Abstract

Fatal, allegedly inflicted pediatric head trauma remains a controversial topic in forensic pathology. Recommendations for systematic neuropathologic evaluation of the brains of supposedly injured infants and children usually include the assessment of long white matter tracts in search of axonopathy — specifically, diffuse axonal injury. The ability to recognize, document, and interpret injuries to axons has significant academic and medicolegal implications. For example, more than two decades of inconsistent nosology have resulted in confusion about the definition of diffuse axonal injury between various medical disciplines including radiology, neurosurgery, pediatrics, neuropathology, and forensic pathology. Furthermore, in the pediatric setting, acceptance that “pure” shaking can cause axonal shearing in infants and young children is not widespread. Additionally, controversy abounds whether or not axonal trauma can be identified within regions of white matter ischemia — a debate with very significant implications. Immunohistochemistry is often used not only to document axonal injury, but also to estimate the time since injury. As a result, the estimated post-injury interval may then be used by law enforcement officers and prosecutors to narrow “exclusive opportunity” and thus, identify potential suspects. Fundamental to these highly complicated and controversial topics is a philosophical understanding of the diffuse axonal injury spectrum disorders.

Keywords: Forensic pathology, Neuropathology, Pediatric forensic pathology, Child abuse, Diffuse axonal injury

Introduction

The investigation of all allegedly criminal infant and child deaths is complicated. The forensic pathologist challenged with such cases finds himself/herself responsible for answering far more questions than usual, and with greater depth. For example, unlike many “routine” adult homicide cases where the forensic pathologist serves primarily to communicate indisputable anatomic details such as gunshot wound pathways, when inflicted blunt head trauma is suggested in an infant or young child, the avenues to medical “truth” and “reasonable degree of medical certainty” can be dramatically more circuitous. Furthermore, forensic pathologists understand that their work product in such cases will be subject to a high level of scrutiny, and that their opinions will be rigorously tested. For this reason, the National Association of Medical Examiners (NAME) – the professional organization of forensic pathologists, death investigators and administrators – authored an official position paper outlining the minimum recommendations for standard of care in infant and young child autopsies when head trauma is alleged or suspected (1). That position paper contains guidance for the neuropathologic study of the pediatric brain, including suggestions for the evaluation of diffuse traumatic axonal injury (TAI).

Few medical and scientific concepts are debated with the vigor often observed in discussions about the so-called “shaken baby syndrome” and other forms of inflicted head trauma. Illustrative of the controversy is the recent publication of survey-derived data evaluating mainstream theories of causation for findings considered typical of allegedly shaken infants (2). This research was seemingly performed to report on the medical community's general acceptance of shaking as a cause of infant injury and death. The idea that shaking could injure or kill an infant is nearly fifty years old (3). As such, the mere necessity of such a survey underscores the overarching controversies.

When an infant or young child dies with obvious impact-type blunt head trauma (e.g., skull fractures with underlying intracranial hemorrhages with or without cerebrocortical contusions), the cause of death is seldom in dispute. Rather, the circumstances of death – and thus manner of death – may be contentious. These cases are categorically disparate from those infants who present with “encephalopathy, thin subdural hemorrhages and retinal hemorrhages – the triad indicating 'shaken baby syndrome'” (4). While reviews, including governmental inquiries, of the pathology and significance of the triad of shaken infants have been reported elsewhere (5) and are well beyond the scope of this paper, the often ill-defined concept of “encephalopathy” is paramount to the purpose of this paper. Although some authors assert that the encephalopathy of shaken baby syndrome is in fact diffuse axonal injury (DAI) related to shearing forces and thus physical tearing of axons (6–9), other authors refute that supposition (10–15), stating instead that oxygen deprivation is the underlying cause of the axonopathy.

Whether or not axonal injury in an infant is due to physical trauma or is secondary to anoxia may have critical implications (see case examples in Table 1), particularly in infants with the above-described “pure triad.” For example, misdiagnosing vascular axonal injury (VAI) as TAI could result in the erroneous conclusion that a child dying of natural disease was actually the victim of inflicted head trauma (16). This scenario would represent a grave miscarriage of justice. On the other hand, failing to investigate for and document TAI would deprive the criminal justice system with important evidence from which the pathologist can safely interpret the likely post-injury behavior of the infant or child. For example, a child with classic TAI would be expected to be immediately and continuously unconscious (17, 18), clearly abnormal to adult observers, and likely dying.

Table 1.

Illustrative Case Study of the Importance of Diffuse Axonal Injury Interpretations in Two Examples of Infants with the So-called “Pure Triad” of Alleged Shaking

| Case | Impact | RH | SDH | SAH | CCC | DAI | DAI-int | Opinions Frequently Offered |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | TAI | 1) Inflicted blunt head trauma; mechanism of injury thought to be direct impact without evidence due to anatomic plasticity of youth, shaking, or both |

| 2) Accidental blunt head trauma; mechanism of injury thought to be direct impact without evidence due to anatomic plasticity of youth | ||||||||

| 2 | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | VAI | 1) Inflicted blunt head trauma; mechanism of injury thought to be direct impact without evidence due to anatomic plasticity of youth, shaking, or both |

| 2) Accidental blunt head trauma; mechanism of injury thought to be direct impact without evidence due to anatomic plasticity of youth | ||||||||

| 3) Nontraumatic death with VAI and “triad” due to the complications of some other underlying condition |

RH – Retinal hemorrhages (meant to be numerous, extending from the posterior pole to the ora serrata, multilayered)

SDH – Subdural hemorrhage (meant to be thin, bilateral)

SAH – Subarachnoid hemorrhage

CCC – Cerebrocortical contusion

DAI – Diffuse axonal injury

DAI-int – Diffuse axonal injury pattern interpretation (with amyloid precursor protein immunohistochemistry)

TAI – Traumatic axonal injury

VAI – Vascular axonal injury

Regardless of the fine details intrinsic to this controversy and any “side” that a given pathologist might take on the diagnostic significance of the triad, the knowledge and skills necessary to recognize, document, and interpret DAI remains important to the evaluation of infant head trauma deaths.

