Abstract

Sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) became a named entity in 1969 and the term has been used to certify sudden unexpected infant deaths meeting certain demographic, epidemiologic, and pathologic criteria. Since it is a diagnosis of exclusion, there is inherent imprecision, and this has led the National Association of Medical Examiners to recommend that these deaths now be classified as “undetermined.” This historical review article briefly analyzes anecdotal instances of SIDS described centuries ago as overlying, smothering, infanticide, and suffocation by bedclothes followed by a more detailed review of “thymic” causes (i.e., thymic asthma and status thymicolymphaticus) popular in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Before the 1950s, such cases were also often categorized as accidental mechanical suffocation. In the 1940s and 1950s, forensic studies on infants dying unexpectedly revealed a typical pattern of autopsy findings strongly suggestive of natural causation and, after 1969, cases meeting the appropriate criteria were usually categorized as SIDS, a term embraced by the public and by advocacy groups. Research conducted after the 1960s identified important risk factors and generated many theories related to pathogenesis, such as prolonged sleep apnea. The incidence of SIDS deaths decreased sharply in the early 1990s after implementing public awareness programs addressing risk factors such as prone sleeping position and exposure to smoking. Deletion of cases in which death scene investigation suggested asphyxiation and cases where molecular autopsies revealed metabolic diseases further decreased the incidence. This historical essay lays the foundation for debate on the future of the SIDS entity.

Keywords: Forensic pathology, Sudden infant death syndrome, History of pathology, Constitutional pathology, Status thymicolymphaticus, Epistemology of disease, Sudden unexpected death in infancy, Sudden unexpected infant death, Unclassified sudden infant death

Introduction

When I was invited to write a brief history of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), a quick review of the literature revealed dozens of these. Most were written several decades ago by SIDS researchers with strong perspectives and who suffered from what historians call “presentism” (i.e., interpreting the past through current ideas and perspectives). Many of these papers simply repeated much of the same material, but with different emphases, and it was obvious that citing all of these secondary historical sources was impractical. Much of this historical literature has focused on either smothering/overlaying or thymic causes. I will discuss both of these briefly but will cite additional literature that the reader may refer to for greater depth. Since my goal was to write an historical piece that was original and a useful addition to the literature, I have mostly focused on the 20th and early 21st Centuries.

While I recognize that the SIDS “entity” is not a single entity and has only been called SIDS since 1969, and, even now, may be in the process of another reclassification, I will use the term SIDS throughout for the sake of both simplicity and brevity. However, when used in a clearly pre-1969 context, the term will be placed within quotation marks.

Discussion

Overlying, Smothering, Infanticide, and Suffocation by Bedclothes

Many SIDS histories start with a reference to a case in the Old Testament of the Bible: “And this woman's child died in the night; because she overlaid it” (1st Kings chapter 3: verse 19; King James version translation) as evidence that unexpected deaths of sleeping neonates, possibly representing examples of “SIDS”, occurred in antiquity. This is often reinforced by references discussing anecdotal examples of overlaying and accidental smothering from ancient Egypt, Babylon, Greece, Rome, European middle ages, Renaissance Europe, late modern period Europe, colonial America, and the American old south (1–3). Some of these reviews place overlaying into the context of differentiating it from infanticide and then note that infanticide, including accidental smothering, was a church issue throughout the medieval period and much of the Renaissance. S.G. Norvenius provides an excellent discussion of Catholic and Protestant punishments for accidental overlaying and infanticide (4). In 17th-18th century Florence, a wooden and iron arched device called an arcuccio or arcutio (which had a cut out opening for insertion of a breast) was placed over infants, presumably preventing mothers or wet nurses from rolling over onto nursing or sleeping babies while also preventing bedclothes from smothering the infant. The effectiveness of this device is unknown but nursing women in Florence could be excommunicated for not using it; these devices were available for purchase in 18th century England (1, 5).

By the early 19th century, infanticide had transitioned from ecclesiastical to secular courts. In England, compulsory registration of deaths was required after the passage of the Births and Deaths Registration Act of 1836/37. The 1887 Coroners Act required the coroner to differentiate between natural and unnatural deaths (6).

Shortly after this, one of the more detailed historically important studies related to overlaying was published in 1893 in the Edinburgh Medical Journal by Charles Templeman (7). He reported that 399 infants were found dead in bed with parents in Dundee from 1882 to 1891. While a number of SIDS histories have noted that his pathological and epidemiological findings are similar to those of SIDS (2, 5), Templeman attributed these deaths to parental drunkenness and ignorant, careless mothers and he suggested that it become mandatory for infants to sleep separately from parents (7).

The concept of overlaying, while undoubtedly responsible for some losses, lost most of its credibility as the primary explanation for these types of deaths when the use of cribs became common in the early 20th century and the magnitude of the problem did not substantially decrease. In fact, the response in England was simply a new name, “crib death,” and the usual explanation became accidental smothering by bedclothes. While suffocation by bedclothes was frequently diagnosed in the past, there have been numerous studies addressing this possible etiology and currently there is little credible evidence implicating dangerous bedding materials in SIDS (8).

Thymic Etiologies

Many previous histories of SIDS have discussed the role of the thymus at length. Warren Guntheroth has written a particularly good paper on this topic (9). Two somewhat overlapping thymic concepts are historically important.

The first is “thymic asthma.” When autopsies were initially performed on infants dying suddenly, it was noted that their thymuses were unusually large and it was believed that the enlarged thymus 1) impinged on the trachea or carotids thus obstructing the airway or blood flow to the head, 2) adversely stimulated the nerves controlling respiration, or 3) over-filled the thoracic cavity, adversely affecting the heart and lungs (1). Guntheroth links the origin of the concept of thymic asthma to J.H. Kopp in Heidelberg in 1829. But, by 1842, American physician Charles A. Lee had reviewed cases of infant death attributed to enlarged thymuses and noted that most of the reported cases actually lacked thymic measurements; Lee also found that, in those cases where thymic measurements had been reported, the measurements were no larger than in similar aged infants who had died of trauma. Lee concluded that thymic asthma did not exist (9, 10). Sixteen years later, German physician Alexander Friedleben published a comprehensive book on the thymus and concluded that it was normal for infants to have relatively large thymuses, that a normal, soft thymus could not cause airway obstruction, and that thymic asthma does not exist (9, 11). However, several prominent German pathologists continued to insist that it did. While there was never a solid basis for thymic asthma, the theory persisted in the minds of some prominent physicians for many years. It is likely that the concept of sudden death due to thymic asthma was derived from an even earlier concept “layrngismus stridulus”; this entity, characterized by noisy breathing and “crowing fits” in young children, was thought to be caused by tracheal obstruction by an enlarged thymus (6).

The other important thymic theory for sudden infant demise has generally been attributed to two publications by a Viennese physician, Arnold Paltauf, in Wiener Klinische Wochenschrift in 1889 and 1890 (12). However, as noted by Guntheroth, these publications were actually preceded by a paper by Paul Albert Grawitz, a German pathologist trained by Virchow in 1888. Grawitz:

… believed that an enlarged thymus played a role in suffocation, but he theorized that the thymic enlargement was secondary. The primary disorder he described was 'constitutional' … involving hyperplasia of the thymus, rickets, and a generalized swelling of lymph glands (9).

