Abstract

Congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) is an uncommon condition in which the embryological elements of the diaphragm fail to fuse completely, leaving a defect in the barrier separating the thorax from the abdomen. Although most cases are symptomatic at birth and lead to prompt treatment, asymptomatic cases may go undetected, presenting later on as a result of sudden or exacerbated herniation of abdominal contents into the thoracic cavity. Presented here is the sudden death of a 6-week-old girl. At autopsy, the abdominal organs were found to be filling the left chest cavity, having herniated through a previously undetected posterior diaphragmatic hernia of Bochdalek. The literature on CDH is reviewed, including discussion of the embryological origin, clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment of the condition. Special emphasis is placed on the challenges posed by these late-presenting cases, particularly in their diagnosis and management, highlighting the importance of developing more direct methods of detection for these very reasons.

Keywords: Forensic pathology, Sudden infant death, Congenital diaphragmatic hernia, Bochdalek hernia, Respiratory compromise

Introduction

Congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) is an uncommon condition in which the components of the diaphragm fail to completely form or fuse during embryological development, resulting in a communication between the thoracic and abdominal cavities. Although most cases are symptomatic at birth, some patients are asymptomatic until such time as there is spontaneous or exacerbated herniation of the abdominal viscera into the thoracic cavity. These late-presenting cases pose a significant challenge to clinicians regarding diagnosis and management, particularly when the situation is emergent and thus has the potential to be rapidly fatal. The following is the case report of a 6-week-old girl, accompanied by a review of the literature on CDH. Particular emphasis is placed on late-presenting cases, their pathophysiology, and their complications. The implications of these cases for current screening practices and the need for more direct methods of detection of CDH are discussed.

Case Report

History

The decedent was a 6-week-old girl who was born prematurely at 37 weeks gestational age; she was delivered by Caesarian section because of maternal hypertension—the only known complication of the pregnancy. Over the course of three visits to her pediatrician between the first week after her birth and the day before her death, repeated physical examinations were unremarkable. After an unexplained initial (150 g) weight loss during the first week after hospital discharge, she appeared to do well, progressing from the 9th percentile for length at birth to the 13th over the next five weeks. On the day of her death, the decedent's mother reported breastfeeding the baby, after which she burped the child. She then noticed a rapid change in the decedent's breathing, with the breaths becoming labored or gasping, with a grunting sound. The mother took the baby to the home of her sister, a nurse, five minutes away. The sister was away, but returned a few minutes later to find the mother hysterical because the baby wasn't breathing. Noting the decedent to be blue, she immediately began cardiopulmonary resuscitation and called 911. Resuscitation attempts were unsuccessful and the baby was pronounced dead approximately one hour later at a local emergency room.

Autopsy Findings

Postmortem radiographs revealed a large walled bubble in the left side of the chest, apparently displacing the heart and thymus towards the right (Image 1). A lateral view reveals extensive compression of the left lung.

Image 1.

Anteroposterior postmortem radiograph of trunk. The stomach, distended by air, fills the left chest cavity, displacing mediastinal structures toward the right (arrow).

