Abstract

When “common things are common,” the discovery of a subdural hemorrhage in an adult is most likely to be due to trauma. When the subdural hemorrhage is associated with an intraparenchymal hematoma, statistically speaking, the subdural hemorrhage is likely the result of a hypertensive hemorrhage that has ruptured into the subdural space or trauma that resulted from a collapse to the ground following hypertensive intra-axial bleeding. However, “common things” do not always explain the source of a subdural hemorrhage or intraparenchymal hematoma. In this case, an adult woman presented to the hospital obtunded and was diagnosed with a subdural hemorrhage (with mass effect) and intraparenchymal hematoma as the result of a ruptured dural arteriovenous fistula/malformation. This case highlights an unusual source of intracranial bleeding that resulted in death.

Keywords: Forensic pathology, Neuropathology, Dural arteriovenous fistula

Case Report

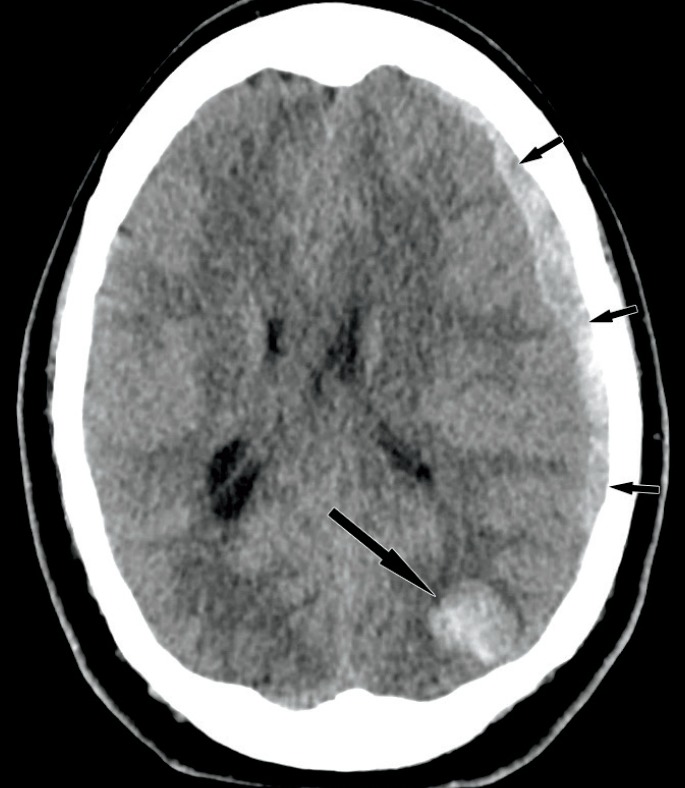

A 43-year-old woman presented with multiple tonic-clonic seizures in rapid succession preceded by visual auras. Her past medical history included developmental delay, seizures, idiopathic intracranial hypertension (with treatment via frequent lumbar punctures), and headaches. Her medical records also reference a vague history of craniofacial trauma. Emergency medical services transported her to the Emergency Department where she was intubated and given lorazepam. Computed tomography (CT) of the head (Image 1) on admission showed a left occipital intraparenchymal hemorrhage and a left hemispheric subdural hematoma with mass effect resulting in midline shift. Chronic findings from the idiopathic intracranial hypertension, such as an expanded, empty sella are not shown.

Image 1.

Noncontrast computed tomography of the head with left occipital intraparenchymal hematoma (long arrow) and left subdural hematoma (short arrows).

