelleher JK, Stephanopoulos G, 2007a. Accurate assessment of amino acid mass isotopomer distributions for metabolic flux analysis. Anal Chem. 79, 7554–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoniewicz MR, Kelleher JK, Stephanopoulos G, 2007b. Elementary metabolite units (EMU): a novel framework for modeling isotopic distributions. Metab Eng. 9, 68–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoniewicz MR, Kelleher JK, Stephanopoulos G, 2011. Measuring deuterium enrichment of glucose hydrogen atoms by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 83, 3211–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoniewicz MR, Kraynie DF, Laffend LA, Gonzalez-Lergier J, Kelleher JK, Stephanopoulos G, 2007c. Metabolic flux analysis in a nonstationary system: fed-batch fermentation of a high yielding strain of E. coli producing 1,3-propanediol. Metab Eng. 9, 277–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antony GJ, Landau BR, 1968. Relative contributions of alpha-, beta-, and omega-oxidative pathways to in vitro fatty acid oxidation in rat liver. J Lipid Res. 9, 267–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arauzo-Bravo MJ, Shimizu K, 2003. An improved method for statistical analysis of metabolic flux analysis using isotopomer mapping matrices with analytical expressions. J Biotechnol. 105, 117–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker J, Wittmann C, 2012. Bio-based production of chemicals, materials and fuels -Corynebacterium glutamicum as versatile cell factory. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 23, 631–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bederman IR, Dufner DA, Alexander JC, Previs SF, 2006. Novel application of the “doubly labeled” water method: measuring CO2 production and the tissue-specific dynamics of lipid and protein in vivo. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 290, E1048–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bier DM, 1987. The use of stable isotopes in metabolic investigation. Bailliere’s clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 1, 817–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blank LM, Lehmbeck F, Sauer U, 2005. Metabolic-flux and network analysis in fourteen hemiascomycetous yeasts. FEMS Yeast Res. 5, 545–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boghigian BA, Seth G, Kiss R, Pfeifer BA, 2010. Metabolic flux analysis and pharmaceutical production. Metab Eng. 12, 81–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borowitz MJ, Stein RB, Blum JJ, 1977. Quantitative analysis of the change of metabolite fluxes along the pentose phosphate and glycolytic pathways in Tetrahymena in response to carbohydrates. J Biol Chem. 252, 1589–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady PS, Scofield RF, Ohgaku S, Schumann WC, Bartsch GE, Margolis JM, Kumaran K, Horvat A, Mann S, Landau BR, 1982a. Pathways of acetoacetate’s formation in liver and kidney. J Biol Chem. 257, 9290–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady PS, Scofield RF, Schumann WC, Ohgaku S, Kumaran K, Margolis JM, Landau BR, 1982b. The tracing of the pathway of mevalonate’s metabolism to other than sterols. J Biol Chem. 257, 10742–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GW Jr., Katz J, Chaikoff IL, 1956. The oxidative metabolic pattern of mouse hepatoma C954 as studied with C14-labeled acetates, propionate, octanoate, and glucose. Cancer Res. 16, 509–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunengraber DZ, McCabe BJ, Katanik J, Previs SF, 2002. Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry assay of the (18)o enrichment of water as trimethyl phosphate. Anal Biochem. 306, 278–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess SC, Weis B, Jones JG, Smith E, Merritt ME, Margolis D, Dean Sherry A, Malloy CR, 2003. Noninvasive evaluation of liver metabolism by 2H and 13C NMR isotopomer analysis of human urine. Anal Biochem. 312, 228–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chance EM, Seeholzer SH, Kobayashi K, Williamson JR, 1983. Mathematical analysis of isotope labeling in the citric acid cycle with applications to 13C NMR studies in perfused rat hearts. J Biol Chem. 258, 13785–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandramouli V, Ekberg K, Schumann WC, Kalhan SC, Wahren J, Landau BR, 1997. Quantifying gluconeogenesis during fasting. Am J Physiol. 273, E1209–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y, Suthers PF, Maranas CD, 2008. Identification of optimal measurement sets for complete flux elucidation in metabolic flux analysis experiments. Biotechnol Bioeng. 100, 1039–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevalier S, Burgess SC, Malloy CR, Gougeon R, Marliss EB, Morais JA, 2006. The greater contribution of gluconeogenesis to glucose production in obesity is related to increased whole-body protein catabolism. Diabetes. 