Abstract

As drug- and opiate/opioid-related deaths continue to rise in the Midwest, we must look at how the type of death investigation in these areas is affected and taxed by the increase. Many states with a large rural component rely on a local coroner system, where death investigation lacks uniformity and requirements for coroner investigative personnel are extremely variable. This has mixed implications for communities and potentially affects law enforcement and prosecution, data collection, and public policy. Both coroner and medical examiner systems benefit from strong leadership, properly trained personnel, and fiscal support. However, operational differences amongst jurisdictions should be addressed so that all stakeholders ultimately receive optimal data. This paper discusses the coroner system of death investigation in one Midwest state (Ohio) in the context of the region's burgeoning opiate/opioid epidemic and suggests opportunities for improvement.

Keywords: Forensic pathology, Opiates, Opioids, Coroners, Medical examiners, Ohio

Introduction

The Rust Belt and Opiates/Opioids

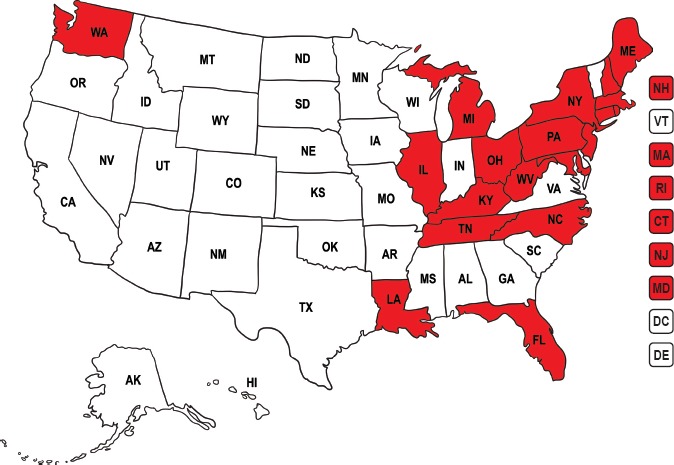

Since the year 2000, the number of opiate/opioid-related drug overdose deaths has increased significantly (200%), with several states showing a sharp increase. Regions such as New England and the Midwest have been affected particularly hard (Figure 1) (1). Both regions have seen an increase in the number of synthetic opioid overdoses (especially fentanyl), but the Midwest, and in particular Ohio, has seen a local acute rise in those that are novel and increasingly toxic, such as carfentanil, which is roughly 100 times more potent than fentanyl, 10 000 times more potent than morphine, and often arrives from illicit overseas shipments (2).

Figure 1.

States (in red) denoting a statistically significant increase in drug overdose death rates from 2014 to 2015. Adapted from (11) utilizing “Cartoon USA map” vector image used under license from www.shutterstock.com.

A multifactorial problem, opiate addiction has been attributed to physician over-prescription, either in response to treating the “fifth vital sign” and the hospital performance measurements attached to that (3, 4), or having been falsely reassured that opiates were non-addictive (5-8), or drug company misconduct (e.g., aggressive marketing; wholesale, targeted mega-shipments [9, 10]). Combined with an influx of potent and cheap street synthetics and semisynthetics and stricter prescribing regulations, many opioid users have found themselves in dangerous and ever-evolving drug territory.

Coroner System in Ohio

The state of Ohio has a mixed medical examiner/coroner (ME/C) system, but with a coroner predominance; of its 88 counties, 86 are overseen by its own independently elected coroner (12). The two remaining counties, Cuyahoga and Summit, have medical examiner's offices, headed by forensic pathologists as appointed by their county's charter government; both are relatively recent conversions from the coroner system (2009 and 1997, respectively) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Counties served by coroners (no color) versus medical examiner (yellow).

The other counties maintaining a county coroner, who, as stated by Ohio Revised Code (ORC), are required to be physicians (MD or DO) of any specialty, licensed in the state of Ohio for at least two years prior to assuming the position, and reside within the county they serve (13). Coroners are elected to four-year terms, and there are no term limits. Requirements prior to taking office include 16 hours of continuing education through the state's Coroner association, as well as 16 hours within 90 days of taking office. Throughout the four-year term, an additional 32 hours are required. Ohio Revised Code mandates that cause of death (COD) and manner of death (MOD) are to be determined by the coroner (13).