Discussion

Terminology

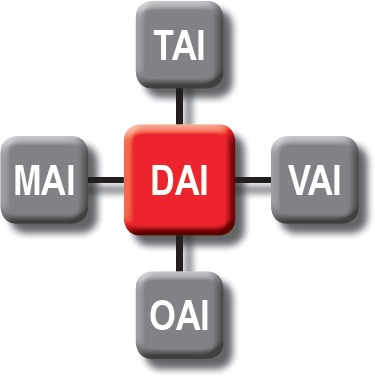

Diffuse axonal injury was originally used as a label for a relatively discrete clinicopathologic entity associated with widespread trauma of axons throughout the brain (19, 20). Unfortunately, over time, the term has changed within medical parlance to mean virtually any cause of axonal pathology (21). Extrapolating from the work of Dolinak and Matshes (22), we propose that axonal injury exists within a spectrum of overlapping neuropathologic abnormalities as illustrated in Figure 1. In short, DAI can be due to trauma (traumatic axonal injury; TAI), ischemia/anoxia (vascular axonal injury; VAI), metabolic derangements (metabolic axonal injury; MAI) and a wide variety of uncommon abnormalities (“other” axonal injury; OAI).

Figure 1.

Neuropathologic classification of the diffuse axonal injury spectrum.

DAI – Diffuse axonal injury

TAI – Traumatic axonal injury

MAI – Metabolic axonal injury

VAI – Vascular axonal injury

OAI – “Other” axonal injury

Brief History of the “Diffuse Axonal Injury” Label

“Diffuse degeneration of the cerebral white matter” was first described by Strich in 1956 in a series of patients with severe post-traumatic dementia (23). Other researchers released supportive findings in relatively short succession (24–27). Fundamentally, the entity of diffuse white matter damage was thought to be caused by the physical or mechanical shearing of axons at the moment of injury (27, 28). It was Adams in 1982 who ultimately coined the term “diffuse axonal injury” and recognized it as a clinicopathologic entity (29); over time, it was recognized that this condition existed along a spectrum (30). In their landmark paper, Adams et al. defined DAI as

… the occurrence of diffuse damage to axons in the cerebral hemispheres, in the corpus callosum, in the brainstem and sometimes also in the cerebellum resulting from head injury (30).

They described three grades of increasing severity: Grade 1 being microscopic evidence only, Grade 2 being focal lesions in the corpus callosum, and Grade 3 being focal lesions in the corpus callosum and in the brain stem (30).

Early researchers were limited in their observations until the development of immunohistochemistry and the advent of amyloid precursor protein (APP) labeling of axons. Specifically, it was felt that the immunostaining pattern and distribution, as well as the cytologic staining characteristics, could be used to assist in determining the origin of the axonal injury (17, 19, 31). As such, some authors advocated for more specific labeling of the pathologic entities to recognize the underlying etiology (17, 20, 32). This is recognized in our classification of the axonal injury spectrum disorders.

Pathophysiology of Diffuse Axonal Injury

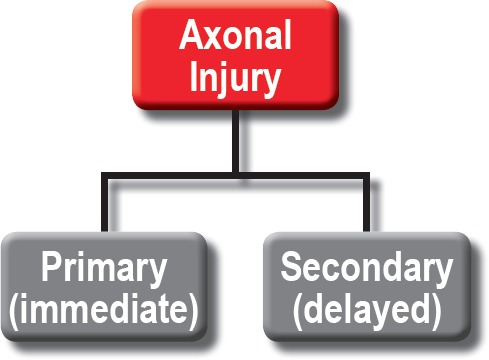

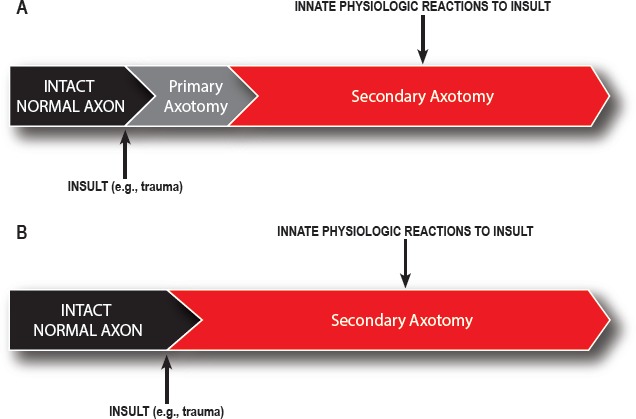

Over time, DAI has come to be recognized as a state of widespread axonal disconnection that disrupts normal excitatory and inhibitory networks (33). Axonal injury can be viewed as being due to 1) some initial insult (i.e., the primary insult) and 2) the subsequent innate reactions to that insult (i.e., the secondary insult; see Figure 2). However, in the vast majority of literature about DAI, the terms “primary insult” or “primary axotomy” refer specifically to the physical injury of the axon that happens at the time of blunt (including rotational) trauma. This is the “shearing” injury that has been classically described. Similarly in this context, the “secondary axotomy” is axonal disruption that occurs as the result of locoregional biochemical and metabolic collapse (Figure 3). This subtle but important distinction must be kept in mind during any study of the expanding subject literature.

Figure 2.

Broad classification of axonal injury.

Figure 3.

Broad classification of axotomies.