55, 675–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J, Antoniewicz MR, 2011. Tandem mass spectrometry: a novel approach for metabolic flux analysis. Metab Eng. 13, 225–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J, Grossbach MT, Antoniewicz MR, 2012. Measuring complete isotopomer distribution of aspartate using gas chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 84, 4628–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen B, Nielsen J, 1999. Isotopomer analysis using GC-MS. Metab Eng. 1, 282–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen SM, 1983. Simultaneous 13C and 31P NMR studies of perfused rat liver. Effects of insulin and glucagon and a 13C NMR assay of free Mg2+. J Biol Chem. 258, 14294–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen SM, Rognstad R, Shulman RG, Katz J, 1981. A comparison of 13C nuclear magnetic resonance and 14C tracer studies of hepatic metabolism. J Biol Chem. 256, 3428–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comte B, Vincent G, Bouchard B, Des Rosiers C, 1997a. Probing the origin of acetyl-CoA and oxaloacetate entering the citric acid cycle from the 13C labeling of citrate released by perfused rat hearts. J Biol Chem. 272, 26117–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comte B, Vincent G, Bouchard B, Jette M, Cordeau S, Rosiers CD, 1997b. A 13C mass isotopomer study of anaplerotic pyruvate carboxylation in perfused rat hearts. J Biol Chem. 272, 26125–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crown SB, Ahn WS, Antoniewicz MR, 2012. Rational design of 13C-labeling experiments for metabolic flux analysis in mammalian cells. BMC Syst Biol. 6, 43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crown SB, Antoniewicz MR, 2012. Selection of tracers for 13C-metabolic flux analysis using elementary metabolite units (EMU) basis vector methodology. Metab Eng. 14, 150–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crown SB, Indurthi DC, Ahn WS, Choi J, Papoutsakis ET, Antoniewicz MR, 2011. Resolving the TCA cycle and pentose-phosphate pathway of Clostridium acetobutylicum ATCC 824: Isotopomer analysis, in vitro activities and expression analysis. Biotechnol J. 6, 300–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Adamo A Jr., Haft DE, 1965. An Alternate Pathway of Alpha-Ketoglutarate Catabolism in the Isolated, Perfused Rat Liver. I. Studies with Dl-Glutamate-2- and −5–14c. J Biol Chem. 240, 613–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauner M, Sauer U, 2000. GC-MS analysis of amino acids rapidly provides rich information for isotopomer balancing. Biotechnology progress. 16, 642–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Graaf AA, Venema K, 2008. Gaining insight into microbial physiology in the large intestine: a special role for stable isotopes. Advances in microbial physiology. 53, 73–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong B, Siewers V, Nielsen J, 2012. Systems biology of yeast: enabling technology for development of cell factories for production of advanced biofuels. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 23, 624–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBerardinis RJ, Lum JJ, Hatzivassiliou G, Thompson CB, 2008. The biology of cancer: metabolic reprogramming fuels cell growth and proliferation. Cell Metab. 7, 11–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Des Rosiers C, Fernandez CA, David F, Brunengraber H, 1994. Reversibility of the mitochondrial isocitrate dehydrogenase reaction in the perfused rat liver. Evidence from isotopomer analysis of citric acid cycle intermediates. J Biol Chem. 269, 27179–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Des Rosiers C, Lloyd S, Comte B, Chatham JC, 2004. A critical perspective of the use of (13)C-isotopomer analysis by GCMS and NMR as applied to cardiac metabolism. Metab Eng. 6, 44–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewick PM, 1995. The Biosynthesis of Shikimate Metabolites. Natural Product Reports. 12, 579–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Donato L, Des Rosiers C, Montgomery JA, David F, Garneau M, Brunengraber H, 1993. Rates of gluconeogenesis and citric acid cycle in perfused livers, assessed from the mass spectrometric assay of the 13C labeling pattern of glutamate. J Biol Chem. 268, 4170–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmond J, Popjak G, 1974. Transfer of carbon atoms from mevalonate to n-fatty acids. J Biol Chem. 249, 66–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng X, Mouttaki H, Lin L, Huang R, Wu B, Hemme CL, He Z, Zhang B, Hicks LM, Xu J, Zhou J, Tang YJ, 2009. Characterization of the central metabolic pathways in Thermoanaerobacter sp. strain X514 via isotopomer-assisted metabolite analysis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 75, 5001–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer E, Sauer U, 2003. Metabolic flux profiling of Escherichia coli mutants in central carbon metabolism using GC-MS. Eur J Biochem. 