Many counties staffed by a nonpathologist or nonforensic pathologist (FP) coroner often contract with a neighboring county that can provide autopsy services. Coroners without an FP often triage cases, sending only suspicious cases for autopsy while the coroner or his/her investigator/designee performs external exams on the remaining cases. Most FPs are located within major cities and as such, the surrounding counties benefit from their proximity (14) (Figure 3). Counties contracting with other counties is often fluid, as resources, funding, or other extenuating circumstances require the shift. Moreover, some counties on the border of Ohio cover Indiana, Michigan, and Pennsylvania coroner counties. Some individual counties contract with two or more counties for autopsy service coverage.

Figure 3.

Regional service provided by forensic pathologists (FP): Counties like Montgomery [15] (in pink), Lucas (purple), Cuyahoga (in yellow), Franklin (blue), Hamilton (grey), Licking (dark green), Summit (in green) Stark (in orange) provide regional service, covering their home counties in addition to surrounding counties. Counties not colored in are contracted with two or more counties. Lorain (light orange), Mahoning (red), and Trumbull (dark purple) cover only themselves. These counties employ only one FP and rely on other counties for coverage when the FP is unavailable.

With the overwhelming increase in opiate/opioid-related deaths, many regional offices with FPs, already taxed by an increased number of drug overdoses within their own counties, have declined to continue contracting with nearby counties to provide autopsy services for drug-related deaths. These counties have either found other, often farther away counties with whom to contract or have decreased the number of overdose cases sent for autopsy.

The epidemic has stretched many jurisdictions’ resources and finances, but the coroner system in Ohio (and subsequently, thorough death investigation) may find itself particularly vulnerable, as larger forensic centers decline autopsy coverage. Local coroners have increasingly been asked to assume more complex duties of death investigation with minimal additional training.

Discussion

The baseline pros and cons of medical examiner and coroner systems have been previously discussed in other journal reviews (16), and that discussion is relevant to the roles that these individuals can play in the opioid/opiate epidemic. Looking at the coroner system in Ohio, there are advantages and limitations with regard to the roles that they may play in death investigations and public policy surrounding the drug epidemic.

The Coroner's Role- Advantages

Intrinsic forces that assist the coroner include political influence, which, as discussed below, can be a double-edged sword. With an intelligent, politically active leader, funds can be secured and political alliances forged in the interest of the office's mission, particularly in times of a public health crisis like the opioid epidemic. As an elected official, the coroner is already established in the political landscape and frequently is seen, both by the public and other elected officials, as a medical source expert with regard to issues of mortality. Public support or even discord can work favorably for the office, as public pressure can provide an additional motivation for not just the coroner, but also those in charge of funding the coroner. Politically engaged coroners may be able encourage change in their offices and communities more effectively than a politically disengaged or disinterested medical examiner.

Several coroner's offices directly employ multiple forensic pathologists, some of whom make cause and manner of death determinations upon which the coroner will sign off unchanged.

Extrinsic forces that assist the coroner include election cycles that can provide the community an opportunity to replace subpar leadership or, conversely, ensure continued successful leadership for a set period of time. A forward thinking coroner can run on a platform of opiate awareness.

The Coroner's Role- Limitations

Intrinsic barriers to the coroner investigation refer to those deficiencies inherent to investigations and investigators where training and experience diverge from national standards.

Coroners legally tasked with determination of cause and manner of death may lack formal exposure to proper death certificate phraseology, training in toxicology report interpretation, and other forensic skill sets beyond the basic instruction they receive when they are elected. Some shortcomings these deficiencies may produce include: “laundry list/kitchen sink” approach to death certification, where all drugs positive in the toxicology report are listed; errors of interpretation including failing to identify codeine as a natural occurrence in the poppy plant from which heroin is derived as opposed to an admixed intoxicant; failing to identify additional lethal intoxicants with further toxicologic testing (e.g., fentanyl analogues) or misattributing the COD to another drug or condition when low levels of harmful illicit drugs are present; or generalization of COD with “multi-drug intoxication” or “drug abuse” without specifying the drug(s) involved. Ohio in particular struggled with death certificate uniformity for drug overdoses, as many coroners did not specifically identify individual drugs on the death certificate, relied solely on hospital record urine screens when admission blood was available for testing, or interchangeably used of the words opiates and opioids, with no distinction between the morphine class and synthetic/semisynthetic derivatives.

