Abstract

The necks of infants and young children are not only anatomically different from adults, but are also supported by much weaker musculoskeletal systems and are therefore prone to trauma as a result of extension/flexion (shaking) or contact trauma to the head. Shaking cervical spine injuries can occur at much lower levels of head velocity and acceleration than those reported for shaken baby syndrome. The proper method for a comprehensive and detailed examination of the neck in pediatric homicide and suspected homicide cases is the en bloc examination of the neck, because the standard examination of the spinal cord not only distorts the anatomical relationship of the cord and osteocartilagenous structures, but also excludes the cervical nerves, ganglia, and the vertebral arteries from being evaluated. Interpretation of gross and microscopic findings using this method requires experience and knowledge of the anatomical relationship and common artifacts, such as epidural, focal intradural, or even isolated nerve hemorrhage to avoid misinterpretation. It is our opinion that this method should be applied to all pediatric homicide or suspected homicide cases, but is not suited for routine or nonsuspicious cases as it will add to the time and cost of medical examiner's operations.

Keywords: Forensic pathology, En bloc neck examination, Shaken neck injury, Pediatric homicide, Dorsal nerve root hemorrhage, Spinal epidural hemorrhage

Introduction

The en bloc examination of the neck is not routinely performed in pediatric homicide cases and many medical examiners are unfamiliar with this simple but thorough examination. The autonomic centers for cardiovascular and respiratory functions are located in the cervico-medullary junction which, together with cervical nerves originating from the upper cervical cord, control vital functions in the body.

Since the first description of shaken baby syndrome by Guthkelch (1) and later by Caffey (2), the research has concentrated on the biomechanics of brain injuries with forces necessary to produce the subdural hemorrhage, but a comprehensive neck examination was and is commonly overlooked. As demonstrated by Baker and Berdon, using dynamic radiographs, the fulcrum for flexion is at C2-C3 in infants and young children, at C3-C4 at about age five or six, and at C5-C6 in adults (3). Injury to cervical nerves at this level could potentially interfere with innervation of the diaphragm and breathing. The phrenic nerve, for example, which originates mainly from the fourth cervical nerve but also receives contributions from the cervical nerves C3-C5 and innervates the diaphragm, can be compromised, adding to the respiratory complications or respiratory failure if bilaterally injured. A standard brain and spinal cord examination not only distorts the continuation of this vital anatomic region, but also excludes the examination of the nerve roots, ganglia, and surrounding soft tissues.

In pediatric homicide cases, but also generally in all pediatric cases, one- or two-view analog or digital radiographs are routinely performed mainly to assess the skull, rib cage, and long bones for acute or healed fractures. These radiographs are commonly performed without standard radiographic positioning of the body, which makes assessment of the cervical spine even more unreliable. Even using more advanced available radiographic methods, such as postmortem computed tomography, only limited information can be obtained in terms of spinal cord and soft tissue injuries of the neck region.

There are several unique aspects of the anatomy of the child's neck. Neck muscle strength increases with age, yet, with the greater head mass attached to a slender neck, the neck muscles are generally not developed sufficiently to dampen violent head movement, especially in children (4). The cervical vertebrae are mainly cartilaginous in the infants, with complete replacement of this cartilage by bone occurring slowly. Articular facets are shallow and are much weaker than in an adult. The disproportionately large head, the weak cervical spine musculature, and laxity can subject the infant to uncontrolled and passive cervical spine movements and possibly to compressive or distraction forces in certain impact deceleration environments. These all contribute to a high incidence of injury to the upper cervical spine as compared to the lower cervical spine area (5). In autopsy specimens, the elastic infantile vertebral bodies and ligaments allow for column elongation of up to two inches, but the spinal cord ruptures if stretched more than one quarter inch (6). Additionally, the facet joints at C1 and C3 are nearly horizontal for the first several years of life, allowing for subluxations at relatively little force (7). Bandak, in his study of biomechanics analysis of injury mechanism, concluded that shaking cervical spine injury can occur at a much lower level of head velocity and acceleration than those reported for shaken baby syndrome (8).

To examine the spinal cord and cervicomedullay region in continuity, one of the authors (DF) in the late 1980s examined the spinal cord and the osteocartilagenous neck structures by removing the neck en bloc. The neck was removed in a series of 33 children age 0-14 years whose deaths were the result of traffic accident (9). In this method, a bone window was cut first at the occiput to gain access to the cervicomedullary junction at the foramen magnum. The body was then repositioned and the cervical spine was removed circumferentially by a combination of anterior and posterior approaches.