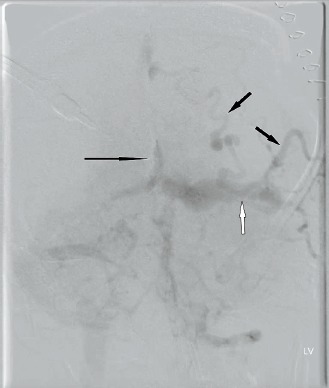

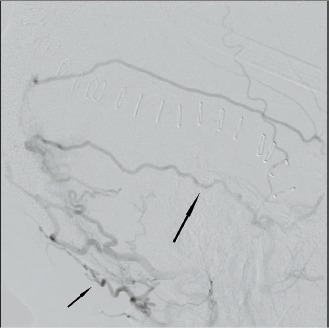

A maximum intensity projection (MIP) image from a CT angiogram (Image 2) showed a dural arteriovenous fistula (DAVF) with enlarged, dilated deep veins including the right basal vein of Rosenthal, vein of Galen, straight sinus, as well as torcula, left transverse sinus, and occipital sinus. Furthermore, smaller dilated veins simulated enlarged arteries in the distal, posterior left and right middle cerebral territories. A more craniad MIP image from the same CT angiogram (Image 3) demonstrated a focal aneurysmal outpouching as the likely source of the intraparenchymal occipital hemorrhage.

Image 2.

Dilated deep (short arrows) and superficial veins (long arrow) of the dural arteriovenous fistula from axial maximum intensity projection of the computed tomography angiogram.

Image 3.

Aneurysmal-appearing outpouching (arrow) at the site of intraparenchymal hemorrhage from an axial maximum intensity projection of the computed tomography angiogram.

The patient was emergently taken to the operating room (OR) for evacuation of the subdural hematoma. While in the OR, catheter angiography (Image 4) showed a Borden type II, Cognard type IIa+b dural arteriovenous fistula with drainage into the major venous sinuses, reflux into the cortical veins, and retrograde flow (not shown). The major blood supply was through the right occipital and right middle meningeal arteries (Image 5).

Image 4.

Frontal subtraction angiogram in the venous phase with dilated deep (long black arrow) and superficial veins (short black arrows) as well as the left tranverse sinus (white arrow) after left internal carotid injection.

Image 5.

Lateral subtraction angiogram from an external carotid injection with dilated occipital (short arrow) and meningeal (long arrow) arterial branches feeding the dural arteriovenous fistula.

That same day, she returned to the OR for liquid embolization of the DAVF and the following day she underwent a decompressive craniectomy for increased intracranial pressure and ruptured DAVF.

During her hospital course, she had numerous complications including persistently elevated intracranial pressure, deep venous thromboses, increase in size of the intraparenchymal hematoma, respiratory failure secondary to pneumonia and severe/progressive acute respiratory distress syndrome, neurogenic pulmonary edema, sepsis, ischemia of her extremities, and multiple infections. Despite maximal medical and surgical management, the woman died 27 days after her initial presentation to hospital as a result of the complications of the ruptured DAVF.

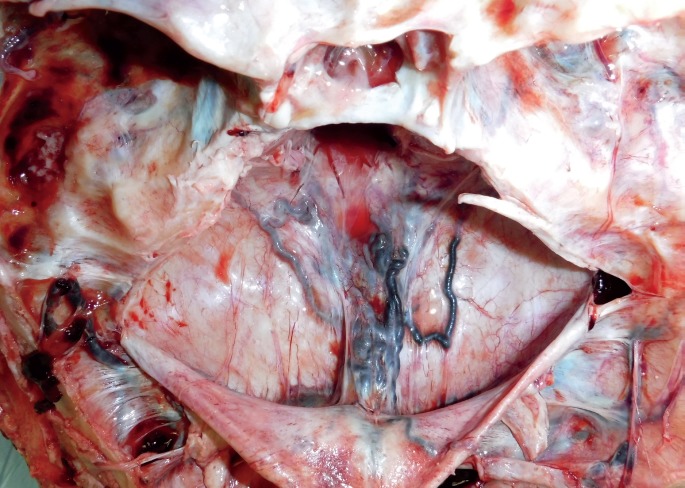

A consented autopsy was performed; examination of the scalp, skull, dura, and brain demonstrated the features of a partial left hemicraniectomy in a diffusely edematous and patchily ecchymotic scalp. The left cerebral hemisphere had subtotally herniated through the hemicraniectomy site (transcalvarial herniation).