For autopsy cases, coroners legally tasked with determination of COD/MOD will take into consideration the FPs report findings, but may find it expedient to reject these findings for a variety of nonscientific reasons. The nature of the coroner's office is political, and as such, is susceptible to political influence or even grandstanding. For example, a coroner in Pennsylvania has begun ruling all overdose deaths as “homicides” in a misguided attempt to draw attention to the overdose epidemic (17). Others might bend to the will of his/her constituents and their families for political harmony, choosing to ignore findings on MOD or even COD.

For autopsy cases, FPs may not receive adequate information prior to the autopsy, which may affect the direction of the autopsy (e.g., special procedures, collection of additional specimens/evidence).

Some jurisdictions may not have their own independent investigator and may solely rely on police reports. Law enforcement not specifically trained may overlook or misinterpret death scenes where drugs may have a played a role.

Some jurisdictions may employ an independent investigator, who may not have had any prior experience, and thus may not be properly trained to triage cases, attend death scenes, or in some cases, perform external examinations.

Extrinsic barriers to the coroner investigation are not dissimilar to some ME offices, but given the nature of small, rural communities, they face issues not seen in larger jurisdictions.

For example, in a rural Ohio county serving roughly 43 000 people, the commissioners allotted the county coroner only three autopsies per year. Remaining cases receive either external examination only or are certified based on medical record review. Ruling drug-related deaths without an autopsy is not endorsed by the National Association of Medical Examiners (18). This practice is not limited to coroner offices; many jurisdictions in Ohio and elsewhere have found it necessary to adopt similar practices due to caseload. The failure to perform an autopsy coupled with a potentially inadequate death scene investigation can only be expected to produce an unacceptable level of erroneous death certifications.

Toxicology itself is often sent out to national laboratories instead of local or in-house labs, with steeper associated costs. The coroner may have to weigh individual tests against cost-benefit in the name of accuracy: does s/he chase 6-monoacetylmorphine in the urine to confirm a heroin overdose? Is an expensive test for carfentanil needed in a person who is already identified as being positive for fentanyl and heroin, but died during a local carfentanil outbreak?

Real-time drug overdose reporting is optimal but difficult for most ME/C offices given the lag inherent to comprehensive toxicology testing. However, smaller, underfunded offices often do not have the software or personnel for timely statistical analysis and dissemination. Public policy and prevention strategy development are thus undermined by inadequate data.

In a jurisdiction with lack of manpower or office space, or rural/travel constraints, toxicology may be drawn on scene, with immediate body release. Interim specimen storage may be subpar.

The Coroner's Role and the Medical Examiner's Role

The end game in the opiate epidemic for the ME/C is ultimately data: who is dying from what, and when, and where, and why? On a national level, identification and analysis of fatal epidemics rely heavily on data culled from death certificates. However, if the root source of data is flawed, this leads to uneven analysis and incorrect conclusions, affecting how those in health care and government approach epidemics and, more importantly, structure aid and resources.

As such, it is imperative that there is some degree of uniformity in the wording of cause of death. This is assuming the investigations to be equal, which may not be the case for aforementioned reasons. Unfortunately, ME/C's cannot control how that data is further processed, however. Reliance on ICD-10 coding of cause of death has somewhat affected how the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports. In a recent study where CDC researchers utilized not only the cause of death, but also “Part II/Contributory factors” and “How injury occurred” boxes on the death certificate, they found that while the top ten abused drugs did not change, their order of prevalence did (19).