Although this section is meant to facilitate an understanding of axonal disruption and the formation of dystrophic axons, evidence exists to support the concept that primary insults like trauma can instead cause collapse of the cytoskeleton with rapid axonal destruction in the absence of bulb formation (33, 34). Hence, any histologic or immunohistochemical assessment for axonal “swelling” will “underestimate the burden of axonal injury” (Figures 3A and 3B) (33).

Primary Axotomy of Trauma

Classically, TAI has been described as being caused by stretching and shearing of the axons of the long white matter tracts (35) due to severe rotational acceleration and deceleration forces (9, 36–38). Research has shown that TAI can result because of impact blunt trauma, acceleration/deceleration motions, or some combination of the two (39), with resultant shearing or tearing of axons (40). While whether or not shaking alone can shear axons remains controversial, any infant, child, or adult with impact head trauma is at an undeniable risk of DAI (including both TAI and VAI). At least one author has gone so far as to assert that although

… it has been clearly shown experimentally that the forces of acceleration and deceleration are sufficient for producing the injury, with no direct impact to the head, we are aware that it rarely happens in the real world. Almost always, the direct impact to the head (either a blow or a fall) comes first (17).

Readers must be cautioned, though, that this reference is made to head injuries in general and was not made in specific reference to pediatric cases, or cases of alleged shaking.

The original DAI research in the 1950s and 1960s proposed that axonal injury was caused by tearing of the axons at the time of injury, followed by retraction of the fiber into the retraction bulb (23, 27, 40). Since then, it has been proven through numerous studies that only a small population of axons is mechanically severed at the time of impact (primary axotomy) (41). These studies have shown that the vast majority of axonal injury is caused by secondary axotomy, which is the delayed consequence of impaired axoplasmic transport (17, 20); these complications develop over hours to days after injury (42, 43).

Primary Axotomy of Ischemia and other Nontraumatic Causes

Regardless of the nature of the primary insult, the pathophysiology of DAI is relatively limited. The similarities of the cellular and subcellular progression of DAI from trauma (TAI) and anoxia/ischemia (VAI) have been studied and reported (44). Fundamentally, they involve a variably short-lived insult causing loss of axonal integrity (primary insult) and subsequently, axonal function (secondary consequences), with formation of dystrophic axons (45, 46). As such, the axonal retraction bulb once considered characteristic of trauma is now recognized as occurring under a wide variety of circumstances including ischemia (47, 48). In fact, one major recent study concluded that axonal injury complicating some stroke cases (without any evidence of trauma) was indistinguishable from that considered specific for trauma (49).

Secondary Axotomy of Any Cause

Diffuse axonal injury is a heterogenous entity that involves injuries from oxidative, excitotoxic, and inflammatory cascades (50) that follow an initial axonal perturbation (33). Easily conceptualized in the case of trauma where a subpopulation of axons will be sheared at the moment of injury, the secondary processes, which cause the vast majority of axonopathy even in trauma causes, stem from derangement of cellular architecture (e.g., cytoskeleton) and biochemical processes (including altered membrane permeability with subsequent cell membrane depolarization) (50). This triggers the release of glutamate and other neurotransmitters. The rapid, excessive release of glutamate triggers stimulation of N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) glutamate receptors (33), which ultimately results in a massive influx of sodium and calcium and an associated massive extracellular accumulation of potassium (33, 51, 52). Calcium may also be released intracellularly by the endoplasmic reticulum (33, 50).

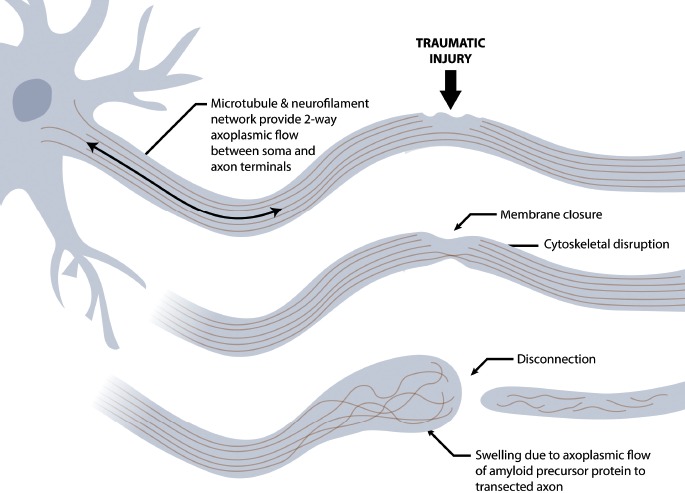

The presence of excess intracellular calcium activates calcium-dependent proteases (calpains and caspases) (33, 53). Calpain and caspase are involved in cellular necrosis and apoptosis (53). These proteolytic enzymes play a core role in the subsequent pathogenesis of axonal injury via proteolytic digestion of spectrin (41), dephosphorlyation and proteolysis of neurofilaments (53), and cleavage of microtubule associated protein-tau (50). These events cause breakdown of the axonal cytoskeleton and microtubule disassembly (54). Changes in the cytoskeleton derange axonal transport, which causes accumulation of substances like amyloid precursor protein at the site of axonal damage (50), leading to axonal swellings, varicosities, and axonal retraction balls/bulbs (Figure 4) (54). Eventually, if the axons become too swollen, they disconnect (55, 56). The detached distal segment ultimately undergoes Wallerian degeneration, while the proximal segments swells, with or without subsequent cell death (51).

Figure 4.

Schematic illustrating the post-traumatic formation of axonal retraction bulbs following disruption of the cytoskeleton. Created under contract by professional medical illustrator Diana Kryski.

