Abstract

Splash or spill scald burns may be seen by medical examiners in the setting of intentional trauma or accidental injury. In order to model various scald burn scenarios, an 8-year-old subject dressed in white had colored water spilled or dropped onto her. The results were recorded by video and still photography. Five trials were performed and included: liquid in a cup thrown towards the anterior body surfaces; liquid in a cup thrown towards the posterior body surfaces; a cup of liquid spilled across a table into the lap of a seated subject; a saucepan pulled down onto the anterior torso; and a cup of liquid spilled onto the top of the head. In each of the spill and splash models described above, a large often confluent zone of staining at the site of initial liquid contact with the body was often accompanied by elongate runoff patterns following gravity; droplet staining was often noted on adjacent areas. When seated, an inverted U-shaped staining pattern was on the buttocks. Anticipation of the splash event in one trial resulted in the subject instinctively turning the anterior body away from the oncoming liquid. When presented with a scalded victim, modeling of the reported history may provide a pattern of staining that supports or refutes the explanation offered for the burn. A mobile and neurologically intact subject who can anticipate an incipient scald injury may move prior to and during contact with the liquid resulting in unique staining patterns on multiple surfaces of the body.

Keywords: Forensic pathology, Scald, Burn, Abuse

Introduction

Burn related injuries constitute a significant source of pediatric injury and death. The National Science Council reports fire-related death rates due to unintentional injury as 0.6 (per 100 000 population) for children aged 0-4 years and 0.3 for children aged 5-14 years (1). Deaths related to fires are the third most common cause of death in the 5-9 year old age group and account for 9.4% of deaths; fire-related deaths are the fourth most common cause of death in the 1-4 year old age group (2.0% of deaths) and 10-14 year old age group (10.6% of deaths) (1). Unintentional pediatric burns exert a large financial burden on society, with hospitalization-related costs of these burns estimated at $212 million dollars in year 2000 (2).

Scald burns, due to contact with a hot liquid (typically hot water, coffee, tea or soup), most commonly occur in the pediatric age group and are the most common type of burn in children (3–5). Scald injuries are more common in younger children, while older children are more likely to suffer flame injuries (6, 7). Scald burns are the most common cause of intentional burn seen in children, and the pattern and distribution of these burns may be characteristic of how the burn was inflicted (8–12). Although abusive pediatric burns constitute less than 10% of all pediatric burns, these inflicted injuries tend to be associated with greater morbidity and mortality (11). The distribution and pattern of scald burns is thought to reflect the mechanism in which the burn was inflicted. For example, a child held in basin of hot water will have immersion lines with flexural crease sparing; children who pull down a hot liquid onto themselves from above tend have injuries involving the head, neck, upper extremities, and upper body (7–15).

When evaluating the distribution and pattern of burns in a scalded victim, several features have been described to help guide the interpretation towards accidental or inflicted. Characteristic of scald injuries more concerning for abuse include: immersion burns; a bilateral and symmetric burn pattern; greater than 10% of the total body surface area involved by full thickness burns; coexistent injuries; uniform scald depth; upper limb burns; symmetrical involvement of the extremities; isolated burns of the perineum, buttocks and lower extremity; bilateral and unilateral glove and stocking distribution; and sparing of skin in folds or on the central buttocks (8, 12). Burns associated with a history of a previous burn, abuse, neglect, domestic violence, faltering growth, differing historical accounts, lack of parental concern, and an unrelated adult presenting with the injured child are features which should raise suspicion of inflicted trauma (8). Features suggestive of an accidental scald include spill or flowing water injuries that cause burns on the head, neck, trunk and upper body with irregular burn margins and depths (8).

The current study was undertaken to model the pattern and distribution of scald burns expected based on what the author envisions as common possible mechanisms of pediatric scald injury.