In 2004, Judkins et al., in an effort to maintain the continuity of the upper cervical region and medulla, proposed removing the spinal cord in continuation with the brain (10). In this method, using a posterior approach and cutting the posterior laminae and cervical nerves, the spinal cord is removed in continuity with the brain structures. Although the entire spinal cord can be examined with this method, the osteocartilagenous structures with surrounding soft tissues, vertebral arteries, nerve roots, and dorsal root ganglia cannot be examined and more importantly, the three-dimensional relationship of these structures is lost. Additionally, applying this method could potentially create unwanted artifacts.

To maintain the three-dimensional relationship of the spine and upper cervical region, Matshes et al. used a similar method to that of Fowler's, by removing the spine en bloc. In this method, the periforaminal segment of the occipital bone is cut first and then the V3A and V3B segments of the vertebral arteries are incised and separated posteriorly. The V3 segment of the vertebral arteries runs from C2 to the dura. They applied this method to patients who died following neurosurgical intervention and chiropractic manipulation (11). The authors also applied the same method, but without removing the vertebral artery segments, to a series of infants and young children with suspected acceleration/deceleration of the neck and examined the en bloc sections between C3 and C5, one section proximal to C3, and one section distal to C5 (12).

In the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner for the State of Maryland in Baltimore, in addition to systematic examination of the entire central nervous system, the cervical spine is removed en bloc using the methodology described by Matshes and Fowler (9, 12) in all child homicide and suspected neglect cases by one of the authors (ZA).

Methods

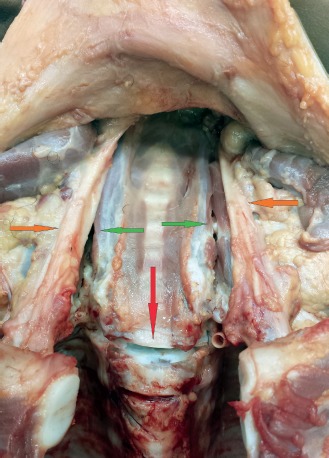

After routine external examination and photographic documentation, full-body radiographs and computed tomography are performed and evaluated. To eliminate puncture artifacts of the cervical region, cerebrospinal fluid is obtained from the lumbar segment of the spine for microbiologic studies. The brain removal follows routine evisceration of the cervical, thoracic and abdominal organs. The brain is removed by cutting above the distal medulla to keep the cervicomedullary junction intact. A layered anterior neck dissection can be performed, if indicated. The superficial muscle layers of the posterior neck are then examined by usual midline incision. The deeper soft tissue layers are included in the microscopic sections and do not require further examination at this point. The body is then positioned prone and the periforamen magnum region of the occipital bone is sawed (Image 1). This segment should be wide enough to accommodate the transverse and spinous processes of the upper cervical vertebrae. After the periforamen segment is sawed, the cut is then extended circumferentially and distally along the sides of the upper cervical region for a distance of approximately 2-3 cm using a scalpel. Next, the first ribs are cut at the costovertebral junction and the cervical spine is separated from the thoracic segment by sectioning of the intervertebral disc between thoracic spine T1 and T2 (Image 2). The carotid arteries are then lateralized to prevent accidental puncturing and the paravertebral soft tissues are cut medial to the carotid arteries. Starting distally at T1/T2, the spine is then carefully separated and lifted from the surrounding soft tissues. The cut is then extended superiorly and circumferentially using scalpel or scissors until the cervical spine is freed laterally and posteriorly and the cut joins proximally the previous cut extended distally from the periforamen magnum segment. Following the en bloc resection of the cervical spine (Image 3), the thoracic and lumbar spinal cord can be removed for routine neuropathologic examination.

Image 1.

View at the base of skull with a square cut around the foramen magnum.

Image 2.

The intervertebral disc between thoracic vertebrae T1 and T2 is cut (red arrow). The carotid arteries (orange arrows) are lateralized with cut extending along the spine (green arrows).

Image 3.

The en bloc removed neck before fixation and decalcification, left lateral perspective.

