Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to highlight the use of induced affect (IA) and collaborative (therapeutic) assessment (CA) as components of Cognitive-Affective Stress Management Training (CASMT). IA is a technique for rehearsing cognitive and physical relaxationcoping skills under conditions of high affective arousal, which has been shown to result in high levels of coping self-efficacy. CA provides diary-based feedback to clients about the processes underlying theirstress experiences and helps identify affect-arousing experiences to be targeted by IA. We include descriptions of the IA technique and anonline stress and coping daily diary, as well as sample transcripts illustrating how CA is integrated into CASMT and how IA evokes high affective arousal and skills rehearsal. To illustrate idiographic assessment, we also describe threetreatment cases involving female clients between the ages of 20 and 35 with anxiety symptoms who participated in six weeks of CASMT and reported their daily stress and coping experiences (before, during, and following the intervention)for a total of ten weeks. The resulting time series data, analyzed using Simulation Modeling Analysis (SMA), revealed that all clients reported improved negative affect regulation over the course of treatment, yet they exhibited idiographic patterns of change on other outcome and coping skills variables. These results illustrate how IA and CA may be used to enhance emotional self-regulation and how time-series analyses can identify idiographic aspects of treatment response that would not be evident in group data.

Keywords: affect elicitation, coping skills rehearsal, collaborative assessment, stress management

Stress Management Skills Training Addresses a Public Health Need

A nationwide survey commissioned by the American Psychological Association, Stress in America: Missing the Health Care Connection, (APA, 2013), reported that 1 in 5 adults reported stress levels of 8, 9, or 10 (on a 10-point scale), frequently accompanied by physical and psychological symptoms. More than half reported they did not receive needed support around stress management from their health care provider. Failure to cope successfully with stressful life events takes a significant toll on people’s physical, social, and psychological well-being. Stressful life events, negative emotional responses to them, and failure to cope effectively are prime components or causal factors in a wide range of illnesses and psychological disorders (Gouin, 2011; Folkman, 2011). Individuals who struggle with stress management are at risk for developing more severe disorders. A daily diary study with a nonclinical sample revealed that high levels of daily negative affect and affective reactivity to stressors predicted self-reported anxiety and depressive disorders 10 years later (Charles, Piazza, Mogle, Sliwinski, & Almeida, 2013). We believe stress management is a worthy area of involvement for mental health professionals given its importance tophysical and psychological wellbeing and the documented gap between need and service provision (APA, 2013).

In a discussion of emerging public health needs, Kazdin and Blase (2011) calledfor brief, effective interventions using evidence-based principles that can be widely administered to individuals and groups. Such interventions are consistent with current NIMH priorities that emphasize targeting specific mechanisms of psychological disorders in such a way that derivative treatments can be disseminated at a population level as part of a stepped care system, in either a clinical context or in an educational or group format (Onken, Carroll, Shoham, Cuthbert, & Riddle, 2014;Cuthbert &Insel, 2013). Coping skills training, central to many cognitive behavioral therapies (CBTs) (e.g.,Ehrenreich, Fairholme, Buzzella, Ellard, & Barlow, 2007; Linehan, 2015;Martell, Addis, & Jacobson, 2001; Meichenbaum & Novaco, 1985), has been shown to be effective at targeting specific mechanisms of psychological disorders, such as emotion dysregulation (Neacsiu, Lungu, Harned, Rizvi, & Linehan, 2014). Coping skills training in stress management may be an excellent candidate for stepped care treatment, particularly in the prevention of anxiety, mood, and other psychological disorders. We next describe one such coping skills training program: Cognitive-Affective Stress Management Training.

Cognitive-Affective Stress Management Training

Cognitive-Affective Stress Management Training (CASMT; Smith, 1980; Smith & Ascough, in press) is a cognitive behavioral coping skills intervention with empirical support for use with a wide variety of populations (Crocker, 1989; Jacobs, Smith, Fiedler, & Link, 2012; Rohsenow, Smith, & Johnson, 1985; Shoda, Wilson, Chen, Gilmore, & Smith, 2013; Smith & Ascough, 1984; Smith & Nye, 1989; Smith et al., 2011; Ziegler, Klinzing, & Williamson, 1982). The target population is individuals who seek help for high levels of life stress, whether or not they currently warrant a formal DSM diagnosis. It is an intervention directed at arousal-oriented issues, such as anxiety and anger. With regards to depression, which is correlated with stress, CASMT could be used within a multi-component treatment plan to address arousal-producing aspects of a client’s depression. For instance, clients with externalizing forms of depression tend to experience considerable irritability and anger as they blame external sources for their distress (Nicholls, 2011). Likewise, many depressed clients have co-occurring anxiety that could be targetedbyCASMT’s arousal regulation techniques.

CASMT is a six-session intervention consisting of a coping skills acquisition phase (Sessions 1 and 2) and a skills rehearsal phase (Sessions 3 through 6). Each session is one-hour long and the sessions are typically scheduled weekly, though they can be heldtwice per week. CASMT is derived from a coping skills model of emotion regulation (Smith, 1980; Smith & Ascough, 1984, in press), based on the assumption that successful control of high levels of arousal not only generalizes to less demanding stressors, but also enhances coping self-efficacy (i.e., “If I can handle that, I certainly can handle the less arousing challenges outside of treatment”).

Skills Acquisition(Sessions 1 and 2)

In session 1, clients are introduced to CASMT’s conceptual model of stress. CASMT utilizesa mediational model of stress in which the effect of a given situation (stressor) on emotion and behavior is mediated by both cognitive appraisals (thoughts) and physiological responses (see Figure 1). CASMT targets physiological stress responses by teaching cue-enhanced muscle relaxation (beginning in Session 1), wherein a “key word” chosen by the client (such as “relax”) is repeatedly paired with exhalation and muscle relaxation. CASMT targets stress-producing cognitive appraisals through cognitive restructuring and self-instructional training (beginning in Session 2), with a special focus on countering catastrophizing, asresearch has shownthat catastrophizing cognitions activate brain regions involved in negative affect (Kalisch & Gerlicher, 2014). Clients are told that between-session skills practice is essential for skill mastery. Using an online stress and coping daily diary, clients monitor stressful situations, coping skills use, and automatic thoughts. Client use the daily diary to generate alternative, stress-reducing self-statements between sessions, much like a thought record. In-session reviewsof the diary responses allow therapists to evaluate the quality of clients’ reappraisal statements and troubleshoot as necessary. Sessions 1 and 2 form an introduction to these skills, whilelater sessions continue to build mastery throughskills rehearsal.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model and interventions. (Smith, 2012)

In-Session Skills Rehearsal (Sessions 3–6)

The goal of the skills rehearsal phase is to use induced affect (IA; described below) to help clients rehearse their relaxation and cognitive skills in-sessionunder conditions of high affective arousal. In-session skills rehearsal also provides therapists an opportunity to see their clients apply skills in vivo and confirmthat theyare capable of reducing IA-elicited arousal, thereby checking skills mastery. In Session 3, as the therapist induces high levels of affective arousal related to stressful experiences, clients practice “turning off” their arousal with physical relaxation skills and with an integrated coping response that ties relaxation and cognitive skills into the breath cycle (Smith, 1980; Figure 2). In the integrated coping response, the client emits a previously selected stress-reducing self-statement (e.g., “I may not like this, but I can definitely stand it”) while inhaling. As the client exhales, cue-enhanced relaxation is appliedto reduce arousal.

Figure 2.

Examples of the integrated coping response. (Smith, 2012)

Induced affect and rehearsal of the integrated coping response continue through the final session. Self-statements used in the integrative coping response are derived from either cognitive restructuring (Beck, 1976; Ellis, 1962) or self-instructional training (Meichenbaum, 1985). During the skills rehearsal phase, therapists help clients hone their self-statements and further refine their cognitive restructuring skills.

In sessions 4 and 5, clients are also introduced to and practice Benson meditation and mindfulness techniques (e.g., observing thoughts and sensations in a nonjudgmental fashion) as general stress reduction skills. Clients are sent home with handouts detailing further resources about mindfulness and meditation, as well as self-administered desensitization, to inform them of skills that would be possible to learn beyond what was taught in the program. The final session of CASMT is used for review and relapse prevention.