270, 880–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer E, Zamboni N, Sauer U, 2004. High-throughput metabolic flux analysis based on gas chromatography-mass spectrometry derived 13C constraints. Anal Biochem. 325, 308–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Follstad BD, Stephanopoulos G, 1998. Effect of reversible reactions on isotope label redistribution--analysis of the pentose phosphate pathway. Eur J Biochem. 252, 360–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuhrer T, Fischer E, Sauer U, 2005. Experimental identification and quantification of glucose metabolism in seven bacterial species. J Bacteriol. 187, 1581–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia DE, Baidoo EE, Benke PI, Pingitore F, Tang YJ, Villa S, Keasling JD, 2008. Separation and mass spectrometry in microbial metabolomics. Current opinion in microbiology. 11, 233–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goebel R, Berman M, Foster D, 1982. Mathematical model for the distribution of isotopic carbon atoms through the tricarboxylic acid cycle. Fed Proc. 41, 96–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry O, Durocher Y, 2011. Enhanced glycoprotein production in HEK-293 cells expressing pyruvate carboxylase. Metab Eng. 13, 499–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hevesy G, 1923. The Absorption and Translocation of Lead by Plants: A Contribution to the Application of the Method of Radioactive Indicators in the Investigation of the Change of Substance in Plants. The Biochemical journal. 17, 439–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horecker BL, Gibbs M, Klenow H, Smyrniotis PZ, 1954. The mechanism of pentose phosphate conversion to hexose monophosphate. I. With a liver enzyme preparation. J Biol Chem. 207, 393–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hostetler KY, Williams HR, Shreeve WW, Landau BR, 1969. Conversion of specifically 14 C-labeled lactate and pyruvate to glucose in man. J Biol Chem. 244, 2075–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwatani S, Yamada Y, Usuda Y, 2008. Metabolic flux analysis in biotechnology processes. Biotechnol Lett. 30, 791–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffrey FM, Rajagopal A, Malloy CR, Sherry AD, 1991. 13C-NMR: a simple yet comprehensive method for analysis of intermediary metabolism. Trends Biochem Sci. 16, 5–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffrey FM, Roach JS, Storey CJ, Sherry AD, Malloy CR, 2002. 13C isotopomer analysis of glutamate by tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Biochem. 300, 192–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen MD, Chandramouli V, Schumann WC, Ekberg K, Previs SF, Gupta S, Landau BR, 2001a. Sources of blood glycerol during fasting. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 281, E998–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen MD, Ekberg K, Landau BR, 2001b. Lipid metabolism during fasting. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 281, E789–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen MV, Joseph JW, Ronnebaum SM, Burgess SC, Sherry AD, Newgard CB, 2008. Metabolic cycling in control of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 295, E1287–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin ES, Burgess SC, Merritt ME, Sherry AD, Malloy CR, 2005. Differing mechanisms of hepatic glucose overproduction in triiodothyronine-treated rats vs. Zucker diabetic fatty rats by NMR analysis of plasma glucose. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 288, E654–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones JG, Sherry AD, Jeffrey FM, Storey CJ, Malloy CR, 1993. Sources of acetyl-CoA entering the tricarboxylic acid cycle as determined by analysis of succinate 13C isotopomers. Biochemistry. 32, 12240–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones JG, Solomon MA, Cole SM, Sherry AD, Malloy CR, 2001. An integrated (2)H and (13)C NMR study of gluconeogenesis and TCA cycle flux in humans. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 281, E848–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kam W, Kumaran K, Landau BR, 1978. Contribution of omega-oxidation to fatty acid oxidation by liver of rat and monkey. J Lipid Res. 19, 591–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz J, Landau BR, Bartsch GE, 1966. The pentose cycle, triose phosphate isomerization, and lipogenesis in rat adipose tissue. J Biol Chem. 241, 727–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz J, Rognstad R, 1966. The metabolism of tritiated glucose by rat adipose tissue. J Biol Chem. 241, 3600–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz J, Rognstad R, 1969. The metabolism of glucose-2-T by adipose tissue. J Biol Chem. 244, 99–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz J, Wals P, Lee WN, 1993. Isotopomer studies of gluconeogenesis and the Krebs cycle with 13C-labeled lactate. J Biol Chem. 268, 25509–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz J, Wood HG, 1960. The use of glucose-C14 for the evaluation of the pathways of glucose metabolism. J Biol Chem. 235, 2165–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz J, Wood HG, 1963. The use of C14O2 yields from glucose-1- and −6-C14 for the evaluation of the pathways of glucose metabolism. J Biol Chem. 238, 517–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelleher JK, 1985. Analysis of tricarboxylic acid cycle using [14C]citrate specific activity ratios. Am J Physiol. 