Less than two years later, Paltuaf:

… found no evidence of lethal pressure of the thymus on the trachea or blood vessels … [but] did agree with Grawitz that these victims of sudden death, adults and children, had an enlarged thymus, hyperplasia of the lymph glands, and an aorta that was 'excessively' small – all of which Paltauf took as signs of faulty body constitution, citing the 1872 monograph by Virchow on the chlorotic Constitution (9).

Paltauf's constitutional disorder, which could cause sudden death with little provocation, was soon named “status thymico-lymphaticus” (or “status lymphaticus”) by others. As noted by Savitt, Paltauf claimed:

… a complex of bodily changes based upon nutritional and constitutional deficiencies was the cause of sudden death of infants alone in cribs or in beds with parents (1).

While status thymicolymphaticus figures prominently in many histories of SIDS, these authors seem to have ignored the fact that this diagnosis was not uncommon in older children and adults in the late 1800s and early 1900s and that its association to “SIDS” was not the primary one. Status thymicolymphaticus was the leading and most important example of constitutional pathology, a theoretical concept important to German pathologists a hundred or more years ago. German medical historian Cay-Rüdiger Prüll provided excellent insights into this concept (13, 14). By the mid 19th century, autopsies were widely recognized as the scientific way to determine causes of death and this belief underpinned the pathologist's high status in the medical hierarchy; however, it was increasingly apparent that in some instances autopsies did not produce an anatomical cause of death and this worried Rudolph Virchow and other leading German pathologists. It is important to remember that by the late 19th century German pathologists and bacteriologists were having a “turf war,” and anatomic pathology's preeminence was being challenged by “the bacteriologists' claim to have found the cause of a number of diseases by discovering various types of bacteria” (13). Therefore, German pathologists, who had been locked out of the field of bacteriology in their own country by hygenists, “emphasised the significance of the human constitution and the 'inner' causes of disease” (13). Status thymicolymphaticus quickly became the “poster disease” for the concept of constitutional disorders and many clung onto this diagnosis even as copious evidence built up against its existence. In fact, over 800 papers were published on this topic between its “discovery” in 1889-90 and 1923 (6).

Throughout the 19th Century, regulations related to death certification became more and more stringent. Status thymicolymphaticus was often used in British public health records after the discovery of anesthesia to explain almost weekly chloroform anesthesia deaths; however, this diagnosis was self-serving, as by diagnosing a disease as cause of death (as opposed to anesthesia overdose), coroners were able to avoid inquiries. The diagnosis soon became popular for other unexplained causes of death (6). During World War I, German pathologists were told that performing autopsies on dead German soldiers was a “once in a lifetime opportunity” to collect organs for constitutional pathology research (13). One study, published in 1921, concluded that dead soldiers with too many lymphocytes in their thymus:

… represent an inferior human race … (who) often succumb to the hazards of daily life whereas the majority of people withstand them without a problem” and that their deaths could be attributed to “the inappropriate reaction of a mentally and physically inferior person to a momentary hazard” (15). Scarily, “it was a slippery slope in the inter-war years from the 'science' of constitutional pathology to Arian racial superiority, eugenics, and the rise of Nazism in post war Germany (15).

Therefore, using constitutional abnormalities involving the thymus to explain sudden infant death was simply part of a much bigger trend and was, simultaneously, a simple solution that avoided inquiries and absolved mothers of guilt. Unfortunately, beliefs that thymic pathology could precipitate sudden death in infants and children, especially when undergoing anesthesia, resulted in numerous children with radiographically enlarged “thymic shadows” being treated in the early 20th Century by x-irradiation, resulting in a spike in the incidence of thyroid cancer in young people a few decades later (6).

The diagnosis of status thymicolymphaticus should have been dead and buried in the 1920s. Its use had become so prevalent that the Medical Research Council and the Pathological Society of Great Britain and Ireland set up a joint committee of investigation in 1926; in a preliminary report they stated, “there is no evidence to show that there is any connection between the presence of a large glandular thymus and death from unexpected or trivial causes” (6). Their final report concluded the same when published in 1931 (16). Similarly, a lengthy and scholarly analysis published in 1926 by Major Greenwood and HM Woods concluded with this caustic analysis:

In cases of sudden death, the old inquest verdict of “died by the visitation of God” is at least as scientific and more modest that “Status [Thymicus”] or Lymphaticus”; “Cause unknown” is to be preferred … in certification and in evidence in coroners' courts … (it is) a good example of the growth of medical mythology. A nucleus of truth is buried beneath a pile of intellectual rubbish, conjecture, base observations and rash generalisation. This heap of rubbish is described in the current scientific jargon and treated as an orthodox shrine (17).

However, the diagnosis, while moribund, did not die for several more decades.

Tangentially, while on the topic of the thymus, it should be noted that petechial hemorrhages on the surface of the thymus and pleural surfaces at autopsy after sudden infant death were described as early as 1834 by Samuel W. Fern, who also astutely concluded that these deaths may be due to poorly understood natural causes rather than overlaying (18). Auguste Ambroise Tardieu, in an 1870 monograph on hanging, concluded that these small hemorrhages (later called “Tardieu spots”) were specific to suffocation and he published a second monograph that same year claiming thymic petechiae were indicative of infanticide by smothering (9). The presence of petechial hemorrhages has continued to be a prominent and consistent finding in SIDS autopsies (and has continued to fascinate pathologists) since the time of Fern. Beckwith, when describing his findings in “500 consecutive personally studied cases” of SIDS, provided a detailed discussion of the presence of intrathoracic petechiae in 87% of his cases and made special mention that the cervical lobes of the thymus, which are extrathoracic, are often spared (19). Beckwith suggested this “may indicate that intrathoriacic negative pressure was elevated sufficiently to cause capillary rupture during the agonal period” (19).

Early 20th Century Pathological Studies Suggesting Natural Cause

In the late first half of the 20th Century, some pathologists grew tired of diagnosing status thymicolymphaticus, accidental mechanical suffocation due to bedclothes, or inhalation of vomit (even though most likely suspected this to be simply an agonal event).

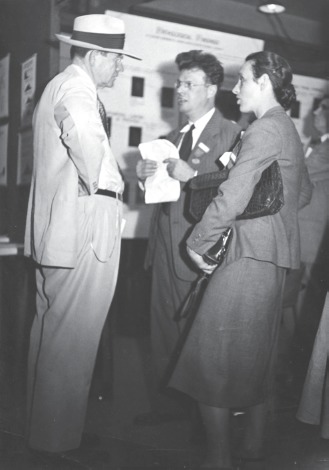

In the 1940s, husband and wife pathologists Jacob Werne, Office of the Chief Medical Examiner of the City of New York, and Irene Garrow, St. John's Long Island City and Flushing Hospitals (Image 1), and Birmingham UK pathologist W.H. Davidson began to publish work suggesting natural causes of death in many of these cases. The first of these publications was an abstract published in the American Journal of Pathology in 1942 and was authored by Werne only in which he described the occurrence of pulmonary lesions in a group of 50 infants who died unexpectedly and underwent routine medicolegal autopsies over a ten-year period in the Borough of Queens; in 28 cases, bacteriological studies were possible, but Werne concluded that:

Image 1.