Methods

Various scenarios that could result in scald injuries were modeled by exposing an 8-year-old developmentally appropriate subject clad in white clothing to 8 ounces of warm water tinted with blue watercolor paint. The test subject, the daughter of one of the authors (RA), willingly agreed to take part in this study. The first trial modeled a hot liquid being thrown towards the anterior surfaces of the standing subject. The water was thrown from a cup at a distance of approximately 1.3 m. The test subject was aware that the warm water was about to be thrown towards her, and she was instructed to stand still during the splash event. The second trial had water thrown from a cup at a distance of approximately 1.3 m towards the posterior surfaces of the standing subject. The test subject was not aware of when the water would be thrown and could not see when the water would impact her. The third trial had the subject seated at a table on which was a cup containing liquid. The cup was spilled such that liquid traveled several inches across the table and then flowed over the edge of the table onto the subject's lap. The fourth trial modeled a standing child pulling a saucepan off a stove onto herself; however, after multiple unsuccessful trials, an adult actually pulled the saucepan over. The fifth trial had water dumped directly onto the head of the seated subject from approximately 30 cm directly over her head.

Each episode was filmed and the subject was subsequently photographed to show the distribution of the staining of tinted water on her body. Eight still images were captured from each of the five videos. These images were chosen to best represent the dynamic sequence of events during each of the five trials. The choice of eight still image captures from each video was based on a careful review of the videos and was felt to represent a tradeoff between adequate documentation of the splash events without excessive sampling that was felt to add little additional information to the understanding of each splash sequence. The actual images captured at times corresponded to a frame-by-frame recording of the splash event; however, selective frame capture was performed if this was felt to best document a particular splash trial.

After each splash event, still photographs were taken of the test subject to document the splash pattern on her clothing. Standard photographs (with a 1 m ruler for scale) included full front, back, right lateral and left lateral pictures. Additional photographs were taken as deemed necessary to capture pertinent details of a particular splash pattern.

Results

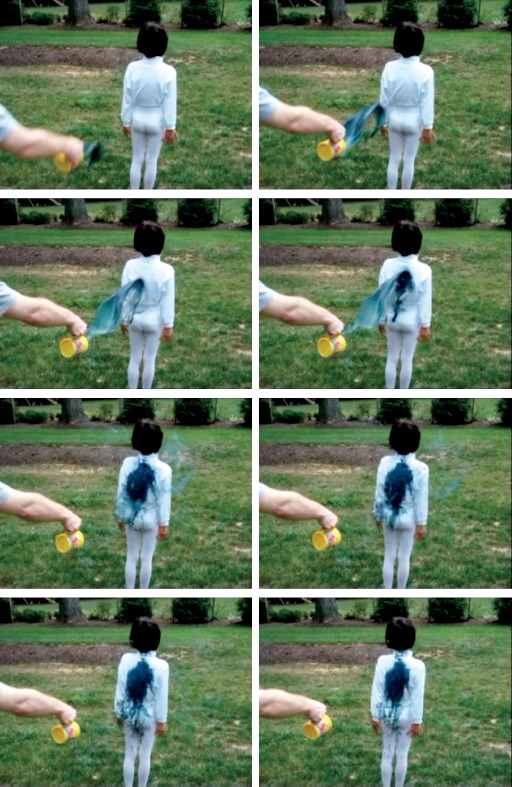

The video image sequence for Trial 1 (Image 1) shows that the subject, despite being instructed to stand still, rotated her body in anticipation of the splash event. As she pivoted on her right foot, she lifted and stepped with her left foot while rotating her body. This resulted in her presenting her left shoulder and upper extremity, and anterior thighs and groin area, to the oncoming liquid. By the end of the splash event, she had turned her body such that the left posterior aspect of her body was facing towards the direction from which the liquid was thrown. Photographs of the subject (Images 2 through 4) showed staining on various surfaces of the body reflecting her movement in anticipation of being hit with the liquid. An arrowhead shaped pattern of staining had its point on the left upper back and adjacent posterior shoulder, with one line of staining down the posterior left arm, and another line of staining wrapping around towards the anterior upper left arm. Flow lines along gravity extended inferiorly from this primary area of staining. Droplet staining (round or oval dot like staining) was on the left arm and forearm adjacent to the main area of staining. A larger area of more confluent staining was on the posterior and medial left forearm and wrist. An inverted U-shaped area of staining extended across the groin area and down each anterior thigh. Flow line staining along gravity extended prominently downward from the main area of staining. Scattered droplet staining was also noted around the main U-shaped staining, as well as on the feet. The chest, abdomen, and right lateral body were spared from staining.