Self-Administered Training Modules

In addition to the in-session training component, CASMT involves extensive, self-directed daily homework assignments that extend over the six weeks of treatment. For each of the coping skills (paced breathing, physical relaxation, cognitive restructuring, self-instructional training), clients receive an instructional module that contains the intervention rationale, the mechanics of the coping skill (i.e., how to do it), and structured and graduated training activities. Although skills training and didactics are done within treatment sessions, consistent between-session practice, guided by the modules, is necessary formastery of coping skills. We have found that for most clients, sevendays of daily practice is sufficient to develop a strong physical relaxation response. Additionally, it should be noted that our cognitive module focuses primarily on countering catastrophizing thoughts rather than reprograming core beliefs, as a more extensive and time-intensive cognitive therapy would do. In our use of self-instructional materials that supplement and extend what clients learn in-session, we build on empiricalevidence that bibliotherapeutic self-help resources can be highly efficacious, including those that focus on more complex skills such as cognitive restructuring(Edenfield & Saeed, 2012; Furmark, Carlbring, Hedman, & Sonnenstein, 2009; Gregory, Schwer Canning, Lee, & Wise, 2004; Schelver & Gutsch, 1983).

Induced Affect: Enhancing Skills Training Through Affect Elicitation and Skills Rehearsal

Even if clients acquire coping skills knowledge, this does not necessarily translate into effective skills utilization (Meuret, Wolitzky-Taylor, Twohig, & Craske, 2012). Effective skills utilization must be situationally or contextually appropriate (Cheng, Lau, & Chan, 2014) and likely depends upon repeated skills practice (Kazdin & Mascitelli, 1982; Meichenbaum, 1977) in situations that mimic or include real-life conditions of stress.

One intervention that supports successful coping skills utilization is the rehearsal of skills under conditions of high arousal (Smith & Nye, 1989). Induced affect (IA, originally called induced anxiety; Sipprelle, 1967) provides for coping skills rehearsal under high levels of affective arousal, with the goal of increasingthe client’s self-regulatory abilities and enhancing coping self-efficacy (Bandura, 1997). IA is an operant conditioning method developedby Sipprelle (1967) to elicit affective arousal and facilitate awareness of thoughts, memories, and behaviors that are functionally related to the client’s presenting problem (Smith & Ascough, 1984, in press). While IA resembles traditional imaginal and in vivo exposure in that both activate fear networks, IA differs from traditional exposure in that exposure is based on an extinction or inhibitory learning model. IA is based on a self-regulation model wherein change in behavior and emotions is mediated by mastery of coping skills and increased self-efficacy. In one comparative study, test anxious college students who rehearsed coping skills under IA showed greater performance improvement on tests and higher coping self-efficacy than did students who rehearsed skills under covert (imaginal) rehearsal without affective arousal (Smith & Nye, 1989).

IA consists of three components: increased affective arousal, skills rehearsal, and discussion or processing of the experience.

Arousal Phase

In IA, the therapist elicits affective arousal from the client through instruction, suggestion, encouragement, and positive verbal reinforcement of affective behaviors. Typically, IA begins with an initial relaxation phase designed to produce a low baseline level of arousal. Then the client closes his or her eyes and either vividly imagines a recent stressful situation, or the process may begin by simply asking the client to turn his or her attention deep inside where unspecified feelings reside. The client focuses on whatever feelings arise and is told to let them grow “stronger and stronger.” The therapist gives specific verbal reinforcement, such as “that’s good” or “that’s right, let them come to the surface,” when signs of affective arousal occur, which could include changes in facial expression, physiological arousal (e.g., hands shaking, shortening of breath), or expressions of emotion (e.g., tears). The client is prompted to report feelings and associated physical sensations, memories, images, and thoughts as they arise. As arousal increases, the therapist may reinforce and increase affective arousal by reflecting back the client’s statements, such as “your stomach is clenching as the feeling grows stronger.” The goal of the arousal phase of IA, which usually lasts 6 to 10 minutes, is to have the client access affective experiences and associated cognitions that are either over-experienced or routinely avoided in daily life (Smith & Ascough, 1984).

Skills Rehearsal (Arousal Reduction) Phase

After affective arousal is attained and it is clear that the client is engaged with relevant thoughts and images, the therapist instructs the client to “turn off” his or her arousal using a coping skill that the therapist and client have identified prior to the IA procedure, and one that the client has sufficiently mastered so that it can be effectively applied to dampen arousal. Traditionally, physical relaxation techniques are used first for “turning off” the client’s arousal, followed by stress-reducing self-statements and self-instructions as part of the integrated coping response.

Discussion Phase

The goal of the discussion phase is to explore the client’s experience of IA and to help the client identify relations between situations, appraisals, emotional responses, coping strategies, and consequences. In recent years, the Cognitive-Affective Processing System (CAPS; Mischel & Shoda, 1995), which posits associative links between construals (appraisals), affect, expectancies, goals, and self-regulatory competencies, has been used as a theoretical template for CASMT (Shoda et al., 2013; Smith et al., 2011). As in other neoassociative models (e.g., Berkowitz, 1990; Bower, 1981), affective arousal is viewed as a useful entry point into the client’s associative network, providing a means to access thoughts, memories, and motives that are relevant to the client’s issues.

IA and Skills Generalization

IA is designed to promote generalization of coping skills to out-of-therapy contexts. One way in which this is accomplished is by integrating cues from real-life stressors into the instructions and suggestions provided during the arousal phase. In our current research protocol, all clients complete a daily stress and coping diary (described below), which includes qualitative, open-ended questions about the stressors encountered in daily life. The material from these daily diaries can be usedincollaboration with the client to choose a situation for inducing IA. Additionally, the therapist may use details about the environmental cues, thoughts, and/or sensations that evoke negative emotions to increase the client’s affective engagement in session. Rehearsing adaptive coping skills in response to stress-eliciting cues makes these skills more salient and accessible out-of-session in the client’s daily life (Ehrenreich, et al., 2007). In comparing IA with systematic desensitization, Boer (1970) and Sipprelle (1981) suggest that Wolpe’s (1958) method of systematic desensitization deconditions anxiety responses to external cues in the absence of affective arousal, while IA involves learning self-regulation in response to internal affective cues, presumably leading to greater generalization of skills not only across situations, but also across affective states. In support of this hypothesis, Boer (1970) found that, compared with previous systematic desensitization treatment, exposure to IA was associated with significantly less physiological arousal in response to an unrelated laboratory stressor (e.g. a gory film).

Collaborative Assessment Using an Online Stress and Coping Diary

To accurately evaluate the effectiveness of skills training, Meuret and colleagues (2012) recommend assessing skills utilization as it occurs to minimize the effects of retrospective bias, responder bias, and demand characteristics. Additionally, mere self-monitoring of specific behaviors (e.g., smoking, food intake) may induce behavior change (e.g., Abrams & Wilson, 1979; Burke, Wang, & Sevick, 2011; Klein, Skinner, & Hawley, 2013). Accordingly, ongoing (i.e., repeated) collaborative assessment (CA) may be a valuable framework for assessing and promoting skills utilization. In CA, the client is actively involved in shaping the assessment goals and outcomes. Ongoing CA provides feedback about skills acquisition, retention, and real-life utilization to both therapist and client, allowing them to collaborate on treatment planning and goal-setting (Fischer & Finn, 2008).

In our research program, clientscomplete daily assessments of stress and coping using an online daily diary based on the CASMT stress model and the CAPS model advanced by Mischel and Shoda (1995). The daily diary provides information about each client’s unique associations between situational features, cognitive appraisals, affective responses, coping strategies, self-regulatory skills, and environmental consequences. In the daily diary, clients report descriptions of stressful events and the automatic thoughts that may have led to their emotional reaction; they generate alternative thoughts that could have changed their emotional reaction; and they report their use of various coping behaviors (e.g., relaxation, rethinking the situation, acceptance, seeking social support) in response to stressful situations. In this way, the daily diary also takes the place of traditional paper-and-pencil stress logs or thought records. Further detailsabout the online diary program and its use in CASMT have been published elsewhere (Shoda et al., 2013; Smith et al., 2011).