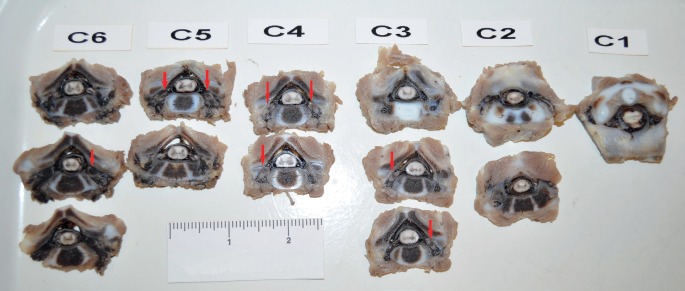

The en bloc removed cervical spine is fixed in 10% formaldehyde for seven to ten days and then placed in 20% formic acid for decalcification for approximately two weeks. Following fixation and decalcification, the spine is serially sectioned, photographed, and examined grossly (Image 4). All sections are imbedded in 3 × 2” blocks and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) (Image 5). Following routine evaluation of the H&E sections, if indicated, selected sections are stained with amyloid precursor antibodies and Movat's pentachrome.

Image 4.

Photograph showing serially sectioned C1-C6 levels after decalcification. Nerve roots and ganglia hemorrhage is readily identifiable in multiple levels as focal dark areas (arrows).

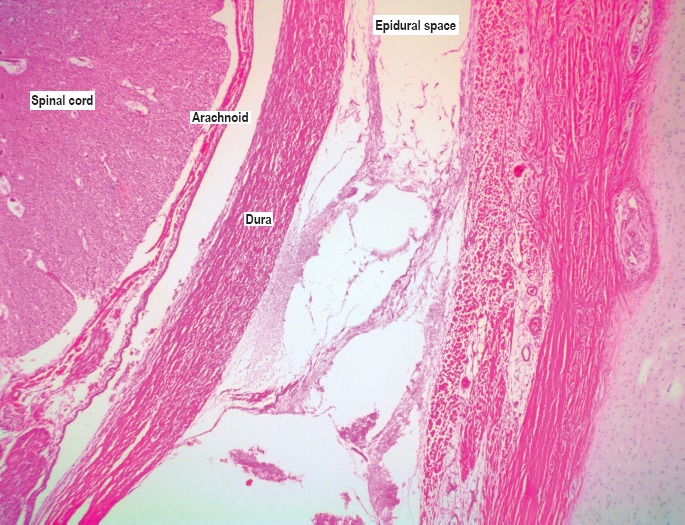

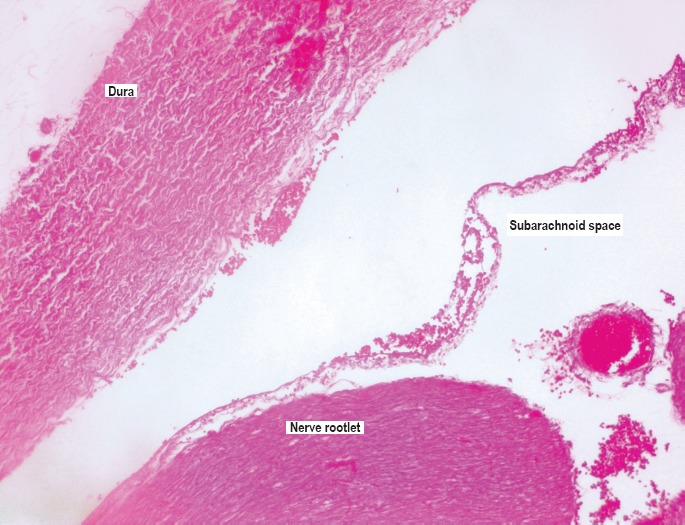

Image 5.

Whole-mount gross photograph of the hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained slide at the level of C5 in a case of blunt force head injuries. The hemorrhage was noted on gross examination in the bilateral dorsal root ganglia (DRG) and ventral roots (VR). Hemorrhage is visible in the paravertebral soft tissues (PVST). Epidural space with mostly drained venous plexus (EDS), dura mater (DM), and subdural space (SDS) and their anatomical compartmental relationship is easily identifiable (H&E, x10).