Drs. Jacob Werne (center), Office of the Chief Medical Examiner of the City of New York, and Irene Garrow (right) networking in front of their poster at a medical meeting in the 1940s. Photograph provided by Dr. Joellen Werne.

The histological findings were sufficiently uniform in all to warrant the inclusion of the remaining 22 cases … The majority of sections of lung showed the occurrence of bronchitis, peri-bronchitis and peribronchial pneumonitis; mononuclear cells predominating. Extreme capillary congestion, pericapillary and intra-al-veolar edema, and edema and cellular infiltration of subpleural and larger septal tissues were frequently found. … Taken in conjunction with post-mortem bacteriological findings, the presence of the lesions described … supports the conclusion that acute infection was the cause of death in these cases (20).

Werne's presentation was extensively discussed (two pages of text) and one discussant said: “I am glad to hear Dr. Werne's paper. I think if more studies like this were made we would seldom be called upon to make the diagnosis of status lymphaticus” (20).

In 1945, Davidson published a paper entitled “Accidental suffocation” in the British Medical Journal suggesting that many cases of sudden unexpected infant death originally suspected to be due to suffocation could, with detailed autopsies, be determined to have natural causes, such as bronchopneumonia or tracheobronchitis (21).

Four other important papers were published by Werne and Garrow. The first, in 1947, described epidemiological and autopsy findings from 167 consecutive infants under one year of age who died unexpectedly while asleep over a 15-year period. The authors noted that they belonged “to the group which was ordinarily certified as dead of accidental mechanical suffocation” (22). In 25.7%, the autopsy found a readily apparent natural cause of death (e.g., mastoiditis with otitis media, bronchopneumonia, congenital heart disease, meningitis); in the other 74.3%, microscopic examination showed inflammation of the respiratory tract as described above. In many instances, there was a recent history of an upper respiratory tract infection in the infant or close contact. It was noted that deaths rarely occurred in the first month or after the first year, and that the majority were in the first six months, with a peak incidence in the third and fourth months. They noted that:

The low incidence during the first month of life is paradoxical if one accepts mechanical suffocation as an explanation for these sudden deaths. It is precisely during this period, when the infant is weakest, that a maximum number of such deaths would be expected (22).

They also noted a peak incidence in the winter months.

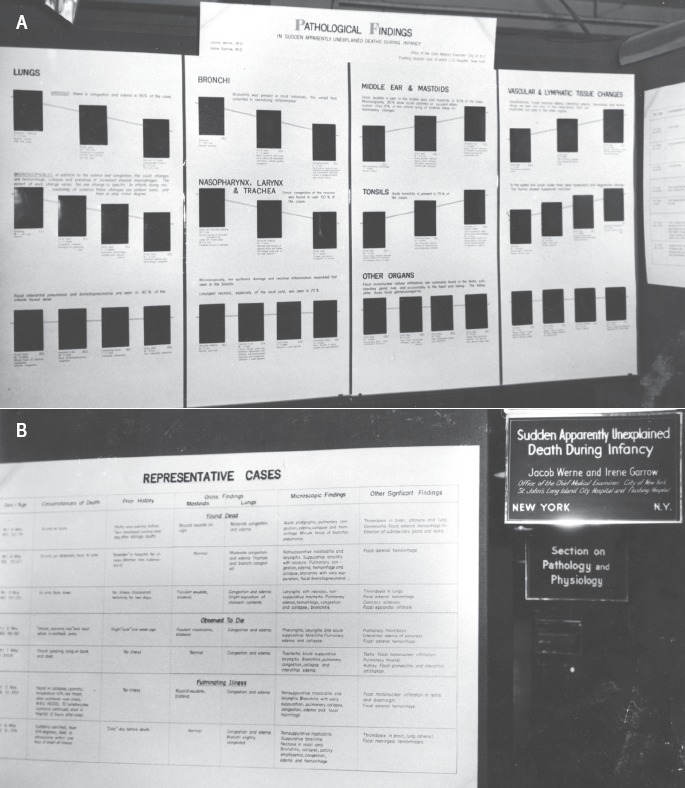

The other three important papers were published as a series entitled “Sudden apparently unexplained deaths during infancy” in the American Journal of Pathology in 1953 (23–25). The first was subtitled “I. Pathological findings in infants found dead” and it outlined the findings in 31 unselected cases from Queens in 1950. It was illustrated with two gross photographs of lungs and 48 photomicrographs. These findings were then compared and contrasted with those of the other two papers, which were subtitled “II. Pathologic findings in infants observed to die suddenly” (illustrated with 11 photomicrographs) and “III. Pathological findings in infants dying immediately after violence, contrasted with those after sudden apparently unexplained deaths” (illustrated with 21 photomicrographs); the latter two papers essentially served as age-matched controls for the first. Together, Werne and Garrow laid out the pathological findings that would soon be named “SIDS.” By the time these papers had been published, their series of sudden unexpected deaths in sleeping infants had reached 299 and those which could not be explained by other findings after autopsy represented 83.2% of the deaths. In addition to these seminal publications, Werne and Garrow promoted knowledge translation at regional and national meetings in the 1940s and first half of the 1950s (Image 2), including the 5th conference of the American Academy of Forensic Sciences in Chicago in February of 1953 (26, 27).

Images 2A and 2B.

Posters outlining the pathology of “SIDS” in the 1940s. The venue is likely the American Medical Association Meeting's Section of Pathology and Physiology. Photograph provided by Dr. Joellen Werne.

All three papers indicated support by a grant from the United States Public Health Service, but this funding came after most of the work was completed. While similar grants were funded for the medicolegal agencies in Cleveland, Baltimore, and Boston (see below), the Boston and Baltimore investigators did not publish anything. Lester Adelson (Image 3) and Eleanor Roberts Kinney of Cleveland published an important and highly cited paper both confirming the pathological findings of Werne and Garrow and providing more epidemiologic data in 1956 (28). This study spun off a Cleveland-based SIDS virology study (29) whose senior author was Frederick C. Robbins, a recent Nobel Laureate (for developing methodologies to culture viruses); this latter study just edged out Adelson and Kinney's paper to be the most highly cited “SIDS” paper during the years 1965-69 (30).

Image 3.

Dr. Lester Adelson. Credit: Dr. Tom Gilson, Cuyahoga County Medical Examiner's Office.

Acquisition of the Name “SIDS,” Research in the 1960s-1980s, and Prolonged Apnea Theory

The name SIDS was first proposed at the Second International Conference on the Causes of Sudden Death in Infancy in Seattle in 1969. It was defined by J. Bruce Beckwith (Image 4) as:

Image 4.

J. Bruce Beckwith, pediatric pathologist. Credit: Dr. Ona Faye-Peterson.

The sudden death of any infant or young child, which is unexpected by history, and in which a thorough post-mortem examination fails to demonstrate an adequate cause of death (31).

This term was in contrast to the earlier British term, “cot death,” coined in 1954 by Cambridge University pathologist Arthur Max Barrett, which was a more encompassing term as an autopsy was not required to fulfill its definition (5).