Online daily assessment provides many benefits. From a research perspective, a primary benefit is the ability to assess within-person, rather than mean-level, processes in relation to daily fluctuations in symptoms and stressors (Almeida, 2005; Bolger, Davis, & Rafaeli, 2003). Additionally, daily assessmentsof coping behavior have been shown to provide more reliable and valid datathan retrospective reports (Ptacek, Smith, Espe, & Raffety, 1994; Smith, Leffingwell, & Ptacek, 1999; Todd, Tennen, Carney, Armeli, & Affleck, 2004).

In clinical settings, daily diaries allow for systematic evaluation of client progress and collaborative discussion of the assessment data; such collaborative assessment has been associated with improved therapeutic outcome (Lambert, 2010; Poston & Hanson, 2010). In addition to symptom monitoring, therapists may use the daily diaries to guide and enhance in-session therapeutic procedures. During IA, for example, therapists may use the clients’ own words and descriptions from the diaries to enhance emotional engagement. The therapist might repeat the client’s negative automatic thoughts, as reported in the diary, to elicit emotions the client experienced during the stressful situation.

Finally, there is preliminary evidence that, in some instances, online diaries may in and of themselves have reactive effects, meaning that diary completion is associated with a change in the behavior being monitored (Glick, Winer, & Golden, 2013; Newcomb & Mustanski, 2014; Rowan, Cofta-Woerpel, Mazas, Vidrine, Reitzel, et al., 2007). Recent findings suggest that the use of the diary can enhance the CASMT intervention, perhaps by increasing self-knowledge or engagement in the training process. In a clinical trial on CASMT, a correlation of .52 was found between number of diary entries made by clients and self-reported stress reduction over a six-week period (Chen, 2015). However, other studieshave found that reactivity associated with frequent monitoring is negligible, particularly in the area of pain research (Aaron, Turner, Mancl, Brister, & Sawchuk, 2005; Stone, Broderick, Schwartz, Shiffman, Litcher-Kelly, et al., 2003) and when the monitoring period is relatively brief (e.g., two weeks; Hufford, Shields, Shiffman, Paty, & Balabanis, 2002). Thus, at this point, the factors that determine degree of efficacy have not been identified. Although we cannot address the potential effect of our online daily diary separate from CASMT and IA, there is preliminary evidence that the diary may enhance the effects of CASMT and it is possible that the diary, on its own, may havetherapeutic effects.

Sample Collaborative Assessment Transcript

The following transcript, adapted for confidentiality reasons, provides an illustration of how a daily diary can be usedwithin a CASMT session to collaboratively discuss the client’s progress and to identify a stressful situation in which the client would benefit from additional skills rehearsal. The client is a 33-year-old woman who initially sought treatment because of work-related stress. She also complained of relationship problems with men, describing a series of failed relationships, some of which she terminated because “I doubted that they really cared about me” and some in which she was rejected and abandoned. The client had a childhood history of sexual abuseperpetrated by her father and reported generalized difficulty with trust and intimacy while at the same time desiring closer relationships.

T: I know that you’ve been working hard at practicing your relaxation and rethinking skills between-sessions. Are you noticing a difference in your ability to cope?

C: Yeah, I think so. I’ve noticed that things that used to really get to me…well, they still bother me at first, but I’m able to calm down and stay focused on what I’m doing.

T: Like what sort of things?

C: Well, at work, if a customer gets angry and blames me for something that’s not my fault…that used to really upset me. I would feel guilty and angry…it would ruin the rest of my day. Something similar happened this past week, but when I noticed how upset I was getting, I took some slow, deep breaths before speaking to my manager. Then I told myself, “I can’t worry about other people’s problems.” I felt a lot better.

T: That’s great! I noticed in your diary entries that you’re using coping skills in the moment as soon as you encounter a stressful situation. It sounds exactly like what you’re saying – you still have stressors in your life, but you can manage them better now, in a way that keeps your emotions from boiling over and affecting a lot of other parts of your life…Actually, can I show you a graph that illustrates what I’m talking about?

C: OK.

T: [logs into diary website and turns computer to client] This is one of the graphs I was looking at before you came into today’s session. This graph shows your use of relaxation and rethinking skills since the beginning of the program. What do you see?

C: The lines go up and down depending on the day.

T: What else?

C: Well, I almost never used rethinking skills at the beginning. Now I’m using both relaxation and rethinking skills a lot more than I used to.

T: Yes! Now I want to show you another graph. [Switches graph view] This graph shows your rating of how helpful these two skills have been.

C: Wow, that has definitely changed! When you first taught me the rethinking skills I had a hard time figuring out how it would be useful. I’ve gotten a lot better at finding more balanced thoughts. I can also tell myself to refocus my attention on what’s important, like the situation I described at work.

T: Exactly! So, you’ve been using these coping skills more over the past three or four weeks, and you’ve been finding them more effective. OK, I want to show you one more thing. [Adds variables to the graph] I added to the graph what you said your stress levels were before and after using your coping skills. What do you see?

C: Well, it still varies day to day, but in general they’ve both gone down.

T: Yes they have, and the thing I notice most is the difference between your stress level when the event occurs and your stress level after using coping skills. This difference has gotten bigger. So, I think this is what we’ve been saying: you’re still encountering stressful situations, but when you use your coping skills, they’re working a lot better and your stress level goes down more. You can see your stress level after coping has been going down at the same time that your coping skills are getting more effective.

C: Yeah, thisreally makes sense to me.

T: Hmm…when I was looking at your data from this past week I wondered what happened last Tuesday because your stress level after using coping skills was still pretty high.

C: Last Tuesday? I don’t remember what was particularly stressful about that day…

Sample IA Transcript: Coping Skills Rehearsal

The following is a continuation of the adapted CASMT session with the 33-year-old female client. The therapist begins IA once he believesthe client’s coping responses are sufficiently well developed to control the emotional arousal elicited by the procedure.

T: Let’s see… you wrote in your diary last Tuesday that you went out with Tom again. Does that jog your memory?

C: [sighs] Oh yeah…we get along really well and I’m attracted to him. I think maybe this could be the real thing. But when he said he really likes me, I started having mixed feelings. Now that you mention it…I remember I couldn’t sleep that night. Actually, just remembering what Tom said that evening is making me feel confused…and torn.

T: What are you confused andtorn about?

C: Well, on the one hand, I was excited that he was feeling like I’m starting to feel…I want to get close to him. But it also scared me. It was like alarm bells went off. Like I’ve had in the past: can I trust him? Does he really care?That feeling is scary for me, and I know it makes me want to run away.

T: Let’s take a closer look at that feeling and try to practice handling that feeling with the skills you’ve learned. We’ll do the induced affect procedure again using this situation with Tom last Tuesday. Go ahead and sit back in your chair and we’ll get you relaxed. And then I’ll help you get in touch with that feeling. OK? [Client nods]

[T induces cue-enhanced relaxation using the abdominal breathing and whole body muscle-tension and release, with the subvocal mental command “relax” emitted by the client with each exhalation.]

T: Now, can you choose analternative thought that could counter that scared feeling that you have about trusting Tom?

C: (long pause) You know, I can think of two. One is “What’s past is past, and not the present or future.” The other is that “I need to take the risk, or I’ll never get what I want.”

