Abstract

The United States continues to grapple with an epidemic of opiate/opioid drugs. This crisis initially manifested itself in the use and abuse of opioid pain relievers and has since seen an increase in illicit opiate/opioid drug use mortality. Cuyahoga County (metropolitan Cleveland) has been an area where the crisis has been particularly acute; this paper updates our previous experience. Most notable in the evolution of the drug epidemic has been an increase in mortality associated with fentanyl and an alarming rise in overall deaths, largely attributable to the emergence of fentanyl (a 64% increase in total overdose deaths from 2015 to 2016, with fentanyl increasing 324%). Fentanyl is a synthetic opioid with use in medical analgesia and anesthesia; however, most of the current supply is of clandestinely manufactured origin. Also of concern is the recent appearance of illicit fentanyl analogues, which are briefly described in this report. White males continue to be the most frequent overdose victims in the current crisis. A decrease of age appears to have taken place with the emergence of fentanyl with the most common age group being between 30 and 44 years of age. The majority of decedents are nonurban residents. Educationally, most of these decedents have a high school diploma or less schooling and a significant percentage consists of manual laborers. Medical examiners are an important source of information necessary to develop prevention and interdiction strategies. Challenges faced regarding adequate funding, instrumentation, and staffing are being felt.

Keywords: Forensic pathology, Heroin, Fentanyl, Opioid, Cocaine, Epidemiology

Introduction

Many regions of the United States are in the midst of an epidemic of drug-related mortality, largely driven by opiates/opioids (O/O) (1-3). While this crisis appears to have its roots in the overprescribing of opioid pain relievers (OPR), more recent years have a seen a transition to illicit narcotics, primarily heroin and fentanyl (4-7). In a previous report, we documented our experience with the heroin epidemic in Cuyahoga County (metropolitan Cleveland) from 2007 through 2012 when this transition began (5). This paper provides an update to that report, with a focus on the evolution of drug abuse and mortality in our community through most of 2016, as the data were available at the time of writing. During this interval, the problem has significantly changed and, unfortunately, worsened greatly. Furthermore, in-depth examination of decedent information is also presented with suggestions as to possible public health interventions based on these data.

Methods

The Cuyahoga County Medical Examiner's Office (CCMEO) has a statutory responsibility to investigate all deaths that are unnatural, suspicious, or involve the sudden, unexpected death of a person in apparent good health. The possibility of a drug-related cause of death will initiate an investigation by CCMEO. Suspected drug-related deaths (DRD) with little or no medical intervention are transported to the mortuary for full autopsy. Deaths after hospitalization with adequate evaluation (e.g., negative computed tomography of the head) may be viewed with no autopsy. Where possible, toxicology testing on admission samples is conducted by the CCMEO Toxicology Laboratory. After full autopsy with routine histology and toxicology, deaths will be certified as drug-related when the sum of the investigation conducted by a board-certified forensic pathologist supports that determination. Barring intentional self-harm or overdose as a result of the direct actions of another person, manner of death is generally ruled accidental.

All DRD in our jurisdiction underwent intensive case review and from 2011 through the third quarter of 2016 (with full-year projections where appropriate), cases were analyzed for basic demographic information (i.e., age, gender, race) and residency status (i.e., urban vs. suburban). More recent years (2015 and 2016) were also analyzed for education level and occupation based on death certificate entries for these variables. The more recent DRD were further stratified by lethal intoxicant represented by heroin, fentanyl, cocaine, OPR, and all others. In our earlier study, we used oxycodone data as a surrogate for OPR, as this has been the major driver of OPR trends in our region (5). Data presented here include all OPR drugs. Additional analysis for mortality involving fentanyl analogues and U-47700 (a synthetic opioid-like analgesic and Schedule I controlled substance with an approximate potency of 7.5 times that of morphine) was also undertaken; however, this is a relatively small population (thus far) and a very recent development in our jurisdiction so more in-depth characterization has not yet been performed. All DRD were searched in the Ohio Automated Rx Reporting System (OARRS), the state prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP). Access to OARRS was initially granted to CCMEO in 2013, so 2012 data range in “look back” from six to 18 months. Otherwise all retrospective OARRS searches extend up to two years. In mid-2015, reporting to the OARRS system by prescribers and distributors changed from voluntary to mandatory.