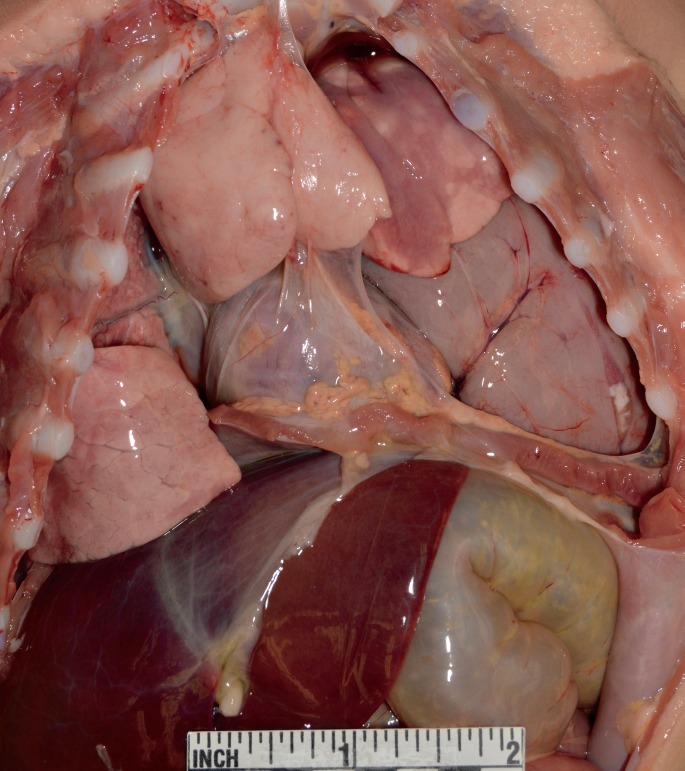

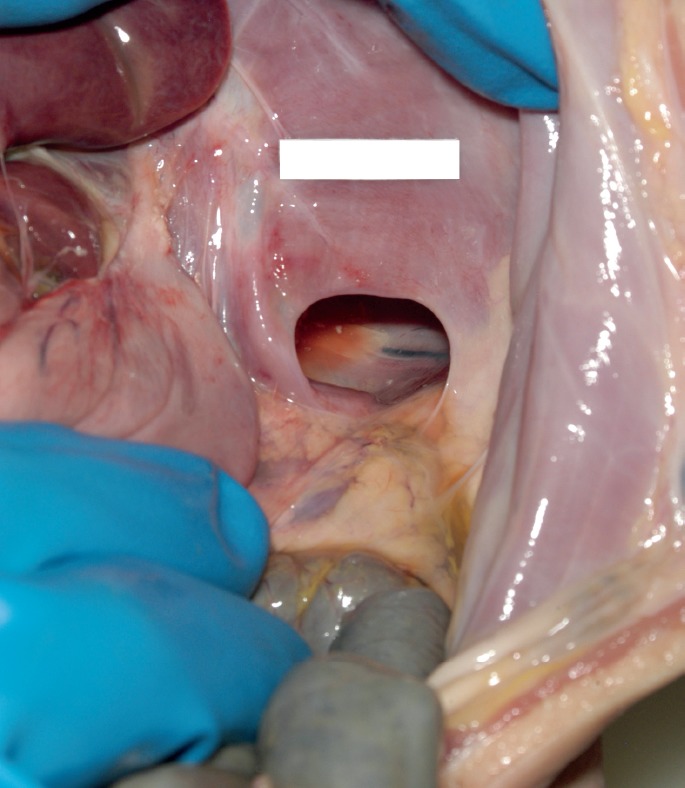

External examination revealed an unremarkable, small female infant, with no evidence of trauma other than that of resuscitative artifact. There was no clinical evidence of dehydration and the abdomen was not distended; in retrospect, it is seen to be moderately flattened, if not actually scaphoid. Upon opening the chest cavity, it was immediately seen that the stomach, markedly distended by air, was occupying much of the left pleural cavity (Image 2). Further examination revealed that the left lung was markedly compressed by the stomach, omentum, a long segment of small bowel, and the spleen, all of which had herniated into the chest cavity through a 2.8 by 1.5 cm defect in the posterior left hemidiaphragm in the costodiaphragmatic recess (Images 3 and 4). The right hemidiaphragm was intact and unremarkable, with a slightly ovoid central tendon that coursed down into the muscle towards the right costodiaphragmatic recess. The central tendon on the left side was somewhat elongated and serpiginous and extended radially to terminate in the hernia defect; it appeared thinner than the right. There was no laceration or hemorrhage of the diaphragm or into the surrounding soft tissues, with the defect margin appearing smooth and blade-like. The left lung was compressed and displaced superiorly, with the herniated abdominal viscera occupying two-thirds to three-quarters of the left chest cavity volume. The stomach contained approximately 150 mL of curdy to creamy white material, consistent with the mother's history of having been feeding the child when the episode occurred. There was no gross or microscopic suggestion of bowel ischemia or recent or resolved peritoneal inflammation. Otherwise, complete autopsy with specialist evaluation of heart and brain, extensive histologic sampling, bacterial and viral cultures, metabolic workup, and toxicology testing yielded no other findings.

Image 2.