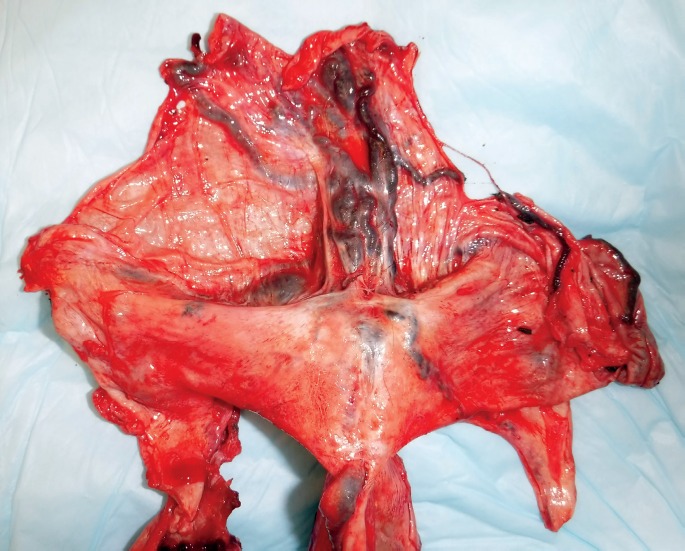

The dural venous vasculature immediately draining into the torcula, as well as the vasculature immediately distal to the torcula, was markedly ectatic and distended by blood. A large, complex, dural-based vascular web of irregular blood vessels from 3 mm to 3 cm in diameter was in the midline of the posterior cranial fossa between the torcula and the foramen magnum (Images 6 and 7). The lumina of these dilated vessels were filled with clotted blood and embolization material (Image 8).

Image 6.

Posterior fossa dural venous vasculature, in situ, showing a complex vascular web of irregular blood vessels between the torcula and the foramen magnum.

Image 7.

Posterior fossa dural venous vasculature, with the dura removed from the skull.

Image 8.

Cross sections of the posterior fossa vascular web, showing vessels of varying sizes and shapes, containing blood clot and jet-black embolization material.

The brain was markedly soft and edematous, most pronounced on the left side. The unci were notched bilaterally and the cerebellar tonsils were herniated, but without parenchymal softening, hemorrhage, or necrosis. Intraparenchymal hematomas were in the parasagittal right anterior frontal lobe, right cingulate gyrus, and the left occipital pole. The subcortical white matter was variably liquefied with central cavitation in the posterior third of the left cerebral hemisphere.