Mitochondrial changes, including opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore, result from calcium overloading and calpain activation. This allows influx of water and loss of the electrochemical gradient, ultimately leading to mitochondrial dysfunction and death (50). The consequences of mitochondrial dysfunction include 1) increased activation of the caspases, 2) lactate production through glycolysis, 3) deranged oxidative metabolism, and ultimately 4) neuronal apoptosis (52, 54). Importantly, the consequences of these biochemical changes include ischemia complicating cerebral edema, increased cerebral blood flow, and acidosis – all causing further neuronal injury (52, 54). Associated and secondary inflammatory processes and activation of microglia also contribute to the severity of injury long after the initial insult (57, 58).

Philosophical Approach to the Evaluation of Pediatric Brains for Diffuse Axonal Injury

A stepwise approach to the pathologic diagnosis of DAI (and its subtypes) is well beyond the scope of this conceptual paper. That said, it is fair to promote the evaluation of axonopathy in the pediatric population as being necessarily multilayered. In each case of allegedly inflicted head trauma, the forensic pathologist should seek as much data as possible from traditional sources, including investigative information and hospital records (including especially computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging raw data), and integrate this evidence into what is learned from dissection and microscopic examination of the nervous system, including the results of immunohistochemistry. When faced with cases that challenge the diagnostic comfort of the forensic pathologist, consultation with others may prove appropriate. In evaluating a case, the sage forensic pathologist will avoid falling into two separate but interrelated thought traps that threaten their capacity to recognize, document, and interpret axonopathy in infants.

Thought Trap #1: The Autopsy is Always the Gold Standard

Over centuries the autopsy has established itself as a medical tool of great significance. Unfortunately, even the most thorough autopsy may fail to allow a forensic pathologist to determine the etiology of axonal injury. The overwhelming reason for this failure is the reality that most infants and young children dying under criminally suspicious circumstances will first be admitted to critical care settings where they develop the complications of brain swelling and anoxic encephalopathy. In that context, VAI can be widespread and entirely wipeout the evidence, if any, of TAI. As such, the forensic pathologist must be keenly aware of any and all medical evidence obtained at or near the time of initial hospitalization, prior to the onset of the secondary complications of brain swelling and anoxia. Of critical importance are the results of early imaging studies (see below). Forensic pathologists frequently think to review the radiology reports; however, few forensic pathologists interrogate the actual radiology images – alone or in consultation with a neuroradiologist. It is important to consider that radiologists often focus on reporting information of value in the diagnosis and prognostication of underlying disease and injury; more detailed information of value to a medicolegal death investigation may need to be directly sought.

Thought Trap #2: The Scope of Practice of a Consultant Neuropathologist Starts and Ends with the Contents of the Specimen Bucket

There is a tendency for consultations performed for forensic pathologists by neuropathologists to be “bucket-based,” that is, to be limited entirely to the contents of a specimen bucket. To that end, it is not uncommon for medical examiners to provide 1) a very truncated case history, 2) no systemic autopsy photographs, 3) no or limited medical records, 4) no digital radiology (DICOM) data, and/or 5) the brain without the dura mater, spinal cord or cervical spine.

The explanations for this minimized access to data are numerous and include a common cultural expectation or procedural routine that the consultant neuropathologist will examine the specimen in isolation, and produce a list of findings for the forensic pathologist to interpret. When the neuropathologist is used in such a minimalistic fashion, the forensic pathologist may lose a valuable opportunity for high-level consultation. A well-informed and well-resourced neuropathologist privy to the totality of case information will be better equipped to answer important questions. Some medical examiners are of the belief that providing detailed investigative and medical information to their consultant neuropathologist risks causing bias. We disagree with this notion, and, rather, embrace the experience of being enabled to provide more accurate diagnoses and expert opinions when privy to a robust dataset.

As stated previously, the forensic pathologist responsible for investigating the criminally suspicious alleged blunt head trauma death of an infant or young child will be capable of answering more questions, and with greater depth, when they thoroughly interrogate all of the available medical evidence. To that end, the pathologist should be able to understand the basic and relevant applied principles of radiology, macro- and microscopic neuropathology, and immunohistochemistry (Table 2 through Table 6), and should be empowered to thoroughly review and (hopefully) understand the work product of any consultants they choose to employ. Despite all of this detailed work, and ardent attention to detail, in the vast majority of cases, there is no way to differentiate trauma from other causes of axonal injury.

Table 2.

Checklist of “Ideal” Medical Evidence to be Reviewed During the Evaluation of Diffuse Axonal Injury in the Pediatric Population

| Evidence | Type |

|---|---|

| Antemortem imaging |

|

| Macroscopic neuropathology |

|

| Microscopic neuropathology |

|

| Immunohistochemistry |

|

Table 6.

Summary of the Role and Utility of Immunohistochemistry in the Assessment of Diffuse Axonal Injury

| Modality | Utility | Identify Etiology | Earliest Detection | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amyloid precursor protein (APP) |

|

Unlikely due to simultaneous staining of ischemic axons; classic teachings suggest cytomorphology might differentiate trauma from ischemia, but only reliably in the absence of ischemia | 35 minutes; two to three hours more typical* | (16, 19, 21, 31, 36, 50, 53, 74–79) |

| Neurofilament | • Sensitive for early axonal injury (especially the 68 kD subunit) | No | 60 minutes to six hours | (80, 81) |

| Neuron specific enolase (NSE) |

|

No | 90 minutes | (82) |

| CD68 |

|

No | Days | (12, 75) |

| Ubiquitin | • Sensitive for axonal injury | No | Six hours | (80, 83) |

| Alph a II-spectrin N-terminal fragment (SNTF) | • Very sensitive, but less so than APP; may identify a subpopulation of axons missed when APP is used alone | No | Unknown; possibly six hours | (84) |

To properly interpret positive and negative stains and to make timeline estimates, users must understand their antibody at a very high level, including which epitope of the protein is being detected.