Discussion

The necks of infants and young children are prone to acceleration/deceleration trauma for reasons discussed previously. These injuries may result from shaking or contact trauma to the head, subjecting the weak infant neck to substantial flexion/extension and rotational forces. A proper method to examine all cervical structures in trauma cases is the en bloc removal and examination of the neck. The major advantages of the en bloc examination of the neck are the preservation of all anatomic structures and examination of the cervicomedullary junction. Hemorrhage of the nerve roots and ganglia caused by flexion/extension and thus stretching of the cord and nerves is readily identifiable, not only microscopically, but also grossly. Hemorrhage of the surrounding deeper soft tissues is also readily identifiable (Image 6). The vertebral arteries are preserved in their normal anatomic compartment and can be grossly and microscopically examined after serial sectioning of the neck.

Image 6: A).

Gross image at the level of C5 showing epidural hemorrhage (red arrow), subdural hemorrhage (green arrow), and extensive hemorrhage in the nerve roots and spinal ganglia (orange arrows). Hemorrhage is also visible in the paravertebral soft tissues (yellow arrows). The empty space marked with a red star corresponds to drained venous plexus of the epidural space. Microscopically, the spinal cord showed extensive vacuolation and necrosis with petechial hemorrhages of gray and white mater.

Image 6: B).

Microscopic image of the boxed area of 6A showing hemorrhage in the dorsal root ganglia and ventral nerve root (H&E, x100).

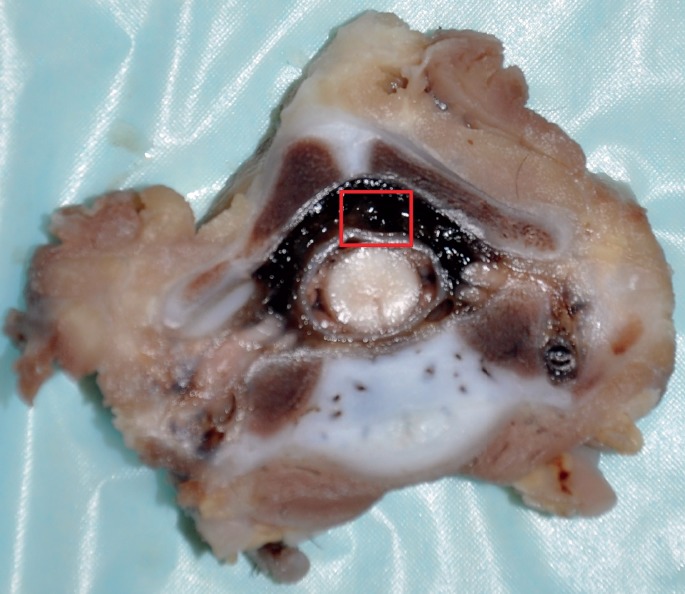

In order to interpret the findings accurately, good knowledge of anatomy and histology of this region and their structural relationship is important. One of the authors (ZA) examined or participated in the evaluation of 24 cases, ages between one month to four years, including five homicides (blunt force injuries), sudden unexplained death in infancy (SUDI), sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), natural causes (infection, conduction system abnormalities), and accidental deaths (asphyxia by overlay, entrapment, pedestrian vs. motor vehicle). In our case series, more than half showed epidural hemorrhage throughout the cervical cord or focally, independent of the cause of death, postmortem interval, or position of the body. This certainly contradicts the reported results of other investigators that epidural hemorrhage is rarely observed in children (13). Interestingly, all cases with grossly identified epidural hemorrhage also showed extravasation of blood into surrounding soft tissues of dorsal roots or ganglia, and vertebral arteries. The spinal cord is surrounded by a robust venous plexus, which could be interpreted grossly and microscopically as epidural hemorrhage (Images 7 and 8). Structurally, the epidural space and the venous circulation are directly connected and the connection is most commonly found in the cervical and upper thoracic spine (14). The apparent epidural hemorrhage may result from increased venous pressure with congested and distended venous plexus or other perimortem hemodynamic changes; therefore, “pseudo-epidural hemorrhage” is a more appropriate term to use. In our experience and as pointed out by other investigators (15, 16), the epidural hemorrhage by itself, without other evidence of trauma, is a postmortem artifact unless proven otherwise and should be interpreted with caution. Focal intradural hemorrhage was noted in some natural, accidental (pedestrian struck by car), and undetermined (SUDI) cases. In our experience, cervical cord subdural hemorrhage was noted in the majority of homicidal blunt force head trauma cases and was extensive throughout the cord and associated with cerebral subdural and subarachnoid hemorrhage as well as optic nerve and retinal hemorrhages. In one case of homicidal blunt force head injuries, the subdural hemorrhage was noted in the upper cervical region only. The presence of cervical cord subdural hemorrhage may be due to tracking of intracranial subdural hemorrhage, direct trauma, flexion/extension, or rotational forces. The pathophysiology of spinal cord subdural hemorrhage may be different from intracranial subdural hemorrhage as there is a relative lack of bridging veins (19). It is impossible to be certain about the origin of cervical cord subdural hemorrhage in the presence of intracranial subdural hemorrhage, but hemorrhage in the nerve roots and ganglia, indicative of shearing forces, are certainly contributing to cervical cord subdural hemorrhage, or the cause, if cerebral subdural hemorrhage is not present. Minimal, microscopic subdural hemorrhage was noted in two nontrauma related cases (Image 9). The presence of minimal focal subdural hemorrhage is most likely an artifact in the absence of other trauma. Hemorrhage in the nerve roots and dorsal ganglia in homicidal blunt force head trauma was noted in all cases and is typically present in multiple segments of cervical spine. The nerve roots and ganglia hemorrhage in homicide cases was noted microscopically as well as macroscopically, although unilateral hemorrhage of perineurium and septae of axons/nerves was noted in a nontrauma case microscopically (Image 10). Another commonly observed finding is the perivertebral artery and perivertebral space hemorrhage. These anatomical compartments contain venous structures similar to epidural space (17, 18); therefore the mechanism of bleeding is most likely similar to that of epidural hemorrhage and not confirmatory of trauma. The pertinent gross and microscopic findings are summarized in Table 1.