Image 1.

Still image sequence captured from video of Trial 1, in which liquid in a cup was thrown towards the anterior body surfaces.

Image 2.

Photograph of staining pattern of Trial 1, in which liquid in a cup was thrown towards the anterior body surfaces.

Image 4.

Photograph of staining pattern of Trial 1, in which liquid in a cup was thrown towards the anterior body surfaces.

Image 3.

Photograph of staining pattern of Trial 1, in which liquid in a cup was thrown towards the anterior body surfaces.

The video image sequence for Trial 2 (Image 5) shows that subject stood still when she was unable to see and anticipate the splash. A photograph of the subject (Image 6) revealed a large confluent area of staining extending from the upper back to the left buttock at the primary impact site of the liquid. Focal staining along the posteromedial left forearm corresponded to impact of the liquid with this site. Splash from the initial liquid impact, as well as downward runoff, created elongate flow lines along gravity, and droplet staining that extended down from the buttocks onto the posterior aspects of the lower extremities. The anterior torso, upper extremities (except for the posteromedial left forearm as described above), and anterior aspects of the lower extremities were spared from staining.

Image 5.

Still image sequence captured from video of Trial 2, in which liquid in a cup was thrown towards the posterior body surfaces.

Image 6.

Photograph of staining pattern of Trial 2, in which liquid in a cup was thrown towards the posterior body surfaces.

The video image sequence for Trial 3 (Image 7) shows the flow of liquid off the table into the lap of the subject. Photographs of the subject (Images 8 and 9) showed confluent staining in the subject's lap (lower abdomen, groin, and anterior upper thighs) where the liquid initially impacted and then pooled. Runoff produced elongate flow lines along the anterior thighs, which was most pronounced medially where the liquid could follow gravity towards the seat of the chair. Splash from the initial liquid impact created minor droplet staining adjacent to the primary impact site and around runoff lines. An inverted “U” pattern was on the buttocks where in contact with the seat. Additional staining on the posterior thighs and legs corresponded to runoff from the seat, with some linear runoff lines and droplet staining on the posterior right leg to heel.

Image 7.

Still image sequence captured from video of Trial 3, in which a cup of liquid was spilled across a table into the lap of a seated subject.

Image 8.

Photograph of staining pattern of Trial 3, in which a cup of liquid was spilled across a table into the lap of a seated subject.

Image 9.

Photograph of staining pattern of Trial 3, in which a cup of liquid was spilled across a table into the lap of a seated subject.

The video image sequence for Trial 4 (Image 10) shows an initial impact of the liquid with the midline upper chest. As the pot fell, the site of liquid impact migrated downward towards the midline abdomen. A photograph of the subject (Image 11) showed confluent staining along the midline chest to abdomen that narrowed slightly at its most inferior extent. A few flow lines curved laterally and downward from the staining on the upper chest. Scant droplet staining was on the abdomen and thighs. The back and extremities (except as previously described) were spared from staining.

Image 10.

Still image sequence captured from video of Trial 4, in which a saucepan was pulled down onto the anterior torso.

Image 11.

Photograph of staining pattern of Trial 4, in which a saucepan was pulled down onto the anterior torso.