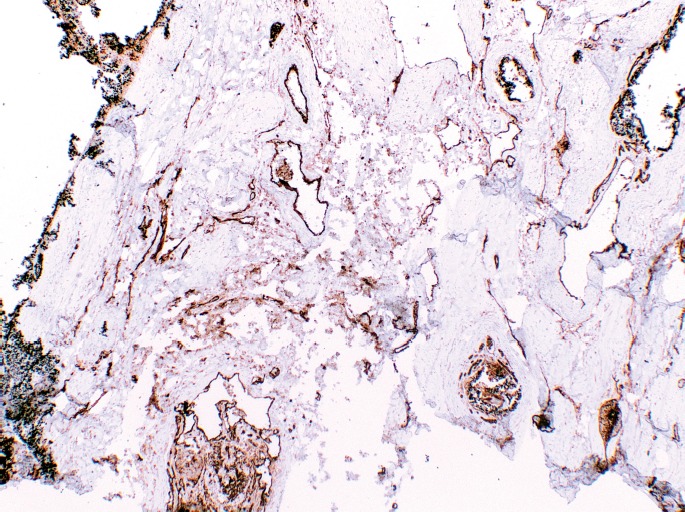

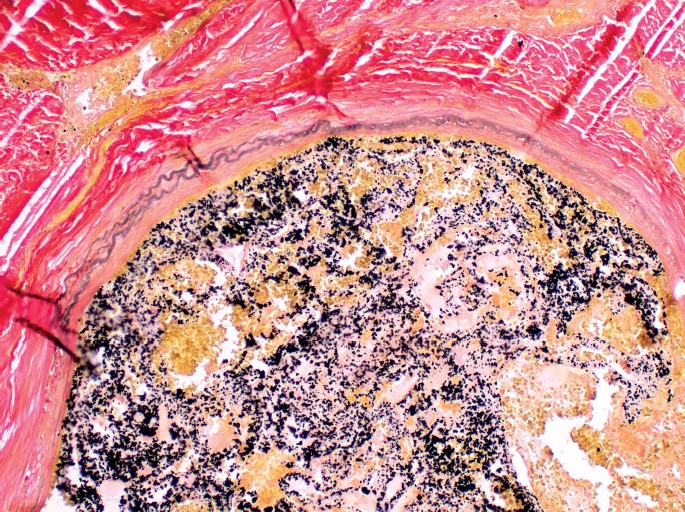

Microscopic evaluation of the abnormal dural vasculature demonstrated a collection of blood vessels of varying sizes, shapes, and configurations (Image 9). The blood vessel collection was composed of veins, arteries, and arterialized veins. Old lamellated thrombi admixed with embolization material were in many of the vessels. CD31 highlighted the endothelial cells of the blood vessels (Image 10). Immunostaining for smooth muscle actin highlighted highlighted the smooth muscle of the arteries and arterialized veins (Image 11). Elastin staining highlighted the internal and external elastic laminae of some of the vessels. Some vessels also had duplication of the internal elastic lamina (Image 12).

Image 9.

Collection of blood vessels of varying sizes, shapes, and configurations, consisting of arteries, veins, and arterialized veins. The lumens contain jet-black embolization material (H&E, x40).

Image 10.

CD31 immunostain highlighting endothelial cells and outlining the complex vascular channels (x40).

Image 11.

Smooth muscle actin immunostain highlighting the smooth muscle in the walls of the arterialized veins (SMA, x100).

Image 12.

Elastin stain showing a thin vessel wall and duplication of the elastic layer, characteristic of arteriovenous malformations (x400).

Discussion

Intracranial dural arteriovenous fistulas can be defined as abnormal communications between meningeal veins, cortical veins, or dural venous sinuses with the dural arterial vasculature (1). Although DAVFs are commonly considered to be rare, they account for approximately 10-15% of all intracranial vascular malformations (2, 3). Fundamentally, DAVFs differ from pial or parenchymal vascular malformations in two ways: 1) they are supplied by dural arteries and 2) they do not have a parenchymal focus (2). Most DAVFs involve the transverse, sigmoid, or cavernous sinuses (3).

Most DAVFs are idiopathic, but a portion will have been associated with prior head trauma, thrombosis of a dural venous sinus, or remote craniotomy (4–7). Venous hypertension and ear infections have also been associated with formation of DAVFs (3).

Patients with DAVFs most commonly present in the fifth and sixth decades of life. Their symptoms vary depending on where the malformation is located, and its corresponding venous drainage (8, 9). The range of symptoms exists across a spectrum from asymptomatic to cognitive impairment, extremis from intracranial hemorrhage, and sudden death (3, 10).

Two classification schemes have been used to stratify DAVFs, the Borden classification system and the Cognard classification system. According to Borden, there are three types of DAVF (in each case, the arterial supply originates from the meningeal arteries) (11):

Type I: Drain into either the dural venous sinuses or the meningeal veins.

Type II: Drain into the dural sinuses or meningeal veins, and also have retrograde draining into subarachnoid veins.

Type III: Drain into the subarachnoid veins and do not have dural venous sinus or meningeal venous drainage.

All three types are further subcategorized into two types by the degree of complexity of the shunt:

Subtype a: Simple fistula with single direct connection between the artery and the draining vein/sinus.

Subtype b: Complex fistula with numerous connections.

According to the Cognard classification system (12), DAVFs are categorized based on the direction of sinus drainage, whether or not cortical venous drainage is involved, and the morphology of the venous outflow tract. Five major DAVF types are recognized in the Cognard system:

Type I: Drain into a dural sinus, have anterograde flow, and lack cortical venous drainage.

Type IIa: Drain into a dural sinus, have retrograde flow, and lack cortical venous drainage.

Type IIb: Drain into a dural sinus, have anterograde flow, and have cortical venous drainage.

Type IIa+b: Drain into a dural sinus, have retrograde flow, and have cortical venous drainage.

Types III, IV, and V: Do not drain into a dural sinus, have varying venous outflow architecture, and have cortical venous drainage.