Image 7.

Microscopic image of the epidural space showing the thin-walled venous channels (H&E, x40).

Image 8: A).

Gross image at the level of C7 showing distended epidural space and apparent epidural hemorrhage.

Image 9.

Microscopic image showing minimal focal subdural hemorrhage in a 2-year-old girl with no evidence of acute or remote trauma. The cause of death was cardiac arrhythmia due to endocardial fibroelastosis (H&E, x100).

Image 10.

Microscopic image showing hemorrhage in the perineurium and septae of dorsal nerves in a 2-month-old boy with no evidence of acute or remote trauma. The cause of death was classified as sudden unexplained death in infancy (H&E, x100).

Table 1.

Gross and Microscopic Findings of the En Bloc Examined Neck in Homicidal, Accidental, Natural, and Undetermined Cases Ages One Month to Four Years

| COD | MOD | Gross | Microscopic |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Hypoxic encephalopathy of unknown etiology | Undetermined | No hemorrhage | Intradural hemorrhage, focal |

| 2 Asphyxia (trapped under garage door) | Accident | Minute focal soft tissue hemorrhage C5-6 | Minute focal soft tissue hemorrhage C3 |

| 3 Blunt force injuries | Homicide | Epidural hemorrhage | Multi-level DRG, soft tissue hemorrhage, epidural hemorrhage, focal intradural hemorrhage, Subdural hemorrhage |

| 4 Multiple injuries | Accident | Intradural hemorrhage | Intradural and subdural hemorrhage |

| 5 SUDI | Undetermined | Epidural hemorrhage | Epidural hemorrhage |

| 6 Conduction system abnormalities | Natural | Normal | Normal |

| 7 SIDS | Natural | Normal | Focal minimal subarachnoid and subdural hemorrhage |

| 8 Undetermined | Undetermined | Normal | Normal |

| 9 Head and neck injuries | Homicide | Multi-level DRG, epidural, subdural, and soft tissue hemorrhage | Multi-level DRG, ventral nerve roots hemorrhage, epidural and subdural hemorrhage |

| 10 Multiple injuries | Homicide | Multi-level DRG, epidural, subdural hemorrhage, and soft tissue hemorrhage | Multi-level DRG, epidural, subdural, and soft tissue hemorrhage |

| 11 Probable asphyxia (overlay) | Accident | Normal | Normal |

| 12 SUDI | Undetermined | Normal | Focal intradural hemorrhage |

| 13 SUDI | Undetermined | Epidural hemorrhage | Epidural hemorrhage |

| 14 Pneumonia | Natural | Epidural hemorrhage | Focal intradural and epidural hemorrhage |

| 15 Asphyxia (overlay) | Accident | Epidural hemorrhage | Focal epidural and intradural hemorrhage |

