Abstract

We report two cases of deaths resulting from complications of odontogenic infections/submandibular space infections. In one case, the decedent had a history of toothache as well as facial and tongue swelling; autopsy revealed inflammation involving the tongue and larynx. In the second case, the decedent had a history of toothache, and at autopsy there was spread of infection to the mediastinum. Ludwig's angina is a form of submandibular space infection, which often is a result of odontogenic infection. The infection can spread into the deep spaces of the neck, producing complications including edema of the tongue and pharynx (causing airway obstruction), descending mediastinitis, pericarditis, necrotizing fasciitis, pleural empyema, and pneumonia. Gross findings at autopsy might reveal a dental abscess or other forms of infection of the head and neck, necrosis of the neck muscles and larynx, and infrequently, infection extending to the chest cavity. Microscopically, there is acute inflammation with necrosis and/or granulation tissue predominantly within the fascia. Without treatment, submandibular space infections can be life threatening and progression to death can be swift. These cases demonstrate the lethal effects of odontogenic infections. Without a clinical history of toothache or dental abscess, one can be alerted to a possible submandibular space infection by identifying isolated necrosis of the neck musculature.

Keywords: Forensic pathology, Odontogenic infection, Submandibular space infection, Ludwig's angina, Deep neck infection

Introduction

Submandibular space infections are often odontogenic in origin. Some complications include Ludwig's angina and less commonly, spread of the infection to the mediastinum. Two cases of decedents who died from complications of odontogenic infections are presented.

Case 1

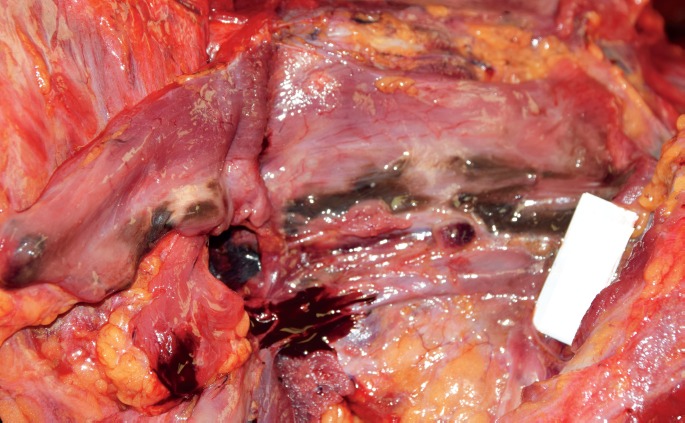

A 43-year-old male with a history of hypertension was found unresponsive in bed in a hotel room. About a week prior to his demise, a hotel clerk noted that one side of the decedent's face was swollen, and the decedent mentioned suffering from “some kind of skin problem.” A hotel staff member also told family members that prior to his death, the decedent complained of a swollen tongue and facial swelling and communicated by writing, as he was not able to communicate verbally. Days before death, he notified his employer that he would take time off due to a toothache. At autopsy, the decedent was in a mild state of decomposition with bloating of the face, abdomen, and scrotum. The subcutaneous and subgaleal tissues of the decedent's right scalp were edematous (Image 1), and the right sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM) showed green-brown discoloration and softening (Image 2). The buccal aspects of the teeth and the oral mucosa did not appear to be obviously inflamed. The heart was enlarged (450 g) and there was an occlusive, healing thrombus within the left anterior descending coronary artery (Image 3).

Image 1.

Case 1: Edema of the subcutaneous tissues of the scalp.

Image 2.

Case 1: Necrosis involving the right neck tissues.

Image 3.

Case 1: Occlusive, healing thrombus within the left anterior descending coronary artery.