Exposure of the thoracoabdominal contents reveals that the stomach occupies much of the left pleural cavity, compressing the left lung towards the apex and displacing mediastinal structures toward the right. Pneumothorax, an occasional complication of the condition, was not present.

Image 3.

In situ exposure of the left posterolateral diaphragmatic defect through which the stomach, small intestine and spleen had herniated into the left chest cavity (Bochdalek hernia).

Image 4.

The entire diaphgragm, transilluminated. The location of the hernia defect in the posterolateral left hemidiaphragm (arrow) is classic, occurring in approximately 90% of diaphgragmatic hernias.

Discussion

The diaphragm provides a barrier between the abdominal and thoracic cavities, preventing the abdominal viscera from entering the chest during respiration (1). Contraction of the diaphragm during inhalation induces expansion of the thorax, creating a negative pressure gradient between the alveolar space and the outside atmosphere, thereby allowing air to move into the lungs. Relaxation of the diaphragm during exhalation facilitates the expulsion of air from the lungs. In CDH, a defect in the diaphragm can allow abdominal organs to herniate into the thorax as the result of pressure from the flattening diaphragm and the negative intrathoracic pressure (1).

Reported incidence rates for CDH range from one in 2000 to as low as one in 5000 live births (2–6), comprising approximately 8% of major congenital malformations (5). Males are more frequently affected than females by a ratio of 1.5:1 (5). Subsequent pregnancies carry a low risk of recurrence (2%) (5). The most common form of CDH is the posterolateral Bochdalek hernia (2, 7), named after Victor Bochdalek, who described patients with this defect in 1848 (5). Seventy to 95% of CDH are of the Bochdalek type (1, 5), the majority being approximately 3 cm in diameter (1). Eighty to 85% occur on the left side (1, 2, 5), although they can also occur on the right (13%) or bilaterally (2%) (1). Other types of CDH include the anterior Morgagni hernia (∼27%), central hernia (∼2-3%) (6), and diaphragmatic eventration, the elevation of part or all of an otherwise complete diaphragm into the thoracic cavity (7, 8).

Development of the diaphragm begins during the fourth week of gestation and typically concludes between the eighth and twelfth weeks (1, 4, 7). The embryological components forming the diaphragm include the septum transversum, the dorsal mesentery of the esophagus, the pleuroperitoneal folds (PPF), and dorsal and dorsolateral body wall (1, 4, 7). Two PPF—ventral and medial mesenchymal structures that facilitate migration of pre-muscle and nervous cells—form the primordial posterolateral aspect of the diaphragm (1, 4). The PPF merge with the esophageal mesentery and the anterior central tendon from the ventral body wall, the septum transversum, which also contributes to the partition of the coelom, the stomach, and the duodenum (1, 4, 7). Fusion of these components completes the barrier between the abdomen and thorax (7). The right side of the diaphragm reaches completion prior to the left (1).

The pathogenesis of CDH is not well understood (4), but defects in the diaphragm are suspected to result from aberrations in the development of the PPF and pericardio-peritoneal canals (5, 7), failure of the mesenchymal components of the PPF to proliferate, or impaired migration of the somite-derived pre-muscle and nervous cells (4). Whatever the cause, the diaphragmatic structures either fail to extend toward each other or fail to fuse during the developmental period, resulting in an incomplete diaphragm or a complete diaphragm with poorly muscularized, and therefore weak, regions (5, 6).

In 50-60% of cases, the vast majority of which appear to be sporadic, CDH occurs as an isolated malformation (4, 6). Various additional malformations occur in the remaining cases, and the development of CDH in these cases is suspected to be associated with any of a number of chromosomal and gene abnormalities (4, 6). Associated chromosomal abnormalities include trisomies 13, 18, 21, and 22; Turner's syndrome (XO); Pallister-Killian syndrome (isochromosome or tetrasomy 12p); Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome (4p16 deletion); and derivative chromosome 22 t(11;22) (q23;q11) (6). Single-gene disorders including Cornelia de Lange syndrome (NIPBL, SMC3, SMC1A), craniofrontonasal syndrome (EFNB1), Denys-Drash syndrome (WT1), Donnai-Barrow syndrome (LRP2), Fryns syndrome, Matthew-Wood syndrome (STRA6), Spondylocostal dysostosis (DLL3, MESP2, LFNG, HES7), and Simpson-Golabi-Behmel syndrome (GPC3) have also been linked to CDH (2, 6); some studies suggest that disturbances in the retinoic acid pathway may play a contributory role as well (1).