T: OK, now I’d like you to return to last evening when Tom told you he is developing feelings…describe the situation as closely as you can, and hear and see him as he said it. (Client describes scene in detail as therapist explores all sensory modalities)

T: As you relive that scene, can you feel any of the alarm bells inside you? [Client nods]

T: Holding that scene in mind, I’d like you to turn your attention down deep inside and I want you to focus on that alarm bell feeling…. As you do, the feeling will start to grow a bit stronger in your awareness…it’ll become bigger automatically as you focus your attention on it and it becomes the center of attention. Just let that feeling grow and as you focus on it, it gets stronger---just automatically—because it’s at the center of your attention…. Just let it grow, stronger and stronger…It’s getting bigger and bigger. (Client begins to show signs of emotional arousal.) That’s good, that’s fine; just let it grow, stronger and stronger…. You’re doing great…. Just let it come and grow, because we’re going to show how you can turn it off…. But for now, let it spread through your body and get stronger…. Like a tiny flame that gets bigger and bigger until it’s a blaze. Pay attention to how it grows…to what’s happening deep inside. Let it grow…getting stronger and stronger…bigger and bigger…stronger and stronger. Just feel that…that’s good. (Client begins to cry.) Tell me about the feeling.

C: I feel scared and alone. It’s like an icy hand in my stomach and chest. I want to run away from it.

T.: Focus on that feeling in your stomach and chest…That feeling spreading like an icy grip and getting even stronger…What thoughts are you having about that feeling?

C: I hate it…I want to get away from it…

T: …and you want to run from it…Feel that desire to run from it.

C: Like I usually do….

T: But this time, you’re going to face it down. Focus down inside…let it come…feel the feelings and let them come. Feel the feelings and let them come… feel the feelings and let them grow…feel the feelings and let them bubble up like a fountain, let them grow…just let them grow. That’s good, stronger and stronger… stronger and stronger. Those feelings come from deep inside and spread throughout your body… the feelings come from deep inside and spread throughout your body…growing more and more… more and more…stronger and stronger…just let it grow…feel the feelings…feel the feelings deep inside…that’s good…let it come…feel the feelings deep inside. Do any thoughts come to mind?

C: I’m so scared about letting myself get hurt again. If I open myself to Tom, I’m scared he’ll play me for a while, get the sex he wants and then dump me or hurt me like the others have.

T: It’s a scary thing to think about letting yourself get close and being so vulnerable to getting hurt.

C: I also wonder if anyone could really love me. I feel broken, ruined…I hate being alone, but I can’t stand being unlovable and waiting for the axe to fall.

T: Let that feeling of being vulnerable, that scary feeling get even stronger. Look at it; see what it’s like. It’s so scary to put yourself out there, to open yourself to Tom and take the chance he’ll use you or find that you’re not what he wants, that you are defective. Feel that feeling of being somehow defective, ruined. It’s so hard to trust, given what you’ve been through in the past. Feel that feeling…feel it.

C: (Sobbing) But I can’t stand the feeling. I’ve never felt it so strongly.

T: OK, we’re going to talk about this experience and what it means for you. But, for now, let’s practice turning that feeling off with the skills you’ve learned instead of running away from it. I’d like you to keep the feeling in your mind while you breathe down into your stomach and relax. Just letting go of all that tension and each time you exhale, letting those muscles relax. That’s good, just letting go…it’s your body and you can control it. Your muscles becoming limp and loose and relaxed. The inside of your body becoming calm and relaxed as the tension drains away, flowing out through your fingers and toes…And now we’re going to put one of those self-statements you chose together with your relaxation as you breathe. So, as you inhale into your stomach, say one of those stress-buster ideas to yourself. Then, at the top of your breath, say “so” and then a long, slow “relax” as you exhale. Do that with each breath and see how you can turn off that feeling. Show yourself that it’s your mind and your body and you can have greater control over the feelings that block you from getting the intimacy you want in your life. Try out the other self-statement by itself as well.

C: (after a series of breaths, during which she silently says to herself, “What’s past is past, and not the present or future, so relax,” and, “I need to take the risk, or I’ll never get what I want, so relax.”)It worked…Even though the scary feeling was really strong, I was able to get it back down.

A discussion of the feelings she experienced and their relevance to her life follows. The discussion centers on the conflict between her desire for intimacy and closeness and her fear of closeness and intimacy that makes her vulnerable to being hurt or exploited (almost surely related to her early sexual abuse within a close parental relationship). They discuss how, as closeness begins to develop, she experiences increasing anxiety which she reduces by either pulling away or behaving in a manner that drives the other away. The loss of the relationship reinforces her belief that she can’t trust closeness and that it is safer to keep people at arm’s length.

T: Great job. We’ve covered some important ground, and you’ve seen some relations between your needs, your feelings, and how you cope with them. As we work more on practicing your coping skills and as you apply them outside of our sessions in your life, you’ll be in a position to risk intimacy on a more rational basis. You can use the same integrated coping response on those feelings if they come up in a relationship. You learned early in life that closeness led to exploitation and hurt, and that was repeated and reinforced in other relationships. But, as your self-statement says, that need not be the case in the present or the future. As you master that fear of being hurt again, you won’t need to run away from closeness or do things that drive the other person away, and you can let your desire for a close intimate relationship be the dominant motive in how you relate, and you’ll reduce a big barrier to getting the closeness you desire. (Adapted from Smith & Ascough, in press).

Utilizing Diary Data for Collaborative Assessment and Outcome Tracking

The therapeutic approach described in the above examples, namely integrating CA and IA within CASMT, is consistentwith a coping skills model of stress reduction wherein successful regulation of high levels of arousal enhances coping self-efficacy. Given previous research showing that IA increases coping self-efficacy (Smith & Nye, 1989), we expect thatclients’ daily reports of out-of-session affect regulation will increase across treatment phase (skills acquisition [sessions 1–2] vs. skills rehearsal [sessions 3–6]), and we track this variable on a session-by-session basis, utilizing the daily data provided by the client.

At the individual level, we also examine possible mechanisms of change for improved affect regulation, specifically the use and effectiveness of two coping skills taught in CASMT, relaxation and rethinking (i.e., reappraisals based on cognitive restructuring and self-instructional training). We expect that clients will report increased use and effectiveness of these skills after beginning in-session coping skills rehearsal to reduce induced affective arousal. We also predict that higher levels of coping skills use will be associated with higher levels of reported affect regulation, and that coping skills use will precede affect regulation.

Additionally, we use the diary data to examine other indices of treatment response. We are interested in self-reported stress levels after the use of coping strategies. Feedback derived from these data help increase clients’ awareness of the effectiveness (or lack thereof) of particular coping strategies. We often find that coping skills rehearsal is associated with reductions in stress after coping, while not necessarily decreasing clients’ initial reactions to stressful situations (pre-coping stress). Finally, we track general life satisfaction to assess for potential changes in subjective well-being during treatment, reasoning that increased coping efficacy could facilitate life satisfaction (Gunzenhauser et al., 2013).

Although we have general predictions for adaptive coping, life satisfaction, and stress, because of the idiographic nature of CA-enhanced CASMT, we do not expect identical patterns of response for all clients. This will be illustrated in the following description of how three clients seen in our university-based outpatient clinic were tracked using the daily diary data.

Pretreatment Screening

The availability of a stress management program was made known to campus referral sources such as the Student Health Service and the Student Counseling Service. Posters were circulated to graduate student email lists, which we expected would reach individuals with above-average stresslevels, and placed in the medical/health sciences school. The posters offered assistance to individuals who were experiencing high life stress and were interested in learning stress coping skills.

Individuals who responded to the notice were screened over the phone to ensure CASMT was clinically appropriate to their needs. The computer-assisted telephone screen used in our clinic provides a standardized assessment of clinical symptoms. First, screeners ask callers an open-ended question (“What has led you to seek therapy at this time?”), followed by a series of diagnostic screening questions for common mental health problems (e.g., depression, anxiety, substance use). Each time the client answers “yes” to a screening question (e.g., “Have you been feeling unusually tense, anxious, or upset?”), a seriesof follow-up questions appear on the display to assess the severityand duration of these problems. The phone screen is not a formal DSM/ICD diagnostictool, but it provides the clinician with information and a basis for workinghypotheses about the client’s issues and treatment needs before the initial session.