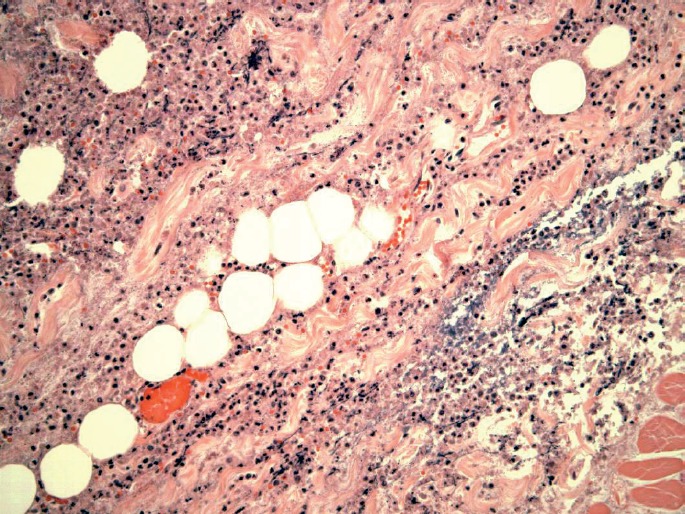

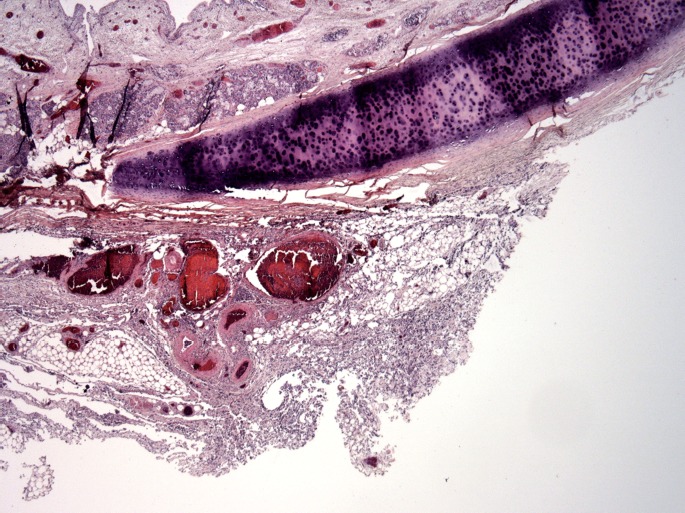

Microscopically, there was acute inflammation of the right SCM (Image 4), the tongue (Images 5 and 6), epiglottis (Image 7), and the adventitia of the trachea (Images 8 and 9). The left anterior descending artery contained a healing thrombus with recanalization and focal hemorrhage and there was fibrosis and mild chronic with focal acute inflammation within the heart (Images 10 and 11). This patient's cause of death was determined to be “complications of submandibular space infection,” with other significant conditions contributing to his death as “atherosclerotic and hypertensive cardiovascular disease.” The manner of death was natural.

Image 4.

Case 1: Right sternocleidomastoid muscle with acute inflammation (H&E, x200).

Image 5.

Case 1: Tongue with acute inflammation (H&E, x40).

Image 6.

Case 1: Tongue with acute inflammation (H&E, x400).

Image 7.

Case 1: Epiglottis with acute inflammation (H&E, x200).

Image 8.

Case 1: Trachea with acute inflammation of the adventitia (H&E, x40).

Image 9.

Case 1: Trachea with acute inflammation of the adventitia (H&E, x200).

Image 10.

Case 1: Heart with fibrosis and mild chronic and focal acute inflammation (H&E, x40).

Image 11.

Case 1: Heart with fibrosis and mild chronic and focal acute inflammation (H&E, x400).

Case 2

A 51-year-old female who had recently been complaining of ongoing jaw pain and swelling secondary to an abscessed tooth was found dead in her armchair one morning. At autopsy, the left cheek mucosa and gingiva of the left side of the mandible were edematous, with necrotic tissue and purulent fluid. The left lower first molar (tooth #19) was absent, the socket was necrotic with purulent fluid, and the left lower second molar (tooth #18) had a deep necrotic cavity (Image 12). There was purulent fluid and necrosis of the anterior musculature and fascial tissues bilaterally (Image 13) and extending into the anterior mediastinum (Image 14). The epicardial surface displayed green discoloration with fibropurulent adhesions.

Image 12.

Case 2: Left side of the mandible with necrotic tissue and purulent fluid.