According to a history of SIDS by Edwin Mitchell and Henry Krous, the first important case control study, comparing 148 SIDS cases with 148 age-matched controls, was completed in Northern Ireland and published in 1971. It described the classic risk factors that were quickly confirmed by Beckwith's larger series (32).

There were many early theories as to the etiology of SIDS. Particularly popular were hypogammaglobulinemia, viscerovisceral reflex, hypersensitivity to cow's milk protein, and viral infections. Proponents of the hypogammaglobulinemia theory believed that the peak occurrence of SIDS at three to four months of age coincided with the natural attrition of maternally transferred antibodies. Marie A. Valdez-Dapena (Image 5), a pediatric pathologist at St. Christopher's Children's Hospital in Philadelphia who had recently begun studying cases of SIDS at the Medical Examiner's Office in Philadelphia, performed a classic study disproving this (33). She compared serum gammaglobulin levels from postmortem cardiac blood samples from SIDS victims with age-matched samples from healthy living patients and found that mean gammaglobulin levels were slightly higher in SIDS victims. For a more complete review of the rise and fall of early SIDS theories, please see the chapter by Beal (34) and Beckwith's seminal paper on SIDS (19).

Image 5.

Marie A. Valdez-Dapena, pediatric pathologist, photograph circa 1980. Credit: Society for Pediatric Pathology Archives Committee.

Within the new specialty of pediatric pathology, Beckwith and Valdez-Dapena became the two most important SIDS researchers (35, 36). Both generated new knowledge and wrote important review articles that were highly cited (19, 30, 37). Valdez-Dapena was also the lead author of an Armed Forces Institute of Pathology fascicle devoted to the pathology and epidemiology of SIDS in 1993 (38).

A cataclysmic paper was published in the October 1972 issue of Pediatrics by Alfred Steinschneider, an Assistant Professor of Pediatrics at Upstate Medical Center in Syracuse; it suggested that prolonged sleep apnea might be the cause of SIDS (39). The central theme was that Waneta E. Hoyt had lost five babies to SIDS between 1965 and 1971, and his paper focused on the last two deaths. Steinschneider, who had monitored both Molly and Noah Hoyt and documented bouts of sleep apnea while in the hospital, suggested prolonged sleep apnea was responsible when both infants subsequently died shortly after discharge. Steinschneider's paper seemed to prove that sleep apnea-related SIDS could run in families. This study precipitated the concept that infants with identifiable periods of sleep apnea were “near miss SIDS” cases and caused a fad of setting up home sleep monitors for infants in families who had already experienced a previous SIDS death. Steinschneider's paper was, by far, the most cited American SIDS paper in the 1970s (30). However, one year later, Richard L. Naeye, Chair of Pathology at Penn State, published a paper entitled “Pulmonary arterial abnormalities in the sudden infant death syndrome” in the New England Journal of Medicine (40), which became the second most cited in the 1970s. Naeye, based upon his belief that Steinschneider's paper was correct, reasoned that multiple episodes of apnea-based hypoxia must leave pathological evidence. Therefore, he compared lung histology of SIDS victims and infants raised at high altitude who had been killed in accidents and found that both showed evidence of chronic hypoxia (i.e., hypertrophy of small pulmonary arteries). Taken together, these two papers provided strong support for the apnea hypothesis throughout the 1970s and early 1980s (30).

However, a New York public prosecutor heard of Steinschneider's paper 14 years later while investigating a different case, was suspicious, reopened the Hoyt case, and, after an extensive investigation and obtaining a confession from the mother, eventually brought murder charges against her (41, 42). Neither the credibility of Steinschneider's paper nor Hoyt's later claim of innocence survived the trial. During the trial, it was noted that the sleep apnea monitors in this study had been set to go off if breathing ceased for 15 seconds, but expert witnesses testified that apneic periods of less than 20 seconds are not uncommon in babies who do not experience SIDS. During the trial, it came out that one of Hoyt's other children had actually died at almost 28 months of age, which was clearly outside of the range for SIDS. Steinschneider's paper was discredited 22 years after its publication when Hoyt was convicted of murdering her five babies (41–43). This was followed by a best-selling book, The Death of Innocents: A True Story of Murder, Medicine, and High-Stake Science (44). In the wake of the Hoyt case, Marie Noe, a woman who had previously been viewed with great sympathy for losing eight infants in Philadelphia between 1949 and 1968, was tried and convicted in 1999 of eight counts of second degree murder (45). It is now well known that apnea is common in the newborn infants and studies using home sleep apnea monitors have not altered SIDS rates. Most experts no longer believe that prolonged sleep apnea causes SIDS (46); however, other more subtle cardiorespiratory events are likely involved.

Two other controversial figures were involved in investigating purported cases of familial SIDS and are worth mentioning. Sir Samuel Roy Meadows, a retired British pediatrician who described Munchausen Syndrome by Proxy earlier in his career, was involved in providing expert testimony for the prosecution in several controversial cases in the UK and was accused of using faulty statistics. However, the idea of “Meadow's Law” (i.e., “one sudden infant death is a tragedy, two is suspicious and three is murder, until proven otherwise”) stuck (47). David Southall, who led an important study suggesting the sleep apnea was not a cause of SIDS and that sleep apnea monitors were not protective (48), later had ethics charges brought against him for covert video surveillance of parents interacting with their hospitalized children. Four of these sets of parents, who were unknowingly part of Southall's study, had previously lost one or more infants with a diagnosis of SIDS. Southall's covert videotapes showed parents intentionally suffocating their hospitalized children, creating ethical dilemmas weighing privacy rights of allegedly abusive parents versus children's rights to safety (49).

The sleep apnea hypothesis led to productive brainstem research, which is still ongoing (50). Brainstem abnormalities, both morphological and functional, have been implicated since Richard L. Naeye reported subtle brainstem astrogliosis in 1976; neuropathologists have substantiated his findings. The importance of Naeye's observations was that they suggested an initial chronic insult facilitating SIDS prior to the acute event, the actual infant demise. Neuropathological research in this arena has continued productively for four decades and recent studies suggest abnormal serotonin (5-HT) receptor binding in the medulla oblongata (50).

“Back to Sleep” in the Late 1980s and Early 1990s

For at least 100 years, there had been speculations that SIDS might be related to sleeping position. While not fully protective, by the late 1980s and early 1990s, there was considerable evidence that campaigns to lay infants on their back or side (i.e., to avoid prone sleeping positions), to avoid infant exposure to cigarette smoke, to prevent infants from overheating, and to contact a doctor if infants seem unwell were markedly decreasing the incidence of SIDS. Possibly the most important study documenting these modifiable risk factors, and a few others, was the New Zealand Cot Death Study which commenced in November 1987, followed by the New Zealand Cot Death Prevention Programme in February 1991 (51). Back to Sleep campaigns were so transformative that they altered risk factors for SIDS (52).

Triple Risk Model

Taken together, the brainstem research findings and the Back to Sleep research findings suggested a new over-arching SIDS theory, the Triple Risk Model (53), which is currently favored by many SIDS researchers. According to Kinney:

SIDS occurs when three factors simultaneously impinge upon the infant: (1) an underlying vulnerability in the infant; (2) a critical developmental period, that is, the first 6 months of life when 90% of SIDS occur; and (3) an exogenous stressor, for example, prone sleep position with rebreathing exhaled gases leading to hypoxia and/or hypercapnia (50).