Table 3.

Summary of the Role and Utility of Antemortem Imaging in the Assessment of Diffuse Axonal Injury

| Modality | Utility | Identify Etiology | Earliest Detection | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Computed tomography (CT) |

|

No | Most likely cannot detect axonal injury | (50, 59–67) |

| Conventional magnetic resonance imaging (cMRI) |

|

Possibly | No less than one day post-injury (T2 sequence) | (18, 50, 61, 62, 64, 65, 68–72) |

| Susceptibility weighted imaging (SWI) |

|

Possibly | No less than one day post-injury | (50, 60–62, 64, 67, 68, 73) |

| Diffusion weighted imaging (DWI) |

|

Unlikely | Three hours | (60, 61, 64, 67, 69, 71, 72) |

| Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) |

|

Unlikely | Uncertain; may be as early as three hours or as late as seven days | (18, 61, 64, 65, 67, 73) |

DAI – Diffuse axonal injury

T2 GRE – Gradient recalled echo

FLAIR – Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery

Table 4.

Summary of the Classical Macroscopic Pathology of Traumatic Axonal Injury

| Anatomic Compartment | Abnormality |

|---|---|

| Systemic autopsy results |

|

| Dura mater |

|

| Brain |

|

Table 5.

Summary of the Role and Utility of Hematoxylin and Eosin Histology and Special Stains in the Assessment of Diffuse Axonal Injury

Conclusions

Alleged pediatric blunt head trauma deaths are usually very complicated and laborious to investigate, and conclusions are often hotly contested. One neuropathologic issue of frequent concern is DAI and whether 1) TAI can be distinguished from VAI in the frequent circumstance when brain swelling and anoxia are discovered, and 2) whether shaking alone can cause TAI in infants. These issues are so contentious that consensus based on science alone seems unlikely anytime in the near future. As such, the pathologist challenged with such cases may find it easier to understand axonal injury, and interpret the results of their studies, when strengthened by a greater breadth of medical evidence. Multidisciplinary consultation may prove to be highly useful in this regard.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors have indicated that they do not have financial relationships to disclose that are relevant to this manuscript

ETHICAL APPROVAL

As per Journal Policies, ethical approval was not required for this manuscript

STATEMENT OF HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

This article does not contain any studies conducted with animals or on living human subjects

STATEMENT OF INFORMED CONSENT

No identifiable personal data were presented in this manuscsript

DISCLOSURES & DECLARATION OF CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors, reviewers, editors, and publication staff do not report any relevant conflicts of interest