Individuals were deemed a good fit for the programif they reported having difficulty managing high levels of life stressalong with arousal-oriented issues, such as symptoms of anxiety or anger. Individuals whose primary clinical issue was depression were referredto an evidence-based treatment for depression, such as cognitive therapy, behavioral activation, or interpersonal therapy. We believed this was the more clinically responsible course of action given that CASMT has not yet been tested for depression. However, this does not mean that CASMT is contraindicated for depressed clients. Although IA is designed for problems with a high autonomic arousal component, many clients with depression experience co-occurring anxiety that could be targeted by IA. Thecognitive skills component of CASMT, while focused on catastrophizing and not nearly as comprehensive in its scope as cognitive therapy, could be a suitable introduction to further treatment using cognitive modification approaches. Ultimately, the efficacy of CASMT for treating depression and its related symptoms remains an empirical question.

Eligible individuals were invited to attend a free information session about CASMT with their future therapist before deciding to begin the program. Treatment was provided by two doctoral students in clinical psychology with at least three years of previous clinical training following a structured training manual for CASMT (Smith, 2012; Smith & Ascough, in press). Each treatment session was one hour, for a total of six treatment hours. Data obtained from diaries was incorporated idiographically into the collaborative assessment component of the treatment, with each therapist deciding what kind of information would be of greatest benefit to share with the client (see Shoda et al., 2013 for examples).

The Clients

We have selected three clients who are highly representative of the type of clients who receive CASMT in our clinic and who best illustrate unique patterns of idiographic change that can occur during CASMT. All three clients reported anxiety symptoms, particularly worry, and impairment in occupational or social functioning as a result of stress. The following are de-identified descriptions of the three clients.

Client 1, “Ella.”

Ella was an Asian American female in her late 20’s. She was enrolled in a graduate program in the health sciences and was interested in decreasing her stress. Ella struggled with financial burdens and managing her time in completing the coursework in her rigorous graduate program. She experienced stress regarding the competing demands of her program, her social life, and her need to sleep. She frequently felt physically exhausted and overwhelmed with the many tasks that needed to be completed.

Client 2, “Penelope.”

Penelope was a Caucasian female in her late 20’s enrolled in a graduate program in the humanities. She reported struggling with worry about time management in her academic work, though in actuality she was quite effective at managing her time and frequently finished long-term assignments in advance. Penelope recognized her worries were somewhat unrealistic, but she also believed her anxiety helped keep her from falling behind. Other significant life stressors included her marriage and finances; she often felt resentment toward her husband for being in a “dead-end job‖ and they struggled to make ends meet.

Client 3, “Sarah.”

Sarah was a multiracial female in her early 30’s. She was enrolled in a graduate program in the sciences and was struggling with balancing the demands of motherhood and graduate school. Her daily stressors included having a child who was frequently sick, the academic demands of graduate school, and managing interpersonal conflict at work and at home. At intake, her primary method of coping was distraction so she was interested in learning more adaptive coping strategies for stress.

Diary Data Collection and Idiographic Time-Series Analysis

After the initial information session, clients are asked to complete two weeks of daily baseline data using the online stress and coping diary. To foster compliance, they receive a daily e-mail reminder. They continue completing the daily diary (which takes an average of 5–10 minutes to complete) throughout the six weeks of treatment. After the sixth and final treatment session, clients provided two weeks of follow-up data using the daily diary.

The diary data are incorporated into the treatment sessions as an integral part of the treatment. Using the stress and coping diary (Shoda et al., 2013; Smith et al., 2011; Wilson, 2008), weassess affect regulation daily with the item: “To what extent did you feel you were able to control your emotional reaction to this event?” (0 = I felt I had little or no personal control; 3 = I felt I had some personal control; 6 = I felt I had a great deal of personal control). Additional variables, such as coping use, coping effectiveness, stress level, and life satisfaction, were also assessed with the daily diary using similar 7-point scales. In addition to minimizing respondent fatigue, single item scales that capture the construct of interest have proven themselves to be valid indices of those constructs, having high convergent validity and predictive validity that often equal or exceed the validity of multiple-item measures(Burisch, 1984; Ptacek et al., 1994; van Rijsbergen, Burger, Hollon, Elgersma, Kok, Dekkeret et al., 2014).

For our within-person analyses, the daily diary entries were treated as a set of single-case time-series observations. These observations were not independent because the same client generated all of the entries. Instead, a client’s daily diary entries were autocorrelated, meaning that observations on day 1 can have a residual influence on day 2’s observations, and so on for days 3, 4, etc. Traditional parametric statistics assume independence of observations. Therefore, in order to avoid an increased probability of making a Type I error, we analyzed each client’s data using Simulation Modeling Analysis (SMA), a times series analysis program that controls for autocorrelation (Borckardt, Nash, Murphy, Moore & O’Neil, 2008), such that the N for any given analysis corresponded to the number of diary entries completed by a given client. Per Borckardt and colleagues (2008), time series analyses are well suited to address questions of improvement (does a client’s symptoms get better?) and questions of process (how does change unfold?) at the level of a single case. Using SMA, one can examine multivariate change processes by asking whether change in one variable (e.g., symptoms) is related to change in other variables, such as ongoing events in therapy (e.g., an intervention strategy, therapeutic alliance). One can even test questions of sequence (does change in one precede change in another?), although causal inferences cannot be drawn from such data. SMA is a freeware program, and both Macintosh and Windows versions, along with a user’s guide can be downloaded from the following website: clinicalresearcher.org.

To illustrate our approach to evaluating therapeutic progress, the data provided by Penelope, Ella, and Sarah were split into two phases: skills acquisition (SA; baseline assessment and sessions 1 and 2) and skills rehearsal (SR; sessions 3 through 6, and follow-up assessment). SMA graphed the data across the 49–60 data points for each client and provided significance tests of level and slope changes across the two phases. All three clients exhibited improvement beyond the p< .002 level of significance on their ratings of their ability to manage emotions, particularly negative ones, after the beginning of in-session skills rehearsal (Table 1). Figures 3a, 3b, and 3c show the significant increase in perceived affect regulation for all three clients. The dotted vertical line demarcates SA and SR phases.

Table 1.

Within-Person (Time Series) Analyses of Clients’ Affect Regulation Ratings over Two CASMT Training Phases (Skills Acquisition vs. Skills Rehearsal)

| Client | M Affect Regulation Skills Acquisition (Number of Observations) | M Affect Regulation Skills Rehearsal (Number of Observations) | Change (Post - Pre) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ella | 2.48 (25) | 3.80 (35) | 1.32 | <.001 |

| Penelope | 2.57 (21) | 4.32 (28) | 1.75 | .001 |

| Sarah | 4.09 (33) | 5.29 (24) | 1.20 | .002 |

Figure 3a.

Ella’s self-reported affect regulation showed a significant increase from the skills acquisitionphase (M = 2.48) to the skills rehearsal phase (M = 3.80; r = .59, p = .0001).

Figure 3b.

Penelope’s self-reported affect regulation showed a significant increase from skills acquisition (M = 2.57) to skills rehearsal (M = 4.32; r = .58, p = .001).

Figure 3c.

Sarah’s self-reported affect regulation showed a significant increase from skills acquisition (M = 4.09) to skills rehearsal (M = 5.29; r = .48, p = .002).

In their orientation to CASMT, clients are told that they will be exposed to a “buffet” of coping skills (deep breathing, muscle relaxation, cognitive restructuring, self-instructional training) that can be tailored to their own needs and preferences. Therefore, it is expected that individual clients will emphasize use of the skills that they find most credible and personally effective, and we are very interested in these differences. Not unexpectedly, there was not a single pattern of results that applied uniformly to all three clients. For example, all three clients reported increased use and effectiveness of relaxation from the SA to SR phase (Table 2), but they showed differences regarding the cognitive coping skills (Table 3). Ella reported finding rethinking more effective in the SR phase, but did not report using it more. In contrast, Sarah reported using rethinking to a greater extent in the SR phase, but did not report finding it significantly more effective. Finally, Penelope did not report a significant increase in rethinking use or effectiveness between the SA and SR phases. Penelope reported to her therapist that she found physical relaxation skills more effective for her worry than rethinking. As stated previously, clients are not expected to utilize coping skills in a uniform fashion or to find all coping skills equally effective. The divergent results for Ella, Penelope, and Sarah illustrate how improvement, in the form of either increased coping skill use or effectiveness, can look different between clients. Such improvement can be lost when aggregating across individuals.