| 16 Tracheitis and pneumonia | Natural | Normal | Minimal epidural hemorrhage |

| 17 Multiple injuries | Homicide | Soft tissue hemorrhage, epidural hemorrhage | Multi-level DRG, subdural, epidural, subarachnoid, and soft tissue hemorrhage |

| 18 SUDI | Undetermined | Epidural hemorrhage | Focal intradural and epidural hemorrhage |

| 19 SUDI | Undetermined | Normal | Normal |

| 20 Endocardial fibroelastosis | Natural | Epidural hemorrhage | Minimal subdural hemorrhage |

| 21 Upper respiratory parainfluenza infection | Natural | Epidural hemorrhage | Minimal subdural hemorrhage |

| 22 SUDI | Undetermined | Epidural hemorrhage | Epidural and intradural hemorrhage, unilateral axons/nerves perineurium/septae hemorrhage (C7) |

| 23 Multiple injuries | Homicide | Epidural hemorrhage, subdural hemorrhage, multi-level DRG | Epidural hemorrhage, subdural hemorrhage, multi-level DRG |

| 24 Multiple injuries | Accident | Epidural hemorrhage | Epidural hemorrhage |

COD – Cause of death

MOD – Manner of death

SUDI – Sudden unexplained death in infancy

SIDS – Sudden infant death syndrome

DRG – Dorsal root ganglion

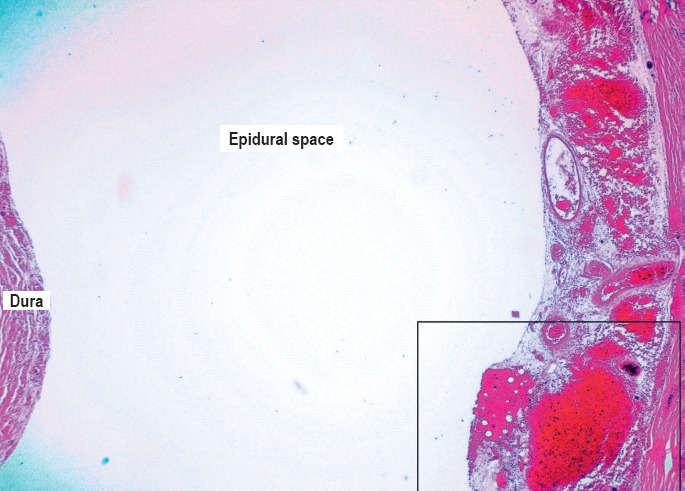

Image 8: B).

Microscopic image of the boxed area in 8A showing an empty space and extensive with blood filled vascular channels (H&E, x40).

Image 8: C).

Microscopic image of the boxed area in 8B shows a very vascular tissue which has separated/collapsed due to tissue processing. There was no hemorrhage noted outside the collapsed vascular tissue. The thin-walled framework of the venous plexus can be appreciated at this magnification (H&E, x100).

Conclusion

It is our opinion that epidural hemorrhage (diffuse or focal), focal intradural hemorrhage, focal subarachnoid hemorrhage, perivertebral artery/perivertebral space hemorrhage as well as minimal microscopic subdural hemorrhage, are not necessarily indicative of inflicted trauma and should be interpreted in context with other findings. The most compelling findings indicative of trauma (hyperflexion/hyperextension injuries) are dorsal root ganglia or nerve rootlet hemorrhage and paravertebral muscle hemorrhage.

The en bloc examination will add to the processing cost and time, and requires the histology lab to adapt to new protocols and equipment to process and stain larger blocks. The histologic interpretation requires time, experience, and familiarity with this approach for correct interpretation of the findings. Despite all advantages, it is our opinion that this method is not suited for routine infant autopsies and should be reserved for blunt force homicide cases or if otherwise indicated.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors have indicated that they do not have financial relationships to disclose that are relevant to this manuscript

ETHICAL APPROVAL

As per Journal Policies, ethical approval was not required for this manuscript

STATEMENT OF HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

This article does not contain any studies conducted with animals or on living human subjects

STATEMENT OF INFORMED CONSENT

No identifiable personal data were presented in this manuscsript

DISCLOSURES & DECLARATION OF CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors, reviewers, editors, and publication staff do not report any relevant conflicts of interest