Conclusion

In any system, there will never be a perfect death investigation. But the goal is to change what we can to minimize errors on our end. Many changes that would even out a patchwork death investigation system require legislative progressiveness; this sort of change, while welcome, is often cumbersome and slow. As it were, many coroner systems already function similar to regional statewide medical examiner system where several counties’ autopsy services are covered by forensic pathologists or even by an adjacent sovereign medical examiner's office. States like California have recently passed legislation to further ensure uniform death investigation, eliminating redundancy and ensuring competency, for example, by allowing forensic pathologists as opposed to lay coroners to rule on cause and manner of death (20).

Expansion and continuation of education for ME/Cs is imperative for the continued evolution of death investigation. Resources are available for self-education on certifying drug-related deaths (21); local and national professional meetings have offered programs and lectures on the importance of thorough death investigation. Open lines of communication between adjacent counties, cities, and states can allow for exchange of information and trends, and the opportunity to develop consistent investigative practices. Continued education of those not directly working for an ME/C office (e.g., prosecutors, public health agencies, county commissioners or finance directors) is also vital, as it is difficult to advocate for change where there is a fundamental misunderstanding of the job duties and requirements. Likewise, education and consistent communication between prosecutorial elected officials and the ME/Cs can help align expectations in drug death investigations and prosecutions. A prosecutor must understand the limits of an external exam only with toxicology, as the possibility of competing causes of death, or nuance in toxicological testing and interpretation requires a full autopsy for a thorough and accurate COD. Failure to comprehend this necessity can lead to political budgetary antagonism, or at worst, miscarriages of justice.

But ultimately, to effect real change, proper support, resources, and money must be allocated to both big cities and rural districts. The best, most educated coroner cannot effectively perform the job if s/he is the only person serving the county, an all too common occurrence.

As we encounter new drugs, we must consider new tools and ways of investigating. We must assess and reassess our current approaches both in the autopsy room and in the community. We must continue to educate ourselves and those directly/indirectly involved with our offices. We must advocate for appropriate resources for competent death investigation. Finally, we must push for widespread accreditation for both coroner and medical examiner offices, as accreditation is the first step to ensuring competency, and can be used to leverage appropriate funding.

The focus of the article is local to Ohio, and as such, specific to Ohioans and Ohio law. Though many other jurisdictions struggle with the same issues as Ohio, it would be a worthy exercise to investigate the practices of other locales where the elected coroner requires no formal medical, forensic, or even basic educational level, training or continuing education to hold office.

Fatal opiate/opioid overdoses are increasing at an alarming rate. The data that we as forensic professionals collect are instrumental in identifying the drugs harming the community, and we in turn share our findings to the interested parties in the community and government at large. It is imperative that this data is uniform, specific, and accurate.

Footnotes

ETHICAL APPROVAL

As per Journal Policies, ethical approval was not required for this manuscript

STATEMENT OF HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

This article does not contain any studies conducted with animals or on living human subjects

STATEMENT OF INFORMED CONSENT

No identifiable personal data were presented in this manuscsript

DISCLOSURES & DECLARATION OF CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors, reviewers, editors, and publication staff do not report any relevant conflicts of interest

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE The authors have indicated that they do not have financial relationships to disclose that are relevant to this manuscript