Table 2.

Within-Person (Time Series) Analyses of Clients’ Relaxation Skills Use and Effectiveness over Two CASMT Training Phases (Skills Acquisition vs. Skills Rehearsal)

| Client | M Relaxation Use | p | M Relaxation Effectiveness | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SA (N) | SR (N) | SA (N) | SR (N) | |||

| Ella | 1.44 (25) | 2.61 (36) | .006 | 2.47 (15) | 3.79 (33) | .004 |

| Penelope | 1.52 (21) | 3.59 (27) | .009 | 2.78 (9) | 3.96 (24) | .018 |

| Sarah | 0.21 (33) | 2.17 (24) | <.001 | 2.67 (3) | 5.31 (13) | .019 |

Note. SA = Skills Acquisition Phase; SR = Skills Rehearsal Phase; N = number of observations per phase. Extent-use and effectiveness responses were made on 7-point scales ranging from 0 (not at all) to 6 (a great deal).

Table 3.

Within-Person (Time Series) Analyses of Clients’ Rethinking Skills Use and Effectiveness over Two CASMT Training Phases (Skills Acquisition vs. Skills Rehearsal)

| Client | M Rethinking Use | p | M Rethinking Effectiveness | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SA (N) | SR (N) | SA (N) | SR (N) | |||

| Ella | 2.56 (25) | 2.42 (36) | .826 | 3.00 (22) | 3.78 (32) | .024 |

| Penelope | 1.43 (21) | 1.19 (27) | .559 | 2.00 (11) | 2.07 (13) | .857 |

| Sarah | 1.61 (33) | 2.96 (24) | .005 | 4.00 (18) | 5.00 (18) | .149 |

Note. SA = Skills Acquisition Phase; SR = Skills Rehearsal Phase; N = number of observations per phase. Extent-use and effectiveness responses were made on 7-point scales ranging from 0 (not at all) to 6 (a great deal).

To illustrate how SMA can be used to understand change processes, specifically whether change in one variable precedes or follows change in another variable, we examined cross-lagged correlations of both relaxation and rethinking skills use with perceived affect regulation (Figures 4a–4c). Cross-lagged correlations point to the direction and timing of influence between two variables after controlling for autocorrelation (Borckardt et al., 2008). For instance, lag 0 is the correlation of skill use and affect regulation within the same diary entry, i.e., on the same day. A lag +1 correlation is the relationship between skills use on day K with affect regulation the following day (K+1), while a lag −1 correlation is the relationship between skills use on day K with affect regulation on the previous day (K−1).

Figure 4a.

Cross-lagged correlations showing directional and temporal relationships between relaxation skills use and perceived affect regulation for Ella.

Figure 4c.

Cross-lagged correlations showing directional and temporal relationships between relaxation skills use and perceived affect regulation for Sarah.

As expected, our three clients differed in the degree to which skills use was related to affect regulation. For relaxation skills, Ella (Figure 4a) reported the strongest relationship between skills use and affect regulation with lag 0 and lag +2 correlations, meaning that on days when she used relaxation skills, she also felt more control over her emotional responses, and that higher relaxation skills use on a given day was predictive of better affect regulation two days later. For Penelope (Figure 4b), we found significant lag +1 and +2 correlations, where relaxation skills use predicted future affect regulation one to two days later, but there was also a significant lag −1 correlation, which meant that better affect regulation on a given day also predicted more relaxation skills use the following day. The fact that relaxation skills use and affect regulation affected each other bidirectionally is not surprising given the social cognitive theory of reciprocal determinism (Bandura, 2001) and the evidence supporting reciprocal processes between behavior and emotion (e.g., Teasdale, 1983; Witkiewitz & Villarroel, 2009). In contrast, Sarah(Figure 4c) did not show any significant correlations between relaxation skills use and affect regulation, despite reporting greater use and effectiveness of relaxation over the course of treatment. Additionally, none of the three clients reported any significant cross-lagged correlations between rethinking use and affect regulation, which may reflect the relative difficulty of learning these skills, compared to somatic coping skills, and/or the brief nature of the therapy, wherein the effects of more complex coping skills on affect regulation may not have been apparent until after the follow-up period.

Figure 4b.

Cross-lagged correlations showing directional and temporal relationships between relaxation skills use and perceived affect regulation for Penelope.

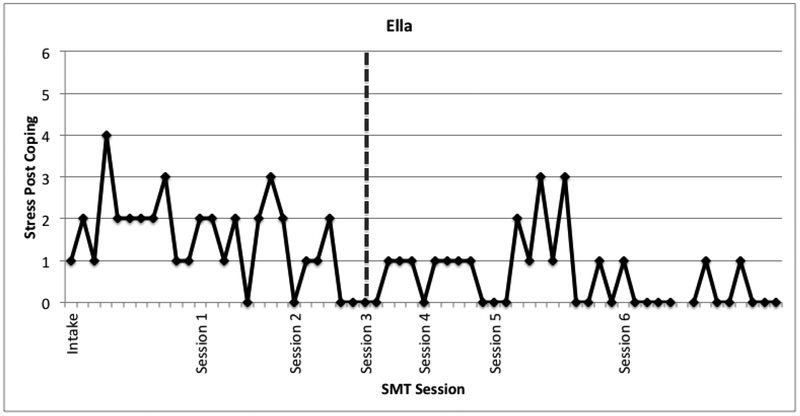

In these three clients, we also found evidence for treatment benefits beyond perceived affect regulation. As with the variability in coping skills utilization, there were different patterns of global treatment response across clients. For example, Ella reported a significant decrease in her post-coping stress levels from the SA to SR phase (Figure 4a), but no significant change in life satisfaction, whereas Penelope reported a significant increase in life satisfaction from the SA to SR phase (Figure 4b). These data illustrate how, even with a manualized therapy, treatment response can behighly individual.

Discussion

Induced affect (IA), as applied in CASMT, is designed to enhance coping self-efficacy by allowing clients to practice their coping skills under conditions of high affective arousal, a proposition supported in outcome research (Smith & Nye, 1989). Consistent with the major objective of CASMT, all three clients reported greater perceived affect regulation in the SR phase compared to the SA phase. We also found that all three clients reported greater use and effectiveness of relaxation skills over time, and, for two of the clients, greater relaxation skills use predicted improved affect regulation one or two days later. While a number of studies have shown that eliciting affect in-session is associated with improved treatment outcome (Diener, Hilsenroth, & Weinberger, 2007; Greenberg & Pascual-Leone, 2006; Missirlian, Toukmanian, Warwar, & Greenberg, 2005; Pos, Greenberg, Goldman, & Korman, 2003), the present study suggests that going beyond affect elicitation per se to using affective arousal as a vehicle for coping skills rehearsal may enhance affect regulation in clients’ daily lives. IA allows clients to rehearse adaptive coping skills in response to strong affective cues in-session, which we hypothesize strengthens generalization of self-regulation skills (Ehrenreich et al, 2007; Sipprelle, 1981). Skills generalization may contribute to other clinical benefits beyond perceived affect regulation, as supported by thedecreases in stress after coping and increases in life satisfactionreported by two of our clients. However, it is notable that there was not a uniform pattern of change across all three clients, highlighting again the idiographic nature of treatment response.

Any causal inferences about the role of IA in improving affect regulation through enhanced skills rehearsal and generalization are necessarily tentative without a large, randomized trial that includes a control comparison. For example, it is possible that these effects could be due to increased skills acquisition over time, regardless of IA. What the results do provide is initial evidence that changes in affect regulation are associated significantly (i.e., well beyond chance) with the introduction of an intervention, namely IA, and that changes in affect regulation are sometimes preceded by skills use.

Our within-person analyses reveal the kinds of diverse information that can be gained from collaborative assessment through daily diary tracking. Within-person analyses allowed us to identify improvements in treatment outcome variables on a case-by-case basis; these improvements could have been lost had we only examined mean differences at the group level. Idiographic analyses revealed that the effect of a given intervention could differ depending on the individual client; hence, within-person analyses may be helpful for better understanding individualized treatment response, a top research and funding priority of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH, 2008).