Vagaries of Funding for SIDS Research

One approach to medical research historiography is to study research funding patterns. The initial research by Werne and Garrow, which essentially outlined the pathological features of “SIDS,” was unfunded and the authors recommended in 1947 that the American Public Health Association establish an interdisciplinary committee to study this entity. This idea was reinforced a year later when the father of a “SIDS” victim in Los Angeles, who wanted immediate answers to his questions, hired a private research firm to study the frequency of “SIDS” in Los Angeles. This resulted in an anonymous account entitled “Death in the Bassinet,” published in the Women's Home Companion in February 1948 (54); this article precipitated a large influx of letters to the Public Health Service. As a result, the National Institute of Health (NIH) funded a conference in Washington, DC in November 1949; it was chaired by famous Harvard pediatric pathologist Sidney Farber, who had published a pertinent paper in 1932 (55). Five other pathologists (including Werne), two pediatricians, an epidemiologist, and five NIH officials attended and uniformly accepted Werne and Garrow's evidence supporting an infectious or inflammatory respiratory etiology rather than accidental smothering. The outcome was to conduct parallel studies funded by the Public Health Service. It was decided to fund Werne and Garrow in New York, and three young Harvard-trained forensic pathologists (Richard Ford, a Medical Examiner in Boston; Russell S. Fischer, Maryland's Chief Medical Examiner; Lester Adelson, a deputy coroner in Cleveland).

While Werne and Garrow did publish their prior research (23–25), their research program stopped abruptly in 1953 when city officials and the press charged Werne with neglecting his medical examiner duties. In the early 1950s, many New York City Medical Examiner cases were performed in designated hospitals and many of the Assistant Medical Examiners were family doctors; therefore, out of necessity, many of the autopsies were actually performed by hospital pathologists or pathology residents, but were then signed off by the Assistant Medical Examiner. Werne, a board-certified pathologist, also operated in this manner for nonsuspicious cases. In 1953, a vindictive family investigated Werne after his testimony did not support a lawsuit they had filed related to the death of their son. They eventually found two reports showing that Werne had performed autopsies at two different hospitals at exactly the same time and then reported this seemingly impossible accomplishment to the press, resulting in a media frenzy suggesting fraud within the Medical Examiner's Office. This was further fueled when it was revealed that Werne was also harvesting corneas for the eye bank. Even though he had family consent, alarming headlines such as “Doctor Steals Eyes from Corpses!” appeared in local papers (56). Werne, after 22 years of service, took a leave of absence from the Medical Examiner's Office and served as a Lieutenant Colonel at the Army Chemical Center in Maryland from October 1953 until March 15, 1955. While serving in the military, a Queens County Grand Jury was convened resulting in a critical presentment on March 18, 1954. Shortly after leaving the military, having returned to New York and suffering from depression, Werne took his own life on April 14, 1955. Tragically, Werne was cleared by New York State Attorney General, Jacob Javits, shortly after his death (56–59).

Of the others grantees, only Adelson was able to generate useable data. His 1956 paper, published with microbiologist Elenor Kinney, confirmed and expanded Werne and Garrow's findings and was one of the most highly cited papers in the field (30).

After the pathology papers of the 1950s funded by grants from the US Public Health Services, there was a hiatus of federal research funding and parents who had lost infants and become activists filled this gap. Formalized research funding to study SIDS can be traced back to the death of 6-month-old Mark Addison Roe of Greenwich, CT in October 1958 (60, 61). At autopsy, his cause of death was determined to be “acute bronchial pneumonia.” Mark's grandparents had taken out a life insurance policy on him at birth and his parents wanted to contribute the proceeds towards “SIDS” research, but they could not find either a research foundation or a researcher that was interested in studying this ill-defined entity. In 1962, they formed the Mark Addison Roe Foundation. One of the group's medical consultants was Marie Valdez-Dapena in Philadelphia. In 1967, the Roe Foundation moved to New York City and changed its name to the National Foundation for Sudden Infant Death (in 1976, it became the National SIDS Foundation [NSIDSF]) (60, 61). In Washington State, Fred and Mary Dore lost their 3-month-old daughter Christine in September 1961 (60, 61). Fred was a state senator and Mary a natural activist. Once learning of the magnitude of the problem in Seattle, they started a parents' support group and began politicking behind the scenes. In 1963, Senator Dore introduced Senate Bill 180, appropriated $20 000 to perform autopsies at the University of Washington Medical School on infants dying suddenly and unexpectedly. The autopsies were done at the Children's Orthopedic Hospital and Medical Center in Seattle. The research team included pediatric pathologist J. Bruce Beckwith and pediatrician/epidemiologist Abraham B. Bergman. The Dore's also converted Pediatrics Chair Robert Aldrich to their cause, and then he was almost immediately recruited by President John F. Kennedy to become the first director of his new National Institute of Child Health and Development (NICHD). Aldrich awarded a contract to the University of Washington to host the First International Conference on the Causes of Sudden Death in Infancy in the fall of 1963 (61). According to Eileen G. Hasselmeyer (the Director of the NICHD Perinatal Biology and Infant Mortality Program who was put in charge of expanding research in this area):

It was expected that the exchange of ideas during this conference would encourage research grant applications from the scientific community, but this did not occur. By 1969, NICHD was supporting only two projects that had SIDS as a primary focus (62).

It was Beckwith and Bergman who received the first ever federal research grant for SIDS research from NICHD in 1965 ($144 000 over three years). To try to generate more interest, NICHD sponsored a second research conference in Seattle in 1969. While it was at this conference that SIDS was proposed as the preferred diagnostic term, less was accomplished than hoped. Once again, according to Hasselmeyer:

The response was minimal. During fiscal years 1964-1971, thirteen research grants applications were submitted. Four were recommended for approval and funded; one of these was the 1969 conference (62).

The need for brevity precludes a more detailed analysis of the substantial activism across the United States involved in pushing the federal government to fund related research; however, this is well-described in Bergman's The “Discovery” of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. Briefly:

In 1971 the NSIDSF forged a “battle plan” which took the form of a directed campaign at national, state, and local community levels. The twin goals were promoting research and assisting families. It quickly became apparent that the foundation (i.e., NSIDSF) itself could never acquire sufficient funds to sponsor a substantial research program. Instead, efforts were directed through political process toward securing appropriations for the … NICHD. As a result of these efforts, in 1973 Congress appropriated $4 million for SIDS research. … The Foundation's own research funds were used to provide “seed money ” and to attract young investigators to the field of SIDS through student research fellowships (61).

This seems to have been effective as there was a steep increase in the number of SIDS research projects supported by NICHD immediately after this, which peaked at 41 in 1977. Numbers of grants funded dropped again in the early 1980s, but this may have reflected other Institutes supporting research relevant to SIDS (62). Bergman's The Discovery of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome also describes fascinating details of the politics behind passing and implementing the SIDS Act of 1974 (61).

The United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and several European countries also formed organizations similar to NSIDSF (5).