References

- 1.Rudd R.A., Aleshire N., Zibbell J.E., Gladden R.M. Increases in drug and opioid overdose deaths — United States, 2000–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016. Jan 1; 64(50-51): 1378–82. PMID: 26720857. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6450a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kinetz E., Satter R. Ohio is hardest hit by Chinese carfentanil trade, logging 343 of more than 400 seizures in U.S. Akron Beacon Journal/Ohio.com [Internet]. 2016. Nov 3 [cited 2017 Jan 3]; Local news: [about 2 screens]. Available from: http://www.ohio.com/news/local/ohio-is-hardest-hit-by-chinese-carfentanil-trade-logging-343-of-more-than-400-seizures-in-u-s-1.724486. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanks S. The law of unintended consequences: when pain management leads to medication errors. P T. 2008. Jul; 33(7): 420–5. PMID: 19750120. PMCID: PMC2740947. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The Joint Commission [Internet]. Oakbrook Terrace (IL): The Joint Commission; c2017. Joint Commission statement on pain management; 2016. Apr 18 [cited 2017 Jan 3]. Available from: https://www.jointcommission.org/joint_commission_statement_on_pain_management/. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Plea agreement: United States of America v. The Purdue Frederick Company, Inc. 2007. May 10 [cited 2017 Jan 3]. Available from: http://graphics8.nytimes.com/packages/pdf/business/20070510_DRUG_Purdue.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meier B. In guilty plea, OxyContin maker to pay $600 Million. New York Times [Internet]. 2007. May 10 [cited 2017 Jan 3]. Available from: http://www.nytimes.com/2007/05/10/business/11drug-web.html. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Porter J., Jick H. Addiction rare in patients treated with narcotics. N Engl J Med. 1980. Jan 10; 302(2): 123 PMID: 7350425. 10.1056/nejm198001103020221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Portenoy R.K., Foley K.M. Chronic use of opioid analgesics in nonmalignant pain: report of 38 cases. Pain. 1986. May; 25(2): 171–86. PMID: 2873550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dhalla I.A., Persaud N., Juurlink D.N. Facing up to the prescription opioid crisis. BMJ. 2011. Aug 23; 343: d5142 PMID: 21862533. 10.1136/bmj.d5142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eyre E. Drug firms poured 780M painkillers into WV amid rise of overdoses. West Virginia Gazette Mail [Internet]. 2016. Dec 17 [cited 2017 Jan 3]. Available from: http://www.wvgazettemail.com/news-health/20161217/drug-firms-poured-780m-painkillers-into-wv-amid-rise-of-overdoses. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; c2017. Drug overdose death data; 2016. [updated 2016 Dec 16; cited 2017 Jan 3]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/data/statedeaths.html. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; c2017. Coroner/medical examiner laws; 2014. Jan 1 [cited 2017 Jan 3]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/phlp/publications/coroner/ohio.html. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ohio Revised Code. Available from: http://codes.ohio.gov/orc/313 Ohio Revised Code.

- 14.County Advisory bulletin, September 2016 [Internet]. County Commissioners Association of Ohio. Columbus: County Commissioners Association of Ohio; 2016. Sep [cited 2017 Jan 3]. Available from: https://www.ccao.org/userfiles/CAB%202016-06%20%209-26-16.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Montgomery County Coroner's Office [Internet]. Dayton (OH): Montgomery County; c2016. Contractual autopsy services; [cited 2017. Jan 3]. Available from: http://www.mcohio.org/government/elected_officials/coroner/contractual_autopsy_services.php. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanzlick R.L., Fudenberg J. Coroner versus medical examiner systems: can we end the debate? Acad Forensic Pathol. 2014. Mar; 4(1): 10–7. 10.23907/2014.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beauge J. Heroin overdoses will now be considered homicides, coroner says. Penn Live [Internet]. 2016. Mar 23 [updated 2016 Jun 22; cited 2017 Jan 3]. Available from: http://www.pennlive.com/news/2016/03/lycoming_county_coroner_listin.html. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davis GG; National Association of Medical Examiners and American College of Medical Toxicology Expert Panel on Evaluating and Reporting Opioid Deaths. National Association of Medical Examiners position paper: recommendations for the investigation, diagnosis, and certification of deaths related to opioid prugs. Acad Forensic Pathol. 2013. Mar; 3(1): 77–83. 10.23907/2013.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Warner M., Trinidad J.P., Bastian B.A. et al. Drugs most frequently involved in drug overdose deaths: United States, 2010-2014. Natl Vital Stat Rep [Internet]. 2016. Dec [cited 2017 Jan 3]; 65(10): 1-15. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr65/nvsr65_10.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.California Legislative Information [Internet]. Sacramento: State of California; c2017. SB-1189 Postmortem examinations or autopsies: forensic pathologists; [cited 2017. Jan 3]. Available from: https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billCompareClient.xhtml?bill_id=201520160SB1189. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Medical examiners’ and coroners’ handbook on death registration and fetal death reporting. Hyattsville (MD): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2003. Apr [cited 2017 Jan 3]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/misc/hb_me.pdf. [Google Scholar]