The majority of infants with CDH present with respiratory distress in the neonatal period due to associated pulmonary hypoplasia. Infants typically appear cyanotic, with a scaphoid or flat abdomen, diminished breath sounds on the ipsilateral side of the hernia, and heart sounds displaced to the contralateral side (5, 6). Congenital diaphragmatic hernia in some neonates is unapparent, with the condition remaining relatively asymptomatic for years; in cases which present after infancy in children who are old enough to vocalize their experiences, rapid onset of gastrointestinal distress or abdominal pain in addition to respiratory distress is reported (6).

The most pressing complications of CDH in the symptomatic neonate relate to the herniation of abdominal contents through the diaphragmatic lesion and into the thoracic cavity during development. The abdominal viscera compress the ipsilateral lung and inhibit development of the alveoli and pulmonary vasculature, ultimately resulting in pulmonary hypoplasia (PH) and persistent pulmonary hypertension (PPH) (1, 2, 7). Respiratory complications range from very mild, with blood gas levels minimally affected, to severe with pulmonary hypoplasia and hypoxemia refractory to ventilation (2). It is theorized that severe pulmonary manifestations result from two hits: the first involving genetic and environment factors, and the second being the physical interference of lung development and fetal breathing movements by the presence of abdominal organs in the thorax (1).

Other noteworthy malformations associated with 40-50% of CDH cases include those of the central nervous system (CNS) and cardiovascular system (CVS), with CNS malformations being most commonly reported, but CVS malformations being an important prognostic factor (2). Regarding neurological and developmental abnormalities, recent data suggest that most children without a genetic correlate have fullscale intelligence quotient (FSIQ) scores within the low-average and average range, although hypotonia and other motor problems are frequently reported, particularly in patients who received extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) treatment. As seen with pulmonary manifestations, congenital heart abnormalities in CDH patients range from minor (atrial and small ventricular septal defects) to very severe if associated with ventricular outflow tract obstruction (coarctation of the aorta, tetralogy of Fallot, and hypoplastic left heart syndrome) or high pulmonary blood flow (atrioventricular septal defects and large perimembranous ventral septal defects) (2).

The reported mortality rate in liveborn patients with CDH ranges from 20-40% (3, 7), with approximately two-thirds of liveborn infants surviving hospital discharge and less than 1% of the annual infant mortality rate in the United States being attributed to CDH (3). Morbidity and mortality are associated with a number of factors in patients with CDH. The size of the diaphragmatic defect correlates with mortality and morbidity, as it is likely related to the degree of PH (3), and mortality is primarily associated with pulmonary complications, including PH, PPH, and respiratory distress (5). Other factors suggesting poor prognosis include low birth weight, early onset of symptoms, and aberrant stomach position, which are associated with delayed time to resolution of PH (9, 10). Mortality associated with pulmonary complications has been reduced to 10-20% in some tertiary referral centers but remains high for patients who develop bronchopulmonary dysplasia after being exposed to treatment modalities including high-frequency oscillation ventilation (HFOV) and ECMO in the neonatal intensive care unit (1).

The presence of additional malformations is also considered a negative prognostic factor (11), including those associated with chromosomal and gene abnormalities such as Fryns syndrome, an autosomal recessive disorder associated with CDH, coarse facies, ear abnormalities, cleft lip or palate, and digital hypoplasia (5). A higher mortality rate is also observed in patients with bilateral diaphragmatic defects and in patients with right-sided CDH (RCDH) compared to left-sided CDH (LCDH) (11), most likely due to the risk of liver herniation on the right side, which is severe and associated with a low survival rate (5, 10). Additionally, according to an analysis by the Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia Study Group on 1054 infants with CDH, the five-minute Apgar score was found to be a strong predictor of infant survival (9).