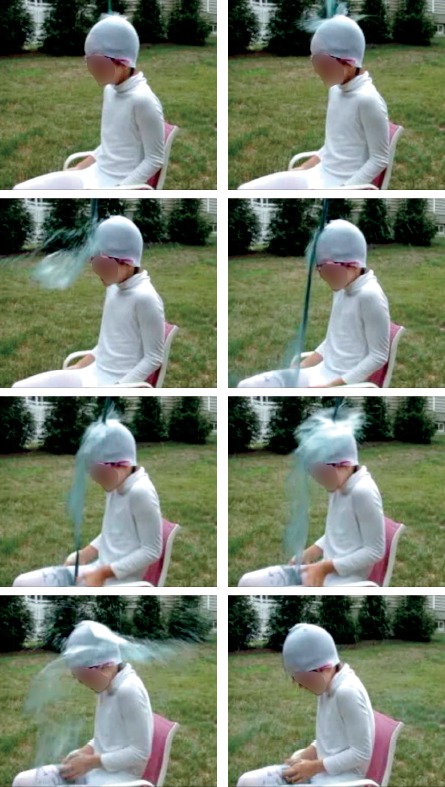

The video image sequence for Trial 5 (Image 12) shows liquid poured from a cup initially impacting the vertex of the head. The liquid impact side then shifted to the anterior aspect of the vertex with the majority of the runoff flowing off the forehead. The liquid then shifted back towards the vertex with runoff visible along the anterior and posterior head. The subject can be seen to flex at the neck and slightly in the back in response to the striking liquid. Photographs of the subject (Images 13 and 14) showed elongate flow lines extending from the vertex to the forehead and mid occipital area. The staining on the anterior head was more confluent in good correspondence to the flow pattern noted on the video. Minor elongate flow lines along gravity and droplet staining were most prominent adjacent to the main staining areas on the head. Fairly scant elongate flow lines and droplet staining were on the chest, abdomen and back. The extensive flow of liquid off the forehead pooled in the lap of the seated subject creating a staining pattern similar to that seen in Trial 3. Confluent staining on the groin and anterior thighs to knees was accompanied by runoff staining along the medial and lateral thighs, as well as minor adjacent droplet staining. As in Trial 3, an inverted “U” pattern was on the buttocks where in contact with the seat. Additional staining on the posterior legs corresponded to runoff from the seat.

Image 12.

Still image sequence captured from video of Trial 5, in which a cup of liquid was spilled onto the top of the head.

Image 13.

Photograph of staining pattern of Trial 5, in which a cup of liquid was spilled onto the top of the head.

Image 14.

Photograph of staining pattern of Trial 5, in which a cup of liquid was spilled onto the top of the head.

Discussion

Fairly unique patterns of staining were produced in the five different trials of this study. A basic test of the reliability of the modeling results would be to compare these staining patterns to the distribution of well-documented scald injuries. A child who pulled a hot cup of coffee onto herself off a table had an inverted V-shaped pattern of burning on the chest and abdomen with some elongate flow line burns that corresponded fairly well to the pattern of staining seen in Trial 4 of this study (10). A child who had hot water thrown onto his face had confluent facial burns with some adjacent spatter (droplet like) burns that corresponded reasonably well to the pattern seen in Trial 2 (10). A child who pulled a cup of hot tea off a table onto herself had a distribution of burning fairly reminiscent of the staining pattern seen in Trial 3 (10). It is important to realize that exact correspondence between scald burns and modeled staining was not realized; however, a similarity between the two could be appreciated.

Other reports from the literature seemed to be generally consistent with the modeling patterns observed in this study. For example, toddlers who pull down a container of hot liquid from above tend have scalds in a baby bib distribution that is wider at the top of the chest and narrows towards the lower chest and abdomen (similar to our Trial 4) (14). Accidental burns in children are most common in toddlers who suffer a scald due to the child pulling a cup or mug of hot liquid down onto themselves resulting in a burn that involves the face, arms and chest (16). Accidental cooking-related scald injuries in children tend to involve the head, neck, and upper body more than non-cooking burns (13). “Kettle burns” most commonly involve children under two years of age who pull on an electrical cord, and these burns typically involve the face, chest, abdomen and arms (15).

It is important to note that this study is a qualitative analysis since burn patterns are likely influenced by type of liquid, (e.g., oil versus water), liquid temperature, contact time with the offending agent, clothing, skin thickness, and functional ability of the victim to respond prior to and after injury. Indeed, variables reported to influence the risk of burn in a spilled beverage include the initial temperature of the liquid, volume of liquid, and cooling time before spill (17). Fluid properties associated with more severe scald burns include higher initial temperature, higher viscosity, greater thermal conductivity, and higher thermal capacity (18). Burns caused by semisolids or grease have been associated with greater morbidity compared to liquid burns (13). The importance of the actual scalding liquid is highlighted by reports of hot milk being associated with larger burns, a deeper depth of burning, and a more severe clinical course than hot water (19, 20). Children who suffer burns from starchy liquids (e.g., instant noodle soups) tend to be older and have burns in the perineal area as compared to hot liquids, which affect younger children with burns on the chest and abdomen (21).