Whittling Away at SIDS

As noted above, the Back to Sleep program and, to a lesser extent, educating parents about the effects of smoking and other risk factors greatly decreased the incidence of deaths from SIDS. Improved death scene investigations also accomplished the same, as some unexpected infant deaths could plausibly be explained by asphyxiation and hence were no longer classified as SIDS. However, it should be noted that there is considerable subjectivity in death scene interpretation and there is not a high degree of concordance amongst pathologists when attempting to ascertain whether death scenes contributed to or caused deaths (52). “Diagnostic shift” issues related to how medical examiners choose to sign out cases where there may be less than bulletproof evidence of asphyxia not only make it difficult to compare SIDS rates between geographic locations, but changing overall trends make it difficult to compare SIDS rates over time (63). However, most experts believe the incidence of SIDS has decreased by more than 50% since the late 1980s (64).

“Molecular autopsies” (i.e., ancillary testing after a complete autopsy) have also had an effect. Starting in the late 1980s, it became clear that rare fatty acid oxidation defects, especially medium chain acyl Co-A dehydrogenase (MCAD) deficiency, could present as SIDS (65, 66). Since this was a heritable defect, it became important to identify not only for correct death certification, but also to allow parental family planning. Likewise, in the 1990s, the same became true for ion channelopathies like long QT syndrome (LQTS); in fact, it is now believed that the frequency of these, because of the increasing number of mutations associated with LQTS, could be as high as 10% in cases originally presenting as possible SIDS (67). Since both are specific diagnoses, neither qualifies as SIDS, highlighting the importance of molecular autopsies (66).

What's in a Name?

As previously noted, the name SIDS was first proposed at the Second International Conference on the Causes of Sudden Death in Infancy in Seattle in 1969. Ten years later, the World Health Organization's International Classification of Diseases recognized SIDS with its own code, ICD 798-0. In 1991, an NICHD expert panel revised the definition by restricting cases to less than one year of age and required the inclusion of a death scene examination. There was one other redefinition of SIDS in 2004 that has sometimes been called the “San Diego definition”, which incorporated “with onset of the fatal episode apparently occurring during sleep” and a greater emphasis on evaluating the circumstances of death (32).

Nevertheless, death certifiers have always found the term SIDS somewhat controversial and purists, especially in recent decades, have often preferred other terms such as sudden unexpected death in infancy (SUDI), sudden unexpected infant death (SUID), unclassified sudden infant death (USID), or undetermined. The major problem is that not only are there no pathognomonic findings in SIDS, even the findings suggestive of the diagnosis are very soft, and it has always been a diagnosis of exclusion, which is at best imprecise.

The name SIDS was favored by most for almost 40 years, but the National Association of Medical Examiners (NAME) issued the following advice related to sudden unexpected death in infancy in 2007: “the 'undetermined' classification is recommended to acknowledge that the true nature of the death is not known” (68). According to Ernest Cutz, a pediatric pathologist in Toronto,

The term SIDS served 3 main purposes: to encourage and focus research into these tragic deaths, to comfort parents with knowledge that the death was the result of a natural disease entity, and to absolve parents or caregivers of any blame for the death of their infant (68).

Throughout the period that the term SIDS was commonly used, it was recognized that the term had some disadvantages as well; in particular, it was too easy to think of SIDS as a single disease entity, whereas, in reality, the syndrome's similar clinical, epidemiological, and pathological patterns likely had multiple causes. Furthermore, its registration around the world was inconsistent, making international comparisons difficult.

Kutz notes that:

During the last decade the use of SIDS as a diagnosis has fallen out of favor. In many jurisdictions, the use of this term has been reduced considerably or abandoned altogether (68).

He suggests three reasons for this: changing forensic pathology philosophies, emphasis on prevention by public health agencies and the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the disappearance of SIDS advocacy groups. Some have fought this trend and plead for the continued use of SIDS; for instance, Henry F. Krous, a pediatric pathologist who devoted his stellar almost 40 year long career to SIDS research, has made cogent arguments in the context of the uncertainty of death scene interpretations and has noted that a diagnosis of SIDS “does not require precise quantification of any of the important triple risk elements” (69). Opponents of the term SIDS have argued that the third factor in the triple risk model is problematic, suggesting if position results in rebreathing of exhaled gases and leads to asphyxia as the cause of death, then the manner of death is accidental rather than natural. Since SIDS is supposed to be natural, this nuance actually precludes a diagnosis of SIDS.

Conclusion

As a medical historian, the natural history of disease is a fascinating topic. As outlined above, status thymicolymphaticus was a common diagnosis in the early 1900s and had entirely disappeared before the end of the century; however, the science underlying the concept of SIDS is substantial, making any decision on its fate as a diagnostic entity both difficult and controversial. Medical historian and sociologist Charles E. Rosenberg maintains “that in our culture, a disease does not exist as a social phenomenon until we agree that it does – until it is named' (70). While medical scientists who focus solely on the biological basis of disease, and especially diseases where the etiology and pathogenesis are clear, might strongly disagree, perhaps Rosenberg's concept holds better for syndromes like SIDS where the etiology is unknown or, more likely, where multiple etiologies can converge with the same symptomatology. Rosenberg's disease framework allows named diseases to disappear. For instance, homosexuality was once considered a psychiatric disease and now it is not. Sudden infant death syndrome has existed as a named entity since 1969; its history suggests it has served as a useful, and also highly political, social phenomenon that has been widely accepted by the public. Nevertheless, since the 1990s, the incidence of SIDS, which is a diagnosis of exclusion, has been shrinking. Because some of its precipitating causes have been identified and rectified, the actual number of deaths has sharply decreased. As more of these are found, it would shrink further and eventually, at least theoretically, there would be a time when there are no more cases of SIDS. The incidence has also further decreased, likely artificially, due to diagnostic shift. Now, because of the lack of single-mindedness amongst those certifying deaths, the same difficult case can be plausibly classified as explained, unexplained, or SIDS whereas a few decades ago, the diagnosis would likely have been SIDS. Obviously, there is a need to promote agreement in death certification; striking SIDS from the medical lexicon and education of death certifiers towards a single-minded approach for interpreting findings at death scenes could be one way to accomplish this. Future medical historians will evaluate this decision. Finally, the public will likely want some say as to whether SIDS continues to be a useful social phenomenon.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Dr. J. Bruce Beckwith for reading this manuscript and for helpful comments. I would also like to thank Kristin Rodgers, MLIS (Collections Curator), Medical Heritage Center, Ohio State University Health Sciences Library, for archival assistance; Charlotte Monroe and the Interlibrary Loan services of the University of Calgary for assistance with obtaining articles; and Dr. Joellen Werne for providing photographs of her parents and documents collected by her mother, Dr. Irene Garrow.