Image 13.

Case 2: Right side of the neck with necrosis of the tissues.

Image 14.

Case 2: Infection involving the anterior mediastinum.

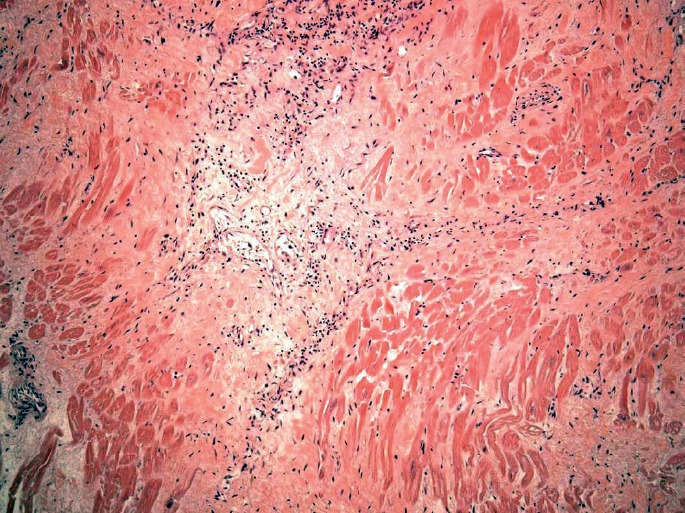

Microscopically, the gingival tissue and neck musculature showed acute and chronic inflammation with necrosis and granulation tissue (Images 15–17). The heart had bacterial overgrowth, which was prominent along the epicardial surface, and perivascular and interstitial fibrosis. The cause of death was determined to be “sepsis due to an abscessed tooth.” The manner of death was natural.

Image 15.

Case 2: Microscopic sections of the gingival tissue and neck musculature revealing acute inflammation and necrosis (H&E, x100).

Image 17.

Case 2: Microscopic sections of the gingival tissue and neck musculature revealing areas of acute inflammation and chronic changes (H&E, x400).

Image 16.

Case 2: Microscopic sections of the gingival tissue and neck musculature revealing areas of acute inflammation and chronic changes (H&E, x200).

Discussion

Ludwig's angina is a result of a submandibular space infection. Submandibular space infections can result in rapidly expanding cellulitis of the deep spaces of the neck and can cause significant morbidity and mortality (1–5). In 1836, Wilhelm Fredrick von Ludwig described this entity and a year later the disease process was named after him (1–7). Ludwig's angina itself is one specific pattern of infection seen in the spectrum of deep neck space infections. The infection can be rapidly progressive, which can lead to inflammation of the tongue, pharynx, and fascial planes of the neck; involvement of any or all of these anatomic areas may lead to respiratory tract infection, airway obstruction, and death.

Descriptions of the submandibular space differ in literature (3, 5, 8). The submandibular space is essentially from the mucosa of the floor of the mouth superiorly to the superficial layer of the deep cervical fascia of the inferior mandible to the hyoid bone inferiorly (5, 8). The submandibular space can be divided into two spaces: the sublingual space, which is superior to the mylohyoid muscle; and the submaxillary space, which is inferior to the mylohyoid muscle (3, 5, 8, 9). Because the spaces communicate through fascial planes, infection spreads by continuity rather by lymphatics or blood vessels (5, 9–11).

Most authors cite odontogenic infections in the submandibular space as the most common source of infection, with 34–90% of cases being cited as odontogenic in origin (1, 3, 12–16). Other sources of infection have been documented and include, but are not limited to, superficial skin infections, penetrating trauma, sialadenitis, foreign bodies in the airway, infections of congenital cysts (e.g., branchial cleft cysts and thyroglossal duct cysts), and underlying malignancies that have become superinfected (1, 3, 5, 13–21).