References

- 1.Gill J.R., Andrew T., Gilliland M.G.F. et al. National Association of Medical Examiners position paper: Recommendations for the postmortem assessment of suspected head trauma in infants and young children. Acad Forensic Pathol. 2014. Jun; 4(2): 206–13. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Narang S.K., Estrada C., Greenberg S., Lindberg D. Acceptance of shaken baby syndrome and abusive head trauma as medical diagnoses. J Pediatr. 2016. Oct; 177: 273–8. PMID: 27458075. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guthkelch A.N. Infantile subdural haematoma and its relationship to whiplash injuries. Br Med J. 1971. May 22; 2(5759): 430–1. PMID: 5576003. PMCID: PMC1796151. 10.1136/bmj.2.5759.430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Richards P.G., Bertocci G.E., Bonshek R.E. et al. Shaken baby syndrome. Arch Dis Child. 2006. Mar; 91(3): 205–6. PMID: 16492880. PMCID: PMC2065913. 10.1136/adc.2005.090761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Committee report to the Attorney General: Shaken baby death review [Internet]. Toronto: Government of Ontario; 2011. Available from: https://www.attorneygeneral.jus.gov.on.ca/english/about/pubs/sbdrt/sbdrt.html. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Case M.E., Graham M.A., Handy T.C. et al. Position paper on fatal abusive head injuries in infants and young children. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2001. Jun; 22(2): 112–22. PMID: 11394743. 10.1097/00000433-200106000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Case M.E. Abusive head injuries in infants and young children. Leg Med (Tokyo). 2007. Mar; 9(2): 83–7. PMID: 17276126. 10.1016/j.legalmed.2006.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Case M.E. Forensic pathology of child brain trauma. Brain Pathol. 2008. Oct; 18(4): 562–4. PMID: 18782167. 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2008.00202.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Case M.E. Inflicted traumatic brain injury in infants and young children. Brain Pathol. 2008. Oct; 18(4): 571–82. PMID: 18782169. 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2008.00204.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geddes J.F., Vowles G.H., Hackshaw A.K. et al. Neuropathology of inflicted head injury in children. II. Microscopic brain injury in infants. Brain. 2001. Jul; 124(Pt 7): 1299–306. PMID: 11408325. 10.1093/brain/124.7.1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Geddes J.F., Hackshaw A.K., Vowles G.H. et al. Neuropathology of inflicted head injury in children. I. Patterns of brain damage. Brain. 2001. Jul; 124(Pt 7): 1290–8. PMID: 11408324. 10.1093/brain/124.7.1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Squier W. The “Shaken Baby” syndrome: pathology and mechanisms. Acta Neuropathol. 2011. Nov; 122(5): 519–42. PMID: 21947257. 10.1007/s00401-011-0875-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Squier W. “Shaken baby syndrome” and forensic pathology. Forensic Sci Med Pathol. 2014. Jun; 10(2): 248–50. PMID: 24469888. 10.1007/s12024-014-9533-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matshes E., Evans R., Pinckard J. et al. Shaken infants die of neck trauma, not of brain trauma. Acad Forensic Pathol. 2011. Jul; 1(1): 82–91. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matschke J., Buttner A., Bergmann M. et al. Encephalopathy and death in infants with abusive head trauma is due to hypoxic-ischemic injury following local brain trauma to vital brainstem centers. Int J Legal Med. 2015. Jan; 129(1): 105–14. PMID: 25107298. 10.1007/s00414-014-1060-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson M.W., Stoll L., Rubio A. et al. Axonal injury in young pediatric head trauma: a comparison study of β-amyloid precursor protein (β-APP) immunohistochemical staining in traumatic and nontraumatic deaths. J Forensic Sci. 2011. Sep; 56(5): 1198–205. PMID: 21595698. PMCID: PMC4033609. 10.1111/j.1556-4029.2011.01814.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davceva N., Basheska N., Balazic J. Diffuse axonal injury-a distinct clinicopathological entity in closed head injuries. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2015. Sep; 36(3): 127–33 PMID: 26010053. 10.1097/PAF.0000000000000168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li X.Y., Feng D.F. Diffuse axonal injury: novel insights into detection and treatment. J Clin Neurosci. 2009. May; 16(5): 614–9. PMID: 19285410. 10.1016/j.jocn.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Geddes J.F., Whitwell H.L., Graham D.I. Traumatic axonal injury: practical issues for diagnosis in medicolegal cases. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2000. Apr; 26(2): 105–16. PMID: 10840273. 10.1046/j.1365-2990.2000.026002105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davceva N., Janevska V., Ilievski B. et al. Dilemmas concerning the diffuse axonal injury as a clinicopathological entity in forensic medical practice. J Forensic Leg Med. 2012. Oct; 19(7): 413–8. PMID: 22920765. 10.1016/j.jflm.2012.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reichard R.R., Smith C., Graham D.I. The significance of beta-APP immunoreactivity in forensic practice. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2005. Jun; 31(3): 304–13. PMID: 15885067. 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2005.00645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dolinak D., Matshes E.W., Lew E.O. Forensic pathology: principles and practice. Boston: Elsevier/Academic Press; 2005. 690 p. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strich S.J. Diffuse degeneration of the cerebral white matter in severe dementia following head injury. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1956. Aug; 19(3): 163–85. PMID: 13357957. PMCID: PMC497203. 10.1136/jnnp.19.3.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nevin N.C. Neuropathological changes in the white matter following head injury. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1967. Jan; 26(1): 77–84. PMID: 6022165. 10.1097/00005072-196701000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peerless S.J., Rewcastle N.B. Shear injuries of the brain. Can Med Assoc J. 1967. Mar 11; 96(10): 577–82. PMID: 6020206. PMCID: PMC1936040. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oppenheimer D.R. Microscopic lesions in the brain following head injury. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1968. Aug; 31(4): 299–306. PMID: 4176429. PMCID: PMC496365. 10.1136/jnnp.31.4.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adams H., Mitchell D.E., Graham D.I., Doyle D. Diffuse brain damage of immediate impact type. Its relationship to ‘primary brain-stem damage’ in head injury. Brain. 1977. Sep; 100(3): 489–502. PMID: 589428. 10.1093/brain/100.3.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dolinak D., Smith C., Graham D.I. Global hypoxia per se is an unusual cause of axonal injury. Acta Neuropathol. 2000. Nov; 100(5): 553–60. PMID: 11045678. 10.1007/s004010000218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adams J.H. Diffuse axonal injury in non-missile head injury. Injury. 1982. Mar; 13(5): 444–5. PMID: 7085064. 