Footnotes

ETHICAL APPROVAL

As per Journal Policies, ethical approval was not required for this manuscript

STATEMENT OF HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

This article does not contain any studies conducted with animals or on living human subjects

STATEMENT OF INFORMED CONSENT

No identifiable personal data were presented in this manuscsript

DISCLOSURES & DECLARATION OF CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors, reviewers, editors, and publication staff do not report any relevant conflicts of interest

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE The authors have indicated that they do not have financial relationships to disclose that are relevant to this manuscript

References

- 1).Savitt T.L. The social and medical history of crib death. J Fla Med Assoc. 1979. Aug; 66(8): 853–9. PMID: 392045. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2).Russell-Jones D.L. Sudden infant death in history and literature. Arch Dis Child. 1985. Mar; 60(3): 278–81. PMID: 3885870. PMCID: PMC 1777210. 10.1136/adc.60.3.278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3).Savitt T.L. Smothering and overlaying of Virginia slave children: a suggested explanation. Bull Hist Med. 1975. Fall; 49(3): 400–4. PMID: 1182320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4).Norvenius S.G. Some medico-historic remarks on SIDS. Acta Paediatr Suppl. 1993. Jun; 82 Suppl 389: 3–9. PMID: 8374187. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1993.tb12863.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5).Limerick S.R. Sudden infant death in historical perspective. J Clin Pathol. 1992. Nov; 45(11 Suppl): 3–6. PMID: 1474156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6).Dally A. Status lymphaticus: sudden death in children from “visitation of God” to cot death. Med Hist. 1997. Jan; 41(1): 70–85. PMID: 9060205. PMCID: PMC1043871. 10.1017/s0025727300062049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7).Templeman C. Two hundred and fifty-eight cases of suffocation of infants. Edinburgh Med J. 1892; 38: 322–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8).Guntheroth W.G., Spiers P.S. Are bedding and rebreathing suffocation a cause of SIDS? Pediatr Pulmonol. 1996. Dec; 22(6): 335–341. PMID: 9016466. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9).Guntheroth W.G. The thymus, suffocation, and sudden infant death syndrome–social agenda or hubris? Perspect Biol Med. 1993. Autumn; 37(1): 2–13. PMID: 8265334. 10.1353/pbm.1994.0062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10).Lee C.A. On the thymus gland: its morbid affections, and the diseases which arise from its abnormal enlargement. Am J Med Sci. 1842; 3: 135–154. 10.1097/00000441-184201000-00012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11).Friedleben A. Die physiologie der thymusdrüse in gesundheit und krankheit. Frankfurt: Literarische Anstalt; 1858. 336 p. [Google Scholar]

- 12).Paltauf A. Uber die Beziehungen der Thymus zum plotzichem Tod. Wien Klin Wocheneschr. 1889; 2: 877–81 and 1890; 3: 172-5. Cited by: Guntheroth WG. The thymus, suffocation, and sudden infant death syndrome–social agenda or hubris? Perspect Biol Med. 1993 Autumn; 37(1): 2-13. PMID: 8265334. 10.1353/pbm.1994.0062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13).Prüll C.R. Pathology at war 1914-1918: Germany and Britain in comparison. Clio Med. 1999; 55: 131–161. 10.1163/9789004333277_006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14).Prüll C.R. Greater than the parts: holism in biomedicine, 1920-1950. New York: Oxford University Press; c1998. Chapter 3, Holism and German pathology (1914-1933); p. 46–67. [Google Scholar]

- 15).Wright J.R. Jr., Baskin L.B. Pathology and laboratory medical support for the American Expeditionary Forces by the US Army Medical Corps during World War I. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2015. Sep; 139(9): 1161–72. PMID: 26317455. 10.5858/arpa.2014-0528-HP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16).Young M., Turnbull H.M. An analysis of the data collected by the status lymphaticus investigation committee. J Path Bact. 1931; 34(2): 213–58. 10.1002/path.1700340211. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17).Greenwood M., Woods H.M. “Status thy mo-lymphaticus” considered in the light of recent work on the thymus. J Hyg. 1927; 26(3): 305–26. 10.1017/s0022172400009165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18).Fern S.W. Sudden and unexplained death in children. Lancet. 1834. Nov 8; 23(584): 246 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)96501-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19).Beckwith J.B. The sudden infant death syndrome. Curr Probl Pediatr. 1973. Jun; 3(8): 1–36. PMID: 4351768. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20).Werne J. Postmortem evidence of acute infection in unexpected death in infancy. Am J Pathol. 1942. Jul; 18(4): 759–61. [Google Scholar]

- 21).Davison W.H. Accidental infant suffocation. Br Med J. 1945. Aug 25; 2(4416): 251–2. PMID: 20786242. PMCID: PMC2059644. 10.1136/bmj.2.4416.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22).Werne J., Garrow I. Sudden deaths of infants allegedly due to mechanical suffocation. Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1947. Jun; 37(6): 675–87. PMID: 20242032. 10.2105/ajph.37.6.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23).Werne J., Garrow I. Sudden apparently unexplained death during infancy. I. Pathologic findings in infants found dead. Am J Pathol. 1953. Jul-Aug; 29(4): 633–75. PMID: 13065413. PMCID: PMC1937460. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24).Werne J., Garrow I. Sudden apparently unexplained death during infancy. II. Pathologic findings in infants observed to die suddenly. Am J Pathol. 1953. Sep-Oct; 29(5): 817–31. PMID: 13092220. PMCID: PMC1937467. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25).Garrow I., Werne J. Sudden apparently unexplained death during infancy. III. Pathologic findings in infants dying immediately after violence, contrasted with those after sudden apparently unexplained death. Am J Pathol. 1953. Sep-Oct; 29(5): 833–51. PMID: 13092221 PMCID: PMC1937464. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26).Disputes theory of suffocation in baby deaths. Chicago Tribune. 1953. Feb 28, 1953: Part 1: 16 (col. 3). [Google Scholar]

- 27).Werne J., Garrow I. Stillbirths and neonatal deaths as seen by the medical examiner. N Y State J Med. 1952. Feb 15; 52(4): 475–6. PMID: 14899708. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28).Adelson L., Kinney E.R. Sudden and unexpected death in infancy and childhood. Pediatrics. 1956. May; 17(5): 663–99. PMID: 13322513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29).Gold E., Carver D.H., Heineberg H. et al. Viral infection: a possible cause of sudden, unexpected death in infants. N Engl J Med. 1961. Jan 12; 264: 53–60. PMID: 13706404. 10.1056/NEJM196101122640201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30).Hufbauer K. Federal funding and sudden infant death research, 1945-80. Soc Stud Sci. 1986. Feb; 16(1): 61–78. PMID: 11611909. 10.1177/030631286016001004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31).Beckwith J.B. Discussion of terminology and definition of sudden infant death syndrome. In: Bergman A.B., Beckwith J.B., Ray C.G. eds. Sudden infant death syndrome: proceedings of the second international conference on causes of sudden death in infants. Seattle: University of Washington Press; 1970. p. 14–22. [Google Scholar]

- 32).Mitchell E.A., Krous H.F. Sudden unexpected death in infancy: a historical perspective. J Paediatr Child Health. 2015. Jan; 51(1): 108–12. PMID: 25586853. 10.1111/jpc.12818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33).Valdés-Dapena M.A., Eichman M.F., Ziskin L. Sudden and unexpected death in infants. I. Gamma globulin levels in the serum. J Pediatr. 1963. Aug; 63: 290–4. PMID: 14043071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34).Beal S.M. The rise and fall of several theories. In: Sudden infant death syndrome: problems, progress and possibilities. Byard R.W., Krous H.F., eds. London: Arnold; 2001. p. 236–42. [Google Scholar]