An unexpected finding of this study was the complex staining pattern seen on multiple surfaces of the body when the test subject instinctively turned away from the oncoming liquid. In neurologically intact victims who have the ability to quickly react and physically respond to an anticipated splash injury, similar burn patterns may be seen on various surfaces of the body. It is important to note that burns on multiple body surfaces can occur in such a subject due to a single splash event. However, scald burns on multiple body surfaces may indeed suggest multiple splash events if the victim did not have the ability to anticipate and respond to an incipient splash event.

Multiple trials in this study showed elongate flow lines along gravity extending away from a more confluent area of staining at the primary impact site of the liquid. The distribution of these elongate runoff lines along gravity in this study may correspond to elongate zones of burn “flowing” away from the main scald location. It is possible that the plausibility of an offered mechanism for scalding of a victim can be evaluated if observed elongate scald injuries seem to go against gravity.

The actual contact time to cause a burn when exposed to hot water is dependent on the water temperature. Water at 55°C (131°F) will cause an infant to burn after a five-second contact time while water at 65°C (149°F) will cause near instantaneous burns (22). Water has to be at a temperature greater than 60-65.5°C (140-150°F) to have the potential to cause a splash burn due to rapid cooling of the liquid when splashed; other liquids with greater specific heats (e.g., oil) may cause these injuries at lower temperatures (10). This study only looked at staining patterns and ignored the effect of possible cooling of the liquid during a scalding event. It is thus important to recognize that modeling (as done in this study) is only a general guide to interpretation of actual scald burns.

Conclusion

The five trials described in this study showed unique features that may differentiate among different mechanisms of splash injury. It is hoped that such modeling can have particular utility when the putative mechanism of splash injury seems inconsistent with the observed scald injuries. Recreation of the reported mechanism of scalding can be performed to evaluate whether there is reasonable agreement between the observed burns and modeled stain patterns. It is anticipated that modeling of splash injuries may provide one additional source of information to be considered when evaluating scald burns in light of the scene investigation and reported history.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors have indicated that they do not have financial relationships to disclose that are relevant to this manuscript

ETHICAL APPROVAL

As per Journal Policies, ethical approval was not required for this manuscript

STATEMENT OF HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

This article does not contain any studies conducted with animals or on living human subjects

STATEMENT OF INFORMED CONSENT

No identifiable personal data were presented in this manuscsript

DISCLOSURES & DECLARATION OF CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors, reviewers, editors, and publication staff do not report any relevant conflicts of interest