Intrauterine ultrasound (US) can identify CDH prenatally in most infants by the second trimester, the typical findings being the presence of bowel loops or the stomach in the chest, with mediastinal shift to the contralateral side (5, 6, 12). Right-sided defects tend to be more difficult to detect, and hernias can be missed if abdominal viscera are not present in the thorax at the time of US examination (2). Ultrasound is also used to measure fetal lung-to-head ratio (LHR), a numeric estimate of fetal lung size (5). Ultrasound is also useful to check the position of the liver, and the presence or extent of liver herniation on the right side (5). Cardiac echography, a form of US, allows for the assessment of pulmonary artery pressure, patency of the ductus arteriosus, and the effect of inhaled nitric oxide (NO) in patients with PPH (12).

Ante- or postmortem chest radiography can confirm CDH by a classic triad involving the presence of bowel loops in the chest, readily visible if bowel gas is present; a shift of the heart and mediastinum contralateral to the defect (5, 6), and, where there is extensive bowel herniation into the chest cavity the abdomen may appear radiologically free of normal intestinal gas patterning (13).

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in the coronal plane can reveal herniation of abdominal viscera into the thoracic cavity (5). Additionally, a meniscus of lung tissue behind hernia contents on axial images or above hernia contents on sagittal or coronal images, hernia contents appearing encapsulated, or a hernia sac outlined from above by pleural fluid are signs on MRI strongly associated with the presence of a hernia sac, and a combination of these features increases the predictive probability of these signs to almost 100% (14).

Imaging is also used clinically to assess prognosis. The combination of US diagnosis of CDH, LHR less than 1.0 prior to 25 weeks, and liver herniation is associated with a poor prognosis (2, 12); a recent study of 201 fetuses found that observed-to-expected MRI fetal lung volume and observed-to-expected US LHR predicted survival, necessity of ECMO therapy, and development of chronic pulmonary diseases in fetuses with LCDH at all gestational ages, with the strongest correlation noted prior to 32 weeks gestation (15).

Once discovered, CDH may be repaired antenatally, but this confers little survival advantage (3, 12). Laproscopic tracheal occlusion to increase prenatal lung growth is also employed (12). Management of neonates with CDH focuses primarily on the pulmonary complications, including PH, PPH, and lung dysmaturity (6, 16). Techniques include mechanical ventilation, HFOV, ECMO, exogenous surfactant, inhaled NO, and CDH repair in utero (3, 16). High frequency oscillation ventilation is increasingly used as an alternative to conventional ventilation, as conventional ventilation is associated with a higher risk of secondary (ventilator-induced) lung injury; permissive hypercarbia may be preferred for the same reason (12). Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation is used when patients cannot be ventilated by conventional methods or with HFOV, although ECMO is less effective in managing CDH (60% survival) than in other forms of infant respiratory distress and failure (80%) (12).

Although CDH carries a mortality rate of approximately 20-40% in live-born patients (3, 7), this does not account for “hidden mortality,” when death occurs prior to diagnosis and treatment (11). Although the majority of CDH patients present at birth with respiratory distress associated with pulmonary complications, the presence of diaphragmatic defect does not guarantee herniation during fetal development. As such, in cases where prenatal herniation does not occur, the lungs would develop normally and the neonate may be asymptomatic. With no visible abnormalities on US examination and no apparent symptoms after delivery, there is no reason for CDH to be suspected, and the diagnosis is often missed. The aforementioned decedent falls into this category, providing a prime example of hidden mortality. A number of similar cases of otherwise apparently healthy patients, ranging in age at presentation from a few months to years and even decades, with abrupt symptom onset related to sudden herniation of abdominal viscera through the defect and into the thoracic cavity, have been reported (17–20). Most patients with late-presenting CDH report upper quadrant pain, dyspnea, and vomiting, which occur either in one severe episode leading to medical investigation and diagnosis, or intermittently if herniation occurs and subsequently resolves without medical intervention (17–20).

The possibility that this was an intermittent/relapsing condition was considered, particularly in light of the weight loss early in the postnatal period. Microscopically, there was no peritoneal inflammation, but a sprinkling of chronic inflammatory cells near the diaphragmatic defect margin suggested slight irritation. At autopsy, as the herniated abdominal contents were being decompressed, it was noted that the spleen was rotated on its vascular peduncle; in this position, packed in with filmy omentum and small bowel, it effectively seemed to represent a ball valve occluding the hernia defect, blocking spontaneous reduction.