Results

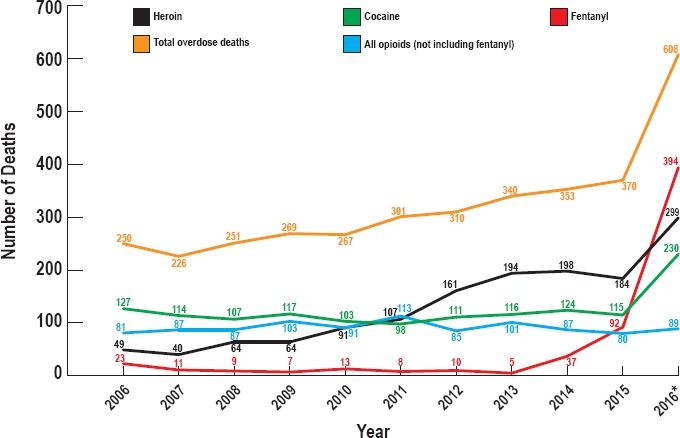

Total overdose mortality has increased over the last decade. From 2006 to 2014 (Figure 1), the total DRD increased from 250 to 353 (41%). Heroin-associated deaths increased in this time period from 49 to 198 (304%). Fentanyl-associated mortality did not show a significant rise until 2014, when 37 deaths were observed, primarily in the last two months of the year. Deaths associated with OPR and cocaine remained relatively unchanged through this time period. The chart shows total DRD as well as those by a particular associated substance. Each line includes all deaths associated with that individual drug, either alone or in combination with other drugs. However, most fatalities are polysubstance DRD and thus, are included in more than one line of the chart. Therefore, the categories represented are not mutually exclusive.

Figure 1.

Cuyahoga County overdose deaths 2006-2016, most common associated drugs. 2016 cases projected from 3rd quarter data based on ruled cases as of December 31.

In 2015, DRD showed only a modest increase (Figure 1) to 370 (5%) and heroin-associated deaths actually declined to 184 (-7%). Of note, however, the number of fentanyl deaths rose sharply to 92 (149%). Projections for 2016 show an acute worsening of the problem with projected increases in DRD (608, 64%), heroin-associated deaths (299, 62%), fentanyl-associated deaths (394, 328%), and cocaine-associated deaths (230, 100%). Rates for OPR have continued to remain relatively stable (Figure 1). Drug-related deaths not involving one of these four drugs fell from 47 in 2015 (13% of all DRD) to 20 through the third quarter in 2016 (4% of all DRD). In 2016, fentanyl analogues and U-47700 have been responsible for at least 50 deaths through the first three quarters of the year (Table 1). These drugs were not encountered in 2015. The major analogues seen have been carfentanil and acetylfentanyl. They are included in the general fentanyl totals for 2016.

Table 1.