Moreover, daily data collection allows therapists to present clients with feedback concerning patterns of relations between stressors, coping responses, and outcomes that may not be apparent to clients, using the client’s own report rather than therapist inference, which may be less credible to clients. Such data may lead to adjustments in treatment emphasis and therapeutic goals. For example, of the CASMT coping strategies, cognitive restructuring is generally more challenging than self-instructional training, particularly if a client is not psychologically minded or highly analytical(D’Alcante, Diniz, Fossaluza, Batistuzzo, Lopes, et al., 2012; Kiluk, Nich, & Carroll, 2011; Wild & Gur, 2008). In such instances, if the daily data suggested a client was not finding cognitive restructuring useful, the therapist may choose to focus on pairing self-instructional statements with cued relaxation instead of restructuring. Another example would be seeing a particular client’s coping skill use fluctuate in tandem with the previous day’s affect regulation, as was found with Penelope. Depending on the situation and the client, it could be problematic ifa client believes she has little control over her emotions and responds by using her coping skills less. A therapist may share this information with a client and problem solve ways to reverse the association, such that lower affect regulationbecomes a trigger for more coping skill use, as thisis more likely to restore the client’s sense of controllability over her emotional reactions. The daily diary could track the effectiveness of this intervention.

Applying and Adapting CASMT

The standard protocol in the controlled outcome studies of CASMT is the six-session intervention described above. On the one hand, the relative brevity of the intervention is advantageous, and it has proven efficacious with a wide range of populations (Crocker, 1989; Jacobs et al., 2012; Rohsenow et al., 1985; Smith & Ascough, 1984, in press; Smith & Nye, 1989; Smith et al., 2011; Ziegler et al., 1982). However there is no restriction on the number of sessions that could be included within the intervention template we provide. Indeed, the protocol described above could be viewed not in terms of specific sessions, but as treatment phasesthat can proceed at theirown pace to accommodate the needs and abilities of the individual client or group.

As noted earlier, in developing cognitive coping skills, we are not attempting to conduct an extensive restructuring of maladaptive core beliefs, as in many cognitive therapies. Rather, we are focusing in particular on catastrophizing cognitions, which have been shown to be major mediators of distress (Kalisch & Gerlicher, 2014). Certainly, however, a therapist could elect to devote additional sessions to a more thorough treatment of automatic thoughts and core dysfunctional beliefs, if desired. At the same time, we view this protocol as one in which the major locus of coping skills acquisition occurs outside of the formal sessions and in the skills practice and self-assessment done in homework assignments and the daily diary. Within a six-week period of daily homework assignments, considerable skill development can occur. As noted earlier, studies (including meta-analyses) on bibliotherapy effects provide extensive evidence that clients with a variety of affect-based disorders can benefit from such materials, sometimes to a level equivalent to that of “live” therapist-administered treatment (Edenfield & Saeed, 2012; Furmark et al., 2009; Gregory et al., 2004; Schelver & Gutsch, 1983). Obviously, however, the effects achieved depend on the quality of the resource materials, and we have attempted to condense “best practice” cognitive training techniques into a manageable set of resource materials (Smith, 2012; Smith & Ascough, in press).

Limitations and Future Directions

One limitation of using the daily diary as a primary outcome measure is that all of the data are self-reported. We cannot rule out the possibility that demand characteristics, such as a desire to please the therapist by reporting improvement, can influence reports. However, if demand characteristics accounted for all of the effects, we might expect all clients to report using adaptive skills more often and to report finding both more effective, but we instead find highly variable patterns in reported coping skill use and effectiveness. The key to avoiding self-report error variance is the collaborative nature of the relationship fostered between therapist and client.

Because all data in single-client assessment are inherently correlational in nature, one cannot infer causality; randomized controlled studies remain the gold standard for efficacy research. However, as Boswell, Anderson, and Barlow (2014) argue in a single-case analysis of their Unified Protocol treatment, time series data with lagged analyses not only allow for idiographic analysis of individual client responses to interventions, but they can provide important clues to mediators of change. In that vein, our results provide preliminary evidence that the introduction of in-session skills rehearsal through IA is followed by improvements in affect regulation, stress, and life satisfaction, and that changes in coping skill use can precede changes in affect regulation (Figures 3 through 5). However, without a control condition, we cannot rule out that these improvements would be seen without the introduction of IA. Such data can form a basis for hypotheses about mechanisms of change that can be tested through group-level meditational analyses with large samples.

Figure 5a.

Ella’s self-reported stress post-coping showed a significant decrease from skills acquisition (M = 1.56) to skills rehearsal (M = .60; r = .47, p = .006). Self-reported stress levels after the use of coping behaviors was assessed with the item: “How stressful was the event after engaging in coping behaviors?” (0 = Not at all stressful; 3 = Somewhat stressful; 6 = Extremely stressful).

The ongoing use of CA may be another potential mechanism of change that warrants further testing. Individuals who experience stress or anxiety often report low perceived control of their emotions and their environment (Brown, White, Forsyth, & Barlow, 2004; Chorpita & Barlow, 1998). Through regular self-monitoring and collaborative discussion of assessment results in therapy, ongoing CA may give “control” back to clients through improved understanding of their problematic cognitive, emotional, and behavioral patterns. Ongoing CA may help provide the insight clients need to regain regulation of their emotions. As noted earlier, number of diary entries was related to improvement in a recent clinical trial of CASMT (Chen, 2015). Future research should assess if this combination of CASMT with ongoing CA is more effective than either on its own using a dismantling trial or a randomized clinical trial. If ongoing CA is beneficial alone, it may be possible to adapt the online daily diary for individuals and populations who have difficulties coming into therapy sessions.

Conclusions

Stress management skills training addresses an important public health need by providing brief, evidence-based treatment that can be disseminated at the population level. Helping people cope more successfully with stress would make a positive contribution to both physical and psychological wellbeing (APA, 2013). CASMT, with its broad focus on general coping skills that are not limited to any particular diagnostic group, fits well within a stepped-care system that emphasizes “reach” at the initial level of care.

The incorporation of IA into CASMT addresses a potential pitfall of coping skills interventions. Coping skills interventions may tacitly assume that delivery of skills training translates into effective utilization of these skills. Meuret and colleagues (2012), in reviewing the lack of evidence that coping skills trainings augment the efficacy of exposure therapy, have called for the independent measurement of both frequency of use and effectiveness of the coping skills. In IA, the therapist is able to evaluate the quality of the client’s cognitive reappraisals and self-instructional self-statements during rehearsal of the integrated coping response. IA also permits behavioral observation of clients’ ability to reduce arousal, allowing the therapist to assess mastery of coping skills. Some IA therapists have also monitored physiological responses, such as heart rate, to provide multiple, concurrent assessment methods (Ascough et al., 1981; Smith & Ascough, 1984). For clients, IA provides the opportunity to rehearse relaxation and rethinking skills under conditions of high affective arousal, which may support increased coping self-efficacy, increased affect regulation, and improved generalization of coping skills to real-world stressful situations.

Collaborative assessment (CA) through an online stress and coping diary may augment the effect of CASMT’s coping skills training. Like other forms of self-monitoring, CA may increase client awareness of discrepancies between current behavior and goals, thus increasing motivation for behavior change (Bandura, 1997). In this study, therapists used the daily diaries to guide and enhance in-session therapeutic procedures. Incorporating technology into treatment in this novel way has the potential toenhance the effectiveness of existing psychotherapies.

Figure 5b.

Penelope’s self-reported life satisfaction showed a significant increase from skills acquisition (M = 5.24) to skills rehearsal (M = 7.31; r = .61, p = .03). Life satisfaction was assessed with the item: “Overall, how would you rate your general life satisfaction at this time?” (0 = Most unhappy; 10 = Most happy).

Highlights.

We reviewtwo components of Cognitive-Affective Stress Management Training (CASMT).

Induced affect (IA)is a technique that permits in-session coping skills rehearsal.

IA may improve perceivedemotionregulation and skills generalization.