In the presence of a diaphragmatic defect, what would otherwise be considered normal anatomy and physiology, the mobility of abdominal viscera in the upper left quadrant (e.g., stomach, intestines, and spleen) and creation of a pressure gradient during normal respiration facilitate the entry of abdominal organs into the thoracic cavity. The appearance of the diaphragmatic defect—clean and blade-like, without surrounding hemorrhage, laceration, or inflammation—is consistent with the chronicity of the lesion. Given the infant's history, the physical appearance of the lesion, and the sudden appearance of the infant's symptoms, herniation in the decedent was likely precipitated by a distinct event.

When feeding, infants swallow a significant amount of air, which increases intraabdominal pressure. The practice of burping is employed to expel this air from the stomach, which involves inducing an additional and sudden increase in intraabdominal pressure in order to force this gas upward and out of the stomach. In the present case, the defect in the diaphragm allowed the air-distended stomach to take an alternative route upward and into the thoracic cavity during the burping process. This scenario is consistent with the acute onset of the infant's symptoms. The result was compression of the left lung by the intruding viscera, occupying significant space and likely unable to withdraw. With subsequent attempts to breathe, the negative pressure gradient naturally created in the thoracic cavity might pull more of the viscera into the chest and arrest it there, furthering compression of the lungs and displacement of the mediastinum in a manner resembling that of tension pneumothorax (17). Without prompt treatment, this would quickly lead to respiratory failure and death. In a similar case, a 22-month old female with undiagnosed CDH died suddenly as a result of acute herniation, determined to be due to an increase in intraabdominal pressure induced by coughing (17).

Congenital diaphragmatic hernia is only suspected in the presence of genetic anomalies, congenital abnormalities, signs on imaging, and symptom-inducing complications; in fact, diagnostic methods rely on direct visualization of herniated abdominal viscera or the manifestation and degree of severity of secondary pathology such as pulmonary abnormalities (i.e., via LHR) to predict or confirm the presence of CDH. As a result, silent cases provide no detectable signs or symptoms that would lead clinicians to suspect its presence or investigate the constitution of the diaphragm.

The possibility that the herniation of abdominal organs into the chest cavity was an artifact of resusictation, with the death having another, unidentified cause, was given due consideration. A complete autopsy failed to reveal an alternative competent cause of death, but, more tellingly, the mother's description of the child's course of respiratory difficulty after being burped fit with the autopsy findings and there were no other injuries to suggest an overly vigorous resuscitation. Accordingly, the death was certified as “Respiratory compromise due to congenital diaphragmatic hernia,” with the manner of death classified as natural.

Conclusion

In neonatal and pediatric cases such as this—where patient history was unremarkable and onset of respiratory distress was acute, severe, and lethal before medical attention could be received—forensic examiners should consider CDH among the differential. In general, clinicians should be aware of the role of CDH in hidden mortality, and efforts should be made to uncover diagnostic methods capable of detecting these silent, yet deadly, cases.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to express their profound gratitude to Brian Womble, who performed the forensic radiography, photography, and image processing for this article.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors have indicated that they do not have financial relationships to disclose that are relevant to this manuscript

ETHICAL APPROVAL

As per Journal Policies, ethical approval was not required for this manuscript

STATEMENT OF HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

This article does not contain any studies conducted with animals or on living human subjects

STATEMENT OF INFORMED CONSENT

No identifiable personal data were presented in this manuscsript

DISCLOSURES & DECLARATION OF CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors, reviewers, editors, and publication staff do not report any relevant conflicts of interest