Fentanyl Analogue Mortality, By Drug

| Analogues | Deaths through 2016 3rd Quarter |

|---|---|

| 3-Methylfentanyl | 4 |

| Acetylfentanyl | 32 |

| Carfentanyl or carfentanil | 23 |

| Despropionyl fentanyl (4-ANPP) | 3 |

| Furanylfentanyl | 6 |

| Other | |

| U-47700 | 2 |

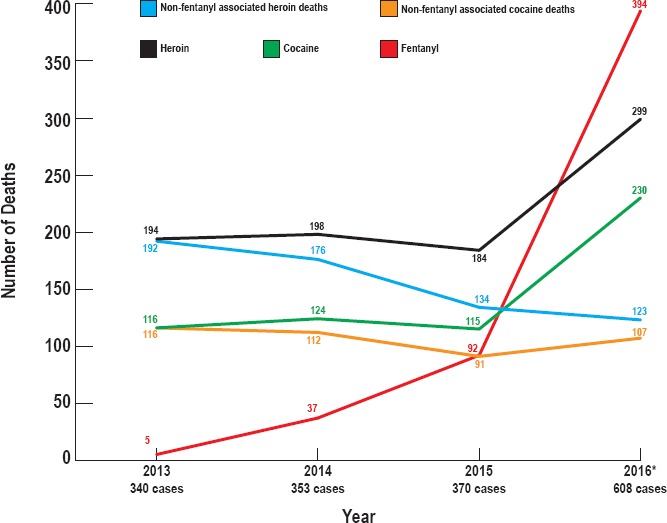

Deaths due to cocaine alone (Table 2) rose very little from 2015 to 2016 (42 in 2015 to a projection of 61 in 2016) while deaths from heroin alone appear to have fallen from 84 in 2015 to a projection of 57 for 2016 (32%). Deaths associated with fentanyl alone will likely triple from 2015 to 2016 (from 29 to a projection of 95 in 2016) and fentanyl is also present in most of the fatal mixed intoxications involving both heroin and cocaine. In 2016, combined heroin and fentanyl overdoses are projected to rise 343% (to a projected 111 from 25), combined cocaine and fentanyl overdoses by 522% (projected 57, up from just 9), and overdoses with all three present by 214% (projected 59 up from 14). Deaths from cocaine alone are projected to rise from 42 to 61 (19 in total). Cocaine cases associated with fentanyl or fentanyl and other O/O taken in aggregate, are projected to rise from 24 to 123 (99 cases), representing 86% of the projected 100% increase of all cocaine-associated deaths in 2016. The impact of fentanyl on increased overall cocaine and heroin mortality is summarized in Figure 2. Rising heroin mortality in 2016 displays a similar pattern (Figure 2).

Table 2.

Drug Overdose Deaths (2015 and 2016), By Drug

| Drug(s) | Drug Deaths 2015 | Drug Deaths 2016 (3rd Quarter) |

|---|---|---|

| Heroin alone | 84 | 43 |

| Drug-related deaths without Fentanyl, Heroin, Cocaine or Opioids | 47 | 20 |

| Cocaine alone | 42 | 46 |

| Opioids alone | 42 | 26 |

| Heroin + Cocaine | 37 | 23 |

| Fentanyl alone | 29 | 71 |

| Fentanyl + Heroin | 25 | 83 |

| Fentanyl + Heroin + Cocaine | 14 | 44 |

| Heroin + Opioids | 13 | 7 |

| Cocaine + Opioids | 10 | 9 |

| Fentanyl + Cocaine | 9 | 42 |

| Fentanyl + Heroin + Opioids | 8 | 8 |

| Fentanyl + Opioids | 6 | 11 |

| Heroin + Cocaine + Opioids | 3 | 2 |

| Fentanyl + Cocaine + Opioids | 1 | 4 |

| Fentanyl + Heroin + Cocaine + Opioids | 0 | 2 |

| Total | 370 | 441 |

Figure 2.

Cuyahoga County overdose deaths by year, drug and fentanyl contribution 2006-2016, most common associated drugs. 2016 cases projected from 3rd quarter data based on ruled cases as of December 31.

Of note, drug submissions in the seized drug chemistry laboratory involving mixtures of illicit substances rose from 183 in the first nine months of 2015 to 733 in the same time period on 2016 (300%). Fentanyl was detected in only 35% of the 2015 mixtures compared to 61% of the 2016 mixtures.

Cuyahoga County's population, according to the U.S. Census Bureau 2015 estimate (8), is made up of 52.4% female and 47.6% male, 64.2% Caucasian, 30.3% African American, 5.6% Hispanic, 21.4% aged under 18, and 16.8% aged 65 and over (Table 3). In 2015, DRD occurred predominantly in males (71%), whites (75%) with an equal number of deaths in the 30-44 and 45-60 age groups (35% and 36%, respectively). Through the first three quarters of 2016, the patterns are males (72%) and whites (81%). Age distributions have been generally similar. These demographics are similar to our previous experience (5). Deaths associated with cocaine alone were the only group to show a non-white racial majority with 71% of these decedents being African-American. Deaths among fentanyl users (alone and mixed) showed a shift toward younger ages in 2016, with nearly 40% being between 30 and 44 years old and near equal percentages (24.6%) for ages less than 30 years and between 45 and 60 years (27.5%). Residency of decedents showed an approximately even divide between Cleveland and the remainder of Cuyahoga County, but factoring in DRD from out of county residents (primarily nonurban adjacent counties) produced a majority of suburban resident deaths (55% to 45%) that has remained consistent throughout the previous five years. By identified occupation, approximately 25% were manual laborers (e.g., construction, repair, or production-type employment) but examination of occupations reported on death certificates revealed that approximately one-third were either unknown or too vague to permit classification. The highest attained educational level for the majority of DRD decedents was a high school diploma or less (70%).