10.1016/0020-1383(82)90105-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adams J.H., Doyle D., Ford I. et al. Diffuse axonal injury in head injury: definition, diagnosis and grading. Histopathology. 1989. Jul; 15(1): 49–59. PMID: 2767623. 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1989.tb03040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Graham D.I., Smith C., Reichard R. et al. Trials and tribulations of using beta-amyloid precursor protein immunohistochemistry to evaluate traumatic brain injury in adults. Forensic Sci Int. 2004. Dec 16; 146(2-3): 89–96. PMID: 15542268. 10.1016/S0379-0738(03)00274-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meythaler J.M., Peduzzi J.D., Eleftheriou E., Novack T.A. Current concepts: diffuse axonal injury-associated traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001. Oct; 82(10): 1461–71. PMID: 11588754. 10.1053/apmr.2001.25137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McGinn M.J., Povlishock J.T. Pathophysiology of traumatic brain injury. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2016. Oct; 27(4): 397–407. PMID: 27637392. 10.1016/j.nec.2016.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marmarou C.R., Walker S.A., Davis C.L., Povlishock J.T. Quantitative analysis of the relationship between intra-axonal neurofilament compaction and impaired axonal transport following diffuse traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2005. Oct; 22(10): 1066–80. PMID: 16238484. 10.1089/neu.2005.22.1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ljungqvist J.C., Zetterberg H., Mitsis M. et al. Serum neurofilament light protein as a marker for diffuse axonal injury - results from a case series study. J Neurotrauma. 2016. Oct 13. [Epub ahead of print] PMID: 27539721. 10.1089/neu.2016.4496. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Oehmichen M., Meissner C., Schmidt V. et al. Axonal injury–a diagnostic tool in forensic neuropathology? A review. Forensic Sci Int. 1998. Jul 6; 95(1): 67–83. PMID: 9718672. 10.1016/s0379-0738(98)00075-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Adams J.H., Graham D.I., Murray L.S., Scott G. Diffuse axonal injury due to nonmissile head injury in humans: an analysis of 45 cases. Ann Neurol. 1982. Dec; 12(6): 557–63.PMID: 7159059. 10.1002/ana.410120610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sherriff F.E., Bridges L.R., Sivaloganathan S. Early detection of axonal injury after human head trauma using immunocytochemistry for beta-amyloid precursor protein. Acta Neuropathol. 1994; 87(1): 55–62. PMID: 8140894. 10.1007/s004010050056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gennarelli T.A. Mechanisms of brain injury. J Emerg Med. 1993; 11 Suppl 1: 5–11. PMID: 8445204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gennarelli T.A., Thibault L.E., Adams J.H. et al. Diffuse axonal injury and traumatic coma in the primate. Ann Neurol. 1982. Dec; 12(6): 564–74. PMID: 7159060. 10.1002/ana.410120611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Büki A., Povlishock J.T. All roads lead to disconnection?–Traumatic axonal injury revisited. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2006. Feb; 148(2): 181–93; discussion 193-4. PMID: 16362181. 10.1007/s00701-005-0674-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith D.H., Meaney D.F., Shull W.H. Diffuse axonal injury in head trauma. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2003. Jul-Aug; 18(4): 307–16. PMID: 16222127. 10.1097/00001199-200307000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Povlishock J.T., Christman C.W. The pathobiology of traumatically induced axonal injury in animals and humans: a review of current thoughts. J Neurotrauma. 1995. Aug; 12(4): 555–64. PMID: 8683606. 10.1089/neu.1995.12.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bramlett H.M., Dietrich W.D. Pathophysiology of cerebral ischemia and brain trauma: similarities and differences. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2004. Feb; 24(2): 133–50. PMID: 14747740. 10.1097/01.WCB.0000111614.19196.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kalaria R.N., Bhatti S.U., Lust W.D., Perry G. The amyloid precursor protein in ischemic brain injury and chronic hypoperfusion. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1993. Sep 24; 695: 190–3. PMID: 8239281. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb23050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kalaria R.N., Bhatti S.U., Palatinsky E.A. et al. Accumulation of the beta amyloid precursor protein at sites of ischemic injury in rat brain. Neuroreport. 1993. Feb; 4(2): 211–4. PMID: 8453062. 10.1097/00001756-199302000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kaur B., Rutty G.N., Timperley W.R. The possible role of hypoxia in the formation of axonal bulbs. J Clin Pathol. 1999. Mar; 52(3): 203–9. PMID: 10450180. PMCID: PMC501080. 10.1136/jcp.52.3.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Harrington D., Rutty G.N., Timperley W.R. beta -amyloid precursor protein positive axonal bulbs may form in non-head-injured patients. J Clin Forensic Med. 2000. Mar; 7(1): 19–25. PMID: 16083644. 10.1054/jcfm.2000.0359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.MacKenzie J.M. Axonal injury in stroke: a forensic neuropathology perspective. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2015. Sep; 36(3): 172–5. PMID: 26266889. 10.1097/PAF.0000000000000166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Su E., Bell M. Translational research in traumatic brain injury. Boca Raton: CRC Press; c2016. Chapter 3, Diffuse axonal injury; p. 41–84. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fehily B., Fitzgerald M. Repeated mild traumatic brain injury: potential mechanisms of damage. Cell Transplant. 2016. Aug 5. [Epub ahead of print] PMID: 27502467. 10.3727/096368916X692807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Pearn M.L., Niesman I.R., Egawa J. et al. Pathophysiology associated with traumatic brain injury: current treatments and potential novel therapeutics. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2016. Jul 6. [Epub ahead of print] PMID: 27383839. 10.1007/s10571-016-0400-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Li J., Li X.Y., Feng D.F., Pan D.C. Biomarkers associated with diffuse traumatic axonal injury: exploring pathogenesis, early diagnosis, and prognosis. J Trauma. 2010. Dec; 69(6): 1610–8. PMID: 21150538. 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181f5a9ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zetterberg H., Smith D.H., Blennow K. Biomarkers of mild traumatic brain injury in cerebrospinal fluid and blood. Nat Rev Neurol. 2013. Apr; 9(4): 201–10. PMID: 23399646. PMCID: PMC4513656. 10.1038/nrneurol.2013.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Giza C.C., Hovda D.A. The Neurometabolic cascade of concussion. J Athl Train. 2001. Sep; 36(3): 228–235. PMID: 12937489. PMCID: PMC155411. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Barkhoudarian G., Hovda D.A., Giza C.C. The molecular pathophysiology of concussive brain injury. Clin Sports Med. 2011. Jan; 30(1): 33–48, vii-iii. PMID: 21074080. 10.1016/j.csm.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Loane D.J., Byrnes K.R. Role of microglia in neurotrauma. Neurotherapeutics. 2010. Oct; 7(4): 366–77. PMID: 20880501. PMCID: PMC2948548. 