Without treatment, complications of submandibular space infections are often life threatening, and progression to death may be swift. Complications are varied and include airway obstruction via progressive edema of the tongue and pharynx, sepsis with or without septic emboli and/or septic shock, Lemierre syndrome (thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein), descending mediastinitis, pericarditis, necrotizing fasciitis, pleural empyema or pneumonia, cavernous sinus thrombosis, disseminated intravascular coagulation, carotid artery pseudoaneurysm or rupture, hepatic failure, or acute respiratory distress syndrome (1, 3, 5, 12, 14–16, 19–22). Most commonly, however, life threatening complications arise in the form of airway obstruction (3). The mortality rate for deep neck space infections in general has been reported to range from 0.8–8% (3, 4, 12, 14, 16, 19, 22), a decrease from rates exceeding 50% due to introduction of antibiotics in the 1940s, improved oral and dental hygiene, and surgical techniques (23). It should be noted, however, that mortality rates may reach 20–50% in patients with descending mediastinitis as a complication (3, 12), up to 40% in those with “retrograde spread of infection from the upper dentition or paranasal sinuses,” causing cavernous sinus thrombosis (3), and up to 40% in patients with carotid artery erosion (12).

The vast majority of causative bacterial organisms are polymicrobial in origin; this is mainly due to their nature as being mainly odontogenic in origin. That is, a mixture of normal oral flora and pathogenic flora are nearly always identified as causative organisms in cases of deep neck space infections. It appears that the microbial makeup of submandibular space infections varies based on the geographic location of the population studied and also upon the prevalence of underlying comorbidities, such as diabetes, in a given population. Overall, though, it seems that the most commonly implicated pathogens include viridans group streptococci, Prevotella sp., and group A streptococci, all of which are commonly found in the human mouth. There has been noted in the literature a rise in incidence of deep neck space infections with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) as the causative organism; it is thought that this rise is concomitant with the well-known increasing incidence of infections with MRSA in the general population (3, 5, 21). There have also been several studies that show an increased presence of Klebsiella pneumoniae as the predominant causative organism in diabetic individuals (5, 15, 16, 19, 21).

Conclusion

In case 1, the history of a toothache was not known until after autopsy examination. Microscopic examination showing necrosis and acute inflammation of the sternocleidomastoid muscle prompted further investigation of the decedent's clinical history prior to death. A possible clue to the presence of a submandibular space infection is the necrotic appearance of the anterior neck muscles, as seen in both of our cases. This should alert the pathologist to take a closer look of the teeth, mouth, or face to search for a source of infection and to submit histological sections of the neck muscles, tongue, and laryngeal tissues to rule out infection as a possible cause of death.

Footnotes

ETHICAL APPROVAL

As per Journal Policies, ethical approval was not required for this manuscript

STATEMENT OF HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

This article does not contain any studies conducted with animals or on living human subjects

STATEMENT OF INFORMED CONSENT

No identifiable personal data were presented in this manuscsript

DISCLOSURES & DECLARATION OF CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors, reviewers, editors, and publication staff do not report any relevant conflicts of interest

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE The authors have indicated that they do not have financial relationships to disclose that are relevant to this manuscript

References

- 1).Srirompotong S., Art-Smart T. Ludwig's angina: a clinical review. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2003. Aug; 260(7): 401–3. PMID: 12937916. 10.1007/s00405-003-0588-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2).Carlotti A.P., Bachette L.G., Carmona F. et al. Discrepancies between clinical diagnoses and autopsy findings in critically ill children: a prospective study. Am J Clin Pathol. 2016. Dec; 146(6): 701–8. PMID: 27940427. 10.1093/ajcp/aqw187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3).Christian J.M., Goddard A.C., Gillespie M.B. Cummings otolaryngology-head and neck surgery. 6th ed (ebook). Philadelphia: Saunders; c2015 Chapter 10, Deep neck and odontogenic infections; p. 164–75. [Google Scholar]