Collaborative assessment (CA) via an online daily diary informs the therapy.

CA mayhelp with coping skills generalization and outcome tracking.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources

Development of the Internet-based daily diary assessment described in this article was supported by NIMH Grant MH39349. Manuscript preparation was supported in part by a grant from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (F31AA020134).

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no real or potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Aaron LA, Turner JA, Mancl L, Brister H, & Sawchuk CN (2005). Electronic diary assessment of pain-related variables: Is reactivity a problem? The Journal Of Pain, 6(2), 107–115. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2004.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abrams DB, & Wilson GT (1979). Self-monitoring and reactivity in the modification of cigarette smoking. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 47(2), 243–251. doi: 10.1037//0022-006X.47.2.243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida DM (2005). Resilience and vulnerability to daily stressors assessed via diary methods. Current Directions In Psychological Science, 14(2), 64–68. doi: 10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00336.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ascough JC, Moore CH, & Sipprelle CN (1981). Induced anxiety: A method for research and behavior change. Delphi, IN: Center for Induced Affect [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York, NY: W H Freeman/Times Books/Henry Holt & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review Of Psychology, 521–26. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT (1976). Cognitive therapy and the emotional disorders. New York: International Universities Press. [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz L (1990). On the formation and regulation of anger and aggression: A cognitive-neoassociationistic analysis. American Psychologist, 45, 494–503.doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.45.4.494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boer AP (1970). Toward preventive psychotherapy: Experimental reduction of psychophysiological stress through prior behavior therapy training.(Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of South Dakota, Vermillion, SD. [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, Davis A, & Rafaeli E (2003). Diary methods: Capturinglife as it is lived. Annual Review of Psychology, 54, 579–616. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borckardt JJ, Nash MR, Murphy MD, Moore M, Shaw D, & O’Neil P (2008). Clinical practice as natural laboratory for psychotherapy research: A guide to case-based time-series analysis. American Psychologist, 63(2), 77–95. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.63.2.77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bower GH (1981). Mood and memory. American Psychologist, 36(2), 129–148. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.36.2.129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, White KS, Forsyth JP, & Barlow DH (2004). The structure of perceived emotional control: Psychometric properties of a revised Anxiety Control Questionnaire. Behavior Therapy, 35(1), 75–99. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(04)80005-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burisch M (1984). You don’t always get what you pay for: Measuring depression with short and simple versus long and sophisticated scales. Journal of Research in Personality, 18(1), 81–98. doi: 10.1016/0092-6566(84)90040-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burke LE, Wang J, & Sevick MA (2011). Self-monitoring in weight loss: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of the American Dietetic Association Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 111(1), 92–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2010.10.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles ST, Piazza J, Mogle J, Silwinski M, & Almeida D (2013). The wear and tear of daily stressors on mental health. Psychological Science, 24(5), 733–741. doi: 10.1177/0956797612462222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JA (2015). The effects of systematic self-monitoring, feedback, and collaborative assessment on stress reduction(Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Washington, Seattle. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng C, Lau HB, & Chan MS (2014). Coping flexibility and psychological adjustment to stressful life changes: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 140(6), 1582–1607. doi: 10.1037/a0037913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, & Barlow DH (1998). The development of anxiety: The role of control in the early environment. Psychological Bulletin, 124(1), 3–21. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.124.1.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocker PRE (1989). A follow-up of cognitive-affective stress management training. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 11, 236–242. [Google Scholar]

- Cuthbert BN & Insel TR (2013). Toward the future of psychiatric diagnosis: The seven pillars of RDoC.BMC Medicine, 11(1), 1–8. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Alcante CC, Diniz JB, Fossaluza V, Batistuzzo MC, Lopes AC, Shavitt RG, & … Hoexter MQ (2012). Neuropsychological predictors of response to randomized treatment in obsessive–compulsive disorder. Progress In Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry, 39(2), 310–317. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2012.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener MJ, Hilsenroth MJ, & Weinberger J (2007). Therapist affect focus and patient outcomes in psychodynamic psychotherapy: A meta-analysis. American Journal of Psychiatry, 164(6), 936–941. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.164.6.936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenreich JT, Fairholme CP, Buzzella BA, Ellard KK, & Barlow DH (2007). The role of emotion in psychological therapy. Clinical Psychology: Science & Practice, 14(4), 422–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2007.00102.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis A (1962). Reason and emotion in psychotherapy. Secaucus, N.J: Citadel Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer CT, & Finn SE (2008). Developing life meaning of psychological test data: Collaborative and therapeutic approaches In Archer RP & Smith SR (Eds.), Personality assessment (pp. 379–404). New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S (2011). Stress, health, and coping: An overview In Folkman S, Folkman S (Eds.),The Oxford handbook of stress, health, and coping (pp. 3–11). New York, NY, US: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Glick SN, Winer RL, & Golden MR (2013). Web-based sex diaries and young adult men who have sex with men: Assessing feasibility, reactivity, and data agreement. Archives Of Sexual Behavior, 42(7), 1327–1335. doi: 10.1007/s10508-012-9984-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouin JP (2011). Chronic stress, immune dysregulation, and health.American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, 5(6), 476–485. doi: 10.1177/1559827610395467 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg LS,& Pascual-Leone A (2006). Emotion in psychotherapy: A practice-friendly research review. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62(5), 611–630. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunzenhauser C, Heikamp T, Gerbino M, Alessandri G, von Suchodoletz A, Di Giunta L, & … Trommsdorff G (2013). Self-efficacy in regulating positive and negative emotions: A validation study in Germany. European Journal Of Psychological Assessment, 29(3), 197–204. doi: 10.1027/1015-5759/a000151 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hufford MR, Shields AL, Shiffman S, Paty J, & Balabanis M (2002). Reactivity to ecological momentary assessment: An example using undergraduate problem drinkers.Psychology Of Addictive Behaviors, 16(3), 205–211. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.16.3.205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs RS, Smith RE, Fiedler FE, & Link TG (2012). Using stress management training to enhance leader performance and the utilization of intellectual abilities during stressful military training: An application of cognitive resource theory In VanVactor JD (Ed.), The psychology of leadership (pp. 61–79). New York: Nova Science Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, & Blase SL (2011). Rebooting psychotherapy research and practice to reduce the burden of mental illness. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(1), 21–37. doi: 10.1177/1745691610393527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, & Mascitelli S (1982). Covert and overt rehearsal and homework practice in developing assertiveness. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 50(2), 250–258. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.50.2.250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiluk BD, Nich C, & Carroll KM (2011). Relationship of cognitive function and the acquisition of coping skills in computer assisted treatment for substance use disorders. Drug And Alcohol Dependence, 114(2–3), 169–176.doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.09.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein AS, Skinner JB, & Hawley KM (2013). Targeting binge eating through components of dialectical behavior therapy: Preliminary outcomes for individually supported diary card self-monitoring versus group-based DBT. Psychotherapy, 50(4), 543–552. doi: 10.1037/a0033130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert MJ (2010). Using progress feedback to inform treatment: Conceptual issues and initial findings In Lambert MJ, Prevention of treatment failure (pp. 109–134). Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM (2015). DBT skills training manual (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford [Google Scholar]

- Martell CR, Addis ME, & Jacobson NS (2001). Depression in context: Strategies for guided action. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Meichenbaum D (1977). Cognitive-behavior modification: An integrative approach. New York, NY: Plenum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Meichenbaum D (1985). Stress inoculation training. New York: Pergamon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Meichenbaum D, & Novaco R (1985). Stress inoculation: A preventative approach. Issues In Mental Health Nursing, 7(1–4), 419–435. doi: 10.3109/01612848509009464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meuret AE, Wolitzky-Taylor KB, Twohig MP, & Craske MG (2012). Coping skills and exposure therapy in panic disorder and agoraphobia: Latest advances and future directions. Behavior Therapy, 43(2), 271–284. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2011.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mischel W, & Shoda Y (1995). A cognitive-affective system theory of personality: Reconceptualizing situations, dispositions, dynamics, and invariance in personality structure. Psychological Review, 102(2), 246–268. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.102.2.246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]