248, E252–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelleher JK, 2001. Flux estimation using isotopic tracers: common ground for metabolic physiology and metabolic engineering. Metab Eng. 3, 100–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelleher JK, 2004. Probing metabolic pathways with isotopic tracers: insights from mammalian metabolic physiology. Metab Eng. 6, 1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelleher JK, Bryan BM 3rd, 1985. A 14CO2 ratios method for detecting pyruvate carboxylation. Anal Biochem. 151, 55–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelleher JK, Kharroubi AT, Aldaghlas TA, Shambat IB, Kennedy KA, Holleran AL, Masterson TM, 1994. Isotopomer spectral analysis of cholesterol synthesis: applications in human hepatoma cells. Am J Physiol. 266, E384–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kharroubi AT, Masterson TM, Aldaghlas TA, Kennedy KA, Kelleher JK, 1992. Isotopomer spectral analysis of triglyceride fatty acid synthesis in 3T3-L1 cells. Am J Physiol. 263, E667–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiefer P, Heinzle E, Zelder O, Wittmann C, 2004. Comparative metabolic flux analysis of lysine-producing Corynebacterium glutamicum cultured on glucose or fructose. Appl Environ Microbiol. 70, 229–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim TY, Sohn SB, Kim YB, Kim WJ, Lee SY, 2012. Recent advances in reconstruction and applications of genome-scale metabolic models. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 23, 617–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein S, Heinzle E, 2012. Isotope labeling experiments in metabolomics and fluxomics. Wiley interdisciplinary reviews. Systems biology and medicine. 4, 261–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler RE, 1977. Rudolf Schoenheimer, isotopic tracers, and biochemistry in the 1930’s. Hist Studies Phys Sci. 8, 257–298. [Google Scholar]

- Kruger NJ, Masakapalli SK, Ratcliffe RG, 2012. Strategies for investigating the plant metabolic network with steady-state metabolic flux analysis: lessons from an Arabidopsis cell culture and other systems. J Exp Bot. 63, 2309–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landau BR, Ashmore J, Hastings AB, Zottu S, 1960. Studies on carbohydrate metabolism in rat liver slices. XV. Pyruvate and propionate metabolism and carbon dioxide fixaction in rat liver slices in vitro. J Biol Chem. 235, 1856–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landau BR, Bartsch GE, 1966. Estimations of pathway contributions to glucose metabolism and the transaldolase reactions. J Biol Chem. 241, 741–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landau BR, Bartsch GE, Katz J, Wood HG, 1964. Estimation of Pathway Contributions to Glucose Metabolism and of the Rate of Isomerization of Hexose 6-Phosphate. J Biol Chem. 239, 686–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JW, Na D, Park JM, Lee J, Choi S, Lee SY, 2012. Systems metabolic engineering of microorganisms for natural and non-natural chemicals. Nat Chem Biol. 8, 536–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leighty RW, Antoniewicz MR, 2011. Dynamic metabolic flux analysis (DMFA): a framework for determining fluxes at metabolic non-steady state. Metab Eng. 13, 745–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leighty RW, Antoniewicz MR, 2012. Parallel labeling experiments with [U-(13)C]glucose validate E. coli metabolic network model for (13)C metabolic flux analysis. Metab Eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malloy CR, Sherry AD, Jeffrey FM, 1988. Evaluation of carbon flux and substrate selection through alternate pathways involving the citric acid cycle of the heart by 13C NMR spectroscopy. J Biol Chem. 263, 6964–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malloy CR, Sherry AD, Jeffrey FM, 1990a. Analysis of tricarboxylic acid cycle of the heart using 13C isotope isomers. Am J Physiol. 259, H987–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malloy CR, Thompson JR, Jeffrey FM, Sherry AD, 1990b. Contribution of exogenous substrates to acetyl coenzyme A: measurement by 13C NMR under non-steady-state conditions. Biochemistry. 29, 6756–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsolais C, Huot S, David F, Garneau M, Brunengraber H, 1987. Compartmentation of 14CO2 in the perfused rat liver. J Biol Chem. 262, 2604–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews DE, Bier DM, 1983. Stable isotope methods for nutritional investigation. Annual review of nutrition. 3, 309–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]