- 4).Costain N., Marrie T.J. Ludwig's angina. Am J Med. 2011. Feb; 124(2): 115–7. PMID: 20961522. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5).Boscolo-Rizzo P., Da Mosto M.C. Submandibular space infection: a potentially lethal infection. Int J Infect Dis. 2009. May; 13(3): 327–33. PMID: 18952475. 10.1016/j.ijid.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6).Owens B.M., Schumann N.J. Ludwig's angina: historical perspective. J Tenn Dent Assoc. 1993. Jan; 73(1): 19–21. PMID: 8474245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7).Ross G.G. VII. Angina Ludovici. Ann Surg. 1901. Jun; 33(6): 720–5. PMID: 17860985. PMCID: PMC1425468. 10.1097/00000658-190101000-00069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8).Honrado C.P., Lam S.M., Karen M. Bilateral submandibular gland infection presenting as Ludwig's angina: first report of a case. Ear Nose Throat J. 2001. Apr; 80(4): 217–8, 222–3. PMID: 11338645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9).Hartmann R.W. Jr.. Ludwig's angina in children. Am Fam Physician. 1999. Jul; 60(1): 109–12. PMID: 10414632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10).Saifeldeen K., Evans R. Ludwig's angina. Emerg Med J. 2004. Mar; 21(2): 242–3. PMID: 14988363. PMCID: PMC1726306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11).Marcus B.J., Kaplan J., Collins K.A. A case of Ludwig angina: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2008. Sep; 29(3): 255–9. PMID: 18725784. 10.1097/PAF.0b013e31817efb24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12).Marra S., Hotaling A.J. Deep neck infections. Am J Otolaryngol. 1996. Sep-Oct; 17(5): 287–98. PMID: 8870932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13).Santos Gorjón P., Blanco Pérez P., Morales Martín A.C. et al. Deep neck infection. Review of 286 cases. Acta Otorrinolaringol Esp. 2012. Jan-Feb; 63(1): 31–41. PMID: 21820639. 10.1016/j.otorri.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14).Han X., An J., Zhang Y. et al. Risk factors for life-threatening complications of maxillofacial space infection. J Craniofac Surg. 2016. Mar; 27(2): 385–90. PMID: 26967077. PMCID: PMC4782818. 10.1097/SCS.0000000000002416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15).Kataria G., Saxena A., Bhagat S. et al. Deep neck space infections: a study of 76 cases. Iran J Otorhinolaryngol. 2015. Jul; 27(81): 293–9. PMID: 26788478. PMCID: PMC4710882. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16).Huang T.T., Liu T.C., Chen P.R. et al. Deep neck infection: analysis of 185 cases. Head Neck. 2004. Oct; 26(10): 854–60. PMID: 15390207. 10.1002/hed.20014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17).Yalamanchili S., Lau W.B. A curious case of cold Ludwig's angina. J Emerg Med. 2015. Oct; 49(4): e121–2. PMID: 26149804. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2015.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18).Patel M., Chettiar T.P., Wadee A.A. Isolation of Staphylococcus aureus and black-pigmented bacteroides indicate a high risk for the development of Ludwig's angina. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009. Nov; 108(5): 667–72. PMID: 19836722. 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19).Wang L.F., Kuo W.R., Tsai S.M., Huang K.J. Characterizations of life-threatening deep cervical space infections: a review of one hundred ninety-six cases. Am J Otolaryngol. 2003. Mar-Apr; 24(2): 111–7. PMID: 12649826. 10.1053/ajot.2003.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20).Yang R.H., Shen S.H., Li W.Y., Chu Y.K. Bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw complicated by Ludwig's angina. J Chin Med Assoc. 2015. Jan; 78(1): 76–9. PMID: 25074798. 10.1016/j.jcma.2013.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21).Caccamese J.F. Jr., Coletti D.P. Deep neck infections: clinical considerations in aggressive disease. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2008. Aug; 20(3): 367–80. PMID: 18603197. 10.1016/j.coms.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22).Bakir S., Tanriverdi M.H., Gün R. et al. Deep neck space infections: a retrospective review of 173 cases. Am J Otolaryngol. 2012. Jan-Feb; 33(1): 56–63. PMID: 21414684. 10.1016/j.amjoto.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23).Saifeldeen K., Evans R. Ludwig's angina. Emerg Med J. 2004. Mar; 21(2): 242–3. PMID: 14988363. PMCID: PMC1726306. 10.1136/emj.2003.012336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]