References

- 1.Injury facts: 2015 Edition [Internet]. Itasca (IL): National Safety Council; 2015. [cited 2016 Oct 1]. 218 p. Available from: http://www.nsc.org/Membership%20Site%20Document%20Library/2015%20Injury%20Facts/NSC_InjuryFacts2015Ed.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shields B.J., Comstock R.D., Fernandez S.A. et al. Healthcare resource utilization and epidemiology of pediatric burn-associated hospitalizations, United States, 2000. J Burn Care Res. 2007. Nov-Dec; 28(6): 811–26. PMID: 17925649. 10.1097/BCR.0b013e3181599b51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sahu S.A., Agrawal K., Patel P.K. Scald burn, a preventable injury: analysis of 4306 patients from a major tertiary care center. Burns. 2016. Jul 16. pii: S0305-4179(16)30199-1. [Epub ahead of print]. PMID: 27436508. 10.1016/j.burns.2016.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Toon M.H., Maybauer D.M., Arceneaux L.L. et al. Children with burn injuries–assessment of trauma, neglect, violence and abuse. J Inj Violence Res. 2011. Jul; 3(2): 98–110. PMID: 21498973. PMCID: PMC3134932. 10.5249/jivr.v3i2.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rimmer R.B., Weigand S., Foster K.N. et al. Scald burns in young children–a review of Arizona burn center pediatric patients and a proposal for prevention in the Hispanic community. J Burn Care Res. 2008. Jul-Aug; 29(4): 595–605. PMID: 18535476. 10.1097/BCR.0b013e31817db8a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alharthy N., Al Mutairi M., AlQueflie S. et al. Pattern of burns identified in the Pediatrics Emergency Department at King Abdul-Aziz Medical City: Riyadh. J Nat Sci Biol Med. 2016. Jan-Jun; 7(1): 16–21. PMID: 27003963. PMCID: PMC4780160. 10.4103/0976-9668.175019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee C.J., Mahendraraj K., Houng A. et al. Pediatric burns: a single institution retrospective review of incidence, etiology, and outcomes in 2273 burn patients (1995-2013). J Burn Care Res. 2016. Nov/Dec; 37(6): e579–e585. PMID: 27294854. 10.1097/BCR.0000000000000362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maguire S., Moynihan S., Mann M. et al. A systematic review of the features that indicate intentional scalds in children. Burns. 2008. Dec; 34(8): 1072–81. PMID: 18538478. 10.1016/j.burns.2008.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spitz W.U., Spitz D.J. Spitz and Fisher's medicolegal investigation of death: guidelines for the application of pathology to crime investigation. 4th ed. Springfield (IL): Charles C Thomas; 2006. 1325 p. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alexander R. Child Fatality Review: an interdisciplinary guide and photographic reference. 1st ed. St Louis: G.W. Medical Publishing, Inc.; 2007. 832 p. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hodgman E.I., Pastorek R.A., Saeman M.R. et al. The Parkland Burn Center experience with 297 cases of child abuse from 1974 to 2010. Burns. 2016. Aug; 42(5): 1121–7. PMID: 27268012. 10.1016/j.burns.2016.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pawlik M.C., Kemp A., Maguire S. et al. Children with burns referred for child abuse evaluation: burn characteristics and co-existent injuries. Child Abuse Negl. 2016. May; 55: 52–61. PMID: 27088728. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bachier M., Hammond S.E., Williams R. et al. Pediatric scalds: do cooking-related burns have a higher injury burden? J Surg Res. 2015. Nov; 199(1): 230–6. PMID: 26076686. 10.1016/j.jss.2015.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hampton T., Vijayan R. Scalded toddlers: Can we predict the unpredictable? Burns. 2016. Sep; 42(6): 1357–8. PMID: 27317341. 10.1016/j.burns.2016.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holmes W.J., Keane B., Rode H. The severity of kettle burns and the dangers of the dangling cord. Burns. 2012. May; 38(3): 453–8. PMID: 22035886. 10.1016/j.burns.2011.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kemp A.M., Jones S., Lawson Z., Maguire S.A. Patterns of burns and scalds in children. Arch Dis Child. 2014. Apr; 99(4): 316–21. PMID: 24492796. 10.1136/archdischild-2013-304991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abraham J.P., Nelson-Cheeseman B.B., Sparrow E. et al. Comprehensive method to predict and quantify scald burns from beverage spills. Int J Hyperthermia. 2016. Dec; 32(8): 900–910. PMID: 27405847. 10.1080/02656736.2016.1211752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Loller C., Buxton G.A., Kerzmann T.L. Hot soup! Correlating the severity of liquid scald burns to fluid and biomedical properties. Burns. 2016. May; 42(3): 589–97. PMID: 26796241. 10.1016/j.burns.2015.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aliosmanoglu I., Aliosmanoglu C., Gul M. et al. The comparison of the effects of hot milk and hot water scald burns and factors effective for morbidity and mortality in preschool children. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2013. Apr; 39(2): 173–6. PMID: 26815076. 10.1007/s00068-012-0246-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yastı AÇ, Koç O., Şenel E., Kabalak A.A. Hot milk burns in children: a crucial issue among 764 scaldings. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2011. Sep; 17(5): 419–22. PMID: 22090327. 10.5505/tjtes.2011.95815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lavigne J.M., Patel B., Stockton K., McBride C.A. Starchy liquid burns do not have worse outcomes in children relative to hot beverage scalds. Burns. 2016. Jul 6. pii: S0305-4179(16)30183-8. [Epub ahead of print]. PMID: 27394079. 10.1016/j.burns.2016.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Dressler D.P., Hozid J.L. Thermal injury and child abuse: the medical evidence dilemma. J Burn Care Rehabil. 2001. Mar-Apr; 22(2): 180–5. PMID: 11302607. 10.1097/00004630-200103000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]