- 35).Haust M.D., Gilbert-Barness E.F. Founders of pediatric pathology: Marie Valdés-Dapena. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2014. May-Jun; 17(3): 165–8. PMID: 24735076. 10.2350/14-02-1442-PB.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36).Benjamin D.R. J. Bruce Beckwith: physician-scientist. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2005. May-Jun; 8(3): 282–6. PMID: 16010496. 10.1007/s10024-005-1153-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37).Valdés-Dapena M.A. Sudden unexpected death in infancy: A review of the world literature 1954-1966. Pediatrics. 1967. Jan; 39(1): 123–38. PMID: 5334046. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38).Valdés-Dapena M., McFeeley P.A., Hoffman H.J. et al. Histopathology atlas for the sudden infant death syndrome: findings derived from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development cooperative epidemiological study of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) risk factors. Washington: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 1993. 339 p. [Google Scholar]

- 39).Steinschneider A. Prolonged apnea and the sudden infant death syndrome: clinical and laboratory observations. Pediatrics. 1972. Oct; 50(4): 646–54. PMID: 4342142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40).Naeye R.L. Pulmonary arterial abnormalities in the sudden infant death syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1973. Nov 29; 289(22): 1167–70. PMID: 4585360. 10.1056/NEJM197311292892204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41).Pinholster G. SIDS paper triggers a murder charge. Science. 1994. Apr 8; 264(5156): 197–8. PMID: 8146647. 10.1126/science.8146647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42).Pinholster G. Multiple 'SIDS' case ruled murder. Science. 1995. Apr 28; 268(5210): 494 PMID: 7725090. 10.1126/science.7725090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43).Very important erratum? – 20 years later. Pediatrics. 1994. Jun; 93(6): 944. [Google Scholar]

- 44).Firstman R., Talan J. The death of innocents: a true story of murder, medicine, and high-stake science. New York: Random House; 2011. 640 p. [Google Scholar]

- 45).Glatt J. Cradle of death. New York: St. Martin's True Crime; 2000. 236 p. [Google Scholar]

- 46).Baird T.M. Clinical correlates, natural history and outcome of sleep apnea. Semin Neonatol. 2004. Jun; 9(3): 205–11. PMID: 15050213. 10.1016/j.siny.2003.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47).Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia [Internet]. San Francisco: Wikimedia Foundation; c2017. Roy Meadow; [cited 2017. Feb 9]. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roy_Meadow. [Google Scholar]

- 48).Identification of infants destined to die unexpectedly during infancy: evaluation of predictive importance of prolonged apnoea and disorders of cardiac rhythm or conduction. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1983. Apr 2; 286(6371): 1092–6. PMID: 6404340. PMCID: PMC1547468. 10.1136/bmj.286.6371.1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49).Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia [Internet]. San Francisco: Wikimedia Foundation; c2017. David Southall; [cited 2017. Feb 9]. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/David_Southall. [Google Scholar]

- 50).Kinney H.C. Brainstem mechanisms underlying the sudden infant death syndrome: evidence from human pathologic studies. Dev Psychobiol. 2009. Apr; 51(3): 223–33. PMID: 19235901. 10.1002/dev.20367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51).Mitchell E.A. SIDS: past, present and future. Acta Paediatr. 2009. Nov; 98(11): 1712–9. PMID: 19807704. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2009.01503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52).Trachtenberg F.L., Haas E.A., Kinney H.C. et al. Risk factor changes for sudden infant death syndrome after initiation of back-to-sleep campaign. Pediatrics. 2012. Apr; 129(4): 630–8. PMID: 22451703. PMCID: PMC3356149. 10.1542/peds.2011-1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53).Filano J.J., Kinney H.C. A perspective on neuropathologic findings in victims of SIDS: the triple risk model. Biol Neonate. 1994; 65(3-4): 194–7. PMID: 8038282. 10.1159/000244052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54).“Death in the Bassinet.” Women's Home Companion. 1948. Feb; 38: 113–5. [Google Scholar]

- 55).Farber S. Fulminating Streptococcus infections in infancy as a cause of sudden death. N Engl J Med. 1934. Jul 26; 211: 154–9. 10.1056/nejm193407262110403. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56).Garrow I. History of Jacob Werne (unpublished) consisting of correspondence, transcripts, newspaper clippings, etc; a copy of this file is in the author's possession, 71 pages; the author's medical history files will be preserved at the Medical Heritage Center, Ohio State University College of Medicine after his death.

- 57).City medical aide suicide in Queens. Jury had criticized Dr. Werne for “improper” practices in medical examiner's post. New York Times, 1955. Apr 15. p. 48. [Google Scholar]

- 58).Evans C. Blood on the table: the greatest cases of New York City's Office of the Chief Medical Examiner. NY: Penguin Press; 2008. p. 101–3. [Google Scholar]

- 59).Obituary: Jacob Werne 1905-1955. Am J Clin Pathol. 1955. Oct; 25(10): 1190 10.1093/ajcp/25.10.1190. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60).Bergman A.B. Twenty-fifth anniversary of the National Sudden Infant Death Syndrome Foundation. Pediatrics. 1988. Aug; 82(2): 272–4. PMID: 3399302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61).Bergman A.B. The “discovery” of sudden infant death syndrome: lessons in the practice of political medicine. Seattle: University of Washington Press; 1988. 237 p. [Google Scholar]

- 62).Hesselmeyer E.G., Hunter J.C. A historical perspective on SIDS research. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1988; 533: 1–5. PMID: 3048168. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1988.tb37228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63).Byard R.W. Changing infant death rates: diagnostic shift, success story, or both? Forensic Sci Med Pathol. 2013. Mar; 9(1): 1–2. PMID: 22664792. 10.1007/s12024-012-9350-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64).Kinney H.C., Thach B.T. The sudden infant death syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2009. Aug 20; 361(8): 795–805. PMID: 19692691. PMCID: PMC3268262. 10.1056/NEJMra0803836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65).Roe C.R., Millington D.S., Maltby D.A., Kinnebrew P. Recognition of medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency in asymptomatic siblings of children dying of sudden infant death or Reye-like syndromes. J Pediatr. 1986. Jan; 108(1): 13–8. PMID: 3944676. 10.1016/s0022-3476(86)80762-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66).Opdal S.H., Rognum T.O. The sudden infant death syndrome gene: does it exist? Pediatrics. 2004. Oct; 114(4): e506–12. PMID: 15466077. 10.1542/peds.2004-0683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67).Tester D.J., Ackerman M.J. Cardiomyopathic and channelopathic causes of sudden unexplained death on infants and children. Ann Rev Med. 2009; 60: 69–84. PMID: 18928334 10.1146/annurev.med.60.052907.103838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68).Cutz E. The disappearance of sudden infant death syndrome: has the clock turned back? JAMA Pediatr. 2016. Apr; 170(4): 315–6. PMID: 26833064. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.4172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69).Krous H.F. A commentary on changing infant death rates and a plea to use sudden infant death syndrome as a cause of death. Forensic Sci Med Pathol. 2013. Mar; 9(1): 91–3. PMID: 22715066. 10.1007/s12024-012-9354-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70).Rosenberg C.E. Forward. In: Framing disease: studies in cultural history. Rosenberg C.E., Golden J., eds. New Brunswick (NJ): Rutgers University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]