Table 3.

General Population and Selected Drug Overdose Demographics (U.S. Census Data, 2015 Est. [8])

| General Population Demographics | Percentage | Drug-Related Deaths Demographics | Heroin-Related Deaths | Fentanyl-Related Deaths | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cuyahoga County Total | 1255 921 | 2015 | 2016 | 2015 | 2016 | 2015 | 2016 | |

| City of Cleveland | 388 072 | 30.90% | 43.24% | 45.12% | 44.26% | 41.51% | 42.70% | 44.85% |

| Suburban Cuyahoga | 867 849 | 69.10% | 45.14% | 42.40% | 43.72% | 45.75% | 43.82% | 44.49% |

| Male | 47.60% | 70.81% | 71.66% | 74.86% | 70.28% | 69.57% | 72.43% | |

| Female | 52.40% | 29.19% | 28.34% | 25.14% | 29.72% | 35.14% | 27.57% | |

| White | 64.20% | 74.86% | 80.73% | 83.06% | 89.62% | 74.16% | 87.87% | |

| Black | 30.30% | 24.59% | 18.59% | 15.85% | 9.91% | 25.84% | 12.13% | |

| Asian | 3.10% | 0.54% | 0.45% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | |

| Other | 2.40% | 0.00% | 0.23% | 1.09% | 0.47% | 0.00% | 0.00% | |

| Hispanic | 5.60% | 3.51% | 2.72% | 5.46% | 3.30% | 3.37% | 2.94% | |

| Age 18 under | 21.40% | 0.54% | 0.91% | 1.09% | 1.42% | 1.12% | 1.10% | |

| 19-29 | 15.96% | 18.11% | 18.59% | 23.50% | 23.58% | 24.72% | 23.53% | |

| 30-44 | 17.97% | 35.14% | 32.65% | 40.44% | 33.49% | 38.20% | 39.34% | |

| 45-59 | 21.19% | 35.68% | 36.51% | 26.78% | 30.66% | 30.34% | 27.57% | |

| 60+ | 23.50% | 10.54% | 11.34% | 8.20% | 10.85% | 3.37% | 8.46% | |

The percentage of decedents with an OARRS report are listed in Table 4. Data shown for 2015 and 2016 are from the first four months of each year to permit an analysis of the efficacy of mandatory reporting.

Table 4.

| Year | Percentage of Decedents With Report |

|---|---|

| 2012 | 64 |

| 2013 | 73 |

| 2014 | 59 |

| 2015 | 48 |

| 2016 | 71 |

Limited look back in 2012 (6-18 months), all other years: 24 months.

Fentanyl data included since 2014

2015 and 2016 data include only first four months (see text)

The OARRS trend is generally downward through 2015 (from a high of 73% in 2013 to 48% in following years) but improves back to earlier levels (71% in 2016) with the implementation of mandatory reporting. Of note, approximately one-third of the 2016 reports were of only three months duration or less prior to death.

Discussion

The latest epidemic of drug-related deaths in the United States involves O/O and had its genesis in OPR (3, 4, 6). The problem evolved from OPR deaths to an explosive rise in illicit drug mortality, primarily heroin and in recent years, in clandestinely manufactured fentanyl. More immediately (especially the last six months of 2016), ever more potent analogues of fentanyl have been identified in Ohio (9) and in our jurisdiction specifically.