References

- 1.Keijzer R., Puri P. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2010. Aug; 19(3): 180–5. PMID: 20610190. 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bohn D. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002. Oct 1; 166(7): 911–5. PMID: 12359645. 10.1164/rccm.200204-304CC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia Study Group, Lally KP, Lally PA, et al. Defect size determines survival in infants with congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Pediatrics. 2007. Sep; 120(3): e651–7. PMID: 17766505. 10.1542/peds.2006-3040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mesdag V., Andrieux J., Coulon C. et al. Pathogenesis of congenital diaphragmatic hernia: additional clues regarding the involvement of the endothelin system. Am J Med Genet A. 2014. Jan; 164A(1): 208–12. PMID: 24352915. 10.1002/ajmg.a.36216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doyle N.M., Lally K.P. The CDH Study Group and advances in the clinical care of the patient with congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Semin Perinatol. 2004. Jun; 28(3): 174–84. PMID: 15283097. 10.1053/j.semperi.2004.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pober B.R., Russell M.K., Guernsey Ackerman K. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia overview. In: Pagon R.A., Adam M.P., Ardinger H.H. et al. , editors. GeneReviews [Internet]. Seattle: University of Washington, Seattle; c1993-2016 [updated 2010. Mar 16, cited 2016 Sep 30]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1359/. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bolino G., Gitto L., Serinelli S., Maiese A. Autopsy features in a newborn baby affected by a central congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Med Leg J. 2015. Mar; 83(1): 51–3. PMID: 25573226. 10.1177/0025817214554871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ghribi A., Bouden A., Braiki M. et al. Diaphragmatic eventration in children. Tunis Med. 2015. Feb; 93(2): 76–8. PMID: 26337303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia Study Group. Estimating disease severity of congenital diaphragmatic hernia in the first 5 minutes of life. J Pediatr Surg. 2001. Jan; 36(1): 141–5. PMID: 11150453. 10.1053/jpsu.2001.20032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lusk L.A., Wai K.C., Moon-Grady A.J. et al. Fetal ultrasound markers of severity predict resolution of pulmonary hypertension in congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015. Aug; 213(2): 216.e1–8. PMID: 25797231. PMCID: PMC4519413. 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.03.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Skari H., Bjornland K., Haugen G. et al. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia: a meta-analysis of mortality factors. J Pediatr Surg. 2000. Aug; 35(8): 1187–97. PMID: 10945692. 10.1053/jpsu.2000.8725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bohn D. Diaphragmatic hernia–pre and postnatal. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2006; 7 Suppl 1: S249–50. PMID: 16798582. 10.1016/j.prrv.2006.04.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Swischuk L.E. Imaging of the newborn, infant and young child. 4th ed. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1997. 1088 p. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zamora I.J., Mehollin-Ray A.R., Sheikh F. et al. , Predictive value of MRI findings for the identification of a hernia sac in fetuses with congenital diaphragmatic hernia. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2015. Nov; 205(5): 1121–5. PMID: 26496561. 10.2214/AJR.15.14476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kastenholz K.E., Weis M., Hagelstein C. et al. Correlation of observed-to-expected MRI fetal lung volume and ultrasound lung-to-head ratio at different gestational times in fetuses with congenital diaphragmatic hernia. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2016. Apr; 206(4): 856–66. PMID: 27003054. 10.2214/AJR.15.15018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Logan J.W., Rice H.E., Goldberg R.N., Cotten C.M. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia: a systematic review and summary of best-evidence practice strategies. J Perinatol. 2007. Sep; 27(9): 535–49. PMID: 17637787. 10.1038/sj.jp.7211794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chhanabhai M., Avis S.P., Hutton C.J. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia. A case of sudden unexpected death in childhood. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 1995. Mar; 16(1): 27–9. PMID: 7771378. 10.1097/00000433-199503000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hight D.W., Hixsoh S.D., Reed J.O. et al. Intermittent diaphragmatic hernia of Bochdalek: report of a case and literature review. Pediatrics. 1982. May; 69(5): 601–4. PMID: 7079017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vukić Z. Left Bochdalek hernia with delayed presentation: report of two cases. Croat Med J. 2001. Oct; 42(5): 569–71. PMID: 11596175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zefov V.N., Almatrooshi M.A. Chest X-ray findings in late-onset congenital diaphragmatic hernia, a rare emergency easily misdiagnosed as hydropneumothorax: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2015. Dec 22; 9: 291 PMID: 26695937. PMCID: PMC4688985. 10.1186/s13256-015-0755-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]