Conclusion

Although DAVFs are uncommon, and complete classification of the malformations requires angiography, forensic pathologists need to be aware that DAVFs can be the cause of nontraumatic bleeds in cases with subdural hemorrhage, intracerebral hemorrhage, or both. This case is a reminder of the necessity to thoroughly examine the dura during the course of each forensic autopsy, and to remember that some subdural hemorrhages are nontraumatic in origin. That said, upon recognition of a DAVF, forensic pathologists should carefully review the decedent's history for remote blunt head trauma that may have been the underlying cause of this abnormality.

Footnotes

ETHICAL APPROVAL

As per Journal Policies, ethical approval was not required for this manuscript

STATEMENT OF HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

This article does not contain any studies conducted with animals or on living human subjects

STATEMENT OF INFORMED CONSENT

No identifiable personal data were presented in this manuscsript

DISCLOSURES & DECLARATION OF CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors, reviewers, editors, and publication staff do not report any relevant conflicts of interest

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE The authors have indicated that they do not have financial relationships to disclose that are relevant to this manuscript

References

- 1).Gandhi D., Chen J., Pearl M. et al. Intracranial dural arteriovenous fistulas: classification, imaging findings, and treatment. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2012. Jun; 33(6): 1007–13. PMID: 22241393. 10.3174/ajnr.A2798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2).Kwon B.J., Han M.H., Kang H.S., Chang K.H. MR imaging findings of intracranial dural arteriovenous fistulas: relations with venous drainage patterns. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2005. Nov-Dec; 26(10): 2500–7. PMID: 16286391. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3).Gomez J., Amin A.G., Gregg L., Gailloud P. Classification schemes of cranial dural arteriovenous fistulas. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2012. Jan; 23(1): 55–62. PMID: 22107858. 10.1016/j.nec.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4).Chung S.J., Kim J.S., Kim J.C. et al. Intracranial dural arteriovenous fistulas: analysis of 60 patients. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2002; 13(2): 79–88. PMID: 11867880. 10.1159/000047755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5).Nabors M.W., Azzam C.J., Albanna F.J. et al. Delayed postoperative dural arteriovenous malformations. Report of two cases. J Neurosurg. 1987. May; 66(5): 768–72. PMID: 3572502. 10.3171/jns.1987.66.5.0768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6).Awad I.A., Little J.R., Akarawi W.P., Ahl J. Intracranial dural arteriovenous malformations: factors predisposing to an aggressive neurological course. J Neurosurg. 1990. Jun; 72(6): 839–50. PMID: 2140125. 10.3171/jns.1990.72.6.0839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7).Izumi T., Miyachi S., Hattori K. et al. Thrombophilic abnormalities among patients with cranial dural arteriovenous fistulas. Neurosurgery. 2007. Aug; 61(2): 262–8; discussion 268-9. PMID: 17762738. 10.1227/01.NEU.0000255529.46092.7C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8).Hurst R.W., Bagley L.J., Galetta S. et al. Dementia resulting from dural arteriovenous fistulas: the pathologic findings of venous hypertensive encephalopathy. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1998. Aug; 19(7): 1267–73. PMID: 9726465. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9).Obrador S., Soto M., Silvela J. Clinical syndromes of arteriovenous malformations of the transverse-sigmoid sinus. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1975. May; 38(5): 436–51. PMID: 1097602. PMCID: PMC491995. 10.1136/jnnp.38.5.436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10).Kominato Y., Matsui K., Hata Y. et al. Acute subdural hematoma due to arteriovenous malformation primarily in dura mater: a case report. Leg Med (Tokyo). 2004. Oct; 6(4): 256–60. PMID: 15363452. 10.1016/j.legalmed.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11).Borden J.A., Wu J.K., Shucart W.A. A proposed classification for spinal and cranial dural arteriovenous fistulous malformations and implications for treatment. J Neurosurg. 1995. Feb; 82(2): 166–79. PMID: 7815143. 10.3171/jns.1995.82.2.0166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12).Cognard C., Gobin Y.P., Pierot L. et al. Cerebral dural arteriovenous f istulas: clinical and angiographic correlation with a revised classification of venous drainage. Radiology. 1995. Mar; 194(3): 671–80. PMID: 7862961. 10.1148/radiology.194.3.7862961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]