Our county data show a significant rise in heroin-associated mortality through 2013 with a leveling off in the following two years before a substantial rise in 2016. Fentanyl mortality has risen steadily since late 2014, with a sharp increase in 2016 (Figure 1). An earlier, minor spike in fentanyl mortality in 2006 was related to diversion of legal fentanyl, primarily in the form of transdermal patches. Opioid pain reliever deaths have not changed significantly in the last decade. This was also true of cocaine deaths until 2016, where they are projected to double. The data further show that the increases in heroin and cocaine mortality are largely driven by lethal mixed intoxications where fentanyl is also present (Figure 2/Table 2). The substantial rise in drug mixtures (300% from 2015 to 2016) analyzed in the Crime Laboratory Seized Drug Chemistry Unit, with the most significant rise being in fentanyl mixtures, indicates that the upward trend in DRD involving these three leading drugs is most likely a reflection of increased fentanyl availability and mortality. The potency of fentanyl is approximately 10 to 20 times that of heroin, and cocaine is not a narcotic but abused for its stimulant properties. Our data indicate that the introduction of fentanyl into addict populations where mortality was stable (cocaine) or appeared to be stabilizing (heroin) has resulted in rises in cocaine and heroin mortality that are likely the manifestation of a skyrocketing fentanyl death rate rather than independent phenomena. Stated another way, heroin and cocaine mortality appear to be rising in our jurisdiction but it is likely that the abuse of these substances has not changed much; rather, the populations where they have been abused are now being exposed to more lethal mixtures of drugs (i.e., fentanyl) and mortality is trending upward because of the presence of this more lethal newcomer.

The recent appearance of fentanyl analogues in our jurisdiction (Table 1) and elsewhere has been associated with spikes in mortality (9). Many of these drugs (e.g., 3-methylfentanyl, carfentanil) have potencies well beyond fentanyl itself (anywhere from 4- to 120-fold for 3-methylfentanyl and 10- to 200-fold for carfentanil) and are a concern for even further worsening of the mortality trends. These drugs have also placed a burden on our laboratory both in detection and identification. With required limits of detection in the picogram per milliliter range for some of these compounds, it has been challenging to quantify them; lower concentrations also permit them to escape detection in routine screening tests. The identification of the analogues (and the procurement of appropriate standards) is another, often time-consuming, challenge for a laboratory already overburdened by the sheer volume of casework resulting from the overdose epidemic. It should be noted that if these analogues, especially the more potent 3-methylfentanyl and carfentanyl, follow the same explosive growth trend of fentanyl as seen from November 2014 through 2016, we would fully expect fatality rates to continue rising due to the deadly potency of these newer synthetic opioids.

A look at the DRD victims reveals that gender, racial, and urban/suburban characteristics have remained similar. A trend toward younger ages has been noted with fentanyl, and a similar trend in all DRD has been detected but may again be driven by fentanyl's prominence in mixed drug intoxications. This shift may suggest the need for different strategies in public health interventions, particularly messaging to access the target audience.

Data from the OARRS registry are difficult to interpret because of changes in the program over the study period. Prior to mandatory reporting in OARRS, the general trend was downward with regard to the percentages of fatal illicit drug overdose victims who could be shown to have received a legal prescription for a controlled substance, most often OPR (Table 4). That raises an alarming possibility that addicts may be circumventing the previously well-established progression route from OPR to illicit drugs like heroin and fentanyl. Mandatory OARSS reporting saw a return to the higher percentages of illicit drug overdose victims with a history of legal OPR access, but the observation that a significant number of these addicts did not have a lengthy history (less than three months prior to death) in the legal health care system is troubling. While a PDMP cannot distinguish between the addicts who follow the route from OPR to heroin, and the addicts who use OPR and illicit drugs interchangeably, this trend raises concern that the current mitigation strategy of physician education in O/O prescribing practices and the use of PDMPs to identify at risk populations (10) may prove ineffective in reaching a significant subset of addicts. It will be essential to monitor this trend going forward as these mitigation strategies are viewed as cornerstones in the public health response. If this subset of illicit drug users largely bypasses the health care system in their descent into addiction, they will not benefit from either changes in prescribing practices or OPR surveillance. It would be helpful to see if other jurisdictions, which did not see PDMP reporting fluctuations like we did over our study period, could confirm this downward trending and/or short duration of participation in the health care system. A population with minimal or no interaction with the health care system on the road to narcotic addiction will not benefit from OPR regulation or PDMP monitoring and will require different prevention strategies to be implemented.

Our data show a majority of fatal overdose victims achieve a final education level of a high school diploma or less. Occupational information indicates that at least one-quarter of the DRD decedents work or have worked in manual labor type occupations, which is all the more significant since a third of all decedents could not even be classified with regard to occupation based on death certificate information. The lack of advanced educational degrees may predict a higher level of manual laborers, who may in turn be more likely to suffer job-related injuries and subsequent treatment/overprescribing with OPR. These data support early educational efforts in schools and indicate that trade organizations and/or labor unions may be a productive partner in intervention efforts.