References

- 1.Guthkelch A.N. Infantile subdural haematoma and its relationship to whiplash injuries. Br Med J. 1971. May 22; 2(5759): 430–1. PMID: 5576003. PMCID: PMC1796151. 10.1136/bmj.2.5759.430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caffey J. The whiplash shaken infant syndrome: manual shaking by the extremities with whiplash-induced intracranial and intraocular bleedings, linked with residual permanent brain damage and mental retardation. Pediatrics. 1974. Oct; 54(4): 396–403. PMID: 4416579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baker D.H., Berdon W.E. Special trauma problems in children. Radiol Clin North Am. 1966. Aug; 4(2): 289–305. PMID: 5912256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huelke D.F. An overview of anatomical considerations of infants and children in the adult world of automobile safety design. Annu Proc Assoc Adv Automot Med. 1998; 42: 93–113. PMCID: PMC3400202. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sumchi A.P., Sternback G.L. Hangman's fracture in a 7-week-old infant. Ann Emerg Med. 1991. Jan; 20(1): 86–9. PMID: 1984737. 10.1016/s0196-0644(05)81128-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leventhal H. Birth injuries of the spinal cord. J Pediatr. 1960; 56(4): 447–453. 10.1016/s0022-3476(60)80356-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kasai T., Ikata T., Katoh S. et al. Growth of the cervical spine with special reference to its lordosis and mobility. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1996. Sep 15; 21(18): 2067–73. PMID: 8893429. 10.1097/00007632-199609150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bandak F.A. Shaken baby syndrome: a biomechanics analysis of injury mechanisms. Forensic Sci Int. 2005. Jun 30; 151(1): 71–9. PMID: 15885948. 10.1016/j.forsciint.2005.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fowler D.R. Pediatric spinal cord injury in motor vehicle accidents; a prospective postmortem study of 33 cases of pediatric motor vehicle victims.[master's thesis]. Capetown (South Africa): University of Cape Town; 1991. 191 p. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Judkins A.R., Hood I.G., Mirchandani H.G., Rorke L.B. Technical communication: rationale and technique for examination of nervous system in suspected infant victims of abuse. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2004. Mar; 25(1): 29–32. PMID: 15075685. 10.1097/01.paf.0000113811.85110.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matshes E.W., Joseph J. Pathologic evaluation of the cervical spine following surgical and chiropractic interventions. J Forensic Sci. 2012. Jan; 57(1): 113–9. PMID: 22040123. 10.1111/j.1556-4029.2011.01935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matshes E.W., Evans R.M., Pinckard J.K. et al. Shaken infants die of neck trauma, not of brain trauma. Acad Forensic Pathol. 2011. Jul; 1(1): 82–91. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rutty G.N., Squier W.M., Padfield C.J. Epidural haemorrhage of the cervical spinal cord: a post-mortem artefact? Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2005. Jun; 31(3): 247–57. PMID: 15885062. 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2004.00633.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buffington C.W., Nicols L., Moran P.L., Blix E.U. Direct connections between the spinal epidural space and the venous circulation in humans. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2011. Mar-Apr; 36(2): 134–9. PMID: 21270727. 10.1097/AAP.0b013e31820d41ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Valdes-Dapena M. Sudden death in infancy: a report for pathologists. Perspect Pediatr Pathol. 1975; 2: 1–14. PMID: 1129026. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harris L.S., Adelson L. “Spinal injury” and sudden infant death. A second look. Am J Clin Pathol. 1969. Sep; 52(3): 289–95. PMID: 5805994. 10.1093/ajcp/52.3.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wiltse L.L., Fonseca A.S., Amster J. et al. Relationship of the dura, Hoffmann's ligaments, Batson's plexus, and fibrovascular membrane lying on the posterior surface of the vertebral bodies and attaching to the deep layer of the posterior longitudinal ligament. An anatomical, radiologic, and clinical study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1993. Jun 15; 18(8): 1030–43. PMID: 8367771. 10.1097/00007632-199306150-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jovanovic M.S. A comparative study of the foramen transversarium of the sixth and seventh cervical vertebrae. Surg Radiol Anat. 1990; 12(3): 167–72. PMID: 2287982. 10.1007/bf01624518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nicholas D.S., Weller R.O. The fine anatomy of the human spinal meninges: a light and scanning electron microscopy study. J Neurosurg. 1988. Aug; 69(2): 276–82. PMID: 3392571. 10.3171/jns.1988.69.2.0276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]