10.1016/j.nurt.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gentleman S.M., Leclercq P.D., Moyes L. et al. Long-term intracerebral inflammatory response after traumatic brain injury. Forensic Sci Int. 2004. Dec 16; 146(2-3): 97–104. PMID: 15542269. 10.1016/j.forsciint.2004.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Currie S., Saleem N., Straiton J.A. et al. Imaging assessment of traumatic brain injury. Postgrad Med J. 2016. Jan; 92(1083): 41–50. PMID: 26621823. 10.1136/postgradmedj-2014-133211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Demaerel P. MR imaging in inflicted brain injury. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2012. Feb; 20(1): 35–44 PMID: 22118591. 10.1016/j.mric.2011.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Suskauer S.J., Huisman T.A. Neuroimaging in pediatric traumatic brain injury: current and future predictors of functional outcome. Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2009; 15(2): 117–23. PMID: 19489082. PMCID: PMC3167090. 10.1002/ddrr.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tong K.A., Ashwal S., Holshouser B.A. et al. Diffuse axonal injury in children: clinical correlation with hemorrhagic lesions. Ann Neurol. 2004. Jul; 56(1): 36–50. PMID: 15236400. 10.1002/ana.20123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jaspan T., Griffiths P.D., McConachie N.S., Punt J.A. Neuroimaging for non-accidental head injury in childhood: a proposed protocol. Clin Radiol. 2003. Jan; 58(1): 44–53. PMID: 12565205. 10.1053/crad.2002.1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Metting Z., Rodiger L.A., De Keyser J., Van der Naalt J. Structural and functional neuroimaging in mild-to-moderate head injury. Lancet Neurol. 2007. Aug; 6(8): 699–710. PMID: 17638611. 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70191-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Arfanakis K., Haughton V.M., Carew J.D. et al. Diffusion tensor MR imaging in diffuse axonal injury. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2002. May; 23(5): 794–802.PMID: 12006280. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shekdar K. Imaging of Abusive Trauma. Indian J Pediatr. 2016. Jun; 83(6): 578–88. PMID: 26882906. 10.1007/s12098-016-2043-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ashwal S., Tong K.A., Ghosh N. et al. Application of advanced neuroimaging modalities in pediatric traumatic brain injury. J Child Neu-rol. 2014. Dec; 29(12): 1704–17. PMID: 24958007. PMCID: PMC4388155. 10.1177/0883073814538504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Niogi S.N., Mukherjee P. Diffusion tensor imaging of mild traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2010. Jul-Aug; 25(4): 241–55. PMID: 20611043. 10.1097/HTR.0b013e3181e52c2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chan Y.L., Chu W.C., Wong G.W., Yeung D.K. Diffusion-weighted MRI in shaken baby syndrome. Pediatr Radiol. 2003. Aug; 33(8): 574–7. PMID: 12783142. 10.1007/s00247-003-0949-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fujita M., Wei E.P., Povlishock J.T. Intensity- and interval-specific repetitive traumatic brain injury can evoke both axonal and microvascular damage. J Neurotrauma. 2012. Aug 10; 29(12): 2172–80 PMID: 22559115. PMCID: PMC3419839. 10.1089/neu.2012.2357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Huisman T.A., Sorensen A.G., Hergan K. et al. Diffusion-weighted imaging for the evaluation of diffuse axonal injury in closed head injury. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2003. Jan-Feb; 27(1): 5–11. PMID: 12544235. 10.1097/00004728-200301000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Huisman T.A., Schwamm L.H., Schaefer P.W. et al. Diffusion tensor imaging as potential biomarker of white matter injury in diffuse axonal injury. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2004. Mar; 25(3): 370–6. PMID: 15037457. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wu X., Kirov I.I., Gonen O. et al. MR imaging applications in mild traumatic brain injury: an imaging update. Radiology. 2016. Jun; 279(3): 693–707. PMID: 27183405. PMCID: PMC4886705. 10.1148/radiol.16142535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dolinak D., Matshes E.W. Forensic pathology: principles and practice. Boston: Elsevier/Academic Press; c2005. Chapter 19, Forensic neuropathology; p. 423–86. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hortobagyi T., Wise S., Hunt N. et al. Traumatic axonal damage in the brain can be detected using beta-APP immunohistochemistry within 35 min after head injury to human adults. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2007. Apr; 33(2): 226–37. PMID: 17359363. 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2006.00794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.McKenzie K.J., McLellan D.R., Gentleman S.M. et al. Is beta-APP a marker of axonal damage in short-surviving head injury? Acta Neuropathol. 1996. Dec; 92(6): 608–13. PMID: 8960319. 10.1007/s004010050568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dolinak D., Reichard R. An overview of inflicted head injury in infants and young children, with a review of beta-amyloid precursor protein immunohistochemistry. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006. May; 130(5): 712–7. PMID: 16683890. 10.1043/1543-2165(2006)130[712:AOOIHI]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Geddes J.F., Vowles G.H., Beer T.W., Ellison D.W. The diagnosis of diffuse axonal injury: implications for forensic practice. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 1997. Aug; 23(4): 339–47. PMID: 9292874. 10.1046/j.1365-2990.1997.4498044.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Oehmichen M., Schleiss D., Pedal I. et al. Shaken baby syndrome: re-examination of diffuse axonal injury as cause of death. Acta Neuropathol. 2008. Sep; 116(3): 317–29. PMID: 18365221. 10.1007/s00401-008-0356-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Oehmichen M., Auer R.N., König H.G. Forensic neuropathology and neurology. Berlin: Springer; 2006. 660 p. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Grady M.S., McLaughlin M.R., Christman C.W. et al. The use of antibodies targeted against the neurofilament subunits for the detection of diffuse axonal injury in humans. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1993. Mar; 52(2): 143–52. PMID: 8440996. 10.1097/00005072-199303000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ogata M., Tsuganezawa O. Neuron-specific enolase as an effective immunohistochemical marker for injured axons after fatal brain injury. Int J Legal Med. 1999; 113(1): 19–25. PMID: 10654234. 10.1007/s004140050273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Schweitzer J.B., Park M.R., Einhaus S.L., Robertson J.T. Ubiquitin marks the reactive swellings of diffuse axonal injury. Acta Neuropathol. 1993; 85(5): 503–7. PMID: 8388148. 10.1007/bf00230489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Johnson V.E., Stewart W., Weber M.T. et al. SNTF immunostaining reveals previously undetected axonal pathology in traumatic brain injury. Acta Neuropathol. 2016. Jan; 131(1): 115–35. PMID: 26589592. PMCID: PMC4780426. 10.1007/s00401-015-1506-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]