Conclusion

One clear lesson from the Cuyahoga County experience has been the critical role that the medical examiner's office can play in this epidemic. As an agency that is on the front lines of documenting the increase in DRD, our data are very close to real time and fill a gap in traditional public health approaches relying on aggregated death certificate data, which often lag behind by several to a few years. Our experience has shown that we are dealing with a crisis that has evolved rapidly in the emergence of fentanyl and now the fentanyl analogues. Thus, medical examiner data can potentially impact prevention efforts in a meaningful way because of the more timely nature of the information. We would also encourage health departments to engage their local death investigation agency (medical examiner or coroner) to access this “closer-to-real-time” information in addition to their larger aggregate data efforts. This information is also of considerable value to law enforcement in their efforts as well. With the Crime Laboratory under the direction of the Medical Examiner in our jurisdiction, we have been fortunate to be able to facilitate frequent interactions between them and the Toxicology Laboratory (also under Medical Examiner direction), two critical players in any epidemic of DRD. Both laboratories have generated valuable information for the other and we would strongly encourage those jurisdictions where administrative control of these two laboratories is separate to explore options to encourage information sharing in a regular and timely manner. Funding and primary service responsibilities may limit the role such agencies can play in this effort (particularly in the time of an epidemic) but the quality and timeliness of their information should make the solution of these limitations a priority.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Dr. Allison P. Hawkes for her contribution to data acquisition and analysis.

Footnotes

ETHICAL APPROVAL

As per Journal Policies, ethical approval was not required for this manuscript

STATEMENT OF HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

This article does not contain any studies conducted with animals or on living human subjects

STATEMENT OF INFORMED CONSENT

No identifiable personal data were presented in this manuscsript

DISCLOSURES & DECLARATION OF CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors, reviewers, editors, and publication staff do not report any relevant conflicts of interest

References

- 1.Calcaterra S., Glanz J., Binswanger I. National trends in pharmaceutical opioid related overdose deaths compared to other substance related overdose deaths: 1999-2009. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013. Aug 1; 131(3): 263–70. PMID: 23294765. PMCID: PMC3935414. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Vital signs: overdoses of prescription opioid pain relievers- United States, 1999-2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011. Nov 4; 60(43): 1487–92. PMID: 22048730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Warner M., Trinidad J.P., Bastian B.A. et al. Drugs most frequently involved in drug overdose deaths: United States, 2010-2014. Natl V ital Stat Rep. 2016. Dec; 65(10): 1–15. PMID: 27996932. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dasgupta N., Creppage K., Austin A. et al. Observed transition from opioid analgesic deaths to heroin. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014. Dec 1; 145: 238–41. PMID: 25456574. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gilson T., Herby C., Naso-Kaspar C. The Cuyahoga County heroin epidemic. Acad Forensic Pathol. 2014. Mar; 4(1): 109–13. 10.23907/2013.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rudd R.A., Aleshire N., Zibbell J.E., Gladden R.M. Increases in drug and opioid overdose deaths: United States, 2000-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016. Jan 1; 64(50-51): 1378–82. PMID: 26720857. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6450a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gladden R., Martinez P., Seth P. Fentanyl law enforcement submissions and increases in synthetic opioid-involved overdose deaths - 27 states, 2013-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016. Aug 26; 65(33): 837–43. PMID: 27560775. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6533a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.U.S. Census Bureau [Internet]. Washington: U.S. Census Bureau; c2017. American FactFinder: Annual estimates of the resident population for selected age groups by sex for the United States, States, Counties and Puerto Rico Commonwealth and Municipios: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015; 2016 Jun [cited 2017 Jan 2]. Available from: https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?src=bkmk. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Healy J. Drug linked to Ohio overdoses can kill in doses smaller than a snowflake. New York Times [Internet]. 2016. Sep 5 [cited 2017 Jan 2]. Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/2016/09/06/us/ohio-cincinnati-overdoses-carfentanil-heroin.html. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dowell D., Haegerich T.M., Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain - United States, 2016. JAMA. 2016. Apr 19; 315(15): 1624–45. PMID: 26977696. 10.1001/jama.2016.1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]